- 1Environmental Engineering Program, Zewail City of Science and Technology, Giza, Egypt

- 2Chemical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt

- 3Department of Environmental Engineering and Water Technology, UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education, Delft, Netherlands

- 4Chemical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Minia University, El-Minia, Egypt

This study aims to provide the technoeconomic aspects of two clean processes for biodiesel production. The first process utilizes waste cooking oil as a feedstock and potassium hydroxide as a homogeneous catalyst. The second process uses cement kiln dust heterogeneous catalyst and virgin soybean oil. A comparison was performed between the results of the technical and economic assessments to determine the more feasible process. Theoretical purities of biodiesel and glycerol obtained upon conducting the simulation of both processes are high, i.e., 99.99%. However, the homogeneous process is economically superior as its payback period is slightly more than 1 year while the return on investment is higher than 74%, and the unit production cost is USD 1.067/kg biodiesel. Sensitivity analysis revealed that the profitability of biodiesel production is very sensitive to the feedstock price and recommends shifting toward waste vegetable oils as a cheap feedstock to have a feasible and economic process.

Highlights

• Waste cooking oil (WCO) and cement kiln dust (CKD) were used for biodiesel production

• Comparative technoeconomic analysis was done for two biodiesel production processes

• Homogeneous technology using WCO was a more feasible path for biodiesel production

• Biodiesel production profitability is very sensitive to the price of the feedstock

Introduction

The transportation sector is considered to be a key contributor to climate change threats, with 24% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in 2016 (International Energy Association, 2018, CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion 2018 Highlights). Between 1990 and 2016, the carbon footprint of this sector increased by 71% (Hosking et al., 2011). The land transport is estimated to consume around 80% of the whole transportation energy, where the light-duty vehicles are the highest consumers followed by the freight trucks (WHO, 2012; health cobenefits of climate change mitigation-transport sector). Long-lived CO2 emission and short-lived black carbon (BC) are the main contributors to climate change from the transportation sector (Brewer, 2019). It is estimated that 19% of the global BC emissions are released from the transportation sector, specifically diesel vehicles (Helmers et al., 2019). Although the BC persists in the atmosphere for a few weeks only, its greenhouse effect is more impactful than CO2. Besides climate change, air pollutants emitted by diesel vehicles represent a threat to human health and the environment (Reche et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2019).

The replacement and/or adaptation of biodiesel over conventional diesel are in alignment with several sustainable development goals such as climate action and sustainable cities and communities (United Nations, 2015. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform). Hence, several governments and organizations adapted several green policies to use a considerable percentage of biofuels along with conventional fossil fuels to decrease their environmental impacts (Baena-Moreno et al., 2020). Biodiesel has been recognized recently as an environmental replacement for conventional petroleum diesel as it is associated with less environmental impacts (Živković and Veljković, 2018). For instance, it was found that biodiesel blend (B20: a mixture of 20% biodiesel and 80% petroleum diesel) is less opaque and produces less hydrocarbon and carbon monoxide emissions than petroleum diesel (Abed et al., 2019; Raman et al., 2019). Biodiesel is a monoalkyl ester of long-chain fatty acids that can be produced from renewable biological feedstock: vegetable oils, nonedible oils, animal fats, or waste oils (Al-Sakkari et al., 2017b; Dhawane et al., 2019). Different edible oils were used for biodiesel production such as soybean oil, rapeseed oil, and palm oil (Lam and Lee, 2011; Colombo et al., 2019; Essamlali et al., 2019; Raman et al., 2019). However, waste vegetable cooking oil and nonedible oils are more promising as a feedstock due to their low cost compared to edible ones (Mardhiah et al., 2017). Interestingly, many nonedible seed oils were found to be suitable for biodiesel synthesis such as Jatropha curcas, Ricinus communis, Madhuca indica, and Pongamia pinnata oils (Arumugam and Ponnusami, 2019; Elango et al., 2019; Awais et al., 2020; Kaur and Bhaskar, 2020).

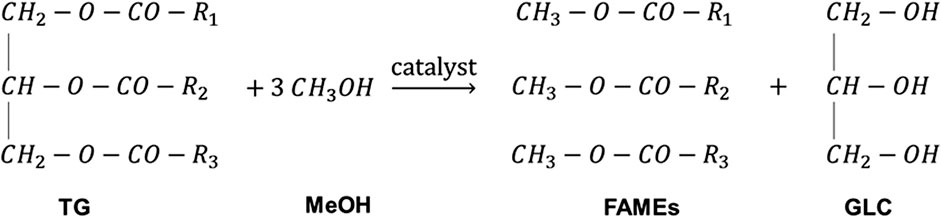

Biodiesel is commonly produced from oils through transesterification reaction (also called alcoholysis reaction) (Moazeni et al., 2019). In the transesterification reaction, triglycerides in oils and fats react with alcohol to form biodiesel and glycerol (GLC) (Tapanwong and Punsuvon, 2019) as shown in Figure 1. Methanol (MeOH) is usually used due to its availability and low price. The produced biodiesel from the reaction of oils and MeOH is fatty acid methyl ester. Ethanol is used for biodiesel production in countries where its price is lower than that of MeOH such as Brazil (Mączyńska et al., 2019). Transesterification reaction is reversible; therefore, excess alcohol is added (usually 1.6 times the stoichiometric amount) to enhance the forward reaction and increase the conversion (Zaharudin et al., 2018; Banerjee et al., 2019).

FIGURE 1. Transesterification reaction for biodiesel production. R1, R2, and R3 are long-chain hydrocarbon/fatty acids.

In commercial processes, the reaction is performed in the presence of a catalyst to speed up the reaction (El-Sheltawy and Al-Sakkari, 2016). Commonly used catalysts are acidic, alkaline (which can be homogeneous or heterogeneous), or enzyme catalysts (Gollakota et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Moazeni et al., 2019). Alkaline homogeneous catalysts such as sodium and potassium hydroxide are used for the commercial production of biodiesel from feedstocks having concentrations of free fatty acids (FFA) below 2%. Those alkaline catalysts cannot be used for higher FFA concentration because saponification reaction takes place as a side reaction as shown in Eq. 1 (El Sheltawy et al., 2019). Saponification reaction does not consume the catalyst only but also produces a soap that acts as an emulsifier and makes separating biodiesel from GLC very difficult (Chanakaewsomboon et al., 2020).

Low-cost feedstocks are usually rich in FFA (Al-Sakkari et al., 2020); therefore, acid pretreatment is necessary to promote the esterification of FFA in the presence of acid or enzyme catalyst according to Eq. 2 (Hosney et al., 2020). Enzyme catalysts lead to higher reaction rates than acid catalysts; however, they are unpractical to use in industrial scale due to their high price (Tabatabaei et al., 2019; Urbain et al., 2019). Transesterification reaction can be performed without a catalyst in supercritical conditions however, it is not economically feasible since these conditions require high utility costs (Kumar et al., 2020).

Biodiesel production is a rewarding process that is expected to be profitable at a large scale (Gebremariam and Marchetti, 2018b). Hence, detailed technoeconomic studies are essential to prove its feasibility and sensitivity to changes in market prices. Previous technoeconomic studies have been performed to compare the feasibility of biodiesel production processes from various feedstocks such as single-cell oils and acidic oils using different catalysts at different production capacities (Gebremariam and Marchetti, 2018a; Gebremariam and Marchetti, 2019; Parsons et al., 2019). The comparison is based on economic factors such as return on investment (ROI), net present value (NPV), and payback time. Additionally, sensitivity analysis of these factors as a function of expected changes in raw materials and products’ price is also taken into considerations.

This study aims to present a technoeconomic study on two processes for biodiesel production. The first process uses waste cooking oil in the presence of KOH as a homogeneous catalyst which is the conventional biodiesel production method. The second process uses virgin soybean oil in the presence of a newly developed cement kiln dust (CKD) heterogeneous catalyst (Al-Sakkari et al., 2017a). It should be mentioned that the price of waste cooking oil in this study is related to the Egyptian market, yet the study is still applicable and valid to be applied globally.

Methodology

Summary of Process Designs

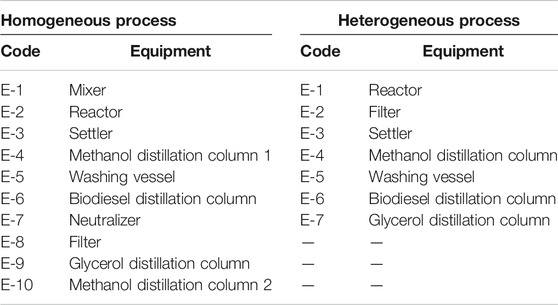

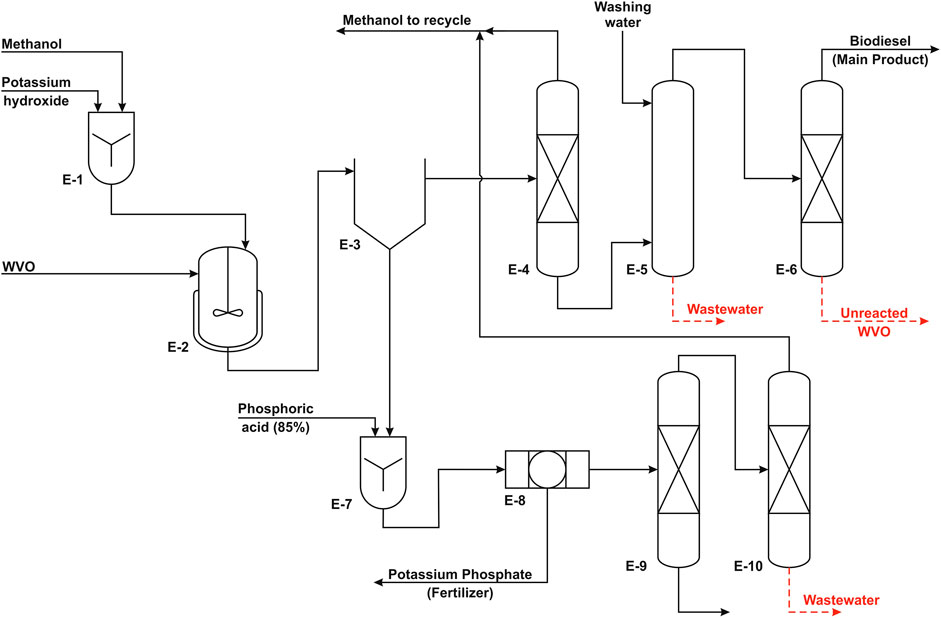

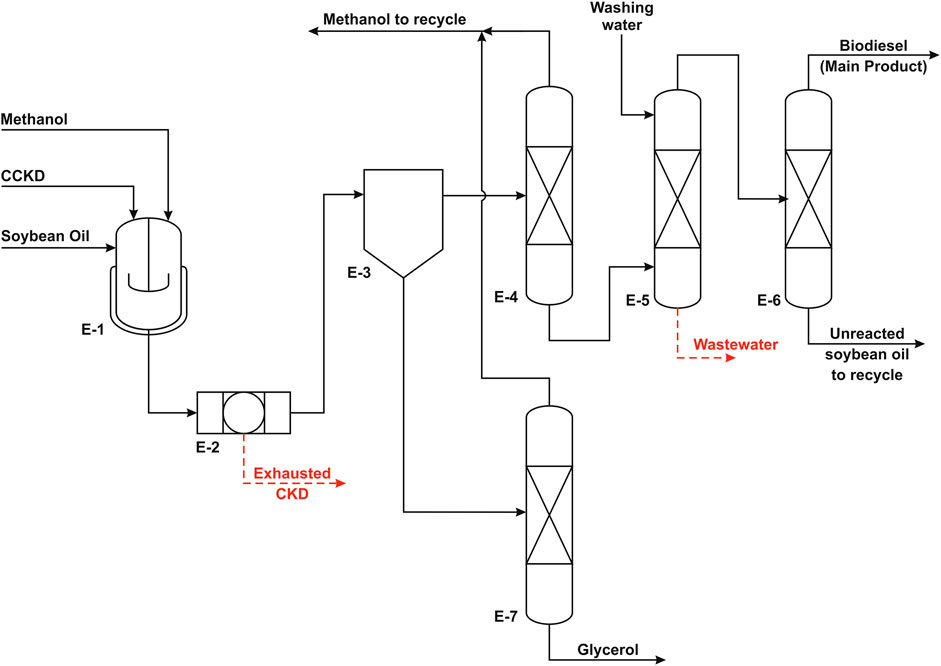

The present homogeneous process was first presented by Al-Sakkari et al. (2018a). In contrast, the heterogeneous process was presented in the study of El-Sheltawy et al. (2016). Figures 2 and 3 show the process flow diagrams of the homogeneously and heterogeneously catalyzed processes, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the equipment used in each PFD. The detailed process flow diagrams are mentioned in Supplementary Materials.

FIGURE 2. Process flow diagram of the homogeneous process (adapted from Al-Sakkari et al., 2018a).

FIGURE 3. Process flow diagram of the heterogeneous process (adapted from El-Sheltawy et al., 2016).

In the homogeneous process, the feedstock is waste vegetable oil (WVO) with low FFA content, and the catalyst is potassium hydroxide. On the other side, the catalyst in the heterogeneous process is calcined cement kiln dust (CCKD) particles in micron scale, and the feedstock is virgin soybean oil. MeOH is used for the alcoholysis purpose in both cases.

Summary Design of the Homogenous Process

Process Description

The suggested process for biodiesel production includes three major units. The first is the production unit where methyl ester (biodiesel) is produced from the reaction of waste vegetable oil with MeOH in the presence of KOH catalyst. In the second unit, the reactor effluent is fed to a gravity separator (decanter) to separate biodiesel (light layer) from GLC (heavy layer). This separation is followed by the biodiesel purification unit where crude biodiesel is distilled and water washed until its purity matches the ASTM D6751 standards. The last unit is the GLC purification unit, where crude GLC is treated with phosphoric acid to remove the catalyst and produce potassium phosphate as a by-product and then distilled in two columns to separate GLC from MeOH that is recycled to the reaction unit.

Biodiesel Production Unit

In this production unit, biodiesel is being produced according to the optimal conditions that have been investigated earlier in an experimental study (Al-Sakkari et al., 2018b). The suggested process is carried out in an isothermal batch reactor at 65°C while using MeOH to oil molar ratio of 6 : 1 and KOH as a catalyst with the loading of 1 weight % of WVO with a reaction time of 1 h. The optimum agitation speed that was reached during the experimental study was ∼400 rpm; however, this value should be adjusted on scaling up to confirm the constant mass transfer rate. The reaction conversion is 95% under the mentioned conditions. It is possible to make the process more energy efficient by using the reactor effluent stream to heat the feed to the reactor. This will reduce the temperature of the effluent stream, which enhances the separation efficiency of GLC and biodiesel layers in the decanter. The decanter is designed to have a residence time of 12 h to ensure efficient separation.

Biodiesel Purification Unit

The aim of this unit is the removal of MeOH and unreacted WVO from biodiesel to meet ASTM D6751 standards. The residual MeOH associated with the biodiesel layer is removed by distillation where MeOH is produced as a top product. The removed MeOH is recycled to the MeOH tank to reduce any potential process losses. It was found that the MeOH content in this biodiesel layer is ∼2–3 wt%. The bottom products are directed to a washing vessel to wash out any traces of MeOH, GLC, soaps, and catalyst residues using warm demineralized washing water. A coalescer is attached to that vessel to produce a top product clear from water contaminations. GLC washing should be performed under laminar flow conditions at relatively high temperature, e.g., 80°C. After that, a vacuum distillation column is used to remove any unreacted oil. Vacuum conditions are used to avoid any thermal cracking of biodiesel and the unreacted oil. Finally, the purified biodiesel is pumped and injected using some additives such as TBHQ in a well-insulated storage tank to increase biodiesel stability and reduce/eliminate oxidation during storage. The additives are commonly added at 1 wt% of biodiesel as recommended by Chakraborty and Baruah (2012) and Dwivedi et al. (2018).

Glycerol Purification Unit

This unit produces high purity GLC from the crude GLC layer that is composed of GLC (around 50%), potassium hydroxide, and FFA. This is achieved first by neutralizing potassium hydroxide using commercial phosphoric acid to produce potassium phosphate that is a by-product (e.g. fertilizer). During potassium hydroxide neutralization, FFA are separated spontaneously as a separate phase on the surface of GLC that is skimmed and removed later. After neutralization, the purity of the produced GLC increases to around 80%. Afterward, crude GLC is pumped to an atmospheric distillation column to wash out any excess MeOH as well as contaminated water to produce high-grade GLC that is cooled and stored at ambient temperature. The aqueous phase from atmospheric distillation is fed to another distillation column to recover the excess MeOH used in the reaction and reuse it in the reaction.

Summary Design of Heterogeneous Process

The heterogeneous process consists of three main units: the biodiesel production unit, the biodiesel purification unit, and the GLC purification unit. Each process is described briefly in the following sections.

Biodiesel Production

The biodiesel production reaction is carried out at 65°C in an isothermal batch reactor. MeOH is loaded into the reactor at a rate of 12 mol MeOH/mol oil followed by the addition of the catalyst, CKD. The CKD loading is 3.5% of the weight of oil to ensure high reaction conversion. The reaction takes place in two sequential cycles with 6 h of total reaction time. Under such operating condition, the conversion is estimated to be approximately 51%. The reactor effluent is filtered in a filter press to remove all the solid catalyst from the mixture. The separation results in two separate layers that will be purified to produce high purity biodiesel and GLC.

Biodiesel Purification

Biodiesel layer purification involves three steps. First, the extra MeOH which accounts for around 3% of the mixture is recovered using distillation and reused in the reaction. The MeOH-free mixture is washed using the same volume of freshwater in a washing vessel to remove any MeOH traces and GLC content as well as suspended catalyst resides or leached oxide if present. The washing vessel is equipped with a coalescer to remove any water droplets. The flow in the washing vessel is ensured to be laminar to prevent emulsification and facilitate the separation of used washing water. Finally, the ester stream is transferred to a vacuum distillation column to separate the purified fraction from the unreacted oil. The biodiesel is produced as a top product that is cooled and pumped to storage tanks.

Glycerol Purification

The GLC layer stream is fed to a distillation unit to extract the excess MeOH that is recycled to the reaction. The bottom product from the GLC purification column is nearly pure and clear of any dissolved solids and suspended catalyst residues. It is cooled and pumped to storage tanks.

Cost Estimation

The economic study starts with an estimation of the fixed cost, production cost, and the profit achieved for both processes. The two processes are then compared according to their economic feasibility based on a biodiesel production rate of 24,000 kg/day. Moreover, it includes a study of the economic sensitivity of both processes to the factors that have the most significant impact on their profitability.

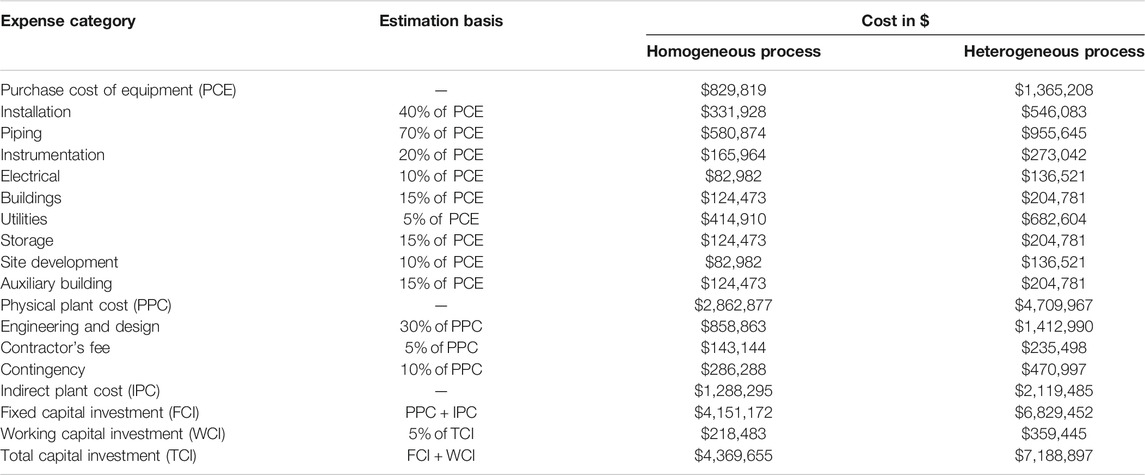

Cost estimation was studied based on the cost for capital, equipment, raw materials, operation, utilities, and labor according to literature (Gebremariam and Marchetti, 2018a) and the current market price in Egypt. For estimating the purchased cost of equipment (PCE), we used the method developed by Peters and Timmerhaus (Peters et al., 2003) with the chemical engineering plant cost index 591.34 for the year 2018 (Jenkins, 2019). Table 2 summarizes all the estimated costs included in the physical plant cost (PPC) for both processes; the estimation of these prices was performed as suggested by the reference mentioned earlier. Table 2 also includes indirect plant costs and fixed and working capital investments for both processes. The total capital investment shows that the homogeneous process requires capital investment 39% less than that of the heterogeneous process.

TABLE 2. Detailed calculations of the physical plant costs, indirect plant costs, and the total capital investments of the homogeneous and heterogeneous processes.

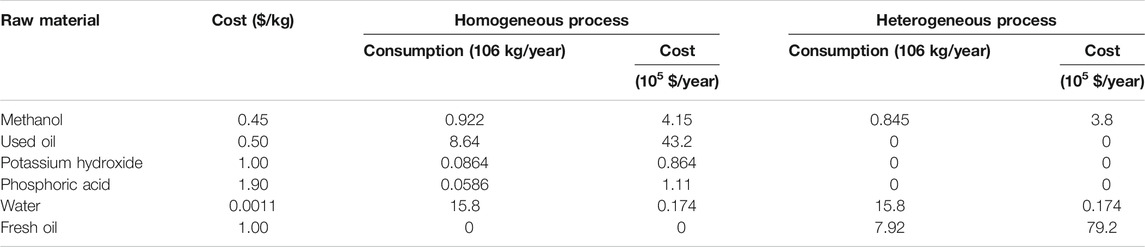

The total production cost includes variable and fixed charges. Variable charges represent the expenses associated with the manufacturing process such as the costs of required raw materials, utilities, shipping, and labor. The raw materials’ market price demand of each raw material for the homogeneous and heterogeneous processes and the total expected raw materials’ costs are summarized in Table 3. Required utilities such as cooling water, steam, and their costs for each process were calculated separately. The total labor cost is calculated for 330 annual working days using the average hourly labor cost in Egypt, for the year 2018 (Egypt Minimum Monthly Wages). Fixed charges represent the charges that do not change considerably from year to year and are not associated with the manufacturing process such as depreciation, taxes, and insurance. Fixed charges were calculated according to the procedure suggested by Peters and Timmerhaus (Peters et al., 2003).

TABLE 3. Market costs, annual consumptions, and total cost of raw materials for the homogeneous and heterogeneous processes.

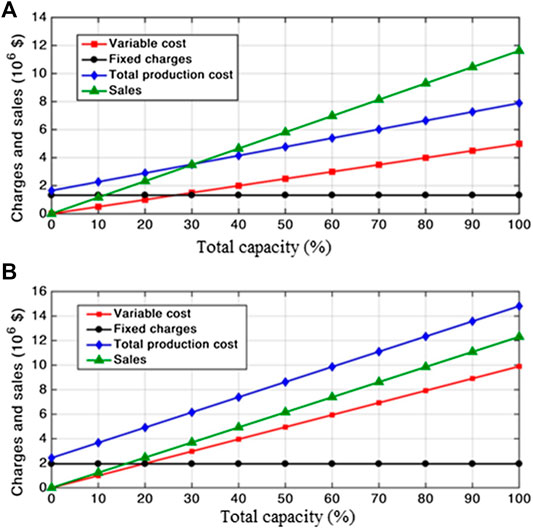

Breakeven Point

The basic idea of breakeven point analysis is to plot the production expenses, sales, and revenues against the percentage of full production capacity in order to determine the point at which both production expenses and sales are equal, and hence the revenues are zero. This point is called the breakeven point. Expenses, sales, and revenues are first calculated at different percentages of full production capacity, i.e., 0 and 10% till reaching 100%, and are plotted against the corresponding percentages to determine the zero-revenue point, i.e., breakeven point. It should be noticed that the lower the point is, the more profitable and feasible the process is.

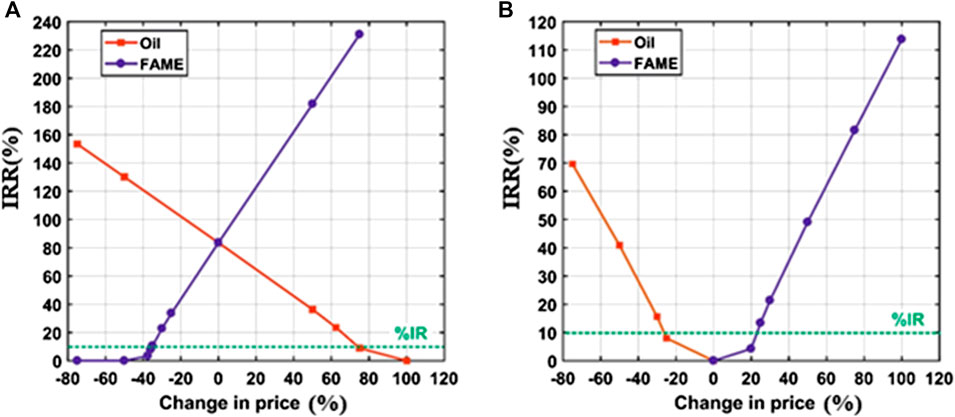

Sensitivity Analysis

In this study, the focus was profitability to the change (increase and decrease) in raw materials and products’ prices. The effect of changing the prices on the interest rate of return (IRR) at which the NPV of the project equals zero was studied. The calculated values of IRR are plotted against the percentage change of prices of both the products and the raw materials. Furthermore, they are compared to the interest rate (IR) value of 10% to check on the profitability of the process. The process is considered feasible and profitable if the IRR is greater than IR.

Results and Discussion

Process Designs

Material and Energy Balance of the Homogeneous Process

The material and energy balance calculations were performed using Aspen Plus software (Thermodynamic model was NRTL General). Supplementary Appendix S1 summarizes the material and energy balance calculation results of the proposed process. It can be observed that the highest flow rates were for the inlet and outlet streams of the batch reactor compared to other streams. These high flow rates result from the short time taken for charging and discharging the batch reaction processes. Also, water traces in the recycled MeOH that come from the GLC purification unit are eliminated to avoid any water accumulation in the system, which is harmful to the transesterification reaction. Water removal can be achieved by adsorption instead of distillation for small flow rates.

Summary of Material and Energy Balances of the Heterogeneous Process

From the experimental results, the oil conversion at the assigned conditions is 51%; hence the daily amount of oil required for a biodiesel production rate of 24 ton/day is 47 tons. Catalyst loading is 1.65 tons which correspond to 3.5 wt% of the total oil introduced, and the MeOH loading rate into the reactor is 19 ton/day to match the specifications mentioned earlier. The summary of operating conditions and composition of each stream of the processes is available in Supplementary Appendix S2.

The flow rates of streams S-1 to S-5 may appear to be larger than other streams as they serve as the point of charging and discharging the biodiesel batch reactors. After cooling, the excess MeOH and unreacted oil are recycled to enhance the process profitability. Besides, the cost of heating and cooling is minimized by heat integration, such as using wastewater from the biodiesel washing step for heating the batch reactor.

Cost Estimation

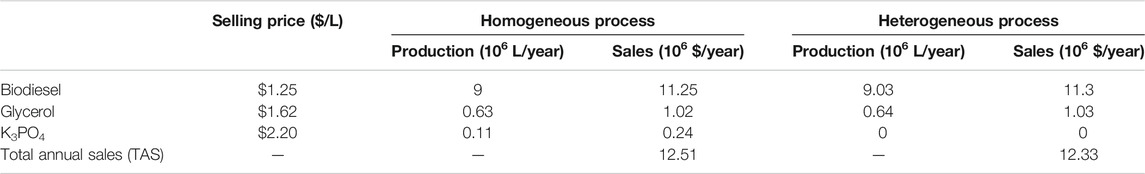

Total production cost was calculated based on the fixed and variable production costs for both processes and was found to be 8.45 million dollars for the homogenous process and 14.81 million dollars for the heterogeneous process. Table 4 shows the total annual production and sales of the main and side products of the homogeneous and heterogeneous processes; the results indicate that both processes seem to achieve the same annual profit. However, for profitability, indicators were calculated to compare the economic feasibility of both processes: annual gross profit, annual net profit, payback period, and ROI. The values and the method of calculation of the indicators are shown in Table 5; these indicators show that the heterogeneous process is economically infeasible in contrary to the homogeneous process. Based on Tables 2 and 3, the heterogeneous process is unprofitable due to the high cost of fresh oil used and the high costs of large equipment used to separate the solid catalyst after the reaction.

TABLE 4. Market prices, annual production, and total sales of products for the homogeneous and heterogeneous processes.

The profitability study recommends the homogeneous process over the heterogeneous process. Further analysis of the economic feasibility is done and presented in the sensitivity analysis section.

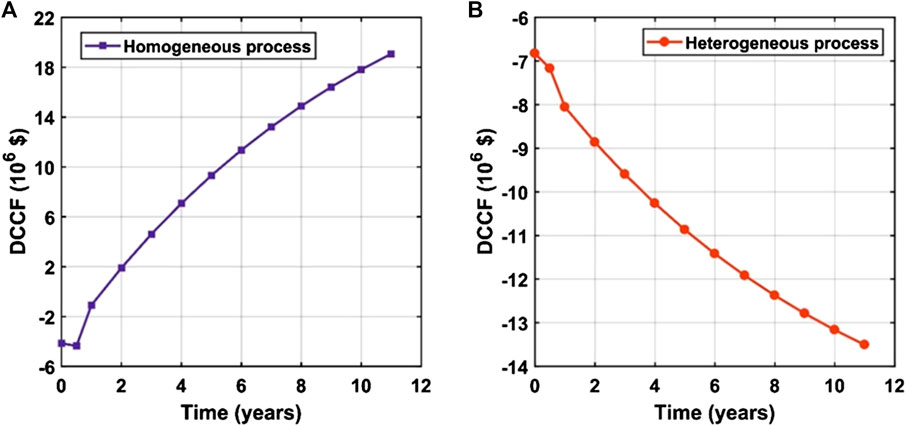

Breakeven Point Analysis

Breakeven point analysis was performed for both processes. The heterogeneous process was found to be unprofitable due to high fixed charges as well as using expensive feedstock; therefore, it has no breakeven point as indicated from Figure 4B. These results are in alignment with the previously mentioned results (Cost Estimation). However, in the case of a homogeneous process, Figure 4A depicts a breakeven point at about 30% of the full capacity. This finding indicates a highly profitable process for biodiesel production.

Sensitivity Analysis

In this section, the sensitivity of the process profitability to the change of raw materials and products’ prices are presented. It was found that the processes are very sensitive to the prices of feedstock oil and the main product “biodiesel.” The process profitability is not sensitive to changes in prices of other materials and utilities when compared to the prices of oil and biodiesel. In this study, it was assumed that the plant would work at full capacity for 10 years after installation and startup periods which would take 6 months each. Discount cumulative cash flow diagrams (Figures 5A,B) are used as preliminary indicators to compare the profitability of both processes over the project lifetime.

FIGURE 5. Discount cumulative cash flow as a function of the operating time (years) for the (A) homogeneous process and (B) heterogeneous process.

From Figures 4 and 5, it can be concluded that the homogeneous process is profitable since the payback period is about 1.07 years. This can be attributed to the utilization of relatively cheap feedstock besides operating at mild reaction conditions, i.e., MeOH to oil molar ratio of 6 : 1, reaction temperature of 65°C, and 1% catalyst loading. Moreover, the obtained conversion is high, i.e., 95%, in a shorter reaction time of about 1 h compared to the heterogeneous process. These conditions also affect the whole profitability positively by decreasing the load on the following separation equipment. In contrast, the heterogeneous process is unprofitable at its current state. The process profitability can be enhanced by using WVO as a feedstock instead of the expensive virgin oil feedstock. The following sensitivity analysis results support this recommendation.

As mentioned previously, the goal of the sensitivity analysis is to study the effect of changing the prices on the IRR at which the NPV of the project equals zero. Figures 5A,B show the calculated values of IRR as a function of the percentage change of prices of both products and raw materials. Furthermore, they are compared to the IR value of 10% (highlighted in green in Figures 6A,B) to check the profitability of the process. The process is considered feasible and profitable if the IRR is greater than IR.

Figure 6. IRR (%) sensitivity to the change of market prices of oil and FAME for the (A) homogeneous process and (B) heterogeneous process. The dotted green lines represent the IR.

As shown in Figure 5, the homogeneous process at its current state (0% change in prices) has high profitability as the IRR equals about 83.57%, which is significantly higher than IR. The figure also shows that IRR increases to approximately 130% due to a decreased in the oil price by 50%. Similarly, IRR will have a value of about 182% if the biodiesel price increases by 50%. On the other hand, for the heterogeneous process to be profitable, the feedstock cost should be lower by 27.5% or the biodiesel selling price should be higher by 25%. These observations confirm the previous recommendation of using waste oils instead of virgin oils, besides the need to conduct a new investigation about the ability and efficiency of using CCKD as a heterogeneous catalyst to produce biodiesel from WVO. Obviously, the processes in both cases are more sensitive to the change of biodiesel price than to the change of oil price. However, it is more economical to find a cheaper oil feedstock than increasing the selling price of biodiesel which is constrained by the market.

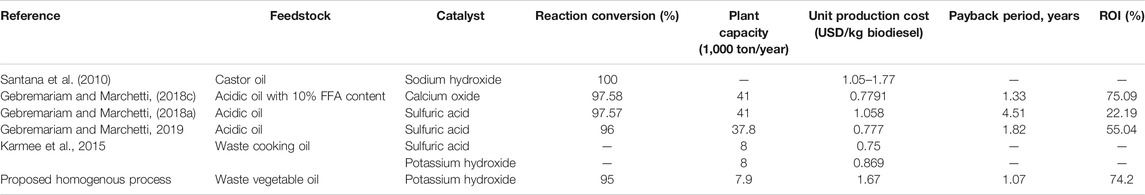

Comparison With Literature Reports on the Technoeconomic Feasibility of Biodiesel Production

Many researchers are concerned about the feasibility of biodiesel production through different techniques (Fazal et al., 2011; Marchetti, 2011; Basili and Rossi, 2018; Kookos, 2018). Accordingly, they assessed the economic aspects and parameters of various manufacturing processes such as the fixed, operating, and production cost (Skarlis et al., 2012; Gülşen et al., 2014; Gebremariam and Marchetti, 2018b). For instance, Santana et al. (2010) conducted a technoeconomic analysis on biodiesel synthesis from virgin castor oil through homogeneously catalyzed transesterification, where sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was used as a catalyst and ethanol was utilized as a reactant in excess (12 : 1 ethanol to oil molar ratio). According to the authors, the cost of virgin oil was found to have the greatest attribution to the biodiesel production cost which ranged from 0.92 to USD 1.56/L according to the cost and quality of feedstock in addition to the process size. One of the most important recommendations of this study is to use WCO as a feedstock in order to raise process profitability.

In a more recent study, a two-step biodiesel production process was evaluated technically and economically (Gebremariam and Marchetti, 2018c). Sulfuric acid (H2SO4) was used as a catalyst for the pretreatment step, whereas calcium oxide (CaO) was utilized as a heterogeneous base catalyst for the transesterification step. This two-step technique was proposed as a result of using acidic oil as a low-cost feedstock. Two other processes were also investigated; one of them used sulfuric acid only as of the catalyst and the other one utilized calcium oxide (CaO) only for the conversion of acidic waste oil to methyl esters. This study concluded that using calcium oxide alone was the best economically.

On the other hand, the least feasible process was the one converting acidic oil using sulfuric acid as a catalyst without the aid of CaO. This is logically correct as this process needs severe conditions and high alcohol amount in addition to the long reaction time. It should be mentioned that the economic parameters considered in this study included the payback period, production cost, and ROI%. The payback period of the CaO process was calculated as 1.33 years, and the ROI% was observed to be 75.09%, whereas the unit production cost of biodiesel had the value of USD 0.7791/kg. The flow rate of biodiesel exiting from the optimum process was 5,132 kg/h at a conversion of 97.58% which was attained at the conditions of 9 : 1 ethanol to oil molar ratio, 7 wt% CaO loading, and 75°C where the residence time was 2 h.

Another study performed by the same research group suggested four alternative processes for biodiesel synthesis from high FFA content waste oil as a cheap feedstock (Gebremariam and Marchetti, 2018a). In all alternatives, sulfuric acid was utilized as the catalyst for acidic oil conversion into fatty acid methyl esters and calcium oxide was used only for catalyst neutralization after the reaction. The difference between all these proposed schemes was the arrangement of the downstream processes in order to purify produced biodiesel. The second scenario or alternative in this study was found to be superior economically over the others. It suggested that neutralization should be done directly after reaction followed by centrifugation for solids removal, ethanol recovery, GLC separation, and finally biodiesel purification from heavy wastes. The payback period of this process was 4.51 years. Besides, the unit production cost was USD 1.058/kg biodiesel, and the ROI% was only 22.19%. When compared with the previous study, this process is much less feasible and cannot be recommended for commercial production of biodiesel, although the feedstock is a cheap one. This also confirms the superiority of base-catalyzed biodiesel production over the acidic techniques. It should be stated that the flow rate of biodiesel production related to this scenario is 5,282 kg/h, and the factory operates 7,920 h per year.

Moreover, the utilization of KOH as the homogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production from WCO was analyzed economically (Karmee et al., 2015). The production capacity of this plant was 8,000 ton per year. The unit production cost was estimated as USD 0.8686/kg biodiesel. For the same capacity, H2SO4 and Novozyme 435 were used as catalysts as well. Surprisingly, the unit production cost in the case of sulfuric acid was equal to almost USD 0.75/kg biodiesel. Novozyme 435 catalyzed process was the most expensive one among those three proposed processes as the production cost equivalent to 1 kg of biodiesel was USD 1.048.

Upon utilizing basic CaO heterogeneous catalyst, Gebremariam and Marchetti (2019) suggested four different scenarios to accomplish acidic oil conversion into biodiesel. Three scenarios considered the direct transesterification without any preesterification steps; nonetheless, only one alternative, i.e., scenario II, included preesterification using sulfuric acid as a catalyst followed by transesterification by ethanol in the presence of CaO. It is worthy mentioning that the processes without preesterification step resulted in the production of the considerable amount of calcium soaps which is usually considered as an undesired side product. However, in that study, the authors considered it a valuable by-product that can add to process feasibility; However, they were removed using a centrifuge. Unfortunately, despite avoiding the production of any soap, scenario II was the worst concerning GLC purity and the economics. For example, ROI% of this process was only 36.81% compared to the highest one, i.e., 56.26%, related to scenario III. In addition, it had the highest unit production cost of USD 0.8617/kg biodiesel in comparison with the lowest one of scenario IV, which was the only USD 0.777/kg biodiesel. Regarding the payback period, it was estimated to have the values of 2.72, 1.78, and 1.82 for scenarios II, III, and IV, respectively. The authors concluded that alternative IV is superior over the other scenarios because it yielded highly pure biodiesel, i.e., 99.9% purity, and GLC 99% pure with a performance factor of 1.02. It was also an excellent and feasible option for biodiesel production from the acidic oil which is a cheap raw material. The production rate of this scenario was 5,256.6 kg/h, and the reaction took place in two reactors in series.

In comparison with the aforementioned processes for biodiesel production, the proposed homogeneous process in the current study represents a competitive one as it can be observed from Table 6. The payback period is relatively low as it takes the value of 1.07 years while the ROI% is as high as 74.18% and the unit production cost is USD 1.067/kg biodiesel. Furthermore, the purities of both biodiesel and GLC are high, i.e., 99.999%. This study is also in good agreement with literature and matches the previous technoeconomic studies as it confirmed that the high production process has economic sensitivity towards the type, origin and price of feedstock used.

TABLE 6. Summary of economic performance indicators of the suggested process and other published processes.

Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Work

This comparative technoeconomic study illustrated that the homogeneous process has a relatively high profitable profile as its payback period is only 1.07 years besides having an IRR of 83.57%. Moreover, its breakeven point is 30% of the full capacity. On the contrary, the heterogeneous process is infeasible; therefore, the homogeneous process is preferable. Sensitivity analysis revealed the high sensitivity of biodiesel production toward feedstock price. For instance, the oil price should be reduced by 27.5% to gain profit from the heterogeneous process.

It is highly recommended to use waste vegetable oil as a feedstock for the heterogeneous process to enhance process profitability. Accordingly, a detailed study of the optimization of the factors affecting biodiesel production from waste vegetable oil using cement kiln dust as a heterogeneous catalyst should be performed to meet the sustainable development goals. This study will give the optimum conditions needed to conduct a detailed process simulation and test the process from an economic viewpoint. For a more accurate comparison, life cycle assessment should be performed on the different production processes to not only select the most feasible option, but also find the greenest path for biodiesel production.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

EA: investigation, validation, data analysis, writing—Original draft, visualization, conceptualization, methodology, project administration. MM: investigation, validation, data analysis, writing—original draft, visualization, conceptualization, methodology, supervision. AE: investigation, writing—original draft and visualization. OA: writing—original draft. MH: writing—original draft. EO: writing—original draft. ER: revision and supervision. II: revision and supervision. IA: revision and supervision.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge that this study was a part and outcome of ENEPLAN project (http://www.eneplan-erasmus.eu/) which is co-funded by ERASMUS + Program of European Union and Zewail City of Science and Technology was a partner of it. EGA, OMA, AAE, and MMH acknowledge Zewail City of Science and Technology for supporting high-quality research and enrolling students in international projects. OMA, MMH, and ESO would like to thank Erasmus Mundus International Master of Science in Environmental Technology and Engineering (IMETE) for supporting the M.Sc. program at UCT Prague (Czech Republic), IHE Delft (The Netherlands), and Ghent University (Belgium). ERR thanks the Environmental Science (ES) program at IHE Delft for providing staff time support.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenrg.2020.583357/full#supplementary-material

Glossary

BC: Black carbon

CCKD: Calcined cement kiln dust

CKD: Cement kiln dust

FAME: Fatty acid methyl ester

FFA: Free fatty acids

FCI: Fixed capital investment

GLC: Glycerol

IR: Interest rate

IRR: Interest rate of return

NPV: Net present value

PCE: Purchase cost of equipment

PPC: Physical plant cost

ROI: Return on investment

SDGs: Sustainable development goals

TBHQ: Tertiary butylhydroquinone

TCI: Total capital investment

TG: Triglycerides

TPC: Total production cost

WCI: Working capital investment

WVO: Waste vegetable oil.

References

Abed, K. A., Gad, M. S., El Morsi, A. K., Sayed, M. M., and Elyazeed, S. A. (2019). Effect of biodiesel fuels on diesel engine emissions. Egypt. J. Pet. 28, 183–188. doi:10.1016/j.ejpe.2019.03.001

Al-Sakkari, E. G., Abdeldayem, O. M., El-Sheltawy, S. T., Abadir, M. F., Soliman, A., Rene, E. R., et al. (2020). Esterification of high FFA content waste cooking oil through different techniques including the utilization of cement kiln dust as a heterogeneous catalyst: a comparative study. Fuel 279, 118519. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118519

Al-Sakkari, E. g., El-Sheltawy, S. t., Abadir, M. f., Attia, N. k., and El-Diwani, G. (2017a). Investigation of cement kiln dust utilization for catalyzing biodiesel production via response surface methodology. Int. J. Energy Res. 41, 593–603. doi:10.1002/er.3635

Al-Sakkari, E. G., El-Sheltawy, S. T., Attia, N. K., and Mostafa, S. R. (2017b). Kinetic study of soybean oil methanolysis using cement kiln dust as a heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 206, 146–157. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.01.008

Al-Sakkari, E. G., El-Sheltawy, S. T., Soliman, A., and Ismail, I. (2018a). Methanolysis of low FFA waste vegetable oil using homogeneous base catalyst for biodiesel production: new process design. J. Adv. Chem. Sci. 4, 593–597. doi:10.30799/jacs.196.18040401

Al-Sakkari, E. G., El-Sheltawy, S. T., Soliman, A., and Ismail, I. (2018b). Transesterification of low FFA waste vegetable oil using homogeneous base catalyst for biodiesel production: optimization, kinetics and product stability. J. Adv. Chem. Sci. 4, 586–592. doi:10.30799/jacs.195.18040305

Arumugam, A., and Ponnusami, V. (2019). Biodiesel production from Calophyllum inophyllum oil a potential non-edible feedstock: an overview. Renew. Energy. 131, 459–471. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2018.07.059

Awais, M., Musmar, S. e. A., Kabir, F., Batool, I., Rasheed, M. A., Jamil, F., et al. (2020). Biodiesel production from melia azedarach and Ricinus communis oil by transesterification process. Catalysts 10, 427. doi:10.3390/catal10040427

Baena-Moreno, F. M., Sebastia-Saez, D., Wang, Q., and Reina, T. R. (2020). Is the production of biofuels and bio-chemicals always profitable? Co-production of biomethane and urea from biogas as case study. Energy Convers. Manag. 220, 113058. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113058

Banerjee, S., Sahani, S., and Chandra Sharma, Y. (2019). Process dynamic investigations and emission analyses of biodiesel produced using Sr-Ce mixed metal oxide heterogeneous catalyst. J. Environ. Manag. 248, 109218. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.06.119

Basili, M., and Rossi, M. A. (2018). Brassica carinata-derived biodiesel production: economics, sustainability and policies. The Italian case. J. Clean. Prod. 191, 40–47. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.306

Brewer, T. L. (2019). Black carbon emissions and regulatory policies in transportation. Energy Pol. 129, 1047–1055. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.02.073

Chakraborty, M., and Baruah, D. C. (2012). Investigation of oxidation stability of Terminalia belerica biodiesel and its blends with petrodiesel. Fuel Process. Technol. 98, 51–58. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2012.01.029

Chanakaewsomboon, I., Tongurai, C., Photaworn, S., Kungsanant, S., and Nikhom, R. (2020). Investigation of saponification mechanisms in biodiesel production: microscopic visualization of the effects of FFA, water and the amount of alkaline catalyst. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 8, 103538. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2019.103538

Colombo, K., Ender, L., Santos, M. M., and Chivanga Barros, A. A. (2019). Production of biodiesel from Soybean oil and methanol catalyzed by calcium oxide in a recycle reactor. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 28, 19–25. doi:10.1016/j.sajce.2019.02.001

Dhawane, S. H., Al-Sakkari, E. G., and Halder, G. (2019). Kinetic modelling of heterogeneous methanolysis catalysed by iron induced on microporous carbon supported catalyst. Catal. Lett. 149, 3508–3524. doi:10.1007/s10562-019-02905-5

Dwivedi, G., Verma, P., and Sharma, M. P. (2018). Optimization of storage stability for karanja biodiesel using box-behnken design. Waste Biomass Valor. 9, 645–655. doi:10.1007/s12649-016-9739-2

Egypt minimum monthly wages. Available at: https://tradingeconomics.com/egypt/minimum-wages (Accessed September 18, 2020).

El-Sheltawy, S. T., and Al-Sakkari, E. G. (2016). Recent trends in solid waste utilisation for biodiesel production. J. Solid Waste Technol. Manag. 42, 302–312.

El-Sheltawy, S. T., Al-Sakkari, E. G., and Fouad, M. (2016). Modeling and process simulation of biodiesel production from soybean oil using cement kiln dust as a heterogeneous catalyst. J. Solid Waste Technol. Manag. 42, 313–324.

El Sheltawy, S. T., Al-Sakkari, E. G., and Fouad, M. M. K. (2019). “Waste-to-energy trends and prospects: a review,” in Waste management and resource efficiency. Editor Ghosh, S. K. (Singapore: Springer), 673–684. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-7290-1_56

Elango, R. K., Sathiasivan, K., Muthukumaran, C., Thangavelu, V., Rajesh, M., and Tamilarasan, K. (2019). Transesterification of castor oil for biodiesel production: process optimization and characterization. Microchem. J. 145, 1162–1168. doi:10.1016/j.microc.2018.12.039

Essamlali, Y., Amadine, O., Fihri, A., and Zahouily, M. (2019). Sodium modified fluorapatite as a sustainable solid bi-functional catalyst for biodiesel production from rapeseed oil. Renew. Energy. 133, 1295–1307. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2018.08.103

Fazal, M. A., Haseeb, A. S. M. A., and Masjuki, H. H. (2011). Biodiesel feasibility study: an evaluation of material compatibility; performance; emission and engine durability. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 15, 1314–1324. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2010.10.004

Gebremariam, S. N., and Marchetti, J. M. (2018a). Biodiesel production through sulfuric acid catalyzed transesterification of acidic oil: techno economic feasibility of different process alternatives. Energy Convers. Manag. 174, 639–648. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2018.08.078

Gebremariam, S. N., and Marchetti, J. M. (2018b). Economics of biodiesel production: Review. Energy Convers. Manag. 168, 74–84. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2018.05.002

Gebremariam, S. N., and Marchetti, J. M. (2018c). Techno-economic feasibility of producing biodiesel from acidic oil using sulfuric acid and calcium oxide as catalysts. Energy Convers. Manag. 171, 1712–1720. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2018.06.105

Gebremariam, S. N., and Marchetti, J. M. (2019). Techno‐economic performance of a bio‐refinery for the production of fuel‐grade biofuel using a green catalyst. Biofuels Bioprod. Bioref. 13, 936–949. doi:10.1002/bbb.1985

Gollakota, A. R. K., Volli, V., and Shu, C.-M. (2019). Transesterification of waste cooking oil using pyrolysis residue supported eggshell catalyst. Sci. Total Environ. 661, 316–325. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.165

Gülşen, E., Olivetti, E., Freire, F., Dias, L., and Kirchain, R. (2014). Impact of feedstock diversification on the cost-effectiveness of biodiesel. Appl. Energy. 126, 281–296. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.03.063

Helmers, E., Leitão, J., Tietge, U., and Butler, T. (2019). CO2-equivalent emissions from European passenger vehicles in the years 1995-2015 based on real-world use: assessing the climate benefit of the European "diesel boom".” Atmos. Environ. 198, 122–132. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.10.039

Hosking, J., Mudu, P., and Fletcher, E. (2011). Health co-benefits of climate change mitigation: transport sector. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Hosney, H., Al-Sakkari, E. G., Mustafa, A., Ashour, I., Mustafa, I., and El-Shibiny, A. (2020). A cleaner enzymatic approach for producing non-phthalate plasticiser to replace toxic-based phthalates. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy. 22, 73–89. doi:10.1007/s10098-019-01770-5

International Energy Association (2018). CO2 emissions from fuel combustion 2018 highlights. Paris, France: International Energy Association. Available at: https://webstore.iea.org/co2-emissions-from-fuel-combustion-2018-highlights (Accessed September 18, 2020).

Jenkins, S. (2019). Chemical engineering plant cost index: 2018 annual value. Chem. Eng. Available at: https://www.chemengonline.com/2019-cepci-updates-january-prelim-and-december-2018-final/?printmode=1 (Accessed September 18, 2020).

Karmee, S., Patria, R., and Lin, C. (2015). Techno-economic evaluation of biodiesel production from waste cooking oil-A case study of Hong Kong. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 4362–4371. doi:10.3390/ijms16034362

Kaur, R., and Bhaskar, T. (2020). “Potential of castor plant (Ricinus communis) for production of biofuels, chemicals, and value-added products,” in Waste biorefinery. Editors Bhaskar, T., Pandey, A., Rene, E. R., and Tsang, D. C. W. (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier), 269–310. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-818228-4.00011-3

Kookos, I. K. (2018). Technoeconomic and environmental assessment of a process for biodiesel production from spent coffee grounds (SCGs). Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 134, 156–164. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.02.002

Kumar, L. R., Yellapu, S. K., Tyagi, R. D., and Drogui, P. (2020). Cost, energy and GHG emission assessment for microbial biodiesel production through valorization of municipal sludge and crude glycerol. Bioresour. Technol. 297, 122404. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122404

Lam, M. K., and Lee, K. T. (2011). “Production of biodiesel using palm oil,” in Biofuels. Editors Pandey, A., Larroche, C., Ricke, S. C., Dussap, C.-G., and Gnansounou, E. (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Academic Press), 353–374. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385099-7.00016-4

Li, H., Liu, F., Ma, X., Wu, Z., Li, Y., Zhang, L., et al. (2019). Catalytic performance of strontium oxide supported by MIL-100(Fe) derivate as transesterification catalyst for biodiesel production. Energy Convers. Manag. 180, 401–410. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2018.11.012

Mączyńska, J., Krzywonos, M., Kupczyk, A., Tucki, K., Sikora, M., Pińkowska, H., et al. (2019). Production and use of biofuels for transport in Poland and Brazil – the case of bioethanol. Fuel, 241, 989–996. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2018.12.116

Marchetti, J. M. (2011). The effect of economic variables over a biodiesel production plant. Energy Convers. Manag. 52, 3227–3233. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2011.05.008

Mardhiah, H. H., Ong, H. C., Masjuki, H. H., Lim, S., and Lee, H. V. (2017). A review on latest developments and future prospects of heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production from non-edible oils. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 67, 1225–1236. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.09.036

Moazeni, F., Chen, Y.-C., and Zhang, G. (2019). Enzymatic transesterification for biodiesel production from used cooking oil, a review. J. Clean. Prod. 216, 117–128. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.181

Parsons, S., Abeln, F., McManus, M. C., and Chuck, C. J. (2019). Techno-economic analysis (TEA) of microbial oil production from waste resources as part of a biorefinery concept: assessment at multiple scales under uncertainty. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 94, 701–711. doi:10.1002/jctb.5811

Peters, M., Timmerhaus, K., and West, R. (2003). Plant design and economics for chemical engineers. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Available at: https://catalog.lib.ncsu.edu/catalog/NCSU1640313 (Accessed February 10, 2019).

Raman, L. A., Deepanraj, B., Rajakumar, S., and Sivasubramanian, V. (2019). Experimental investigation on performance, combustion and emission analysis of a direct injection diesel engine fuelled with rapeseed oil biodiesel. Fuel 246, 69–74. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2019.02.106

Reche, C., Rivas, I., Pandolfi, M., Viana, M., Bouso, L., Àlvarez-Pedrerol, M., et al. (2015). Real-time indoor and outdoor measurements of black carbon at primary schools. Atmos. Environ. 120, 417–426. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.08.044

Santana, G. C. S., Martins, P. F., de Lima da Silva, N., Batistella, C. B., Maciel Filho, R., and Wolf Maciel, M. R. (2010). Simulation and cost estimate for biodiesel production using castor oil. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 88, 626–632. doi:10.1016/j.cherd.2009.09.015

Skarlis, S., Kondili, E., and Kaldellis, J. K. (2012). Small-scale biodiesel production economics: a case study focus on Crete Island. J. Clean. Prod. 20, 20–26. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.08.011

Tabatabaei, M., Aghbashlo, M., Dehhaghi, M., Panahi, H. K. S., Mollahosseini, A., Hosseini, M., et al. (2019). Reactor technologies for biodiesel production and processing: a review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 74, 239–303. doi:10.1016/j.pecs.2019.06.001

Tapanwong, M., and Punsuvon, V. (2019). Production of ethyl ester biodiesel from used cooking oil with ethanol and its quick glycerol-biodiesel layer separation using pure glycerol. Int. J. Geomate. 17, 109–114. doi:10.21660/2019.61.4808

United Nations (2015). Sustainable development Knowledge Platform. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/sustainabledevelopmentgoals (Accessed September 18, 2020).

Urbain, F., Du, R., Tang, P., Smirnov, V., Andreu, T., Finger, F., et al. (2019). Upscaling high activity oxygen evolution catalysts based on CoFe2O4 nanoparticles supported on nickel foam for power-to-gas electrochemical conversion with energy efficiencies above 80%. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 259, 118055. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.118055

WHO (2012). Health co-benefits of climate change mitigation - transport sector. Available at: https://www.who.int/hia/green_economy/transport_sector_health_co-benefits_climate_change_mitigation/en/ (Accessed January 26, 2019).

Yang, H.-H., Dhital, N. B., Wang, L.-C., Hsieh, Y.-S., Lee, K.-T., Hsu, Y.-T., et al. (2019). Chemical characterization of fine particulate matter in gasoline and diesel vehicle exhaust. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 19, 1439–1449. doi:10.4209/aaqr.2019.04.0191

Zaharudin, N. A., Rashid, R., Azman, L., Esivan, S. M. M., Idris, A., and Othman, N. (2018). “Enzymatic hydrolysis of used cooking oil using immobilized lipase,” in Sustainable technologies for the management of agricultural wastes applied environmental science and engineering for a sustainable future. Editor Zakaria, Z. A. (Singapore: Springer), 119–130. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-5062-6_9

Keywords: biodiesel, waste cooking oil, cement kiln dust, technoeconomic study, sensitivity analysis

Citation: Al-Sakkari EG, Mohammed MG, Elozeiri AA, Abdeldayem OM, Habashy MM, Ong ES, Rene ER, Ismail I and Ashour I (2020) Comparative Technoeconomic Analysis of Using Waste and Virgin Cooking Oils for Biodiesel Production. Front. Energy Res. 8:583357. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2020.583357

Received: 14 July 2020; Accepted: 29 September 2020;

Published: 03 December 2020.

Edited by:

Mohammad Rehan, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Muhammad Imran, Aston University, United KingdomMuhammad Amjad, University of Engineering and Technology Lahore, Pakistan

Md Mofijur Rahman, University of Technology Sydney, Australia

Copyright © 2020 Al-Sakkari, Mohammed, Elozeiri, Abdeldayem, Habashy, Ong, Rene, Ismail and Ashour. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eslam G. Al-Sakkari, ZWdvbWFhMTIzQHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==

†Present Address: Ibrahim Ismali, Energy Engineering Program, Faculty of Engineering, King Salman International University, El-Toor, Egypt.

Eslam G. Al-Sakkari

Eslam G. Al-Sakkari Mohammed G. Mohammed

Mohammed G. Mohammed Alaaeldin A. Elozeiri

Alaaeldin A. Elozeiri Omar M. Abdeldayem

Omar M. Abdeldayem Mahmoud M. Habashy

Mahmoud M. Habashy Ee Shen Ong3

Ee Shen Ong3 Eldon R. Rene

Eldon R. Rene