94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Energy Res. , 28 May 2021

Sec. Bioenergy and Biofuels

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2021.679709

This article is part of the Research Topic High-performance Catalytic Processes for Biofuel Production View all 6 articles

Heteropoly acids containing Brønsted and Lewis acids show excellent catalytic activity. Brønsted acids promote the depolymerization of polysaccharides (such as starch and cellulose) into glucose, while Lewis acids catalyze the conversion of glucose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF). Designing stable Brønsted-Lewis acid-containing bifunctional heterogeneous catalysts is crucial for the efficient catalytic conversion of polysaccharides to HMF. In this study, a series of Brønsted -Lewis acid bifunctional catalysts (SnxPW, X = 0.10–0.75) were investigated for the conversion of cassava starch to HMF. The structure of the catalysts was characterized by X-ray diffraction, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, Pyridine Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. The acid strength and acid capacity were also investigated. The effects of reaction time, temperature, catalyst concentration, and cassava starch concentration on the selectivity, conversion rate, and yield were examined. The results showed that, among the analyzed catalysts, Sn0.1PW presented the best ability under the test conditions for catalyzing the conversion of starch to HMF. At the optimized conditions of a reaction temperature of 160°C, a catalyst dosage of 0.50 mmol/gstarch, and a 1 h reaction time, the starch conversion rate was 90.61%, and the selectivity and yield of HMF were 59.77 and 54.12%, respectively. Our findings contribute to the development of HMF production by the dehydration of carbohydrates.

Abundant renewable biomass is an ideal and promising alternative for the production of valuable chemicals (Perea-Moreno et al., 2019). Among various compounds derived from biomass, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) is an important and versatile platform intermediate for the production of fuels and chemicals such as 2,5-furandicarboxilic acid (FDCA), 2,5-dhydroxymethylfuran (2,5-DMF), 5-ethoxymethylfurfural (5-EMF), and levulinic acid (LA). Among these chemicals, 2,5-DMF and 5-EMF have attracted much attention because of their excellent biofuel characteristics. 5-EMF can be prepared without a cumbersome hydrogenation step, requiring only HMF and ethanol etherification (Mascal and Nikitin, 2008). At present, multiple catalysts have been reported for the catalytic conversion of HMF to 2.5-DMF (Huang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014). 5-EMF is considered a very good fuel additive. Its energy density is close to that of gasoline (8.8 kwh/L) and diesel (8.7 kwh/L), and higher than that of fuel ethanol (6.1 kwh/L; Mascal and Nikitin, 2008). FDCA may replace terephthalic acid, the main component of polyethylene terephthalate. Based on the wide application of FDCA as a platform chemical, FDCA is listed as one of the 12 important glycosyl platform chemicals for the production of bio-based chemicals and materials.

Various carbohydrates can be used to synthesize HMF, e.g., fructose (Akien et al., 2012), glucose (Chheda et al., 2007), sucrose (Yu et al., 2017), starch (Chun et al., 2010), and cellulose (Fang et al., 2020). Generally, there are two pathways for the conversion of glucose to HMF. One is the direct dehydration of glucose to HMF, and the other includes two steps: glucose isomerization to fructose, followed by the dehydration of fructose to HMF (Choudhary et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2018). The first pathway is usually more difficult than the second one because of the different homomorphic conformation distributions of glucose and fructose in solution. While the isomerization of glucose into fructose is usually completed in an alkaline reaction system (Binder and Raines, 2009; Su et al., 2009), the dehydration of fructose to HMF requires an acidic environment (Nie et al., 2020). The introduction of metal ions through Brønsted acidification of heteropoly acids (HPAs) can form a range of insoluble solid Lewis-Brønsted acidic catalysts that are effective in the conversion of glucose and sucrose to HMF (Carniti et al., 2011; Deng et al., 2012). These heterogeneous acid catalysts possess Lewis (metal sites) and Brønsted acidic sites. Zhao et al. (2011) reported that the catalytic conversion of fructose to HMF, with solid HPA and Cs2.5H0.5PW12O40 as catalysts, presented excellent selectivity (94.7%) and a relatively high yield (74.0%) after 60 min at 388 K. This new catalyst is tolerant to high feedstock concentrations, and it can be recycled. Hu et al. (2009) revealed that Sn4+ can efficiently catalyze the conversion of sucrose to HMF in an ionic liquid, with a maximum yield of 65%. The Sn atoms act as isolated Lewis acid centers and are responsible for the isomerization of glucose to fructose. The bifunctional PTSA-POM/AlCl3.6H2O (60.7%HMF yield) catalyst showed a higher activity than the Lewis acid catalyst AlCl3.6H2O (50.8% HMF yield) and the Brønsted acid catalyst PTSA-POM (9.4% HMF yield), and directly transformed glucose to HMF owing to the balanced Lewis and Brønsted acid sites, with a 60.7% HMF yield (Xin et al., 2017). These results indicated that a bifunctional acid catalyst with balanced Brønsted and Lewis acid sites can obtain a high yield of HMF from hexose. In general, a high HMF yield can be obtained from monosaccharides, such as fructose and glucose (Nie et al., 2020). SnCl4 is a common Lewis acid, being cost-effective, highly active, and having a low toxicity, which is often used in glucose conversion to HMF (Hu et al., 2009; Qiu et al., 2020). However, fructose and glucose are not abundant, and thus, are expensive, thereby limiting the large-scale sustainable production of HMF. Therefore, an efficient process must be developed to produce HMF using starch, cellulose, and other cheap polysaccharides as raw materials. Starch is one of the most abundant carbohydrates on earth and is widely explored in the chemical industry (Hornung et al., 2016). It consists of two polysaccharides, namely amylose and amylopectin, and its D-glucopyranosyl units are linked through α-1,4 and α-1,6-glycosidic bonds. The glycosidic bonds are unstable in acid solution and can be easily hydrolyzed to glucose. Chheda et al. (2007) used hydrochloric acid as catalyst to prepare HMF from starch in a water-MIBK-sec-butyl alcohol solvent mixture, with a yield of 43%. Wu et al. (2018) reported that homogeneous Fenton reagent was able to promote starch dehydration, and a 46.5% yield of HMF was achieved. Nikolla et al. (2011) obtained a 51.75% yield of HMF using β-zeolite containing tin (Sn) and hydrochloric acid in a water/tetrahydrofuran two-phase system. However, because the yield of HMF prepared from starch is generally low, it is important to develop an efficient catalyst for the effective utilization of starch.

In this paper, we report a catalytic SnxP system with a controllable amount of Brønsted and Lewis acids. Different amounts of SnCl4 were introduced into phosphotungstic acid to prepare catalysts with different amounts of Brønsted and Lewis acids for the production of HMF from starch. Here, Sn provides Lewis acid sites that promote the isomerization of glucose to fructose, while phosphotungstic acid (HPW) provides Brønsted acid sites that promote starch hydrolysis to glucose and fructose and then dehydration to HMF. We found a significant increase in HMF yield when moving from HPW to Sn-doped HPW, without any significant structural changes to the catalyst, which we attribute to the introduction of Lewis acid sites to the catalyst. The effects of reaction temperature, reaction time, catalyst, and substrate concentration on the conversion of cassava starch, HMF yield, and selectivity were studied.

Cassava starch was obtained from Hongfeng Starch Co., Ltd. (Guangxi, China). Methanol and glacial acetic acid were of chromatographic grades, and all other reagents were of analytical grade and used without further purification. Phosphotungstic acid hydrate, Sn chloride (99.998%), 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furadehyde (99%), dimethyl sulfoxide (anhydrous solvent grade), and tetrahydrofuran (anhydrous solvent grade) were obtained from Shanghai Aladdin Industrial Inc. (China).

Sn phosphotungstate catalysts SnxPW (x = 0.10–0.75) were synthesized as reported in the literature (Okuhara et al., 2000). A series of SnxPWs were prepared by titration, with the Sn content ranging from 0.1 to 0.75 mmol. Six parts of phosphotungstic acid (1 mmol) were completely dissolved in 100 ml of distilled water, into which SnCl4 was slowly added, respectively. These mixtures were maintained under magnetic stirring at 60°C for 6 h until the solution was clear and transparent. Subsequently, the prepared solution was slowly dried at 60°C until the water completely evaporated and a white solid appeared. After drying, the white precipitate was calcined in a tubular furnace at 300°C for 2 h under a nitrogen atmosphere. Subsequently, the catalysts of SnxPW (x = 0.10, 0.20, 0.30, 0.40, 0.50, 0.60, and 0.75) were obtained.

The chemical structure of the catalysts was analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD; Mini-Flex600), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR; Tensor II, Bruker), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; Thermo Scientific K-Alpha+), and inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES; 7,700 e, Agilent). The XRD test conditions were as follows: Cukα ray (λ) of 0.15406 nm, Ni filter, 40 kV, and 40 mA; and the data were collected in the 2θ range of 5–80° with a step of 0.02° at a scanning speed of 5°/min. FTIR spectroscopy was performed using a potassium bromide tablet method. The wavelength scanning range was 4,000–400 cm−1, and the scanning was performed 32 times. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; Thermo Scientific K-Alpha+) with a monochromatized Alka X-ray source (1,486.6 eV) was used to analyze the relative atomic ratios and chemical environment of the elements in the catalyst. The analyzer was operated in the constant analyzer energy mode, and the vacuum in the analysis chamber was approximately 5 × 10–9 mbar. The measured high-resolution XPS spectra were analyzed using a Thermo Avantage v5.9921 trial version. The charge of the tested catalysts was corrected using an indeterminate carbon signal and Thermo Scientific K-Alpha+ with a monochromatized Alka X-ray source (1,486.6 eV). The energy mode and vacuum were the same as in the previous analysis chamber, with a binding energy of 284.8 eV. The relative content of the elements in the catalyst was analyzed by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES; 7,700 e, Agilent). The amount and ratio of Brønsted and Lewis acids in the catalysts were measured using Pyridine Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (Py-IR; Thermo Fisher Nicolet iS50). The catalyst was treated at 200°C for 2 h in a vacuum, cooled to room temperature, and then adsorbed with anhydrous pyridine for 30 min. The temperature was raised at 5°C/min, and the data were recorded at 120, 180, and 350°C.

Following a previously reported method (Shi et al., 2012), we measured the Hammett acid strength by exposing the catalysts (5 mg) to an ethanol solution to select Hammett indicators (methyl red: pKa = +4.8; 4-nitroaniline standard: pKa = +0.99; dicinnamalacetone: pKa = −3.0; chalcone: pKa = −5.6; anthraquinone: pKa = −8.2; p-nitrotoluene: pKa = −11.35), as summarized in Supplementary Table S1. Based on the results, dicinnamalacetone was used as an indicator. Spectrophotometry was used to evaluate the acidic function of the catalyst (Kondamudi et al., 2010; Parveen et al., 2016). The catalyst samples (5 mg) were suspended in ethanol solution and ultrasonicated for 2 h. The Hammett acidity function (Brei, 2003) was determined by spectrophotometry using the chosen indicator. The experiments for each samples were run in triplicate, and the average values were analyzed. The Hammett acid strength (H0) was described in Eq. 1.

where

Starch hydrolysis was conducted in a 50 ml steel autoclave lined with quartz. In a typical run, starch (0.2 g), DMSO (4.5 ml), THF (10.5 ml), saturated NaCl solution (5 ml), and catalyst (0.1 mmol) were added to the reactor and well mixed. The reaction mixture was heated to a specified temperature under continuous stirring (400 rpm). After the reaction was completed, the reactor was quickly cooled in an ice bath, and the mixture was centrifuged to separate the filtrate from the unreacted starch (3,000 rpm, 10 min). The filtrated solution, which was used to produce HMF, was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The conversion of starch was determined based on the mass change of the solid mixture. The starch dehydration to HMF in DMSO-THF-water mixtures using Sn phosphotungstate catalyst was influenced by several parameters, including catalyst acidity and strength, time, temperature, amount of catalyst, initial starch concentration, and catalyst Sn4+ content. The addition of DMSO and THF as co-solvents for water binding had three functions (Pumrod et al., 2020): limiting the rehydration of HMF to form formic acid (FA) and LA, improving the reaction rate, and ensuring that no insoluble humus was formed.

The concentration of HMF in the reaction mixture was measured by the external standard method and detected by HPLC (1,260II, Agilent) using an ultraviolet detector and a ZORBAX Eclipse XDC-C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5-Micron, Agilent, United States) at 284 nm. The column was operated at 30°C, and the detector at 40 °C. A 90:10 (V:V) mixture of 1% glacial acetic acid solution (by volume fraction) and methanol were used as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The injection volume was 20 µL for a filtered (0.22 µm) 10-fold diluted sample. The yield and selectivity of HMF and the conversion rate of starch are shown in Eqs 2–4, respectively.

where C1 and C2 are the molar concentrations of HMF in water and organic solvent, respectively, in mg/ml; V1 and V2 are the volumes of water and organic solvents, respectively, in mL; MD is the average relative molecular weight of starch; md is the starch quality before the reaction, in mg; and ms is the starch weight after the reaction, in mg.

The XRD patterns of HPW, Sn0.1PW, and Sn0.75PW are shown in Figure 1. Pure HPW shows characteristic diffraction peaks at 10.35°, 14.60°, 17.85°, 20.79°, 23.25°, 25.49°, 29.50°, 31.32°, 34.71°, and 37.83° (Ren et al., 2015), respectively. The main diffraction peaks of Sn0.1PW and Sn0.75PW were similar to those of HPW, indicating that the HPAs (i.e., Sn phosphotungstate) still preserved the crystallinity and secondary structure of HPW, despite the addition of Sn ions.

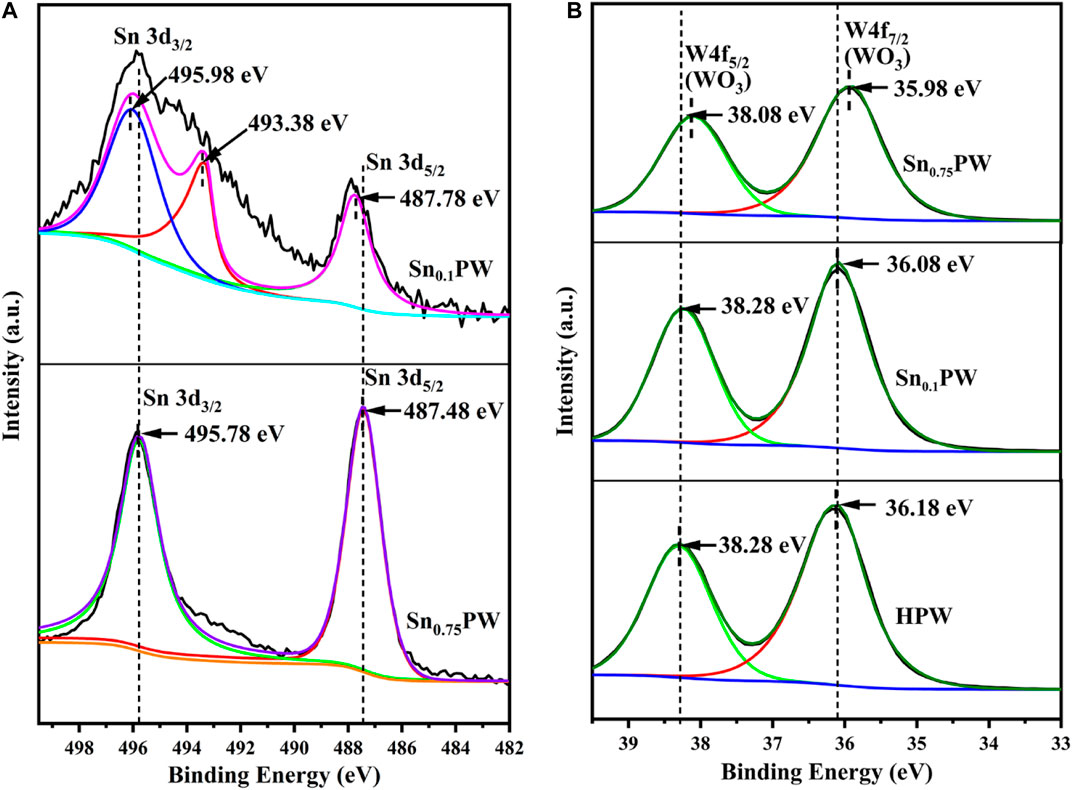

The FTIR spectra of Sn0.1PW, Sn0.75PW, and HPW are shown in Figure 2. HPW presented four characteristic peaks of tetrahedral oxygen P-Oa, non-shared oxygen for each octahedron (end oxygen) W=Od, different trimetallic cluster corner top-shared oxygen (Bridge Oxygen) W-Ob, and the same trimetallic cluster-shared oxygen (Bridge Oxygen) W-Oc at 1,080, 983, 887, and 805 cm−1, respectively, which were attributed to typical Keggin anions (Rafiee et al., 2005). For Sn0.1PW and Sn0.75PW, the four characteristic peaks were also clearly observed, but their intensities clearly decreased. Therefore, the Sn0.1PW and Sn0.75PW catalysts maintained the unique Keggin structure of H3PW12O40, and the basic structure of HPA remained unchanged. Sn did not enter the internal structure of heteropoly anions, as it was located outside the heteropoly anions as counter charge ion (Marcio Jose da and Cesar Macedo de, 2018). To further understand the surface composition discrepancy of Sn0.1PW, Sn0.75PW, and HPW, the high-resolution XPS spectra of Sn and tungsten in the catalysts were investigated (Figure 3). The Sn 3d spectrum was deconvoluted into two characteristic peaks at approximately 487.48 and 495.78 eV, which were attributed to Sn 3d5/2 and Sn 3d3/2 (Sánchez et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Qiu et al., 2020) (Figure 3A), respectively, indicating the generation of Sn (IV) species with Lewis acidity. The Sn loading decreased, i.e., Sn 3d3/2 was decomposed into two peaks located at 493.38 and 495.98 eV, respectively, demonstrating the presence of a small amount of Sn (II) oxide in the sample. According to the literature for magnetite (Qiu et al., 2018), the main peaks at 36.18 and 38.28 eV shown in the W 4f spectrum corresponded to W 4f7/2 and W 4f5/2 (Figure 3B). The binding energies of W 4f7/2 and W 4f5/2 in Sn0.1PW and Sn0.75PW showed a blueshift and slight decrease, respectively, and were weaker than that of pure HPW likely due to the interaction of the metal ion Snn+ (n = 2,4) with the anionic Keggin structural unit (Zhao et al., 2015). According to the literature (Choudhary et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2015), for the isomerization of glucose to fructose, Lewis and Brønsted acids have different functions in the conversion of glucose to HMF (Scheme 1). Lewis acids induce glucose isomerization to fructose, and then fructose loses three molecules of water to form HMF using Brønstedacids (Cai et al., 2013; Cai et al., 2014). The Hammett acid strength range of the acid sites is shown in Table 1. The acidic strength of SnxPW was between −1.63 and −0.54, which was lower than that of pure HPW. The catalytic acid strength decreased in the order HPW > Sn0.1PW > Sn0.2PW > Sn0.3PW > Sn0.4PW > Sn0.5PW > Sn0.75PW. The results of Py-FTIR spectroscopy used to analyze the surface acidic sites of the catalyst are shown in Figure 4. Two characteristic absorption bands of strong Lewis and Brønsted acid sites could be observed at 1,452 and 1,537 cm−1. In addition, the characteristic absorption band at 1,488 cm−1 was associated with both Brønsted and Lewis acid sites. The size of the peak areas corresponding to the characteristic absorption bands of Brønsted and Lewis acids indicates the abundance of Brønsted and Lewis acid sites, and the ratio of these sites was calculated based on their peak areas at the corresponding absorption bands. HPW provided dominant Brønsted acid sites, and the introduction of Sn changed the proportion of Brønsted and Lewis acids on the catalyst. Based on the peak intensities at 1,537 and 1,452 cm−1, the concentration of Brønsted acid sites decreased, and the concentration of Lewis acid sites increased with an increasing Sn loading. Shi et al. (2012) also reported that HPW had higher Brønsted acidity than phosphotungstates with Keggin structure.

FIGURE 3. XPS spectra of (A) Sn 3d of Sn0.1PW and Sn0.75PW; and (B) W 4f of HPW, Sn0.1PW, and Sn0.75PW.

As shown in Table 1, the pure HPW presented a 23.52% yield and 25.71% selectivity to HMF. The highest HMF yield (54.12%) and highest starch selectivity (59.77%) were obtained with Sn0.1PW. These results indicate that the efficiency of the catalytic dehydration of glucose to HMF was relatively low in the presence of only a Brønsted acid and without the assistance of a Lewis acid. Thus, the Lewis acid sites assigned by Sn were important for the dehydration of glucose to HMF. The HMF yield decreased from 54.12 to 31.90% as the Sn ion loading increased from 0.41% (Sn0.1PW) to 3.01% (Sn0.75PW). These results indicate that the catalytic activity was related to the number of Brønsted and Lewis acids. The stronger Brønsted acid was more conducive to the hydrolysis of α-1,4-glycosidic bonds and α-1,6-glycosidic bonds in starch. The Lewis acid was more favorable for the conversion of glucose to HMF. Therefore, Sn0.1PW, which presented the strongest protonic acid site, showed the best catalytic activity for the hydrolysis of starch and further conversion to HMF. Therefore, Sn0.1PW was used in the following conversion experiments.

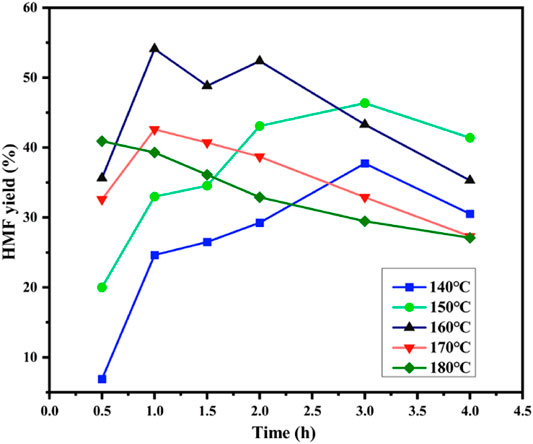

The effect of the reaction temperature and time on the starch conversion to HMF were evaluated, as shown in Figure 5. Both reaction temperature and time affected the yield of HMF. At different temperatures, from 140 to 180°C, the HMF yield first increased to the maximum value and then decreased with an increase in reaction time. At 170 and 180°C, the HMF yield reached its maximum values (42.6 and 40.93%, respectively) at 1 and 0.5 h, respectively. The results showed that with an increase in reaction temperature, the conversion rate of starch to HMF increased, and the time for the HMF yield to reach its maximum at this temperature shortened. The higher reaction temperatures (170 and 180°C) and longer reaction times led to a decrease in the HMF yield. The reason for this phenomenon might be that the probability of side reactions increased with the reaction time at high temperatures, which led to the generation of soluble polymers and insoluble humin (Huang et al., 2018). At 160°C, the maximum HMF yield reached 54.12%, and the starch conversion and HMF selectivity were 90.61 and 59.77% for 1 h (Supplementary Figure S3). With an increase in reaction time, the yield tended to decrease. The yield of HMF was 35.30% when the reaction time was 4 h at 160°C. At low reaction temperatures (140°C), the optimal HMF yield was as high as 37.74%, with a 3.5% fructose yield and a 15.83% glucose yield after 3 h (Supplementary Figure S2A,B). As shown in Supplementary Figure S2B, longer reaction times resulted in the generation of more by-products, such as LA and FA, whose amount, however, was very small, 3.56 and 1.43% at 140°C after 4 h, respectively.

FIGURE 5. Effect of reaction temperature on starch conversion and HMF selectivity [0.2 g of starch and 0.5 mmol/gstarch of Sn0.1PW were dissolved in a mixture of 5 ml saturated NaCl solution and 15 ml organic solvent (THF/DMSO = 7/3, V/V)].

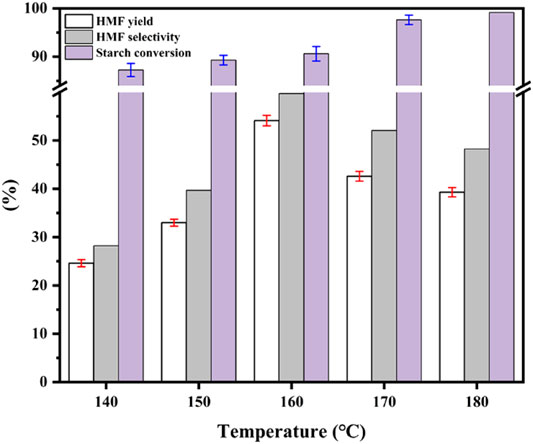

Figure 6 shows the effects of reaction temperature on starch conversion, HMF selectivity, and HMF yield at the same reaction time (1 h). At 140, 150, 160, 170, and 180°C, the starch conversion rate was 87.25, 89.30, 90.61, 97.63, and 99.14%, but the HMF selectivity was 28.21, 39.69, 59.73, 52.08, and 48.25%, respectively, which indicated that starch hydrolysis was conducive to the production of glucose within a certain temperature range. However, higher temperatures (>160°C) caused significant side reactions, leading to the reduction of HMF selectivity (yield; Guo et al., 2012; Qu et al., 2012). Therefore, the optimal reaction conditions for Sn0.1PW to catalyze the conversion of starch to HMF were 160°C with a reaction time of 1 h.

FIGURE 6. Effect of reaction temperature on starch conversion and HMF selectivity [0.2 g of starch and 0.5 mmol/gstarch of Sn0.1PW were dissolved in a mixture of 5 ml saturated NaCl solution and 15 ml organic solvent (THF/DMSO = 7/3, V/V) for 60 min].

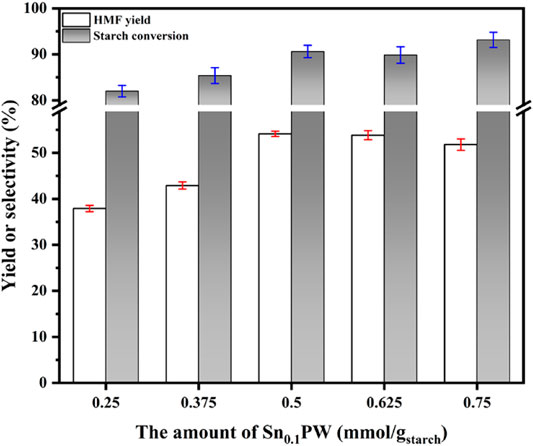

Figure 7 shows the effect of Sn0.1PW dosage on the conversion of starch to HMF (160°C, 1 h). The HMF yield increased remarkably, from 37.90 to 54.12%, when the catalyst dosage increased from 0.25 to 0.50 mmol/g (based on the starch weight). However, the yield decreased slightly as the amount of catalyst was further increased. The maximum HMF yield (54.12%) was obtained for 0.50 mmol/gstarch. The effects of catalyst amount on the yield of glucose, fructose, and by-products were also investigated. With an increase in the catalyst dosage, the content of glucose and fructose in the solvent decreased gradually, while the content of LA and FA gradually increased (Supplementary Figure S4). A possible reason for this pattern was that while the conversion of starch to HMF was accelerated by the increase in catalyst loading, other side reactions, such as HMF reactions with water to synthesize LA and FA or cross-polymerization to form soluble polymers and insoluble humus, were also promoted (Xiao et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2017).

FIGURE 7. Effect of catalyst amount on HMF yield [0.5 mmol/gstarch of Sn0.1PW were dissolved in a mixture of 5 ml saturated NaCl solution and 15 ml organic solvent (THF/DMSO = 7/3, V/V) at 160°C for 60 min].

Based on the properties and experimental studies of SnxPW, a possible catalytic mechanism is proposed (Peng et al., 2019), which primarily can be divided into three steps, as shown in Scheme 2: first, starch molecules are hydrolyzed under acidic conditions to break the glycosidic bond and produce glucose; second, glucose is isomerized to fructose; finally, the fructose molecules undergo a dehydration reaction and shed three water molecules to form HMF. In the second process, Snn + electrophilically attacks glucose molecules and acts on the oxygen atom of the aldehyde group to form an intermediate, which then isomerizes to fructose. Under the Brønsted acid sites on the surface of the catalyst, hydroxyl groups of fructose molecules are eliminated and three molecules of water are removed to form HMF. The preparation of HMF from starch must meet the requirements of acid type and the concentration ratio of Lewis and Brønsted acid sites in the three processes for efficient catalytic hydrolysis isomerization dehydration. The concentration ratio of Brønsted and Lewis acid sites must be controlled accurately to achieve the highest yield of HMF from starch. This discovery provides the possibility for bifunctional catalysts containing Brønsted and Lewis acids to be used as efficient catalysts for biomass conversion to HMF.

It is feasible for modern biorefineries to develop economic and effective catalysts to achieve a high yield and selectivity of HMF from biomass rich in hexose. In this work, a series of acid-base bifunctional SnxPW (x = 0.10, 0.20, 0.30, 0.40, 0.50, 0.60, and 0.75) catalysts were prepared, characterized, and tested for the conversion of starch to HMF. This type of catalyst is easy to prepare, and the concentration ratio of Brønsted and Lewis acids can be easily controlled by controlling the amount of SnCl4. The exchange of Snn+ (n = 2,4) in HPAs could lead to a deep modification of its properties. Among the prepared catalysts, Sn0.1PW exhibited the highest activity (90.61% starch conversion, 59.77% HMF selectivity, and 54.12% HMF yield). The combination of Brønsted and Lewis acid sites was more beneficial than pure HPW to the formation of HMF. This work helps to clarify the characteristics of the HPA-catalyzed conversion of starch to HMF and develop an HPA-based catalyst to efficiently convert renewable biomass into valuable chemicals. Certainly, the development of high activity catalysts and methods for the economic and effective separation and purification of products is key to the industrial production of HMF. Considering the existing problems, the following aspects will become research hotspots in the future: 1) designing efficient green catalysts to optimize the activity, selectivity, stability, and reusability of catalysts; 2) developing new functional green solvents, focusing on the combination of different green and functional solvents, and studying the coupling law of solvents and catalysts; and 3) developing a high-efficiency separation technology for HMF to realize its high-efficiency separation from solvent/catalyst systems.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

YY, JH, and JZ contributed to the conception and design of the study; JH and SJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript; XS and WM wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and read and approved the submitted version.

The authors express their gratitude for the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21968006).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenrg.2021.679709/full#supplementary-material

Akien, G. R., Qi, L., and Horváth, I. T. (2012). Molecular Mapping of the Acid Catalysed Dehydration of Fructose. Chem. Commun. 48, 5850–5852. doi:10.1039/C2CC31689G

Binder, J. B., and Raines, R. T. (2009). Simple Chemical Transformation of Lignocellulosic Biomass into Furans for Fuels and Chemicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 1979–1985. doi:10.1021/ja808537j

Brei, V. V. (2003). Correlation between the Hammett Acid Constants of Oxides and Their Activity in the Dealkylation of Cumene. Theor. Exp. Chem. 39, 70–73. doi:10.1023/a:1022910513589

Cai, C. M., Nagane, N., Kumar, R., and Wyman, C. E. (2014). Coupling Metal Halides with a Co-solvent to Produce Furfural and 5-HMF at High Yields Directly from Lignocellulosic Biomass as an Integrated Biofuels Strategy. Green. Chem. 16, 3819–3829. doi:10.1039/c4gc00747f

Cai, C. M., Zhang, T., Kumar, R., and Wyman, C. E. (2013). THF Co-solvent Enhances Hydrocarbon Fuel Precursor Yields from Lignocellulosic Biomass. Green. Chem. 15, 3140–3145. doi:10.1039/C3GC41214H

Carniti, P., Gervasini, A., and Marzo, M. (2011). Absence of Expected Side-Reactions in the Dehydration Reaction of Fructose to HMF in Water over Niobic Acid Catalyst. Catal. Commun. 12, 1122–1126. doi:10.1016/j.catcom.2011.03.025

Chheda, J. N., Román-Leshkov, Y., and Dumesic, J. A. (2007). Production of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and Furfural by Dehydration of Biomass-Derived Mono- and Poly-Saccharides. Green. Chem. 9, 342–350. doi:10.1039/B611568C

Choudhary, V., Mushrif, S. H., Ho, C., Anderko, A., Nikolakis, V., Marinkovic, N. S., et al. (2013). Insights into the Interplay of Lewis and Brønsted Acid Catalysts in Glucose and Fructose Conversion to 5-(Hydroxymethyl)furfural and Levulinic Acid in Aqueous Media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (10), 3997–4006. doi:10.1021/ja3122763

Chun, J.-A., Lee, J.-W., Yi, Y.-B., Hong, S.-S., and Chung, C.-H. (2010). Direct Conversion of Starch to Hydroxymethylfurfural in the Presence of an Ionic Liquid with Metal Chloride. Starch/Stärke 62, 326–330. doi:10.1002/star.201000012

Deng, T., Cui, X., Qi, Y., Wang, Y., Hou, X., and Zhu, Y. (2012). Conversion of Carbohydrates into 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Catalyzed by ZnCl2 in Water. Chem. Commun. 48, 5494–5496. doi:10.1039/C2CC00122E

Fang, J., Zheng, W., Liu, K., Li, H., and Li, C. (2020). Molecular Design and Experimental Study on the Synergistic Catalysis of Cellulose into 5-hydroxymethylfurfural with Brønsted-Lewis Acidic Ionic Liquids. Chem. Eng. J. 385, 123796. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2019.123796

Guo, X., Cao, Q., Jiang, Y., Guan, J., Wang, X., and Mu, X. (2012). Selective Dehydration of Fructose to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Catalyzed by Mesoporous SBA-15-So3h in Ionic Liquid BmimCl. Carbohydr. Res. 351, 35–41. doi:10.1016/j.carres.2012.01.003

Hornung, P. S., de Oliveira, C. S., Lazzarotto, M., da Silveira Lazzarotto, S. R., and Schnitzler, E. (2016). Investigation of the Photo-Oxidation of Cassava Starch Granules. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 123, 2129–2137. doi:10.1007/s10973-015-4706-x

Hu, S., Zhang, Z., Song, J., Zhou, Y., and Han, B. (2009). Efficient Conversion of Glucose into 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Catalyzed by a Common Lewis Acid SnCl4 in an Ionic Liquid. Green. Chem. 11, 1746–1749. doi:10.1039/b914601f

Huang, F., Su, Y., Tao, Y., Sun, W., and Wang, W. (2018). Preparation of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural from Glucose Catalyzed by Silica-Supported Phosphotungstic Acid Heterogeneous Catalyst. Fuel 226, 417–422. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2018.03.193

Huang, Y.-B., Chen, M.-Y., Yan, L., Guo, Q.-X., and Fu, Y. (2014). Nickel-Tungsten Carbide Catalysts for the Production of 2,5-Dimethylfuran from Biomass-Derived Molecules. ChemSusChem. 7, 1068–1072. doi:10.1002/cssc.201301356

Kondamudi, K., Elavarasan, P., Dyson, P. J., and Upadhyayula, S. (2010). Alkylation of P-Cresol with Tert-Butyl Alcohol Using Benign Bronsted Acidic Ionic Liquid Catalyst. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 321, 34–41. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2010.01.016

Liu, X., Liu, X., Wang, H., Xiao, T., Zhang, Y., and Ma, L. (2020). A Mechanism Study on the Efficient Conversion of Cellulose to Acetol over Sn-Co Catalysts with Low Sn Content. Green. Chem. 22, 6579–6587. doi:10.1039/D0GC02345K

Marcio Jose Da, S., and Cesar Macedo De, O. (2018). Catalysis by Keggin Heteropolyacid Salts. Curr. Catal. 7, 26–34. doi:10.2174/2211544707666171219161414

Mascal, M., and Nikitin, E. B. (2008). Direct, High-Yield Conversion of Cellulose into Biofuel. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 7924–7926. doi:10.1002/anie.200801594

Nie, Y., Hou, Q., Bai, C., Qian, H., Bai, X., and Ju, M. (2020). Transformation of Carbohydrates to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural with High Efficiency by Tandem Catalysis. J. Clean. Prod. 274, 123023. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123023

Nikolla, E., Román-Leshkov, Y., Moliner, M., and Davis, M. E. (2011). "One-Pot" Synthesis of 5-(Hydroxymethyl)furfural from Carbohydrates Using Tin-Beta Zeolite. ACS Catal. 1, 408–410. doi:10.1021/cs2000544

Okuhara, T., Watanabe, H., Nishimura, T., Inumaru, K., and Misono, M. (2000). Microstructure of Cesium Hydrogen Salts of 12-Tungstophosphoric Acid Relevant to Novel Acid Catalysis†. Chem. Mater. 12, 2230–2238. doi:10.1021/cm9907561

Parveen, F., Patra, T., and Upadhyayula, S. (2016). Hydrolysis of Microcrystalline Cellulose Using Functionalized Bronsted Acidic Ionic Liquids - A Comparative Study. Carbohydr. Polym. 135, 280–284. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.08.039

Peng, Y., Li, X., Gao, T., Li, T., and Yang, W. (2019). Preparation of 5-Methylfurfural from Starch in One Step by Iodide Mediated Metal-free Hydrogenolysis. Green. Chem. 21, 4169–4177. doi:10.1039/C9GC01645G

Perea-Moreno, M.-A., Samerón-Manzano, E., and Perea-Moreno, A.-J. (2019). Biomass as Renewable Energy: Worldwide Research Trends. Sustainability 11, 863. doi:10.3390/su11030863

Pumrod, S., Kaewchada, A., Roddecha, S., and Jaree, A. (2020). 5-HMF Production from Glucose Using Ion Exchange Resin and Alumina as a Dual Catalyst in a Biphasic System. RSC Adv. 10, 9492–9498. doi:10.1039/C9RA09997B

Qiu, G., Chen, B., Huang, C., Liu, N., and Sun, X. (2020). Tin-Modified Ionic Liquid Polymer: A Novel and Efficient Catalyst for Synthesis of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural from Glucose. Fuel 268, 117136. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117136

Qiu, G., Wang, X., Huang, C., Li, Y., and Chen, B. (2018). Niobium Phosphotungstates: Excellent Solid Acid Catalysts for the Dehydration of Fructose to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural under Mild Conditions. RSC Adv. 8, 32423–32433. doi:10.1039/C8RA05940C

Qu, Y., Huang, C., Song, Y., Zhang, J., and Chen, B. (2012). Efficient Dehydration of Glucose to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural Catalyzed by the Ionic Liquid,1-Hydroxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate. Bioresour. Tech. 121, 462–466. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.06.081

Rafiee, E., Shahbazi, F., Joshaghani, M., and Tork, F. (2005). The Silica Supported H3PW12O40 (A Heteropoly Acid) as an Efficient and Reusable Catalyst for a One-Pot Synthesis of β-acetamido Ketones by Dakin-West Reaction. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 242, 129–134. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2005.08.005

Ren, Y., Liu, B., Zhang, Z., and Lin, J. (2015). Silver-exchanged Heteropolyacid Catalyst (Ag 1 H 2 PW): An Efficient Heterogeneous Catalyst for the Synthesis of 5-ethoxymethylfurfural from 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and Fructose. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 21, 1127–1131. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2014.05.024

Sánchez, M. A., Vicerich, M. A., Mazzieri, V. A., Gioria, E., Gutierrez, L. B., and Pieck, C. L. (2019). Deactivation Study of Ru‐Sn‐B/Al 2 O 3 Catalysts during Selective Hydrogenation of Methyl Oleate to Fatty Alcohol. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 97, 2333–2339. doi:10.1002/cjce.23444

Shi, W., Zhao, J., Yuan, X., Wang, S., Wang, X., and Huo, M. (2012). Effects of Brønsted and Lewis Acidities on Catalytic Activity of Heteropolyacids in Transesterification and Esterification Reactions. Chem. Eng. Technol. 35, 347–352. doi:10.1002/ceat.201100206

Su, Y., Brown, H. M., Huang, X., Zhou, X.-D., Amonette, J. E., and Zhang, Z. C. (2009). Single-step Conversion of Cellulose to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), a Versatile Platform Chemical. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 361, 117–122. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2009.04.002

Tang, J., Guo, X., Zhu, L., and Hu, C. (2015). Mechanistic Study of Glucose-To-Fructose Isomerization in Water Catalyzed by [Al(OH)2(aq)]+. ACS Catal. 5, 5097–5103. doi:10.1021/acscatal.5b01237

Wang, G.-H., Hilgert, J., Richter, F. H., Wang, F., Bongard, H.-J., Spliethoff, B., et al. (2014). Platinum-cobalt Bimetallic Nanoparticles in Hollow Carbon Nanospheres for Hydrogenolysis of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Nat. Mater 13, 293–300. doi:10.1038/nmat3872

Wu, Y., Yang, Z., Qi, W., Su, R., and He, Z. (2018). Conversion from Carbohydrate to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural via the Fenton Reaction. Chem. industry Eng. 35, 15–21. doi:10.13353/j.issn.1004.9533.20161095

Xiao, S., Liu, B., Wang, Y., Fang, Z., and Zhang, Z. (2014). Efficient Conversion of Cellulose into Biofuel Precursor 5-hydroxymethylfurfural in Dimethyl Sulfoxide-Ionic Liquid Mixtures. Bioresour. Tech. 151, 361–366. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2013.10.095

Xin, H., Zhang, T., Li, W., Su, M., Li, S., Shao, Q., et al. (2017). Dehydration of Glucose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and 5-ethoxymethylfurfural by Combining Lewis and Brønsted Acid. RSC Adv. 7, 41546–41551. doi:10.1039/C7RA07684C

Yu, S.-B., Zang, H.-J., Yang, X.-L., Zhang, M.-C., Xie, R.-R., and Yu, P.-F. (2017). Highly Efficient Preparation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural from Sucrose Using Ionic Liquids and Heteropolyacid Catalysts in Dimethyl Sulfoxide-Water Mixed Solvent. Chin. Chem. Lett. 28, 1479–1484. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2017.02.016

Zhao, P., Cui, H., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., et al. (2018). Synergetic Effect of Brønsted/Lewis Acid Sites and Water on the Catalytic Dehydration of Glucose to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural by Heteropolyacid-Based Ionic Hybrids. ChemistryOpen 7, 824–832. doi:10.1002/open.201800138

Zhao, Q., Wang, L., Zhao, S., Wang, X., and Wang, S. (2011). High Selective Production of 5-Hydroymethylfurfural from Fructose by a Solid Heteropolyacid Catalyst. Fuel 90, 2289–2293. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2011.02.022

Keywords: starch, heteropoly, phosphotungstate, catalytic reaction, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural

Citation: Hao J, Song X, Jia S, Mao W, Yan Y and Zhou J (2021) Catalytic Conversion of Starch to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural by Tin Phosphotungstate. Front. Energy Res. 9:679709. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2021.679709

Received: 12 March 2021; Accepted: 12 May 2021;

Published: 28 May 2021.

Edited by:

Cameron M. Moore, Los Alamos National Laboratory (DOE), United StatesReviewed by:

Jacob Kruger, National Renewable Energy Laboratory (DOE), United StatesCopyright © 2021 Hao, Song, Jia, Mao, Yan and Zhou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuxiao Yan, eWFueXgxOTcwQDEyNi5jb20=; Jinghong Zhou, amh6aG91ZG91QGd4dS5kZXUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.