- 1Department of Geography, Environment, and Spatial Sciences, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 2Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior Program, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 3Department of Integrative Biology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 4National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center, Annapolis, MD, United States

- 5Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 6California Department of Water Resources, West Sacramento, CA, United States

- 7Geospatial Technology and Applications Center, United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Salt Lake City, UT, United States

- 8Lyman Briggs College, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

Global declines in biodiversity have the potential to affect ecosystem function, and vice versa, in both terrestrial and aquatic ecological realms. While many studies have considered biodiversity-ecosystem function (BEF) relationships at local scales within single realms, there is a critical need for more studies examining BEF linkages among ecological realms, across scales, and across trophic levels. We present a framework linking abiotic attributes, productivity, and biodiversity across terrestrial and inland aquatic realms. We review examples of the major ways that BEF linkages form across realms–cross-system subsidies, ecosystem engineering, and hydrology. We then formulate testable hypotheses about the relative strength of these connections across spatial scales, realms, and trophic levels. While some studies have addressed these hypotheses individually, to holistically understand and predict the impact of biodiversity loss on ecosystem function, researchers need to move beyond local and simplified systems and explicitly investigate cross-realm and trophic interactions and large-scale patterns and processes. Recent advances in computational power, data synthesis, and geographic information science can facilitate studies spanning multiple ecological realms that will lead to a more comprehensive understanding of BEF connections.

Introduction

Rapid global change, including spread of exotic species, land use intensification, and climate change, is altering biodiversity and endangering its vital ecosystem functions (Cardinale et al., 2012; Hooper et al., 2012; Suurkuukka et al., 2014; Martay et al., 2016; Vellend et al., 2017). Declines in biodiversity, changes in species ranges and populations, and phenological shifts have been documented across ecosystems (Dudgeon et al., 2006; Parmesan 2006) and are expected to intensify in the future (Urban 2015). Such changes can result in detrimental effects on essential functions (Cardinale et al., 2012), including nutrient cycling (McIntyre et al., 2007), food resources (Allan et al., 2005), carbon sequestration (Bunker et al., 2005; Tilman et al., 2006), and primary production (Hooper et al., 2012).

To identify potential shifts in ecosystem functions, a major focus for biodiversity conservation and management has been to delineate hotspots (highs) and coldspots (lows) of biodiversity change (Myers et al., 2000; Mokany et al., 2020). These maps and their underlying models, when used for explanation or prediction, are essential tools for biodiversity conservation, natural resource management, and policymaking. Recent calls have been made to preserve global ecosystem function by protecting half of the biosphere (Dinerstein et al., 2017), yet the question remains: which half?

Prioritizing areas for conservation requires an understanding of biodiversity-ecosystem functioning (BEF) linkages across diverse systems. Yet, the effects of changes in biodiversity on ecosystem functioning, and vice versa, are likely under- and incorrectly estimated because BEF linkages among ecological realms (i.e., terrestrial, inland aquatic, or marine) are rarely considered (Soininen et al., 2015; Gonzalez et al., 2020; Hermoso et al., 2021). BEF studies have, since the concept’s origin, been focused on primary producers (e.g., Tilman et al., 1997) or on trophic interactions within a single ecological realm (e.g., Schindler et al., 1997; Lecerf and Richardson 2010). Since those early studies, most biodiversity forecasts have been performed within a single realm and/or ignored species interactions, especially interactions across trophic levels (Record et al., 2018; Figure 1). Moreover, biodiversity and habitat in freshwater systems are much less frequently assessed than in terrestrial or marine systems, despite the higher proportion of threatened and endangered species (Revenga et al., 2005). For example, a recent effort at mapping biodiversity conservation priority areas (Mokany et al., 2020) only includes water as an indicator of anthropogenic pressure, not an indicator of biodiversity. If most models predicting changes to BEF are within a single ecological realm, and ignore likely interactions, feedbacks, and synergies between terrestrial, inland aquatic, and marine realms and across trophic levels, then predictions of biodiversity status and conservation prioritization may be incomplete, unreliable, or uncertain.

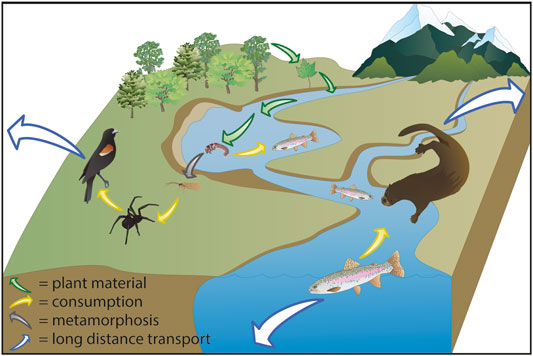

FIGURE 1. Simplified example of terrestrial and inland aquatic connections between biodiversity and ecosystem functioning (BEF) via subsidies. Diverse, productive forests deliver diverse suites of nutrients into streams. Terrestrial plant material is fed upon by aquatic primary consumers like the caddisfly (Order Trichoptera) larva shown here (Cummins et al., 1989). When these larvae complete their life cycles, they emerge from the aquatic to the terrestrial environment, providing food for terrestrial invertebrates like a spider (Order Araneae) (Sanzone et al., 2003), which is a primary food source for red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus). Mobile terrestrial consumers, such as birds, may then transport aquatic nutrients over long distances (Baxter et al., 2005). The larvae may also be consumed by other aquatic organisms like rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). The fish might either be eaten by a river otter (Lontra canadensis), which then transports and deposits nutrients some distance from the stream (Crait and Ben-David 2007), or the fish carry the nutrients downstream, to other watersheds or ecosystems. Symbols for diagram courtesy of the Integration and Application Network (ian.umces.edu/media-library).

We address these challenges by presenting: 1) a conceptual framework for BEF connections between terrestrial and inland aquatic ecological realms; 2) a brief review of the evidence for strong BEF connections between terrestrial and inland aquatic realms; 3) predictions about relationships between terrestrial and inland aquatic realms across spatial scales and trophic levels; and 4) future cross-realm BEF research approaches and needs. Throughout, we refer to “ecological realms” to emphasize the conceptual boundaries between these subfields of ecology. We use terms like “ecosystem” or “landscape” when referring to specific studies with discrete geographic boundaries. We focus on terrestrial and inland aquatic realms; however, we would expect marine and terrestrial realms to have similar connections (e.g., Polis and Hurd 1995; Marczak et al., 2007; Zarnetske et al., 2012) and also for there to be important three-way BEF connections among marine, terrestrial, and inland aquatic realms (e.g., Gende et al., 2002).

A Conceptual Framework for Cross-Realm Biodiversity-Ecosystem Function Connections

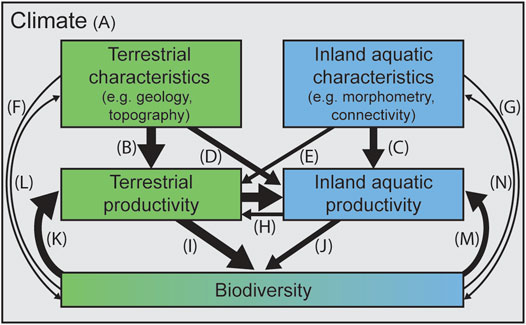

At the macroscale (i.e., regional-continental, long-term), the physical characteristics of a landscape and its productivity and biodiversity are predominantly controlled by climate (Lieth and Whittaker 1975; Lomolino et al., 2010; Collins et al., 2019) (Figure 2A). In the terrestrial realm, after climate, productivity is controlled by landscape characteristics like hydrology, available nutrients, and topographic position (Roy et al., 2001) (Figure 2B). Similarly, in the inland aquatic realm, productivity is controlled not only by connectivity to the broader hydrologic system, and nutrient and light availability, but also by the size, shape, and depth of the water body (morphometry) (Odum 1956; Dillon and Rigler 1974; Vannote et al., 1980; Carpenter et al., 1985) (Figure 2C).

FIGURE 2. Conceptual framework of BEF connections across terrestrial-aquatic realms. Abiotic attributes of terrestrial and inland aquatic systems can directly affect that system’s productivity and in turn biodiversity. Arrows are referenced in the text (A–N). In many cases, arrows could be drawn in other directions; here we highlight likely important directional relationships.

Inland aquatic and terrestrial environments do not exist in isolation; the abiotic environment in the surrounding watershed will impact the productivity of a water body (Likens 1975; Allan 2004) (Figure 2D), and in certain cases the abiotic conditions of a water body have been shown to affect the productivity of the surrounding terrestrial landscape [e.g., floodplains (Junk et al., 1989; Bayley 1995)] (Figure 2E). The abiotic characteristics of terrestrial and inland aquatic landscapes are also known to influence biodiversity directly (Wallace et al., 1997; Dahlin et al., 2013; Kärnä et al., 2019) (Figures 2F,G). Productivity is often correlated across terrestrial and aquatic realms, with highly productive terrestrial systems adjacent to productive aquatic systems (Wallace et al., 1997; Ballinger and Lake 2006; Gratton et al., 2017) (Figure 2H). Terrestrial and aquatic productivity may directly and indirectly influence both terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity; more productive terrestrial environments tend to have higher biodiversity (Liang et al., 2016) (Figure 2I) as do more productive inland aquatic environments (Dodson et al., 2000; Bartrons et al., 2013) (Figure 2J). Terrestrial biodiversity and species composition can also affect terrestrial productivity and decomposition (Hooper et al., 2012) (Figure 2K), and even physical attributes (e.g., via root exudates; (Eisenhauer et al., 2017), and ecosystem engineers [McCaffery and Eby 2016)] (Figure 2L). Biodiversity feeds back to aquatic productivity (Wallace et al., 1997) (Figure 2M), and in some cases biodiversity can impact the physical attributes of aquatic systems (Jones et al., 1994) (Figure 2N). This web of direct and indirect relationships between abiotic factors, productivity, and biodiversity highlights the need for more research especially on linkages between biodiversity and the abiotic environment (Figures 2L,N) and in inland aquatic ecosystems’ influence on their surrounding landscapes (Figures 2H,J).

Much of the research on terrestrial and aquatic linkages has focused on systems heavily impacted by human influences like increased nutrients (Lefcheck et al., 2018) or invasive species introductions (Twardochleb et al., 2013). While it is critical to quantify the extent of human influence on terrestrial-aquatic connections, human impacts will alter cross-realm relationships in inconsistent ways (Edvardsen and Økland 2006; Kautza and Sullivan 2015), especially as conservation efforts are put in place. For example, Moore and Palmer (2005) showed, in Maryland, United States, that although agricultural streams had high macroinvertebrate diversity, impervious surfaces reduced taxon richness. Therefore, although the framework and questions described here can be applied to human-impacted systems affected by pressures like paving, large scale landform alteration, and synthetic fertilizers, our focus is on systems that have been minimally impacted by modern anthropogenic pressures.

Evidence for Biodiversity-Ecosystem Function Connections Across Realms

Current knowledge of the physical, chemical, and biological linkages between terrestrial and inland aquatic realms derives primarily from three research areas: cross-ecosystem subsidies, ecosystem engineering, and hydrologic connections. Together, results from these research areas suggest that connections between BEF commonly occur between terrestrial and inland aquatic systems and are thus important to quantify to understand future global change impacts on BEF relationships. Here we summarize the current evidence for these linkages and build on this knowledge to establish our theoretical framework and testable hypotheses for future BEF research linking terrestrial and inland aquatic ecological realms. This is not intended to be a comprehensive review, and so references are provided as examples, not exhaustive lists.

Cross-Ecosystem Subsidies

Cross-ecosystem subsidies have been a major focus of food web ecology for decades (Marczak et al., 2007; Allen and Wesner 2016) and much of this work has been linked to the meta-ecosystem concept (Loreau et al., 2003b). Terrestrial-aquatic connections provide resource subsidies that support higher growth rates (Sabo and Power 2002), abundances (Sanpera-Calbet et al., 2009; Allen and Wesner 2016), and niche diversity of consumers (Darimont et al., 2009) in adjacent ecosystems. Subsidies of terrestrial invertebrates to streams provide up to half of the annual energy budget to fishes such as salmonids, and emergence of adult aquatic insects comprises between 25 and 100% of the energy budget to nearby terrestrial bird, bat, lizard, and spider populations (Baxter et al., 2004; Baxter et al., 2005; Gratton and Vander Zanden 2009). Although aquatic ecosystems generally receive relatively large quantities of low-quality organic matter subsidies from terrestrial ecosystems (e.g., leaves), and terrestrial ecosystems receive relatively small quantities of high-quality subsidies from aquatic ecosystems (e.g., guano and insects), consumers rely on these subsidies to a comparable extent in both realms (up to 40% of the diet in each) (Soininen et al., 2015), but see Hagar et al. (2012).

Terrestrial-aquatic subsidy impacts can have large spatial extents. Signatures of subsidies to terrestrial environments have been shown to extend up to 5,300 m laterally from stream banks and nearly 1,000 m from lakeshores (Muehlbauer et al., 2014). Bats, for example, consume large quantities of emergent aquatic insects and deposit guano several kilometers away, increasing nutrient concentrations near roosts (Power et al., 2004). Subsidies from one ecosystem may promote biodiversity in an adjacent ecosystem both directly by increasing the spatial and temporal availability of prey to consumers (Schindler et al., 2013), and indirectly by alleviating predation pressure on prey in adjacent ecosystems (Sabo and Power 2002).

Positive relationships have been shown in studies that have quantified cross-realm BEF relationships by linking terrestrial primary production and inland aquatic biodiversity. Controlled mesocosm experiments have revealed complex relationships between terrestrial leaf and insect subsidies and the biodiversity of aquatic systems (Klemmer et al., 2020). At landscape and regional scales, richness of stream insects (Vinson and Hawkins 2003) and plankton diversity (Soininen and Luoto 2012) was positively correlated with watershed Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), a measure of terrestrial greenness and productivity. Catchment terrestrial primary production explained significant variation in geographic distributions of anadromous arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus), suggesting that aquatic animals track the spatial availability of terrestrial primary production (Finstad and Hein 2012). Such studies have prompted some aquatic ecologists to advocate using measures of terrestrial primary production to predict broad-scale patterns of aquatic biodiversity (Soininen et al., 2015).

Despite the importance of cross-realm subsidies, studies of subsidy-biodiversity relationships tend to be unidirectional. Little research has documented the reciprocal subsidies (Figures 2I,J) that reflect the true web structure of these relationships (but see Klemmer et al., 2020). BEF research predicts that strong richness-productivity relationships in one system should strengthen the association between richness and productivity in adjacent systems by reducing spatial and temporal variance around the richness-productivity correlation (Loreau et al., 2003a). For example, increased mussel species richness in streams reduces the temporal variance in insect emergence (Allen et al., 2012), and increased soil microbial biodiversity may stabilize hydrological pathways of material transfer from terrestrial to aquatic systems (Bardgett et al., 2001). Although these studies show that terrestrial or aquatic BEF may spill over to adjacent systems, we are not aware of a single study that demonstrates a direct mechanistic connection between terrestrial BEF and aquatic BEF. Therefore, the current understanding of cross-ecosystem subsidies is likely underestimating the strength and importance of cross-realm BEF relationships, which could impact environmental conservation prioritization decisions within and across realms.

Ecosystem Engineering

Physical alterations of landscapes by organisms can significantly influence the connections between terrestrial and inland aquatic systems. The effects of these “ecosystem engineers” (Jones et al., 1994) often span ecological realms (Hastings et al., 2007). Beavers (Castor spp.), for example, influence the riparian density, biomass, and species composition (Johnston and Naiman 1990; Wright et al., 2002) as well as the hydrologic profile of freshwater systems. Beaver dams, in turn, increase the diversity of aquatic invertebrates important for terrestrial consumers (McCaffery and Eby 2016) and increase the supply of terrestrially derived organic matter in streams (Anderson and Rosemond 2010). Beaver dams elevate soil moisture and nitrogen levels (Naiman et al., 1994) that, along with beaver herbivory, affect forest succession and increase terrestrial and wetland plant species diversity. Hippopotami (Hippopotamus amphibius) create new river channels which redistribute nutrients, enhance productivity, and facilitate the movement of fish populations (Mosepele et al., 2009); they also transport terrestrial carbon and nutrients to aquatic systems (Subalusky et al., 2015).

Physical modification by sediment-binding plants also influences both aquatic and terrestrial systems. The abiotic environment influences dune grass growth, which in turn affects dune shapes (Zarnetske et al., 2012; Emery and Rudgers 2014); the resulting dune geomorphology and dune plant community influence the dune hydrological regime including ponds and wetlands in dune slack areas (Grootjans et al., 1998). A wide range of ecosystem engineers affect both terrestrial and inland aquatic realms, illustrating the potential for strong BEF connections through direct physical alteration of the landscape.

Hydrology Connects Biodiversity-Ecosystem Function Across Realms

Strong hydrologic connections among terrestrial and inland aquatic realms exist in both river floodplains and dryland ecosystems. In the evolution of river floodplains terrestrial vegetation diversifies inland aquatic habitats, providing a range of colonization options for different organisms (Ward et al., 2002). This example suggests that terrestrial primary production and plant species diversity may promote inland aquatic biodiversity by increasing habitat heterogeneity, improving forage quality and variety, and supporting more diverse assemblages of organisms. Research in dryland ecosystems shows that low-productivity systems with high levels of salinity in both water and soil have negative effects on biodiversity. Increased levels of salinity in eastern Australia, for example, caused riparian trees to die, which caused aquatic salinity levels to rise, in return causing further tree death (Briggs and Taws 2003). Increases in salinity can also decrease the diversity of aquatic invertebrates, riparian and aquatic vegetation, microalgae, and fish (Hart et al., 2003). As aquatic invertebrates and fish are important predators of mosquitoes, a reduction in predation along with more mosquito breeding habitat from salinity-induced rising water tables can increase mosquito-borne virus transmission to humans (Jardine et al., 2007). Given the dominant role that hydrology plays in both terrestrial and aquatic realms, there are likely many other examples of hydrological connections influencing BEF relationships, though studies do not often use the BEF framework (e.g., Kneitel and Lessin 2010; Vander Zanden and Gratton 2011; Stahlschmidt et al., 2012; Schriever et al., 2014).

How Spatial Scale and Trophic Level Affect Biodiversity-Ecosystem Function Connections Across Realms

Spatial Scales and Biodiversity-Ecosystem Function Relationships Across Realms

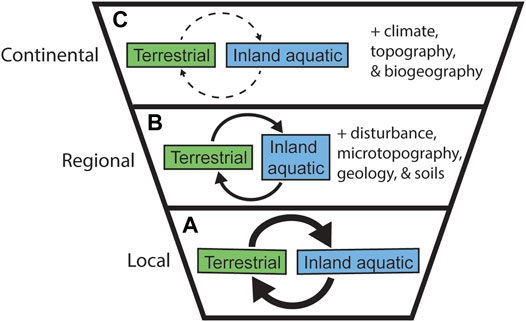

The relative importance of processes that impact BEF relationships across realms is likely to differ across scales, as has been demonstrated in single-realm studies (e.g., Thompson et al., 2018). We present hypotheses about how terrestrial and inland aquatic linkages may change across spatial scales of analysis (Figure 3). Similar hypotheses could be developed to consider connections across temporal scales; however, temporal scaling is beyond the scope of this paper. At fine grains and local extents, we expect strong connections between terrestrial and inland aquatic systems—the condition of an individual lake matters to the watershed that drains into it, and a watershed has direct impacts on the water bodies it feeds (Jackrel and Wootton 2014) (Figure 3A). Gratton and Vander Zanden (2009), for example, estimated that fluxes of aquatic insects to the surrounding terrestrial ecosystems would move a maximum of 300 m inland from a lake shore. At intermediate grains and regional extents greater variability in environmental conditions should result in weaker or noisier terrestrial-aquatic connections. For example, Sabo and Hagen (2012) found that within river networks, the strength of connection between a river and its surrounding watershed was highly dependent on the morphometry of the river network. Some watersheds may be highly connected, whereas others are less connected, or connections are strong only at small extents (Sabo and Hagen 2012; McCullough et al., 2019) (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3. Expected variation in strength of relationships between terrestrial and inland aquatic realms across spatial scales (A–C). Arrow/line weight indicates expected strength, with thicker arrows suggesting stronger, more significant relationships.

At very coarse grains and broad extents, we expect to find the weakest relationships between terrestrial and inland aquatic realms (Figure 3C). Broad-scale heterogeneity in climate, landform, and biogeography, along with regional-scale processes such as land use/cover and glaciation, should add noise to or diminish the connections between aquatic and terrestrial biodiversity and productivity (Holland et al., 2011; Stachelek et al., 2020). Terrestrial and inland aquatic systems are likely to respond to these macroscale phenomena in different ways and at different rates.

Trophic Levels and Biodiversity-Ecosystem Function Relationships Across Realms

BEF studies often focus on a single trophic level, often primary producers. Since as little as 10% of the energy produced at a given trophic level is transferred to the next higher trophic level (Elser et al., 2000), we might expect BEF relationships across realms to weaken when higher trophic levels are considered. However, the question of whether food web controls are bottom-up (resource controlled) or top-down (consumption controlled) continues to be fundamental in ecological research across realms (Lynam et al., 2017; Vidal and Murphy 2018).

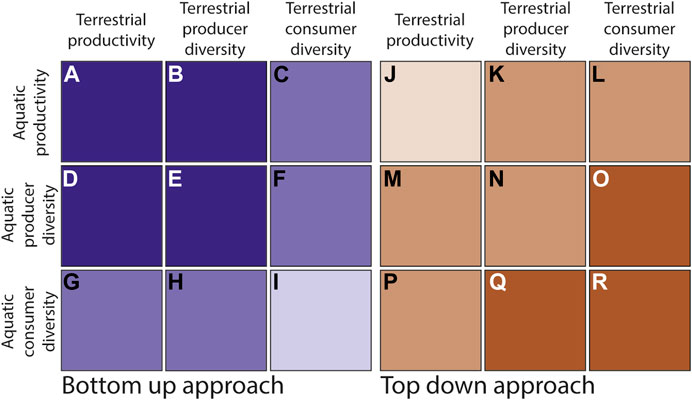

Taking a green-world, bottom up perspective (Polis 1999), we expect strong relationships between inland aquatic and terrestrial productivity. Because all productivity is generally controlled by the same suite of processes, regardless of system (Grimm et al., 2003), productivity between realms should be related (Figure 4A). Terrestrial productivity should also have a strong correlation with aquatic producer (autotroph) diversity (Figure 4D), and vice versa (Figure 4B)—more productive landscapes should have higher autotroph biodiversity regardless of realm. Similarly, aquatic producer diversity and terrestrial producer diversity (phytoplankton and plants) should follow similar biogeographic patterns and therefore be correlated (Edvardsen and Økland 2006; Suurkuukka et al., 2014; Stoler and Relyea 2016) (Figure 4E). We expect aquatic consumer (heterotroph) biodiversity to have a weaker but still positive correlation with terrestrial productivity (Dolný et al., 2013; Schriever et al., 2014; Kautza and Sullivan 2015) (Figure 4G), and aquatic productivity should be weakly correlated with terrestrial consumer biodiversity (Stahlschmidt et al., 2012; Sarneel et al., 2014) (Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4. BEF across trophic levels. Bottom up [(A–I), purple] and top down [(J–R), orange] hypotheses for the strength of relationships between productivity and biodiversity in terrestrial and aquatic systems at a single scale. Darker colors indicate stronger, more significant expected correlations, while lighter colors indicate weaker or non-significant hypothesized relationships. For example, taking a bottom-up approach we would expect weak correlations, if any, between terrestrial consumer diversity and aquatic consumer diversity (I) for a given grain and extent. In contrast, taking a top-down approach, we would expect a strong, significant correlation between these same two categories (R).

Moving from lower to higher trophic levels, from a bottom up perspective we expect organisms to be able to access resources from more food web compartments (e.g., Marczak et al., 2007) and so their biodiversity should be less closely tied to any individual source of productivity (Figures 4F,H). Finally, we expect connections between aquatic and terrestrial consumer biodiversity to exist (Purdy et al., 2012); however, due to food web complexities, from a bottom-up perspective we would expect these relationships to be weak (e.g., Corti and Datry 2016) or undetectable in some systems (Hagar et al., 2012; Tonkin et al., 2016) (Figure 4I). In the case of streams and rivers, these connections may further be complicated by the fact that water and nutrients are moving rapidly through the ecosystem; this could lead to spatial disconnects between terrestrial and aquatic productivity (Vannote et al., 1980).

While bottom up control of consumer diversity is important, it is also likely that top down control, the brown-world perspective (Bond 2005), is a major influence in at least some contexts and at some spatial scales (Borer et al., 2005). Terrestrial predators (high trophic level consumers) may regulate the diversity and abundance of aquatic prey, which in turn affects the diversity and abundance of aquatic primary producers (Nakano et al., 1999). In systems where top-down forces are important relative to bottom-up forces, an alternative set of hypotheses may be more realistic (Figure 4, right panel). From a top-down perspective, we would expect a stronger positive relationship between aquatic and terrestrial diversity at higher trophic levels, and there are examples of trophic cascades within higher trophic levels connecting terrestrial and aquatic consumers (e.g., Wesner 2012) (Figure 4R). Cross-realm trophic cascades may then impact relationships between consumer and producer diversity (Figures 4O,Q). Depending on the strength of these higher trophic level connections, this situation could lead to a decoupling of terrestrial and inland aquatic productivity (Gergs et al., 2014) (Figure 4J). In many systems, both top-down and bottom-up processes may operate simultaneously, and experimental approaches may be required to disentangle these processes. These examples demonstrate the importance of carefully considering spatial scales, complex life history strategies, and trophic levels when studying BEF connections across realms.

Discussion

Global environmental change can alter the degree and even presence of BEF connections, and so there is urgent need for cross-realm studies for predicting and forecasting their potential effects on the biosphere and human needs. We already know that global change is impacting cross-ecosystem subsidies, ecosystem engineering, and hydrology through agricultural pesticide applications (Relyea 2005), invasions by ecosystem engineers (Twardochleb et al., 2013), and dams and other water diversions (Nilsson et al., 2005). However, these global changes are not usually researched with cross-realm impacts in mind. There are also studies of BEF connections across terrestrial and aquatic realms, though they are not always posed in this framework (e.g., Klemmer et al., 2020). To better link cross-realm interactions with BEF theory, we proposed a conceptual framework to better document and understand these complex interactions across realms (Figure 2). We also proposed testable hypotheses related to spatial scales and trophic levels across realms (Figures 3, 4). Our proposed framework can help researchers better identify direct and indirect effects of global change on BEF relationships within and across ecological realms, spatial scales, and trophic levels.

We propose three major reasons for the dearth of studies that quantify BEF across terrestrial and aquatic realms: 1) data are rarely collected or compiled across realms, spatial scales, and trophic levels; 2) ecologists generally specialize by ecological realm and level of organization; and 3) statistical methods to understand complicated, layered interactions are often difficult to execute and interpret. Recent developments in ecology and environmental science can help address these three constraints. First, there is increased data availability of relatively fine-grain (tens of meters) measures of ecosystem and biotic properties across broad spatial extents (Zipkin et al., 2021), often obtained from remote sensing platforms in both terrestrial and aquatic realms (Jetz et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2020). Second, networks of ecologists working in different realms and in different geographic areas provide opportunities for cross-realm study. Networks, whether investigator-led, government-sponsored, or some combination, are becoming more common and often generate data products that allow such cross-realm analysis, such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF.1) and the United States National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON.2). Third, the emerging field of macrosystems ecology, with its foundations in landscape ecology, macroecology, and biogeography, is building tools and theory to advance understanding at broad-scales (Heffernan et al., 2014; Levy et al., 2014; Fei et al., 2016; Rose et al., 2017; Dodds et al., 2021; Tromboni et al., 2021). Fourth, ecologists and other scientists are becoming more collaborative and interdisciplinary (e.g., Wuchty et al., 2007), which can facilitate research across scales, realms, and trophic levels (Cheruvelil and Soranno 2018). Finally, new tools (and tools new to ecologists) are being developed (and adopted) to analyze complex interactions. As some examples, structural equation modeling enables researchers to explicitly consider the influence of community diversity and structure on the pools and fluxes of energy and matter within and across realms (e.g., Grace et al., 2016; Lefcheck et al., 2018), geostatistics can improve understanding of spatial data relationships (Lapierre et al., 2018), and Bayesian hierarchical modeling can connect observations across spatial and temporal scales (Soranno et al., 2019). Recent work has also emphasized the importance of taking a complex systems approach and using network models in cross-realm studies (Sullivan and Manning 2019). Moreover, the most recently released IUCN Global Ecosystem Typology (Keith et al., 2020) identifies “transitional realms”, which will also help draw attention to cross-realm connections. By working together across realms, scales, and trophic levels, terrestrial and aquatic ecologists and environmental scientists will better document existing linkages and uncover novel connections that are likely to develop in the face of continued global change.

Author Contributions

All authors: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—Final review. KD: Visualization, Writing—Reviewing and editing, Project administration.

Funding

This work was funded primarily by a Michigan State University Watercube award to KD, PZ, KC, and PS, which supported QR, LT, and AK. LT was also funded by NASA Earth and Space Science Fellowship Program−Grant 80NSSC17K0395. QR was also funded by United States National Science Foundation (NSF) award DBI-1639145. PS and KC were supported by the United States NSF Macrosystems Biology Program (EF-1638679). PZ was funded by USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), Hatch project 1010055. PS was supported by the USDA NIFA, Hatch project 1013544. KD was supported by the USDA NIFA, Hatch project 1025001.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

References

Allan, J. D. (2004). Influence of Land Use and Landscape Setting on the Ecological Status of Rivers. Limnetica 23, 187–198.

Allan, J. D., Abell, R., Hogan, Z., Revenga, C., Taylor, B. W., Welcomme, R. L., et al. (2005). Overfishing of Inland Waters. BioScience 55, 1041. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2005)055[1041:ooiw]2.0.co;2

Allen, D. C., and Wesner, J. S. (2016). Synthesis: Comparing Effects of Resource and Consumer Fluxes into Recipient Food Webs Using Meta-Analysis. Ecology 97, 594–604. doi:10.1890/15-1109.1

Allen, D. C., Allen, D. C., Vaughn, C. C., Kelly, J. F., Cooper, J. T., and Engel, M. H. (2012). Bottom-up Biodiversity Effects Increase Resource Subsidy Flux between Ecosystems. Ecology 93, 2165–2174. doi:10.1890/11-1541.1

Anderson, C. B., and Rosemond, A. D. (2010). Beaver Invasion Alters Terrestrial Subsidies to Subantarctic Stream Food Webs. Hydrobiologia 652, 349–361. doi:10.1007/s10750-010-0367-8

Ballinger, A., and Lake, P. S. (2006). Energy and Nutrient Fluxes from Rivers and Streams into Terrestrial Food Webs. Mar. Freshw. Res. 57, 15–28. doi:10.1071/mf05154

Bardgett, R. D., Anderson, J. M., Behan-Pelletier, V., Brussaard, L., Coleman, D. C., Ettema, C., et al. (2001). The Influence of Soil Biodiversity on Hydrological Pathways and the Transfer of Materials between Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecosystems. Ecosystems 4, 421–429. doi:10.1007/s10021-001-0020-5

Bartrons, M., Papeş, M., Diebel, M. W., Gratton, C., and Vander Zanden, M. J. (2013). Regional-Level Inputs of Emergent Aquatic Insects from Water to Land. Ecosystems 16, 1353–1363. doi:10.1007/s10021-013-9688-6

Baxter, C. V., Fausch, K. D., and Carl Saunders, W. (2005). Tangled Webs: Reciprocal Flows of Invertebrate Prey Link Streams and Riparian Zones. Freshw. Biol. 50, 201–220. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.2004.01328.x

Baxter, C. V., Fausch, K. D., Murakami, M., and Chapman, P. L. (2004). Fish Invasion Restructures Stream and Forest Food Webs by Interrupting Reciprocal Prey Subsidies. Ecology 85, 2656–2663. doi:10.1890/04-138

Bayley, P. B. (1995). Understanding Large River: Floodplain Ecosystems. BioScience 45, 153–158. doi:10.2307/1312554

Bond, W. J. (2005). Large Parts of the World Are Brown or Black: A Different View on the 'Green World' Hypothesis. J. Veg Sci. 16, 261–266. doi:10.1658/1100-9233(2005)016[0261:lpotwa]2.0.co;2

Borer, E. T., Seabloom, E. W., Shurin, J. B., Anderson, K. E., Blanchette, C. A., Broitman, B., et al. (2005). What Determines the Strength of a Trophic Cascade? Ecology 86, 528–537. doi:10.1890/03-0816

Briggs, S. V., and Taws, N. (2003). Impacts of Salinity on Biodiversity-clear Understanding or Muddy Confusion? Aust. J. Bot. 51, 609–617. doi:10.1071/bt02114

Bunker, D. E., DeClerck, F., Bradford, J. C., Colwell, R. K., Perfecto, I., Phillips, O. L., et al. (2005). Species Loss and Aboveground Carbon Storage in a Tropical Forest. Science 310, 1029–1031. doi:10.1126/science.1117682

Cardinale, B. J., Duffy, J. E., Gonzalez, A., Hooper, D. U., Perrings, C., Venail, P., et al. (2012). Biodiversity Loss and its Impact on Humanity. Nature 486, 59–67. doi:10.1038/nature11148

Carpenter, S. R., Kitchell, J. F., and Hodgson, J. R. (1985). Cascading Trophic Interactions and Lake Productivity. BioScience 35, 634–639. doi:10.2307/1309989

Cheruvelil, K. S., and Soranno, P. A. (2018). Data-Intensive Ecological Research Is Catalyzed by Open Science and Team Science. BioScience 68, 813–822. doi:10.1093/biosci/biy097

Collins, S. M., Yuan, S., Tan, P. N., Oliver, S. K., Lapierre, J. F., Cheruvelil, K. S., et al. (2019). Winter Precipitation and Summer Temperature Predict Lake Water Quality at Macroscales. Water Resour. Res. 55, 2708–2721. doi:10.1029/2018wr023088

Corti, R., and Datry, T. (2016). Terrestrial and Aquatic Invertebrates in the Riverbed of an Intermittent River: Parallels and Contrasts in Community Organisation. Freshw. Biol. 61, 1308–1320. doi:10.1111/fwb.12692

Crait, J. R., and Ben-David, M. (2007). Effects of River Otter Activity on Terrestrial Plants in Trophically Altered Yellowstone Lake. Ecology 88, 1040–1052. doi:10.1890/06-0078

Cummins, K. W., Wilzbach, M. A., Gates, D. M., Perry, J. B., and Taliaferro, W. B. (1989). Shredders and Riparian Vegetation. BioScience 39, 24–30. doi:10.2307/1310804

Dahlin, K. M., Asner, G. P., and Field, C. B. (2013). Environmental and Community Controls on Plant Canopy Chemistry in a Mediterranean-type Ecosystem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 6895–6900. doi:10.1073/pnas.1215513110

Darimont, C. T., Carlson, S. M., Kinnison, M. T., Paquet, P. C., Reimchen, T. E., and Wilmers, C. C. (2009). Human Predators Outpace Other Agents of Trait Change in the Wild: Fig. 1. Pnas 106, 952–954. doi:10.1073/pnas.0809235106

Dillon, P. J., and Rigler, F. H. (1974). The Phosphorus-Chlorophyll Relationship in Lakes1,2. Limnol. Oceanogr. 19, 767–773. doi:10.4319/lo.1974.19.5.0767

Dinerstein, E., Olson, D., Joshi, A., Vynne, C., Burgess, N. D., Wikramanayake, E., et al. (2017). An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm. BioScience 67, 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014

Dodds, W. K., Rose, K. C., Fei, S., and Chandra, S. (2021). Macrosystems Revisited: Challenges and Successes in a New Subdiscipline of Ecology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 19, 4–10. doi:10.1002/fee.2286

Dodson, S. I., Arnott, S. E., and Cottingham, K. L. (2000). The Relationship in lake Communities between Primary Productivity and Species Richness. Ecology 81, 2662–2679. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[2662:trilcb]2.0.co;2

Dolný, A., Harabiš, F., Bártaa, D., Lhota, S., and Drozd, P. (2013). Aquatic Insects Indicate Terrestrial Habitat Degradation: Changes in Taxonomical Structure and Functional Diversity of Dragonflies in Tropical Rainforest of East Kalimantan. Trop. Zoolog. 25, 141–157. doi:10.1080/03946975.2012.717480

Dudgeon, D., Arthington, A. H., Gessner, M. O., Kawabata, Z.-I., Knowler, D. J., Lévêque, C., et al. (2006). Freshwater Biodiversity: Importance, Threats, Status and Conservation Challenges. Biol. Rev. 81, 163. doi:10.1017/s1464793105006950

Edvardsen, A., and Økland, R. H. (2006). Variation in Plant Species Composition in and Adjacent to 64 Ponds in SE Norwegian Agricultural Landscapes. Aquat. Bot. 85, 92–102. doi:10.1016/j.aquabot.2006.01.015

Eisenhauer, N., Lanoue, A., Strecker, T., Scheu, S., Steinauer, K., Thakur, M. P., et al. (2017). Root Biomass and Exudates Link Plant Diversity with Soil Bacterial and Fungal Biomass. Sci. Rep. 7, srep44641. doi:10.1038/srep44641

Elser, J. J., Fagan, W. F., Denno, R. F., Dobberfuhl, D. R., Folarin, A., Huberty, A., et al. (2000). Nutritional Constraints in Terrestrial and Freshwater Food Webs. Nature 408, 578–580. doi:10.1038/35046058

Emery, S. M., and Rudgers, J. A. (2014). Biotic and Abiotic Predictors of Ecosystem Engineering Traits of the Dune Building grass,Ammophila Breviligulata. Ecosphere 5, art87. doi:10.1890/es13-00331.1

Fei, S., Guo, Q., and Potter, K. (2016). Macrosystems Ecology: Novel Methods and New Understanding of Multi-Scale Patterns and Processes. Landscape Ecol. 31, 1–6. doi:10.1007/s10980-015-0315-0

Finstad, A. G., and Hein, C. L. (2012). Migrate or Stay: Terrestrial Primary Productivity and Climate Drive Anadromy in Arctic Char. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 2487–2497. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02717.x

Gende, S. M., Edwards, R. T., Willson, M. F., and Wipfli, M. S. (2002). Pacific Salmon in Aquatic and Terrestrial Ecosystems. BioScience 52, 917–928. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2002)052[0917:psiaat]2.0.co;2

Gergs, R., Koester, M., Schulz, R. S., and Schulz, R. (2014). Potential Alteration of Cross-Ecosystem Resource Subsidies by an Invasive Aquatic Macroinvertebrate: Implications for the Terrestrial Food Web. Freshw. Biol. 59, 2645–2655. doi:10.1111/fwb.12463

Gonzalez, A., Germain, R. M., Srivastava, D. S., Filotas, E., Dee, L. E., Gravel, D., et al. (2020). Scaling‐up Biodiversity‐ecosystem Functioning Research. Ecol. Lett. 23, 757–776. doi:10.1111/ele.13456

Grace, J. B., Anderson, T. M., Seabloom, E. W., Borer, E. T., Adler, P. B., Harpole, W. S., et al. (2016). Integrative Modelling Reveals Mechanisms Linking Productivity and Plant Species Richness. Nature 529, 390–393. doi:10.1038/nature16524

Gratton, C., Hoekman, D., Dreyer, J., and Jackson, R. D. (2017). Increased Duration of Aquatic Resource Pulse Alters Community and Ecosystem Responses in a Subarctic Plant Community. Ecology 98, 2860–2872. doi:10.1002/ecy.1977

Gratton, C., and Zanden, M. J. V. (2009). Flux of Aquatic Insect Productivity to Land: Comparison of Lentic and Lotic Ecosystems. Ecology 90, 2689–2699. doi:10.1890/08-1546.1

Grimm, N. B., Gergel, S. E., McDowell, W. H., Boyer, E. W., Dent, C. L., Groffman, P., et al. (2003). Merging Aquatic and Terrestrial Perspectives of Nutrient Biogeochemistry. Oecologia 137, 485–501. doi:10.1007/s00442-003-1382-5

Grootjans, A. P., Ernst, W. H. O., and Stuyfzand, P. J. (1998). European Dune Slacks: Strong Interactions of Biology, Pedogenesis and Hydrology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 96–100. doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(97)01231-7

Hagar, J. C., Li, J., Sobota, J., and Jenkins, S. (2012). Arthropod Prey for Riparian Associated Birds in Headwater Forests of the Oregon Coast Range. For. Ecol. Manage. 285, 213–226. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2012.08.026

Hart, B. T., Lake, P. S., Webb, J. A., and Grace, M. R. (2003). Ecological Risk to Aquatic Systems from Salinity Increases. Aust. J. Bot. 51, 689–702. doi:10.1071/bt02111

Hastings, A., Byers, J. E., Crooks, J. A., Cuddington, K., Jones, C. G., Lambrinos, J. G., et al. (2007). Ecosystem Engineering in Space and Time. Ecol. Lett. 10, 153–164. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00997.x

Heffernan, J. B., Soranno, P. A., Angilletta, M. J., Buckley, L. B., Gruner, D. S., Keitt, T. H., et al. (2014). Macrosystems Ecology: Understanding Ecological Patterns and Processes at continental Scales. Front. Ecol. Environ. 12, 5–14. doi:10.1890/130017

Hermoso, V., Vasconcelos, R. P., Henriques, S., Filipe, A. F., and Carvalho, S. B. (2021). Conservation Planning across Realms: Enhancing Connectivity for Multi‐realm Species. J. Appl. Ecol. 58, 644–654. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13796

H. Lieth, and R. H. Whittaker (1975). in Primary Productivity of the Biosphere (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg).

Holland, R. A., Eigenbrod, F., Armsworth, P. R., Anderson, B. J., Thomas, C. D., Heinemeyer, A., et al. (2011). Spatial Covariation between Freshwater and Terrestrial Ecosystem Services. Ecol. Appl. 21, 2034–2048. doi:10.1890/09-2195.1

Hooper, D. U., Adair, E. C., Cardinale, B. J., Byrnes, J. E. K., Hungate, B. A., Matulich, K. L., et al. (2012). A Global Synthesis Reveals Biodiversity Loss as a Major Driver of Ecosystem Change. Nature 486, 105–108. doi:10.1038/nature11118

Jackrel, S. L., and Wootton, J. T. (2014). Local Adaptation of Stream Communities to Intraspecific Variation in a Terrestrial Ecosystem Subsidy. Ecology 95, 37–43. doi:10.1890/13-0804.1

Jardine, A., Speldewinde, P., Carver, S., and Weinstein, P. (2007). Dryland Salinity and Ecosystem Distress Syndrome: Human Health Implications. EcoHealth 4, 10–17. doi:10.1007/s10393-006-0078-9

Jetz, W., Cavender-Bares, J., Pavlick, R., Schimel, D., Davis, F. W., Asner, G. P., et al. (2016). Monitoring Plant Functional Diversity from Space. Nat. Plants 2, 16024. doi:10.1038/nplants.2016.39

Johnston, C. A., and Naiman, R. J. (1990). Browse Selection by beaver: Effects on Riparian forest Composition. Can. J. For. Res. 20, 1036–1043. doi:10.1139/x90-138

Jones, C. G., Lawton, J. H., and Shachak, M. (1994). Organisms as Ecosystem Engineers. Oikos 69, 373–386. doi:10.2307/3545850

Junk, W. J., Bayley, P. B., and Sparks, R. E. (1989). “The Flood Pulse Concept in River-Floodplain Systems,” in Proceedings of the International Large River Symposium, Honey Harbour, ON, Canada, September 14–21, 1986. Editor D. P. Dodge, 110–127. (Can. Spec. Publ. Fish. Aquat. Sci.).

Kärnä, O.-M., Heino, J., Laamanen, T., Jyrkänkallio-Mikkola, J., Pajunen, V., Soininen, J., et al. (2019). Does Catchment Geodiversity foster Stream Biodiversity? Landscape Ecol. 34, 2469–2485. doi:10.1007/s10980-019-00901-z

Kautza, A., and Sullivan, S. M. P. (2015). Shifts in Reciprocal River-Riparian Arthropod Fluxes along an Urban-Rural Landscape Gradient. Freshw. Biol. 60, 2156–2168. doi:10.1111/fwb.12642

Keith, D. A., Ferrer-Paris, J. R., Nicholson, E., and Kingsford, R. T. (2020). The IUCN Global Ecosystem Typology 2.0: Descriptive profiles for biomes and ecosystem functional groups. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

Klemmer, A. J., Galatowitsch, M. L., and McIntosh, A. R. (2020). Cross-ecosystem Bottlenecks Alter Reciprocal Subsidies within Meta-Ecosystems: Bottlenecks to Reciprocal Subsidies. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 287, 20200550. doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.0550

Kneitel, J. M., and Lessin, C. L. (2010). Ecosystem-phase Interactions: Aquatic Eutrophication Decreases Terrestrial Plant Diversity in California vernal Pools. Oecologia 163, 461–469. doi:10.1007/s00442-009-1529-0

Lapierre, J. F., Collins, S. M., Seekell, D. A., Spence Cheruvelil, K., Tan, P. N., Skaff, N. K., et al. (2018). Similarity in Spatial Structure Constrains Ecosystem Relationships: Building a Macroscale Understanding of Lakes. Glob. Ecol Biogeogr 27, 1251–1263. doi:10.1111/geb.12781

Lecerf, A., and Richardson, J. S. (2010). Biodiversity-ecosystem Function Research: Insights Gained from Streams. River Res. Applic. 26, 45–54. doi:10.1002/rra.1286

Lefcheck, J. S., Orth, R. J., Dennison, W. C., Wilcox, D. J., Murphy, R. R., Keisman, J., et al. (2018). Long-term Nutrient Reductions lead to the Unprecedented Recovery of a Temperate Coastal Region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 201715798. doi:10.1073/pnas.1715798115

Levy, O., Ball, B. A., Bond-Lamberty, B., Cheruvelil, K. S., Finley, A. O., Lottig, N. R., et al. (2014). Approaches to advance Scientific Understanding of Macrosystems Ecology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 12, 15–23. doi:10.1890/130019

Liang, J., Crowther, T. W., Picard, N., Wiser, S., Zhou, M., Alberti, G., et al. (2016). Positive Biodiversity-Productivity Relationship Predominant in Global Forests. Science 354, aaf8957. doi:10.1126/science.aaf8957

Likens, G. E. (1975). “Primary Production of Inland Aquatic Ecosystems,” in Primary Productivity of the Biosphere (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer), 185–202.

Lomolino, M. V., Riddle, B. R., Whittaker, R. J., and Brown, J. H. (2010). Biogeography. 4th edition. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

Loreau, M., Mouquet, N., and Gonzalez, A. (2003a). Biodiversity as Spatial Insurance in Heterogeneous Landscapes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 12765–12770. doi:10.1073/pnas.2235465100

Loreau, M., Mouquet, N., and Holt, R. D. (2003b). Meta-ecosystems: A Theoretical Framework for a Spatial Ecosystem Ecology. Ecol. Lett. 6, 673–679. doi:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00483.x

Lynam, C. P., Llope, M., Möllmann, C., Helaouët, P., Bayliss-Brown, G. A., and Stenseth, N. C. (2017). Interaction between Top-Down and Bottom-Up Control in marine Food Webs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 1952–1957. doi:10.1073/pnas.1621037114

Marczak, L. B., Thompson, R. M., and Richardson, J. S. (2007). Meta-analysis: Trophic Level, Habitat, and Productivity Shape the Food Web Effects of Resource Subsidies. Ecology 88, 140–148. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2007)88[140:mtlhap]2.0.co;2

Martay, B., Brewer, M. J., Elston, D. A., Bell, J. R., Harrington, R., Brereton, T. M., et al. (2016). Impacts of Climate Change on National Biodiversity Population Trends. Ecography 40 (10), 1139–1151. Available at: Ecography:n/a-n/a. doi:10.1111/ecog.02411

McCaffery, M., and Eby, L. (2016). Beaver Activity Increases Aquatic Subsidies to Terrestrial Consumers. Freshw. Biol. 61, 518–532. doi:10.1111/fwb.12725

McCullough, I. M., King, K. B. S., Stachelek, J., Diaz, J., Soranno, P. A., and Cheruvelil, K. S. (2019). Applying the Patch-Matrix Model to Lakes: a Connectivity-Based Conservation Framework. Landscape Ecol. 34, 2703–2718. doi:10.1007/s10980-019-00915-7

McIntyre, P. B., Jones, L. E., Flecker, A. S., and Vanni, M. J. (2007). Fish Extinctions Alter Nutrient Recycling in Tropical Freshwaters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104, 4461–4466. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608148104

Mokany, K., Ferrier, S., Harwood, T. D., Ware, C., Di Marco, M., Grantham, H. S., et al. (2020). Reconciling Global Priorities for Conserving Biodiversity Habitat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9906–9911. doi:10.1073/pnas.1918373117

Moore, A. A., and Palmer, M. A. (2005). Invertebrate Biodiversity in Agricultural and Urban Headwater Streams: Implications for Conservation and Management. Ecol. Appl. 15, 1169–1177. doi:10.1890/04-1484

Mosepele, K., Moyle, P. B., Merron, G. S., Purkey, D. R., and Mosepele, B. (2009). Fish, Floods, and Ecosystem Engineers: Aquatic Conservation in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. BioScience 59, 53–64. doi:10.1525/bio.2009.59.1.9

Muehlbauer, J. D., Collins, S. F., Doyle, M. W., and Tockner, K. (2014). How Wide Is a Stream? Spatial Extent of the Potential "stream Signature" in Terrestrial Food Webs Using Meta-Analysis. Ecology 95, 44–55. doi:10.1890/12-1628.1

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B., and Kent, J. (2000). Biodiversity Hotspots for Conservation Priorities. Nature 403, 853–858. doi:10.1038/35002501

Naiman, R. J., Pinay, G., Johnston, C. A., and Pastor, J. (1994). Beaver Influences on the Long-Term Biogeochemical Characteristics of Boreal Forest Drainage Networks. Ecology 75, 905–921. doi:10.2307/1939415

Nakano, S., Miyasaka, H., and Kuhara, N. (1999). Terrestrial-aquatic Linkages: Riparian Arthropod Inputs Alter Trophic Cascades in a Stream Food Web. Ecology 80, 2435–2441. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1999)080[2435:talrai]2.0.co;2

Nilsson, C., Reidy, C. A., Dynesius, M., and Revenga, C. (2005). Fragmentation and Flow Regulation of the World's Large River Systems. Science 308, 405–408. doi:10.1126/science.1107887

Odum, H. T. (1956). Primary Production in Flowing Waters1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1, 102–117. doi:10.4319/lo.1956.1.2.0102

Parmesan, C. (2006). Ecological and Evolutionary Responses to Recent Climate Change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 37, 637–669. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110100

Polis, G. A., and Hurd, S. D. (1995). Extraordinarily High Spider Densities on Islands: Flow of Energy from the marine to Terrestrial Food Webs and the Absence of Predation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 92, 4382–4386. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.10.4382

Polis, G. A. (1999). Why Are Parts of the World Green? Multiple Factors Control Productivity and the Distribution of Biomass. Oikos 86, 3–15. doi:10.2307/3546565

Power, M. E., Rainey, W. E., Parker, M. S., Sabo, J. L., Smyth, A., Khandwala, S., et al. (2004). “River-to-watershed Subsidies in an Old-Growth conifer forest,” in Food Webs at the Landscape Level. Editors G. A. Polis, M. E. Power, and G. R. Huxel (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press), 217–240.

Purdy, S. E., Moyle, P. B., and Tate, K. W. (2012). Montane Meadows in the Sierra Nevada: Comparing Terrestrial and Aquatic Assessment Methods. Environ. Monit. Assess. 184, 6967–6986. doi:10.1007/s10661-011-2473-0

Relyea, R. A. (2005). The Impact of Insecticides and Herbicides on the Biodiversity and Productivity of Aquatic Communities. Ecol. Appl. 15, 618–627. doi:10.1890/03-5342

Revenga, C., Campbell, I., Abell, R., de Villiers, P., and Bryer, M. (2005). Prospects for Monitoring Freshwater Ecosystems towards the 2010 Targets. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 360, 397–413. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1595

Rose, K. C., Graves, R. A., Hansen, W. D., Harvey, B. J., Qiu, J., Wood, S. A., et al. (2017). Historical Foundations and Future Directions in Macrosystems Ecology. Ecol. Lett. 20, 147–157. doi:10.1111/ele.12717

Roy, J., Mooney, H. A., and Saugier, B. (2001). Terrestrial Global Productivity. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Sabo, D., and Hagen, E. M. (2012). Einführung. Water Resour. Res. 48, 1–9. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-25876-3_1

Sabo, J. L., and Power, M. E. (2002). River-Watershed Exchange: Effects of Riverine Subsidies on Riparian Lizards and Their Terrestrial Prey. Ecology 83, 1860–1869. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[1860:rweeor]2.0.co;2

Sanpera-Calbet, I., Lecerf, A., and Chauvet, E. (2009). Leaf Diversity Influences In-Stream Litter Decomposition through Effects on Shredders. Freshw. Biol. 54, 1671–1682. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.2009.02216.x

Sanzone, D. M., Meyer, J. L., Marti, E., Gardiner, E. P., Tank, J. L., and Grimm, N. B. (2003). Carbon and Nitrogen Transfer from a Desert Stream to Riparian Predators. Oecologia 134, 238–250. doi:10.1007/s00442-002-1113-3

Sarneel, J. M., Huig, N., Veen, G. F., Rip, W., and Bakker, E. S. (2014). Herbivores Enforce Sharp Boundaries between Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecosystems. Ecosystems 17, 1426–1438. doi:10.1007/s10021-014-9805-1

Schindler, D. E., Armstrong, J. B., Bentley, K. T., Jankowski, K., Lisi, P. J., and Payne, L. X. (2013). Riding the Crimson Tide: mobile Terrestrial Consumers Track Phenological Variation in Spawning of an Anadromous Fish. Biol. Lett. 9, 20130048. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2013.0048

Schindler, D. E., Carpenter, S. R., Cole, J. J., Kitchell, J. F., and Pace, M. L. (1997). Influence of Food Web Structure on Carbon Exchange between Lakes and the Atmosphere. Science 277, 248–251. doi:10.1126/science.277.5323.248

Schriever, T. A., Cadotte, M. W., and Williams, D. D. (2014). How Hydroperiod and Species Richness Affect the Balance of Resource Flows across Aquatic-Terrestrial Habitats. Aquat. Sci. 76, 131–143. doi:10.1007/s00027-013-0320-9

Soininen, J., Bartels, P., Heino, J., Luoto, M., and Hillebrand, H. (2015). Toward More Integrated Ecosystem Research in Aquatic and Terrestrial Environments. BioScience 65, 174–182. doi:10.1093/biosci/biu216

Soininen, J., and Luoto, M. (2012). Is Catchment Productivity a Useful Predictor of Taxa Richness in lake Plankton Communities? Ecol. Appl. 22, 624–633. doi:10.1890/11-1126.1

Soranno, P. A., Wagner, T., Collins, S. M., Lapierre, J. F., Lottig, N. R., and Oliver, S. K. (2019). Spatial and Temporal Variation of Ecosystem Properties at Macroscales. Ecol. Lett. 22, 1587–1598. doi:10.1111/ele.13346

Stachelek, J., Weng, W., Carey, C. C., Kemanian, A. R., Cobourn, K. M., Wagner, T., et al. (2020). Granular Measures of Agricultural Land Use Influence lake Nitrogen and Phosphorus Differently at Macroscales. Ecol. Appl. 30, 1–13. doi:10.1002/eap.2187

Stahlschmidt, P., Pätzold, A., Ressl, L., Schulz, R., and Brühl, C. A. (2012). Constructed Wetlands Support Bats in Agricultural Landscapes. Basic Appl. Ecol. 13, 196–203. doi:10.1016/j.baae.2012.02.001

Stoler, A. B., and Relyea, R. A. (2016). Leaf Litter Species Identity Alters the Structure of Pond Communities. Oikos 125, 179–191. doi:10.1111/oik.02480

Subalusky, A. L., Dutton, C. L., Rosi-Marshall, E. J., and Post, D. M. (2015). The hippopotamus Conveyor belt: Vectors of Carbon and Nutrients from Terrestrial Grasslands to Aquatic Systems in Sub-saharan Africa. Freshw. Biol. 60, 512–525. doi:10.1111/fwb.12474

Sullivan, S. M. P., and Manning, D. W. P. (2019). Aquatic-terrestrial Linkages as Complex Systems: Insights and Advances from Network Models. Freshw. Sci. 38, 936–945. doi:10.1086/706071

Suurkuukka, H., Virtanen, R., Suorsa, V., Soininen, J., Paasivirta, L., and Muotka, T. (2014). Woodland Key Habitats and Stream Biodiversity: Does Small-Scale Terrestrial Conservation Enhance the protection of Stream Biota? Biol. Conservation 170, 10–19. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2013.10.009

Thompson, P. L., Isbell, F., Loreau, M., O’connor, M. I., and Gonzalez, A. (2018). The Strength of the Biodiversity-Ecosystem Function Relationship Depends on Spatial Scale. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 285, 1–9. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.0038

Tilman, D., Hill, J., and Lehman, C. (2006). Carbon-Negative Biofuels from Low-Input High-Diversity Grassland Biomass. Science 314, 1598–1600. doi:10.1126/science.1133306

Tilman, D., Knops, J., Wedin, D., Reich, P., Ritchie, M., and Siemann, E. (1997). The Influence of Functional Diversity and Composition on Ecosystem Processes. Science 277, 1300–1302. doi:10.1126/science.277.5330.1300

Tonkin, J. D., Stoll, S., Jähnig, S. C., and Haase, P. (2016). Contrasting Metacommunity Structure and Beta Diversity in an Aquatic-Floodplain System. Oikos 125, 686–697. doi:10.1111/oik.02717

Tromboni, F., Liu, J., Ziaco, E., Breshears, D. D., Thompson, K. L., Dodds, W. K., et al. (2021). Macrosystems as Metacoupled Human and Natural Systems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 19, 20–29. doi:10.1002/fee.2289

Twardochleb, L. A., Olden, J. D., and Larson, E. R. (2013). A Global Meta-Analysis of the Ecological Impacts of Nonnative Crayfish. Freshw. Sci. 32, 1367–1382. doi:10.1899/12-203.1

Urban, M. C. (2015). Accelerating Extinction Risk from Climate Change. Science 348, 571–573. doi:10.1126/science.aaa4984

Vander Zanden, M. J., and Gratton, C. (2011). Blowin' in the Wind: Reciprocal Airborne Carbon Fluxes between Lakes and Land This Paper Is Based on the J.C. Stevenson Memorial Lecture Presented at the Canadian Conference for Fisheries Research (CCFFR) in Ottawa, Ontario, 9-11 January 2009. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 68, 170–182. doi:10.1139/f10-157

Vannote, R. L., Minshall, G. W., Cummins, K. W., Sedell, J. R., and Cushing, C. E. (1980). The River Continuum Concept. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 37, 130–137. doi:10.1139/f80-017

Vellend, M., Baeten, L., Becker-Scarpitta, A., Boucher-Lalonde, V., McCune, J. L., Messier, J., et al. (2017). Plant Biodiversity Change across Scales During the Anthropocene. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 68, 563–586. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042916-040949

Vidal, M. C., and Murphy, S. M. (2018). Bottom‐up vs. Top‐down Effects on Terrestrial Insect Herbivores: a Meta‐analysis. Ecol. Lett. 21, 138–150. doi:10.1111/ele.12874

Vinson, M. R., and Hawkins, C. P. (2003). Broad-scale Geographical Patterns in Local Stream Insect Genera Richness. Ecography 26, 751–767. doi:10.1111/j.0906-7590.2003.03397.x

Wallace, J. B., Eggert, S. L., Meyer, J. L., and Webster, J. R. (1997). Multiple Trophic Levels of a Forest Stream Linked to Terrestrial Litter Inputs. Science 277, 102–104. doi:10.1126/science.277.5322.102

Ward, J. V., Tockner, K., Arscott, D. B., and Claret, C. (2002). Riverine Landscape Diversity. Freshw. Biol. 47, 517–539. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2427.2002.00893.x

Wesner, J. S. (2012). Predator Diversity Effects cascade across an Ecosystem Boundary. Oikos 121, 53–60. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2011.19413.x

Wright, J. P., Jones, C. G., and Flecker, A. S. (2002). An Ecosystem Engineer, the beaver, Increases Species Richness at the Landscape Scale. Oecologia 132, 96–101. doi:10.1007/s00442-002-0929-1

Wuchty, S., Jones, B. F., and Uzzi, B. (2007). The Increasing Dominance of Teams in Production of Knowledge. Science 316, 1036–1039. doi:10.1126/science.1136099

Yang, X., Pavelsky, T. M., and Allen, G. H. (2020). The Past and Future of Global River Ice. Nature 577, 69–73. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1848-1

Zarnetske, P. L., Hacker, S. D., Seabloom, E. W., Ruggiero, P., Killian, J. R., Maddux, T. B., et al. (2012). Biophysical Feedback Mediates Effects of Invasive Grasses on Coastal Dune Shape. Ecology 93 (6), 1439–1450. doi:10.1890/11-1112.1

Keywords: biodiversity, cross-system subsidies, ecological realms, ecosystem engineering, ecosystem function, hydrology

Citation: Dahlin KM, Zarnetske PL, Read QD, Twardochleb LA, Kamoske AG, Cheruvelil KS and Soranno PA (2021) Linking Terrestrial and Aquatic Biodiversity to Ecosystem Function Across Scales, Trophic Levels, and Realms. Front. Environ. Sci. 9:692401. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2021.692401

Received: 08 April 2021; Accepted: 01 June 2021;

Published: 15 June 2021.

Edited by:

Teresa Ferreira, University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Jeff Wesner, University of South Dakota, United StatesAna Filipa Filipe, University of Lisbon, Portugal

Norman Mercado-Silva, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Mexico

Copyright © 2021 Dahlin, Zarnetske, Read, Twardochleb, Kamoske, Cheruvelil and Soranno. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kyla M. Dahlin, a2RhaGxpbkBtc3UuZWR1

Kyla M. Dahlin

Kyla M. Dahlin Phoebe L. Zarnetske

Phoebe L. Zarnetske Quentin D. Read4

Quentin D. Read4 Laura A. Twardochleb

Laura A. Twardochleb