- Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute, Daejeon, South Korea

Micro-plate or microcell UO2–Mo is considered a promising accident tolerant fuel candidate for water-cooled power reactors. In this work, we evaluated the anticipated oxidation behavior of a UO2–Mo system under high-temperature steam to understand the impact of Mo oxidation on the fuel degradation mechanism in the event of steam ingress through cracks in the cladding. The equilibrium oxygen compositions of UO2 and Mo in various steam atmospheres relevant to reactor operating conditions were predicted using thermodynamic calculations and then compared with previous results. The oxidation behavior of UO2–Mo pellets was discussed through thermodynamic calculations and in terms of kinetic parameters such as oxygen diffusion, fuel temperature profile, and pellet microstructure. Mo oxidation was found to have an insignificant effect on pellet integrity in a cladding leakage scenario under normal reactor operating conditions.

Introduction

UO2–Mo micro-plate or microcell pellets, in which small amounts of molybdenum metal particles are arranged in the form of directionally aligned plates or continuous networks, are actively studied worldwide as a promising accident tolerant fuel candidate for light water reactors, because they have improved thermal conductivity (Kim et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2018; Buckley et al., 2019; Cheng et al., 2019; Finkeldei et al., 2019; Cheng et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020). This fuel design might be easily implemented in nuclear power plants in the near term, as it inherits the superior safety performance of UO2 nuclear fuel and can leverage existing knowledge and infrastructure.

To successfully implement the micro-plate or microcell concepts in a UO2 pellet, research is underway on addressing various technical issues. A conventional pressure-less sintering process has been established to produce composite pellets with a specific microstructure (Kim et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2018). From an economic perspective, the fuel cycle length in a UO2–Mo system is reduced because the addition of Mo reduces U loading, and Mo has a larger neutron absorption cross-section. The neutron penalty is partly mitigated by limiting the Mo addition to less than 3 vol%. The lower fuel operating temperature owing to the improved thermal conductivity is conducive to neutron utilization owing to the MTC feedback effect (Jo et al., 2020). Preliminary calculation showed that UO2–3vol% Mo fuel with a U235 enrichment of 4.95% can achieve the same fuel cycle length as that in a 4.65% enriched UO2 fuel.

Phase equilibria serve as a basis for the manufacturing and performance characterization of nuclear fuels. In particular, a comprehensive understanding of phase equilibrium and thermochemical properties is essential to support licensing by providing data on changes in the thermophysical properties, irradiation damage, and behavior of fission products. Chemical reactions between fuel materials and the atmosphere can result in fuel degradation and is one of the main factors governing nuclear fuel performance. During irradiation in a nuclear reactor, fuel pellets can be in two states where the partial pressure of oxygen in the environmental gas increases. The first state is during normal operation. The oxygen separated from UO2 by the fission of U increases the oxygen potential of the atmosphere in the fuel rod (Spino and Peerani, 2008). Another state is the ingress of steam through a damaged fuel cladding. The coolant flows into the hot fuel rod and vaporizes, and the steam is decomposed to generate oxygen, which increases the oxygen partial pressure inside the fuel rod. Thermodynamically, Mo has a high oxygen affinity and can undergo oxidization and evaporation when exposed to a high-temperature atmosphere containing oxygen. If UO2–Mo pellets are oxidized in a leakage scenario (e.g., cladding breach), the oxidation and evaporation of Mo and the resulting volume expansion of the fuel pellets may cause fuel rod failure and exacerbate the accident.

The aim of this study was to evaluate thermodynamically the change in the equilibrium oxygen composition of UO2–Mo pellets when exposed to high-temperature steam. The impact of Mo oxidation on the degradation behavior of UO2 pellets in the event of a cladding breach is also discussed. Our preliminary assessments are expected to contribute to the evaluation of this material for use as an accident-tolerant fuel.

Calculation of Oxygen Partial Pressure in Steam Gas Under Various Conditions

In fuel rod failure scenarios, UO2 pellets are exposed to steam at high temperatures and high pressures. In this environment, UO2 pellets oxidize to a composition that is in equilibrium with the gas phase. To calculate the equilibrium deviation from the stoichiometry of UO2, it is necessary to know the partial pressure of oxygen in the environment. The oxygen partial pressure of the gas is determined by the temperature, gas composition, and pressure. Under normal operating conditions, the fuel temperature is typically in the range of 400–1,300°C. The internal pressure of the damaged fuel rod is equivalent to a typical reactor operating pressure of 150 atm. Regarding the composition of the gas introduced into the rod, the steam is mixed with hydrogen produced during the oxidation reaction of steam with Zr (Garzarolli and Stehle, 1979; Review of Fu, 2010). Previous studies reported that the highest deviation from the stoichiometry (x in UO2+x) for the pellets in the damaged fuel rods is approximately 0.1 (Une et al., 1995; Kim, 2003; Verrall et al., 2005; Higgs et al., 2007). This deviation implies that some amount of hydrogen is mixed in the introduced steam and that the hydrogen composition varies depending on the location in the fuel rod. Considering the typical operating conditions and anticipated steam compositions, the equilibrium oxygen partial pressure with respect to the temperature was calculated under different hydrogen contents of the mixed steam gas (0, 10, and 1,000 ppm).

Two calculation procedures were applied to obtain the equilibrium oxygen partial pressures in this study: 1) The Gem module from HSC Chemistry 9 (HSC Chemistry 9, 2018), which utilizes the built-in Gibbs energy minimization method, and 2) Olander’s transcendental equation (Olander, 1986). According to the Olander’s transcendental equation, the oxygen partial pressure (

where,

R is the universal gas constant (8.3145 J/mol·K), and

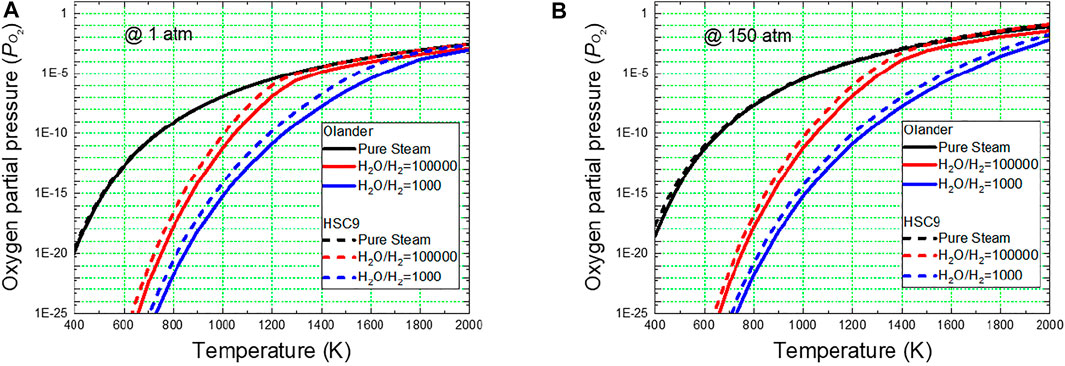

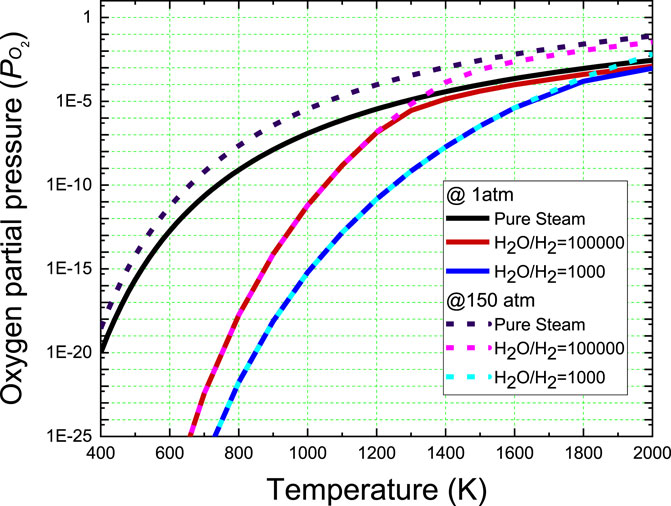

Figure 1 shows the calculated variation in the oxygen partial pressures as a function of temperature for steam and steam–hydrogen mixtures at 1 and 150 atms. For pure steam, the oxygen partial pressure calculated by Olander’s formula agrees well with that obtained using the HSC9 program. However, for the steam–hydrogen mixture, the oxygen partial pressures obtained from Olander’s solution were slightly lower. Many previous studies have used Olander’s equation to evaluate the equilibrium oxygen partial pressure of steam–hydrogen mixed gases. In this study, Olander’s solution was used to estimate the equilibrium oxygen composition to ensure consistency with previous results.

FIGURE 1. Comparison of equilibrium oxygen partial pressures of steam and steam–hydrogen mixed gases as a function of temperature for total pressures of (A) 1 atm and (B) 150 atm, calculated through the HSC9 program (HSC Chemistry 9, 2018) and Olander’s equation (Olander, 1986).

Figure 2 shows the equilibrium oxygen partial pressures of the mixed steam as a function of temperature at pressures of 1 and 150 atm obtained by Olander’s solution. The mixing of a small amount of hydrogen significantly reduces the equilibrium oxygen partial pressure of the steam. However, as the temperature increases, the oxygen partial pressure difference between the pure steam and the mixture gradually narrows because of the decomposition reaction of the steam. Evidently, in pure steam, the oxygen partial pressure increases with increasing pressure in the calculated temperature range. In the case of the mixed gas, the pressure has little effect in the low-temperature region. Above a certain temperature, however, the oxygen concentration increases because of the decomposition reaction of the steam, thereby increasing the oxygen partial pressure at high pressures.

FIGURE 2. Effects of H2 mixing and pressure on the equilibrium oxygen partial pressures of steam calculated by Olander’s equation (Olander, 1986).

Evaluation of Equilibrium Oxygen Compositions of UO2 and Mo at High Temperature Steam and Steam-Hydrogen Mixtures

The equilibrium oxygen composition of U–O and Mo–O systems can be estimated using the oxygen partial pressures of the environment and p-C-T (

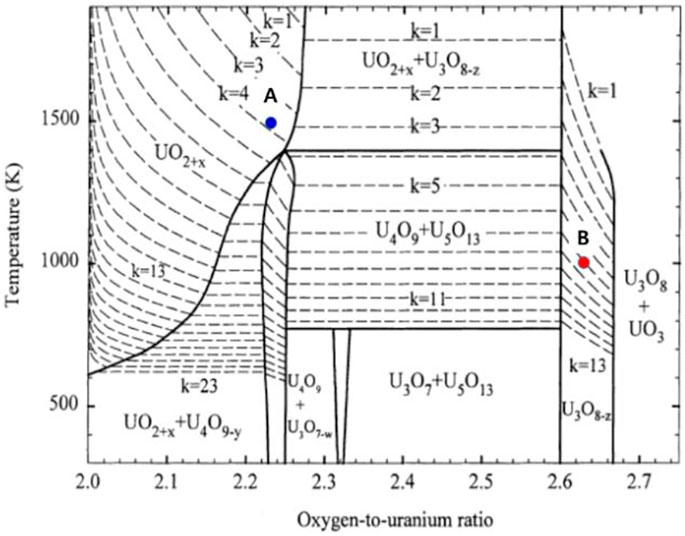

FIGURE 3. Variation in the equilibrium oxygen stoichiometry with temperature of the U–O system in pure steam atmosphere. The points A (blue dot) and B (red dot) indicate the equilibrium oxygen partial pressures of pure steam at 1500 and 1000 K, respectively. The U–O phase diagram is from Ref. (Kim, 2000).

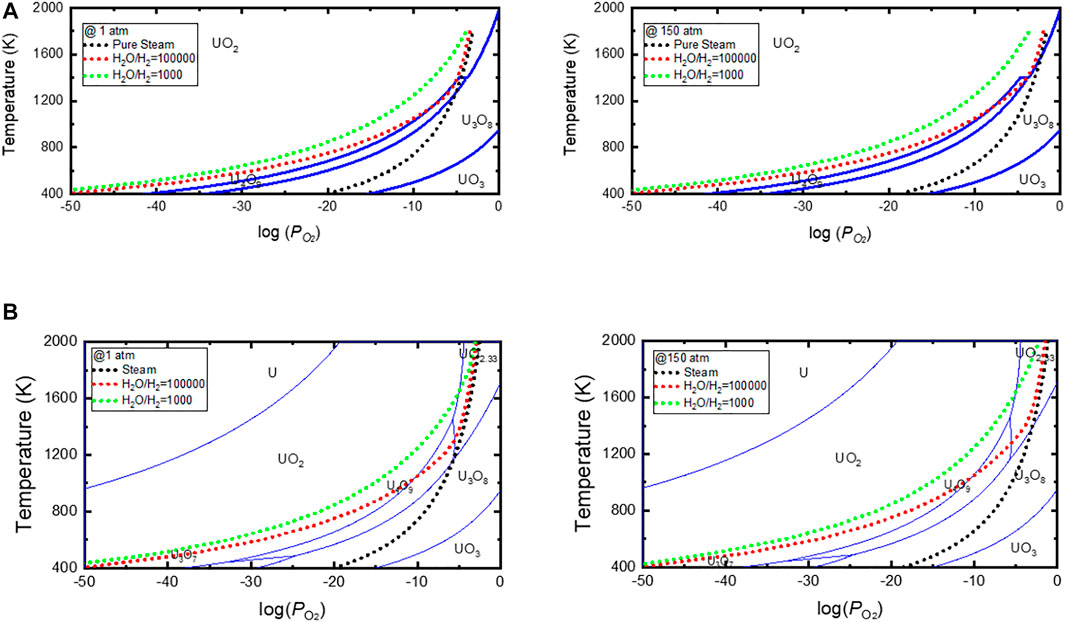

Figures 4A,B show the phase stability diagrams of the U–O system constructed using thermodynamic equations established by Kim and Tpp module in HSC9 Chemistry, respectively. The equilibrium oxygen potential curves for the pure steam and steam–hydrogen mixtures in this study are also shown. From Figure 4, we can predict the oxidation behavior of UO2 with temperature changes when UO2 is exposed to high-temperature steam. As shown in Figure 4A, when UO2 pellets are exposed to pure steam at a pressure of 150 atm and a temperature above 1573 K, there is no significant change in the pellet shape owing to the stable cubic phase of UO2+x. However, when the temperature decreases below 1573 K, the orthorhombic phase of U3O8 becomes stable, and UO2 pellets pulverize to U3O8−x powder. Figure 4A also reveals that reducing the pressure or mixing a small amount of hydrogen in the steam can help significantly extend the temperature range in which the cubic phases of UO2+x or U4O9−y are stable. For example, mixing more than 10 ppm of hydrogen in the steam can help prevent UO2 pellets from being oxidized to U3O8. The two stability diagrams shown in Figures 4A,B are similar but not entirely consistent. As shown in the stability diagram of Figure 4B obtained using HSC9, the UO2 pellets pulverize to U3O8 when exposed to steam at a pressure of 150 atm and a temperature below 1373 K. This temperature limit is ∼200 K lower than that shown in Figure 4A.

FIGURE 4. U–O stability diagram and equilibrium oxygen potentials of steam and steam–hydrogen mixed gas. U–O stability boundary is constructed using (A) thermodynamic equations in Ref. (Kim, 2000), and (A)Tpp module in HSC9 Chemistry (HSC Chemistry 9, 2018).

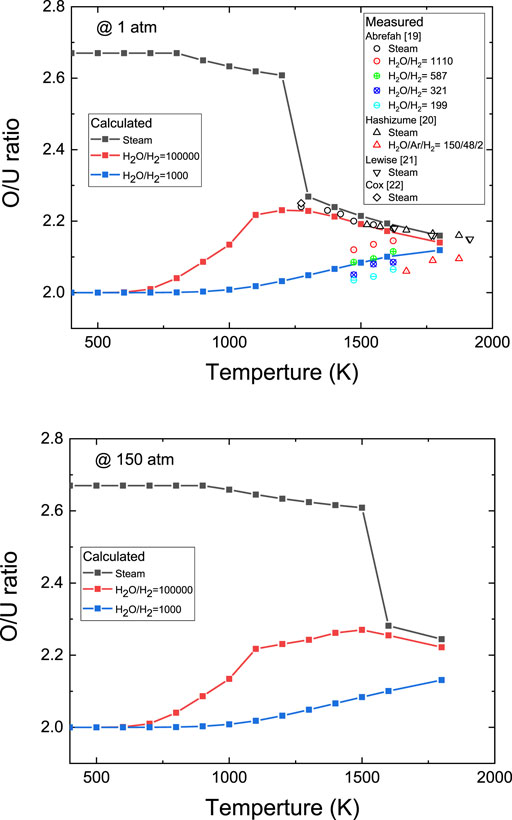

Figure 5 shows detailed variations in the calculated equilibrium O/U ratio of the U–O system with the steam composition, pressure, and temperature. The equilibrium O/U ratio was calculated using the equations presenting the best p-C-T relationship proposed by Kim (Kim, 2000). As expected, in Figure 4A, the O/U ratio of pure steam abruptly changes at the stability boundary temperature between the cubic phases (UO2+x, U4O9−y), and U3O8. When the steam-to-hydrogen ratio (H2O/H2) is 100,000, the cubic phase is stable over the calculated temperature range, and no U3O8 phase is expected. Since the oxygen potential curve of this gas is closest to the stability boundary at approximately 1273 K, the equilibrium O/U ratio shows a parabolic shape with a peak value located in the temperature range of approximately 1,273–1373 K. When the hydrogen content is increased further (H2O/H2 = 1,000), the oxygen potential of the atmosphere is largely reduced, and consequently, the equilibrium O/U ratio decreases. Published experimental data (Abrefah et al., 1994; Hashizume et al., 1999; Lewis et al., 1990; Cox et al., 1986) on O/U ratio variations following UO2 oxidation in steam and steam–hydrogen mixture are compared in Figure 5A. The experimental data measured above 1273 K are in good agreement with the calculated values. While several experimental datasets on the equilibrium O/U ratio exist for steam oxidation of UO2 pellets above 1273 K, few data are available for steam oxidation below 1273 K owing to the slow oxidation of UO2 at low temperatures and the challenges related to controlling the steam–hydrogen composition. Kuhlman (Kuhlman, 1948) found no significant weight change in UO2 after exposure to oxygen-free steam at 873 K for 6 h. Bittel et al. (Bittel et al., 1969) reported that the final average O/U ratio of pellets annealed at 1158 K for 290 min in steam was 2.039, which is far below the calculated value. On the contrary, Dumitrescu et al. (Dumitrescu et al., 2015) reported that UO2 pellets pulverize to U3O8 after annealing in 873 K steam for 10 h. Recently, Jung et al. (Jung et al., 2020) have also shown the formation of U3O8 particles on the UO2 pellet annealed for 1,000 min in steam maintained at a temperature range of 673–733 K. This discrepancy between the experimental results appears to be due to the very slow oxidation reaction in low-temperature steam and the strong influence of the oxygen and hydrogen contents on the equilibrium oxygen potential of the steam.

FIGURE 5. Calculated equilibrium O/U ratio of the U–O system using the equations in Ref (Kim, 2000). and comparison with experimental data.

The melting point of pure molybdenum is 2896 K. However, the formation of low-melting-temperature oxides is the drawback of this refractory metal. The Mo–O temperature–concentration diagram shows various molybdenum oxides, where the principal stable oxide phases in the Mo-O system are MoO3 (

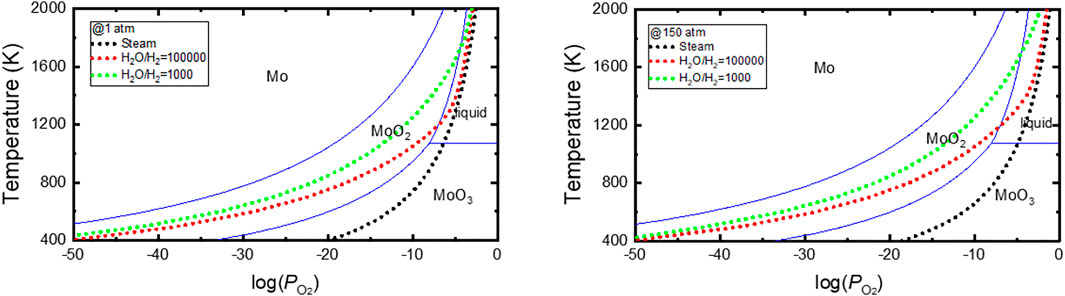

The phase stability diagrams for the Mo–O system with the variations in the temperature and oxygen partial pressure have been presented by several researchers (Chen et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2019a; Zhang et al., 2014). Figure 6 shows the stability diagrams applied in this study, plotted using the Tpp module in HSC9 program (HSC Chemistry 9, 2018). The stability diagram is similar to that prepared by Chen (Chen et al., 2018) using FactSage 6.2 (GTT Technologies, Germany) and that calculated by Lee (Lee et al., 2019a) using meta-generalized-gradient approximation and hybrid density functional theory calculations. Zhang et al. constructed a Mo–O stability diagram using the CALPHAD method (Zhang et al., 2014). However, the stability diagram differs considerably from that shown in Figure 6, characterized by a narrower area of stability for solid oxides.

FIGURE 6. Mo–O stability diagram and equilibrium oxygen potentials of steam and steam–hydrogen mixed gas, constructed using the HSC9 program.

The oxygen partial pressure or equilibrium oxygen potential curves were superimposed on these figures to assess the anticipated equilibrium oxygen composition of the Mo–O system when exposed to atmospheres as those shown in Figure 2. Figure 6 indicates that MoO3 is a stable oxide in pure steam. Therefore, when Mo is exposed to steam, it will oxidize to MoO3, becoming a liquid above 1073 K and vaporizing above 1428 K. Indeed, the oxidation test of Mo in 100% steam showed a rapid weight loss above 1073 K (Nelson et al., 2014). The oxidation behavior of Mo changes significantly even when very small amounts of hydrogen is added to the steam. As shown in Figure 6, in 150 atm steam mixed with 1,000 ppm of hydrogen, the equilibrium oxide composition is MoO2, and a liquid phase is formed at approximately 1673 K, which is approximately 600 K higher than that in the case of pure steam. The effect of hydrogen content in steam on the oxidation of Mo has been determined at 1273 K. The test result shows that the material loss rate can be meaningfully reduced by adding hydrogen to the steam, consistent with the effect of hydrogen predicted and shown in Figure 6 (Nelson et al., 2014).

Prediction of the Oxidation Behavior of UO2-Mo Pellets in the Event of Cladding Breakage During the Normal Operation

The oxidation behavior of UO2 and Mo in various steam atmospheres relevant to reactor operating condition was studied independently. In this section, the oxidation behavior of UO2–Mo pellets is predicted when steam is introduced into the fuel rod through cladding leaks under reactor operating conditions.

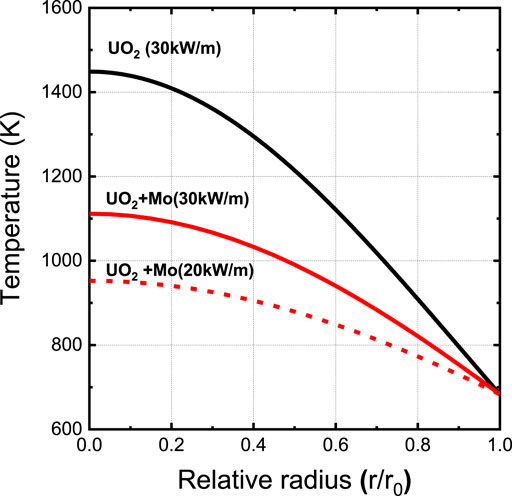

Figure 7 shows a comparison of the calculated temperature profile along the radial direction between conventional UO2 and micro-plate UO2–3vol% Mo pellets operating at a linear heat generation rate of 30 kW/m. The temperature gradient of the UO2 pellets was calculated using the thermal conductivity model from the MATPRO handbook (Hagrman and Reymann, 1979). The temperature profile of UO2- 3vol% Mo pellets was calculated using the measured thermal conductivity of the pellet in which Mo plates with an average diameter of ∼45 μm and an average thickness of ∼1.5 μm were dispersed in UO2 (Kim et al., 2020). The thermal conductivity of both pellets was corrected to 95% of the theoretical density for temperature calculation.

Since the thermal conductivity is more than 80% higher than that of UO2 pellets, the operating temperature is significantly reduced in the case of the UO2–3vol% Mo pellet. The centerline temperature of UO2–3vol% Mo is calculated to be 1093 K, approximately 300 K lower than that of UO2.

As shown in Figure 5, the high-pressure steam ingress into the fuel rod pulverizes the UO2 pellets, and consequently, the fuel rods are severely damaged because of the volume expansion and fission gas release. However, the fuel failure mechanism due to the oxidation of UO2 pellets has not been reported thus far. In fact, the secondary failure mechanisms observed in defective fuel rods were mostly due to the formation of ZrO2 or ZrH2 ((2010). Review of Fu, 2010). As mentioned in Calculation of Oxygen Partial Pressure in Steam Gas Under Various Conditions, this fact reveals that the steam introduced to the fuel rod is mixed with hydrogen and consequently has a much lower oxygen partial pressure than pure steam.

Assuming a constant thermal conductivity of the fuel pellets during the oxidation reaction, the oxidation behavior of UO2–3vol% Mo pellets operating at a 30 kW/m when exposed to 150 atm steam mixed with hydrogen can be predicted as follows. Figures 4, 5 indicate that the equilibrium oxygen composition deviation from stoichiometric UO2 (x in UO2+x) is ∼0.22 and decreases toward the pellet periphery, when the hydrogen content in the steam is 10 ppm. The equilibrium phase of Mo under this condition is MoO2, which has a melting temperature of ∼1193 K, as shown in Figure 6. When the hydrogen content in the steam increases to 1,000 ppm, the maximum deviation of x in UO2+x decreases to less than 0.02, and the melting temperature of MoO2 increases to ∼1673 K. The theoretical densities of Mo, MoO2 and MoO3 are 10.28, 6.47, and 4.69 g/cm3, respectively. The lattice parameters of UO2+x are known to contract linearly with an increase in x, and the contraction factor (line slope) is in the range of −0.132 and −0.07 Å, depending on temperature and x (Perio, 1955; Rachev et al., 1965; Belbeoch et al., 1967; Touzelin and Dode, 1969; Teske et al., 1983; Yakub et al., 2009). Considering the specific situation where only Mo is oxidized to MoO3 in UO2-3vol% Mo pellet, the pellet will show a volume increase of up to 3.6%. However, in that situation, UO2 is also oxidized to UO2+x, so the volume expansion due to MoO3 formation is offset by the volume reduction due to oxidation of UO2. If we assume the oxidation reaction terminated with the formation of solid MoO3 and UO2.15, and the contraction factor is −0.07 Å, the volume of the pellet will be increased by about 3%. When the oxidation reaction with the steam-hydrogen mixture is completed and the pellet reaches an equilibrium state, the pellet volume is expected to increase to less than 3%, considering the volume expansion due to MoO2 formation and volume reduction due to UO2 oxidation. Moreover, no liquid phase is expected in the equilibrium state because the maximum pellet temperature is much lower than the melting temperature of MoO2.

The diffusion mobility of oxygen as well as the kinetic parameters should also be considered in the prediction of the oxidation behavior. Higgs et al. have developed a theoretical model to evaluate the UO2 pellet oxidation behavior in operating defective fuel elements, taking into account multi-phase transport including oxygen diffusion by both chemical and thermal gradients and steam-hydrogen transport along gap and in fuel cracks (Higgs et al., 2007).

Thermoelastic fracture owing to the temperature gradient dominates the formation of primary radial cracks in UO2 pellets under irradiation (Oguma, 1983; Lee et al., 2019b; Li and Shirvan, 2021). The number of cracks measured under various out-of-pile conditions in the UO2 pellet is roughly proportional to linear power of the fuel rod (Oguma, 1983). Multiphysics phase-field modeling of quasi-static cracking in UO2 pellet showed typically eight primary radial cracks are developed and interconnected during the reactor startup and cooling (Li and Shirvan, 2021). In the case of UO2-Mo composite pellet, lower temperature gradient would reduce the thermal hoop stress, thereby decreasing pellet region where the thermal hoop stress is higher than fracture stress of UO2 (Lee et al., 2019b), suggesting the UO2-Mo could be more resistant to cracking than the UO2 pellet even for the same linear power, as was observed in U3Si2 fuel (Cappia and Harp, 2019). However, the composite structure would probably have insignificant effect on cracking behavior because the volume fraction of Mo plates or Mo wall is just 3% and its thickness is only several micrometers. Therefore, the linear power will be a dominant factor in the cracking behavior and, if the temperature gradients between the UO2 and UO2-Mo pellets are the same, the crack patterns observed in both pellets are expected to be similar to each other.

Two assumptions have been made. First, the UO2-3 vol% Mo pellet are fragmented into eight parts by eight primary radial cracks that penetrate the center. Second, considering the average diameter of Mo plates (∼45 μm), the Mo particles located within 50 μm of the fragments surface will be exposed to environment directly. Under the circumstance, it is calculated that about 0.45 vol% of Mo among the 3 vol% of Mo will directly contact with steam transported along the gap and fuel cracks, and the remaining 2.55 vol% of Mo will be embedded in the UO2 matrix.

The oxidation reaction of the Mo plates embedded in the UO2 matrix will be governed by oxygen diffused through UO2 lattice or grain boundaries. Therefore, oxygen diffusion inside the UO2 matrix is an important parameter that needs to be considered to better understand the influence of Mo on oxidation behavior. Considering the diffusion distance for oxygen to reach the Mo surface via the dense UO2 and the low lattice diffusion rate owing to the low pellet temperature of less than 1093 K (Bittel et al., 1969), relatively long incubation time seems to be required for the Mo inside the pellet fragment to meet with oxygen and start the oxidation reaction. The MoO2 layer is known to adhere to the Mo surface and act as an anti-corrosion layer, so the formation of a MoO2 surface layer is expected to further delay the oxidation rate. Therefore, the oxidation reaction rate of Mo by oxygen diffusion is expected to be low, particularly in the outer region of the pellet with low temperature. In contrast to the Mo plate inside the pellet fragment, the Mo plate located near the pellet periphery or fragment surface would be rather quickly oxidized even at low temperature by direct contact with the steam introduced through the cladding defects, gas gaps and fuel cracks. In particular, the volume expansion due to preferential oxidation of Mo possibly develops secondary cracks on the surface, and steam can penetrate through the cracks to accelerate oxidation. However, the rapid oxidation of exposed Mo is expected to be confined to a small number of pellets located around the defect. The experimental and computational results showed that O/U ratio of pellet located at opposite side of or far from the defect is much lower than that of pellet near the defect (Une et al., 1995; Kim, 2003; Verrall et al., 2005; Higgs et al., 2007). The steam-hydrogen transport rate, another important parameter controlling the rate of reaction, is probably limited in the opposite area of the pellet to defect or at a location away from the defect. In particular, the hydrogen concentration increases where the gas transports is stagnant, and then, the local oxidation rate is further delayed.

There was a concern about the accelerated degradation of UO2–Mo fuel rods due to the oxidation of Mo in a cladding leakage scenario. However, a thermodynamic evaluation showed that the equilibrium composition of Mo is the solid phase of MoO2, and the maximum volume expansion of a pellet due to the complete oxidation of Mo to MoO2 is estimated to be less than 3%. Given the low fuel temperature and the microstructure of the pellets, where most of Mo is imbedded in UO2 matrix, and considering UO2 pellet oxidation behavior in operating defective fuel element (Garzarolli and Stehle., 1979; Review of Fu, 2010; Une et al., 1995; Kim, 2003; Verrall et al., 2005; Higgs et al., 2007), it will take a long time for Mo to reach the equilibrium composition of MoO2, and the volume expansion of the pellet will also proceed gradually. Therefore, the effect of Mo oxidation on the pellet integrity in a cladding leakage scenario is expected to be insignificant.

The thermodynamic prediction of the oxidation behavior was evaluated under the assumption that the thermal conductivity of the pellet remains constant and that there are no reactions at the UO2/MoO2 interface. However, the thermal conductivity may decrease depending on the degree of oxidation of UO2 and Mo, and the formation of new compounds has an additional effect on the volume change. Subsequently, the pellet temperature will increase, and the oxidation behavior of the fuel rod may vary. U-Mo-O ternary compounds, which are possibly formed at the UO2/Mo interface, would influence the oxygen transport and thus the oxidation behavior of the pellets. When the thermal conductivity decreased and fuel temperature increased, Mo oxides in the central region of pellet might form liquid or vapor phases. Those phases can negatively affect the integrity of the fuel rods by increasing the fuel internal pressure and reacting with pellet and cladding. Therefore, to accurately assess the fuel behavior, further experimental studies are required to obtain data on the diffusion mobility of oxygen near the phase boundary between UO2 and Mo, reactions at the UO2/Mo and UO2+x/MoO2 interfaces (Bharadwaj et al., 1984; Sarrasin et al., 2019), phase equilibria in U-Mo-O ternary system and the change in the thermal conductivity with the degree of oxidation. Multiple and complex chemical reactions, including cladding and fission products, as well as interactions between UO2-Mo and steam are expected to occur under accidents such as loss of coolant or station black out. Although the volume fraction of Mo in UO2 is small (3%), which is expected to have a limited impact on accident progress, integral test of fuel rod is required to understand the behavior of UO2-Mo pellets and their interactions with cladding in the event of accidents.

Conclusion

The oxidation behavior of a UO2–Mo system in a steam atmosphere relevant to reactor operating conditions was evaluated through thermodynamic calculations for a preliminary assessment of the impact of Mo oxidation on the fuel behavior of UO2–Mo pellets in the event of steam ingress through cracks in the cladding. In the thermodynamic equilibrium state, the oxidation reaction is terminated with the formation of solid MoO2 and hyper-stoichiometric UO2+x, and the volume expansion after the termination of the reaction is estimated to be less than 3%. In terms of the kinetic parameters, such as the steam-hydrogen flow, fuel temperature, and cracked-pellet microstructure, the impact of Mo oxidation on the fuel integrity in a cladding leakage scenario is expected to be insignificant. Limitations of the current preliminary thermodynamic assessment include the thermal conductivity degradation due to the formation of U-Mo-O compounds, steam/hydrogen transports along the fuel cracks and gap, and simplified thermo-mechanical cracking behavior. Future experimental study would include the oxidation behavior of Mo located near fuel crack and inside UO2 under the anticipated oxygen potential, the microstructure change after the mechanical cracks or during the oxidation, and the variation of effective thermal conductivity owing to the formation of Mo-oxides and U-Mo-O compounds. Integral test using fuel and cladding assembly would also be necessary to estimate the effect of steam/hydrogen mixed gas transport in the defective fuel rod and its local composition on the overall oxidation behavior of UO2-Mo-Zr fuel system. Combining the thermodynamic evaluation in this study with experimental data in the future, it will be possible to simulate the behavior of fuel rods in the event of a cladding breach.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

JHY: Conceptualization, Methodology, Calculation, Visulaization, Writing-Original draft, Review and; Editing. KWS: Methodology, Data collection, Review and; Editing. DSK: Methodology, Data collection, Review and; Editing. D-JK: Methodology, Data collection, Review and; Editing. HSL: Methodology, Data collection, Review and; Editing. J-HY: Methodology, Data collection, Review and; Editing. Y-HK: Methodology, Review and; Editing.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation funded by Ministry of Science and ICT of Korea (grant number 2017M2A8A5015056).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Abrefah, J., Aguiar Braid, A. D., Wang, W., Khalil, Y., and Olander, D. R. (1994). High Temperature Oxidation of UO2 in Steam-Hydrogen Mixtures. J. Nucl. Mater. 208, 98–110. doi:10.1016/0022-3115(94)90201-1

Belbeoch, B., Boivineau, J. C., and Perio, P. (1967). Changements de structure de l'oxyde U4O9. J. Phys. Chem. Sol. 28, 1267–1275. doi:10.1016/0022-3697(67)90070-4

Bharadwaj, S. R., Chandrasekharaiah, M. S., and Dharwadkar, S. R. (1984). On the Solid State Synthesis of UMoO6. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 3, 840–842. doi:10.1007/BF00727990

Bittel, J. T., Sjodahl, L. H., and White, J. F. (1969). Steam Oxidation Kinetics and Oxygen Diffusion in UOz at High Temperatures. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 52, 446–451. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1969.tb11976.x

Brewer, L., and Lamoreaux, R. H. (1980). The Mo-O System (Molybdenum-Oxygen). Bull. Alloy Phase Diagrams 1, 85–89. doi:10.1007/bf02881199

Buckley, J., Turner, J. D., and Abram, T. J. (2019). Uranium Dioxide - Molybdenum Composite Fuel Pellets with Enhanced thermal Conductivity Manufactured via Spark Plasma Sintering. J. Nucl. Mater. 523, 360–368. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2019.05.059

Cappia, F., and Harp, J. M. (2019). Postirradiation Examinations of Low Burnup U3Si2 Fuel for Light Water Reactor Applications. J. Nucl. Mater. 518, 62–79. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2019.02.047

Chen, W.-F., Chen, H., Koshy, P., Nakaruk, A., and Sorrell, C. C. (2018). Effect of Doping on the Properties and Photocatalytic Performance of Titania Thin Films on Glass Substrates: Single-Ion Doping with Cobalt or Molybdenum. Mater. Chem. Phys. 205, 334–346. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2017.11.021

Cheng, L., Gao, R., Xu, Q., Yang, Z., Li, F., Li, B., et al. (2020). UO2-Mo-Be Composites for Accident Tolerant Fuel: SPS Fabrication, Microcracks-free in As-Fabricated State and superior thermal Conductivity. Ceramics Int. 46, 28939–28948. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.08.064

Cheng, L., Yan, B., Gao, R., Liu, X., Yang, Z., Li, B., et al. (2019). Densification Behaviour of UO2/Mo Core-Shell Composite Pellets with a Reduced Coefficient of thermal Expansion. Ceram. Int. 46, 4730–4736. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.10

Cox, D. S., Iglesias C, F. C., Atmrand, R. D., In Hunt, J. R., Mitchell, N. A., and O’Connor Proc, R. F.E. L (1986). “Oxidation of UO2 in Air and Steam with Relevance to Fission Product Releases Keller,” in Symposium Chemical Phenomena Associated with Radioactivity Releases During Severe Nuclear Plant Accidents. Anaheim, CA: NUREG/CP-0078, 35–49.

Dumitrescu, I. M., Mihalache, M., Abrudeanu, M., Dumitru, O., and Dinu, A. (2015). Isothermal Oxidation of UO2 Fuel Pellets in Steam. Rev. Chim. (Bucharest) 66, 290–293.

Finkeldei, S. C., Kiggans, J. O., Hunt, R. D., Nelson, A. T., and Terrani, K. A. (2019). Fabrication of UO2-Mo Composite Fuel with Enhanced thermal Conductivity from Sol-Gel Feedstock. J. Nucl. Mater. 520, 56–64. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2019.04.011

Garzarolli, R. H., and Stehle, V. Y. (1979). The Main Causes of Fuel Element Failure in Water-Cooled Power Reactors. At. Energ. Rev. 17, 31–128.

Hagrman, D. L., and Reymann, G. A. (1979). MATPRO, A Handbook of Materials Properties for Use in the Analysis of Light Water Reactor Fuel Rod Behavior. Idaho Falls: NUREG/CR-0497. doi:10.2172/6442256

Hashizume, K., Wang, W.-E., and Olander, D. R. (1999). Volatilization of Urania in Steam at Elevated Temperatures. J. Nucl. Mater. 275, 277–286. doi:10.1016/S0022-3115(99)00123-3

Higgs, J. D., Lewis, B. J., Thompson, W. T., and He, Z. (2007). A Conceptual Model for the Fuel Oxidation of Defective Fuel. J. Nucl. Mater. 366, 99–128. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2006.12.050

HSC Chemistry 9 (2018). Outotec. URLAvailable at: http://www.outotec.com/hsc.

IAEA Nuclear Energy Series (2010). Review of Fuel Failures in Water Cooled Reactor. Vienna: IAEA Nuclear Energy Series No. NF-T-2.1.

Jo, Y., Jeong, E., Cherezov, A., and Lee, D. (2020). Preliminary Neutronic Analysis Results of Accident Tolerant Fuel Loaded OPR-1000 with Stream/RAST-K 2.0 Code. Transactions of the Virtual meeting, KNS.

Jung, T.-S., Soo, N., Min-, J. J., Na, Y.-S., Joo, M.-J., Lim, K.-Y., et al. (2020). Thermodynamic and Experimental Analyses of the Oxidation Behavior of UO2 Pellets in Damaged Fuel Rods of Pressurized Water Reactors. Nucl. Eng. Techn. 52, 2880–2886. doi:10.1016/j.net.2020.05.007

Kim, D. S., Kim, K. S., Kim, J. J., Kim, D.-J., Yang, Oh, J.-S., Koo, Y.-H., et al. (2017). Aligning Mo Metal Strips in UO2 Fuel Pellets for Enhancing Radial Thermal Conductivity. Jeju, Korea: Water Reactor Fuel Performance Meeting at Korean Nuclear Society (KNS).

Kim, D. S., Kim, D.-J., Yang, J. H., Yoon, J. H., Lee, H.-S., and Kim, H.-G. (2020). Development of Mo Microplate Aligned UO2 Pellets for Accident Tolerant Fuel. Transactions of the Korean Nuclear Society Virtual Autumn Meeting.

Kim, D.-J., Kim, K. S., Kim, D. S., Oh, J. S., Kim, J. H., Yang, J. H., et al. (2018). Development Status of Microcell UO2 Pellet for Accident-Tolerant Fuel. Nucl. Eng. Techn. 50, 253–258. doi:10.1016/j.net.2017.12.008

Kim, Y. S. (2000). A Thermodynamic Evaluation of the U-O System from UO2 to U3O8. J. Nucl. Mater. 279, 173–180. doi:10.1016/s0022-3115(00)00019-2

Kim, Y. S. (2003). PWR Fuel Failure Analysis Due to Hydriding Based on PIE Data in Fuel Failure in Water Reactor; Cause and Mitigation. Vienna, Austria: IAEA-TECDOC-1245.

Kuhlman, W. C. (1948). Treatment of Uranium Dioxide with Water Vapor at High Temperature. Oak Ridge: Mallinckrodt Chemical Works. MCW-103. doi:10.2172/4309589

Lee, H. S., Kim, D. J., Yang, J. H., and Kim, D. R. (2019). Numerical and Experimental Investigation on thermal Expansion of UO2-5vol% Mo Microcell Pellet for Qualitative Comparison to UO2 Pellet. J. Nucl. Mater. 518, 342–349. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2019.03.003

Lee, Y.-J., Lee, T., and Soon, A. (2019). Phase Stability Diagrams of Group 6 Magnéli Oxides and Their Implications for Photon-Assisted Applications. Chem. Mater. 31, 4282–4290. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b01430

Lewis, B. J., Iglesias, F. C., Cox, D. S., and Gheorghiu, E. (1990). A Model for Fission Gas Release and Fuel Oxidation Behavior for Defected UO2Fuel Elements. Nucl. Techn. 92, 353–362. doi:10.13182/nt90-a16236

Li, W., and Shirvan, K. (2021). Multiphysics Phase-Field Modeling of Quasi-Static Cracking in Urania Ceramic Nuclear Fuel. Ceramics Int. 47, 793–810. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.08.191

Nelson, A. T., Sooby, E. S., Kim, Y.-J., Cheng, B., and Maloy, S. A. (2014). High Temperature Oxidation of Molybdenum in Water Vapor Environments. J. Nucl. Mater. 448, 441–447. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2013.10.043

Oguma, M. (1983). Cracking and Relocation Behavior of Nuclear Fuel Pellets during Rise to Power. Nucl. Eng. Des. 76, 35–45. doi:10.1016/0029-5493(83)90045-6

Olander, D. R. (1986). Oxidation of UO2by High-Pressure Steam. Nucl. Techn. 74, 215–217. doi:10.13182/nt86-a33806

Perio, P. (1955). Contribution to the Crystallography of the Uranium–Oxygen System. Paris: Doctoral Dissertation, University of Paris. CEA-363.

Sarrasin, L., Gaillard, C., Panetier, C., Pipon, Y., Moncoffre, N., Mangin, D., et al. (2019). Effect of the Oxygen Potential on the Mo Migration and Speciation in UO2 and UO2+x. Inorg. Chem. 58, 4761–4773. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b03076

Lee, H. S., Kim, D.-J., Kim, D. S., and Kim, D. R. (2020). Evaluation of Thermomechanical Behaviors of UO2−5 Vol% Mo Nuclear Fuel Pellets with Sandwiched Configuration. J. Nucl. Mater. 539. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/152295. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2020.152295

Spino, J., and Peerani, P. (2008). Oxygen Stoichiometry Shift of Irradiated LWR-Fuels at High Burn-Ups: Review of Data and Alternative Interpretation of Recently Published Results. J. Nucl. Mater. 375, 8–25. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2007.10.007

Teske, K., Ullmann, H., and Rettig, D. (1983). Investigation of the Oxygen Activity of Oxide Fuels and Fuel-Fission Product Systems by Solid Electrolyte Techniques. Part I: Qualification and Limitations of the Method. J. Nucl. Mater. 116, 260–266. doi:10.1016/0022-3115(83)90110-1

Une, K., Imamura, M., Amaya, M., Korei, Y., and Yagnik, S. K. (1995). Fuel Oxidation and Irradiation Behaviors of Defective BWR Fuel Rods. J. Nucl. Mater. 223, 40–50. doi:10.1016/0022-3115(94)00693-8

Verrall, R. A., He, Z., and Mouris, J. F. (2005). Characterization of Fuel Oxidation in Rods with Clad-Holes. J. Nucl. Mater. 344, 240–245. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2005.04.049

Yakub, E., Ronchi, C., and Staicu, D. (2009). Computer Simulation of Defects Formation and Equilibrium in Non-stoichiometric Uranium Dioxide. J. Nucl. Mater. 389, 119–126. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2009.01.029

Keywords: accident tolerant fuel, UO2-Mo pellet, steam oxidation, equilibrium composition, oxygen potential

Citation: Yang JH, Song KW, Kim DS, Kim D-J, Lee HS, Yoon J-H and Koo Y-H (2021) Thermodynamic Evaluation of Equilibrium Oxygen Composition of UO2-Mo Nuclear Fuel Pellet Under High Temperature Steam. Front. Energy Res. 9:667911. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2021.667911

Received: 15 February 2021; Accepted: 08 July 2021;

Published: 22 July 2021.

Edited by:

Jinbiao Xiong, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Ho Jin Ryu, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, South KoreaDi Yun, Xi’an Jiaotong University, China

Copyright © 2021 Yang, Song, Kim, Kim, Lee, Yoon and Koo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jae Ho Yang, eWFuZ2poQGthZXJpLnJlLmty

Jae Ho Yang

Jae Ho Yang Kun Woo Song

Kun Woo Song Heung Soo Lee

Heung Soo Lee