- 1Strategic Emerging Industries Development Research Centers, Hunan University, Changsha, China

- 2Institutes of Science and Development, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

With the increasing share of renewable energy resources in the microgrid, the microgrid faces more and more challenges in its reliable operation. One major challenge is the potential congestion caused by the uncoordinated operation of flexible demands such as heat pumps and the high penetration of renewable energy resources such as photovoltaics. Therefore, it is important to conduct microgrid energy management to ensure its reliable operation. The energy storage system (ESS) scheduling as an efficient means to alleviate congestion has been widely used. However, in the existing literature, the ESSs are usually scheduled by the microgrid system operator (MSO) in a direct control manner, which is impractical in the case where customers own ESSs and are willing to schedule ESSs by themselves. To resolve this issue, this study proposes a network reconfiguration integrated dynamic tariff–subsidy (DTS) congestion management method to utilize ESSs and network reconfiguration to alleviate congestion in microgrids caused by renewable energy resources and flexible demands. In the proposed method, the MSO controls sectionalization switches while customers or aggregators schedule ESSs in response to DTS to alleviate congestion. The DTS calculation model is formulated as a mixed-integer linear programming model, considering heat pumps (HPs), ESSs, and reconfigurable microgrid topology. The numerical results demonstrate that the proposed method can effectively use ESSs and network topology to alleviate congestion and the MSO does not need to take over the scheduling of the ESS.

Introduction

To deal with energy shortage and environmental pollution issues, renewable energy resources, such as wind power and solar power, have been extensively integrated into the microgrid. The focus is on the microgrid because it might be the final link between the electricity grid and end-users and has significant impacts on the continued electricity supply. Thus, it is critical to ensure the reliable operation of the microgrid with high penetration of renewable energy resources (Omar and Hamdan, 2018).

The increasing penetration of renewable energy resources introduces great challenges to the microgrid operator. One major challenge is the potential congestion problem caused by the uncoordinated power consumption of flexible demands or the production of renewable energy resources, such as photovoltaics (PVs) (Huang et al., 2014). In order to resolve the congestion problem, a huge number of demand response (DR) schemes have been proposed to mitigate congestion. The DR can be considered as a program designed to change the electricity consumption patterns of end-users in response to electricity price changes or given incentives (U. S. Department of Energy, 2006). The DR programs can be classified into two types: 1) incentive-based DR programs and 2) price-based DR programs.

For the price-based DR programs, there are dynamic tariff (DT) method (Huang et al., 2015) (Li et al., 2014) (Shen et al., 2019), dynamic subsidy (DS) method (Huang and Wu 2016), shadow price method (Biegel et al., 2012), dynamic power tariff (DPT) method (Huang et al., 2019), and dynamic tariff–subsidy (DTS) method (Huang and Wu, 2019). All these methods are designed based on a common principle that the resulting electricity prices (spot prices plus tariffs or minus subsidies) at congested hours are higher than prices in those hours without congestion. Therefore, the aggregators will shift flexible demands to off-peak hours to minimize their energy costs and consequently resolve congestion. In Huang et al. (2015), Shen et al. (2019), Biegel et al. (2012), and Huang et al. (2019), the distribution system operator (DSO) collects tariffs at congested hours while the DSO in Huang and Wu (2016) pays a subsidy to the aggregators at uncongested hours. The DSO calculates tariffs or subsidies, based on which aggregators make their own energy schedules that respect system constraints. In Huang and Wu (2019), the DSO would collect tariffs or pay subsidies based on the congestion situation. If congestion is caused by the feed-in power from renewable energy resources, such as PVs, then the DSO pays subsidies to motivate customers to have more power consumption; otherwise, the DSO collects tariffs.

For the incentive-based DR programs, a monetary-based DR program was proposed in Sarker et al. (2015), in which customers reschedule power consumption in response to the incentives. The final incentives are determined by an iterative process between the DSO and the load-serving entity. In Zhang et al. (2014), Belhomme and Sebastian (2009), and Kulmala et al. (2017), local flexibility markets were built. In the local flexibility market, DSO can procure flexibility to resolve congestion and customers receive payments accordingly.

In addition, congestion might occur in real-time operation due to forecast errors and system failures. A coupon incentive-based DR program was developed by Zhong et al. (2013) to deal with the price spike and real-time congestion. The coupon incentives are sent to motivate customers to change their demands and submit the updated demand bids to the real-time market. In Haque et al. (2016), an agent-based real-time congestion management scheme was introduced, in which a DR scheme is first employed to resolve congestion and an active curtailment method is used afterward. In Huang and Wu (2018), a flexible demand swap-based DR scheme was proposed. In the scheme, the flexible demand swap occurs both temporally and spatially. The spatial swap represents power consumption exchange, that is, a power consumption decrease at one bus is compensated by a power consumption increase at another bus. The temporal swap allows the flexible demands to rebound their energy consumption in a specified period that has enough remaining loading amount. The swap-based DR scheme in Huang and Wu (2018) was extended in Shen et al. (2020a) by employing the transactive energy concept to consider the willingness of customers for providing flexibility.

However, energy storage system (ESSs) scheduling as an efficient means for congestion management has not been considered in the abovementioned literature. In Spiliotis et al. (2016), the authors developed a model to determine the optimal mix of incremental grid expansions and installed local energy storage. In Vatsala et al. (2020), the optimal location and sizing of ESSs were studied for transmission congestion management. The proposed model was solved by flower pollination algorithm combined with differential evolution algorithm. In Ehsan et al. (2019), the critical transmission lines in congestion are first identified and then distributed generation (DG) and ESSs are optimally scheduled to alleviate the envisaged congestion. However, the scheduling of ESSs in the abovementioned methods is based on direct control by the microgrid system operator (MSO), which is impractical in the case where end-users own their local ESSs and the system operator has no access to the control of local ESSs. Therefore, we extend the DTS concept in Huang and Wu (2019) in order to handle congestion of the microgrid through ESS scheduling in an indirect manner, that is, use price as control signals. In addition, network reconfiguration can be integrated with a market-based method to achieve the optimized congestion management. However, the integration of the DTS and network reconfiguration has not been studied in the existing literature.

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows: 1) compared with the existing works utilizing either network reconfiguration or DTS for congestion management, this work proposes to integrate network reconfiguration into the DTS method to alleviate congestion of microgrids. Accordingly, a novel network reconfiguration integrated DTS calculation model considering ESSs, PVs, and heat pumps (HPs) is formulated. 2) Compared with conventional frameworks in which the MSO controls ESSs to alleviate congestion directly, this work designs a new microgrid congestion management framework that uses ESSs locally to alleviate congestion in an indirect manner based on the prices; therefore, the MSO does not need to control local ESSs.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. The procedure of the proposed method for congestion management is presented in Procedure of the Proposed Method for Congestion Management. The model formulations at the DSO side and aggregator side and DTS calculations are presented in Model Formulation of the Proposed Method. Case studies are presented and discussed in Case Studies, followed by conclusions.

Procedure of the Proposed Method for Congestion Management

In this section, the concept of the DTS and the procedure of the proposed method for congestion management are presented.

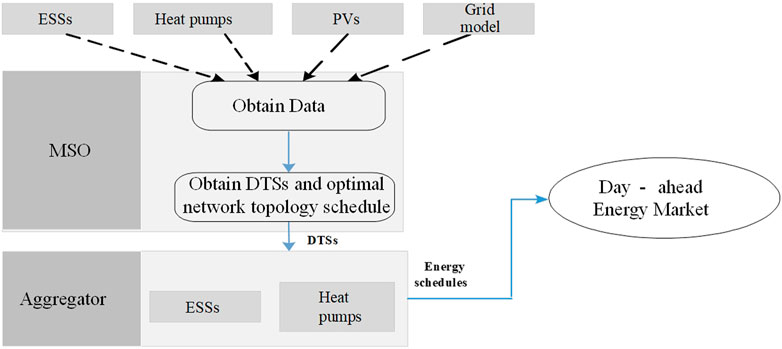

Compared with the DT method (Huang et al., 2015) and the DS method (Huang and Wu, 2016), the DTS at each hour can be positive or negative. The positive rates can be considered as DTs and negative rates play the same role as the DSs. Similar to the DT and the DS method, the DTS method is a decentralized market-based congestion management method. According to Huang and Wu (2019), the procedures of using the DTS to solve congestion are shown in Figure 1 as follows:

1) The MSO predicts the spot prices and obtains a grid model. The DSO also obtains ESSs data and flexible demand data from the aggregators or by its own prediction and obtains renewable energy resource data, such as power output profiles.

2) The MSO solves a DTS model considering system constraints to obtain the DTS and optimal network topology schedule and then sends DTSs to the aggregators.

3) The aggregators solve their own optimizations based on the spot prices and DTSs to make ESS and flexible demand schedules.

4) The aggregators submit day-ahead ESS energy schedules and flexible demand schedules to the day-ahead energy market.

In the proposed method, the aggregator acts as mediator among customers, the MSO, and the market operator. The aggregator has two roles: 1) submit energy bids and purchase energy from the day-ahead market on behalf of customers and 2) schedule flexible demands and ESSs for customers. In the proposed method, each customer is assigned to an aggregator by a contract. In this study, one aggregator is assumed for simplicity.

Model Formulation of the Proposed Method

In this section, model formulations at the MSO and the aggregator side and DTS calculations are presented.

Model Formulation at the MSO Side

The MSO solves an optimal power flow (OPF) model to determine the DTSs and network topology schedule. In the study, heat pumps as flexible demands and PVs as renewable energy resources are considered. In the day-ahead energy market, heat pumps submit energy schedules in order to meet power consumption needs and ESS submit energy schedules in order to gain profits, that is, ESSs charge power at hours with low energy prices and discharge power at hours with high energy prices.

The objective of the MSO optimization is to minimize the total energy schedule costs and switching operation costs, as follows:

The objective function consists of four terms: the first term is to minimize the HP energy cost, where Nhp and NT are set of HPs and day-ahead planning periods, respectively; ct is the spot price at hour t; Bi,t is the price sensitivity matrix corresponding to ith power consumption at hour t; and

The MSO optimization has the following constraints:

• Line loading constraints:

where Nb is the set of buses,

• Heat pumps constraints (Bacher and Madsen, 2011; Huang et al., 2015):

Constraints (3) and (4) represent thermal equations of the house equipped with the heat pump, where

• Energy storage system constraints (Shen et al., 2020b):

Constraint (7) is the ESS energy balance constraint, where

• Network radiality constraints:

Constraint (11) is the network radiality constraint, representing that the number of closed switches is equal to the number of vertexes (

After solving the MSO optimization problem, the DTS (

Model Formulation at the Aggregator Side

The indirect congestion management idea is that, through the link of DTSs, the aggregator can solve the aggregator optimization model to make energy schedules that respect system operational constraints such as line loading constraints without needing to incorporate the system operational constraints into the aggregator optimization model. Therefore, compared with the MSO optimization model, the objective function of the aggregator optimization model has an extra term associated with the DTSs, and the system operational constraints are not modeled. After receiving the DTSs, the aggregator determines its energy schedules by solving the following optimization model.

• Objective function:

The objective function of the aggregator optimization model consists of four terms: the first term is to minimize the HP energy cost, the second term is to minimize the energy cost of ESS charging power, the third term is to maximize the profit of ESS discharging power, and the last term is to minimize the energy cost associated with DTSs.

• Constraints

The constraints of the aggregator optimization model are ESS and HP operation constraints in (3)–(10).

Equivalence of the Solutions at the MSO Side and at the Aggregator Side

In order to demonstrate the equivalence of the solutions at the MSO and aggregator side, the KKT conditions of the MSO optimization and aggregator optimization are derived (Chen et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019; Cheng et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2019). For simplicity, the KKT conditions of the MSO optimization are presented as follows:

Comparing the KKT conditions of the MSO optimization with the KKT conditions of the aggregator optimization, it can be easily demonstrated that the solution of the aggregator optimization is the same as the solution of the MSO optimization. This indicates that the solution obtained with aggregator optimization respects the system line loading constraints even if the line loading constraints are not considered, which enables a decentralized congestion management scheme.

Case Studies

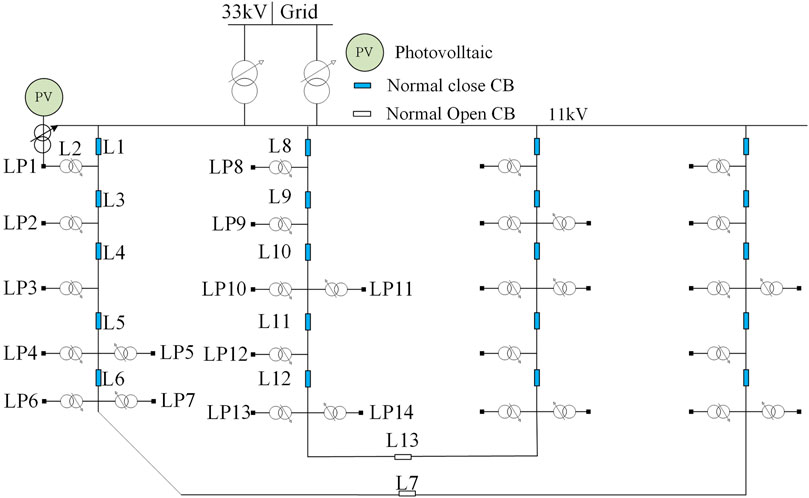

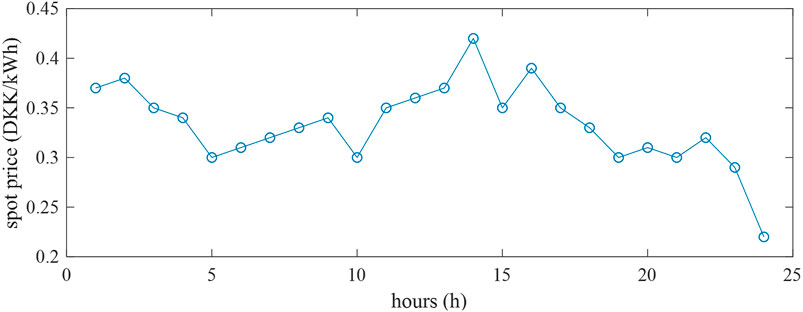

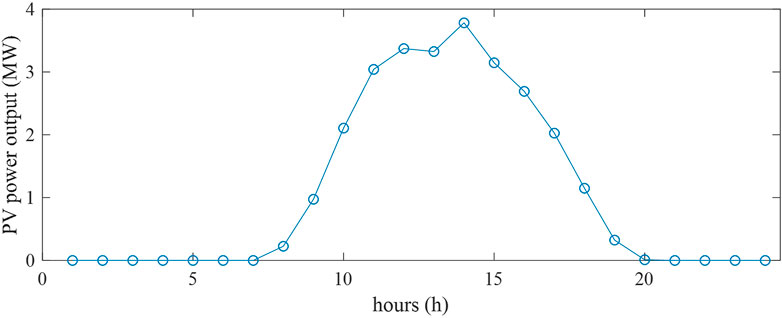

Numerical simulations were conducted on the Roy Billinton Test System (RBTS) (Allan et al., 1991) in four scenarios to validate the congestion management effectiveness of the network reconfiguration integrated DTS method for the microgrid. The diagram of the microgrid is shown in Figure 2. The microgrid consists of four feeders, and the study studies congestion management on feeder 1. Line segments of feeder 1 are labeled as L1-L12 and load points are labeled as LP1-LP5. The parameters of load points and line segments can be found in Huang et al. (2015). Figures 3, 4 show the spot price and PV power output profiles. The key parameters of heat pumps and ESSs and system parameters are given in Table 1.

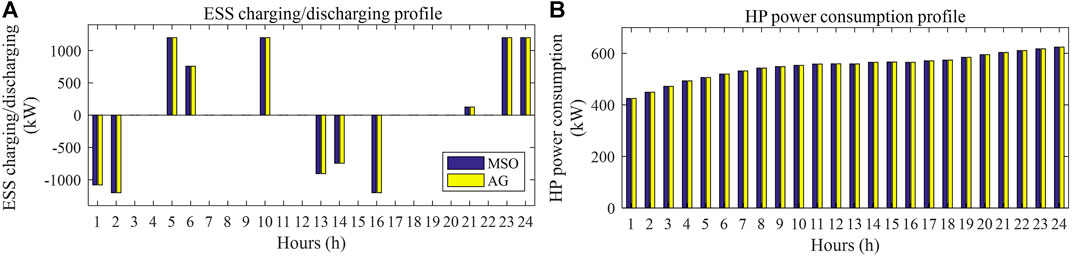

Validation of Solution Equivalence of the MSO and Aggregator Optimization Models

The equivalence of solutions of the MSO and aggregator optimizations is validated in this subsection. The total charging/discharging power of ESSs and total power consumption of heat pumps at LP1 obtained with the MSO optimization and the aggregator optimization in scenario 1 are shown in Figure 5, respectively. It is shown that the aggregator optimization has the same solution as the MSO optimization, which indicates that the aggregator acts as the MSO expects through the DTS signals. Therefore, even if the line loading constraints are not considered in the aggregator optimization model, the aggregator solution respects the line loading constraints, which means that indirect congestion management is realized.

Congestion Management Results

In this subsection, the congestion management effectiveness of the proposed congestion management method is validated in case 1 with two scenarios (scenario 1 and scenario 2). The benefit of combining network reconfiguration and DTSs to alleviate congestion is demonstrated in case 2 with two scenarios (scenario 2 and scenario 3). In case 3, the benefit of utilizing ESSs to alleviate congestion is validated with a scenario (scenario 4).

Case 1: Validation of Congestion Management Effectiveness

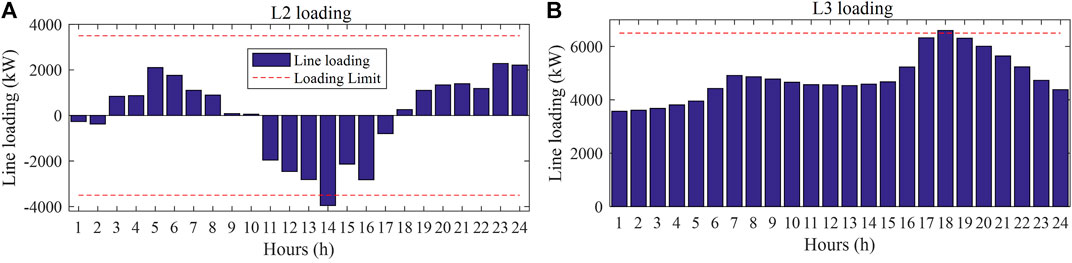

In this case, the congestion management effectiveness of the proposed congestion management method is validated with scenarios 1 and 2. Without conducting congestion management, the DTS are zero and default network topology is used. The aggregators solve aggregator optimization models based on zero DTSs to make energy schedules, which causes congestion on L2, L3, and L8. Due to limited space, the line loadings of L2 and L3 (the negative line loading means feed-in power flow) are shown in Figure 6. It is shown that congestion occurs due to peak HP power consumption, such as t18 on L3, and PV feed-in power generation, such as t14 on L2. It is concluded that DERs could cause congestion in microgrids if DERs are not well coordinated.

FIGURE 6. (A) Line loading of L2 before congestion management in scenario 1, (B) line loading of L3 before congestion management in scenario 1.

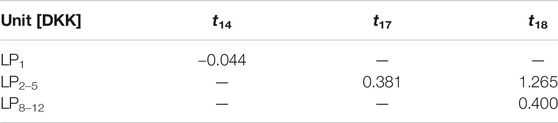

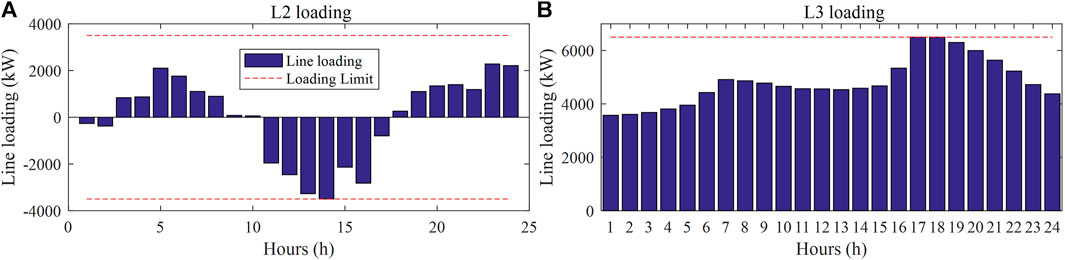

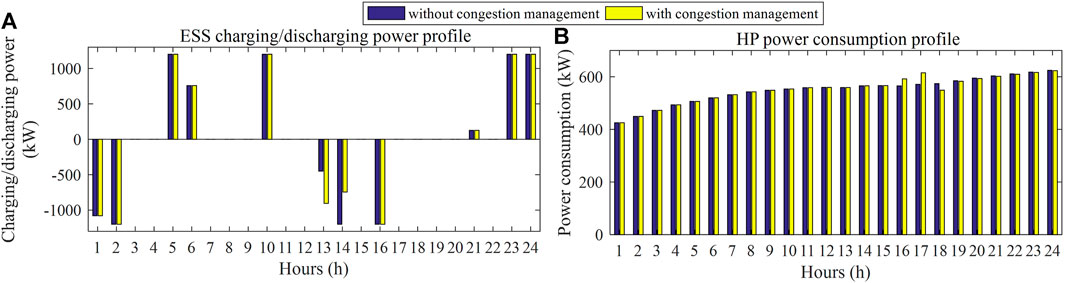

Then, the proposed congestion management method is carried out. In scenario 1, congestion can be resolved efficiently, as shown in Figure 7. After the MSO solves the MSO optimization problem, the part of DTSs obtained is listed in Table 2. It is shown that DTSs could be positive or negative. The DTSs are negative on LP1 at t14, so the final electricity prices (spot price plus DTSs) can be reduced. Therefore, ESSs would discharge less power at these hours and discharge more power at other hours, for example, t13, to maximize energy costs, so the congestion caused by feed-in power can be resolved, as shown in Figure 8. In contrast, the DTSs are positive on LP2–5 at t18 in order to increase the final electricity prices at these hours, so the HP would shift power consumption from these hours to other hours, for example, t16, to minimize energy costs, as shown in Figure 8. Therefore, congestion caused by peak HP power consumption can be resolved. In addition, in this scenario, the network topology remains unchanged during the scheduling horizon, which means that it has a smaller cost by utilizing DTSs to alleviate congestion solely.

FIGURE 7. (A) Line loading of L2 after congestion management in scenario 1, (B) line loading of L3 after congestion management in scenario 1.

FIGURE 8. (A) Comparisons of ESS charging/discharging power before and after congestion management in scenario 1, (B) comparisons of HP power consumption before and after congestion management in scenario 1.

In scenario 2, a more severe congestion situation is simulated by reducing the line loading limits of L3, as shown in Table 1. After performing the proposed congestion management method, congestion can be completely resolved as well. However, compared with scenario 1, since the line loading limit of L3 is reduced, utilizing DTSs to alleviate congestion solely will cause a higher cost, which will be detailed in case 2. Therefore, the MSO chooses to combine network reconfiguration and DTSs to alleviate congestion. At t12, the MSO opens the switch on L6 and closes the switch on L7 to shift power consumption on LP6-7 to feeder 4 in order to alleviate congestion on L3.

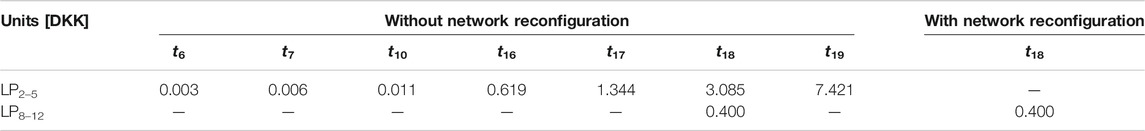

Case 2: Validation of Benefit of Combining Network Reconfiguration and DTSs

In this case, the benefit of combining network reconfiguration and DTSs to alleviate congestion is demonstrated. As mentioned previously in scenario 2 in case 1, the MSO combines network reconfiguration and DTSs to alleviate congestion. This is because the combination of network reconfiguration and DTSs leads to a smaller energy cost (26,105.40 DKK) as compared to the one (28,945.22 DKK) when DTSs are used only. In addition, the part of DTs obtained with and without considering network reconfiguration is listed in Table 3. It can be seen that there is no need to impose DTs at LP2–5 during the scheduling horizon when network reconfiguration is used, whereas there are high DTs required without considering network reconfiguration. Therefore, it can be concluded that integrating network reconfiguration into the DTS method can significantly reduce DTs and the congestion management cost.

In order to further validate the benefit of the combination of network reconfiguration and DTSs, a more severe congestion situation is simulated in scenario 3 by reducing the line loading limit of L8. After carrying out the proposed congestion management method, congestions on L2, L3, and L8 can be alleviated completely, as shown in Figure 9 (only line loadings on L3 and L8 are shown). At t11, the MSO opens the sectionalization switch on L11 and closes the tie-line switch on L13 to shift power consumption on LP12 and LP13–14 to feeder 3 to alleviate congestion on L8. Compared with scenario 2, loads are shifted to feeder 3 to alleviate congestion since line loading limits are reduced. In addition, at t11, the MSO opens the switch on L6 and closes the switch on L7 to shift power consumption on LP6–7 to feeder 4 in order to alleviate congestion on L3. In this scenario, the MSO problem becomes infeasible if network reconfiguration is not considered, so congestion cannot be resolved completely without utilizing network reconfiguration. Therefore, it can be concluded from the results that using DTSs only may not alleviate severe congestion, and integrating network reconfiguration can achieve better congestion management performance.

FIGURE 9. (A) Line loading of L3 after congestion management in scenario 3, (B) line loading of L8 after congestion management in scenario 3.

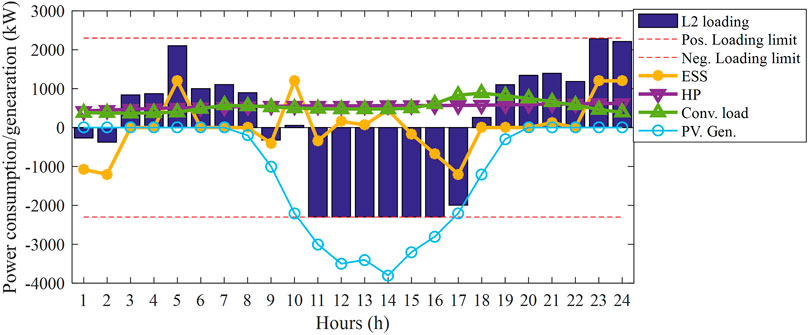

Case 3: Validation of Benefit of Utilizing ESSs

The benefit of utilizing ESSs to alleviate congestion is demonstrated in scenario 4. Compared with scenario 1, the same parameters are used except that the line loading limit of L2 is reduced. After performing the proposed congestion management method, congestion can be completely alleviated, as shown in Figure 10 (only line loadings on L2 are shown). It can be seen in Figure 10 that ESSs charge power generated by the PV at t12, t13, and t14 to alleviate congestion caused by feed-in power. However, when the ESS operation is not considered, the MSO problem is infeasible because there is no flexibility that can be used to resolve congestion caused by PV feed-in power. Therefore, it can be concluded that the ESS can be used to efficiently alleviate congestion caused by load consumption or power generation.

Analysis of ESS Profit

It is shown in Figure 5 that ESSs charge and discharge frequently in order to gain profits in the day-ahead energy market by charging power at hours with low energy prices and by discharging power at hours with high energy prices, for example, discharge power at t1 and t2 and charge power at t5 and t6. The profits of ESSs before and after congestion management are 369.13 DKK and 348.93 DKK, respectively. It can be seen that participation of congestion management would reduce ESSs’ profits, which is as expected.

Conclusion

This study proposes a network reconfiguration integrated DTS congestion management method to utilize ESSs and network reconfiguration to alleviate congestion in microgrids. The numerical results demonstrate that, in the proposed method, customers schedule ESSs by themselves to gain profits in the day-ahead energy market and at the same time respond to the price signals to alleviate congestion. To alleviate congestion caused by feed-in power flow, DTSs are negative at congestion hours. In such a case, ESSs decrease discharging power at congestion hours due to reduced energy prices and increase discharging power at hours with higher energy prices in order to gain profits, which consequently help mitigate congestion caused by feed-in power flow. To alleviate congestion caused by flexible demands, DTSs are positive at congestion hours. Therefore, the final resulting price at congestion hours increases, which motivates the aggregator to shift power consumption from congestion hours to off-peak hours in order to minimize energy costs, which consequently resolve congestion. In addition, numerical results demonstrate that integrating network reconfiguration into the DTS method can significantly reduce DTs and is beneficial to congestion management.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

YC: conceptualization, methodology, software, and writing. YL: review and editing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allan, R. N., Billinton, R., Sjarief, I., Goel, L., and So, K. S. (1991). A Reliability Test System for Educational Purposes-Basic Distribution System Data and Results. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 6 (2), 813–820. doi:10.1109/59.76730

Bacher, P., and Madsen, H. (2011). Identifying Suitable Models for the Heat Dynamics of Buildings. Energy Build. 43 (7), 1511–1522. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2011.02.005

Belhomme, R., and Sebastian, M. (2009). Deliverable 1.1 ADDRESS – Technical and Commercial Conceptual Architectures. Paris: University of Manchester Report.

Biegel, B., Andersen, P., Stoustrup, J., and Bendtsen, J. (2012). “Congestion Management in a Smart Grid via Shadow Prices,” in Proc. 8th IFAC Symp. on Power Plant and Power System Control, Toulouse, France, September 2–5, 2012, IFAC Proc. Volumes 45, 518–523. doi:10.3182/20120902-4-fr-2032.00091

Chen, Q., Shi, H., and Sun, M. (2019). Echo State Network Based Backstepping Adaptive Iterative Learning Control for Strict-Feedback Systems: an Error-Tracking Approach. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 50 (7), 1–14. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2019.2931877

Chen, Q., Xie, S., Sun, M., and He, X. (2018). Adaptive Nonsingular Fixed-Time Attitude Stabilization of Uncertain Spacecraft. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 54 (6), 2937–2950. doi:10.1109/taes.2018.2832998

Cheng, F., Qu, L., Qiao, W., Wei, C., and Hao, L. (2019). Fault Diagnosis of Wind Turbine Gearboxes Based on DFIG Stator Current Envelope Analysis. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energ. 10 (3), 1044–1053. doi:10.1109/tste.2018.2859764

Ehsan, D., Farrokh, A., and Saeed, A. (2019). Congestion Management through Distributed Generations and Energy Storage System. Int. Trans. Electr. Energ. Syst. 29 (6), 1–12. doi:10.1002/2050-7038.12018

Omar, N., and Hamdan, I. (2018). Design of Robust Intelligent protection Technique for Large-Scale Grid-Connected Wind Farm. Prot. Control. Mod. Power Syst. 3 (3), 169–182.

Haque, A. N. M. M., Shafiullah, D. S., Nguyen, P. H., and Bliek, F. W. (2016). “Real-time Congestion Management in Active Distribution Network Based on Dynamic thermal Overloading Cost,” in 2016 Power Systems Computation Conference, Genoa, Italy, June 20–24, 2016 (Genoa: PSCC), 1–7.

Huang, S., Wu, Q., Liu, Z., and Nielsen, A. (2014). “Review of Congestion Management Methods for Distribution Networks with High Penetration of Distributed Energy Resources,” in Proc. of IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Istanbul, Istanbul, Turkey, October 12–15, 2014, 1–6.

Huang, S., and Wu, Q. (2016). Dynamic Subsidy Method for Congestion Management in Distribution Network. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 9 (3), 2140–2151. doi:10.1109/tsg.2016.2607720

Huang, S., and Wu, Q. (2019). Dynamic Tariff-Subsidy Method for PV and V2G Congestion Management in Distribution Networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 10 (5), 5851–5860. doi:10.1109/tsg.2019.2892302

Huang, S., Wu, Q., Oren, S. S., Li, R., and Liu, Z. (2015). Distribution Locational Marginal Pricing through Quadratic Programming for Congestion Management in Distribution Networks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 30 (4), 2170–2178. doi:10.1109/tpwrs.2014.2359977

Huang, S., and Wu, Q. (2018). Real-Time Congestion Management in Distribution Networks by Flexible Demand Swap. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 9 (5), 4346–4355. doi:10.1109/tsg.2017.2655085

Huang, S., Wu, Q., Shahidehpour, M., and Liu, Z. (2019). Dynamic Power Tariff for Congestion Management in Distribution Networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 10 (2), 2148–2157. doi:10.1109/tsg.2018.2790638

Kulmala, A., Alonso, M., Repo, S., Amaris, H., Moreno, A., Mehmedalic, J., et al. (2017). Hierarchical and Distributed Control Concept for Distribution Network Congestion Management. IET Generation, Transm. Distrib. 11 (3), 665–675. doi:10.1049/iet-gtd.2016.0500

Li, R., Wu, Q., and Oren, S. S. (2014). Distribution Locational Marginal Pricing for Optimal Electric Vehicle Charging Management. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 29 (1), 203–211. doi:10.1109/tpwrs.2013.2278952

Sarker, M. R., Ortega-Vazquez, M. A., and Kirschen, D. S. (2015). Optimal Coordination and Scheduling of Demand Response via Monetary Incentives. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 6 (3), 1341–1352. doi:10.1109/tsg.2014.2375067

Shen, F., Huang, S., Wu, Q., Repo, S., Xu, Y., and Ostergaard, J. (2019). Comprehensive Congestion Management for Distribution Networks Based on Dynamic Tariff, Reconfiguration, and Re-profiling Product. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 10 (5), 4795–4805. doi:10.1109/tsg.2018.2868755

Shen, F., Wu, Q., Huang, S., Chen, X., Liu, H., and Xu, Y. (2020). Two-Tier Demand Response with Flexible Demand Swap and Transactive Control for Real-Time Congestion Management in Distribution Networks. Int. J. Electr. Power Energ. Syst. 114, 105399. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2019.105399

Shen, F., Wu, Q., Zhao, J., Wei, W., Hatziargyriou, N. D., and Liu, F. (2020). Distributed Risk-Limiting Load Restoration in Unbalanced Distribution Systems with Networked Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 11 (6), 4574–4586. doi:10.1109/tsg.2020.2995099

Spiliotis, K., Claeys, S., Gutierrez, A. R., and Driesen, J. (2016). “Utilizing Local Energy Storage for Congestion Management and Investment Deferral in Distribution Networks,” in 2016 13th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), Porto, Portugal, June 6–9, 2016 (Porto), 1–5.

U.S. Department of Energy (2006). Benefit of Demand Response in Electricity Market and Recommendations for Achieving Them.

Vatsala, S., Pratima, W., and Anwar, S. S. (2020). Hourly Congestion Management by Adopting Distributed Energy Storage System Using Hybrid Optimization. J. Electr. Syst. 16 (2), 257–275.

Wei, C., Benosman, M., and Kim, T. (2019). Online Parameter Identification for State of Power Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries in Electric Vehicles Using Extremum Seeking. Int. J. Control. Autom. Syst. 17 (11), 2906–2916. doi:10.1007/s12555-018-0506-y

Zhang, C., Ding, Y., Nordentoft, N. C., Pinson, P., and Østergaard, J. (2014). FLECH: A Danish Market Solution for DSO Congestion Management through DER Flexibility Services. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean. Energ. 2 (2), 126–133. doi:10.1007/s40565-014-0048-0

Keywords: congestion management, microgrid, dynamic tariff–subsidy, energy storage system, renewable energy resources

Citation: Chen Y and Liu Y (2021) Congestion Management of Microgrids With Renewable Energy Resources and Energy Storage Systems. Front. Energy Res. 9:708087. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2021.708087

Received: 11 May 2021; Accepted: 05 July 2021;

Published: 02 August 2021.

Edited by:

Jianwu Zeng, Minnesota State University, Mankato, United StatesReviewed by:

S. M. Suhail Hussain, National University of Singapore, SingaporeHamed Bizhani, University of Zanjan, Iran

Copyright © 2021 Chen and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yaling Chen, NDIyNzY4Mjk0QHFxLmNvbQ==

Yaling Chen

Yaling Chen Yinpeng Liu2

Yinpeng Liu2