95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Environ. Sci. , 25 February 2021

Sec. Conservation and Restoration Ecology

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2021.595169

Saloni Bhatia1,2,3*

Saloni Bhatia1,2,3* Kulbhushansingh Suryawanshi1,2

Kulbhushansingh Suryawanshi1,2 Stephen Mark Redpath4

Stephen Mark Redpath4 Stanzin Namgail5

Stanzin Namgail5 Charudutt Mishra1,2

Charudutt Mishra1,2People’s views and values for wild animals are often a result of their experiences and traditional knowledge. Local folklore represents a resource that can enable an understanding of the nature of human-wildlife interactions, especially the underlying cultural values. Using archival searches and semi-structured interviews, we collected narratives about the ibex (Capra sibirica) (n = 69), and its predators, the wolf (Canis lupus) (n = 52) and the snow leopard (Panthera uncia) (n = 43), in Ladakh, India. We compared these stories to those of a mythical carnivore called seng ge or snow lion (n = 19), frequently referenced in local Tibetan Buddhist folklore and believed to share many of the traits commonly associated with snow leopards (except for livestock depredation). We then categorized the values along social-cultural, ecological and psychological dimensions. We found that the ibex was predominantly associated with utilitarianism and positive symbolism. Both snow leopard and wolf narratives referenced negative affective and negative symbolic values, though more frequently in the case of wolves. Snow leopard narratives largely focused on utilitarian and ecologistic values. In contrast, snow lion narratives were mostly associated with positive symbolism. Our results suggest that especially for snow leopards and wolves, any potentially positive symbolic associations appeared to be overwhelmed by negative sentiments because of their tendency to prey on livestock, unlike in the case of the snow lion. Since these values reflect people’s real and multifarious interactions with wildlife, we recommend paying greater attention to understanding the overlaps between natural and cultural heritage conservation to facilitate human-wildlife coexistence.

People’s relationship with wild animals is rarely simple or static. It covers multiple states from reverence to fear, sometimes simultaneously. However, the term human-wildlife conflict has assumed centerstage, leading to the belief that most forms of interaction with wildlife result in damage to life and/or property (Redpath et al., 2014). Human-wildlife interactions are instead better viewed along a spectrum ranging from negative to positive (Bhatia et al., 2019). One way to understand how people build and sustain complex and multifarious connections with wildlife is to examine folklore and narratives in which the two are intertwined (Hughes et al., 2020).

Folklore is defined as a traditional dramatic narrative that is primarily (though not necessarily) transmitted orally (Fischer, 1963). Throughout history, myths, fables, anecdotes and legends have provided a window to understanding the interconnections between the human and more-than-human worlds (Fischer, 1963). Animals in folklore allow us to think about and make sense of social structures and moral codes (Levi-Strauss, 1963; Aas, 2008; Herrmann et al., 2013) and can also enable us to participate in political discourses about nature and its management (Woods, 2000).

Knowledge, experience and beliefs iteratively feed into each other and affect how people relate to wild animals. In India, for instance, carnivores like the leopard (Panthera pardus) and the tiger (Panthera tigris) are associated with powerful deities and are thus worshipped in some parts of the country (Athreya et al., 2018). In many Asian and African cultures, primates are culturally revered. This is presumed to make people more tolerant toward crop damage caused by them (Knight, 1999; Baker et al., 2014; Saraswat et al., 2015). Cultural taboos and beliefs can also have negative impacts on wildlife. For example, local communities have been reported to associate the Zanzibar leopard (Panthera pardus adersi) with witchcraft and sorcery and are thus afraid of this feline (Walsh and Goldman, 2007).

Stories can be contradictory, mirroring the ambiguity and heterogeneity in people’s sentiments. In rural Iberia and Mongolia, for example, folk legends describe the wolf (Canis lupus) as a diabolical or dangerous creature, a totemic animal reflecting courage and fearlessness, as well as a savior (Hunt, 2008; LeGrys, 2009). Similarly, folklore around the kodkod cat (Leopardus guigna) and puma (Puma concolor) show that both felids are associated with a range of positive and negative values (Herrmann et al., 2013).

As demonstrated above, folklore frequently juxtaposes humans and animals, pointing to similarities and differences between the two, thereby conveying salient cultural values (Tapper, 1988). Human values are considered the cornerstones of culture (Hofstede, 1984). Values are defined as “conceptions of the desirable that guide the way social actors (e.g., organizational leaders, policy-makers, individual persons) select actions, evaluate people and events, and explain their actions and evaluations” (Schwartz 1999, p. 24). Values are the defining feature of ethics and morality (Fox and Bekoff, 2011).

A study of wildlife values and attitudes toward wolves and coyotes (Canis latrans) in the United States noted that certain set of values were closely tied to positive and negative responses toward the two predators (Kellert, 1985). Values such as love for the outdoors, concern for the environment and the ethics of animal welfare were correlated with positive responses whereas values like animal use and aversion or fear of wildlife were associated with negative responses. Kellert (1985) further suggested that the negative responses could be a result of legends and myths that framed the predators in an unfavorable light. Understanding the links between folklore and human values could, therefore, enable conservation practitioners to incorporate biocultural heritage into conservation messaging, which is likely to resonate with communities sharing space with wildlife (Fernández-Llamazares and Cabeza, 2017). However, this remains an understudied field in academia, especially in the context of conservation.

We therefore sought to understand the values ascribed to high altitude mammals in local folklore. While we were open to stories on any wildlife species, we found an adequate number of stories on the primary wild prey, the ibex (Capra sibirica) and its top predators, the wolf and the snow leopard (Panthera uncia). Together, the two carnivores are responsible for most of the livestock predation by wild animals in the Central and South Asian high mountains (Jackson et al., 2010; Mishra and Suryawanshi, 2014). People’s attitudes toward these carnivores, however, are not defined by livestock losses alone but are influenced by socio-cultural factors like perceptions of risk as well as social norms (Bhatia et al., 2020). We also contrasted values associated with these real-life, damage-causing predators with a mythical predator, the snow lion or seng ge, that is not responsible for livestock predation. This allowed a better understanding of whether and how values differed based on people’s lived experiences.

Previously located in the Indian State of Jammu & Kashmir and now a Union Territory, Ladakh is a cold-desert where elevations exceed 3500 m above msl with temperatures ranging from –30 °C to 30 °C in winter and summer, respectively. The region is inhabited by wild ungulates like the ibex, blue sheep (Pseudois nayaur), Tibetan argali (Ovis ammon), Ladakh urial (Ovis vignei), and Tibetan gazelle (Procapra picticaudata), and predators like the snow leopard, wolf, and lynx (Lynx). There is a widespread belief in the existence of a mythical creature called the snow lion or seng ge, frequently referred to in Tibetan Buddhist folklore. This carnivorous animal is believed to reside in remote glaciers. Its image is often carved or sculpted outside monasteries in Ladakh. It has a white body and a turquoise mane. The snow lion shares many traits with the snow leopard, for example, it has the ability to hunt and survive in the cold. It also possesses a camouflaged coat and a bushy tail. However, unlike the snow leopard it does not cause livestock depredation.

Ladakh has had various cultural influences especially from Central Asian, Balti, Kashmiri and Tibetan cultures, owing to its prominent place on the historic Silk Route (Rizvi, 1999; Sheikh, 2010). People’s customs and practices have been influenced by Bon (animistic religion), Buddhism and later, Islam. At present, people practice either Mahayana Buddhism or Twelver Shi’i Islam (Gupta, 2012; Bhatia et al., 2017). Most Ladakhis (Buddhists and Muslims) believe in the presence of protective deities (lhas and klus) at the level of the family, the village, and the mountains (Dollfus, 1997; Butcher, 2013). There is a widespread belief in shamanism in which deities are believed to communicate through designated oracles (female oracles are known as lha-mo and males as lha-pa, translated as “divine persons”) (Kressing, 2003). People occasionally consult astrologers (onpo) for advice and predictions, or to appease the deities. Buddhist communities seek the advice of monks as well as Tibetan medical practitioners (amchis) for their emotional and physical well-being. As in neighboring high-altitude landscapes, Ladakhis, too, engage in agriculture and livestock rearing for subsistence. Some of the socio-political drivers of change in this landscape include a period of colonialism, the presence of the Indian army post-independence, and increasing levels of domestic and international tourism in recent years (Bray, 2007).

We collected folklore around wildlife using a combination of online and library searches, and field-based interviews. Targeted online literature searches were conducted using the Pahar database (www.pahar.in, accessed on December 16, 2018), and publications uploaded by journals like International Association of Ladakh Studies (www.ladakhstudies.org/ladakh-studies-journal accessed on April 01, 2016), and Himalaya (www.himalayajournal.org, accessed on April 01, 2016), with a focus on articles on Ladakh and/or Jammu & Kashmir. The keywords broadly included terms like “Ladakh,” “Jammu & Kashmir,” “Wildlife,” “Folk,” “Culture.”

Simultaneously, book searches were conducted in 3 libraries—one in New Delhi (Tibet House) and two in Ladakh (District library and Central Institute of Buddhist Studies) (March to May 2016). These included books written in English by colonial travelers, explorers, hunters, missionaries, religious leaders, cultural researchers, and Tibetan medical practitioners—all in the context of the high Himalaya, especially Ladakh. The written archives dated from as far back as 1844 to 2013. The literature search was intentionally unstructured so that we could document as many stories as possible.

With relevant ethics (including BREB) clearance from the host institution, we then identified and interacted with 13 historians, researchers and practitioners working locally in the field of cultural preservation to identify general themes, relevant literature, and knowledgeable individuals who we could interview. We formulated a series of questions to guide our interviews with these individuals (Supplementary Material S1). Two of us (SB and SN) traveled to parts of central, western, and eastern Ladakh and using snowball sampling or chain sampling (Naderifar et al., 2017), interviewed a total of 90 elderly individuals (approx. age >60 years), including folk artists, herders, Tibetan medical practitioners, astrologers, and monks. The interviews were carried out from May to September 2016. We ensured that free, prior informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the interviews. We conducted the interviews in Hindi or Ladakhi (with assistance from an interpreter), depending on the preference of the individual.

Even though we welcomed stories around all animals, we found a reasonable sample of folklore/narratives around four species, namely the ibex, the wolf, the snow leopard, and the snow lion. We recorded stories that discussed their role in traditional medicine and rituals, as well as popular beliefs, sayings, anecdotes, and legends surrounding them (please see Supplementary Material S1 for the list of themes that were covered). We expected to find more negative values associated with carnivores as compared to their prey.

The interviews were transcribed into English by professionals hired for the purpose. Due to personnel issues, we could only transcribe 48 of the 90 interviews (41 men and 7 women) that were included in the present study.

In all, we shortlisted 16 oral and 53 written narratives for the ibex, 29 oral and 23 written narratives for the wolf, 23 oral and 20 written narratives for the snow leopard, and 5 oral and 14 written narratives for the snow lion.

Using these narratives, we identified the predominant value(s) ascribed to the three wild species and the mythical snow lion with the help of a pre-defined typology adapted from Kellert (1985). Kellert’s typology has been tested extensively in the context of North America and Europe. However, the scale can be considered universal in that the fundamental value structure is unlikely to change significantly between regions (Kellert, 1995). Our value typology touched upon ecological, socio-cultural as well as psychological dimensions enshrined in the text as well as the interviews (Table 1). We first split the values into sub-categories and then combined similar sub-categories to reflect the predominant value (Krippendorf, 2004). We created frequency distribution of each to understand what values were most referenced for each animal. We carried out our analysis in R version 3.5.0.

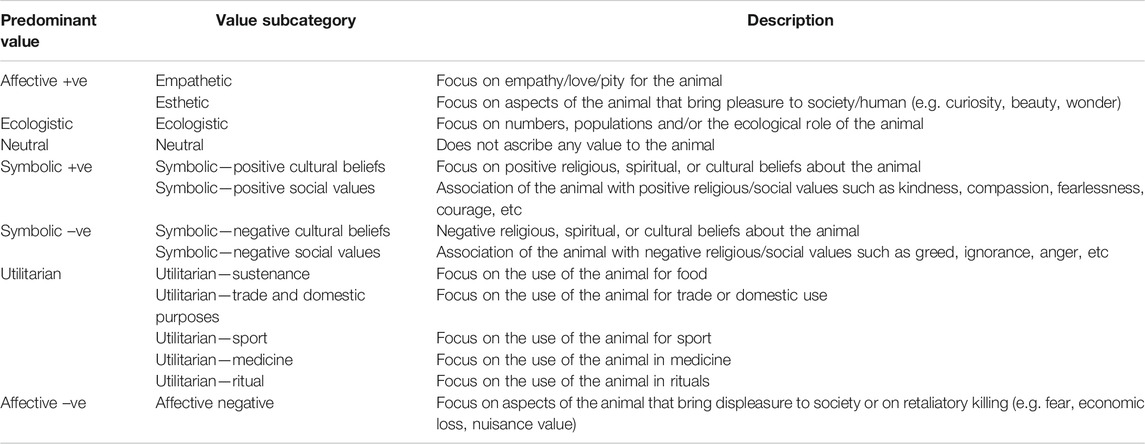

TABLE 1. Affective values focus on emotions while symbolic values focus on religious, spiritual or cultural beliefs; ecologistic values refer to ecological observations and utilitarian values focus on the use-value of the animal (adapted from Kellert, 1985).

The predominant value ascribed to the ibex was utilitarian (50.7%). A large part of the narratives were about its utility as a game animal (Figure 1). Other utilitarian values associated with the ibex were those that described their role in rituals, for example, ibex horns were offered to deities to appease them (Figure 2); their role in trade and domestic use, for example, the undercoat (known as asali tus) was a valuable trade item (Figure 2); and their role in sustenance, for example, ibex meat was consumed in the winters when there was a scarcity of food. Images of ibex hunt were common in prehistoric petroglyphs found locally (Figure 2). Some examples of folklore highlighting utilitarian values are presented below.

FIGURE 1. The predominant value ascribed in folklore and narratives to the ibex was utilitarian (50.7%), referring to its importance in sport, ritual, sustenance and domestic use or trade, followed by positive symbolic associations (27.5%) that link the animal with positive cultural beliefs and values. Other values associated with the ibex were ecologistic (15.9%), negative symbolic (2.8%), negative affective (1.4%), and positive affective (1.4%). The total number of narratives was 69.

FIGURE 2. Clockwise from top left: Image of a lhato—a structure dedicated to local protective deities consisting of ibex, asali tus or ibex undercoat, petroglyphs depicting the ibex and people, ibex figurines made of dough prepared as an offering to the deity during Losar (New Year) and at the time of birth of a male child.

A popular wedding folksong made references to ibex hunting:

“When an arrow flew to high heaven,

it brought back the wings of the bird-king.

When the arrow flew to the high cliff,

it brought down the muscles of the ibex.”

–Ribbach (1986, p.88)

Similarly, another folk song described the process of ibex hunting in the following manner:

“Take the arrows then the bow,

The arrow-shafts and the heads

O boy that art clever at hiding!

O boy that art clever at climbing;

O boy, clever at getting out of sight,

An ibex can be seen,

Ibex can be seen in a herd!

Now take the arrow, O boy!

Then take the arrow-shafts and heads,

O boy that art clever at driving them together;

O boy that art clever at driving them heaps;

Thou that art clever at singling out the best; Thou that art clever at shooting them!”

–Francke (1907, p. 37)

Hunting songs often described the fate of the ibex:

“Seven men had a discussion with each other, Hundred men assembled to go hunting,

Prepare the jaggery,

Prepare the barley flour and butter

Prepare the tip of the arrow, Prepare the bow made of sandal wood,

Prepare the sapphire-like dog,

Then send the men to the mountains,

Dispatch one group to the peak of the mountain,

Dispatch the other two on either side,

Then let loose the hunting dog

Drop a rock from the peak.

Then stealthily follow the ibex

The ibex was killed.

The hunters praized the gods,

Now you men descend from the mountains,

Then the flesh was cut with the knife.

Then the meat was roasted,

The roasted meat was distributed,

All the men received an equal share.”

–Phuntsog (2000, p. 225)

Apart from utilitarian values, narratives also associated the ibex with positive symbolism (27.5%). For example, the ibex, known for its nimbleness, was a mascot of the Ladakh Scouts infantry regiment of the Indian army. Ibex figurines made of dough were displayed during Losar (new year) and at the time of the birth of a child, especially a male child (Figure 2).

Positive symbolism vis-à-vis the ibex can be seen in the following song where the ibex is considered “pure” and therefore, the livestock (sometimes also referred to as a “horse”) of the protective deities:

“In my father’s place of (hunting) the ibex

There gather hundreds and thousands of large ibex

If the lhas and klus do not enjoy (this spectacle) who would enjoy it?

If the deities do not enjoy it, who would enjoy it?”

–Francke et al., (1899, p. 36)

Other values associated with the ibex were ecologistic, which focused on ecological and behavioral observations (15.9%), negative symbolic like negative cultural beliefs or stereotypes (2.8%), negative affective, that is, negative emotions like fear, dislike or desire to harm (1.4%), and positive affective, that is, positive emotions like compassion, love or empathy (1.4%).

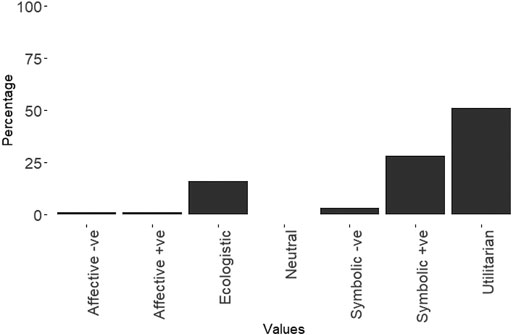

Narratives about the wolf frequently focused on the negative affective (34.6%), negative symbolic values (23%). These were followed by ecologistic (19.2%), utilitarian (7.6%), positive symbolic (5.7%), neutral (5.7%) and positive affective values (3.8%) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. The predominant values associated with the wolf were negative affective (34.6%), referring to emotions like fear, hatred, aversion or to retaliation, and negative symbolism (23%), associating the animal with negative cultural beliefs and values. These were followed by ecologistic (19.2%), utilitarian (7.6%), positive symbolic (5.7%), neutral (5.7%) and positive affective values (3.8%). The total number of narratives was 52.

Wolf was referred to as chanzan meaning a predator causing “menace.” Interviewees described many ways to trap and kill the wolf including snare and bait traps (Figure 4). Until recently, wolves that were killed would be paraded in the village by the hunters for a reward. If there was persistent depredation by wolves on livestock, communities would set out to locate wolf dens and pups and either set them on fire or seal the den or both.

FIGURE 4. A bait trap used for killing wolves. A goat or a sheep would be tied inside a deep pit surrounded by the circular wall seen above, which would attract the wolf. The wolf can jump in and access the bait but is unable to jump out due to the concave walls of the trap.

Fear, aversion and hatred for wolves was evident in many narratives. A saying used to describe the transitory nature of happiness invoked the relationship between the lamb and the wolf, where wolf was equated to trouble (Francke et al., 1899, p.111):

“Thinking, it will become happy and fat,

They sent the lamb to the meadow.

The thought, that the wolf would come.

That thought did not enter their minds.”

The lyrics of a song about aging and the virtue of humility contained the following stanza:

“On top of the mountains there is an arrogant wolf, But when it gets old it won’t be able to kill a lamb.”

Similarly, greed was another quality associated with the wolf evident in the proverb: “The wolf’s mouth is bloody through much eating” (Hamid, n.d., p.89) An interviewee narrated a long story of how a fox who was upset with the death of his friend, an ox, at the hands of a wolf, decided to seek revenge in the most gruesome. His means involved gluing the wolf’s eyes shut, locking it up in a box, sticking its tail into ice, loading its back with sacks of hay and a mattress, riding the wolf and finally, informing the villagers of its presence so they would kill it.

Another story in which goats sought revenge from a wolf was narrated to us:

“A wolf encountered the first goat and asked her, “What is on top of your head?” The goat answered, “These are my horns.” The wolf asked, “What is it that covers your body?” The goat said, “My wool.” Then the wolf asked, “What is it on your feet?” The goat replied, “My hooves.” Unsatisfied with the answers, the wolf killed the goat and ate her up. He then proceeded to the second goat, who gave similar replies and met the same fate. Finally, he faced the last goat, who was also the youngest. Ready to pounce, he asked the goat, “What is on top of your head?” “A knife to kill you,” she said. “What covers your body?” enquired the wolf. “It is a rope to tie you,” retorted the goat. The wolf, a bit suspicious now, proceeded to ask another question, “What covers your feet?” “My hooves to kick you,” replied the goat, and with this, she pierced her horns through the wolf, bound him with her wool, and knocked him dead with her hooves.”

We were informed that bad spirits (rolang) could manifest themselves as wolves, as could angry deities who had the ability to destroy their livestock. There was also a belief that a wolf howling while a body was being cremated was bad omen. A wolf walking in front of an individual on the road was also considered bad omen as was dreaming about the wolf. Calling someone a wolf usually amounted to a taunt and indicated that the person was cunning or untrustworthy. A popular saying demonstrating the wolf’s slyness was, “When the wolf falls into the pit, he is obliged to say “please sir” [or “dear sister”] to the goat [to escape].” Similarly, another saying about a wolf’s apparent untrustworthiness was explained to us, “Despite all the efforts to domesticate a wolf, you cannot make it a home-guarding dog.”

Though rare, we found some evidence of positive symbolism in the context of the wolf. For example, there were beliefs like “If one encounters a wolf then it is considered auspicious,” “Killing of wolves invites bad luck as they are protective deities.” Further, there were communities whose family names were based on the place they originated from, their occupation and sometimes, the relationship they had with predators. For example, it is possible that the family name Shan-pa refers to an individual/family who is believed to have descended from snow leopards whereas Shanku-pa could indicate a wolf lineage. This possibility, however, was not confirmed by the interviewees.

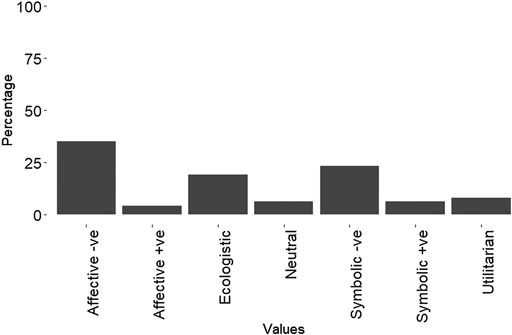

The predominant values ascribed to the snow leopard were utilitarian (28.5%) (Figure 5). Among the utilitarian narratives, most stories were about the domestic use or trade of its body parts, followed by stories about trophy hunting, and their use in traditional medicine and rituals.

FIGURE 5. The predominant values ascribed to the snow leopard were utilitarian (28.5%), referring to its importance in domestic use or trade, sport, medicine and ritual, and ecologistic (23.8%), referring to observations about its behavior and ecology, followed by negative affective (19%), negative symbolic (16.6%), positive affective (4.7%), positive symbolic (4.7%) and neutral values (2.3%). The total number of narratives was 43.

An interviewee explained that their fur was traditionally used to make shoes, bags, as well as line the jackets for warmth. Our interviewees told us that snow leopard organs and bones were used in traditional medicine while its skin was used in certain rituals. Stuffed snow leopards or their skins were kept in monasteries as an offering to the deities and in some cases, to enhance their power. Snow leopard fur was also traded locally, nationally and internationally. For instance, (Doughty, 1901, p. 226), wrote:

“Leopards are scarce in the valley, the snow leopard (ounce) almost unknown … Somewhere beyond the limits of Kashmir their skin is very handsome and makes a beautiful trophy.”

Utilitarian values were closely followed by ecologistic values (23.8%), which focused largely on observations about its behavior and ecology. For example, the snow leopard was referred to by different names such as jatpo (one who stalks), salapo (one who eats grass—not uncommon among felines), shengan (used to refer to old individuals), and nama perka (animal with a stick-like tail). Interviewees also believed that it was addicted to the blood of its prey and got a high after killing it and consuming the blood.

Some of the narratives comprised negative affective (19%), negative symbolic (16.6%), positive affective (4.7%), positive symbolic (4.7%) and neutral values (2.3%). An example of positive symbolism was contained in statements like, “Killing a snow leopard is a sin. Even if you light butter lamps [for atonement] equivalent to the number of hairs on its body, you won’t be able to overcome the bad karma.”

A popular local legend described an encounter of a meditator with the snow leopard as follows:

“Once a yogi was meditating in a cave for several years. At the end of his meditation the deity he was praying to manifested itself in the form of a snow leopard. He fed the animal as an act of kindness not knowing that he was, in fact, offering food to the deity. The next day, the snow leopard rewarded his kindness by leaving a freshly killed ungulate at the entrance of his cave.”

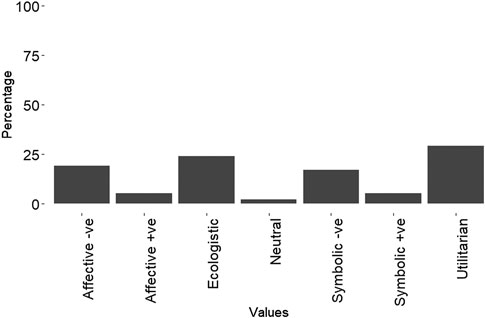

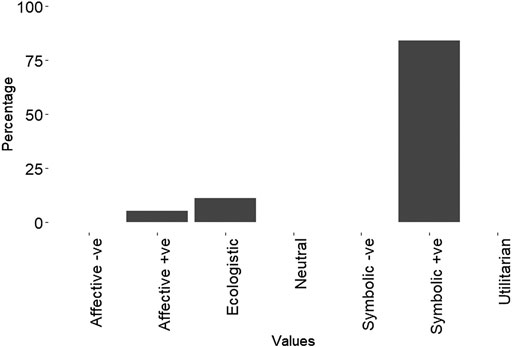

The mythical snow lion was predominantly associated with positive symbolic values (84.2%) (Figure 6). Most of these narratives discussed how the snow lion represented desirable cultural values such as fearlessness, pride, strength, etc. Positive symbolism was followed by ecologistic (10.5%) and positive affective values (5.2%)

FIGURE 6. The mythical snow lion was predominantly linked to positive symbolism (84.2%), which associated the animal with positive cultural beliefs and values, followed by ecologistic (10.5%) and positive affective values (5.2%). The total number of narratives was 19.

A prominent Buddhist leader told us that the snow lion was the undisputed king of the animal world. He explained that people would often liken strong, famous or courageous men to the snow lion. The snow lion is believed to confer good fortune on the country of its residence (Aggarwal, 2004). Referring to the good fortune one of our interviewees said, “Where there is snow lion thunder [that is, calamity] cannot occur.”

References to the snow lion were common in folk songs:

“See how many good dreams there now are.

See how many good dreams of good days there now are.

See boy, yon beloved snow mountain.

See upon that snow mountain a great lion proudly posing.”

–Dinnerstein (2013, p. 212)

In another one:

“In the dark blue sky

There are thousands of stars

In the dark blue sky

There are thousands of stars.

‘When Venus rises

I am happy

When Venus rises

Silver breaks over the palace

‘On the high mountain ice

There are thousands of lions

When the Sun, the Father of the lions rises

Gold breaks over the palace.”

–Harvey (1983, p.101)

Examining folklore to understand the diversity of values associated with wildlife can enable conservation practitioners to identify areas where societal or individual motivations are complementary to biodiversity conservation, and the areas where motivations contrast with the goals of conservation. Such knowledge can be useful in designing culturally meaningful strategies to facilitate human-wildlife coexistence.

With this aim, we sought to explore Ladakhi folklore to understand the values that were ascribed to three high altitude mammals, the ibex and its predators, the wolf and the snow leopard. We found that the values associated with all the wild animals were complex, contradictory and diverse as has been reported in Mapuche and Chilean narratives around the puma and the kodkod cat (Herrmann et al., 2013). One of the cross-cutting themes was the association of all four animals (including the mythical snow lion) with protective deities, indicating varying levels of sacredness. The second prominent theme was the tangible and intangible benefits that some of the animals offered to humans. For example, in the case of the ibex, even though people traditionally hunted them for sport (like most ungulates), their utility was not limited to trophies alone but also linked to several economic and cultural dimensions (Nordbø et al., 2018).

We had expected that narratives about carnivores would most frequently be associated with negativism owing to their preying on livestock. We found that the wolf was, indeed, frequently associated with negative values as has been reported elsewhere in Europe and North America (Kellert, 1985; Skogen and Krange, 2003). Attitudes and behaviors toward wolves are also negative in other parts of the world, which have been attributed to negative stereotyping in folk legends and myths (Kellert, 1985; Suryawanshi et al., 2013; Sponarski et al., 2014; Suryawanshi et al., 2014; Ali et al., 2016; Treves et al., 2017; Vucetich et al., 2017). Negative responses toward the wolf can partly be explained by their ecology and behavior (Kellert et al., 1996). Wolves hunt in packs and communicate by howling which can cause people to be afraid as opposed to the mostly silent and solitary snow leopard. Nonetheless, although infrequent, the values associated with the wolf were not limited to a single (negative) dimension but also reflected some positive values, especially its associations with the deities. Similar results have been reported for wolves in Mongolia (LeGrys, 2009).

Narratives about the snow leopard also ranged from reflecting its negative impacts on people to its utility to them. Its local names reflected knowledge of natural history. For example, in relation to body size, the snow leopard has one of the longest tails among the Felidae Family, with the head to body length of an adult ranging from 1 to 1.3 m and tail length of about 0.8–1 m, that is 75–90% of the head to body size (Hemmer, 1972), presumably explaining one of its local names nama perka (animal with a stick-like tail). Despite the diversity of values, however, any potentially positive symbolic associations with the two carnivores appeared to be overshadowed by negative sentiments because of their tendency to prey on livestock, unlike in the case of the snow lion. The snow leopard seemed to have resemblance to the imaginary snow lion, because of the similarity in their appearance (bushy tail, camouflaged coat) and behavior (carnivorous, surviving in the snow). However, in the absence of the negative impacts or sentiments that are typically associated with the snow leopard, the snow lion appeared to be a greatly revered carnivore associated with high levels of positive symbolism.

Our findings have potential consequences for conservation. A value-based approach can enable conservation interventions to be more culturally sensitive. The positive narratives about wildlife can provide a starting point to enhance conservation messaging and outreach, while the negative ones can be used to initiate a dialogue with local communities. For instance, the lion guardian model in Maasai Mara encourages young Maasai men who traditionally engaged in lion hunting (now outlawed) to protect the lions instead of killing them (Dickman et al., 2015; Hazzah et al., 2017). This has enabled local people to take ownership of wildlife whilst being mindful of alternative conservation values and the legal implications of hunting.

Fernández-Llamazares and Cabeza (2017) similarly highlighted many examples of how local cultural values have been incorporated into conservation. One of their examples discussed how a local visitor center in Pilón Lajas Biosphere Reserve and Indigenous Territory (Bolivia) co-produced an exhibition along with local communities to introduce visitors to the traditional myths of the Tsimané Indigenous Peoples living in the Reserve. Another example described how a 10-part radio series titled “Echoes of the Forest” interwove scientific and cultural aspects of lemur conservation around Ranomafana National Park (Madagascar). Yet another example referred to a project involved young local Daasanach in and around Sibiloi National Park (Kenya) who were encouraged to document traditional knowledge about wildlife from their elders.

The tradition and the significance of oral storytelling is eroding rapidly in Ladakh and across the high Himalaya (Norberg-Hodge, 1991; Claus et al., 2010; Dinnerstein, 2013). By employing storytelling as a tool, conservation practitioners can assist in restoring this tradition, whilst enhancing human-wildlife coexistence. The findings of this study can be further refined by accounting for demographic differences as well as longitudinal comparisons.

In his classic essay, White (1967) remarked, “What people do about their ecology depends on what they think about themselves in relation to things around them.” (p. 1,205). People’s relationship with nature is an integral part of their identity and experience (Chan et al., 2016). It is, therefore, important to find a common ground between cultural and natural heritage conservation. This can enable us to design interventions that communities believe in and can contribute to, which can also benefit wild animals in the long run.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Board at the Nature Conservation Foundation. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

SB and CM conceived the ideas and designed the methodology; SB and SN collected the data; SB analysed the data and led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Wildlife Conservation Network, Royal Bank of Scotland, Whitley-Segré Foundation supported field work.

Frontiers Media SA remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors are grateful to Wildlife Conservation Network, Royal Bank of Scotland and Whitley-Segré Foundation for their support. We also acknowledge the inputs and sound advice provided by Mahesh Rangarajan, Vasudha Pandey, Savyaasachi, Viraf Mehta, Janet Rizvi, Sudha Vasan, Valmik Thapar, Sonam Wangchuk, Tashi Ldawa, Dorjay Gyalson, Tashi Morup, Prem Singh Jina, Nazir Ali, Thupstan Dawa, Stanzin Norboo, Sahila Kudalkar, Malavika Narayana, Rigzin Dorje, Karma Sonam, Urgain Uddiyana, Stanzin Dorjay, Tsewang Namgail, Sonam Phuntsog, Late Haji Abdul Hassan at various stages of the research. The authors are grateful to all the interviewees for their time and generosity. This study is part of the corresponding author’s PhD Thesis.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2021.595169/full#supplementary-material.

Aas, L. R. (2008). Rock Carvings of Taru Thang. The mountain goat: a religious and social symbol of the Dardic speaking people of the Trans–Himalayas. Master’s Dissertation. Bergen, Norway: The University of Bergen.

Aggarwal, R. (2004). Beyond lines of control: performance and politics on the disputed border of Ladakh. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Ali, U., Minhas, R. A., Awan, M. S., AhmedKB, Qamar, Q. Z., and Dar, N. I. (2016). Human–grey wolf (Canis lupus Linnaeus, 1758) conflict in shounther valley, district neelum, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. Pakistan J. Zool. 48 (3), 861–868.

Athreya, V., Pimpale, S., Borkar, A. S., Surve, N., Chakravaty, S., Ghosalkar, M., et al. (2018). Monsters or Gods? Narratives of large cat worship in western India. Cat. News 67, 23–27.

Baker, L. R., Olubode, O. S., Tanimola, A. A., and Garshelis, D. L. (2014). Role of local culture, religion, and human attitudes in the conservation of sacred populations of a threatened “pest” species. Biodivers. Conserv. 23, 1895–1909. doi:10.1007/s10531-014-0694-6

Bhatia, S., Redpath, S. M., Suryawanshi, K., and Mishra, C. (2019). Beyond conflict: exploring the spectrum of human-wildlife interactions and their underlying mechanisms. Oryx 54 (5), 621–628. doi:10.1017/s003060531800159x

Bhatia, S., Redpath, S. M., Suryawanshi, K., and Mishra, C. (2017). The relationship between religion and attitudes toward large carnivores in northern India? Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 22 (1), 30–42. doi:10.1080/10871209.2016.1220034

Bhatia, S., Suryawanshi, K., Redpath, S. M., and Mishra, C. (2020). Understanding people’s responses toward predators in the Indian Himalaya. Anim. Conserv. doi:10.1111/acv.12647

Bray, J. (2007). “Old religions, new identities and conflicting values in Ladakh,” in International conference on religion, conflict and development, Passau, Germany, June, 2007: University of Passau.

Chan, K. M., Balvanera, P., Benessaiah, K., Chapman, M., Díaz, S., Gómez-Baggethun, E., et al. (2016). Opinion: why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 (6), 1462–1465. doi:10.1073/pnas.1525002113

Dickman, A., Johnson, P. J., Van Kesteren, F., and Macdonald, D. W. (2015). The moral basis for conservation: how is it affected by culture? Front. Ecol. Environ. 13 (6), 325–331. doi:10.1890/140056

Dinnerstein, N. (2013). Ladakhi traditional songs: a cultural musical and literary study. Ph.D thesis. New York, NY: The City University of New York.

Dollfus, P. (1997). “Mountain deities among the nomadic community of Kharnak (eastern Ladakh),” in Ladakh: culture, history, development between Himalaya and karakorum. Editors M. van Beek, K. B. Bertelsen, and P. Pedersen (Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press), 92–118.

Fernández-Llamazares, Á., and Cabeza, M. (2018). Rediscovering the potential of indigenous storytelling for conservation practice. Conserv. Lett. 11 (3), e12398. doi:10.1111/conl.12398

Fischer, J. L. (1963). The sociopsychological analysis of folktales. Curr. Anthropol. 4 (3), 235–295. doi:10.1086/200373

Fox, C. H., and Bekoff, M. (2011). Integrating values and ethics into wildlife policy and management-Lessons from North America, Animals (Basel) 1, 126–143. doi:10.3390/ani1010126

Francke, H. (1907). A history of western Tibet: one of the unknown empires. New Delhi, India: Asian Educational Services.

Francke, H., Ribbach, S., and Shawe, E. (1899). Ladakhi songs (first series). Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing.

Gupta, R. (2012). The importance of being Ladakhi—affect and artifice in Kargil. Himalaya 32 (1), 43–50. doi:10.1097/iae.0b013e3182278c41

Harvey, A. (1983). A journey in Ladakh: encounters with Buddhism. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishers.

Hazzah, L., Bath, A., Dolrenry, S., Dickman, A., and Frank, L. (2017). From attitudes to actions: predictors of lion killing by Maasai warriors. PloS One 12 (1), e0170796. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170796

Herrmann, T. M., Schüttler, E., Benavides, P., Gálvez, N., Söhn, L., and Palomo, N. (2013). Values, animal symbolism, and human-animal relationships associated to two threatened felids in Mapuche and Chilean local narratives. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 9, 41–15. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-9-41

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s consequences: international differences in work–related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publishers.

Hughes, C., Frank, B., Melnycky, N. A., Yarmey, N. T., and Glikman, J. A. (2020). From worship to subjugation: understanding stories about bears to inform conservation efforts. Ursus 31e15, 1–12. doi:10.2192/URSUS-D-19-00002.2

Hunt, D. (2008). The face of the wolf is blessed, or is it? Diverging perceptions of the wolf. Folklore 119 (3), 319–334. doi:10.1080/00155870802352269

Jackson, R., Mishra, C., McCarthy, T., and Ale, S. (2010). Snow leopards: conflicts and conservation. Biology and conservation of wild felids. Editors D. W. Macdonald, and A. J. Loveridge (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press), 417–430.

Kellert, S. R. (1995). in Concepts of nature east and west. Reinventing nature? Responses to postmodern deconstruction. Editors M. Soulé, and G. Lease (San Francisco, CA: Island Press), 103–121.

Kellert, S. R., Black, M., Rush, C. R., and Bath, A. J. (1996). Human culture and large carnivore conservation in North America. Conserv. Biol. 10 (4), 977–990. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10040977.x

Kellert, S. R. (1985). Public perceptions of predators, particularly the wolf and coyote. Biol. Conserv. 31 (2), 167–189. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(85)90047-3

Knight, J. (1999). Monkeys on the move: the natural symbolism of people-macaque conflict in Japan. J. Asian Stud. 58 (3), 622–647. doi:10.2307/2659114

Kressing, F. (2003). The increase of shamans in contemporary Ladakh some preliminary observations. Asian Folklore Stud. 62 (1), 1–23.

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

LeGrys, S. (2009). Grey to green: the wolf as culture and profit in Mongolia and the importance of its survival. SIT Digital Collections, 800.

Levi-Strauss, C. (1963). Structural anthropology. Harmondsworth. London, United Kingdom: Penguin Books.

Mishra, C., and Suryawanshi, K. R. (2014). in Managing conflicts over livestock depredation by large carnivores in successful management strategies and practice in human-wildlife conflict in the mountains of SAARC region. Editor B. Thimphu (Thimphu, Bhutan, SAARC Forestry Centre), 27–47.

Naderifar, M., Goli, H., and Ghaljaie, F. (2017). Snowball sampling: a purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides in Development of Medical Education 14 (3), 1–6. doi:10.5812/sdme.67670

Norberg–Hodge, H. (1991). Ancient futures: lessons from Ladakh for a globalizing world. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books.

Nordbø, I., Turdumambetov, B., and Gulcan, B. (2018). Local opinions on trophy hunting in Kyrgyzstan. J. Sustain. Tourism 26 (1), 68–84. doi:10.1080/09669582.2017.1319843

Redpath, S., Bhatia, S., and Young, J. (2014). Tilting at wildlife—reconsidering human-wildlife conflict. Oryx 49, 2. doi:10.1017/s0030605314000799

Rizvi, J. (1999). Ladakh: crossroads of high Asia. 2nd Edn. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Saraswat, R., Sinha, A., and Radhakrishna, S. (2015). A god becomes a pest? Human-Rhesus macaque interactions in Himachal Pradesh, northern India. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 61 (3), 435–443. doi:10.1007/s10344-015-0913-9

Schwartz, S. H. (1999). A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Appl. Psychol. 48 (1), 23–47. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.1999.tb00047.x

Sheikh, A. G. (2010). Reflections on Ladakh, Tibet and central Asia. New Delhi, India: LadakhInamullah Abdulmatin.

Skogen, K., and Krange, O. (2003). A wolf at the gate: the anti-carnivore alliance and the symbolic construction of community. Sociol. Rural. 43 (3), 309–325. doi:10.1111/1467-9523.00247

Sponarski, C. C., Vaske, J. J., Bath, A. J., and Musiani, M. M. (2014). Salient values, social trust, and attitudes toward wolf management in south-western Alberta, Canada. Environ. Conserv. 41 (4), 303–310. doi:10.1017/s0376892913000593

Suryawanshi, K. R., Bhatia, S., Bhatnagar, Y. V., Redpath, S., and Mishra, C. (2014). Multiscale factors affecting human attitudes toward snow leopards and wolves. Conserv. Biol. 28 (6), 1657–1666. doi:10.1111/cobi.12320

Suryawanshi, K. R., Bhatnagar, Y. V., Redpath, S., and Mishra, C. (2013). People, predators and perceptions: patterns of livestock depredation by snow leopards and wolves. J. Appl. Ecol. 50 (3), 550–560. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12061

Tapper, R. (1988). in Animality, humanity, morality, society in what is an Animal? Editor T. Ingold (London, United Kingdom: Unwin Hayman), 47–62.

Treves, A., Langenberg, J. A., López-Bao, J. V., and Rabenhorst, M. F. (2017). Gray wolf mortality patterns in Wisconsin from 1979 to 2012. J. Mammal. 98 (1), 17–32. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyw145

Turner, C. A., Chan, K. M., and Satterfield, T. (2010). in The roles of people in conservation in Conservation Biology for All. Editors N. S. Sodhi, and P. R. Ehrlich (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford Scholarship Online), 262–281.

Vucetich, J. A., Bruskotter, J. T., Nelson, M. P., Peterson, R. O., and Bump, J. K. (2017). Evaluating the principles of wildlife conservation: a case study of wolf (Canis lupus) hunting in Michigan, United States. J. Mammal. 98 (1), 53–64. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyw151

Walsh, M. T., and Goldman, H. V. (2007). in Killing the king: the demonization and extermination of the zanzibar leopard in animal symbolism: animals, keystone in the relationship between man and nature. Editors D. Edmond, M. E. Florac, and M. Dunham (Paris, france: IRD), 1133–1186.

White, L. (1967). The historical roots of our ecologic crisis. Science 155 (3767), 1203–1207. doi:10.1126/science.155.3767.1203

Keywords: attitudes, culture, human-wildlife, narrative, stories, storytelling

Citation: Bhatia S, Suryawanshi K, Redpath SM, Namgail S and Mishra C (2021) Understanding People’s Relationship With Wildlife in Trans-Himalayan Folklore. Front. Environ. Sci. 9:595169. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2021.595169

Received: 15 August 2020; Accepted: 08 January 2021;

Published: 25 February 2021.

Edited by:

Sumeet Gulati, University of British Columbia, CanadaReviewed by:

Helina Jolly, University of British Columbia, CanadaCopyright © 2021 Bhatia, Suryawanshi, Redpath, Namgail and Mishra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Saloni Bhatia, c2Fsb25pODZAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.