94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CASE REPORT article

Front. Endocrinol. , 28 February 2022

Sec. Pediatric Endocrinology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.810375

SOX3 is critical for the development of the pituitary, brain, and face, and SOX3 mutations may lead to hypopituitarism, intellectual disability, and craniofacial abnormalities. Common SOX3 mutations are duplications and deletions of the whole or part of SOX3, yet only a few cases with point mutations were reported by far. We present a case with growth retardation, small penis, and learning difficulty. Further assessment confirmed growth hormone deficiency, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (HH), and borderline intellectual disability. He also responded well to gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulation test, which suggests defects in the hypothalamus, contrary to previous studies that reported defects in the pituitary. A pathogenic frame-shift mutation of SOX3 was found. A heterogeneous missense mutation in SEMA3A was identified in this patient as well, which may also contribute to the development of HH. As far as we know, this is the first report that a frame-shift mutation of SOX3 constitutes rare genetic causes of HH and growth hormone deficiency. Whether mutations in these two genes act synergistically in the pathogenesis of the patient’s phenotype remains to be further investigated. We believe that our case extends the phenotypic spectrum and genetic variability of SOX3 mutation.

SOX3 is a member of the SOX (SRY-related high-mobility group box) family of transcription factors located on the X chromosome and is expressed in the developing central nervous system from early stages of development (1, 2). It has a short N-terminal domain and a longer C-terminal domain containing four polyalanine tracts involved in transcriptional activation (1). SOX3 is critical for normal development of the pituitary, brain, and face in both mice and humans (3). A range of phenotypes are associated with SOX3 mutations in humans, including hypopituitarism ranging from isolated growth hormone deficiency to panhypopituitarism, intellectual disability, and craniofacial abnormalities (4). Almost all the subjects developed clinical symptoms before puberty. Common SOX3 mutations are duplications and deletions of the whole or part of SOX3, yet point mutations of SOX3 are rarely reported. This is the first report of a SOX3 frame-shift mutation in a patient with growth retardation, delayed puberty, and learning difficulty.

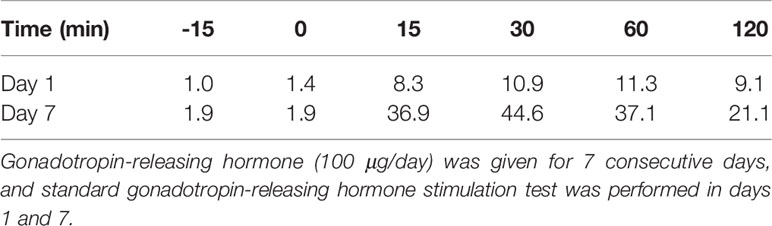

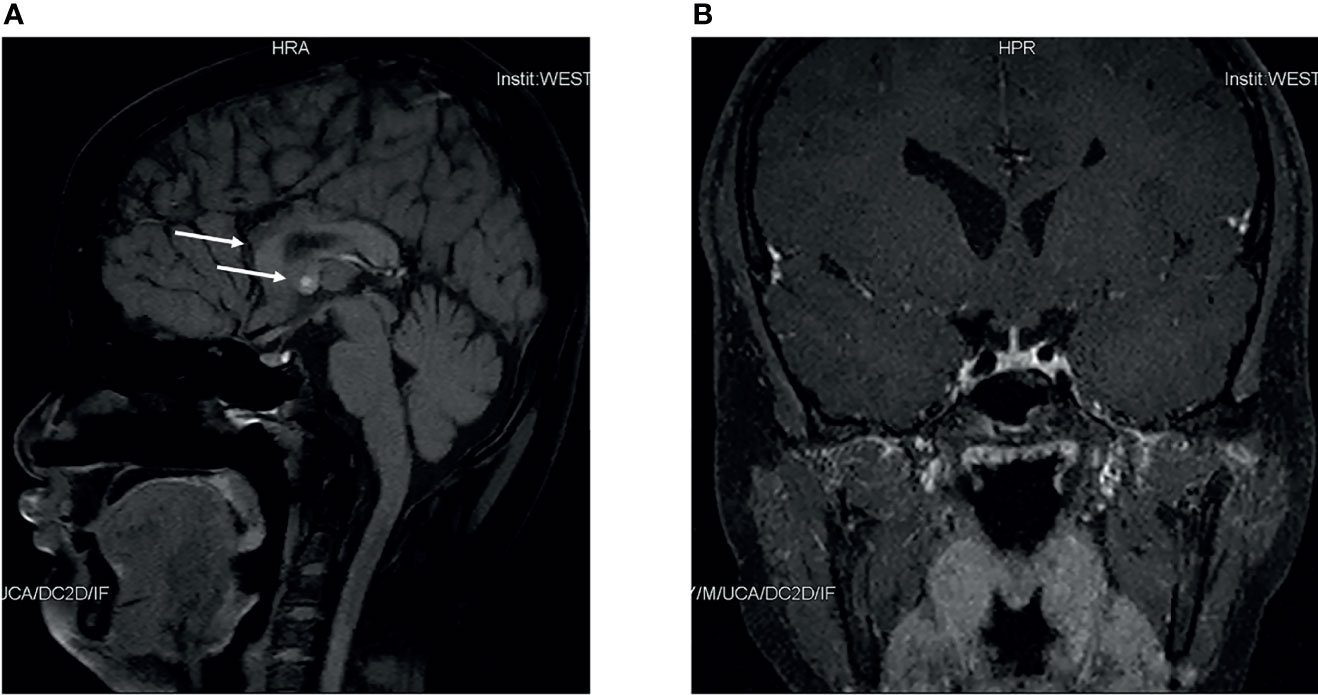

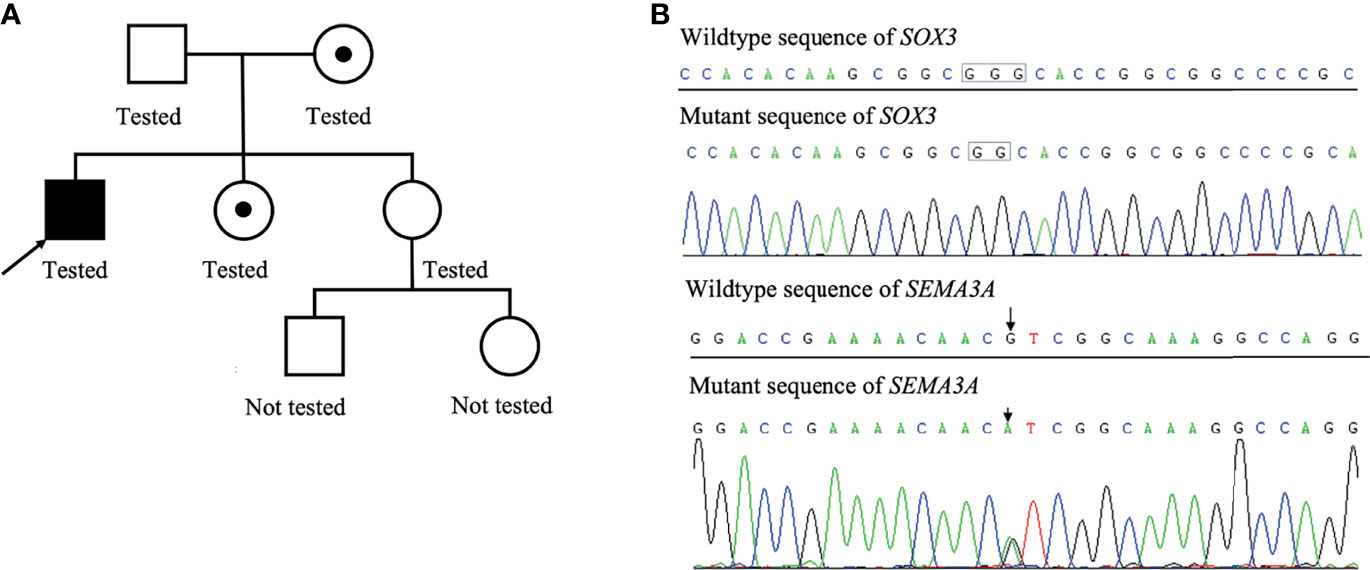

A Chinese boy was found to have short stature and poor performance at school when he was 7 years old. He was born at full term after an uncomplicated pregnancy. His parents were non-consanguineous. He was diagnosed with omphalitis 2 days after birth and recovered after being treated with antibiotics. The patient’s mother was not sure about his mental and physical development before 7 years of age. So he went to a local hospital, yet diagnosis and treatment were unknown, and no improvement was achieved. At the age of 14 years, he was found to have gynecomastia and was admitted to the West China Second University Hospital. He was 147 cm tall and 38.5 kg at that time. Further evaluations revealed that he had normal estradiol (27.6 pg/ml, reference range: 0–39.8), low testosterone (0.23 ng/ml, reference range: 2.41–8.27), low luteinizing hormone (LH; 1.4 IU/l, reference range: 1.5–9.3), and normal follicular stimulating hormone (FSH; 2.5 IU/L, reference range: 1.4–18.1). His growth hormone (GH) was 0.50 ng/ml, and the insulin-like growth factor was 297.0 ng/ml (reference range: 221–904 ng/ml for subjects aged 13–18 years). The GH stimulation test confirmed GH deficiency because the peak GH after stimulation was 2.40 ng/ml, yet we were not sure how the GH stimulation test was performed. He had normal thyroid and adrenocortical function. He was administered recombinant GH 4IU per day consecutively for 3 months, and later for the inconvenience of injection, he used recombinant GH irregularly. We were not sure about the dose and frequency of recombinant GH he used after the first 3 months. His height increased from 147 to 160 cm in 2 years, and there was no change in the recent 2 years. He was admitted to the West China Hospital complaining of gynecomastia and small penis at the age of 18 years. Physical examination showed that he was 160 cm tall and 54 kg, had a high-pitched voice, and hand span of 162 cm. Pubic hair and external genitalia development were both stage I in the Tanner stage. Bilateral breast enlargement was found without galactorrhea or overlying skin changes. His olfaction was normal. Complete blood count, biochemical profiles, and urinalysis showed nothing remarkable. Random measurement of sex hormone indicated very low testosterone and decreased LH and FSH. Prolactin level and thyroid function were normal. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) was 21.10 ng/l, and morning cortisol was 291 nmol/l. Bone age was 14 years, which was considerably delayed. The gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) stimulation test using 100 μg gonadorelin intravenously showed that the peak LH was 11.3 mIU/ml at 60 min, compared with 1.0 mIU/ml at baseline. The repetitive GnRH loading test was performed in which 100 μg gonadorelin was administered intravenously for 7 consecutive days, and in day 7, another standard GnRH stimulation test was performed (Table 1). The peak LH was 44.6 mIU/ml at 30 min. To further evaluate the pituitary adrenal axis and GH secretion, the GH stimulation test by insulin-induced hypoglycemia showed poor GH reserve (peak 1.87 ng/ml) and slightly blunted adrenocortical reserve, with the peak cortisol to be 487 nmol/l (Table 2). Human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) was administered 2,000 IU per day intravenously for 3 consecutive days, and fasting blood was drawn on the 4th day which indicated that testosterone increased from 0.06 to 2.06 ng/ml. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated nothing abnormal in the sellar area, dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, and a small nodule in the septum pellucidum (Figure 1). Cognitive assessment using full-scale intelligence quotient showed a score of 72, which was borderline, very close to intellectual disability. Whole-exome sequencing indicated a hemizygous frame-shift mutation of SOX3 (c.287 delG, p.G96Afs*44) located in chromosome X, resulting in the change of 44 amino acid residues between codons 96 and 139 (Figure 2). The mutation was highly pathogenic, and this variant was not found in the Exome Aggregation Consortium, dbSNP, 1000 Genomes project, or in-house databases. A heterogeneous point mutation of SEMA3A (c.2198G>R) was also identified by Sanger sequencing, which resulted in a missense mutation (p.R733H). His mother was confirmed to have the same mutation in SOX3 and SEMA3A, and one of his elder sisters had the same mutation in SEMA3A. Sanger sequencing of his father and the other elder sister turned negative. His mother had a history of schizophrenia and was well-controlled by antipsychotic medication. Otherwise, his mother was quite healthy. She reached her target height, had normal menstruation before menopause, and gave birth to two daughters and one son after natural conception. Although a cognitive assessment was not performed, she behaved normally and had no difficulty in working and taking care of her children. His father and two elder sisters were phenotypically normal. For the treatment of this patient, the short-term goal was to help him achieve puberty induction and sexual maturation, and the long-term goal was to achieve induction of fertility. Since testosterone replacement does not restore normal spermatogenesis in men with GnRH deficiency, and fertility was desired by the patient, he was prescribed 1,500 IU of HCG twice a week after discharge. He was not administered with GnRH since GnRH was very expensive. For the short follow-up time after administration of HCG, we were not sure whether he responded well to the treatment.

Table 1 Level of luteinizing hormone (mIU/mL) after the gonadotropin-releasing hormone loading test.

Figure 1 Pituitary magnetic resonance imaging of this patient. Sagittal magnetic resonance imaging scans of this patient (A) indicated dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, and a small nodule in septum pellucidum. Coronal scans of this patient (B) indicated nothing abnormal.

Figure 2 Family pedigree of this patient (A). The patient’s mother was the carrier of a heterogeneous mutation in SOX3 and SEMA3A, and one of his elder sister was the carrier of a heterogeneous mutation in SEMA3A. Results of whole-exome sequencing of the proband (B).

This patient presented with GH deficiency, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (HH) due to GnRH deficiency, and borderline intellectual disability possibly caused by a novel frame-shift mutation of SOX3. HH is a common symptom in patients with SOX3 mutation for the defect of the anterior pituitary gland, but very few subjects developed this symptom due to GnRH deficiency. A heterogeneous missense mutation in SEMA3A was identified in this patient as well, which may also contribute to the development of HH. Besides, as far as we know, this case indicates for the first time that a frame-shift mutation of SOX3 constitutes rare genetic causes of HH and GH deficiency. We believe that our case extends the phenotypic spectrum and genetic variability of SOX3 mutation. As far as we know, no subjects have been reported to carry mutations in SOX3 and SEMA3A at the same time before. Whether mutations in these two genes act synergistically in the pathogenesis of his phenotype remains to be further investigated. It also reminds pediatricians that SOX3 mutation constitutes a rare cause of growth restriction and puberty delay.

The clinical phenotype varies dramatically in patients with SOX3 mutations. Studies even indicated interfamilial phenotypic variability with identical mutation (5). GH deficiency was reported to be the commonest pituitary hormone deficiency seen in patients with SOX3 mutation, and very few patients may be unaffected (6). Intellectual disability has been reported in most cases with SOX3 mutation, although the extent of the disability varies a lot (6). Besides being involved in the hypothalamus–pituitary axis formation, SOX3 is expressed throughout the central nervous system development and is involved in processes like pluripotency maintenance in self-renewing stem cells, lineage progression, and terminal differentiation (7). This may explain the coexistence of hypopituitarism and intellectual disability in patients with SOX3 mutations. Some subjects may have early onset of hypoglycemia and hypothyroidism. If not treated timely and properly, this may also contribute to intellectual disability.

Semaphorin (SEMA) has an important role in nerve development. Mutations in SEMA and its receptors were found to affect the migration of GnRH neurons, which may lead to idiopathic HH (IHH) (8). Mutation of SEMA3A in this case was previously identified in a subject with Kallmann syndrome, and cells harboring this gene mutation had impaired signaling activity of the secreted protein semaphoring-3A (9). This suggests that the point mutation of SEMA3A has a pathogenic effect, which may explain the coexistence of IHH in this subject. However, studies also suggest that monoallelic mutations in SEMA3A may not be sufficient to cause the disease phenotype, since these missense mutations were also reported in the Exome Variant Server database and found in healthy control individuals (9, 10). The mutation of SEMA3A was also found in the NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project database, with minor allele frequency of 0.01%. Consistent with this finding, his mother and elder sister who harbored the same mutation are phenotypically normal. Therefore, we think that the SOX3 mutation in this patient is highly likely to be causative for his phenotypes. Various studies have found that many subjects carrying SEMA3A variants also harbor other gene variants, such as KAL1, PROKR2, PROK2, and FGFR1 (11). This suggests that SEMA3A may act synergistically with other genes in the pathogenesis of IHH. By far, no subjects have been reported to carry mutations in SOX3 and SEMA3A at the same time before. Whether mutations in these two genes act synergistically in the pathogenesis of the phenotype in this case remains to be further investigated.

Gonadotropin deficiency was presumed to be common as well supported by small genitalia in many patients, yet the hypothalamus–pituitary–testis axis was not fully evaluated since most patients reported had not reached the age of pubertal development. Patients with SOX3 mutation may only present with delayed pubertal development as one patient with hemizygous in-frame deletion of polyalanine tract in SOX3 was found to have isolated GnRH deficiency (12). Although this patient had short stature and hypoplastic anterior pituitary by MRI, endocrine evaluation showed grossly normal pituitary function except for HH (13). For patients with combined pituitary deficiency including HH, we may presume that HH was due to defects in the anterior pituitary gland, namely, patients should have no response to the GnRH stimulating test. However, the patient with isolated HH and SOX3 mutation responded well by GnRH stimulating test (13), suggesting the defect of hypothalamus. Consistently, our case also suggests that the delayed pubertal development was due to GnRH deficiency, even in the presence of growth hormone deficiency. This may be explained by an animal study that defects possibly existed in the hypothalamus as well as pituitary in SOX3 null mice; therefore, hypopituitarism in patients with SOX3 mutation may be due to defects in both pituitary and hypothalamus (4). Clinicians may easily assume that delayed pubertal development is due to defects in the pituitary in patients with combined pituitary hormone deficiency and SOX3 mutation. This case reminds us of the importance to perform the GnRH stimulating test in this clinical scenario, and treatment strategies can be different in patients with defects in pituitary and hypothalamus.

For patients with clinical symptoms due to SOX3 mutation, the most common genetic alterations reported by far were duplications and deletions of SOX3 (3, 14). Therefore, the correct gene dosage of SOX3 was believed to be critical for the normal development of hypothalamo-pituitary axis and intellectual ability (15). Polyalanine tract expansion and deletions of SOX3, which belongs to intragenic mutations, were also common. Yet point mutation, another kind of intragenic mutation of SOX3, was rarely reported. As far as we know, only three point mutations and one polymorphism, including 7 subjects, were reported by far (15–18). All of them belong to missense mutation, and this is the first report of a SOX3 frame-shift mutation. Features of the 7 subjects as well as the subject reported in this case are summarized in Table 3. All the subjects were male. Like patients with other kinds of SOX3 mutation, the most common phenotype was GH deficiency. Six patients had combined pituitary deficiency, and most subjects had confirmed intellectual disability or learning difficulties. At least 6 of them had other dysmorphic disorders, such as ophthalmological abnormalities and dental anomalies. All 8 subjects had abnormal MRI findings, with anterior pituitary hypoplasia or absence being the most common abnormality.

In conclusion, we report a very rare SOX3 frame-shift mutation in a Chinese male patient with a growth hormone deficiency, HH due to GnRH deficiency, and borderline intellectual disability. Although no further study was conducted to examine this mutation on the function of SOX3, we conclude that this variant is likely the cause of the symptoms in this patient based on the current literature and the assumption that frame-shift mutation is highly pathogenic. A heterogeneous missense mutation in SEMA3A may also contribute to the development of HH. Whether mutations in these two genes act synergistically in the pathogenesis of the phenotype in this case remains to be further investigated. This case extends the phenotypic spectrum and genetic variability of SOX3 mutation. Moreover, it is essential to perform the GnRH stimulating test in patients with SOX3 mutation and HH.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

All the authors have contributed significantly. JL, YZ, and TG collected clinical data. YY helped with the interpretation of clinical data. JL wrote the manuscript. JwL revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The study was supported by the Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (Grant No. 2018HH0065 to JwL, and 2019YFS0302 to JL) and the 1.3.5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence-clinical Research Incubation Project, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Grant No. 2020HXFH034 to JwL).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We acknowledge Chigene for performing the whole-exome sequencing of the patient in this study.

1. Stevanovlć M, Lovell-Badge R, Collignon JM, Goodfellow PN. SOX3 is an X-Linked Gene Related to SRY. Hum Mol Genet (1993) 2(12):2013–18. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.12.2013

2. Collignon J, Sockanathan S, Hacker A, Cohen-Tannoudji M, Norris D, Rastan S, et al. A Comparison of the Properties of Sox-3 With Sry and Two Related Genes, Sox-1 and Sox-2. Development (1996) 122(2):509–20. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.2.509

3. Elizabeth MSM, Verkerk A, Hokken-Koelega ACS, Verlouw JAM, Argente J, Pfaeffle R, et al. Congenital Hypopituitarism in Two Brothers With a Duplication of the 'Acrogigantism Gene' GPR101: Clinical Findings and Review of the Literature. Pituitary (2021) 24(2):229–41. doi: 10.1007/s11102-020-01101-8

4. Rizzoti K, Brunelli S, Carmignac D, Thomas PQ, Robinson IC, Lovell-Badge R. SOX3 is Required During the Formation of the Hypothalamo-Pituitary Axis. Nat Genet (2004) 36(3):247–55. doi: 10.1038/ng1309

5. Burkitt Wright EMM, Perveen R, Clayton PE, Hall CM, Costa T, Procter AM, et al. X-Linked Isolated Growth Hormone Deficiency: Expanding the Phenotypic Spectrum of SOX3 Polyalanine Tract Expansions. Clin Dysmorphol (2009) 18(4):218–21. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0b013e32832d06f0

6. Arya VB, Chawla G, Nambisan AKR, Muhi-Iddin N, Vamvakiti E, Ajzensztejn M, et al. Xq27.1 Duplication Encompassing SOX3: Variable Phenotype and Smallest Duplication Associated With Hypopituitarism to Date - A Large Case Series of Unrelated Patients and a Literature Review. Horm Res Paediatr (2019) 92(6):382–89. doi: 10.1159/000503784

7. Salemi M, Romano C, Ragusa L, Di Vita G, Salluzzo R, Oteri I, et al. A New 6-Bp SOX-3 Polyalanine Tract Deletion Does Not Segregate With Mental Retardation. Genet Test (2007) 11(2):124–27. doi: 10.1089/gte.2006.0510

8. Cariboni A, Hickok J, Rakic S, Andrews W, Maggi R, Tischkau S, et al. Neuropilins and Their Ligands are Important in the Migration of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Neurons. J Neurosci (2007) 27(9):2387–95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5075-06.2007

9. Hanchate NK, Giacobini P, Lhuillier P, Parkash J, Espy C, Fouveaut C, et al. SEMA3A, a Gene Involved in Axonal Pathfinding, Is Mutated in Patients With Kallmann Syndrome. PLoS Genet (2012) 8(8):e1002896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002896

10. Kansakoski J, Fagerholm R, Laitinen EM, Vaaralahti K, Hackman P, Pitteloud N, et al. Mutation Screening of SEMA3A and SEMA7A in Patients With Congenital Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism. Pediatr Res (2014) 75(5):641–4. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.23

11. Dai W, Li JD, Wang X, Zeng W, Jiang F, Zheng R. Discovery of a Novel Variant of SEMA3A in a Chinese Patient With Isolated Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism. Int J Endocrinol (2021) 2021:7752526. doi: 10.1155/2021/7752526

12. Kim JH, Seo GH, Kim G-H, Huh J, Hwang IT, Jang JH, et al. Targeted Gene Panel Sequencing for Molecular Diagnosis of Kallmann Syndrome and Normosmic Idiopathic Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes (2018) 127(08):538–44. doi: 10.1055/a-0681-6608

13. Izumi Y, Suzuki E, Kanzaki S, Yatsuga S, Kinjo S, Igarashi M, et al. Genome-Wide Copy Number Analysis and Systematic Mutation Screening in 58 Patients With Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism. Fertil Steril (2014) 102(4):1130–6.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.06.017

14. Alatzoglou KS, Azriyanti A, Rogers N, Ryan F, Curry N, Noakes C, et al. SOX3 Deletion in Mouse and Human Is Associated With Persistence of the Craniopharyngeal Canal. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2014) 99(12):E2702–E08. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1160

15. Alatzoglou KS, Kelberman D, Cowell CT, Palmer R, Arnhold IJ, Melo ME, et al. Increased Transactivation Associated With SOX3 Polyalanine Tract Deletion in a Patient With Hypopituitarism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2011) 96(4):E685–90. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1239

16. Jelsig AM, Diness BR, Kreiborg S, Main KM, Larsen VA, Hove H. A Complex Phenotype in a Family With a Pathogenic SOX3 Missense Variant. Eur J Med Genet (2018) 61(3):168–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2017.11.012

17. Woods KS, Cundall M, Turton J, Rizotti K, Mehta A, Palmer R, et al. Over- and Underdosage of SOX3 Is Associated With Infundibular Hypoplasia and Hypopituitarism. Am J Hum Genet (2005) 76(5):833–49. doi: 10.1086/430134

18. Yu T, Chang G, Cheng Q, Yao R, Li J, Yu Y. Increased Transactivation and Impaired Repression of Beta-Catenin-Mediated Transcription Associated With a Novel SOX3 Missense Mutation in an X-Linked Hypopituitarism Pedigree With Modest Growth Failure. Mol Cell Endocrinol (2018) 478:133–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2018.08.006

Keywords: SOX3, frame-shift mutation, growth hormone deficiency, hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism, intellectual disability

Citation: Li J, Zhong Y, Guo T, Yu Y and Li J (2022) Case Report: A Novel Point Mutation of SOX3 in a Subject With Growth Hormone Deficiency, Hypogonadotrophic Hypogonadism, and Borderline Intellectual Disability. Front. Endocrinol. 13:810375. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.810375

Received: 06 November 2021; Accepted: 17 January 2022;

Published: 28 February 2022.

Edited by:

Eli Hershkovitz, Soroka Medical Center, IsraelReviewed by:

Pamela L. Mellon, University of California, San Diego, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Li, Zhong, Guo, Yu and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jianwei Li, amVycnlsaTY3OEB5YWhvby5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.