- 1Institute of Economy and Finance, University of Szczecin, Szczecin, Poland

- 2Institute of Law, University of Szczecin, Szczecin, Poland

- 3Doctoral School, University of Szczecin, Szczecin, Poland

Sustainable development is an important element of the interests of modern economics. In order to function on the market and develop, companies must adhere to the principles of sustainable development. In this context, the interest of companies in the implementation and application of ESG strategies is growing. In the long-term perspective, the use of this type of strategy is to generate an increase in the company’s value. This value is of interest to the company’s stakeholders, who may use the information about the company’s value, e.g., in terms of its management or investment. The aim of the article is to examine the relationship between the company’s value and its fundamental strength. The analysis covers companies from the energy sector (listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange) that declare the use of ESG practices. The time range of the research covers the years 2013–2020. For the purpose of the study, selected statistical measures and the Fundamental Power Index (FPI) were used. This indicator synthetically evaluates all areas of the company’s operations. The results of the research show that the value of the company is not influenced by its fundamental strength. Therefore, the investors do not reduce the company’s value in the light of information on its fundamental strength. In addition, companies vary in terms of fundamental strength measured by FPI.

Introduction

One of the factors for the development of societies is the concentration of activities covering social, economic, and environmental aspects. However, the key element of development is to ensure that these activities are sustainable and respect the environment and rights. Due to the advancing climate change, governments and global corporations are increasingly focusing on environmental protection and social responsibility in their activities. Concentration on ESG factors is one of the strongest trends operating on a global scale. Central Banks and institutions regulating financial markets play a significant role in creating guidelines related to the sustainable development policy and ESG. In the area of the European Union, it is the European Central Bank and institutions: the European Banking Authority (EBA), the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) and the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA).

It is worth noting that in 2015 the United Nations adopted appropriate guidelines, expressed in 17 Goals of Sustainable Development (17 Goals of Sustainable Development, 2021). The European Parliament has also been adopting relevant resolutions (directives) for years, which, in addition to issues related to the sustainable development of societies, also include guidelines for the socially responsible operation of enterprises (European Parliament Resolution, 2013; European Parliament Resolution, 2021a; European Parliament Resolution, 2021b). The importance of sustainable and socially responsible development was also reflected in changes in the functioning of capital markets and stock exchanges (Waygood, 2014; Busch et al., 2015; ESG, 2021; Eurosif, 2021; Krzysztofik et al., 2021; Strengthening Capital Markets, 2021; World Investment Report, 2021) or the insurance market (Managing Environmental, 2021; PSI, 2021). When focusing on listed companies, it can be noticed that in their functioning there is some kind of transformation and adaptation to the principles of sustainable development. As a result, the interest of companies in the implementation and application of ESG strategies is growing. The consistency of companies’ operations with general trends in sustainable development is one issue. In the case of listed companies, it is worth noting that the company’s stakeholders, in addition to the tangible effects of companies’ operations, most often related to financial results, are also interested in non-measurable, non-financial factors (Gutsche and Ziegler, 2019). These include factors resulting from the ESG strategy and consist of environmental (E), social (S) and governance (G) effects. In turn, these effects are to be revealed over time. Therefore, the application of the ESG strategy has a long-term dimension. With regard to listed companies, the application of this type of strategy is also expected to generate an increase in the company’s value. This value is of interest to the company’s stakeholders, who may use the information about the company’s value, e.g., in terms of its management or investment. It is interesting how the measures of value for companies that have implemented ESG aspects are shaped and whether there is a relationship between the measures of value and fundamental strength. Thus, a hypothesis was made that there is a significant relationship between the fundamental strength and the company’s value.

The aim of this article is to analyze the relationship between the company’s value and its fundamental strength. The study was conducted for companies from the energy sector that declare the use of ESG practices. The time scope of the study covers the years 2013–2020. As regards the measures of value, the market value and rate of return as well as the fundamental strength of the companies were used. To achieve the aim of the study, selected statistical measures and the Fundamental Power Index (FPI) were used (Tarczyńska-Łuniewska, 2013a). This indicator measures the fundamental strength of a company. Fundamental strength can be defined as a summary assessment of the company in all areas of its operation. It is worth noting that this category is closely assigned to the fundamental analysis. The nature and definition of this concept result from the principles, methods and substantive aspects of the fundamental analysis. In order to achieve the aim of the study, a research hypothesis was formulated, which assumes the existence of a relationship between the fundamental strength and the company’s value. The existing research on the impact of ESG factors on the company’s results (Servaes and Tamayo, 2013; Plumlee et al., 2015; Kaspereit and Lopatta, 2016) does not exhaust this issue. The formulated aim of the article makes it possible to solve the problem of the lack of a uniform methodology for studying the influence of fundamental strength on the value of the company.

The approach proposed in the article is innovative because it relates to the issue of measurement of fundamental strength and the study of the relationship between the fundamental strength and the market value of the company, which was not the subject of previous research. In the first case, it is innovative to apply the Fundamental Power Index to the comprehensive assessment of companies. It is worth noting that the effects of the company’s operations are measurably reflected in its financial results. In the construction of the Fundamental Power Index, in the area of liquidity, profitability, operational efficiency and debt, most often economic and financial indicators are used, which in the classic approach of financial analysis constitute the basis for assessing the economic and financial condition of a company. By implementing the multidimensional approach and the concept of the Fundamental Power Index, the entity’s fundamental strength can be considered from the point of view of assessing the economic and financial condition of the entity. The proposed approach is new in terms of the comprehensive use of the Fundamental Power Index and exposes the idea of the company’s fundamental strength. In the second case, the approach proposed in the article also increases the objectivity and complexity of the assessment of the relationship between the fundamental strength and the market value by using the Fundamental Power Index and measures of the market value of companies in this respect.

The research conducted in this article fills the research gap in this area. Due to the specificity of the measures of value, which include the market value and fundamental strength, the conducted analyzes are consistent with current research trends. In addition, an important element is the focus on companies from a specific sector—the energy sector, that at the same time apply the ESG policy. It is worth noting that the energy sector is a strategic sector related to the energy security of each country. The generation and transmission of electricity determines the efficient functioning of the economy. The structure of the energy market includes the production and distribution of both renewable and non-renewable energy. Such a division is also important from the point of view of sustainable development. When it comes to environmental issues, the energy sector is usually assessed negatively as a sector that does not contribute to environmental protection with its activities. A conscious policy related to the promotion of environmental protection by companies from the energy sector is to change this assessment. Changes in the area of pro-ecological and pro-social aspects have forced energy companies to include these aspects in their activities (Szczepankiewicz and Mućko, 2016; Aguilera-Caracuel et al., 2017). Synthetically, these issues are included, for example, in (Latapí Agudelo et al., 2020). Narrowing the study to energy companies that apply the ESG strategy allows for addressing the issue of value in companies of this type and for using the information on the measures of value by the company’s stakeholders. But, it should be emphasized that, in general, the direction of research in the field of the energy market is very broad. It is worth paying attention to the current research regarding renewable energy and the search for its connections with financial development, interest rates, the real estate market or economic development (Abumunshar et al., 2020; Qashou et al., 2022; Samour et al., 2022; Samour and Pata, 2022).

An important issue in the ESG areas is also the legal liability related to information reporting. These issues are regulated by law. Due to the type of companies covered by the study, the article presents the legal aspects of ESG reporting in the energy sector.

The approach presented in the manuscript increases the usefulness of the fundamental analysis and enables the quantification of the company’s assessment using the FPI index. The results of the research may be useful for various groups of company stakeholders, including: stock investors, market analysts, and managers.

General Aspects of Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance and the Scope of Their Use

Methodological aspects of ESG factors can be found, for example, in (ter Horst et al., 2007), and ESG practices can be explained as (Gierałtowska, 2017; Henisz et al., 2019; Stefaniak, 2019; Corporate Governance Institute, 2021):

• E—the protection of the natural environment is related, inter alia, to the energy consumption, waste management, pollution control, animal research. Enterprises using ESG factors comply with legal regulations in this area;

• S—social factors are related to the internal relations of the enterprise, as well as its external relations. The first concerns decent working conditions, respect for human rights and compliance with work safety regulations. The second concerns the relationship between the company and its suppliers, recipients, or customers. In this respect, the overall impact of the company on society should also be taken into account;

• G—corporate governance refers to the structure of the company’s management board, respecting the rights of stakeholders, including disclosure obligations towards them. Furthermore, in terms of corporate governance, independence of decision-making and management skills should be taken into account.

In recent years, enterprises have been undergoing a process of adaptation to trends resulting from the assumptions of sustainable development adopted by the United Nations, the European Commission or capital markets (stock exchanges). Enterprises introduce changes to the strategic goals of their operation, taking into account the following factors: environmental (E), social (S) and corporate governance (G). The introduction of ESG factors may have many directions of impact on the enterprise. In addition, positive and negative information about the application (or non-application) of ESG practices may be of significant importance to various stakeholder groups. This information may influence the behavior of stakeholders towards the company: increase/decrease in investor interest, increase/decrease in the trust of customer/employee. An important element is also the opinion about the company and its reputation on the market. It is also worth noting that social responsibility has a wide range of impact and, apart from enterprises, may also occur in budgetary units (Buchta et al., 2018).

The active application of ESG practices is varied and may manifest itself in various areas of the company’s operation or external activities. This may be associated, inter alia, with:

• The influence of ESG factors on the company’s results (Shahbaz et al., 2020);

• Building the company’s value (Fatemi et al., 2018; Maury, 2022; di Tommaso and Thornton, 2020);

• The reduction in the cost of capital (Bassen et al., 2006; Harjoto and Jo, 2015);

• The effectiveness of investing in socially responsible companies, including building a portfolio as part of socially responsible investments (Feldman et al., 1997; Balcilar et al., 2017; Andersson et al., 2020; Harjoto et al., 2021; Janik and Bartkowiak, 2022);

• Greater innovation (García-Piqueres and García-Ramos, 2021; Ghanbarpour and Gustafsson, 2022);

• Image building and trust in the company (Luo et al., 2012; Loe and Kelman, 2016; Aguilera-Caracuel et al., 2017; Oh et al., 2017; Overton et al., 2021);

• Positive relations with the company’s stakeholders (internal and external) (Bolton et al., 2011; Jonek-Kowalska, 2018);

• The reduction of resource consumption (Yin et al., 2021);

• The problem of reporting information from the EGS area (Szczepankiewicz and Mućko, 2016).

The use of ESG aspects by companies is also important from the point of view of risk assessment. This may translate into the assessment of risks of its functioning and of risk management in the enterprise in the case of additional consideration of the risks related to the environmental or social impact (Ślęzak-Gładzik, 2013; Chollet and Sandwidi, 2018; Champagne et al., 2021). In this context, responsible management, observation and taking into account the direction of management activities in order to protect the company against future threats are also important (Lemke and Petersen, 2013; Mazur, 2015).

It is also worth emphasizing that the approach taking into account the acceptance and use of ESG factors was reflected in shaping investment decisions and the emergence of certain investment trends (van Duuren et al., 2016; Report on US Sustainable and Impact Investing Trends, 2020). Research on the impact of non-financial factors, including ESG, on investment decisions shows that these factors are an important point of reference. This is related not only to the performance of investment activities, including portfolio investments (Kempf and Osthoff, 2007; Pástor et al., 2021), but also to the impact on stakeholder reactions (Yu and Luu, 2021).

The implementation of ESG aspects in the operating policies of enterprises is a key element of their development and adopted long-term goals. The case of listed companies results from the strategies adopted in ESG practices on stock exchanges.

Legal Aspects of Reporting Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance Factors by Energy Market Entities

For the subjective aspects of the energy market, especially in the aspect of the activities of commercial law companies issuing securities and operating on this market, the legal framework in the area of the application of ESG standards by these entities as valuable information about their actual condition and impact on the environment is of fundamental importance (Bouten et al., 2011). Since 2017, the European Commission has published significant guidance documents for reporting non-financial information, including climate-related information. In the opinion of the European Commission, these guidelines were intended to help commercial law companies to disclose, in a consistent and comparable manner, essential non-financial information, including information relating to the social and environmental aspects of their operations (Izzo et al., 2020). Their essence was to ensure the standardization of published information, which was not only to increase the transparency and usefulness of the disclosed data, but above all to encourage commercial law companies to use instruments of sustainable development. The guidelines are not legally binding, as they do not extend legal obligations or introduce administrative instruments applied to commercial law companies by public administration bodies. Nevertheless, they constitute an important practical supplement to the existing Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups (Directive 2014/95/EU, 2014).

In the Polish legal system, this Directive was implemented by the amendment to the Accounting Act of 29 September 1994 (Journal of Laws, 2021). According to the provisions of Regulation (EU) No 537/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on specific requirements regarding statutory audit of public-interest entities and repealing Commission Decision 2005/909/EC (Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, 2014), reporting obligations generally apply to the so-called public interest entities, which—in the case of participants of energy market—are capital companies, limited joint-stock partnership, general partnerships or limited partnerships, whose all partners bearing unlimited liability are capital companies, limited joint-stock partnerships or companies from other countries with similar legal form. An additional premise for imposing the obligation to report non-financial information is that these entities employ more than 500 employees and meet one of two financial conditions: 85 million PLN in total assets in the balance sheet at the end of the financial year or 170 million PLN of net revenues from the sale of goods and products for the financial year. Pursuant to Art. 49b of the Accounting Act, corporate statements should contain descriptions of the policies applied by the companies in relation to social issues, employee matters, the natural environment, respect for human rights and counteracting corruption.

In making the statement, the entity provides information to the extent necessary to evaluate its development, performance, and situation, applying any principles, including internal, national, and international guidelines with reference to their source. Moreover, if an entity does not apply a policy in relation to some area of corporate social responsibility, then it is required to state in the statement the reasons for not applying it (Cebrowska and Kiziukiewicz, 2021). The non-financial information is presented in the form of a statement that is a separate part of the management report or is prepared as a separate report on non-financial information that the entity publishes on its website within 6 months from the balance sheet date. It is worth noting that the act allows for situations in which non-financial information may be omitted in the statement. This may occur when the matters that are the subject of disclosure are being negotiated and, in the opinion of management and members of the supervisory board or other governing body, disclosure of this information at a given stage could be detrimental to the entity’s market position. However, all omissions used should be mentioned in the declaration.

The experience of recent years shows that the European Union aims to reorient the activities of entrepreneurs, including energy market entities, towards the implementation of the idea of sustainable development, including the creation of the so-called green investments (Chen et al., 2021). A manifestation of these activities is the proposal for Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) presented by the European Commission (European Commission, 2013). This Directive will replace the current Directive 2014/95/EU. The CSRD project was announced as part of a comprehensive package of legislative changes for sustainable financing of economic growth, aimed at achieving climate neutrality by the EU by 2050.

The proposal of Directive provides for the introduction of an obligation to report ESG matters in relation to a much wider catalogue of entities. According to the proposed Art. 19a paragraph 1, large undertakings and, as of 1 January 2026, small and medium-sized undertakings include in the management report information necessary to understand the undertaking’s impacts on sustainability matters, and information necessary to understand how sustainability matters affect the undertaking’s development, performance, and position. A large undertaking is defined as meeting two out of three of the following criteria: 1) 40 million Euro in net turnover, 2) 20 million Euro on the balance sheet, and 3) 250 or more employees. The small or medium undertaking under the CSRD would be one that meets two out of the three following criteria: 1) a balance sheet of between of 4 million Euro and 20 million Euro; and/or net turnover of between of 8 million Euro and 40 million Euro; and/or between 50 and 250 employees. Undertakings that are not established in the EU but have securities on EU-regulated markets are also in scope. The Directive introduces a few subjective exceptions which exempt from the above obligation.

The information that is subject to the reporting obligation relates to the future and the past, as well as is of a qualitative and quantitative nature. The objectives of the proposal include: 1) requiring reported information to be consistent with the EU regulations, including the EU taxonomy, comparable, reliable, and easy for users to find and make use of with digital technologies; 2) aiming to reduce unnecessary costs and enable companies to meet the growing demand for sustainability reporting in a cost-efficient manner (Wollmert and Hobbs, 2021). What is especially important, the CSRD proposal applies double materiality. Double materiality means that businesses must not only disclose how sustainability issues can affect the company (“impacts inward”), but also how the company impacts society and the environment (“impacts outward”). For businesses that have historically assessed only risks to their business rather than their impacts on the world, the CSRD implies a fundamental shift in measurement and reporting (Bancilhon, 2021).

At the same time, in order to deepen the standardization and ensure the comparability of the submitted information, the proposed Art. 19b of the Directive introduces an additional competence of the European Commission. The Commission is to adopt further normative acts to ensure sustainability reporting standards. In these standards, it is to specify in detail the information that undertakings are to report and, if applicable, define the structure of the reports. In this regard, it should be emphasized that the ESG reporting landscape is still developing, which means that the design of your ESG reporting framework should be based on agile design principles (Otto-Mentz et al., 2021). Of crucial interest to companies will be how the EU’s own standards line up—or do not—with other approaches already in existence or being developed. Issuers have begun to widely use the standards and frameworks created by SASB, GRI and TFCD, as well as other groups (Human, 2021). Due to the limited scope of this study, detailed issues related to this matter will be omitted.

The entirety of the proposed regulations, both in terms of the content and the form and manner of making the indicated information public, is intended to provide valuable information that will not only be available and comparable to information from other entities but will also contain complete and true data on the entity’s activities in the area of the environment, social aspects and shaping proper corporate governance. Sustainability reports should consist of objective information allowing stakeholders to make reliable evaluations of the organization’s non-financial performance, including (but not limited to) social and environmental aspects (Gray, 2006). At the same time, reporting on sustainability performance could potentially provide numerous benefits for a company including: increased credibility, reduced legal risks, improved supplier relationships, increased access to capital and increased ethical behavior along the supply chain (Paun, 2018). Forced by legal standards, properly implemented information function is of key importance for shaping the energy market, primarily by reorienting investment and financing resources to those projects that meet high ESG standards (Opferkuch et al., 2021). The current practice shows that partial and imprecise legal solutions relating to the obligation to disclose information in the ESG area do not fulfil this function properly.

Materials and Methods

The research was based on data from:

• Warsaw Stock Exchange (WSE)—including: market value and share price, which was the basis for determining the weekly rolled over rates of return;

• Notoria Serwis—data from financial statements concerning financial indicators.

The following measures of the value of companies were adopted: market value, rate of return and fundamental strength. The Fundamental Power Index (FPI) was used to measure the fundamental strength of companies. A dynamic approach was used in the construction of this index. Financial indicators for the analyzed enterprises were used to estimate FPI. The method of determining the FPI is presented later in the article.

Selected methods of examining statistical regularities in the field of the analysis of structure and interdependence were used in the analyzes. The applied methods of the correctness of the structure allowed to characterize the studied group of companies in terms of the examined variables. In this way, it was possible to address the similarities/differences between the companies. Through the prism of the level of measures for companies, it was also possible to assess the energy sector on the Warsaw Stock Exchange. Additionally, the comparison of the measures of the structure over time made it possible to identify trends in the changes of variables. The measures used included: arithmetic mean, standard deviation (S(x)), coefficient of random variation (Vs), quartile deviation (Q), coefficient of quartile variation (VQ).

Pearson correlation coefficients were used to verify the relationship between the fundamental strength and the value of the company.

The study was conducted for companies from the WSE energy sector that declared that they apply ESG aspects. The research was carried out in the years 2013–2020.

Fundamental Power Index

The Fundamental Power Index (FPI) was used to measure the company’s fundamental strength. This indicator is a measure of the fundamental strength. Fundamental strength expresses the summary effect of the company’s operation in all areas of its business. This applies to both external and internal elements of the company, as well as quantitative (measurable, e.g., financial results) and qualitative (non-measurable, e.g., market position) elements. The foundations of the fundamental strength are to be found in fundamental analysis. The concept of fundamental strength is a complex and directly immeasurable category. However, with the use of a multi-dimensional approach, it can be expressed with a single measure. It should be noted that Graham et al. (1934) was the precursor of the category of fundamental strength, and the multi-dimensional measurement was made by Tarczyński (1994). The fundamental strength methodology and measurement methodology in the form of the Fundamental Power Index (FPI) was developed by Tarczyńska-Łuniewska and is described in the monograph: Methodology for assessing the fundamental strength of (listed and non-listed) companies (Tarczyńska-Łuniewska, 2013b).

For the purposes of the study, the following approach to consider the fundamental strength through the prism of the economic and financial condition of the company was used to measure the fundamental strength of companies (Tarczyński et al., 2020):

where, i = 1, 2,.…, k.

The measure proposed in the article (FPIi = TMAIi) belongs to the group of multidimensional comparative analysis measures used to study complex directly immeasurable phenomena that characterize specific objects subject to analysis. In the case of the proposed approach, the fundamental strength is directly immeasurable, while the analyzed objects are the companies from the energy sector. As a consequence, the measurement of fundamental strength takes place by aggregating the variables (fundamental strength factors), which, in the case of this study, are financial indicators (xij) that allow the assessment of the economic and financial condition of companies. A full discussion on the methodology for determining the FPI and linking economic and financial indicators with the fundamental strength is presented, among others, in Tarczyński (1994) and Tarczyńska-Łuniewska (2013b).

TMAIi formula is as follow:

where, TMAIi—synthetic development measure for the i-th object, di—distance between the i-th object and the model object defined with the formula:

n—number of objects, (companies), k—number of variables, (financial and economic indicators), d0—norm which assures that TMAIi values belong to the interval from 0 to 1:

According to the Eq. 2 and given that di > 0, we may find the marginal value for the constant:

where, dimax—is the maximum di value,

In this method, the system of standardization of the data was used to assure its comparability: the 0–1 standardization. zij is calculated with the use of the following formula:

where, xij–values of the j-th variable (financial indicator) for the i-th object (company),

The FPIi = TMAIi is standardized and reaches values ranging from 0 to 1. The closer to 1, the better the object in terms of the general criterion. In the article this means a higher level of fundamental strength.

The Fundamental Power Index was determined by using as variables selected financial and economic ratios such as:

Profitability ratios: rate of assets (ROA), rate of equity (ROE);

Liability ratio: Current ratio (CR);

Efficiency ratios: Liabilities rotation in days (LR), Receivables rotation in days (RR), Assets turnover (AT);

Debt ratio: Debt Margin (DM).

When determining the Fundamental Power Index dynamic approach was used. It means that this index was estimated for variables weighted in time. The first study period had the lowest weight and the last period the highest. The study was conducted for the period of 3 years; hence the sequence of periods will be: i = 1, 2, 3. Consequently the weights (wi) were determined as follows:

where, wi—weight for the i-th period of the study, ni—number of the i-th period of the examination.

It is worth noting that the Fundamental Power Index was created on the basis of a synthetic measure of development (Hellwig, 1968). The context of using synthetic measures of development is wide (Nermend, 2009; Kompa and Witkowska, 2015; Skoczylas and Batóg, 2017; Kubiczek and Bieleń, 2021; Kądziołka, 2021), but their construction requires the adoption of methodological foundations of the phenomenon under study.

Results

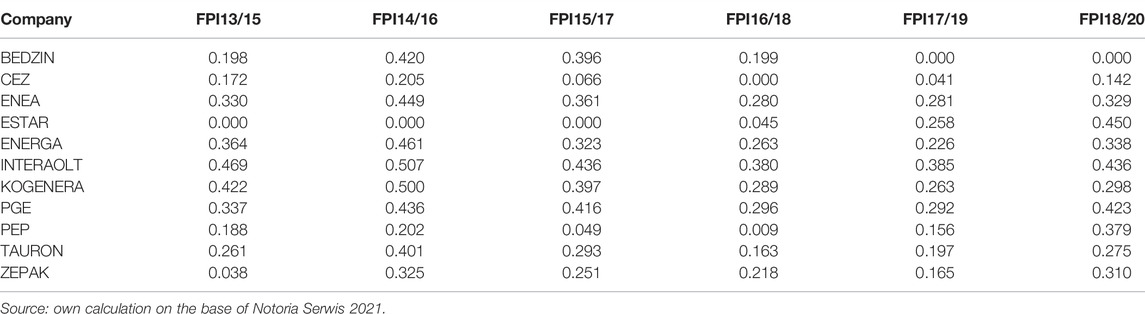

Table 1 presents the estimated levels of dynamic fundamental strength indicators (FPI) estimated for companies in the energy sector in the analyzed period.

The level of Fundamental Power Indices estimated for the analyzed companies from the energy sector (Table 1) for all periods of the analysis should be assessed as low. This conclusion is confirmed by the adopted methodology of FPI determination and its normative range <0; 1>. The level of the indicator can be assessed in relation to its intensity. The closer the index value is to 1, the higher the fundamental strength of the entity is. The closer the index value is to 0, the lower the fundamental strength of the examined entity is. In the general interpretation of the indicator, it is assumed that a company may have high fundamental strength, at an average (moderate) level, low, or may not have it at all. With regard to the examined companies, in the first period of the study for the years 2013–2015 (FPI 13/15) only INTERAOLT and KOGENERA companies can be assessed as having moderate fundamental strength. The indicators for these companies are 0.469 and 0.422, respectively. It should be noted that in the article, fundamental strength is considered through the prism of the economic and financial condition. Hence, the level of FPIs may be a warning signal for the company’s managers to focus their activities on increasing the effectiveness of the company’s operations and thus improving its financial results. On the other hand, the ZEPAK and ESTAR companies do not have any fundamental strength (FPI in 2013/2015 amounted to 0.038 and 0.000 respectively). In the case of ZEPAK and ESTAR, their economic and financial condition should be assessed negatively. It is a strong signal for the managers of these companies to focus their activities on improving the efficiency of their operation. In subsequent periods of the study, the INTERAOLT company rather maintains its fundamental strength at a relatively moderate level (FPI14/16 = 0.507, FPI15/17 = 0.436, FPI18/20 = 0.436). The KOGENERA company achieved an average level of fundamental strength in the period of 2014–2016. In the remaining years, the level of FPI decreased. Overall, in 2014–2016, six companies achieved a relatively moderate level of the indicator (FPI14/16). These were BEDZIN, ENERGA, INTERAOLT, KOGENERA, PGE, TAURON. In 2016–2018 and 2017–2019, none of the companies achieved at least a moderate level of fundamental strength. In 2018–2020 (FPI18/20), only ESTAR, INTERAOLT and PGE companies can be assessed as companies with a moderate level of fundamental strength. When analyzing the entire period of the study, it is worth noting that none of the companies maintained at least a moderate level of fundamental strength.

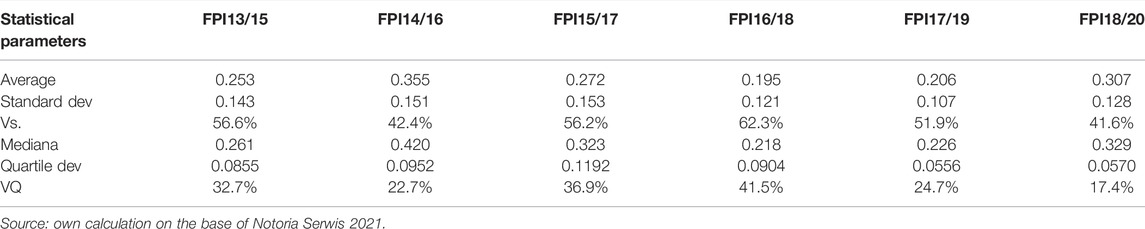

Table 2 presents statistical measures in the area of descriptive statistics for the estimated indicators of fundamental strength.

When analyzing the data in Table 2, it is possible to observe that energy companies are characterized by a fairly weak fundamental strength. This is confirmed by the average levels of the Fundamental Power Indices obtained in the analyzed period. Low levels of average values were obtained for both classical measures (arithmetic mean) and positional measures (median). Classical and positional measures of random variability (Vs and VQ) indicate high variability of the analyzed FPIs. The Vs and VQ coefficients significantly exceed the range (0–10%), i.e., good variability in the statistical sense. This means that the examined companies are highly diversified in terms of the fundamental strength measured by FPI. This situation indicates disproportions in the fundamental power of the examined companies.

It should be noted that the FPIs were estimated on the basis of the financial results of the examined companies. Therefore, it can be concluded that the financial results of the companies and the financial ratios determined on this basis are not favorable. Overall, they can be described as weak during the period considered. For investors, this situation is rather not optimistic in the context of the long-term attractiveness of the examined companies. In the light of the obtained results, it can be concluded that the fundamental strength of energy companies, measured through the prism of their economic and financial condition, is weak. This is confirmed by the levels of statistical measures for FPI indicators of the examined companies.

Table 3 shows the coefficients of correlation between the selected measures of value (market value and rate of return) and the fundamental strength of companies measured by FPI.

TABLE 3. Coefficients of correlation between value measures and the fundamental strength of companies from the WSE energy sector in 2013–2020.

The research results presented in Table 3 show that the Pearson correlation coefficients for the studied dependencies are low. It can be said that the fundamental strength of companies and the selected measures of the company’s value are independent of each other. Moreover, in most cases the coeFundamental Power IndexFundamental Power Indexfficients are negative. This suggests a direction opposite to the expected direction of the studied relations. However, it is important for the calculated coefficients of correlation to be statistically significant. Unfortunately, in the case of the analyzed relations, this does not happen. The significance test results were negative, which does not confirm a statistically significant relationship between the selected measures of value and the fundamental strength.

Conclusion

Most of the studies on the impact of ESG aspects on the financial results of companies, including the value of companies, confirm a positive correlation (Plumlee et al., 2015; Fatemi et al., 2018). It is worth mentioning that the research conducted so far on the correlation of fundamental strength and measures of value for the stock market in Poland (Tarczyński et al., 2020) indicated the existence of a moderate but significant correlation. These studies allowed for the conclusion that the market is guided by information about the fundamental strength of companies and discounts this information in measures of the company’s value. Other studies, also of the Polish market (Witkowska and Kuźnik, 2019), indicated a moderate relationship between the fundamental strength and the value of companies, but this relationship was not statistically significant. In the light of the research conducted for the energy sector on the Warsaw Stock Exchange, the hypothesis regarding the existence of a significant relationship between the company’s value and its fundamental strength has not been confirmed.

The reasons for this may be: a small number of companies from the energy sector on the main market of the Warsaw Stock Exchange in the analyzed period, the unstable capital market and the energy market in Poland. The trends of changes in the energy market in Poland should also be taken into account. This concerned, inter alia, issues of legal regulations of the energy market, including works for the liberalization of the electricity market in Poland (Energy Regulatory Office, 2021; Fodrowska, 2021). This situation had an impact on the stock exchange investors who took a waiting position. It is also worth emphasizing that the insufficient number of companies makes it difficult to observe global statistical regularities in the scope of the studied variables.

With regard to the financial results of the examined companies from the energy sector, it should be stated that these results were low. The examined companies were characterized by relatively poor financial results. As a consequence, it was to be expected that the estimated indicators of fundamental strength would also remain at a low level. The fundamental strength of the energy sector companies on the Warsaw Stock Exchange in the analyzed period was below the average minimum (0.5). Taking into account that the norm of the FPIs is in the range <0; 1>, such low levels of indicators for companies are not optimistic and testify to their weak fundamental strength. Moreover, the FPIs between the companies show large differences (Table 1, 2). This is visible in the levels of classical (Vs) and positional (VQ) dispersion measures. Generally, such a situation is not favorable. It does not prove the stability of the analyzed companies in terms of fundamental strength and gives a signal towards the instability of the effectiveness of their functioning on the market. For investors, such information is also not positive and may have a negative impact on the assessment of companies. As a consequence, it may lead to postponement in the process of investing in such companies.

The research results are consistent with other research approaches of this type for the Polish market and do not confirm the existence of a significant relationship between the measures of value and the fundamental strength of companies. As the energy sector in the main market of WSE is currently represented by a small number of companies, the study should be repeated in the future. It is also possible to consider extending the study with other measures of value or taking into account a longer, but maximum 5-year period of stability of the Fundamental Power Indices (which results from the foundations of the fundamental analysis). It is also worth note that data can have essential influence on the analysis process and results of the study. The limitations of the analyzes are mainly related to the availability of up-to-date financial data and their comparability. In particular, this applies to research conducted on a global scale for various capital markets or companies from different markets (countries). It should be emphasized that the quality of data, including their comparability, is important for determining the fundamental strength index.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

MT-L: Concept, data curation, software, and empirical analysis; KF-G: Writing draft, editing, methods, software, and analysis; MA: literature review, supervision, editing, and review.

Funding

The research was financed within the framework of the program of the Minister of Science and Higher Education under the name “Regional Excellence Initiative” in the years 2019–2022, project number 001/RID/2018/19, the amount of financing PLN 10,684,000.00.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

17 Goals of Sustainable Development (2021). 17 Goals of Sustainable Development. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (Accessed December 22, 2021).

Abumunshar, M., Aga, M., and Samour, A. (2020). Oil Price, Energy Consumption, and CO2 Emissions in Turkey. New Evidence from a Bootstrap ARDL Test. Energies 13, 5588. doi:10.3390/en13215588

Aguilera-Caracuel, J., Guerrero-Villegas, J., and García-Sánchez, E. (2017). Reputation of Multinational Companies. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 26, 329–346. doi:10.1108/EJMBE-10-2017-019

Andersson, E., Hoque, M., Rahman, M. L., Uddin, G. S., and Jayasekera, R. (2020). ESG Investment: What Do We Learn from its Interaction with Stock, Currency and Commodity Markets? Int. J. Fin. Econ. doi:10.1002/ijfe.2341

Balcilar, M., Demirer, R., and Gupta, R. (2017). Do Sustainable Stocks Offer Diversification Benefits for Conventional Portfolios? an Empirical Analysis of Risk Spillovers and Dynamic Correlations. Sustainability 9, 1799. doi:10.3390/su9101799

Bancilhon, C. (2021). What Business Needs to Know about the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive | Blog | BSR. Available at: https://www.bsr.org/en/our-insights/blog-view/what-business-needs-to-know-about-the-eu-corporate-sustainability-reporting (Accessed November 12, 2021).

Bassen, A., Meyer, K., and Schlange, J. (2006). The Influence of Corporate Responsibility on the Cost of Capital an Empirical Analysis. Hamburg, Germany: Mimeo, University of Hamburg. Retrieved.

Bolton, S. C., Kim, R. C.-h., and O’Gorman, K. D. (2011). Corporate Social Responsibility as a Dynamic Internal Organizational Process: A Case Study. J. Bus. Ethics 101, 61–74. doi:10.1007/s10551-010-0709-5

Bouten, L., Everaert, P., van Liedekerke, L., de Moor, L., and Christiaens, J. (2011). Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting: A Comprehensive Picture? Account. Forum 35, 187–204. doi:10.1016/J.ACCFOR.2011.06.007

Buchta, K., Jakubiak, M., Skiert, M., and Wilczewski, A. (2018). University's Social Responsibility - Labor Market Perspective. Folia Oeconomica Stetin. 18, 46–58. doi:10.2478/foli-2018-0018

Busch, T., Bauer, R., and Orlitzky, M. (2015). Sustainable Development and Financial Markets. Bus. Soc. 55, 303–329. doi:10.1177/0007650315570701

Cebrowska, T. (2021). “Komentarz Do Art. 49b Ustawy O Rachunkowości,” in Ustawa O Rachunkowości. Komentarz. Editor T. Kiziukiewicz (Warsaw: Lex).

Champagne, C., Coggins, F., and Sodjahin, A. (2021). Can Extra-financial Ratings Serve as an Indicator of ESG Risk? Glob. Finance J. 2021, 100638. doi:10.1016/J.GFJ.2021.100638

Chen, Y., Jermias, J., and Nazari, J. A. (2021). The Effects of Reporting Frameworks and a Company's Financial Position on Managers' Willingness to Invest in Corporate Social Responsibility Projects. Acc. Finance 61, 3385–3425. doi:10.1111/acfi.12706

Chollet, P., and Sandwidi, B. W. (2018). CSR Engagement and Financial Risk: A Virtuous Circle? International Evidence. Glob. Finance J. 38, 65–81. doi:10.1016/J.GFJ.2018.03.004

Corporate Governance Institute (2021). Corporate Governance Institute. Available at: http://thecorporategovernanceinstitute.com (Accessed December 28, 2021).

di Tommaso, C., and Thornton, J. (2020). Do ESG Scores Effect Bank Risk Taking and Value? Evidence from European Banks. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 27, 2286–2298. doi:10.1002/csr.1964

Directive 2014/95/EU (2014). Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 Amending Directive 2013/34/EU as Regards Disclosure of Non-financial and Diversity Information by Certain Large Undertakings and Groups. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32014L0095 (Accessed November 12, 2021).

Energy Regulatory Office (2021). Energy Regulatory Office. Available at: https://www.ure.gov.pl/en (Accessed December 29, 2021).

ESG (2021). ESG - Together for Sustainable Development. Available at: https://www.gpw.pl/esg-gpw (Accessed November 21, 2021).

European Commission (2013). Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council Amending Directive 2013/34/EU, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, as Regards Corporate Sustainability Reporting. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021PC0189 (Accessed December 8, 2021).

European Parliament Resolution (2021). European Parliament Resolution of 10 March 2021 with Recommendations to the Commission on Corporate Due Diligence and Corporate Accountability. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2021-0073_EN.html (Accessed December 21, 2021).

European Parliament Resolution (2013). European Parliament Resolution of 6 February 2013 on Corporate Social Responsibility: Accountable, Transparent and Responsible Business Behaviour and Sustainable Growth. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-7-2013-0049_EN.html (Accessed December 22, 2021).

European Parliament Resolution (2021). European Parliament Resolution on Corporate Social Responsibility. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/B-8-2018-0152_EN.html (Accessed December 23, 2021).

Eurosif (2021). Eurosif. Available at: https://www.eurosif.org/(Accessed December 23, 2021).

Fatemi, A., Glaum, M., and Kaiser, S. (2018). ESG Performance and Firm Value: The Moderating Role of Disclosure. Glob. Finance J. 38, 45–64. doi:10.1016/J.GFJ.2017.03.001

Feldman, S. J., Soyka, P. A., and Ameer, P. G. (1997). Does Improving a Firm's Environmental Management System and Environmental Performance Result in a Higher Stock Price? J. Invest. Winter 6, 87–97. doi:10.3905/joi.1997.87

Fodrowska, K. (2021). Liberalizacja Rynku Energii – Historia I Przebieg. Available at: https://enerad.pl/aktualnosci/liberalizacja-rynku-energii-historia-i-przebieg/(Accessed December 30, 2021).

García-Piqueres, G., and García-Ramos, R. (2021). Complementarity between CSR Dimensions and Innovation: Behaviour, Objective or Both? Eur. Manag. J. doi:10.1016/J.EMJ.2021.07.010

Ghanbarpour, T., and Gustafsson, A. (2022). How Do Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Innovativeness Increase Financial Gains? A Customer Perspective Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 140, 471–481. doi:10.1016/J.JBUSRES.2021.11.016

Gierałtowska, U. (2017). Inwestowanie Odpowiedzialne Społecznie – Nowy Trend Na Rynku Kapitałowym. Finanse, Rynki Finans. Ubezpieczenia 6, 23–36.

Graham, B., Dodd, D. L. F., and Cottle, S. (1934). Security Analysis. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Gray, R. (2006). Social, Environmental and Sustainability Reporting and Organisational Value Creation? Account. Auditing Account. J. 19, 793–819. doi:10.1108/09513570610709872

Gutsche, G., and Ziegler, A. (2019). Which Private Investors Are Willing to Pay for Sustainable Investments? Empirical Evidence from Stated Choice Experiments. J. Bank. Finance 102, 193–214. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2019.03.007

Harjoto, M. A., Hoepner, A. G. F., and Li, Q. (2021). Corporate Social Irresponsibility and Portfolio Performance: A Cross-National Study. J. Int. Financial Mark. Institutions Money 70, 101274. doi:10.1016/J.INTFIN.2020.101274

Harjoto, M. A., and Jo, H. (2015). Legal vs. Normative CSR: Differential Impact on Analyst Dispersion, Stock Return Volatility, Cost of Capital, and Firm Value. J. Bus. Ethics 128, 1–20. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2082-2

Hellwig, Z. (1968). Zastosowanie Metody Taksonomicznej Do Typologicznego Podziału Krajów Ze Względu Na Ich Poziom Rozwoju Oraz Zasoby I Strukturę Wykwalifikowanych Kadr. Przegląd Stat. 4, 306–327.

Henisz, W., Koller, T., and Nuttall, R. (2019). Five Ways that ESG Creates Value. Seattle, Washington: McKinsey Quarterly.

Human, T. (2021). Profiling the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive | IR Magazine. Available at: https://www.irmagazine.com/regulation/profiling-corporate-sustainability-reporting-directive (Accessed November 8, 2021).

Izzo, M. F., Ciaburri, M., and Tiscini, R. (2020). The Challenge of Sustainable Development Goal Reporting: The First Evidence from Italian Listed Companies. Sustainability 12, 3494. doi:10.3390/su12083494

Janik, B., and Bartkowiak, M. (2022). Are Sustainable Investments Profitable for Investors in Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs)? Finance Res. Lett. 44, 102102. doi:10.1016/J.FRL.2021.102102

Jonek-Kowalska, I. (2018). How Do Turbulent Sectoral Conditions Sector Influence the Value of Coal Mining Enterprises? Perspectives from the Central-Eastern Europe Coal Mining Industry. Resour. Policy 55, 103–112. doi:10.1016/J.RESOURPOL.2017.11.003

Kądziołka, K. (2021). Ranking and Classification of Cryptocurrency Exchanges Using the Methods of a Multidimensional Comparative Analysis. Folia Oeconomica Stetin. 21, 38–56. doi:10.2478/foli-2021-0015

Kaspereit, T., and Lopatta, K. (2016). The Value Relevance of SAM's Corporate Sustainability Ranking and GRI Sustainability Reporting in the European Stock Markets. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 25, 1–24. doi:10.1111/beer.12079

Kempf, A., and Osthoff, P. (2007). The Effect of Socially Responsible Investing on Portfolio Performance. Eur. Financ. Manag. 13, 908–922. doi:10.1111/j.1468-036X.2007.00402.x

Kompa, K., and Witkowska, D. (2015). Synthetic Measures of the European Capital Markets Development. Ekonometria 4, 214–228. doi:10.15611/ekt.2015.4.14

Krzysztofik, M., Fleury, M., During, N., and Scheepens, W. (2021). ESG Reporting Guidelines. Available at: https://www.gpw.pl/pub/GPW/ESG/ESG_Reporting_Guidelines.pdf (Accessed November 21, 2021).

Kubiczek, J., and Bieleń, M. (2021). The Level of Socio-Economic Development of Regions in Poland. Wiadomości Statystyczne. Pol. Statistician 66, 27–47. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0015.5130

Latapí Agudelo, M. A., Johannsdottir, L., and Davidsdottir, B. (2020). Drivers that Motivate Energy Companies to Be Responsible. A Systematic Literature Review of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Energy Sector. J. Clean. Prod. 247, 119094. doi:10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2019.119094

Lemke, F., and Petersen, H. L. (2013). Teaching Reputational Risk Management in the Supply Chain. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 18, 413–429. doi:10.1108/SCM-06-2012-0222

Loe, J. S. P., and Kelman, I. (2016). Arctic Petroleum's Community Impacts: Local Perceptions from Hammerfest, Norway. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 16, 25–34. doi:10.1016/J.ERSS.2016.03.008

Luo, J., Meier, S., and Oberholzer-Gee, F. (2012). No News Is Good News: CSR Strategy and Newspaper Coverage of Negative Firm Events. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School.

Managing Environmental (2021). Managing Environmental, Social and Governance Risks in Non-life Insurance Business. Available at: https://www.unepfi.org/psi/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/PSI-ESG-guide-for-non-life-insurance.pdf (Accessed December 23, 2021).

Maury, B. (2022). Strategic CSR and Firm Performance: The Role of Prospector and Growth Strategies. J. Econ. Bus. 118, 106031. doi:10.1016/J.JECONBUS.2021.106031

Mazur, B. (2015). Corporate Social Responsibility in Poland: Businesses' Self-Presentations. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 213, 593–598. doi:10.1016/J.SBSPRO.2015.11.455

Nermend, K. (2009). Vector Calculus in Regional Development Analysis. Berlin, Germany: Springer. Vol. 53.

Oh, H., Bae, J., and Kim, S.-J. (2017). Can Sinful Firms Benefit from Advertising Their CSR Efforts? Adverse Effect of Advertising Sinful Firms' CSR Engagements on Firm Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 143, 643–663. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3072-3

Opferkuch, K., Caeiro, S., Salomone, R., and Ramos, T. B. (2021). Circular Economy in Corporate Sustainability Reporting: A Review of Organisational Approaches. Bus. Strat. Env. 30, 4015–4036. doi:10.1002/bse.2854

Otto-Mentz, V., Albers, B., and Hindriks, H. (2021). New EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive | Deloitte Netherlands. Available at: https://www2.deloitte.com/nl/nl/pages/risk/articles/new-eu-corporate-sustainability-reporting-directive.html (Accessed November 8, 2021).

Overton, H., Kim, J. K., Zhang, N., and Huang, S. (2021). Examining Consumer Attitudes toward CSR and CSA Messages. Public Relat. Rev. 47, 102095. doi:10.1016/J.PUBREV.2021.102095

Pástor, Ľ., Stambaugh, R. F., and Taylor, L. A. (2021). Sustainable Investing in Equilibrium. J. Financial Econ. 142, 550–571. doi:10.1016/J.JFINECO.2020.12.011

Paun, D. (2018). Corporate Sustainability Reporting: An Innovative Tool for the Greater Good of All. Bus. Horizons 61, 925–935. doi:10.1016/J.BUSHOR.2018.07.012

Plumlee, M., Brown, D., Hayes, R. M., and Marshall, R. S. (2015). Voluntary Environmental Disclosure Quality and Firm Value: Further Evidence. J. Account. Public Policy 34, 336–361. doi:10.1016/J.JACCPUBPOL.2015.04.004

PSI (2021). PSI Priciples for Sustainable Insurance. Available at: https://www.unepfi.org/psi/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/PSI-document1.pdf (Accessed December 23, 2021).

Qashou, Y., Samour, A., and Abumunshar, M. (2022). Does the Real Estate Market and Renewable Energy Induce Carbon Dioxide Emissions? Novel Evidence from Turkey. Energies 15, 763. doi:10.3390/en15030763

Regulation (EU) No 537/2014 (2014). Regulation (EU) No 537/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on Specific Requirements Regarding Statutory Audit of Public-Interest Entities and Repealing Commission Decision 2005/909/EC. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32014R0537 (Accessed November 8, 2021).

Report on US Sustainable and Impact Investing Trends (2020). Report on US Sustainable and Impact Investing Trends. Available at: https://www.ussif.org/files/Trends%20Report%202020%20Executive%20Summary.pdf (Accessed December 28, 2021).

Samour, A., Baskaya, M. M., and Tursoy, T. (2022). The Impact of Financial Development and FDI on Renewable Energy in the UAE: A Path towards Sustainable Development. Sustainability 14 (3), 1208. doi:10.3390/su14031208

Samour, A., and Pata, U. K. (2022). The Impact of the US Interest Rate and Oil Prices on Renewable Energy in Turkey: a Bootstrap ARDL Approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-19481-8

Servaes, H., and Tamayo, A. (2013). The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Firm Value: The Role of Customer Awareness. Manag. Sci. 59, 1045–1061. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1120.1630

Shahbaz, M., Karaman, A. S., Kilic, M., and Uyar, A. (2020). Board Attributes, CSR Engagement, and Corporate Performance: What Is the Nexus in the Energy Sector? Energy Policy 143, 111582. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111582

Skoczylas, W., and Batóg, B. (2017). The Application of Taxonomic Measure of Development to the Evaluation of Financial Condition of Enterprises. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. we Wrocławiu 472, 387–397. doi:10.15611/pn.2017.472.35

Ślęzak-Gładzik, I. (2013). Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Jako Koncepcja Porządkująca Relacje Między Biznesem a Społeczeństwem. Mmr 18, 113–125. doi:10.7862/rz.2013.mmr.24

Stefaniak, S. (2019). Nowa Rola I Obowiązki Inwestorów Instytucjonalnych W Ładzie Korporacyjnym. Prakseologia 161, 63–94.

Strengthening Capital Markets (2021). Strengthening Capital Markets and Promoting Sustainable Finance. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/about/annual-report/strengthening-capital-markets (Accessed December 23, 2021).

Szczepankiewicz, E., and Mućko, P. (2016). CSR Reporting Practices of Polish Energy and Mining Companies. Sustainability 8, 126. doi:10.3390/su8020126

Tarczyńska-Łuniewska, M. (2013). Definition and Nature of Fundamental Strengths. Actual Problems Econ. 2, 15–23.

Tarczyńska-Łuniewska, M. (2013). Metodologia Oceny Siły Fundamentalnej Spółek (Giełdowych I Pozagiełdowych). Szczecin: Zapol.

Tarczyński, W. (1994). Taksonomiczna Miara Atrakcyjności Inwestycji W Papiery Wartościowe. Przegląd Stat. 41, 275–300. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2020.09.331

Tarczyński, W., Tarczyńska-Łuniewska, M., and Majewski, S. (2020). The Value of the Company and its Fundamental Strength. Procedia Comput. Sci. 176, 2685–2694. doi:10.1016/J.PROCS.2020.09.331

ter Horst, J. R., Zhang, C., and Renneboog, L. (2007). Socially Responsible Investments: Methodology, Risk Exposure and Performance. SSRN J. doi:10.2139/ssrn.985267

van Duuren, E., Plantinga, A., and Scholtens, B. (2016). ESG Integration and the Investment Management Process: Fundamental Investing Reinvented. J. Bus. Ethics 138, 525–533. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2610-8

Waygood, S. (2014). A Roadmap for Sustainable Capital Markets: How Can the UN Sustainable Development Goals Harness the Global Capital Markets? Available at: 10574avivabooklet.pdf (un.org) (Accessed November 21, 2021).

Witkowska, D., and Kuźnik, P. (2019). Does Fundamental Strength of the Company Influence its Investment Performance? Dyn. Econ. Models 19, 85–96. doi:10.12775/DEM.2019.005

Wollmert, P., and Hobbs, A. (2021). The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive Marks a Step Change in Reporting and in the Assurance of Nonfinancial Information. Available at: https://www.ey.com/en_be/assurance/how-the-eu-s-new-sustainability-directive-will-be-a-game-changer (Accessed November 8, 2021).

World Investment Report (2021). Investing in Sustainable Recovery. Available at: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2021_en.pdf#page=226 (Accessed November 14, 2021).

Yin, C., Ma, H., Gong, Y., Chen, Q., and Zhang, Y. (2021). Environmental CSR and Environmental Citizenship Behavior: The Role of Employees' Environmental Passion and Empathy. J. Clean. Prod. 320, 128751. doi:10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2021.128751

Keywords: fundamental strength, company’s value, ESG factors, legal aspects of ESG, energy transition

Citation: Tarczynska-Luniewska M, Flaga-Gieruszynska K and Ankiewicz M (2022) Exploring the Nexus Between Fundamental Strength and Market Value in Energy Companies: Evidence From Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance Perspective in Poland. Front. Energy Res. 10:910921. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2022.910921

Received: 01 April 2022; Accepted: 14 April 2022;

Published: 29 April 2022.

Edited by:

Diogo Ferraz, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, BrazilCopyright © 2022 Tarczynska-Luniewska, Flaga-Gieruszynska and Ankiewicz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Malgorzata Tarczynska-Luniewska, bWFsZ29yemF0YS50YXJjenluc2thQHVzei5lZHUucGw=

Malgorzata Tarczynska-Luniewska

Malgorzata Tarczynska-Luniewska Kinga Flaga-Gieruszynska2

Kinga Flaga-Gieruszynska2