- Department of Endocrine Neoplasia and Hormonal Disorders, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, United States

Male germ cell development depends on multiple biological events that combine epigenetic reprogramming, cell cycle regulation, and cell migration in a spatio-temporal manner. Sertoli cells are a crucial component of the spermatogonial stem cell niche and provide essential growth factors and chemokines to developing germ cells. This review focuses mainly on the activation of master regulators of the niche in Sertoli cells and their targets, as well as on novel molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of growth and differentiation factors such as GDNF and retinoic acid by NOTCH signaling and other pathways.

Introduction

The Niche Microenvironment

Maintenance, repair, and regeneration of many mammalian organs depend on adult stem cells. Stem cells proliferate and differentiate to replace mature functional cells within tissues that have either high turnover such as blood, testis, and epithelia (intestine, skin, and respiratory tract), or tissues that have low turnover but a high regenerative potential upon disease or injury such as liver, pancreas, skeletal muscle, and bone (1). Precise regulation of adult stem cell fate is therefore critical for the support of tissue homeostasis, and stem cell maintenance must involve a fine balance between genetic and epigenetic mechanisms, external factors from the microenvironment and systemic support, and multiple signaling pathways elicited by paracrine and juxtacrine factors.

Over the years, evidence has accumulated showing that stem cell self-renewal depends on the constituents of their microenvironment called the niche (2, 3) and that in turn stem cells influence their own environment (4–6). The constituents of the niche can be classified into adjacent supporting cells such as fibroblasts, tissue macrophages, glial cells (brain), osteoblasts (bone marrow), Sertoli cells (testis) and myofibroblasts (gut), together with paracrine and juxtacrine factors secreted by these supporting cells, and the extracellular matrix. Once they leave the niche, stem cells become progenitor cells that are less plastic and differentiate at the expense of their immortality. Over the last 15 years, critical cellular and molecular components of the specialized niche microenvironment have begun to be unveiled in several tissues. Advanced techniques in lineage-tracing, endogenous cell and gene/protein deletions in animal models, and high-resolution microscopy have significantly improved our understanding of the molecular and cellular intricacies that maintain and integrate the many activities required to sustain tissue homeostasis.

The Spermatogonial Stem Cell Niche

In the mammalian testis, the male germline produces a life-long supply of haploid spermatozoa through the highly regulated and coordinated process of spermatogenesis. This process starts with the self-renewal of a small pool of diploid stem cells called spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs or Asingle spermatogonia), which can self-renew to maintain the pool or give rise to more mature germ cells called Apaired and Aaligned spermatogonia. Collectively, Asingle, Apaired and Aaligned spermatogonia are called undifferentiated spermatogonia (7). These cells further differentiate into differentiating spermatogonia and spermatocytes that undergo meiosis, producing haploid spermatids that will mature into spermatozoa. The longevity and the high output of sperm cell production relies therefore primarily on the proper maintenance of the pool of SSCs and their proliferation. Like other types of stem cells, SSCs rely on their micro-environment to sustain their growth and to initiate differentiation that signals their release from the basal part of the seminiferous epithelium and exit from the niche.

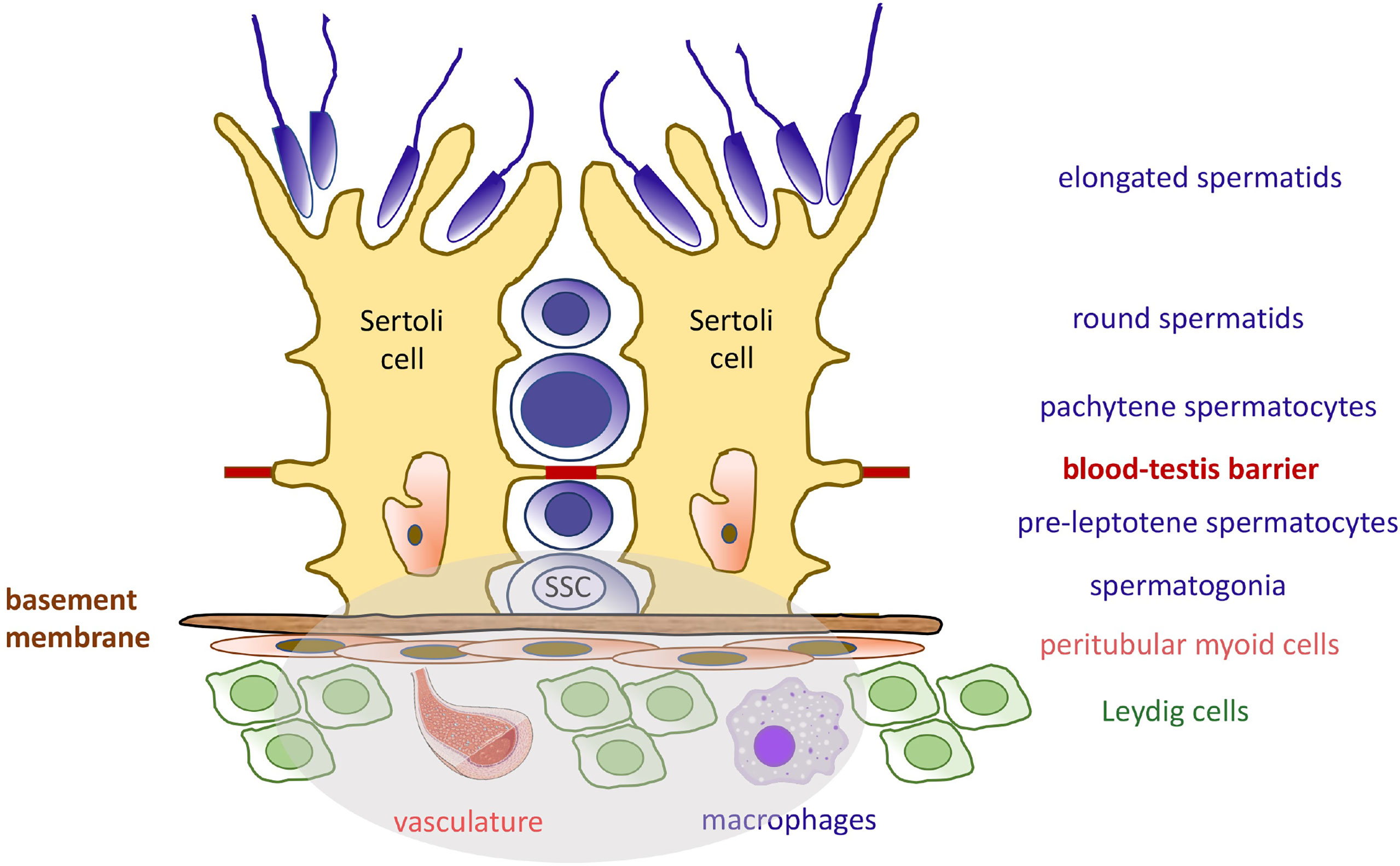

SSCs reside on the basement membrane that supports the seminiferous epithelium. They are in intimate physical contact with highly specialized somatic niche cells, the Sertoli cells, which directly provide soluble growth factors and membrane-bound signals to the germ cells (8). Other niche cell types have been recently investigated, including peritubular myoid cells, interstitial cells (macrophages and Leydig cells), and endothelial cells from the vascular network, which all produce critical growth factors (Figure 1) (9–15). Because of their direct physical association with germ cells, their secretion of growth factors and basement membrane components, and their architectural support of the seminiferous epithelium, Sertoli cells are considered the most important contributor of the testicular niche, and the regulation of their molecular communications with SSCs and more mature premeiotic germ cells will be the subject of this review.

Figure 1 Seminiferous Epithelium Organization and the Spermatogonial Stem Cell Niche. The seminiferous epithelium consists of germ cells (blue) and the somatic Sertoli cells (yellow). Sertoli cells produce many factors needed at various developmental steps during the spermatogenic process. The blood-testis barrier separates diploid germ cells from more mature cells and provide an immuno-privileged microenvironment for the completion of meiosis. Like Sertoli cells, the spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) are attached to the basement membrane. They rely on specific growth factors for self-renewal and maintenance of the pool. These molecules are produced by Sertoli cells, peritubular myoid cells, Leydig cells, and macrophages, as well as the vasculature. The components of the SSC niche are highlighted in the grey area.

Sertoli Cells as Structural Niche Organizers

It is now established that the number of Sertoli cells increases during fetal development due to growth stimulation through FSH/FSHR signaling. Sertoli cells proliferate up to day 15 after birth in mice and 17 days after birth in rats, after which the number of Sertoli cells reaches its peak and remain constant throughout life unless altered by insult and aging. Therefore, the number of Sertoli cells is finite and its maintenance is crucial for life-long spermatogenesis. Several years ago, de Franca et al. induced experimental hypothyroidism in the rat with propylthiouracil (PTU) administrated neonatally. The treatment significantly increased the period of Sertoli cell proliferation and therefore increased their number at puberty and beyond. This also increased germ cell number and the size of the testes (16). However, direct evidence that Sertoli cells indeed provide a structural and functional SSC niche support was provided by Oatley and colleagues (17). The authors treated male mouse pups with PTU, which led to increased Sertoli cell and germ cell numbers in the adult testes. Next, by using these mice as germ cells recipients after busulfan treatment destroyed their endogenous germ cells, they showed a significant increase of colonization by normal donor SSCs after transplantation. This demonstrated an increased presence of functional niches. Because neither the vasculature nor interstitial cell populations were altered in the PTU recipient model, they concluded that Sertoli cells are the most critical somatic cell type in the testis and that they create the SSC niche.

Master Regulators of the Niche

The germ cell and Sertoli cell behaviors leading to the establishment of the spermatogenic stem cell niche in the early postnatal testis are well known. In addition to Sertoli cell proliferation leading to the expansion of the niche units until puberty, one of the most striking cellular behavior is the movement of pro-spermatogonia, or gonocytes, toward the periphery of the cords at around day 3-4 after birth in rodents, and 8-12 weeks after birth in humans (18, 19). By postnatal day 6 in the mouse, about 90% of pro-spermatogonia have reached the basal lamina, have become SSCs and rapidly differentiate (20), whereas germ cells that failed to migrate have died (21). The past fifteen years have seen a growing interest in understanding how these processes are regulated and the discovery of Sertoli cell-specific genes that are master determinants of the niche has become a priority.

DMRT1 (Doublesex and Mab-3 related transcription factor 1) is a conserved gene that is expressed in the testes of all vertebrates. In the mouse, DMRT1 expression starts at the genital ridge stage and continues throughout adult life. DMRT1 is required for normal sexual development, and defective expression leads to abnormal testicular formation and XY feminization (22). While both germ cells and Sertoli cells express the gene, Sertoli cell-specific knockout of Dmrt1 led to testicular abnormalities at around day 7 post-partum (22–25). Sertoli cells lacking DMRT1 re-expressed Forkhead box L2 (FOXL2), a female gonad determinant (26). The cells could not polarize, reprogrammed into granulosa cells, and seminiferous tubule lumens did not form (22). Consequently, SSCs and undifferentiated spermatogonia were not maintained at the tubule periphery, the germ cell population remained disorganized, and germ cells died after meiotic arrest. This indicated that DMRT1 antagonizes FOXL2 and functions as a repressor of the female gonad development. Further, DMRT1 is also a known activator of androgen receptor (AR) (27, 28) and is crucial for cellular junction formation and function by driving the expression of Claudin 11 (Cldn11), Vinculin (Vcl), and gap junction protein alpha 3 (Gja3) (Table 1), therefore controlling the structural niche as well (28, 48, 79, 120).

In 2015, Chen and colleagues demonstrated that targeted loss of Gata4, a known Sertoli cell marker also involved in mouse genital ridge initiation, sex determination, and embryonic testis development (72–74), resulted in a loss of the establishment and maintenance of the SSC pool, and led to Sertoli cell-only syndrome (41). Loss of Gata4 altered the expression of a number of chemokines, including Cxcl12 (SFD1, binding to the CXCR4 receptor) and Ccl3 (binding to the CCR1 receptor), which are known to guide pro-spermatogonia toward the basement membrane and the niche provided by Sertoli cells (39, 40). Similarly, another Sertoli cell transcription factor, ETV5, was found to directly bind to the promoter of the chemokine Ccl9. CCL9 facilitated chemoattraction of stem/progenitor spermatogonia, which express CCR1, the receptor for CCL9 (42) (Table 1). Together, these results revealed a novel role for GATA4 and ETV5 in organizing the SSC niche via the transcriptional regulation of chemokine signaling shortly after birth. More recently, Alankarage and colleagues demonstrated that Etv5 in Sertoli cells is directly under control of SOX9, a transcription factor that specifies the function of Sertoli cells and their differentiation from somatic cell precursors (61).

Migration of pro-spermatogonia to the basement membrane and niches provided by Sertoli cells is also dependent on AIP1, a β-actin-interacting protein that mediates β-actin (ACTB) disassembly (29, 31). Sertoli and germ cell-specific deletion of mouse Aip1 each led to significant defects in germ cell migration at postnatal day 4, which corresponded to elevated numbers of actin filaments in the affected cells. Increased actin filaments might have caused cytoskeletal changes that impaired E-cadherin (CDH1) regulation in Sertoli cells and germ cells, decreasing germ cell motility. Aip1 deletion in Sertoli cells did not affect the expression and secretion of growth factors, suggesting that the disruption of SSC migration and function results from architectural changes in the postnatal niche.

Another determinant of the perinatal niche, CDC42, was recently identified by Mori et al. (46). Together with RAC1 and RHOA, CDC42 is a member of the RHO family of small GTP-ases, which are mainly involved in cell polarity and migration (43, 111). Importantly, a possible role of the small GTP-ases CDC42 and RAC1 in the regulation of the blood-testis-barrier (BTB), tight junction components, and Sertoli cell polarity was suggested by several authors (45, 47, 109). While deletion of Cdc42 expression in Sertoli cells in the Mori study did not lead to major changes in the BTB integrity and cell polarity, it led to the depletion of the growth factor glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), a major determinant of spermatogonial proliferation, possibly through the downregulation of canonical PAK1 activity downstream of CDC42 (44).

Epigenetic Regulators of the Niche

One of the first discovered epigenetic regulators of the SSC niche was the Switch-insensitive 3a (SIN3A) co-repressor protein, part of a massive transcriptional complex that interacts with a wide array of epigenetic regulators (114). The SIN3A transcriptional corepressor complex plays a role in diverse cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, tumorigenesis, apoptosis and cell fate determination (113). The classical mechanism of action of this complex is transcriptional silencing through histone deacetylation mediated by HDAC1/2. In the mouse testis, Sertoli cell specific Sin3a deletion resulted in a decrease of undifferentiated spermatogonia after birth. The Sertoli cell markers Kit Ligand (KITL) and Gdnf, which support germ cell proliferation, were not diminished. However, chemokine signaling molecules such as CXCL12/SDF1 and CXCR4, expressed by Sertoli cells and germ cells, respectively, were not detected. This again demonstrates that regulators of germ cell movement toward the periphery of testicular cords and the basement membrane after birth are critical for the establishment of the initial postnatal niche. However, the relationship between SIN3A and the signaling networks governed by GATA4 and ETV5 in Sertoli cells are not yet known.

In 2013, Wu and colleagues identified ARID4A and ARID4B (AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 4A/B) as additional master regulators critical for the establishment of the niche, in particular during the pro-spermatogonia to SSC transition phase (35, 36). Interestingly, ARID4B is a subunit of the SIN3A transcriptional repressor complex. Sertoli cell ablation of Arid4B expression resulted in Sertoli cell detachment from the basement membrane, which precluded niche formation and the movement of pro-spermatogonia toward the periphery of the testicular cords. Without niche support, the germ cells underwent apoptosis. The authors also showed that ARID4B can function as a transcriptional coactivator for androgen receptor (AR) and identified reproductive homeobox 5 (Rhox5) (124) as the target gene critical for spermatogenesis (34).

Another epigenetic regulator of the niche is WTAP, or Wilms Tumor 1-associated protein (33). WTAP regulates transcription and translation of genes by depositing N6-methyladenosine (m6A) marks directly on RNA transcripts or indirectly on transcriptional regulators (125). Jia and colleagues demonstrated that conditional deletion of Wtap in mouse Sertoli cells modified pre-mRNA splicing, diminished RNA export and translation, and therefore altered the transcription and translation of many Sertoli cell genes normally marked by m6A modification. Many of these genes were critical for SSC maintenance, spermatogonial differentiation, retinol metabolism, and the cell cycle, including Inhbb, Wt1, Arid4a, Arid4b, Etv5, Ar, Dmrt1, and Sin3a (Table 1) (23, 27, 35, 60, 83, 114, 126, 127). Consequently, progressive loss of undifferentiated spermatogonia was observed in WTAP-deficient testes and mice were sterile. Interestingly, while not normally marked by m6A modification, Gdnf, which is required for SSC maintenance and self-renewal, was also downregulated. The authors surmised that several of the key transcription regulators that have been reported to be important for Gdnf transcription contained m6A sites and were dysregulated by Wtap knockout.

Single Cell RNA-Seq and Spatial Transcriptional Dissection of Perinatal and mature Sertoli Cells

Single cell characterization of developing and mature Sertoli cells in rodents and humans, as well as their spatial transcriptional dissection, uncovered many genes potentially important for the organization of the niche, and are providing a large resource for functional analysis of possible signaling pathway networks (102, 128–132). All studies demonstrated that mouse Sertoli cells undergo stepwise changes during the perinatal period, which are dependent on the expression of SOX9, AMH, GATA1-4, DMRT1, NR3C1 and their target genes (Table 1) (32, 58, 101, 102, 116). Notably, as predicted, expression of cell cycle genes decreases as Sertoli cells mature after birth. Further, these data demonstrated a postnatal increase in expression of Sertoli-Sertoli cell junctions and germ cell-Sertoli cell junction signaling (102). Zhao and colleagues identified three stages of postnatal Sertoli cells maturation in humans. In stage a (2-5 years old), the top three differentially expressed genes were EGR3, JUN, and NR4A1 (Table 1) (30, 86). In stage b (8-11 years) S100A13, ENO1, and BEX1 were prominently expressed, while in stage c (17 years to adult) HOPX, DEFB119, and CST9L were upregulated (Table 1) (49, 57, 81). Gene Ontology and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) at each of the three stages indicated that genes ensuring proliferation and maintenance of cell numbers were prominently expressed in stage a (EGF, IGF, and ERK5 signaling), RHOA/ACTB motility and remodeling of Sertoli-Sertoli epithelial junctions were a feature of stage b, and pathways of cholesterol biosynthesis and germ cell-Sertoli cell junction signaling were increased in stage c (59, 82). In addition, protein transmembrane transport, phagosome maturation, and cellular metabolic processes were upregulated in stage c, confirming that the most important functions of mature Sertoli cells are the production of growth factors, phagocytosis of germ cells and metabolites processing. Collectively, these data indicate that single cell RNA-seq and spatial transcriptomic characterization of Sertoli cells generate reliable resources for future mechanistic studies of master regulators of the niche and their targets at different time points.

Sertoli Cell Factors Controlling SSC Maintenance And Self-Renewal.

In the seminiferous epithelium, Sertoli cells produce a number of soluble factors that are under the control of the above-described master regulators. These growth factors are critical for pro-spermatogonial maintenance in the fetus, maintenance of the SSC pool, self-renewal of SSCs after birth, and the onset of germ cell differentiation. The most critical factors include glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) (75), colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) (12), fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) (65, 66), leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) (10) and WNT family proteins (50, 122). They all bind to their cognate receptors at the surface of SSCs or undifferentiated spermatogonia and activate the MAPK or PI3K/AKT pathway to drive the cell cycle. They also promote SSC proliferation in vitro, which can be demonstrated by increased testes colonization after transplantation. KITL, the ligand for KIT receptor, and retinoic acid (RA) are considered major determinants of germ cell differentiation after birth, promote the switch between undifferentiated and differentiating spermatogonia and trigger meiotic entry (94, 133, 134).

Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor

GDNF is a member of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-b) superfamily that binds to the GFRA1/RET receptor complex at the surface of SSCs, Apaired and some Aaligned spermatogonia (75, 77). Meng and colleagues were first to demonstrate that GDNF haploinsufficiency in mice induced fertility defects after birth (75). The mice were fertile but exhibited increased numbers of seminiferous tubules lacking spermatogonia as they aged. In addition, transgenic animals overexpressing Gdnf accumulated undifferentiated spermatogonia. In 2006, Naughton and colleagues disrupted the expression of Ret and Gfra1 at the surface of SSCs, which resulted in their loss and led to the definitive proof of the critical function of this receptor-ligand interaction (78). Together with FGF2 and LIF, GDNF is critical for the self-renewal of SSCs in short- and long-term cultures (66). Because of its importance for spermatogenesis, efforts were made to understand the temporal regulation of its expression. Low levels of GDNF and RET are already present in the fetal gonad (76, 110). Since pro-spermatogonia do not proliferate until after birth, GDNF is therefore only necessary for their maintenance, highlighting the importance of its dosage (98). GDNF expression then increases until it reaches a peak at days 3-7 after birth (110, 135, 136). One interesting feature of GDNF expression in the adult is its cyclic pattern throughout the stages of the seminiferous epithelium. Cyclical production of soluble factors according to stages was demonstrated earlier by Johnston and colleagues using transillumination-assisted microdissection and microarray analysis (137). In the rat, GDNF expression is highest at stages XIII-I, and lowest at stage VII of the seminiferous epithelium (138), while in the mouse its expression is highest at stages IX-I and lowest at stages V-VIII when most cells are quiescent and the majority of Aaligned spermatogonia transition to the differentiating A1-A4 cells (85, 98, 139). When GDNF was ectopically overexpressed by Sertoli cells in Stages V-VIII, the number of GFRA1+/LIN28- germ cells, a subtype of As spermatogonia with enhanced self-renewal capacity, was increased (97, 98).

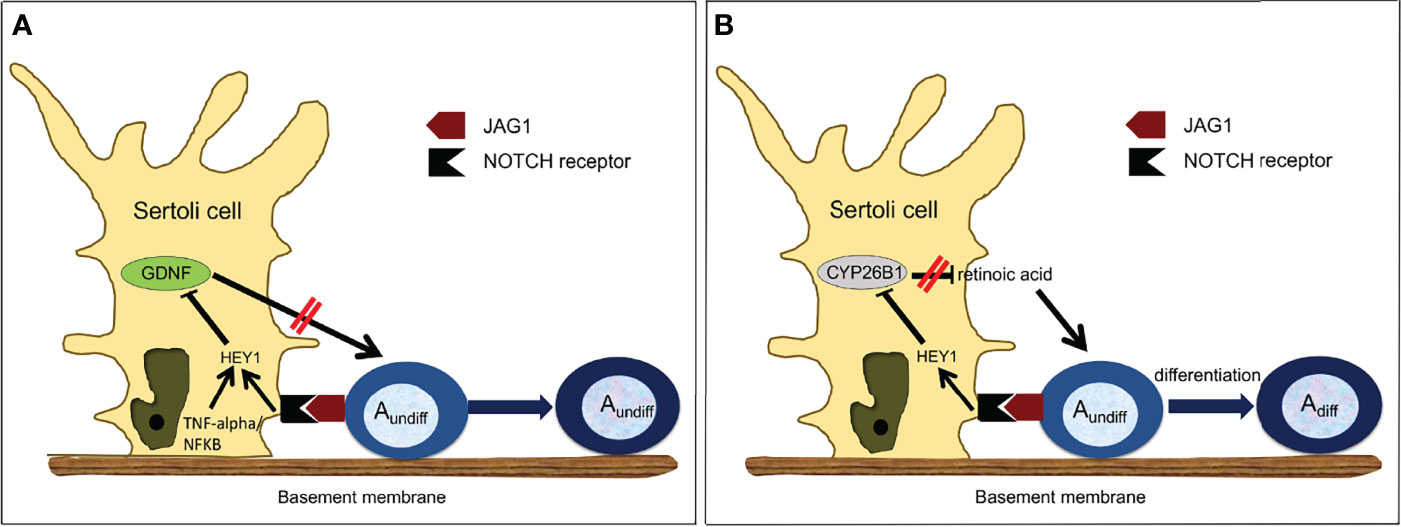

Several mechanisms regulating GDNF expression have been recently proposed. Garcia and colleagues established Sertoli cell-specific gain-of-function and loss-of-function mouse models of NOTCH receptor signaling (80, 100). Constitutive activation of this pathway in Sertoli cells led to a complete lack of germ cells by P2, and infertility. Expression of GDNF by Sertoli cells was significantly downregulated in the perinatal and adult testis and was due to upregulation of Hes/Hey transcription factors, which are canonical NOTCH targets and transcriptional repressors that bind to the GDNF promoter (80, 85). Further, loss-of-function of Rbpj, a mediator of NOTCH, and downregulation of Hes/Hey, led to upregulation of Gdnf expression (80) (Table 1). Importantly, the NOTCH ligand JAG1 was expressed mainly by undifferentiated spermatogonia (85). Consequently, the accumulation of undifferentiated spermatogonia around stage VII might increase NOTCH activity in Sertoli cells through JAG1, triggering the observed increase of Hes/Hey inhibitors at this stage and decrease in GDNF expression, leading to its cyclic expression. Therefore, spermatogonia, when in sufficient numbers, regulate their own homeostasis through downregulation of GDNF (55). These data are consistent with the observation that in wild type mice, the absence of germ cells triggered by busulfan treatment correlated with higher expression of GDNF (85, 135, 140) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2 Proposed Model of Regulation of Germ Cell Homeostasis by NOTCH Signaling. (A) Regulation of GDNF expression in Sertoli cells. GDNF is produced by Sertoli cells and normally increases Asingle, Apaired and some Aligned spermatogonia proliferation. However, as the number of undifferentiated spermatogonia increases, more JAG1 ligand is available to activate NOTCH signaling in Sertoli cells. Activated NOTCH will down-regulate the expression of GDNF through HES/HEY, which will decrease the number of undifferentiated spermatogonia, re-establishing GDNF production. Inhibition of GDNF by HES/HEY can be potentiated by the TNF-alpha/NF-KappaB pathway. (B) Regulation of CYP26B1 expression in Sertoli cells. CYP2681 is produced by Sertoli cells and normally degrades retinoic acid. However, as the number of undifferentiated spermatogonia increases, in particular Aaligned spermatogonia, more JAG1 ligand is available to activate NOTCH signaling in Sertoli cells. Activated NOTCH will down-regulate the expression of CYP26B1, which a llows retinoic acid to trigger the transition from undifferentiated to differentiating spermatogonia.

Other interesting mechanisms of GDNF regulation have been recently proposed. Given the fact that retinoic acid (RA) concentration is high when GDNF is low during the cycles of the seminiferous epithelium (141), Saracino and colleagues tested whether RA was a direct inhibitor of GDNF expression (142). Using ex vivo cultured immature testes and staged adult seminiferous tubules, they showed that negative regulation of Gdnf by RA indeed takes place in these models and demonstrated that Gdnf expression is directly regulated by RA through a mechanism involving a RARE-DR5 binding site on the Gdnf promoter. Negative regulation requires retinoic acid receptor (RARα) and induces a strong decrease of histone H4 acetylation levels around the transcription start. Further, because of the existence of a NF-kappaB binding site in the GDNF promoter, the same group investigated how TNF-alpha might influence GDNF expression (99). They demonstrated that in primary Sertoli cells, TNF-alpha induces the expression of the transcriptional repressor Hes1 by a NF-KappaB-dependent mechanism, which in turn downregulates GDNF. Therefore, TNF-alpha and NOTCH signaling may converge to regulate the expression of Hes1 and its target genes, including GDNF (Figure 2A).

Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF2)

While GDNF is a critical component of the niche, many in vivo and in vitro experiments demonstrated that other factors are needed to support maintenance and self-renewal of SSCs. Earlier examination of perinatal Sertoli cells demonstrated that they expressed FGF2, and that this expression was stimulated by follicle-stimulating hormone in vitro (FSH) (64). Together with EGF, LIF, and GDNF, fibroblast growth factor (FGF2) has been used to sustain the long-term proliferation of SSCs in culture (66, 143). Further, Takashima and colleagues demonstrated that FGF2 could induce SSC self-renewal alone in culture through activation of the transcription factors ETV5 and BCL6B (Table 1) (37, 38, 60, 62, 63, 67). They also showed that FGF2-depleted mouse testes produced increased levels of GDNF, which correlated with SSCs enrichment. This suggests that a balance or complementation between FGF2 and GDNF exists to maintain the stem cell pool (67). More recently, additional studies comparing the effects of GDNF and FGF2 on the proliferation of undifferentiated spermatogonia demonstrated that while both factors expanded the GFRA1+ population, FGF2 rather expanded a subpopulation of cells expressing RARG, which were therefore more susceptible to differentiate (68). This emphasizes the complex nature of signaling and a growth factor demand that is modulated upon the need to maintain germ cell homeostasis.

Other Growth Factors

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) is specifically produced by Sertoli cells. In rodents, PDGF is critical for prospermatogonia proliferation after birth (103, 104) and cooperates with estrogen signaling (106). Exposure to xenoestrogens in the environment might disrupt crosstalk between PDGF and estrogen-driven signaling pathways. This could lead to alteration of prospermatogonia behavior and induce preneoplastic states (105). Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) family members and their receptors are all produced by germ cells, Sertoli, cells and interstitial cells (117, 118). However, only the pro-angiogenic isoform VEGFA164 promotes SSC self-renewal, as determined by the SSC transplantation assay (119). WNT signaling plays a role in SSC maintenance (50, 144). WNT5A is produced by Sertoli cells but does not induce self-renewal. It rather promotes SSCs survival through a β-catenin (CTNNB1)-independent mechanism that activates mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 (MAPK8 or JNK) (50). Confirming this data, CTNNB1 ablation in germ cells led to spermatogenesis disruption but not to SSC loss (51, 52). Finally, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) has been used for decades to maintain undifferentiated embryonic stem cells in vitro, therefore an investigation of its expression in Sertoli cells and its effects on SSCs, at least in vitro, was attempted early on (96). LIF production in Sertoli cells was shown to depend on tumor necrosis factor (TNFα) (96) and is still widely used in cultures of primordial germ cells, pro-spermatogonia, and SSCs of many different species. However, LIF does not induce SSC self-renewal, and is rather used to maintain survival and start long-term SSC cultures (10).

Sertoli Cell Factors Controlling Spermatogonial Differentiation

Regulation of KIT/KITL

Activation of the KIT tyrosine kinase receptor by its ligand KITL is required for the survival and proliferation of primordial germ cells (PGCs) (90). KIT is downregulated in pro-spermatogonia, which stop proliferating once they enter the fetal gonads. After birth, KIT is re-expressed in differentiating spermatogonia (87, 88), which proliferate under the influence of KIT ligand (KITL) produced by Sertoli cells. Together with retinoic acid (RA), the KIT/KITL system is important for triggering meiotic entry of type B spermatogonia (92, 93), and KITL has been recently used in culture to differentiate rat spermatogonia without serum or somatic cells (95). Because KIT/KITL signaling is important not only for germ cells, but also for haematopoietic stem cell and melanoblasts, mechanisms controlling KIT transcription have been extensively studied. Further, KIT is mutated in about 25% of seminoma (91), and accounts for secondary mutations that confer resistance to drugs in other cancers. Therefore, regulation of its expression and identification of downstream effectors as druggable targets are of particular interest. Earlier studies have demonstrated that KIT expression in undifferentiated spermatogonia is repressed by PLZF (promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger), which is a transcriptional repressor with local and long-range chromatin remodeling activity (107, 108). Further, Dann and colleagues demonstrated that RA triggered spermatogonial differentiation through downregulation of PLZF (145). Thus, one mechanism by which PLZF maintains the pool of spermatogonial stem cells is through a direct repression of Kit transcription. The main mechanism of KIT upregulation involves the helix-loop-helix transcription factors SOHLH1 and SOHLH2 (Spermatogenesis and Oogenesis HLH1/2). Both factors are expressed in differentiating spermatogonia and their deletion leads to the disappearance of KIT-expressing spermatogonia. Further, ChIP-PCR analysis demonstrated that SOHLH1 binds the Kit promoter to activate its transcription (115). While investigations have mostly focused on the regulation of KIT, few studies have explored the regulation of KITL expression in the past 10 years. However, one study by Correia and colleagues demonstrated that 100 nM estrogen induced a decrease in Kit expression while increasing expression of Kitl in adult rat seminiferous tubules cultured ex vivo (89). Altered expression of the KIT/KITL system decreased germ cell proliferation and promoted apoptosis, which is not in accord with the data of previous studies (146).

Regulation of Retinoic Acid Activity

Rats and mice deprived of dietary retinoic acid (RA) can only produce Aundiff spermatogonia and are sterile (147, 148). Since these earlier studies, it has been well documented that retinoic acid (RA) activity is a major determinant of the transition between undifferentiated and differentiating germ cells, and that RA also drives the meiotic process and spermatid maturation at stage VIII of the seminiferous epithelium (134, 149). It has been proposed that pulses of RA are triggered around this stage by somatic cells and germ cells to allow proper germ cell differentiation and maturation (150). This implies that RA must be degraded during the other stages. Recently, Parekh and colleagues demonstrated an inverse relationship between the expression of cytochrome P450 family 26 subfamily B member 1 (Cyp26b1), an enzyme that degrades RA (54), and NOTCH activity in Sertoli cells (56). They further provided evidence that in the adult testis activated NOTCH signaling in Sertoli cells down-regulates Cyp26b1 expression through the HES/HEY transcriptional repressors that bind to the Cyp26b1 promoter (56). Importantly, expression of these inhibitors is highest at stage VIII of the seminiferous epithelium (85). They also demonstrated that Aaligned spermatogonia, through their expression of the NOTCH receptor JAG1, were activating the NOTCH/HES/HEY axis in Sertoli cells and were responsible for Cyp26b1 down-regulation at stage VIII, allowing RA activity and therefore triggering their own differentiation into A1 spermatogonia (Figure 2B).

Conclusion

The Sertoli cell orchestrates spermatogenesis and is a major component of the SSC niche. The past decade has seen an increase in our understanding of these processes at the molecular level. In the perinatal testis, Sertoli cells support multiple aspects of germ cell development through paracrine factors, but the master regulators of the niche and the signaling networks regulating these soluble factors have just begun to be identified. State-of-the-art technologies exist that should help dissect the functions of novel genes and signaling pathways in Sertoli cells in the future. The efforts that were spent understanding the cyclic regulation of GDNF and Cyp26b1, and by extension RA, should be expanded to other growth and differentiation factors. In particular, surprisingly little is known about the signals that germ cells send to Sertoli cells and their neighboring germ cells. We hope that the use of spatial transcriptomics will help uncover the molecular signals and pathways that germ cells and Sertoli cells use to communicate between each other to direct testis function and maintain homeostasis. We have highlighted JAG1/NOTCH signaling as one possible mechanism that fulfills this role, but other modes of germ cell to Sertoli cell communication exist that still need to be identified.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was funded by NIH R01 HD081244 and NIH R03 HD101650.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Rando TA. Stem Cells, Ageing and the Quest for Immortality. Nature (2006) 441:1080–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04958

2. Spradling A, Drummond-Barbosa D, Kai T. Stem Cells Find Their Niche. Nature (2001) 414:98–104. doi: 10.1038/35102160

3. Scadden DT. The Stem-Cell Niche as an Entity of Action. Nature (2006) 441:1075–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04957

4. Baraniak PR, Mcdevitt TC. Stem Cell Paracrine Actions and Tissue Regeneration. Regener Med (2010) 5:121–43. doi: 10.2217/rme.09.74

5. Mosher KI, Andres RH, Fukuhara T, Bieri G, Hasegawa-Moriyama M, He Y, et al. Neural Progenitor Cells Regulate Microglia Functions and Activity. Nat Neurosci (2012) 15:1485–7. doi: 10.1038/nn.3233

6. Sowa Y, Imura T, Numajiri T, Nishino K, Fushiki S. Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Produce Factors Enhancing Peripheral Nerve Regeneration: Influence of Age and Anatomic Site of Origin. Stem Cells Dev (2012) 21:1852–62. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0403

7. De Rooij DG. The Nature and Dynamics of Spermatogonial Stem Cells. Development (2017) 144:3022–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.146571

8. Franca LR, Hess RA, Dufour JM, Hofmann MC, Griswold MD. The Sertoli Cell: One Hundred Fifty Years of Beauty and Plasticity. Andrology (2016) 4:189–212. doi: 10.1111/andr.12165

9. Chiarini-Garcia H, Raymer AM, Russell LD. Non-Random Distribution of Spermatogonia in Rats: Evidence of Niches in the Seminiferous Tubules. Reproduction (2003) 126:669–80. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1260669

10. Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Inoue K, Ogonuki N, Miki H, Yoshida S, Toyokuni S, et al. Leukemia Inhibitory Factor Enhances Formation of Germ Cell Colonies in Neonatal Mouse Testis Culture. Biol Reprod (2007) 76:55–62. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.055863

11. Yoshida S, Sukeno M, Nabeshima Y. A Vasculature-Associated Niche for Undifferentiated Spermatogonia in the Mouse Testis. Science (2007) 317:1722–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1144885

12. Oatley JM, Oatley MJ, Avarbock MR, Tobias JW, Brinster RL. Colony Stimulating Factor 1 is an Extrinsic Stimulator of Mouse Spermatogonial Stem Cell Self-Renewal. Development (2009) 136:1191–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.032243

13. Oatley JM, Brinster RL. The Germline Stem Cell Niche Unit in Mammalian Testes. Physiol Rev (2012) 92:577–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2011

14. Chen LY, Willis WD, Eddy EM. Targeting the Gdnf Gene in Peritubular Myoid Cells Disrupts Undifferentiated Spermatogonial Cell Development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2016) 113:1829–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517994113

15. Potter SJ, Defalco T. Role of the Testis Interstitial Compartment in Spermatogonial Stem Cell Function. Reproduction (2017) 153:R151–62. doi: 10.1530/REP-16-0588

16. De Franca LR, Hess RA, Cooke PS, Russell LD. Neonatal Hypothyroidism Causes Delayed Sertoli Cell Maturation in Rats Treated With Propylthiouracil: Evidence That the Sertoli Cell Controls Testis Growth. Anat Rec (1995) 242:57–69. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092420108

17. Oatley MJ, Racicot KE, Oatley JM. Sertoli Cells Dictate Spermatogonial Stem Cell Niches in the Mouse Testis. Biol Reprod (2011) 84:639–45. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.087320

18. Culty M. Gonocytes, the Forgotten Cells of the Germ Cell Lineage. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today (2009) 87:1–26. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20142

19. Manku G, Culty M. Mammalian Gonocyte and Spermatogonia Differentiation: Recent Advances and Remaining Challenges. Reproduction (2015) 149:R139–157. doi: 10.1530/REP-14-0431

20. Mclean DJ, Friel PJ, Johnston DS, Griswold MD. Characterization of Spermatogonial Stem Cell Maturation and Differentiation in Neonatal Mice. Biol Reprod (2003) 69:2085–91. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017020

21. De Rooij DG. Proliferation and Differentiation of Spermatogonial Stem Cells. Reproduction (2001) 121:347–54. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1210347

22. Matson CK, Murphy MW, Sarver AL, Griswold MD, Bardwell VJ, Zarkower D. DMRT1 Prevents Female Reprogramming in the Postnatal Mammalian Testis. Nature (2011) 476:101–4. doi: 10.1038/nature10239

23. Kim S, Bardwell VJ, Zarkower D. Cell Type-Autonomous and non-Autonomous Requirements for Dmrt1 in Postnatal Testis Differentiation. Dev Biol (2007) 307:314–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.04.046

24. Matson CK, Murphy MW, Griswold MD, Yoshida S, Bardwell VJ, Zarkower D. The Mammalian Doublesex Homolog DMRT1 is a Transcriptional Gatekeeper That Controls the Mitosis Versus Meiosis Decision in Male Germ Cells. Dev Cell (2010) 19:612–24. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.010

25. Zhang T, Oatley J, Bardwell VJ, Zarkower D. DMRT1 Is Required for Mouse Spermatogonial Stem Cell Maintenance and Replenishment. PloS Genet (2016) 12:e1006293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006293

26. Harris SE, Chand AL, Winship IM, Gersak K, Aittomaki K, Shelling AN. Identification of Novel Mutations in FOXL2 Associated With Premature Ovarian Failure. Mol Hum Reprod (2002) 8:729–33. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.8.729

27. Tan KA, De Gendt K, Atanassova N, Walker M, Sharpe RM, Saunders PT, et al. The Role of Androgens in Sertoli Cell Proliferation and Functional Maturation: Studies in Mice With Total or Sertoli Cell-Selective Ablation of the Androgen Receptor. Endocrinology (2005) 146:2674–83. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1630

28. Murphy MW, Sarver AL, Rice D, Hatzi K, Ye K, Melnick A, et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of DNA Binding and Transcriptional Regulation by the Mammalian Doublesex Homolog DMRT1 in the Juvenile Testis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2010) 107:13360–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006243107

29. Lee NP, Mruk D, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Is the Cadherin/Catenin Complex a Functional Unit of Cell-Cell Actin-Based Adherens Junctions in the Rat Testis? Biol Reprod (2003) 68:489–508. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.005793

30. Zhao L, Yao C, Xing X, Jing T, Li P, Zhu Z, et al. Single-Cell Analysis of Developing and Azoospermia Human Testicles Reveals Central Role of Sertoli Cells. Nat Commun (2020) 11:5683. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19414-4

31. Xu J, Wan P, Wang M, Zhang J, Gao X, Hu B, et al. AIP1-Mediated Actin Disassembly is Required for Postnatal Germ Cell Migration and Spermatogonial Stem Cell Niche Establishment. Cell Death Dis (2015) 6:e1818. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.182

32. Munsterberg A, Lovell-Badge R. Expression of the Mouse Anti-Mullerian Hormone Gene Suggests a Role in Both Male and Female Sexual Differentiation. Development (1991) 113:613–24. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.2.613

33. Jia GX, Lin Z, Yan RG, Wang GW, Zhang XN, Li C, et al. WTAP Function in Sertoli Cells Is Essential for Sustaining the Spermatogonial Stem Cell Niche. Stem Cell Rep (2020) 15:968–82. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2020.09.001

34. Wu RC, Zeng Y, Pan IW, Wu MY. Androgen Receptor Coactivator ARID4B Is Required for the Function of Sertoli Cells in Spermatogenesis. Mol Endocrinol (2015) 29:1334–46. doi: 10.1210/me.2015-1089

35. Wu RC, Jiang M, Beaudet AL, Wu MY. ARID4A and ARID4B Regulate Male Fertility, a Functional Link to the AR and RB Pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2013) 110:4616–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218318110

36. Wu RC, Zeng Y, Chen YF, Lanz RB, Wu MY. Temporal-Spatial Establishment of Initial Niche for the Primary Spermatogonial Stem Cell Formation Is Determined by an ARID4B Regulatory Network. Stem Cells (2017) 35:1554–65. doi: 10.1002/stem.2597

37. Schmidt JA, Avarbock MR, Tobias JW, Brinster RL. Identification of Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor-Regulated Genes Important for Spermatogonial Stem Cell Self-Renewal in the Rat. Biol Reprod (2009) 81:56–66. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.075358

38. Ishii K, Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T. FGF2 Mediates Mouse Spermatogonial Stem Cell Self-Renewal via Upregulation of Etv5 and Bcl6b Through MAP2K1 Activation. Development (2012) 139:1734–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.076539

39. Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Inoue K, Takashima S, Takehashi M, Ogonuki N, Morimoto H, et al. Reconstitution of Mouse Spermatogonial Stem Cell Niches in Culture. Cell Stem Cell (2012) 11:567–78. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.06.011

40. Yang QE, Kim D, Kaucher A, Oatley MJ, Oatley JM. CXCL12-CXCR4 Signaling is Required for the Maintenance of Mouse Spermatogonial Stem Cells. J Cell Sci (2013) 126:1009–20. doi: 10.1242/dev.097543

41. Chen SR, Tang JX, Cheng JM, Li J, Jin C, Li XY, et al. Loss of Gata4 in Sertoli Cells Impairs the Spermatogonial Stem Cell Niche and Causes Germ Cell Exhaustion by Attenuating Chemokine Signaling. Oncotarget (2015) 6:37012–27. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6115

42. Simon L, Ekman GC, Garcia T, Carnes K, Zhang Z, Murphy T, et al. ETV5 Regulates Sertoli Cell Chemokines Involved in Mouse Stem/Progenitor Spermatogonia Maintenance. Stem Cells (2010) 28:1882–92. doi: 10.1002/stem.508

43. Etienne-Manneville S. Cdc42–the Centre of Polarity. J Cell Sci (2004) 117:1291–300. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01115

44. Erickson JW, Cerione RA. Multiple Roles for Cdc42 in Cell Regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol (2001) 13:153–7. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00192-7

45. Wong EW, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Regulation of Blood-Testis Barrier Dynamics by TGF-Beta3 is a Cdc42-Dependent Protein Trafficking Event. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2010) 107:11399–404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001077107

46. Mori Y, Takashima S, Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Yi Z, Shinohara T. Cdc42 is Required for Male Germline Niche Development in Mice. Cell Rep (2021) 36:109550. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109550

47. Heinrich A, Bhandary B, Potter SJ, Ratner N, Defalco T. Cdc42 Activity in Sertoli Cells is Essential for Maintenance of Spermatogenesis. Cell Rep (2021) 37:109885. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109885

48. Florin A, Maire M, Bozec A, Hellani A, Chater S, Bars R, et al. Androgens and Postmeiotic Germ Cells Regulate Claudin-11 Expression in Rat Sertoli Cells. Endocrinology (2005) 146:1532–40. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0834

49. Tohonen V, Osterlund C, Nordqvist K. Testatin: A Cystatin-Related Gene Expressed During Early Testis Development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (1998) 95:14208–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14208

50. Yeh JR, Zhang X, Nagano MC. Wnt5a is a Cell-Extrinsic Factor That Supports Self-Renewal of Mouse Spermatogonial Stem Cells. J Cell Sci (2011) 124:2357–66. doi: 10.1242/jcs.080903

51. Kerr GE, Young JC, Horvay K, Abud HE, Loveland KL. Regulated Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling Sustains Adult Spermatogenesis in Mice. Biol Reprod (2014) 90:3. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.105809

52. Rivas B, Huang Z, Agoulnik AI. Normal Fertility in Male Mice With Deletion of Beta-Catenin Gene in Germ Cells. Genesis (2014) 52:328–32. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22742

53. Yang QE, Kim D, Kaucher A, Oatley MJ, Oatley JM.. CXCL12-CXCR4 Signaling is Required for the Maintenance of Mouse Spermatogonial StemCells. J Cell Sci (2013) 126:1009–20. doi: 10.1242/dev.097543

54. Koubova J, Menke DB, Zhou Q, Capel B, Griswold MD, Page DC. Retinoic Acid Regulates Sex-Specific Timing of Meiotic Initiation in Mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2006) 103:2474–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510813103

55. Parekh PA, Garcia TX, Hofmann MC. Regulation of GDNF Expression in Sertoli Cells. Reproduction (2019) 157:R95–R107. doi: 10.1530/REP-18-0239

56. Parekh PA, Garcia TX, Waheeb R, Jain V, Gandhi P, Meistrich ML, et al. Undifferentiated Spermatogonia Regulate Cyp26b1 Expression Through NOTCH Signaling and Drive Germ Cell Differentiation. FASEB J (2019) 33:8423–35. doi: 10.1096/fj.201802361R

57. Com E, Bourgeon F, Evrard B, Ganz T, Colleu D, Jegou B, et al. Expression of Antimicrobial Defensins in the Male Reproductive Tract of Rats, Mice, and Humans. Biol Reprod (2003) 68:95–104. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.005389

58. Guo J, Sosa E, Chitiashvili T, Nie X, Rojas EJ, Oliver E, et al. Single-Cell Analysis of the Developing Human Testis Reveals Somatic Niche Cell Specification and Fetal Germline Stem Cell Establishment. Cell Stem Cell (2021) 28:764–778.e764. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.12.004

59. Radhakrishnan B, Oke BO, Papadopoulos V, Diaugustine RP, Suarez-Quian CA. Characterization of Epidermal Growth Factor in Mouse Testis. Endocrinology (1992) 131:3091–9. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.6.1446643

60. Chen C, Ouyang W, Grigura V, Zhou Q, Carnes K, Lim H, et al. ERM is Required for Transcriptional Control of the Spermatogonial Stem Cell Niche. Nature (2005) 436:1030–4. doi: 10.1038/nature03894

61. Alankarage D, Lavery R, Svingen T, Kelly S, Ludbrook L, Bagheri-Fam S, et al. SOX9 Regulates Expression of the Male Fertility Gene Ets Variant Factor 5 (ETV5) During Mammalian Sex Development. Int J Biochem Cell Biol (2016) 79:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.08.005

62. Oatley JM, Avarbock MR, Telaranta AI, Fearon DT, Brinster RL. Identifying Genes Important for Spermatogonial Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2006) 103:9524–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603332103

63. Wu X, Goodyear SM, Tobias JW, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Spermatogonial Stem Cell Self-Renewal Requires ETV5-Mediated Downstream Activation of Brachyury in Mice. Biol Reprod (2011) 85:1114–23. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.091793

64. Mullaney BP, Skinner MK. Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF) Gene Expression and Protein Production During Pubertal Development of the Seminiferous Tubule: Follicle-Stimulating Hormone-Induced Sertoli Cell bFGF Expression. Endocrinology (1992) 131:2928–34. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.6.1446630

65. Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Ogonuki N, Inoue K, Miki H, Ogura A, Toyokuni S, et al. Long-Term Proliferation in Culture and Germline Transmission of Mouse Male Germline Stem Cells. Biol Reprod (2003) 69:612–6. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017012

66. Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Growth Factors Essential for Self-Renewal and Expansion of Mouse Spermatogonial Stem Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2004) 101:16489–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407063101

67. Takashima S, Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Tanaka T, Morimoto H, Inoue K, Ogonuki N, et al. Functional Differences Between GDNF-Dependent and FGF2-Dependent Mouse Spermatogonial Stem Cell Self-Renewal. Stem Cell Rep (2015) 4:489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.01.010

68. Masaki K, Sakai M, Kuroki S, Jo JI, Hoshina K, Fujimori Y, et al. FGF2 Has Distinct Molecular Functions From GDNF in the Mouse Germline Niche. Stem Cell Rep (2018) 10:1782–92. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.03.016

69. Steinberger A, Heindel JJ, Lindsey JN, Elkington JS, Sanborn BM, Steinberger E. Isolation and culture of FSH responsive Sertoli Cells. J Cell Sci (1975) 2(3):261–72. doi: 10.3109/07435807509053853

70. Orth JM. The role of follicle-stimulating hormone in controlling Sertoli cell proliferation in testes of fetal rats. J Cell Sci (1984) 115(4):1248–55. doi: 10.1210/endo-115-4-1248

71. Rannikki AS, Zhang FP, Huhtaniemi IT. Ontogeny of Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor Gene Expression in the Rat Testis and Ovary. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (1995) 107(2):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)03444-x

72. Tevosian SG, Albrecht KH, Crispino JD, Fujiwara Y, Eicher EM, Orkin SH. Gonadal Differentiation, Sex Determination and Normal Sry Expression in Mice Require Direct Interaction Between Transcription Partners GATA4 and FOG2. Development (2002) 129:4627–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4627

73. Bouma GJ, Washburn LL, Albrecht KH, Eicher EM. Correct Dosage of Fog2 and Gata4 Transcription Factors is Critical for Fetal Testis Development in Mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2007) 104:14994–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701677104

74. Hu YC, Okumura LM, Page DC. Gata4 is Required for Formation of the Genital Ridge in Mice. PloS Genet (2013) 9:e1003629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003629

75. Meng X, Lindahl M, Hyvonen ME, Parvinen M, De Rooij DG, Hess MW, et al. Regulation of Cell Fate Decision of Undifferentiated Spermatogonia by GDNF. Science (2000) 287:1489–93. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1489

76. Beverdam A, Koopman P. Expression Profiling of Purified Mouse Gonadal Somatic Cells During the Critical Time Window of Sex Determination Reveals Novel Candidate Genes for Human Sexual Dysgenesis Syndromes. Hum Mol Genet (2006) 15:417–31. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi463

77. Hofmann MC, Braydich-Stolle L, Dym M. Isolation of Male Germ-Line Stem Cells; Influence of GDNF. Dev Biol (2005) 279:114–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.006

78. Naughton CK, Jain S, Strickland AM, Gupta A, Milbrandt J. Glial Cell-Line Derived Neurotrophic Factor-Mediated RET Signaling Regulates Spermatogonial Stem Cell Fate. Biol Reprod (2006) 74:314–21. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.047365

79. Gerber J, Heinrich J, Brehm R. Blood-Testis Barrier and Sertoli Cell Function: Lessons From SCCx43KO Mice. Reproduction (2016) 151:R15–27. doi: 10.1530/REP-15-0366

80. Garcia TX, Farmaha JK, Kow S, Hofmann MC. RBPJ in Mouse Sertoli Cells is Required for Proper Regulation of the Testis Stem Cell Niche. Development (2014) 141:4468–78. doi: 10.1242/dev.113969

81. Asanoma K, Kato H, Inoue T, Matsuda T, Wake N. Analysis of a Candidate Gene Associated With Growth Suppression of Choriocarcinoma and Differentiation of Trophoblasts. J Reprod Med (2004) 49:617–26.

82. Smith EP, Svoboda ME, Van Wyk JJ, Kierszenbaum AL, Tres LL. Partial Characterization of a Somatomedin-Like Peptide From the Medium of Cultured Rat Sertoli Cells. Endocrinology (1987) 120:186–93. doi: 10.1210/endo-120-1-186

83. Jensen TK, Andersson AM, Hjollund NH, Scheike T, Kolstad H, Giwercman A, et al. Inhibin B as a Serum Marker of Spermatogenesis: Correlation to Differences in Sperm Concentration and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Levels. A Study of 349 Danish Men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (1997) 82:4059–63. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4456

84. Buzzard JJ, Loveland KL, O'Bryan MK, O'Connor AE, Bakker M, Hayashi T. Changes in circulating and testicular levels of inhibin A and B and activin A during postnatal development in the rat. Endocrinology (2004) 145(7):3532–41. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1036

85. Garcia TX, Parekh P, Gandhi P, Sinha K, Hofmann MC. The NOTCH Ligand JAG1 Regulates GDNF Expression in Sertoli Cells. Stem Cells Dev (2017) 26:585–98. doi: 10.1089/scd.2016.0318

86. Hamil KG, Conti M, Shimasaki S, Hall SH. Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Regulation of AP-1: Inhibition of C-Jun and Stimulation of Jun-B Gene Transcription in the Rat Sertoli Cell. Mol Cell Endocrinol (1994) 99:269–77. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)90017-5

87. Manova K, Nocka K, Besmer P, Bachvarova RF. Gonadal Expression of C-Kit Encoded at the W Locus of the Mouse. Development (1990) 110:1057–69. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.4.1057

88. Schrans-Stassen BH, Van De Kant HJ, De Rooij DG, Van Pelt AM. Differential Expression of C-Kit in Mouse Undifferentiated and Differentiating Type A Spermatogonia. Endocrinology (1999) 140:5894–900. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7172

89. Correia S, Alves MR, Cavaco JE, Oliveira PF, Socorro S. Estrogenic Regulation of Testicular Expression of Stem Cell Factor and C-Kit: Implications in Germ Cell Survival and Male Fertility. Fertil Steril (2014) 102:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.04.009

90. Dolci S, Williams DE, Ernst MK, Resnick JL, Brannan CI, Lock LF, et al. Requirement for Mast Cell Growth Factor for Primordial Germ Cell Survival in Culture. Nature (1991) 352:809–11. doi: 10.1038/352809a0

91. Kemmer K, Corless CL, Fletcher JA, Mcgreevey L, Haley A, Griffith D, et al. KIT Mutations are Common in Testicular Seminomas. Am J Pathol (2004) 164:305–13. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63120-3

92. Pellegrini M, Filipponi D, Gori M, Barrios F, Lolicato F, Grimaldi P, et al. ATRA and KL Promote Differentiation Toward the Meiotic Program of Male Germ Cells. Cell Cycle (2008) 7:3878–88. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.24.7262

93. Rossi P, Lolicato F, Grimaldi P, Dolci S, Di Sauro A, Filipponi D, et al. Transcriptome Analysis of Differentiating Spermatogonia Stimulated With Kit Ligand. Gene Expr Patterns (2008) 8:58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2007.10.007

94. Rossi P. Transcriptional Control of KIT Gene Expression During Germ Cell Development. Int J Dev Biol (2013) 57:179–84. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.130014pr

95. Chapman KM, Medrano GA, Chaudhary J, Hamra FK. NRG1 and KITL Signal Downstream of Retinoic Acid in the Germline to Support Soma-Free Syncytial Growth of Differentiating Spermatogonia. Cell Death Discovery (2015) 1. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2015.18

96. Piquet-Pellorce C, Dorval-Coiffec I, Pham MD, Jegou B. Leukemia Inhibitory Factor Expression and Regulation Within the Testis. Endocrinology (2000) 141:1136–41. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.3.7399

97. Zheng K, Wu X, Kaestner KH, Wang PJ. The Pluripotency Factor LIN28 Marks Undifferentiated Spermatogonia in Mouse. BMC Dev Biol (2009) 9:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-9-38

98. Sharma M, Braun RE. Cyclical Expression of GDNF is Required for Spermatogonial Stem Cell Homeostasis. Development (2018) 145. doi: 10.1242/dev.151555

99. Di Persio S, Starace D, Capponi C, Saracino R, Fera S, Filippini A, et al. TNF-Alpha Inhibits GDNF Levels in Sertoli Cells, Through a NF-kappaB-Dependent, HES1-Dependent Mechanism. Andrology (2021) 9:956–64. doi: 10.1111/andr.12959

100. Garcia TX, Defalco T, Capel B, Hofmann MC. Constitutive Activation of NOTCH1 Signaling in Sertoli Cells Causes Gonocyte Exit From Quiescence. Dev Biol (2013) 377:188–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.01.031

101. Nordkap L, Almstrup K, Nielsen JE, Bang AK, Priskorn L, Krause M, et al. Possible Involvement of the Glucocorticoid Receptor (NR3C1) and Selected NR3C1 Gene Variants in Regulation of Human Testicular Function. Andrology (2017) 5:1105–14. doi: 10.1111/andr.12418

102. Tan K, Song HW, Wilkinson MF. Single-Cell RNAseq Analysis of Testicular Germ and Somatic Cell Development During the Perinatal Period. Development (2020) 147. doi: 10.1242/dev.183251

103. Loveland KL, Zlatic K, Stein-Oakley A, Risbridger G, Dekretser DM. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Ligand and Receptor Subunit mRNA in the Sertoli and Leydig Cells of the Rat Testis. Mol Cell Endocrinol (1995) 108:155–9. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)03471-5

104. Li H, Papadopoulos V, Vidic B, Dym M, Culty M. Regulation of Rat Testis Gonocyte Proliferation by Platelet-Derived Growth Factor and Estradiol: Identification of Signaling Mechanisms Involved. Endocrinology (1997) 138:1289–98. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.3.5021

105. Thuillier R, Wang Y, Culty M. Prenatal Exposure to Estrogenic Compounds Alters the Expression Pattern of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptors Alpha and Beta in Neonatal Rat Testis: Identification of Gonocytes as Targets of Estrogen Exposure. Biol Reprod (2003) 68:867–80. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.009605

106. Thuillier R, Mazer M, Manku G, Boisvert A, Wang Y, Culty M. Interdependence of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor and Estrogen-Signaling Pathways in Inducing Neonatal Rat Testicular Gonocytes Proliferation. Biol Reprod (2010) 82:825–36. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.081729

107. Buaas FW, Kirsh AL, Sharma M, Mclean DJ, Morris JL, Griswold MD, et al. Plzf is Required in Adult Male Germ Cells for Stem Cell Self-Renewal. Nat Genet (2004) 36:647–52. doi: 10.1038/ng1366

108. Costoya JA, Hobbs RM, Barna M, Cattoretti G, Manova K, Sukhwani M, et al. Essential Role of Plzf in Maintenance of Spermatogonial Stem Cells. Nat Genet (2004) 36:653–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1367

109. Heinrich A, Potter SJ, Guo L, Ratner N, Defalco T. Distinct Roles for Rac1 in Sertoli Cell Function During Testicular Development and Spermatogenesis. Cell Rep (2020) 31:107513. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.077

110. Miles DC, Van Den Bergen JA, Wakeling SI, Anderson RB, Sinclair AH, Western PS. The Proto-Oncogene Ret is Required for Male Foetal Germ Cell Survival. Dev Biol (2012) 365:101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.02.014

111. Schmitz AA, Govek EE, Bottner B, Van Aelst L. Rho GTPases: Signaling, Migration, and Invasion. Exp Cell Res (2000) 261:1–12. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5049

112. Hu Z, MacLean JA, Bhardwaj A, Wilkinson MF. Regulation and function of the Rhox5 homeobox gene. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2007) 1120:72–83. doi: 10.1196/annals.1411.011

113. Grzenda A, Lomberk G, Zhang JS, Urrutia R. Sin3: Master Scaffold and Transcriptional Corepressor. Biochim Biophys Acta (2009) 1789:443–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.05.007

114. Payne CJ, Gallagher SJ, Foreman O, Dannenberg JH, Depinho RA, Braun RE. Sin3a is Required by Sertoli Cells to Establish a Niche for Undifferentiated Spermatogonia, Germ Cell Tumors, and Spermatid Elongation. Stem Cells (2010) 28:1424–34. doi: 10.1002/stem.464

115. Barrios F, Filipponi D, Campolo F, Gori M, Bramucci F, Pellegrini M, et al. SOHLH1 and SOHLH2 Control Kit Expression During Postnatal Male Germ Cell Development. J Cell Sci (2012) 125:1455–64. doi: 10.1242/jcs.092593

116. Morais Da Silva S, Hacker A, Harley V, Goodfellow P, Swain A, Lovell-Badge R. Sox9 Expression During Gonadal Development Implies a Conserved Role for the Gene in Testis Differentiation in Mammals and Birds. Nat Genet (1996) 14:62–8. doi: 10.1038/ng0996-62

117. Nalbandian A, Dettin L, Dym M, Ravindranath N. Expression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptors During Male Germ Cell Differentiation in the Mouse. Biol Reprod (2003) 69:985–94. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.013581

118. Lu N, Sargent KM, Clopton DT, Pohlmeier WE, Brauer VM, Mcfee RM, et al. Loss of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGFA) Isoforms in the Testes of Male Mice Causes Subfertility, Reduces Sperm Numbers, and Alters Expression of Genes That Regulate Undifferentiated Spermatogonia. Endocrinology (2013) 154:4790–802. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1363

119. Caires KC, De Avila JM, Cupp AS, Mclean DJ. VEGFA Family Isoforms Regulate Spermatogonial Stem Cell Homeostasis In Vivo. Endocrinology (2012) 153:887–900. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1323

120. Siu MK, Mruk DD, Lee WM, Cheng CY. Adhering Junction Dynamics in the Testis are Regulated by an Interplay of Beta 1-Integrin and Focal Adhesion Complex-Associated Proteins. Endocrinology (2003) 144:2141–63. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221035

121. Golestaneh N, Beauchamp E, Fallen S, Kokkinaki M, Uren A, Dym M. Wnt signaling promotes proliferation and stemness regulation of spermatogonial stem/progenitor cells. Reproduction (2009) 138(1):151–62. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0510

122. Yeh JR, Zhang X, Nagano MC. Indirect Effects of Wnt3a/beta-Catenin Signalling Support Mouse Spermatogonial Stem Cells In Vitro. PloS One (2012) 7:e40002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040002

123. Tong J, Flavell RA, Li H-B. RNA m6A modification and its function in diseases. (2018) 12(4):481–9. doi: 10.1007/s11684-018-0654-8

124. Lindsey JS, Wilkinson MF. Pem: A Testosterone- and LH-Regulated Homeobox Gene Expressed in Mouse Sertoli Cells and Epididymis. Dev Biol (1996) 179:471–84. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0276

125. Tong J, Flavell RA, Li HB. RNA M(6)A Modification and its Function in Diseases. Front Med (2018) 12:481–9. doi: 10.1007/s11684-018-0654-8

126. Buzzard JJ, Loveland KL, O'bryan MK, O'connor AE, Bakker M, Hayashi T, et al. Changes in Circulating and Testicular Levels of Inhibin A and B and Activin A During Postnatal Development in the Rat. Endocrinology (2004) 145:3532–41. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1036

127. Gao F, Maiti S, Alam N, Zhang Z, Deng JM, Behringer RR, et al. The Wilms Tumor Gene, Wt1, is Required for Sox9 Expression and Maintenance of Tubular Architecture in the Developing Testis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2006) 103:11987–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600994103

128. Guo J, Grow EJ, Yi C, Mlcochova H, Maher GJ, Lindskog C, et al. Chromatin and Single-Cell RNA-Seq Profiling Reveal Dynamic Signaling and Metabolic Transitions During Human Spermatogonial Stem Cell Development. Cell Stem Cell (2017) 21:533–546.e536. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.09.003

129. Green CD, Ma Q, Manske GL, Shami AN, Zheng X, Marini S, et al. A Comprehensive Roadmap of Murine Spermatogenesis Defined by Single-Cell RNA-Seq. Dev Cell (2018) 46:651–667.e610. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.07.025

130. Hermann BP, Cheng K, Singh A, Roa-De La Cruz L, Mutoji KN, Chen IC, et al. The Mammalian Spermatogenesis Single-Cell Transcriptome, From Spermatogonial Stem Cells to Spermatids. Cell Rep (2018) 25:1650–67.e1658. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.026

131. Lukassen S, Bosch E, Ekici AB, Winterpacht A. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Adult Mouse Testes. Sci Data (2018) 5:180192. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.192

132. Chen H, Murray E, Sinha A, Laumas A, Li J, Lesman D, et al. Dissecting Mammalian Spermatogenesis Using Spatial Transcriptomics. Cell Rep (2021) 37:109915. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109915

133. Griswold MD, Hogarth CA, Bowles J, Koopman P. Initiating Meiosis: The Case for Retinoic Acid. Biol Reprod (2012) 86:35. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.096610

134. Griswold MD. Spermatogenesis: The Commitment to Meiosis. Physiol Rev (2016) 96:1–17. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2015

135. Tadokoro Y, Yomogida K, Ohta H, Tohda A, Nishimune Y. Homeostatic Regulation of Germinal Stem Cell Proliferation by the GDNF/FSH Pathway. Mech Dev (2002) 113:29–39. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(02)00004-7

136. Shima JE, Mclean DJ, Mccarrey JR, Griswold MD. The Murine Testicular Transcriptome: Characterizing Gene Expression in the Testis During the Progression of Spermatogenesis. Biol Reprod (2004) 71:319–30. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.026880

137. Johnston DS, Wright WW, Dicandeloro P, Wilson E, Kopf GS, Jelinsky SA. Stage-Specific Gene Expression is a Fundamental Characteristic of Rat Spermatogenic Cells and Sertoli Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2008) 105:8315–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709854105

138. Johnston DS, Olivas E, Dicandeloro P, Wright WW. Stage-Specific Changes in GDNF Expression by Rat Sertoli Cells: A Possible Regulator of the Replication and Differentiation of Stem Spermatogonia. Biol Reprod (2011) 85:763–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.087676

139. Caires KC, De Avila J, Mclean DJ. Endocrine Regulation of Spermatogonial Stem Cells in the Seminiferous Epithelium of Adult Mice. Biores Open Access (2012) 1:222–30. doi: 10.1089/biores.2012.0259

140. Ryu BY, Orwig KE, Oatley JM, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Effects of Aging and Niche Microenvironment on Spermatogonial Stem Cell Self-Renewal. Stem Cells (2006) 24:1505–11. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0580

141. Hasegawa K, Namekawa SH, Saga Y. MEK/ERK Signaling Directly and Indirectly Contributes to the Cyclical Self-Renewal of Spermatogonial Stem Cells. Stem Cells (2013) 31:2517–27. doi: 10.1002/stem.1486

142. Saracino R, Capponi C, Di Persio S, Boitani C, Masciarelli S, Fazi F, et al. Regulation of Gdnf Expression by Retinoic Acid in Sertoli Cells. Mol Reprod Dev (2020) 87:419–29. doi: 10.1002/mrd.23323

143. Kubota H, Brinster RL. Culture of Rodent Spermatogonial Stem Cells, Male Germline Stem Cells of the Postnatal Animal. Methods Cell Biol (2008) 86:59–84. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)00004-6

144. Golestaneh N, Beauchamp E, Fallen S, Kokkinaki M, Uren A, Dym M. Wnt Signaling Promotes Proliferation and Stemness Regulation of Spermatogonial Stem/Progenitor Cells. Reproduction (2009) 138:151–62. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0510

145. Dann CT, Alvarado AL, Molyneux LA, Denard BS, Garbers DL, Porteus MH. Spermatogonial Stem Cell Self-Renewal Requires OCT4, a Factor Downregulated During Retinoic Acid-Induced Differentiation. Stem Cells (2008) 26:2928–37. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0134

146. Thuillier R, Manku G, Wang Y, Culty M. Changes in MAPK Pathway in Neonatal and Adult Testis Following Fetal Estrogen Exposure and Effects on Rat Testicular Cells. Microsc Res Tech (2009) 72:773–86. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20756

147. Griswold MD, Bishop PD, Kim KH, Ping R, Siiteri JE, Morales C. Function of Vitamin A in Normal and Synchronized Seminiferous Tubules. Ann N Y Acad Sci (1989) 564:154–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb25895.x

148. Van Pelt AM, Van Dissel-Emiliani FM, Gaemers IC, van der Burg MJ, Tanke HJ, De Rooij DG. Characteristics of A Spermatogonia and Preleptotene Spermatocytes in the Vitamin A-Deficient Rat Testis. Biol Reprod (1995) 53:570–8. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod53.3.570

149. Endo T, Freinkman E, De Rooij D, Page D. Periodic Production of Retinoic Acid by Meiotic and Somatic Cells Coordinates Four Transitions in Mouse Spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2017) 141(47): E10132-41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1710837114

Keywords: Sertoli cell, germ cell, growth factors, self-renewal, differentiation

Citation: Hofmann M-C and McBeath E (2022) Sertoli Cell-Germ Cell Interactions Within the Niche: Paracrine and Juxtacrine Molecular Communications. Front. Endocrinol. 13:897062. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.897062

Received: 15 March 2022; Accepted: 25 April 2022;

Published: 10 June 2022.

Edited by:

Vassilios Papadopoulos, University of Southern California, United StatesReviewed by:

Martine Culty, University of Southern California, United StatesAlan Diekman, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, United States

Copyright © 2022 Hofmann and McBeath. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marie-Claude Hofmann, bWhvZm1hbm5AbWRhbmRlcnNvbi5vcmc=

Marie-Claude Hofmann

Marie-Claude Hofmann Elena McBeath

Elena McBeath