- State Key Laboratory of Advanced Technology for Materials Synthesis and Processing, WUT-Harvard Joint Nano Key Laboratory, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China

Since the commercialization of lithium ion batteries (LIBs) in the past two decades, rechargeable LIBs have become widespread power sources for portable devices used in daily life. However, current demands require higher energy density and power density of batteries. The electrochemical energy storage performance of LIBs could be improved by applying nanomaterial electrodes, but their fast capacity fading is still one of the key limitations and the mechanism need to be clearly understood. Single nanowire electrode devices are considered as a versatile platform for in situ probing the direct relationship between electrical transport, structure change, and other properties of the single nanowire electrode along with the charge/discharge process. The results indicate that the conductivity decrease of the nanowire electrode and the structural disorder/destruction during electrochemical reaction limit the cycling performance of LIBs. Based on the in situ observations, some feasible optimization strategies, including prelithiation, coaxial structure, nanowire arrays, and hierarchical structure architecture, are proposed and utilized to restrain the conductivity decrease and structural disorder/destruction. Further, the applications of nanowire electrodes in some “beyond Li-ion” batteries, such as Li-S and Li-air batteries are also described.

Introduction

Lithium ion batteries (LIBs), commercialized by Sony since 1991, are the most widely used electrochemical energy storage devices (Goodenough and Park, 2013; Goodenough, 2014). LIBs possess lots of desirable features, including low cost, long-life span, high energy density, good reversibility, and pollution-free operation (Dunn et al., 2011). The LIBs operate following a “rock chair” concept, in which Li-ions are extracted from the anode, diffuse through the electrolyte and intercalate into the cathode, while the discharging process is on the contrary (Tarascon and Armand, 2001; Vu et al., 2012). Therefore, the reversible capacity of LIBs is limited to the number of the exchanged ions/electrons and the material structure stability during intercalation/de-intercalation.

Rechargeable LIBs have become widespread power sources for cell phones, laptop computers, and other digital products. And LIBs have begun to enter the market of transportation and large-scale energy storage for the grid (Dunn et al., 2011; Chu and Majumdar, 2012). These numerous applications increase the demands for LIBs, such as higher energy storage density and faster charge/discharge. These requirements are especially important for further application in electric vehicles which need high power to accelerate quickly and recover energy during brake (Etacheri et al., 2011). In addition, searching for “beyond Li-ion” techniques is significant but a tough challenge (Bruce et al., 2011, 2012). Nowadays, two kinds of advanced rechargeable lithium batteries, Li-S and Li-air batteries have aroused the worldwide attention (Ji et al., 2009; Peng et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2014). Li-S batteries have been investigated for about 70 years, but the promotion of its energy storage density and cycling stability still remain to be a tough challenge (Peled et al., 1989); while non-aqueous Li-air batteries have drawn much less attention until recently due to its ultrahigh capacity, but the lack of understanding of the chemical process taking place in the cells and the discovery of new materials are main challenges for Li-air batteries (Ogasawara et al., 2006). Generally, Li-S and Li-air batteries still need further research to meet the requirements of commercialization.

The electrochemical energy storage performance of the devices depends greatly on the structure of the electrode materials (Liu et al., 2006). The developing nanoscience and nanotechnology bring new revolutionary opportunities to achieve the goals for achieving better LIBs (Yang and Tarascon, 2012). One-dimensional (1D) nanostructures, such as wires, ribbons, rods, tubes, and so forth, have been extensively studied due to their interesting and unique electronic, optical, thermal, mechanical, and magnetic properties (Dasgupta et al., 2014). For LIBs, the nanowire electrodes provide lots of benefits: (1) facilitating direct electron transport pathway to the electrode and shorter radial Li+ diffusion length (Dasgupta et al., 2014; Mai et al., 2014); (2) providing high surface area, enabling large electrolyte–electrode contact areas and reducing the charge–discharge time (Chan et al., 2007); (3) accommodating the volume expansion and restraining the mechanical degradation (Szczech and Jin, 2011); (4) nanowires have the natural geometrical advantage for in situ electrochemical probing, high-resolution structural, and electrical evolution can be investigated by building single nanowire devices with the elimination of the influences caused by non-active materials during battery operation (Huang et al., 2010; Mai et al., 2010a).

In this review, we mainly focus on the natural advantages of 1D nanostructure for advanced LIBs. In situ electrochemical probing and its recent progresses are illustrated firstly, which reveals the lithium storage mechanism of 1D nanostructure. Then, the challenges and the optimization strategies of nanowire electrodes are systematically summarized and refined. Finally, we show that nanowires also play an important role in the advanced and next-generation Li-S and Li-air batteries.

Nanowire Electrodes for LIBs: In situ Electrochemical Probing

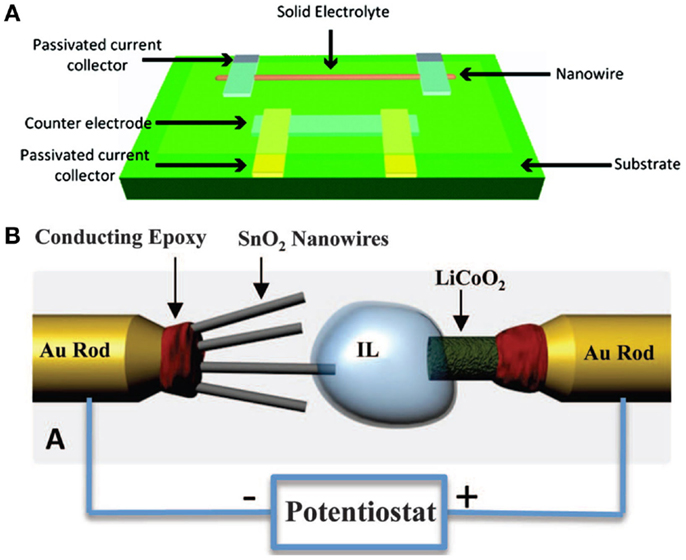

Nanowire electrodes have attracted worldwide attention, and lead to the development of rationally controlled composition, geometry, and electronic properties (Yang et al., 2010; Kempa et al., 2013). Although the energy storage performance of LIBs was improved by applying nanowire electrodes, the irreversible capacity decay is still one key limitation, to find out the intrinsic reasons of fast capacity decay and understand the structure instability of electrode materials, in situ probings have been used, such as in situ Raman spectroscopy (Mai et al., 2010a), X-ray diffraction (Li and Dahn, 2007; Wang et al., 2011b), NMR (Bhattacharyya et al., 2010; Blanc et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2013; Ogata et al., 2014), TEM (Huang et al., 2010; Liu and Huang, 2011), and so forth. These in situ techniques can provide direct observation of the cracking and fracture of 1D structure. Mai et al. (2010a) fabricated the single nanowire electrochemical devices to study the changes of vanadium oxide nanowire transport properties during the charge and discharge process. To assemble the single nanowire electrochemical device, two different working electrodes, vanadium oxide nanowire and silicon nanowire, were taken as examples. Binders or conductive carbon additives were not introduced into the systems, and the transport properties of the vanadium oxide nanowire were characterized along with the charge and discharge process (Figure 1A). The in situ observation of the single nanowire revealed that the reversible structure change could be maintained under the shallow discharge state, while the conductance of the nanowire could not be recovered after deep charging, indicating that permanent structure change happened when too many lithium ions intercalated into the vanadium oxide layered structures. These results demonstrate that the material electrical properties, crystal structure change, and electrochemical charge/discharge status are clearly correlated on the single nanowire electrode platform.

Figure 1. (A) Schematic diagram of a single nanowire electrode device design (Mai et al., 2010a). (B) Schematic of the in situ TEM setup (Huang et al., 2010). Reprinted with permission from Huang et al. (2010) and Mai et al. (2010a). Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society, 2010 AAAS.

Besides, single silicon nanowire devices were fabricated with Si/a-Si core/shell nanowires and a LiCoO2 film as the counter electrode (Mai et al., 2010a). The volume of silicon anode changed by 400% upon insertion and extraction of Li, resulted in pulverization and capacity fading. Different from the reversible conductance change of vanadium oxide nanowire, the Si nanowire exhibited a continuous decreased conductance along with the charge and discharge process. Raman spectra were measured to reveal the structure change at the single nanowire level. It showed clear red shifts and broadening because crystalline silicon lost its order and a metastable amorphous LixSi alloy formed along with the nanowire conductance degradation and the capacity fading.

Recently, the in situ TEM has been extensively used in real time observation of structural changes, phase evolution, fracture behavior, and atomic variations during lithiation/delithiation process (Huang et al., 2010; Liu and Huang, 2011). Huang et al. (2010) constructed a nanoscale electrochemical device inside a TEM, which consisted of a single SnO2 nanowire anode, ionic liquid electrolyte, and a bulk LiCoO2 cathode (Figure 1B). In situ lithiation of the SnO2 nanowire during electrochemical charging showed that a reaction front propagated progressively along the nanowire, causing the nanowire to swell, elongate, and spiral. After charge, the initially straight SnO2 nanowire became highly distorted, with a total elongation of 90% and a total volume expansion of 250%. Similar works have been done based on other electrode materials, such as coated SnO2 (Zhang et al., 2011), LiMn2O4 (Lee et al., 2013b), Si (Liu et al., 2011b), and so forth (Liu et al., 2012c).

Nanowire Electrodes for LIBs: Optimization Strategies

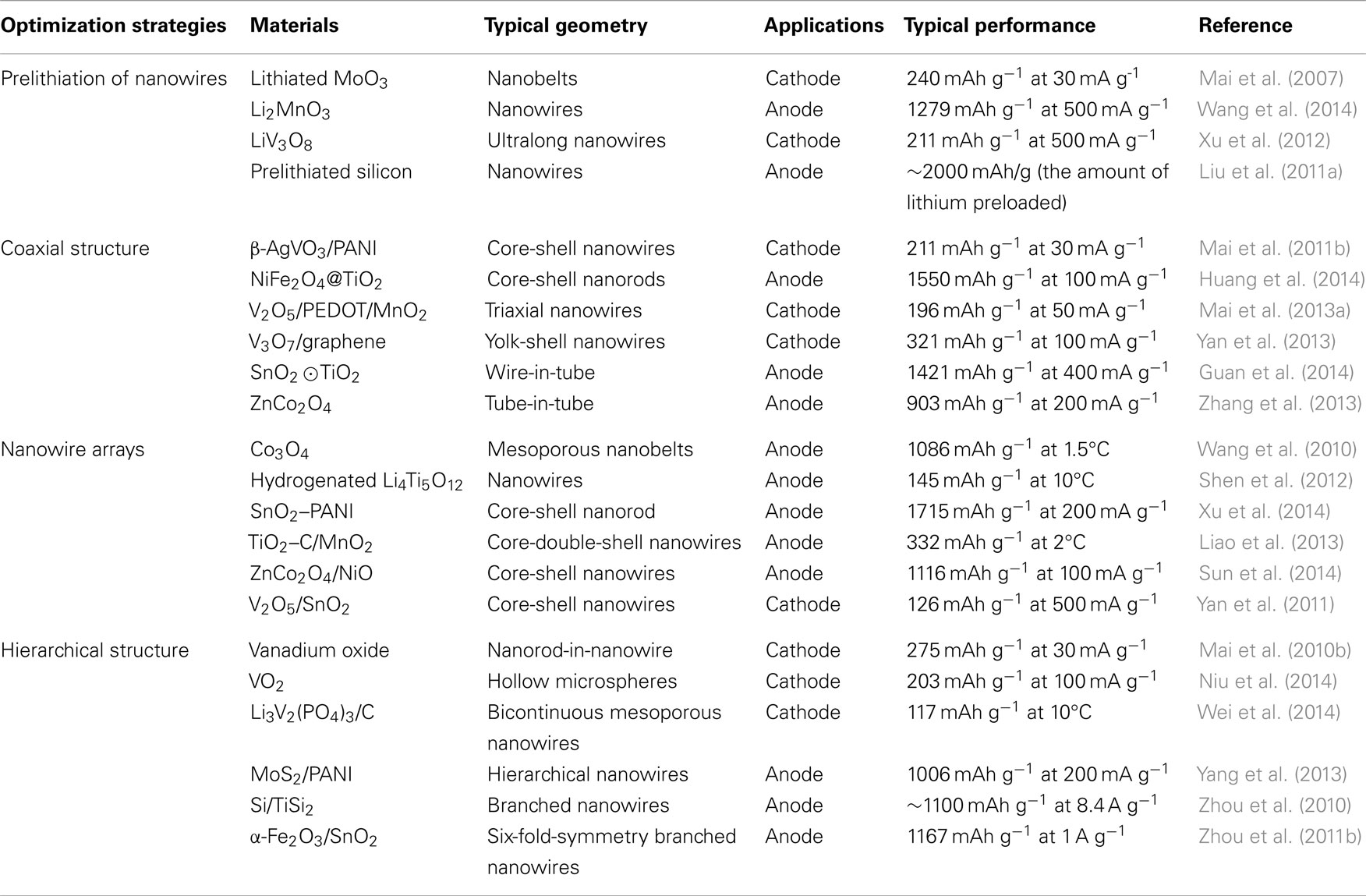

Based on the in situ observation results, the nanowire electrode conductance decrease and the structure disorder/destruction caused by phase transformation and volume change during the Li+ intercalation/de-intercalation process limit the lifetime of the devices. The key to improve the energy storage performance is to concurrently optimize electrical and ionic conductivity, and maximize the active material utilization, as well as minimizing the strain induced damage (Mai et al., 2010c, 2014; Li et al., 2014). To conquer these problems, many feasible optimization strategies have been proposed and utilized (Table 1).

Prelithiation of Nanowires

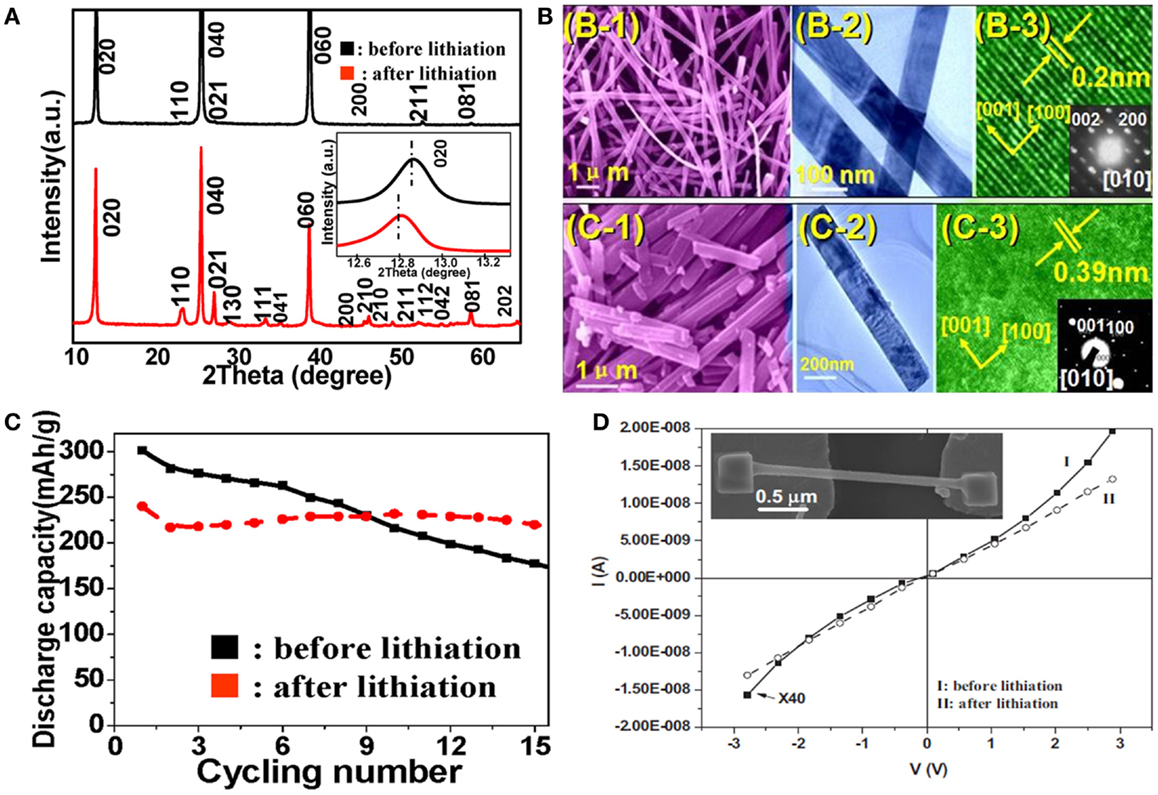

In order to restrain the conductivity decrease and structural changes of the nanowires during the lithiation/delithiation and further improve the electrochemical performance of LIBs, prelithiation is considered as a feasible method which increases the reversible capacity as well as cycling stability of the nanosized electrode materials and facilitates the Li+ diffusion because of the expanded layer space (Mai et al., 2010c; Tian et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014b). Prelithiation has been applied in Si/carbon nanotubes (Si/CNTs) (Forney et al., 2013), Si nanowires (Liu et al., 2011a), MoO3 nanobelts (Mai et al., 2007), Li2MnO3 nanowires (Wang et al., 2014), and so forth. The reversibility of the nanowire electrodes can be dramatically improved by controlling the amount of Li applied in the prelithiation process or enhancing lithiation reaction (Zhang et al., 2014b). The hydrothermally synthesized α-MoO3 nanobelts were successfully lithiated by a secondary reaction with LiCl solution while retaining their crystal structure and surface morphology (Figures 2A,B) (Mai et al., 2007). The lithiated MoO3 nanobelts exhibited excellent cycling capability, with a capacity retention rate of 92% after 15 cycles, while the non-lithiated nanobelts retained only 60% (Figure 2C). Transport measurements were increased by nearly two orders of magnitudes compared to that of a non-lithiated MoO3 nanobelt (10–4 S cm–1), suggesting that Li ions were introduced into the MoO3 layers during lithiation (Figure 2D). Electrode materials abiding a conversion reaction can achieve large capacity, but the fast capacity fading is an obstacle that affect its promising application. The lithium compounds, mostly Li2O and Li2S, generated in the interior of materials in the lithiation process can cause large volume expansion and mechanical fracturing. To overcome this limitation, the prelithiated Li2MnO3 nanowire was obtained by the lithiation of MnO2 nanowire (Wang et al., 2014). The reversible capacity can reach 1279 mAh g−1 at a current density of 0.5 A g−1 after 500 cycles, much higher than those of pure MnO2 nanowires and other commercial anode materials. The prelithiation of MnO2 nanowires buffered the structure changes and provided a new method for achieving better conversion reaction materials.

Figure 2. (A) X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of α-MoO3 nanowire before and after lithiation. The inset is the corresponding (020) diffraction peak. (B) SEM, TEM, and HRTEM characterization of the nanowire before and after lithiation, respectively. The insets in the HRTEM images are the corresponding selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns. (C) The cycling performance of the MoO3 nanobelts before and after lithiation. (D) Transport measurements of single MoO3 nanobelt before and after lithiation. Reprinted with permission from Mai et al. (2007). Copyright 2007 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Besides, ultralong LiV3O8 nanowires have been synthesized by topotactic lithiation of H2V3O8 nanowires (Xu et al., 2012). The LiV3O8 nanowire cathode showed excellent high-rate capability and cycling stability. The excellent performance can be attributed to the low-charge-transfer resistance, good structural stability, large surface area, and suitable degree of crystallinity. The prelithiation of CNTs and Si nanowires also demonstrated an inhibitory effect on the formation of solid electrolyte interface (SEI) layer, leading to a less irreversible capacity loss and good cycling performance (Liu et al., 2011a; Forney et al., 2013). The prelithiation technology reveals a potential application in constructing better nanowire electrodes.

Coaxial Structure

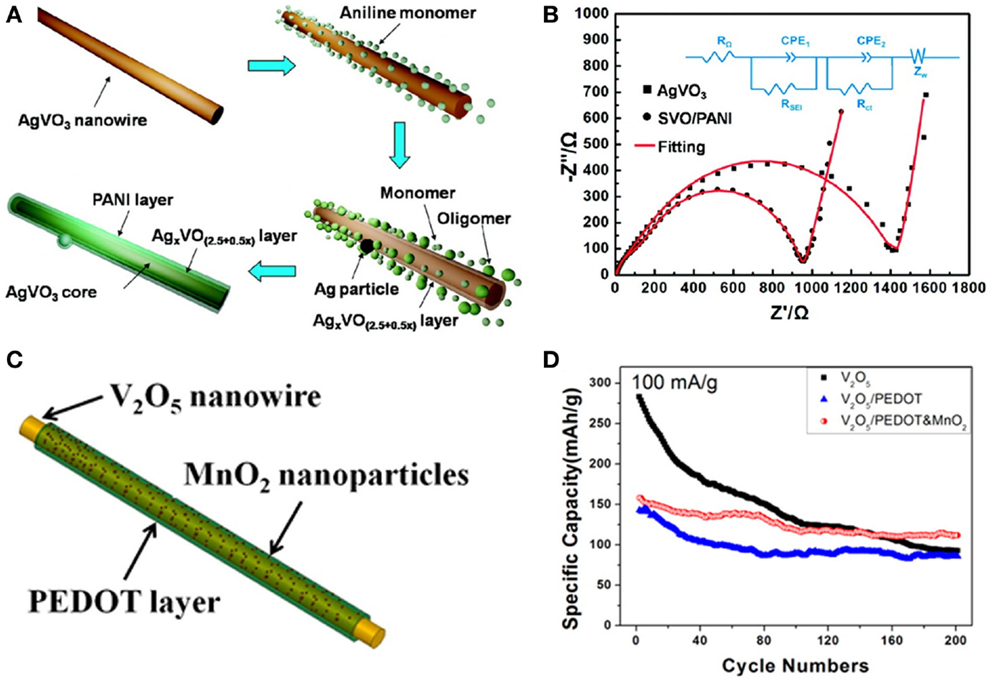

Coaxial structures contain two categories: core-shell and yolk-shell structures. Core-shell structures refer to inner core surrounded by other materials as shell. Generally, the core is the major component with functional properties, while the outer shell acts as a protection layer to strengthen the core performances or to bring new properties (Su et al., 2011; Mai et al., 2013b). The shell layer should be permeable to lithium ions, thus the diffusion of lithium ions in the active materials can be maintained. The core-shell structures possess many desirable properties: (1) protecting the core from outside environmental changes and reducing the side reactions; (2) restricting volume expansion and maintaining the structural integrity; (3) preventing the core from aggregating into large particles. Conductive polymers and carbonous materials are usually chosen as the coating layers, because their high conductivity increases the electron transfer and high flexibility can release the internal strain during the intercalation of Li ions (Liu et al., 2010; Li and Zhou, 2012). The β-AgVO3/PANI nanowires were synthesized by in situ chemical oxidative polymerization and interfacial redox reaction based on the β-AgVO3 nanowires (Figure 3A) (Mai et al., 2011b). The β-AgVO3/PANI nanowires showed better performance compared with the pure β-AgVO3 nanowires. The AC-impedance test demonstrated that β-AgVO3/PANI nanowires exhibited much lower resistance and faster kinetics than those of β-AgVO3 nanowires (Figure 3B). Similar structure, such as MoO3/PTh (Li et al., 2011), MnO2/CNT (Reddy et al., 2009), polymer/Si (Fobelets et al., 2012), Si/C (Cui et al., 2009; Tao et al., 2013), and Fe3O4/C (Xiong et al., 2012) nanowires, also showed superior advantages in terms of electrical conductivity, mechanical stability, and electrochemical performances. The utilization of two active materials for architecting the core-shell nanowires has also been studied (Huang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014a). The core-shell NiFe2O4@TiO2 nanorods showed highly reversible capacity, outstanding rate capability, and remarkable cycling stability (Huang et al., 2014). The improved electrochemical performance was attributed to the heterostructure and the synergistic effect of NiFe2O4 and TiO2.

Figure 3. (A) Schematic illustration of the formation of β-AgVO3/PANI triaxial nanowire. (B) AC-impedance spectra of β-AgVO3 nanowires and SVO/PANI triaxial nanowires (Mai et al., 2011b). (C) Schematic illustration of the synthesis of V2O5/PEDOT&MnO2 NWs. (D) Electrochemical properties of V2O5 NWs, V2O5/PEDOT NWs, and V2O5/PEDOT&MnO2 NWs (Mai et al., 2013a). Reprinted with permission from Mai et al. (2011b) and Mai et al. (2013a). Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society, and 2013 American Chemical Society.

Moreover, by constructing the Li-ions adsorptive outer layer, the fast diffusion of Li ions can be maintained. Such as the V2O5/PEDOT/MnO2 triaxial nanowire (Mai et al., 2013a), the MnO2 nano-particles on the outer surface can adsorb Li-ions on the electrode surface from electrolyte and provide certain intercalation and de-intercalation of Li-ions, leading to the promotion on the capacity retention (Figures 3C,D).

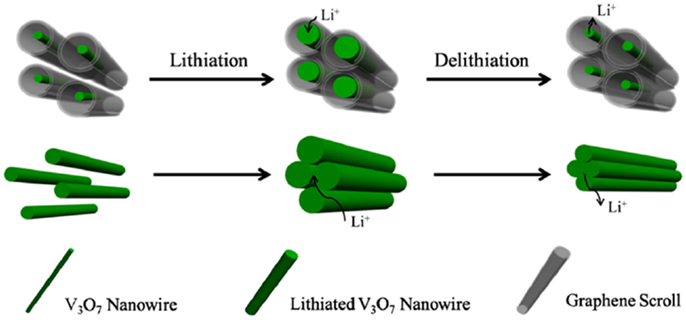

Different from the core-shell structure, the yolk-shell structure owns a void space between the core and shell layer, leaving the room to accommodate the volume expansion during the intercalation of Li+, which can provide spare space for the expansion of electrode materials (Liu et al., 2012b; Hong et al., 2013; Seh et al., 2013). Graphene possesses great mechanical stiffness, strength and elasticity, very high electrical and thermal conductivity, and large surface area (Zhu et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2013a). The outstanding properties of graphene have motivated intensive efforts to construct graphene-based materials, but the graphene encapsulated yolk-shell nanowires were seldom reported. V3O7 nanowire template semihollow bicontinuous graphene scrolls (VGSs) were fabricated by hydrothermal methods (Yan et al., 2013). The VGSs offered a unique combination of ultralong 1D graphene scrolls with semihollow structure and space confining effect for the nanowires without self-aggregation during cycling, thus allowing for a greater lithium ion storage capacity and stability. The unique structure of VGS provided space for the volume expansion and showed the space confining effect for inhibiting the agglomeration of V3O7 nanowire, thus leading to remarkable electrochemical properties. And the graphene can increase the conductivity of the nanowires electrode and promote the charge transfer, leading to better rate capability (Figure 4). Similarly, the hollowed wire-in-tube structure SnO2 ⊙ TiO2 was fabricated the by atomic layer deposition (Guan et al., 2014), the outstanding performance of SnO2 ⊙ TiO2 were attributed to the simultaneously stabilization of the SEI and accommodation of the volume expansion of the SnO2 core wire. Moreover, the tube-in-tube ZnCo2O4 and the peapods like MnO/CNTs were also fabricated, which demonstrated both high energy storage density and cycling stability (Zhang et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2014).

Figure 4. Schematic of the VGS nanoarchitecture with continuous electron and Li-ion transfer channels. Reprinted with permission from Yan et al. (2013). Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

Nanowire Arrays

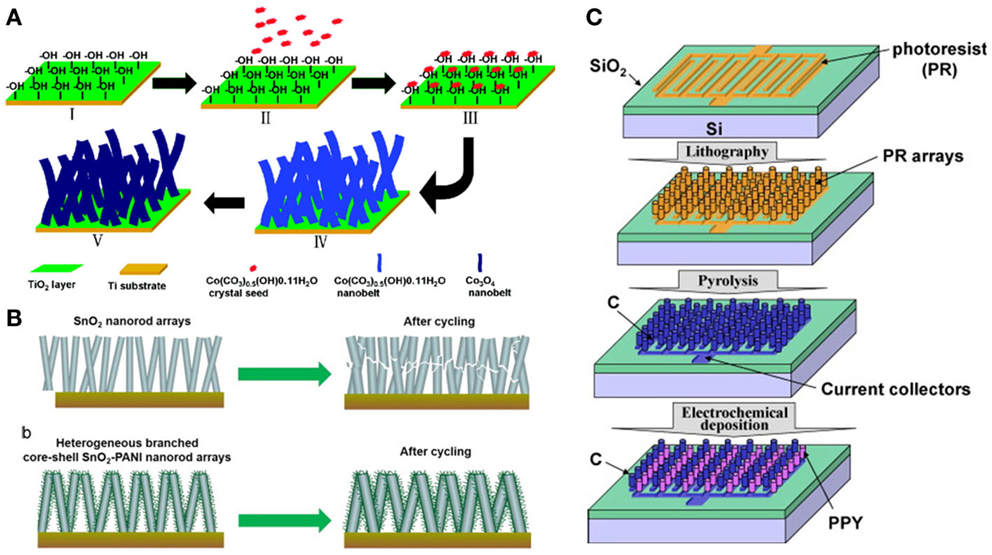

The small size of nanowire in the radial direction can restrain the stresses during the Li+ intercalation/de-intercalation. But nanowires may agglomerate due to their large surface area and high surface energy, which may lead to low conductivity, a high level of irreversibility, and poor cycle life, while nanowire arrays aligned on conductive substrates can prevent the direct contact between the nanowires and provide free space for the strain relaxation during the cycling, leading to a better cycling performance (Song et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2012d; Li et al., 2014). Moreover, nanowire arrays ensure the direct and full contact with the electrolyte and avoid the addition of non-conductive binders, nanowire attached to current collector can form the pathways for electrons and promote the rate capability. Wang et al. (2010) synthesized mesoporous Co3O4 nanobelt arrays rationally on Ti foil through the conversion from Co(CO3)0.5(OH)0.11H2O nanobelt arrays (Figure 5A), the discharge capacity of the first cycle was approximately 1086.1 mAh/g under the rate of 1.5 C and 88.6% of the theoretical capacity after 25 cycles. To increase the intrinsic conductivity of the nanowires, self-supported hydrogenated Li4Ti5O12 nanowire arrays (H-LTO NAWs) were fabricated on Ti foil (Shen et al., 2012), it can deliver a relatively high capacitance and 5% capacity loss after 100 cycles at a rate of 5 C, revealing a good cycle performance at high current density. Besides the fully utilization of homogeneous nanowire materials, the synergistic promotion of different electrode materials were also been proposed, such as ZnCo2O4/NiO core-shell nanowire arrays (Sun et al., 2014), Sn/TiO2 nanowire arrays (Wei et al., 2013), TiO2–C/MnO2 core-double-shell nanowire arrays (Liao et al., 2013), Co3O4/NiO/C nanowire arrays (Wu et al., 2014), CoO–CoTiO3 nanotube arrays (Jiang et al., 2013), and so forth. To maintain the structure stability and facilitate the electron transport, the conductive polymer and carbon coating of the nanowire have also been reported. Xu et al. (2014) synthesized heterogeneous SnO2–PANI core-shell nanorod arrays by using hydrothermal treatment followed by electrodeposition (Figure 5B). The SnO2–PANI nanorod arrays offered strong adhesion between the SnO2 nanorod core and the conducting PANI shell, leading to excellent structural stability and mechanical integrity, and also realized fast kinetics, resulting in prolonged cycling stability and enhanced rate capability. Moreover, the nanowire arrays have a potential in high-performance flexible LIBs by utilizing stretchable/bendable substrates (Zhou et al., 2014). The ZnCo2O4 nanowire arrays on carbon cloth were synthesized by Liu et al. (2012a), and full batteries were fabricated based on the flexible ZnCo2O4 nanowire arrays. The full battery exhibited an outstanding performance in both rate capability and cycling stability, and it still demonstrated superior electrochemical performance over conventional electrode under fully mechanical bending. This revealed the possible applications of nanowire arrays in portable/wearable energy storage devices, electronic devices, and flexible powering for devices. Other similar architectures have also been reported, such as Li4Ti5O12–C nanotube arrays (Liu et al., 2014), SnO2@Si core-shell nanowire arrays (Ren et al., 2013), and so forth.

Figure 5. (A) Schematic illustration for the whole synthetic procedure of mesoporous Co3O4 nanobelt array (Wang et al., 2010). (B) Schematic illustrations of heterogeneous core-shell SnO2–PANI nanorod arrays during cycling (Xu et al., 2014). (C) Procedure for fabricating the carbon/polypyrrole three-dimensional battery (Min et al., 2008). Reprinted with permission from Wang et al. (2010), Xu et al. (2014), and Min et al. (2008). Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society, 2014 Elsevier B.V., and 2007 Elsevier B.V.

The three-dimensional (3D) configurations of nanowire arrays have also been increasingly investigated as power sources for micro-/nano-electromechanical systems (MEMS/NMES) devices (Hart et al., 2003). Min et al. (2008) reported the 3D Li-ion batteries consisting of arrays of carbon posts interdigitated with arrays of PPYDBS posts using the C-MEMS process (Figure 5C). With the 3D array configuration, the electrolyte penetrated the entire electrode as compared to the planar front that the electrolyte makes with the 2D PPYDBS electrode. The electrochemical measurements showed that 3D PPYDBS array electrode exhibited reversible intercalation/de-intercalation with better gravimetric capacity than the electrodeposited 2D films. It further demonstrated that the 3D configuration made use of the out-of-plane dimension in contrast to traditional thin-film battery electrodes, which used only the in-plane surface.

Hierarchical Structure

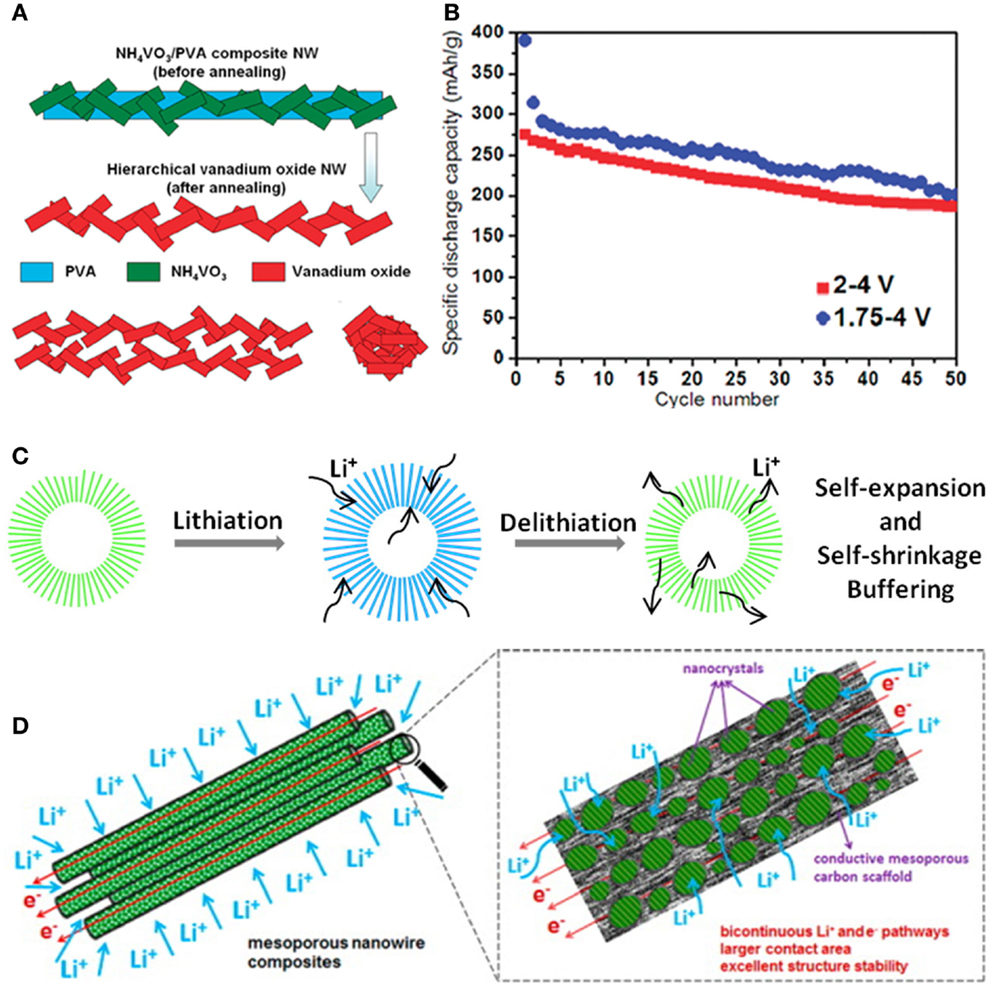

The enhanced electrochemical performance of electrodes depends on not only the intrinsic characteristics of materials, but also the designed morphologies (Mai et al., 2011a; Li et al., 2014). Owing to the high surface energy, nanomaterials are often self-aggregated, which reduces the effective contact areas between active materials and electrolyte. To keep the effective contact areas of active materials and fully realize the advantages of nanomaterial-based cathodes, the hierarchical nanowire structure is a representative strategy (Chen et al., 2009; Cheng and Fan, 2012; Zhang et al., 2014c). Ultralong hierarchical vanadium oxide nanowires with diameter of 100–200 nm and length up to several millimeters were synthesized by electrospinning combined with annealing. The hierarchical nanowires were constructed from attached vanadium oxide nanorods of diameter around 50 nm and length of 100 nm (Figure 6A) (Mai et al., 2010b). The self-aggregation in the unique “nanorod-in-nanowire” structures could be reduced because of the attachment of nanorods in the ultralong nanowires, which kept the effective contact areas of active materials and fully realized the advantages of nanomaterial-based cathodes. When the battery was cycled between 2.0 and 4.0 V, the initial and 50th discharge capacities of the nanowire cathodes were 275 mAh g−1 and 187 mAh g−1, which were much higher than self-aggregated short nanorods (with a discharge capacity of 110–130 mAh g−1) (Figure 6B). Developing 3D nanostructures with high surface area and excellent structural stability is an important approach for realizing high-rate and long-life battery electrodes (Haag et al., 2013; Nethravathi et al., 2013). Hollow microspheres assembled with VO2 nanowires, constructed through a facile controllable ion-modulating approach, exhibited high capacity and excellent cyclability due to their high surface and efficient self-expansion and self-shrinkage buffering (Niu et al., 2014). This structure can accommodate the volume variation, release the strain during Li+ intercalation/de-intercalation, and effectively inhibit the self-aggregation of nanowires (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. (A) Schematic illustration of formation of the ultralong hierarchical vanadium oxide nanowires. (B) Cycling performance of the ultralong hierarchical vanadium oxide nanowires (Mai et al., 2010b). (C) Schematic of VO2 hollow microspheres structure during lithiation and delithiation (Niu et al., 2014). (D) Schematic illustration of the (LVP/C-M-NWs) with bicontinuous electron/ion transport pathways, larger electrode–electrolyte contact area, and facile strain relaxation during Li+ extraction/insertion (Wei et al., 2014). Reprinted with permission from Mai et al. (2010b), Niu et al. (2014), and Wei et al. (2014). Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society, 2014 American Chemical Society, and 2013 American Chemical Society.

Considering about both ion and electron transport, the bicontinuous hierarchical Li3V2(PO4)3/C mesoporous nanowires (LVP/C-M-NWs) were synthesized by one pot method (Wei et al., 2014). Such novel LVP/C-M-NWs architecture provided bicontinuous electron/ion pathways and large electrode/electrolyte contact area for rapid Li+ diffusion and electron transport. Meanwhile the robust structure stability facilitated the strain relaxation upon prolonged cycling (Figure 6D). As a cathode for LIB, the LVP/C-M-NWs exhibited outstanding high-rate and ultralong-life performance with capacity retention of 80.0% after 3000 cycles at 5 C. Even at 10 C, it still delivers 88.0% of its theoretical capacity.

Besides the self-aggregation restriction and conductance improvement, the fabrication of branched heterostructural nanowires can be considered as a feasible method to enhance the energy storage performance (Zhou et al., 2011a; Yang et al., 2013). Branched nanowires can reduce the aggregation and provide more lithium diffusion pathways as well as enhanced electronic conductivity. Moreover, the heterostructures are more complicated form of exterior design and provide better cycling stability and capability due to the synergistic effect of the backbone and branch materials, which means combining the characteristics and advantages of different electrode materials. The branched Si/TiSi2 nano-heterostructural nanowires utilized the high conductivity and structural integrity of the inner inactive core to permit reproducible Li+ insertion and extraction into and from the outer Si coating (Zhou et al., 2010). In this structure, Si acted as an active component to store and release Li+ while TiSi2 served as the inactive component to support Si and to facilitate charge transport. The differences between their electrochemical potentials in reacting with Li+ permitted the selection of the operation potentials to keep TiSi2 intact, resulting in a good cycling stability. Zhou et al. (2011b) reported the synthesis of a novel sixfold-symmetry branched nano-heterostructure composed of SnO2 nanowire backbone and α-Fe2O3 nanorod branches by combining a vapor transport deposition and a facile hydrothermal method. The branched nano-heterostructures showed a remarkably improved initial discharge capacity of 1167 mAh/g, which was almost twice the SnO2 nanowires (612 mAh/g) and α-Fe2O3 nanorods (598 mAh/g). Moreover, the composite electrode also exhibited the best initial capacity retention of 69.4%, compared to 56.1% for α-Fe2O3 nanorods, and 43.6% for SnO2 nanowires. The improvement could be ascribed to a synergetic effect between α-Fe2O3 and SnO2 as well as the unique feature of branched nanostructures, which provided increased specific surface areas.

Nanowire Electrodes for Next-Generation Lithium Batteries

The energy density of LIBs increases rapidly in recent years, but it still cannot meet the growing needs. Thus, there are demands on some “beyond Li-ion” battery technologies, which can provide sufficient energy storage capacity. The Li-S and Li-air batteries seem to be the most promising battery technologies that could provide significantly enhanced energy storage capability. Therefore, there have been strong interests in Li-S and Li-air battery technologies around the world in recent years.

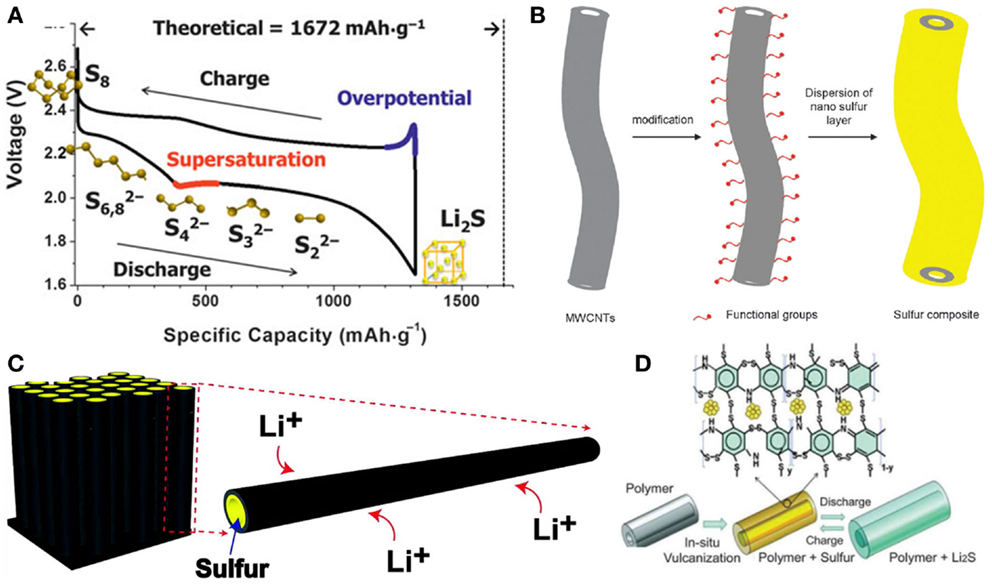

Li-S batteries have attracted much attention recently because of its high theoretical gravimetric (2500 Wh kg−1) and volumetric (2800 Wh L−1) energy density and an order of magnitude higher capacity (1675 mAh g−1) than that of the conventional LIBs (Manthiram et al., 2012; Yin et al., 2013). During the discharge process of Li-S batteries, the sulfur–sulfur bonds are cleaved to open S8 ring, forming various polysulphides that combine with Li+ to ultimately produce Li2S (Figure 7A) (Nazar et al., 2014). After decades of development, the Li-S batteries still cannot meet the requirements of mass production and commercialization. There are several problems that limit the development of Li/S batteries. Firstly, the volume changes of sulfur particles during discharge/charge lead to pulverization of active materials and thus capacity decay. Secondly, the insulativity of sulfur and Li2S cause low electrochemical rates. Thirdly, the internal shuttle phenomenon, causing by the soluble polysulfides, leads to an irreversible capacity loss and low Coulomb efficiency.

Figure 7. (A) Schematic illustration of Li-S battery and its initial discharge and charge cycle (Nazar et al., 2014). (B) Illustration of MWCNT surface groups affecting the dispersion of a nano-sulfur layer (Chen et al., 2012). (C) Schematic of design of hollow carbon nanofibers/sulfur composite structure (Zheng et al., 2011). (D) Schematic illustration of the construction and discharge/charge process of the S-PANI-NT composite (Xiao et al., 2012). Reprinted with permission from Zheng et al. (2011), Chen et al. (2012), Nazar et al. (2014), and Xiao et al. (2012). Copyright 2014 Materials Research Society, 2012 The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2011 American Chemical Society, and 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

To resolve the problems mentioned above, efforts have been paid to construct nanowire structure based sulfur cathodes (Wang et al., 2011a; Yang et al., 2011, 2014; Seh et al., 2013). Considering the low conductivity of sulfur and the discharge production Li2S, the carbonous materials and conductive polymers were the most widely used in Li-S batteries. Multiwalled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) is a good choice for 1D sulfur composite synthesis (Figure 7B) (Chen et al., 2012). Sulfur was uniformly coated on the surface of modified MWCNTs by the solvent exchange method to form a typical nanoscale core-shell structure with a sulfur layer of thickness 10–20 nm. The nanostructure of the S/MWCNT could shorten the electron and ion transport path, resulting in a high interface kinetics and reaction activity. But this structure architecture may not effectively decrease the polysulfides dissolution. Sulfur-impregnated disordered carbon nanotubes (SDCNTs) were fabricated by Guo et al. (2011). The SDCNTs were treated under high temperature heat treatment in a vacuum environment, and the heat treatment could break down the S8 molecule to S6 or S2 and enable S–C bonding so that the conventional Li-S8 reaction with dissolvable polysulfide intermediate products might be restricted. Zheng et al. (2011) used 1D carbon nanostructures as a sulfur holder. Hollow carbon nanofibers with a high aspect ratio are effective in trapping sulfur. This structure provided shortened conductive pathways for both electronic and ionic transport, favoring higher reaction kinetics (Figure 7C). The one-dimensional carbon wall was a closed structure for polysulfide containment. Electrochemical test showed that this kind of sulfur cathode with around 75% sulfur loading delivers an initial capacity of around 1400 mAh g−1, retaining a reversible capacity of around 730 mAh g−1 after 150 cycles. Self-assembled polyaniline nanotubes (PANI-NT) were reported to encapsulate sulfur by a soft approach (Figure 7D) (Xiao et al., 2012). A fraction of S reacted with the PANI to form S–C bonds forming an interconnected structure. This framework provided strong physical and chemical restriction to the molecule S and the resident polysulfide. Compared to nanoscale encapsulation by porous carbon, it also provides a molecular level flexible capsule to contain sulfur compounds. The S–PANI-NT exhibited an initial capacity of 755 mAh g−1 at 0.1 C, but the capacity increased in the next few cycles. It can be attributed to the low surface area of the composite that initially did not allow electrolyte to penetrate the full structure.

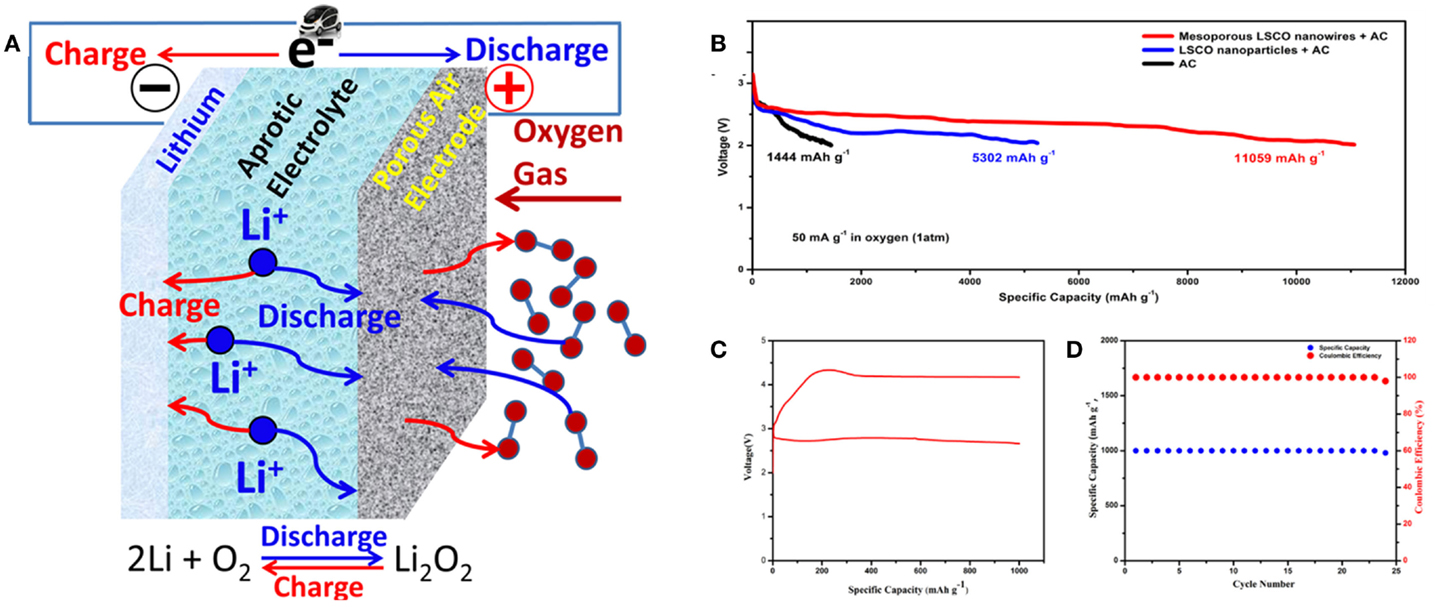

The Li-air battery consists of Li anode, a cathode with catalytic activity and non-aqueous aprotic electrolyte, during the discharge process, O2 enters the porous cathode, solvates into the electrolyte within the pores and is reduced to peroxy ion at the electrode surface on discharge forms Li2O2 as the discharge product along with Li+ from the electrolyte, which is the so called oxygen reduction reaction (ORR). The Li2O2 is then decomposed on charge process, which is so called oxygen evolution reaction (OER) (Figure 8A) (Girishkumar et al., 2010; Cheng and Chen, 2012; Lu et al., 2014). Since the electrochemical active cathode material, oxygen, is absorbed from the environment by catalytic reactive sites on the air electrode rather than stored in the battery, the Li-air battery can provide a high energy density. However, lots of important issues still need to be conquered to make the Li-air battery truly rechargeable: (1) the poor rechargeability and low rate capability lead to a very high overpotential between the charge and discharge (Bruce et al., 2012; Shao et al., 2012); (2) the precipitation of reaction products on the catalyst electrode eventually blocks the oxygen pathway and limits the capacity and cycle performance of the Li-air batteries (Zhao et al., 2012; Itkis et al., 2013); (3) the elimination of the byproducts, Li2CO3 or lithium carboxylates, related to the decomposition of the electrolyte decomposition (Freunberger et al., 2011; Itkis et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2014). Therefore, it is important to develop an electrode that can provide continuous transport channels for both oxygen and electron further lowering the overpotentials. Nanowires are a good choice of enhancing catalytic and cycling properties in Li-air batteries according to intensive research, such as CNTs (Li et al., 2013; Lim et al., 2013), MnO2 nanowires (Débart et al., 2008), La0.5Sr0.5CoO2.91 mesoporous nanowires (Zhao et al., 2012; Shi et al., 2013), La0.5Sr0.5MnO3 porous nanotubes (Xu et al., 2013), and so forth.

Figure 8. (A) Structure of the rechargeable Li-air batteries containing a catalyst (Lu et al., 2014). (B) Discharge curve of Li-air batteries. (C,D) Charge/discharge curve and cycling performance of Li-air batteries (Shi et al., 2013). Reprinted with permission from Lu et al. (2014) and Shi et al. (2013). Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society, and 2013 by ESG.

Porous nanowires could be directly utilized as the high efficient catalysts of Li-air batteries due to its highly surface area, better electronic conduction, and continuous oxygen diffusion channels (Aáwebley, 2009). The hierarchical mesoporous perovskite structure La0.5Sr0.5CoO2.91 (LSCO) nanowires were fabricated by Zhao et al. (2012), the hierarchical mesoporous LSCO nanowires exhibited ultrahigh capacity over 11,000 mAh g–1, with the improvement of one order of magnitude than LSCO nano-particles (Figure 8B). And 25 charge/discharge cycles with stable specific capacity of 1000 mAh g−1 were achieved in follow-up work (Figures 8C,D) (Shi et al., 2013). LSCO nanorods were tightly attached to each other at atomic level when they formed the hierarchical nanowire. This structure provided continuous oxygen diffusion channels that contributed to its electrocatalytic performance. Similar perovskite-based porous La0.75Sr0.25MnO3 nanotubes (PNT-LSM) were prepared by combining the electrospinning technique with a heating method (Xu et al., 2013). The synergistic effect of the high catalytic activity and the unique hollow channel structure of the perovskite-based porous La0.75Sr0.25MnO3 nanotubes electrocatalyst maximized the availability of the catalytic sites and facilitated the diffusion of electrons and reactants, which endowed the Li-air battery with a high specific capacity, superior rate capability, and good cycling stability.

Besides the metal oxide catalyst electrode material, porous carbon is chosen as air electrode material for almost all the Li-O2 batteries (Xiao et al., 2011; Jung et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2014). Carbonous materials possess great mechanical stiffness, strength and elasticity, very high electrical and large surface area, and it is identified to achieve the highest specific capacity due to its low mass of the electrode. CNTs can provide large surface area for Li2O2 deposition as well as efficient oxygen and electron transportations, facilitating the formation/decomposition of Li2O2. Mitchell et al. (2013) reported the electrochemical performance was related to the nucleation and growth process for Li2O2 on CNTs, at low current density, electrochemically grown Li2O2 demonstrated a disk-like shape, by increasing the current density, the Li2O2 evolved to a toroid-like shape, and finally turned into Li2O2 particles, and the cyclability decreased with the increasing size. This showed that the morphology of Li2O2 had an important influence on the electrochemical performance of Li-air battery. However, due to the low ORR and OER catalytic efficiency of pristine CNTs and the unstable surface of carbonous materials (Gong et al., 2009; Itkis et al., 2013), the Li-air batteries often reveal a relative high overpotentials and forms by-product on the surface of CNTs. In order to overcome these problems, the doped carbonous materials and the combination of other materials are applied. The vertically aligned N-doped coral-like carbon fiber arrays were applied in Li-air battery (Shui et al., 2014). The Li-air batteries demonstrated an energy efficiency as high as 90% in a full discharge/charge cycle and low overpotential of only 0.3 V between the charge/discharge plateaus. The battery showed no capacity decay within the 150 cycles with the controlled capacity 1000 mAh/g, revealing a good cyclability of the vertically aligned N-doped coral-like carbon fiber arrays based Li-air battery. The observed outstanding battery performance resulted from multiple factors, including the N-doping-induced high ORR and OER catalytic activity, facilitating Li2O2 deposition along the VA-NCCF fibers, the unique 3D structure to provide a large free space for efficient Li2O2 deposition and enhanced electron/electrolyte/reactant transport.

Conclusion

Compared to the bulk or micro-sized electrode, the nanowire structure can provide a much higher surface area, more reactive sites, 1D electron transport as well as facile strain relaxation. Based on the observed results of single nanowires devices, the capacity fading possesses a direct relationship between electrical transport, structure, and electrochemistry of nanowire electrode materials. To improve their electrochemical performances, some optimization strategies are proposed, (1) prelithiation: modifying the electrochemical performance of nanowires from the intrinsic properties; (2) coaxial structure: maintaining the structure stability of materials; (3) nanowire arrays: preventing the agglomeration and facilitating the transport of both Li+ and electrons; and (4) hierarchical structure: realizing the modification on conductivity, the structure stability, Li+ and electrons transport.

The design and synthesis of structurally stable nanowire electrode materials with high electron and ion conductivity show the potential to reach both small-/large-scale applications. It can be anticipated that, the utilization of nanowire structures in the integration of micro-/nano-batteries will become an emerging and important technique with a range of novel functional electronic and mechanical micro-devices. And with the development of assembly techniques, the novel flexible, wearable, transparent energy storage devices will be deeply developed. The evolution of nanoarchitectures will be important research features in the future years, which will impact many fields and open up a whole new area in future.

In addition, nanowires are expected to have more applications in Li-S and Li-air batteries, but to further promote the elecrochemical energy storage performance some modifications still need to be made on the nanowires. For the Li-S battery, the main problem which needs to be conquered is the shuttle phenomenon causing by dissolution of the Li2Sx (2 < x < 8), and it may be solved by constructing micropores nanowires to store the sulfur with a small molecular form, which can directly combine with Li+ to form the Li2S or Li2S2 without the intermediate Li2Sx (2 < x < 8). And Li-S battery also suffers from severe volume expansion leading to the collapse of the shell layer, thus, leaving a void space between the shell layer and the S core may be necessary. Moreover, the 1D coaxial structure electrodes for Li-S batteries need to be further developed, especially in the applications of flexible, bendable and wearable devices. For Li-air battery, the nanowire electrode serves as an ORR/OER catalyst and the deposition platform for Li2O2. To further improve the electrochemical energy storage of Li-air battery, there are still some tips which can be chosen (1) synthesize high catalytic activity, conductive, and porous nanowires electrode to facilitate the O2 and electron transportations to further favor the fast formation/decomposition of Li2O2 and lower the overpotential of Li-air battery between charge and discharge; (2) modify the surface of nanowires, such as decorated with noble metal nano-particles/dots, tailoring the morphology of Li2O2 to a small size. Since the Li-S and Li-O2 batteries are still under further development, more intensive researches must be devoted to address the problems.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (2013CB934103 and 2012CB933003), the International Science & Technology Cooperation Program of China (2013DFA50840), The National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars, National Natural Science Foundation of China (51072153 and 51272197), the Hubei Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (2014CFA035) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2014-yb-01, 2013-KF-4, 2013-VII-028, and 2013-ZD-7). We are deeply thankful to Prof. C. M. Lieber of Harvard University, Prof. Dongyuan Zhao of Fudan University, and Prof. Jun Liu of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory for their stimulating discussion and kind help.

References

Aáwebley, P. (2009). Porous platinum nanowire arrays for direct ethanol fuel cell applications. Chem. Commun. 45, 195–197. doi: 10.1039/b813830c

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bhattacharyya, R., Key, B., Chen, H., Best, A. S., Hollenkamp, A. F., and Grey, C. P. (2010). In situ NMR observation of the formation of metallic lithium microstructures in lithium batteries. Nat. Mater. 9, 504–510. doi:10.1038/nmat2764

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Blanc, F., Leskes, M., and Grey, C. P. (2013). In situ solid-state NMR spectroscopy of electrochemical cells: Batteries, supercapacitors, and fuel cells. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 1952–1963. doi:10.1021/ar400022u

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bruce, P. G., Freunberger, S. A., Hardwick, L. J., and Tarascon, J.-M. (2012). Li-O2 and Li-S batteries with high energy storage. Nat. Mater. 11, 19–29. doi:10.1038/nmat3191

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bruce, P. G., Hardwick, L. J., and Abraham, K. (2011). Lithium-air and lithium-sulfur batteries. MRS Bull. 36, 506–512. doi:10.1557/mrs.2011.157

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chan, C. K., Peng, H., Liu, G., Mcilwrath, K., Zhang, X. F., Huggins, R. A., et al. (2007). High-performance lithium battery anodes using silicon nanowires. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 31–35. doi:10.1038/nnano.2007.411

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, J.-J., Zhang, Q., Shi, Y.-N., Qin, L.-L., Cao, Y., Zheng, M.-S., et al. (2012). A hierarchical architecture S/MWCNT nanomicrosphere with large pores for lithium sulfur batteries. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 5376–5382. doi:10.1039/c2cp40141j

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, Z., Qin, Y., Weng, D., Xiao, Q., Peng, Y., Wang, X., et al. (2009). Design and synthesis of hierarchical nanowire composites for electrochemical energy storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 19, 3420–3426. doi:10.1002/adfm.200900971

Cheng, C., and Fan, H. J. (2012). Branched nanowires: synthesis and energy applications. Nano Today 7, 327–343. doi:10.1016/j.nantod.2012.06.002

Cheng, F., and Chen, J. (2012). Metal-air batteries: from oxygen reduction electrochemistry to cathode catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 2172–2192. doi:10.1039/c1cs15228a

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chu, S., and Majumdar, A. (2012). Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 488, 294–303. doi:10.1038/nature11475

Cui, L.-F., Yang, Y., Hsu, C.-M., and Cui, Y. (2009). Carbon-silicon core-shell nanowires as high capacity electrode for lithium ion batteries. Nano Lett. 9, 3370–3374. doi:10.1021/nl901670t

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dasgupta, N. P., Sun, J., Liu, C., Brittman, S., Andrews, S. C., Lim, J., et al. (2014). 25th anniversary article: semiconductor nanowires-synthesis, characterization, and applications. Adv. Mater. 26, 2137–2184. doi:10.1002/adma.201305929

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Débart, A., Paterson, A. J., Bao, J., and Bruce, P. G. (2008). α-MnO2 nanowires: a catalyst for the O2 electrode in rechargeable lithium batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 120, 4597–4600. doi:10.1002/anie.200705648

Dunn, B., Kamath, H., and Tarascon, J.-M. (2011). Electrical energy storage for the grid: a battery of choices. Science 334, 928–935. doi:10.1126/science.1212741

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Etacheri, V., Marom, R., Elazari, R., Salitra, G., and Aurbach, D. (2011). Challenges in the development of advanced Li-ion batteries: a review. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 3243–3262. doi:10.1039/c1ee01598b

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fobelets, K., Ding, P., Mohseni Kiasari, N., and Durrani, Z. (2012). Electrical transport in polymer-covered silicon nanowires. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 11, 661–665. doi:10.1109/tnano.2010.2049746

Forney, M. W., Ganter, M. J., Staub, J. W., Ridgley, R. D., and Landi, B. J. (2013). Prelithiation of silicon-carbon nanotube anodes for lithium ion batteries by stabilized lithium metal powder (SLMP). Nano Lett. 13, 4158–4163. doi:10.1021/nl401776d

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Freunberger, S. A., Chen, Y., Peng, Z., Griffin, J. M., Hardwick, L. J., Bardé, F., et al. (2011). Reactions in the rechargeable lithium-O2 battery with alkyl carbonate electrolytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 8040–8047. doi:10.1021/ja2021747

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Girishkumar, G., Mccloskey, B., Luntz, A., Swanson, S., and Wilcke, W. (2010). Lithium-air battery: promise and challenges. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 2193–2203. doi:10.1021/jz1005384

Gong, K., Du, F., Xia, Z., Durstock, M., and Dai, L. (2009). Nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube arrays with high electrocatalytic activity for oxygen reduction. Science 323, 760–764. doi:10.1126/science.1168049

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Goodenough, J. B. (2014). Electrochemical energy storage in a sustainable modern society. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 14–18. doi:10.1039/c3ee42613k

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Goodenough, J. B., and Park, K.-S. (2013). The Li-ion rechargeable battery: a perspective. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1167–1176. doi:10.1021/ja3091438

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Guan, C., Wang, X., Zhang, Q., Fan, Z., Zhang, H., and Fan, H. J. (2014). Highly stable and reversible lithium storage in SnO2 nanowires surface coated with a uniform hollow shell by atomic layer deposition. Nano Lett. 14, 4852–4858. doi:10.1021/nl502192p

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Guo, J., Xu, Y., and Wang, C. (2011). Sulfur-impregnated disordered carbon nanotubes cathode for lithium-sulfur batteries. Nano Lett. 11, 4288–4294. doi:10.1021/nl202297p

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Haag, J. M., Pattanaik, G., and Durstock, M. F. (2013). Nanostructured 3D electrode architectures for high-rate Li-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 25, 3238–3243. doi:10.1002/adma.201205079

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hart, R. W., White, H. S., Dunn, B., and Rolison, D. R. (2003). 3-D microbatteries. Electrochem. Commun. 5, 120–123. doi:10.1016/S1388-2481(02)00556-8

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hong, Y. J., Son, M. Y., and Kang, Y. C. (2013). One-pot facile synthesis of double-shelled SnO2 yolk-shell-structured powders by continuous process as anode materials for Li-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 25, 2279–2283. doi:10.1002/adma.201204506

Hu, Y.-Y., Liu, Z., Nam, K.-W., Borkiewicz, O. J., Cheng, J., Hua, X., et al. (2013). Origin of additional capacities in metal oxide lithium-ion battery electrodes. Nat. Mater. 12, 1130–1136. doi:10.1038/nmat3784

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Huang, G., Zhang, F., Du, X., Wang, J., Yin, D., and Wang, L. (2014). Core-shell NiFe2O4@TiO2 nanorods: an anode material with enhanced electrochemical performance for lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 11214–11219. doi:10.1002/chem.201403148

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Huang, J. Y., Zhong, L., Wang, C. M., Sullivan, J. P., Xu, W., Zhang, L. Q., et al. (2010). In situ observation of the electrochemical lithiation of a single SnO2 nanowire electrode. Science 330, 1515–1520. doi:10.1126/science.1195628

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Itkis, D. M., Semenenko, D. A., Kataev, E. Y., Belova, A. I., Neudachina, V. S., Sirotina, A. P., et al. (2013). Reactivity of carbon in lithium-oxygen battery positive electrodes. Nano Lett. 13, 4697–4701. doi:10.1021/nl4021649

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ji, X., Lee, K. T., and Nazar, L. F. (2009). A highly ordered nanostructured carbon-sulphur cathode for lithium-sulphur batteries. Nat. Mater. 8, 500–506. doi:10.1038/nmat2460

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jiang, H., Hu, Y., Guo, S., Yan, C., Lee, P. S., and Li, C. (2014). Rational design of MnO/carbon nanopeapods with internal void space for high-rate and long-life Li-ion batteries. ACS Nano 8, 6038–6046. doi:10.1021/nn501310n

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jiang, J., Luo, J., Zhu, J., Huang, X., Liu, J., and Yu, T. (2013). Diffusion-controlled evolution of core-shell nanowire arrays into integrated hybrid nanotube arrays for Li-ion batteries. Nanoscale 5, 8105–8113. doi:10.1039/c3nr01786a

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jung, H.-G., Hassoun, J., Park, J.-B., Sun, Y.-K., and Scrosati, B. (2012). An improved high-performance lithium-air battery. Nat. Chem. 4, 579–585. doi:10.1038/nchem.1376

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kempa, T. J., Day, R. W., Kim, S.-K., Park, H.-G., and Lieber, C. M. (2013). Semiconductor nanowires: a platform for exploring limits and concepts for nano-enabled solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 719–733. doi:10.1039/c3ee24182c

Lee, G.-H., Cooper, R. C., An, S. J., Lee, S., Van Der Zande, A., Petrone, N., et al. (2013a). High-strength chemical-vapor-deposited graphene and grain boundaries. Science 340, 1073–1076. doi:10.1126/science.1235126

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, S., Oshima, Y., Hosono, E., Zhou, H., Kim, K., Chang, H. M., et al. (2013b). In situ TEM observation of local phase transformation in a rechargeable LiMn2O4 nanowire battery. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 24236–24241. doi:10.1021/jp409032r

Li, H., and Zhou, H. (2012). Enhancing the performances of Li-ion batteries by carbon-coating: present and future. Chem. Commun. 48, 1201–1217. doi:10.1039/c1cc14764a

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, J., and Dahn, J. (2007). An in situ x-ray diffraction study of the reaction of Li with crystalline Si. J. Electrochem. Soc. 154, A156–A161. doi:10.1149/1.2409862

Li, S., Dong, Y.-F., Wang, D.-D., Chen, W., Huang, L., Shi, C.-W., et al. (2014). Hierarchical nanowires for high-performance electrochemical energy storage. Front. Phys. 9:303–322. doi:10.1007/s11467-013-0343-7

Li, S., Han, C.-H., Mai, L.-Q., Han, J.-H., Xu, X., and Zhu, Y.-Q. (2011). Rational synthesis of coaxial MoO3/PTh nanowires with improved electrochemical cyclability. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 6, 504–504.

Li, Y., Huang, Z., Huang, K., Carnahan, D., and Xing, Y. (2013). Hybrid Li-air battery cathodes with sparse carbon nanotube arrays directly grown on carbon fiber papers. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 3339–3345. doi:10.1039/c3ee41116h

Liao, J.-Y., Higgins, D., Lui, G., Chabot, V., Xiao, X., and Chen, Z. (2013). Multifunctional TiO2-C/MnO2 core-double-shell nanowire arrays as high-performance 3D electrodes for lithium ion batteries. Nano Lett. 13, 5467–5473. doi:10.1021/nl4030159

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lim, H. D., Park, K. Y., Song, H., Jang, E. Y., Gwon, H., Kim, J., et al. (2013). Enhanced power and rechargeability of a Li-O2 battery based on a hierarchical-fibril cnt electrode. Adv. Mater. 25, 1348–1352. doi:10.1002/adma.201204018

Liu, B., Zhang, J., Wang, X., Chen, G., Chen, D., Zhou, C., et al. (2012a). Hierarchical three-dimensional ZnCo2O4 nanowire arrays/carbon cloth anodes for a novel class of high-performance flexible lithium-ion batteries. Nano Lett. 12, 3005–3011. doi:10.1021/nl300794f

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, N., Wu, H., Mcdowell, M. T., Yao, Y., Wang, C., and Cui, Y. (2012b). A yolk-shell design for stabilized and scalable Li-ion battery alloy anodes. Nano Lett. 12, 3315–3321. doi:10.1021/nl3014814

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, X. H., Liu, Y., Kushima, A., Zhang, S., Zhu, T., Li, J., et al. (2012c). In situ TEM experiments of electrochemical lithiation and delithiation of individual nanostructures. Adv. Energy Mater. 2, 722–741. doi:10.1002/aenm.201200024

Liu, Y., Zhang, W., Zhu, Y., Luo, Y., Xu, Y., Brown, A., et al. (2012d). Architecturing hierarchical function layers on self-assembled viral templates as 3D nano-array electrodes for integrated Li-ion microbatteries. Nano Lett. 13, 293–300. doi:10.1021/nl304104q

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, H. K., Wang, G. X., Guo, Z., Wang, J., and Konstantinov, K. (2006). Nanomaterials for lithium-ion rechargeable batteries. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 6, 1–15. doi:10.1166/jnn.2006.103

Liu, J., Li, W., and Manthiram, A. (2010). Dense core-shell structured SnO2/C composites as high performance anodes for lithium ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 46, 1437–1439. doi:10.1039/b918501a

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, J., Song, K., Van Aken, P. A., Maier, J., and Yu, Y. (2014). Self-supported Li4Ti5O12-C nanotube arrays as high-rate and long-life anode materials for flexible Li-ion batteries. Nano Lett. 14, 2597–2603. doi:10.1021/nl5004174

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, N., Hu, L., Mcdowell, M. T., Jackson, A., and Cui, Y. (2011a). Prelithiated silicon nanowires as an anode for lithium ion batteries. ACS Nano 5, 6487–6493. doi:10.1021/nn2017167

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, X. H., Zheng, H., Zhong, L., Huang, S., Karki, K., Zhang, L. Q., et al. (2011b). Anisotropic swelling and fracture of silicon nanowires during lithiation. Nano Lett. 11, 3312–3318. doi:10.1021/nl201684d

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Liu, X. H., and Huang, J. Y. (2011). In situ TEM electrochemistry of anode materials in lithium ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 3844–3860. doi:10.1039/c1ee01918j

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lu, J., Li, L., Park, J.-B., Sun, Y.-K., Wu, F., and Amine, K. (2014). Aprotic and aqueous Li-O2 batteries. Chem. Rev. 114, 5611–5640. doi:10.1021/cr400573b

Mai, L., Dong, F., Xu, X., Luo, Y., An, Q., Zhao, Y., et al. (2013a). Cucumber-like V2O5/poly(3, 4-ethylenedioxythiophene)&MnO2 nanowires with enhanced electrochemical cyclability. Nano Lett. 13, 740–745. doi:10.1021/nl304434v

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mai, L., Li, S., Dong, Y., Zhao, Y., Luo, Y., and Xu, H. (2013b). Long-life and high-rate Li3V2(PO4)3/C nanosphere cathode materials with three-dimensional continuous electron pathways. Nanoscale 5, 4864–4869. doi:10.1039/c3nr01490h

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mai, L., Dong, Y., Xu, L., and Han, C. (2010a). Single nanowire electrochemical devices. Nano Lett. 10, 4273–4278. doi:10.1021/nl102845r

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mai, L., Xu, L., Han, C., Xu, X., Luo, Y., Zhao, S., et al. (2010b). Electrospun ultralong hierarchical vanadium oxide nanowires with high performance for lithium ion batteries. Nano Lett. 10, 4750–4755. doi:10.1021/nl103343w

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mai, L., Xu, L., Hu, B., and Gu, Y. (2010c). Improved cycling stability of nanostructured electrode materials enabled by prelithiation. J. Mater. Res. 25, 1413–1420. doi:10.1557/jmr.2010.0196

Mai, L. Q., Hu, B., Chen, W., Qi, Y., Lao, C., Yang, R., et al. (2007). Lithiated MoO3 nanobelts with greatly improved performance for lithium batteries. Adv. Mater. 19, 3712–3716. doi:10.1002/adma.200700883

Mai, L. Q., Wei, Q. L., Tian, X. C., Zhao, Y. L., and An, Q. Y. (2014). Electrochemical nanowire devices for energy storage. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 13, 10–15. doi:10.1109/tnano.2013.2276524

Mai, L.-Q., Yang, F., Zhao, Y.-L., Xu, X., Xu, L., and Luo, Y.-Z. (2011a). Hierarchical MnMoO4/CoMoO4 heterostructured nanowires with enhanced supercapacitor performance. Nat. Commun. 2, 381. doi:10.1038/ncomms1387

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mai, L., Xu, X., Han, C., Luo, Y., Xu, L., Wu, Y. A., et al. (2011b). Rational synthesis of silver vanadium oxides/polyaniline triaxial nanowires with enhanced electrochemical property. Nano Lett. 11, 4992–4996. doi:10.1021/nl202943b

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Manthiram, A., Fu, Y., and Su, Y.-S. (2012). Challenges and prospects of lithium-sulfur batteries. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 1125–1134. doi:10.1021/ar300179v

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Min, H.-S., Park, B. Y., Taherabadi, L., Wang, C., Yeh, Y., Zaouk, R., et al. (2008). Fabrication and properties of a carbon/polypyrrole three-dimensional microbattery. J. Power Sources 178, 795–800. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2007.10.003

Mitchell, R. R., Gallant, B. M., Shao-Horn, Y., and Thompson, C. V. (2013). Mechanisms of morphological evolution of Li2O2 particles during electrochemical growth. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 1060–1064. doi:10.1021/jz4003586

Nazar, L. F., Cuisinier, M., and Pang, Q. (2014). Lithium-sulfur batteries. MRS Bull. 39, 436–442. doi:10.1557/mrs.2014.86

Nethravathi, C., Rajamathi, C. R., Rajamathi, M., Gautam, U. K., Wang, X., Golberg, D., et al. (2013). N-doped graphene-VO2(B)nanosheet-built 3D flower hybrid for lithium ion battery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface 5, 2708–2714. doi:10.1021/am400202v

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Niu, C., Meng, J., Han, C., Zhao, K., Yan, M., and Mai, L. (2014). VO2 nanowires assembled into hollow microspheres for high-rate and long-life lithium batteries. Nano Lett. 14, 2873–2878. doi:10.1021/nl500915b

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ogasawara, T., Débart, A., Holzapfel, M., Novák, P., and Bruce, P. G. (2006). Rechargeable Li2O2 electrode for lithium batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 1390–1393. doi:10.1021/ja056811q

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ogata, K., Salager, E., Kerr, C. J., Fraser, A. E., Ducati, C., Morris, A. J., et al. (2014). Revealing lithium-silicide phase transformations in nano-structured silicon-based lithium ion batteries via in situ NMR spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 5:3217 doi:10.1038/ncomms4217

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Peled, E., Sternberg, Y., Gorenshtein, A., and Lavi, Y. (1989). Lithium-sulfur battery: evaluation of dioxolane-based electrolytes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 136, 1621–1625. doi:10.1149/1.2096981

Peng, Z., Freunberger, S. A., Chen, Y., and Bruce, P. G. (2012). A reversible and higher-rate Li-O2 battery. Science 337, 563–566. doi:10.1126/science.1223985

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Reddy, A. L. M., Shaijumon, M. M., Gowda, S. R., and Ajayan, P. M. (2009). Coaxial MnO2/carbon nanotube array electrodes for high-performance lithium batteries. Nano Lett. 9, 1002–1006. doi:10.1021/nl803081j

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ren, W., Wang, C., Lu, L., Li, D., Cheng, C., and Liu, J. (2013). SnO2@ Si core-shell nanowire arrays on carbon cloth as a flexible anode for li ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 13433–13438. doi:10.1039/c3ta11943b

Seh, Z. W., Li, W., Cha, J. J., Zheng, G., Yang, Y., Mcdowell, M. T., et al. (2013). Sulphur-TiO2 yolk-shell nanoarchitecture with internal void space for long-cycle lithium-sulphur batteries. Nat. Commun. 4, 1331. doi:10.1038/ncomms2327

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Shao, Y., Park, S., Xiao, J., Zhang, J.-G., Wang, Y., and Liu, J. (2012). Electrocatalysts for nonaqueous lithium-air batteries: status, challenges, and perspective. ACS Catal. 2, 844–857. doi:10.1021/cs300036v

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Shen, L., Uchaker, E., Zhang, X., and Cao, G. (2012). Hydrogenated Li4Ti5O12 nanowire arrays for high rate lithium ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 24, 6502–6506. doi:10.1002/adma.201203151

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Shi, C., Feng, J., Huang, L., Liu, X., and Mai, L. (2013). Reaction mechanism characterization of La0.5Sr0.5CoO2.91 electrocatalyst for rechargeable li-air battery. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 8, 8924–8930.

Shui, J., Du, F., Xue, C., Li, Q., and Dai, L. (2014). Vertically aligned N-doped coral-like carbon fiber arrays as efficient air electrodes for high-performance nonaqueous Li-O2 batteries. ACS Nano 8, 3015–3022. doi:10.1021/nn500327p

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Song, T., Cheng, H., Choi, H., Lee, J.-H., Han, H., Lee, D. H., et al. (2011). Si/Ge double-layered nanotube array as a lithium ion battery anode. ACS Nano 6, 303–309. doi:10.1021/nn203572n

Su, L., Jing, Y., and Zhou, Z. (2011). Li ion battery materials with core-shell nanostructures. Nanoscale 3, 3967–3983. doi:10.1039/c1nr10550g

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sun, Z., Ai, W., Liu, J., Qi, X., Wang, Y., Zhu, J., et al. (2014). Facile fabrication of hierarchical ZnCo2O4/NiO core/shell nanowire arrays with improved lithium-ion battery performance. Nanoscale 6, 6563–6568. doi:10.1039/c4nr00533c

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Szczech, J. R., and Jin, S. (2011). Nanostructured silicon for high capacity lithium battery anodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 56–72. doi:10.1039/c0ee00281j

Tao, H.-C., Huang, M., Fan, L.-Z., and Qu, X. (2013). Effect of nitrogen on the electrochemical performance of core-shell structured Si/C nanocomposites as anode materials for Li-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 89, 394–399. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2012.11.092

Tarascon, J.-M., and Armand, M. (2001). Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 414, 359–367. doi:10.1038/35104644

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tian, X., Xu, X., He, L., Wei, Q., Yan, M., Xu, L., et al. (2014). Ultrathin pre-lithiated V6O13 nanosheet cathodes with enhanced electrical transport and cyclability. J. Power Sources 255, 235–241. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.01.017

Vu, A., Qian, Y., and Stein, A. (2012). Porous electrode materials for lithium-ion batteries-how to prepare them and what makes them special. Adv. Energy Mater. 2, 1056–1085. doi:10.1002/aenm.201200320

Wang, D., Zhao, Y., Xu, X., Kalele, M. H., Yan, M., An, Q., et al. (2014). Novel Li2MnO3 nanowire anode with internal Li-enrichment for lithium-ion battery. Nanoscale. 6, 8124–8129. doi:10.1039/c4nr01941e

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wang, H., Yang, Y., Liang, Y., Robinson, J. T., Li, Y., Jackson, A., et al. (2011a). Graphene-wrapped sulfur particles as a rechargeable lithium-sulfur battery cathode material with high capacity and cycling stability. Nano Lett. 11, 2644–2647. doi:10.1021/nl200658a

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wang, X.-J., Chen, H.-Y., Yu, X., Wu, L., Nam, K.-W., Bai, J., et al. (2011b). A new in situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction technique to study the chemical delithiation of LiFePO4. Chem. Commun. 47, 7170–7172. doi:10.1039/c1cc10870k

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wang, Y., Xia, H., Lu, L., and Lin, J. (2010). Excellent performance in lithium-ion battery anodes: rational synthesis of Co(CO3)0.5(OH)0.11H2O nanobelt array and its conversion into mesoporous and single-crystal Co3O4. ACS Nano 4, 1425–1432. doi:10.1021/nn9012675

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wei, Q., An, Q., Chen, D., Mai, L., Chen, S., Zhao, Y., et al. (2014). One-pot synthesized bicontinuous hierarchical Li3V2(PO4)3/C mesoporous nanowires for high-rate and ultralong-life lithium-ion batteries. Nano Lett. 14, 1042–1048. doi:10.1021/nl404709b

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wei, Z., Mao, H., Huang, T., and Yu, A. (2013). Facile synthesis of Sn/TiO2 nanowire array composites as superior lithium-ion battery anodes. J. Power Sources 223, 50–55. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2012.09.032

Wu, J. B., Guo, R. Q., Huang, X. H., and Lin, Y. (2014). Ternary core/shell structure of Co3O4/NiO/C nanowire arrays as high-performance anode material for Li-ion battery. J. Power Sources 248, 115–121. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.09.040

Xiao, J., Mei, D., Li, X., Xu, W., Wang, D., Graff, G. L., et al. (2011). Hierarchically porous graphene as a lithium-air battery electrode. Nano Lett. 11, 5071–5078. doi:10.1021/nl203332e

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Xiao, L., Cao, Y., Xiao, J., Schwenzer, B., Engelhard, M. H., Saraf, L. V., et al. (2012). A soft approach to encapsulate sulfur: polyaniline nanotubes for lithium-sulfur batteries with long cycle life. Adv. Mater. 24, 1176–1181. doi:10.1002/adma.201103392

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Xiong, Q., Lu, Y., Wang, X., Gu, C., Qiao, Y., and Tu, J. (2012). Improved electrochemical performance of porous fe3o4/carbon core/shell nanorods as an anode for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 536, 219–225. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2012.05.034

Xu, J. J., Xu, D., Wang, Z. L., Wang, H. G., Zhang, L. L., and Zhang, X. B. (2013). Synthesis of perovskite-based porous La0.75Sr0.25MnO3 nanotubes as a highly efficient electrocatalyst for rechargeable lithium-oxygen batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 3887–3890. doi:10.1002/anie.201210057

Xu, W., Zhao, K., Niu, C., Zhang, L., Cai, Z., Han, C., et al. (2014). Heterogeneous branched core-shell SnO2-PANI nanorod arrays with mechanical integrity and three dimentional electron transport for lithium batteries. Nano Energy 8, 196–204. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2014.06.006

Xu, X., Luo, Y.-Z., Mai, L.-Q., Zhao, Y.-L., An, Q.-Y., Xu, L., et al. (2012). Topotactically synthesized ultralong LiV3O8 nanowire cathode materials for high-rate and long-life rechargeable lithium batteries. NPG Asia Mater. 4, e20. doi:10.1038/am.2012.36

Yan, J., Sumboja, A., Khoo, E., and Lee, P. S. (2011). V2O5 loaded on SnO2 nanowires for high-rate Li ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 23, 746–750. doi:10.1002/adma.201003805

Yan, M., Wang, F., Han, C., Ma, X., Xu, X., An, Q., et al. (2013). Nanowire templated semihollow bicontinuous graphene scrolls: Designed construction, mechanism, and enhanced energy storage performance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 18176–18182. doi:10.1021/ja409027s

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Yang, J., Xie, J., Zhou, X., Zou, Y., Tang, J., Wang, S., et al. (2014). Functionalized N-doped porous carbon nanofiber webs for a lithium-sulfur battery with high capacity and rate performance. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 1800–1807. doi:10.1021/jp410385s

Yang, L., Wang, S., Mao, J., Deng, J., Gao, Q., Tang, Y., et al. (2013). Hierarchical MoS2/polyaniline nanowires with excellent electrochemical performance for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 25, 1180–1184. doi:10.1002/adma.201203999

Yang, P., and Tarascon, J.-M. (2012). Towards systems materials engineering. Nat. Mater. 11, 560–563. doi:10.1038/nmat3367

Yang, P., Yan, R., and Fardy, M. (2010). Semiconductor nanowire: what’s next? Nano Lett. 10, 1529–1536. doi:10.1021/nl100665r

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Yang, Y., Yu, G., Cha, J. J., Wu, H., Vosgueritchian, M., Yao, Y., et al. (2011). Improving the performance of lithium-sulfur batteries by conductive polymer coating. ACS Nano 5, 9187–9193. doi:10.1021/nn203436j

Yin, Y. X., Xin, S., Guo, Y. G., and Wan, L. J. (2013). Lithium-sulfur batteries: Electrochemistry, materials, and prospects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 13186–13200. doi:10.1002/anie.201304762

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhang, D.-A., Wang, Q., Wang, Q., Sun, J., Xing, L.-L., and Xue, X.-Y. (2014a). Core-shell SnO2@TiO2-B nanowires as the anode of lithium ion battery with high capacity and rate capability. Mater. Lett. 128, 295–298. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2014.04.160

Zhang, J., Shi, Z., and Wang, C. (2014b). Effect of pre-lithiation degrees of mesocarbon microbeads anode on the electrochemical performance of lithium-ion capacitors. Electrochim. Acta 125, 22–28. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2014.01.040

Zhang, L., Zhao, K., Xu, W., Meng, J., He, L., An, Q., et al. (2014c). Mesoporous VO2 nanowires with excellent cycling stability and enhanced rate capability for lithium batteries. RSC Adv. 4, 33332–33337. doi:10.1039/c4ra06304j

Zhang, G., Xia, B. Y., Xiao, C., Yu, L., Wang, X., Xie, Y., et al. (2013). General formation of complex tubular nanostructures of metal oxides for the oxygen reduction reaction and lithium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 125, 8805–8809. doi:10.1002/anie.201304355

Zhang, L. Q., Liu, X. H., Liu, Y., Huang, S., Zhu, T., Gui, L., et al. (2011). Controlling the lithiation-induced strain and charging rate in nanowire electrodes by coating. ACS Nano 5, 4800–4809. doi:10.1021/nn200770p

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhao, Y., Xu, L., Mai, L., Han, C., An, Q., Xu, X., et al. (2012). Hierarchical mesoporous perovskite La0.5Sr0.5CoO2.91 nanowires with ultrahigh capacity for li-air batteries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 19569–19574. doi:10.1073/pnas.1210315109

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zheng, G., Yang, Y., Cha, J. J., Hong, S. S., and Cui, Y. (2011). Hollow carbon nanofiber-encapsulated sulfur cathodes for high specific capacity rechargeable lithium batteries. Nano Lett. 11, 4462–4467. doi:10.1021/nl2027684

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhou, G., Li, F., and Cheng, H.-M. (2014). Progress in flexible lithium batteries and future prospects. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 1307–1338. doi:10.1039/c3ee43182g

Zhou, S., Liu, X., and Wang, D. (2010). Si/TiSi2 heteronanostructures as high-capacity anode material for Li ion batteries. Nano Lett. 10, 860–863. doi:10.1021/nl903345f

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhou, S., Yang, X., Lin, Y., Xie, J., and Wang, D. (2011a). A nanonet-enabled Li ion battery cathode material with high power rate, high capacity, and long cycle lifetime. ACS Nano 6, 919–924. doi:10.1021/nn204479n

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhou, W., Cheng, C., Liu, J., Tay, Y. Y., Jiang, J., Jia, X., et al. (2011b). Epitaxial growth of branched α-Fe2O3/SnO2 nano-heterostructures with improved lithium-ion battery performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 2439–2445. doi:10.1002/adfm.201100088

Zhu, Y., Murali, S., Stoller, M. D., Ganesh, K., Cai, W., Ferreira, P. J., et al. (2011). Carbon-based supercapacitors produced by activation of graphene. Science 332, 1537–1541. doi:10.1126/science.1200770

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: nanowires, Li-ion battery, Li-S battery, Li-air battery, in situ characterization

Citation: Huang L, Wei Q, Sun R and Mai L (2014) Nanowire electrodes for advanced lithium batteries. Front. Energy Res. 2:43. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2014.00043

Received: 25 August 2014; Accepted: 30 September 2014;

Published online: 27 October 2014.

Edited by:

Jie Xiao, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, USACopyright: © 2014 Huang, Wei, Sun and Mai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liqiang Mai, State Key Laboratory of Advanced Technology for Materials Synthesis and Processing, WUT-Harvard Joint Nano Key Laboratory, Wuhan University of Technology, 122 Luoshi Road, Wuhan 430070, China e-mail:bWxxNTE4QHdodXQuZWR1LmNu

Lei Huang

Lei Huang Qiulong Wei

Qiulong Wei Ruimin Sun

Ruimin Sun Liqiang Mai

Liqiang Mai