94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Endocrinol., 26 May 2022

Sec. Cellular Endocrinology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.848816

This article is part of the Research TopicEmerging Receptors as New Targets in Health and DiseasesView all 5 articles

Elizabeth K. M. Johnstone1,2,3*

Elizabeth K. M. Johnstone1,2,3* Mohammed Akli Ayoub1,4

Mohammed Akli Ayoub1,4 Rebecca J. Hertzman1,3

Rebecca J. Hertzman1,3 Heng B. See1,2

Heng B. See1,2 Rekhati S. Abhayawardana1,2

Rekhati S. Abhayawardana1,2 Ruth M. Seeber1,2

Ruth M. Seeber1,2 Kevin D. G. Pfleger1,2,5*

Kevin D. G. Pfleger1,2,5*The angiotensin type 2 (AT2) receptor and the bradykinin type 2 (B2) receptor are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that have major roles in the cardiovascular system. The two receptors are known to functionally interact at various levels, and there is some evidence that the observed crosstalk may occur as a result of heteromerization. We investigated evidence for heteromerization of the AT2 receptor and the B2 receptor in HEK293FT cells using various bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)-proximity based assays, including the Receptor Heteromer Investigation Technology (Receptor-HIT) and the NanoBRET ligand-binding assay. The Receptor-HIT assay showed that Gαq, GRK2 and β-arrestin2 recruitment proximal to AT2 receptors only occurred upon B2 receptor coexpression and activation, all of which is indicative of AT2-B2 receptor heteromerization. Additionally, we also observed specific coupling of the B2 receptor with the Gαz protein, and this was found only in cells coexpressing both receptors and stimulated with bradykinin. The recruitment of Gαz, Gαq, GRK2 and β-arrestin2 was inhibited by B2 receptor but not AT2 receptor antagonism, indicating the importance of B2 receptor activation within AT2-B2 heteromers. The close proximity between the AT2 receptor and B2 receptor at the cell surface was also demonstrated with the NanoBRET ligand-binding assay. Together, our data demonstrate functional interaction between the AT2 receptor and B2 receptor in HEK293FT cells, resulting in novel pharmacology for both receptors with regard to Gαq/GRK2/β-arrestin2 recruitment (AT2 receptor) and Gαz protein coupling (B2 receptor). Our study has revealed a new mechanism for the enigmatic and poorly characterized AT2 receptor to be functionally active within cells, further illustrating the role of heteromerization in the diversity of GPCR pharmacology and signaling.

Angiotensin II (AngII) and bradykinin (BK) are two peptide hormones that have major regulatory roles in the cardiovascular system. AngII exerts its effects through two G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), the AngII type 1 (AT1) and the AngII type 2 (AT2) receptors, while BK exerts most of its cardiovascular effects through the BK type 2 (B2) GPCR. While the AT1 receptor mediates most of the classical actions of AngII, such as vasoconstriction, antinatriuresis, cell proliferation and hypertrophy (1), the effects of the AT2 receptor are less well characterized, and its molecular pharmacology and physiological functions remain to be fully elucidated (2, 3). Through the B2 receptor, BK mediates vasodilation that antagonizes the classical AngII vasoconstriction.

Although GPCRs are able to act as single, monomeric units, it is also believed that they can form homomeric or heteromeric complexes that may result in altered signaling. In particular, GPCR heteromers have been a major focus of research in GPCR pharmacology over the past decade. This has led to the characterization of numerous GPCR heteromers, including the AT1-AT2 heteromer (4–11), and also the controversial AT1-B2 heteromer (12–19). As yet, a functional heteromer between the AT2 and the B2 receptor has not been categorically demonstrated, however there are numerous examples of crosstalk between the two receptors. One of the least contentious aspects of AT2 receptor functioning is its action as a vasodilator. AT2 receptor-mediated vasodilation has been shown to occur via several signaling pathways, including the same nitric oxide (NO)/cyclic 3’-5’ guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) pathway involved in B2 receptor-mediated vasodilation (20). Furthermore, numerous studies have shown that BK is involved in AT2 receptor-mediated NO/cGMP vasodilation (21–23). Confocal fluorescence resonance energy transfer studies have shown the distance between the two receptors in PC12W cell membranes to be 50 ± 5 Å, suggesting that the observed functional interactions may be a result of heteromerization between the AT2 receptor and the B2 receptor (24).

This study aimed to provide further evidence for the existence of the AT2-B2 heteromer in HEK293FT cells, using various bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)-based proximity assays including the Receptor-Heteromer Investigation Technology (Receptor-HIT) (25, 26) and the NanoBRET ligand binding assay (27, 28). Receptor-HIT, which has most commonly been applied to GPCRs (GPCR-HIT) (5, 25, 27, 29–32), is an assay that enables detection and characterization of heteromers through ligand-dependent interaction with biomolecules (Figure 1). Using various BRET assays, this study provided evidence for the existence of the AT2-B2 heteromer in our system and also revealed novel pharmacology obtained by the receptors upon heteromerization.

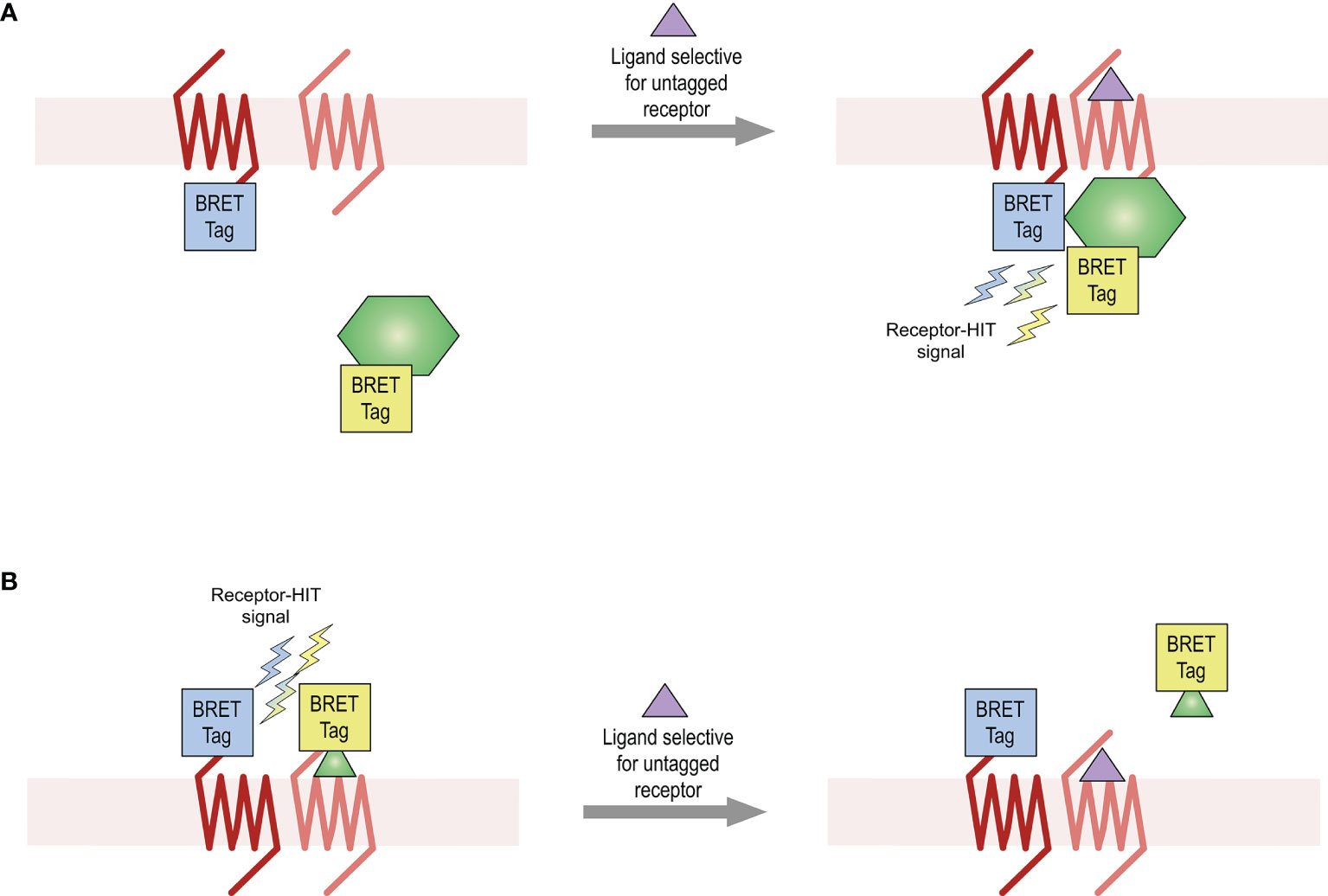

Figure 1 Receptor-HIT assay used for detection of receptor heteromers. The Receptor-HIT assay allows for monitoring of receptor interactions through recruitment of a labelled intracellular protein (A) or ligand (B). In this system using BRET as the proximity assay, one receptor is fused to one BRET tag (either a luciferase or a fluorophore) while the second receptor remains untagged. The interacting biomolecule is fused with the complementary BRET tag. A BRET signal upon addition of a ligand selective for the untagged receptor is indicative of receptor heteromerization.

All receptor constructs are human unless otherwise specified. AT2-Rluc8 (rat) and B2-Rluc8 cDNA constructs were generated from plasmids containing the respective receptor cDNA tagged with Rluc. The Rluc coding region was replaced with Rluc8 cDNA from pcDNA3.1-Rluc8 kindly provided by Andreas Loening and Sanjiv Gambhir (Stanford University, CA) (33), as described previously for other constructs (34). AT2-Rluc (rat), AT2-Venus (rat) (5) and HA-AT2 (rat; referred to as AT2 in the BRET1 and eBRET assays) were kindly provided by Walter Thomas (University of Queensland). B2 and HA-B2 (referred to from here-on-in as B2) and EP3 cDNA was obtained from the Missouri S&T cDNA Resource Center (www.cdna.org). B2-Rluc was previously produced by PCR amplification of B2 cDNA to remove the stop codon and ligation into pcDNA3 containing Rluc. B2-Venus was generated by replacing the Rluc8 coding region from B2-Rluc8 with Venus cDNA. NES–Venus–mGsq was kindly provided by Nevin Lambert (Augusta University, Augusta, Georgia). Gαq-Rluc8, Gαi3-Rluc8 and Gβ3 were from the TRUPATH kit, which was a gift from Bryan Roth (Addgene kit #1000000163), with Venus-Gγ9 being generated from GFP2-Gγ9, also from the TRUPATH kit (35). Gαz-Rluc8 was kindly provided by Martina Kocan (The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health). GRK2-Rluc8 was synthesized by GeneArt (ThermoFisher Scientific, Regensburg, Germany). The β-arrestin2-Venus cDNA construct was prepared previously from pCS2-Venus kindly provided by Atsushi Miyawaki (RIKEN Brain Science Institute, Wako-city, Japan) (34). Signal peptide and flag-tagged AT2 (referred to as AT2 in the NanoBRET ligand binding assays) and Nluc-AT2 were generated previously (27). Nluc-B2 was generated by replacing the AT2 coding region from Nluc-AT2 with B2 cDNA. Ligands used were AngII, BK and PGE2 (Sigma), icatibant and PD 123319 (Tocris Bioscience) and TAMRA-AngII (AnaSpec).

HEK293FT cells were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 in complete medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 0.3 mg/ml glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (GIBCO BRL, Carlsbad, CA). Transient transfections were carried using either GeneJuice (Merck, Kilsyth, Australia) or FuGENE (Promega) according to manufacturer’s instructions. All assays were carried out 48 hours post transfection.

Receptor-HIT is an assay that enables the identification and pharmacological profiling of receptor heteromers in live cell systems. The assay uses a proximity-based reporter system such as BRET to enable detection of heteromers through their ligand-dependent interaction with proteins or ligands (5, 25, 27, 29–32). The Receptor-HIT assay comprises three elements (Figure 1), which in these studies on the BRET platform are a BRET-tagged receptor, an untagged receptor, and a BRET-tagged interacting protein (Figure 1A) or a BRET-tagged interacting ligand [Figure 1B (27)]. If a change in BRET signal occurs upon addition of a ligand that is selective for the untagged receptor, this indicates proximity between the tagged receptor and the tagged interacting biomolecule. This Receptor-HIT signal signifies the close proximity of the two receptors, and is indicative of receptor heteromerization.

HEK293FT cells were transfected with cDNA as described in figure legends. BRET1 and eBRET assays used rat AT2 constructs. For all BRET1 assays (with the exception of Figures 6E, F), 5 µM coelenterazine h (Promega) was added and basal BRET was measured for 10-20 mins before adding agonist or vehicle and then continuing to measure BRET. Antagonist assays had a pretreatment of antagonist or vehicle (30 min) prior to addition of coelenterazine h. For the BRET1 assays in Figures 6E, F, cells were pretreated for 30 min with agonist or vehicle, with cells in Figure 6F having an additional pretreatment of antagonist or vehicle (30 min) prior to treatment with agonist. Following pretreatment, coelenterazine h was added to a final concentration of 5 µM and BRET was measured immediately. For eBRET assays, cells were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 2 hours with 30 µM EnduRen (Promega) to ensure substrate equilibrium was reached. Basal BRET was measured for 10-20 mins before adding agonist or vehicle and then continuing to measure BRET. Antagonist assays had a pretreatment of antagonist or vehicle (30 min) prior to addition of coelenterazine h. All BRET1 and eBRET measurements were taken at 37°C using either a LUMIstar Omega plate reader (BMG Labtech, Mornington, Victoria, Australia) with 460–490 nm and 520–550 nm filters; a CLARIOstar plate reader (BMG Labtech) with 420–480 nm and 520–620 nm filters; or a VICTOR Light plate reader (Perkin Elmer) with 400–475 nm and 520–540 nm filters. The ligand-induced BRET signal was calculated by subtracting the ratio of the long wavelength emission over the short wavelength emission for a vehicle-treated cell sample from the same ratio for a second aliquot of the same cells treated with agonist, as described previously (34, 36). In this calculation, the vehicle-treated cell sample represents the background, eliminating the requirement for measuring a donor-only control sample (34, 36). For BRET kinetic assays, the final pretreatment reading is presented at the zero time point (time of agonist/vehicle addition).

HEK293FT cells were transfected with cDNA as described in figure legends. NanoBRET assays used human AT2 constructs. For NanoBRET assays, cells were pretreated for 30 min with PD 123319 and then TAMRA-AngII was added (final concentration of 1 μM). Following another 30 min incubation, furimazine was added and BRET measured immediately at 37°C using a PHERAstar FS plate reader (BMG Labtech) with 420–500 nm and 610–LP filters or a LUMIstar Omega plate reader (BMG Labtech) with 410–490 nm and 610–LP filters. The BRET signal was calculated by subtracting the ratio of the long wavelength emission over the short wavelength emission and the data were normalized as percentage of TAMRA-AngII binding.

Measurement of IP1 accumulation was performed using the IP-One Tb kit (Cisbio Bioassays) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were treated for 30 minutes at 37°C with agonists or vehicle. Antagonist assays had an additional pre-treatment with antagonist or vehicle for 30 mins at 37°C, which was removed prior to treatment with agonist. The cells were then lysed by adding the supplied assay reagents, and the assay was incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Fluorescence was measured at 620 nm and 665 nm 50 µs after excitation at 340 nm using the EnVision 2102 multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer).

Data were presented and analyzed using Prism 9 software (GraphPad). Competition binding data and concentration-response data were fitted using logarithmic nonlinear regression (three parameter). Unpaired t-tests, one-way ANOVAs and two-way ANOVAs were used to determine statistical significance where appropriate (*p < 0.05).

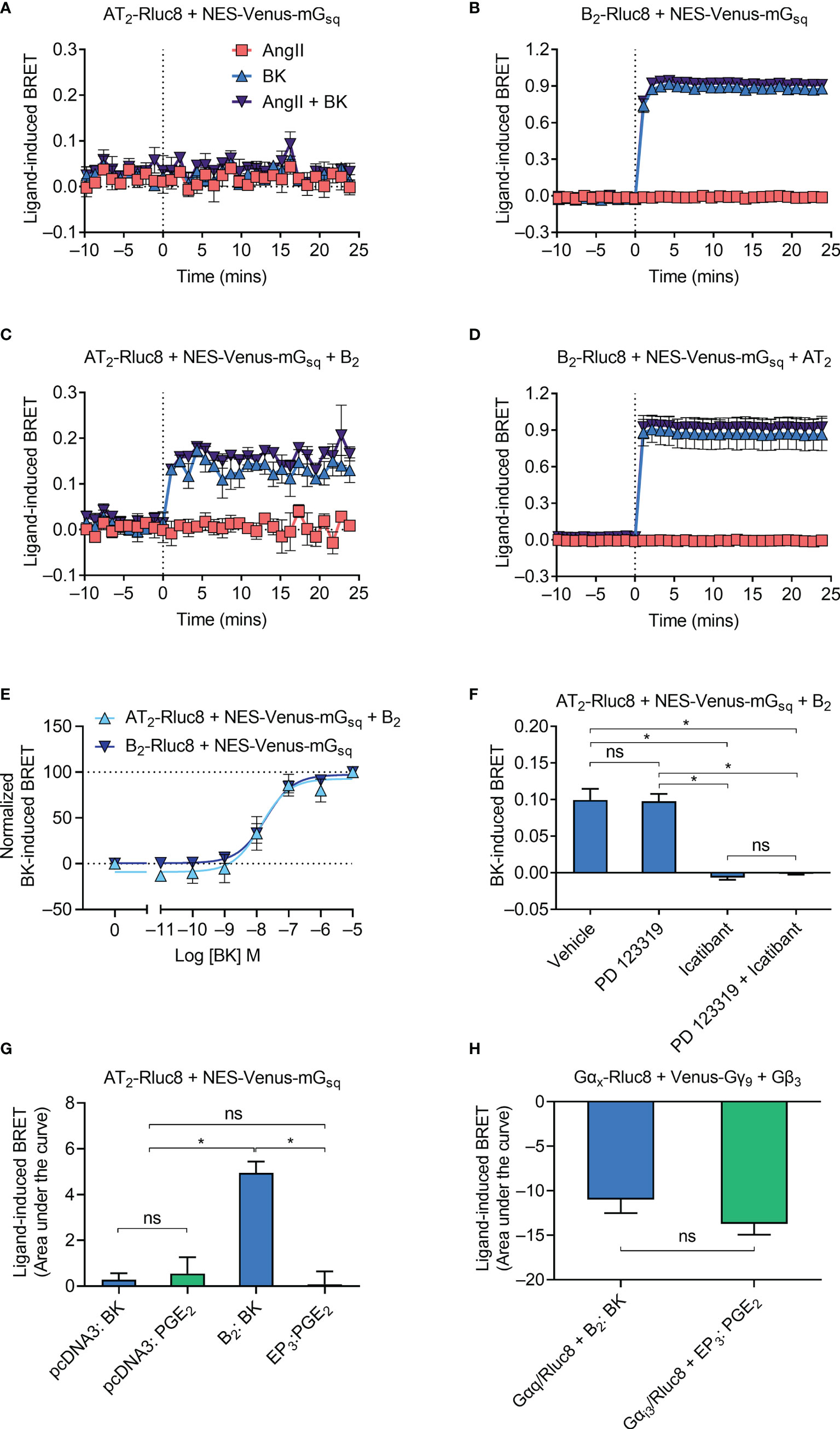

Following activation by an agonist, GPCRs typically interact with and activate heterotrimeric G proteins to initiate intracellular signaling cascades. The B2 receptor primarily couples to the Gαq class of G proteins (37) while the AT2 receptor is an unusual GPCR in that it does not readily couple to any G proteins (38). To investigate Gαq coupling by the receptors, we used a Venus-tagged mini G (mG) protein construct that comprises an engineered GTPase domain of the Gαs protein that has been modified to confer Gαq specificity (NES-Venus-mGsq). As expected, no ligand-induced recruitment of NES-Venus-mGsq to the Rluc8-tagged AT2 receptor (AT2-Rluc8) was observed (Figure 2A). In contrast, and also as expected, coexpression of NES-Venus-mGsq with the B2 receptor tagged with Rluc8 (B2-Rluc8) resulted in a BK-induced BRET signal (Figure 2B) indicative of recruitment of Gαq to the receptor.

Figure 2 Gαq recruitment to the AT2-B2 heteromer. HEK293FT cells were transfected with plasmid cDNA as described on graphs. (A–D) Time course analysis showing recruitment of NES-Venus-mGsq to receptors following addition of ligands at 0 mins. (E) BK concentration-response analysis showing recruitment of NES-Venus-mGsq to receptors. Normalized data taken from BRET assays at 17 min after agonist addition. (F) NES-Venus-mGsq Receptor-HIT assay in the presence of 50 μM antagonists (or vehicle) and 0.1 μM BK. Data are from BRET assays at 17 min after agonist addition. *p < 0.05; ns, not significant (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (G) Area under the curve ligand-induced BRET data. *p < 0.05; ns, not significant (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (H) Area under the curve ligand-induced BRET data. *p < 0.05; ns, not significant (unpaired t-test). All data are presented as mean ± SEM of ≥ three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

We then investigated Gαq coupling using the Receptor-HIT assay, again using NES-Venus-mGsq. Receptor-HIT uses a proximity-based reporter system such as BRET to enable detection and characterization of heteromers through their ligand-dependent interactions with labelled proteins or ligands (5, 25, 29–32) (Figure 1). Upon coexpression of the unlabeled B2 receptor in cells expressing AT2-Rluc8 and NES-Venus-mGsq we now observed a BK-induced BRET signal (Figure 2C), indicating recruitment of NES-Venus-mGsq proximal to AT2-Rluc8. This Receptor-HIT signal indicates the close proximity of the AT2 receptor and the B2 receptor, and suggests their interaction within a heteromeric complex. Coexpression of untagged AT2 receptor to cells expressing B2-Rluc8 and NES-Venus-mGsq did not alter the BRET signal (Figure 2D) from that seen without AT2 expression (Figure 2B).

We investigated the mGsq Receptor-HIT signal further by conducting concentration-response analysis. Figure 2E shows that there is no change in potency of mGsq coupling to AT2-B2 heteromers compared to B2 receptors (pEC50 ± SEM = 7.94 ± 0.29 vs. 7.73 ± 0.19, respectively; p > 0.05, unpaired t-test). When we conducted the mGsq Receptor-HIT assay in the presence of selective antagonists (Figure 2F), we saw that the AT2 receptor antagonist PD 123319 did not inhibit coupling of mGsq to AT2-B2 heteromers. In contrast, the putative B2 receptor antagonist icatibant was able to significantly reduce the level of mGsq recruitment, indicating the requirement of B2 receptor activation for Gαq coupling.

Finally, we investigated the specificity of the Receptor-HIT signal by conducting a similar experiment but instead using a GPCR not known to heteromerize with the AT2 receptor, the prostaglandin E receptor 3 (EP3 receptor). Here we found that only coexpression and activation of the B2 receptor resulted in a Receptor-HIT signal between AT2-Rluc8 and NES-Venus-mGsq (Figure 2G). No signal was observed when EP3 was coexpressed with AT2-Rluc8 and NES-Venus-mGsq and treated with PGE2 (Figure 2G), despite both B2 and EP3 being expressed within the cells, as shown by their activation of G protein (Figure 2H; Gαq for B2, and Gαi3 for EP3).

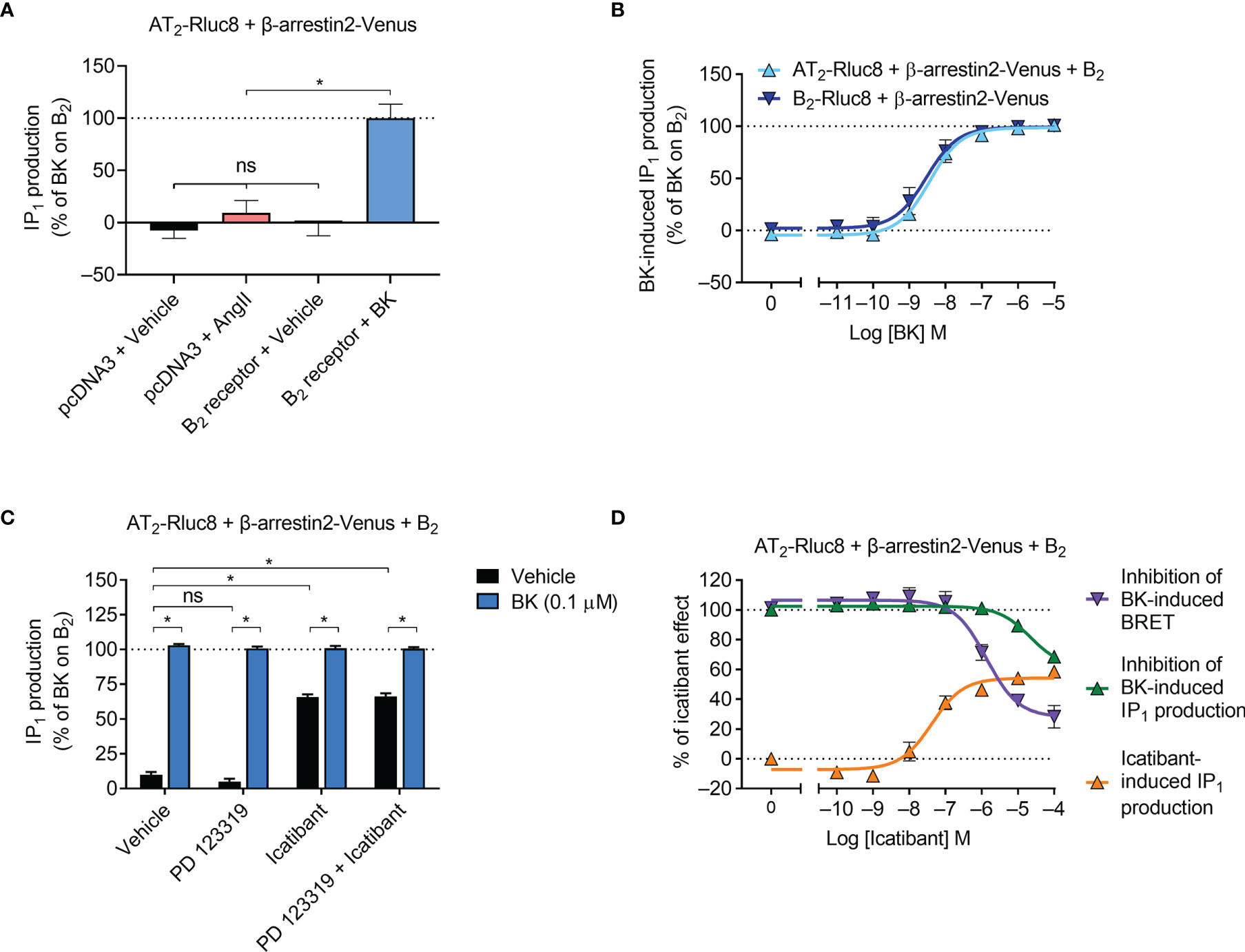

Gαq activation initiates a signaling cascade that leads to inositol phosphate signaling, which can be monitored by measuring the accumulation of the metabolite IP1. Using an IP1 assay and aliquots of transfected cells also used in the β-arrestin2 assays described below, we next investigated downstream Gαq signaling mediated by the receptors. As expected, we found that AngII did not induce IP1 production in cells expressing AT2/Rluc8 (Figure 3A). However, coexpression of the B2 receptor resulted in robust BK-induced IP1 production (Figure 3A). When we conducted concentration-response analysis, we found that there was no significant difference in the potency of IP1 production between cells expressing just the B2 receptor and cells expressing the B2 receptor and the AT2 receptor (Figure 3B; pEC50 ± SEM = 8.55 ± 0.20 vs. 8.45 ± 0.04, respectively; p > 0.05, unpaired t-test), just as we saw no difference in potency of mGsq recruitment in the BRET assay. When we conducted these IP1 assays with an antagonist pretreatment, we found that 10 μM of the AT2 receptor antagonist PD 123319 had no inhibitory effect on 0.1 μM BK-induced IP1 production (Figure 3C). Interestingly, in this assay 10 μM of the putative B2 selective antagonist icatibant was also unable to inhibit 0.1 μM BK-induced IP1 production. Indeed, it acted as a partial agonist in this assay, as can be seen by the substantial IP1 production in cells treated only with icatibant and no BK. Further analysis illustrated the concentration-dependent effect of IP1 production mediated by icatibant (Figure 3D). This concentration-response analysis also showed that high concentrations of icatibant were in fact able to inhibit BK-induced IP1 production. However, the potency of this effect was shifted substantially to the right of its inhibitory actions on BK-induced β-arrestin2 recruitment. These findings support reports of the partial agonism of icatibant, which has previously been observed mediating IP1 production through the B2 receptor (39).

Figure 3 IP1 signaling by the AT2-B2 heteromer. HEK293FT cells were transfected with plasmid cDNA as described on graphs. (A) Ligand-induced IP1 signaling in cells expressing AT2-Rluc8, with or without the B2 receptor. *p < 0.05; ns, not significant (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (B) Concentration-response analysis showing BK-induced IP1 signaling. (C) IP1 assay in the presence of 10 μM antagonists (or vehicle) and 0.1 μM BK. *p < 0.05 (two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test). (D) Concentration-response analysis comparing agonistic and antagonistic actions of icatibant, the latter antagonizing 0.1 μM BK. All data are presented as mean ± SEM of ≥ three independent experiments performed in duplicate (IP1 assay) or triplicate (BRET).

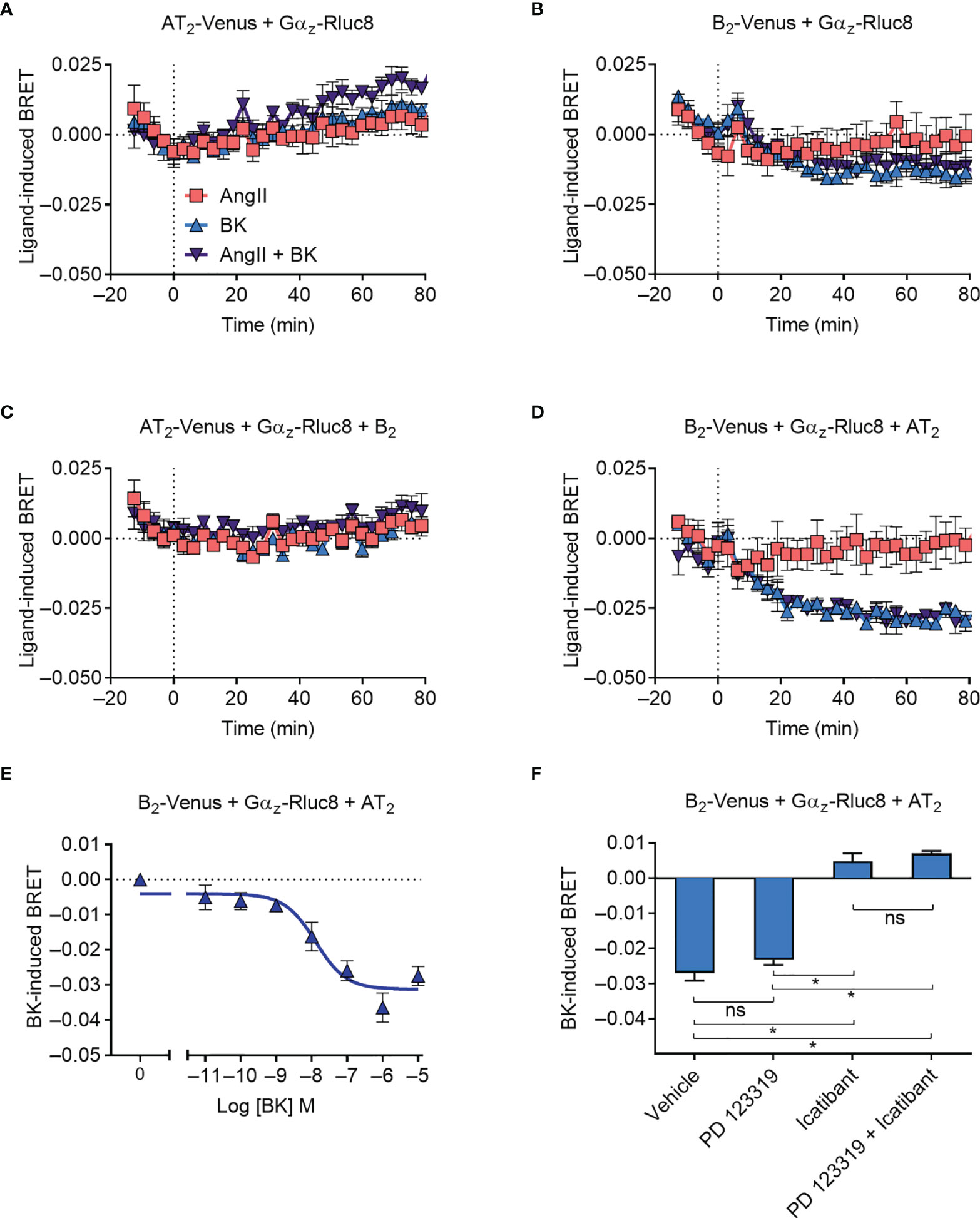

We next investigated Gαz protein recruitment to the receptors, using Gαz tagged with Rluc8 (Gαz-Rluc8). As Gαz is not a known signaling partner for either the AT2 receptor or the B2 receptor, we did not expect to observe any recruitment, and this was confirmed in our BRET assay expressing either Venus-tagged receptor and Gαz-Rluc8 (Figures 4A, B). Coexpression of the untagged B2 receptor did not alter the BRET signal between AT2-Venus and Gαz-Rluc8 (Figure 4C), however, coexpression of the untagged AT2 receptor interestingly resulted in a marked decrease in the BRET signal between B2-Venus and Gαz-Rluc8 upon treatment with BK (Figure 4D). A decrease in the BRET signal suggests that there is a preformed complex between B2-Venus and Gαz-Rluc8, which either disassociates or undergoes conformational rearrangement that increases the distance between the two BRET tags (40–42). In either case, this BRET signal provides further evidence in support of the existence of a functional AT2-B2 heteromer, and illustrates completely novel pharmacology it has adopted.

Figure 4 Gαz recruitment to the AT2-B2 heteromer. HEK293FT cells were transfected with plasmid cDNA as described on graphs. (A–D) Time course analysis showing interaction of Gαz-Rluc8 with receptors following addition of ligands at 0 mins. (E) BK concentration-response analysis showing recruitment of Gαz-Rluc8 to B2 receptors. Data taken from BRET assays at 60 min after agonist addition. (F) Gαz-Rluc8 Receptor-HIT assay in the presence of 10 μM antagonists and 0.1 μM BK. Data taken from BRET assays at 30 min after agonist addition. *p < 0.05; ns, not significant (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). All data are presented as mean ± SEM of ≥ three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

We also investigated the concentration-dependence of the Gαz BRET signal (Figure 4E) and found a similar potency of BK-induced concentration-dependence as observed for mGsq coupling (pEC50 ± SEM = 7.94 ± 0.29, unpaired t-test). Likewise, when we conducted the assay in the presence of selective antagonists, we again found that the Gαz BRET signal could be blocked by B2 receptor inhibition (icatibant), but not AT2 inhibition (PD 123319) (Figure 4F).

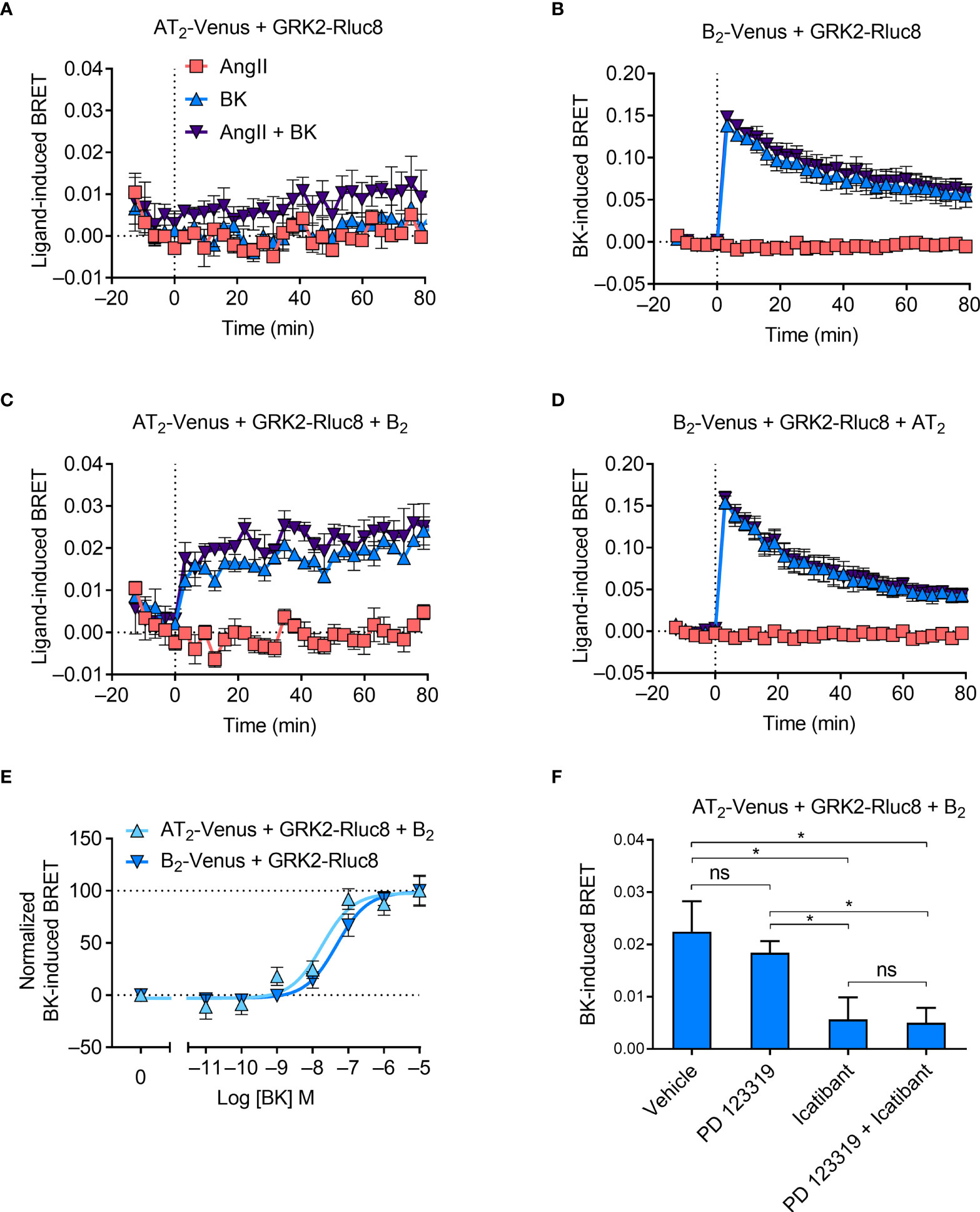

Following agonist stimulation, GPCR kinases (GRKs) are rapidly recruited to GPCRs, where they phosphorylate the receptor’s C terminal tail. This initiates receptor desensitization and interaction with β-arrestin proteins. We investigated GRK recruitment using BRET with Rluc8-tagged GRK2 (GRK2-Rluc8) and Venus-tagged receptors. There was no ligand-induced recruitment of GRK2-Rluc8 to the Venus-tagged AT2 receptor (AT2-Venus; Figure 5A). This lack of GRK2 recruitment is expected, as it is well known that the AT2 receptor does not recruit β-arrestin or internalize upon stimulation with AngII (43–45), and therefore it is unlikely it would recruit GRKs. In contrast, but also as expected, when cells expressing GRK2-Rluc8 and Venus-tagged B2 receptor (B2-Venus) were treated with BK (but not AngII) we saw an immediate increase in the BRET signal, indicating rapid recruitment of GRK2 to the B2 receptor (Figure 5B).

Figure 5 GRK2 recruitment to the AT2-B2 heteromer. HEK293FT cells were transfected with plasmid cDNA as described on graphs. (A–D) Time course analysis showing recruitment of GRK2-Rluc8 to receptors following addition of ligands at 0 mins. (E) Concentration-response analysis showing recruitment of GRK2-Rluc8 to receptors. Normalized data taken from BRET assays at 10 min after agonist addition. (F) GRK2-Rluc8 Receptor-HIT assay in the presence of 50 μM antagonists and 1 μM BK. Data are from BRET assays at 20 min after agonist addition. *p < 0.05; ns, not significant (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). All data are presented as mean ± SEM of ≥ three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

When we coexpressed untagged B2 receptor in cells expressing AT2-Venus and GRK2-Rluc8, we saw BK-induced recruitment of GRK2 proximal to the AT2 receptor (Figure 5C). Interestingly, this BRET signal had a much more sustained signal than that observed between GRK2-Rluc8 and B2-Venus (Figure 5B), which declined steadily over time. As with the mGsq Receptor-HIT assay, this Receptor-HIT signal indicates the close proximity of the AT2 receptor and the B2 receptor, and suggests their interaction within a heteromeric complex. Coexpression of untagged AT2 receptor did not alter the BRET signal between B2-Venus and GRK2-Rluc8 (Figure 5D) from that seen without AT2 expression (Figure 5B).

We also investigated the GRK2 Receptor-HIT signal further by conducting concentration-response analysis. Figure 5E shows that there is a significant leftward shift in the potency of GRK2 recruitment to AT2-B2 heteromers compared to B2 receptors (pEC50 ± SEM = 8.07 ± 008 vs. 7.35 ± 0.06, respectively; p < 0.05, unpaired t-test). When we conducted the GRK2 Receptor-HIT assay in the presence of selective antagonists (Figure 5F) we saw, as in the mGsq and Gαz Receptor-HIT assays, that the AT2 receptor antagonism did not inhibit the recruitment of GRK2 to AT2-B2 heteromers, while B2 receptor antagonism significantly reduced the level of GRK2 recruitment, indicating the specificity of the BRET signals.

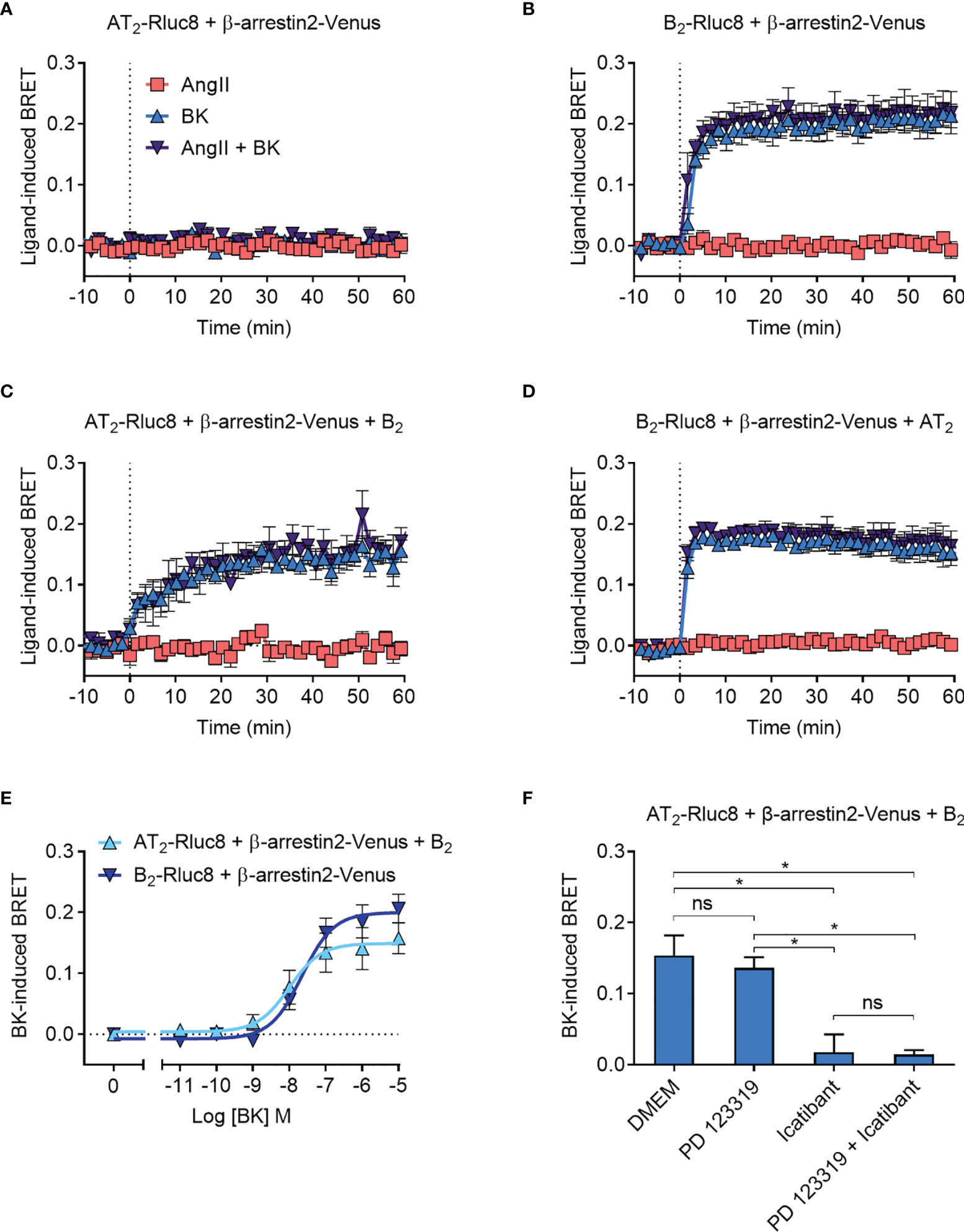

Following GRK recruitment and subsequent receptor phosphorylation, GPCRs recruit the scaffold protein β-arrestin, which desensitizes the receptor from classical cell surface G protein signaling and initiates internalization (46). Individual GPCRs have different β-arrestin recruitment profiles resulting in unique desensitization and internalization characteristics. Upon treatment with BK, the B2 receptor rapidly recruits β-arrestin leading to swift desensitization and extensive internalization (47, 48). In contrast and as already mentioned, the AT2 receptor does not recruit β-arrestin or internalize upon stimulation with AngII (43–45).

As expected, there was no ligand-induced recruitment of β-arrestin2-Venus to AT2-Rluc8 (Figure 6A), whereas when we coexpressed B2-Rluc8 with β-arrestin2 tagged with Venus (β-arrestin2-Venus) we observed strong and rapid BK-induced recruitment of β-arrestin2-Venus to B2-Rluc8 (Figure 6B). When AT2-Rluc8 was co-expressed with the untagged B2 receptor in the Receptor-HIT configuration, there was a marked increase in ligand-induced BRET when the cells were treated with BK but not AngII (Figure 6C), indicating BK-dependent translocation of β-arrestin2-Venus proximal to the B2 receptor. This BRET signal between AT2-Rluc8 and β-arrestin2-Venus confirms the close proximity of AT2-Rluc8 and the B2/β-arrestin2-Venus complex and is indicative of AT2-B2 heteromerization. Additionally, and similar to what was seen with GRK2, β-arrestin2-Venus recruitment to AT2-B2 heteromers had an altered kinetic profile to what was seen with B2 monomers/homomers. When we conducted the Receptor-HIT assay in the reverse configuration by coexpressing the untagged AT2 receptor with B2-Rluc8 and β-arrestin2-Venus there was no change in BRET signal (Figure 6D) from that seen without AT2 expression (Figure 6B).

Figure 6 β-arrestin2-Venus recruitment to the AT2-B2 heteromer. HEK293FT cells were transfected with plasmid cDNA as described on graphs. (A–D) Time course analysis showing recruitment of β-arrestin2-Venus to receptors following addition of ligands at 0 mins. (E) Concentration-response analysis showing recruitment of β-arrestin2-Venus to receptors. Data taken from BRET assays at 40 min after agonist addition. (F) β-arrestin2-Venus Receptor-HIT assay in the presence of 10 μM antagonists and 0.1 μM BK. Data taken from BRET assays at 40 min after agonist addition. *p < 0.05; ns, not significant (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). All data are presented as mean ± SEM of ≥ three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

To further investigate the β-arrestin2 Receptor-HIT signal we again conducted concentration-response analysis (Figure 6E). This showed that there was no significant difference in potency between BK-induced β-arrestin2-Venus recruitment to B2 receptors and AT2-B2 heteromers (pEC50 ± SEM = 7.64 ± 0.06 vs. 7.94 ± 0.19, respectively; p > 0.05, unpaired t-test). We then conducted the β-arrestin2 Receptor-HIT assay in the presence of selective antagonists. Similar to the previous Receptor-HIT assays, we saw that the BK-induced recruitment of β-arrestin2 to the AT2-B2 heteromer could be blocked by B2 receptor inhibition but not AT2 inhibition (Figure 6F), which demonstrates the importance of B2 receptor coexpression and activation.

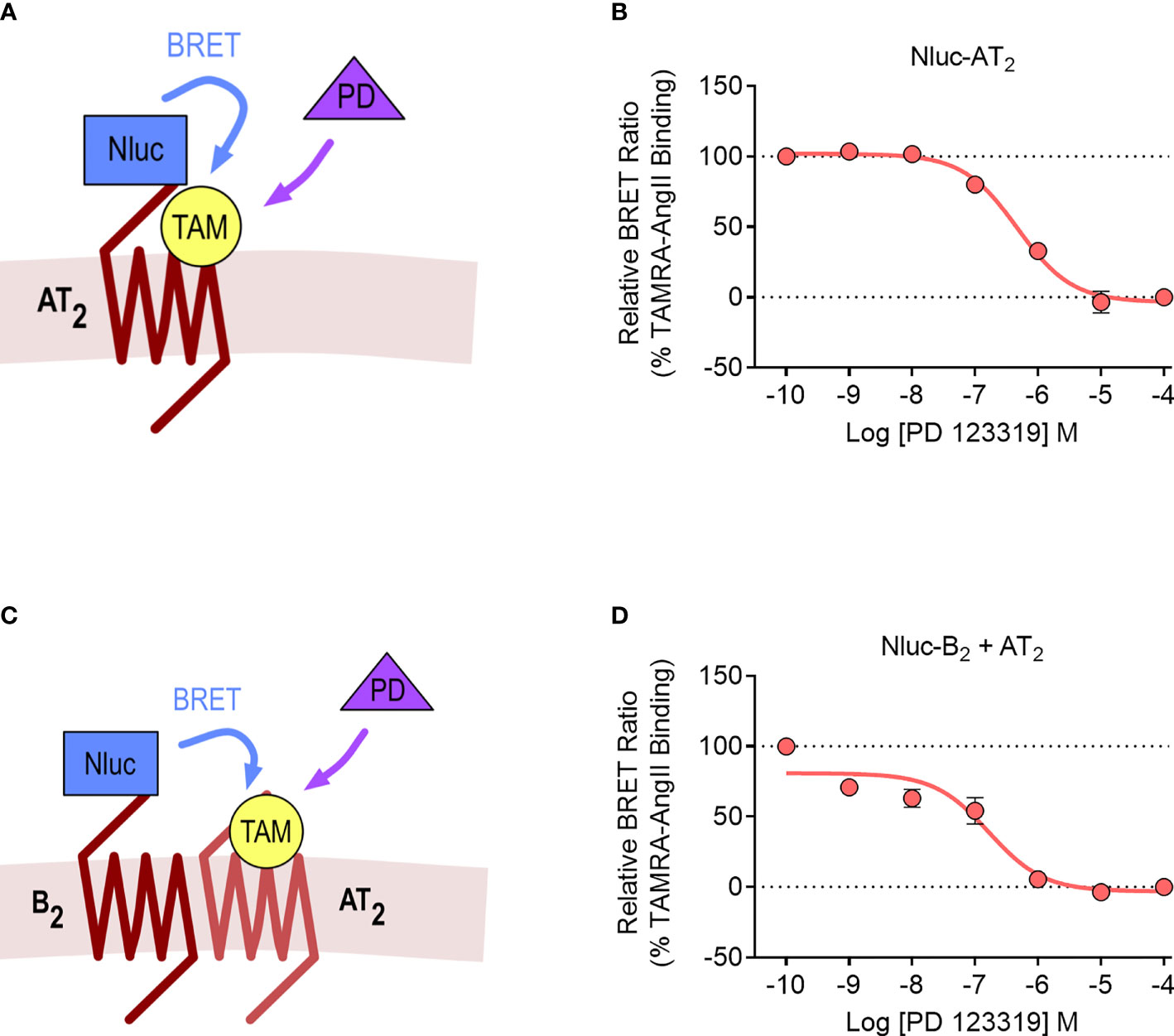

We lastly investigated the AT2-B2 heteromer using the NanoBRET ligand binding assay (28). In this assay, the NanoLuc (Nluc) luciferase (49) is fused to the N-terminus of a GPCR, and binding of fluorescent ligands can be detected with BRET. In our study, we fused Nluc to the N-terminus of the AT2 receptor (Nluc-AT2) and treated cells with an AngII analogue tagged with the TAMRA fluorophore (TAMRA-AngII) (Figures 7A, B). When we treated cells with increasing concentrations of the AT2 receptor antagonist PD 123319 in a competition binding assay, we were able to see a reduction in the BRET signal, indicating displacement of TAMRA-AngII binding to Nluc-AT2.

Figure 7 NanoBRET assay for detection of ligand binding to the AT2 receptor and the AT2-B2 heteromer. Depiction of the NanoBRET assay for detection of TAMRA-AngII (TAM) ligand binding to Nluc-AT2 (A) and AT2 receptors heteromerized with B2 receptors (using the Receptor-HIT assay) (C). HEK293FT cells were transfected with Nluc-AT2 and pcDNA3 (B) or Nluc-B2 and AT2 (D) and competition binding assays were conducted with TAMRA-AngII and PD 123319. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of ≥ three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

We then conducted the ligand binding assay in the Receptor-HIT configuration, as recently published (27). Here, Nluc was fused to the N-terminus of the B2 receptor (Nluc-B2) and was coexpressed with the untagged AT2 receptor. A BRET signal upon addition of TAMRA-AngII would indicate both the binding of TAMRA-AngII to the untagged AT2 receptor and also its close proximity to Nluc-B2, and this specific binding of TAMRA-AngII to AT2 receptors would be confirmed by displacement with PD 123319 (Figure 7C). When we conducted the assay, this was precisely what we observed, a TAMRA-AngII-induced BRET signal that could be displaced by increasing concentrations of PD 123319 (Figure 7D). When we compared the pIC50 values between cells expressing Nluc-AT2 and cells expressing Nluc-B2 and AT2 we found no significant differences (pIC50 ± SEM = 6.33 ± 0.10 vs. 6.84 ± 0.20, respectively; p > 0.05, unpaired t-test).

This study provides evidence for the existence of the AT2-B2 receptor heteromer in transfected HEK293FT cells. This is illustrated by the Receptor-HIT signals that show the requirement of B2 receptor coexpression and activation for recruitment of mGsq, GRK2 and β-arrestin2 proximal to the AT2 receptor. Evidence also came from the Gαz assay that demonstrated BK-induced modulation of B2 receptor/Gαz coupling, which was not present without AT2 receptor coexpression. Finally, the results of the heteromer ligand binding assay confirmed the close proximity of the two receptors at the cell surface, showing a Receptor-HIT signal between Nluc-B2 and TAMRA-AngII bound to AT2 receptors.

Perhaps the most interesting finding of this study was the novel G protein signaling pharmacology observed in the form of BK-induced modulation of B2 receptor/Gαz coupling that was not present without AT2 receptor coexpression. Following a search of the literature, we were unable to find any evidence that either the AT2 or the B2 receptor individually couple to Gαz, and this fits with the lack of ligand-induced interaction we observed in our BRET assays expressing only the single receptor. It is therefore particularly interesting that heteromerization may lead to new G protein coupling for both receptors. The Gαz protein is in the Gαi/o class of G proteins and therefore its canonical effect is inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and cAMP signaling (50). Gene and protein expression studies show that it is expressed at particularly high levels in the nervous system, and also at detectable levels in the gastrointestinal and reproductive systems as well as the adrenal gland and smooth muscle tissue (50, 51). There is therefore some overlap in expression profiles with the AT2 receptor and the B2 receptor, both of which are expressed in the brain, vasculature, adrenal gland and reproductive tissues (37, 38, 52). This suggests that the AT2-B2 heteromer could have physiological roles outside of the cardiovascular system, which is where most of the research into functional interactions between the two receptors has primarily been focused. In particular, the coexpression of Gαz and the two receptors in the nervous system is especially interesting, due to the growing appreciation of the functional role of the AT2 receptor in mediating neurological processes (53, 54). Indeed, an AT2 receptor antagonist progressed to Phase II clinical trials for the treatment of neuropathic pain (54, 55), although the trial had to be terminated due to toxicological concerns arising from pre-clinical data that only became available after the start of the trial (56). In addition, it is well established that the B2 receptor is also involved in the mediation of various types of pain, including neuropathic pain (57), and it is interesting to speculate on a possible involvement of the AT2-B2 heteromer in mediating pain or other neurological processes.

The AT2 receptor is an unusual GPCR in that it does not readily signal through G proteins, and nor does it undergo agonist-induced desensitization or internalization. In addition, despite decades of research, even the physiological effects mediated by the AT2 receptor are still not well understood. It is most commonly believed to antagonize many of the characteristic AngII/AT1-mediated actions, such as vasoconstriction, anti-natriuresis, growth and cell proliferation. However, numerous studies describe opposing effects of the AT2 receptor, reporting its mediation, rather than opposition of these effects (3). Despite these conflicting studies, one of the least controversial aspects of AT2 receptor pharmacology is its action as a vasodilator, via stimulation of the NO/cGMP signaling pathway (58). This is the same pathway used by the B2 receptor to mediate vasodilation following BK-induced activation of Gαq signaling (59). It is well known that BK can be involved in AT2 receptor-mediated NO signaling (22, 23), and the results of our study may provide further insight into this signaling cascade, demonstrating that Gαq can be recruited proximal to the AT2 receptor when it is heteromerized with the B2 receptor. Furthermore, a previous study has suggested that functional heteromerisation of these two receptors leads to enhanced NO signaling (24). The recruitment of mGsq proximal to the AT2 receptor within the AT2-B2 heteromer in our study, potentially provides a mechanism for this enhanced NO signal, as BK-mediated NO signaling could be mediated not only by B2 receptors but also by AT2-B2 heteromers. It is important to note that not all AT2 receptor-mediated NO signaling requires the presence of B2 receptors, as B2 receptor knockout mice can produce NO directly from AT2 receptors (21). This therefore indicates an alternate pathway used by the AT2 receptor to mediate NO signaling, which does not require the presence of B2 receptors, and may therefore not necessarily be directly impacted by AT2-B2 heteromerization.

An interesting recent study has revealed that β-arrestin2 is an integral component of an endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) signaling pathway (60). Here, β-arrestin2 was found to colocalize in sinusoidal endothelial cells with GPCR kinase interactor 1 and eNOS, stimulating eNOS activity in a ERK1/2- and Src-dependent manner. The study revealed that endothelin-1-mediated eNOS activity required β-arrestin2, and therefore it is likely that it is also involved in NO signaling by both the AT2 and the B2 receptor, as well as the AT2-B2 heteromer.

It is now well established that endocytosed GPCR-bound β-arrestins are able to aid in the initiation of signaling cascades through their function as scaffold proteins. Numerous signaling molecules are regulated through this property of β-arrestins, such as the MAPKs ERK, JNK, and p38. The AT2 receptor most commonly exerts inhibitory effects on MAPK cascades through activation of phosphatases (61–64). The potential for additional signaling through β-arrestin scaffolds adds another level of complexity to AT2 receptor signaling. Furthermore, this heteromerization-mediated recruitment of β-arrestin could explain some of the contradictory studies that report AT2-mediated activation of MAPKs (65, 66).

Coexpression of the AT2 receptor and the B2 receptor in the same cell is of course a primary requisite for formation of a heteromer. Expression of both receptors in endothelial cells is well documented (37, 67), and as both receptors initiate endothelium-mediated vasodilation via the NO/cGMP pathway (59), this is a probable location that we may expect functional AT2-B2 heteromers to be present. This is further supported by the previous heteromer study, which found that heteromerization of these two receptors resulted in enhanced NO signaling (24). Both receptors are also found in smooth muscle cells of the vasculature and in the heart, indicating the potential for heteromer formation in these cells, and further allowing for a role for the heteromer in the cardiovascular system. Beyond the cardiovascular system, the two receptors are also coexpressed in uterine smooth muscle cells, epithelial cells and fibroblasts (59, 68, 69), suggesting a broad range of cells the heteromer may be present in.

Although the AT2 receptor does not interact with the traditional GPCR interacting proteins, it is, however, known to interact with other signaling and regulatory proteins at its intracellular face. Interactions with the ErbB3 epidermal growth factor receptor (70), the scaffold protein connector enhancer of Ksr (71) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 (72) are implicated in AT2 receptor-mediated antigrowth effects, while interactions with the transcription factor promyelocytic zinc finger protein are involved in the mediation of cardiac hypertrophy (73). Interactions with the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE6 are important for AT2 receptor regulation of sodium levels (74), and interactions with AT2 receptor-interacting protein 1 result in antigrowth effects (75, 76) and neural differentiation (77). It is possible that when the AT2 receptor is heteromerized with the B2 receptor, recruitment and interaction with the proteins investigated in this study (Gαq, Gαz, GRK2 and β-arrestin2) could modulate the above AT2 receptor interactions, leading to alterations in signaling. In addition, many studies reveal that the AT2 receptor is constitutively active (65, 78–81). If recruitment and interaction of the proteins in this study to the AT2-B2 heteromer were able to block the interaction between the AT2 receptor and its various signaling partners, this would be a mechanism of reducing the constitutive activity observed for this receptor.

Despite decades of research, the AT2 receptor remains incompletely characterized in terms of its molecular pharmacology and its physiological functions (2, 3). Its lack of canonical GPCR pharmacology, such as agonist-induced G protein coupling, desensitization and internalization, make it a unique and enigmatic receptor within the field. The antagonist assays conducted in this study initially suggested that it has a somewhat silent role within the heteromer, as in every functional assay we investigated, B2 activation but not AT2 activation was required for the heteromer response. However, the Gαz results demonstrate an important functional role of the AT2 receptor within the heteromer, as it confers novel Gαz coupling to the B2 receptor. This is indicative of bi-directional modulation within the heteromer, as both the presence of the AT2 receptor and activation of the B2 receptor is required for modulation of Gαz proximity.

In summary, we have provided evidence for the existence of the AT2-B2 heteromer and have demonstrated some of its apparent novel pharmacology. Extension of these findings beyond HEK293FT cells to more physiologically relevant systems will enable further characterization of the pharmacology mediated by the heteromer. Heteromerization of the AT2 and B2 receptors likely underpins some of the functional crosstalk observed between the receptors in the cardiovascular system, and it is possible that the heteromer may also have physiological roles in other areas of the body, such as the nervous system. AT2-B2 heteromerization is a newly identified mechanism for the enigmatic and poorly characterized AT2 receptor to be functionally active within cells.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

EKMJ, MAA, RJH, HBS and RSA conducted the experiments and analyzed the results. EKMJ, MAA, RMS and KDGP conceived the experiments. EKMJ and KDGP wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

This work was funded in part by the Australian Research Council (ARC; DP120101297 and FT100100271) and Dimerix Bioscience Pty Ltd. Dimerix was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication. EJ was funded for part of this work by the Richard Walter Gibbon Medical Research Scholarship from The University of Western Australia and by an ARC Centre for Personalised Therapeutics Technologies (IC170100016) postdoctoral fellowship.

KP has a shareholding in Dimerix Limited, a spin-out company of The University of Western Australia that owns intellectual property relating to the Receptor-HIT technology and that partially funded this work. KP is Chief Scientific Advisor to Dimerix. KP, ES and RS are named inventors on patents covering the Receptor-HIT technology (WO/2008/055313 Detection System and Uses Therefor).

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Dinh D, Frauman A, Johnston C, Fabiani M. Angiotensin Receptors: Distribution, Signalling and Function. Clin Sci (2001) 100(5):481–92. doi: 10.1042/CS20000263

2. Lemarié CA, Schiffrin EL. The Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor in Cardiovascular Disease. J Renin-Angio-Aldo S (2010) 11(1):19–31. doi: 10.1177/1470320309347785

3. Porrello E, Delbridge LMD, Thomas W. The Angiotensin II Type 2 [AT(2)] Receptor: An Enigmatic Seven Transmembrane Receptor. Front Biosci (2009) 4(3):958–72. doi: 10.2741/3289

4. AbdAlla S, Lother H, Abdel-tawab AM, Quitterer U. The Angiotensin II AT2 Receptor Is an AT1 Receptor Antagonist. J Biol Chem (2001) 276(43):39721–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105253200

5. Porrello ER, Pfleger KDG, Seeber RM, Qian H, Oro C, Abogadie F, et al. Heteromerization of Angiotensin Receptors Changes Trafficking and Arrestin Recruitment Profiles. Cell Signal (2011) 23(11):1767–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.06.011

6. Kumar V, Knowle D, Gavini N, Pulakat L. Identification of the Region of AT2 Receptor Needed for Inhibition of the AT1 Receptor-Mediated Inositol 1,4,5-Triphosphate Generation. FEBS Lett (2002) 532(3):379–86. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03713-4

7. Zhang X, Wang G, Dupré DJ, Feng Y, Robitaille M, Lazartigues E, et al. Rab1 GTPase and Dimerization in the Cell Surface Expression of Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Therap (2009) 330(1):109–17. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.153460

8. Axelband F, Assunção-Miranda I, de Paula IR, Ferrão FM, Dias J, Miranda A, et al. Ang-(3-4) Suppresses Inhibition of Renal Plasma Membrane Calcium Pump by Ang II. Regul Peptides (2009) 155(1-3):81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.03.014

9. Yang J, Chen C, Ren H, Han Y, He D, Zhou L, et al. Angiotensin II AT(2) Receptor Decreases AT(1) Receptor Expression and Function via Nitric Oxide/cGMP/Sp1 in Renal Proximal Tubule Cells From Wistar-Kyoto Rats. J Hypertens (2012) 30(6):1176–84. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283532099

10. Ferrão FM, Lara LS, Axelband F, Dias J, Carmona AK, Reis RI, et al. Exposure of Luminal Membranes of LLC-PK1 Cells to ANG II Induces Dimerization of AT1/AT2 Receptors to Activate SERCA and to Promote Ca2+ Mobilization. Am J Physiol Renal (2012) 302(7):F875–83. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00381.2011

11. Inuzuka T, Fujioka Y, Tsuda M, Fujioka M, Satoh AO, Horiuchi K, et al. Attenuation of Ligand-Induced Activation of Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptor Signaling by the Type 2 Receptor via Protein Kinase C. Sci Rep (2016) 6:21613. doi: 10.1038/srep21613

12. AbdAlla S, Lother H, Quitterer U. AT1-Receptor Heterodimers Show Enhanced G-Protein Activation and Altered Receptor Sequestration. Nature (2000) 407(6800):94–8. doi: 10.1038/35024095

13. AbdAlla S, Lother H, el Massiery A, Quitterer U. Increased AT(1) Receptor Heterodimers in Preeclampsia Mediate Enhanced Angiotensin II Responsiveness. Nat Med (2001) 7(9):1003–9. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1003

14. AbdAlla S, Abdel-Baset A, Lother H, Massiery A, Quitterer U. Mesangial AT1/B2 Receptor Heterodimers Contribute to Angiotensin II Hyperresponsiveness in Experimental Hypertension. J Mol Neurosci (2005) 26(2-3):185–92. doi: 10.1385/JMN:26:2-3:185

15. AbdAlla J, Reeck K, Langer A, Streichert T, Quitterer U. Calreticulin Enhances B2 Bradykinin Receptor Maturation and Heterodimerization. Biochem Biophys Res Comm (2009) 387(1):186–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.07.011

16. Abd Alla J, Pohl A, Reeck K, Streichert T, Quitterer U. Establishment of an In Vivo Model Facilitates B2 Receptor Protein Maturation and Heterodimerization. Integrat Bio (2010) 2(4):209–17. doi: 10.1039/B922592G

17. Quitterer U, Pohl A, Langer A, Koller S, AbdAlla S. A Cleavable Signal Peptide Enhances Cell Surface Delivery and Heterodimerization of Cerulean-Tagged Angiotensin II AT1 and Bradykinin B2 Receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Comm (2011) 409(3):544–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.05.041

18. Wilson PC, Lee M-H, Appleton KM, El-Shewy HM, Morinelli TA, Peterson YK, et al. The Arrestin-Selective Angiotensin AT1 Receptor Agonist [Sar1,Ile4,Ile8]-AngII Negatively Regulates Bradykinin B2 Receptor Signaling via AT1-B2 Receptor Heterodimers. J Biol Chem (2013) 288(26):18872–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.472381

19. Quitterer U, AbdAlla S. Analysis of A1–B2 Receptor Heterodimerization in Transgenic Mice. Exp Clin Cardiol (2014) 20(1):1626–34.

20. Widdop R, Jones ES, Hannan RE, Gaspari TA, Jones E, Hannan R, et al. Angiotensin AT2 Receptors: Cardiovascular Hope or Hype? Br J Pharmacol (2003) 140(5):809–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705448

21. Abadir PM, Carey RM, Siragy HM. Angiotensin AT2 Receptors Directly Stimulate Renal Nitric Oxide in Bradykinin B2-Receptor-Null Mice. Hypertension (2003) 42(4):600–4. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000090323.58122.5C

22. Batenburg WW, Tom B, Schuijt MP, Danser AHJ. Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor-Mediated Vasodilation. Focus on Bradykinin, NO and Endothelium-Derived Hyperpolarizing Factor(s). Vascul Pharmacol (2005) 42(3):109–18. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2005.01.005

23. Siragy HM, de Gasparo M, Carey RM. Angiotensin Type 2 Receptor Mediates Valsartan-Induced Hypotension in Conscious Rats. Hypertension (2000) 35(5):1074–7. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.35.5.1074

24. Abadir P, Periasamy A, Carey R, Siragy H. Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor-Bradykinin B-2 Receptor Functional Heterodimerization. Hypertension (2006) 48(2):316–22. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000228997.88162.a8

25. Johnstone EKM, Pfleger KDG. Receptor-Heteromer Investigation Technology and Its Application Using BRET. Front Endocrin (2012) 3:101. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00101

26. Johnstone EKM, Pfleger KDG. Profiling Novel Pharmacology of Receptor Complexes Using Receptor-HIT. Biochem Soc Trans (2021) 49(4):1555–65. doi: 10.1042/BST20201110

27. Johnstone EKM, See HB, Abhayawardana RS, Song A, Rosengren KJ, Hill SJ, et al. Investigation of Receptor Heteromers Using NanoBRET Ligand Binding. Int J Mol Sci (2021) 22(3):1082. doi: 10.3390/ijms22031082

28. Stoddart LA, Johnstone EKM, Wheal AJ, Goulding J, Robers MB, Machleidt T, et al. Application of BRET to Monitor Ligand Binding to GPCRs. Nat Meth (2015) 12(7):661–3. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3398

29. See HB, Seeber RM, Kocan M, Eidne KA, Pfleger KDG. Application of G Protein-Coupled Receptor-Heteromer Identification Technology to Monitor B-Arrestin Recruitment to G Protein-Coupled Receptor Heteromers. Assay Drug Dev Techn (2011) 9(1):21–30. doi: 10.1089/adt.2010.0336

30. Mustafa S, See HB, Seeber RM, Armstrong SP, White CW, Ventura S, et al. Identification and Profiling of Novel α1a-Adrenoceptor-CXC Chemokine Receptor 2 Heteromer. J Biol Chem (2012) 287(16):12952–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.322834

31. Ayoub MA, Zhang Y, Kelly RS, See HB, Johnstone EKM, McCall EA, et al. Functional Interaction Between Angiotensin II Receptor Type 1 and Chemokine (C-C Motif) Receptor 2 With Implications for Chronic Kidney Disease. PloS One (2015) 10(3):e0119803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119803

32. Ayoub MA, Pfleger KDG. Recent Advances in Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer Technologies to Study GPCR Heteromerization. Curr Opin Pharmacol (2010) 10(1):44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.09.012

33. Loening A, Fenn T, Wu A, Gambhir S. Consensus Guided Mutagenesis of Renilla Luciferase Yields Enhanced Stability and Light Output. Protein Eng Des Sel (2006) 19(9):391–400. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzl023

34. Kocan M, See HB, Seeber RM, Eidne KA, Pfleger KDG. Demonstration of Improvements to the Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET) Technology for the Monitoring of G Protein-Coupled Receptors in Live Cells. J Biomol Screen (2008) 13(9):888–98. doi: 10.1177/1087057108324032

35. Olsen RHJ, DiBerto JF, English JG, Glaudin AM, Krumm BE, Slocum ST, et al. TRUPATH, an Open-Source Biosensor Platform for Interrogating the GPCR Transducerome. Nat Chem Biol (2020) 16(8):841–9. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0535-8

36. Pfleger KDG, Eidne KA. Illuminating Insights Into Protein-Protein Interactions Using Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET). Nat Meth (2006) 3(3):165–74. doi: 10.1038/nmeth841

37. Leeb-Lundberg LMF, Marceau F, Muller-Esterl W, Pettibone DJ, Zuraw BL. International Union of Pharmacology. XLV. Classification of the Kinin Receptor Family: From Molecular Mechanisms to Pathophysiological Consequences. Pharmacol Rev (2005) 57(1):27–77. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.1.2

38. Karnik SS, Unal H, Kemp JR, Tirupula KC, Eguchi S, Vanderheyden PML, et al. Angiotensin Receptors: Interpreters of Pathophysiological Angiotensinergic Stimuli. Pharmacol Rev (2015) 67(4):754–819. doi: 10.1124/pr.114.010454

39. Drube S, Liebmann C. In Various Tumour Cell Lines the Peptide Bradykinin B-2 Receptor Antagonist, Hoe 140 (Icatibant), May Act as Mitogenic Agonist. Br J Pharmacol (2000) 131(8):1553–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703764

40. Galés C, Van Durm JJJ, Schaak S, Pontier S, Percherancier Y, Audet M, et al. Probing the Activation-Promoted Structural Rearrangements in Preassembled Receptor-G Protein Complexes. Nat Struct Mol Biol (2006) 13(9):778–86. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1134

41. Johnstone EKM, Pfleger KDG. Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer Approaches to Discover Bias in GPCR Signaling. 1335. New York, NY: Springer New York (2015) p. 191–204.

42. Ayoub MA, Trinquet E, Pfleger KDG, Pin JP. Differential Association Modes of the Thrombin Receptor PAR1 With Galphai1, Galpha12, and Beta-Arrestin 1. FASEB J (2010) 24(9):3522–35. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-154997

43. Turu G, Szidonya L, Gáborik Z, Buday L, Spät A, Clark AJL, et al. Differential [Beta]-Arrestin Binding of AT1 and AT2 Angiotensin Receptors. FEBS Lett (2006) 580(1):41–5. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.044

44. Pucell AG, Hodges JC, Sen I, Bumpus FM, Husain A. Biochemical Properties of the Ovarian Granulosa Cell Type 2-Angiotensin II Receptor. Endocrinology (1991) 128(4):1947–59. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-4-1947

45. Hunyady L, Bor M, Balla T, Catt KJ. Identification of a Cytoplasmic Ser-Thr-Leu Motif That Determines Agonist-Induced Internalization of the AT1 Angiotensin Receptor. J Biol Chem (1994) 269(50):31378–82. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)31704-6

46. DeWire SM, Ahn S, Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. Beta-Arrestins and Cell Signaling. Annu Rev Physiol (2007) 69:483–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154749

47. Mathis SA, Criscimagna NL, LeebLundberg LMF, Leeb Lundberg LM. B1 and B2 Kinin Receptors Mediate Distinct Patterns of Intracellular Ca2+ Signaling in Single Cultured Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Mol Pharmacol (1996) 50(1):128–39.

48. Enquist J, Skroder C, Whistler JL, Leeb-Lundberg MF. Kinins Promote B-2 Receptor Endocytosis and Delay Constitutive B-1 Receptor Endocytosis. Mol Pharmacol (2007) 71(2):494–507. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030858

49. Hall MP, Unch J, Binkowski BF, Valley MP, Butler BL, Wood MG, et al. Engineered Luciferase Reporter From a Deep Sea Shrimp Utilizing a Novel Imidazopyrazinone Substrate. ACS Chem Biol (2012) 7(11):1848–57. doi: 10.1021/cb3002478

50. Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. Mammalian G Proteins and Their Cell Type Specific Functions. Physiol Rev (2005) 85(4):1159–204. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2005

51. Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-Based Map of the Human Proteome. Science (2015) 347(6220):1260419–. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419

52. Costa-Neto CM, Duarte DA, Lima V, Maria AG, Prando EC, Rodríguez DY, et al. Non-Canonical Signalling and Roles of the Vasoactive Peptides Angiotensins and Kinins. Clin Sci (2014) 126(11):753–74. doi: 10.1042/CS20130414

53. Guimond M-O, Gallo-Payet N. The Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor in Brain Functions: An Update. Int J Hypertens (2012) 2012(6):351758–18. doi: 10.1155/2012/351758

54. Smith MT, Muralidharan A. Targeting Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor Pathways to Treat Neuropathic Pain and Inflammatory Pain. Expert Opin Ther Targets (2015) 19(1):25–35. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.957673

55. Rice ASC, Dworkin RH, McCarthy TD, Anand P, Bountra C, McCloud PI, et al. EMA401, an Orally Administered Highly Selective Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor Antagonist, as a Novel Treatment for Postherpetic Neuralgia: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 Clinical Trial. Lancet (2014) 383(9929):1637–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62337-5

56. Pulakat L, Sumners C. Angiotensin Type 2 Receptors: Painful, or Not? Front Pharmacol (2020) 11:571994. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.571994

57. Petho G, Reeh PW. Sensory and Signaling Mechanisms of Bradykinin, Eicosanoids, Platelet-Activating Factor, and Nitric Oxide in Peripheral Nociceptors. Physiol Rev (2012) 92(4):1699–775. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00048.2010

58. Carey RM. AT2 Receptors: Potential Therapeutic Targets for Hypertension. Am J Hypertens (2017) 30(4):339–47. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpw121

59. Blaes N, Girolami J-P. Targeting the "Janus Face" of the B2-Bradykinin Receptor. Expert Opin Ther Targets (2013) 17(10):1145–66. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.827664

60. Liu S, Luttrell LM, Premont RT, Rockey DC. β-Arrestin2 Is a Critical Component of the GPCR–eNOS Signalosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2020) 117(21):11483–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1922608117

61. Huang XC, Richards EM, Sumners C. Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor-Mediated Stimulation of Protein Phosphatase 2A in Rat Hypothalamic/Brainstem Neuronal Cocultures. J Neurochem (1995) 65(5):2131–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65052131.x

62. Bedecs K, Elbaz N, Sutren M, Masson M, Susini C, Strosberg AD, et al. Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptors Mediate Inhibition of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Cascade and Functional Activation of SHP-1 Tyrosine Phosphatase. Biochem J (1997) 325(Pt 2):449–54. doi: 10.1042/bj3250449

63. Bottari SP, King IN, Reichlin S, Dahlstroem I, Lydon N, de Gasparo M. The Angiotensin AT2 Receptor Stimulates Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Activity and Mediates Inhibition of Particulate Guanylate Cyclase. Biochem Biophys Res Comm (1992) 183(1):206–11. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(92)91629-5

64. Matsubara H, Shibasaki Y, Okigaki M, Mori Y, Masaki H, Kosaki A, et al. Effect of Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor on Tyrosine Kinase Pyk2 and C-Jun NH2-Terminal Kinase via SHP-1 Tyrosine Phosphatase Activity: Evidence From Vascular-Targeted Transgenic Mice of AT2 Receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Comm (2001) 282(5):1085–91. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4695

65. Miura S, Karnik SS. Ligand-Independent Signals From Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor Induce Apoptosis. EMBO J (2000) 19(15):4026–35. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.4026

66. Miyamoto N, Zhang N, Tanaka R, Liu M, Hattori N, Urabe T. Neuroprotective Role of Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor After Transient Focal Ischemia in Mice Brain. Neurosci Res (2008) 61(3):249–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2008.03.003

67. Kaschina E, Namsolleck P, Unger T. AT2 Receptors in Cardiovascular and Renal Diseases. Pharmacol Res (2017) 125(Pt A):39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.07.008

68. de Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, Wright JW, Unger T. International Union of Pharmacology. XXIII. The Angiotensin II Receptors. Pharmacol Rev (2000) 52(3):415–72.

69. Zhao Y, Lützen U, Fritsch J, Zuhayra M, Schütze S, Steckelings Ulrike M, et al. Activation of Intracellular Angiotensin AT2 Receptors Induces Rapid Cell Death in Human Uterine Leiomyosarcoma Cells. Clin Sci (2015) 128(9):567–78. doi: 10.1042/CS20140627

70. Knowle D, Ahmed S, Pulakat L. Identification of an Interaction Between the Angiotensin II Receptor Sub-Type AT2 and the ErbB3 Receptor, A Member of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Family. Regul Peptides (2000) 87(1-3):73–82. doi: 10.1016/S0167-0115(99)00111-1

71. Fritz RD, Radziwill G. The Scaffold Protein CNK1 Interacts With the Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Comm (2005) 338(4):1906–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.168

72. Kang K-H, Park S-Y, Rho SB, Lee J-H. Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases-3 Interacts With Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor and Additively Inhibits Angiogenesis. Cardiovasc Res (2008) 79(1):150–60. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn072

73. Senbonmatsu T, Saito T, Landon EJ, Watanabe O, Price E. A Novel Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor Signaling Pathway: Possible Role in Cardiac Hypertrophy. EMBO J (2003) 22(24):6471–82. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg637

74. Pulakat L, Cooper S, Knowle D, Mandavia C, Bruhl S, Hetrick M, et al. Ligand-Dependent Complex Formation Between the Angiotensin II Receptor Subtype AT2 and Na+/H+ Exchanger NHE6 in Mammalian Cells. Peptides (2005) 26(5):863–73. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.12.015

75. Nouet S, Amzallag N, Li JM, Louis S, Seitz I. Trans-Inactivation of Receptor Tyrosine Kinases by Novel Angiotensin II AT2 Receptor-Interacting Protein, ATIP. J Biol Chem (2004) 279(28):28989–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403880200

76. Fujita T, Mogi M, Min L-J, Iwanami J, Tsukuda K, Sakata A, et al. Attenuation of Cuff-Induced Neointimal Formation by Overexpression of Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor-Interacting Protein 1. Hypertens (2009) 53(4):688–93. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.128140

77. Li J-M, Mogi M, Tsukuda K, Tomochika H, Iwanami J, Min L-J, et al. Angiotensin II-Induced Neural Differentiation via Angiotensin II Type 2 (AT2) Receptor-MMS2 Cascade Involving Interaction Between AT2 Receptor-Interacting Protein and Src Homology 2 Domain-Containing Protein-Tyrosine Phosphatase 1. Mol Endocrin (2007) 21(2):499–511. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0005

78. Jin X-Q, Fukuda N, Su J-Z, Lai Y-M, Suzuki R, Tahira Y, et al. Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor Gene Transfer Downregulates Angiotensin II Type 1a Receptor in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Hypertension (2002) 39(5):1021–7. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000016179.52601.B4

79. Su J-Z, Fukuda N, Jin X-Q, Lai Y-M, Suzuki R, Tahira Y, et al. Effect of AT2 Receptor on Expression of AT1 and TGF-Beta Receptors in VSMCs From SHR. Hypertension (2002) 40(6):853–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000042096.17141.B1

80. Miura S, Karnik SS. Angiotensin II Type 1 and Type 2 Receptors Bind Angiotensin II Through Different Types of Epitope Recognition. J Hypertens (1999) 17(3):397–404. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917030-00013

Keywords: angiotensin receptor, bradykinin receptor, GPCR, BRET, receptor-HIT, heteromer, NanoBRET

Citation: Johnstone EKM, Ayoub MA, Hertzman RJ, See HB, Abhayawardana RS, Seeber RM and Pfleger KDG (2022) Novel Pharmacology Following Heteromerization of the Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor and the Bradykinin Type 2 Receptor. Front. Endocrinol. 13:848816. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.848816

Received: 05 January 2022; Accepted: 21 March 2022;

Published: 26 May 2022.

Edited by:

Martyna Szpakowska, Luxembourg Institute of Health, LuxembourgReviewed by:

Diego Guidolin, University of Padua, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Johnstone, Ayoub, Hertzman, See, Abhayawardana, Seeber and Pfleger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elizabeth K. M. Johnstone, bGl6LmpvaG5zdG9uZUB1d2EuZWR1LmF1; Kevin D. G. Pfleger, a2V2aW4ucGZsZWdlckB1d2EuZWR1LmF1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.