- 1School of Economics and Business Administration, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China

- 2Business School, Southwest University of Political Science and Law, Chongqing, China

The government of China has launched an environmental campaign called “Ecological Civilization Construction” and successively set up demonstration zones for ecological civilization construction in some regions since 2012. This paper studies how demonstration zones influence technology investment of local enterprises. In order to eliminate potential endogeneity issues and differences in time trends of technology investment in regions and industries outside of policy impacts, so as to accurately identify policy effects of demonstration zones, we adopted the difference-in-difference (DID) and difference-in-difference-in-difference (DDD) model. The results are as follows: first, after the policy, firms in the demonstration zones make more investment in technology, and the necessary condition for this effect is that the firms are in a state of growth. Second, the level of regional economic development has a positive moderating effect on the main results by influencing the impact of policies on local government incentives. Third, the intensity of environmental regulation expressed by air pollution index has a positive moderating effect on the main results. Fourth, firms with strong social responsibility will not be affected by such administrative pressure. Fifth, whether firms with strong financing constraints can increase technology investment depends on government subsidies.

Introduction

As China’s economy transitions from “high-speed growth” to “high-quality growth”, the importance of ecological civilization is becoming more and more prominent and has become a key guarantee for China’s sustainable and healthy economic development. The development of the last decade has shown that China’s ecological environment has improved considerably, so what impact has the implementation of the ecological civilization had on micro enterprises and how has it contributed to achieving a higher quality of China’s economic development?

In this regard, the existing literature is mostly based on (Porter and Linde, 1995) hypothesis, and studies have almost exclusively been conducted from the perspective of environmental regulation and technological innovation or productivity. However, there are serious endogeneity problems with environmental regulation variables, such as the composite index of pollutant treatment rates, that are commonly used in the literature. Regions with better technological innovation or higher productivity may also have higher pollutant treatment rates, and few studies have provided detailed theoretical and institutional analysis of the economic consequences of ecological civilization construction. Even fewer studies have provided empirical evidence of the impact of ecological civilization building at the micro-firm level. We find that the construction of an ecological civilization directly increased the marginal impact of environmental performance in the being promoted by of local officials, and indirectly increased the importance of environmental performance as measured by public satisfaction. Formally, local governments driven to meet environmental performance goals face incentives to increase the intensity of regional environmental regulations to improve the level of regional ecological civilization construction and weaken targets for short-term economic performance, inducing polluting firms to increase their technological investments. Informally, these local governments also face incentives to strengthen the publicity and education regarding ecological civilization construction in an effort to cultivate the public’s environmental awareness and promote polluting firms’ technological investment (Pargal and Wheeler, 1996).

In view of this, firstly, this paper clarifies, through theoretical and institutional analysis, how the construction of ecological civilization changes the incentives of local governments and how it affects the technological investments of polluting firms. Secondly, using the establishment of two batches of early demonstration zones for ecological civilization construction in 2014 and 2015, an exogenous event for firms, and a double difference model is constructed to overcome the endogeneity problem and to analyse the impact of ecological civilization construction on technology investment of heavily polluting listed A-share companies in China. Finally, the moderating role of government subsidies, the heterogeneity of the regional economic development level dimension, and the heterogeneity of the corporate social responsibility dimension are examined.

Based on the above research, the main conclusions of this paper are as follows: 1) the construction of ecological civilization promotes technological investment by heavily polluting enterprises with better business conditions; 2) while implementing stricter environmental regulations, the granting of government subsidies can effectively alleviate the financing constraints faced by polluting enterprises in technological investment; 3) the construction of ecological civilization is more effective in the eastern regions with higher levels of economic development; 4) the construction of ecological civilization has a greater impact on polluting enterprises that fulfil fewer social responsibilities.

The contributions of this paper include: 1) providing a feasible analytical perspective for the study of the economic consequences of ecological civilization construction as an incentive for officials to be promoted; 2) providing direct empirical evidence that ecological civilization construction can promote technological investment in micro-polluting firms; 3) helping to evaluate the effects and limitations of ecological civilization construction and providing a reference for the Chinese government to promote institutional reform and enhance economic development; 4) providing empirical evidence for the weak Porter hypothesis at the micro-firm level.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Part II reviews the relevant existing literature; Part III gives institutional background and formally presents our hypothesis; Part IV presents the model; and discusses the data; Part V reviews the empirical results; Part VI briefly discusses avenues for further research; and Part VII concludes.

Literature review

The principal argument of this paper is that the construction of an ecological civilization in China changes the incentives of local governments, increasing the importance of environmental performance, and inducing local governments to strengthen environmental regulations. This in turn forces force polluters to invest in technology to reduce their levels of pollution. We now review the literature in three areas: officials’ incentives, environmental regulation and technology investment, and government subsidies and technology investment.

Officials’ incentives

Local government officials are vital to economic development, so it is crucial to devise a range of management controls to select them and to achieve incentive compatibility between officials and economic performance. For developing countries, “getting the incentives right” is a necessary to promote economic growth (Gerald, 2002). The traditional fiscal decentralization theory suggests that the transfer of fiscal revenue and expenditure power from a central government to local governments can promote inter-regional competition (Qian and Roland, 1998), but in the case of China, the theory of “fiscal federalism with Chinese characteristics” proposed by Qian and Weingast (1997) suggests that China’s fiscal institutional arrangement is de facto federalism, which gives local governments strong fiscal incentives(Jin et al., 2005). In contrast, the “promotion tournament” theory proposed by Zhou (2007) argues that in the context of China’s high political centralization, career promotion incentives are more important for government officials, and fiscal decentralization is only a necessary condition for career promotion incentives to work. Li and Zhou, 2005 also point out that China’s administrative governance model is a self-governing model in which economic performance is the most important measure of success. Yang and Zheng, (2013) clarified the confusion between promotion scale tournaments and promotion tournaments, pointing out that the former competition focuses on comparison with the mean value of economic performance, while the latter focuses on the ranking of economic performance. Their empirical results support another so-called promotion qualification tournament hypothesis that states that officials with a certain standard of economic performance ranking are more likely to be promoted. Going further, Luo et al. (2015) argued that promotion incentives based on economic performance are beneficial to both regime legitimacy government, and regime authority, and their empirical results suggest that economic performance is indeed positively related to the probability of promotion in Chinese local governments.

Under the “promotion tournament” theory, GDP growth rate is the most common indicator to measure economic performance. Although it has effectively promoted economic growth, it has also caused a lot of problems, such as overcapacity, resource shortage, environmental degradation, insufficient innovation and low quality of economic growth (Tang and Liu, 2012; Zhang and Song, 2021). With the slowdown of macroeconomic growth, the negative impact of the aforementioned “GDP-only growth theory” has become more and more prominent, and achieving high-quality economic development has become the focus of the government’s economic construction work nowadays, while at the same time, the construction of ecological civilization, as an inherent requirement of high-quality economic development, has received more and more attention from the Party Central Committee. Li et al. (2018) argues that breaking down the economic performance perspective and increasing the weight of political indicators such as the environment and people’s livelihoods can help reduce local productivity losses. Liu and Zhao, (2018) and Zhang et al. (2018) argue that after the transformation of the performance appraisal system, reasonable performance appraisal indicators can be set to enable environmental governance and economic growth to develop in a benign and sustainable manner. In short, this apparent shift in environmental performance appraisal is helping China to achieve the goal task of sustainable ecological and environmental protection while developing the economy.

The existing literature has given a full interpretation of the economic performance incentives of local governments in China, but there is still a lack of attention to the environmental performance incentives, especially the ecological civilization construction incentives proposed by the Chinese central government in recent years. Considering the international community’s increasing attention to climate change (Jia et al., 2022) and the important impact of ecological environment on efficiency (Su et al., 2021), it is very important to study this issue.

Environmental regulation and technology investment

Neoclassical economic theory suggests that environmental regulation, which diverts resources controlled by firms from productive uses to pollution control uses (Gray, 1987), only imposes additional costs on firms and reduces their productive business inputs. According to this theory, environmental regulation reduces the resources freely available to firms and discourages their technological investment (Conrad and Wastl, 1995; Gray and Shadbegian, 2003). Several economists, represented by Porter in particular, have questioned this and have argued that the previous analysis (from a static perspective) is inappropriate. These economists thus analyzed the impact of environmental regulations on firms under a dynamic perspective and put forward the Porter hypothesis: properly designed environmental regulations can stimulate firms to innovate and thus partially or even completely offset the compliance costs of the regulations, which has come to be firm called the innovation compensation effect of environmental regulation (Porter and Linde, 1995).

The Porter hypothesis is supported by a large number of studies. First, in terms of different types of environmental regulation: Wang and Xu (2015) subdivide environmental regulation into three types: environmental administrative control, environmental pollution regulation and environmental economic regulation, and the empirical results show that all three regulatory instruments can decouple the haze by influencing firms’ technology investment preferences. Second, in terms of the breakdown of Porter’s hypothesis, tests of the weak Porter’s hypothesis, that environmental regulation stimulates firm innovation, have generally show that environmental regulation does stimulate firm innovation (Johnstone et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2013). For tests of the strong Porter’s hypothesis, that environmental regulation enhances firm competitiveness through the innovation compensation effect, most studies have used productivity as a proxy for competitiveness and have found that under certain conditions, environmental regulation can indeed enhance productivity (Wang and Liu, 2014; Ren et al., 2019).

Furthermore, a large number of domestic studies have shown that Porter’s hypothesis has a threshold effect on the intensity of environmental regulation (Fu and Li, 2010; Dong and Wang, 2019) and the level of regional economic development (Zhang et al., 2011). That is, the Porter effect can be realized only when the intensity of environmental regulation or the level of economic development reaches a certain level. In addition to formal environmental regulations imposed by the government, public environmental awareness, media opinion guidance, and the power of environmental organizations can also influence firms’ pollution behavior, and these factors are sometimes referred to as informal environmental regulations (Pargal and Wheeler, 1996). The results of Yuan and Xie (2014) show that both informal and formal regulations contribute to industrial restructuring. Some scholars have also studied the issue from the perspective of environmental decentralization, Wu et al. (2020a) arguing that with the further expansion of environmental decentralization, the local government’s autonomous choice of pollution control is improved. The improvement of environmental decentralization can lead to negative moderating effect of environmental regulation on green total factor energy efficiency.

In terms of research on environmental regulation and corporate technology investment, scholars argue that when companies face strict environmental regulation, whether by increasing pollution control expenditure to control pollution emissions or by improving pollution control technology to offset the increase in cost expenditure brought about by government environmental regulation, it will inevitably increase the cost and expense of companies and reduce their profitability. At this point, enterprises may close down some highly polluting production projects and allocate their capital to high-return, low-threshold, non-polluting financial-like businesses instead. Some scholars have also argued the opposite, arguing that although investment in environmental technology will increase a company’s operating costs, it will be beneficial in the long run, both for the company itself and for the ecological environment as a whole. Ren et al. (2022) believe that green investment can reduce environmental pollution by improving efficiency of energy conservation and emission reduction, expanding technological innovation capabilities and upgrading the industrial structure. Environmental regulation has effectively constrained the increase in carbon emissions in eastern and central China (Wu et al., 2020b).

Although many literatures have provided empirical evidence on environmental regulation and enterprise technology investment, there are still some shortcomings. First, regulation is highly correlated with some factors (e.g. the level of economic development) that are positively correlated with technology investment, so it is difficult to solve the endogeneity problem. Moreover, different from the previous environmental regulation, the construction of ecological civilization directly changes the incentives of local governments. There is still no empirical evidence on how such a policy that fundamentally changes the regulator’s behavior function affects technology investment.

Government subsidies and technology investment

Technology innovation usually faces financing constraints, which can be alleviated by government subsidies. The innovation of firms has two important distinguishing characteristics: having long-term effects and being fraught with uncertainty. Hence, firms often face difficulty in obtaining low-cost external financial support, so their funds mostly come from internal financing. However, internal financing is usually far inferior to external financing in terms of capital scale and is also subject to firms’ operations. When the market environment is unstable, the scale of internal financing can fluctuate greatly, causing innovation activities to stagnate due to the breakage of the capital chain (Ju et al., 2013). Additionally, innovation activities typically have high adjustment costs, and sudden interruption and re-continuation can create operating losses for firms (Hall, 2002).

Financing constraints are an important challenge for firms’ seeking to invest in technological innovation. However, government subsidies can provide net cash inflows to firms, but existing studies on using government subsidies to promote innovation have not found consistent empirical evidence that this is the case. Li et al. (2013) show that government subsidies can promote innovation investment and also stimulate firms to increase their innovation investment through bond financing. However, a study by Zhou et al. (2015) on the “new” energy industry shows that government support is hardly effective in encouraging firms to invest more in research and development (R&D) after industry expansion. Li et al. (2017) found that government innovation subsidies were positively correlated with firms’ total innovation investment but negatively correlated with the private portion of firms’ innovation investment, suggesting that government innovation subsidies actually crowd out firms’ own innovation investment.

Unlike external financing in the usual sense such as bank loans, government subsidies can come in the form of financial subsidies or tax concessions for political, economic, or social reasons in order to guide industrial development or inhibit the occurrence of certain unintended economic behaviors (Pan et al., 2009), Government subsidies do not typically have profit-making motives, and their disbursement is determined by government goals. Therefore, the influence of government subsidies on firm innovation under specific government objectives is more relevant to this paper. In the specific context of ecological civilization construction, government subsidies can work together with environmental regulations to help firms undergo technological transformation to help with energy saving and emission reduction. The results of the analysis by Acemoglu et al. (2012) showed that the combination of government environmental pollution taxes and R&D subsidy policies could promote clean innovation without sacrificing economic growth, and Su and Zhou (2019) found that government subsidies had a positive moderating effect on the “U-shaped” relationship between formal environmental regulations and firms’ innovation output.

Although existing studies have shown the complex impact of government subsidies on technology investment, it should be pointed out that government subsidies are always a resource allocated by the government. For companies, acting on the incentives of local governments can lead to more resource allocation. Therefore, it is necessary to introduce the factor of government subsidy into the analytical framework of this paper.

Institutional background and research hypothesis

Institutional background

With the development and changes of China’s political and economic systems, the incentive faced by government officials has also changed. Prior to 1978, the selection and promotion of local officials was entirely based on politics, resulting in a lack of motivation for local governments to work toward the development of their regional economies. Since the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee, the Chinese Communist Party shifted its focus from class struggle to economic construction, after which regional economic development, especially the performance of GDP growth, became an important basis for the promotion of local officials (Li and Zhou, 2005). In addition, the fiscal lump-sum system of the 1980s and the tax sharing reform in the 1990s both gave local governments a considerable degree of economic autonomy by giving them the ability to influence local GDP growth rates. Coupled with a high degree of political centralization, the promotion of officials is usually determined by superiors, and a top-down promotion tournament model with economic performance as the main assessment indicator has gradually developed in China. An obvious drawback of this model is that “economic performance” indicators such as GDP growth rate become the main goal of local governments, while noneconomic performance indicators such as environmental quality become seriously neglected.

In recent years, with the slowdown of China’s economic growth, a series of environmental problems such as resource shortages and environmental degradation have become more and more prominent, and questions about “simply judging heroes by GDP growth rate” have been raised. In this context, the flaws of the above-mentioned traditional promotion tournament model have been dramatically magnified, especially the environmental problems caused by irrational government-led investments. For this reason, environmental quality has been incorporated into the assessment system of Chinese officials in some form, and in 2007, the “Eleventh Five-Year Plan for National Environmental Protection” stated that local governments should be responsible for the environmental quality of their administrative areas and implement their environmental responsibilities and established an environmental protection target responsibility system to strengthen evaluation and assessment. In 2010, the Ministry of Organization issued the “Comprehensive Assessment and Evaluation Measures for Local Party and Government Leadership Teams and Leading Cadres (for Trial Implementation)", which stipulated that “energy conservation, emission reduction and environmental protection” would be included as assessment contents for the CCP’s leadership team. As chairman Xi Jinping said, “no longer can we simply judge the hero by the growth rate of GDP."

In order to tackle the issues of resources and the environment, accelerate the construction of a resource-saving and environment-friendly society, and continuously improve the level of ecological civilization, the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Land and Resources, the Ministry of Water Resources, the Ministry of Agriculture, the State Forestry Administration, and other six departments formulated and released the “National Ecological Civilization Advance Demonstration Zone Construction Program (Trial)" on 2 December 2013, which planned to set up a number of ecological civilization demonstration zones throughout the country to carry out pilot work for ecological civilization construction. The Program not only puts forward the objectives and tasks directly linked to the construction of an ecological civilization but also requires the demonstration zones to implement institutional mechanisms and establish ecological culture systems.

Some innovative institutional mechanisms include: significantly increasing the weight of the indicators that reflect the construction of an ecological civilization in the comprehensive evaluation system of regional economic and social development, establishing an accountability system for the construction of an ecological civilization and a lifelong accountability system for leading cadres, taking the lead in exploring the preparation of natural resources assets and liability statements, and integrating the leading cadres’ natural resources assets and resources and environment into the discharge audit., Goals related to the establishment of an ecological culture system include: cultivating the concept of an ecological civilization as engendering mainstream social values, strengthening ecological civilization publicity and education, and advocating “green” lifestyles and consumption patterns. Two batches of demonstration zones were approved to be established in October 2014 and December 2015.

Research hypothesis

From the above we can see that the establishment of the demonstration zones not only gives local governments a set of clear goals but also, makes corresponding adjustments to official’s incentives. First, it directly adds the weight of environmental performance to the general performance appraisal system of officials (for example, requirements related to innovative institutional mechanisms). Second, the policies are closely followed by the official Chinese state media, in order to strengthen the publicity and education of ecological civilization construction. Higher public attention related to the construction of an ecological civilization may increase the marginal benefit of the government’s environmental protection work in terms of public satisfaction and thus indirectly increase the importance of environmental performance. Finally, as an element of officials’ incentives, environmental performance is different from traditional economic factors as an indicator of officials’ performance Local governments may be willing to improve their environmental performance even though it may be at the expense of GDP growth in the short run.

Firms are the largest emitters of pollution in China (Fan and Zhang 2018), but firms often lack incentives to control pollution. Thus, in order to achieve better environmental performance, local governments have an incentive to adopt stricter environmental regulations that to internalize the externality costs of pollution to the emitting firms. In China, although environmental laws and standards are set by state authorities, local governments can still influence the intensity of environmental regulations by enacting local laws and regulations, and normative documents on environmental protection. However, even without this regulatory system, local governments can still change the intensity of environmental regulations by changing the intensity of enforcement. In fact, a large number of studies based on regional panel data have been predicated on the fact that environmental regulation varies in regional and temporal dimensions. In addition to direct formal environmental regulation, local governments can also try to influence public opinion, environmental organizations, and other social forces to form informal environmental regulations on polluting firms through publicity and education (Pargal and Wheeler, 1996).

Following the results of existing research on environmental regulation, we now argue that the above-mentioned effects of ecological civilization construction on polluting firms can promote technological investment actually. To begin, stronger environmental regulation means higher pollution costs, and technological investment in energy conservation and emission reduction can bring higher marginal returns. Next, typical environmental regulation is born in local governments, and its intensity may fluctuate with these governments’ willingness to regulate, but ecological civilization construction goals are set by the central government and monitored by the relevant central departments, which are relatively more exogenous to local governments and are more stable making technology investment by local firms less uncertain. In addition, most existing research shows that both formal and informal environmental regulations can promote corporate technology investment. Finally, technology investment is conducive to pollution control, energy conservation and emission reduction, production efficiency improvement, and industrial upgrades. As mentioned above, according to the theory of legitimacy, polluting firms are motivated to make more technology investments to maintain their “legitimacy".

Though the above argument may apply to all firms in China, there are differences in its applicability to firms with different operating conditions. Compared to firms with good operating conditions, firms with poor operating conditions may be less likely to be influenced by the construction of an ecological civilization to invest in technology. Firms with poor operating conditions may face lower future demand, which means fewer current investment opportunities and less need for technology investment aimed at pollution prevention. However, the strategic management theory holds that the key to technological innovation of firms lies in access sufficient financial resources. Firms with poor operating conditions usually have unstable operating cash flows, poor internal financing capabilities, and high external financing costs. As a result, their ability to make innovative technological investments is low. In addition, local governments and the public (who are aware of the above) tend to place lower environmental requirements on these types of firms with poor operating conditions, and consequently impose fewer environmental regulations on them.

Based on the above we propose the following research hypothesis.

Hypothesis: The establishment of demonstration zones promotes technological investment in polluting firms with better operating conditions.

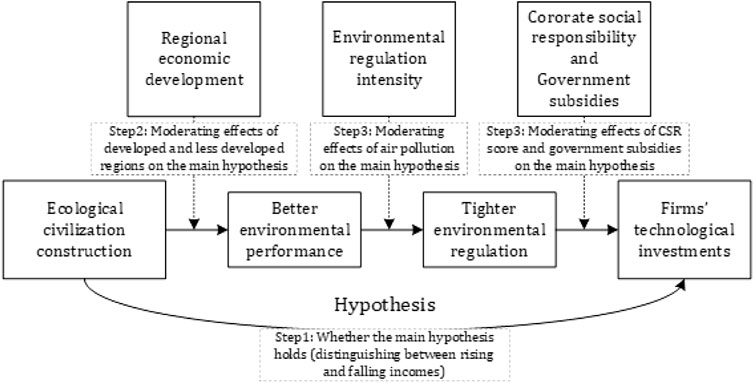

Figure 1 shows the logical framework and the steps of empirical analysis:

Obviously, the main hypothesis is represented by the solid arrows in the figure. The figure also shows the action path of the hypothesis: first, ecological civilization construction enhances local governments’ demand for environmental performance; second, local governments adopt stricter environmental regulations; and finally, enterprises increase technological investment as a response. In addition, the figure shows several variables that will have an important impact on the hypothesis, which will be discussed further later: first, the level of regional economic development will affect the impact of ecological civilization construction on the environmental performance demand of local governments; second, the intensity of environmental regulation corresponds to the stricter environmental regulation adopted by local governments; third, firm characteristics, including corporate social responsibility and government subsidies, affect the degree to which companies respond to environmental regulations.

Model design and sample selection

Model design

Empirical research on environmental regulation’s impact to corporate behavior usually have endogenous problems: there may be invisible factors, at the same time affect the intensity of environmental regulation and the enterprise behavior, for example, the public environmental awareness could encourage local enterprises increase environmental investment, prompted the local government to strengthen environmental regulation at the same time, it's hard to say the observed behavior is caused by environmental regulation. The construction of ecological civilization provides a good exogenous impact: first, the establishment of ecological civilization demonstration zone is the decision of the central government, which is unlikely to be anticipated by local governments and enterprises; second, the distribution of demonstration areas in the east, middle and west is relatively uniform, which indicates that the selection of demonstration areas is random to a certain extent. DID is a conventional model that uses exogenous shocks for empirical testing. On the one hand, the average effect of policies can be obtained through the difference between before and after the time point. On the other hand, through the difference between the experimental group and the control group, the time trend outside the policy can be eliminated and the net effect of the policy can be obtained. Therefore, this paper constructs the DID model for empirical test, as follows:

Anderson et al. (2003) constructed a cost stickiness model based on the positive relationship between cost and business volume, and Liu and Zhang (2018) constructed a regression model of fixed asset investment and business volume based on Anderson et al. to observe the behavior of firm to reduce capacity. Drawing on these existing models, we construct a regression model of technology investment and business volume to measure the intensity of firms’ technology investment.

Here, IA denotes the original value of intangible assets excluding land use rights as a proxy variable for technology investment (Hao et al., 2014); Sale denotes main business income as a proxy variable for business volume; and the coefficient a1 reflects the intensity of technology investment. We note that a1 has different meanings when business volume rises and falls, respectively. When business volume rises, the larger a1 is, the greater the technical investment intensity (the greater the investment rises with the business volume), and when business volume falls, the larger a1 is, the smaller the technical investment intensity. In order to distinguish between these two meanings and to test Hypothesis, we divide the total sample into a poor business group and a good business group according to whether business volume declines or not in our later empirical analysis.

As mentioned earlier, the focus of this paper is on how the establishment of demonstration zones affects the technological investment intensity of polluting firms; we are thus interested in the change in the magnitude of a1 in model (1). Since it is impractical to measure the value of a1 for each “firm-year”, we propose the following model for factors that influence technology investment intensity, drawing on Banker et al.'s (2013) approach.

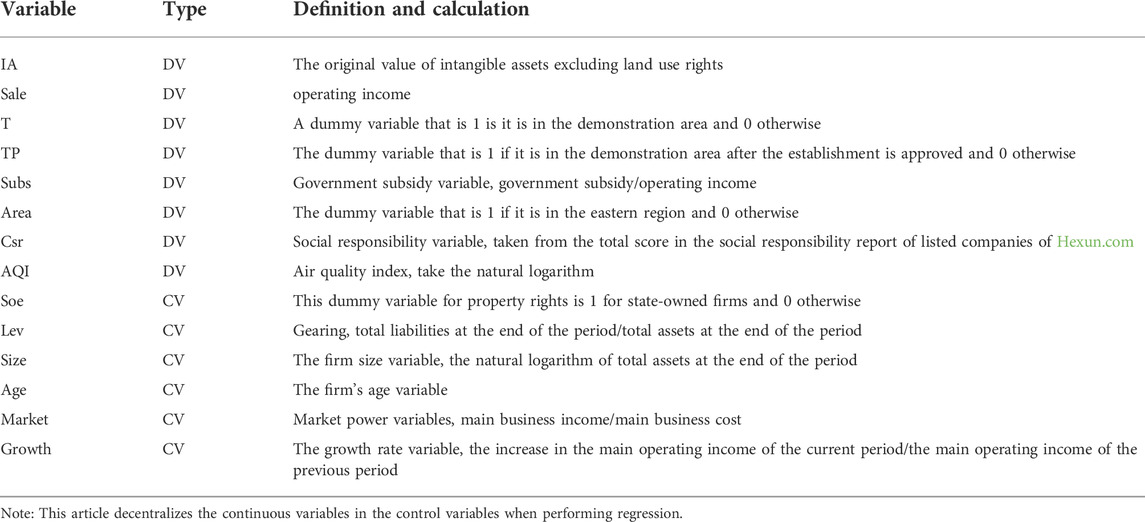

Here, T is a dummy variable for whether the firm is in the demonstration area; TP is the interaction term of DID; and X is control variables. Referring to the existing research on environmental regulation and enterprise innovation (Su and Zhou, 2019), control variables include: the nature of property rights, return on total assets, gearing, firm size, firm age, market power, and operating income growth rate as defined fully in Table 1. Substituting model 2) into model 1) yields our baseline regression model.

In model (3), in the rising business volume group, if ß2 is significantly positive, then this indicates that the establishment of the demonstration zone promotes technological investment in polluting firms, and the coefficients of the falling business volume group are interpreted in the opposite way.

Sample selection

The demonstration zones were established in two batches, October 2014 and December 2015, so we take the end of 2014 as the time point for the establishment of the first batch of demonstration zones and the end of 2015 in the same way, and take A-share listed companies, belonging to the heavily polluting industry, registered in the demonstration zones as the experimental group and A-share heavily polluting listed companies registered not in the demonstration zones as the control group, then construct a DID model. Our definition of a heavy pollution industry is taken from the study of Pan et al. (2019). Industry information and property rights data are from the RESSET database, air quality index data is from CNRDS database, and registered address, company age information, and other financial data are from the CSMAR database. After excluding samples with missing data, we obtained 474 A-share listed companies in the heavy pollution industry with 2,370 observations over 5 years were. To eliminate the effects of extreme values, we winsorize all continuous variables by 1% at both ends of the distribution.

Empirical results and analysis

Descriptive statistics

Establishment of demonstration zones

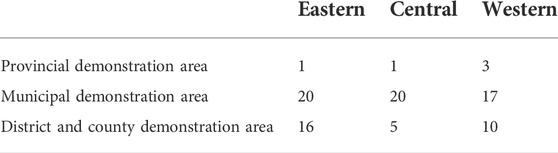

Table 2 shows the distribution of the early demonstration zones for China’s ecological civilization construction. The demonstration zones in the three major regions of east, central, and west China are more evenly distributed, with relatively more demonstration zones at the provincial level in the west and relatively more demonstration zones at the county level in the east. There are also more demonstration zones at the municipal level in general.

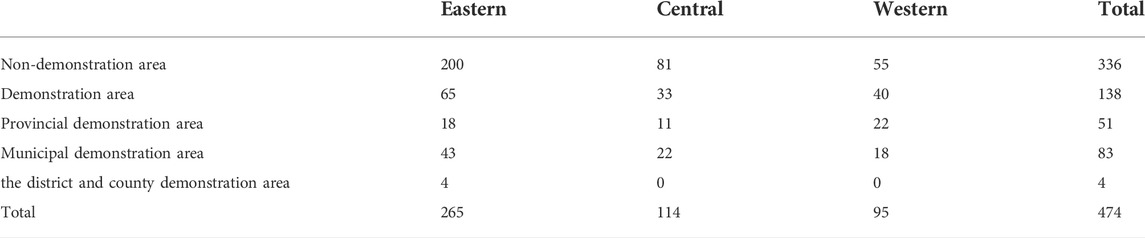

Table 3 shows the regional distribution of A-share listed companies in heavy pollution industries. Heavy pollution listed companies in nondemonstration areas number about twice as many as those in demonstration areas. The heavy pollution listed companies in the eastern region are roughly as numerous as those in the central and western regions combined, and the treatment group belonging to municipal demonstration areas has the largest sample, followed by provincial demonstration areas, and district and county demonstration areas, in that order.

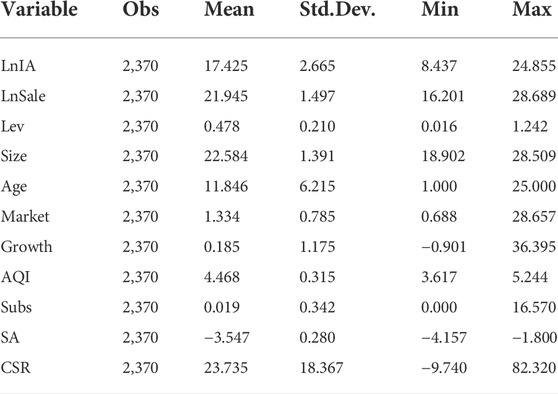

Descriptive statistics of the variables

Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics of the main variables. The mean value of technical assets is 17.425, and the mean value of operating income is 21.945, indicating that the scale of technical assets of our sample companies, namely listed companies in China’s heavy pollution industry has been considerable. The maximum value of technical assets is 24.855, and the minimum value is 8.437, indicating that the sample companies have great differences in technology investment. In addition, the mean value of asset-liability ratio is about 50%, and the mean value of listed years is about 12%, which is similar to the general situation of Chinese listed companies, indicating that our sample is representative to some extent.

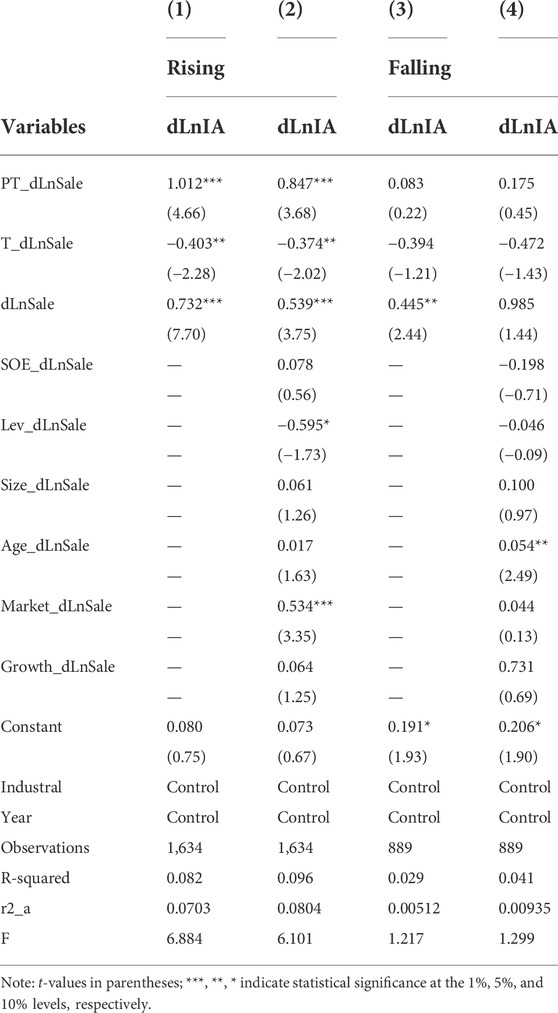

Test of hypothesis

Table 5 presents the results of our test of Hypothesis. The coefficient of the interaction term for the group with rising business volume was 1.012, and was statistically significant at the 1% significance level. After adding the control variables, this coefficient was 0.847 and was still significant at the 1% level. This result means that after the establishment of the demonstration zone, compared with the enterprises in the non-demonstration zone, the enterprises in the demonstration zone will increase their technology investments by 84.7% for the growth of each unit of operating revenue. The coefficient for the group with falling business volume was not statistically different from zero. This indicates that the approval of the demonstration zone promotes technological investment in local polluting firms with better business conditions, so we fail to reject Hypothesis.

Robustness tests

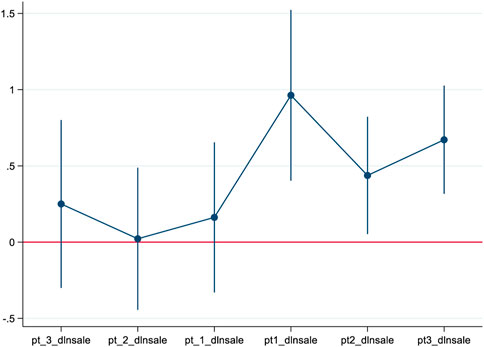

Parallel trend test

Parallel trend is a prerequisite for applying the DiD model. To this end, we built the following model based on model 3) to test whether our main model conforms to the parallel trend:

Here, TP_1/2/3 denote the TP in the 1–3 years before the policy, TP1/2/3 denote the TP in the 1–3 years after the policy. The coefficients ß2b1, ß2b2, and ß2b3 need to be insignificant.

The regression results are shown in Figure 2. Obviously, there is no significant difference between the experimental group and the control group in the 1–3 years before the policy, which conforms to parallel trend.

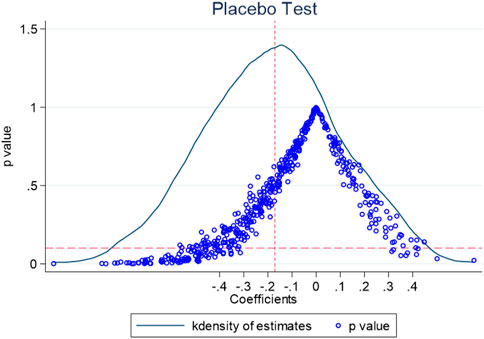

Placebo test

To avoid the possibility that our results were due to chance, that is, the randomly assigned experimental and control groups produced the existing regression results, we also performed a placebo test. Specifically, we randomly divided the sample into a virtual experimental group and a virtual control group according to the actual proportion, and then repeated the test 500 times. The results are shown in Figure 3. The results are shown in Figure 3. On average, the absolute value of the coefficient (<0.2) is much smaller than the main test (0.847) and close to 0, and most p values are much larger than 10%. These results indicate that the placebo test cannot obtain the previous results, which supports its robustness.

The DDD model

One problem with our DID model is that there may be other factors that have inconsistent effects on the technological investment intensity of firms in demonstration and nondemonstration zones. For example, the government support for technological upgrading of firms may differ from place to place, thus biasing the estimation results. We thus introduce a DDD model to overcome this problem. We select the companies in manufacturing industries that do not belong to heavy-polluting industries as the other pair of treatment and control groups. Because the central object of the demonstration zones are listed companies in heavy-polluting industries and the impact on nonheavy-polluting listed companies is small, the difference between the treatment group and control group in heavy-polluting industries is subtracted from the difference between the treatment group and control group in nonheavy polluting industries so that other factors that have influence on both can be excluded. The specific model is as follows.

Here, Dum is a dummy variable for whether the firm belongs to a heavily polluting industry (1 if it belongs). In the rising business volume group, if the coefficient ß5 of the DDD term is significantly positive, this indicates that the treatment effect of ecological civilization construction is stronger for listed companies in heavily polluting industries.

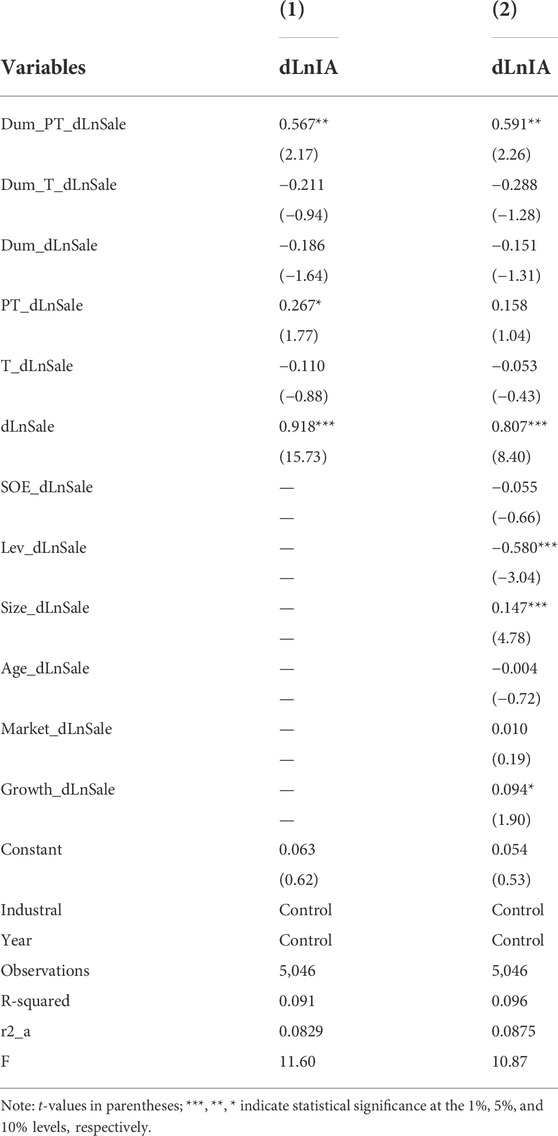

Table 6 presents the regression results for model (5). The coefficient of the DDD term is 0.567, which is statistically significant at the 5% significance level. After adding the control variables this coefficient 0.591, which is still significant at the 5% significance level. These results indicate that the main effect in heavily polluting enterprises is 59.1% greater than that of non-heavy polluting enterprises. Furthermore, this means that the results of the benchmark regression are still robust after excluding the influence of some other possible non-environmental regional factors.

Further study

Regional economic development

The level of regional economic development has a crucial influence on the baseline hypothesis of this paper. An ecological civilization in the context of modern China can only occur after a transition from a purely industrial civilization that has achieved some requisite level of development. Thus, regions with high industrialization levels are more primed to transition to the concept of an ecological civilization. The differences in the level of regional economic development in China are reflected in the polarization between the eastern regions that have a high level of industrialization and the central and western regions that have a low level of industrialization. This means that the concept of an ecological civilization lends itself more readily to the eastern regions than to the central and western regions.

From the perspective of local government incentives in these regions, it is difficult for GDP growth rate indicators to continue to “outperform” in the more developed regions. In addition, residents in economically developed regions have a higher standard of living, and the construction of an ecological civilization is more likely to stimulate the environmental protection demands of the populace, so local governments may be more motivated to work on environmental performance in order to maintain the perception of their authority and public approval. Moreover, in the context of fiscal decentralization, economically developed regions have stronger financial strength and are more capable of doing work on environmental protection. China’s central government can also selectively emphasize the environmental performance of developed regions or the economic performance of underdeveloped regions. Therefore, the impact of ecological civilization construction on local government incentives is stronger in economically developed regions.

For firms’ technology investment the more stable the macroeconomic conditions, more sound the institutions, and higher the level of human capital, the stronger the promotion effect of environmental regulation on firm technology investment. In addition, most of the existing empirical results on how environmental regulation promotes firm innovation support the threshold effect of regional economic development on environmental regulation. Based on this, we further expect the effect of ecological civilization construction to be stronger in the eastern region where the level of economic development is higher.

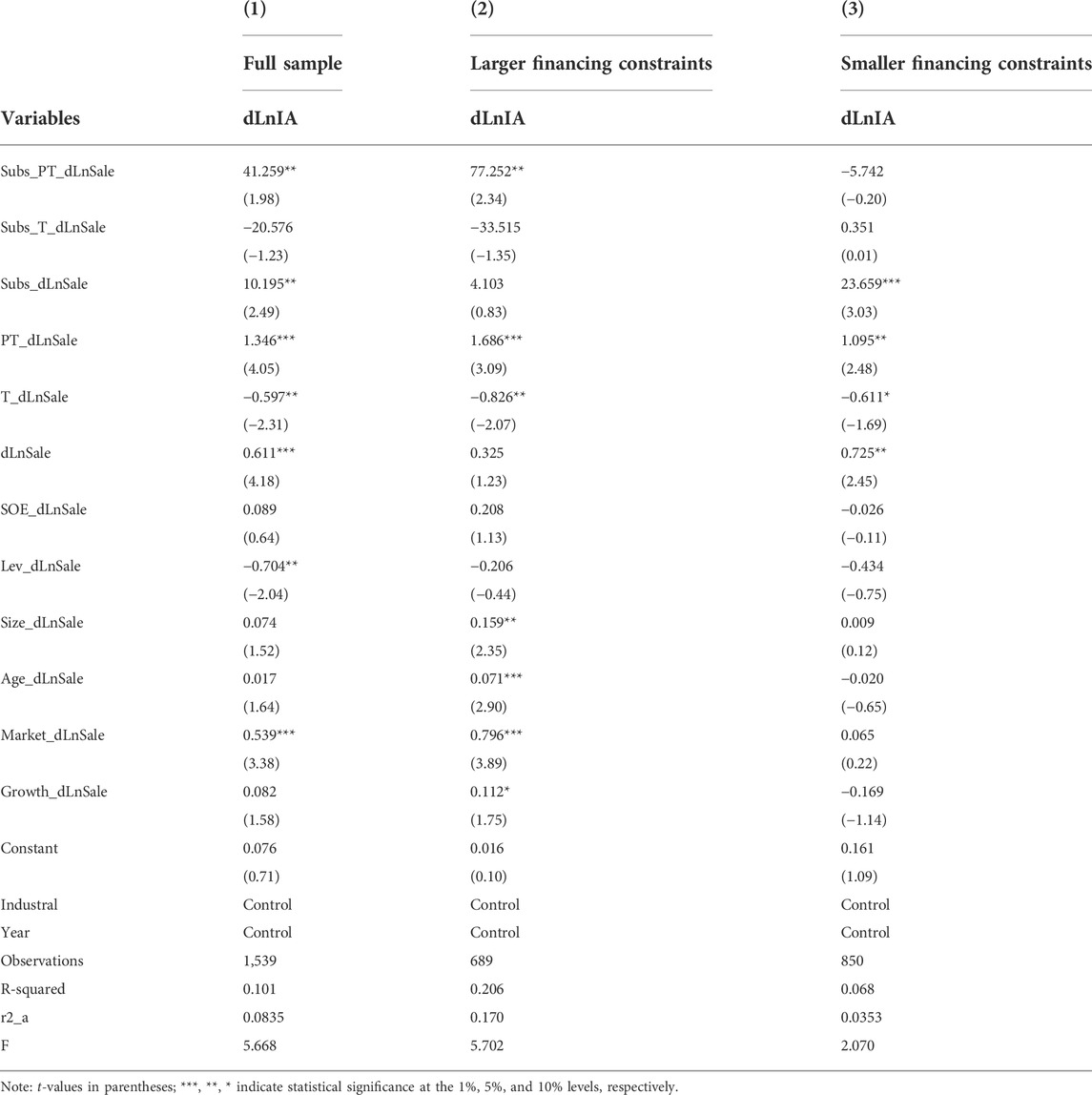

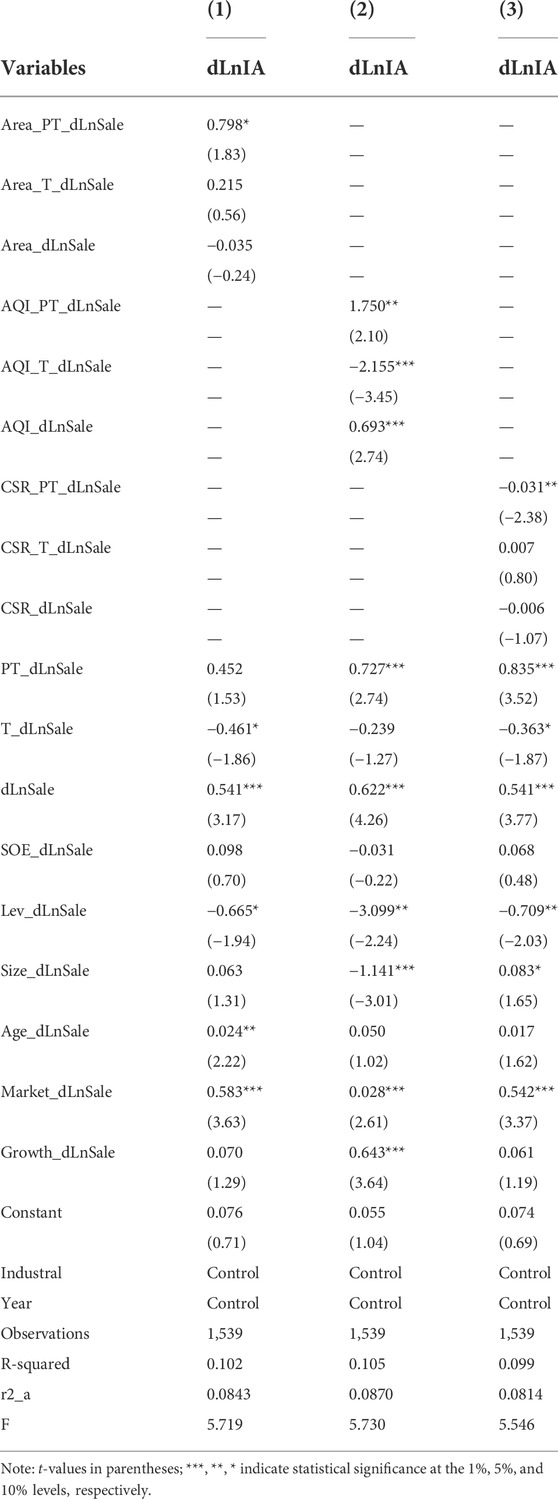

Column 1) of Table 7 shows that the coefficient of Area_pt_dLnSale is 0.798 and significant at the 10% level, indicating that the effect of ecological civilization construction in the eastern region is 79.8% stronger than that in the middle and western regions. This means that the level of regional economic development has a positive moderating effect on the impact of ecological civilization construction.

TABLE 7. Further analysis: regional economic development, environmental regulation intensity, and corporate social responsibility.

Environmental regulation intensity

As stated in the research hypothesis section, driven by the requirements of the central government on environmental performance, the government of the demonstration area will implement stricter environmental regulations on enterprises to improve their environmental performance. Obviously, the intensity of environmental regulation implemented by local government is an important condition for the main effect. Where strong environmental regulations are adopted, the impact of ecological civilization construction on enterprise technology investment should be stronger.

We use the direct result of environmental regulation, regional air quality index (AQI), to measure the intensity of local environmental regulation. The better the air quality, the stronger the environmental regulation. After adding the interaction term of AQI in model (3), the regression results are shown in column (2) of Table 7, the coefficient of AQI_pt_dLnSale is significantly positive at the 5% level. This means that the stronger the local environmental regulation, the stronger the impact of ecological civilization construction.

Corporate social responsibility

Although the purpose of environmental regulation is to eliminate the externalities of pollution and the transfer of pollution costs to polluting firms is reasonable in the normative sense, the technological investment made by polluting firms due to the pressure of environmental regulation shifts the original equilibrium to a certain extent and may also be a concession to the broader interests of society as a whole. On this basis, if a firm already contributes a lot to the local society, the environmental protection needs of the government and society caused by the construction of an ecological civilization may be smaller for this firm. That is, the role of ecological civilization construction in promoting technology investment will be smaller. Furthermore, it may also be that firms that contribute a lot to society are larger firms that contribute more to GDP growth and may be more socially responsible. These firms may also have higher levels of technology investment compared to other firms. Hence, the marginal effect of ecological civilization construction on this type of firm’s technology investment impact may be weaker. Based on this, we further expect the effect of ecological civilization construction to be stronger in firms with less existing social responsibility.

Column (3) of Table 7 shows that the coefficient of CSR_pt_dLnSale is −0.031 and significant at the 5% level. This indicating that corporate social responsibility has a negative moderating effect on the impact of ecological civilization construction, for 1 standard deviation increase in CSR, the main effect decreased by 4.0% (23.74*0.031/18.37).

Government subsidies

As pointed out in the previous section, although existing studies have not reached the conclusion that government subsidies have a catalytic effect on firm innovation, in the context of ecological civilization construction, the catalytic effect of government subsidies on firm technology investment comes to the fore. First, it is difficult to achieve productivity improvement and energy saving and emission reduction in the short term. Rather, it typically requires a large net investment of resources in the early stage of investment and a long-time horizon. Government subsidies can provide great to polluting firms, especially those facing strong financing constraints, and these subsidies therefore have a stronger marginal role in technology investment. Second, subsidies aimed at achieving “environmental performance” are more targeted. Government subsidies can be combined with environmental regulation assessment objectives, forming an effective post-event monitoring of the use of their use, which is conducive to solving the problem of information asymmetry between the government and firms. Finally, in the past in order to strive for economic performance, local governments usually spent huge amounts of financial resources to make or assist firms to make investments that they predicted would boost GDP growth in the short term, such as large-scale infrastructure construction, resulting in serious fiscal deficits and subsidies for firms to invest in technology. However, the construction of an ecological civilization makes economic performance relatively less important. In summary, we expect government subsidies to have a positive moderating effect on the construction of an ecological civilization and for this effect to be achieved by easing the financing constraints faced by firms.

Column 1) of Table 8 shows that the coefficient of Subs_pt_dLnSale is significantly positive at the 5% level of significance in the full sample. This indicating that government subsidies do have a positive moderating effect on the impact of ecological civilization construction, with 1 standard deviation increase in Subs enhances the main effect by 226.8% (41.259*0.0188/0.342). Column 2) and Column 3) show that the coefficient is significantly positive only in the sample with larger financing constraints, and not in the sample with smaller financing constraints. This indicates that the positive moderating effect of government subsidies primarily occurs by alleviating the financing constraints of firms.

Conclusion

This paper examined the impact of China’s ecological civilization construction on firm technology investment. We find that firms in the demonstration zones make more investment in technology after the policy, and the necessary condition for this effect is that the firms are in a state of growth. Our evidence also shows the moderating effect of the level of regional economic development, the intensity of environmental regulation, corporate social responsibility and government subsidies on the main effect, respectively supporting the part of the logical chain that ecological civilization construction affects enterprise technology investment through local government incentives and environmental regulations.

These findings have some further implications. First, the construction of ecological civilization adds a new input factor to the behavior function of local governments based on economic and environmental performance, which is helpful to improve the analysis framework of the behavior of local governments and enterprises in the new development stage of China, which attaches importance to the environment. Second, we found that the regional economic development level is an important moderating variable. This hints at the fact that China’s central government assigns different political tasks to different regions according to their level of economic development and resource endowments. Thirdly, we also reveal the key problem that needs to be solved to promote enterprise technology investment in ecological civilization construction, namely enterprise financing. The dependence of enterprises on government subsidies makes it difficult for enterprises with strong financing constraints to survive under strict environmental regulations, and some of these enterprises are important new forces in economic operation.

Inevitably, there are still some shortcomings in our article. First of all, the requirements of the Chinese central government for ecological civilization construction are constantly changing. Just like the policies and the establishment of demonstration zones that are concerned in this paper, our study only provides some preliminary empirical evidence. Secondly, the public, investors, creditors and other stakeholders of enterprises will be affected by the construction of ecological civilization. However, our research object is limited to enterprises, and the breadth of research is still insufficient. Finally, the span between the explanatory variables and the explained variables in our study is large, and the tests are general to a certain extent, which requires more detailed theoretical analysis and empirical tests.

This paper also has some implications for future research. As the policy advances and the economy changes, the impact of ecological civilization will evolve in breadth and depth. In terms of breadth, the role of eco-civilization is not limited to enterprises. Firstly, as a campaign promoted by the central government, the construction of ecological civilization firstly affects the incentive function of the local government, for example, the change from economic performance to environmental performance, which can be analyzed empirically in future studies. Secondly, the public is usually the main victim of environmental problems, so the impact of the ecological civilization on public satisfaction is also worthy of attention. Thirdly, how does the construction of an ecological civilization affect the stakeholders of a company, such as investors, banks, creditors, and specifically, how does it react in terms of the pricing of the company’s shares, the cost of financing, etc. In depth, the mechanisms of action and economic consequences of the construction of ecological civilization need to be further explored. Firstly, future research could focus on the pathways of action of government regulation affecting corporate investment. Secondly, how the construction of ecological civilization interacts with other important policies of China, such as emissions trading and environmental tax reform. Thirdly, whether the construction of ecological civilization promoting corporate technology investment actually have positive environmental consequences, such as reducing corporate carbon emissions, reducing environmental pollution and improved production efficiency.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author contributions

MC: Conceptualization, Supervision, Data Analysis, Writing—Original draft preparation. YC: Conceptualization, Writing—Editing and Writing—Reviewing. CJ: Data Collection, Data Analysis, Software, Writing—Original draft preparation. MR: Methodology, Data Curation, Visualization. All the authors read and approved the manuscript for submission.

Funding

This research was supported by The National Social Science Fund of China (19BJY038).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank AiMi Academic Services (www.aimieditor.com) for the English language editing and review services.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2022.1002506/full#supplementary-material

References

Anderson, M. C., Banker, R. D., and Janakiraman, S. N., (2003). Are selling general and administrative costs “sticky”? J. Account. Res., 41(1): 47–63. doi:10.2307/3542244

Banker, R. D., Byzalov, D., and Chen, L. T. (2013). Employment protection legislation, adjustment costs and cross-country differences in cost behavior. J. Account. Econ. 55 (1), 111–127. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2012.08.003

Conrad, K., and Wastl, D. (1995). The impact of environmental regulation on productivity in German industries. Empir. Econ. 20, 615–633. doi:10.1007/BF01206060

Dong, Z., and Wang, H. (2019). Local-neighborhood effect of green technology of environmental regulation. China Ind. Econ. (01), 100–118. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2019.01.006

Fan, Q., and Zhang, T. (2018). A study of environmental regulations and pollution abatement mechanism on China's economic growth Path. J. World Econ. 41 (08), 171–192.

Fu, J., and Li, L. (2010). A case study on the environmental regulation, the factor endowment and the international competitiveness in industries. J. Manag. World (10), 87–98+187.

Gerald, M. M. (2002). William easterly the elusive quest for growth: Economists' adventures and misadventures in the tropics. J. Comp. Econ. 30 (1), 220–222. doi:10.1006/jcec.2001.1755

Gray, W. B., and Shadbegian, R. J. (2003). Plant vintage, technology, and environmental regulation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 46 (3), 384–402. doi:10.1016/S0095-0696(03)00031-7

Gray, W. B. (1987). The cost of regulation: OSHA, EPA and the productivity slowdown. Am. Econ. Rev. 77, 998–1006. doi:10.1016/0038-0121(88)90025-0

Hall, B. H. (2002). The financing of research and development. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 18 (1), 35–51. doi:10.1093/oxrep/18.1.35

Hao, Y., Xin, Q., and Liu, X. (2014). Regional difference, enterprise investment and quality of economic growth. Econ. Res. J. 49 (03), 101–114+189.

Jia, S., Yang, C., Wang, M., Jia, S., Yang, C., Wang, M., et al. (2022). Heterogeneous impact of land-use on climate change: Study from a spatial perspective[J]. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 510. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.840603

Jiang, F., Wang, Z., and Bai, J. (2013). The dual effect of environment regulations’ impact on innovation-an empirical study based on dynamic panel data of jiangsu manufacturing. China Ind. Econ. (07), 44–55.

Jin, H., Qian, Y., and Weingast, B. R. (2005). Regional decentralization and fiscal incentives: Federalism, Chinese style. J. Public Econ. 89, 1719–1742. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.11.008

Johnstone, N., Hascic, I., and Popp, D. (2010). Renewable energy policies and technological innovation: Evidence based on patent counts. Environ. Resour. Econ. (Dordr). 45 (1), 133–155. doi:10.1007/s10640-009-9309-1

Ju, X., Dic, L., and Yu, Y. (2013). Financing constraints, working capital management and the persistence of firm innovation. Econ. Res. J. 48 (01), 4–16.

Li, C., Lu, X., and Lu, J. (2018). The impact of local government competition pressure on regional production efficiency loss. China Soft Sci. (12), 87–94. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-9753.2018.12.008

Li, H., Tang, Y., and Zuo, J. (2013). On the selection of innovation financing resources: Based on the financing structure and the innovation of listed-company in China. J. Financial Res. (02), 170–183.

Li, H., and Zhou, L. A. (2005). Political turnover and economic performance: The incentive role of personnel control in China. J. Public Econ. 89 (9-10), 1743–1762. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.06.009

Li, W., Du, J., and Zhang, H. (2017). Do R&D subsidies really stimulate firms’ R&D self-financing investment: New evidence from China’s listed firms. J. Financial Res. (10), 130–145.

Liu, B., and Zhang, L. (2018). Who are stuck with the stickiness of de-capacity: State-owned or non-state-owned enterprises. Nankai Bus. Rev. 21 (04), 109–115. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1008-3448.2018.04.011

Liu, Y., and Zhao, P. (2018). The impact of local official governance on urban green growth China. J. Econ. 5 (4), 45–78. doi:10.16513/j.cnki.cje.2018.04.003

Luo, D., She, G., and Chen, J. (2015). A new Re-examination of the relationship between economic performance and local leader’ promotion: New theory and new evidence from city-level data. China Econ. Q. 14 (03), 1145–1172. doi:10.13821/j.cnki.ceq.2015.03.014

Pan, A., Liu, X., Qiu, J., and Shen, Y. (2019). Can green M&A of heavy polluting enterprises achieve substantial transformation under the pressure of media. China Ind. Econ. 12 (02), 174–192. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.20190131.005

Pan, Y., Dai, Y., and Li, C. (2009). Political connections and government subsidies of companies in financial distress: Empirical evidence from Chinese ST listed companies. Nankai Bus. Rev. 12 (05), 6–17. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1008-3448.2009.05.003

Pargal, S., and Wheeler, D. (1996). Informal regulation of industrial pollution in developing countries: Evidence from Indonesia. J. Political Econ. 104 (6), 1314–1327. doi:10.1086/262061

Porter, M. E., and Linde, C. V. D. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 9 (4), 97–118. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.97

Qian, Y., and Roland, G. (1998). Federalism and the soft budget constraint. SSRN J. 88 (5), 1143–1149. doi:10.2139/ssrn.149988

Qian, Y., and Weingast, B. R. (1997). Federalism as a commitment to preserving market incentives. J. Econ. Perspect. 11 (4), 83–92. doi:10.1257/jep.11.4.83

Ren, S., Hao, Y., and Wu, H. (2022). How does green investment affect environmental pollution? Evidence from China. Environ. Resour. Econ. Dordr. 81, 25–51. doi:10.1007/s10640-021-00615-4

Ren, S., Zheng, J., Liu, D., and Chen, X. (2019). Does emissions trading system improve firm’s total factor productivity - evidence from Chinese listed companies. China Ind. Econ. (05), 5–23. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2019.05.001

Su, X., and Zhou, S. (2019). Dual environmental regulation, government subsidy and enterprise innovation output. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 29 (03), 31–39. doi:10.12062/cpre.20181004

Su, Y., Li, Z., and Yang, C. (2021). Spatial interaction spillover effects between digital financial technology and urban ecological efficiency in China: An empirical study based on spatial simultaneous equations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (16), 8535. doi:10.3390/ijerph18168535

Tang, R., and Liu, H. (2012). The pattern of dual competition: An analysis of local governments’ behaviour changes in China. J. Public Manag. 9 (01), 9–16+121122. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-6162.2012.01.002

Wang, J., and Liu, B. (2014). Environmental regulation and enterprise’ TFP –an empirical analysis based on China’s industrial enterprises data. China Ind. Econ. (03), 44–56. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2014.03.004

Wang, S., and Xu, Y. (2015). Environmental regulation and haze pollution decoupling effect–based on the perspective of enterprise investment preferences. China Ind. Econ. (04), 18–30. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2015.04.003

Wu, H., Hao, Y., and Ren, S. (2020a). How do environmental regulation and environmental decentralization affect green total factor energy efficiency: Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 91, 104880. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104880

Wu, H., Xu, L., Ren, S., Hao, Y., and Yan, G. (2020b). How do energy consumption and environmental regulation affect carbon emissions in China? New evidence from a dynamic threshold panel model. Resour. Policy 67, 101678. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101678

Yang, Q., and Zheng, N. (2013). Is the competition for local leadership promotion a scale competition, A championship or a qualifying competition? J. World Econ. 36 (12), 130–156. Available at: Https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=SJJJ201312008&DbName=CJFQ2013.

Yuan, Y., and Xie, R. (2014). Research on the effect of environmental regulation to industrial restructuring – empirical test based on provincial panel data of China. China Ind. Econ. (08), 57–69.

Zhang, C., Lu, Y., Guo, L., and Yu, T. (2011). The intensity of environmental regulation and technological progress of production. Econ. Res. J. 46 (02), 113–124.

Zhang, C., Su, D., Lu, L., and Wang, Y. (2018). Performance evaluation and environmental governance: From a perspective of strategic interaction between local governments. J. Finance Econ. 44 (5), 4–22. doi:10.16538/j.cnki.jfe.2018.05.001

Zhang, M., and Song, Y. (2021). Environmental performance: From soft constraints to substantial accountability. Assess. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 31 (2), 34–43. doi:10.12062/cpre.20200626

Zhou, L. (2007). Governing China’s local officials:an analysis of promotion tournament model. Econ. Res. J. (07), 36–50.

Zhou, Y., Pu, Y., Chen, S., and Fang, F. (2015). Government support and development of emerging industries – a new energy industry survey. Econ. Res. J. 50 (06), 147–161. Available at: JournalArticle/5b3bfca0c095d70f009dcbfd. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2022.07.013

Keywords: ecological civilization, technology investment, government subsidies, environmental regulation, quasi-natural experiment

Citation: Chen M, Chen Y, Jiang C and Ran M (2022) Does the construction of an ecological civilization promote firm technology investment? a Quasi-natural experiment. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:1002506. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.1002506

Received: 25 July 2022; Accepted: 26 September 2022;

Published: 13 October 2022.

Edited by:

Haitao Wu, Beijing Institute of Technology, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Chen, Chen, Jiang and Ran. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yulei Chen, eXVsZWlfY2hlbjg4QDE2My5jb20=; Chengxin Jiang, ODQ5Mzg3MzczQHFxLmNvbQ==

Meijin Chen

Meijin Chen Yulei Chen2*

Yulei Chen2*