Abstract

Adipose tissue (AT) biology is linked to cardiovascular health since obesity is associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and positively correlated with excessive visceral fat accumulation. AT signaling to myocardial cells through soluble factors known as adipokines, cardiokines, branched-chain amino acids and small molecules like microRNAs, undoubtedly influence myocardial cells and AT function via the endocrine-paracrine mechanisms of action. Unfortunately, abnormal total and visceral adiposity can alter this harmonious signaling network, resulting in tissue hypoxia and monocyte/macrophage adipose infiltration occurring alongside expanded intra-abdominal and epicardial fat depots seen in the human obese phenotype. These processes promote an abnormal adipocyte proteomic reprogramming, whereby these cells become a source of abnormal signals, affecting vascular and myocardial tissues, leading to meta-inflammation, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, heart hypertrophy, heart failure and myocardial infarction. This review first discusses the pathophysiology and consequences of adipose tissue expansion, particularly their association with meta-inflammation and microbiota dysbiosis. We also explore the precise mechanisms involved in metabolic reprogramming in AT that represent plausible causative factors for CVD. Finally, we clarify how lifestyle changes could promote improvement in myocardiocyte function in the context of changes in AT proteomics and a better gut microbiome profile to develop effective, non-pharmacologic approaches to CVD.

1 Introduction

Obesity is a chronic and multifactorial metabolic disease described in most scientific literature as the epidemic of the 21st century. In fact, by 2016, this condition affected 650 million adults, equivalent to 13% of the adult population worldwide, while in 2019, 38.3 million children under the age of 5 were overweight or obese (1). In the United States, obesity accounts for approximately 21% of annual national health care costs ($190 billion) (2). In addition, this entity is frequently clustered to other comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome (MetS), insulin resistance (IR), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), gout, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) (3). CVD is the leading cause of death worldwide, with approximately 17.9 million deaths each year, of which 85% are attributable to myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke (4).

Research has centered on evaluating the causality of obesity in CVD in recent years, focusing on areas such as the potential role of adipose tissue (AT) on cardiac tissue (5, 6). AT is a highly functional and complex endocrine organ, characterized by the release of adipokines, batokines, microRNAs, prostaglandins, bioactive lipids and other regulators of metabolic homeostasis, which interact with vascular, hepatic, renal, digestive, cerebral, skeletal muscle and myocardial tissue through paracrine and endocrine mechanisms (5, 7–10).

One hallmark feature in obesity is the ectopic and visceral adipose tissue (VAT) accumulation leading to AT transcriptome and secretome modification due to adipocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia. This condition is related to tissue´s hypoxia and fibrosis, immune cell infiltration, stimulating the release of pro-inflammatory, pro-atherogenic and anti-angiogenic substances that affect AT biology and communication with other target tissues (11). In addition, myocardial cells are also affected by signaling molecules from the dysfunctional or “sick” AT (SickAT), given their link with heart hypertrophy and fibrosis, atrial fibrillation (AF), MI, among other CVD (12–15).

These data highlight the importance of establishing therapeutic tools to help combat obesity and, by extension, CVD. In a nutshell, obesity etiology is derived from an energy imbalance produced in the context of an obesogenic lifestyle (16) characterized by a hypercaloric diet and insufficient physical activity (PA) to counteract the SickAT expansion and subsequent defective signaling processes (10, 17, 18). Hence, PA and nutritional interventions (NI) might improve the SickAT profile and, consequently, enhance adipose tissue and myocardiocyte crosstalk. Therefore, this review discusses both AT and SickAT distribution and biology and their relationship with myocardial tissue. We will also address the molecular mechanisms by which exercise, food supplementation, and changes in eating habits can counteract obesity, taking as a pivotal point the role of the gut microbiota (GM) in SickAT pathogenesis to establish the non-pharmacological treatment of CVD.

2 The Sick Adipose Tissue: From Distribution to Interaction

The AT is a dynamic and anatomically heterogeneous organ acting as connective tissue throughout our organism. Beyond its particular vasculature, innervation and predominant adipocyte content, its microenvironment includes numerous immune cells, endothelial and stromal cells, fibroblasts, preadipocytes, and abundant extracellular matrix (ECM) (19–21). Each component possesses characteristic properties and can secrete various hormones, growth factors, microRNAs (miRNAs), cytokines, and chemokines coordinated, with autocrine, endocrine, and paracrine action on neighboring and remote organs/or cells (12, 22, 23). AT can also be classified by anatomical location, embryonic origin, morphology or function, the latter which can be grouped into white (WAT), brown adipose tissue (BAT) (24).

WAT is responsible for storing energy as fatty acids (FA) within triacylglycerides (TAG), supplying energy and controlling metabolic homeostasis through the white adipocyte endocrine functions (25). The main fat deposit in mammals is widely distributed throughout the subcutaneous adipose tissue (SCAT), gonadal and inguinal adipose depots. Adipose tissue located in the abdominal cavity, including intrahepatic and mesenteric, omental, and retroperitoneal fat, can be considered VAT (18, 19). Other intrathoracic AT depots identified include epicardial adipose tissue (EAT), occupying the space between the pericardium and myocardium, with a direct relationship with the coronary arteries; pericardial (PAT), located between the visceral and parietal pericardium, and perivascular (PVAT), which surrounds the remaining blood vessels (22, 26). It should be noted that both VAT and cardiovascular system (CVS)-based depots are considered a risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases, an association that has been widely reported (11, 26).

Unlike WAT, BAT has adipocytes with smaller lipid droplets, more abundant mitochondria and substantial vascularization, which provide its characteristic brown color (27). Likewise, BAT has high levels of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), which confer thermogenic properties by uncoupling between respiration and ATP synthesis during the FA oxidation in adipocytes (28, 29); hence, UCP1 is recently considered as a potential therapeutic target against obesity (30). In humans, BAT is found in specific areas (supraclavicular fossa, interscapular and paravertebral regions, in the axilla and nape) and represents only 4.3% of the total fat mass (31, 32). Notably, another type of adipocyte has been characterized within WAT deposits, and it has shown mixed characteristics of both white and brown adipocytes. For that reason, this new type of adipocyte has been coined as beige adipose tissue (BeAT). As stated above, BeAT reside within the WAT and can be mainly found within the inguinal WAT (33). Also, BeAT express the UCP1 gene and, by extension, thermogenic properties (34). Note that this browning process occurs through exposure to cold, β-adrenergic stimulation and pharmacological modulation of WAT (35).

2.1 Changes in Adipose Tissue Microenvironment and Meta-Inflammation: The Sick Forgotten

According to the WHO, obesity is defined as excessive or abnormal fat accumulation with negative health repercussions, determined by a body mass index (BMI) ≥ of 30 kg/m2 (36). Although its etiology includes genetic, social, environmental and/or cultural factors, in most cases, it is characterized by an imbalance between energy intake and energy expenditure, attributed to poor eating habits and sedentary lifestyles (16). This hypercaloric or overnourished state leads to more significant fat accumulation in AT, mainly in the form of ectopic or visceral depots (37). AT can increase in abundance through two different processes: hypertrophy and hyperplasia or new adipocytes formation.

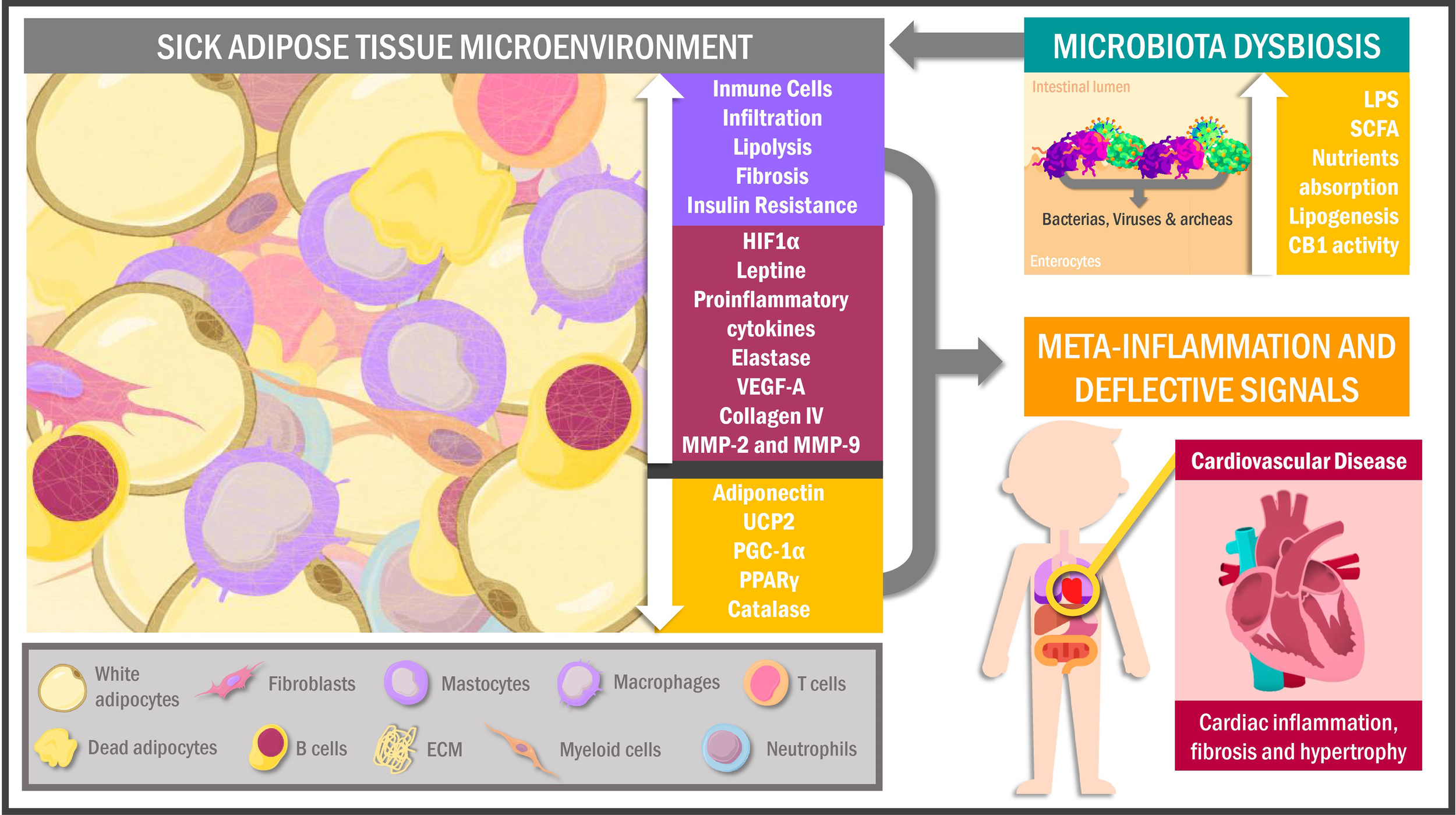

Hyperplasia is considered a beneficial and adaptive process by which new functional adipocytes can be formed from fibroblastic preadipocytes without altering their secretory profile and maintaining vascularization of the AT microenvironment (37, 38), which is associated with better metabolic health (39). A transcriptional cascade regulates this cell line differentiation carried out by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR γ) and CCAAT enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBP), in conjunction with pro-adipogenic factors such as bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) (40, 41). However, hypertrophy and subsequent adipocyte dysfunction disrupt these signaling processes and preserve the pro-inflammatory phenotype characteristic of obese individuals (Figure 1) (42, 43).

Figure 1

Sick adipose tissue microenvironment and its interactions. Hypertrophic adipocytes and immune cells infiltration characterize the adipose tissue of obese individuals in response to a hypoxic environment as a signal for cell death and inflammation. This phenomenon leads to proteomic dysregulation and deflective peripheral signals promoting metabolic alterations in other tissues like muscle cells, particularly the myocardiocytes. In addition, obesogenic habits in overweighed people cause changes in the intestinal microbiota triggering adipose tissue chronic inflammation and cellular senescence. UCP2, uncoupling protein 2; PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; VEGF-A, vascular endothelial growth factor A; MMP, metalloproteinases; HIF1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; SCFA, short-chain fatty acids; CB1, cannabinoid receptor 1; ECM, extracellular matrix.

The pre-existing adipocytes gain volume via increased fat accumulation, experiencing heightened mechanical stress by contact with adjacent cells and other extracellular matrix components (ECM) (44). Over time, AT expansion results in reduced regional blood flow, altered oxygen diffusion and finally tissue hypoxia, all of that related to both oxidative stress activation (OS) (45) and increased transcriptional activity of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α), nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB), and cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) genes, whose transcripts, in turn, drives to adipokines, chemokines, metalloproteases and growth factors gene expression, all of these related to a pro-inflammatory peptidic secretome (46). Concurrently, these hypoxia-induced factors downregulate anti-inflammatory and metabolism-regulatory adipokines such as adiponectin, which occurs alongside reduced transcription of antioxidant and thermoregulation-related genes, particularly catalase encoders UCP2, PPARγ and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) (47–49). Consequently, transcriptomic and proteomic changes in AT lead to a low-grade inflammatory environment characterized by functionally-altered fibroblasts, endothelial cells and immune cells niche (50, 51). Regarding the latter, macrophages have been identified as the predominant cells of this system in AT, showing a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype in obese individuals compared to the anti-inflammatory M2 in lean individuals (52). In this scenario, the hypoxic inflammatory state of AT promotes the release of interferon-γ (IF-γ) by T helper 1 (Th1) lymphocytes, inducing M1 macrophage recruitment and polarization, which causes increased release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), interleukin (IL) -6, IL-12, IL-1β and IL-23 (53–56).

Obese patients exhibit clusters of lipid-binding macrophages from dead adipocytes, a phenomenon well-correlated with AT inflammation and insulin resistance (57, 58). In addition, obesity promotes CD8 + and CD4 + T lymphocytes infiltration together with effector B-cells, heightening pro-inflammatory factors release and consequently AT dysfunction with defective extracellular signaling (59, 60). Similarly, myeloid cells, mast cells (50, 51) and neutrophils are also present in SickAT, showing that they contribute to tissue damage through elastase secretion and thus promote macrophage recruitment (61, 62).

Among the essential SickAT characteristics in obese patients are altered angiogenesis and endothelial dysfunction (ED). Although SickAT upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) and HIF1α expression (both linked to angiogenesis), production is insufficient to generate neovascularization and counteract hypoxia, inflammation and necrosis characteristic of obese patients (63–66). Furthermore, SickAT leads to reactivity in the endothelium of the surrounding vessels, inducing the synthesis of intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM-1), P-selectin and E-selectin, which in turn promotes macrophage infiltration worsening the pro-inflammatory milieu (67). Additionally, adipocyte-endothelial crosstalk can contribute to vasomotor alterations, deteriorating the oxygen bioavailability in EAT, PVAT and PAT (68, 69).

Likewise, HIF1α upregulation, immune cell infiltration and hyperactivity are associated with AT fibrosis. Remarkably, the increased synthesis of ECM components, mainly type-VI collagen and its cleavage products such as endotrophin, have been associated with metabolic dysfunction in obese mice via mechanical stress caused by limits on AT expansion (44, 70–72). Interestingly, HIF1α expression is correlated with metalloproteinases (MMP) -2 and MMP-9 in EAT, which are considered necessary for expansion and secretome alterations (69).

On a different plane, adipocyte metabolic activity is substantially modified in a hypoxic state. In fact, some glycolytic enzyme genes such as hexokinase 2 (HK2), phosphofructokinase (PFKP) and GLUT1 exhibit an increased expression in adipocyte cell cultures under hypoxic conditions (73, 74). Furthermore, although GLUT4 is the main isoform found in adipocytes, GLUT1 is the most efficient glucose transporter at low-oxygen levels (75). As expected in hypoxic states, the above changes suggest adipocytes have increased glucose uptake and metabolism (76), as confirmed by their increased lactate secretion (77).

In summary, lipid metabolism proteomics tends towards lipolytic extreme under hypoxic conditions (78). The SickAT microenvironment is characterized by multiple agents influencing insulin signaling, like IL-6, TNF-α, resistin, and IL-1β (79). Under normal conditions, insulin inhibits lipolysis through the mTORC1-Egr1-ATGL pathway, so inhibition of insulin´s second messengers cascade increases lipolytic activity (80). Furthermore, fatty acid uptake by adipocytes is blunted under hypoxic conditions (74), leading to plasma free fatty acids increase worsening insulin signaling (81) and contributing to the pro-inflammatory state (82). It should be highlighted that intrathoracic and visceral AT, BAT, BeAT and SCAT depots are affected in obesity (83), the thermogenic properties of BAT can be disturbed by mild inflammatory cells infiltration in severely obese individuals (84), leading to diminished glucose and FFA oxidative metabolism, and therefore contribute to IR and dyslipidemia development (84–86). In contrast, BeAT occurs less frequently owing to the dysfunctional state of WAT in obese patients (87).

2.2 Microbiota Dysbiosis

The gastrointestinal tract contains a complex population of microorganisms, the gut microbiota (GM), which exerts a marked influence on human health and disease (88). Multiple factors contribute to establishing the intestinal microbiota during early childhood and as it evolves into adulthood, but it is not hard to imagine that one of the main factors that shape the gut microbiota structure throughout our lives is our diet. In addition, gut bacteria play a crucial role in maintaining and proper function of the immune system and intermediary metabolism. Abnormalities in the intestinal bacterial composition (dysbiosis) have been associated with many inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune and metabolic diseases.

GM is constituted by bacteria, archaea, viruses and fungi, interacting symbiotically with the host (88). However, hypercaloric diet (HCD) and obesogenic habits alter the microbiota-host relationship, affecting its composition and interaction with the organism (89). A growing body of evidence in this area has centered on comparing energy and body fat storage in germ-free mice with transplanted microbiota of wild mice or obese individuals. The findings were that although the mice maintained the same diet in both cases, there was a substantial increase in adiposity and IR development after microbial transplantation, which could be attributed to the role of the microbiota in calorie extraction and absorption (90–92). Although the possible mechanisms triggered by HCD and obesity involved in the GM-AT axis interaction have not been fully elucidated yet, specific hypotheses have been proposed to explain these findings.

Significant among these theories is the influence of microbial products on AT. In physiological situations, the intestinal wall has selective permeability due to the tight junction proteins between enterocytes; however, an HCD can decrease expression of these proteins and allow passage of lipopolysaccharides (LPS), bacterial products of gram-negative bacteria (93–95). Once in circulation, LPS spread throughout the body and act on type 4 toll receptors (TLRs) located in AT adipocytes and immune cells (96), activating pathways dependent on myeloid differentiation factor 88- (MyD88-) and TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF). This process activates the nuclear translocation of NF-kB and the subsequent release of pro-inflammatory substances, contributing to the typic low-grade inflammation seen in SickAT (97, 98). Furthermore, it has been reported that LPS/TLR4 pathway activation can decrease WAT browning (99) and adaptive thermogenesis (100). Another interesting observation is that GD can increase permeability by activating the intestinal endocannabinoid system, acting on its CB1 receptors associated with obesogenic habits (101).

Likewise, several commensal bacteria species of the GM ferment indigestible carbohydrates and fiber to obtain energy by forming short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) (102–104), mainly acetate, butyrate and propionate. These metabolites have key roles in energy metabolism (105) and immunomodulation (106), by acting on the family of free fatty acid receptors (FFAR), especially FFAR2 (GPR43) and FFAR3 (GPR41), located in gastrointestinal, nervous, and AT tissue (107). Therefore, GD present in obese individuals may lead to changes in SCFA levels and, by extension, SickAT-related metabolic alterations. Higher SCFA production has been reported to promote lipogenesis by activating carbohydrate responsive element-binding protein (ChREBP) and sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1 (SREBP1), favoring weight gain in animals models (108, 109). Similarly, studies have shown that SCFAs can inhibit fasting-induced adipocyte factor (FIAF), which can suppress enzyme lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity and thus increase triacylglycerol (TAG) storage and accumulation in AT (90, 91).

Additionally, SCFAs stimulates peptide YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) secretion, which in turn slow down the intestinal transit time and thus increase nutrient absorption (109, 110), influencing appetite control (111). Other GT-AT axis-related mechanisms such as the TMA/FMO3/TMAO signaling pathway (112), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing 1 (NOD1) and NOD2 (113) proteins, and modulation of the miRNA-181 family (114) have also been explored in the context of obesity and its possible implications in the switch to SickAT. However, given the lack of a proven causal link between microorganisms, their products and specific mechanisms in humans, together with the heterogeneity of GT and the fact that Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes are predominant in both obese and healthy individuals (115), further research is warranted in this area.

3 Intercellular Signaling Between Adipocytes and Myocardial Cells

3.1 Adipokines

3.1.1 Leptin

Leptin is a peptidic hormone secreted by AT, so peripheral leptin levels tend to remain directly proportional to AT volume (116). Consistent with this finding, obese patients show elevated leptin levels, but signaling defects mean that appetite suppression is reduced or nullified (117). Thus, obesity-related hyperleptinemia has been suggested as an important factor in CVD genesis (118). From a molecular perspective, leptin plays a role in atherosclerosis initiation by the hyper-production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in endothelial cells (119). The explanation of this phenomenon relies on increased fatty acid oxidation via protein kinase A stimulation, which increases MCP-1 production, facilitating macrophage infiltration into the sub-endothelial (120). Furthermore, in vitro studies have shown that leptin increases cholesterol uptake in macrophages by ACAT1 modulation (121). These results match with clinical findings obtained in other studies; indeed, leptin levels are correlated with markers of atherosclerosis such as the intima-media thickness of the carotid artery (122) and likewise with the severity of coronary artery disease (CAD) (123).

It has also been hypothesized that leptin can induce cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (124). This effect seems mediated by multiple mechanisms, such as increased endothelin 1 (ET-1) and ROS production in cardiomyocytes in response to leptin levels (125). Another theory is that leptin activates the mTOR (126) and PPAR-α signaling pathways (127). Consistent with the above, clinical studies have shown a positive correlation between serum leptin levels and left ventricular thickness in obese or insulin-resistant patients (128). In contrast, another study conducted in a murine model proposes that leptin exhibits antihypertrophic properties. Based on these findings, mice with left ventricular hypertrophy reverted to normal ventricular function when normal leptin levels were restored (129).

Nonetheless, rather than a direct consequence of restored leptin levels, these findings may stem from reversing metabolic alterations inherent to leptin deficiency, so these results should be interpreted cautiously. On the other hand, the antihypertrophic properties associated with leptin levels have been reported in some studies (130–132). In conclusion, it remains uncertain whether cardiac hypertrophy is due to leptin pro-hypertrophic action or is instead an effect of resistance to leptin antihypertrophic action on cardiac remodeling.

3.1.2 Interleukin 6

As AT produces around a third of circulating IL-6, it can be considered an adipokine (133); however, its role in cardiomyocyte function is somewhat controversial. In acute phases, IL-6 signaling has been attributed a cardioprotective effect by inducing anti-apoptotic pathways and conferring protection against OS (134). However, IL-6 also decreases myocardial contractility and eventually increases nitric oxide (NO) production may be through inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) activation (135, 136). Likewise, a study in animals reported no significant effects of treatment with IL-6 on left ventricular remodeling (137), while another study found that IL-6 signaling blockade suppresses myocardial inflammation and ventricular remodeling (137). Since human and murine IL-6 show only 41% similarity, animal studies should be approached with caution. Regarding human studies, elevated IL-6 levels have been correlated with ventricular dysfunction (138), heart failure, arrhythmias and worse clinical outcomes (139), indicating a need for further study to clarify the role of IL-6 in CVD.

3.1.3 Adiponectin

Under SickAT conditions, adiponectin secretion is considerably reduced, impacting negatively on cardiovascular function (140). On the other hand, normal adiponectin levels have been shown to improve cardiomyocyte dysfunction in animal models, probably due to mechanisms related to IRS-1 and the c-Jun pathway (141). Furthermore, adiponectin is necessary to activate PPARγ signaling, which confers protection against myocardial hypertrophy and cardiac remodeling (142). Likewise, adiponectin inhibits iNOS and NADPH oxidase expression, decreasing OS under ischemic conditions (143). On a different level, adiponectin stimulates COX-2 expression and prostaglandin E2 synthesis, conferring cardioprotective and anti-inflammatory properties (144).

Clinically, hypoadiponectinemia is independently associated with ED (145), while normal adiponectin levels are associated with a lower risk of ischemic events in men (146). Conversely, low adiponectin levels positively correlate with left ventricular hypertrophy, regardless of age or other metabolic factors (147). However, a systematic review found no significant relationship between adiponectin levels and cardiovascular mortality, and a 10% increased risk of death from any cause was reported (148). This finding requires considering concurrent situations such as kidney failure and age-related adiponectin resistance, leading to bias when analyzing different populations (149, 150). Nonetheless, the prevailing view in the literature is that adiponectin confers cardioprotection at normal concentrations, while hypoadiponectinemia is related to an increased risk of developing ED as well as myocardial dysfunction.

3.2 BCAAs

Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), valine, leucine and isoleucine, are essential amino acids playing a critical energetic role in different tissues, including myocardial cells and adipocytes (151). For example, in physiological circumstances, adipocytes oxidize BCAAs as an important energy substrate; however, different stimuli or organic conditions such as insulin resistance, obesity or cardiovascular disease cause adipose cells reprogramming, reducing BCAA metabolism in the heart, AT and liver (152–154).

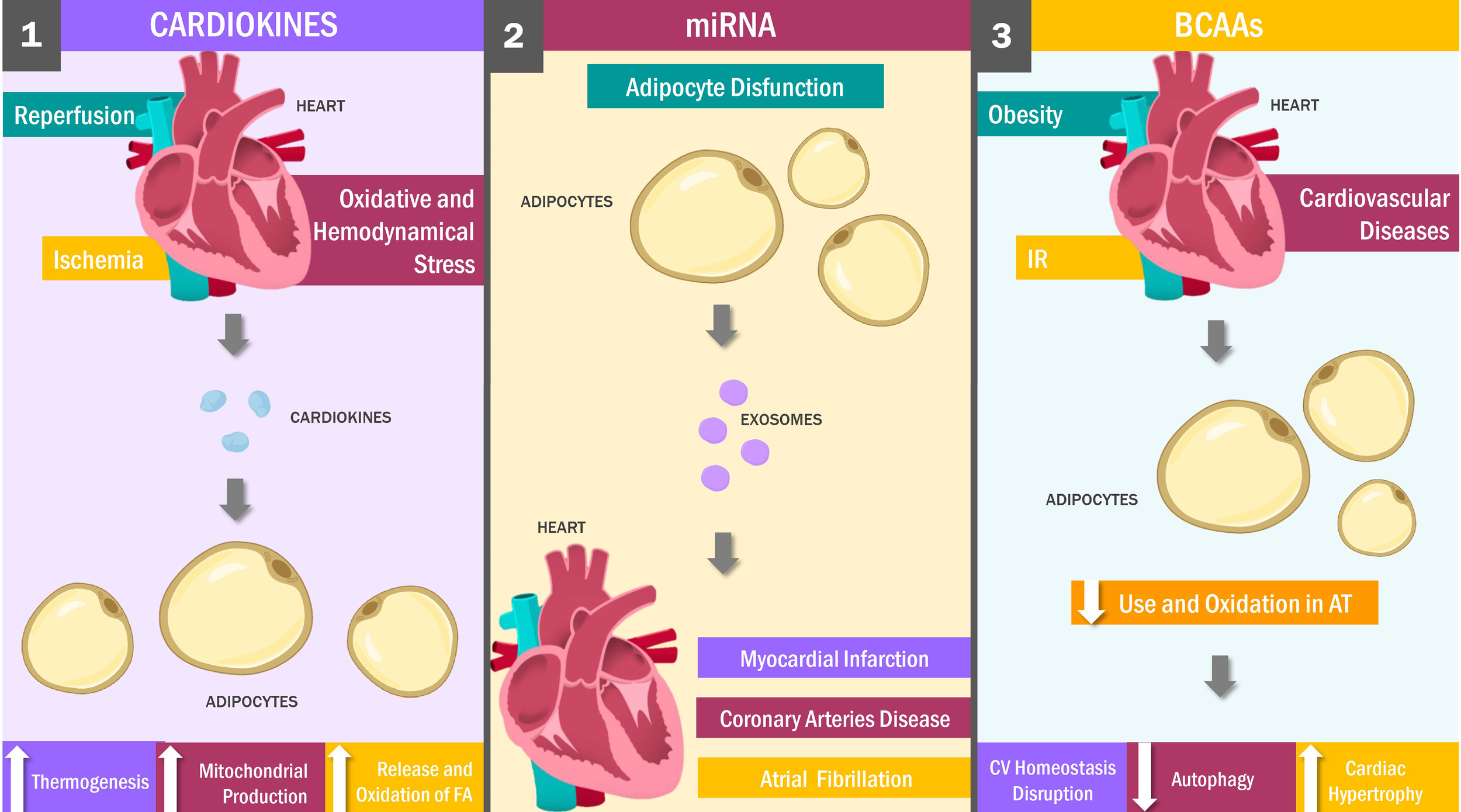

The mechanisms underlying these changes have not been fully elucidated yet; however, epigenetic changes such as PP2Cm, KLF15, or GRK2 gene expression during heart disease could modify the cells’ metabolic profile. Subsequently, alterations in BCAA catabolism and use caused by these metabolic changes could lead to rising arterial amino acid levels (27, 153). Likewise, AT inflammation has been linked to tricarboxylic acid cycle modifications, resulting in reduced BCAA catabolism and use, which provides an alternative explanation for the accumulation of amino acids in plasma (155, 156) (Figure 2). These variations in local and organic BCAA concentrations lead to chronic mTOR receptor expression in myocardial cells, and thus, autophagy suppression pathways induction, alterations in insulin sensitivity and tissue transport, as well as protein synthesis pathway activation, promoting the inhibition of autophagy protective functions, by modifying the bioenergetic heart homeostasis and cardiac hypertrophy stimulation, respectively (157).

Figure 2

Heart and Adipose Tissue Crosstalk: Key Messengers. Cardiokines: stimuli such as cardiac ischemia, reperfusion, oxidative and hemodynamic stress stimulate the production of cardiokines, which signaling in an endocrine and paracrine mechanism to the adipose tissue promoting weight loss by increasing thermogenesis and both the release and oxidation of fatty acids. Adipose tissue dysfunction is a stimulus for miRNAs release, which travel through the bloodstream to the myocardial tissue inside exosomes, exerting cardioprotective against myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease and atrial fibrillation. On the other hand, obesity, IR and cardiovascular diseases decrease BCAAs oxidation in adipose tissue, which decreases autophagy with heart hypertrophy and, finally, the alteration of the bioenergetic homeostasis of the heart. FA, Fatty Acids; AT, Adipose Tissue; CV, Cardiovascular; IR, Insulin resistance.

Given these findings, it is not surprising that a correlation between heart failure and elevated BCAA levels has been found in numerous studies (152, 158). For example, a clinical trial conducted by Peterson et al. evaluated total amino acid concentrations in patients with heart failure, finding them to be abnormally high (159). Similarly, results reported by Kato et al. indicated elevated plasma amino acid levels as a consequence of metabolic changes in sodium-sensitive hypertensive rodents (160). In contrast, a clinical trial conducted by Aquilani et al. reports a decreased BCAA levels in patients with chronic heart failure compared to healthy individuals. Although these results could seem contradictory, factors such as the site of amino acid quantification and the variability in BCAA levels due to both duration and severity of pre-existing disease could explain the differences between findings (161). In this regard, AT and cardiac tissue exert a reciprocal influence on each other in various pathological scenarios via modifications in BCAA catabolism and consumption (154–156, 162).

3.3 Cardiokines

The heart is conventionally viewed as a contractile organ acting as a muscular pump to provide nutrients to the body (163). Beyond these functions, however, it can exert regulatory actions on other organs, such as the kidney, liver or AT (164). These modulatory activities are carried out mainly through molecules synthesized and secreted by the heart, known as cardiokines (165–168).

To date, it has identified up to 16 cardiokines, which are thought to exert homeostatic functions related to growth, cell death, fibrosis, hypertrophy and cardiac remodeling. In addition, although these molecules have predominantly paracrine and autocrine functions, certain cardiokines show endocrine mechanisms of action, allowing them to act on distant tissues (169). Such is the case of the firsts cardiokines identified, known as atrial (ANP) and brain (BNP) natriuretic peptides (NPs) (164, 170). Besides their participation as blood pressure regulators, both peptides play a critical role in modulating AT energy metabolism (171).

In this way, different stimuli such as ischemia, reperfusion, OS, hemodynamic stress, and cardiac hypertrophy can trigger NP synthesis and release by different cardiac cells into the circulation and ultimately reaching the AT (172). In this tissue, NPs bind to the NPR-A receptors, activating the guanylyl cyclase and cGMP formation. This process, in turn, activates the PKG, an enzyme responsible for phosphorylating key factors such as UCP-1, PPARGC1A, CYCS, PRD1-BF 1 and RIZ1, inducing white adipocyte browning, increasing lipogenesis, mitochondrial biogenesis and lipid oxidation (171, 173).

Collectively, these phenomena have a double effect. Fatty acids are released into the bloodstream as energy substrates to compensate for the low heart contractility observed during the abovementioned pathological scenarios (174), while increased mitochondrial production, thermogenesis, and fatty acid oxidation promote weight loss (175, 176). These reports were verified by other studies showing abnormally elevated NP concentrations during CVD and decreased levels of these peptides in obese individuals (164, 177). For example, in one study carried out by Kovacova et al. (29), the NPRR expression was significantly lower in obese than normal-weight individuals. These findings replicated those obtained in studies carried out in humans and murine, wherein plasma and cardiac levels of both BNPs and ANPs were significantly lower in obese than normal-weight subjects (175, 178).

3.4 miRNAs and EVs

miRNAs are small, non-coding RNA molecules functioning as regulatory agents in numerous physiological and pathological processes by participating in post-transcriptional mRNA and translation into protein processes (179, 180). These molecules are synthesized in response to a wide range of stimuli by different tissues (181), among which AT and EAT are responsible for the production and release of multiple miRNA varieties (14, 182).

Most miRNAs on EAT operate through autocrine fashion and have been implicated in various AT processes such as adipocyte differentiation, fatty acid metabolism, cholesterol homeostasis, adipogenesis, browning and inflammation (183–185). Other miRNAs are released into the circulation via exosomes, from where they travel to and penetrate the heart or other distant organs (186). Although it has been established that EAT releases different miRNAs towards the heart in response to tissue dysfunction or certain specific stimuli (13), but the functions and underlying mechanisms of action have not been fully characterized. Nonetheless, recent studies have identified new miRNAs and their potential role in the pathogenesis and development of heart diseases (12, 187, 188).

In this vein, miRNAs have been implicated in atrial fibrillation (AF), as demonstrated in the study carried out by Liu et al. (189), wherein miR-320d were transported in vitro by exosomes to FA cardiomyocytes, revealing enhanced cell viability and decreased post-transfection cardiomyocytes apoptosis, reversing several FA characteristic effects by inhibiting factor STAT3. Likewise, a possible cardioprotective role has been suggested to miR-146a due to an inhibitory effect on early growth response factor-1 (EGRF1) in suppressing typical post-MI phenomena such as apoptosis, inflammatory responses and cardiac fibrosis (190). Similar results were obtained by Luo et al., in which miR-126 overexpression in hypoxic H9c2 cells led to reduced local inflammation, pro-fibrotic protein expression, and microvasculature and cell migration, thus mitigating the effects of cardiac injury in the infarcted area (191).

Numerous miRNAs play a positive role in some cardiac pathologies beyond acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and AF, including CAD. For example, it has been shown that during CAD progression, miRNA-3614 expression is downregulated in EAT, which produces an inhibitory effect on factors such as TRAF6, which regulates immune cell recruitment and activation as apoptosis and cardiac remodeling during myocardial ischemia (189, 192). In this context, a study by Zou et al. identified miR-410-5p and its promoting effects on cardiac fibrosis in mice with regular diets by silencing Smad7; concurrently, miR-410-5p demonstrated anti-fibrotic effects in mice fed high-fat diets (193). These results suggest a dual role for miRNAs in cardiovascular pathologies; besides the cardioprotective role of some miRNAs, these molecules can exert harmful effects on cardiac tissue, promoting effects such as local inflammation, hypertrophy, remodeling and cardiac fibrosis in different CVDs (183, 194–198).

4 Non-Pharmacological Approach to Adipocyte-Myocardiocyte Defective Signaling: Impact of Lifestyle

Preclinical and clinical evidence suggests that positive lifestyle changes derived from increased PA and NI could improve the above-described pro-inflammatory metabolic status of obese patients, highlighting their utility as possible non-pharmacological therapeutic strategies to manage obesity and cardiovascular risk.

In this regard, studies suggest that PA reduces circulating levels of insulin, leptin, and pro-inflammatory cytokines and raise adiponectin and apelin concentrations (199–202). In addition, increasing PA has been linked to heightened endothelial NOS (eNOS) expression and iNOS expression reduction (199, 203). These findings suggest that PA as a strategy helps restore a healthy metabolic state at the preclinical level.

Additionally, clinical studies have reported an anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective and slimming effect of PA. For example, a study in obese men showed that exercise was more effective than diet in reducing body weight (BW), improving the systemic inflammatory profile and IR and circulating levels of adipokines (204). Likewise, a study conducted in obese patients with T2DM subjected to dietary restriction and aerobic exercise reported that after a 3-month intervention, adiponectin levels rose while BMI and TNF-α, IL-6 and leptin levels fell significantly (205).

Concerning the different intensities of PA, a clinical trial demonstrated that moderate exercise combined with calorie restriction aided in normalizing adiponectin, leptin and resistin levels in obese adolescents (206). Furthermore, a meta-analysis performed by Maillard et al. (207) reported that high-intensity interval training effectively reduced SCAT and VAT. Similarly, another meta-analysis found that both moderate and high-intensity PA have a similar effect on weight reduction and body composition; however, results were seen more quickly when performing high-intensity exercise (208). Therefore, besides its anti-inflammatory properties, exercise can reduce BW, indirectly counteracting SickAT defective signaling by modifying its composition.

Studies have also demonstrated that PA has a regulatory effect on circulating microRNAs in individuals with cardiometabolic abnormalities. In this context, a clinical trial showed that circulating levels of miR-192 and miR-193b (associated with a prediabetic state) were modified after 16-week exercise intervention (209). Along similar lines, a combined aerobic and resistance exercise program in obese patients for three months was associated with significantly decreased levels of the inflammatory miRNA miR-146a-5p (210).

Aside from the weight loss achieved with exercise, dietary interventions have also been shown to positively impact AT and CVS crosstalk. In this regard, it has been proven that caloric restriction in the rat diet causes significantly reduced expression of iNOS, TNF-α and IL-1β in PVAT (211). Furthermore, another study conducted in rats showed that calorie control-induced weight loss was associated with improved endothelial NOS function, reduced TNF-α levels and normalized plasma adipokines y hormones levels such as leptin and insulin (212). Therefore, diet is a rationale tool to improve the cardiovascular functionality of the PVAT.

In another study, Kim et al. showed that intermittent fasting (IF) with an isocaloric diet increased VEGF expression in WAT, favoring macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype, which is linked to increased thermogenesis and AT browning (213). In this regard, a clinical trial in obese patients reported that IF combined with caloric restriction and liquid meals promotes significant BW loss and improves risk indicators for CAD (214). Furthermore, other studies conducted by the same research group (215) and Trepanowski et al. (216) were able to show that in addition to reducing BW, the abovementioned diet decreases levels of leptin IL-6, TNF-α and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). These results point to IF and low-calorie diets as a possible strategy to manage AT visceral adiposity and secretory profile, owing to their cardioprotective effect.

Regarding the role of the nutritional maneuvers approach on circulating microRNAs, Hsieh et al. (217) showed through a preclinical study that a low-fat diet could reverse obesity-associated inflammatory miRNA profiles via BW reduction. Consistent with this finding, evidence in humans suggests that BW loss achieved by very-low-calorie NI in obese women (218) or protein-rich diets in obese men (219) allow positive modulation of circulating levels of different miRNAs such as miR-34a, miR-208, miR-193a, miR-223, miR-320, miR-433, miR-568 and miR-181a.

Likewise, preclinical and clinical studies have shown the prebiotic and probiotic effects in reducing cardiovascular risk by leptin resistance (220) and leptin level reductions (221, 222). In addition, an adiponectin increase (223, 224) and lowering both apelin (225) and ANP levels (226) have been consistently reported, a fact attributed to HCD-induced GD correction and thus a reduced LPS-induced endotoxemia and SCFA levels. Likewise, 3-n PUFA supplementation has been associated with recovery of the adipokine and cardiokine profile, resulting in a healthier cardio-metabolic state. In this context, studies in animal models and humans have linked supplements administration with a significant reduction in leptin (227, 228), follistatin-like 1 (229) and BNP levels (230), and adiponectin increase (231). Finally, polyphenols such as lycopene, resveratrol and curcumin have also been linked to improved inflammatory and adipokine profile, body composition and cardiac fibrosis/hypertrophy in study subjects (232–235).

These data suggest that PA and different NI, either alone or in combination, are associated with the upregulation of adipokines, cardiokines, miRNAs and other components associated with crosstalk between AT and CVS. Therefore, these strategies are beneficial in reducing cardiovascular risk in obese patients due to their mechanisms capable of counteracting the characteristic pro-inflammatory state of SickAT.

5 Conclusions

Adipose tissue is a multifunctional exhibiting well-characterized inter-organ paracrine and endocrine networking, including myocardial tissue communication. Obesity is characterized by metabolic changes in SickAT caused by a hypoxic microenvironment due to adipocyte hypertrophy driving to immune cell infiltration and a systemic pro-inflammatory state affecting target cells such as cardiomyocytes. Excessive adipokines, microRNA, BCAAs characterize SickAT defective signaling, and other pro-inflammatory substances release altering myocardial cells function and, consequently, CVD development. Likewise, heart cells can also alter AT signals, thereby causing a vicious cycle that fuels meta-inflammation. Under this premise, lifestyle changes such as PA, low-calorie diets, IF, and food supplementation are fundamental non-pharmacological therapeutic tools to combat obesity and CVD due to their identified regulatory mechanisms in AT and CVS signaling.

Funding

This work was supported by research grant no. CC-0437-10-21-09-10 from Consejo de Desarrollo Científico, Humanístico y Tecnológico (CONDES), University of Zulia, and the research grant no. FZ-0058-2007 from Fundacite-Zulia.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Author contributions

Conceptualization: PD, MN, CC, and VB. Investigation: LD’M, MD, RC, MN, and MC. Writing – original draft: PD, MD, RC, MC, MB, JG, and ER. Writing – review and editing: VB, CC, JR, MB, and LD’M, JG. Funding acquisition: VB and JG. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

AF, atrial fibrillation; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; AT, adipose tissue; BAT, brown adipose tissue; BeAT, beige or brite adipose tissue; BMI, body mass index; BCAAs, Branched-chain amino acids; BW body weight; C/EBP, CCAAT-enhancer-binding proteins; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CVS, cardiovascular system; EAT, epicardial adipose tissue; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; FFA, free fatty acid; GD, gut dysbiosis; GM, gut microbiota; HCD, hypercaloric diet; IF, intermittent fasting; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; IR, insulin resistance; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; MetS, metabolic syndrome; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NI, nutritional intervention; NP, natriuretic peptide; OS, oxidative stress; PA, physical activity; PAT, pericardial adipose tissue; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ; PVAT, perivascular adipose tissue; SickAT, sick (dysfunctional) adipose tissue; SCAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue; SCFA, short-chain fatty acids; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; WAT, white adipose tissue; VAT, visceral adipose tissue.

References

1

World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (Accessed cited 2021 May 6).

2

CawleyJMeyerhoeferC. The Medical Care Costs of Obesity: An Instrumental Variables Approach. J Health Econ (2012) 31(1):219–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.10.003

3

FruhSM. Obesity: Risk Factors, Complications, and Strategies for Sustainable Long-Term Weight Management. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract (2017) 29(S1):S3–14. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12510

4

World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (Accessed cited 2021 May 6).

5

OikonomouEKAntoniadesC. The Role of Adipose Tissue in Cardiovascular Health and Disease. Nat Rev Cardiol (2019) 16(2):83–99. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0097-6

6

AntoniadesC. “Dysfunctional” Adipose Tissue in Cardiovascular Disease: A Reprogrammable Target or an Innocent Bystander? Cardiovasc Res (2017) 113(9):997–8. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx116

7

RodríguezABecerrilSEzquerroSMéndez-GiménezLFrühbeckG. Crosstalk Between Adipokines and Myokines in Fat Browning. Acta Physiol (Oxf) (2017) 219(2):362–81. doi: 10.1111/apha.12686

8

ArnerPKulytéA. MicroRNA Regulatory Networks in Human Adipose Tissue and Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol (2015) 11(5):276–88. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.25

9

AhimaRSLazarMA. Adipokines and the Peripheral and Neural Control of Energy Balance. Mol Endocrinol (2008) 22(5):1023–31. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0529

10

BohanRTianyuXTiantianZRuonanFHongtaoHQiongWet al. Gut Microbiota: A Potential Manipulator for Host Adipose Tissue and Energy Metabolism. J Nutr Biochem (2019) 64:206–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2018.10.020

11

MatsuzawaYShimomuraINakamuraTKenoYKotaniKTokunagaK. Pathophysiology and Pathogenesis of Visceral Fat Obesity. Obes Res (1995) 3(Suppl 2):187S–94S. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00462.x

12

VaccaMDi EusanioMCarielloMGrazianoGD’AmoreSPetridisFDet al. Integrative miRNA and Whole-Genome Analyses of Epicardial Adipose Tissue in Patients With Coronary Atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res (2016) 109(2):228–39. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv266

13

GaoLMeiSZhangSQinQLiHLiaoYet al. Cardio-Renal Exosomes in Myocardial Infarction Serum Regulate Proangiogenic Paracrine Signaling in Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Theranostics (2020) 10(3):1060–73. doi: 10.7150/thno.37678

14

TranK-VMajkaJSanghaiSSardanaMLessardDMilstoneZet al. Micro-RNAs Are Related to Epicardial Adipose Tissue in Participants With Atrial Fibrillation: Data From the MiRhythm Study. Front Cardiovasc Med (2019) 6:115. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2019.00115

15

GanXTZhaoGHuangCXRoweACPurdhamDMKarmazynM. Identification of Fat Mass and Obesity Associated (FTO) Protein Expression in Cardiomyocytes: Regulation by Leptin and Its Contribution to Leptin-Induced Hypertrophy. PloS One (2013) 8(9):e74235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074235

16

HrubyAHuFB. The Epidemiology of Obesity: A Big Picture. Pharmacoeconomics (2015) 33(7):673–89. doi: 10.1007/s40273-014-0243-x

17

MoreiraJBNWohlwendMWisløffU. Exercise and Cardiac Health: Physiological and Molecular Insights. Nat Metab (2020) 2(9):829–39. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-0262-1

18

ChaitAden HartighLJ. Adipose Tissue Distribution, Inflammation and Its Metabolic Consequences, Including Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med (2020) 7:22. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00022

19

CintiS. The Adipose Organ at a Glance. Dis Model Mech (2012) 5(5):588–94. doi: 10.1242/dmm.009662

20

MarimanECMWangP. Adipocyte Extracellular Matrix Composition, Dynamics and Role in Obesity. Cell Mol Life Sci (2010) 67(8):1277–92. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0263-4

21

BadimonLCubedoJ. Adipose Tissue Depots and Inflammation: Effects on Plasticity and Resident Mesenchymal Stem Cell Function. Cardiovasc Res (2017) 113(9):1064–73. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx096

22

RomachoTElsenMRöhrbornDEckelJ. Adipose Tissue and Its Role in Organ Crosstalk. Acta Physiol (Oxf) (2014) 210(4):733–53. doi: 10.1111/apha.12246

23

GaboritBVenteclefNAncelPPellouxVGariboldiVLeprincePet al. Human Epicardial Adipose Tissue Has a Specific Transcriptomic Signature Depending on Its Anatomical Peri-Atrial, Peri-Ventricular, or Peri-Coronary Location. Cardiovasc Res (2015) 108(1):62–73. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv208

24

LanthierNLeclercqIA. Adipose Tissues as Endocrine Target Organs. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol (2014) 28(4):545–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.07.002

25

KajimuraS. Advances in the Understanding of Adipose Tissue Biology. Nat Rev Endocrinol (2017) 13(2):69–70. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.211

26

IozzoP. Myocardial, Perivascular, and Epicardial Fat. Diabetes Care (2011) 34(Suppl 2):S371–9. doi: 10.2337/dc11-s250

27

FerreroKMKochWJ. Metabolic Crosstalk Between the Heart and Fat. Korean Circ J (2020) 50(5):379. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2019.0400

28

HeerenJMünzbergH. Novel Aspects of Brown Adipose Tissue Biology. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am (2013) 42(1):89–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.11.004

29

GasparRCPauliJRShulmanGIMuñozVR. An Update on Brown Adipose Tissue Biology: A Discussion of Recent Findings. Am J Physiol-Endocrinol Metab (2021) 320(3):E488–95. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00310.2020

30

SaitoM. Human Brown Adipose Tissue: Regulation and Anti-Obesity Potential Review. Endocr J (2014) 61(5):409–16. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ13-0527

31

LeitnerBPHuangSBrychtaRJDuckworthCJBaskinASMcGeheeSet al. Mapping of Human Brown Adipose Tissue in Lean and Obese Young Men. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2017) 114(32):8649–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705287114

32

FrühbeckGBecerrilSSáinzNGarrastachuPGarcía-VellosoMJ. BAT: A New Target for Human Obesity? Trends Pharmacol Sci (2009) 30(8):387–96. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.05.003

33

GasparRCMuñozVRAzevêdo MacêdoAPLins VieiraRPauliJR. A Palette of Adipose Tissue: Multiple Functionality and Extraordinary Plasticity. Trends Anat Physiol (2021) 4:013. doi: 10.24966/TAP-7752/100013

34

RosenwaldMWolfrumC. The Origin and Definition of Brite Versus White and Classical Brown Adipocytes. Adipocyte (2014) 3(1):4–9. doi: 10.4161/adip.26232

35

WuJCohenPSpiegelmanBM. Adaptive Thermogenesis in Adipocytes: Is Beige the New Brown? Genes Dev (2013) 27(3):234–50. doi: 10.1101/gad.211649.112

36

World Health Organization. Health Topics. Obesity (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/obesity#tab=tab_1.

37

RutkowskiJMSternJHSchererPE. The Cell Biology of Fat Expansion. J Cell Biol (2015) 208(5):501–12. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201409063

38

GhabenALSchererPE. Adipogenesis and Metabolic Health. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2019) 20(4):242–58. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0093-z

39

KusminskiCMHollandWLSunKParkJSpurginSBLinYet al. MitoNEET-Driven Alterations in Adipocyte Mitochondrial Activity Reveal a Crucial Adaptive Process That Preserves Insulin Sensitivity in Obesity. Nat Med (2012) 18(10):1539–49. doi: 10.1038/nm.2899

40

XueRWanYZhangSZhangQYeHLiY. Role of Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4 in the Differentiation of Brown Fat-Like Adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab (2014) 306(4):E363–372. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00119.2013

41

RosenEDMacDougaldOA. Adipocyte Differentiation From the Inside Out. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2006) 7(12):885–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm2066

42

GustafsonBHammarstedtAHedjazifarSSmithU. Restricted Adipogenesis in Hypertrophic Obesity: The Role of WISP2, WNT, and BMP4. Diabetes (2013) 62(9):2997–3004. doi: 10.2337/db13-0473

43

KarastergiouKMohamed-AliV. The Autocrine and Paracrine Roles of Adipokines. Mol Cell Endocrinol (2010) 318(1–2):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.11.011

44

HalbergNKhanTTrujilloMEWernstedt-AsterholmIAttieADSherwaniSet al. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1alpha Induces Fibrosis and Insulin Resistance in White Adipose Tissue. Mol Cell Biol (2009) 29(16):4467–83. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00192-09

45

CarrièreACarmonaM-CFernandezYRigouletMWengerRHPénicaudLet al. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Control the Transcription Factor CHOP-10/GADD153 and Adipocyte Differentiation: A Mechanism for Hypoxia-Dependent Effect. J Biol Chem (2004) 279(39):40462–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407258200

46

TrayhurnP. Hypoxia and Adipose Tissue Function and Dysfunction in Obesity. Physiol Rev (2013) 93(1):1–21. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2012

47

WangBWoodISTrayhurnP. PCR Arrays Identify Metallothionein-3 as a Highly Hypoxia-Inducible Gene in Human Adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2008) 368(1):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.036

48

MazzattiDLimF-LO’HaraAWoodISTrayhurnP. A Microarray Analysis of the Hypoxia-Induced Modulation of Gene Expression in Human Adipocytes. Arch Physiol Biochem (2012) 118(3):112–20. doi: 10.3109/13813455.2012.654611

49

EnginA. Adipose Tissue Hypoxia in Obesity and Its Impact on Preadipocytes and Macrophages: Hypoxia Hypothesis. Adv Exp Med Biol (2017) 960:305–26. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-48382-5_13

50

CildirGAkıncılarSCTergaonkarV. Chronic Adipose Tissue Inflammation: All Immune Cells on the Stage. Trends Mol Med (2013) 19(8):487–500. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.05.001

51

GuzikTJSkibaDSTouyzRMHarrisonDG. The Role of Infiltrating Immune Cells in Dysfunctional Adipose Tissue. Cardiovasc Res (2017) 113(9):1009–23. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvx108

52

WeisbergSPMcCannDDesaiMRosenbaumMLeibelRLFerranteAW. Obesity Is Associated With Macrophage Accumulation in Adipose Tissue. J Clin Invest (2003) 112(12):1796–808. doi: 10.1172/JCI200319246

53

AmanoSUCohenJLVangalaPTencerovaMNicoloroSMYaweJCet al. Local Proliferation of Macrophages Contributes to Obesity-Associated Adipose Tissue Inflammation. Cell Metab (2014) 19(1):162–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.017

54

FujisakaSUsuiIBukhariAIkutaniMOyaTKanataniYet al. Regulatory Mechanisms for Adipose Tissue M1 and M2 Macrophages in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Diabetes (2009) 58(11):2574–82. doi: 10.2337/db08-1475

55

KratzMCoatsBRHisertKBHagmanDMutskovVPerisEet al. Metabolic Dysfunction Drives a Mechanistically Distinct Pro-Inflammatory Phenotype in Adipose Tissue Macrophages. Cell Metab (2014) 20(4):614–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.08.010

56

PatsourisDLiP-PThaparDChapmanJOlefskyJMNeelsJG. Ablation of CD11c-Positive Cells Normalises Insulin Sensitivity in Obese Insulin Resistant Animals. Cell Metab (2008) 8(4):301–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.08.015

57

SunKKusminskiCMSchererPE. Adipose Tissue Remodeling and Obesity. J Clin Invest (2011) 121(6):2094–101. doi: 10.1172/JCI45887

58

CintiSMitchellGBarbatelliGMuranoICeresiEFaloiaEet al. Adipocyte Death Defines Macrophage Localisation and Function in Adipose Tissue of Obese Mice and Humans. J Lipid Res (2005) 46(11):2347–55. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500294-JLR200

59

NishimuraSManabeINagasakiMEtoKYamashitaHOhsugiMet al. CD8+ Effector T Cells Contribute to Macrophage Recruitment and Adipose Tissue Inflammation in Obesity. Nat Med (2009) 15(8):914–20. doi: 10.1038/nm.1964

60

WinerDAWinerSShenLWadiaPPYanthaJPaltserGet al. B Cells Promote Insulin Resistance Through Modulation of T Cells and Production of Pathogenic IgG Antibodies. Nat Med (2011) 17(5):610–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.2353

61

Mansuy-AubertVZhouQLXieXGongZHuangJ-YKhanARet al. Imbalance Between Neutrophil Elastase and Its Inhibitor α1-Antitrypsin in Obesity Alters Insulin Sensitivity, Inflammation, and Energy Expenditure. Cell Metab (2013) 17(4):534–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.005

62

TalukdarSOhDYBandyopadhyayGLiDXuJMcNelisJet al. Neutrophils Mediate Insulin Resistance in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet Through Secreted Elastase. Nat Med (2012) 18(9):1407–12. doi: 10.1038/nm.2885

63

PasaricaMSeredaORRedmanLMAlbaradoDCHymelDTRoanLEet al. Reduced Adipose Tissue Oxygenation in Human Obesity: Evidence for Rarefaction, Macrophage Chemotaxis, and Inflammation Without an Angiogenic Response. Diabetes (2009) 58(3):718–25. doi: 10.2337/db08-1098

64

SunKWernstedt AsterholmIKusminskiCMBuenoACWangZVPollardJWet al. Dichotomous Effects of VEGF-A on Adipose Tissue Dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2012) 109(15):5874–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200447109

65

VillaretAGalitzkyJDecaunesPEstèveDMarquesM-ASengenèsCet al. Adipose Tissue Endothelial Cells From Obese Human Subjects: Differences Among Depots in Angiogenic, Metabolic, and Inflammatory Gene Expression and Cellular Senescence. Diabetes (2010) 59(11):2755–63. doi: 10.2337/db10-0398

66

KikuchiRNakamuraKMacLauchlanSNgoDT-MShimizuIFusterJJet al. An Anti-Angiogenic Isoform of VEGF-A Contributes to Impaired Vascularization in Peripheral Artery Disease. Nat Med (2014) 20(12):1464–71. doi: 10.1038/nm.3703

67

NishimuraSManabeINagasakiMSeoKYamashitaHHosoyaYet al. In Vivo Imaging in Mice Reveals Local Cell Dynamics and Inflammation in Obese Adipose Tissue. J Clin Invest (2008) 118(2):710–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI33328

68

GreensteinASKhavandiKWithersSBSonoyamaKClancyOJeziorskaMet al. Local Inflammation and Hypoxia Abolish the Protective Anticontractile Properties of Perivascular Fat in Obese Patients. Circulation (2009) 119(12):1661–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.821181

69

BergGMiksztowiczVMoralesCBarchukM. Epicardial Adipose Tissue in Cardiovascular Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol (2019) 1127:131–43. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-11488-6_9

70

SpencerMUnalRZhuBRasouliNMcGeheeREPetersonCAet al. Adipose Tissue Extracellular Matrix and Vascular Abnormalities in Obesity and Insulin Resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2011) 96(12):E1990–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1567

71

SunKParkJGuptaOTHollandWLAuerbachPZhangNet al. Endotrophin Triggers Adipose Tissue Fibrosis and Metabolic Dysfunction. Nat Commun (2014) 5:3485. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4485

72

KhanTMuiseESIyengarPWangZVChandaliaMAbateNet al. Metabolic Dysregulation and Adipose Tissue Fibrosis: Role of Collagen VI. Mol Cell Biol (2009) 29(6):1575–91. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01300-08

73

GeigerKLeihererAMuendleinAStarkNGeller-RhombergSSaelyCHet al. Identification of Hypoxia-Induced Genes in Human SGBS Adipocytes by Microarray Analysis. PloS One (2011) 6(10):e26465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026465

74

YinJGaoZHeQZhouDGuoZYeJ. Role of Hypoxia in Obesity-Induced Disorders of Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Adipose Tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab (2009) 296(2):E333–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90760.2008

75

HayashiMSakataMTakedaTYamamotoTOkamotoYSawadaKet al. Induction of Glucose Transporter 1 Expression Through Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1alpha Under Hypoxic Conditions in Trophoblast-Derived Cells. J Endocrinol (2004) 183(1):145–54. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.05599

76

ParkHSKimJHSunBKSongSUSuhWSungJ-H. Hypoxia Induces Glucose Uptake and Metabolism of Adipose−Derived Stem Cells. Mol Med Rep (2016) 14(5):4706–14. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5796

77

Pérez de HerediaFWoodISTrayhurnP. Hypoxia Stimulates Lactate Release and Modulates Monocarboxylate Transporter (MCT1, MCT2, and MCT4) Expression in Human Adipocytes. Pflugers Arch (2010) 459(3):509–18. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0750-3

78

MylonisISimosGParaskevaE. Hypoxia-Inducible Factors and the Regulation of Lipid Metabolism. Cells (2019) 8(3):214. doi: 10.3390/cells8030214

79

BarchettaICiminiFACiccarelliGBaroniMGCavalloMG. Sick Fat: The Good and the Bad of Old and New Circulating Markers of Adipose Tissue Inflammation. J Endocrinol Invest (2019) 42(11):1257–72. doi: 10.1007/s40618-019-01052-3

80

ChakrabartiPKimJYSinghMShinY-KKimJKumbrinkJet al. Insulin Inhibits Lipolysis in Adipocytes via the Evolutionarily Conserved Mtorc1-Egr1-ATGL-Mediated Pathway. Mol Cell Biol (2013) 33(18):3659–66. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01584-12

81

ArnerPRydénM. Fatty Acids, Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Obes Facts (2015) 8(2):147–55. doi: 10.1159/000381224

82

Böni-SchnetzlerMBollerSDebraySBouzakriKMeierDTPrazakRet al. Free Fatty Acids Induce a Pro-Inflammatory Response in Islets via the Abundantly Expressed Interleukin-1 Receptor I. Endocrinology (2009) 150(12):5218–29. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0543

83

KarastergiouKFriedSK. Multiple Adipose Depots Increase Cardiovascular Risk via Local and Systemic Effects. Curr Atheroscler Rep (2013) 15(10):361. doi: 10.1007/s11883-013-0361-5

84

VillarroyaFCereijoRGavaldà-NavarroAVillarroyaJGiraltM. Inflammation of Brown/Beige Adipose Tissues in Obesity and Metabolic Disease. J Intern Med (2018) 284(5):492–504. doi: 10.1111/joim.12803

85

FerréPBurnolAFLeturqueATerretazJPenicaudLJeanrenaudBet al. Glucose Utilisation In Vivo and Insulin-Sensitivity of Rat Brown Adipose Tissue in Various Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Biochem J (1986) 233(1):249–52. doi: 10.1042/bj2330249

86

OravaJNuutilaPNoponenTParkkolaRViljanenTEnerbäckSet al. Blunted Metabolic Responses to Cold and Insulin Stimulation in Brown Adipose Tissue of Obese Humans. Obes (Silver Spring) (2013) 21(11):2279–87. doi: 10.1002/oby.20456

87

EstèveDBouletNVolatFZakaroff-GirardALedouxSCoupayeMet al. Human White and Brite Adipogenesis Is Supported by MSCA1 and Is Impaired by Immune Cells. Stem Cells (2015) 33(4):1277–91. doi: 10.1002/stem.1916

88

HillsRDPontefractBAMishconHRBlackCASuttonSCThebergeCR. Gut Microbiome: Profound Implications for Diet and Disease. Nutrients (2019) 11(7):1613. doi: 10.3390/nu11071613

89

RampelliSGuentherKTurroniSWoltersMVeidebaumTKouridesYet al. Pre-Obese Children’s Dysbiotic Gut Microbiome and Unhealthy Diets may Predict the Development of Obesity. Commun Biol (2018) 1(1):222. doi: 10.1155/2016/1629236

90

BackhedFDingHWangTHooperLVKohGYNagyAet al. The Gut Microbiota as an Environmental Factor That Regulates Fat Storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci (2004) 101(44):15718–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407076101

91

BäckhedFManchesterJKSemenkovichCFGordonJI. Mechanisms Underlying the Resistance to Diet-Induced Obesity in Germ-Free Mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2007) 104(3):979–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605374104

92

RidauraVKFaithJJReyFEChengJDuncanAEKauALet al. Gut Microbiota From Twins Discordant for Obesity Modulate Metabolism in Mice. Science (2013) 341(6150):1241214. doi: 10.1126/science.1241214

93

GhoshSSWangJYanniePJGhoshS. Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction, LPS Translocation, and Disease Development. J Endocr Soc (2020) 4(2):bvz039. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvz039

94

RohrMWNarasimhuluCARudeski-RohrTAParthasarathyS. Negative Effects of a High-Fat Diet on Intestinal Permeability: A Review. Adv Nutr (2020) 11(1):77–91. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmz061

95

GuoSAl-SadiRSaidHMMaTY. Lipopolysaccharide Causes an Increase in Intestinal Tight Junction Permeability In Vitro and In Vivo by Inducing Enterocyte Membrane Expression and Localisation of TLR-4 and CD14. Am J Pathol (2013) 182(2):375–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.10.014

96

CaniPDAmarJIglesiasMAPoggiMKnaufCBastelicaDet al. Metabolic Endotoxemia Initiates Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Diabetes (2007) 56(7):1761–72. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491

97

SongMJKimKHYoonJMKimJB. Activation of Toll-Like Receptor 4 Is Associated With Insulin Resistance in Adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2006) 346(3):739–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.170

98

CaesarRTremaroliVKovatcheva-DatcharyPCaniPDBäckhedF. Crosstalk Between Gut Microbiota and Dietary Lipids Aggravates WAT Inflammation Through TLR Signaling. Cell Metab (2015) 22(4):658–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.026

99

CaoWHuangHXiaTLiuCMuhammadSSunC. Homeobox A5 Promotes White Adipose Tissue Browning Through Inhibition of the Tenascin C/Toll-Like Receptor 4/Nuclear Factor Kappa B Inflammatory Signaling in Mice. Front Immunol (2018) 9:647. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00647

100

OklaMWangWKangIPashajACarrTChungS. Activation of Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4) Attenuates Adaptive Thermogenesis via Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. J Biol Chem (2015) 290(44):26476–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.677724

101

MuccioliGGNaslainDBäckhedFReigstadCSLambertDMDelzenneNMet al. The Endocannabinoid System Links Gut Microbiota to Adipogenesis. Mol Syst Biol (2010) 6:392. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.46

102

MyhrstadMCWTunsjøHCharnockCTelle-HansenVH. Dietary Fiber, Gut Microbiota, and Metabolic Regulation-Current Status in Human Randomized Trials. Nutrients (2020) 12(3):859. doi: 10.3390/nu12030859

103

BlachierFMariottiFHuneauJFToméD. Effects of Amino Acid-Derived Luminal Metabolites on the Colonic Epithelium and Physiopathological Consequences. Amino Acids (2007) 33(4):547–62. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0477-9

104

KimCH. Microbiota or Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Which Regulates Diabetes? Cell Mol Immunol (2018) 15(2):88–91. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.57

105

PostlerTSGhoshS. Understanding the Holobiont: How Microbial Metabolites Affect Human Health and Shape the Immune System. Cell Metab (2017) 26(1):110–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.05.008

106

RatajczakWRyłAMizerskiAWalczakiewiczKSipakOLaszczyńskaM. Immunomodulatory Potential of Gut Microbiome-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs). Acta Biochim Pol (2019) 66(1):1–12. doi: 10.18388/abp.2018_2648

107

On behalf of the Obesity Programs of nutrition, Education, Research and Assessment (OPERA) groupMuscogiuriGCantoneECassaranoSTuccinardiDBarreaLet al. Gut Microbiota: A New Path to Treat Obesity. Int J Obes Supp (2019) 9(1):10–9. doi: 10.1038/s41367-019-0011-7

108

TurnbaughPJLeyREMahowaldMAMagriniVMardisERGordonJI. An Obesity-Associated Gut Microbiome With Increased Capacity for Energy Harvest. Nature (2006) 444(7122):1027–31. doi: 10.1038/nature05414

109

SamuelBSShaitoAMotoikeTReyFEBackhedFManchesterJKet al. Effects of the Gut Microbiota on Host Adiposity Are Modulated by the Short-Chain Fatty-Acid Binding G Protein-Coupled Receptor, Gpr41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2008) 105(43):16767–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808567105

110

MussoGGambinoRCassaderM. Interactions Between Gut Microbiota and Host Metabolism Predisposing to Obesity and Diabetes. Annu Rev Med (2011) 62:361–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-012510-175505

111

GrassetEPuelACharpentierJColletXChristensenJETercéFet al. A Specific Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis of Type 2 Diabetic Mice Induces GLP-1 Resistance Through an Enteric NO-Dependent and Gut-Brain Axis Mechanism. Cell Metab (2017) 26(1):278. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.013

112

SchugarRCShihDMWarrierMHelsleyRNBurrowsAFergusonDet al. The TMAO-Producing Enzyme Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase 3 Regulates Obesity and the Beiging of White Adipose Tissue. Cell Rep (2017) 19(12):2451–61. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.077

113

CavallariJFFullertonMDDugganBMFoleyKPDenouESmithBKet al. Muramyl Dipeptide-Based Postbiotics Mitigate Obesity-Induced Insulin Resistance via IRF4. Cell Metab (2017) 25(5):1063–74.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.03.021

114

VirtueATMcCrightSJWrightJMJimenezMTMowelWKKotzinJJet al. The Gut Microbiota Regulates White Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Obesity via a Family of microRNAs. Sci Transl Med (2019) 11(496):eaav1892. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav1892

115

PattersonERyanPMCryanJFDinanTGRossRPFitzgeraldGFet al. Gut Microbiota, Obesity and Diabetes. Postgrad Med J (2016) 92(1087):286–300. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133285

116

Martínez-SánchezN. There and Back Again: Leptin Actions in White Adipose Tissue. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21(17):6039. doi: 10.3390/ijms21176039

117

IzquierdoAGCrujeirasABCasanuevaFFCarreiraMC. Leptin, Obesity, and Leptin Resistance: Where Are We 25 Years Later? Nutrients (2019) 11(11):2704. doi: 10.3390/nu11112704

118

FusterJJOuchiNGokceNWalshK. Obesity-Induced Changes in Adipose Tissue Microenvironment and Their Impact on Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Res (2016) 118(11):1786–807. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306885

119

TeixeiraTMda CostaDCResendeACSoulageCOBezerraFFDalepraneJB. Activation of Nrf2-Antioxidant Signaling by 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol Prevents Leptin-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Human Endothelial Cells. J Nutr (2017) 147(4):506–13. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.239475

120

YamagishiSIEdelsteinDDuXLKanedaYGuzmánMBrownleeM. Leptin Induces Mitochondrial Superoxide Production and Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 Expression in Aortic Endothelial Cells by Increasing Fatty Acid Oxidation via Protein Kinase a. J Biol Chem (2001) 276(27):25096–100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007383200

121

HongoSWatanabeTAritaSKanomeTKageyamaHShiodaSet al. Leptin Modulates ACAT1 Expression and Cholesterol Efflux From Human Macrophages. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab (2009) 297(2):E474–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90369.2008

122

SinghSLohakareAC. Association of Leptin and Carotid Intima-Media Thickness in Overweight and Obese Individuals: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Assoc Physicians India (2020) 68(8):19–23. doi: 10.1155/2018/4285038

123

RahmaniAToloueitabarYMohsenzadehYHemmatiRSayehmiriKAsadollahiK. Association Between Plasma Leptin/Adiponectin Ratios With the Extent and Severity of Coronary Artery Disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord (2020) 20(1):474. doi: 10.1186/s12872-020-01723-7

124

GanXTZhaoGHuangCXRoweACPurdhamDMKarmazynM. Identification of Fat Mass and Obesity Associated (FTO) Protein Expression in Cardiomyocytes: Regulation by Leptin and Its Contribution to Leptin-Induced Hypertrophy. PloS One (2013) 8(9):e74235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074235

125

XuF-PChenM-SWangY-ZYiQLinS-BChenAFet al. Leptin Induces Hypertrophy via Endothelin-1-Reactive Oxygen Species Pathway in Cultured Neonatal Rat Cardiomyocytes. Circulation (2004) 110(10):1269–75. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140766.52771.6D

126

ZeidanAHunterJCJavadovSKarmazynM. mTOR Mediates RhoA-Dependent Leptin-Induced Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy. Mol Cell Biochem (2011) 352(1):99–108. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0744-2

127

HouNLuoM-SLiuS-MZhangH-NXiaoQSunPet al. Leptin Induces Hypertrophy Through Activating the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor α Pathway in Cultured Neonatal Rat Cardiomyocytes. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol (2010) 37(11):1087–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2010.05442.x

128

PeregoLPizzocriPCorradiDMaisanoFPaganelliMFiorinaPet al. Circulating Leptin Correlates With Left Ventricular Mass in Morbid (Grade III) Obesity Before and After Weight Loss Induced by Bariatric Surgery: A Potential Role for Leptin in Mediating Human Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2005) 90(7):4087–93. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1963

129

Barouch LiliABerkowitz DanEHarrison RobertWO’Donnell ChristopherPHare JoshuaM. Disruption of Leptin Signaling Contributes to Cardiac Hypertrophy Independently of Body Weight in Mice. Circulation (2003) 108(6):754–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000083716.82622.FD

130

MartinSSBlahaMJMuseEDQasimANReillyMPBlumenthalRSet al. Leptin and Incident Cardiovascular Disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Atherosclerosis (2015) 239(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.12.033

131

HallMEMareadyMWHallJEStecDE. Rescue of Cardiac Leptin Receptors in Db/Db Mice Prevents Myocardial Triglyceride Accumulation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab (2014) 307(3):E316–25. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00005.2014

132

LiebWXanthakisVSullivanLMAragamJPencinaMJLarsonMGet al. Longitudinal Tracking of Left Ventricular Mass Over the Adult Life Course: Clinical Correlates of Short- and Long-Term Change in the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation (2009) 119(24):3085–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.824243

133

Mohamed-AliVGoodrickSRaweshAKatzDRMilesJMYudkinJSet al. Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue Releases Interleukin-6, But Not Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha, In Vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (1997) 82(12):4196–200. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4450

134

Yamauchi-TakiharaKKishimotoT. Cytokines and Their Receptors in Cardiovascular Diseases–Role of Gp130 Signaling Pathway in Cardiac Myocyte Growth and Maintenance. Int J Exp Pathol (2000) 81(1):1–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.2000.00139.x

135

YuX-WChenQKennedyRHLiuSJ. Inhibition of Sarcoplasmic Reticular Function by Chronic Interleukin-6 Exposure via iNOS in Adult Ventricular Myocytes. J Physiol (2005) 566(Pt 2):327–40. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086686

136

FontesJARoseNRČihákováD. The Varying Faces of IL-6: From Cardiac Protection to Cardiac Failure. Cytokine (2015) 74(1):62–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.12.024

137

FuchsMHilfikerAKaminskiKHilfiker-KleinerDGuenerZKleinGet al. Role of Interleukin-6 for LV Remodeling and Survival After Experimental Myocardial Infarction. FASEB J (2003) 17(14):2118–20. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0331fje

138

YanATYanRTCushmanMRedheuilATracyRPArnettDKet al. Relationship of Interleukin-6 With Regional and Global Left-Ventricular Function in Asymptomatic Individuals Without Clinical Cardiovascular Disease: Insights From the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J (2010) 31(7):875–82. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp454

139

Markousis-MavrogenisGTrompJOuwerkerkWDevalarajaMAnkerSDClelandJGet al. The Clinical Significance of Interleukin-6 in Heart Failure: Results From the BIOSTAT-CHF Study. Eur J Heart Failure (2019) 21(8):965–73. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1482

140

HuiXLamKSLVanhouttePMXuA. Adiponectin and Cardiovascular Health: An Update. Br J Pharmacol (2012) 165(3):574–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01395.x

141

DongFRenJ. Adiponectin Improves Cardiomyocyte Contractile Function in Db/Db Diabetic Obese Mice. Obes (Silver Spring) (2009) 17(2):262–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.545

142

AminRHMathewsSTAlliALeffT. Endogenously Produced Adiponectin Protects Cardiomyocytes From Hypertrophy by a Pparγ-Dependent Autocrine Mechanism. Am J Physiol-Heart Circ Physiol (2010) 299(3):H690–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01032.2009

143

TaoLGaoEJiaoXYuanYLiSChristopher TheodoreAet al. Adiponectin Cardioprotection After Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Involves the Reduction of Oxidative/Nitrative Stress. Circulation (2007) 115(11):1408–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.666941

144

IkedaYOhashiKShibataRPimentelDRKiharaSOuchiNet al. Cyclooxygenase-2 Induction by Adiponectin Is Regulated by a Sphingosine Kinase-1 Dependent Mechanism in Cardiac Myocytes. FEBS Lett (2008) 582(7):1147–50. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.03.002

145

CaoYTaoLYuanYJiaoXLauWBWangYet al. Endothelial Dysfunction in Adiponectin Deficiency and Its Mechanisms Involved. J Mol Cell Cardiol (2009) 46(3):413–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.10.014

146

PischonT. Plasma Adiponectin Levels and Risk of Myocardial Infarction in Men. JAMA (2004) 291(14):1730. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1730

147

KozakovaMMuscelliEFlyvbjergAFrystykJMorizzoCPalomboCet al. Adiponectin and Left Ventricular Structure and Function in Healthy Adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2008) 93(7):2811–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2580

148

Sook LeeEParkSKimESook YoonYAhnH-YParkC-Yet al. Association Between Adiponectin Levels and Coronary Heart Disease and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Epidemiol (2013) 42(4):1029–39. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt087

149

Van BerendoncksAMGarnierABeckersPHoymansVYPossemiersNFortinDet al. Functional Adiponectin Resistance at the Level of the Skeletal Muscle in Mild to Moderate Chronic Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail (2010) 3(2):185–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.885525

150

MenonVLiLWangXGreeneTBalakrishnanVMaderoMet al. Adiponectin and Mortality in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol (2006) 17(9):2599–606. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006040331

151

SunHWangY. Branched Chain Amino Acid Metabolic Reprogramming in Heart Failure. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Mol Basis Dis (2016) 1862(12):2270–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.09.009

152

WangWZhangFXiaYZhaoSYanWWangHet al. Defective Branched Chain Amino Acid Catabolism Contributes to Cardiac Dysfunction and Remodeling Following Myocardial Infarction. Am J Physiol-Heart Circ Physiol (2016) 311(5):H1160–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00114.2016

153

LiTZhangZKolwiczSCAbellLRoeNDKimMet al. Defective Branched-Chain Amino Acid Catabolism Disrupts Glucose Metabolism and Sensitises the Heart to Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Cell Metab (2017) 25(2):374–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.11.005

154

PisarenkoOI. Mechanisms of Myocardial Protection by Amino Acids: Facts and Hypotheses. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol (1996) 23(8):627–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb01748.x

155

HalamaAHorschMKastenmüllerGMöllerGKumarPPrehnCet al. Metabolic Switch During Adipogenesis: From Branched Chain Amino Acid Catabolism to Lipid Synthesis. Arch Biochem Biophysics (2016) 589:93–107. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.09.013

156

HermanMAShePPeroniODLynchCJKahnBB. Adipose Tissue Branched Chain Amino Acid (BCAA) Metabolism Modulates Circulating BCAA Levels*. J Biol Chem (2010) 285(15):11348–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.075184

157

HuangYZhouMSunHWangY. Branched-Chain Amino Acid Metabolism in Heart Disease: An Epiphenomenon or a Real Culprit? Cardiovasc Res (2011) 90(2):220–3. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr070

158

TobiasDKLawlerPRHaradaPHDemlerOVRidkerPMMansonJEet al. Circulating Branched-Chain Amino Acids and Incident Cardiovascular Disease in a Prospective Cohort of US Women. Circ Genom Precis Med (2018) 11(4):e002157. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGEN.118.002157

159

PetersonMBMeadRJWeltyJD. Free Amino Acids in Congestive Heart Failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol (1973) 5(2):139–47. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(73)90047-3

160

KatoTNiizumaSInuzukaYKawashimaTOkudaJTamakiYet al. Analysis of Metabolic Remodeling in Compensated Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail (2010) 3(3):420–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.888479

161

AquilaniRLa RovereMCorbelliniDPasiniEVerriMBarbieriAet al. Plasma Amino Acid Abnormalities in Chronic Heart Failure. Mechanisms, Potential Risks and Targets in Human Myocardium Metabolism. Nutrients (2017) 9(11):1251. doi: 10.3390/nu9111251

162