- 1College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Medicine, Dayanand Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab, India

- 3UCL Division of Medicine, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 4Department of Medicine, Delhi Heart Institute and Multispeciality Hospital, Bathinda, Punjab, India

- 5Institute of Metabolism and Systems Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom

- 6Queen Elizabeth Hospital, University Hospitals Birmingham National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust, Birmingham, United Kingdom

Background: With the exponential increase in digital space of social media platforms, a new group called social media influencers are driving online content of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) which eventually influences behaviour and decision-making process. The objective of this study was to identify the top 100 social media (Twitter) influencers and organizations from across the globe who are advocating for PCOS. We further explored the origin and journey of these social media influencers.

Methods: We identified the top 100 PCOS influencers and organizations between July and August 2022 using three social network analysis tools- Cronycle, Symplur and SocioViz. These influencers were invited to a semi-structured interview to explore why they chose to become an influencer and the support they have to deliver their online content. Two independent authors coded the anonymised transcripts from these interviews and broad themes were identified by thematic inductive analysis.

Results: 95.0% of individual influencers and 80% of organisations are from high-income countries. Most influencers in our study agree that social media is an essential tool in the present day to raise awareness of PCOS. However, they reiterated social media also has significant disadvantages that require consideration and caution. Most influencers were driven by poor personal experience and worked voluntarily to reduce misinformation and improve the experiences of women diagnosed with PCOS in the future. Although there is an interest in working together, there is currently minimal collaborative work between influencers.

Conclusion: There is a global inequity of #PCOS influencers online. Establishing standards and support based on evidence may help develop more influencers, especially in low- and middle-income countries, so we can counter misinformation and provide locally acceptable guidance.

Introduction

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common hormonal disorders affecting women accounting for 0.43 million disability-adjusted life-years from 1.55 million incident PCOS cases (1, 2). Latest studies have shown PCOS is no longer a condition affecting only the reproductive age women but a lifelong condition with increased risk for diabetes liver disease, endometrial cancer, obstructive sleep apnoea and impact on emotional wellbeing (3).

Social media has emerged as one of the largest medium through which people share and receive information.(Tao, Yang, and Feng 2020) Its greatest impact was seen through the COVID-19 pandemic when the public opinion was swayed based on the information shared online.(Qorib et al., 2023) Therefore, it is important that credible information is shared, not only with the people of PCOS, but also with the general public to create a positive and caring global community that understands the social aspects of PCOS and does not stigmatize women suffering from this condition. With the exponential increase in digital space of social media platforms, a new group called social media influencers (SMIs) have emerged (4). With growing literature on how the influencers impact behaviour and decision-making process (5–7), it is crucial to identify PCOS influencers. While there is literature about trends in social media influencers in surgical specialities (8–10), similar studies in PCOS are not available. Therefore, we conducted this study to establish the demographics and experiences of the top PCOS influencers.

Materials and methods

We conducted this study from June to August 2022. The list of top 100 PCOS influencers and organizations was extracted from Cronycle (Right relevance API).(“Market Intelligence & Competitor Monitoring Software | Cronycle” n.d.) Cronycle uses a proprietary algorithm to generate a Twitter topic score for both people and organizations based on their engagement to determine the overall “influence” of a Twitter account within a topic of discussion. By leveraging machine learning, semantic analysis and natural language processing, Cronycle utilises graph partitioning techniques to determine a numerical score of “influence” based on connections (follower/following) to other influencers on a particular topic and secondarily by engagement (views, likes, retweets) which represents the authority of an influencer within the topical community (11). This also has been used in similar studies in other specialties like cardiology (12) and critical care medicine (13). Recently, some of the authors of this article have applied this methodology to study the global impact of stroke awareness month (14), deep vein thrombosis awareness month (15), hernia awareness Month (16) and world hypertension day (17). The alternative forms of the term “Polycystic Ovary syndrome” that were included in the search query on Cronycle were- polycystic ovary, sindrome de ovario poliquistico, pco-syndrom, hyperandrogenic anovulation, syndrome des ovaires polykystiques, polycystic ovarian syndrome, pos, stein-leventhal syndrome, síndrome dos ovários policísticos, pcos, polycystic ovary syndrome (japanese), syndrome delle ovaie policistiche, polycystic ovary disorder, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (chinese).

We contacted the top 100 Twitter PCOS influencers to take part in our structured interview sharing their experiences regarding PCOS. Their contact details were obtained from publicly accessible professional profiles and one follow-up email was sent to the non-respondents. To limit bias associated with a single tool, we also invited top influencers identified through Symplur (18)and Socioviz (19). These software have different approaches to identify the top influencers. SocioViz calculates the top Influencers based on the number of retweets and mentions received in the set timeframe. Based on the quality of the number of mentions received, Symplur uses machine learning to identify the top influencers. A mention’s quality is determined by its influence, its healthcare stakeholder status, and its overall influence in healthcare social media. It is done to minimize the manipulation of simplistic metrics, such as mentions, tweets, followers, etc.

Upon accepting our invitation, we invited the influencers for a 15-minute semi-structured interview at the time of their convenience. With their consent, the meeting was recorded with auto-transcript feature to have a written transcript of the conversation that was later used for thematic analysis. The interview questions are listed in Supplementary 1.

Influencers were requested to not turn on their camera, share any patient details, or any other information they were not comfortable sharing. The context of the questions was broadly shared with the interviewee beforehand in the invite email and the interviewee reserved the right to not answer any specific question throughout the interview. At the beginning of the interview, the interviewee was requested to consent to the usage of the interview data for our study. The transcripts of all conversations were saved anonymously without the name of the interviewee in a password-protected encrypted folder. The mode of personal interview was chosen over an online survey to have more individualized and specific answers as most of the questions were open-ended and thematic in nature. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Delhi Heart Institute and Multispeciality Hospital, Punjab, India.

The anonymised transcripts were coded by 2 independent authors by thematic inductive analysis using NVivo and broad themes were identified depending on the interview data. Codes generated were merged and grouped into subcategories. Furthermore, the demographics data of top influencers were studied based on their profession and country of residence.

Results

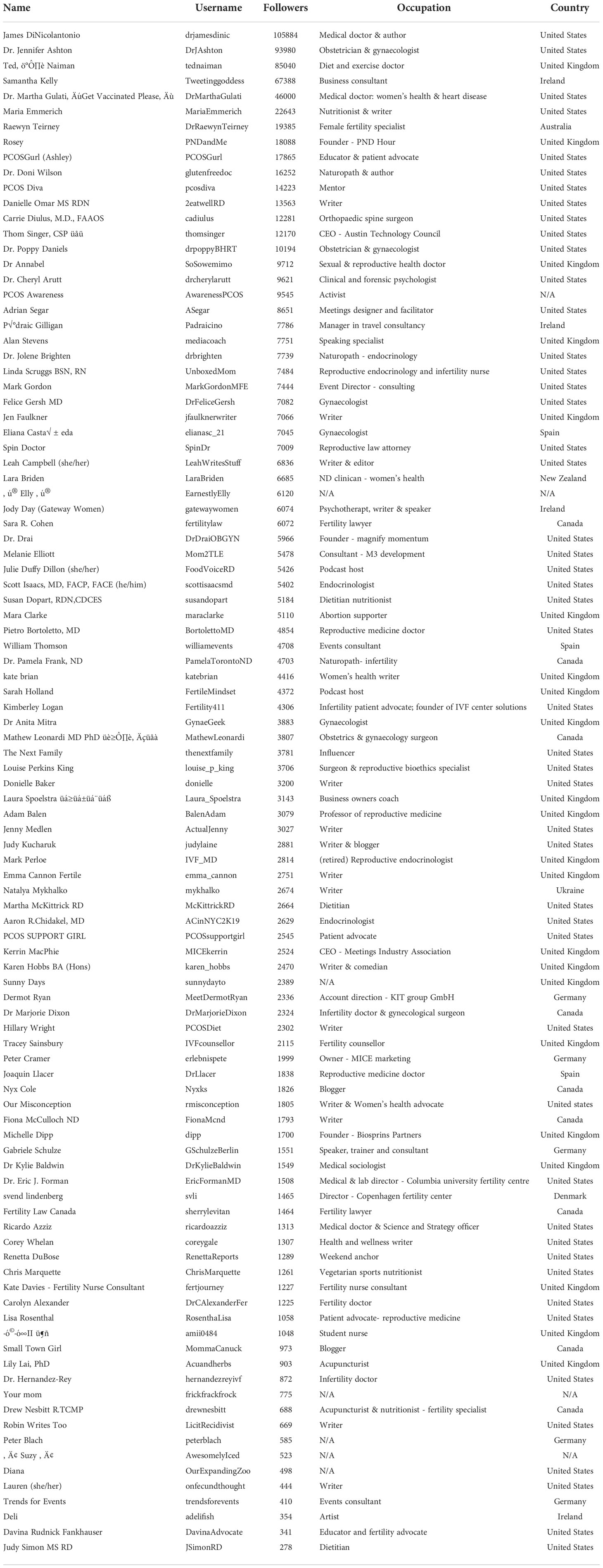

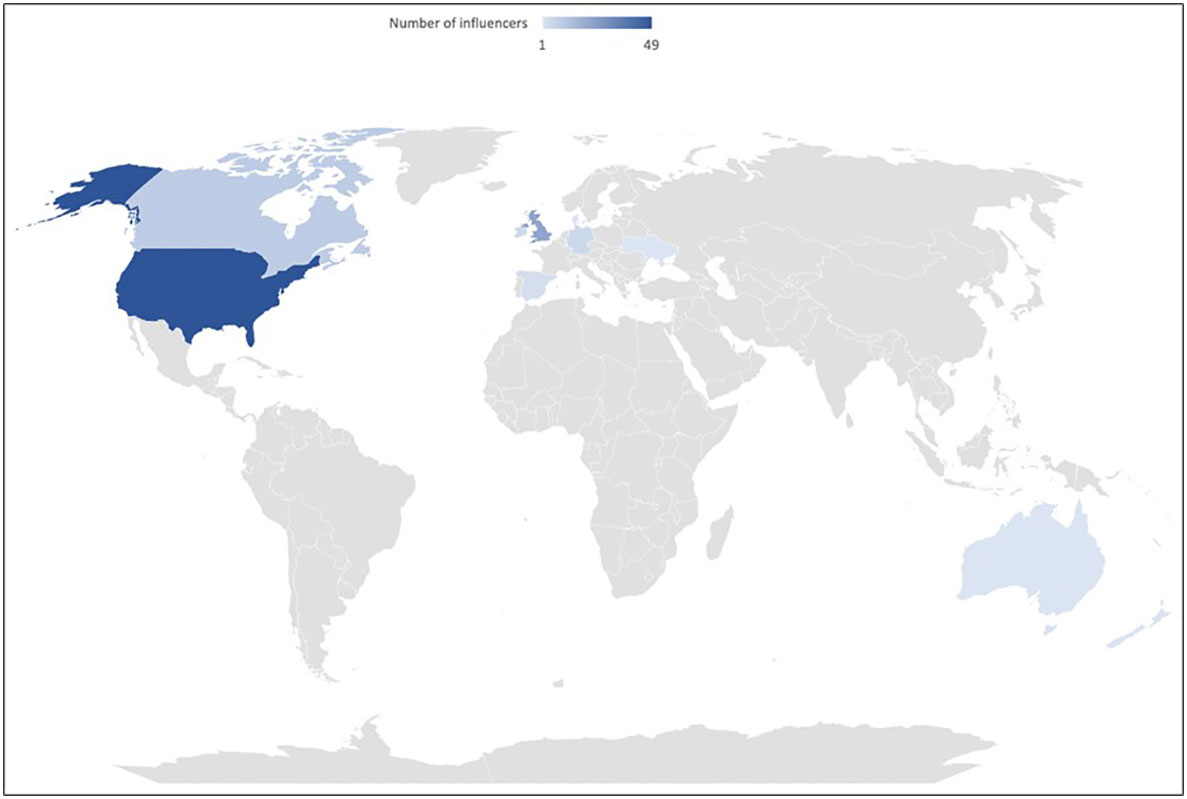

The top 100 individual and organisation influencers for #PCOS is listed in Tables 1, 2 respectively. Of the top 100 individual influencers, 73.2% (71) were female and 26.8% (20) male; 3 individuals’ gender was unknown. 95% of influencers were identified to be from high income countries. One influencer was from low- and middle-income country (LMIC). We could not identify the country of residence for four influencers (Figure 1) (21). Furthermore, the top 3 countries of residence were the USA (n=49), UK (n=22) and Canada (n=9).

Figure 1 Geographic spread of top 100 influencers for PCOS. The world map is for diagrammatic representation only and doesn't purport to be the political map of any country.

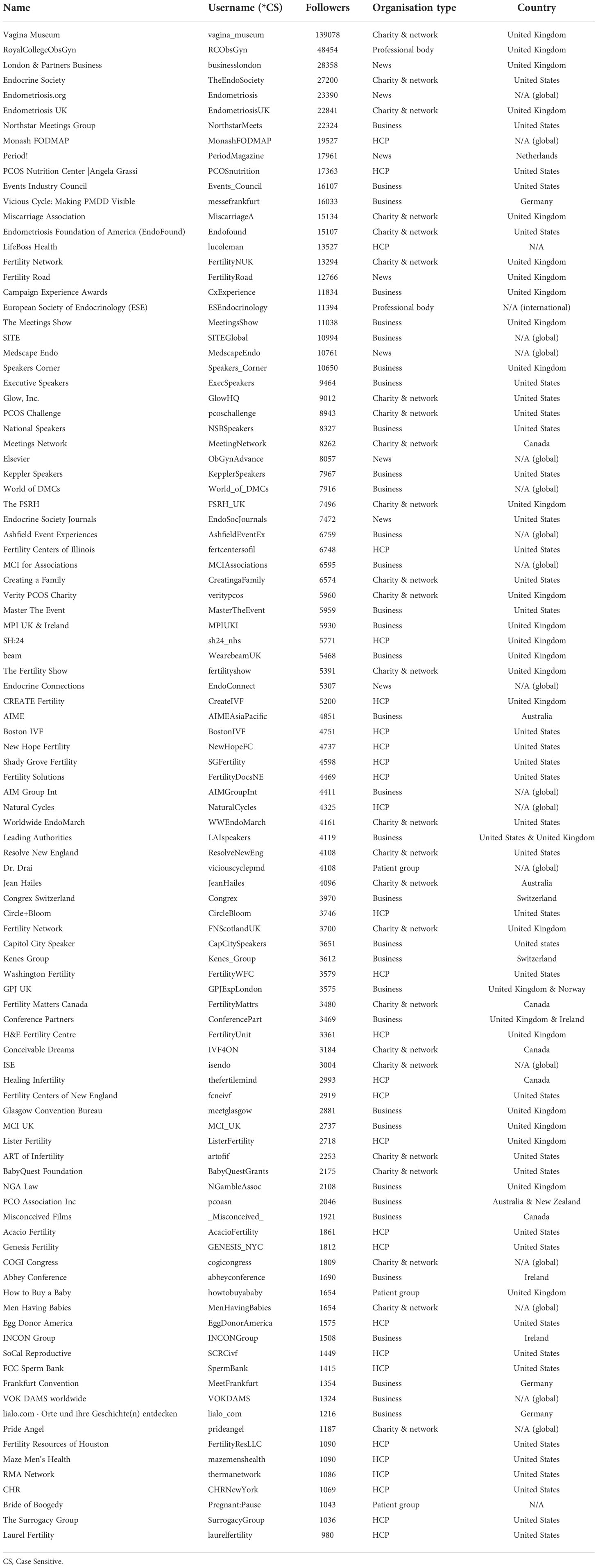

Amongst top 100 organisations, 80 worked in HICs and 18 worked internationally. None of the top organisation influencers (excluding two influencers from unknown locations) were from LMIC. The most prominent country of residence was the USA (38 organisations) followed by the UK (27 organisations). The organisations were classified as the following: Charities & Networks (n=25), patient support groups (n=3), Professional Bodies (n=2), News (n=8), Business (n=34) and Healthcare practices/professionals (n=28).

Of the total 100 influencers invited for an interview, 18 responded- eight agreed to meet and were interviewed, five agreed to meet but were not interviewed (due to loss of contact after agreeing on a day and time), five declined the invite (three were involved with nonmedical topics that are also abbreviated as PCOS. two explained that while they are may be linked to PCOS, their expertise in the field is limited).

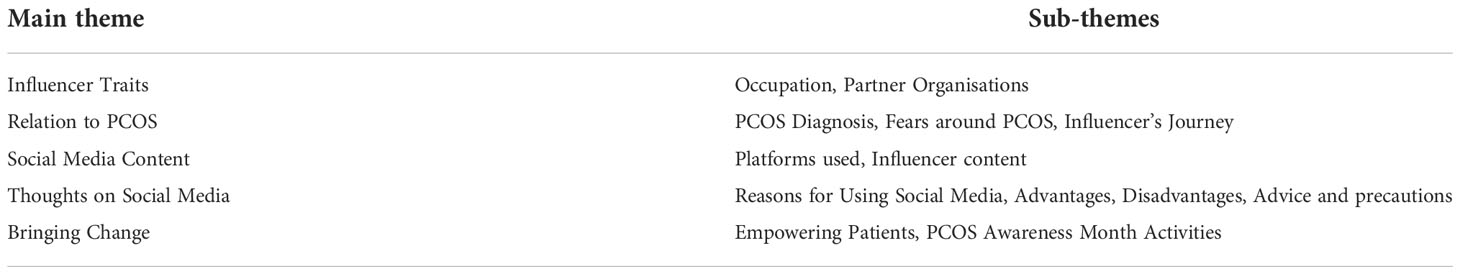

Out of the top 100 PCOS influencers contacted, a total of 8 influencers completed the interview. The 5 major themes that emerged from the analysis were: “Influencer Traits’’, “Relation to PCOS”, “Social Media Content”, “Thoughts on Social Media”, and “Bringing Change”. The sub-themes of each of these are summarised in Table 3.

Influencer traits

Of the 8 participants, five were based in England and three participants were based in the USA; five were health care professionals. Healthcare professionals were either researchers (2/5) or doctors (1 internal medicine and 2 metabolic endocrinology). The 3 other non-healthcare professionals had backgrounds in the fields of: psychology, management, and chemistry. Five Participants also demonstrated activity in other fields of endocrinology that they mentioned can be linked to PCOS. Amongst these fields, the most common ones were: “Obesity” (n=4), “Wellbeing” (n=4), and “Infertility” (n=3).

Relation to PCOS

Different motivational and influential factors contributed to the participants decision to get involved with PCOS awareness. “Spread of misinformation” (n=7), “lack of support and correct information” available for women diagnosed with PCOS (n=6), “Misconceptions of PCOS impacts on health” (n=5), and “misconceptions on the ability to make changes to better one’s lifestyle” (n=5) were the most common reasons participants shared why they decided to become influencers. Six participants explained the responsibility they felt to support women with a PCOS diagnosis and reduce the subsequent uncertainty they experienced.

Content

All participants reiterated the need to target a large proportion of the relevant audience by resorting to more than one social media platform. Five participants use twitter, three have a blog page, three use Instagram, and two rely on Facebook (some participants use more than one). Four participants created their own webpage. Other platforms that were mentioned include: TikTok (n=1), WhatsApp group (n=1) and clubhouse (n=1). Content that the influencers included focused on wellbeing (n=6), Lifestyle advice (n=4), recommended diets and nutrition (n=3), and influencer’s experiences in different aspects in relation to PCOS (n=3). Five participants explained that their content was personal to what they thought was relevant in their personal journey. Moreover, most participants highlighted the importance of “ensuring the information they publish is correct and accurate” (n=6).

We further studied the topics our eight interviewees mentioned they post on social media. There were 25 references on this topic. The 3 most common themes representing topics posted by the influencers were: Support groups (7 references), research and signposting (5 references), wellbeing and advice (4 references) and influencer journey (4 references). Other content includes: dietary advice and tackling myths/misunderstandings.

Thoughts on social media

Half of the participants expressed that social media allowed easy and fast dissemination of information (4/8). Six participants explained that the main reason they use social media is to ensure they publish evidence-based information after expressing their concern over the large prevalence of incorrect information and conception. Two participants shared that they use social media as they find it easy to contact and collaborate with other organisations and influencers. Four participants used social media to support and advise women with PCOS facing challenges with their diagnosis. They referred to it as an attempt to create a “support network” and a “common platform” that women with PCOS can relate to and resort to. While all participants shared the perspective that social media decreased feelings of alienation and increased support, they were equally concerned about the misinformation and the need to combat it. All participants also disclosed that criticism and hate is a concern they have around using social media. Six participants had personally experienced criticism on social media.

Bringing change

The main goal for all our participants was their desire to bring a change and empower women diagnosed with PCOS. Several suggestions were discussed in the interviews: to group all PCOS resources in one space so that it is easier for the target audience to access it (n=5), the importance of encouraging women with PCOS to make their own choices and lifestyle changes (n=5). Participants shared their plans for PCOS awareness month which included frequent blogs, lighting up a significant building in the city they are based in teal colour to increase PCOS awareness. All participants were open to collaborate and open to sharing resources on their platforms.

Discussion

Our study, first of its kind, shows that #PCOS influencers is limited by geographical and ethnical diversity. Although other researchers investigated the use of social media to relay medical information about PCOS, we are the first to study the influencer or content-generators’ experience of using social media. We also show for the first time there are a variety of medical and non-medical organisations who influence the PCOS content online. This is important to collaborate and ensure evidence-based content is shared to minimise misinformation.

Most influencers in our study agree that social media is an important tool in the present day to raise awareness of PCOS. However, they reiterated social media also has significant disadvantages that require consideration and caution. Influencers highlighted the lack of support in their personal journey which may translate to the limited support available to PCOS patients as well as, stigma and fears that may be linked to receiving such a diagnosis in different age groups and demographics.

Our data shows the current social media landscape is mostly influenced by HICs and this may drive the content viewed and accessed by globally. Several researchers have established the racial and ethnic variation in the prevalence and severity of PCOS phenotypes (22, 23). There is also increasing evidence on the impact of PCOS on emotional wellbeing. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to draw inference that needs of people with PCOS vary across regions and ethnicity. Hence there is a need to encourage and empower influencers across the world to meet local demands.

In the current day and age, it is almost inevitable that social media and information conveyed through it carries a large weight and can reach a large range of audience (24). This gives content-creators large power in terms of their ability to influence social media users and their respective audience. However, there are no standards or regulations to create educational or influencing content currently. There is no reliable data available regarding the influencers and social media content creators in LMICs. Some organisations provide general guidance How to find reliable health information online (25, 26). Some have attempted to standardise the medical and scientific information available online (20). However, the huge number of new websites launched each year and expenses involved in validation has limited both the standardisation organisation and the influencers to achieve such a status.

A study by Saroja and Chandrashekar identified 15 websites in 2010 which provided information on PCOS. However, none of them met all the standard criteria for quality set by the authors (27). A study by Sanchez et al. exploring how online teen and women’s magazines portray women with PCOS showed articles depicted PCOS symptoms as a hindrance to women’s social roles as wives and mothers and largely placed personal responsibility on women to improve their health (28). Interestingly, experiences of Latina and African American women and adolescents with PCOS were also absent from these women’s magazine articles. These findings highlight the urgent need for establishing guidance, support and regulations to positively influence PCOS and limit misinformation on social media.

The main strengths of this study are the use of three independent software to identify top social media influencers and the open-ended discussion with the influencers enabling a wider range of input from participants. However, a low response rate for invitations might decrease the generalisation of the results. Nevertheless, many of the identified concepts were reiterated by multiple participants suggesting the need to improve the existing support for women diagnosed with PCOS. While we identified the topics posted by our influencers as described by them in the interviews, future work focussing on the actual social media content can help identify common topics that are being posted and discussed by influencers.

Conclusion

There is a global inequity of #PCOS influencers online. Most influencers were driven by poor personal experience and work voluntarily to reduce misinformation and improve the experiences of women diagnosed with PCOS in the future. Although there is an interest to work together, there is currently minimal collaborative work between influencers. Establishing standards and support based on evidence may help develop more influencers, especially in the LMICs, so we can counter the misinformation and provide locally acceptable guidance.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Delhi Heart Institute and Multispeciality Hospital, Punjab, India. Written informed consent was not provided because Consent was obtained during the interview and recorded electronically and on video.

Author contributions

ME and KM conducted the searches and screened the data from three social network analysis tools. ME and KM have been involved in all stages of the study, contributed equally to this work, and share the first authorship. MS identified the occupation and country of residence for the top 100 influencers and organisation type and country of location for the top 100 organisations for #PCOS. KG was involved during conceptualisation, finetuning the research methods and obtaining ethics approval. KM and PK conceptualised and supervised all stages of the study. PK and ME critically analysed the codes from interviews to arrive at appropriate themes for results. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgments

We thank the member of PCOS Seva team for their inputs to finetuning the research question and methods.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2022.1084047/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Liu J, Wu Q, Hao Y, Jiao M, Wang X, Jiang S, et al. Measuring the global disease burden of polycystic ovary syndrome in 194 countries: Global burden of disease study 2017. Hum Reprod (2021) 36(4):1108–19. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa371

2. Joham AE, Norman RJ, Stener-Victorin E, Legro RS, Franks S, Moran LJ, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol (2022) 10(9):668–80. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00163-2

3. Kempegowda P, Melson E, Manolopoulos KN, Arlt W, O’Reilly MW. Implicating androgen excess in propagating metabolic disease in polycystic ovary syndrome. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab (2020) 11:2042018820934319. doi: 10.1177/2042018820934319

4. Freberg K, Graham K, McGaughey K, Freberg LA. Who are the social media influencers? a study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relat Rev (2011) 37(1):90–2. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.11.001

5. Pilgrim K, Bohnet-Joschko S. Selling health and happiness how influencers communicate on instagram about dieting and exercise: Mixed methods research. BMC Public Health (2019) 19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7387-8

6. Heiss R, Rudolph L. Patients as health influencers: motivations and consequences of following cancer patients on instagram. Behav Information Technol (2022). doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2022.2045358

7. Willis E, Delbaere M. Patient influencers: The next frontier in direct-to-Consumer pharmaceutical marketing. J Med Internet Res (2022) 24(3):e29422. doi: 10.2196/29422

8. Chandawarkar AA, Gould DJ, Stevens WG. The top 100 social media influencers in plastic surgery on twitter: Who should you be following? Aesthet Surg J (2018) 38(8):913–7. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjy024

9. Varady NH, Chandawarkar AA, Kernkamp WA, Gans I. Who should you be following? the top 100 social media influencers in orthopaedic surgery. World J Orthop (2019) 10(9):327. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v10.i9.327

10. Riccio I, Dumont AS, Wang A. The top 100 social media influencers in neurosurgery on twitter. Interdiscip Neurosurg (2022) 29:101545. doi: 10.1016/j.inat.2022.101545

11. Topics and influencer communities . Available at: https://www.cronycle.com/cronycle-right-relevance-influencers-topical-scores-rankings/.

12. Kesiena O, Onyeaka HK, Fugar S, Okoh AK, Volgman AS. The top 100 twitter influencers in cardiology. AIMS Public Health (2021) 8(4):743. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2021058

13. Munoz-Acuna R, Leibowitz A, Hayes M, Bose S. Analysis of top influencers in critical care medicine “twitterverse” in the COVID-19 era: a descriptive study. Crit Care (2021) 25(1):1–4. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03691-6

14. Goyal K, Nafri A, Marwah M, Aramadaka S, Aggarwal P, Malhotra S, et al. Evaluating the global impact of stroke awareness month: A serial cross-sectional analysis. Cureus (2022) 14(9):e28997. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28997

15. Malhotra K, Bawa A, Goyal K, Wander GS. Global impact of deep vein thrombosis awareness month: challenges and future recommendations. Eur Heart J (2022) 43(36):3379–81. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac252

16. Malhotra K, Bawa A. Prioritizing and promoting hernia awareness month: A call for action. World J Surg (2022) 46(7):1691–2. doi: 10.1007/s00268-022-06553-6

17. Malhotra K, Kalra A, Kumar A, Majmundar M, Wander GS, Bawa A. Understanding the digital impact of world hypertension day: key takeaways. Eur Heart J Digital Health (2022) 3(3):489–92. doi: 10.1093/ehjdh/ztac039

18. Symplur: Healthcare analytics products for social and real-world data . Available at: https://www.symplur.com/.

19. SocioViz is a free social network analysis tool for twitter. do you need a social media analytics software for social media marketing, digital journalism or social research? have a try and jump on board! . Available at: https://socioviz.net/home.

20. The PIF TICK | patient information forum . Available at: https://pifonline.org.uk/pif-tick/.

21. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. World bank data help desk . Available at: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519.

22. Bozdag G, Mumusoglu S, Zengin D, Karabulut E, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod (2016) 31(12):2841–55. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew218

23. Engmann L, Jin S, Sun F, Legro RS, Polotsky AJ, Hansen KR, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in the polycystic ovary syndrome metabolic phenotype. Am J Obstet Gynecol (2017) 216(5):493.e1–493.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.003

24. Chung A, Vieira D, Donley T, Tan N, Jean-Louis G, Gouley KK, et al. Adolescent peer influence on eating behaviors via social media: Scoping review. J Med Internet Res (2021) 23(6):e19697. doi: 10.2196/19697

25. How to find reliable health information online | patient . Available at: https://patient.info/news-and-features/how-to-find-reliable-health-information-online.

26. Evaluating Internet health information: A tutorial from the national library of medicine . Available at: https://medlineplus.gov/webeval/webeval.html.

27. Mallappa Saroja CS, Hanji Chandrashekar S. Polycystic ovaries: review of medical information on the internet for patients. Arch Gynecol Obstet (2010) 281(5):839–43. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1378-4

Keywords: polycystic ovary syndrome, PCOS, social media, influencers, high-income countries, low- and middle-income countries

Citation: Elhariry M, Malhotra K, Solomon M, Goyal K and Kempegowda P (2022) Top 100 #PCOS influencers: Understanding who, why and how online content for PCOS is influenced. Front. Endocrinol. 13:1084047. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.1084047

Received: 29 October 2022; Accepted: 23 November 2022;

Published: 07 December 2022.

Edited by:

Ali Abbara, Imperial College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Stanley Andrisse, Howard University, United StatesBassel Wattar, Epsom and St Helier University Hospitals NHS Trust, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Elhariry, Malhotra, Solomon, Goyal and Kempegowda. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Punith Kempegowda, UC5LZW1wZWdvd2RhQGJoYW0uYWMudWs=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Maiar Elhariry

Maiar Elhariry Kashish Malhotra

Kashish Malhotra Michelle Solomon

Michelle Solomon Kashish Goyal4

Kashish Goyal4 Punith Kempegowda

Punith Kempegowda