- Chair of Energy Systems, Technical University Munich, Garching bei München, Germany

Fischer–Tropsch (FT) synthesis is an important module for the production of clean and sustainable fuels and chemicals, making it a topic of considerable interest in energy research. This mini-review covers the current literature on FT catalysis and offers insights into the primary products, the nuances of the FT reaction, and the product distribution, with particular attention to the Anderson–Schulz–Flory distribution (ASFD) and known deviations from this fundamental concept. Conventional FT catalysts, particularly Fe- and Co-based catalysis systems, are reviewed, highlighting their central role and the influence of water and water–gas shift (WGS) activity on their catalytic behavior. Various mechanisms of catalyst deactivation are also investigated, and the high methanation activity of Co-based catalysts is illustrated. To make this complex field accessible to a broader audience, we explain conjectured reaction mechanisms, namely, the carbide mechanism and CO insertion. We discuss the complex formation of a wide range of products, including olefins, kerosenes, branched hydrocarbons, and by-products such as alcohols and oxygenates. The article goes beyond the traditional scope of FT catalysis by addressing topics of current interest, including the direct hydrogenation of CO2 for power-to-X applications and the use of bifunctional catalysts to produce tailored FT products, most notably for the production of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). This mini-review provides a holistic overview of the evolving landscape of FT catalysts and is aimed at both experienced researchers and those new to the field while covering current and emerging trends in this important area of energy research.

1 Introduction

Fischer–Tropsch synthesis (FTS) is enjoying a renaissance due to its critical role in producing cleaner fuels and sustainable energy. In view of the global climate crisis, the increasing pressure on the petrochemical industry manifests in publicly expressed ambitions of stakeholders to substitute fossil-based fuels with sustainable alternatives.

The Fischer–Tropsch (FT) process was developed by Hans Fischer and Franz Tropsch (Fischer and Tropsch, 1926) to produce synthetic fuels and chemicals. Since then, it has been successfully established and commercialized, including for producing synthetic aviation fuel. This mini-review provides an overview of the most important FT reactions and their product distribution, focusing on conventional FT catalysts. Their function, behavior, and challenges of Fe- and Co-based catalysts are investigated in particular. The effects of water and water–gas shift (WGS) activity are examined, and the deactivation mechanisms of catalysts, especially the distinct methanation activity of Co-based catalysts, are presented. To simplify this complicated field, conjectured reaction mechanisms such as the carbide mechanism and CO insertion are presented. While the specific details of aviation fuel production are not extensively covered, crucial topics related to sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), covering the complexities of product formation, which includes olefins, paraffins, branched hydrocarbons, and by-products such as alcohols and oxygenates, are explained. The review also extends to current FTS research needs, including direct CO2 hydrogenation for power-to-X applications and the application of bifunctional catalysts to customize FT products. A comprehensive overview of FT catalysis is provided, highlighting current and future trends in energy research.

2 State of the art

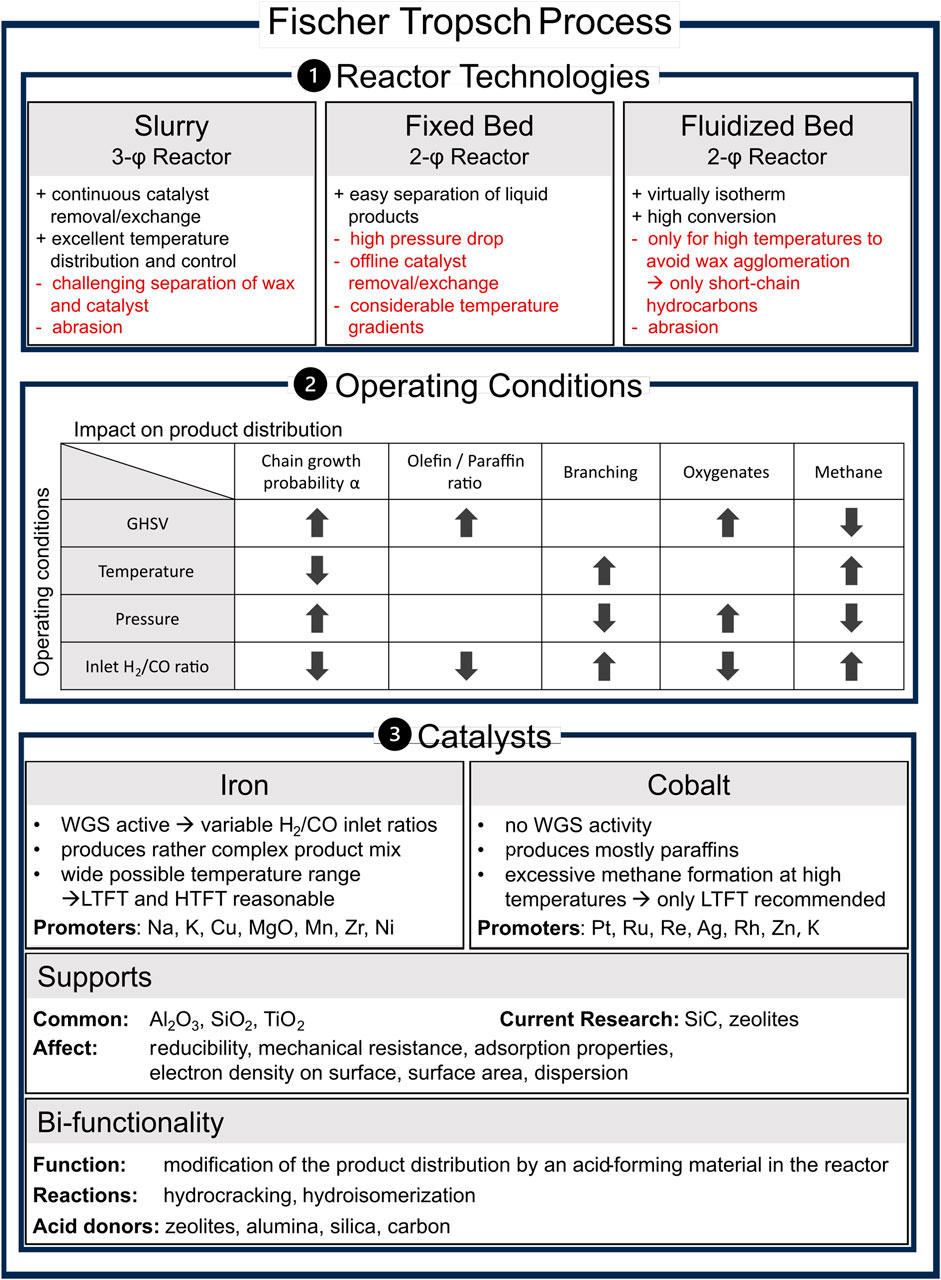

FTS is a heterogeneously catalyzed reaction that occurs at elevated pressure and temperature in slurry, fixed bed, or fluidized bed reactors. Figure 1 provides an overview of the reactor technologies, their advantages and challenges, the effects of operating conditions on product distribution, and the catalysts used.

Figure 1. Overview of the state of the art in Fischer–Tropsch synthesis, including reactor setup comparison, influence of key process parameters on product distribution, used catalysts and supports, and bifunctionality based on slurry/fixed bed/fluidized bed (Guettel et al., 2008; Dieterich et al., 2020); trends of operation parameters (Mena Subiranas et al., 2008; Horáček, 2020); promoters (Chun et al., 2020; Gholami et al., 2021); supports (Keyvanloo et al., 2014; Munirathinam et al., 2018); and bifunctional operation (Martínez-Vargas et al., 2019).

2.1 Fischer–Tropsch reaction and product distribution

The main FT reactions are based on the hydrogenation of CO over metallic catalysts. Highly exothermic polymerization or chain extension reactions form a mixture of organic compounds by chain growth through the gradual addition of C species (Mena Subiranas et al., 2008):

The Anderson–Schulz–Flory distribution (ASFD) estimates the product mixture’s chain-length distribution using the chain growth probability α (de Klerk, 2011). However, the ASFD alone does not describe the ratio of olefins and paraffins formed (see Section 2.1.1) or how branching and isomerization (see Section 2.1.2) occur. In addition, it can be overcome by using other functional materials, such as porous carriers, bifunctional catalysts, or additional metals.

The α-value and thus the ASFD depends on the employed catalyst, operating conditions, such as the gas hourly space velocity (GHSV), temperature, pressure and H2/CO ratio, the reactor, and their complex interactions. The overview provided in Figure 1 includes product distribution trends regarding the operation conditions. Temperature mainly affects the FT termination mechanisms (Quek et al., 2011). Consequently, high-temperature FT (HTFT) synthesis at approximately 300–350°C produces rather shorter and more complex products, such as olefins, aromatics, and oxygenates, while low-temperature FT (LTFT) synthesis at approximately 200–250°C yields mostly heavier paraffins (Dry, 2004).

Recognized deviations from the ASFD within the classic FTS have been documented in the literature (Todić et al., 2015). These variations mainly concern selectivity as a function of catalyst and operating conditions:

• Elevated methane production, particularly notable in Co-based catalysts.

• Reduced production of C2 compounds.

• An increase in α-values with increasing carbon number.

While the reasons for these deviations are not unambiguously solved, several explanatory approaches have been proposed and are explored in the subsequent sections. The general reaction mechanisms used to describe the formation of FT products are reviewed and discussed in Section 2.3.

The main primary products of the FTS are a mixture of paraffins/alkanes followed by olefins/alkenes and oxygenates of different chain lengths (Shafer et al., 2019). The primary co-products of the process are H2O and CO2. Secondary reactions also lead to the formation of cyclic and branched hydrocarbons (Adeleke et al., 2020).

2.1.1 Olefins and paraffins

The principal FT products, namely, paraffins, originate from the complete hydrogenation of CxHy intermediates or the re-adsorption of olefins (Rytter et al., 2020). However, manipulation of common catalysts by promoters or the use of oxide–zeolite compounds can significantly increase the olefin selectivity (Yu et al., 2022). Also, Fe-based catalysts naturally exhibit higher olefin selectivity than Co-based catalysts (Ma et al., 2020). The conjectured formation mechanisms are investigated in Section 2.3.1.

According to Schulz, Co has a higher hydrogenation rate than Fe, which leads to more paraffins due to re-adsorption (Schulz, 2007). Yu et al. (2013) showed that Co-based catalysts can be significantly more active for alkene hydrogenation than Fe catalysts. This could help to explain why Fe catalysts produce more complex products.

A facilitated desorption of olefins and inhibition of secondary hydrogenation is favorable for olefins. By reducing the H2/CO ratio, the hydrogenation activity is reduced, and thus, the olefin/paraffin (o/p) ratio increases. Furthermore, low pressure and higher GHSV increase the o/p ratio (Zhai et al., 2021). The o/p ratio decreases exponentially with chain length. Most explanations are based on a higher residence time for heavier hydrocarbons leading to hydrogenation via re-adsorption (Masuku et al., 2012). Moreover, higher α-values are witnessed for high selectivity toward paraffinic FT products (Shafer et al., 2019).

FT to olefin (FTO) processes trade between chain length and o/p ratio and mostly yield shorter hydrocarbons. Wang et al. (2023a) managed to produce 40% C12+ olefins via the Kölbel–Engelhardt synthesis of CO and H2O over PtCO2Mo2N and Ru particles. One of the major challenges is sufficient carbon usage, as C1 (CO2CH4 and CO2CO2) is not desired. Yu et al. (2022) addressed this issue and synthesized an Na-promoted and silica-supported Ru catalyst that yields less than 5% C1 at 45.8% CO conversion and 80.1% olefin selectivity. They assume a reduced H2 reactivity through Na, which minimizes the C1 selectivity.

2.1.2 Branched and cyclic hydrocarbons

Schulz obtained a length-dependent branching probability decreasing with increasing product length for LTFT, which is attributed to spatial confinement (Schulz, 2020). However, according to Shi et al. (2005), branching does not depend on carbon number at LTFT conditions and increases with chain length in HTFT. Branching on Fe and Co is proposed to follow the alkylidene mechanism, that is, by re-adsorption of olefins (Shi et al., 2014).

Fe-based catalysts show a selectivity toward branched products of approximately 25%, which is approximately five times higher than Co-based catalysts (Shi et al., 2014). Acid-providing zeolites are used to selectively increase the isoparaffin. Larger pores are assumed to be favorable toward higher iso/n-paraffin ratios. In addition, increasing the acidity and mass ratio of the zeolite will increase the iso/n-paraffin ratio until a certain threshold, where it reduces the chain length by excessive cracking. Xing et al. (2021) obtained up to 35.5 wt% of isoparaffin with Co/SiO2 + ZSM-5. Feng et al. (2022) combined ZnAlOx with SAPO-11 12 zeolite and synthesized a stable catalyst to obtain high iso/n-paraffin ratios of up to 48 within the gasoline range. They attribute their success to methodically increasing the number of external acid sites on the zeolite and assume a positive linear correlation between external acid sites and the iso/n-paraffin ratio. Cyclic hydrocarbons are favored by higher temperatures, facilitating desorption and increasing the likelihood of ring formation (Maitlis and de Klerk, 2013). No literature reports relevant amounts of cycloalkanes by CO or CO2 hydrogenation in a single pass. Current research focuses on lignin, a biomass waste, as a platform to synthesize jet fuel cycloalkanes in multiple steps (Gundekari and Kumar Karmee, 2021). However, aromatics can be produced with one pass by CO2 or CO hydrogenation. Wang et al. (2020) used TmEtRmVAQy9ILVpTTS01LTAuMg== and a combination of olefin-selective promoted-Fe combined with tailored acid sited for aromatic formation and obtained relevant amounts of aromatics from CO2 hydrogenation. Weber et al. (2021) combined an olefin-selective Fe catalyst with H-ZSM-5 zeolite to successfully convert syngas to aromatics in a single pass.

2.2 Conventional Fischer–Tropsch catalysts

Fe, Co, Ni, and Ru exhibit a sufficient reaction rate and polymerization probability to be used in FTS (de Klerk, 2011). Because Ru is very cost-intensive and Ni produces mainly light hydrocarbons during FTS, only Fe- and Co-based catalysts are used in industry today (de Klerk, 2011; Liu et al., 2017; Mahmoudi et al., 2017). Thus, only Fe- and Co-based catalysts are considered in this review. Their characteristics depend on surface structure, adsorption behavior, and the ability to promote CO dissociation, CO insertion, hydrogenation, and chain growth (Chuang et al., 2005). The overview provided in Figure 1 shows the key differences between Fe- and Co-based systems and the respective commonly used supports.

Co is less available and more costly than Fe and, therefore, is highly dispersed on supports (Shafer et al., 2019), thus enhancing the mechanical stability of such a Co-based system (O’Brien et al., 2000). Fe-based catalysts, on the other hand, have problems with abrasion in reactors (Lin et al., 2021). The intrinsic activity of Fe is lower than Co (Ma et al., 2020), whereas the selectivity on Fe is less prone to differences under operating conditions (Schulz, 2007; Botes et al., 2013). In general, Fe is more likely to produce more complex products than Co, which yields mostly paraffins (Shafer et al., 2019). The reaction temperature and H2/CO ratio must also be selected carefully for Co-based catalysts to avoid excessive methane formation at high reaction temperatures (see Section 2.2.3) (Zhang et al., 2010). Thus, Fe is used for both high- and low-temperature FTS, while Co is only deployed at low temperatures (Speight, 2016).

The active phases for Fe-catalyzed FTS are carbides (Gholami et al., 2022). This is in accordance with the required activation period, in which Fe forms mostly carbides (Zhao et al., 2021). Opeyemi Otun et al. (2021) comprehensively reviewed the structure, synthesis, and performance of carbides and reported that χ-Fe5C2, ɛ-Fe2C, ɛ’-Fe2.2C, ɛ-Fe3C, θ-Fe3C, and Fe7C3 have been identified in FTS so far. There is no consensus on which phase is the most active toward FTS. Further investigation of all inherent characteristics will lead to a systematically synthesized optimal catalyst. The active species for Co-based catalysts have been thoroughly investigated (ten Have and Weckhuysen, 2021). The main active phase is metallic Co. Co-oxide, which is only active for FTS when supported by a reducible metal oxide support. Co2C is reported to increase olefins and oxidized products when stabilized or promoted by an oxidic compound or an alkali promoter (ten Have and Weckhuysen, 2021). When promoted by reducible oxide ceria as support, oxygenate selectivity on Co increases significantly (Shafer et al., 2019). Studies without these promoters declare Co-carbide as an inactive phase (ten Have and Weckhuysen, 2021).

When Fe and Co catalysts are combined, the formation of different Fe–Co alloys, as well as common metallic and carbide phases of Co and Fe, is observed. Based on their experimental work, Aluha et al. (2015) proposed that the Fe–Co alloys (Co–Fe, Co3Fe7, and Fe3Co7) are not reactive for FTS. Yet, the employment of such catalysts leads to various results in selectivity, reactivity, and conversion (Jahangiri et al., 2014). While no general advantage regarding catalyst properties is recognizable for conventional FTS, hybrid catalysts may offer benefits for direct CO2 hydrogenation (see Section 3.1).

2.2.1 Influence of water and water–gas shift activity

Water is a primary co-product in FTS. On Co-based catalysts, H2O leads to an increase in C5+ selectivity (Borg et al., 2014; Rytter and Holmen, 2017). Furthermore, an increase in H2O partial pressure leads to irreversible deactivation of the catalyst (Borg et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017). The smaller the pores of the support, the more sensitive it is to increased amounts of H2O because water vapor most likely condenses in smaller pores and blocks diffusion paths (Rytter and Holmen, 2017). Both the deactivation mechanism and the reversibility depend on the selected support. Deactivation due to H2O on SiO2 is reported to be mostly permanent, on Al2O3 partially reversible, and on TiO2 mostly reversible (Storsater et al., 2005). Other deactivation mechanisms are discussed in Section 2.2.2.

While the WGS reaction has negligible influence on Co-based catalysts, its activity on Fe is significant (Méndez and Ancheyta, 2020). On Fe-based catalysts, H2O increases the WGS reaction rate and oxygenate selectivity while reducing CH4 selectivity. Here, H2O also reversibly decreases catalyst activity until a feed composition of approximately 40 mol% after which the deactivation becomes completely irreversible (Satterfield et al., 1986).

No definite explanation exists regarding the active phase of the WGS reaction (Puga, 2018). The WGS reaction consumes H2O and CO from the FT reaction in favor of H2 and CO2. When the amount of H2O in FTS increases with increasing syngas conversion, the WGS reaction becomes more active, leading to an increased H2/CO ratio. Consequently, when Fe is used, a lower H2/CO feed ratio is applicable (Ostadi et al., 2019). As the WGS reaction is influenced by the partial pressure of water, it has less influence on overall product distribution at low conversions with low H2O partial pressure. The WGS reaction passes the equilibrium at a particular H2/CO feed ratio and CO conversion and gains influence when both are increasing. This potentially leads to lower-weight hydrocarbons through a shift toward higher H2/CO usage ratios at high CO conversion and H2/CO feed ratios (Bukur et al., 2016).

The selectivity of CO2 is influenced by the WGS reaction (see also Section 2.2.1) (Maitlis and de Klerk, 2013).

As the WGS reaction involves CO2, it can alter the CO2 selectivity on Fe-based catalysts. Although for Co-based catalysts, the CO2 yield does not exceed a few percent, on WGS-promoting catalysts, CO2 selectivity can be up to 50% (Maitlis and de Klerk, 2013). However, based on experiments and density functional theory (DFT) calculations, Liu et al. (2018) suggest the Boudouard mechanism (CO + CO- > CO2+C) as the predominant pathway for CO2 formation on χ-Fe5C2, while H2O formation is hindered. To overcome this effect, Wang et al. (2018) prepared ɛ’-Fe carbides that are stable under Fe conditions and produce significantly less CO2. It is assumed that the oxygenation reaction of CO to CO2 prevails and is further altered by the (r)WGS activity (Krylova et al., 2012).

2.2.2 Catalyst deactivation mechanisms

Catalyst lifetime is a crucial aspect of economic operation and resource efficiency. It is limited by mechanical abrasion and chemical deactivation. Poisoning substances are H2S, HCl, HBr, HBf, NH3, and others, with H2S being the most crucial (Davis et al., 2011).

The chosen catalyst, support, and promoter determine the amount of poison a catalyst can tolerate (Davis et al., 2011). In general, Fe is more resistant to poisoning than Co (Lin et al., 2021). Hydrothermal sintering on Co and Fe is favored by high temperatures, small particle sizes, and high partial water pressures (Rytter and Holmen, 2015; Wolf et al., 2020). Oxidization strongly depends on the support (Wolf et al., 2020). It is favored by high water pressure inhibiting H2 from reacting with the dissociated O to H2O (Duvenhage and Coville, 2006; Wolf et al., 2018). However, oxidation of the active phase under FT conditions is a matter of concern, mainly for small clusters in the order of a few nanometers (Corral Valero and Raybaud, 2013). Fouling in FTS is characterized by the deposition and physical blocking of active sites by long and complex hydrocarbons or deposited carbon (Ghofran Pakdel et al., 2019). The latter is only harmful in a graphite state, whereas amorphous carbon deposition can easily be removed by hydrogenation during operation (Chen et al., 2018a).

Accumulation of wax within the pores of the catalyst alters the product selectivity and activity. Unglaub and Jess (2023) deployed periodical hydrogenolysis by switching the inlet from syngas to H2 to extract the wax. Hydrogenolysis is governed by the predominant cracking of the terminal bond and the desorption of the remaining alkane, which depends on chain length, partial H2 pressure, and temperature through the adsorption strength of H2 and paraffin. They reported achieving a higher overall selectivity toward the jet fuel range over the common operation (Unglaub and Jess, 2023).

2.2.3 Methanation activity of Co-based catalysts

Different explanations have been proposed for disproportionate methanation taking place on Co-based catalysts. One approach suggests different sites that are more available on Co than on Fe (Schulz, 2007). Experimental work indicates that terrace sites occurring in Co-based catalysts could be more likely to produce methane. The deposition of graphitic carbon on Co terrace sites by the Boudouard reaction decreases CH4 formation while C2+ selectivity remains unchanged (Chen et al., 2018a). Moreover, secondary hydrogenolysis, which means a-scission at the terminal carbon and hydrogenation of it for Fe and Co (Matsumoto, 1971), has been mentioned in this context. Co is regarded to be more active for hydrogenolysis (de Klerk, 2011). An alternative explanation may reside in the fact that the activation energy for the methanation of Co is ideal, whereas Fe exhibits an excessively strong adsorption force (van de Loosdrecht et al., 2013). The promotion of Co with Zn leads to stronger CO adsorption, thus higher C/H surface ratios and less methane, according to DFT calculations (Fang et al., 2020).

2.3 Conjectured reaction mechanisms

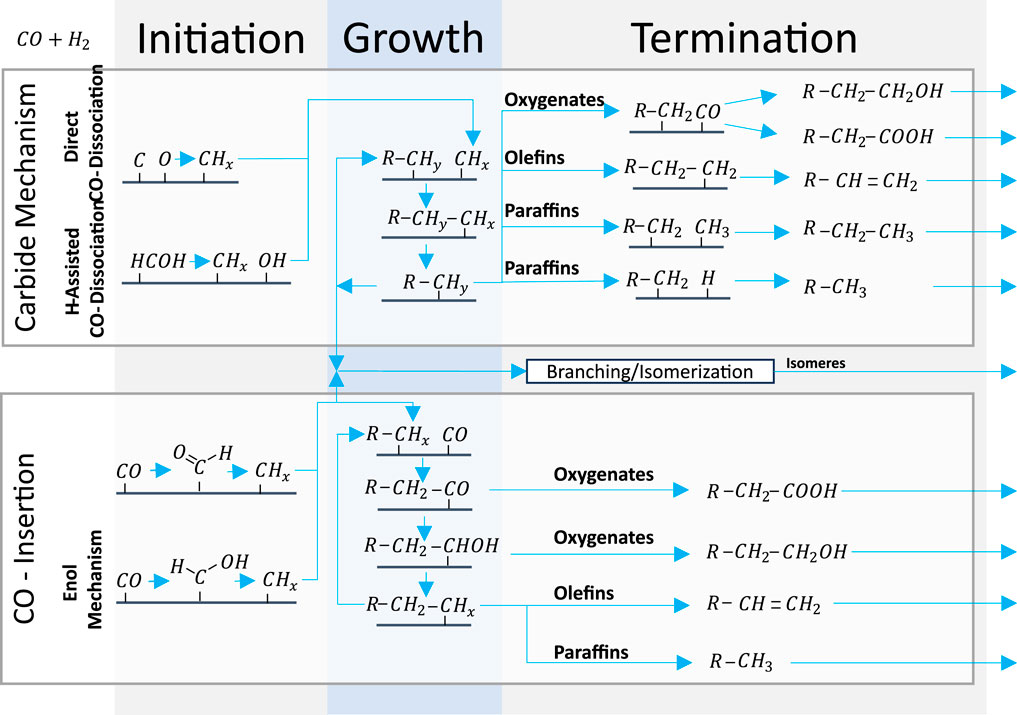

FTS is a mixture of very complex reactions. Reaction mechanisms are proposed to explain the variety of FT products including initiation, growth, and termination steps. The mechanisms can help understand the known deviations from the ASFD encompassing over-selectivity toward CH4, under-selectivity toward C2 compounds, and a carbon-number-dependent over-selectivity for longer-chain products, as discussed in Section 2.1.

Many possible detailed pathways have been proposed, for example, by Davis (2001) and Lualdi (2012). Some mechanisms have been proposed in the literature to explain the deviations, including increased C2 reactivity leading to C2 being incorporated into other hydrocarbons (Förtsch et al., 2015) and van der Waals-related desorption rates that can cause an α increase with increasing chain length (Todic et al., 2014). One approach to address the deviations from the ASFD is to use various α-values corresponding to different product types or chain-length groups, thereby accounting for distinct Fischer–Tropsch mechanisms (Patzlaff et al., 2002). Patzlaff et al. (1999) argued for two distinct mechanisms because their model with two different α-values fit well for Fe catalysts, excluding the influence of secondary chain growth reactions.

The two predominant mechanistic theories in FTS are the carbide mechanism and CO insertion, as explained in Section 2.3.1. Within the scope of this review, the enol mechanism, which is similar to CO insertion only with COHy as an intermediate, is considered a sub-class of the CO insertion mechanism (van Santen and Markvoort, 2013). Furthermore, several kinetic models have been developed based on the carbide mechanism and the CO insertion mechanism that have already been successfully implemented and could predict the product distribution (Todic et al., 2014; Marchese et al., 2019).

2.3.1 Carbide mechanism and CO insertion

The widely recognized carbide mechanism and CO insertion mechanism are illustrated in Figure 2. The carbide mechanism is characterized by the dissociation of CO or COHy followed by hydrogenation of C to CHx monomer participating in chain growth (van Santen et al., 2013). Initially, Fischer and Tropsch posited that carbide species were responsible for supplying the carbon atoms (Fischer and Tropsch, 1926). However, Kummer et al. (1948) demonstrated that the reduction of Fe carbides yields only minimal amounts of carbon. Consequently, contemporary understanding suggests chemisorbed species as the source of carbon.

Figure 2. Simplified representation of widely recognized carbide mechanism and CO insertion describing the production of Fischer–Tropsch products based on H-assisted carbide mechanism initiation (Ojeda et al., 2010); carbide mechanism termination to oxygenates (Teng et al., 2005); carbide mechanism termination to olefins/paraffins (Mahmoudi et al., 2017); branching (Shi et al., 2005); direct CO insertion initiation (ten Have and Weckhuysen, 2021); enol mechanism initiation (Davis, 2001); CO insertion termination to oxygenates (Teng et al., 2005); CO insertion termination to paraffins/olefins (Shafer et al., 2019); and secondary reactions and bifunctional reactions (Sineva et al., 2023).

For the carbide mechanism to apply, the CO to CHx coupling, that is, the C-O bond cleavage and hydrogenation of C to CHx and monomer, must both be fast versus chain termination and CO insertion (van Santen et al., 2013). However, this implies that step sites must be viable for fast direct CO dissociation (Qi et al., 2015). At the same time, the activation energy of direct CO dissociation is considered to be too high to be consistent with FT reactivity on flat and less reactive surfaces (Chen et al., 2017). Thus, several H-assisted mechanisms with decreased activation energy have been proposed for flat surfaces (Zhang et al., 2020). An experiment on a Co-based catalyst supports the assumption of particular sites for direct CO dissociation by disclosing that only a small fraction of the surface can dissociate CO without H2 at viable rates (Chen et al., 2018b). Therefore, the chain length could be controlled by the chain-terminating hydrogenation rate on step sites (van Santen et al., 2014) and by CHx formation on flat surfaces (van Santen et al., 2014).

The assumed CHx monomers, however, cannot explain the formation of oxygenates. Therefore, Pichler and Schulz (1970) proposed the CO insertion mechanism for the first time in 1970. It is characterized by CO for chain initiation or growth by insertion into an existing chain and cleavage of the C-O bond only after insertion by condensation with H to H2O (van Santen et al., 2013; Todic et al., 2014). For this mechanism to apply, chain growth, that is, CO insertion followed by C-O bond cleavage, must be fast compared to chain termination and direct CO dissociation. The mechanism is commonly regarded as surface insensitive because it is a condensation reaction (van Santen and Markvoort, 2013).

Chen et al. (2017) experimentally proved that the carbide mechanism is possible. A surface covered with C but no CO was obtained after feeding CO to their reactor setup, followed by evacuation of the reactor. In a further step, H2 was fed to the reactor, and C1–C3 hydrocarbons were obtained. By co-feeding marked C3H6 to syngas, they showed that the chain decoupling is an important step in FTS, and CHx must be active as a monomer. The marked C atoms were observable at any chain length (Chen et al., 2017).

Zhou et al. (2021) conducted experiments over an Fe catalyst, obtaining arguments for both mechanisms. With an inlet stream only composed of H2 and alkenes as a single carbon source, the occurrence of FT reactions is a plausible argument in favor of the carbide mechanism because no CO molecules are available for insertion. In favor of the CO insertion mechanism is the fact that co-feeding oxygenates to the common inlet leads to a parallel shift in the product distribution where only the CO insertion pathway offers the possibility of oxygenates as chain initiators (Zhou et al., 2021).

Corral Valero and Raybaud (2013) found, based on Co DFT calculation, that Co flat surface models favor the CO insertion while kinetic considerations that take a more versatile surface into account argue in favor of the carbide mechanism. They conclude that the active mechanism is probably a trade-off of thermodynamic properties. Okonye et al. (2023) studied the temperature dependency of both mechanisms on Ru catalysts. They proposed that CO insertion dominates at a lower temperature, while Co dissociation takes over at higher temperatures. Jamaati et al. (2023) thoroughly investigated the literature regarding FTS mechanisms. Direct CO dissociation is more structure-sensitive than H-assisted dissociation. Higher CO coverage is presumably favorable for the CO insertion mechanism.

3 Novel research areas

3.1 CO2 hydrogenation

In power-to-liquid processes and in biomass-to-liquid approaches, relevant amounts of CO2 in the FT feed gas typically make a reverse WGS reaction step before the FT reactor mandatory. However, direct CO2 hydrogenation would eliminate the need for this additional level of complexity (Brübach et al., 2022).

Different from Co, the CO2 conversion in FT is viable on Fe and Fe-Co catalysts as CO2 has vastly different effects over Fe- or Co-based catalysts in FTS.

On Co-based catalysts, CO2 is inert yet competes with CO for active sites. The CO2 conversion only starts at a CO conversion of 100% and leads to a vast majority of methane (Gnanamani et al., 2011). Moreover, the use of a hybrid catalyst with Co is not feasible toward higher hydrocarbons as the attainable CO partial pressure will not be sufficient (Riedel et al., 1999). On Fe catalysts, CO2 is reduced to CO, most likely by Fe-oxides via the reverse WGS reaction (Einemann et al., 2020). CO then acts as a reactant for the FTS (Gnanamani et al., 2011). Thus, the CO2 fraction must be above a temperature-dependent threshold where the WGS equilibrium shifts toward the reverse WGS reaction for the CO2 conversion (Kang et al., 2013). The product selectivity over Fe is generally similar with CO or CO2 as feed (Riedel et al., 1999). However, deviations toward lighter (Gnanamani et al., 2011) and heavier (Rafati et al., 2015) hydrocarbons can be found in the literature.

Satthawong et al. (2013) found that the combination of Fe with Co with a high Fe/Co ratio can enhance the activity and selectivity when using CO2 and H2. Wang et al. (2023b) proposed that Co enhances the activity by its H2 dissociation ability, which can be altered by potassium to enhance the hydrogenation characteristics of CO formation and additionally enhances the formation of Fe phases that reduce CO2 to CO.

3.2 Bifunctional Fischer–Tropsch catalysts

In an ideal ASFD chain growth model, the jet fuel hydrocarbon range of C8–C16 is favored at an optimum α-value of 0.84, achieving a maximum selectivity of approximately 40% (Dossow et al., 2022). The use of bifunctional catalysts can enable an efficient and tailored SAF production process that offers a selectivity of more than 70% toward jet fuel with a high isoparaffin content (Li et al., 2018). Bifunctional catalysts are special types of catalysts that have two different types of catalytic sites, allowing them to drive two different types of chemical reactions. In FT bifunctional catalysts, metal nanoparticles are dispersed within the cavities of acidic zeolite structures. Combining the functions of dehydrogenation and hydrogenation with the acidic properties of the zeolite framework makes these catalysts particularly interesting for FTS (Farrusseng and Tuel, 2017; Sineva et al., 2023).

3.2.1 Acid sites and supports

The combination of both active materials can be realized by the physical mixture of different particles, the acid material as a binder or support, and a shell around a common catalyst particle (Sineva et al., 2023). The acid sites can be provided by zeolites, clays, alumina, silica, alumino-silicates, and carbon (Martínez-Vargas et al., 2019). Zeolites are available in many variations as H-ZSM, ZSM, Beta, NaY, Y, and other appearances, with different characteristics and, therefore, different selectivities toward isomers, olefins, and C ranges. Overall, they provide good acidity, high thermal stability, and porosity (Sineva et al., 2023). The porosity can be tuned within specific boundaries for different zeolites and sieve products/reactants/intermediates (Mena Subiranas et al., 2008). The acidity can also be tailored to influence the hydrocracking activity of the catalyst (Shamzhy et al., 2019). Some downsides are strong metal–support interaction and deactivation via coking (Martínez-Vargas et al., 2019). Alumina and silica bifunctionality are based on the same underlying ceramics, Al2O3, and SiO2, which are common supports. Alumina provides good mechanical and chemical stability, and its weak acidity must be enhanced for bifunctionality. Silica has excellent chemical stability and must be modified because it has no inherent acidity (Martínez-Vargas et al., 2019). Functionalized carbon supports are overcoming the downside of strong metal–support interaction and inertial compound formation. However, the functionalization via acid treatment and longevity needs further research (Martínez-Vargas et al., 2019).

3.2.2 Reaction mechanisms

FT bifunctional catalysts are especially useful for processes like hydroisomerization and hydrocracking of alkanes (Farrusseng and Tuel, 2017). The most important forms of cracking in a one-stage process are hydrocracking and catalytic cracking (Sartipi et al., 2014). The former, also known as bifunctional cracking, is characterized by an active metal site (de)hydrogenating saturated hydrocarbons and Brønsted acid sites donating a proton to form a carbenium intermediate (Weitkamp, 2012). Ideal hydrocracking refers to conditions where (de)hydrogenation dominates over the activity of the acid sites, and a particular isomerization distribution emerges (Thybaut et al., 2005). Catalytic cracking is mono-metallic cracking on acid sites that also leads to a carbenium intermediate. It is favored at temperatures even higher than HTFT, creating more isomeres than bifunctional cracking. However, the high temperatures also lead to higher deactivation by carbon deposition. The carbenium intermediate of both cracking types is reactive for C-C cleavage and skeletal rearrangements (Weitkamp, 2012).

With an increasing magnitude of acidity, the cracking activity increases until it reaches a threshold of −140 kJ/mol ammonia desorption heat, where other relationships must be considered (Niwa et al., 2010). It is reported that the overall conversion is proportional to the number of Brønsted acid sites (Deviana et al., 2023). Longer Chains are more likely to be cracked (Abbot and Dunstan, 1997). Isomerization increases with temperature until cracking prevails (Mena Subiranas et al., 2008).

3.2.3 Influence on product selectivity

Several researchers report the benefits of bifunctional catalysts in tailoring FT product selectivity. Peng et al. (2015), for example, reached 60 mol% selectivity toward C10–C20 at 40% CO conversion on a mesoporous-Y zeolite-supported Co catalyst. They also report that Co/H-Y-meso catalysts with Brønsted acid sites have more C4–C5 products caused by higher isomerization and cracking activities, while the Co/Y-meso-Na catalyst without Brønsted acid sites has more CH4 and C10–C15 due to a high hydrogenolysis activity (Peng et al., 2015). The pore structure of the catalyst requires particular emphasis (Straß-Eifert et al., 2021). Li et al. (2018) also showed that Co/Y-meso-Na could effectively crack C21+ hydrocarbons and that Co/Y-micro-Na catalysts with a different pore structure than the CO/Y-meso-Na have higher CH4 and C2–C4 selectivity. They further enhanced the selectivity toward 72 wt% kerosene by substituting Na for La and obtained excellent stability of CO conversion and selectivity. Another study used a P-Fe catalyst mixed with H-ZSM-5 and yielded CO conversion of 73%–78% with a C5–C20 selectivity of 72 wt% vs. 36 wt% without H-ZSM-5 (Deviana et al., 2023). Papeta et al. (2023) investigated Co with H-Beta zeolite and reached 73.4 wt% toward C5+. By varying the relation between the zeolite and Co, they effectively altered the split between C5–C10, C11–C18, and C19+.

4 Discussion and outlook

The comprehensive coverage of Fischer–Tropsch catalysis in this review provides a basis for discussions on the current status and future directions of this key area of energy research. The focus extends beyond the conventional boundaries of FTS to include promising avenues such as the direct hydrogenation of CO2 and the use of bifunctional catalysts for customized fuel production, particularly for SAF. Because SAF production stands out as a crucial application for FT products, future research in this area should prioritize scalability, feasibility, and the development of catalysts specifically tailored for drop-in applications. The combination of direct CO2 hydrogenation and the use of bifunctional catalysts opens new possibilities for sustainable fuel production via FTS.

The direct hydrogenation of CO2 for power-to-liquid or biomass-to-liquid applications presents a promising new opportunity. Research is currently focused on the systematic investigation and optimization of catalyst materials to improve the efficiency and selectivity of the direct conversion of CO2 in FTS. Novel catalyst compositions, nanostructuring, and surface modifications are under investigation to improve catalytic activity. While catalyst stability and longevity are crucial to ensure long-term performance, research on reaction kinetics, thermodynamics, and mass transfer is required to ensure high conversion rates and desired product selectivity on the process engineering side. Optimal operating conditions in terms of temperature, pressure, and H2/CO2 ratios are under investigation.

Using bifunctional catalysts to enhance product selectivity and to tailor FT products also opens novel possibilities for achieving enhanced product selectivity, especially in producing SAF. Therefore, it is necessary to understand how the synergies between metal and acidic sites collectively influence reaction pathways. The development of bifunctional catalysts with tailored active sites for the desired reactions requires research on optimal combinations of metal and acid sites to explore the catalyst’s ability to control product distribution. Once again, optimizing the reaction conditions is key to exploiting the bifunctional nature of the catalysts. This includes fine-tuning parameters such as temperature, pressure, and H2/CO or H2/CO2 ratio, as well as testing novel reactor technologies.

Ultimately, it is essential to combine an understanding of catalysis with the principles of chemical and process engineering in FTS research. The transition from laboratory-scale studies to real-world applications requires a comprehensive assessment and close collaboration between academia, industry, and policymakers. Bridging the gap between fundamental research and practical implementation is essential to ensure the seamless integration of novel FT technologies into the broader energy landscape. Particularly, the in-depth exploration of SAF production and selectivity necessitates a dedicated review coupled with original research for a more exhaustive treatment of the topic. Meanwhile, conventional catalyst research holds the potential to enhance SAF selectivity up to an ASFD-defined maximum of approximately 40%. The exploration of advanced catalytic systems, particularly bifunctional catalysts, presents a promising avenue to enhance FT selectivity toward the jet fuel fraction far beyond this limitation.

In conclusion, the future of FT synthesis research lies in a multidisciplinary approach, where innovation in catalyst design, process optimization, and practical implementation converge. By addressing these challenges and pursuing promising avenues, researchers can contribute significantly to the advancement of Fischer–Tropsch synthesis as a key player in sustainable energy production.

Author contributions

AK: investigation, visualization, writing–original draft, and writing–review and editing. MD: conceptualization, project administration, visualization, writing–original draft, and writing–review and editing. VD: conceptualization and writing–review and editing. HS: funding acquisition, supervision, and writing–review and editing. SF: funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, and writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. We gratefully acknowledge funding of the projects “H2 Reallabor Burghausen” (03SF0705B), and “REDEFINE H2E” (01DD21005), both sponsored by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. In addition, the authors acknowledge the cooperation within the Network TUM. Hydrogen and PtX.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

ASFD, Anderson–Schulz–Flory distribution; FT, Fischer–Tropsch; FTO, Fischer–Tropsch to olefin; FTS, Fischer–Tropsch synthesis; GHSV, gas hourly space velocity; HTFT, high-temperature Fischer–Tropsch; LTFT, low-temperature Fischer–Tropsch; o/p, olefin/paraffin; WGS, water–gas shift.

References

Abbot, J., and Dunstan, P. R. (1997). Catalytic cracking of linear paraffins: effects of chain length. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., doi:10.1021/ie960255e

Adeleke, A. A., Liu, X., Lu, X., Moyo, M., and Hildebrandt, D. (2020). Cobalt hybrid catalysts in fischer-tropsch synthesis. Rev. Chem. Eng. 36, 437–457. doi:10.1515/revce-2018-0012

Aluha, J., Braidy, N., Dalai, A. K., and Abatzoglou, N. (2015). “Low-temperature fischer-tropsch synthesis with carbon-supported nanometric iron-cobalt catalysts,” in 23rd European Biomass Conference and Exhibition (EUBCE), Vienna, Austria, June, 2015. doi:10.5071/23rdEUBCE2015-3CO.15.1

Borg, Ø., Yu, Z., ChenBlekkan, E. A., Rytter, E., and Holmen, A. (2014). The effect of water on the activity and selectivity for carbon nanofiber supported cobalt fischer–tropsch catalysts. Top. Catal. 57. doi:10.1007/s11244-013-0205-0

Botes, F. G., Niemantsverdriet, J. W., and van de Loosdrecht, J. (2013). A comparison of cobalt and iron based slurry phase fischer–tropsch synthesis. Catal. Today 215. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2013.01.013

Brübach, L., Hodonj, D., Biffar, L., and Pfeifer, P. (2022). Detailed kinetic modeling of co2-based fischer–tropsch synthesis. Catalysts 12. doi:10.3390/catal12060630

Bukur, D. B., Todic, B., and Elbashir, N. (2016). Role of water-gas-shift reaction in fischer–tropsch synthesis on iron catalysts: a review. Catal. Today 275. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2015.11.005

Chen, W., Filot, I. A. W., Pestman, R., and Hensen, E. J. M. (2017). Mechanism of cobalt-catalyzed co hydrogenation: 2. fischer-tropsch synthesis. ACS Catal. 7, 8061–8071. doi:10.1021/acscatal.7b02758

Chen, W., Kimpel, T. F., Song, Y., Chiang, F.-K., Zijlstra, B., Pestman, R., et al. (2018a). Influence of carbon deposits on the cobalt-catalyzed fischer-tropsch reaction: evidence of a two-site reaction model. ACS Catal. 8. doi:10.1021/acscatal.7b03639

Chen, W., Zijlstra, B., Filot, I. A. W., Pestman, R., and Hensen, E. J. M. (2018b). Mechanism of carbon monoxide dissociation on a cobalt fischer-tropsch catalyst. ChemCatChem 10. doi:10.1002/cctc.201701203

Chuang, S. S. C., Stevens, R. W., and Khatri, R. (2005). Mechanism of c2+ oxygenate synthesis on rh catalysts. Top. Catal. 32. doi:10.1007/s11244-005-2897-2

Chun, D. H., Rhim, G. B., Youn, M. H., Deviana, D., Lee, J. E., Park, J. C., et al. (2020). Brief review of precipitated iron-based catalysts for low-temperature fischer–tropsch synthesis. Top. Catal. 63. doi:10.1007/s11244-020-01336-6

Corral Valero, M., and Raybaud, P. (2013). Cobalt catalyzed fischer–tropsch synthesis: perspectives opened by first principles calculations. Catal. Lett. 143. doi:10.1007/s10562-012-0930-1

Davis, B., Jacobs, G., Ma, W., Sparks, D., Azzam, K., Mohandas, J. C., et al. (2011). Sensitivity of fischer-tropsch synthesis and water-gas shift catalysts to poisons from high-temperature high-pressure entrained-flow (ef) oxygen-blown gasifier gasification of coal/biomass mixtures. https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1052997.

Davis, B. H. (2001). Fischer–tropsch synthesis: current mechanism and futuristic needs. Fuel Process. Technol. 71. doi:10.1016/s0378-3820(01)00144-8

de Klerk, A. (2011). Fischer–tropsch refining. Hoboken, New Jersey, United States: Wiley. doi:10.1002/9783527635603

Deviana, D., Bae Rhim, G., Kim, Y.-e., Song Lee, H., Woo Lee, G., Hye Youn, M., et al. (2023). Unravelling acidity–selectivity relationship in the bifunctional process of fischer-tropsch synthesis and catalytic cracking. Chem. Eng. J. 455. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2022.140646

Dieterich, V., Buttler, A., Hanel, A., Spliethoff, H., and Fendt, S. (2020). Power-to-liquid via synthesis of methanol, dme or fischer–tropsch-fuels: a review. Energy and Environ. Sci. 2024. doi:10.1039/d0ee01187h

Dossow, M., Dieterich, V., Hanel, A., and Fendt, S. (2022). “Chapter 11. sustainable aviation fuel from biomass via gasification and fischer–tropsch synthesis,” in Catalysis series (London, United Kingdom: Royal Society of Chemistry). doi:10.1039/9781839167829-00337

Dry, M. E. (2004). Chemical concepts used for engineering purposes. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 152. doi:10.1016/s0167-2991(04)80460-9

Duvenhage, D., and Coville, N. (2006). Deactivation of a precipitated iron fischer–tropsch catalyst—a pilot plant study. Appl. Catal. A General 298. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2005.10.009

Einemann, M., Neumann, F., Thomé, A. G., Ghomsi Wabo, S., and Roessner, F. (2020). Quantitative study of the oxidation state of iron-based catalysts by inverse temperature-programmed reduction and its consequences for catalyst activation and performance in fischer-tropsch reaction. Appl. Catal. A General 602. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2020.117718

Fang, X., Liu, B., Cao, K., Yang, P., Zhao, Q., Jiang, F., et al. (2020). Particle-size-dependent methane selectivity evolution in cobalt-based fischer–tropsch synthesis. ACS Catal. 10, 2799–2816. doi:10.1021/acscatal.9b05371

Farrusseng, D., and Tuel, A. (2017). “Chapter 11 - zeolite-encapsulated catalysts: challenges and prospects,” in Encapsulated catalysts. Editor S. Sadjadi (Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States: Academic Press), 335–386. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-803836-9.00011-0

Feng, J., Miao, D., Ding, Y., Jiao, F., Pan, X., and Bao, X. (2022). Direct synthesis of isoparaffin-rich gasoline from syngas. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 1462–1468. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.2c00467

Fischer, F., and Tropsch, H. (1926). Über die direkte synthese von erdöl–kohlenwasserstoffen bei gewöhnlichem druck. (erste mitteilung). Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft A B Ser. 59. doi:10.1002/cber.19260590442

Förtsch, D., Pabst, K., and Groß-Hardt, E. (2015). The product distribution in fischer–tropsch synthesis: an extension of the asf model to describe common deviations. Chem. Eng. Sci. 138. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2015.07.005

Ghofran Pakdel, M., Atashi, H., Mirzaei, A. A., and Zohdi-Fasaei, H. (2019). Deactivation model for an industrial g-alumina supported iron catalyst in the fischer tropsch synthesis. Chem. Sel. 4. doi:10.1002/slct.201802140

Gholami, Z., Gholami, F., Tišler, Z., Hubáček, J., Tomas, M., Bačiak, M., et al. (2022). Production of light olefins via fischer-tropsch process using iron-based catalysts: a review. A Rev. 12, 174. doi:10.3390/catal12020174

Gholami, Z., Tišler, Z., and Rubáš, V. (2021). Recent advances in fischer-tropsch synthesis using cobalt-based catalysts: a review on supports, promoters, and reactors. Catal. Rev. 63. doi:10.1080/01614940.2020.1762367

Gnanamani, M. K., Shafer, W. D., Sparks, D. E., and Davis, B. H. (2011). Fischer–tropsch synthesis: effect of co2 containing syngas over pt promoted co/g-al2o3 and k-promoted fe catalysts. Catal. Commun. 12. doi:10.1016/j.catcom.2011.03.002

Guettel, R., Kunz, U., and Turek, T. (2008). Reactors for fischer–tropsch synthesis. Chem. Eng. Technol. 31. doi:10.1002/ceat.200800023

Gundekari, S., and Kumar Karmee, S. (2021). Recent catalytic approaches for the production of cycloalkane intermediates from lignin–based aromatic compounds: a review. ChemistrySelect 6, 1715–1733. doi:10.1002/slct.202003098

Horáček, J. (2020). Fischer–tropsch synthesis, the effect of promoters, catalyst support, and reaction conditions selection. Monatsh. für Chem. - Chem. Mon. 151. doi:10.1007/s00706-020-02590-w

Jahangiri, H., Bennett, J., Mahjoubi, P., Wilson, K., and Gu, S. (2014). A review of advanced catalyst development for fischer–tropsch synthesis of hydrocarbons from biomass derived syn-gas. Catal. Sci. Technol. 4. doi:10.1039/C4CY00327F

Jamaati, M., Torkashvand, M., Sarabadani Tafreshi, S., and de Leeuw, N. H. (2023). A review of theoretical studies on carbon monoxide hydrogenation via fischer-tropsch synthesis over transition metals. Mol. Basel, Switz. 28, 6525. doi:10.3390/molecules28186525

Kang, S. C., Jun, K.-W., and Lee, Y.-J. (2013). Effects of the co/co 2 ratio in synthesis gas on the catalytic behavior in fischer–tropsch synthesis using k/fe–cu–al catalysts. Energy fuels., 27. doi:10.1021/ef401177k

Keyvanloo, K., Mardkhe, M. K., Alam, T. M., Bartholomew, C. H., Woodfield, B. F., and Hecker, W. C. (2014). Supported iron fischer–tropsch catalyst: superior activity and stability using a thermally stable silica-doped alumina support. ACS Catal. 4. doi:10.1021/cs401242d

Krylova, A. Y., Lyadov, A. S., Kulikova, M. V., and Khadzhiev, S. N. (2012). Formation of carbon dioxide in the Fischer-Tropsch synthesis on nanosized iron catalyst particles. Pet. Chem. 52, 74–78. doi:10.1134/S0965544112010045

Kummer, J. T., DeWitt, T. W., and Emmett, P. H. (1948). Some mechanism studies on the fischer-tropsch synthesis using c14. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 70. doi:10.1021/ja01191a029

Li, J., He, Y., Tan, L., Zhang, P., Peng, X., Oruganti, A., et al. (2018). Integrated tuneable synthesis of liquid fuels via fischer–tropsch technology. Nat. Catal. 1, 787–793. doi:10.1038/s41929-018-0144-z

Lin, Q., Cheng, M., Zhang, K., Li, W., Wu, P., Chang, H., et al. (2021). Development of an iron-based fischer—tropsch catalyst with high attrition resistance and stability for industrial application. Catalysts 11. doi:10.3390/catal11080908

Liu, B., Li, W., Zheng, J., Lin, Q., Zhang, X., Zhang, J., et al. (2018). CO2 formation mechanism in Fischer–Tropsch synthesis over iron-based catalysts: a combined experimental and theoretical study. Catal. Sci. Technol. 8, 5288–5301. doi:10.1039/C8CY01621F

Liu, J.-X., Wang, P., Xu, W., and Hensen, E. J. (2017). Particle size and crystal phase effects in fischer-tropsch catalysts. Engineering 3. doi:10.1016/J.ENG.2017.04.012

Lualdi, M. (2012). Fischer-tropsch synthesis over cobalt-based catalysts for BTL applications. Doctoral thesis in Chemical Engineering. Stockholm, Sweden: KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

Ma, W., Jacobs, G., Sparks, D. E., Todic, B., Bukur, D. B., and Davis, B. H. (2020). Quantitative comparison of iron and cobalt based catalysts for the fischer-tropsch synthesis under clean and poisoning conditions. Catal. Today 343. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2019.04.011

Mahmoudi, H., Mahmoudi, M., Doustdar, O., Jahangiri, H., Tsolakis, A., Gu, S., et al. (2017). A review of fischer tropsch synthesis process, mechanism, surface chemistry and catalyst formulation. J. Biofuels Eng. 2. doi:10.1515/bfuel-2017-0002

Maitlis, P. M., and de Klerk, A. (2013). Greener Fischer-Tropsch processes for fuels and feedstocks. Hoboken, New Jersey, United States: Wiley VCH. doi:10.1002/9783527656837

Marchese, M., Heikkinen, N., Giglio, E., Lanzini, A., Lehtonen, J., and Reinikainen, M. (2019). Kinetic study based on the carbide mechanism of a co-pt/g-al2o3 fischer–tropsch catalyst tested in a laboratory-scale tubular reactor. Catalysts 9. doi:10.3390/catal9090717

Martínez-Vargas, D. X., Sandoval-Rangel, L., Campuzano-Calderon, O., Romero-Flores, M., Lozano, F. J., Nigam, K. D. P., et al. (2019). Recent advances in bifunctional catalysts for the fischer–tropsch process: one-stage production of liquid hydrocarbons from syngas. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 58. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.9b01141

Masuku, C. M., Shafer, W. D., Ma, W., Gnanamani, M. K., Jacobs, G., Hildebrandt, D., et al. (2012). Variation of residence time with chain length for products in a slurry-phase fischer–tropsch reactor. J. Catal. 287. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2011.12.005

Matsumoto, H. (1971). The classification of metal catalysts in hydrogenolysis of hexane isomers. J. Catal. 22. doi:10.1016/0021-9517(71)90184-9

Mena Subiranas, A. (2008). Combining fischer-tropsch synthesis (FTS) and hydrocarbon reactions in one reactor. Ph.D. thesis. Karlsruhe, Germany: Universität Karlsruhe TH. doi:10.5445/IR/1000010077

Méndez, C. I., and Ancheyta, J. (2020). Kinetic models for fischer-tropsch synthesis for the production of clean fuels. Catal. Today 353. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2020.02.012

Munirathinam, R., Pham Minh, D., and Nzihou, A. (2018). Effect of the support and its surface modifications in cobalt-based fischer–tropsch synthesis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.8b03850

Niwa, M., Katada, N., and Okumura, K. (2010). “Characterization and design of zeolite catalysts: solid,” in Acidity, shape selectivity and loading properties (Berlin, Germany: Springer).

O’Brien, R. J., Xu, L., Bao, S., Raje, A., and Davis, B. H. (2000). Activity, selectivity55 attrition characteristics of supported iron fischer–tropsch catalysts. Appl. Catal. A General 196. doi:10.1016/S0926-860X(99)00462-7

Ojeda, M., Nabar, R., Nilekar, A. U., Ishikawa, A., Mavrikakis, M., and Iglesia, E. (2010). Co activation pathways and the mechanism of fischer–tropsch synthesis. J. Catal. 272. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2010.04.012

Okonye, L. U., Yao, Y., Ren, J., Liu, X., and Hildebrandt, D. (2023). A perspective on the activation energy dependence of the fischer-tropsch synthesis reaction mechanism. Chem. Eng. Sci. 265, 118259. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2022.118259

Opeyemi Otun, K., Yao, Y., Liu, X., and Hildebrandt, D. (2021). Synthesis, structure, and performance of carbide phases in fischer-tropsch synthesis: a critical review. Fuel 296. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2021.120689

Ostadi, M., Rytter, E., and Hillestad, M. (2019). Boosting carbon efficiency of the biomass to liquid process with hydrogen from power: the effect of h2/co ratio to the fischer-tropsch reactors on the production and power consumption. Biomass Bioenergy 127. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2019.105282

Papeta, O. P., Sulima, S. I., Bakun, V. G., Zubkov, I. N., Saliev, A. N., and Yakovenko, R. E. (2023). Fischer–tropsch synthesis over bifunctional catalysts based on hbeta zeolite. Pet. Chem. 63, 737–745. doi:10.1134/S0965544123060063

Patzlaff, J., Liu, Y., Graffmann, C., and Gaube, J. (1999). Studies on product distributions of iron and cobalt catalyzed fischer–tropsch synthesis. Appl. Catal. A General 186. doi:10.1016/S0926-860X(99)00167-2

Patzlaff, J., Liu, Y., Graffmann, C., and Gaube, J. (2002). Interpretation and kinetic modeling of product distributions of cobalt catalyzed fischer–tropsch synthesis. Catal. Today 71. doi:10.1016/S0920-5861(01)00465-5

Peng, X., Cheng, K., Kang, J., Gu, B., Yu, X., Zhang, Q., et al. (2015). Impact of hydrogenolysis on the selectivity of the fischer-tropsch synthesis: diesel fuel production over mesoporous zeolite-y-supported cobalt nanoparticles. Angewandte Chemie Int. ed. Engl. 54, 4553–4556. doi:10.1002/anie.201411708

Pichler, H., and Schulz, H. (1970). Neuere erkenntnisse auf dem gebiet der synthese von kohlenwasserstoffen aus co und h2. Chem. Ing. Tech. 42. doi:10.1002/cite.330421808

Puga, A. V. (2018). On the nature of active phases and sites in co and co 2 hydrogenation catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 8. doi:10.1039/C8CY01216D

Qi, Y., Yang, J., and Holmen, A. (2015). Recent progresses in understanding of co-based fischer–tropsch catalysis by means of transient kinetic studies and theoretical analysis. Catal. Lett. 145. doi:10.1007/s10562-014-1419-x

Quek, X.-Y., Guan, Y., van Santen, R. A., and Hensen, E. J. M. (2011). Unprecedented oxygenate selectivity in aqueous-phase fischer-tropsch synthesis by ruthenium nanoparticles. ChemCatChem 3. doi:10.1002/cctc.201100219

Rafati, M., Wang, L., and Shahbazi, A. (2015). Effect of silica and alumina promoters on co-precipitated fe–cu–k based catalysts for the enhancement of co2 utilization during fischer–tropsch synthesis. J. CO2 Util. 12. doi:10.1016/j.jcou.2015.10.002

Riedel, T., Claeys, M., Schulz, H., Schaub, G., Nam, S.-S., Jun, K.-W., et al. (1999). Comparative study of fischer–tropsch synthesis with h2/co and h2/co2 syngas using fe- and co-based catalysts. Appl. Catal. A General 186, 201–213. doi:10.1016/S0926-860X(99)00173-8

Rytter, E., and Holmen, A. (2015). Deactivation and regeneration of commercial type fischer-tropsch co-catalysts—a mini-review. Catalysts 5. doi:10.3390/catal5020478

Rytter, E., and Holmen, A. (2017). Perspectives on the effect of water in cobalt fischer–tropsch synthesis. ACS Catal. 7. doi:10.1021/acscatal.7b01525

Rytter, E., Yang, J., Borg, Ø., and Holmen, A. (2020). Significance of c3 olefin to paraffin ratio in cobalt fischer–tropsch synthesis. Catalysts 10. doi:10.3390/catal10090967

Sartipi, S., Makkee, M., Kapteijn, F., and Gascon, J. (2014). Catalysis engineering of bifunctional solids for the one-step synthesis of liquid fuels from syngas: a review. Catal. Sci. Technol. 4. doi:10.1039/c3cy01021j

Satterfield, C. N., Hanlon, R. T., Tung, S. E., Zou, Z. M., and Papaefthymiou, G. C. (1986). Effect of water on the iron-catalyzed fischer-tropsch synthesis. DOE/PC/80015-T1. Cambridge, USA: Massachusetts Inst. of Tech., doi:10.1021/i300023a007

Satthawong, R., Koizumi, N., Song, C., and Prasassarakich, P. (2013). Bimetallic fe–co catalysts for co2 hydrogenation to higher hydrocarbons. J. CO2 Util. 3-4, 102–106. doi:10.1016/j.jcou.2013.10.002

Schulz, H. (2007). Comparing fischer-tropsch synthesis on iron- and cobalt catalysts: the dynamics of structure and function. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 163. doi:10.1016/s0167-2991(07)80479-4

Schulz, H. (2020). Confinements on growth sites of fischer-tropsch synthesis, manifesting in hydrocarbon-chain branching – nature of growth site and growth-reaction. Appl. Catal. A General 602. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2020.117695

Shafer, W., Gnanamani, M., Graham, U., Yang, J., Masuku, C., Jacobs, G., et al. (2019). Fischer–tropsch: product selectivity–the fingerprint of synthetic fuels. Catalysts 9. doi:10.3390/catal9030259

Shi, B., Keogh, R. A., and Davis, B. H. (2005). Fischer–tropsch synthesis: the formation of branched hydrocarbons in the fe and co catalyzed reaction. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 234. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2005.02.024

Shi, B., Wu, L., Liao, Y., Jin, C., and Montavon, A. (2014). Explanations of the formation of branched hydrocarbons during fischer–tropsch synthesis by alkylidene mechanism. Top. Catal. 57. doi:10.1007/s11244-013-0201-4

Sineva, L., Mordkovich, V., Asalieva, E., and Smirnova, V. (2023). Zeolite-containing co catalysts for fischer–tropsch synthesis with tailor-made molecular-weight distribution of hydrocarbons. Reactions 4. doi:10.3390/reactions4030022

Speight, J. G. (2016). Production of syngas, synfuel, bio-oils, and biogas from coal, biomass, and opportunity fuels. Fuel Flex. Energy Gener., 145–174. doi:10.1016/B978-1-78242-378-2.00006-7

Storsater, S., Borg, O., Blekkan, E., and Holmen, A. (2005). Study of the effect of water on fischer–tropsch synthesis over supported cobalt catalysts. J. Catal. 231. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2005.01.036

Straß-Eifert, A., van der Wal, L. I., Hernández Mejía, C., Weber, L. J., Yoshida, H., Zečević, J., et al. (2021). Bifunctional co–based catalysts for fischer–tropsch synthesis: descriptors affecting the product distribution. ChemCatChem 13, 2726–2742. doi:10.1002/cctc.202100270

Shamzhy, M., Opanasenko, M., Concepción, P., and Martínez, A. (2019). New trends in tailoring active sites in zeolite-based catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48 (4), 1095–1149. doi:10.1039/C8CS00887F

Teng, B., Zhang, C., Yang, J., Cao, D., Chang, J., Xiang, H., et al. (2005). Oxygenate kinetics in fischer-tropsch synthesis over an industrial fe/mn catalyst. Fuel 84, 791–800. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2004.12.008

ten Have, I. C., and Weckhuysen, B. M. (2021). The active phase in cobalt-based fischer-tropsch synthesis. Chem. Catal. 1, 339–363. doi:10.1016/j.checat.2021.05.011

Thybaut, J. W., Laxmi Narasimhan, C. S., Denayer, J. F., Baron, G. V., Jacobs, P. A., Martens, J. A., et al. (2005). Acid-metal balance of a hydrocracking catalyst: ideal versus nonideal behavior. Industrial Eng. Chem. Res. 44. doi:10.1021/ie049375

Todic, B., Ma, W., Jacobs, G., Davis, B. H., and Bukur, D. B. (2014). Co-insertion mechanism based kinetic model of the fischer–tropsch synthesis reaction over re-promoted co catalyst. Catal. Today 228. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2013.08.008

Todić, B., Ordomsky, V. V., Nikačević, N. M., Khodakov, A. Y., and Bukur, D. B. (2015). Opportunities for intensification of fischer–tropsch synthesis through reduced formation of methane over cobalt catalysts in microreactors. Catal. Sci. Technol. 5. doi:10.1039/C4CY01547A

Unglaub, C., and Jess, A. (2023). Enhancing kerosene selectivity of fischer-tropsch synthesis by periodical pore drainage via hydrogenolysis. Catal. Res. 3. doi:10.21926/cr.2303022

van de Loosdrecht, J., Botes, F. G., Ciobica, I. M., Ferreira, A., Gibson, P., Moodley, D. J., et al. (2013). “Fischer–tropsch synthesis: catalysts and chemistry,” in Comprehensive inorganic chemistry II (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier). doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097774-4.00729-4

van Santen, R. A., Ghouri, M., and Hensen, E. M. J. (2014). Microkinetics of oxygenate formation in the fischer-tropsch reaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16. doi:10.1039/C3CP54950J

van Santen, R. A., and Markvoort, A. J. (2013). Chain growth by co insertion in the fischer–tropsch reaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15. doi:10.1002/cctc.201300173

van Santen, R. A., Markvoort, A. J., Filot, I. A. W., Ghouri, M. M., and Hensen, E. J. M. (2013). Mechanism and microkinetics of the fischer-tropsch reaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15. doi:10.1039/C3CP52506F

Wang, C., Du, J., Zeng, L., Li, Z., Dai, Y., Li, X., et al. (2023a). Direct synthesis of extra-heavy olefins from carbon monoxide and water. Nat. Commun. 14, 1857. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-37599-2

Wang, P., Chen, W., Chiang, F.-K., Dugulan, A. I., Song, Y., Pestman, R., et al. (2018). Synthesis of stable and low-CO 2 selective ε-iron carbide Fischer-Tropsch catalysts. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau2947. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aau2947

Wang, W., Toshcheva, E., Ramirez, A., Shterk, G., Ahmad, R., Caglayan, M., et al. (2023b). Bimetallic fe–co catalysts for the one step selective hydrogenation of co 2 to liquid hydrocarbons. Catal. Sci. Technol. 13, 1527–1540. doi:10.1039/D2CY01880B

Wang, Y., Kazumi, S., Gao, W., Gao, X., Li, H., Guo, X., et al. (2020). Direct conversion of co2 to aromatics with high yield via a modified fischer-tropsch synthesis pathway. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 269, 118792. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.118792

Wang, Z., Mai, K., Kumar, N., Elder, T., Groom, L. H., and Spivey, J. J. (2017). Effect of steam during fischer–tropsch synthesis using biomass-derived syngas. Catal. Lett. 147. doi:10.1007/s10562-016-1881-8

Weber, J. L., Del Martínez Monte, D., Beerthuis, R., Dufour, J., Martos, C., de Jong, K. P., et al. (2021). Conversion of synthesis gas to aromatics at medium temperature with a fischer tropsch and zsm-5 dual catalyst bed. Catal. Today 369, 175–183. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2020.05.016

Weitkamp, J. (2012). Catalytic hydrocracking—mechanisms and versatility of the process. ChemCatChem 4. doi:10.1002/cctc.201100315

Wolf, M., Fischer, N., and Claeys, M. (2020). Water-induced deactivation of cobalt-based fischer–tropsch catalysts. Nat. Catal. 3. doi:10.1038/s41929-020-00534-5

Wolf, M., Mutuma, B. K., Coville, N. J., Fischer, N., and Claeys, M. (2018). Role of co in the water-induced formation of cobalt oxide in a high conversion fischer–tropsch environment. ACS Catal. 8. doi:10.1021/acscatal.7b04177

Xing, C., Li, M., Zhang, G., Noreen, A., Fu, Y., Yao, M., et al. (2021). Syngas to isoparaffins: rationalizing selectivity over zeolites assisted by a predictive isomerization model. Fuel 285, 119233. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2020.119233

Yu, H., Wang, C., Lin, T., An, Y., Wang, Y., Chang, Q., et al. (2022). Direct production of olefins from syngas with ultrahigh carbon efficiency. Nat. Commun. 13, 5987. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-33715-w

Yu, R. P., Darmon, J. M., Milsmann, C., Margulieux, G. W., Stieber, S. C. E., DeBeer, S., et al. (2013). Catalytic hydrogenation activity and electronic structure determination of bis(arylimidazol-2-ylidene)pyridine cobalt alkyl and hydride complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 13168–13184. doi:10.1021/ja406608u

Zhai, P., Li, Y., Wang, M., Liu, J., Cao, Z., Zhang, J., et al. (2021). Development of direct conversion of syngas to unsaturated hydrocarbons based on fischer-tropsch route. Chem 7, 3027–3051. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2021.08.019

Zhang, Q., Kang, J., and Wang, Y. (2010). Development of novel catalysts for fischer-tropsch synthesis: tuning the product selectivity. ChemCatChem 2. doi:10.1002/cctc.201000071

Zhang, Y., Yao, Y., Chang, J., Lu, X., Liu, X., and Hildebrandt, D. (2020). Fischer–tropsch synthesis with ethene co–feeding: experimental evidence of the co–insertion mechanism at low temperature. React. Eng. Kinet. Catal. 66. doi:10.1002/aic.17029

Zhao, H., Liu, J.-X., Yang, C., Yao, S., Su, H.-Y., Gao, Z., et al. (2021). Synthesis of iron-carbide nanoparticles: identification of the active phase and mechanism of fe-based fischer–tropsch synthesis. CCS Chem. 3. doi:10.31635/ccschem.020.202000555

Keywords: Fischer–Tropsch synthesis, reaction mechanism, CO2 hydrogenation, bifunctional catalysts, sustainable aviation fuel

Citation: Keunecke A, Dossow M, Dieterich V, Spliethoff H and Fendt S (2024) Insights into Fischer–Tropsch catalysis: current perspectives, mechanisms, and emerging trends in energy research. Front. Energy Res. 12:1344179. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2024.1344179

Received: 25 November 2023; Accepted: 19 February 2024;

Published: 24 April 2024.

Edited by:

Cong Luo, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Lisheng Guo, Anhui University, ChinaBowen Lu, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China

Navid Khallaghi, The University of Manchester, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2024 Keunecke, Dossow, Dieterich, Spliethoff and Fendt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marcel Dossow, bWFyY2VsLmRvc3Nvd0B0dW0uZGU=; Sebastian Fendt, c2ViYXN0aWFuLmZlbmR0QHR1bS5kZQ==

Arthur Keunecke

Arthur Keunecke Marcel Dossow

Marcel Dossow Vincent Dieterich

Vincent Dieterich