- 1UKM-Graduate School of Business, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Malaysia

- 2Global Entrepreneurship Research and Innovation Centre, Kota Bharu, Malaysia

- 3Faculty of Business Administration, Laval University, Quebec, QC, Canada

- 4College of Business Administration, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia

- 5Faculty of Entrepreneurship and Business, Kota Bharu, Malaysia

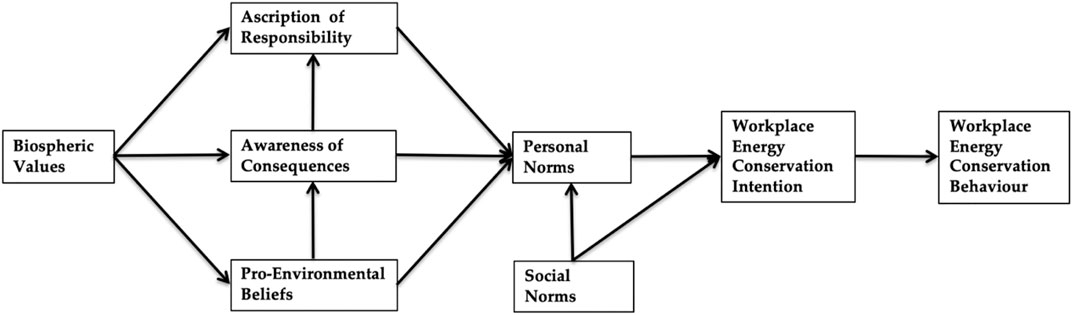

A country’s energy usage can depict the development of its economy. Excessive energy consumption generates carbon emissions that degrade the climate and present challenges for sustainable global development. China is achieving economic development with excessive energy consumption and excessive carbon emissions, damaging the climate. As more energy is consumed at workplaces than in households and other buildings, energy conservation behaviors at workplaces can help mitigate environmental issues. In this study, we explore energy conservation behaviors in the workplace using the value-belief-norm (VBN) theory that has been extended and tested with survey data collected from China. Online survey-based data were collected from a total of 1,061 respondents and analyzed with partial least square regression structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). The results of our analysis indicate that biospheric values significantly predict pro-environment beliefs, awareness of consequences, and ascription of responsibility. Moreover, pro-environment beliefs positively affect awareness of consequences, and awareness of consequences positively affects the ascription of responsibility. Findings further revealed that pro-environment beliefs, awareness of consequences, an ascription of responsibility, and social norms positively affect personal norms. Furthermore, social and personal norms lead to intentions to engage in energy conservation behavior, which influences energy conservation behavior in the workplace. The current study contributes to our knowledge and understanding about workplace energy conservation behaviors by constructing biospheric values that lead to developing the necessary beliefs and norms to activate energy conservation behaviors. Policy and managerial implications are reported, which involve inculcating the necessary values and beliefs that generate norms that lead to pro-climate behavior.

Introduction

The transformational economic success achieved at the global level has led to the degradation of the environment. The global environment has undergone changes due to industrialization, the extensive use of fossil-fuel-based energy, air pollution due to transportation, massive waste generation, and natural calamities, triggering climatic changes worldwide (Ünal et al., 2019). Growing concerns among consumers have encouraged the development of more sustainable forms of consumption; policymakers and industries are attempting to promote responsible consumption and reduce the impact of daily activities on the environment (Sánchez et al., 2015).

At the workplace, energy is consumed by lighting, cooling, heating systems; computers; and other relevant equipment necessary for business activities (Chen and Liu 2020). Energy is a significant input for the performance of production and service industries (Kim and Seock 2019). Energy conservation must be achieved through conservative technological innovations and behavioral changes necessary to reduce unnecessary energy consumption at the workplace (Leygue et al., 2017). Most of the literature has overlooked the importance of the human behavioral consumption aspect that can offer significant insights into individual conservational behaviors. Changing organizational routines, training, and the development of conservative workplace norms encourages workplace energy conservational behaviors (Zhang et al., 2014). Few studies have incorporated workplace incentive programs that enable conservational energy behaviors (Chen and Liu, 2020). Monetary incentives may not yield workplace energy conservational behaviors. Instead, training that activates these norms can lead to behavioral change towards workplace energy conservational behaviors among employees.

Energy conservation at the household level and the workplace is determined by individual innate values and beliefs as well as contextual factors (Kim et al., 2016). Energy conservation is pro-environmental behavior and has separate public and private attributes (Yildirim and Semiz, 2019). At the personal level, energy conservation is related to cost-saving and less associated with environmental commitment (Kim and Seock, 2019). However, in the workplace, costs are not on the employees, and environmental commitment and concern for the organization require behaving in a pro-environment manner (Zhang et al., 2020). A higher level of congruence is required between the values and beliefs to establish the proper norms to behave pro-environmentally (Han et al., 2016). Energy conservation is an extra-role behavior based on intrinsic motivation (Chen and Liu, 2020). The exploration of employees’ values and norms empowers the construction of the necessary infrastructure for energy conservation behavior at the workplace. Building and promoting the right values and norms for employees strengthen social norms to save electricity at the workplace (Leygue et al., 2017). To bridge this gap, we extend the VBN with social norms and actual energy conservation behavior at the workplace.

Commercial electricity consumption is necessary for a nation’s industrial development (Chen and Liu, 2020). However, in order to reduce the impact of commercial energy consumption, an inclusive response is required from both management and employees (Gkargkavouzi et al., 2019). China has become one of the most rapidly growing economies, with high energy consumption for commercial purposes and workplaces. China’s energy consumption has reached 4.64 billion tons of coal equivalent (CEC, 2020). This increasing energy consumption has impacted the environment and human health (Zhang et al., 2020). To mitigate the harmful impact of industrial development on the climate and human life, in 2016, the United Nations (UN) obtained the consent of 189 member countries to work toward Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) until the end of 2030 (Chen and Liu, 2020). As a signatory of UNSDGs, China is exploring how to improve its energy conservation practices and achieve energy efficiency among households and workplaces.

Global economy complexity has led to the increased use of natural resources and energy for production purposes (Hirstsuka et al., 2018). The commercial and industrial use of energy has increased in recent times, with 85% of total energy consumed by industries (CEC, 2020), contributing to greenhouse gas (GHGs) emissions three times more than household energy consumption (Chen and Liu, 2020). Thus, organizations and institutions must take responsibility for environmental and social sustainability. Employees’ workplace energy consumption behaviors are a significant reason for uneconomical energy consumption in organizational settings, as employees do not directly pay for their energy consumption at work (Sánchez et al., 2015). Correcting employees’ behaviors can help reduce unnecessary energy consumption at the workplace and mitigate environmental issues.

The present study explores the application of the VBN model’s casual chain on energy conservation behavior among Chinese employees in the workplace. We extended the VBN with social norms impacting personal norms and intentions to save energy at the workplace. Furthermore, the comprehension of the workplace’s energy conservation behavior helps formulate the right policy and practical guidelines to promote energy conservation behaviors.

Literature review

At the firm level, conservational organizational stance guides fellow employees’ sustainable behavior and help to achieve environmental performance. National health services (NHS) Trust of the UK is a fine example of achieving conservational behaviors from the workers (Young et al., 2015). NHS implement corporate social responsibility (CSR) and involve its employees in increasing recycling, reducing energy use, and minimizing the NHS operation’s greenhouse gas emissions. Employee participation helps to promote the turning off the equipment, unnecessary lights and cooling and heating systems lead to significant saving that demonstrates the saving of 2,200 tons of carbon use (NHS, 2022).

Theoretical foundation

Norm activation theory (NAT) offers a framework for discussing prosocial behaviors triggered by individuals’ personal moral obligations. Stern (2000) postulates the value-belief-norm theory (VBN) grounded in the NAT, taking the broader beliefs about the biosphere caused by human actions. VBN causally explains environmental realization initiation at the individual level according to an individual’s personal values (Wensing et al., 2019). The activation of personal and social norms empowers the intention and later pro-environmental behaviors. Pro-environmental behaviors are the cognizable actions taken to reduce the adverse effects of one’s actions on nature, minimize resource usage, and reduce wastage or energy consumption (Wynveen et al., 2015).

Values are imperative controlling principles that guide an individual’s personal life. Values develop different beliefs and act as organized systems that direct one’s attitude and behaviors (Wensing et al., 2019). Stern et al. propagated three values: egoistic values, social-altruistic values, and biospheric values, which positively promote environmental behaviors (Walton and Austin, 2011). Biospheric values are the internal feelings concerned with non-human species and the environment (Ünal et al., 2019). Environmental threats are real and have caused many climatic changes. An awareness of the consequences of human actions builds the necessary belief to behave in a specific manner (van Riper and Kyle, 2014). Awareness of consequences involves a level of personal awareness of the consequences of environmental threats around an individual (López-Mosquera and Sánchez, 2012). Awareness generates a sense of responsibility to act. Ascription of responsibility is the individual responsiveness to initiate actions that can avert consequences by engendering a precise sense of responsibility (López-Mosquera and Sánchez, 2012; Yildirim and Semiz, 2019).

Personal values generate beliefs, as proposed by the VBN theory. Pro-environmental beliefs concern taking sustainable actions for the environment in a collaborative manner (López-Mosquera and Sánchez, 2012). As the individual develops beliefs concerning the environment, the awareness of consequences develops. Personal values and beliefs influence household energy conservation behavior (Yildirim and Semiz, 2019). However, the literature consistently proposes a significant relationship between values and beliefs (Ünal et al., 2019).

According to newly internalized self-standards, personal norms are innate feelings of obligation that initiate the requirement to change one’s personal behaviors (Choi et al., 2015). The interplay of cognitive, emotional, and social factors originates from perceived obligations to behave more responsibly. Pro-social emotions of guilt trigger correct personal behaviors, reducing harm to the general public or in private settings and causing individuals to learn new prosocial behaviors, reducing the environmental impact (Chen and Liu, 2020). Social norms help individuals internalize new behaviors and formulate new personal norms (Kim and Seock, 2019).

In daily life, social context and normative lifestyles greatly influence people’s behavior (Han et al., 2016). Social norms involve a general public understanding to behave in a socially acceptable manner, such as toward the environment, and contribute to forming a personal belief towards the environment (Kim and Seock, 2019). Social norms are powerful mechanisms that influence individuals’ intentions and actions. The concept of social norms is not explicitly included in VBN theory (Liu et al., 2018). However, social norms are a significant predictor of environment-related personal norms. Social norms depict collective expectative behavior as accepted by the general public (Maichum et al., 2016). Environmental issues are complex, and social norms are mostly unfavorable toward exhibiting pro-environmental norms and behaviors. Social norms influence individuals’ daily lives and facilitate behavioral change (Sánchez et al., 2015). Social norms require further exploration of environmental behaviors that should be included in the VBN model. However, social norms influence motivation to engage in pro-environmental behaviors (López-Mosquera and Sánchez, 2012).

Intentions are mindful action plans for individuals that explicitly activate the actual behavior required to correct the matter at hand (Maichum et al., 2016). Intentions are the most appropriate predictors of human behavior and an essential part of VBN (Gkargkavouzi et al., 2019). The energy conservation intention at the workplace is a kind of intrinsic motivation. It triggers the internal obligation to save energy at the workplace and prompts responsible behavior to this end (Chen and Knight, 2014).

Hypotheses development

Effect of Biospheric values beliefs

Biospheric values refer to the innate understanding that the environment and other species are essential for life. Biospheric values nurture positive beliefs regarding taking take care of the environment. López-Mosquera and Sánchez (2012) claim that individuals’ biospheric values significantly induce pro-environmental beliefs. Liu et al. (2018) found that biospheric values positively and significantly influence Chinese students’ pro-environmental beliefs to execute pro-environmental behaviors in public settings. Taking note of the above evidence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis (H1):. Biospheric values positively affect pro-environmental beliefs among working adults.The conception of consequences is linked with the understanding that human actions impact individuals, society, and ecology (van Riper and Kyle, 2014). The causal chain of biospheric values impacts the awareness of consequences; individual actions influence the environmental aspect of energy conservation (Leygue et al., 2017). Individual biospheric values help develop an awareness of the consequences of individual actions (Wensing et al., 2019). Furthermore, Hirstsuka et al. (2018) reported the significant impact of individual biospheric values on the awareness of consequences among Japanese car consumers. Yildirim and Semiz (2019) find that biospheric values influence the awareness of consequences for water conservation behaviors in testing the value-belief-value theory for the Turkish samples. Therefore, for the current study, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H2):. Biospheric values positively affect the awareness of consequences among working adults.Taking responsibility to correct mistakes helps build the belief that corrective actions are possible and necessary to perform (Kim et al., 2016). Realizing the necessity of taking responsibility encourages individuals to mend their actions and make efforts to take necessary actions for problem-solving (van Riper and Kyle, 2014). Yildirim and Semiz (2019) found that biospheric values are significantly linked to the ascription of responsibility to use water sustainably among Turkish teachers. Furthermore, Hirstsuka et al. (2018) postulate that individual biospheric values significantly influence the ascription of responsibility among Japanese car consumers. Therefore, for the current study, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H3):. Biospheric values positively affect the ascription of responsibility among working adults.

Effect of pro-environmental beliefs

Climate-related individual beliefs assist in the promotion of other beliefs (Gkargkavouzi et al., 2019). López-Mosquera and Sánchez (2012) suggest that the Spanish sample’s pro-environmental beliefs promote the awareness of consequences. Individuals with pro-environmental beliefs are more likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviors, as they know the consequences of climatic issues (Kim et al., 2016). Recently, Fornara et al. (2020) postulated that pro-environmental beliefs influence the awareness of consequences among a European sample for nature-related issues. Based on the provided discussion, we offer the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H4):. Pro-environmental beliefs positively affect working adults’ awareness of consequences.Belief also impacts norms, such as developing a pro-environmental belief that prompts personal norms (Hirstsuka et al., 2018). Individuals develop personal norms to take good care of the environment. López-Mosquera and Sánchez (2012) find that their Spanish sample’s pro-environmental beliefs promote personal norms. van Riper and Kyle (2014) postulate that pro-environmental beliefs influence US respondents’ personal norms regarding visiting national parks. Gkargkavouzi et al. (2019) document the significant impact of individual pro-environmental beliefs on personal norms among a Greek sample. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H5):. Pro-environmental beliefs positively affect working adults’ personal norms.

Awareness of consequences

VBN presents the causal link between the awareness of consequences and the ascription of responsibility for environmental behaviors (Gkargkavouzi et al., 2019). López-Mosquera and Sánchez (2012) postulate that awareness of consequences influences the ascription of responsibility to protect the environment among Spanish people visiting suburban parks. Recently, Fornara et al. (2020) documented the significant effect of the awareness of consequences on the ascription of responsibility for nature-related issues among European respondents. Further, Zhang et al. (2020) found that the awareness of consequences significantly influenced the ascription of responsibility toward adopting environment-mitigating farming practices among Chinese farmers. We thus propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H6):. Awareness of consequences positively affects working adults’ ascription of responsibility.Wynveen et al. (2015) found that the awareness of consequences influences personal norms among people visiting the Great Barrier reef park in Australia. Choi, Jang, and Kandampully (2015) report a significant impact of awareness of consequences on US-based respondents’ personal norms to stay in green hotels. Gkargkavouzi et al. (2019) postulate that the awareness of consequences impacted their Greek samples’ personal norms. We thus present the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H7):. Awareness of consequences positively affects working adults’ personal norms.

Ascription of responsibility

Similarly, VBN projects the impact of the ascription of responsibilities on personal norms toward climatic issues (Han et al., 2016). Lopez-Maosquera and Sanchez (2012) postulate that Spanish respondents’ ascriptions of responsibility impact their personal norms regarding their willingness to pay to enter suburban parks. Furthermore, Zhang et al. (2020) report that the ascription of responsibility influences the personal norms for adopting environment-mitigating farming practices among Chinese farmers. Therefore, we suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H8):. Ascription of responsibility positively affects working adults’ personal norms.

Effect of social norms

Prevailing social norms influence individual norms, as people around individuals support the development of personal norms to behave pro-socially (Chen and Knight, 2014). Pro-social behavior is easy to activate and replicate, as societal norms support activating environmental attitudes (Kim and Seock 2019). Bamberg et al. (2011) find that social norms impact personal norms regarding voluntary car use reduction among German respondents. In a topical study, Kim and Seock (2019) provide evidence that social norms influence young Americans’ personal norms regarding environmentally friendly apparel product purchase behaviors. Taking the lead from the available evidence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H9):. Social norms positively affect working adults’ personal norms.Furthermore, social norms facilitate the execution of conservation behaviors (Leygue et al., 2017). Social norms promote the intention to engage in green behaviors (Maichum et al., 2016). In examining the application of VBN for consumers’ intentions to stay in green hotels, Choi et al. (2015) documented the significant positive impact of subjective norms on the intention to stay in green hotels among US respondents. Gkargkavouzi et al. (2019) postulated that social norms positively and significantly influence the intention to conduct pro-environmental lifestyles. We thus suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H10):. Social norms positively affect workplace energy conservation intentions.

Impact of personal norms

With the development of adequate personal norms, the individual becomes more inclined to engage in green behaviors (van Riper and Kyle, 2014). Personal norms assist in the development of green behavioral intentions (Ünal et al., 2019). For example, in their US sample, Choi et al. (2015) found a significant positive impact of personal norms on the intention to stay in green hotels. In a recent study, Zhang et al. (2020) reported that Chinese agriculture professionals’ personal norms motivate them to start behaving to mitigate the environmental issues related to agriculture practices. The above-reported evidence prompts us to propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H11):. Personal norms positively affect workplace energy conservation intentions.

Workplace energy conservation intention

The intention is a precursor of actual behavior, and the intention to engage in green behaviors positively triggers green behavior. Bamberg et al. (2011) find that behavioral intentions to reduce car use significantly predict the behavior to voluntary reduce car use. Taking energy conservation responsibility at the workplace among Chinese employees increases energy conservation behavior among other employees. We thus propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H12):. Energy conservation intention positively affects energy conservation behavior at the workplace.All hypothesized associations were tested and presented in Figure 1 below.

Research Methodology

Research design

For the current study, a deductive approach was employed with a quantitative method to explore the factors impacting intentions and energy conservation behaviors among the study respondents from China. The data were collected in a cross-sectional manner for this explanatory study. The causal-predict data analysis technique PLS-SEM was utilized to test the hypotheses.

Population and sample

The target population of the current study were full-time employees working in all types of corporations in China. The sample size calculation was performed with G-Power 3.1 with a power of 0.95. Effect size 0.15, with seven predictors. The required sample size was 84 (Faul et al., 2007). Moreover, the minimum threshold of 200 samples was suggested for PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2019). We employed the second-generation statistical analysis technique of structural equation modelling; we decided to collect about 1,000 respondents. The convenience sampling technique was utilized by adding a few qualifying questions to the survey and obtaining respondents’ consent to participate in the study. Data collection was performed online by posting the survey on http://www.wjx.cn/ from October 2020 to November 2020.

Survey instrument

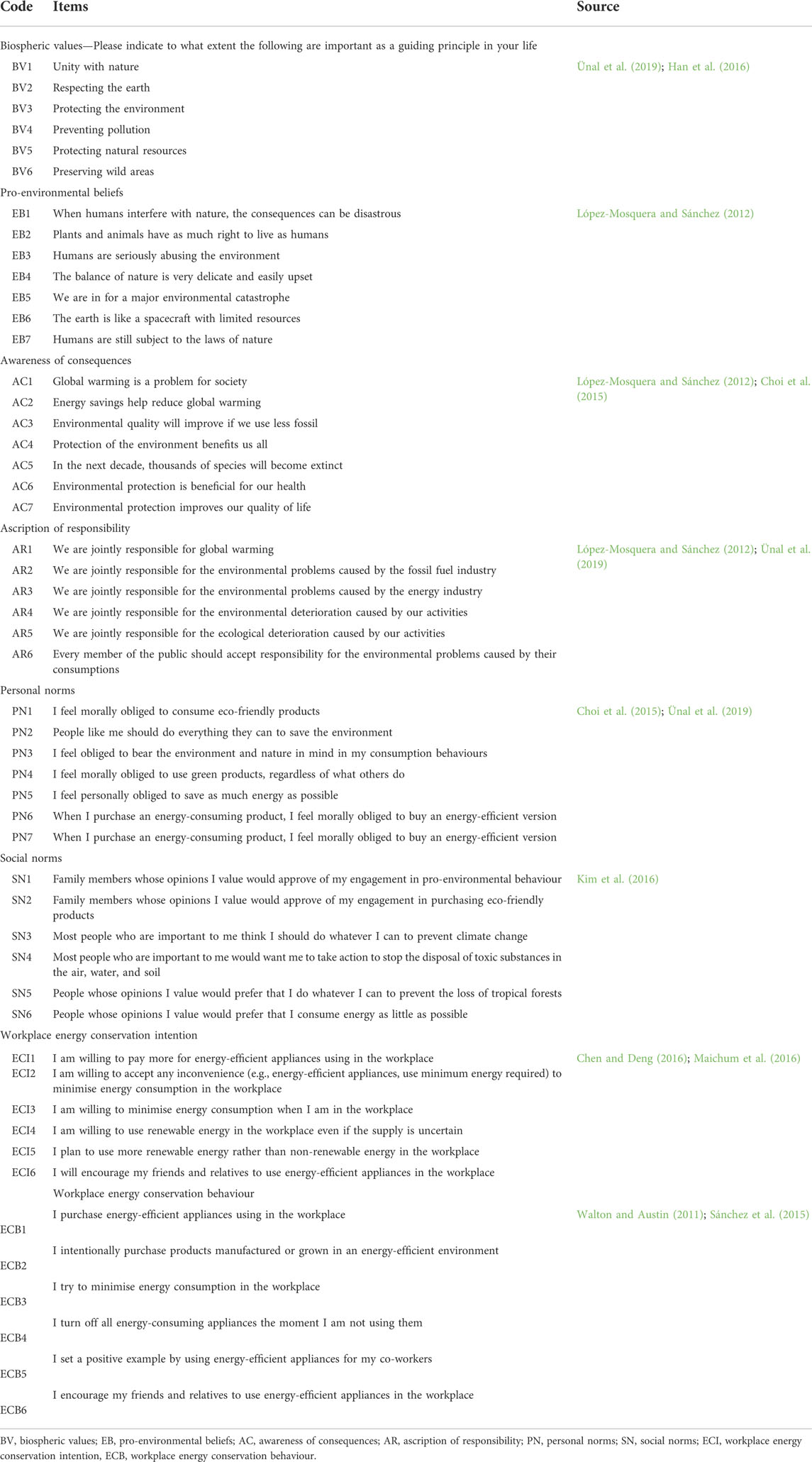

The survey instrument used in this study was a structured questionnaire. All question items were adopted from earlier studies with minor modifications (Table 1). In this study, a seven-point Likert scale (not important at all, not important, slightly not important, neutral, slightly important, important, very important) was used to measure biospheric values, and a seven-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat disagree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat agree, agree and strongly agree) was used to determine other variables. Complete data presented included in the article as Supplementary Material.

Common method bias

Cross-sectional studies are commonly associated with common method variance (CMV), assessed using multiple methodological and statistical tools (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Harman’s one-factor test was applied to determine the effect of CMV as a diagnostic technique for the current study. The single factor accounted for 33.327%, which is below the recommended threshold of 50% in Harman’s one-factor test, thus approving the inconsequential influence of CMV on this study (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Furthermore, we evaluated CMV by following Kock’s (2015) recommendation to test the full collinearity of all constructs. All of the study constructs regressed on the common variable and the variance inflation factor (VIF) value for biospheric values (1.929), pro-environmental beliefs (1.406), awareness of consequences (2.497), an ascription of responsibility (1.687), personal norms (2.061), social norms (1.889), workplace energy conservation intention (2.027), and workplace energy conservation behavior (2.421). All VIF values are less than 5, indicating the absence of bias from the single-source data.

Multivariate normality

Hair et al. (2019) suggest evaluating the data’s multivariate normality before using the SmartPLS. Multivariate normality for the study data was assessed with the Web Power online tool (source: https://webpower.psychstat.org/wiki/tools/index). The calculated Mardia’s multivariate p-value displayed that the study data had a non-normality issue, as the p-values were below 0.05 (Cain et al., 2017).

Data analysis method

Due to the existence of multivariate non-normality in our dataset, we utilized partial least square–structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). Hair et al. (2014) recommended that variance-based structural equation modelling was adopted to analyze the exploratory nature and non-normality issues in this study to provide an in-depth explanation of variance in the structural equation model’s dependent constructs.

The Smart-PLS 3.1 program was employed to analyze the data collected for the current study; PLS-SEM is a multivariate exploratory method for analyzing integrated latent constructs’ path structure (Hair et al., 2019). PLS-SEM empowers researchers to work well with non-normal and small data sets. PLS-SEM is a casual-predictive analytical tool to execute complex models with composites and no specific assumption of goodness-of-fit static requirements (Hair et al., 2014). PLS-SEM analysis was performed in two phases. The first step addressed model estimation, where the models’ construct reliability and validity were evaluated (Hair et al., 2019). Phase two dealt with evaluating correlations of the models and systematic testing of the study path model (Hair et al., 2014). Study analysis performed with r2, Q2, and effect size f2 can explain the endogenous construct’s changes caused by the exogenous constructs (Hair et al., 2019).

Data analysis

Demographic characteristics

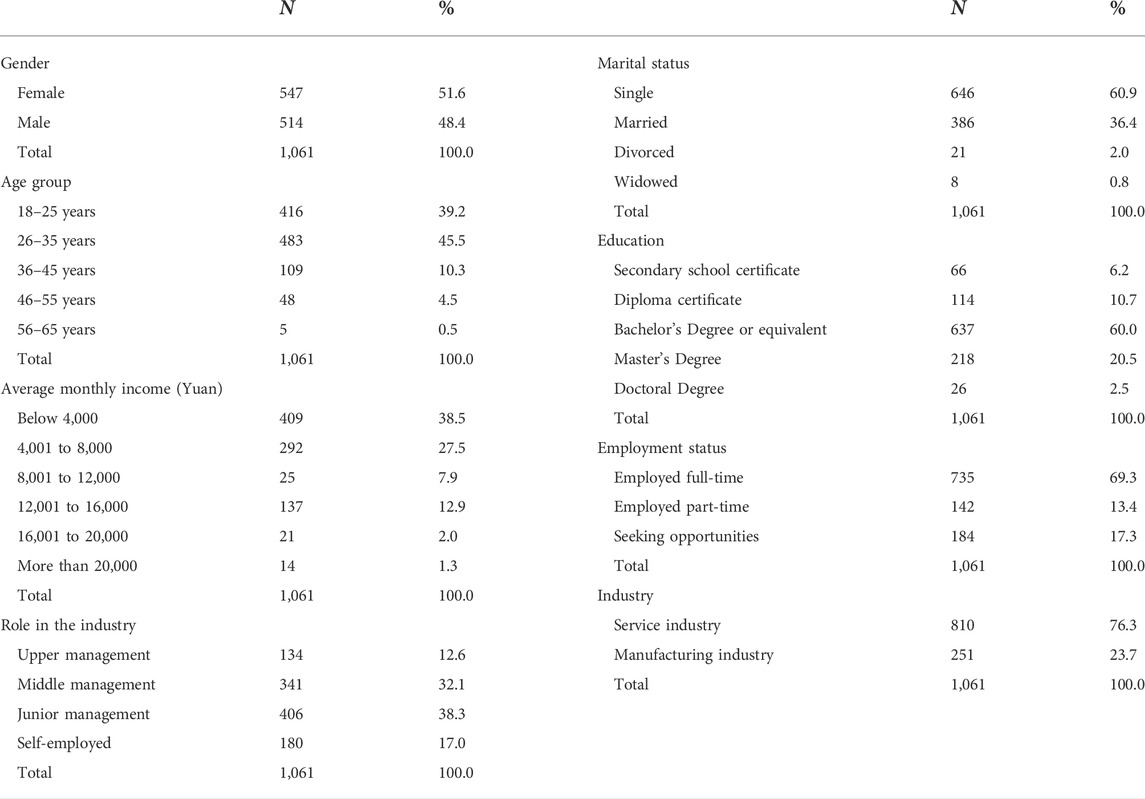

Among the study respondents, 48.4% were men, and 51.6% were women. 60.9% of the study respondents were single, 36.4% were married, 2% were divorced, and the remaining were widowed. Respondents were divided into five age groups: 18–25 (39.2%), 26–35 (45.5%), 36–45 (10.3%), 46–55 (4.5%), and 56–65 years old (0.5%). Among the 1,061 respondents, 6.2% had secondary school-level education, 10.7% had a diploma certificate, 60% had a bachelor’s degree, 20.5% had a master’s degree, and the remaining had a doctoral-level education. Among the survey respondents, 69.3% were full-time employees, and 13.4% worked part-time; the remaining were seeking employment opportunities. As presented in Table 2, among the respondents, 38.5% had a monthly income of less than or up to 4,000 yuan, 27.5% had monthly incomes between 4,001 and 8,000 yuan, 7.9% had monthly incomes between 8,001 and 12,000 yuan, 12.95% of the study respondents had monthly incomes of 12,000 to 16,000 yuan, 2.0% had monthly incomes of 16,001 to 20,000 yuan, and 1.3% of respondents had a monthly income of more than 20,000 yuan. The upper management respondents comprised 12.6% of the sample, 32.1% worked in middle management, and 38.3% worked in junior management ranks. The remaining worked in self-employed settings.

Reliability and validity

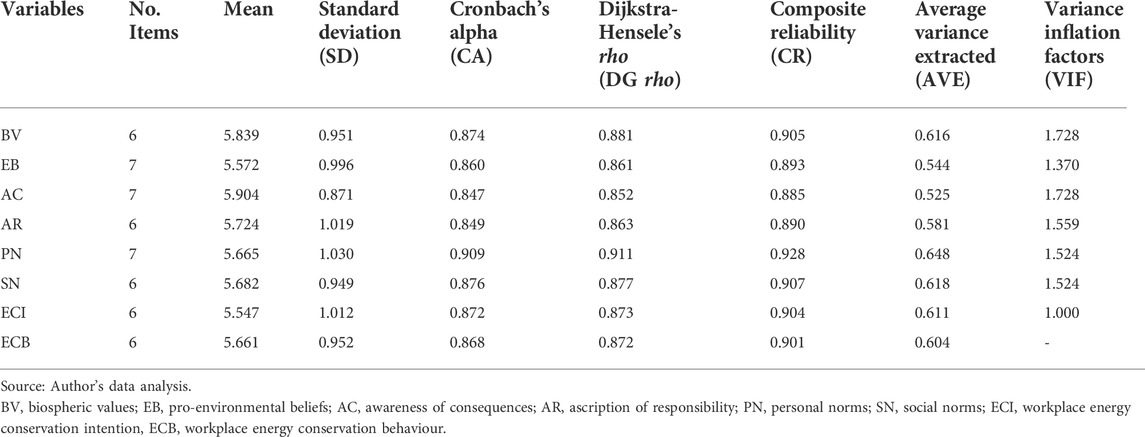

Following the suggestions of Hair et al. (2019), reliabilities for the study’s latent constructs were achieved and appraised by Cronbach’s alpha (CA), Dijkstra-Hensele’s rho, and composite reliability (CR). Cronbach’s alpha values for each construct are well above the threshold of 0.70, and the minimum value of Cronbach’s alpha value achieves 0.847 (Hair et al., 2014). These results are depicted in Table 3. Further, all Dijkstra-Hensele’s rho values of the study constructs are well above the threshold of 0.70, where the minimum value of Dijkstra-Hensele’s rho was 0.852 (Hair et al., 2019). Additionally, CR values were well above the threshold of 0.70, where the lowest CR value was 0.855 (Hair et al., 2014). The average variance extracted (AVE) for all items for each construct must be above the score of 0.50 to establish adequate convergent validity to support the uni-dimensionality concept for each construct (Hair et al., 2019). The items show that constructs have adequate convergent validity (see Table 3). All the variance inflation factor (VIF) values for each construct were well below the threshold of 3.3, revealing no multicollinearity concern (Hair et al., 2014).

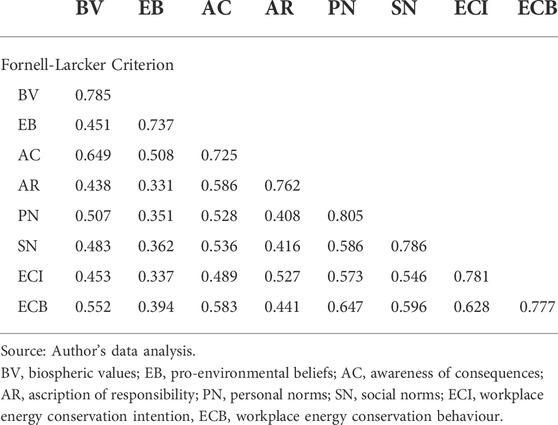

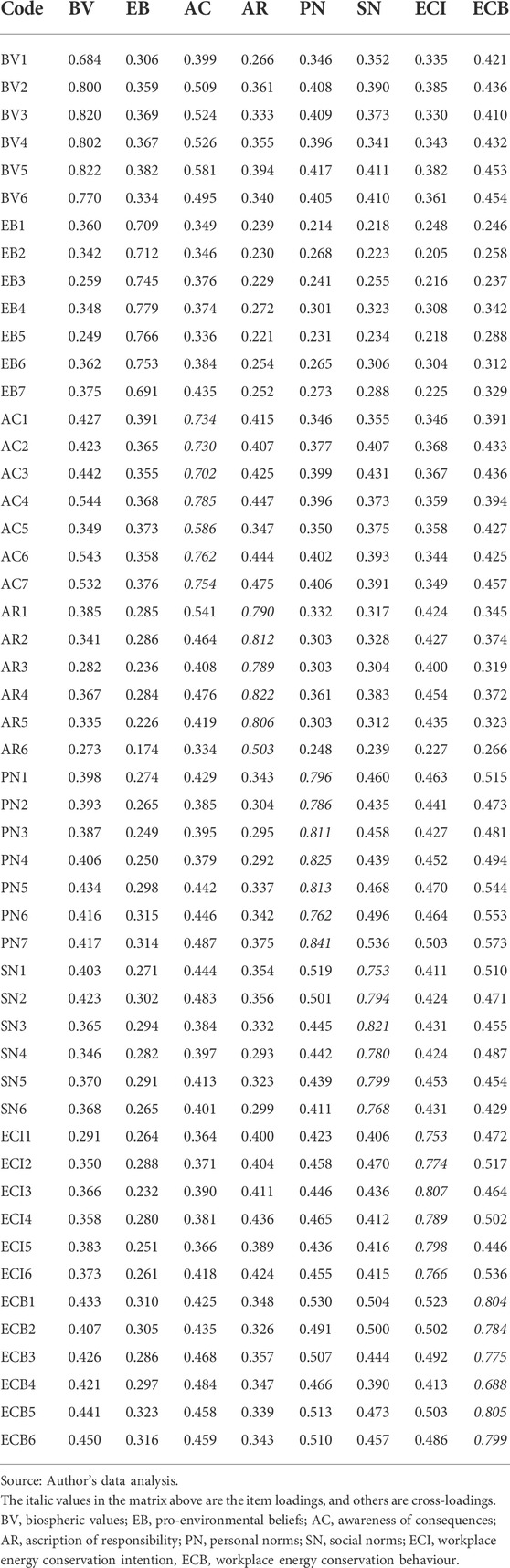

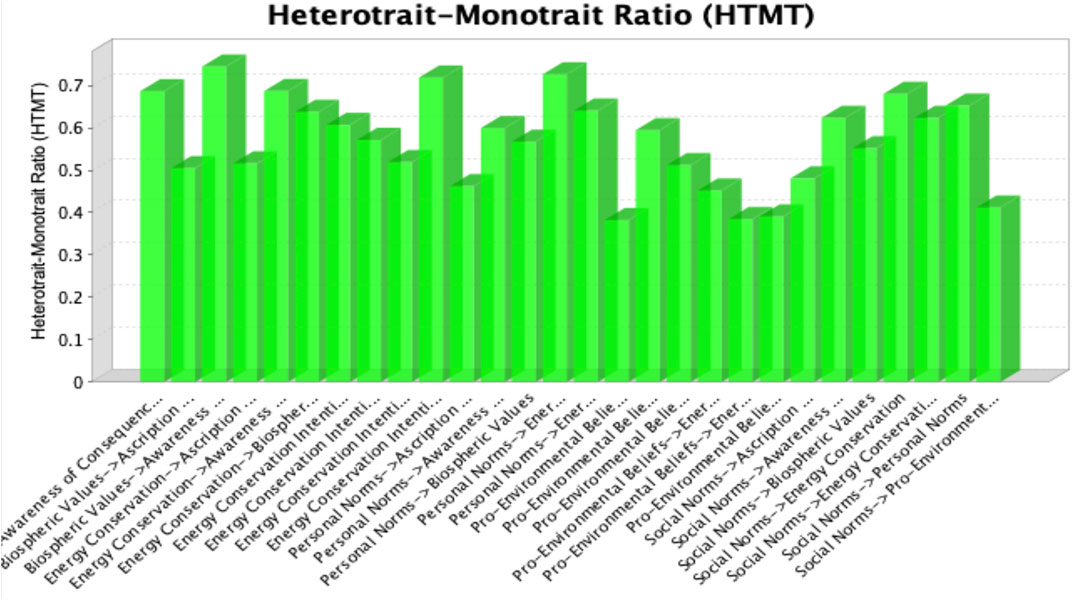

The study’s constructs have fitting discriminant validities (see Table 4). Additionally, the Fornell-Larcker criterion (1981) was utilized to achieve the discriminant validity for each study construct. The Fornell-Larcker criterion is calculated with the square root of a particular construct’s AVE. AVE’s square root for the construct is higher than the correlation among the study’s other constructs (Hair et al., 2019). As for Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (see Figure 2), the study constructs are below the threshold of 0.90 (Hair et al., 2019). Figure 2 shows that the study has sufficient discriminant validity for each construct. The loading and cross-loading values, as presented in Table 5, further confirms the sufficient discriminant validity for each construct.

Path analysis

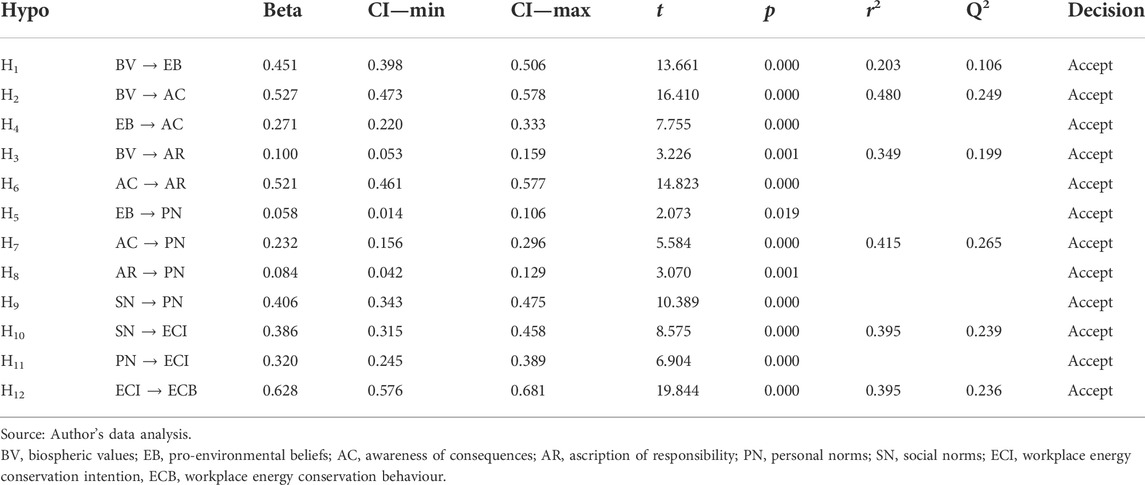

After obtaining the acceptable reliabilities and validities from the structural assessment of the study model, the following measurement assessment was employed to scrutinize the study hypothesis. The r2 value for the biospheric values as exogenous constructs on the pro-environmental belief explains the 20.3% of change in the pro-environmental belief. The predictive relevance (Q2) value for the part of the model is 0.106, representing a considerable predictive relevance (Hair et al., 2014). The r2 value for the two exogenous constructs (i.e., biospheric values and pro-environmental behavior) on the awareness of consequences elucidates the 48% of change in the awareness of climate change consequences. The predictive relevance (Q2) value for the part of the model is 0.249, demonstrating a medium predictive relevance (Hair et al., 2014). The r2 value for the two exogenous constructs (i.e., biospheric values and awareness of consequences) on the ascription of responsibility explains the 34.9% change in the ascription of responsibility. The predictive relevance (Q2) value for the part of the model is 0.199, indicating a medium predictive relevance (Hair et al., 2014).

The r2 value for the four exogenous constructs (i.e., pro-environmental behavior, awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility and social norms) on personal norms elucidates 41.5% of the change in personal norms. The predictive relevance (Q2) value for the part of the model is 0.265, demonstrating a large predictive relevance (Hair et al., 2014). The r2 value for the two exogenous constructs (i.e., social norms and personal norms) on the energy conservation intention explicates the 39.5% change in the energy conservation intention. The predictive relevance (Q2) value for the part of the model is 0.239, signifying a medium predictive relevance (Hair et al., 2014). The adjusted r2 value for the energy conservation intention as exogenous constructs on workplace energy conservation behavior explains the 39.5% change in the workplace’s energy conservation behavior. The predictive relevance (Q2) value for the part of the model is 0.236, representing a medium predictive relevance (Hair et al., 2014).

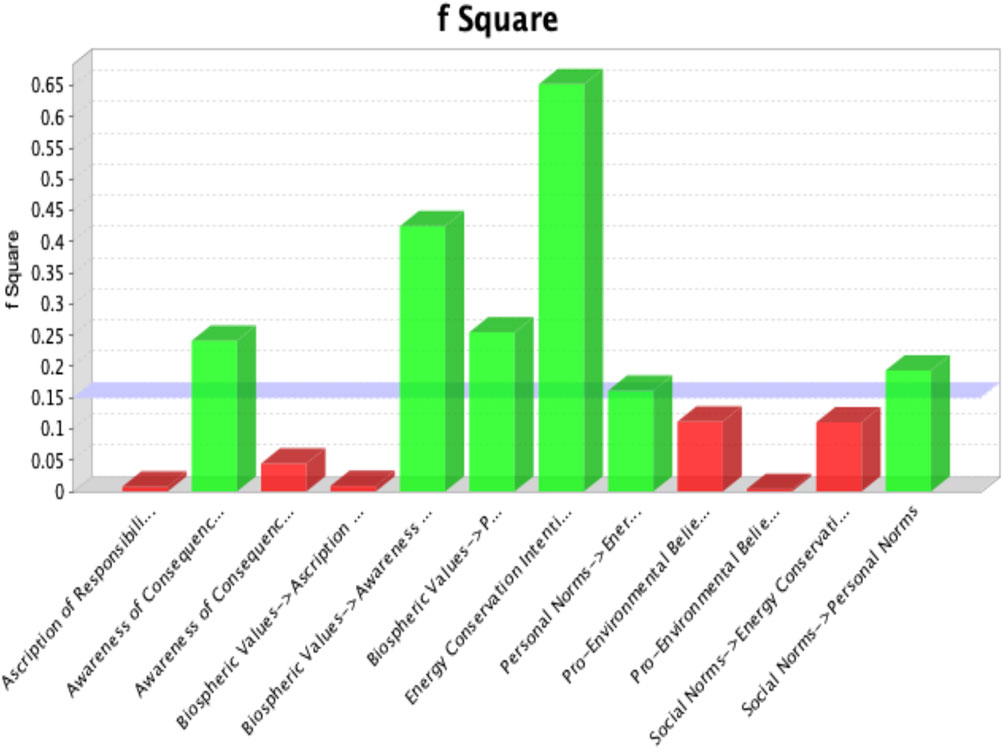

The effect size (f2 values) of each association is presented in Figure 3. Cohen (1988) classified the size of the effects as trivial (0.02), minor (≥0.02), medium (≥0.15), and substantial (≥0.35). Figure 3 revealed a medium effect of biospheric values on pro-environmental belief (f2 value = 0.255), awareness of consequences on ascription of responsibility (f2 value = 0.242), social norms to personal norms (f2 value = 0.194) and social norms to workplace energy conservation intention (f2 value = 0.161). Findings also revealed a substantial effect of biospheric values on awareness of consequences (f2 value = 0.425) and energy conservation intention on workplace energy conservation behavior (f2 value = 0.652). The effect size of the remaining associations is classified as trivial or minor (f2 value < 0.15). PHB and AOC were revealed to have substantial effects on AOC and AOR, respectively, while AOR and IWHD were identified to possess a trivial effect on PNS and AWHD, respectively.

The model’s standardized path values, t-values, and significance levels are illustrated in Table 6. The path coefficient between biospheric values and pro-environmental belief indicates a significant and positive consequence of the biospheric values on pro-environmental behavior. This result presents significant statistical support for H1. The path value for the biospheric values and awareness of consequences shows that the biospheric values’ impact on the awareness of consequences is positive and significant and provides significant statistical support for H2. The path between pro-environmental belief and awareness of consequences, illustrating the influence of pro-environmental behavior on the awareness of consequences, is positive and significant; it provides support for accepting H4. The path coefficient for the biospheric values and ascription of responsibility, representing a positive and significant effect, offers support for the argument that biospheric values affect the ascription of responsibility and offers support for accepting H3. The path from awareness of consequences to the ascription of responsibility, illustrating the influence of the awareness of consequences on the ascription of responsibility, is positive and significant, supporting the acceptance of H6.

The path between pro-environmental belief and personal norms, illustrating the influence of the pro-environmental belief on the personal norms, is positive and significant, delivering substantiation for supporting H5. The path coefficient for awareness of consequences and personal norms indicates a positive and significant effect on awareness of consequences on the personal norms, supporting H7. The path between the ascription of responsibility and personal norms, demonstrating the influence of the ascription of responsibility on personal norms, is positive and significant and provides support for H8. The path coefficient for social and personal norms represents a positive and significant effect, supporting the acceptance of H9.

The path between social norms and energy conservation intention demonstrates the influence of the social norms on the energy conservation intention at the workplace as positive but significant, supporting H10. The path coefficient for the personal norms and energy conservation intention represents a positive and significant effect, supporting H11. The path between energy conservation intention and energy conservation behavior, illustrating the influence of the energy conservation intention and workplace energy conservation behavior, is positive and significant, supporting H12.

Discussion

The current study employed the VBN theory to examine the energy conservation behaviors of Chinese workers in the workplace. The results of this study support the argument that the employees’ biospheric values positively influence their pro-environment beliefs, awareness of consequences, the ascription of responsibility, and personal norms for energy conservation at the workplace. First, our findings suggest that biospheric values influence personal beliefs to act in a pro-environmental manner. Our findings agree with those of Liu et al. (2018) that Chinese students develop pro-environmental beliefs in promoting biospheric values. Additionally, our results support the outcome reported by Hirstsuka et al. (2018) that biospheric values impact the awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility.

Furthermore, individual pro-environmental beliefs significantly impact the awareness of the consequences of energy consumption. The results of our study match the findings reported by Fornara et al. (2020) that people with pro-environmental beliefs are more aware of the consequences of their actions on the environment. Following the VBN causal path, the awareness of consequences promotes the ascription of responsibility toward energy conservation in the workplace. Our findings support those of Zhang et al. (2020) that an awareness of the consequences of energy conservation at the workplace activates the ascription of responsibility to engage in pro-environmental attitudes proactively.

Next, we proposed a causal link between pro-environment beliefs, awareness of consequences, responsibility ascription, and personal norms. Our study results support Zhang et al.’s (2020) findings that farmers’ pro-environmental beliefs and ascription of responsibility were associated with the inculcation of personal norms. Furthermore, the awareness of consequences impacts personal norms that encourage energy conservation in the workplace. The results of our study match those of Gkargkavouzi et al. (2019) that individuals exhibit environmental behaviors in both the private and public sphere.

Social norms also significantly affect personal norms regarding energy conservation practices at the workplace. Social norms make it acceptable to engage in environmental behaviors. The findings of our study are in accordance with the results reported by Kim and Seock (2019) that social norms help build the necessary personal norms to participate in environmental behaviors. Moreover, our study analysis suggests that social and personal norms positively influence the intention to save energy at the workplace. Our study findings support Gkargkavoui et al. (2019) work, which found that social norms influence intentions and the findings of Zhang et al. (2020) that personal norms encourage individuals to engage in pro-environmental behaviors.

Finally, the results of our study indicate that the intention to save energy at the workplace leads to the workplace’s energy conservation behavior. These results are supported by the work of Sánchez et al., 2015, who found that the intention to engage in pro-environmental behavior influences pro-environmental behaviors. The causal link between the VBN confirms that the development value and beliefs help develop the norms to engage in pro-environmental behaviors.

Conclusion

This study aimed to extend and empirically test the VBN model to predict energy conservation behavior among a Chinese sample. The research findings revealed that biospheric values guide the ascription of responsibility, awareness of consequences, and pro-environmental beliefs. Further, pro-environment beliefs generate the awareness of consequences, leading to the ascription of responsibility to save energy at the workplace. This research offers insights into how personal norms develop with different beliefs regarding pro-environment, awareness, and responsibility. The prevailing social norms support personal norms, and social and personal norms aid the development of energy conservation intentions at the workplace. Developing the necessary biospheric values and social norms that facilitate energy conservation is necessary to mitigate the climate issues caused by industrialization. Inclusive efforts empower the achievement of global sustainability, and increased responsibility among individuals can help mitigate environmental issues.

Policy and managerial implications

The current study contributes to energy conservation literature in four ways. First, much of the literature on energy conservation uses the original form of the TPB or VBN (Maichum et al., 2016; Ünal et al., 2019). The current study extends the VNB and incorporates social norms and energy conservation behaviors. Regarding energy conservation behaviors in the workplace, individual biospheric values help develop pro-environmental beliefs that impact the awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility, building the personal norms towards energy conservation. Social norms are also significant for developing conservational personal norms and intentions toward energy conservation (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Gkargkavoui et al., 2019). Energy conservation behaviors are facilitated by personal and social norms, which are necessary preconditions to engage in mitigating climatic issues. The extended VBN performs well and appropriately describes energy conservation. Second, most recent studies have discussed the adoption of energy conservation practices or energy conservation at the household level and energy usage at the workplace. Commercial energy consumption is much larger than that of households (Chen and Knight, 2014). Our study postulates that biospheric values and social norms create conditions that facilitate the appropriate conservational behaviors.

Business managers must develop effective ways to communicate and promote social norms to facilitate energy conservation in the workplace. Firstly, firms’ top management makes energy conservation as the firm’s strategic goal, and the managers run the message of energy conservation from top to bottom (Leygue et al., 2017). Secondly, managers need to display the “green leadership” mindset and engage the employee to offer solutions for energy conservation in the workplace (Young et al., 2015). Thirdly, the energy saving norms can be promoted by delivering training and seminars to harness the employee attitudes towards energy saving at the workplace. Fourthly, displaying the best practices with inspirational communication techniques can promote energy conservation in the workplace. Lastly, another way to encourage employee participation in energy conservation at the workplace is to develop facilitative policies that incentivize the employees to engage in workplace energy conservation behaviors. As we found that no significant variance exists between employees’ age, gender, education, and rank, it is clear that business management needs to develop policies and guidelines to promote energy conservation behaviors for all employees working in an organization.

We acknowledge that the current study has three limitations. First, our study focuses on energy conservation at the organizational level. Organizations differ based on their activities and operations; further exploration would help understand energy conservation behaviors among employees within production and services industries and in state-owned or privately owned organizations. Second, the data were collected in a self-reports manner at one time. Collecting longitudinal data and exploring employee effects associated with their organization would be interesting. Lastly, the current study only analyzed data from a Chinese sample. Future studies may incorporate samples from other countries and examine the effect of national culture on energy conservation behaviors.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NH, MA, AS, and MM—Conceptualization, methodology, survey instrument, writing—original draft. AM and NZ—Conceptualization, data analysis, writing—original draft, revise and improvement.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenrg.2022.940595/full#supplementary-material

References

Bamberg, S., Fujii, S., Friman, M., and Garling, T. (2011). Behaviour theory and soft transport policy measures. Transp. Policy 18, 228–235. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.08.006

Cain, M. K., Zhang, Z., and Yuan, K.-H. (2017). Univariate and multivariate skewness and kurtosis for measuring non-normality: Prevalence, influence, and estimation. Behav. Res. Methods 49 (5), 1716–1735. doi:10.3758/s13428-016-0814-1

CEC (2020). China electricity council. Available at: http://www.cec.org.cn/guihuayutongji/tongjxinxi/niandushuju/2020-01-21/197077.html (Accessed February 21, 2021).

Chen, C., F., and Knight, K. (2014). Energy at work: Social psychological factors affecting energy conservation intentions within Chinese electric power companies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 5, 23–31. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2014.08.004

Chen, K., and Deng, T. (2016). Research on the green purchase intentions from the perspective of product knowledge. Sustainability 8 (9), 943. doi:10.3390/su8090943

Chen, Z., and Liu, Y. (2020). The effects of leadership and reward policy on employees’ electricity saving behaviors: An empirical study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 2019. doi:10.3390/ijerph17062019

Choi, H., Jang, J., and Kandampully, J. (2015). Application of the extended VBN theory to understand consumers' decisions about green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 51, 87–95. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.08.004

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Oxfordshire, England, UK: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203771587

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., and Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39 (2), 175–191. doi:10.3758/bf03193146

Fornara, F., Molinario, E., Scopelliti, M., Bonnes, M., Bonaiuto, F., Cicero, L., et al. (2020). The extended value-belief-norm theory predicts committed action for nature and biodiversity in Europe. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev., 81: 106338. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2019.106338

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18 (1), 39–50. doi:10.2307/3151312

Gkargkavouzi, A., Halkos, G., and Matsiori, S. (2019). Environmental behavior in a private-sphere context: Integrating theories of planned behavior and value belief norm, self-identity and habit. Resour. Conservation Recycl. 148, 145–156. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.01.039

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., and Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31 (1), 2–24. doi:10.1108/ebr-11-2018-0203

Han, H., Hwang, J., and Lee, M. J. (2016). The value–belief–emotion–norm model: Investigating customers' eco-friendly behavior. J. Travel & Tour. Mark. 34 (5), 590–607. doi:10.1080/10548408.2016.1208790

Hirstsuka, J., Perlaviciute, G., and Steg, L. (2018). Testing VBN theory in Japan: Relationship between values, beliefs, norms and acceptability and expected effects of a car pricing policy. Transp. Res. Part F 53, 74–83.

Kim, H. J., Kim, J. Y., Oh, K. W., and Jung, H. J. (2016). Adoption of eco-friendly faux leather: Examining consumer attitude with the value–belief–norm framework. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 34 (4), 239–256. doi:10.1177/0887302x16656439

Kim, S., H., and Seock, Y., K. (2019). The roles of values and social norm on personal norms and pro-environmentally friendly apparel product purchasing behavior: The mediating role of personal norms. J. Retail. Consumer Serv. 15, 83–90. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.05.023

Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collaboration 11, 1–10. doi:10.4018/ijec.2015100101

Leygue, C., Ferguson, E., and Spence, A. (2017). Saving energy in the workplace: Why, and for whom? J. Environ. Psychol. 53, 50–62. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.06.006

Liu, X., Zou, Y., and Wu, J. (2018). Factors influencing public-sphere pro-environmental behavior among Mongolian college students: A test of value–belief–norm theory. Sustainability 10, 1384. doi:10.3390/su10051384

López-Mosquera, N., and Sánchez, M. (2012). Theory of Planned Behavior and the Value-Belief-Norm Theory explaining willingness to pay for a suburban park. J. Environ. Manag. 113, 251–262. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.08.029

Maichum, K., Parichatnon, S., and Peng, K. (2016). Application of the extended theory of planned behavior model to investigate purchase intention of green products among Thai consumers. Sustainability 8 (10), 1077. doi:10.3390/su8101077

NHS (2022). Greener NHS: Action taken. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/get-involved/ (accessed on August 10, 2022).

Podsakoff, P., M., Mackenzie, S., B., and Podsakoff, N., P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 63 (1), 539–569. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

van Riper, C. J., and Kyle, G., T. (2014). Understanding the internal processes of behavioural engagement in a national park: A latent variable path analysis of the value-belief-norm theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 38, 288–297.

Sánchez, M., López-Mosquera, N., and Lera-López, F. (2015). Improving pro-environmental behaviours in Spain. The role of attitudes and socio-demographic and political factors. J. Environ. Policy & Plan. 18 (1), 47–66. doi:10.1080/1523908x.2015.1046983

Stern, P. C. (2000). New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 56, 407–424. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00175

Ünal, A. B., Steg, L., and Granskaya, J. (2019). To support or not to support, that is the question. Testing the VBN theory in predicting support for car use reduction policies in Russia. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 119, 73–81. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2018.10.042

Walton, T., and Austin, D. (2011). Pro-environmental behavior in an urban social structural context. Sociol. Spectr. 31 (3), 260–287. doi:10.1080/02732173.2011.557037

Wensing, J., Carraresi, L., and Broring, S. (2019). Do pro-environmental values, beliefs and norms drive farmers' interest in novel practises fostering the bioeconomy? J. Environ. Manage. 232, 858–867. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.11.114

Wynveen, C. J., Wynveen, B. J., and Sutton, S. G. (2015). Applying the value-belief-norm theory to marine contexts: Implications for encouraging pro-environmental behavior. Coast. Manag. 43 (1), 84–103. doi:10.1080/08920753.2014.989149

Yildirim, B., C., and Semiz, G., K. (2019). Future teachers' sustainable water consumption behavior: A test of the value-belief-norm theory. Sustainability 11, 1558. doi:10.3390/su11061558

Young, W., Davis, M., McNeil, I., M., Malhotra, B., Russel, S., Unsworth, K., et al. (2015). Changing behaviour: Successful environmental programmes in the workplace. Bus. Strategy Environ. 24, 689–703. doi:10.1002/bse.1836

Zhang, L., Ruiz-Menjivar, J., Luo, B., Liang, Z., and Swisher, M., E. (2020). Predicting climate change mitigation and adaptation behaviors in agricultural production: A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the value-belief-norm theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 68, 101408. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101408

Keywords: value-belief-norm theory, workplace energy conservation, China, intention, bahavior

Citation: Al Mamun A, Hayat N, Mohiuddin M, Salameh AA, Ali MH and Zainol NR (2022) Modelling the significance of value-belief-norm theory in predicting workplace energy conservation behaviour. Front. Energy Res. 10:940595. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2022.940595

Received: 10 May 2022; Accepted: 12 August 2022;

Published: 05 September 2022.

Edited by:

Hasim Altan, Arkin University of Creative Arts and Design (ARUCAD), CyprusReviewed by:

Bheru Lal Salvi, Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology, IndiaSonya Sharififard, Pepperdine University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Al Mamun, Hayat, Mohiuddin, Salameh, Ali and Zainol. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abdullah Al Mamun, bWFtdW43NzkzQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==, YWxtYW11bkB1a20uZWR1Lm15

Abdullah Al Mamun

Abdullah Al Mamun Naeem Hayat

Naeem Hayat Muhammad Mohiuddin

Muhammad Mohiuddin Anas A. Salameh

Anas A. Salameh Mohd Helmi Ali

Mohd Helmi Ali Noor Raihani Zainol

Noor Raihani Zainol