- 1Department of Endocrinology, University Hospital Gasthuisberg, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

- 2Medicine, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

- 3Department of Endocrinology, OLV ziekenhuis Aalst-Asse-Ninove, Aalst, Belgium

- 4Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, UZ Gasthuisberg, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

- 5Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, OLV ziekenhuis Aalst-Asse-Ninove, Aalst, Belgium

- 6Department of Endocrinology, Imelda ziekenhuis, Bonheiden, Belgium

- 7Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Imelda ziekenhuis, Bonheiden, Belgium

- 8Department of Endocrinology-Diabetology-Metabolism, Antwerp University Hospital, Edegem, Belgium

- 9Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Antwerp University Hospital, Edegem, Belgium

- 10Department of Endocrinology, Kliniek St-Jan Brussel, Brussel, Belgium

- 11Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Kliniek St-Jan Brussel, Brussel, Belgium

- 12Department of Endocrinology, AZ St Jan Brugge, Brugge, Belgium

- 13Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, AZ St Jan Brugge, Brugge, Belgium

- 14Center of Biostatics and Statistical bioinformatics, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Aims: To determine the preferred method of screening for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Methods: 1804 women from a prospective study (NCT02036619) received a glucose challenge test (GCT) and 75g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) between 24-28 weeks. Tolerance of screening tests and preference for screening strategy (two-step screening strategy with GCT compared to one-step screening strategy with OGTT) were evaluated by a self-designed questionnaire at the time of the GCT and OGTT.

Results: Compared to women who preferred one-step screening [26.2% (472)], women who preferred two-step screening [46.3% (834)] were less often from a minor ethnic background [6.0% (50) vs. 10.7% (50), p=0.003], had less often a previous history of GDM [7.3% (29) vs. 13.8% (32), p=0.008], were less often overweight or obese [respectively 23.1% (50) vs. 24.8% (116), p<0.001 and 7.9% (66) vs. 18.2% (85), p<0.001], were less insulin resistant in early pregnancy (HOMA-IR 8.9 (6.4-12.3) vs. 9.9 (7.2-14.2), p<0.001], and pregnancy outcomes were similar except for fewer labor inductions and emergency cesarean sections [respectively 26.6% (198) vs. 32.5% (137), p=0.031 and 8.2% (68) vs. 13.0% (61), p=0.005]. Women who preferred two-step screening had more often complaints of the OGTT compared to women who preferred one-step screening [50.4% (420) vs. 40.3% (190), p<0.001].

Conclusions: A two-step GDM screening involving a GCT and subsequent OGTT is the preferred GDM screening strategy. Women with a more adverse metabolic profile preferred one-step screening with OGTT while women preferring two-step screening had a better metabolic profile and more discomfort of the OGTT. The preference for the GDM screening method is in line with the recommended Flemish modified two-step screening method, in which women at higher risk for GDM are recommended a one-step screening strategy with an OGTT, while women without these risk factors, are offered a two-step screening strategy with GCT.

Clinical Trial Registration: NCT02036619 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02036619

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as diabetes diagnosed in the second or third trimester of pregnancy, given that overt diabetes early in pregnancy has been excluded (1). Adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as large-for-gestational age (LGA) infants, preeclampsia and cesarean sections, can be reduced by treatment of GDM between 24-28 weeks of pregnancy (2, 3). Women with a history of GDM have a seven-fold increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) compared to normal glucose tolerant women (NGT). These women also have a higher risk of developing a metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular events later in life compared to NGT women (4–7).

A universal one-step approach for GDM screening is recommended by the ‘International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups’ (IADPSG) with the 75g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) between 24-28 weeks of pregnancy (8). The World Health Organization (WHO) adopted these recommendations in 2013, whereby the IADPSG guidelines are now commonly referred to as the 2013 WHO criteria (9). However, using this one-step approach leads to an increased workload and possible unnecessary medicalization of care. Therefore, many European countries still use selective screening for GDM based on risk factors or recommend a two-step screening strategy with a glucose challenge test (GCT) (10). In addition, evidence is lacking that treatment of GDM based on the IADPSG screening strategy improves pregnancy outcomes compared to other screening strategies (11, 12). Moreover, a GCT is generally better tolerated than an OGTT and has the advantage that it can be performed in a non-fasting state (12). A modified two-step screening strategy with GCT combined with risk-factors was proposed based on the BEDIP-N study in Flanders. This allows women at higher risk for GDM (women with a history of GDM, obesity and/or impaired fasting glycaemia in early pregnancy) to receive a one-step screening strategy with an OGTT, while women without these risk factors, are offered a two-step screening strategy with GCT (13). However, data are lacking on which GDM screening method and which screening test pregnant women prefer. We aimed therefore to determine which GDM screening method (a two-step screening strategy with a GCT or a one-step screening approach with a 75g OGTT) participants preferred. In addition, we specifically aimed to determine the preference of GDM screening method according to the tolerance for the different screening tests and in relation to the population characteristics.

Subjects and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This article is a sub-analysis of the BEDIP-N cohort (NCT02036619). The BEDIP-N study was a multicentric prospective cohort study that has previously been described in detail (10, 14–17). The BEDIP-N study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating centers and all investigations have been carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2008. Before inclusion to the study, participants provided informed consent. Participants were enrolled between 6 and 14 weeks of pregnancy, when fasting plasma glucose (FPG) was measured. Women with impaired fasting glucose or diabetes in early pregnancy according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria, were excluded. Women without (pre)diabetes received universal screening for GDM between 24-28 weeks of pregnancy with both a non-fasting 50g GCT and a 75g 2-hour OGTT. Results of the GCT were blinded for participants and health care provides, so all participants received an OGTT irrespective of the GCT result. The diagnosis of GDM was based on the IADPSG/2013 WHO criteria (9, 14, 15). For treatment of GDM, the ADA-recommended glycemic targets were used (9). If targets were not reached within two weeks after the start of lifestyle measures, insulin was started. Women with GDM received an invitation for a postpartum 75g OGTT 6 to 16 weeks after delivery. The ADA criteria were used to define diabetes and glucose intolerance [impaired fasting glycemia (IFG) and/or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)] (9, 14).

Study Visits and Measurements

Baseline characteristics and obstetrical history were collected at first visit (14). At first visit and at the time of the OGTT, anthropometric measurements were obtained and several self-administered questionnaires were completed (14). The tolerance for the GCT and OGTT was evaluated by a self-designed questionnaire evaluating any discomfort or complaint with the test such as bad taste, nausea, vomiting, dizziness or abdominal pain. In addition, at the time of the OGTT the questionnaire also evaluated whether women considered it cumbersome to have to be fasting for the test, which screening test they would prefer (non-fasting GCT or the fasting OGTT) and whether they preferred a two-step screening strategy with GCT or a one-step screening approach with 75g OGTT. The CES-D questionnaire to evaluate symptoms of depression was completed at time of the OGTT (before the diagnosis of GDM was communicated), and at the postpartum OGTT for women with GDM (with a score ≥16 being suggestive for clinical depression (18). At first visit and at the time of the OGTT, a food questionnaire was used to question servings per week of different important food categories and beverages (19). Less healthy consumption was assigned 0 or -1 points. By summing up the points for all 14 food groups, the diet score could range from -12 to 15. At the time of the OGTT, the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) questionnaire (validated for the Belgian population) assessed physical activity (14, 20). Results of the IPAQ were reported in categories (low, moderate or high activity levels) as previously reported (21). In early postpartum, participants completed the SF-36 health survey (22)

Blood pressure (BP) was measured twice, with 5 minutes between each measurement using an automatic BP monitor. A BMI ≥ 25 kg/m² was defined as overweight, a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m² was defined as obese based on the BMI at first prenatal visit. During the first perinatal visit, a fasting blood test was taken to measure FPG, insulin, lipid profile (total cholesterol, HDL and LDL cholesterol, triglycerides) and HbA1c. The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) and beta-cell function (HOMA-B) was measured in early pregnancy (23). During the OGTT, glucose and insulin were measured fasting, at 30min, 60min and 120min. The results of glucose and insulin levels during the OGTT were used to calculate the Matsuda index, which is a measure of whole body insulin sensitivity (24). Furthermore, a fasting lipid profile, HbA1c and different indices of beta-cell function [HOMA-B, the insulinogenic index divided by HOMA-IR and the insulin secretion-sensitivity index-2 (ISSI-2)] were also measured at time of the OGTT (14, 23, 25–27).

Pregnancy and Delivery Outcome Data

The following pregnancy outcome data were collected: gestational age, preeclampsia (de novo BP ≥140/90mmHg > 20 weeks with proteinuria or signs of end-organ dysfunction), gestational hypertension (de novo BP ≥140/90mmHg > 20 weeks), type of labor and type of delivery, birth weight, macrosomia (>4 kg), birth weight ≥4.5 kg, LGA defined as birth weight >90 percentile according to standardized Flemish birth charts adjusted for sex of the baby and parity (28), small-for-gestational age (SGA) defined as birth weight <10 percentile according to standardized Flemish birth charts adjusted for sex of the baby and parity (28), preterm delivery (<37 completed weeks), 10min Apgar score, shoulder dystocia, neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, neonatal jaundice, congenital anomalies and admission on the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (14). Irrespective of the need for intravenous administration of glucose and admission on the NICU, a glycemic value <2.2mmol/l was considered as a neonatal hypoglycemia across all centers. Admission to the NICU was decided by the neonatologist in line with normal routine in each center. The difference in weight between first prenatal visit and the time of the OGTT was calculated as early weight gain. The total gestational weight gain was calculated as the difference in weight between first prenatal visit and the delivery. Excessive total gestational weight gain was defined according to the 2009 Institute of Medicine (IOM) guidelines (29).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile range for continuous variables. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test or the Fisher exact test in case of low (<5) cell frequencies, whereas continuous variables were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test for not normally distributed variables or One-way ANOVA test for normally distributed variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. Analyzes were performed by statistician A. Laenen by using SAS software.

Results

Preference for the GDM Screening Method

1803 women received both a GCT and an OGTT in the BEDIP-N study. Of all women, 46.3% (834) preferred two-step screening with a GCT, 26.2% (472) preferred a one-step screening strategy with an OGTT and 27.6% (497) had no clear preference. The most preferred screening test was a GCT, (by 54.8% (989) of all participants), while only 6.2% (112) preferred an OGTT and 39% (703) had no clear preference.

Tolerance of Screening Tests

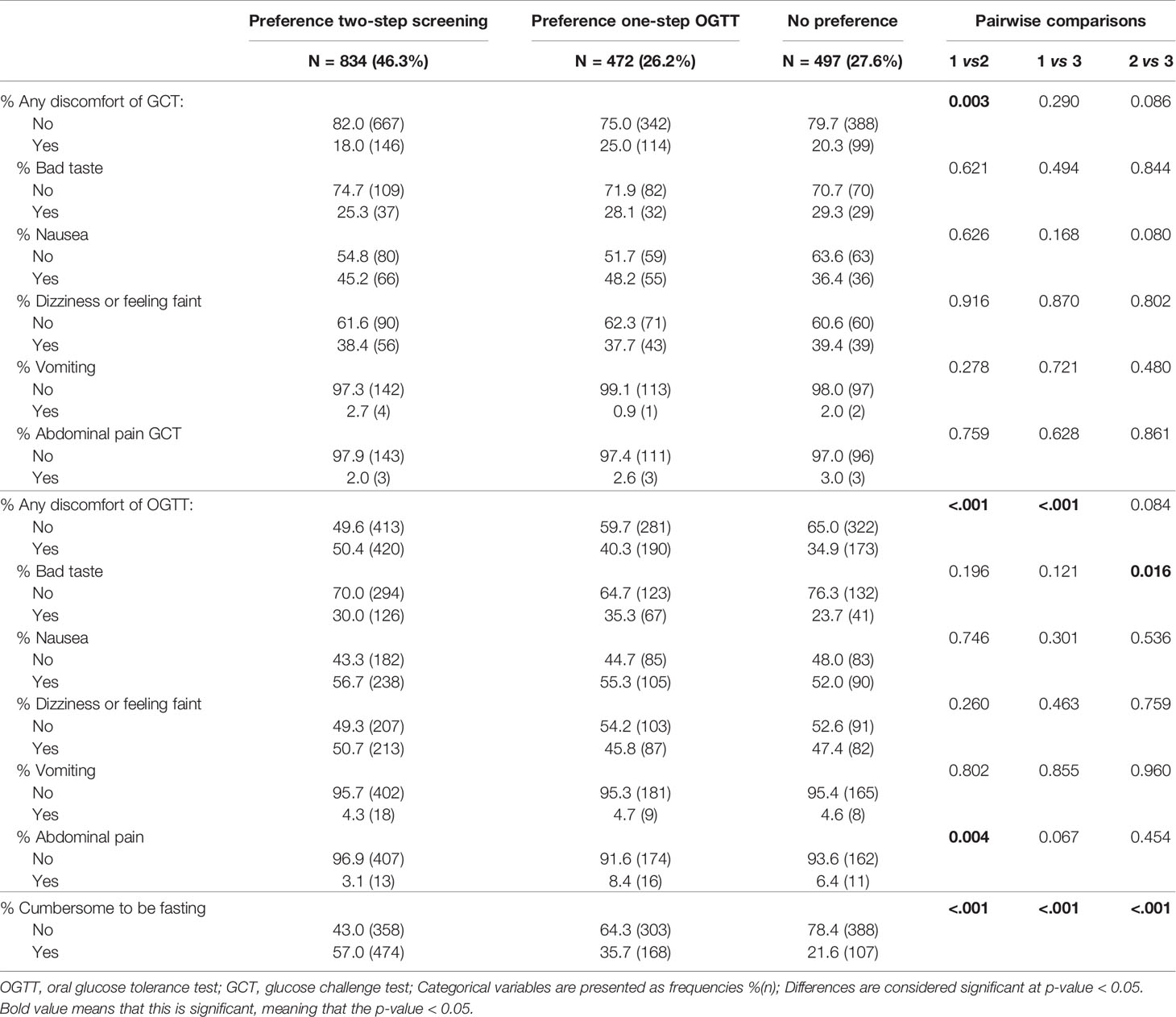

Women who preferred a two-step screening strategy tolerated the GCT in general significantly better than the OGTT compared to women who preferred a one-step screening approach and compared to women without clear preference (Table 1). In addition, women who preferred a two-step screening indicated that it was more cumbersome to be fasting for the OGTT compared to women who preferred a one-step screening strategy or had no clear preference and they reported more complaints of the OGTT (Table 1). The most common complaint during an OGTT was nausea (in each group more than half of all women reported nausea). There were no significant differences in the type of complaints for the OGTT between both groups, except that more women who preferred one-step screening reported abdominal pain compared to women who preferred two-step screening [8.4% (16) vs. 3.1% (13), p=0.004] (Table 1).

Table 1 Comparison of tolerance for screening tests between women who prefer two-step screening compared to women who prefer one-step screening with OGTT or without clear preference.

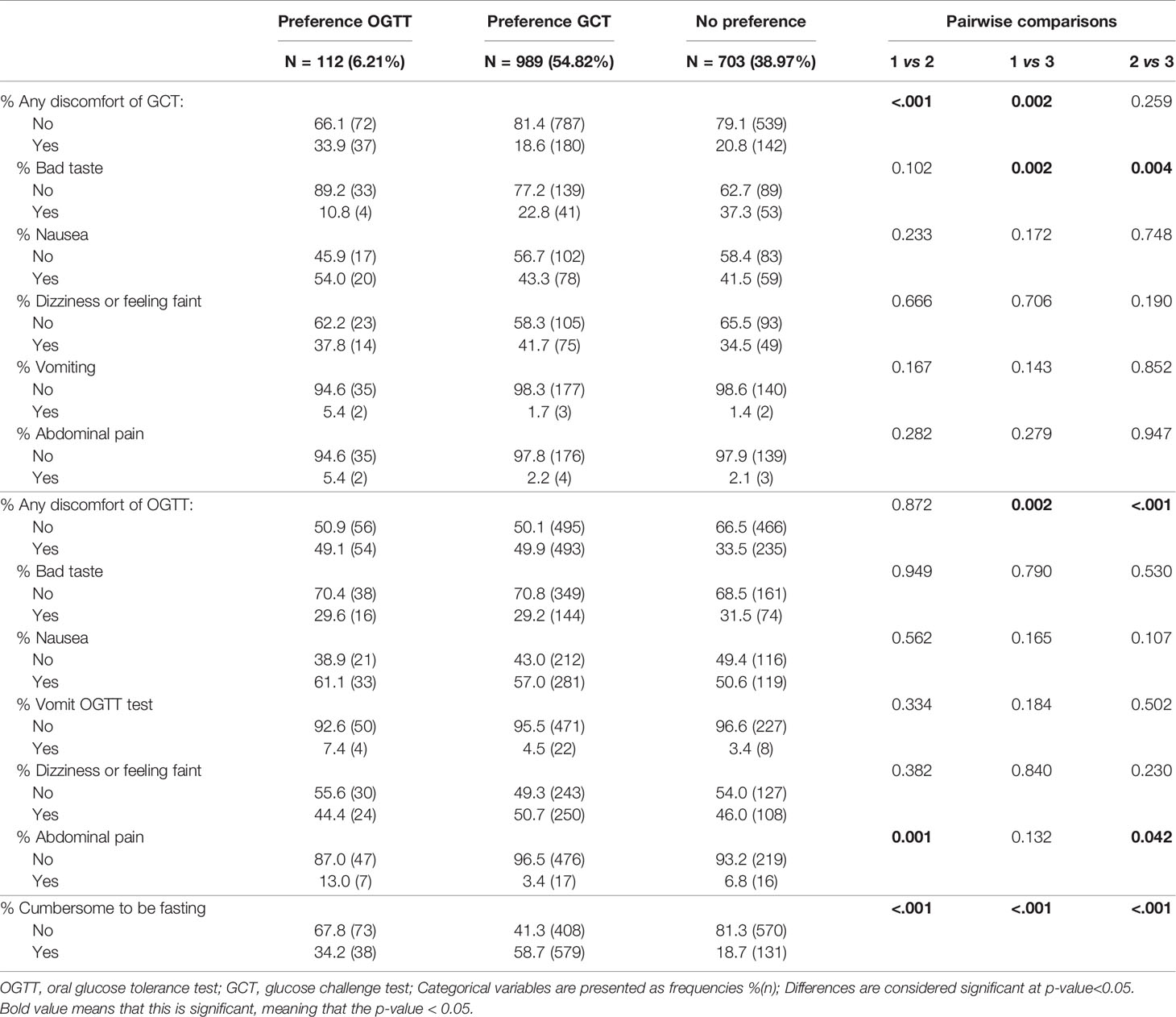

Women who preferred a GCT test had less complaints of the GCT compared to women with a preference for the OGTT [18.6% (180) vs. 33.9% (37), p<0.001]. Significantly more women who preferred a GCT found it cumbersome to be fasting for the OGTT compared to women who preferred an OGTT or had no clear preference [respectively 58.7% (579) vs. 34.2% (38), p<0.001 and 58.7% (579) vs. 18.7% (131), p<0.001] (Table 2).

Table 2 Comparison of tolerance for screening tests between women who prefer a GCT compared to women who prefer an OGTT or without clear preference.

Characteristics of Women According to the Preference of GDM Screening Method

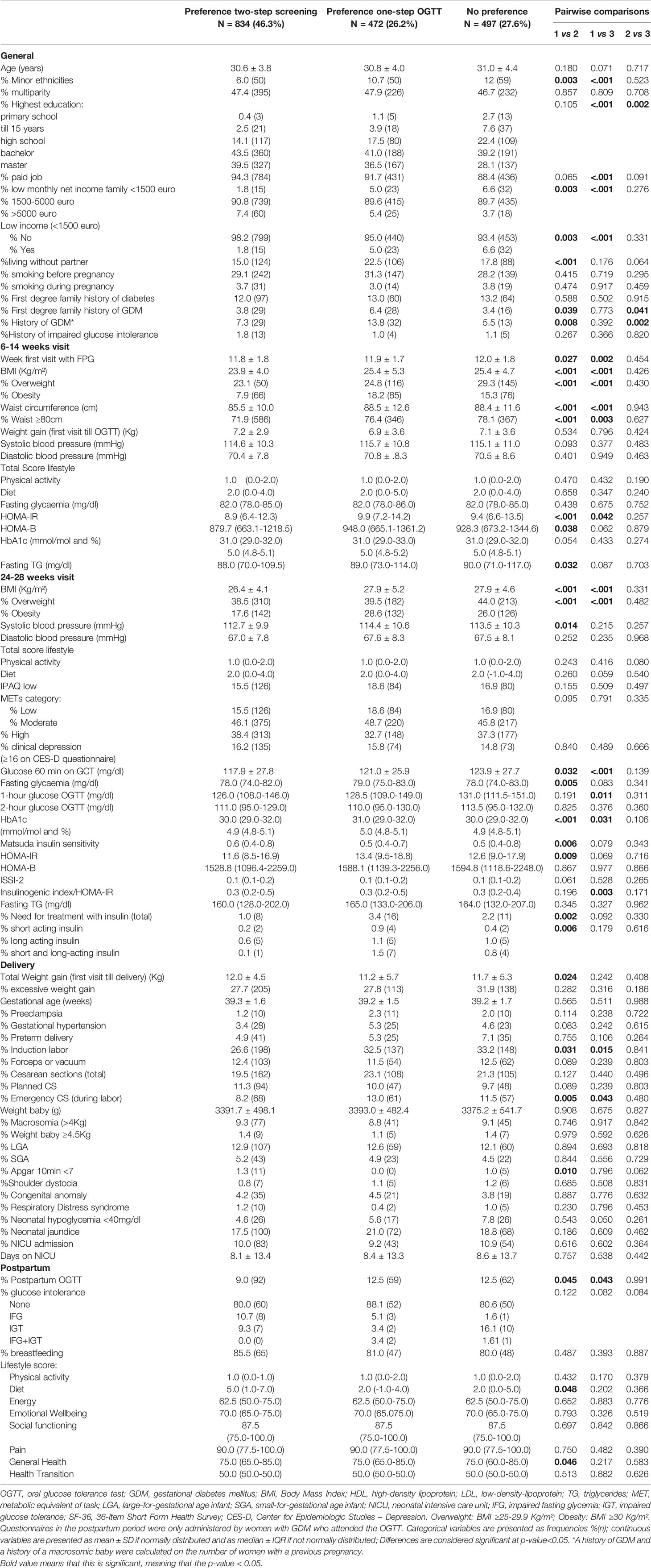

Compared to women who preferred one-step screening, women who preferred two-step screening, had less often a minor ethnic background, had less often a low income, had less often a first degree family history of GDM or a previous history of GDM [7.3% (29) vs. 13.8% (32), p=0.008], had a lower BMI [23.9 ± 4.0 vs. 25.4 ± 5.3, p<0.001), were less often overweight or obese [respectively 23.1% (50) vs. 24.8% (116), p<0.001 and 7.9% (66) vs. 18.2% (85), p<0.001], and were less insulin resistant in early pregnancy (HOMA-IR 8.9 (6.4-12.3) vs. 9.9 (7.2-14.2), p<0.001] (Table 3). There was no difference in the multiparity rate between both groups.

Table 3 Comparison of characteristics and pregnancy outcomes between women who prefer two-step screening compared to women who prefer one-step screening with OGTT or without clear preference.

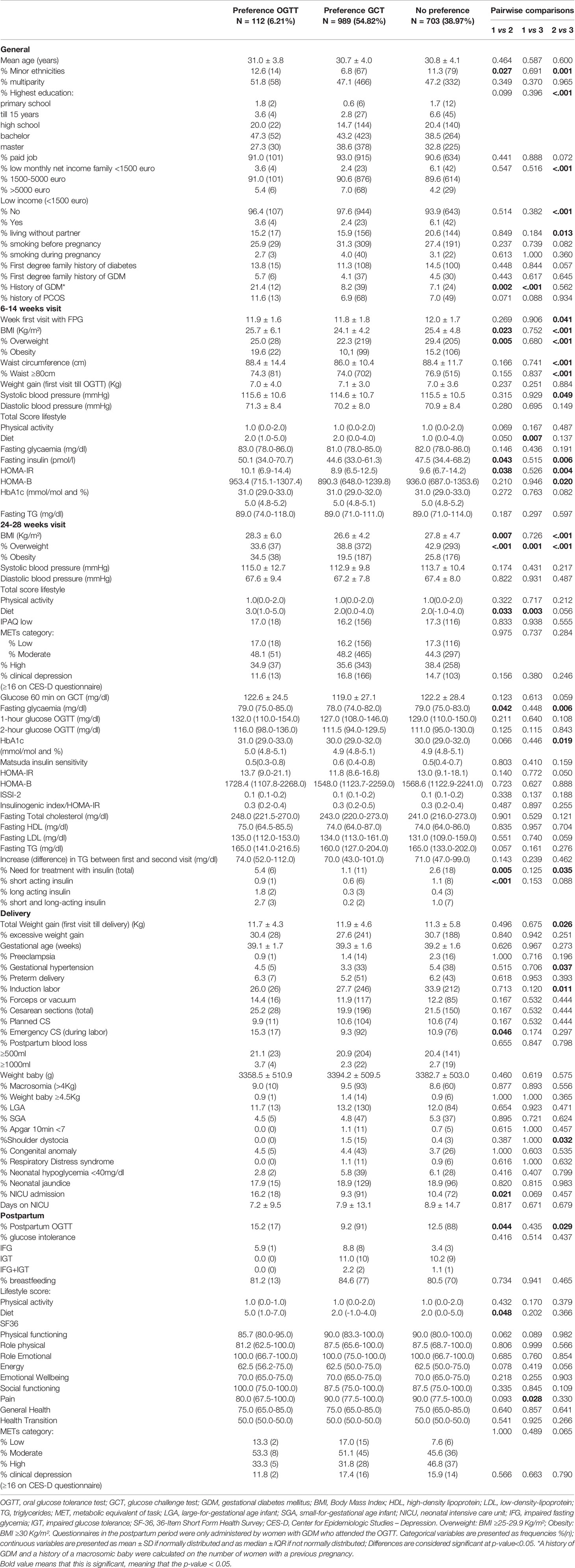

Characteristics of Women According to the Preference of Screening Test

Compared to women who preferred an OGTT, women who preferred a GCT had less often a minor ethnic background, had less often a previous history of GDM, had a lower BMI [24.1 ± 4.2 vs. 25.7 ± 6.1, p=0.023], and were less often overweight or obese [respectively 22.3% (219) vs. 25.0% (28), p=0.005 and 10.1% (99) vs. 19.6% (22), p=0.005]. At 24-28 weeks of pregnancy, significantly more women needed treatment with insulin for GDM in the group who preferred an OGTT compared to the group who preferred a GCT [5.4% (6) vs. 1.1% (11), p=0.005] (Table 4). There was no difference in the multiparity rate between both groups.

Table 4 Comparison of characteristics and pregnancy outcomes between women who prefer a GCT compared to women who prefer an OGTT or without clear preference.

Pregnancy Outcomes

Pregnancy outcomes were similar between women who preferred a one-step or two-step screening strategy, except for a lower rate of labor inductions and emergency cesarean sections (CS) in the group who preferred a two-step screening [respectively 26.6% (198) vs. 32.5% (137), p=0.031 and 8.2% (68) vs. 13.0% (61), p=0.005] (Table 3).

Women who preferred a GCT had less often emergency CS and less often neonatal jaundice [respectively: 9.3% (92) vs. 15.3% (92), p=0.046 and 9.3% (91) vs. 16.2% (18), p=0.021] compared to women who preferred an OGTT (Table 4).

Postpartum Outcomes

Women who preferred an OGTT had a better diet score postpartum compared to women who preferred a GCT. There was no difference in rate of glucose intolerance postpartum between the different groups (Tables 3, 4).

Discussion

We found that the majority of pregnant women preferred a two-step screening strategy with a GCT for GDM. In addition, we show that the preference of GDM screening method differed by metabolic risk profile of participants and tolerance for the screening tests. Women with a more adverse metabolic profile preferred a one-step screening approach with OGTT while women preferring a two-step screening strategy had a better metabolic profile and more discomfort of the OGTT.

Several international societies such as the IADPSG and WHO recommend a one-step screening approach for GDM with a 75g OGTT (8, 9). However, this leads to an important increase in the number of women diagnosed with GDM and important increase in workload. Moreover, this could also lead to increased medicalization of care with more labor inductions and CS. Evidence is lacking that treatment of GDM based on the one-step IADPSG screening approach improves pregnancy outcomes compared to other screening strategies. Recently, two large RCT’s from the US showed that a one-step screening strategy with the IADPSG criteria leads to a 2-3 fold increase in GDM prevalence compared to screening with a two-step approach with GCT but without improvement of pregnancy outcomes (11). In addition, the OGTT is often considered a cumbersome test during pregnancy. In our study, nearly half of all women indicated that it was difficult to come fasting. When choosing a GDM screening approach, it is therefore also important to take into account the preference of pregnant women for the GDM screening method and tolerance of the screening tests. To our knowledge, our cohort is the first study to systematically assess the preference of pregnant women for GDM screening method and tests. Our results show that nearly half of all women preferred a two-step screening strategy over a one-step screening approach with OGTT. Women who preferred a two-step screening strategy tolerated the GCT in general better than the OGTT compared to women who preferred a one-step screening approach or women without clear preference. More women preferred therefore a GCT as screening test. This is in line with other studies reporting difficulties with an OGTT in pregnancy, in which vomiting is often a reason for failure of the test (30). A recent RCT from the US showed that a 75g OGTT was better tolerated than a 100g OGTT for the diagnosis of GDM (11). However, when using a two-step screening strategy with GCT, a 100g OGTT is only needed in about 20% of all pregnant women. In line with normal clinical practice, adverse events of the screening tests would therefore occur in only 4% of women using a two-step screening strategy with GCT compared to 13% in women undergoing the one-step IADPSG approach with OGTT (11).

Women who preferred a GCT or two-step screening strategy had a better metabolic profile (were less often obese and less insulin resistant) and had less risk factors for GDM compared to women who preferred an OGTT or one-step screening approach. We have previously demonstrated that women with a higher risk-profile, such as women with a previous history of GDM and higher BMI have the highest risk to develop GDM and would therefore benefit from a one-step approach with OGTT (10). The Flemish consensus on screening for GDM was revised in 2019 based on the BEDIP-N study. A modified two-step screening strategy for GDM with GCT and also based on risk-factors, was proposed to limit the number of missed cases with GDM and at the same time avoid an OGTT in about 50% of all pregnant women (16). Based on this modified two-step screening strategy, women at higher risk for GDM (women with a history of GDM, obesity and/or impaired fasting glycaemia in early pregnancy), are recommended a one-step screening strategy with an OGTT, while women without these risk factors, are offered a two-step screening strategy with GCT (13). With current study we show now that this screening approach also fits with the preference of women for GDM screening method according to their metabolic risk profile and tolerance of the tests. In our study, the preference of GDM screening method was not different in women who had been pregnant before and had already experienced screening for GDM. However, most women with a previous history of GDM preferred a one-step screening strategy with OGTT. This is probably due to the fact that these women perceive themselves to be at high risk for a recurrent diagnosis of GDM and will therefore more often need an OGTT (irrespective of screening approach).

Pregnancy outcomes were in general similar irrespective of the preference of the GDM screening method, expect for lower rates of labor inductions and emergency CS in women who preferred a two-step screening strategy. This is probably due to the lower metabolic risk of women who preferred two-step screening. In addition, research has shown that a higher income and a higher education leads to less inductions and emergency CS (31, 32). There was no difference in the rate of glucose intolerance postpartum between both groups. Women who preferred an OGTT had a higher diet score, suggesting a healthier diet in early postpartum. This might be due to the fact that they perceive themselves at higher risk to develop diabetes postpartum.

Strengths of our study are the large prospective cohort with detailed data on clinical characteristics and obstetrical outcomes. In addition, women were blinded for the result of the GCT, so that they could not be biased by this result and their preference for a GCT or OGTT. Moreover, the tolerance and preference of GDM screening method was systematically recorded at the time of the GCT and OGTT. A limitation of the study is that the cohort consisted mostly of a Caucasian population with a rather low background risk for GDM. In addition, we did not perform extensive interviews to assess the tolerance of tests and reasons for the preference of GDM screening method.

In conclusion, our study showed that most women preferred a two-step screening strategy with GCT for GDM. In addition, we show that the preference of GDM screening method differed by metabolic risk profile of participants and tolerance of tests.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics committee of UZ Leuven, Leuven, Belgium. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

KB, PC, and CMa conceived the project. CMo prepared the data and ALa did the statistical analysis. LR did the literature review. LR and KB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the study design, including data collection, data interpretation and manuscript revision. The corresponding author LR had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the contents of the article and the decision to submit for publication. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This investigator-initiated study was funded by the Belgian National Lottery, the Fund of the Academic studies of UZ Leuven, and the Fund Yvonne and Jacques François-de Meurs of the King Boudewijn Foundation. The funders were not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

KB and RD are the recipient of a ‘Fundamenteel Klinisch Navorserschap FWO Vlaanderen’. We thank Dr. Inge Beckstedde from the UZA site and Dr. Sylva Van Imschoot from the AZ St Jan Brugge site for their help with the recruitment and study assessments. We thank the research assistants, paramedics and physicians of all participating centers for their support and we thank all women who participated in the study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2021.781384/full#supplementary-material

References

1. 14. Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care (2019) 42(Supplement 1):S165–72. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S014

2. Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, McPhee AJ, Jeffries WS, Robinson JS. Effect of Treatment of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus on Pregnancy Outcomes. New Engl J Med (2005) 352(24):2477–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042973

3. Landon MB, Spong CY, Thom E, Carpenter MW, Ramin SM, Casey B, et al. A Multicenter, Randomized Trial of Treatment for Mild Gestational Diabetes. N Engl J Med (2009) 361(14):1339–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902430

4. Song C, Lyu Y, Li C, Liu P, Li J, Ma RC, et al. Long-Term Risk of Diabetes in Women at Varying Durations After Gestational Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis With More Than 2 Million Women. Obes Rev (2018) 19(3):421–9. doi: 10.1111/obr.12645

5. Xu Y, Shen S, Sun L, Yang H, Jin B, Cao X. Metabolic Syndrome Risk After Gestational Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS One (2014) 9(1):e87863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087863

6. Kramer CK, Campbell S, Retnakaran R. Gestational Diabetes and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetologia (2019) 62(6):905–14. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4840-2

7. Benhalima K, Lens K, Bosteels J, Chantal M. The Risk for Glucose Intolerance After Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Since the Introduction of the IADPSG Criteria: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med (2019) 8(9):1431. doi: 10.3390/jcm8091431

8. International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups. Recommendations on the Diagnosis and Classification of Hyperglycemia in Pregnancy. Diabetes Care (2010) 33(3):676–82. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1848

9. Diagnostic Criteria and Classification of Hyperglycaemia First Detected in Pregnancy: A World Health Organization Guideline. Diabetes Res Clin Pract (2014) 103(3):341–63. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.10.012

10. Benhalima K, Van Crombrugge P, Moysonl C, Verhaeghe J, Vandeginste S, Verlaenen H, et al. Estimating the Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Based on the 2013 WHO Criteria: A Prediction Model Based on Clinical and Biochemical Variables in Early Pregnancy. Acta Diabetol (2020) 57(6):661–71. doi: 10.1007/s00592-019-01469-5

11. Davis EM, Abebe KZ, Simhan HN, Catalano P, Costacou T, Comer D, et al. Perinatal Outcomes of Two Screening Strategies for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet Gynecol (2021) 10:1097. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004431

12. Hillier TA, Pedula KL, Ogasawara KK, Vesco KK, Oshiro CES, Lubarsky SL, et al. A Pragmatic, Randomized Clinical Trial of Gestational Diabetes Screening. N Engl J Med (2021) 384(10):895–904. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2026028

13. Benhalima K, Minschart C, Van Crombrugge P, Calewaert P, Verhaeghe J, Vandamme S, et al. The 2019 Flemish Consensus on Screening for Overt Diabetes in Early Pregnancy and Screening for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Acta Clin Belg (2020) 75(5):340–7. doi: 10.1080/17843286.2019.1637389

14. Benhalima K, Van Crombrugge P, Verhaeghe J, Vandeginste S, Verlaenen H, Vercammen C, et al. The Belgian Diabetes in Pregnancy Study (BEDIP-N), A Multi-Centric Prospective Cohort Study on Screening for Diabetes in Pregnancy and Gestational Diabetes: Methodology and Design. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth (2014) 14(1):226–. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-226

15. Benhalima K, Van Crombrugge P, Moyson C, Verhaeghe J, Vandeginste S, Verlaenen H, et al. The Sensitivity and Specificity of the Glucose Challenge Test in a Universal Two-Step Screening Strategy for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Using the 2013 World Health Organization Criteria. Diabetes Care (2018) 41(7):e111–e2. doi: 10.2337/dc18-0556

16. Benhalima K, Van Crombrugge P, Moyson C, Verhaeghe J, Vandeginste S, Verlaenen H, et al. A Modified Two-Step Screening Strategy for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Based on the 2013 WHO Criteria by Combining the Glucose Challenge Test and Clinical Risk Factors. J Clin Med (2018) 7(10):351. doi: 10.3390/jcm7100351

17. Benhalima K, Van Crombrugge P, Moyson C, Verhaeghe J, Vandeginste S, Verlaenen H, et al. Characteristics and Pregnancy Outcomes Across Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Subtypes Based on Insulin Resistance. Diabetologia (2019) 62(11):2118–28. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4961-7

18. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl Psychol Meas (1977) 1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306

19. Durán A, Martín P, Runkle I, PÉRez N, Abad R, FernÁNdez M, et al. Benefits of Self-Monitoring Blood Glucose in the Management of New-Onset Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: The St Carlos Study, A Prospective Randomized Clinic-Based Interventional Study With Parallel Groups. J Diabetes (2010) 2(3):203–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-0407.2010.00081.x

20. Harrison CL, Thompson RG, Teede HJ, Lombard CB. Measuring Physical Activity During Pregnancy. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act (2011) 8(1):19–. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-19

21. Minschart C, De Weerdt K, Elegeert A, Van Crombrugge P, Moyson C, Verhaeghe J, et al. Antenatal Depression and Risk of Gestational Diabetes, Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes and Postpartum Quality of Life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2021) 106(8):e3110–24. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab156

22. Petrou S, Morrell J, Spiby H. Assessing the Empirical Validity of Alternative Multi-Attribute Utility Measures in the Maternity Context. Health Qual Life Outcomes (2009) 7(1):40–. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-40

23. Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis Model Assessment: Insulin Resistance and Beta-Cell Function From Fasting Plasma Glucose and Insulin Concentrations in Man. Diabetologia (1985) 28(7):412–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883

24. Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin Sensitivity Indices Obtained From Oral Glucose Tolerance Testing: Comparison With the Euglycemic Insulin Clamp. Diabetes Care (1999) 22(9):1462–70. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462

25. Kahn SE. The Relative Contributions of Insulin Resistance and Beta-Cell Dysfunction to the Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetologia (2003) 46(1):3–19. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-1009-0

26. Kirwan JP, Huston-Presley L, Kalhan SC, Catalano PM. Clinically Useful Estimates of Insulin Sensitivity During Pregnancy: Validation Studies in Women With Normal Glucose Tolerance and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care (2001) 24(9):1602–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.9.1602

27. Retnakaran R, Qi Y, Goran MI, Hamilton JK. Evaluation of Proposed Oral Disposition Index Measures in Relation to the Actual Disposition Index. Diabetic Med J Br Diabetic Assoc (2009) 26(12):1198–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02841.x

28. Bekaert A, Devlieger H, Eeckels R, Martens G. Standaarden Van Geboortegewicht-Voor-Zwangerschapsduur Voor De Vlaamse Boreling. Tijdschr Geneeskd (2000) 56(1):1–4. doi: 10.2143/TVG.56.1.5000625

29. Institute of M, National Research Council Committee to Reexamine IOMPWG. The National Academies Collection: Reports Funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, editors. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington (DC: National Academies Press (US) Copyright © 2009, National Academy of Sciences (2009).

30. Agarwal MM, Punnose J, Dhatt GS. Gestational Diabetes: Problems Associated With the Oral Glucose Tolerance Test. Diabetes Res Clin Pract (2004) 63(1):73–4. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2003.08.005

31. Claeys C, De Souter L, Martens G, Martens E, Blauleiser B, Faes E, et al. Ethnic Disparities and Morbidity in the Province of Antwerp, Belgium. Facts Views Vision ObGyn (2017) 9(4):189–93.

Keywords: gestational diabetes mellitus, preference for screening method, tolerance, glucose challenge test, two-step screening, one-step screening, oral glucose tolerance test

Citation: Raets L, Vandewinkel M, Van Crombrugge P, Moyson C, Verhaeghe J, Vandeginste S, Verlaenen H, Vercammen C, Maes T, Dufraimont E, Roggen N, De Block C, Jacquemyn Y, Mekahli F, De Clippel K, Van Den Bruel A, Loccufier A, Laenen A, Devlieger R, Mathieu C and Benhalima K (2021) Preference of Women for Gestational Diabetes Screening Method According to Tolerance of Tests and Population Characteristics. Front. Endocrinol. 12:781384. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.781384

Received: 22 September 2021; Accepted: 22 October 2021;

Published: 08 November 2021.

Edited by:

Rick Francis Thorne, The University of Newcastle, AustraliaCopyright © 2021 Raets, Vandewinkel, Van Crombrugge, Moyson, Verhaeghe, Vandeginste, Verlaenen, Vercammen, Maes, Dufraimont, Roggen, De Block, Jacquemyn, Mekahli, De Clippel, Van Den Bruel, Loccufier, Laenen, Devlieger, Mathieu and Benhalima. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lore Raets, bG9yZS5yYWV0c0BrdWxldXZlbi5iZQ==

Lore Raets

Lore Raets Marie Vandewinkel2

Marie Vandewinkel2 Yves Jacquemyn

Yves Jacquemyn Annouschka Laenen

Annouschka Laenen Roland Devlieger

Roland Devlieger Chantal Mathieu

Chantal Mathieu