- 1School of Economics and Management, Xinjiang University, Urumqi, China

Under both Chinese-style fiscal decentralization (vertical competition) and promotion tournament systems (horizontal competition), the economic development system used by the government determines whether local government competition significantly influences green total factor productivity (GTFP). Moreover, market segmentation, an important strategic tool for local government competition, will significantly impact GTFP because of the implied changes in production efficiency and blocked factor flows. This study applies GMM and the mediation effect model to explore the relationship between local government competition and GTFP from the market segmentation perspective using statistical data from 30 provinces from 2006 to 2017 in China. Overall, our results demonstrate that local government competition significantly inhibits GTFP promotion. Local government competition also has a negative impact on GTFP by promoting market segmentation. As a mediating variable, the market segmentation coefficient was statistically significant. Considering regional heterogeneity, in the eastern region, local government competition has no significant inhibitory effect on GTFP. Moreover, market segmentation has no intermediary effect. In the central and western regions, GTFP remains significantly inhibited by local government competition, and the mediation effect of market segmentation is significant. Finally, our empirical results are robust.

Introduction

In the past 40 years of reform and opening-up, China’s economy has achieved a “growth miracle,” with gross domestic product surging from approximately 367.9 billion to 99 trillion yuan in 1978 and 2019, respectively1. Simultaneously, eco-damage and environmental pollution have followed one after another, and emissions of pollutants such as industrial waste haze and greenhouse gases continue to surge (Ahmed et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2021). The China Ecological Environment Status Bulletin 2019 shows that among the 337 prefecture-level cities, 180 exceeded the ambient air quality standard, accounting for 53.4%2. Moreover, the problems of a suboptimal energy structure and low-energy utilization efficiency are more prominent. China’s coal consumption has since comprised more than 60% of the total energy consumption. Therefore, although extensive growth modes such as high capital input, high consumption of resources, and high environmental pollution have created an economic “growth miracle,” the ecological and social benefits have been seriously undermined, causing China’s economy to suffer from the low output and low efficiency (Wu et al., 2020a; Wang J. et al., 2021). Currently, China’s economy is in a critical period of transforming development, optimizing economic structure, and changing growth momentum. Promoting efficient change and achieving green economic development has become the major direction of China’s future economic development (Ouyang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020). Normally, improving green total factor productivity (GTFP) can become a win-win situation for both economic and environmental performance. Therefore, for China to nurture high-quality economic development in the new era, the deep-rooted motives damaging coordinated development of the economy and environment and further improving GTFP must be determined.

In this context, the worldwide scholarly community has explored various perspectives concerning the causes of ecological degradation (Can et al., 2021a; Ahmed et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021a). Many scholars attribute the inefficiency of Chinese environmental governance and its ecological plight to the “bottom-to-bottom competition” among local governments in environmental governance. That is, local governments compete to seek lower environmental regulation standards to entice financial and technological resources, resulting in environmental degradation (Zhang et al., 2021). Particularly, after the 1994 tax reform formalized the fiscal decentralization system, competition among local governments increased significantly, as induced by the “GDP-only” performance appraisal system. However, under constrained resources, the environmental problems caused by chaotic competition among local governments are gradually intensifying (Qian and Weingast, 1997). Meanwhile, under the goal-oriented approach of economic growth, local governments inadvertently compete to weaken environmental regulations and shelter-polluting industries regardless of ecological costs, which, in turn, has an essential impact on GTFP.

Market segmentation occurring alongside local government competition in China is often overlooked (Bai et al., 2019). Since China’s reform and opening-up, the central government has been reassigning power to local governments, including decentralizing fiscal and taxation, investment and financing, and enterprise management authorities. Although decentralization helps stimulate local development, this process also directly contributes to increasing local protectionism. Local protectionism occurs when local governments protect their key industries through administrative interventions in factor markets, setting trade barriers, or using invisible preferential policies for local economic interests, resulting in market segmentation (Li and Lin, 2017). Market segmentation not only contributes to distorting the economic operation system but also does not facilitate the optimal allocation of factor resources (Hou and Song, 2021). The Chinese government has implemented a series of policy practices to reduce the constraints of market segmentation on economic operations and factor flows. Moreover, China’s socialist market economic system has gradually improved in recent years. While the degree and scale of marketization have led to substantial development, the degree of market segmentation has gradually declined (Li et al., 2003). However, because of the constraints of institutional and stage factors, such as the household registration system, non-marketization of interest rates, fiscal decentralization, political promotion tournaments, and enterprise rent-seeking, the development of China’s factor market still lags. Existing institutional and regional segmentation results in the non-marketization of labor, capital, energy, and resource allocation, which easily affects the GTFP (Duanmu et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2021).

Currently, China still has a negative situation of local disorderly competition and market fragmentation. Combining a competent government and an effective market is an essential way to promote GTFP. Therefore, under regional green development, ecological civilization construction, and proper handling of government-market relationships, exploring how to endow the efficiency shift and power shift of economic operations through market and government actions is highly significant for facilitating GTFP improvement to empower high-quality economic development. This study has the following objectives. Based on a more comprehensive portrayal of the relationship between local government competition, market segmentation, and GTFP, we empirically analyze the mechanism of local government competition on GTFP from a market segmentation perspective. Simultaneously, this study must further confirm and explain the following key questions. In the context of competition for economic growth, is local government competition a significant contributor to GTFP? If market segmentation has a transmission effect, is there regional heterogeneity in the effect of market segmentation on GTFP? How does local government competition act on GTFP through market segmentation? Solving these problems would be of great theoretical and practical significance for realizing the transformation of the mode of competition for local governments and breaking the situation of market segmentation to promote the construction of a new mechanism of green development in China from the perspective of the connection between the government and the market.

The marginal contribution of this study is as follows. First, based on the actual market-oriented system reform situation, this study brings local government competition, market segmentation, and GTFP into a unified analysis framework. We then discuss the influence mechanism of local government competition on GTFP by market segmentation. This not only enriches the green development theory but also provides a new research perspective for exploring sustainable economic development. Second, a three-stage EDA model was applied for measuring the GTFP. Considering the bias of controlling endogenous estimation, we verify the intrinsic mechanisms of local government competition, market segmentation, and GTFP to determine the dynamic path of urban green development. Third, from the regional heterogeneity perspective, this study analyzes the enhancement or offsetting of the effect of local government competition on GTFP through market segmentation. Our results can provide some guidance for more accurate analyses of the possible problems and drawbacks of the Chinese government and the scientific formulation of relevant policies. Finally, this paper provides a policy basis and theoretical support for developing countries similar to China’s economic development.

The following research arrangements are as follows. Literature review presents a review of studies related to local government competition, market segmentation, and GTFP. Three-stage DEA model presents a three-phase DEA model to measure and analyze GTFP. Methods includes the construction of the empirical model and the description of variables. Results briefly describes the empirical results. Discussion presents the analysis and discussion of the results. Finally, Conclusion and policy implications summarizes the study and provides the corresponding policy suggestions.

Literature Review

Local Government Competition and Green Total Factor Productivity

As the economic growth leader and executor of environmental protection policy, the local government’s competitive behavior has significant influence on regional economic growth and environmental quality, and this has been examined by scholars. However, few studies have directly examined the effect of local government competition on GTFP. Most existing literature focus on how local government competition affects economic growth or environmental quality. Two views support that economic growth is affected by local governments. The first is that government competition can significantly promote regional economic growth (Oates, 1999). Keen and Marchand, (1997) believe that local government competition can limit the interests of special interest groups, which are beneficial for regional economic development. Hence, under China’s special political system, local governments generally use public expenditure and tax policy adjustments to compete for liquidity resources, which inevitably lead to strategic competition (Yılmaz, 2013; Chirinko and Wilson, 2017). Yan et al. (2013) analyzed the path of local government competition on economic growth and found that local governments can encourage investment and accelerate economic growth through land price competition and land revenue expenditure competition. Finally, the diversity of government competition behaviors (financial resource, fiscal expenditure, and infrastructure competition among local governments) and environmentally friendly goods, contributes to local governments having positive effects on economic growth (Hatfield and Kosec, 2013; Deng and Xu, 2013; Yushkov, 2015; Canavire-Bacarreza et al., 2019; Ding et al., 2019).

Second, local government competition inhibits regional economic growth. Some scholars believe that the government increases the intensity of tax incentives and introduces regional competition into the “competition towards the bottom line” to attract residents, enterprises, and capital to the region. The direct consequence is the reduction in the supply capacity of government public goods (Can et al., 2021b). From this perspective, local government competition harms economic growth by distorting tax burdens, reducing the efficiency of resource allocation, and widening regional economic disparities (Cai and Treisman, 2004; Aaberge et al., 2019; Pan et al., 2020; Thanh et al., 2020). Su et al. (2021) highlight that behaviors such as local protectionism, industrial isomorphism, over-investment, and investment wars accompanying the competition process eventually inhibit regional economic growth. Guang-Bin (2005) argues that while administrative decentralization and tax incentives cause local government competition, it does not necessarily help increase investment in infrastructure and local protectionism. However, inter-governmental opportunism and gaming are the important factors affecting economic development. Additionally, Qingwang and Junxue (2009) argued that the 1994 tax-sharing reform significantly changed the pattern of strategic interaction between local governments, effectively curbing competition between extreme regions and significantly weakening competition between local governments, inhibiting regional economic growth. Using a panel dataset of 63 provinces in Vietnam from 2006 to 2017, Thanh and Nguyen (2021) found that decentralization drives significant differences in TFP between high and low self-financing provinces. However, decentralization in high self-financing provinces results in bottom-up competition because of governance reforms. Finally, some scholars have highlighted the uncertainty of local government competition in economic growth. Tang et al. (2011) highlighted that local government competition is a deep-rooted cause of investment impulses in provinces. This, in turn, causes economic fluctuations in China’s macroeconomic regulation.

There may be two aspects wherein environmental pollution is affected by local governments: bottom-to-bottom competition and top-to-top competition. In the case of bottom-to-bottom competition, local governments may compete for high-quality resources, relax environmental control, and indulge enterprises’ pollution emission behaviors to encourage promising enterprises to enter the local area. This will lead to environmental degradation and form the “bottom-to-bottom competition” effect of environmental pollution (Oates and Portney, 2003; Banzhaf and Chupp, 2012; van der Kamp et al., 2017; Kuai et al., 2019). Cumberland, (1980) believed that competition among governments would reduce pollution supervision of enterprises and cause environmental deterioration. Meanwhile, under fiscal decentralization, environmental concerns will be ignored (Li et al., 2019). Under top-to-top competition, the local government may improve local environmental supervision standards and transfer pollutants to other areas by adopting more stringent environmental policies to improve the local environmental quality, which forms the “top-to-top competition” effect (Glazer, 1999; List and Gerking, 2000; Albornoz et al., 2009; Haufler and Maier, 2019). Levinson (2003) argued that government competition will help the government prioritize the ecological environment, create environmental conditions for attracting investment, and improve environmental quality. Yan (2012) found that fiscal decentralization can significantly weaken investment in environmental governance through government competition, which, in turn, has positive impact on environmental pollution. Zhang et al. (2021) applied a spatial autoregressive (SAR) model to confirm that local government competition exacerbates haze pollution under factor market distortions.

Market Segmentation and Green Total Factor Productivity

As an equilibrium result of local government competition, market segmentation is mainly manifested in the fact that local governments hinder the cross-regional flow of resources through financial support and policy preference to protect local enterprises and the economy from external fierce impact (Ke, 2015). Since Young (2000) proposed the existence of market segmentation in China, many scholars have discussed the many aspects of market segmentation. Additionally, researchers have found significant differences in the effect of market segmentation on GTFP in different periods (Duffee, 1996; Bancel et al., 2009; Guesmi et al., 2014). In the short term, market segmentation may be conducive to promoting GTFP. Pan et al. (2020) highlighted that local governments have an incentive to divide the market in terms of economic aggregate, fiscal revenue, and employment stability. For example, market segmentation allows local governments to not only protect the market share of local enterprises but also support the development of enterprises with poor local competitiveness and vulnerable industries. Therefore, the local government can obtain sustainable economic growth and more fiscal and tax revenue in the region, which will promote GTFP (Weitzman, 1989; McNabb and Whitfield, 1998).

However, in the long run, interregional market segmentation hinders the flow of factors and spatial mismatch of resources. On the one hand, market segmentation inhibits the free flow of production factors such as resources, energy, and labor among regions. This results in a low level of efficiency in the use of production factors and failure of economies of scale (Poncet, 2003; Hsieh and Klenow, 2009; Hubbard, 2014). For example, Hou and Song (2021) noted the positive spillover effects of market integration on GTFP not only within regions but also in neighboring regions. Simultaneously, in the market segmentation, local protectionism prevails and collusion between government and enterprises is serious, which leads to a lack of fairness and marketization in energy and resource distribution. This significantly inhibits resource allocation and utilization efficiency and, in turn, the improvement of GTFP. Qin et al. (2020) found that market segmentation exacerbates the control of oligopolistic firms in the market, which not only compresses the survival space of SMEs but also severely inhibits the efficiency of factor allocation. On the other hand, market segmentation also hinders diffusion and spillover of technological innovation and regional technical cooperation to a certain extent, which makes applying and promoting new energy-saving and emission-reducing technologies across regions through marketization difficult (Duanmu et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Additionally, trade barriers formed by market segmentation worsen the benign competition between markets, resulting in enterprises losing the power and pressure of technological innovation (Bai et al., 2004; Epifani and Gancia, 2011; Ye and Zhang, 2017). Sun C. et al. (2020) suggested that market segmentation negatively affects the environmental efficiency of the electricity sector by inhibiting technological innovation, and this phenomenon is more significant in regions with poorer institutional quality. Market segmentation also indirectly affects GTFP through the channels of industrial structure, productivity, export trade, investment promotion, and so on (McNabb and Whitfield, 1998; Anouliès, 2016; Chen and Huang, 2016). For example, Bai et al. (2019) highlighted that market segmentation intensifies competition among regions and increases the incentive for local governments to sacrifice the ecological environment for economic growth. This reduces the threshold of environmental regulation and environmental law enforcement, which has negative impact on GTFP. Cheng and Jin (2020) found that agglomeration economies significantly enhance GTFP by improving technical efficiency and technological progress significantly. However, market segmentation can encourage local protectionism, ultimately negatively impacting regional economic growth efficiency. Lai et al. (2021) highlight that market segmentation has an inverted U-shaped effect on the current and future industrial transformation of the region, which is key in improving GTFP.

In summary, a rich theoretical framework and research basis have been proposed by previous scholars to elaborate on the mechanism among local government competition, market segmentation, and GTFP. However, the relationship among the above three needs further discussion. Current research focuses on the impact of local government competition on economic growth and environmental pollution and the relationship between market segmentation and GTFP. Research on local government competition on GTFP in China from the market segmentation perspective is lacking. For instance, Jin et al. (2020) found that excessive cross-jurisdictional competition has a negative impact on GTFP, while moderate competition is important for promoting GTFP. Moreover, Song et al. (2018) reached a similar conclusion. Bin et al. (2016) revealed that strategic decentralization by local governments contributes to GTFP and positively moderates the dampening effect of FDI on GTFP. When measuring market segmentation, scholars mostly consider market segmentation in the product market as a characterization index, which lacks the analysis of market segmentation in other markets. Therefore, this study applies the three-stage DEA model to measure the GTFP from 2006 to 2017. Additionally, market segmentation is incorporated into the framework of local government competition on GTFP. Additionally, the mediation effects model and the generalized method of moments model were used to examine the transmission mechanisms of market segmentation, which further broadened and refined existing research related to GTFP.

Three-Stage DEA Model

Three-Stage DEA

The relative efficiency of the decision-making unit (DMU) is affected by many factors, such as management inefficiency, statistical noise, and environmental factors. However, the traditional DEA model attributes environmental factors and statistical noise to management inefficiency, which will conceal real efficiency value. Additionally, the analysis of relative efficiency is only affected by management factors. Therefore, to filter and remove the impact of nonoperating factors on efficiency to allow measured efficiency values to more accurately reflect the efficiency level of decision evaluation units, this study uses a three-stage DEA model to measure GTFP (Fried et al., 2002). Through stochastic Frontier analysis, the effects of environmental factors and statistical noise on relative efficiency were effectively eliminated to ensure the robustness of calculation efficiency.

First Stage: Undesirable-Outputs Model

This study selects an undesirable output model (Shyu and Chiang, 2012; Lu et al., 2020). The undesirable output model includes desirable output and undesirable output, which can effectively reduce the influence on raw data changes and subjective factors. The model takes the following form: Set

Here, if

Second Stage: SFA Regression

Because the relative efficiency obtained in the first stage is easily affected by management inefficiency, environmental factors, and statistical noise, this study uses stochastic Frontier analysis (SFA) to incorporate the above factors into a stochastic Frontier analysis model based on input redundancy. Simultaneously, this study takes the input redundancy value of each decision-making unit obtained in the first stage as the explanatory variable. Environmental factors were selected as the explanatory variables. Through regression and adjustment of the SFA, the decision-making units are introduced in the same external environment. The SFA regression model is constructed as follows:

where

Then, we use the regression results of the SFA model

where

where

Third Stage: Constructing a Green Total Factor Productivity Index

The adjusted input value and original output value obtained in the second stage are introduced into the undesirable output model to calculate the relative efficiency. Using the regression results of the second stage, we adjust the input of each decision-making unit to keep the output unchanged. The relative efficiency value excluding environmental factors and statistical noise is obtained using the undesirable outputs model. Finally, the efficiency value is analyzed, and that based on the GTFP index is constructed.

Index Selection and Data Processing

This study estimates the GTFP of China under environmental constraints. The input variables, desired outputs, undesired outputs, and environmental variables are treated as follows:

Input variables. Capital stock, labor, and energy are required in the production process. Capital stock is measured by the regional total investment in fixed assets and the fixed assets investment price index. The specific calculation equation is as follows:

where

Output variables. The desired outputs are expressed as the GDP of the provinces. Considering the price changes, this study takes 2006 as the base period to deal with the constant price of GDP. Six types of pollution indicators were selected to measure undesired outputs, including industrial sulfur dioxide emissions, total industrial wastewater emissions, industrial nitrogen oxide emissions, industrial smoke (powder) dust emissions, industrial chemical oxygen demand (COD) emissions, and industrial ammonia nitrogen emissions.

Environment variable. Simar and Wilson (2007) highlighted that environmental variables should satisfy the so-called separation hypothesis, that is, select those factors that have an impact on GTFP but are not within the subjective control range of the sample. Therefore, financial development, urbanization, industrial structure, and openness are regarded as environmental variables of the GTFP. Financial development is reflected in per capita GDP (Zhao et al., 2020). The index for measuring the degree of urbanization is the resident population divided by the total population at the end of the year (Sun et al., 2014). This study uses the added value of the tertiary industry divided by the added value of the secondary industry to measure industrial structure (Yang et al., 2021b). Openness is based on the total FDI amount of foreign direct investment (Wu et al., 2020b).

Calculation Results of Green Total Factor Productivity in China

First-Stage Estimation Results

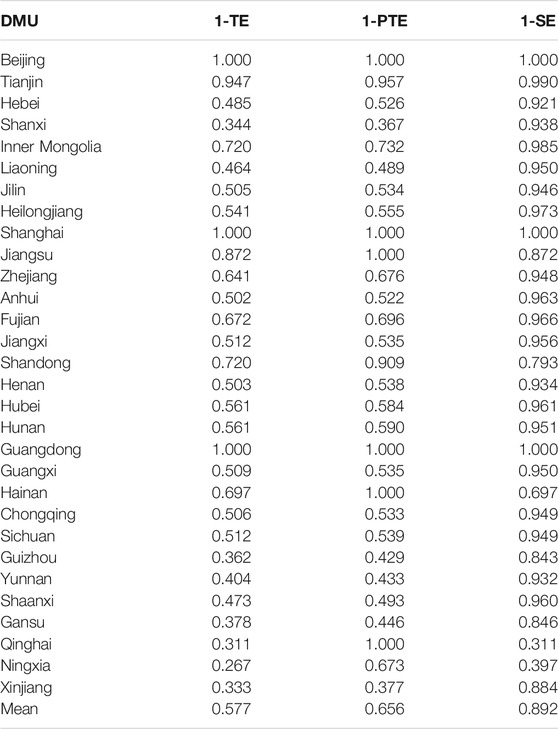

In the first and third stages, DEA solver Pro 5.0 is used to measure the efficiency value. Table 1 shows that when ignoring the interference of environmental factors and random errors, the average value of GTFP,

The Second-Stage Estimation Results

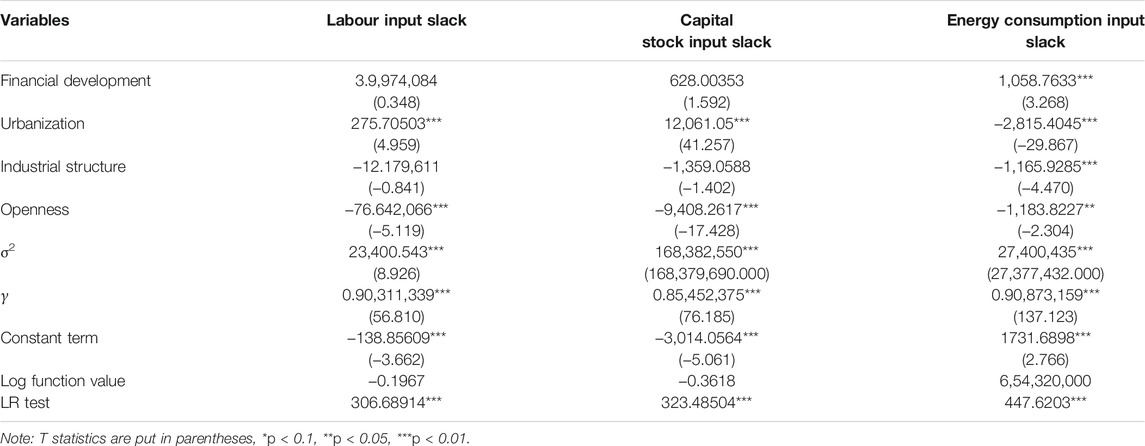

Hence, urban unit employment, capital stock, and energy consumption relaxation are considered dependent variables. Stock SFA regression model is then established with four external environmental variables: financial development, urbanization, industrial structure, and openness as independent variables. Table 2 indicates that the LR one-sided test has passed the significance test. This demonstrates that the SFA method has strong applicability.

The Third-Stage Estimation Results

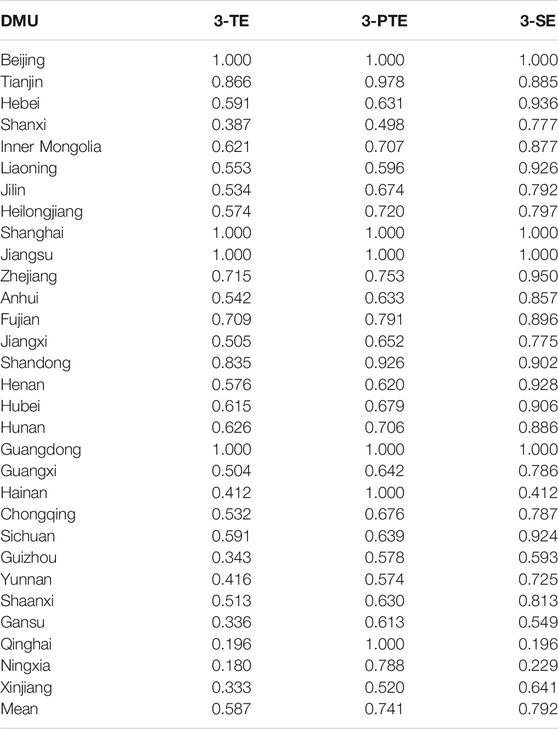

After eliminating environmental factors and statistical noise, the efficiency of the third stage changed significantly compared with that of the first stage. This indicates that it is not objective and realistic to attribute all the factors affecting efficiency to management factors without eliminating environmental factors and statistical noise. Table 3 shows that after the second stage of adjustment, the average value of GTFP is 0.587, which is higher than the preadjustment efficiency value, but still at a low level. This shows that enterprises can achieve the original output level even if the input is reduced by 41.3% by improving resource utilization efficiency and management. The average value of the adjusted

The average value of

Methods

Model Construction

For analyzing GTFP, most scholars ignore the systematic bias that can result from time-lagged effects. Therefore, this study introduces a one-period lag of the explanatory variables into the benchmark model to constitute a more accurate dynamic panel model, which enables the dynamic interpretation of the model. However, generally endogenous problems in the dynamic models exist. To solve the endogeneity problem, Arellano and Bond (1991) proposed a generalized method of moments (GMM) using instrumental variables to derive the appropriate moment conditions, known as the “Differential Generalized Method of Moments (DIFF—GMM).” The basic principle of the method is to first perform a first-order difference transformation on the original model to eliminate the individual heterogeneous terms in the model. Then, for the transformed difference equation, the lagged variables of the endogenous variables are treated as instrumental variables of the endogenous variables. Although the DIFF-GMM approach reduces the impact of endogeneity on model estimation, DIFF-GMM suffers from a serious “weak instrumental variable” issue in the limited sample condition, resulting in worse accuracy of coefficient estimation results. A solution to this problem was proposed by Arellano and Bover (1995), who proposed the “system generalized method of moments (SYS-GMM) approach” based on a new composite moment condition. The SYS-GMM approach not only provides simultaneous estimation of the original model and the differentially transformed model but can also correct for unobserved individual heterogeneity issues, omitted variable bias, measurement error, and potential endogeneity that often affect model estimation when using mixed OLS and fixed effects methods. Additionally, the SYS-GMM approach reduces the potential bias because of the use of first-order DIFF-GMM estimation approaches. Based on this, the two types of methods of SYS-GMM and DIFF-GMM are chosen to analyze the research problem, where the DIFF-GMM plays more of a robustness check role and the SYS-GMM reflects more of the estimation results of the research issue3. The equation is set as follows:

where i represents the province,

The mediation effect model uses the third variable to explore the internal mechanism of the independent variable influencing the dependent variable. If local government competition

Here,

The biggest advantage of this method is that the probability of making the first kind of error in statistics is very low, which is usually lower than the significance level, thus ensuring results validity.

Variables Specification

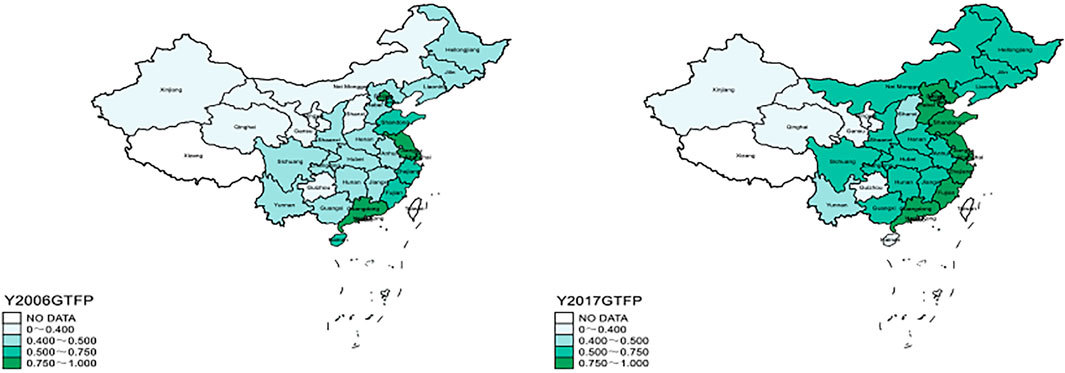

1)Explained variables. GTFP is measured by the third-stage efficiency measured by the three-stage DEA model. Additionally, this article uses Stata 15.0 software to draw the distribution map of China’s GTFP. Owing to limited space, this study only lists the distribution of GTFP in 2006 and 2017. Figure 1 shows that considering geographical distribution, areas with higher GTFP are mainly concentrated in the eastern coastal areas, such as Beijing, Tianjin, Guangdong, Shandong, Fujian, Shanghai, and Jiangsu. However, with time, the number of green areas in China has gradually increased. The promotion of GTFP mainly spreads from the eastern coastal areas to the central region, which shows that the green development policy implemented by China has achieved remarkable results. Although the Chinese government has since faced serious environmental pollution, the central government has always prioritized the construction of ecological civilization and implemented a strict environmental protection system. Simultaneously, the construction of ecological civilization is constantly emphasized by the central government in the assessment indicators of local government officials. These encourage local government officials to prioritize the green elements of economic growth and promote the GTFP.

2)Core explanatory variables

Among them,

3)Mediation variables. Based on the above theoretical analysis, this study selects the market segmentation index as the mediation variable. However, the trade law, production method, and specialization index method used in the existing literature to measure market segmentation have inherent defects, and forming a panel database is difficult (Naughton, 1999; Young, 2000; Poncet, 2003; Bai et al., 2004). Therefore, referring to Shao et al. (2019), this study adopts the relative price index analysis method to measure 65 pairs of market segmentation indices of neighboring provinces and then merges the 65 pairs of indexes of adjacent provinces to obtain the market segmentation index of each province and its adjacent provinces. For instance, Beijing’s market segmentation index is the average value of the market segmentation index between Beijing and Tianjin, and between Beijing and Hebei. The market segmentation indices of other provinces and cities adopt the same calculation method. Thus, a total of 360 (= 30 × 12) market segmentation observations are obtained, which show the changes in the market segmentation degree of 30 provinces and all adjacent provinces.

4) Control Variables.

This study selects the following control variables while eliminating the environmental variables that affect GTFP.

Government expenditure

Human capital

Marketization

Intellectual property protection

Transport infrastructure

Informationalized level

Data Sources

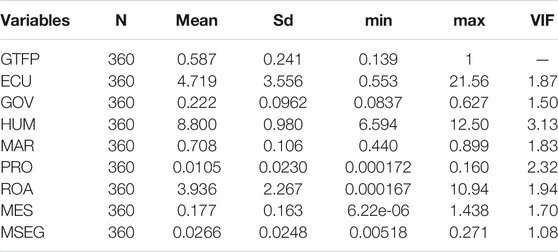

The original data used in the above variables are derived from the China Environmental Statistical Yearbook, China Financial Statistical Yearbook, China Energy Statistical Yearbook, Provincial Statistical Yearbook, China Macro Statistical database, and China Labor Force Statistical Yearbook. Table 4 shows the multicollinearity test and the descriptive statistics of the data. The variance inflation factor (VIF) of each variable is less than 10, so the multicollinearity problem of the explanatory variables is within the controllable range5.

Results

Benchmark Regression Results

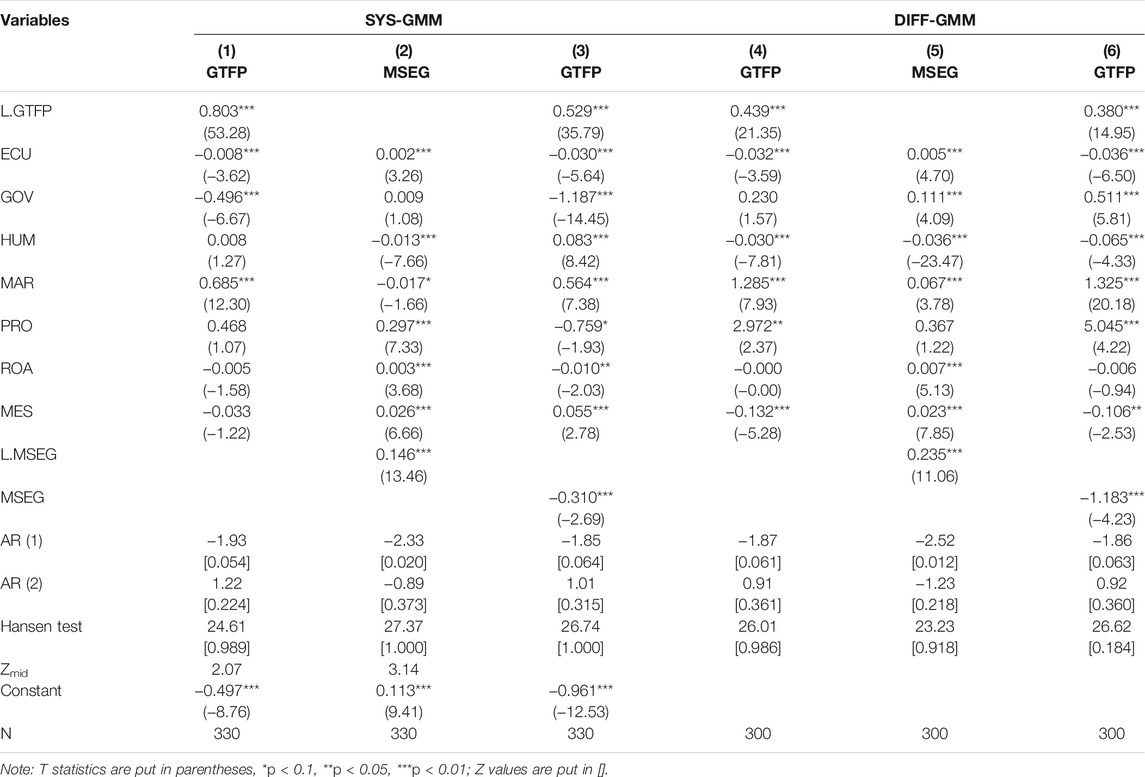

To verify the robustness of the results, the regression results of the system random effect model, fixed effect model, SYS-GMM, and DIFF–GMM models are presented (see Table 5). The coefficients of

Transmission Mechanism Analysis

In the following, based on the double mechanism test of the SYS-GMM and DIFF-GMM models, the transmission mechanism is analyzed from the path of market segmentation (see Table 6). The results of the AR 2) test in Columns (1)–6) show that there is no second-order autocorrelation in random error terms, and the Hansen test results show that the selection of instrument variables is effective. Columns 1) and 4) imply that local government competition inhibits the GTFP. The estimation coefficients of local government competition in Columns 2) and 5) are significantly positive, indicating that regional competition intensifies market segmentation. In Column (3), the estimated coefficients of

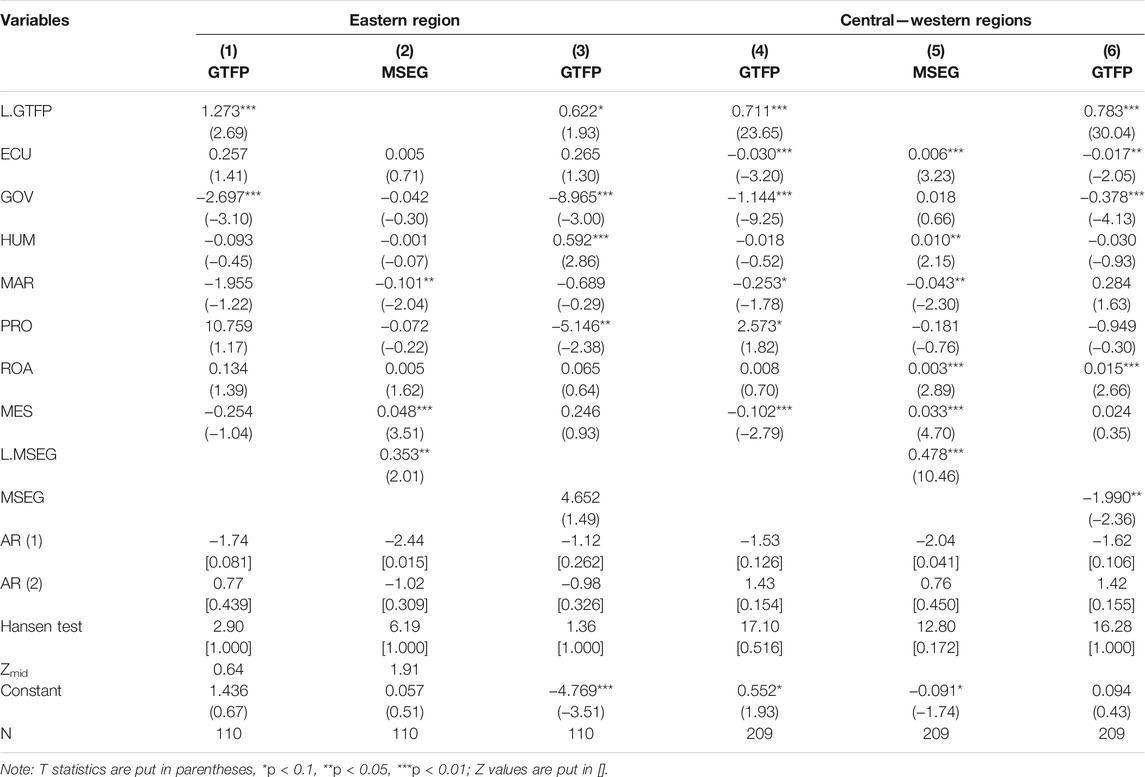

Regional Heterogeneity

Given China’s unique geographical conditions and strong heterogeneity of resource endowment, significant differences in the forms of local government competition exist, leading to great differences in performance incentives in the eastern and central-western regions (Wu et al., 2021). Therefore, this study divides the research samples into eastern, central, and western regions to analyze the regional heterogeneity of the results of this study (see Table 7).

The AR (2) test results show that there is no second-order autocorrelation in the random error term. The Hansen test shows that the instrumental variable selection is effective. In columns 1)–(3), the effect of local government competition

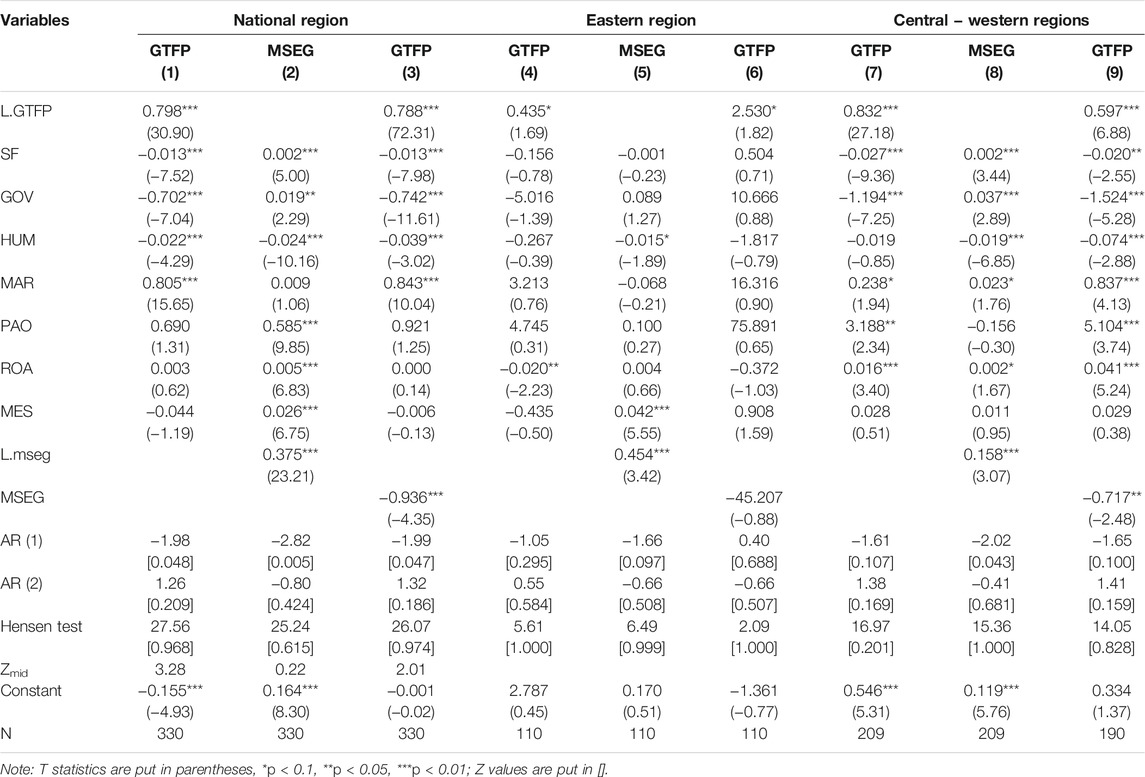

Robustness Test

Referring to Zhang et al. (2019), competition intensity (SF) is used as the local government competition proxy variable, and the specific measurement method is as follows:

where

Discussion

Discussion of Benchmark Regression Results

Table 5 indicates that the local government’s competition policy, intended to match the economic level of the surrounding areas or the economically developed regions in China, will reduce GTFP in Table 5. Our findings differ from those of Jin et al. (2020), who confirm that local government competition exhibits an inverted U-shaped relationship with GTFP. However, Hong et al. (2020) and Zhang et al. (2021) argued that unregulated competition among local governments contributes to deterioration of environmental quality and reduction of GTFP. Hence, the above results can be interpreted from the following perspectives: to obtain significant economic growth performance, local governments will spare no effort to compete for production factors, enrich the mode of production, and increase the scale of economic growth to maximize economic performance in a limited term (Keen and Marchand, 1997; Oates, 1999; Canavire-Bacarreza et al., 2019). However, most productive projects with small investments and quick results are concentrated in the secondary industry and are both characterized by high pollution and high-energy consumption, which may not be conducive to promoting GTFP (Yushkov, 2015). Second, local governments will also have horizontal competition in terms of fiscal expenditure. For example, local governments prefer to invest in projects such as high-return, quick-impact infrastructure, and expansion of traditional businesses and reduce spending on environmental protection and energy conservation. Additionally, local governments often ignore the slow-acting and heavily invested public services represented by environmental governance, which leads to continued environment deterioration. Finally, owing to the externality of environmental governance, local governments in adjacent regions have been unable to control pollution to prevent free-riding and have fallen into the prisoner’s dilemma. Hence, local governments have no incentive to prevent and control pollution, further inhibiting GTFP.

Discussion of Transmission Mechanism Analysis

Columns 1) and 4) indicate that local government competition inhibits GTFP improvement in Table 6. Columns 2) and 5) indicate that interregional competition intensifies market segmentation. In Column (3), the local government competition

Market segmentation inhibits the free flow of production factors such as resources, energy, and the labor force among regions (Young, 2000). The production activities in some regions with relatively abundant energy and resource endowments are limited because of insufficient matching of production factors (Li and Lin, 2017). Meanwhile, in market segmentation, local government intervention leads to a lack of normal and necessary market competition, and there is much collusion between governments and enterprises (Shao et al., 2019). Local governments manage the initial distribution of natural resources, especially that of energy and other production factors. Hence, a close relationship with the government enables enterprises to acquire advantages in price or tilt in quantity in resource allocation, which puts enterprises not closely related to the government in an inferior position because of the lack of fairness in the market environment (Li and Lin, 2017). The above results lead to a lack of fairness and marketization in the distribution of energy and resources, which seriously reduces the allocation efficiency and ultimately inhibits GTFP (Duanmu et al., 2018; Bian et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2020).

Discussion of Regional Heterogeneity

In the eastern region, local government competition will not significantly inhibit GTFP and promote market segmentation. The mediation effect of market segmentation on local government competition and GTFP does not exist. Our findings are reasonable in that they are also a useful supplement to the studies of Hou and Song (2021), Wang X. et al. (2021), and Zhang et al. (2021). Economic development in the central and western regions is not as good as that in the eastern regions. Moreover, there are a large number of enterprises, and most of which produce light industrial products and high-tech products (Zhang et al., 2021). The performance evaluation standards of the government departments were relatively high. When pursuing economic growth targets, they also prioritize sustainable economic development, presenting a situation of “top-to-top competition” (Wu et al., 2020a). Additionally, the eastern region is rich in capital and labor resources, and the abundance of certain factor resources also weakens the influence of distortion of the factor resource allocation brought about by this type of market segmentation, thus weakening the inhibition of GTFP.

However, Columns (4)–6) indicate that the mediation effect of market segmentation on local government competition and GTFP exists in the central and western regions. On the one hand, owing to the relative lack of financial funds, when local governments implement capital market segmentation, local enterprises lack the necessary funds to innovate and improve their productivity. Hence, enterprises cannot achieve scale expansion and technology upgrade. Finally, the upgrading and optimization of the industrial structure are hindered, and GTFP is also reduced. On the other hand, to complete the performance appraisal and pursue economic growth for the central and western regions, government officials often adopt the “yardstick competition” strategy, causing the economic development model to consider only quantity while neglecting quality. Furthermore, eco-environmental regulation is ignored, and flow factors are absorbed in large quantities to support economic growth in this region. Finally, it will fall into the dilemma of “race to the bottom,” which will inevitably lead to local protection and market segmentation (Zhang et al., 2021). However, market segmentation causes deficits in enterprises’ power to improve their operations, hinders free flow of factors, and reduces optimal resource allocation in the central and western regions. Moreover, market segmentation harms system innovation and management reform of enterprises, thus reducing their operational efficiency (Bian et al., 2019). Finally, market segmentation reduces the willingness of enterprises to pursue technological innovation, thus inhibiting the R and D of green technologies and GTFP.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

Local government competition (ECU) is crucial in promoting economic growth in China. Exploring the role of market segmentation and GTFP is highly significant to the green and steady development of the regional economy. Using statistical data from 30 provinces in China from 2006 to 2017, this study examines the impact of ECU on GTFP and investigates the mediating effect of market segmentation. Our results are as follows. 1) ECU significantly inhibits increase in GTFP. 2) ECU can not only directly inhibit the promotion of GTFP but also indirectly inhibit GTFP through market segmentation, and market segmentation as a mediation variable is very significant. 3) Considering regional heterogeneity, the effect of ECU on GTFP in the eastern region is positive, but not significant. Moreover, local government competition does not inhibit the growth of GTFP through market segmentation. Hence, ECU promotes market segmentation and inhibits the promotion of GTFP in the central and western regions, and ECU can inhibit the growth of GTFP through market segmentation.

Based on the above research conclusions, the author proposes the following policy implications. Formulating a single assessment index by the superior government is the root of local government competition. To achieve political goals, local governments sacrifice long-term interests for short-term and rapid economic development. Moreover, the GDP-oriented performance appraisal system has been widely criticized by society. Therefore, policymakers must improve the performance assessment system, reform the assessment system of local government officials, and facilitate the establishment of a local government competition system guided by high-quality economic development. Additionally, as performance appraisal of local government and the promotion incentive system of officials have strong guiding effect on local government behavior, content related to green development should be added to the performance evaluation index of local government by policymakers. Hence, policymakers should build a government performance appraisal system with economic and environmental coordination.

Second, market segmentation mainly manifests in the direct intervention of local governments through administrative means to restrict market access conditions and enterprise competition. Therefore, policymakers should establish a unified and open market system with orderly competition to further optimize the business environment. Moreover, market access conditions should be further relaxed. A system with a negative list of market access should be implemented uniformly throughout the country. Policymakers should ensure that all regions and all market entities have equal access to the market by law and prohibit all regions from creating a negative list of the nature of market access. This is to ensure fair competition among all market entities. Moreover, policymakers should allow local market regulators to conduct independent supervision and increase enforcement against unfair competition. Simultaneously, preventing and stopping unfair competition, restricting competition in market economic activities, and creating a market environment with fair competition are necessary.

Third, policymakers should formulate preferential tax policies to strengthen support for enterprises’ technological innovation. Encouraging enterprises to develop green technology and building a green low-carbon circular development of the economic system will help them achieve green development. Policymakers should increase investment in enterprise technology incubation and R&D to develop the economy and improve GTFP while protecting ecosystem. Additionally, regional development was not balanced. In green transformation, policymakers need to implement differentiated economic policies according to local conditions.

Although this study extensively explores the impact of local government competition on GTFP based on the factor market segmentation perspective, certain limitations deserving further investigation remain. First, this study empirically verifies the role of local government competition on GTFP under the factor market segmentation scenario, which lacks analysis of the influence mechanism of local government competition on GTFP. Therefore, a more in-depth analysis of the influence mechanism will be informative for future research. Second, this study mainly uses provincial-level data for investigating the relationship between local government competition and GTFP based on the factor segmentation perspective. Further research can analyze the impact of local government competition on GTFP based on the market segmentation perspective at the prefecture and county levels, which will provide more precise policy guidance for enhancing GTFP. Finally, this study measures local government competition from the economic competition perspective, which has not been fully established as a comprehensive measure of local government competition. Therefore, more comprehensive construction of local government competition indicators can be conducted in the future using big data technology. For example, local government competition can be remeasured by collecting content about local government competition published on each provincial government’s main office website and official media through tools such as Python.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

JT: grasp the theme and research direction, FQ: empirical research and data.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1See in more detail: http://www.stats.gov.cn/.

2See in more detail: http://www.mee.gov.cn/hjzl/sthjzk/zghjzkgb/202006/P020200602509464172096.pdf.

3Meanwhile, appropriate instrumental variables can make the estimation results more accurate, thus the Sargan test or Hansen test for the validity of instrumental variables is necessary. The validity of the moment condition can be performed by Sargan test or Hansen test with the original hypothesis that all instrumental variables are exogenous. Therefore, if the instrumental variables are valid, the original hypothesis should not be rejected. However, Iqbal and Daly (2014) argued that the Sargan test method is valid only if the disturbance term is homoskedastic. In addition, Bowsher (2002) suggested that the Sargan test is difficult to reject the original hypothesis when the sample size is small and the instrumental variable is usually considered valid, while the original hypothesis of serially uncorrelated errors is over-rejected in one-step GMM estimation. In view of the above-mentioned disadvantages of the Sargen test and the fact that the Hansen test is often used in practice, the Hansen test is chosen in this article to test the validity of the instrumental variables.

4Discussion on the disturbance term

5Following Hair et al. (1995), when the tolerance of the independent variable is greater than 0.1, a range of variance inflation factors less than 10 is acceptable.

References

Aaberge, R., Eika, L., Langørgen, A., and Mogstad, M. (2019). Local Governments, In-Kind Transfers, and Economic Inequality. J. Public Econ. 180, 103966. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.09.015

Ahmed, Z., Asghar, M. M., Malik, M. N., and Nawaz, K. (2020). Moving towards a Sustainable Environment: the Dynamic Linkage between Natural Resources, Human Capital, Urbanization, Economic Growth, and Ecological Footprint in China. Resour. Pol. 67, 101677. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101677

Ahmed, Z., Cary, M., Shahbaz, M., and Vo, X. V. (2021). Asymmetric Nexus between Economic Policy Uncertainty, Renewable Energy Technology Budgets, and Environmental Sustainability: Evidence from the United States. J. Clean. Prod. 313, 127723. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127723

Albornoz, F., Cole, M. A., Elliott, R. J. R., and Ercolani, M. G. (2009). In Search of Environmental Spillovers. World Economy 32 (1), 136–163. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2009.01160.x

Anouliès, L. (2016). Are Trade Integration and the Environment in Conflict? the Decisive Role of Countries' Strategic Interactions. Int. Econ. 148 (148), 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.inteco.2016.06.001

Arellano, M., and Bond, S. (1991). Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations. Rev. Econ. Stud. 58 (2), 277–297. doi:10.2307/2297968

Arellano, M., and Bover, O. (1995). Another Look at the Instrumental Variable Estimation of Error-Components Models. J. Econom. 68 (1), 29–51. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(94)01642-d

Bai, C.-E., Du, Y., Tao, Z., and Tong, S. Y. (2004). Local Protectionism and Regional Specialization: Evidence from China's Industries. J. Int. Econ. 63 (2), 397–417. doi:10.1016/s0022-1996(03)00070-9

Bai, J., Lu, J., and Li, S. (2019). Fiscal Pressure, Tax Competition and Environmental Pollution. Environ. Resource Econ. 73 (2), 431–447. doi:10.1007/s10640-018-0269-1

Bancel, F., Kalimipalli, M., and Mittoo, U. R. (2009). Cross-listing and the Long-Term Performance of ADRs: Revisiting European Evidence. J. Int. Financial Markets, Institutions Money 19 (5), 895–923. doi:10.1016/j.intfin.2009.07.004

Banzhaf, H. S., and Chupp, B. A. (2012). Fiscal Federalism and Interjurisdictional Externalities: New Results and an Application to US Air Pollution. J. Public Econ. 96 (5-6), 449–464. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.01.001

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 51 (6), 1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bian, Y., Song, K., and Bai, J. (2019). Market Segmentation, Resource Misallocation and Environmental Pollution. J. Clean. Prod. 228, 376–387. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.286

Bin, L. I., Yuan, Q. I., and Qian, L. I. (2016). Fiscal Decentralization, FDI and Green Total Factor Productivity——A Empirical Test Based on Panel Data Dynamic GMM Method. J. Int. Trade 7, 119–129. doi:10.13510/j.cnki.jit.2016.07.011

Bowsher, C. G. (2002). On testing overidentifying restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Econ. Lett. 77 (2), 211–220. doi:10.1016/s0165-1765(02)00130-1

Cai, H., and Treisman, D. (2004). State corroding federalism. J. Public Econ. 88, 819–843. doi:10.1016/s0047-2727(02)00220-7

Can, M., Ahmad, M., and Khan, Z. (2021a). The impact of export composition on environment and energy demand: evidence from newly industrialized countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 1–14. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-13084-5

Can, M., Ahmed, Z., Mercan, M., and Kalugina, O. A. (2021b). The role of trading environment-friendly goods in environmental sustainability: Does green openness matter for OECD countries? J. Environ. Manage. 295, 113038. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113038

Canavire-Bacarreza, G., Martinez-Vazquez, J., and Yedgenov, B. (2019). Identifying and disentangling the impact of fiscal decentralization on economic growth. World Develop. 127, 104742. doi:10.18235/0001899

Chen, X., and Huang, B. (2016). Club membership and transboundary pollution: Evidence from the European Union enlargement. Energ. Econ. 53, 230–237. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2014.06.021

Cheng, Z., and Jin, W. (2020). Agglomeration economy and the growth of green total-factor productivity in Chinese Industry. Socio-Economic Plann. Sci. 2020, 101003. doi:10.1016/j.seps.2020.101003

Chirinko, R. S., and Wilson, D. J. (2017). Tax Competition Among U.S. States: Racing to the Bottom or Riding on a Seesaw? J. Public Econ. 155, 147–163. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.10.001

Cumberland, J. H. (1980). Efficiency and Equity in Interregional Environmental Management. Rev. Reg. Stud. 10 (2), 1–9. doi:10.52324/001c.9944

Deng, Y. P., and Xu, H. L. (2013). Foreign Direct Investment, Local Government Competition and Environmental Pollution - An Empirical Study Based on Fiscal Decentralization Perspective. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 7, 155–163.

Ding, Y., McQuoid, A., and Karayalcin, C. (2019). Fiscal decentralization, fiscal reform, and economic growth in china. China Econ. Rev. 53, 152–167. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2018.08.005

Dinh Thanh, S., Hart, N., and Canh, N. P. (2020). Public spending, public governance and economic growth at the Vietnamese provincial level: A disaggregate analysis. Econ. Syst. 44, 100780. doi:10.1016/j.ecosys.2020.100780

Duanmu, J.-L., Bu, M., and Pittman, R. (2018). Does Market Competition Dampen Environmental Performance? Evidence from China. Strat. Mgmt. J. 39 (11), 3006–3030. doi:10.1002/smj.2948

Duffee, G. R. (1996). Idiosyncratic Variation of Treasury Bill Yields. J. Finance 51 (2), 527–551. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1996.tb02693.x

Epifani, P., and Gancia, G. (2011). Trade, markup heterogeneity and misallocations. J. Int. Econ. 83 (1), 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2010.10.005

Fried, H. O., Lovell, C. K., Schmidt, S. S., and Yaisawarng, S. (2002). Accounting for environmental effects and statistical noise in data envelopment analysis. J. productivity Anal. 17 (1-2), 157–174. doi:10.1023/a:1013548723393

Glazer, A. (1999). Local regulation may be excessively stringent. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 29 (5), 553–558. doi:10.1016/s0166-0462(99)90013-3

Guang-Bin, L. (2005). Government competition: an analysis of local government behaviors of administrative economy. Urban Probl.

Guesmi, K., Moisseron, J.-Y., and Teulon, F. (2014). Integration versus segmentation in Middle East North Africa Equity Market: Time variations and currency risk. J. Int. Financial Markets, Institutions Money 28, 204–212. doi:10.1016/j.intfin.2013.10.005

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tahtam, R. L., and Balck, V. C. (1995). Multivarite Data Analysis with Reading. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. International Inc, A Viacorn Company.

Hao, Y., Guo, Y., Guo, Y., Wu, H., and Ren, S. (2020). Does outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) affect the home country's environmental quality? The case of China. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 52, 109–119. doi:10.1016/j.strueco.2019.08.012

Hatfield, J. W., and Kosec, K. (2013). Federal competition and economic growth. J. Public Econ. 97, 144–159. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.08.005

Haufler, A., and Maier, U. (2019). Regulatory competition in capital standards: a 'race to the top' result. J. Banking Finance 106, 180–194. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2019.06.001

Hong, Y., Lyu, X., Chen, Y., and Li, W. (2020). Industrial agglomeration externalities, local governments' competition and environmental pollution: Evidence from Chinese prefecture-level cities. J. Clean. Prod. 277, 123455. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123455

Hou, S., and Song, L. (2021). Market Integration and Regional Green Total Factor Productivity: Evidence from China's Province-Level Data. Sustainability 13 (2), 472. doi:10.3390/su13020472

Hsieh, C.-T., and Klenow, P. J. (2009). Misallocation and Manufacturing TFP in China and India*. Q. J. Econ. 124 (4), 1403–1448. doi:10.1162/qjec.2009.124.4.1403

Hubbard, T. P. (2014). Trade and transboundary pollution: quantifying the effects of trade liberalization on CO2emissions. Appl. Econ. 46 (5), 483–502. doi:10.1080/00036846.2013.857000

Iacobucci, D. (2012). Mediation analysis and categorical variables: The final frontier. J. Consumer Psychol. 22 (4), 582–594. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2012.03.006

Iqbal, N., and Daly, V. (2014). Rent seeking opportunities and economic growth in transitional economies. Econ. Model. 37, 16–22. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2013.10.025

Jiang, W., Rosati, F., Chai, H., and Feng, T. (2020). Market orientation practices enhancing corporate environmental performance via knowledge creation: Does environmental management system implementation matter? Bus Strat Env 29 (5), 1899–1924. doi:10.1002/bse.2478

Jin, G., Shen, K., and Li, J. (2020). Interjurisdiction political competition and green total factor productivity in China: An inverted-U relationship. China Econ. Rev. 61, 101224. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2018.09.005

Jondrow, J., Lovell, C. K., Materov, I. S., and Schmidt, P. (1982). On the estimation of technical inefficiency in the stochastic frontier production function model. J. Econom. 19 (2-3), 233–238. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(82)90004-5

Ke, S. (2015). Domestic Market Integration and Regional Economic Growth-China's Recent Experience from 1995-2011. World Develop. 66 (66), 588–597. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.09.024

Keen, M., and Marchand, M. (1997). Fiscal competition and the pattern of public spending. J. Public Econ. 66 (1), 33–53. doi:10.1016/s0047-2727(97)00035-2

Kim, Y. K., Lee, K., Park, W. G., and Choo, K. (2012). Appropriate intellectual property protection and economic growth in countries at different levels of development. Res. Pol. 41 (2), 358–375. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.09.003

Kuai, P., Yang, S., Tao, A., Zhang, S. a., and Khan, Z. D. (2019). Environmental effects of Chinese-style fiscal decentralization and the sustainability implications. J. Clean. Prod. 239, 118089. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118089

Lai, A., Yang, Z., and Cui, L. (2021). Market segmentation impact on industrial transformation: evidence for environmental protection in china. J. Clean. Prod. 297 (2), 126607. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126607

Levinson, A. (2003). Environmental Regulatory Competition: A Status Report and Some New Evidence. Natl. Tax J. 56 (1), 91–106. doi:10.17310/ntj.2003.1.06

Li, H., Zhang, M., Li, C., and Li, M. (2019). Study on the spatial correlation structure and synergistic governance development of the haze emission in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26 (12), 12136–12149. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-04682-5

Li, J., and Lin, B. (2017). Does energy and CO2 emissions performance of China benefit from regional integration? Energy Policy 101, 366–378. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2016.10.036

Li, J., Qiu, L. D., and Sun, Q. (2003). Interregional protection: Implications of fiscal decentralization and trade liberalization. China Econ. Rev. 14 (3), 227–245. doi:10.1016/s1043-951x(03)00024-5

Li, P. (2015). Is there An inverted U-shaped curve relationship between industrial restructuring and environmental pollution? Inq. into Econ. Issues 12, 56–67.

Lin, X., Zhao, Y., Ahmad, M., Ahmed, Z., Rjoub, H., and Adebayo, T. S. (2021). Linking Innovative Human Capital, Economic Growth, and CO2 Emissions: An Empirical Study Based on Chinese Provincial Panel Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (16), 8503. doi:10.3390/ijerph18168503

List, J. A., and Gerking, S. (2000). Regulatory Federalism and Environmental Protection in the United States. J. Reg. Sci. 40 (3), 453–471. doi:10.1111/0022-4146.00183

Lu, L., Zhang, J., Yang, F., and Zhang, Y. (2020). Evaluation and prediction on total factor productivity of Chinese petroleum companies via three-stage DEA model and time series neural network model. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 27, 100397. doi:10.1016/j.suscom.2020.100397

McNabb, R., and Whitfield, K. (1998). Testing for segmentation: an establishment-level analysis. Cambridge J. Econ. 22 (3), 347–365. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.cje.a013720

Miao, X., Wang, T., and Gao, Y. (2017). The impact of transfer payments on the gap in public services between urban and rural areas—a group comparison of different economic catch-up provinces. Econ. Res. 52 (02), 52–66. (in Chinese).

Naughton, B. (1999). “How much can regional integration Do to unify China’s markets?,” in Paper presented for the Conference for Research on Economic Development and Policy Research. Working Paper Stanford University, 18–20.

Oates, W. E. (1999). An Essay on Fiscal Federalism. J. Econ. Lit. 37 (3), 1120–1149. doi:10.1257/jel.37.3.1120

Oates, W. E., and Portney, P. R. (2003). The political economy of environmental policy. Handbook Environ. Econ. 1, 325–354. doi:10.1016/s1574-0099(03)01013-1

Ouyang, X., Zhuang, W., and Sun, C. (2019). Haze, health, and income: An integrated model for willingness to pay for haze mitigation in Shanghai, China. Energ. Econ. 84, 104535. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2019.104535

Pan, X., Li, M., Guo, S., and Pu, C. (2020). Research on the competitive effect of local government's environmental expenditure in China. Sci. Total Environ. 718, 137238. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137238

Poncet, S. (2003). Measuring Chinese domestic and international integration. China Econ. Rev. 14 (1), 1–21. doi:10.1016/s1043-951x(02)00083-4

Qian, Y., and Weingast, B. R. (1997). Federalism as a Commitment to Preserving Market Incentives. J. Econ. Perspect. 11 (4), 83–92. doi:10.1257/jep.11.4.83

Qin, Q., Jiao, Y., Gan, X., and Liu, Y. (2020). Environmental efficiency and market segmentation: An empirical analysis of China's thermal power industry. J. Clean. Prod. 242, 118560. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118560

Qingwang, G., and Junxue, J. (2009). The Tactical Interaction among Local Governments, their Competition in fiscal Expenditure, and Regional Economic Growth [J]. Manage. World 10. doi:10.19744/j.cnki.11-1235/f.2009.10.004

Shao, S., Chen, Y., Li, K., and Yang, L. (2019). Market segmentation and urban CO2 emissions in China: Evidence from the Yangtze River Delta region. J. Environ. Manage. 248, 109324. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109324

Shyu, J., and Chiang, T. (2012). Measuring the true managerial efficiency of bank branches in Taiwan: A three-stage DEA analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 39 (13), 11494–11502. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2012.04.005

Simar, L., and Wilson, P. W. (2007). Estimation and inference in two-stage, semi-parametric models of production processes. J. Econom. 136 (1), 31–64. doi:10.1016/j.jeconom.2005.07.009

Song, M., Du, J., and Tan, K. H. (2018). Impact of Fiscal Decentralization on Green Total Factor Productivity. Internat. J. Product. Econ. 205, 359–367.

Su, X., Yang, X., Zhang, J., Yan, J., Zhao, J., Shen, J., et al. (2021). Analysis of the Impacts of Economic Growth Targets and Marketization on Energy Efficiency: Evidence from China. Sustainability 13 (8), 4393. doi:10.3390/su13084393

Sun, C., Ouyang, X., Cai, H., Luo, Z., and Li, A. (2014). Household pathway selection of energy consumption during urbanization process in China. Energ. Convers. Manage. 84, 295–304. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2014.04.038

Sun, C., Zhan, Y., and Du, G. (2020). Can value-added tax incentives of new energy industry increase firm's profitability? Evidence from financial data of China's listed companies. Energ. Econ. 86, 104654. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2019.104654

Sun, H., Edziah, B. K., Sun, C., and Kporsu, A. K. (2019). Institutional quality, green innovation and energy efficiency. Energy policy 135, 111002. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111002

Sun, X., Zhou, X., Chen, Z., and Yang, Y. (2020). Environmental efficiency of electric power industry, market segmentation and technological innovation: Empirical evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 706, 135749. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135749

Tang, Z. J., Liu, Y. J., and Chen, Y. (2011). A Study of Local Government Competition, Investment Impulse and China's Macroeconomic Fluctuation [J]. Contemp. Finance Econ. 8.

Thanh, S. D., and Nguyen, C. P. (2021). Local government capacity and total factor productivity growth: evidence from an Asian emerging economy. J. Asia Pac. Economy, 1–31. doi:10.1080/13547860.2021.1942412

van der Kamp, D., Lorentzen, P., and Mattingly, D. (2017). Racing to the bottom or to the top? Decentralization, revenue pressures, and governance reform in China. World Develop. 95, 164–176. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.02.021

Wang, J., Wang, W., Ran, Q., Irfan, M., Ren, S., Yang, X., et al. (2021). Analysis of the mechanism of the impact of internet development on green economic growth: evidence from 269 prefecture cities in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 1–15. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-16381-1

Wang, X., Wang, L., Wang, S., Fan, F., and Ye, X. (2021). Marketisation as a channel of international technology diffusion and green total factor productivity: research on the spillover effect from China's first-tier cities. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manage. 33 (5), 491–504. doi:10.1080/09537325.2020.1821877

Weitzman, M. L. (1989). A Theory of Wage Dispersion and Job Market Segmentation. Q. J. Econ. 104 (1), 121–137. doi:10.2307/2937837

Wu, H., Hao, Y., Ren, S., Yang, X., and Xie, G. (2021). Does internet development improve green total factor energy efficiency? Evidence from China. Energy Policy 153, 112247. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112247

Wu, H., Li, Y., Hao, Y., Ren, S., and Zhang, P. (2020a). Environmental decentralization, local government competition, and regional green development: Evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 708, 135085. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135085

Wu, H., Ren, S., Yan, G., and Hao, Y. (2020b). Does China's outward direct investment improve green total factor productivity in the "Belt and Road" countries? Evidence from dynamic threshold panel model analysis. J. Environ. Manage. 275, 111295. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111295

Yan, W. J. (2012). Fiscal Decentralization, Government Competition and Investment in Environmental Governance. Finance Trade Res. 5, 91–97. doi:10.19337/j.cnki.34-1093/f.2012.05.013

Yan, Y., Tao, L. I. U., and Joyce, M. A. N. (2013). Local Government Land Competition and Urban Economic Growth in China. Urban Develop. 3, 15.

Yang, X., Wu, H., Ren, S., Ran, Q., and Zhang, J. (2021b). “Does the development of the internet contribute to air pollution control in China?.” in Mechanism discussion and empirical test. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 56, 207–224.

Yang, X., Zhang, J., Ren, S., and Ran, Q. (2021a). Can the New Energy Demonstration City policy reduce environmental pollution? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. J. Clean. Prod. 287, 125015. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125015

Ye, N., and Zhang, B. (2017). Local protection, Ownership difference and Enterprise market Expansion options. World Economy (6), 98–119. (in Chinese).

Young, A. (2000). The razor's edge: Distortions and incremental reform in the People's Republic of China. Q. J. Econ. 115 (4), 1091–1135. doi:10.1162/003355300555024

Yushkov, A. (2015). Fiscal decentralization and regional economic growth: Theory, empirics, and the Russian experience. Russ. J. Econ. 1 (4), 404–418. doi:10.1016/j.ruje.2016.02.004

Yılmaz, E. (2013). Competition, taxation and economic growth. Econ. Model. 35, 134–139. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2013.06.040

Zhang, C., Liu, Q., Ge, G., Hao, Y., and Hao, H. (2020). The impact of government intervention on corporate environmental performance: Evidence from China’s national civilized city award. Finance Res. Lett. 39, 101624. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2020.101624

Zhang, J., Wu, G., and Zhang, J. (2004). China's inter-provincial material capital stock estimation: 1952-2000. Econ. Res. (10), 35–44. (in Chinese).

Zhang, J., Wang, J., Yang, X., Ren, S., Ran, Q., and Hao, Y. (2021). Does local government competition aggravate haze pollution? A new perspective of factor market distortion. Socio-Economic Plann. Sci. 76, 100959. doi:10.1016/j.seps.2020.100959

Zhang, W., Ren, C., and Hu, R. (2019). Empirical Research on the Impact of Chinese-style local government competition on environmental pollution. Macroeconomic Res. (02), 133–142. (in Chinese). doi:10.16304/j.cnki.11-3952/f.2019.02.011

Keywords: local government competition, market segmentation, green total factor productivity, mediation effect, China

Citation: Tang J and Qin F (2021) Analyzing the Effect of Local Government Competition on Green Total Factor Productivity From the Market Segmentation Perspective in China—Evidence From a Three-Stage DEA Model. Front. Environ. Sci. 9:763945. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2021.763945

Received: 24 August 2021; Accepted: 28 September 2021;

Published: 26 October 2021.

Edited by:

Muhlis Can, BETA Akademi-SSR Lab, TurkeyReviewed by:

Zahoor Ahmed, Beijing Institute of Technology, ChinaMahmood Ahmad, Shandong University of Technology, China

Mohamed R. Abonazel, Cairo University, Egypt

Copyright © 2021 Tang and Qin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fangming Qin, cWluZm14amVkdUAxNjMuY29t

Juan Tang

Juan Tang Fangming Qin

Fangming Qin