- 1Institute of Business Management, Karachi, Pakistan

- 2School of Economics and Management, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China

- 3Department of Business Administration, ILMA University, Karachi, Pakistan

- 4Department of Marketing, College of Business Administration, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 5Business Administration Department, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

This article seeks to study how the extensive usage of social networking sites (SNSs) and interaction in consumer-to-consumer (C2C) communities influence brand trust. Social networking sites have impacted internet commerce in a technologically advanced era; it connects global users. Social media ads have changed our thinking; new market trends are reshaping the business industry. This study empirically investigates a model based on media richness theory and social capital theory. Using data collected from users who conducted transactions on these sites, a theoretical model was developed to analyze the inspirations behind trust. The results show that Instagram’s media-rich platform enhances social capital and a sense of virtual community between its members, affecting trust. Instagram usage intensity does not immediately affect brand trust, but it has an indirect effect; community trust also positively influences brand trust. This study defines the role of a sense of virtual community (SOVC) and social capital (SC) in C2C communities only. This study delivers insights to managers on how to increase brand trust via SNSs. Prior studies on social commerce do not apply to C2C communities on social media platforms, especially Instagram. This study presents a novel standpoint of social capital and media richness structures as precursors of brand trust in C2C communities.

Introduction

Social networking sites (Sundararaj & Rejeesh, 2021), have highly influenced the online business paradigm in this tech-oriented era. It creates a close connection between users in different corners of the world (Verduyn et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2021a). Consumers are inclined to become members of the different customer-to-customer (C2C) communities for various reasons; for instance, it helps them connect with the world, develop an extended social circle without boundaries, enhance their ways of life, and enjoy the creative content available on the platform (Koranteng et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2021b; Khan et al., 2022a).

C2C communities (Kwon et al., 2020), develop and improve the interaction between the users and the platform. Highly integrated communities on different platforms fulfill the purpose of online shopping in this online world. Companies increasingly use social networking platforms to communicate and connect with their customers and grow their businesses through diversification (Ruttell, 2018; Khan et al., 2022f; Li et al., 2022). C2C communities are considered highly reliable for firms to communicate and connect with their customers to develop business with the help of diversity. Moreover (Phua et al., 2017; Tanveer et al., 2021a; Khan et al., 2021c; Khan et al., 2022b), the advertisements on social networking platforms have transformed the way of thinking; in this new time, new and advanced market patterns are evolving the business industry.

Previous researches have established a direct relationship between a Sense of Virtual Community (SOVC) and purchase intention (Ku et al., 2019; Yao et al., 2021); the information users receive on these platforms carries a high potential and can influence consumer buying patterns. In these platforms, users have the value addition of rich media capabilities; It helps every individual to create influence in the community (Lei et al., 2021; Rizmi et al., 2021). Once Users start to view C2C communities as reliable sources of information, new chances for building complete brand trust and awareness, and viral advertising platforms, emerge into a whole new marketplace (Ku et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2021d).

Numerous studies have developed research to represent the impact of these online (Akrout & Nagy, 2018; Vohra & Bhardwaj, 2019; Priharsari et al., 2020), feedback-driven platforms, and their effectiveness in structuring the consumer’s buying behavior. It firmly declares that the increased buying power of some consumers will increase the level of trust among other members, leading to increased engagement of members in the community (Priharsari et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2022c). The development of faith among platform users would significantly create gross social capital.

Prior studies have also focused mainly on the business-to-business (B2B) business model (Tao & Wei, 2019; Rubio et al., 2020; Rodríguez-López, 2021), and they comprise a limited contribution to the B2C model, and we found a gap in the research on C2C communities. As these dynamics of online communities are a significant shift in this paradigm, there is an extensive need to research this area (Kao et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2021e; Khan et al., 2021f). C2C communities are a hybrid of social trade and C2C communities equipped with highly integrated social networks. These days, brands are conducting R&D to study the influence of these C2C communities and the key factors that motivate users to transact on these platforms.

Former studies (Jansom & Pongsakornrungsilp, 2021; Yang et al., 2020; W. K. S. Leung et al., 2019; Leeraphong & Papasratorn, 2018) have extensively elaborated that consumers’ purchase intention drives the authority to create decision-making power among the members depending upon users’ age, gender, understanding level, and personality traits. It has been established that familiar technology individuals with quick decision-making power tend to boost engagement on these online platforms. Multiple factors with an asymmetric pattern can contribute to consumers’ purchase intention, for example, discounts, easy accessibility, availability, and quality of products (Vrontis et al., 2018). However, none of the studies have addressed the role of C2C networks, including Instagram, in creating brand trust.

Instagram has the 4th most users of any application and is one of the essential marketplaces globally with 1.074 billion active users. Five hundred million people use Instagram stories daily, and the content sharing from these 500 million community members contributes to a significant share of the business dynamics of Instagram. On Average, 95 million photos and videos are shared on Instagram daily, 63% of Instagram users check the app at least once daily, and 42% open the app multiple times on the same day (Tanveer et al., 2021b; Rasool et al., 2021; Instagram, 2022). These stats help us understand that Instagram is a virtual platform contributing very aggressively to designing C2C communities in an online marketplace.

Our first contribution to this study is to select Instagram as an online platform under research here due to its vast market share in the online community. If we analyze the influence of Instagram on business, 36.2% of B2B decision-makers use Instagram to search for new products, and 16. 90% of users follow at least one brand on Instagram. The demographics of Instagram as of 2021; 52% of Instagram’s audience identified as female, and 48% identified as male (Instagram Statistics You Need to Knowc, 2020; Instagram Revenue and Usage Statistics, 2022). These states create opportunities for the need for extensive research on Instagram and its C2C communities to analyze its influence on online shopping.

Our second contribution to this paper is; that we proposed the construct of brand trust in online communities. We created and analyzed the effects of brand trust in the C2C community. As previous research has mainly focused on consumer purchase intention, we would focus on brand trust because it's integral in driving the statistics of online consumer behaviors. Besides, living in this integrated, tech-oriented society, we need to analyze the future of the virtual markets and the essence of the C2C communities of Instagram to design business orientation more progressively.

Literature review

Instagram and C2C communities

The daily use of social networks is increasing, social networks have become a B2C market for companies for business activities, and the application of social commerce is not limited to business (Kumar et al., 2022). Ordinary members of the social network communities can become sellers and buyers. After seeing recommendations, ratings, and reviews, these platforms are in demand and followed by users (Maravic, 2013; (Tanveer, 2021).

The website of the C2C networks is based on the demand of the community and its platform members since they are involved in various online businesses. In contrast, the C2C social trading platform differs from other platforms in terms of functions and uses (Allen, 2014). Consumers’ interactions are carried out through various C2C platforms (Cuevas-Molano et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2022a), such as eBay, OLX, Craigslist, Instagram, etc. Online transaction sites allow consumers to bid on products and act as intermediaries in a wide geographic area, directing buyers’ payments to sellers. These sites have also developed various buyer protection plans to protect buyers from the possibility of dealing with undisclosed sellers (Zhou et al., 2022b; Kumar et al., 2022).

Commercial bulletin platforms (Ramle and Kaplan, 2019) allow people to publish product promotions, payments and deals carried out following the mutual agreement of the buyer and the seller. Consumers tend to transact within their geographic area (Nalewajek & Macik, 2013; Bandidniyamanon, 2014), although the coverage of these advertising platforms is much broader. Instagram is a social commerce platform that provides nearly experience for transactions between consumers and can create local communities where any community member can post product news to win prospective buyers or sellers (Pilar et al., 2019).

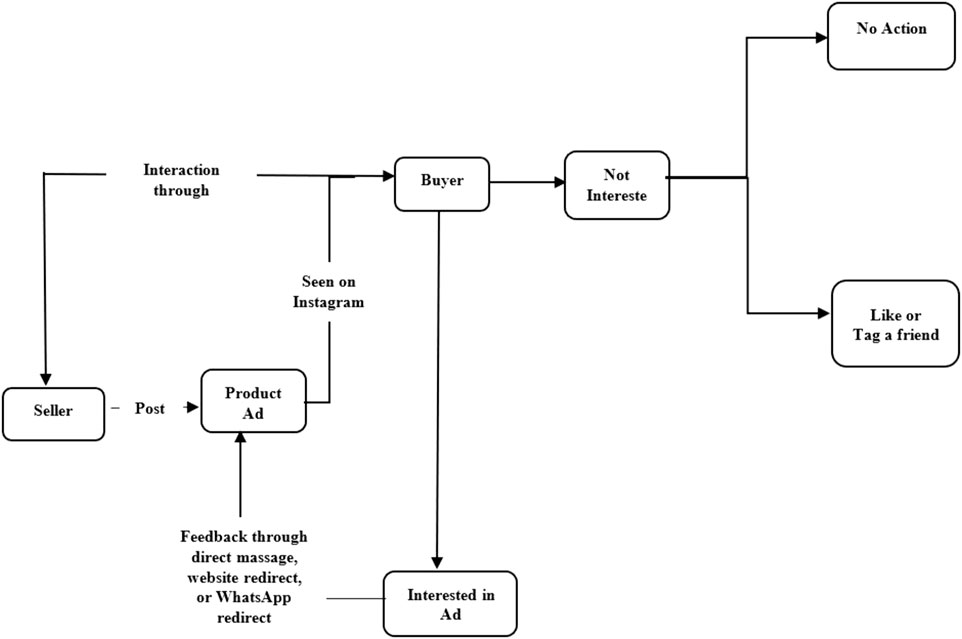

In addition (Casaló et al., 2021), the networks on Instagram help spread information across the Internet. It is conceivable that it could reach many latent buyers, even in the community where the ad is published as shown in Figure 1. The fundamental difference between the website’s virtual business design (Da Silva and Núñez Reyes, 2022), along with “Instagram” social business platform design lies in the combination of features, for example, the rich details on Instagram and the behavioral responses (for example, the severity of use) and collective structure (for example, the ABC). The research on the social environment of Instagram users (Oltra et al., 2021) is limited to the research on the buying habits of Instagram “buying and selling” groups. With the launch of the Instagram market community function, the C2C social e-commerce area on Instagram has brought hope to researchers.

Media richness theory

In 1986, Richard Daft and Robert Lengel first described “media richness” (Daft and Lengel, 1986); media richness represents the density of learning conveyed through a particular media. Face-to-face communication (Dennis & Kinney, 1998), is the richest medium because it allows signals from language content, tone, facial expressions, gaze direction, gestures, and postures to conduct interpersonal communication simultaneously. Before the emergence of electronic media, media richness theory (MRT) was developed (Simon & Peppas, 2004) to help managers in a business environment decide which media to convey information most effectively. Rich media, such as conversations and phone calls, are considered best for unconventional messages, while the lean press, such as unaddressed notes, is suitable for regular news.

Over the past 20 years (Valacich et al., 1994), media richness has expanded to describe the strengths and weaknesses of new media, from email to websites, video conferencing, voice mail, and instant messaging. The richness of the media (Alamäki et al., 2019), deserves to be understood by more people because people make decisions about the media all day long without considering the consequences of media choices and the fit between the information content and the media. Humans have adapted to their environment by living in close-knit and stable social groups (El-Shinnawy & Markus, 1997); face-to-face communication has been the only way of communication for hundreds of thousands of years; until about 5,000 years ago, the concept of media selection did not exist because it was face-to-face or nothing except the smoke signal. Clear speech and language complement the rich voices, facial expressions, eyes, gaze, gestures, and postures our ancestors relied on, creating a rich and potentially highly nuanced communication repertoire (Alamäki et al., 2019).

Social capital theory

Social capital (Schmid and Robison, 1995), enables people to cooperate effectively to achieve a common goal or objective. It allows society or organizations (Kreuter and Lezin, 2002), such as businesses or nonprofits, to work together through trust and shared identities, norms, values, and relationships. In short, social capital benefits the whole of society through social connections (Lin et al., 2001). Therefore, research on how social capital works or does not works spans all the social sciences.

Although social capital has been used recently (Swanson et al., 2020), the concept that social relationships can bring productive results for individuals or groups has long been explored. It is often described (Häuberer, 2011; Zhang et al., 2022), as how citizens or community members work together to live in harmony, but this word can have different meanings, depending on how it is applied. Social capital (Kim & Cannella, 2008), is no longer limited or partial in scope; it is often used to describe relationships that contribute to business success. It can be said that it is considered as valuable as financial or human capital. The Internet and Internet users are prime examples of how social capital (X. Y. Leung et al., 2021) operates commercially and enable professionals to form social connections in many forms. Usually, in global links, many jobs are filled through informal networks rather than job listings; this is what social capital is in action.

Hypothesis development

Media richness and social capital

Media Richness Theory (F.-C. Tseng et al., 2019) refers to a platform’s ability to replicate the information over time; the richness of a platform promotes the righteous interpretation of the content; it has the components of clarity, certainty, unambiguity, and easy access. The degree of richness variates based on platforms (Choi, 2019); in the case of Instagram, the existence of rich options (comments, shares, tags, posts, videos, images, etc.) qualifies for a massive portion of media richness. The social relationships of members on virtual platforms intend to increase value between similar people and create bridges between diverse individuals, which plays a vital role in generating the community’s social capital (Xiao et al., 2021).

The media richness of virtual platforms (Rice, 1992) enhances the chance of increasing social capital. Individuals in C2C communities interact via shared, rich sources of communication; that directly boost social capital (Liao & Teng, 2018). Users with different natures of relationships contribute to the community’s social capital with the help of influence each one of them carries (Gyamfi & Williams, 2017). The increased interaction of members in C2C communities elevates the social capital of the platform. Hence, we develop the following hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 1. Instagram’s media richness positively affects the social capital of its C2C communities.

Media richness and instagram’s usage intensity

The richness of medium (Voorveld et al., 2018), apprises to be a primary driver in achieving the maximized usage intensity of a platform. In Instagram, Feedback-driven features and rich interactive communication items help users contribute to the platform’s usage intensity (Shahbaznezhad et al., 2021). It increases the chances of initiating new relationships between the community members; users can mobilize their social networks and connections with the help of available rich functionalities. The hashtag feature of Instagram (Giakoumaki & Krepapa, 2020), sets the trends. Almost every individual participates; hashtags also play a crucial role in marketing over Instagram.

Emerging properties that promote the richness of the medium have a direct relationship with the usage intensity of the platform (Chemela, 2019). Rich mediums help users develop a psychological bonding with Instagram and contain a considerable portion of their day-to-day activities (Camacho-Miñano et al., 2019). Instagram’s rich functionalities effectively increase the usage intensity. Thus, we are proposing the below hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 2. The media richness of Instagram positively and directly affects Instagram usage intensity.

Media richness and trust in C2C community

Trust in social media platforms influence human behavior (Yen & Chiang, 2021); C2C communities are platforms where people are drawn together based on their shared interests, values, hobbies, etc. The more frequently members interact with each other, the more trust is developed, and the bond enhances stronger (Shao & Pan, 2019). Rich mediums tend to improve members’ belongingness quickly (Quoquab & Mohammad, 2022). The richness of the medium on Instagram creates value for the user and shares a significant portion in building trust in the C2C community. The features of Instagram (W. K. Leung et al., 2019), that publicize the trust factors, including posting media content, availability of profile views, instant feedback, and recommendations are valuable in providing a qualitative assessment to other community members based on their experience.

Media richness is essential to building community trust (Chao et al., 2014). The availability of rich functionalities of Instagram creates a value of trust by reducing possible unreliability and improving the chances of transactions. The existence of mutual friends (Wang et al., 2021), also helps build reliance and trust in these C2C Communities. Hence, we designed the following hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 3. Instagram’s media richness highly affects trust in the C2C community.

Media richness and sense of virtual community

A sense of virtual community (SOVC) refers to getting insight and support (Koh et al., 2003), sharing information, and accepting among community members. The media richness of Instagram creates value because of its capacity to help members; to interact without boundaries, easy accessibility, approach to new information and ideas, and develop a sense of trust and reliability among the members (Chen & Chang, 2018). The platform provides rich media capabilities (Chua & Jiang, 2006) when users share their day-to-day experiences in posts that include text, images, videos, and emojis. Once the users find the forum is causative in their personal life, they feel an emotional attachment towards it, which originates a sense of virtual community.

The main element that drives C2C communities is the media richness of the platform (Bergin, 2016). When community members share their experiences with others, it steers to an improved SOVC. The administrative control features help to comply with and moderate online activities. Moreover (Koh et al., 2003), the standard code of conduct for the community is well established among the members. It develops a stronger bond that reflects SOVC. We propose that the media richness of Instagram increases the SOVC in the community, so we adapt the following hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 4. Media richness attributes of Instagram directly influence SOVC in its C2C communities.

Instagram usage intensity and social capital

Keeping Instagram’s usage intensity in view, we can establish that it has become an essential part of people’s lives. There will be 1.074 billion Instagram subscribers globally in 2021. On average, every post on Instagram contains 10.7 hashtags that directly influence social capital. 71% of the active users on Instagram are under 35 years (Instagram, 2022). According to the statistics, an Instagram user spends 53 min on this app every day (Gunaningrat et al., 2021). The more interaction among users, the more it influences the social capital of its communities (Daft & Lengel, 1986b); developing networks via these C2C communities complement the money in numerous ways.

Usage intensity parameters of Instagram consider the socialization of users with other members; establishing diversity in the community creates social capital (Jab\lońska and Zajdel, 2020). The platforms where users communicate and build connections across the globe (Sholihat, 2019), the integration of these platforms remark favorably by the richness of the medium that highly enhances the usage intensity of the forum. Hence, this allows us to test the below hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 5. Instagram usage intensity positively influences the social capital in its C2C communities.

Social capital and trust in C2C community

In the virtual environment (Junaidi and Chih, 2020), social capital is a predecessor for developing trust among the communities; for instance, a new member would not be able to trust the community’s resources primarily, but with time and influence from other members (Greiner, 2010; Huang et al., 2017), and by inspecting and getting positive feedback from friends or acquaintances, the members would eventually feel comfortable with the community. It contributes to the development of trust, and we can assert that the probability of transaction in these C2C communities is a derivative of social capital and trust (Tabish et al., 2020).

Online communities like Instagram (Xie et al., 2021), which already have maximized social capital, run by a set of rules, pertain to stringent levels of security for their members, and the empathic accuracy that members achieve after interacting within the community creates promising effects in the origination of trust (Trehan and Sharma, 2020). We could easily see how these communities’ gross social capital significantly influences trust in C2C communities. Hence, we support the following hypothesis.

HYPOTHESIS 6. The extent of social capital in Instagram C2C communities positively and directly affects trust in C2C communities.

Sense of virtual community and trust in C2C community

Trust is the main factor that drives consumer behavior (Zhao et al., 2019), especially in an online environment; the risk factors upswing for the transactions made via these communities (Tsai & Hung, 2019), from an outsider’s viewpoint, a virtual community is presented as a shared family. A strange sense of community is established among the members, and quickly they begin to trust the shared resources (Luo et al., 2020); attaining this stage, a platform becomes doable for the user to consume, utilize and share with others; even among the members outside the community, this phase offers intensification to hit the extreme potential of user engagement on the platform.

SOVC helps create a sense of belongingness in the community, and Trust in these communities directly impacts business transactions (Hawlitschek, 2018; Luo et al., 2020). Reputation-based governance mechanisms for online social networks help increase the SOVC. This positive effect of SOVC capitalizes on building trust in these C2C communities. Hence, we design the below hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 7. SOVC in C2C communities directly and positively affects trust in C2C communities.

Instagram usage intensity and brand trust

Brand trust is a valuable asset (Djafarova and Bowes, 2021); it reflects the expectation of customers from your business and how much confidence they have in your brand; It shows the reputation of your products and services in the marketplace. While dealing in a virtual environment, many things can affect brand trust. However (Harrigan et al., 2021), representing the community’s social capital, Electronic Word of Mouth (EWOM) and Tie-strengths’ role are the two main vital factors influencing brand trust. The rich medium capabilities of Instagram help a user promote brand trust with just a click (Sari & Yulianti, 2019).

The gross social capital of Instagram creates an impact based on other community members’ experiences (Kemeç, 2020; Harrigan et al., 2021), and it motivates the users to trust a specific brand. Stronger ties bring the most influence over EWOM. In contrast (Kemeç, 2020; Khan et al., 2022d), weaker links help spread information, thus improving social capital and further achieving brand trust. Hence, it allows us to test the below hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 8. The online social capital of C2C communities affects brand trust.

Social capital and brand trust

Trust is a dynamic parameter for exchange in the relationship between buyers and sellers (Bowden et al., 2018); the usage intensity of Instagram is highly valued to brand trust. The strength and sanctity of C2C communities significantly influence brand awareness among the members since each individual can partake in promoting or rejecting the brand (Jeong et al., 2021). Therefore (J. Kim et al., 2020), exploit brand trust. Consequently, focusing on customer relationships is far more needed today than ever in these C2C communities to achieve brand trust (Meek et al., 2019).

Brand trust modifies a cumulative association with Instagram usage intensity (Bowden et al., 2018; C. T. Lee and Hsieh, 2016); members of C2C communities can influence other members and draw their attention to a specific brand. Instagram usage intensity reinforces the bond between members of C2C communities, thereby re-creating and modifying the linking value among consumers (Liu & Jiang, 2020; Khan et al., 2022e). Thus, we can postulate the below hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 9. The Usage Intensity of Instagram positively and directly affects brand trust.

Trust in virtual communities and brand trust

Brand trust directly impacts product relationship parameters in online shopping via C2C communities (Kamboj et al., 2018). Numerous product characteristics might influence consumer purchasing (Casaló et al., 2008; Kang et al., 2016), for instance, product quality, customer satisfaction level, convenience risks, relational factors, etc. Also, in the previous arguments (Tabish et al., 2022), trust is one of the most crucial components in evolving consumer buying behaviors. Many kinds of researchers (Mpinganjira, 2018; Vohra & Bhardwaj, 2019; Priharsari et al., 2020) have conquered that the suggestion or recommendations from friends and family members have a significant impact on the buying pattern of consumers and are pretty more potent than the marketing strategies adopted by influencers or brand ambassadors.

Instagram’s reputation mechanisms are easy to comprehend and follow and carry a massive potential in creating the virtual marketplace as a trustworthy platform for its community members (D. J. Kim et al., 2022). So, we can examine that trust in the C2C community directly relates to the expansion of brand trust. Hence, we develop the following hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 10. Trust in the C2C community positively and directly affect brand trust.

Sense of virtual community and brand trust

SOVC develops a unification among community members (Yao et al., 2021) and incorporates a significant role in predicting consumer behavior in C2C communities. It motivates the members to make the transaction with a specific brand (Chiang et al., 2018); brand trust is the other most vital determinant in online shopping. The influence of SOVC reflects the buying pattern of consumers (González-Anta et al., 2021); the brand’s image dictates the trade, as the feedback established for a seller will either boost or knock down the sales, dependent upon the reviews from the buyers of the community.

SOVC develops a constantly fluctuating atmosphere among the members that eventually encompasses a convincing impact on brand trust (Ku et al., 2019). C2C communities have and will continue to have a theatrical influence that keeps modifying brand trust based on the continuously changing feedback from members (Shang et al., 2006; Jung et al., 2014). Hence, we have the aptitude to propose the following hypothesis:

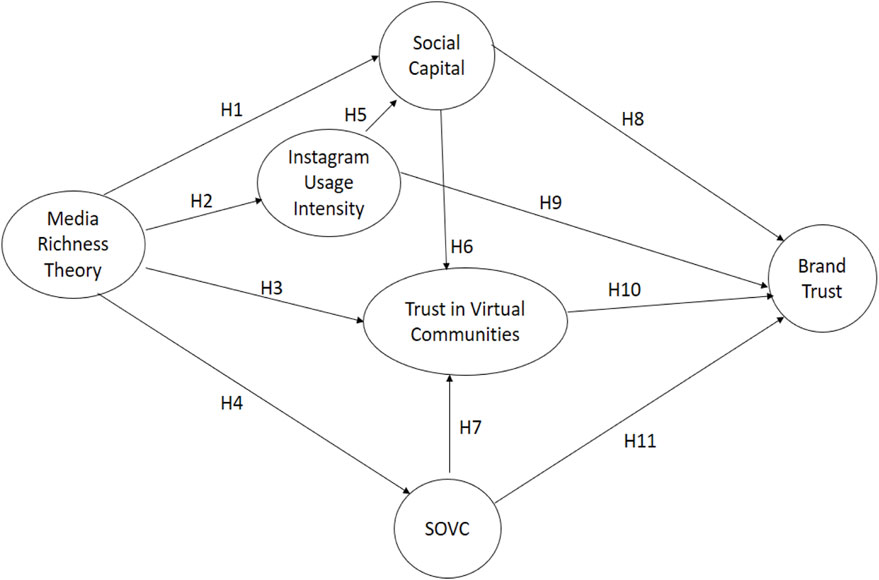

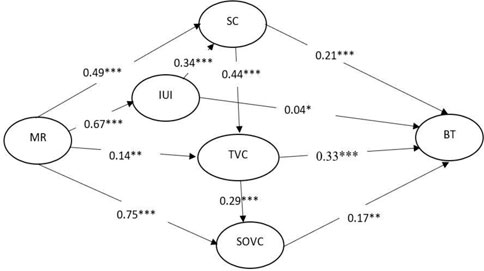

HYPOTHESIS 11. SOVC positively and directly affects brand trust.Thus, on the bases of the above discussion, we can propose the following conceptual framework (Figure 2).

Research method

Data collection and pre-processing

We chose business school students as the target audience of this study. There are two reasons for this; first previous studies show that students are more inclined to use social media. Second, Pakistan has 10.8 million Instagram users till January 2021, out of which 4.8 million users have an age bracket of 18–24 years old. The questionnaires have been distributed to the leading universities of Pakistan’s three most popular cities: Karachi, Lahore, and Peshawar. Data has been gathered from IoBM (Institute of business administration), IU (Iqra University), LUMS (Lahore University of Management and Sciences), and the University of Peshawar. A pretest was undertaken to confirm the validity and eliminate semantic issues. In the pretest, 79 of the 94 questionnaires gathered were legitimate. The reliability and validity analyses show that the overall Cronbach’s coefficient is 0.954. The Cronbach coefficients for all variables are more significant than 0.7, indicating that the questionnaire has a high level of internal consistency and the results are reliable. Additionally, the KMO is 0.947, and the Bartlett Spherical test result is statistically significant (p < 0.001), showing that the concepts have strong validity (J. Hair et al., 1998).

The expected sample was to explore the data from 600 different data sets. Out of which we received 446 responses, after removing invalid and unreliable data values, we had 421 answers, based on which we could find and calculate results. We have a validity rate of 94.39% on behalf of this data. The descriptive information of our dataset is as follows; 43% of our respondents were female, and 57% were males. The age bracket that most respondents belonged to is (20–30). We have been able to adapt the analysis that the users who make the transaction via these virtual communities, without a doubt, are well-educated, and young adults are more inclined towards the sophistication of experience on Instagram’s virtual communities.

Measurement variables

The construct scales were derived from the literature and tailored to the needs of the C2C communities. MRT: Media richness theory indicates that all communication mediums vary to attract and retain users for communicating and sharing over a specific platform (Webster and Trevino, 1995). Social Capital refers to the idea of creating a network due to shared norms, values, and understanding were adapted from (Williams, 2006). It creates a virtual bond between the users. Trust in VCs is the degree of reliance users have on the communities over a specific platform adapted from (Hur et al., 2011). It directly affects customer loyalty. Instagram’s Usage Intensity explains the degree of influence in the online world. Users are intrigued by the platform and to what extent it is going to influence the users to transact on these VCs via Instagram were adapted from (Ellison et al., 2007). SOVC is created and developed when users can feel valuable and trustworthy, share and gain reviews and feedback from peers using the same platform adapted from (Blanchard, 2007). Brand Trust is affected by thoughts and feedback communities hold to appreciate or criticize the brand adopted (Jarvenpaa et al., 1998). The overall experience of the virtual community affects brand trust. The 5-Point Likert scale has been used, the universal scale used to measure attitudes and opinions.

Results of data analysis

We used the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) method to test the main instrument’s assumptions. SEM is a tool for analyzing data from more than one source and can also be used to test theories (Ring et al., 1980). PLS is also an excellent way to check how well path models work (Marcoulides et al., 2009).

Measurement model construct reliability and validity

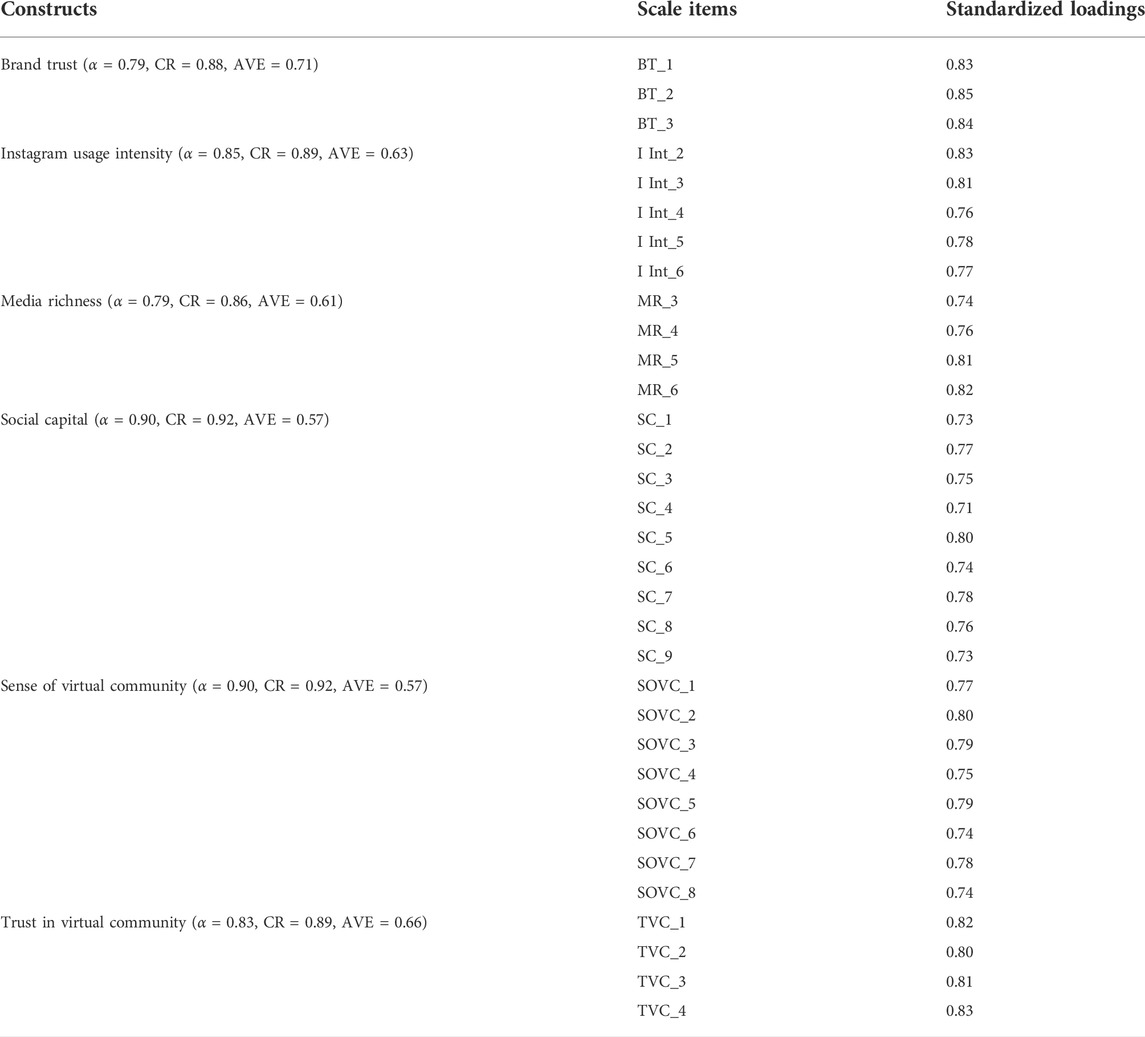

The measuring model was tested using Hair et al. (1998) as a guide. In our first set of data, there were 30 items. Four items were taken out during the pilot study because they didn’t fit together well. The factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted were used (AVE).

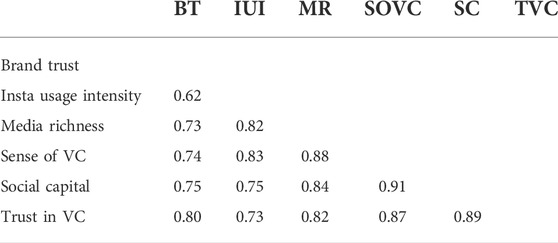

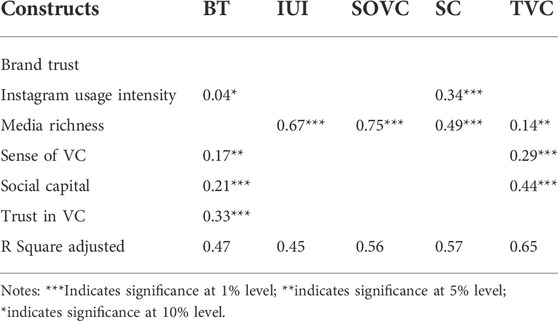

All factor loadings are greater than 0.7, which means the factor loading size is correct (J. F. Hair et al., 2010). CR and AVE both have to be at least 0.7 and 0.5. All constructs have CR values higher than 0.7 and AVE values more elevated than the threshold level. The results show good convergent validity (refer to Table 1). Discriminant validity looks at how different each construct measurement is from the others. All the distinct or unique constructs in the study have a Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) that is less than one (refer to Table 2). This means that all of the constructs are different and unique.

The structural model’s findings

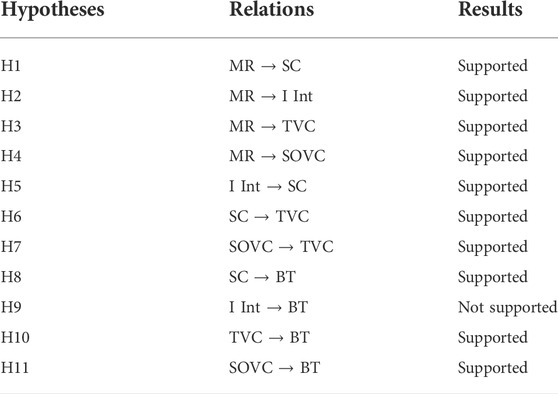

We used the partial least squares method and a bootstrapping algorithm with 5,000 bootstrap samples and 200 cases in each sample to test the hypotheses (J. F. Hair et al., 2011). Table 3 shows the structural model’s path coefficients and their importance. At the 5 % significance level, all routes were excellent and significant. The only ones that weren’t are Instagram uses intensity and brand trust. R-square values and structural paths were used to see if the model was suitable (Chwelos et al., 2001).

The model shows that social capital, trust in a virtual community, and SOVC concepts accounted for 47.6% of the differences in brand trust (R-square). This suggests that trust in a brand is affected by social capital, trust in a virtual community, and how users build their SOVC. The sense of virtual community caused 65% of the difference in community trust, the amount of media, and social capital.

Besides H9, all hypotheses were supported (Table 4). The results indicate that Instagram Usage Intensity has no direct effect on brand trust. However, increasing media diversity increases Instagram usage, positively impacting C2C community trust. On the other hand, the expected positive link between social capital and community trust obtained substantial support. Nevertheless, community trust is linked to a greater likelihood of brand trust. Together, the community’s high social capital and members’ trust in one another contribute to a strong brand’s credibility.

Surprisingly, the path coefficient between community trust and brand trust (0.33) is larger than the path coefficient between SOVC and brand trust (0.17), indicating that community trust has a more significant impact on brand trust than SOVC. Finally, as predicted, community trust has a beneficial effect on SOVC. The model’s significant paths are depicted in Figure 3.

Discussion

Instagram is an influential platform, carrying millions of communities focusing on a C2C experience wherein customers interact and transact with other social communities and have real-time exposure. Regarding media richness and social capital, the most important factors influencing a customer are the social capital created in the community and the richness of Instagram as a medium. These elements significantly impact virtual community trust in the long term, which persuades brand trust. The findings revealed that the medium’s richness directly transcends the enhancement of virtual community trust in the community members. However, the virtual community trust is evolved through two various channels. Initially, it is built via the social capital path, where a community’s social capital rises because of its medium richness. This has an impact on trust. Trehan & Sharma (2020) highlighted how interactivity and media richness positively affect social network characteristics and the increasing trend of social capital within social media platforms like Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook.

Furthermore, if customers practice Instagram more frequently, the possibility of exploring these communities is likewise increasing. As a result (Harrigan et al., 2021), they will begin interacting with the platform and the persons involved in these communities by exchanging thoughts, posting diversified advertisements, and hearing about other people’s experiences. This interaction will strengthen their trust in the C2C communities. The basis of virtual community trust is an essential prerequisite for brand trust. The virtual community trust and SOVC directly impact brand trust (Tsai and Hung, 2019). When members experience a sense of belonging to the community, they value their membership, which leads to an increased drive to participate in community communications, ultimately leading to increased brand trust.

The platform’s media richness (Liao and Teng, 2018) has a beneficial impact on SOVC. Most study participants were under 30, a generation that grew up in the internet age when distinctive humor and language give a sense of belonging to the community rather than being outside. This sense of being trapped inside can lead to SOVC. However, the findings align with the proposed hypotheses (Liao et al., 2020), i.e., media richness directly impacts virtual community trust. This indicates that media richness increases virtual community trust through emotional attachment to the platform. Richer and interactive media boost platform usage, which establishes trust over time.

The research model found stout results for the direct relationship between social capital and brand trust (Meek et al., 2019). Hedonic and functional products are available in Instagram transactional communities; hedonic product consumption is associated with social prestige and is viewed as an investment in social capital, whereas functional product consumption focuses on specific and operational benefits. As a result, social capital and brand trust have different strengths depending on product type. With substantial social capital (Bowden et al., 2018), users participate in transacting businesses on social platforms such as Instagram. Here social capital serves as a trust enhancer. This indicates that a bit of trust is essential before making any purchase. According to the findings of this study, rich media, in addition to other people’s experiences, helps to establish trust. The top social capital, as well as shared passionate relationships, impact brand trust. These findings are significant since this is one of the small numbers of studies to aim to describe the phenomenon.

Conclusion and managerial implications

As traditional internet transactions become less popular and social media transactions become more common, the significance of the community elements offered by social media platforms is becoming increasingly essential in determining a customer’s level of trust and pleasure. This research contributes to (Kang & Shin, 2016) by offering detailed evaluations of various aspects of Instagram’s C2C functioning, including social capital, trust, and SOVC. Establishing trust between members is necessary to complete transactions; from a strategic point of view, this observation is vital for online C2C platforms. These websites generate revenue solely by participation in online commerce. Because of this, they need to increase the total number of transactions and the number of subscribers they have.

Websites like Amazon, Upwork, Fiverr, and Olx may want to consider integrating a social network like Instagram into their platform to boost subscribers and brand trust. Incorporating social media into the domains of websites will allow prospective buyers to conduct fast inspections, such as seeing the sellers’ profiles, which may increase their trust in the transactions. The researchers discovered some fascinating outcomes linked to the platform’s media richness features (Heinonen et al., 2018). Customers want to connect through richer media, and good communication is the key to possible transactions. Instagram has recently announced that it will allow people to buy products without leaving the app. This gives social commerce groups on Instagram an exciting chance to create a seamless and secure way to sell and purchase items directly on Instagram.

Limitations and guidance for future research

Although the study only looked at two distinct kinds of online communities, it revealed some fascinating insights into the C2C transactions in Instagram groups. In the future, research should be carried out to investigate the effect a diverse media environment has on the many various kinds of communities. Because social commerce is a freshly developing research issue all over the globe, researchers will likely opt to expand the scope of this study to integrate cultural variations. This is because social commerce is a newly emerging research topic worldwide. An investigation into how the level of consumer trust in brands changes from one product category to the next has the potential to shed additional light on how customers behave in C2C Instagram groups. A more significant number of people may visit the community pages as a direct result of these shifting opinions of the brand’s dependability among consumers. In conclusion, the quality of advertising and how it may promote consumer interest in advertisements is an intriguing one that should be investigated in further research. This is because the topic can potentially encourage consumer interest in ads in various ways.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for this study as per local and institutional requirements

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The project was supported by the Open Research Fund of NJIT Institute of Industrial Economy and Innovation Management (No. JGKA202201) and the Foundation of State Key Laboratory of Public Big Data (No.PBD 2022-17).

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article would like to thank Prince Sultan University for its financial and academic support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akrout, H., and Nagy, G. (2018). Trust and commitment within a virtual brand community: The mediating role of brand relationship quality. Inf. Manag. 55 (8), 939–955. doi:10.1016/j.im.2018.04.009

Alamäki, A., Pesonen, J., and Dirin, A. (2019). Triggering effects of mobile video marketing in nature tourism: Media richness perspective. Inf. Process. Manag. 56 (3), 756–770. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2019.01.003

Allen, I. R. (2014). Virtual communities of practice: A netnographic study of peer-to-peer networking support among doctoral students [Ph.D. Thesis]. USA: Capella University.

Bandidniyamanon, M. J. (2014). Factors affecting to the purchasing behavior of female fashion clothing via instagram in bangkok [PhD thesis]. Bangkok: Thammasat university.

Blanchard, A. L. (2007). Developing a sense of virtual community measure. CyberPsychology Behav. 10 (6), 827–830. doi:10.1089/cpb.2007.9946

Bowden, J. L.-H., Conduit, J., Hollebeek, L. D., Luoma-aho, V., and Solem, B. A. A. (2018). The role of social capital in shaping consumer engagement within online brand communities. Handb. Commun. Engagem. 8, 491–504. doi:10.1002/9781119167600.ch33

Camacho-Miñano, M. J., MacIsaac, S., and Rich, E. (2019). Postfeminist biopedagogies of Instagram: Young women learning about bodies, health and fitness. Sport, Educ. Soc. 24 (6), 651–664. doi:10.1080/13573322.2019.1613975

Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., and Guinalíu, M. (2008). Fundaments of trust management in the development of virtual communities. Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing

Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., and Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2021). Be creative, my friend! Engaging users on Instagram by promoting positive emotions. J. Bus. Res. 130, 416–425. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.014

Chao, R.-M., Chang, C.-C., and Chang, W.-Y. (2014). Exploring the antecedents of trust from the perspectives of uncertainty and media richness in virtual community. Int. J. Web Based Communities 10 (2), 176–187. doi:10.1504/ijwbc.2014.060354

Chemela, M. S. R. (2019). The relation between content typology and consumer engagement in Instagram [PhD Thesis] Universidade CatÃlica Portuguesa.

Chen, C.-C., and Chang, Y.-C. (2018). What drives purchase intention on airbnb? Perspectives of consumer reviews, information quality, and media richness. Telematics Inf. 35 (5), 1512–1523. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2018.03.019

Chiang, I. P., Tu, S. E., and Wang, L. H. (2018). Exploring the social marketing impacts of virtual brand community engagement. Contemp. Manag. Res. 14 (2), 143–164. doi:10.7903/cmr.18086

Choi, S. (2019). The roles of media capabilities of smartphone-based SNS in developing social capital. Behav. Inf. Technol. 38 (6), 609–620. doi:10.1080/0144929X.2018.1546903

Chua, Z., and Jiang, Z. (2006). Effects of anonymity, media richness, and chat-room activeness on online chatting experience.

Chwelos, P., Benbasat, I., and Dexter, A. S. (2001). Research report: Empirical test of an EDI adoption model. Inf. Syst. Res. 12 (3), 304–321. doi:10.1287/isre.12.3.304.9708

Cuevas-Molano, E., Matosas-López, L., and Bernal-Bravo, C. (2021). Factors increasing consumer engagement of branded content in instagram. IEEE Access 9, 143531–143548. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3121186

Da Silva, F., and Núñez Reyes, G. (2022). The era of platforms and the development of data marketplaces in a free competition environment.

Daft, R. L., and Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Manag. Sci. 32 (5), 554–571. doi:10.1287/mnsc.32.5.554

Dennis, A. R., and Kinney, S. T. (1998). Testing media richness theory in the new media: The effects of cues, feedback, and task equivocality. Inf. Syst. Res. 9 (3), 256–274. doi:10.1287/isre.9.3.256

Djafarova, E., and Bowes, T. (2021). ‘Instagram made Me buy it’: Generation Z impulse purchases in fashion industry. J. Retail. Consumer Serv. 59, 102345. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102345

El-Shinnawy, M., and Markus, M. L. (1997). The poverty of media richness theory: Explaining people’s choice of electronic mail vs. voice mail. Int. J. Human-Computer Stud. 46 (4), 443–467. doi:10.1006/ijhc.1996.0099

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., and Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J. Computer-Mediated Commun. 12 (4), 1143–1168. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

Giakoumaki, C., and Krepapa, A. (2020). Brand engagement in self-concept and consumer engagement in social media: The role of the source. Psychol. Mark. 37 (3), 457–465. doi:10.1002/mar.21312

González-Anta, B., Orengo, V., Zornoza, A., Peñarroja, V., and Martínez-Tur, V. (2021). Understanding the sense of community and continuance intention in virtual communities: The role of commitment and type of community. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 39 (3), 335–352. doi:10.1177/0894439319859590

Greiner, M. (2010). Seller trust in C2C marketplaces: Who do you trust? AIS Electronic Library (AISeL).

Gunaningrat, R., Purwandari, S., Suyatno, A., and Hastuti, I. (2021). Consumer shopping preferences and social media use during covid-19 pandemic. J. Bisnisman Ris. Bisnis Dan. Manaj. 3 (2), 01–15. doi:10.52005/bisnisman.v3i2.42

Gyamfi, A., and Williams, I. (2017). Evaluating media richness in organizational learning. IGI global.

Hair, J., Andreson, R., Tatham, R., and Black, W. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. 5th. America: Prentice-Hall Inc. Unites States of America.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J., and Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective, 7. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 19 (2), 139–152. doi:10.2753/mtp1069-6679190202

Harrigan, M., Feddema, K., Wang, S., Harrigan, P., and Diot, E. (2021). How trust leads to online purchase intention founded in perceived usefulness and peer communication. J. Consum. Behav. 20 (5), 1297–1312. doi:10.1002/cb.1936

Hawlitschek, M. S. F. (2018). Trust in the sharing economy. Die Unternehm. 70, 26. doi:10.5771/0042-059X-2016-1-26

Heinonen, K., Jaakkola, E., and Neganova, I. (2018). Drivers, types and value outcomes of customer-to-customer interaction: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 28, 710–732. doi:10.1108/jstp-01-2017-0010

Huang, Q., Chen, X., Ou, C. X., Davison, R. M., and Hua, Z. (2017). Understanding buyers’ loyalty to a C2C platform: The roles of social capital, satisfaction and perceived effectiveness of e-commerce institutional mechanisms. Info. Syst. J. 27 (1), 91–119. doi:10.1111/isj.12079

Hur, W.-M., Ahn, K.-H., and Kim, M. (2011). Building brand loyalty through managing brand community commitment. Manag. Decis. 49, 1194–1213. doi:10.1108/00251741111151217

Instagram (2022). Age and gender demographics. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/248769/age-distribution-of-worldwide-instagram-users/.

Instagram statistics you need to know (2022). Sprout social. Available at: https://sproutsocial.com/insights/instagram-stats/.

Jab\lońska, M. R., and Zajdel, R. (2020). Artificial neural networks for predicting social comparison effects among female Instagram users. PloS One 15 (2), e0229354. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0229354

Jansom, A., and Pongsakornrungsilp, S. (2021). How instagram influencers affect the value perception of Thai millennial followers and purchasing intention of luxury fashion for sustainable marketing. Sustainability 13 (15), 8572. doi:10.3390/su13158572

Jarvenpaa, S. L., Knoll, K., and Leidner, D. E. (1998). Is anybody out there? Antecedents of trust in global virtual teams. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 14 (4), 29–64. doi:10.1080/07421222.1998.11518185

Jeong, S. W., Ha, S., and Lee, K.-H. (2021). How to measure social capital in an online brand community? A comparison of three social capital scales. J. Bus. Res. 131, 652–663. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.07.051

Junaidi, J., and Chih, W. H. (2020). The role of social capital on social commerce: An empirical study of Facebook users. Sustain. Compet. Advant. (SCA) 10 (1), 639–648.

Jung, N. Y., Kim, S., and Kim, S. (2014). Influence of consumer attitude toward online brand community on revisit intention and brand trust. J. Retail. Consumer Serv. 21 (4), 581–589. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2014.04.002

Kamboj, S., Sarmah, B., Gupta, S., and Dwivedi, Y. (2018). Examining branding co-creation in brand communities on social media: Applying the paradigm of Stimulus-Organism-Response. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 39, 169–185. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.12.001

Kang, M., Shin, D.-H., and Gong, T. (2016). The role of personalization, engagement, and trust in online communities. United Kingdom: Emerald.

Kang, M., and Shin, D.-H. (2016). The effect of customers’ perceived benefits on virtual brand community loyalty. Online Inf. Rev. 40, 1468. doi:10.1108/oir-09-2015-0300

Kao, P.-J., Pai, P., and Tsai, H.-T. (2020). Looking at both sides of relationship dynamics in virtual communities: A social exchange theoretical lens. Inf. Manag. 57 (4), 103210. doi:10.1016/j.im.2019.103210

Kemeç, U. (2020). The effect of influencer credibility on brand trust and purchase intention: A study on instagram [Master’s Thesis]. Istanbul, Turkey: Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

Khan, S. A. R., Godil, D. I., Jabbour, C. J. C., Shujaat, S., Razzaq, A., and Yu, Z. (2021e). Green data analytics, blockchain technology for sustainable development, and sustainable supply chain practices: Evidence from small and medium enterprises. Ann. Oper. Res. doi:10.1007/s10479-021-04275-x

Khan, S. A. R., Godil, D. I., Quddoos, M. U., Yu, Z., Akhtar, M. H., and Liang, Z. (2021d). Investigating the nexus between energy, economic growth, and environmental quality: A road map for the sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 29 (5), 835–846. doi:10.1002/sd.2178

Khan, S. A. R., Mathew, M., Dominic, P. D. D., and Umar, M. (2022d). Evaluation and selection strategy for green supply chain using interval-valued q-rung orthopair fuzzy combinative distance-based assessment. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 24, 10633–10665. doi:10.1007/s10668-021-01876-1

Khan, S. A. R., Ponce, P., Tanveer, M., Aguirre-Padilla, N., Mahmood, H., and Shah, S. A. A. (2021c). Technological innovation and circular economy practices: Business strategies to mitigate the effects of COVID-19. Sustainability 13 (15), 8479. doi:10.3390/su13158479

Khan, S. A. R., Ponce, P., Thomas, G., Yu, Z., Al-Ahmadi, M. S., and Tanveer, M. (2021f). Digital technologies, circular economy practices and environmental policies in the era of COVID-19. Sustainability 13 (22), 12790. doi:10.3390/su132212790

Khan, S. A. R., Ponce, P., Yu, Z., Golpira, H., and Mathew, M. (2022c). Environmental technology and wastewater treatment: Strategies to achieve environmental sustainability. Chemosphere 286 (1), 131532. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131532

Khan, S. A. R., Ponce, P., Yu, Z., and Ponce, K. (2022a). Investigating economic growth and natural resource dependence: An asymmetric approach in developed and developing economies. Resour. Policy 77, 102672. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102672

Khan, S. A. R., Ponce, P., and Yu, Z. (2021b). Technological innovation and environmental taxes toward a carbon-free economy: An empirical study in the context of COP-21. J. Environ. Manag. 298, 113418. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113418

Khan, S. A. R., Umar, M., Tanveer, M., Yu, Z., and Janjua, L. R. (2022f). “Business data analytic and digital marketing: Business strategies in the era of COVID-19,” in 2022 7th international conference on data science and machine learning applications (CDMA) (IEEE), 13–18.

Khan, S. A. R., Yu, Z., and Farooq, K. (2022e). Green capabilities, green purchasing, and triple bottom line performance: Leading toward environmental sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. doi:10.1002/bse.3234

Khan, S. A. R., Yu, Z., and Sharif, A. (2021a). No silver bullet for de-carbonization: Preparing for tomorrow, today. Resour. Policy 71, 101942. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101942

Khan, S. A. R., Yu, Z., Umar, M., and Tanveer, M. (2022b). Green capabilities and green purchasing practices: A strategy striving towards sustainable operations. Bus. Strategy Environ. 31 (4), 1719–1729. doi:10.1002/bse.2979

Kim, D. J., Salvacion, M., Salehan, M., and Kim, D. W. (2022). An empirical study of community cohesiveness, community attachment, and their roles in virtual community participation. Eur. J. Inf. Syst., 1–28. doi:10.1080/0960085x.2021.2018364

Kim, J., Kang, S., and Lee, K. H. (2020). How social capital impacts the purchase intention of sustainable fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 117, 596–603. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.010

Kim, Y., and Cannella, A. A. (2008). Toward a social capital theory of director selection. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 16 (4), 282–293. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8683.2008.00693.x

Koh, J., Kim, Y.-G., and Kim, Y.-G. (2003). Sense of virtual community: A conceptual framework and empirical validation. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 8 (2), 75–94. doi:10.1080/10864415.2003.11044295

Koranteng, F. N., Wiafe, I., and Kuada, E. (2019). An empirical study of the relationship between social networking sites and students’ engagement in higher education. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 57 (5), 1131–1159. doi:10.1177/0735633118787528

Kreuter, M. W., and Lezin, N. (2002). Social capital theory. Emerg. Theor. Health Promot. Pract. Res. Strategies Improv. Public Health 15, 228.

Ku, Y.-C., Kao, Y.-F., and Qin, M. (2019). The effect of internet celebrity’s endorsement on consumer purchase intention. Int. Conf. Human-Computer Interact., 274–287.

Kumar, S., Rathore, V. S., and Mathur, A. (2022). “A case study on survey plan for digital merchandising system and consumer association management,” in Recent advances in industrial production (Springer), 227–240.

Kwon, J.-H., Jung, S.-H., Choi, H.-J., and Kim, J. (2020). Antecedent factors that affect restaurant brand trust and brand loyalty: Focusing on US and Korean consumers. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 30, 990–1015. doi:10.1108/jpbm-02-2020-2763

Lee, C. T., and Hsieh, S. (2016). The effects of social capital on brand evangelism in online brand fan page: The role of passionate brand love.

Leeraphong, A., and Papasratorn, B. (2018). S-commerce transactions and business models in southeast asia: A case study in Thailand. KnE Soc. Sci. 3, 65–81. doi:10.18502/kss.v3i1.1397

Lei, W., Hui, Z., Xiang, L., Zelin, Z., Xu-Hui, X., and Evans, S. (2021). Optimal remanufacturing service resource allocation for generalized growth of retired mechanical products: Maximizing matching efficiency. IEEE access 9, 89655–89674. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3089896

Leung, W. K. S., Shi, S., and Chow, W. S. (2019). Impacts of user interactions on trust development in C2C social commerce: The central role of reciprocity. Internet Res. 30 (1), 335–356. doi:10.1108/INTR-09-2018-0413

Leung, X. Y., Sun, J., Zhang, H., and Ding, Y. (2021). How the hotel industry attracts Generation Z employees: An application of social capital theory. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 49, 262–269. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.09.021

Li, B., Liang, H., Shi, L., and He, Q. (2022). Complex dynamics of Kopel model with nonsymmetric response between oligopolists. Chaos, Solit. Fractals 156, 111860. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2022.111860

Liao, G.-Y., Huang, T.-L., Cheng, T. C. E., and Teng, C.-I. (2020). Impacts of media richness on network features and community commitment in online games. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald.

Liao, G.-Y., and Teng, C.-I. (2018). How can information systems strengthen virtual communities? Perspective of media richness theory.

Lin, N., Cook, K. S., and Burt, R. S. (2001). Social capital: Theory and research. New Jersey, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Liu, C.-H., and Jiang, J.-F. (2020). Assessing the moderating roles of brand equity, intellectual capital and social capital in Chinese luxury hotels. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 43, 139–148. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.03.003

Lu, Y., Zhao, L., and Wang, B. (2010). From virtual community members to C2C e-commerce buyers: Trust in virtual communities and its effect on consumers’ purchase intention. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 9 (4), 346–360. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2009.07.003

Luo, N., Wang, Y., Zhang, M., Niu, T., and Tu, J. (2020). Integrating community and e-commerce to build a trusted online second-hand platform: Based on the perspective of social capital. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 153, 119913. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119913

Maravic, A. (2013). Through the photo-chromic lens of the beholder: The development of the simple holiday photography to a marketing product. Vienna, Austria: Modul Vienna.

Marcoulides, G. A., Chin, W. W., and Saunders, C. (2009). A critical look at partial least squares modeling. MIS Q. 33 (1), 171–175. doi:10.2307/20650283

Meek, S., Ryan, M., Lambert, C., and Ogilvie, M. (2019). A multidimensional scale for measuring online brand community social capital (OBCSC). J. Bus. Res. 100, 234–244. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.03.036

Mpinganjira, M. (2018). Precursors of trust in virtual health communities: A hierarchical investigation. Inf. Manag. 55 (6), 686–694. doi:10.1016/j.im.2018.02.001

Nalewajek, M., and Macik, R. (2013). The impact of virtual communities on enhancing hedonistic consumer attitudes. Zesz. Nauk. Szko\ly G\lównej Gospodarstwa Wiejskiego w Warszawie. Polityki Europejskie, Finanse i Marketing 10, 59.

Oltra, I., Camarero, C., and San José Cabezudo, R. (2021). Inspire me, please! the effect of calls to action and visual executions on customer inspiration in Instagram communications. International Journal of Advertising, 1–26. doi:10.1080/02650487.2021.2014702

Phua, J., Jin, S. V., and Kim, J. J. (2017). Gratifications of using Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or Snapchat to follow brands: The moderating effect of social comparison, trust, tie strength, and network homophily on brand identification, brand engagement, brand commitment, and membership intention. Telematics and Informatics 34 (1), 412–424. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2016.06.004

Pilar, L., Moulis, P., Pitrová, J., Bouda, P., Gresham, G., Balcarová, T., et al. (2019). Education and Business as a key topics at the Instagram posts in the area of Gamification. ERIES. Journal 12 (1), 26–33. doi:10.7160/eriesj.2019.120103

Priharsari, D., Abedin, B., and Mastio, E. (2020). Value co-creation in firm sponsored online communities: What enables, constrains, and shapes value. Internet Research 30 (3), 763–788. doi:10.1108/intr-05-2019-0205

Quoquab, F., and Mohammad, J. (2022). The salient role of media richness, host-guest relationship, and guest satisfaction in fostering airbnb guests’repurchase intention. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research 23 (2).

Ramle, O., and Kaplan, B. (2019). The power of instagram brand communities: An overview about cosmetic brands on instagram. Florya Chronicles of Political Economy 5 (1), 1–14.

Rasool, A., Shah, F. A., and Tanveer, M. (2021). Relational dynamics between customer engagement, brand experience, and customer loyalty: An empirical investigation. Journal of Internet Commerce 20 (3), 273–292. doi:10.1080/15332861.2021.1889818

Revenue, Instagram, and Usage Statistics, (2022). Business of apps. Available at: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/instagram-statistics/.

Rice, R. E. (1992). Task analyzability, use of new media, and effectiveness: A multi-site exploration of media richness. Organization Science 3 (4), 475–500. doi:10.1287/orsc.3.4.475

Ring, A., Shriber, M., and Horton, R. L. (1980). Some effects of perceived risk on consumer information processing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 8 (3), 255–263. doi:10.1007/bf02721888

Rizmi, M., Lubis, P. H., and Chan, S. (2021). The effect of e-wom on purchase intention through attitude with sovc as a moderating variable on the followers of instagram account “komunitas pecandu buku”.

Rodríguez-López, N. (2021). Understanding value co-creation in virtual communities: The key role of complementarities and trade-offs. Information & Management 58 (5), 103487. doi:10.1016/j.im.2021.103487

Rubio, N., Villaseñor, N., and Yagüe, M. (2020). Value co-creation in third-party managed virtual communities and brand equity. Front. Psychol. 11, 927. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00927

Ruttell, G. (2018). Buyers’ institution-based trust in South African C2C e-commerce: A social capital theory perspective [PhD Thesis]. Burnett St, Pretoria: University of Pretoria.

Sari, D. M. F. P., and Yulianti, N. M. D. R. (2019). Celebrity endorsement, electronic word of Mouth and trust brand on buying habits: Georgios women fashion online shop products in instagram. ijssh. 3 (1), 82–90. doi:10.29332/ijssh.v3n1.261

Schmid, A. A., and Robison, L. J. (1995). Applications of social capital theory. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 27 (1), 59–66. doi:10.1017/s1074070800019593

Shahbaznezhad, H., Dolan, R., and Rashidirad, M. (2021). The role of social media content format and platform in Users’ engagement behavior. Journal of Interactive Marketing 53, 47–65. doi:10.1016/j.intmar.2020.05.001

Shang, R.-A., Chen, Y.-C., and Liao, H.-J. (2006). The value of participation in virtual consumer communities on brand loyalty. Internet Research.

Shao, Z., and Pan, Z. (2019). Building guanxi network in the mobile social platform: A social capital perspective. International Journal of Information Management 44, 109–120. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.10.002

Sholihat, R. P. (2019). Pengaruh perbedaan media richness dan visual complexity konten instagram terhadap kualitas informasi dan citra destinasi pasar semarangan tinjomoyo [PhD Thesis]. Universitas Airlangga.

Simon, S. J., and Peppas, S. C. (2004). An examination of media richness theory in product web site design: An empirical study. United Kingdom: Emerald.

Sundararaj, V., and Rejeesh, M. R. (2021). A detailed behavioral analysis on consumer and customer changing behavior with respect to social networking sites. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 58, 102190. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102190

Swanson, E., Kim, S., Lee, S.-M., Yang, J.-J., and Lee, Y.-K. (2020). The effect of leader competencies on knowledge sharing and job performance: Social capital theory. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 42, 88–96. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.11.004

Tabish, M., Bashir, M. A., Alam, M. M., Long, Z. A., and Rahmat, M. K. (2022). The role of virtual community participation and engagement in building brand trust: Evidence from Pakistan business schools. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 9 (3), 399–409.

Tabish, M., Jalbani, A. A., and Bashir, A. (2020). Pakistan Business Review. Editorial board, 1.The role of virtual, communities in building brand) trust Karachi, Pakistan: Business Review

Tanveer, M., Ahmad, A. R., Mahmood, H., and Haq, I. U. (2021a). Role of ethical marketing in driving consumer brand relationships and brand loyalty: A sustainable marketing approach. Sustainability 13 (12), 6839. doi:10.3390/su13126839

Tanveer, M. (2021). Analytical approach on small and medium Pakistani businesses based on E-commerce ethics with effect on customer repurchase objectives and loyalty. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues 24 (3), 1–20.

Tanveer, M., Khan, N., and Ahmad, A. R. (2021b). “AI support marketing: Understanding the customer journey towards the business development,” in 2021 1st international conference on artificial intelligence and data analytics (CAIDA) (IEEE), 144–150.

Tao, M., and Wei, W. (2019). Enterprise participation and marketing performance in B2B community: A study based on the business friends circle of alibaba. Management Review 31 (6), 123.

Trehan, D., and Sharma, R. (2020). What motivates members to transact on social C2C communities? A theoretical explanation. J. Consum. Mark. 37, 399–411. doi:10.1108/jcm-04-2019-3174

Tsai, J. C.-A., and Hung, S.-Y. (2019). Examination of community identification and interpersonal trust on continuous use intention: Evidence from experienced online community members. Information & Management 56 (4), 552–569. doi:10.1016/j.im.2018.09.014

Tseng, F.-C., Cheng, T. C. E., Yu, P.-L., Huang, T.-L., and Teng, C.-I. (2019). Media richness, social presence and loyalty to mobile instant messaging. Wagon lane bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald publishing.

Valacich, J. S., Mennecke, B. E., Wachter, R. M., and Wheeler, B. C. (1994). Extensions to media richness theory: A test of the task-media fit hypothesis. Proceedings of the 27th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS-27). Part 4 (5), 11–20. doi:10.1109/HICSS.1994.323504

Verduyn, P., Gugushvili, N., Massar, K., Täht, K., and Kross, E. (2020). Social comparison on social networking sites. Current Opinion in Psychology 36, 32–37. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.04.002

Vohra, A., and Bhardwaj, N. (2019). From active participation to engagement in online communities: Analysing the mediating role of trust and commitment. Journal of Marketing Communications 25 (1), 89–114. doi:10.1080/13527266.2017.1393768

Voorveld, H. A., Van Noort, G., Muntinga, D. G., and Bronner, F. (2018). Engagement with social media and social media advertising: The differentiating role of platform type. Journal of Advertising 47 (1), 38–54. doi:10.1080/00913367.2017.1405754

Vrontis, D., El Nemar, S., Ouwaida, A., and Shams, S. M. R. (2018). The impact of social media on international student recruitment: The case of Lebanon. Journal of International Education in Business 11 (1), 79–103. doi:10.1108/JIEB-05-2017-0020

Wang, X., Wang, Y., Lin, X., and Abdullat, A. (2021). The dual concept of consumer value in social media brand community: A trust transfer perspective. International Journal of Information Management 59, 102319. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102319

Webster, J., and Trevino, L. K. (1995). Rational and social theories as complementary explanations of communication media choices: Two policy-capturing studies. Acad. Manage. J. 38 (6), 1544–1572. doi:10.5465/256843

Williams, D. (2006). On and off the’Net: Scales for social capital in an online era. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 11 (2), 593–628. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00029.x

Xiao, H., Zhang, Z., and Zhang, L. (2021). An investigation on information quality, media richness, and social media fatigue during the disruptions of COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Psychol., 1–12. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02253-x

Xie, L., Guan, X., Liu, B., and Huan, T.-C. T. (2021). The antecedents and consequences of the co-creation experience in virtual tourist communities: From the perspective of social capital in virtual space. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 48, 492–499. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.08.006

Yang, K., Kim, H. M., and Tanoff, L. (2020). Signaling trust: Cues from instagram posts. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 43, 100998. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2020.100998

Yao, S., Zheng, X., and Liu, D. (2021). Sense of virtual community, commitment and knowledge contribution: An empirical research based on MI community. Nankai Business Review International 12, 131–154. doi:10.1108/nbri-10-2019-0053

Yen, C., and Chiang, M.-C. (2021). Trust me, if you can: A study on the factors that influence consumers’ purchase intention triggered by chatbots based on brain image evidence and self-reported assessments. Behaviour & Information Technology 40 (11), 1177–1194. doi:10.1080/0144929x.2020.1743362

Zhang, G., Wang, C. L., Liu, J., and Zhou, L. (2022). Why do consumers prefer a hometown geographical indication brand? Exploring the role of consumer identification with the brand and psychological ownership. Int. J. Consum. Stud. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12806

Zhao, J.-D., Huang, J.-S., and Su, S. (2019). The effects of trust on consumers’ continuous purchase intentions in C2C social commerce: A trust transfer perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 50, 42–49. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.04.014

Zhou, L., Jin, F., Wu, B., Wang, X., Lynette Wang, V., and Chen, Z. (2022b). Understanding the role of influencers on live streaming platforms: When tipping makes the difference. Eur. J. Mark. ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). doi:10.1108/EJM-10-2021-0815

Keywords: consumer-to-consumer, brand trust, social capital theory, media richness theory, virtual community

Citation: Tabish M, Yu Z, Thomas G, Rehman SA and Tanveer M (2022) How does consumer-to-consumer community interaction affect brand trust?. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:1002158. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.1002158

Received: 24 July 2022; Accepted: 30 August 2022;

Published: 27 September 2022.

Edited by:

Jean Vasile Andrei, Romanian Academy, RomaniaReviewed by:

Muhammad Adnan Khan, Gachon University, South KoreaHafiz Muhammad Zia-ul-haq, University of Malaysia Terengganu, Malaysia

Copyright © 2022 Tabish, Yu, Thomas, Rehman and Tanveer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Muhammad Tabish, TW9oYW1tYWR0YWJpc2g3NzNAZ21haWwuY29t; Zhang Yu, SG9uZ196aGFuZ0BpbG1hdW5pdmVyc2l0eS5lZHUucGs=; Muhammad Tanveer, Y2Fuc190YW52ZWVyQGhvdG1haWwuY29t

Muhammad Tabish

Muhammad Tabish Zhang Yu

Zhang Yu George Thomas

George Thomas Syed Abdul Rehman3

Syed Abdul Rehman3 Muhammad Tanveer

Muhammad Tanveer