- 1School of Business, Zhejiang University of City College, Hangzhou, China

- 2School of Economics, Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics, Hangzhou, China

As an important policy to promote global energy transition and carbon emission reduction, does the carbon emission trading policy help promote foreign direct investment inflows, thus alleviating the contradiction between environment and economic development? Based on the “OLI paradigm,” by using the data of China’s 30 provinces from 2007 to 2016 and taking China’s pilot implementation carbon emission transaction policy in 2013 as the natural experiment, so as to construct a differences-in-differences model, this study empirically analyzed the impact of carbon emission transaction policies on foreign direct investment and conducted an in-depth analysis and discussion on related heterogeneity. The empirical results show that 1) there is a positive correlation between the carbon emission trading policy and foreign direct investment; 2) the results of heterogeneity analysis show that the effect of carbon emission trading policy on the increase in FDI is more significant in the areas with a stronger environmental regulation, a higher degree of marketization, and low energy consumption. The conclusions of this study enrich the analysis of the effectiveness of government environmental policies from the perspective of both environment and economic development and provide relevant policy enlightenment for developing countries in environmental regulation and attracting foreign direct investment.

Systematic Review Registration: [website], identifier [registration number].

Introduction

The coordinated development of the economy and environment has been a significant issue of common concern all over the world. In the early stage of economic development, in order to eliminate poverty, developing countries often can only adopt loose environment policies, accelerate the development of natural resources, allow pollution emissions, and attract a large influx of “pollution-intensive” industries from developed countries with their low emission costs, so as to obtain the GDP growth (Chenery and Strout, 1966; Grossman and Krueger, 1992; Nourzad, 2008), output effect, and technology spill (Shao and Wang, 2014; Cole et al., 2017) brought by foreign direct investment. However, industrialization which depends on FDI has also enabled developing countries to become a “pollution paradise” for developed countries (Dou and Han, 2019), resulting in serious environmental pollution. With the growth of income, after meeting the basic requirements, people have begun to require institutional implementation of environmental regulations to reduce environmental pollution and ensure a suitable living environment; this eases the contradiction between the environment and the FDI—a problem that economists have long hoped to solve (Zugravu–Soilita, 2017; Hu et al., 2020; Santos and Forte, 2020). On the one hand, the inflow of FDI may bring environmental pollution (Shen and Yu, 2005; Leng et al., 2015); on the other hand, with the increasingly serious environmental pollution, the environmental policies introduced by governments to reduce environmental pollution may lead to a decrease in foreign investment (Rezza, 2015), affecting the economic development of the host country. Around this contradiction, scholars such as William Nordhaus includes climate change into long-term macroeconomic analysis, hoping to develop environmental policies around carbon dioxide as an environmental tool, and regulating all economic entities including FDI, so that it can take into account the environment and its development, to achieve “long-term sustainable economic growth.”

According to the report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), by 2050, the world will be “carbon neutral,” that is, the carbon dioxide emitted directly and indirectly by human activities will be offset by the carbon dioxide absorbed by afforestation, to achieve “net zero emissions” of carbon dioxide. To achieve global “carbon neutrality,” more than 20 countries around the world have joined in the action of emission reduction, began to explore the implementation of relevant environmental policies. As one of the most commonly used environmental policies, the carbon emission trading policy has been successfully practiced in developed countries such as the United States, Germany, and Europe (Teixido et al., 2019). It is based on the Coase theorem that “as long as the poverty right is clear and the transaction cost is zero or small, then the market can finally realize the Pareto optimality of resource allocation.” By clarifying the property rights of carbon dioxide emissions and allowing the market to realize the Pareto optimal allocation of carbon emission rights, through the trading of carbon emission rights, the environmental costs that enterprises may face can be effectively reduced. Therefore, this institutional advantage has a strong attraction to FDI (Li and Lu, 2004; Zhang and Jing, 2012). However, it is difficult to implement the assumption of “zero or very low transaction costs” in the Coase theorem. Due to the cost-effectiveness differences of natural resources and human resources (Dunning and Lundan, 2008), foreign-funded companies may face more transaction costs, and the implementation of carbon emissions transaction policies directly affects the cost-effectiveness of FDI and may directly lead to the withdrawal of FDI. Therefore, this study attempts to answer the following questions. Can carbon emission trading policy promote FDI inflow? Does carbon emission trading policy help ease the contradiction between FDI and the environment? Is the carbon emission trading policy an effective environmental policy to balance the coordinated development of the economy and environment? And under different heterogeneity conditions, how is the effect of carbon emission trading policies on FDI?

Compared with developed countries, China and other developing countries in Asia are still in the process of industrialization and urbanization, which makes the transition from high carbon energy to low carbon economy more difficult. Moreover, developing countries lack experience in dealing with climate change, and they are worried that the national economic development will be affected if all resources are used to deal with climate change. As the largest developing country and the largest foreign capital inflow country in the world, China is at a critical point to solve the conflict between environmental problems and FDI. To alleviate the internal and external pressure of greenhouse gas emissions, China has gradually begun to explore the establishment of a carbon trading market and has proposed to increase its nationally determined contribution to achieve the peak of carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and to achieve the goal of “carbon neutrality” by 2060. In 2011, China proposed to “explore the establishment of carbon emission trading markets,” and agreed to set Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Chongqing, Shenzhen, Hubei, and Guangdong as the pilot areas of carbon emission trading. In 2013, carbon emission trading was officially launched in the pilot areas, hoping to solve the problem of carbon emission through market-oriented means, achieve green and sustainable economic development, and set an example for the global response to climate issues and the realization of “carbon neutrality.” This quasi-natural experiment provides a sample for studying the coordinated development of the environment and economy in developing countries and also provides a reference for other developing countries on how to deal with climate change.

Based on the framework of “OLI paradigm,” by taking a developing country China as the research sample, this article focuses on the discussion of whether the carbon emission trading policy can alleviate the contradiction between the environment and FDI in developing countries, and further builds a differences-in-differences model to empirically analyze the impact of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI and its related heterogeneity. The main conclusions of this article are as follows: 1) Carbon emissions trading effectively promotes the increase in foreign direct investment; 2) the promotion effect of the carbon emission trading policy on foreign direct investment is more significant in areas with stronger environmental regulation and a higher degree of marketization; and 3) there is a significant positive correlation between the carbon emission trading policy and foreign direct investment in low–energy consumption areas, while there is a negative but not significant correlation between the carbon emission trading policy and foreign direct investment in high–energy consumption areas.

The marginal contribution of this article is as follows: First of all, this study systematically evaluates the effectiveness of the carbon emission trading policy from the perspective of economic impact at both macro- and microlevels, explores the correlation between the carbon emission trading policy and FDI, and further verifies whether the carbon emission trading policy can provide a solution to the contradiction between environment and economic development, making up for the existing literature on the coordinated development of the environment and economy, and reflecting the organic combination of environmental governance and economic development. Second, this study retests the “OLI paradigm” combined with the pilot experience of China, and by using the differences-in-differences analysis method, the endogeneity problem that may be caused by bidirectional causality is overcome; the net effect of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI is separated, and the related heterogeneity of its impact is further analyzed. Finally, this study provides a reference for China and other developing countries on how to deal with climate change, coordinate environmental and economic development, and achieve “carbon neutrality” in the world. It also provides policy suggestions for developing countries to introduce, build, and improve carbon trading market and increase FDI inflow, and provides an academic reference value for solving the dilemma of “environmental pollution vs economic development.”

The remaining structure of this article is arranged as follows: The second part summarizes the existing research on the carbon emission trading policy and FDI, as well as the shortcomings, carries out theoretical analysis, and puts forward the research hypothesis of this study. The third part sets up the model and describes the data and constructs the differences-in-differences model. The fourth part reports the empirical results, tests the applicability of the model, and conducts a series of robustness tests to verify the hypothesis. The last part summarizes the whole study and briefly discusses the corresponding policy implications brought by this study.

Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

Literature Review

FDI has great significance for the host country to introduce advanced technology (Cole et al., 2017) and improve energy efficiency (Kim and Adilov, 2012) and economic growth (Nourzad, 2008). Therefore, how to attract more FDI inflows has always been a prominent issue for developing countries. From a theoretical perspective, the research on the influencing factors of FDI originated in 1960. The father of the multinational corporation theory proposed the “monopoly advantage” concept and took FDI as the research object to explain the behavior of international direct investment behavior (Hymer, 1960), which laid a foundation for the subsequent theoretical research on FDI. Subsequently, the theoretical research of FDI developed rapidly and then experienced the evolution process of “monopoly advantage theory,” “product life cycle theory,” “enterprise advantage theory,” “internalization advantage theory,” and “marginal industry investment theory,” but these theories have certain shortcomings which make these theories have weak explanations for FDI flows; for example, the analysis of “product life cycle theory” and “marginal industry investment theory” was limited to specific national background and the “internalization advantage theory” ignored the changes of international economic environment (Fang J Y, 2003). After that, Dunning integrated the advantages of the previous FDI theory, and by combining with traditional trade theories and internalization theories, he introduced the ownership advantage (O), internalization advantage (I), and location advantage (L); put forward the “OLI paradigm”; and gave a comprehensive and systematical explanation of it (Dunning, 1981). The “OLI paradigm” strengthens the explanatory power of the FDI theory and expands the scope of application of the FDI theory. Since then, the theoretical research on FDI has basically followed the “OLI paradigm,” which plays an important role in the current analysis of FDI inflows. In recent years, under the background of the in-depth development of economic globalization, some scholars have put forward new theories of international direct investment, such as the “theory of investment induced factor combination,” “national competitive advantage theory,” and “global strategic theory of multinational corporation,” but all of them have limitations and lack in practicality, and cannot well explain the flow of FDI (Fang J Y, 2003).

From the empirical perspective, among the existing research studies on the FDI influencing factors, the first kind of research tested the “OLI paradigm” based on the theoretical basis and the empirical data of the host country. For example, Mao and Chen (2001) found that China’s low labor cost and huge market potential attracted FDI which has advantages in technology and management experience. Yeung (2001) proposed a new “dynamic symbiosis” model of FDI by conducting an in-depth investigation into the causes of FDI in Dongguan, one of the most successful foreign investment–driven regions in China, and related socioeconomic impacts. In addition, some scholars, based on the “OLI paradigm” and institutional economics, empirically tested the significant impact of institutional conditions (Han et al., 2016; Kang, 2018) and the government’s market-oriented policies (Saleh et al., 2017) on FDI. Another type of research started from the characteristic facts and explored the main factors affecting FDI flow, among which the following three factors are the most recognized: policy system, marketization degree, and environmental regulation intensity. In terms of policy systems, FDI is affected by the improvement degree of the economic system (Zeng, 2016) and the national investment guiding policy (Wang, 2021) in the host country. And in terms of marketization, the level of economic development (Tang et al., 2018), the degree of trade openness (Wang, 2021), and human capital (Tang et al., 2018) will affect the location selection of FDI. Scholars have different opinions on the intensity of environmental regulation, and some scholars believe that low environmental standards (Zhu et al., 2011) and lax environmental regulations (Guo and Han, 2008) are conducive to attracting foreign capital inflows; however, some other scholars believe that the strict environmental regulations have brought cost advantages (Dijkstra et al., 2011), thus promoting FDI inflow.

However, while the FDI has brought economic contributions to developing countries, it may also increase environmental pollution in developing countries (Ashraf et al., 2020). To alleviate the contradiction between environment and economic growth, China and other developing countries began to introduce environmental policies. Among them, the most representative and characteristic environmental policy is the carbon emission trading policy. The environmental policy represented by the carbon emission trading system can be traced back to the signing of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, which proposed three types of carbon emission trading mechanisms: international emissions trading mechanism (ET), joint implementation mechanism (JI), and clean production mechanism (CDM). Since the signing of the Kyoto Protocol, governments have begun to consider the emission reduction and limitation of greenhouse gases (Brack et al., 1999). In 2003, Directive 2003/87EC was adopted by the European Parliament and the Council, which established a greenhouse gas emission quota and trading system for the EU since 2005, the carbon emission trading policy was formally formed. Since the emergence of carbon emission trading policy, the research on the effectiveness of the carbon emission trading policy has been constantly emerging. Among them, as for the contribution of the carbon emission trading policy to environmental governance, most scholars found that whether the developed countries represented by the EU countries (Nordhaus, 2007; Stern, 2007) or the developing countries represented by China (Xiu et al., 2015; Gao et al., 2020; Xuan et al., 2020), the carbon emission trading policy effectively reduces carbon dioxide emissions, improves carbon emission allocation and efficiency (Chang, 2012) and regional carbon equalization (Zhang et al., 2021), and contributes to the realization of “carbon peak” in advance (Wu and Zhu, 2021).

In addition to the assessment of the emission reduction effects of carbon emissions trading policies, some studies extend the impact of carbon emissions trading policies beyond the environment. For example, in terms of corporate innovation, Chen et al. (2021) and Zhang Y J et al. (2020) discussed whether the carbon emission trading policy promotes corporate innovation and reached the opposite conclusion; the effect of the carbon emissions trading policy on enterprises’ total factor productivity is also concerned. Scholars have found that the total factor productivity of enterprises in pilot areas of carbon emission trading policy is significantly higher than that in non-pilot areas (Hu and Ding, 2020; Xiao et al., 2021). In terms of economic growth, the carbon emission trading policy not only promotes long-term sustainable economic growth in pilot regions (Zhang W et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2020) but also is conducive to reducing the urban–rural income gap (Yu et al., 2021), and China’s carbon emission trading policy mainly based on the CDM is conducive to absorbing investment from developed countries (Liu and Dai, 2004). Among them, the studies of Lee (2013), Gong et al. (2019), and Sun and Zhou (2020) are most similar to this study. Lee (2013) verified the promotion effect of FDI inflow on the economic growth of G20 countries (host country) and the negative correlation between the economic growth of G20 countries (host country) and carbon emissions. Gong et al. (2019), Sun and Zhou (2020) used the differences-in-differences method to verify the positive contribution of China’s low-carbon pilot policy on the quantity (Gong et al., 2019) and quality (Sun and Zhou, 2020) of FDI, respectively.

It can be seen from the research studies that the combination of the “OLI paradigm” and practical empirical data in the existing literature is slightly insufficient and often ignores the impact of environmental policies on the FDI’s location choice. According to the research on carbon emission trading policy, most of the studies are still focusing on the effectiveness of policy such as emission reduction effects. As a means of environmental regulation, the influence of carbon emission trading policy not only stays in the field of environment but also extends to enterprises and even the macroeconomic field outside the environment. Therefore, the side effects of environmental policies should also be considered. Based on the data of developing countries in China, this article conducts an in-depth discussion on the investment decision-making behavior of the micro-subject of FDI (multinational enterprises) from the three aspects of ownership advantage, internalization advantage, and location advantage of the “OLI paradigm” and evaluates the effectiveness of the carbon emission trading policy from the macro- and microlevel more comprehensively. Combined with the time background, it is not only a retest of the “OLI paradigm” but also an extension of carbon emissions trading policy–related research to the economic field from the foreign direct investment perspectives. Besides, based on the differences-in-differences method, this study effectively separates the net effect of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI and further measures the impacts of different institutional environments (marketization degree and environmental regulation intensity) and carbon emission trading policies in different energy-consuming regions (different coal-consuming regions) on FDI. It also provides some reference for China to further improve carbon emission trading policies and for other developing countries to promote carbon emission trading policies to achieve the win–win situation of carbon reduction and economic growth.

Research Hypothesis

The “OLI paradigm” comprehensively analyzes the motivation and determinants of enterprises’ overseas direct investment from the three aspects of ownership advantage, location advantage, and internal advantage and has a relatively complete explanation for direct investment (Fang, 2003; Guo et al., 2006), which can be applied to examine FDI and international production in a specific context (Dunning and Lundan, 2008), to better explain FDI flows. It is the best starting point for establishing the FDI theory centered on the host country (Cui, 2001). Therefore, this study draws on the practice of Cui (2001) et al. and takes the “OLI paradigm” as the starting point to discuss how the carbon emission trading policy affects the micro-subject behavior of FDI activities. Different from the traditional theory of international capital flow, the “OLI paradigm” emphasizes that multinational enterprises can reduce transaction costs and gain greater benefits through international direct investment. Specifically, direct investment by multinational companies will inevitably increase costs and risks; however, according to the “OLI paradigm,” the main subject of FDI, that is, the foreign investment of multinational companies, will be affected by ownership advantages, internalization advantages, and location advantages. These advantages will help multinational companies minimize the transaction costs and technology spillover risks (Nielsen et al., 2017), so that multinational companies become willing to make foreign investment. Therefore, whether the three advantages are available and how strong the degree of their effects is jointly determine whether and how enterprises invest abroad (Yan, 1994). In essence, the carbon emission trading policy affects the market competitiveness, price mechanism, and resource allocation of enterprises through factors such as carbon price and carbon quota, thus affecting the decision-making of multinational corporations. Therefore, the study on the impact of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI focuses on the analysis of the impact of the carbon emission trading policy on the ownership advantages, internalization advantages, and location advantages of multinational corporations.

The advantage of enterprise ownership refers to the advantage of enterprise compared with foreign enterprise in economic scale, market competitiveness, factor resource endowment, and so on. The ownership advantage of multinational enterprises comes from certain intangible assets such as patents, trademarks, and management skills. These factors make transnational enterprises have a higher technical level or price level than other enterprises, thus forming a competitive advantage (Cruz et al., 2020). As the institution is one of the important factors affecting the decision of FDI (Sauvant and Mallampally, 2015; Yulek and Gur, 2017), this ownership advantage is based on the diversity of the host country’s institution (Dunning and Fortanier, 2007) and has a significant impact on the entry choice of overseas investment (Wu, 2011). As a clear institution, the carbon emission trading policy can give full play to the ownership advantages of multinational enterprises because multinational enterprises usually have relatively advanced emission reduction technologies, under the carbon emission trading policy; multinational enterprises with advanced emission reduction technologies can obtain additional benefits by selling carbon emission rights, which brings a significant income effect to multinational enterprises, thus improving the comparative advantage of transnational enterprises over the host country. Therefore, the carbon emission trading policy will make the ownership advantage of multinational enterprises more prominent and make transnational investment more attractive. Based on this, we propose the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The carbon emission trading policy will increase FDI inflows.

The motivation of internalization of multinational companies is to avoid incomplete resource allocation mechanisms of the external market (Yan, 1994), while external mechanisms mainly include public regulation and price mechanism, which may be affected by transaction costs, market information, and government regulation. On the one hand, in areas with more stringent public regulation, multinational enterprises are more inclined to increase investment and avoid the influence of government regulation through internalization, so as to maximize profits (Wu, 2011). Therefore, the impact of carbon emission trading policies on the entry decisions of foreign enterprises may be different in regions with different environmental regulation intensities. Compared with regions with loose environmental regulations, regions with strict environmental regulations may be subjected to greater supervision and restrictions and face more transaction costs, such as rent-seeking. Through the establishment of new enterprises or expansion of investment, carbon emission trading between different enterprises will be internalized into trading between different subsidiaries in the same group, and it may be a more profitable choice for multinationals. On the other hand, strict environmental policies mean stronger contractual execution. Market information can partially eliminate the distortion of the price mechanism and reduce market information, which not only brings cost advantage for efficient foreign-funded technology companies (Dijkstra et al., 2011) but also helps to improve the FDI structure (Xu et al., 2021) and its environmental performance (Li and Ramanathan, 2020), thus producing significant attractiveness to FDI (Contractor et al., 2020). Based on the aforementioned analysis, we propose the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: The stronger the environmental regulation is, the more significant the effect of carbon emission trading policy on promoting the increase of FDI is.

According to the Coase theorem, the premise of the carbon emission trading policy is that “the transaction cost is zero or very small,” which means that the free transactions of carbon emission trading policy will be restricted by a series of marketization factors such as regional economic development level (Das, 2013), degree of openness (Kyrkilis and Pantelidis, 2003), and labor cost. Specifically, regions with a higher degree of marketization often have higher economic development levels, human capital levels, good competition mechanism, higher efficiency of resource allocation, and stronger flexibility of the labor market (Rong et al., 2020), which can effectively avoid market incompleteness caused by the price mechanism, and industry supply and demand relationship can timely reflect and guide the transfer and adjustment of capital between industries (Wurgler, 2001). In this case, the ownership advantage of multinational enterprises will be improved faster in the implementation of the carbon emission trading policy, thus helping to attract foreign capital inflows. In other words, in regions with a higher degree of marketization, the carbon emission trading policy will play a more efficient role and further improve the ownership advantage of multinational enterprises, which will have greater attractions. Based on the preliminary analysis, this study believes that carbon emission trading policy strengthens the ownership advantage of FDI in regions with a higher degree of marketization. Based on this, we propose the third hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3: The higher the degree of marketization, the more significant is the promoting effect of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI.

Location advantage is one of the main factors that determine whether a multinational enterprise invests or not. Tang et al. (2018) consider that there are obvious differences in environmental regulations and FDI in different regions, that is, the differences in the implementation of environmental policies in different regions may affect the ownership advantages brought by emission reduction technologies of multinational enterprises. As a big energy-consuming country, China’s main energy structure is dominated by coal, and coal consumption is the main source of carbon emissions. The main transaction object of the carbon emission trading policy is carbon emission rights, but there are differences in carbon emission, energy consumption, carbon emission quota, and coverage in different regions. Therefore, coal consumption endowment may be the biggest locational factor affecting FDI under the carbon emission trading policy. On the one hand, due to the high dependence on coal for regional economic development, environmental policies in regions with high energy consumption and a low emission reduction level may be inclined to be loose, with smaller quotas and coverage, and lower emission reduction targets than those regions with low coal consumption. As local enterprises only need a small amount of capital and technology investment to meet the emission reduction standards, the carbon emission trading policy cannot bring competitive advantages to foreign investment in these regions. Thus, the ownership advantages of multinational enterprises will be weakened compared with local enterprises, and the attractiveness of these regions to FDI will also be weakened. On the other hand, in regions with low energy consumption and high emission reduction levels, the demand for coal is low and the regional economic development is not strongly dependent on coal, so environmental policies may be relatively strict, with higher emission reduction targets, higher quotas, and wider coverage. Therefore, to meet the emission reduction standards, local enterprises need a large amount of capital and technology input, and through the carbon market trading, the cost-saving effect can be brought to the participating enterprises (Cui et al., 2013), thus greatly reducing the emission reduction cost of enterprises. Meanwhile, multinational enterprises can participate in carbon emission trading by entering these areas, and with efficient reduction technology advantages, the attractiveness of these regions to FDI will be enhanced. In conclusion, this article concludes that the carbon emission trading policy weakens the FDI’s location advantages of regions with large energy consumption. Based on this, we propose the fourth hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4: In areas with low energy consumption, the effect of carbon emission trading policy on FDI increase is more significant.

Empirical Design

Model Setting

Policy evaluation usually uses four methods: the instrumental variable method, differences-in-differences method, regression discontinuity method, and propensity matching score method. The instrumental variable method cannot be used alone, and the regression discontinuity method and propensity matching score method have strict requirements on sample size, while the differences-in-differences method only needs to meet the premise of parallel trend assumption, with extensive applicability. In addition, the differences-in-differences method not only controls the non-observing individual heterogeneity between samples but also controls the influence of unobservable overall factors changing with time, which solves the endogenous problem of policy as an explanatory variable. Therefore, by referring to the research of Shi and Li (2020), this study constructs a differences-in-differences (DID) model to control the unobservable individual differences among samples and other factors that change over time, to eliminate the impact of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI. The model is as given follows:

In model (1), i and t represent the province and year, respectively;

Variable Definition and Data Description

This article takes the panel data of China’s 30 provinces (excluding Tibet, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan) from 2007 to 2016 as the sample, and sets 2013–2016 as the implementation and subsequent years of carbon emission trading policy, and 2007–2012 as the period before the policy was introduced. The data of this article are mainly from the China Statistical Yearbook, Wind database, CSMAR, and Chinese Economic Information Network.

The main explanatory variable in this article is the interaction item (

Referring to the research of Deng and Xu (2013), Tang et al. (2018) and Lim (2008), the control variables mainly include 1) the education level (lnedu), measured by the number of people with a college degree or above in the total population of each province and processed by logarithm, represents the level of human capital stock in each province; 2) the proportion of state-owned enterprises (lnSOB), which is obtained by dividing the number of state-owned enterprises in each province by the total number of enterprises in each province and processed by logarithm, represents the ownership structure of each province; 3) economic scale (lnescale), calculated by dividing the real GDP of each province by the total population of each province and processed by logarithm, represents the economic scale of each province; 4) infrastructure level (lntrans), expressed by the freight volume of each province and processed by logarithm, represents the infrastructure situation of each province; and 5) number of invention patents (lnpatent), measured by the number of invention patent applications accepted by each province and processed by logarithm, represents the R&D and innovation ability of each province. Other variables mainly include 1) environmental regulation intensity (lnEI), which is obtained from the ratio of investment completed in industrial pollution treatment to regional GDP and processed by logarithm, represents the intensity of environmental regulation in each province; and 2) marketization index (lnmar), from the marketization index1 and processed by logarithm, represents the marketization degree of each province.

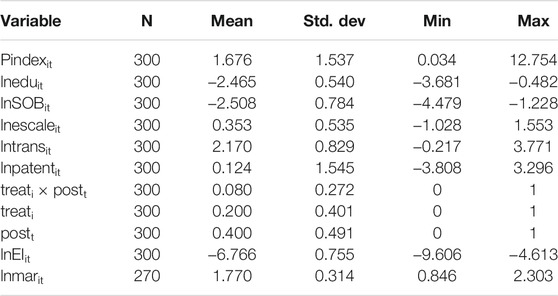

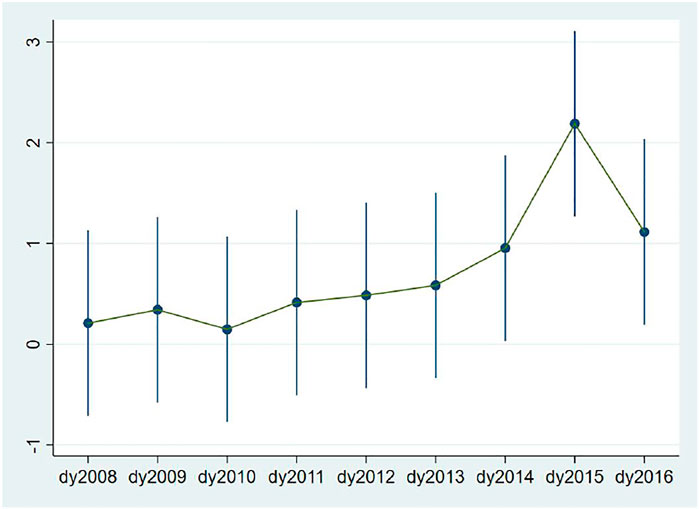

The descriptive statistics of the main variables are shown in Table 1:

As can be seen from Table 1, the mean value of the FDI performance index (Pindex) is 1.676, the SD is 1.537, the minimum value is 0.034, and the maximum value is 12.754; it indicates that there are great differences in FDI among provinces during the sample period, which provides an objective basis and entry point for the subsequent research on the impact of the carbon emission trading policy. The mean values of the province grouping variable (

To further examine the mean difference of the FDI performance index (Pindex) between the treatment group and the control group before and after the implementation of carbon emission trading policy, the mean of the FDI performance index (Pindex) before and after the implementation of the policy in the total sample, treatment sample, and control sample is compared, the sample comparison results are shown in Table 2:

It can be seen from Table 2 the sample distribution of the FDI performance index (Pindex) of the treatment group and the control group from 2007 to 2016. From the perspective of the FDI difference between the treatment group and the control group, before 2011, the FDI difference between the treatment group and the control group was basically in the range of 1.000–1.400, that is to say, before the implementation of the carbon emission trading policy, the FDI difference between pilot areas and non-pilot areas was relatively stable. In 2011, the FDI difference between the treatment group and the control group increased slightly possibly because the carbon emission trading pilot was approved, which made the FDI difference between the pilot and non-pilot areas rise for the first time. Compared with the year before 2013, after the carbon emission trading policy was introduced in 2013, the FDI difference between the treatment group and the control group further expanded and exceeded 3.000 in 2015, it can be concluded that the implementation of the carbon emission trading policy has a considerable different impact on FDI in pilot areas and non-pilot areas. In 2016, the FDI difference between the treatment group and the control group decreased, which may be attributed to a series of preferential policies for cleaning up investment promotion and standardizing taxation policies issued by China at the end of 2014 which suppressed the inflow of FDI, and FDI in all regions decreased compared with the previous year. Comparing the changes of FDI before and after the implementation of the policy in the control group and the treatment group, we found that the increase in FDI inflows in the treatment group is more significant than that in the control group after 2013, which indicates that the implementation of the carbon emission trading policy has effectively promoted the increase in FDI inflows in the pilot areas.

Empirical Test and Result Analysis

Parallel Trend Test

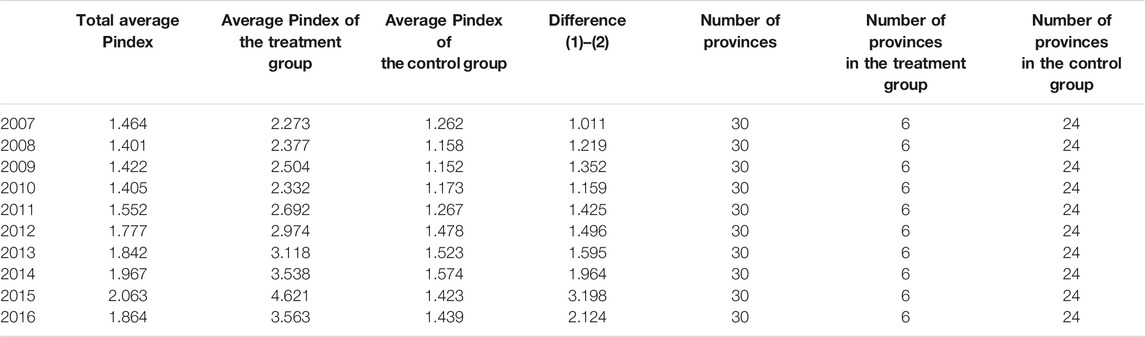

The premise of using the differences-in-differences method is that the treatment group and the control group meet the assumption of parallel trend, that is, before the implementation of the carbon emission trading policy, FDI in pilot and non-pilot provinces should maintain a relatively stable changing trend. Therefore, before the empirical test, we constructed the time trend chart of the mean value of the FDI performance index (Pindex) of the pilot and non-pilot provinces during 2007–2016 to analyze whether the changing trend of the pilot and non-pilot provinces is consistent. The time trend chart is shown in Figure 1:

In Figure 1, the solid line represents the pilot provinces and the dotted line represents the non-pilot provinces; it can be seen that before 2013, the FDI performance index (Pindex) in pilot provinces and non-pilot provinces has roughly the same changing trend. In 2011, FDI in the pilot has risen slightly, but the overall trend of FDI in pilot provinces and non-pilot provinces remains consistent. After the policy impact in 2013, compared with non-pilot areas, FDI in pilot areas shows a significant increase, while FDI in non-pilot provinces does not change significantly, the possible reason is that the state council issued a series of preferential policies for FDI to standardize them in 2014, which reduces FDI. Therefore, from the time trend chart, we conclude that before the implementation of the policy, the pilot provinces and non-pilot provinces maintain roughly the same trend of change.

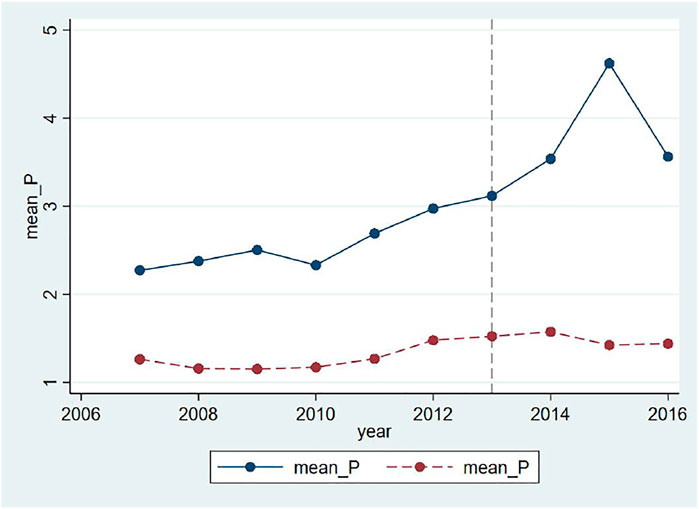

To further examine whether the parallel trend test has been passed in the statistical sense, this article takes 2013 as the benchmark year for the pilot implementation of carbon emission trading policy, winsorizes the panel data by year, and regresses the dependent variables from 2008 to 2016, to show the economic effects of the policy in different years. The regression results are shown in Figure 2:

As shown in Figure 2, before the implementation of the pilot carbon emission trading policy, the overall fluctuation range of the regression coefficient is small, and all fluctuate around 0, which indicates that there is no significant difference between pilot areas and non-pilot areas before 2013, satisfying the hypothesis of parallel trend. After the pilot implementation of the carbon emission trading policy in 2013, due to the time lag of the carbon emission trading policy, the coefficient shows an obvious upward trend in 2014, gradually deviates from 0, and reaches its peak in 2015. The decline in 2015–2016 may be attributed to the Decision on Deepening the Reform of Budget Management System issued by the state council at the end of 2014, which regulated preferential policies such as cleaning up investment attraction preferences and standardizing taxation, thus leading to a significant downward trend of FDI. Overall, before the implementation of the policy, the changing trends of the pilot provinces and non-pilot provinces are roughly the same, and after the implementation of the policy, the FDI in the pilot provinces and non-pilot provinces is significantly different, thus passing the parallel trend test. Therefore, the premise of using the differences-in-differences method is satisfied.

Regression Results

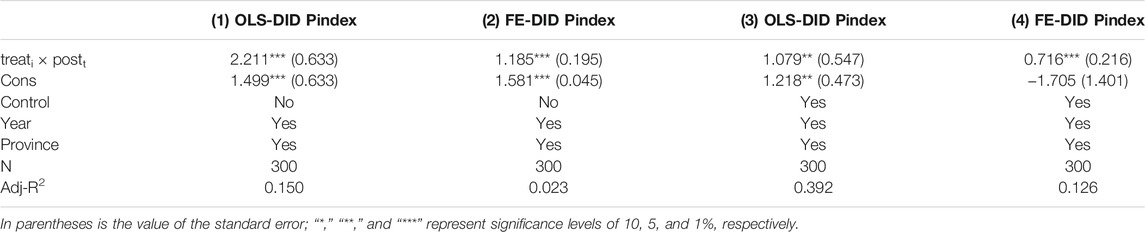

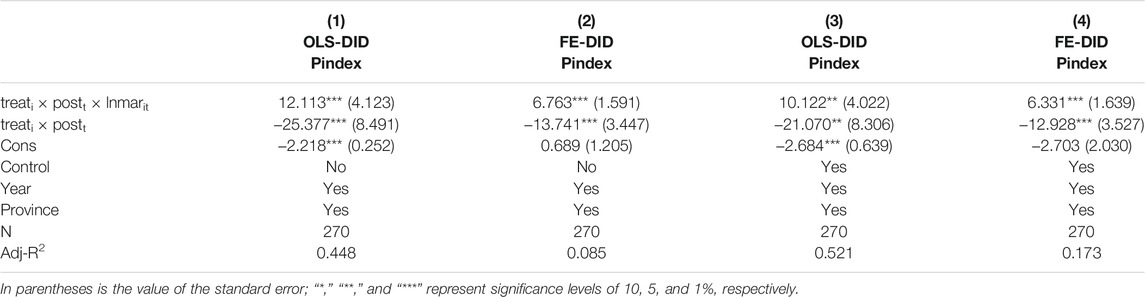

To test hypothesis 1, that is, whether the carbon emission trading policy promotes FDI inflows, and to comprehensively estimate its effect, we use two methods of OLS–DID and FE–DID to analyze the regression of model (1). In this regression, we mainly focus on the coefficient value of treati × postt and its sign direction, the coefficient valuation of treati × postt reflects the policy effect under the differences-in-differences; and its sign direction reflects whether the policy promotes or inhibits the FDI. The regression results are shown in Table 3:

Table 3(1)–(2) shows that after controlling the time fixed effect and province fixed effect, the coefficient of treati × postt is significantly positive at 1% level, indicating that there is a significant difference in FDI between the treatment group and the control group. To solve the endogeneity problem caused by other influencing factors, we added control variables such as education level (lnedu), the proportion of state-owned enterprises (lnSOB), and economic scale (lnescale) into columns (3)–(4). The regression result shows that the coefficient of treati × postt is still significant, and it also indicates that the carbon emission trading policy effectively promotes the increase in the FDI. From the above regression result, the coefficient results of treati × postt can be seen that after implementing the carbon emission trading policy, the FDI in the carbon emission trading pilot provinces is about 0.7–2.2 higher than that in the non-pilot provinces, and it is significant at 1 and 5%, respectively. From the perspective of mechanism, the carbon emission trading policy strengthens the advantages of multinational enterprises, thus promoting the inflow of FDI in the pilot areas. Therefore, the implementation of the carbon emission trading policy improves the inflow of FDI in the pilot provinces, and hypothesis 1 is verified.

Robustness Test

Placebo Test

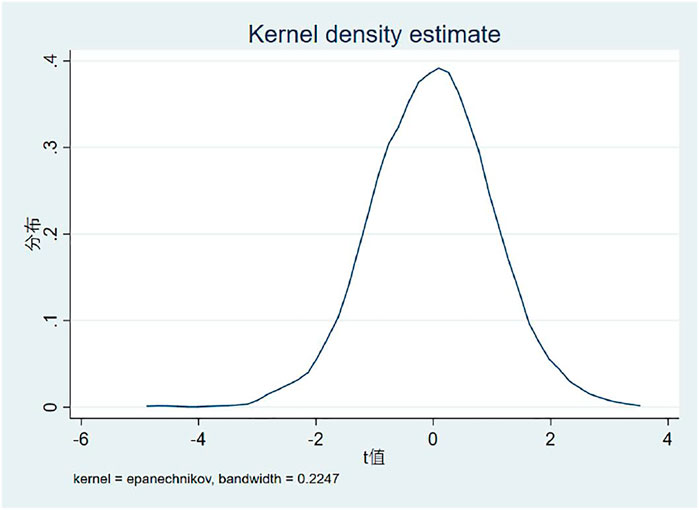

The placebo test mainly includes two methods: fictitious treatment group and control group, and fictitious policy impact point. Based on the research of Shi and Li (2020), we make a placebo test through fictional treatment groups. Specifically, this article conducted 1,000 samples in 30 provinces, randomly selected virtual treatment group and control group, and regression. The kernel density distribution of the dependent variable (Pindex) is shown in Figure 3:

If the regression results of the randomly generated estimator of the fictitious treatment group are still significant, it indicates that the original estimation results are biased; otherwise, the influence of other unknown factors is excluded. As can be seen from Figure 3, the sampling estimation results show that the absolute value of the vast majority of T values is within 2, and most of the p values are above 0.1, indicating that the result is not significant in 1,000 random sampling, thus excluding the influence of other policies or random factors on the research results in the same period. Therefore, the conclusion obtained from this study passed the placebo test, and the effect of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI is not related to other unknown factors.

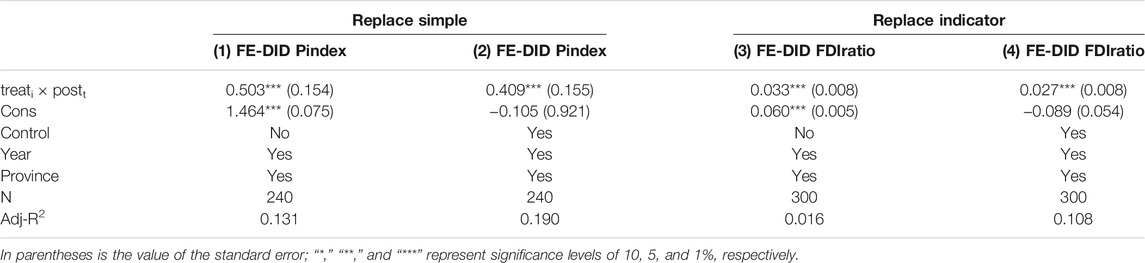

Replace Sample

To further ensure the reliability of the research conclusions, we use the method of changing samples and take the data from 2007 to 2016 as a subsample for robustness test. To promote fair competition in the market and maintain the normal market order, the state council issued the Decision on Deepening the Reform of Budget Management System in December 2014, and No. 62 Document regulates preferential policies such as cleaning up preferential policies for investment attraction and standardizing taxation. We believe that the introduction of this policy may affect the investment attraction of various regions, thus affecting FDI. To accurately identify the net effect of the implementation of this policy, it is necessary to eliminate the policy interference that may have an impact on FDI. Considering the policy was introduced at the end of 2014, we exclude the data from 2015 to 2016 to form a subsample and conduct FE–DID regression with the model (1), and the regression results are shown in Table 4(1)–(2). As can be seen from columns (1)–(2) in Table 4, although the coefficient of treati × postt has decreased, the coefficient of treati × postt is still significant at 1% level, and the sign direction has not changed, indicating that the conclusions from this study are still significant after the replacement of samples.

Replace Indicator

To further verify the robustness of the empirical results in this study, we consider replacing the dependent variable indicator and also perform FE–DID regression with the model (1). Specifically, the FDI ratio of regional FDI inflows to national FDI inflows is the dependent variable to measure the FDI in each province. The regression results are shown in Table 4(3)–(4); column (3) is the FE–DID regression without adding control variables, and column (4) is the FE–DID regression with adding relevant control variables. It can be seen that after changing the index of the dependent variable, the regression result is still significantly positive at the 1% level, which is consistent with the empirical conclusion, that is, the carbon emission trading policy significantly promotes the increase in FDI, thus passing the robustness test.

Heterogeneity Analysis

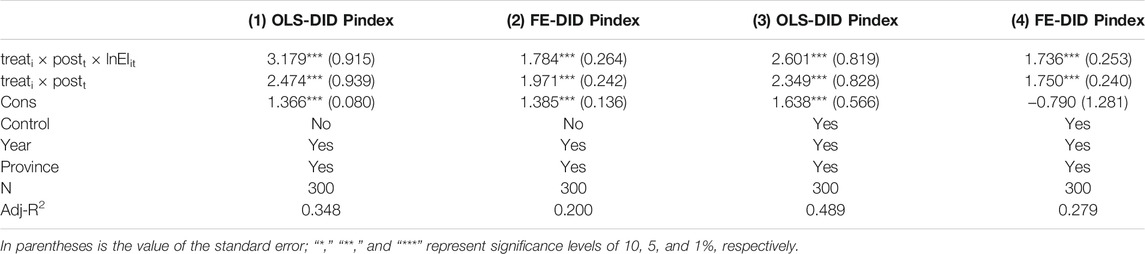

It is confirmed that the carbon emission trading policy can significantly improve FDI. Then what factors will affect the promotion effect of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI? We propose hypothesis H2 which argues that the stronger the environmental regulation is, the more obvious internalization advantages for multinational enterprises are, so that the carbon emission trading policy in these regions may have a greater effect on FDI. To verify the different promoting effects of carbon emission trading policy on FDI under different environmental regulation intensities, we add environmental regulation intensity (lnEIit) into the model (1), as follows:

In model (3),

As shown in Table 5, columns (1)–(2) are regression results of OLS–DID and FE–DID without adding control variables, and columns (3)–(4) are regression results of OLS–DID and FE–DID after adding control variables. It can be seen that the coefficients

According to the aforementioned hypothesis analysis, the higher the degree of marketization, the stronger the ownership advantage of multinational enterprises will be. Therefore, the effects of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI in regions with different degrees of marketization are different. To further examine the impact of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI affected by the degree of marketization, we consider choosing the marketization index as a proxy variable to measure the degree of marketization and add the marketization index (lnmarit) into the model (1) and set model (4) as follows:

In model (4),

From the regression results in Table 6, the coefficient is significantly positive at the level of 1 and 5%, respectively, which indicates that the effect of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI is significantly affected by marketization. From the perspective of mechanism, regions with a higher degree of marketization have good competition mechanisms and higher resource allocation efficiency. Under the carbon emission trading policy, the ownership advantages of multinational enterprises can be brought into full play, thus making the host country more attractive to FDI. In summary, the higher the degree of marketization, the more significant the promotion effect of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI is, which verifies hypothesis 3.

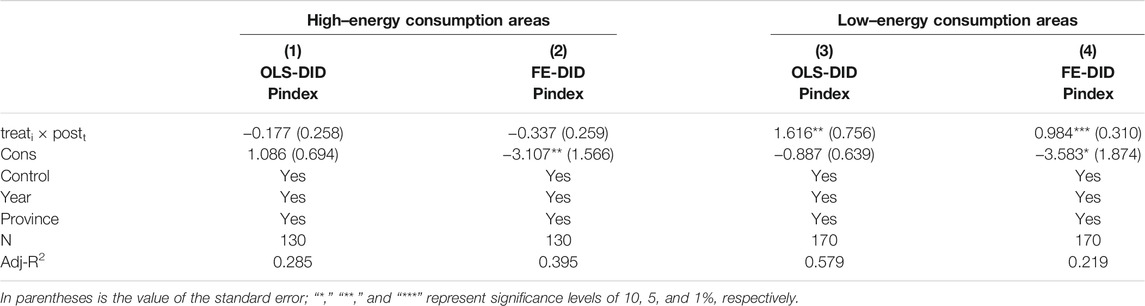

We have verified the different effects of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI under different environmental regulation intensity and marketization degrees. In addition, from the perspective of horizontal differences, this article further analyzes the heterogeneity of regions with different energy consumption and takes coal consumption as the main energy structure to represent energy consumption. Regions with high coal consumption represent high–energy consumption areas, otherwise low–energy consumption areas. According to the average annual consumption of coal in each province, 13 provinces such as Hebei, Shanxi, and Inner Mongolia, selected from 30 provinces in China, are as major coal consumption provinces, and the other 17 provinces are non-major coal consumption provinces.2 To be specific, we regress the major coal-consuming provinces and non-major coal-consuming provinces to test the impact of carbon emission trading policy on FDI in different energy consumption regions, respectively. The regression results are shown in Table 7:

As shown in Table 7, columns (1)–(2) are the regression results of the OLS–DID and FE–DID of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI in high–energy consumption areas. The regression results show that the carbon emission trading policy reduces the inflow of foreign capital in high–energy consumption areas, but the regression results are not significant. The possible reason is that the excessive carbon emissions, low carbon emissions quota, and small carbon emission rights allocation coverage in high–energy consumption areas may weaken the technological advantages of multinational enterprises compared with local enterprises, which makes the implementation of the carbon emission trading policy in high–energy consumption areas have no significant impact on FDI, so the implementation of the carbon emission trading policy cannot promote the increase in foreign capital inflows in high–energy consumption areas. Columns (3)–(4) are the regression results of OLS–DID and FE–DID of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI in low–energy consumption areas. The regression results show that the impact of the carbon emission trading policy on the increase in FDI in low–energy consumption areas is significantly positive at the level of 5 and 1%, respectively. In other words, the implementation of the carbon emission trading policy has effectively promoted the inflow of FDI in low–energy consumption areas. The possible reason is that there are sufficient carbon quotas in low–energy consumption areas, and multinational enterprises with advanced emission reduction technology can obtain additional income through quota trading, thus increasing the inflow of FDI into low–energy consumption areas, which supports hypothesis 4.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

This study takes the most representative developing country China as an example, and based on the panel data of 30 provinces in China from 2007 to 2016, from a new perspective of FDI, this study examines the impact of China’s pilot implementation of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI inflows, attempts to discuss the relevant heterogeneity from the perspectives of different environmental regulation intensity, marketization degree, and energy consumption, and further provides an empirical basis for developing countries to optimize the carbon emission trading policy and introduce FDI. The conclusions of this study are summarized as follows: First, the carbon emission trading policy reduces the transaction cost of multinational companies and gives full play to the ownership advantage of multinational companies by clear property rights trading, thus effectively promoting the increase in FDI inflows; second, under the impact of the carbon emission trading policy and the different heterogeneity factors, the effects of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI are different. The ownership advantages, internalization advantages, and location advantages of foreign investment can be brought into full play in areas with stronger environmental regulations, a higher degree of marketization and low energy consumption, these areas are more attractive to multinational companies; therefore, the positive contribution of emissions trading policies to FDI is more significant in these regions. The carbon emission trading policy enables enterprises to participate in carbon trading to freely trade carbon emission rights based on their interests and forces enterprises to innovate green emission reduction technologies to obtain more quotas and make profits by selling them, thus realizing reasonable and effective allocation of resources and maximizing profits. Based on the existing studies and the research conclusions of this article, the pilot implementation of the carbon emission trading policy in China is conducive not only to emission reduction but also to the increase in FDI inflows, which helps promote the coordinated development of the environment and economy.

The results of this study may have the following policy implications and suggestions: 1) improve the carbon emission trading policy and expand the coverage of carbon trading markets. As an environmental policy, the carbon emission trading policy can promote the increase in FDI, ease the contradiction between environmental and FDI, and then coordinate environmental protection and economic development, so the policy can be adopted by developing countries to gradually achieve the goal of “carbon neutrality” in the process of economic development. Developing countries and regions that have not participated in carbon emission trading should be encouraged to gradually participate in carbon emission trading and draw lessons from the implementation of China’s carbon trading policy; for countries or regions that have already implemented carbon emission trading policies, the coverage of carbon emissions should be expanded; the carbon emission trading mechanism should be further improved, and incentive-compatible mechanisms should be established; the inflow of foreign capital with advanced emission reduction technology should be encouraged by subsidies, etc.; 2) moderately strengthen environmental regulation and accelerate the process of marketization. First of all, in regions with higher environmental regulation intensity, the promotion effect of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI is more significant, so the intensity of environmental regulation should be moderately strengthened. To further introduce high-quality foreign investment and offset the negative impact of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI, the strengthening of ownership advantages, internalization advantages, and location advantages of multinational enterprises should be focused on; the corresponding laws and regulations for carbon trading should be improved; and the supervision of relevant departments and law enforcement should be implemented, etc., so as to attract FDI from the source. Second, in regions with a higher degree of marketization, the promotion effect of carbon emission trading policy on FDI is more significant, so the marketization process should be accelerated. The carbon emission trading policy itself is institutional to clarify property rights, and the allocation efficiency of environmental resources depends on the “transaction cost,” so the measures such as reducing the “transaction cost” and improving the degree of marketization can be taken to improve the system and mechanism of market factor allocation and reduce the obstacles to the transaction of various subjects; and 3) apply the carbon emission trading policy according to local conditions and promote the free flow of regional carbon emission rights. Due to the different effects of the carbon emission trading policy on FDI in different energy consumption regions, different policies should be designed for different energy consumption regions. For regions with high energy consumption, due to their strong dependence on coal and the difficulty of emission reduction, the principle of “step by step” should be followed, the emission reduction standards and regulatory intensity should be gradually improved, and regional quotas, the emission reduction technical support, and corresponding emission subsidies should be provided. For regions with low energy consumption, the free flow of carbon emission rights in regions with different energy consumption levels should be promoted appropriately, and full play to the adjustment of the market mechanism should be given.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, WS; Formal analysis, XY; Investigation, XY; Methodology, WS and ZC; Validation, XY and ZC; Visualization, WS; Data analysis, ZC; Writing-original draft, WS; Writing- review and editing, XY and ZC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1Derived from Fan Gang, Wang Xiaolu et al. “China’s Provincial Marketization Index Report (2016)” and “China’s Provincial Marketization Index Report (2018).”

2Major coal consumption provinces include 13 provinces of Hebei, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Heilongjiang, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Shandong, Henan, Hubei, Guangdong, and Sichuan. Non-major coal consumption provinces include 17 provinces of Beijing, Tianjin, Jilin, Shanghai, Fujian, Jiangxi, Hunan, Guangxi, Hainan, Chongqing, Guizhou, Yunnan, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang.

References

Ashraf, A., Doytch, N., and Uctum, M. (2020). Foreign Direct Investment and the Environment: Disentangling the Impact of Greenfield Investment and Merger and Acquisition Sales. Sustain. Account. Manag. Pol. J. 12 (1), 51–73. doi:10.1108/SAMPJ-04-2019-0184

Brack, D., Grubb, M., and Vrolijk, W. C. (1999). The Kyoto Protocol. London: The Royal Institute of International Affaires.

Chang, M.-C. (2012). Carbon Emission Allocation and Efficiency of EU Countries. Modern Economy 03 (5), 590–596. doi:10.4236/me.2012.35078

Chen, Z., Zhang, X., and Chen, F. (2021). Do Carbon Emission Trading Schemes Stimulate Green Innovation in Enterprises? Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 168 (2), 120744. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120744

Chenery, H. B., and Strout, A. (1966). Foreign Assistance and Economic Development. Am. Econ. Rev. 56 (4), 679–733. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-15238-4_9

Cole, M. A., Elliott, R. J. R., and Zhang, L. (2017). Foreign Direct Investment and the Environment. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 42, 465–487. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-102016-060916

Contractor, F. J., Dangol, R., Nuruzzaman, N., and Raghunath, S. (2020). How Do Country Regulations and Business Environment Impact Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Inflows? Int. Business Rev. 29 (2), 101640. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2019.101640

Batschauer da Cruz, C. B., Eliete Floriani, D., and Amal, M. (2020). The OLI Paradigm as a Comprehensive Model of FDI Determinants: A Sub-National Approach. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. [preprint]. doi:10.1108/IJOEM-07-2019-0517

Cui, L. B., Fan, Y., Zhu, L., Bi, Q., and Zhang, Y. (2013). The Cost Saving Effect of Carbon Markets in China for Achieving the Reduction Targets in the “12th Five-Year Plan”. Chin. J. Manage. Sci. 21 (01), 37–46. doi:10.16381/j.cnki.issn1003-207x.2013.01.007

Cui, X. (2001). Micro Theory of FDI: OL Model[J]. Manage. World 4 (03), 147–153. doi:10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2001.03.020

Das, K. C. (2013). Home Country Determinants of Outward FDI from Developing Countries. Margin: J. Appl. Econ. Res. 7 (1), 93–116. doi:10.1177/0973801012466104

Deng, Y. P., and Xu, H. L. (2013). Foreign Direct Investment, Local Government Competition and Environmental Pollution: Empirical Analysis on Fiscal Decentralization. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 23 (07), 155–163. CNKI:SUN: Zgrz.0.2013-07-024.

Dijkstra, B. R., Mathew, A. J., and Mukherjee, A. (2011). Environmental Regulation: An Incentive for Foreign Direct Investment. Rev. Int. Econ. 19 (3), 568–578. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9396.2011.00966.x

Dong, Z.-Q., Wang, H., Wang, S.-X., and Wang, L.-H. (2020). The Validity of Carbon Emission Trading Policies: Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment in China. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 11 (2), 102–109. doi:10.1016/j.accre.2020.06.001

Dou, J., and Han, X. (2019). How Does the Industry Mobility Affect Pollution Industry Transfer in China: Empirical Test on Pollution Haven Hypothesis and Porter Hypothesis. J. Clean. Prod. 217, 105–115. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.147

Dunning, J. H., and Fortanier, F. (2007). Multinational Enterprises and the New Development Paradigm: Consequences for Host Country Development. Multinational Business Rev. 15 (1), 25–46. doi:10.1108/1525383X200700002

Dunning, J. H., and Lundan, S. M. (2008). Institutions and the OLI Paradigm of the Multinational Enterprise. Asia Pac. J. Manage. 25 (4), 573–593. doi:10.1007/s10490-007-9074-z

Dunning, J. H. (1981). Explaining the International Direct Investment Position of Countries: Towards a Dynamic or Developmental Approach. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 117 (1), 30–64. doi:10.1007/BF02696577

Fang, J. Y. (2003). A Comparative Study of FDI Theory: A Literature Review. Commercial Res. 23, 7–9. doi:10.13902/j.carolcarrollnkisyyj.2003.23.003

Gao, Y., Li, M., Xue, J., and Liu, Y. (2020). Evaluation of Effectiveness of China's Carbon Emissions Trading Scheme in Carbon Mitigation. Energ. Econ. 90, 104872. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104872

Gong, M. Q., Liu, H. Y., and Jiang, X. (2019). A Study on the Impact of China’s Low-Carbon Pilot Policy on Foreign Direct Investment. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 29 (06), 50–57. CNKI:SUN:ZGRZ.0.2019-06-006.

Grossman, G., and Krueger, A. (1992). Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement. CEPR Discussion Pap. 8 (2), 223–250. doi:10.3386/w3914

Guo, H. Y., and Han, L. Y. (2008). Foreign Direct Investment, Environmental Regulation and Environmental. J. Int. Trade 8, 111–118. CNKI:SUN:GJMW.0.2008-08- 018.

Guo, W. Q., Zhang, Z. W., and Zhang, S. J. (2006). A Review of Foreign Direct Investment Theory. Sci. Technol. Manage. Res. 5, 35–38. CNKI:SUN: KJGL.0.2006-05-011.

Han, I., Liang, H.-Y., and Chan, K. C. (2016). Locational Concentration and Institutional Diversification: Evidence from Foreign Direct Investments in the Banking Industry. North Am. J. Econ. Finance 38, 185–199. doi:10.1016/j.najef.2016.10.013

Hong, M., and Chen, L. S. (2001). Quantitative and Dynamic Analysis of the OLI Variables Determining FDI in China. Rev. Urban Reg. Dev. Stud. 13 (2), 163–172. doi:10.1111/1467-940x.00038

Hu, Y. F., and Ding, Y. Q. (2020). Can Carbon Emission Permit Trade Mechanism Bring Both Business Benefits and Green Efficiency? China Popul. Resour. Environ. 30 (3), 56–64. CNKI:SUN:ZGRZ.0.2020-03-007.

Hu, M., Wang, Y., Xia, B., Jiao, M., and Huang, G. (2020). How to Balance Ecosystem Services and Economic Benefits? - A Case Study in the Pearl River Delta, China. J. Environ. Manage. 271 (12), 110917. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110917

Hymer, S. H. (1960). The International Operations of National Firms: A Study of Direct Foreign Investment. PhD Dissertation. Published Posthumously. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jin-Feng, X., Jie-Ming, C., Wen-Jie, D., Zhi-Yong, Y., and Ru-Feng, D. (2015). Carbon Reduction Policies: A Regional Comparison of Their Contributions to CO2Abatement in Six Carbon Trading Pilot Schemes in China. Atmos. Oceanic Sci. Lett. 8 (04), 233–237. doi:10.1080/16742834.2015.11447265

Kang, Y. (2018). Regulatory Institutions, Natural Resource Endowment and Location Choice of Emerging-Market FDI: A Dynamic Panel Data Analysis. J. Multinational Financial Manage. 45, 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.mulfin.2018.04.003

Kim, M. H., and Adilov, N. (2012). The Lesser of Two Evils: An Empirical Investigation of Foreign Direct Investment-Pollution Tradeoff. Appl. Econ. 44 (20), 2597–2606. doi:10.1080/00036846.2011.566187

Kyrkilis, D., and Pantelidis, P. (2003). Macroeconomic Determinants of Outward Foreign Direct Investment. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 30 (7), 827–836. doi:10.1108/03068290310478766

Lee, J. W. (2013). The Contribution of Foreign Direct Investment to Clean Energy Use, Carbon Emissions and Economic Growth. Energy Policy 55, 483–489. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2012.12.039

Leng, Y. L., Xian, G. M., and Du, S. Z. (2015). Foreign Direct Investment and Haze Pollution: An Empirical Analysis Based on Provincial Panel Data. J. Int. Trade 4 (12), 74–84. doi:10.13510/j.cnki.jit.2015.12.007

Li, Z. H., and Lu, M. H. (2004). Analysis on the Effectiveness of Preferential Tax Policies for Foreign-Invested Enterprises in China. The J. World Economy 4 (10), 15–21. CNKI: SUN: SJJj.0.2004-10-001.

Li, R., and Ramanathan, R. (2020). Can Environmental Investments Benefit Environmental Performance? The Moderating Roles of Institutional Environment and Foreign Direct Investment. Bus Strat Env 29 (8), 3385–3398. doi:10.1002/bse.2578

Lim, S.-H. (2008). How Investment Promotion Affects Attracting Foreign Direct Investment: Analytical Argument and Empirical Analyses. Int. Business Rev. 17 (1), 39–53. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2007.09.001

Liu, W. P., and Dai, Y. W. (2004). A Review on the Emission Permits Trade of Carbon in China. Probl. For. Econ. (04), 193–197. doi:10.16832/j.cnki.1005-9709.2004.04.001

Nielsen, B. B., Asmussen, C. G., and Weatherall, C. D. (2017). The Location Choice of Foreign Direct Investments: Empirical Evidence and Methodological Challenges. J. World Business 52 (1), 62–82. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2016.10.006

Nordhaus, W. D. (2007). A Review of the Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change. J. Econ. Lit. 45 (3), 686–702. doi:10.1257/jel.45.3.686

Nourzad, F. (2008). Openness and the Efficiency of FDI: A Panel Stochastic Production Frontier Study. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 14 (1), 25–35. doi:10.1007/s11294-007-9128-5

Rezza, A. A. (2015). A Meta-Analysis of FDI and Environmental Regulations. Envir. Dev. Econ. 20 (2), 185–208. doi:10.1017/S1355770X14000114

Rong, S., Liu, K., Huang, S., and Zhang, Q. (2020). FDI, Labor Market Flexibility and Employment in China. China Econ. Rev. 61, 101449. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2020.101449

Saleh, A. S., Anh Nguyen, T. L., Vinen, D., and Safari, A. (2017). A New Theoretical Framework to Assess Multinational Corporations' Motivation for Foreign Direct Investment: A Case Study on Vietnamese Service Industries. Res. Int. Business Finance 42, 630–644. doi:10.1016/j.ribaf.2017.07.007

Santos, A., and Forte, R. (2020). Environmental Regulation and FDI Attraction: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Literature. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 28 (3), 1–16. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-11091-6

Sauvant, K. P., and Mallampally, P. (2015). Policy Options for Promoting Foreign Direct Investment in the Least Developed Countries. Transnational Corporations Rev. 7 (3), 237–268. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3092314. doi:10.5148/tncr.2015.7301

Shao, Y. F., and Wang, X. B. (2014). Influence of FDI on Carbon Dioxide Emission in China: Spatial Econometrics Based on Provincial Panel Data. J. Technol. Econ. 33 (11), 68–76. CNKI:SUN:JSJI.0.2014-11-010.

Shen, G. L., and Yu, L. (2005). The Negative Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on China's Economic Development and Countermeasures. World Economy Stud. 11, 4–10. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1007-6964.2005.11.001

Shi, D., and Li, S. L. (2020). Emissions Trading System and Energy Use Efficiency — Measurements and Empirical Evidence for Cities at and above the Prefecture Level. China Ind. Econ. 9, 5–23. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2020.09.001

Sun, L., and Zhou, K. X. (2020). A Research on the Impact of China’s Low-Carbon Pilot Policies on Quality for FDI: Quasi-Natural Experimental Evidence from Construction of "Low-Carbon Cities. Southeast Acad. Res. 4, 136–146. doi:10.13658/j.cnki.sar.2020.04.014

Tang, S. J., Yang, Y. H., and Wan, F. (2018). “Research on the Spillover Effect of FDI in China,” in Conference Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Project Management (ISPM2018), Chongqing, China, July 21, 2018 (Aussino Academic Publishing House), 430–434.

Teixidó, J., Verde, S. F., and Nicolli, F. (2019). The Impact of the EU Emissions Trading System on Low-Carbon Technological Change: The Empirical Evidence. Ecol. Econ. 164, 106347. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.06.002

Wang, Q. (2021). Analysis of Factors Affecting Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment: An Empirical Study Based on Stochastic Frontier Model. Open J. Soc. Sci. 09 (3), 12–25. doi:10.4236/jss.2021.93002

Wu, L., and Zhu, Q. (2021). Impacts of the Carbon Emission Trading System on China's Carbon Emission Peak: A New Data-Driven Approach. Nat. Hazards. 107 (3), 2487–2515. doi:10.1007/s11069-020-04469-9

Wu, X. (2011). Institutional Environment and Entry Modes of Oversea Investment of Chinese Enterprises. Business Manage. J. 33 (4), 68–79. CNKI:SUN:JJGU.0. 2011-04-013.

Wurgler, J. (2001). Financial Markets and the Allocation of Capital. J. Financ. Econ. 58 (1), 187–214. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(00)00070-2

Xiao, J., Li, G., Zhu, B., Xie, L., Hu, Y., and Huang, J. (2021). Evaluating the Impact of Carbon Emissions Trading Scheme on Chinese Firms' Total Factor Productivity. J. Clean. Prod. 306 (4), 127104. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127104

Xu, Y., Wu, Y., and Shi, Y. (2021). Emission Reduction and Foreign Direct Investment Nexus in China. J. Asian Econ. 74 (1), 101305. doi:10.1016/j.asieco.2021.101305

Xuan, D., Ma, X., and Shang, Y. (2020). Can China's Policy of Carbon Emission Trading Promote Carbon Emission Reduction? J. Clean. Prod. 270, 122383. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122383

Yan, J. (1994). Review of the Dunning International Production Compromise Theory. Nankai Econ. Stud. 4 (01), 57–61. CNKI:SUN:NKJJ.0.1994-01-011.

Yeung, G. (2001). Foreign Investment and Socio-Economic Development in China: The Case of Dongguan[M]. London: Palgrave press.

Yu, F., Xiao, D., and Chang, M.-S. (2021). The Impact of Carbon Emission Trading Schemes on Urban-Rural Income Inequality in China: A Multi-Period Difference-In-Differences Method. Energy Policy 159, 112652. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112652

Yulek, M., and Gur, N. (2017). Foreign Direct Investment, Smart Policies and Economic Growth. Prog. Develop. Stud. 17 (3), 245–256. doi:10.1177/1464993417713272

Zeng, W. (2016). An Empirical Analysis of the Institutional Factors' Affection on China's Foreign Direct Investment -Based on the Perspective of Investment Motives. J. Soc. Sci. 04 (2), 88–98. doi:10.4236/jss.2016.42013

Zhang, W., and Jing, W. M. (2012). The Analysis of Chinese Institutional Factors Influence on FDI. Econ. Probl. 4 (09), 36–41. doi:10.16011/j.cnki.jjwt.2012.09.002

Zhang, S., Wang, Y., Hao, Y., and Liu, Z. (2021). Shooting Two Hawks with One Arrow: Could China's Emission Trading Scheme Promote Green Development Efficiency and Regional Carbon Equality? Energ. Econ. 101, 105412. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105412

Zhang, W., Li, J., Li, G., and Guo, S. (2020). Emission Reduction Effect and Carbon Market Efficiency of Carbon Emissions Trading Policy in China. Energy 196 (10), 117117. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2020.117117

Zhang, Y. J., Shi, W., and Jiang, L. (2020). Does China's Carbon Emissions Trading Policy Improve the Technology Innovation of Relevant Enterprises? Bus Strat Env 29 (3), 872–885. doi:10.1002/bse.2404

Zhu, P. F., Zhang, Z. Y., and Jiang, G. L. (2011). Empirical Study of the Relationship between FDI and Environmental Regulation:An Intergovernmental Competition Perspective. Econ. Res. J. 46 (6), 134–146. CNKI:SUN:JJYJ.0.2011-06-013.

Keywords: carbon emission trading policy, foreign direct investment, differences-in-differences, OLI paradigm, environment and economic development

Citation: Shao W, Yu X and Chen Z (2022) Does the Carbon Emission Trading Policy Promote Foreign Direct Investment?: A Quasi-Experiment From China. Front. Environ. Sci. 9:798438. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2021.798438

Received: 20 October 2021; Accepted: 01 December 2021;

Published: 17 January 2022.

Edited by:

Faik Bilgili, Erciyes University, TurkeyReviewed by:

Udi Joshua, Federal University Lokoja, NigeriaTheodore Metaxas, University of Thessaly, Greece

Copyright © 2022 Shao, Yu and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ziqi Chen, NDA5MzA3NTExQHFxLmNvbQ==

Wei Shao1,2

Wei Shao1,2 Xiaobo Yu

Xiaobo Yu Ziqi Chen

Ziqi Chen