94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Environ. Sci. , 13 November 2018

Sec. Agroecology

Volume 6 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2018.00132

The predominant cropping system and management practices play an important role in soil physico-chemical properties and microbiome composition and diversity. This study analyzed the changes in soil fertility and the microbial community in four soybean-based cropping systems over 12 years. Amplification subsequencing techniques were used to compare soil community structures among the systems and identify significant positive and negative fertility factors. Soybean cropping favored the accumulation of OM and the available N, K DTPA Fe, Mn, Zn and Cu contents in soil but not fixed available P. The WS and CS cropping systems were conducive to the fixed available P, but they consumed OM, DTPA K, and Zn. The SC exhibited the lowest soil bacterial and archaeal abundance and diversity but high fungal abundance and diversity. The dominant Proteobacteria in the SC were significantly positively correlated with soil DTPA Fe and Mn. The dominant Actinobacteria were positively correlated with available P, DTPA Cu and Mn. The FS cropping system contained 764 unique bacterial species, 724 unique fungal species and the highest relative abundance of Protista. The FS had high microbial diversity, with high relative abundances of Bacteroidetes and Zygomycota and a significantly lower relative abundance of Actinobacteria. The Bacteroidetes were significantly correlated with available N, OM and DTPA Fe and negatively correlated with available P and DTPA Cu. Zygomycota was negatively correlated with available P and DTPA Cu. In the CS and WS, the soil bacterial abundance and diversity were moderate. The dominant Acidobacteria was significantly negatively correlated with soil DTPA, Fe and Mn. The CS exhibited the lowest fungal abundance and diversity. Furthermore, the relative abundance of Ascomycota was significantly improved in the WS and significantly positively correlated with available P and DTPA Cu. Decreases in the available P, K, DTPA Cu, and Mn of Vertisols greatly affect microbial community structure, and these nutrients regulate bacterial and fungal abundance and diversity. Compared to the SC, the FS, WS, and CS had more balanced soil fertility and microbial stability, but diverse cropping systems are most conducive to soil productivity. These findings are of great relevance for protecting the ecological environment.

The microbial community in soil drives important nutrient cycling processes that can influence the soil nutritional profile, crop productivity, and environmental sustainability. Agricultural management affects the chemical, physical, and biological processes in the soil and triggers many changes in the microbial community structure (Fierer et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2016). The abnormal accumulation or excessive consumption of soil nutrients can result in the rapid multiplication of pathogenic microorganisms, imbalances in the soil microbial population structure, and decreased crop yield and quality (Xing et al., 2011).

Continuous monocultures reduce soil microbial biodiversity and alter the microbial community structure, which decreases its buffering capability to tolerate biotic and abiotic stress, thus increasing the incidence of disease and subsequently affecting plant health (Wang et al., 2011; Mo et al., 2016; Xiong et al., 2016). Continuous cropping could reduce the quantity of bacteria in the soil and increase the relative proportion of fungi. Soil fungal diversity was found to be a good and sensitive indicator of soil fertility (Hobbs et al., 2008; Fierer et al., 2012). Reduced tillage is a sustainable plant management system that can lead to increased surface microbial activity and biomass and protect soil, water, and air quality as well as biodiversity (Tian et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Benitez et al., 2017). Anaerobic bacteria, such as Clostridia and other dominant anaerobic methane-producing archaea, were found in only no-till systems (Luo et al., 2016). However, crop rotation can also modify soil mass and fertility factors and thus influence microbial community structure (Benitez et al., 2017). Microbial diversity is reportedly higher in plots in which oat and maize are grown (Fierer et al., 2012). The rotation of corn and soybeans was found to have a great effect on the microbial community structure of rhizosphere soil microbial groups, with greater impacts being observed on fungi than on bacteria (Benitez et al., 2017). In a plant system containing soy, combining the appropriate crop management techniques is necessary for sustainable production (Fierer et al., 2009). Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, and Actinobacteria were the main phyla in soybean continuous cropping (SC), soybean-corn, and corn-soybean rotation systems in all soil samples across succession. With the accumulation of soil organic matter (OM) and nutrients, the relative abundance of Actinobacteria decreased, while the relative abundance of Proteobacteria increased (Zeng et al., 2017).

Lu et al. (2011) found that increasing the crop rotation of legumes could release nutrients more quickly, leading to higher nitrogen (N) and potassium (K) contents and lower available phosphorus (P) content. Fierer et al. (2009) found that the P, total N, and mineral N contents were significantly improved on the soil surface by no-tillage management systems relative to traditional farming. Rotation could also increase the amount of OM and N in soil, and increasing N enriches the bacterial microorganism composition. In previous studies, microbial communities were significantly correlated with the OM and available N, and external carbon (C), and N additions to a system significantly influenced the microbial community structure (Fierer et al., 2012). However, research on the interactions among different cropping systems, soil fertility and microbial communities, especially on the effects of mineral elements on microbial communities in soil, is rare. Thus, the potential biological control of crop plants is of great relevance for reducing the amount of fertilizer used (Cai et al., 2015).

High-throughput sequencing provides a useful means to understand the soil microbial community structure and microbial diversity. The microbial community structure is influenced by the physical and chemical properties of the soil (Xun et al., 2015; Cai et al., 2017) as well as by the species and even the genotype of the host plant (Ofek et al., 2014). Heilongjiang Province is the main soybean production area in northern China. From 1999 to 2016, the average soybean production accounted for 36.21% of the national average, while Nenjiang is the main production area in Heilongjiang Province. Therefore, in this study, high-throughput sequencing (i.e., Illumina MiSeq) was conducted to analyze the microorganism community structure and diversity as well as the interactions of the community with soil nutritional profiling under different cropping systems, i.e., the fallow-soybean cropping system (FS), corn-soybean rotation cropping system (CS), wheat-soybean rotation cropping system (WS), and soybean continuous cropping system (SC), across multiple years. The objectives were to (1) identify the appropriate cropping system for maintaining soil fertility, (2) determine the appropriate agricultural cropping system for protecting the soil microbial community, and (3) identify how to enhance the microbial community structure according to the nutritional preferences under different cropping systems. The results of this work will provide a foundation for the regulation of soil nutritional profiling and microorganism community structure, guide cropping system decisions, and protect soil ecology.

This study was based on soil samples collected during a 12-year experiment conducted in the experimental ground of the 5th squadron of the fourth field of the Nenjiang River in northern China, known as China's soybean country. The soil type belongs to the Vertisol class according to the American soil classification system (Soil Survey Staff, 2014). This site has a temperate monsoon climate and the following geographical coordinates: 125°41′ E longitude and 49° N latitude. The local annual mean temperature is 0.8 to 1.4°C, and the average rainfall is 480 to 512 mm. The winter is cold, long, and dry, with a minimum temperature of −47.3 to −43.7°C. The summer is hot and rainy, with a maximum temperature of 33.9 to 37.4°C. The soil is classified as black, and the region is the main production area of wheat and soybean in China.

Soybean was planted in experimental plots before March 2005, and rotation trials began in April 2005. Four cropping systems were arranged in a randomized block design: fallow-soybean cropping system (FS), corn-soybean rotation cropping system (CS), wheat-soybean rotation cropping system (WS), and soybean continuous cropping system (SC). Each year, the dosage of ammonium phosphate was 349.5 kg ha−1, the dosage of urea was 199.5 kg ha−1, and the dosage of K phosphate was 199.5 kg ha−1. The cropping lasted for 12 years. Soil samples were collected after the cropping of soybeans in 2016.

Soil samples were collected at seven different sampling points per plot. The soil cores were obtained using a 5-cm-diameter soil auger that collected soil between depths of 0 and 20 cm. The cores were removed by hand and separated into two parts. One part was air dried and sieved through a 2-mm sieve for soil fertility analysis, while the second part was stored at −80°C for DNA extraction.

Soil samples were dried at room temperature and ground into pieces (that passed through a 0.2-mm sieve). The soil micronutrients Fe, Mn, Zn, and Cu were extracted with diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) followed by determination by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (Lindsay and Norvell, 1978). Available boron (B) was determined by K imine colorimetry (Malekani and Cresser, 1998), and the pH was measured at a soil-to-water ratio of 2.5:1. Soil organic C was determined following wet digestion (Walkley and Black, 1934), and the values were multiplied by a factor of 1.724 to obtain OM values. The basic N solution was determined using the diffusion method (Bremner and Keeney, 1966), and available P was determined using the 0.5 mol. L−1 NaHCO3 leaching-molybdenum antimony colorimetric method (Föhse et al., 1991). Available K was measured with the 1 mol. L−1 NH4OAc extraction-flame photometric method (Petersen and Corey, 1966).

Total DNA was extracted using the MoBio PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the recommended protocol. The concentration and purity of the DNA were determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer, and the DNA integrity was determined using 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. The primers 515F (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGG-3′) and 907R (5′-CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGTTT-3′) were used to amplify the V4-V5 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene. The primers ITS1F (5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′) and ITS1R (5′- GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′) were used to amplify the fungal internal transcribed spacer (ITS1) region. A parallel amplification of E. coli/yeast genomic DNA served as the positive control, and sterile water was used as the negative control. Each sample was independently amplified three times. Finally, the PCR products were evaluated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and PCR products from the same sample were pooled. The pooled PCR product was used as a template, and index PCR was performed using index primers to add the Illumina index to the library. The amplification products were evaluated using gel electrophoresis and purified using the Agencourt AMPure XP Kit (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA). The purified products were indexed in the 16S V4-V5 or ITS1 library. The library quality was assessed on the Qubit@2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific) and Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 systems. Finally, the pooled library was sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq 250 Sequencer, generating 2 × 250 bp paired-end reads (Zhu et al., 2016).

Fastx was used to remove bases with end masses lower than Q15; the paired sequences obtained by double-end sequencing were merged into a longer sequence by FLASH in an overlapping relationship; and the obtained splicing sequence (merge) was obtained. Cutadapt software was used to delete the miscellaneous sequence at the end of the short sequence, and the resulting sequence was filtered with USEARCH software to obtain the valid sequence (Primer Filter). The singleton sequence was removed by USEARCH software, and the reference standard was compared to remove the chimeric sequence. The UPARSE clustering method was performed to merge the quality-controlled sequences (97-degree similarity between sequences) into an operational taxonomic unit (OTU) cell for subsequent OTU classification annotations (Edgar, 2013). Mothur software was used to compare the RDP, and the UNITE database was used for taxonomic analysis (Caporaso et al., 2010). All sequences were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (accession numbers SRP155104), and the quality of the raw data sequencing is shown in Supplementary Table 1. Microbial community composition and species diversity analyses were performed using Lefse in R (R Development Core Team, 2008) and with Mothur software, and regression analyses of the relationships between microorganisms and soil physico-chemical properties were performed using R (Tian et al., 2015). Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and Duncan's multiple range tests were performed with SPSS 17.0 to test the significance level (p < 0.05) of the differences among the treatments.

Analysis of the collected soil samples showed that the four cropping systems (i.e., FS, CS, WS, and SC) had significantly varied fertility characteristics (p < 0.05; Table 1). The soils of the tillage modes in SC and FS exhibited higher contents of OM, available N, and K and were thus not conducive to the accumulation of available soil P. These results indicated that soybean cultivation resulted in the accumulation of available OM, N, K, Zn, Fe, and Mn in the soil, which resulted in the overconsumption of P. FS tillage reduced the available soil Cu content and the accumulation of Mn, resulting in the loss of available P. The WS cropping system improved the soil available P and the Cu content, but it consumed greater quantities of OM, available N and Fe. The contents of available K and Zn were the lowest in CS.

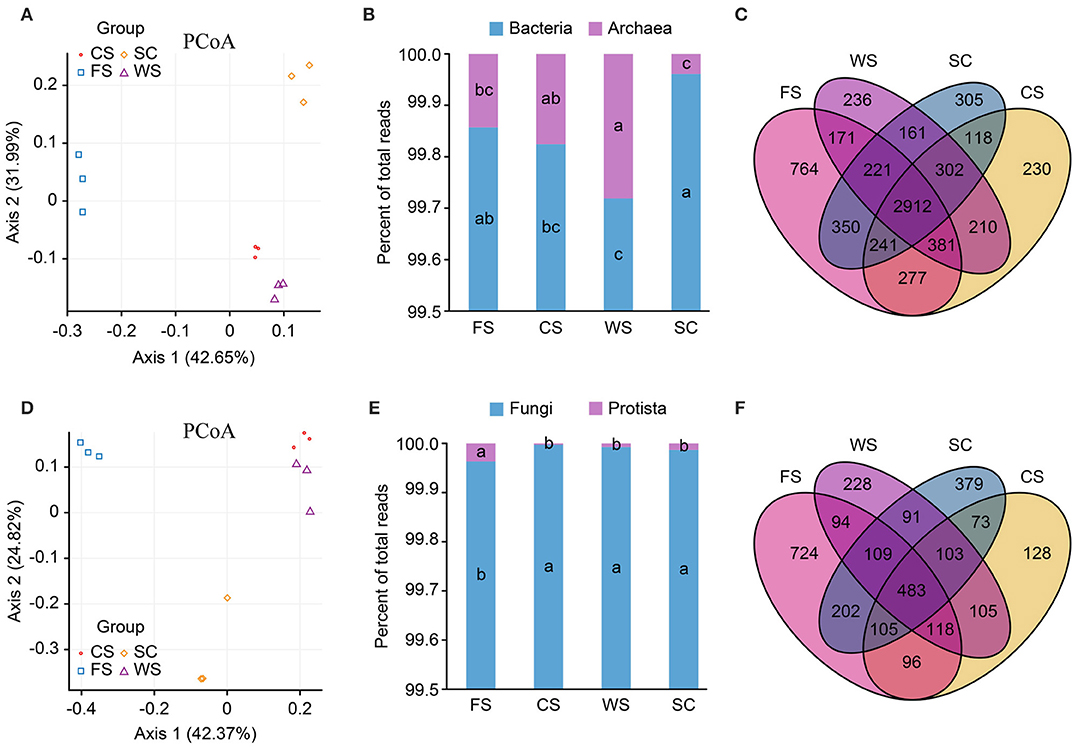

Bacterial and fungal principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) showed significant differences among the four different cropping systems, but the WS and SC colony structures were similar (Figures 1A,D). The abundance (Chao1/ACE) and diversity (Shannon) of bacteria and fungi in FS were significantly higher (p < 0.05). The diversity and abundance of soil bacteria in SC were the lowest among all the cropping systems analyzed, but the diversity of fungi was higher in SC than in the CS and WS (Table 1). The diversity of fungi in CS was the lowest among all the cropping systems analyzed (p < 0.05). The archaea in WS exhibited enhanced formation, and the lowest abundance of archaea was found in SC (p < 0.05; Figure 1B). The different cropping systems affected the formation of the soil microbial colony structure and diversity. In total, 764 unique bacterial species and 724 unique fungal species were identified in FS, and these values were much higher than those observed in the other treatments. Additionally, 305 bacterial species and 379 fungal species were processed in SC (Figures 1C,F). The FS cropping system was the most conducive to the formation of soil microbial colony diversity among all the cropping systems analyzed, especially in terms of protozoan formation (Figure 1E).

Figure 1. Microbial community structure. (A–C): bacteria. (D–F): fungi. (A,D): PCoA. (B,E): histogram. (C,F): Venn diagrams. PCoA: in the PCoA figure, a shorter distance (close) indicates that the difference between the samples in terms of the microbial community composition is small, whereas a larger difference between samples in terms of microbial community diversity is indicated by a longer distance between the samples. The more similar samples (the same sample group) will eventually converge. Histogram: relative abundance (%) of super kingdoms in the soil samples. Venn diagram: the number of species in the overlapping areas of different colors indicate the total number of species. SC, soybean continuous cropping system; FS, fallow-soybean cropping system; CS, corn-soybean rotation cropping system; and WS, wheat-soybean rotation cropping system.

The bacteria and archaea identified in this study belong to 33 phyla (classified reads = 94%), 61 classes (84%), 73 orders (56%), 164 families (50%), 385 genera (61%), and 626 species (41%). The fungi and protists identified in this study belong to 7 phyla (classified reads = 95%), 31 classes (93%), 88 orders (85%), 191 families 81%), 371 genera (74%), and 453 species (46%; Supplementary Table 2).

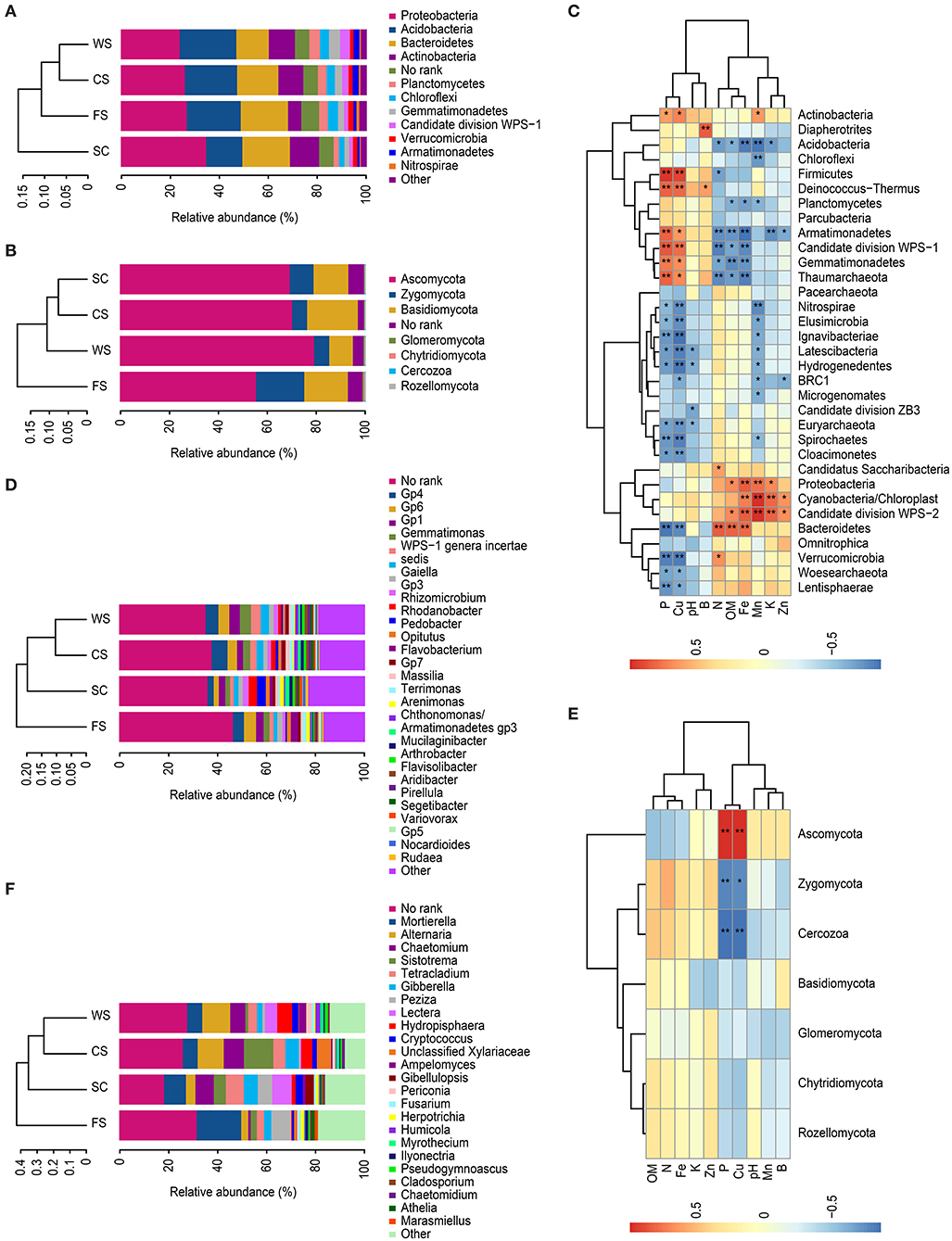

The dominant bacteria (i.e., the relative abundance) in the various soil samples were mainly distributed in Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Planctomycetes, Chloroflexi, Gemmatimonadetes, candidate division WPS-1, Verrucomicrobia, Armatimonadetes, and Nitrospirae. The differences among the microbial communities in the different cropping systems were significant. Proteobacterium was the most abundant in all samples, with a relative abundance of more than 20% of the total number of OTUs (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Analysis of microbial community abundance. (A,C,D): bacteria. (B,E,F): fungi. (A,B): histograms of the phyla. (D,F): histograms of the genera. (C,E): heat map. The histograms show the relative abundances (%) of the phyla or genera. Heat map: redundancy analysis identified ten selected soil physico-chemical variables and the microbial biomasses among the microbial communities. Each column represents a different soil physico-chemical property, each row represents a different species, and the different colors indicate the sizes of two correlation coefficients. A darker blue indicates a stronger negative correlation, whereas a more intense orange represents a greater positive correlation. *indicates significance at p < 0.05, **indicates significance at p < 0.01. SC, soybean continuous cropping system; FS, fallow-soybean cropping system; CS, corn-soybean rotation cropping system; and WS, wheat-soybean rotation cropping system.

The dominant bacteria in the SC soil had significantly more members of the phyla Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria than the other cropping systems, and significantly fewer bacteria from the phyla Acidobacteria, Planctomycetes, Gemmatimonadetes, Chloroflexi, and Nitrospirae were observed.

The dominant bacteria in WS soil included more members from the phyla Planctomycetes and Acidobacteria than in the other cropping systems, and WS had a significantly lower relative abundance of Bacteroidetes than that found in the other cropping systems. Additionally, candidate division WPS-1 was significantly higher and Verrucomicrobia was significantly lower in the WS cropping system than in the other cropping systems analyzed.

Microbial diversity was greater in the FS cropping system, which presented higher relative abundances of Chloroflexi, Verrucomicrobia, Nitrospirae, and Bacteroidetes and a significantly lower relative abundance of Actinobacteria. There was a significant percentage (7.2%) of bacteria in the “No_Rank” category in FS.

The fungi in all samples were mainly distributed in Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Zygomycota, encompassing 90% of the total samples. Fungi from Ascomycota were significantly more common in WS than in the other systems. The quantity of Basidiomycota was significantly higher in the CS cropping system than in the other cropping systems. The relative abundance of Zygomycota in FS was significantly higher (relative abundance of 19.7%) than those in the SC (9.7%) and crop rotation (6.1%) cropping systems (Figure 2B).

Proteobacteria was significantly positively correlated with the DTPA Fe and Mn contents in the soil, whereas Acidobacteria was significantly negatively correlated with these factors. Bacteroidetes was significantly correlated with the available N, OM, and Fe contents and significantly negatively correlated with the available P and DTPA Cu contents. Actinobacteria was positively correlated with the available P and DTPA Cu and Mn contents (Figure 2C).

Fungal Ascomycota was significantly correlated with the available P and DTPA Cu contents. Zygomycota and Cercozoa (Protista) were significantly negatively correlated with the available P and DTPA Cu contents (Figure 2E).

Bacteria in the Vertisol samples were mainly distributed in the Gp4, Gp6, Gemmatimonas, Gp1, Gaiella, incertae sedis WPS-1, Flavobacterium, Gp3, Rhizomicrobium, Rhodanobacter, Opitutus, and Pedobacter genera, but most bacteria were not identified at the species level (i.e., No_Rank; Figure 2D). The dominant bacteria in the Gp6 genus in FS was negatively correlated with the DTPA Fe and Mn contents. The dominant bacterial Gp4 found in the CS was negatively correlated with the available K and DTPA Zn, Fe, and Mn contents. The dominant bacteria in WS were Gemmatimonas, Gaiella, and incertae sedis WPS-1, which were significantly related to the available P and DTPA Cu contents. Gp1 was negatively related to the available N content.

The dominant bacteria Rhizomicrobium, Rhodanobacter, and Pedobacter in SC were significantly positively correlated with the available K, DTPA Mn and DTPA Fe contents (Table 2).

The relative abundance values of fungal genera varied significantly among the samples (Figure 2F). The dominant fungus Mortierella in the FS was negatively correlated with the DTPA Cu and available P contents, and the dominant fungus Peziza was significantly negatively correlated with the available P and DTPA Cu contents. Chaetomium was significantly less prominent in FS, and Chaetomium was positively correlated with the available P content. The dominant bacterium Tetracladium in SC soil was positively correlated with the DTPA Mn content. The dominant bacterium Gibberella was positively correlated with the available N content, and the dominant bacterium Lectera was positively correlated with the available K and DTPA Zn and Mn contents. In the CS and WS rotation soils, the dominant fungi Alternaria and Hydropisphaera were positively correlated with the available P and DTPA Cu contents but negatively correlated with the available N and DTPA Fe contents (Table 3).

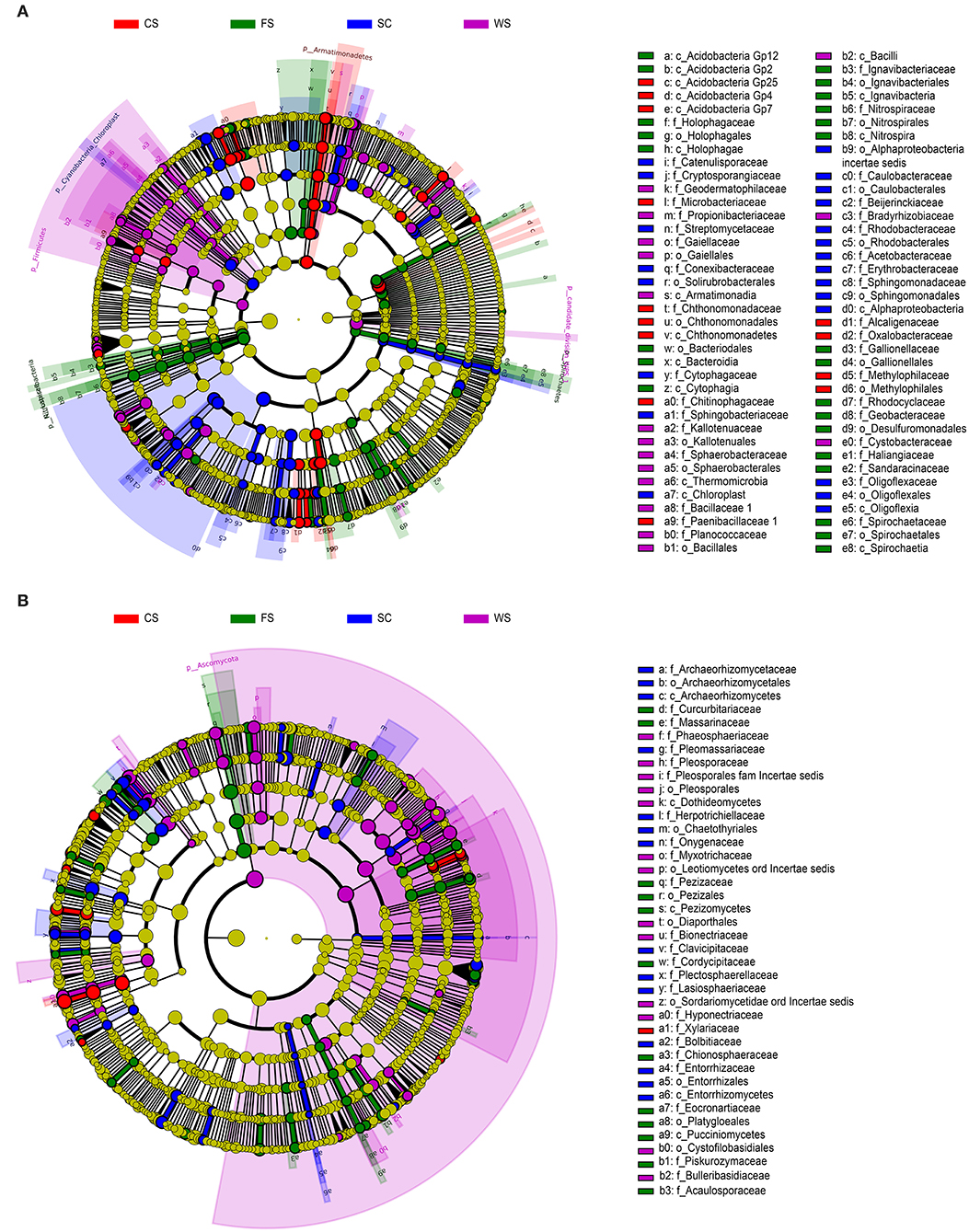

Under the different cropping systems, the genera (Figures 3A,B) that formed were distinct for the different colony structures. The Geobacter, Geothrix, and Azonexus bacteria compositions were significantly different. In FS, significant differences in fungi existed and included Eocronartium, Pluteus, Slopeiomyces, and Acaulospora. These microorganisms were significantly correlated with low available P and low DTPA Cu content in the soil.

Figure 3. Analysis of significant species. (A): bacteria. (B): fungi. (A,B): LefSe. LefSe analysis diagram: the nodes indicate that the microbiota (with significant differences from the other groups) played an important role in the group, and the yellow nodes indicate the absence of significant microbial groups in the group. The English letters in the image on the right are represented in each group and play an important role in the outline of the species name level. The names on the outer ring of the letters between groups play an important role in the door at the species name level; thus, each layer of nodes from the inside runs through the phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. Each species layer represents the process from inside extroversion to the said phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. The diameter of the node is proportional to the relative abundance. SC, soybean continuous cropping system; FS, fallow-soybean cropping system; CS, corn-soybean rotation cropping system; and WS, wheat-soybean rotation cropping system.

Microorganisms that produced significant differences in SC were mainly distributed in the bacteria Sphingobacterium, Brevundimonas, and Mucilaginibacter and in Auxarthron, the fungi Entorrhiza, unclassified Bionectriaceae, and unclassified Corticiaceae. These microorganisms were significantly associated with a high OM content, high available K content, and high DTPA Fe and Mn contents in SC soil. Microbes and physico-chemical properties have a corresponding relationship (Table 4), and soil physico-chemical property extremes (i.e., extremely high/extremely low) determine the microbial community structure.

Different cropping systems cause significant differences in soil fertility. Thus, the microbial community structure is further influenced. The microbial community structure in FS was significantly affected by the low contents of available P, DTPA Cu and Mn. The soil microbial community structure in the SC cropping system was mainly affected by high available K, DTPA Mn and Fe contents. The microbial community structure in the CS cropping system was mainly affected by low available N and OM contents and high available P and DTPA Cu contents. The soil microbial community structure in the WS cropping system was mainly affected by low available N, OM, and DTPA Fe contents and by high available P and DTPA Cu contents. The crop species and soil characteristics coopted and promoted the growth of microbial communities. The microbial community structure could be altered by regulating the variety of crops and increases and decreases in soil characteristics.

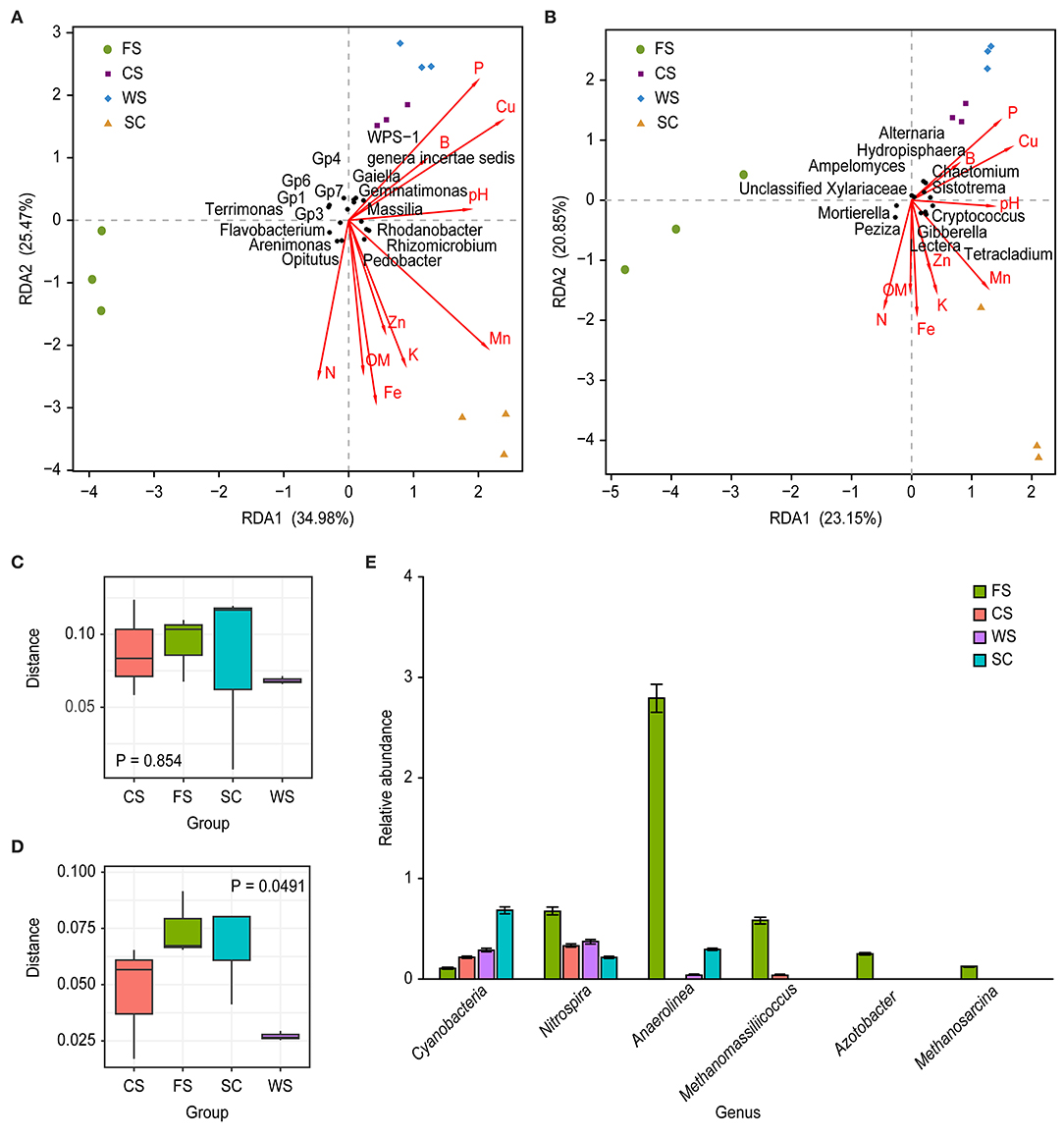

The soil microbial community is well correlated with soil physico-chemical properties (Figures 4A,B; Table 5). The bacterial microbial community was significantly correlated with the available P and DTPA Mn contents in the soil, with a correlation coefficient of 0.93; additionally, the community was correlated (0.91) with the available P, DTPA Cu and Mn contents. The effects of fungi and soil on the available P, K, and DTPA Mn contents were significant, with a correlation coefficient of 0.85 (Table 5).

Figure 4. Microbial community differences. (A,D): bacteria, (B,C): fungi. (A,B): RDA. (C,D): body figure. (E): relative abundance of genera. RDA: The image indicates multiple physico-chemical properties and a sample/microflora RDA analysis diagram. The arrows represent different physico-chemical properties. A longer ray indicates a greater influence of the soil physico-chemical properties. For each sample, the angle between the center and the arrow represents the relationship between the sample and soil physico-chemical properties (acute angles show positively correlated relationships, obtuse angles indicate negatively correlated relationships, and rectangles indicate irrelevance); the points in different colors represent different samples. The different samples are perpendicular to the arrows for different physico-chemical properties. Closer projection points indicate that the soil physico-chemical properties are more similar in the sample, and the value of the physico-chemical properties increases along the direction of the arrow. The horizontal coordinates in the above C and D images represent different cropping system, and the vertical coordinates indicate the distance between the sample groups. Blue boxes: SC; green boxes: FS; orange boxes: and CS; black boxes: WS. The P-values indicate the differences between the groups. The horizontal coordinates in the unit E graph represent different classifications. The ordinate values represent the relative abundances; the relative abundance of Cyanobacteria and Nitrospira is expressed in %, whereas the quantitative value of the relative abundance times 100 is shown for the other genera. SC, soybean continuous cropping system; FS, fallow-soybean cropping system; CS, corn-soybean rotation cropping system; and WS, wheat-soybean rotation cropping system.

The bacterial microbial communities of the different cropping systems had significant functional differences, while the functional differences in the fungal communities were not obvious (Figures 4C,D). Cyanobacteria were significantly more abundant in the SC cropping system than in the other cropping systems (Figure 4E). Additionally, a range of archaeal methanogens, such as Methanomassiliicoccus and Methanosarcina (both anaerobes of Euryarchaeota), were significantly higher in FS than in the other cropping systems. However, these groups were not detected in samples from SC and WS (Figure 4E). Azotobacter N-fixing bacteria existed in only FS, and Nitrospira and Anaerolinea were significantly more abundant in FS than in the other cropping systems. Azotobacter bacteria existed in only FS, and Nitrospira and Anaerolinea were significantly more abundant in FS than in the other cropping systems (Figure 4E).

In this study, the OM and available N contents in soil were highest in SC, which is consistent with previous results for soybean cropping (Lu et al., 2011). In addition, the study showed that SC increased the contents of available K, DTPA Zn, Fe and Mn in soil, which is consistent with previous single-cropping results (Cai et al., 2017). In the soil under the FS cropping system, the available P, DTPA Cu and Mn contents decreased significantly. In contrast, the contents of available P and DTPA Cu increased significantly in the WS soil, but the contents of available N and DTPA Fe decreased significantly. In the soil under the CS cropping system, the contents of available K and DTPA Zn were significantly lower than under other cropping systems. Thus, different cropping systems generated different soil physico-chemical properties, which is consistent with the results of previous studies (Fierer et al., 2009; Xun et al., 2015), demonstrating that the cropping system can regulate soil physico-chemical properties.

The abundance and diversity of soil microbes determine the stability of the soil microbial community and its ability to resist pathogens, which is crucial to the function and sustainable development of the soil ecosystem (Smith et al., 2008; Pang et al., 2017). In this study, the abundance of fungal microorganisms in the SC cropping system increased significantly, which is consistent with the results of Li et al. (2010). Single cropping may increase the relative abundance of fungi in the soil and increase the occurrence probability of soil-borne diseases. In this study, the FS cropping system was characterized by a more diverse microbial ecosystem, confirming that reducing agricultural cropping can increase soil microbial diversity (Wang et al., 2011). The diversity of soil bacteria in the WC and CS cropping systems was greater than that in the SC cropping system, which is consistent with previous studies (Ai et al., 2015). Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes can inhibit the occurrence of diseases (Ai et al., 2015), and Acidobacteria has the ability to break down complex soil OM and plant-derived polysaccharides (Ward et al., 2009). The dominant bacteria (i.e., the relative abundance) distributed in various samples of cold-ground Vertisols were previously found to be from Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria (Knelman et al., 2015), and the results of the present study confirmed these conclusions. Proteobacteria was the most abundant in all treatments, accounting for ~20% of the total number of OTUs (Figure 2A), and the Proteobacteria associated with symbiotic rhizobia was significantly more abundant in the SC cropping system. With the accumulation of soil OM and nutrients, the relative abundance of Proteobacteria increased (Freedman and Zak, 2015; Zeng et al., 2017). Acidobacteria was significantly less abundant in SC but significantly more abundant in the WS cropping system. Bacteroidetes was significantly higher in the FS cropping system. Actinobacteria was significantly higher in the SC cropping system but significantly lower in the FS cropping system. Janssen (2006) found that the content of Gemmatimonadetes in soil bacterial communities was 2% (Janssen, 2006), and in the present study, Gemmatimonadetes was significantly more abundant in the WS cropping system and was detected in ~0.91% of reads. We also found that Verrucomicrobia was significantly more abundant in the FS cropping system. Bergmann et al. (2011) studied undisturbed soil and found that 23% of bacterial sequences belonged to Verrucomicrobia microbes (Bergmann et al., 2011). In the present study, the bacteria phylum Chloroflexi was abundant in FS and WS and was nearly twice as abundant as that in the SC cropping system. These microbes can perform anaerobic photosynthesis and withdraw electrons from hydrogen sulfide (Eisen et al., 2002). Nitrospirae was significantly more abundant in the FS cropping system and significantly lower in SC than in the other cropping systems. Cyanobacteria were more abundant in the SC cropping system; members of this phylum can fix N gas into ammonia (), nitrite () or nitrate () as well as significantly reduce carbon aerobically (Flores, 2008).

Thaumarchaeota and a Candidatus Nitrososphaera comprise the soil -oxidizing archaea genera; is oxidized by producing ammoxase (AMO; Zhalnina et al., 2012). Thaumarchaeota was significantly more abundant in the WS cropping system. Euryarchaeota was significantly abundant in FS, and this group includes extreme halophiles, sulfate-reducing microbes and anaerobic methanogens as well as many other species (Lei et al., 2017). The genera Methanomassiliicoccus and Methanosarcina of Euryarchaeota were detected in only FS, but other Euryarchaeota were almost five times more abundant in the SC cropping system. Collectively, these data support the notion that the abundance of anaerobic microorganisms increased in the FS because of less aeration due to low soil disturbance. In addition, the OM in the FS soil maintains a certain water storage capacity, providing anaerobic habitats for anaerobic organisms (Minamisawa et al., 2004).

The fungi in all samples were mainly distributed in Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Zygomycota, which accounted for 90% of the total sampled fungi. This result confirms previous findings (Xu et al., 2012). Fungi from Ascomycota were significantly more common in the WS cropping system. The relative abundance of Basidiomycota did not significantly differ among the samples. The distribution of Zygomycota fungi was significantly greater in the FS soil, with a relative abundance of 19.7%, which was significantly higher than that under the SC (9.7%) and crop rotation (6.1%) cropping systems.

Soil fertility affects soil microbial community structure (Liu et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2016). The increased OM and N in soil could promote bacterial diversity (Shen et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016; Zeng et al., 2017). An interesting phenomenon was observed in this experiment: in the SC and FS cropping systems, the contents of OM and N were very high, but the abundance and diversity of bacteria differed significantly, indicating that the abundance and diversity of soil bacteria may be related to other factors in addition to OM and N. The diversity of fungi under SC was significantly higher than that under rotation, and Hooper et al. proposed that this might be related to the long-term accumulation of soil nutrients (Hooper et al., 2005).

In the FS cropping system, Bacteroidetes and Verrucomicrobia were significantly positively correlated with the OM content, and Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobia, and Latescibacteria were significantly negatively correlated with the available P and DTPA Cu contents. Nitrospirae was significantly negatively correlated with the available P, K, and DTPA Mn contents, and Actinobacteria was significantly positively correlated with the available P, DTPA Cu, and Mn contents. In the SC cropping system, Proteobacteria was significantly positively correlated with the available Fe and DTPA Mn contents. In the WS cropping system, Planctomycetes was negatively correlated with the DTPA Zn content. Zygomycota and Cercozoa of Protista were significantly more abundant in the FS cropping system and were significantly negatively correlated with the P and Cu contents. Ascomycota was significantly more abundant in the WS cropping system and was positively correlated with the DTPA Fe and Cu contents.

These results are inconsistent with those of Cai et al. (2017) and Pang et al. (2017), which may be due to the different types and amounts of soil samples studied. However, there was a significant correlation between the microbial community and the soil physico-chemical properties.

In this study, microbial community structure was influenced by high or low soil fertility in the soils of different cropping systems. In fact, 33 of the 40 microbial phyla were significantly positively or negatively correlated with one or several soil fertility parameters (p < 0.05). The bacterial community structure was significantly correlated with the physico-chemical properties of soil available P, DTPA Cu, and Mn. The fungal community was significantly correlated with available P, K, and DTPA Cu.

These changes in the microbial communities are related to the nutrients and plant biomass available in the soil (Bokhorst et al., 2017). Many studies have concluded that soil and physico-chemical properties shape community structure (Xun et al., 2015; Pang et al., 2017), and as confirmed experimentally, the cropping system, soil fertility, and soil microbial community structure are interrelated and can be adjusted concomitantly (Ofek et al., 2014). In the present study, the cropping system altered the soil properties and the community structure, and we found that there was no perfect cropping system. The FS, WS, and CS systems were capable of balancing soil fertility and microbial stability. Therefore, institutional diversity is most conducive to soil productivity (Kuramae et al., 2012; Yuan et al., 2015). We found that the available P, K, DTPA Cu, and Mn contents were closely related to the microorganism communities.

The cropping system affects the physical and chemical properties of soil and the microbiome structure. (1) Soybean cropping favored the accumulation of OM and the available N, K DTPA Fe, Mn, Zn, and Cu contents in soil but not fixed available P. The WS and CS cropping systems were conducive to the fixed available P, but they consumed OM, DTPA K, and Zn. (2) The FS cropping system could increase the abundance and diversity of bacteria. The SC cropping system could decrease the abundance and diversity of bacteria but increase the abundance and diversity of fungi. The WS and CS cropping systems could reduce fungal abundance and diversity. (3) There was a significant correlation between microbial community structure and the physico-chemical properties of soil, and the most significant correlation was between the bacterial community and available P, DTPA, and Mn (0.93). The fungal community was most correlated with available P, DTPA K, and Cu, with a correlation coefficient of 0.8. In summary, increasing the diversity of the cropping system was more favorable to maintaining soil fertility. The cropping system changes soil properties and microbial diversity, and the microbial community in turn manipulates nutrient cycling processes and alters soil fertility, plant productivity and environmental sustainability. The results of this study will provide a foundation for further studies on the regulation of soil fertility and microorganism community structure and provide guidance for selecting the best cropping model to protect soil ecology.

XS and BT planned and arranged the entire study. The main experiments were performed by XS. JG and JL assisted in the soil testing. XS and BT wrote the manuscript together. GC participated in further discussion. All authors discussed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This study was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Plan of China (2016YFD0200500; 2016YFD070030103).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We are grateful to the Agriculture College of Northeast Agricultural University, Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, and the numerous staff members who helped protect the test plots and collect the soil samples.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2018.00132/full#supplementary-material

Ai, C., Liang, G., Sun, J., Wang, X., He, P., Zhou, W., et al. (2015). Reduced dependence of rhizosphere microbiome on plant-derived carbon in 32-year long-term inorganic and organic fertilized soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 80, 70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.09.028

Benitez, M. S., Osborne, S. L., and Lehman, R. M. (2017). Previous crop and rotation history effects on maize seedling health and associated rhizosphere microbiome. Sci. Rep. 7:15709. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15955-9

Bergmann, G. T., Bates, S. T., Eilers, K. G., Lauber, C. L., Caporaso, J. G., Walters, W. A., et al. (2011). The under-recognized dominance of Verrucomicrobia in soil bacterial communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 43, 1450–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.03.012

Bokhorst, S., Kardol, P., Bellingham, P. J., Kooyman, R. M., Richardson, S. J., Schmidt, S., et al. (2017). Responses of communities of soil organisms and plants to soil aging at two contrasting long-term chronosequences. Soil Biol. Biochem. 106, 69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.12.014

Bremner, J. M., and Keeney, D. R. (1966). Determination and isotope-ratio analysis of different forms of nitrogen in soils: 3. exchangeable ammonium, nitrate, and nitrite by extraction-distillation methods 1. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 30, 577–582. doi: 10.2136/sssaj1966.03615995003000050015x

Cai, F., Chen, W., Wei, Z., Pang, G., Li, R., Ran, W., et al. (2015). Colonization of Trichoderma harzianum strain SQR-T037 on tomato roots and its relationship to plant growth, nutrient availability and soil microflora. Plant Soil 388, 337–350. doi: 10.1007/s11104-014-2326-z

Cai, F., Pang, G., Miao, Y., Li, R., Li, R., Shen, Q., et al. (2017). The nutrient preference of plants influences their rhizosphere microbiome. Appl. Soil Ecol. 110, 146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.11.006

Caporaso, J. G., Kuczynski, J., Stombaugh, J., Bittinger, K., Bushman, F. D, Costello, E. K., et al. (2010). QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303

Edgar, R. C. (2013). UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604

Eisen, J. A., Nelson, K. E., Paulsen, I. T., Heidelberg, J. F., Wu, M., Dodson, R. J., et al. (2002). The complete genome sequence of Chlorobium tepidum TLS, a photosynthetic, anaerobic, green-sulfur bacterium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 9509–9514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132181499

Fierer, N., Lauber, C. L., Ramirez, K. S., Zaneveld, J., Bradford, M. A., and Knight, R. (2012). Comparative metagenomic, phylogenetic and physiological analyses of soil microbial communities across nitrogen gradients. ISME J. 6, 1007–1017. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.159

Fierer, N., Strickland, M. S., Liptzin, D., Bradford, M. A., and Cleveland, C. C. (2009). Global patterns in belowground communities. Ecol. Lett. 12, 1238–1249. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01360.x

Flores, F. G. (2008). The Cyanobacteria: Molecular Biology, Genomics, and Evolution. Norwich: Horizon Scientific Press.

Föhse, D., Claassen, N., and Jungk, A. (1991). Phosphorus efficiency of plants. Plant Soil 132, 261–272. doi: 10.1007/BF00010407

Freedman, Z., and Zak, D. R. (2015). Soil bacterial communities are shaped by temporal and environmental filtering: evidence from a long-term chronosequence. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 3208–3218. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12762

Hobbs, P. R., Sayre, K., and Gupta, R. (2008). The role of conservation agriculture in sustainable agriculture. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363, 543–555. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2169

Hooper, D. U., Chapin, F. S., Ewel, J. J., Hector, A., Inchausti, P., Lavorel, S., et al. (2005). Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: a consensus of current knowledge. Ecol. Monogr. 75, 3–35. doi: 10.1890/04-0922

Janssen, P. H. (2006). Identifying the dominant soil bacterial taxa in libraries of 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1719–1728. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.3.1719-1728.2006

Knelman, J. E., Graham, E. B., Trahan, N. A., Schmidt, S. K., and Nemergut, D. R. (2015). Fire severity shapes plant colonization effects on bacterial community structure, microbial biomass, and soil enzyme activity in secondary succession of a burned forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 90, 161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.08.004

Kuramae, E. E., Yergeau, E., Wong, L. C., Pijl, A. S., Veen, J. A., and Kowalchuk, G. A. (2012). Soil characteristics more strongly influence soil bacterial communities than land-use type. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 79, 12–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01192.x

Lei, Y., Xiao, Y., Li, L., Jiang, C., Zu, C., Li, T., et al. (2017). Impact of tillage practices on soil bacterial diversity and composition under the tobacco-rice rotation in China. J. Microbiol. 55, 349–356. doi: 10.1007/s12275-017-6242-9

Li, C., Li, X., Kong, W., Wu, Y., and Wang, J. (2010). Effect of monoculture soybean on soil microbial community in the Northeast China. Plant Soil 330, 423–433. doi: 10.1007/s11104-009-0216-6

Li, R., Shen, Z., Sun, L., Zhang, R., Fu, L., Deng, X., et al. (2016). Novel soil fumigation method for suppressing cucumber Fusarium wilt disease associated with soil microflora alterations. Appl. Soil Ecol. 101, 28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.01.004

Lindsay, W. L., and Norvell, W. L. (1978). Development of DTPA soil test for zinc, iron, manganese and copper. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 42, 421–428. doi: 10.2136/sssaj1978.03615995004200030009x

Liu, J., Sui, Y., Yu, Z., Shi, Y., Chu, H., Jin, J., et al. (2014). High throughput sequencing analysis of biogeographical distribution of bacterial communities in the black soils of Northeast China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 70, 113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.12.014

Lu, M., Yang, Y., Luo, Y., Fang, C., Zhou, X., Chen, J., et al. (2011). Responses of ecosystem nitrogen cycle to nitrogen addition: a meta-analysis. New Phytol. 189, 1040–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03563.x

Luo, S., Yu, L., Liu, Y., Zhang, Y., Yang, W., Li, Z., et al. (2016). Effects of reduced nitrogen input on productivity and N2O emissions in a sugarcane/soybean intercropping system. Eur. J. Agron. 81, 78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2016.09.002

Malekani, K., and Cresser, M. S. (1998). Comparison of three methods for determining boron in soils, plants, and water samples. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 29, 285–304. doi: 10.1080/00103629809369946

Minamisawa, K., Nishioka, K., Miyaki, T., Ye, B., Miyamoto, T., You, M., et al. (2004). Anaerobic nitrogen-fixing consortia consisting of clostridia isolated from gramineous plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 3096–3102. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.5.3096-3102.2004

Mo, A. S., Qiu, Z. Q., He, Q., Wu, H. Y., and Zhou, X. B. (2016). Effect of continuous monocropping of tomato on soil microorganism and microbial biomass carbon. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 47, 1069–1077. doi: 10.1080/00103624.2016.1165832

Ofek, M., Voronov-Goldman, M., Hadar, Y., and Minz, D. (2014). Host signature effect on plant root-associated microbiomes revealed through analyses of resident vs. active communities. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 2157–2167. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12228

Pang, G., Cai, F., Li, R., Zhao, Z., Li, R., Gu, X., et al. (2017). Trichoderma-enriched organic ertilizer can mitigate microbiome degeneration of monocropped soil to maintain better plant growth. Plant Soil 416, 181–192. doi: 10.1007/s11104-017-3178-0

Petersen, G. W., and Corey, R. B. (1966). A modified Chang and Jackson procedure for routine fractionation of inorganic soil phosphates 1. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 30, 563–565. doi: 10.2136/sssaj1966.03615995003000050012x

R Development Core Team (2008). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Shen, Z., Wang, D., Ruan, Y., Xue, C., Zhang, J., Li, R., et al. (2014). Deep 16S rRNA pyrosequencing reveals a bacterial community associated with banana Fusarium wilt disease suppression induced by bio-organic fertilizer application. PLoS ONE 9:e98420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098420

Smith, R. G., Gross, K. L., and Robertson, G. P. (2008). Effects of crop diversity on agroecosystem function: crop yield response. Ecosystems 11, 355–366. doi: 10.1007/s10021-008-9124-5

Soil Survey Staff (2014). Key to Soil Taxonomy. 12th edn. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS).

Tian, W., Wang, L., Li, Y., Zhuang, K., Li, G., Zhang, J., et al. (2015). Responses of microbial activity, abundance, and community in wheat soil after three years of heavy fertilization with manure-based compost and inorganic nitrogen. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 213, 219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2015.08.009

Walkley, A., and Black, I. A. (1934). An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 37, 29–38. doi: 10.1097/00010694-193401000-00003

Wang, B., Li, R., Ruan, Y., Ou, Y., Zhao, Y., and Shen, Q. (2015). Pineapple–banana rotation reduced the amount of Fusarium oxysporum more than maize–banana rotation mainly through modulating fungal communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 86, 77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.02.021

Wang, Y., Tu, C., Cheng, L., Li, C., Gentry, L. F., Hoyt, G. D., et al. (2011). Long-term impact of farming practices on soil organic carbon and nitrogen pools and microbial biomass and activity. Soil Tillage Res. 117, 8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2011.08.002

Ward, N. L., Challacombe, J. F., Janssen, P. H., Henrissat, B., Coutinho, P. M., Wu, M., et al. (2009). Three genomes from the phylum Acidobacteria provide insight into the lifestyles of these microorganisms in soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 2046–2056. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02294-08

Xing, H. Q., Xiao, Z. W., Yan, J. Z., Ma, J. C., and Meng, Y. (2011). Effects of continuous cropping of maize on soil microbes and main soil nutrients. Pratacult. Sci. 28, 1777–1780. doi: 10.1081/CSS-200056917

Xiong, W., Zhao, Q., Xue, C., Xun, W., Zhao, J., Wu, H., et al. (2016). Comparison of fungal community in black pepper-vanilla and vanilla monoculture systems associated with vanilla Fusarium wilt disease. Front. Microbiol. 7:117. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00117

Xu, L., Ravnskov, S., Larsen, J., and Nicolaisen, M. (2012). Linking fungal communities in roots, rhizosphere, and soil to the health status of Pisum sativum. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 82, 736–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01445.x

Xun, W., Huang, T., Zhao, J., Ran, W., Wang, B., Shen, Q., et al. (2015). Environmental conditions rather than microbial inoculum composition determine the bacterial composition, microbial biomass and enzymatic activity of reconstructed soil microbial communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 90, 10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.07.018

Yuan, J., Chaparro, J. M., Manter, D. K., Zhang, R., Vivanco, J. M., and Shen, Q. (2015). Roots from distinct plant developmental stages are capable of rapidly selecting their own microbiome without the influence of environmental and soil edaphic factors. Soil Biol. Biochem. 89, 206–209. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.07.009

Zeng, Q., An, S., and Liu, Y. (2017). Soil bacterial community response to vegetation succession after fencing in the grassland of China. Sci. Total Environ. 609, 2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.102

Zhalnina, K., de Quadros, P. D., Camargo, F. A., and Triplett, E. W. (2012). Drivers of archaeal ammonia-oxidizing communities in soil. Front. Microbiol. 3:210. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00210

Zhang, C., Liu, G., Xue, S., and Wang, G. (2016). Soil bacterial community dynamics reflect changes in plant community and soil properties during the secondary succession of abandoned farmland in the Loess Plateau. Soil Biol. Biochem. 97, 40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.02.013

Keywords: microbial community, microbial diversity, soybean, high-throughput sequencing, 16S rRNA gene, soil

Citation: Song X, Tao B, Guo J, Li J and Chen G (2018) Changes in the Microbial Community Structure and Soil Chemical Properties of Vertisols Under Different Cropping Systems in Northern China. Front. Environ. Sci. 6:132. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2018.00132

Received: 02 May 2018; Accepted: 24 October 2018;

Published: 13 November 2018.

Edited by:

Sudhakar Srivastava, Banaras Hindu University, IndiaReviewed by:

Saurabh Yadav, Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna Garhwal University, IndiaCopyright © 2018 Song, Tao, Guo, Li and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bo Tao, Ym90YW9sQDE2My5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.