95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Endocrinol. , 12 December 2019

Sec. Cellular Endocrinology

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00869

This article is part of the Research Topic Hormone Action and Signal Transduction in Endocrine Physiology and Disease View all 12 articles

G. Karina Parra-Mercado1†

G. Karina Parra-Mercado1† Alma M. Fuentes-Gonzalez1†

Alma M. Fuentes-Gonzalez1† Judith Hernandez-Aranda1

Judith Hernandez-Aranda1 Monica Diaz-Coranguez1

Monica Diaz-Coranguez1 Frank M. Dautzenberg2

Frank M. Dautzenberg2 Kevin J. Catt3

Kevin J. Catt3 Richard L. Hauger4,5

Richard L. Hauger4,5 J. Alberto Olivares-Reyes1*

J. Alberto Olivares-Reyes1*In the present study, we determined the cellular regulators of ERK1/2 and Akt signaling pathways in response to human CRF1 receptor (CRF1R) activation in transfected COS-7 cells. We found that Pertussis Toxin (PTX) treatment or sequestering Gβγ reduced CRF1R-mediated activation of ERK1/2, suggesting the involvement of a Gi-linked cascade. Neither Gs/PKA nor Gq/PKC were associated with ERK1/2 activation. Besides, CRF induced EGF receptor (EGFR) phosphorylation at Tyr1068, and selective inhibition of EGFR kinase activity by AG1478 strongly inhibited the CRF1R-mediated phosphorylation of ERK1/2, indicating the participation of EGFR transactivation. Furthermore, CRF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation was not altered by pretreatment with batimastat, GM6001, or an HB-EGF antibody indicating that metalloproteinase processing of HB-EGF ligands is not required for the CRF-mediated EGFR transactivation. We also observed that CRF induced Src and PYK2 phosphorylation in a Gβγ-dependent manner. Additionally, using the specific Src kinase inhibitor PP2 and the dominant-negative-SrcYF-KM, it was revealed that CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation depends on Src activation. PP2 also blocked the effect of CRF on Src and EGFR (Tyr845) phosphorylation, further demonstrating the centrality of Src. We identified the formation of a protein complex consisting of CRF1R, Src, and EGFR facilitates EGFR transactivation and CRF1R-mediated signaling. CRF stimulated Akt phosphorylation, which was dependent on Gi/βγ subunits, and Src activation, however, was only slightly dependent on EGFR transactivation. Moreover, PI3K inhibitors were able to inhibit not only the CRF-induced phosphorylation of Akt, as expected, but also ERK1/2 activation by CRF suggesting a PI3K dependency in the CRF1R ERK signaling. Finally, CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 activation was similar in the wild-type CRF1R and the phosphorylation-deficient CRF1R-Δ386 mutant, which has impaired agonist-dependent β-arrestin-2 recruitment; however, this situation may have resulted from the low β-arrestin expression in the COS-7 cells. When β-arrestin-2 was overexpressed in COS-7 cells, CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation was markedly upregulated. These findings indicate that on the base of a constitutive CRF1R/EGFR interaction, the Gi/βγ subunits upstream activation of Src, PYK2, PI3K, and transactivation of the EGFR are required for CRF1R signaling via the ERK1/2-MAP kinase pathway. In contrast, Akt activation via CRF1R is mediated by the Src/PI3K pathway with little contribution of EGFR transactivation.

Behavioral, cognitive, neuroendocrine, and autonomic responses to stress are regulated by CRF1 and CRF2 receptors (CRF1R and CRF2R) (1–3). The preferred mode of signal transduction by both CRF receptors was initially believed to be activation of the Gs/adenylyl cyclase/PKA signaling pathway (1–3). Subsequently, CRF1R and CRF2R were also found to signal via the PLC/PKC cascade stimulating intracellular calcium mobilization and IP3 formation (1–4). Besides, both CRF receptors can activate mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascades in neuronal, cardiac, and myometrial cells endogenously expressing CRF1R or CRF2R and in recombinant cell lines expressing either receptor (2, 3, 5, 6). Several reports suggested that cellular background directed CRF1R to signal selectively via a specific MAP kinase pathway. For example, agonist-activated CRF1Rs stimulated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAP kinases in PC12 and fetal microglial cells (7, 8) while CRF1Rs activated ERK1/2 but not JNK and p38 in CHO cells (9). In human mast cells and HaCaT keratinocytes, on the other hand, CRF1Rs induce phosphorylation of p38 but not ERK or JNK MAP kinases (10, 11). Most studies suggest, however, that the ERK1/2 cascade is the MAP kinase pathway preferentially used by CRF receptors (5, 9, 12, 13).

Signaling via the cyclic AMP (cAMP)-PKA pathway by Gs-coupled GPCRs has been proposed to mediate upstream activation of the ERK cascade in cells with high B-Raf expression (14). Consistent with this concept, PKA regulates CRF1R-mediated ERK activation and ERK-dependent Elk1 transcription in AtT-20 pituitary cells that express high B-Raf levels (15). Kageyama et al. (16) found, however, that ERK activation by CRF1R was mediated by a PKA-independent mechanism in AtT-20 cells. Moreover, other studies have reported that PKA does not play a role in CRF1R ERK signaling in rat CATH.a and rat fetal microglial cells, locus coeruleus neurons, and transfected CHO cells (8, 9, 12, 17). CRF1R can also activate the ERK1/2 cascade via a PKC-dependent mechanism, based on data showing that pretreatment with a PLC or PKC inhibitor blocked urocortin 1 (Ucn1)-stimulated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in CRF1R-expressing human myometrial, CHO, and HEK293 cells (12, 13), and in rat hippocampal neurons (18). PKC inhibitor pretreatment, however, failed to block CRF- and Ucn1-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in CRF1R-expressing pituitary AtT20 cells and brain-derived CATH.a cells expressing both CRF receptors (12, 16). These findings suggest that cellular background may also govern the ability of PKA or PKC pathways to regulate CRF1R ERK1/2 signaling similar to its possible role in mediating CRF1R selective activation of a specific MAP kinase cascade.

MEK1/2-mediated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 at Thr202 and Tyr204 during CRF1R and CRF2R signaling in various cell lines has been confirmed by inhibiting ERK1/2 activation with PD98059 (2, 9, 12, 13, 19). Inhibiting C-Raf function by pretreatment with R1-K1 inhibitor or blocking Ras activation by transfection with the dominant-negative mutant RasS17N inhibited Ucn1-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in CRF1R-expressing CHO and HEK293 cells (5, 12). CRF2R activation by urocortin 2 (Ucn2) and urocortin 3 (Ucn3) has also been shown to signal via the Ras→C-Raf→MEK1/2 cascade in rat cardiomyocytes, based on the ability of manumycin A (a Ras inhibitor) and R1-K1 to abolish ERK1/2 phosphorylation (19). Other research has provided evidence for a phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent mechanism contributing to CRF1R- and CRF2R-mediated ERK1/2 activation in HEK293, CHO, A7r5, and CATH.a cells (5, 9, 12). EGF receptor (EGFR) transactivation, possibly by matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-mediated ligand release, has been shown to contribute to Ucn1-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in HEK293 cells, although the mechanisms for CRF1R-mediated transactivation of the EGFR were not determined (5). Furthermore, another study reported that CRF receptor ERK signaling in the mouse atrial HL-1 cardiomyocyte line involved activation of Src (20).

In addition, activation of CRF1R or CRF2(b)R can stimulate phosphorylation of Akt (5, 21). CRF2(b)R Akt signaling in HEK293 cells is mediated by pertussis-sensitive G proteins and PI3K but not by cAMP-stimulated activation of PKA or EPAC, or by PKC (21). The mechanisms regulating Akt signal transduction by CRF1R, however, have not been investigated. Because upstream kinase pathway mediation of CRF1R signal transduction via the ERK and Akt cascades are not well-understood, the primary goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that Src tyrosine kinase and EGFR transactivation are essential regulators of these CRF1R signaling pathways. We also sought to determine the relative importance of G protein βγ subunits, second messenger kinases, and PI3K in the activation of the ERK1/2 and Akt cascades by the CRF1R. The results of our study indicate that upstream utilization of Src and PI3K are involved in ERK and Akt signal transduction by the agonist-activated CRF1R in COS-7 cells, without mediation by PKA and PKC, while transactivation of the EGFR is mainly required for CRF1R to stimulate phosphorylation of ERK but not for Akt activation.

General reagents utilized were as follows: (i) DMEM, fetal bovine serum (FBS), antibiotic solutions and other cell culture reagents from Invitrogen/GIBCO (Carlsbad, CA); (ii) Pertussis Toxin, reagents for electrophoresis and other highly pure chemicals from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Human/rat CRF was purchased from Bachem (Torrance, CA). Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), and the following specific inhibitors were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA): Src inhibitor PP2; EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478; PKA inhibitor H89; PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide I, BIM; PI3K inhibitors wortmannin and LY294002; MMP inhibitor GM6001, and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Set III. BB-94 (batimastat) was obtained from British Biotechnology Ltd (Oxford, UK). Antibodies for Western blots were obtained from the following sources: (i) phospho-p44/42 MAP kinase (Thr202/Tyr204), total ERK1/2, total EGFR and phospho-c-Src (Tyr416) from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA); (ii) total ERK2, total c-Src and total Akt from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); (iii) phospho-EGFR (Tyr1068), phospho-EGFR (Tyr1173) and phospho-EGFR (Tyr845) from Biosource-Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); (iv) phospho-Akt (Ser473) from Biosource International (Camarillo, CA); (v) phospho-PYK2 (Tyr402) from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA); (vi) polyclonal anti-human HB-EGF antibody from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); (vii) secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase from Zymed Laboratories (San Francisco, CA).

The HA-epitope tagging human CRF1R (HA-CRF1R), the HA-CRF1R-Δ386 mutant, and the β-arrestin-2 constructs were previously described (22–24). Plasmid pRK5 encoding the carboxyl terminus of βARK that contains its βγ-binding domain (ct-βARK) was kindly provided by Dr. W. Koch (Center for Translational Medicine, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA), which is a scavenger for G protein βγ subunits (25). The expression vector pCEFL-SrcYF-KM, which contains the inactive form of SrcYF, SrcYF-KM (dominant-negative, dn-Src), was kindly provided by Dr. Silvio Gutkind (Department of Pharmacology, UCSD, La Jolla, CA) (26). Plasmid pUSEamp encoding dominant-negative Akt-K179M (dn-Akt) was from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY).

COS-7 cells (from the American Type Culture Collection) were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air, 5% CO2, in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 units/ml penicillin (COS-7 growth medium). Transient transfections were performed using LipofectAMINE (Life Technologies: Gaithersburg, MD) as described previously (27). Cells were seeded at 8 × 105 cells/10-cm dish in COS-7 medium and cultured for 3 days before transfection. COS-7 cells were transfected in 5 ml/dish OptiMEM containing 10 μg/ml LipofectAMINE with empty vector, pcDNA3 encoding the HA-CRF1R or the HA-CRF1R-Δ386 mutant. In certain experiments, cells were co-transfected with plasmids containing: HA-CRF1R and mock (empty vector); HA-CRF1R and ct-βARK; HA-CRF1R and dn-Src; HA-CRF1R and dn-Akt, or HA-CRF1R and full-length β-arrestin-2. After replacing the transfection medium with fresh growth medium, transfected COS-7 cells were cultured for 1 day. Subsequently, cells were re-seeded in 6-well plates and cultured for an additional day prior to the experiment.

The protocols for measuring total and phosphorylated ERK1/2, c-Src, PYK2, Akt, and EGFR have been previously published (28, 29). After cells were cultured to 60–70% confluence, they were serum-deprived for 24 h. On the day of the experiment, cells were treated with the indicated ligands and inhibitors. No significant changes in the basal level of ERK1/2 or Akt phosphorylation were observed in cells pretreated with inhibitors, except for BIM, which showed a small increase in ERK1/2 activation (Supplementary Figure S1). After treatment, cells were placed on ice, the media was aspirated, and the cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in 100 μl of Laemmli sample buffer 1X. The lysates were briefly sonicated, heated at 95°C for 5 min, and centrifuged for 5 min at 14,000 rpm. Resulting supernatants were loaded in separate lanes of a 10% SDS-PAGE gels and electrophoresed. Next, Western transfer on to PDVF membranes was completed. The Western blots were then probed with specific antibodies targeting phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms of ERK1/2, c-Src, PYK2, Akt, and EGFR for primary immunodetection. After blots were probed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, protein bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence ECL reagent (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ or Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) and scanned using the GS-800 Calibrated Imaging Densitometer (Bio-Rad). The labeled bands were quantified using the Quantity One 4.6.3 software program (Bio-Rad).

COS-7 cells transfected with HA-CRF1R were grown in 10-cm dishes and serum-deprived for 24 h before treatment with 100 nM CRF for 10 min at 37°C. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in Nonidet P-40 solubilization buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM Orthovanadate, 1 mM NaF, 1% Nonidet P-40, 10% Glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, pH 7.4, containing protease inhibitors). After immunoprecipitation of HA-CRF1Rs with anti-HA monoclonal antibody (HA.11; Covance, San Diego, CA) and protein A/G PLUS-Agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), the proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, Western blotted, and probed with anti-EGFR polyclonal or anti-HA monoclonal antibodies, followed by a horseradish peroxidase conjugate to identify co-immunoprecipitated proteins. Blots were also stripped with stripping buffer (100 nM Glycine-HCl, pH 2.7) and reprobed with anti-c-Src polyclonal antibody. Western blot detection of co-immunoprecipitated Src was carried out as described above. Blots were visualized and quantified, as indicated above.

Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Analyses of variances (ANOVAs) across experimental groups were performed using PRISM™, Version 8.0 for macOS (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). If the one-way ANOVA was statistically significant, planned post-hoc analyses were performed using Dunnet or Bonferroni's multiple comparison tests to determine individual group differences.

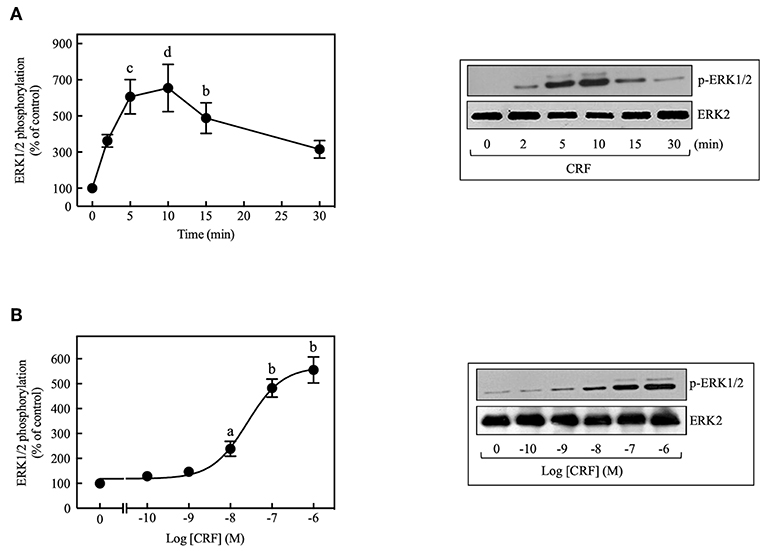

CRF treatment (100 nM) of COS-7 cells transiently transfected with HA-CRF1R caused transient phosphorylation of ERK1/2 that reached a peak at 5–10 min and declined thereafter toward the basal level over the next 30 min (Figure 1A). CRF (100 nM) also caused time-dependent phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in CRF1R-expressing HEK293 and CHO-K1 cells (data not shown), but the rate and magnitude of CRF-induced ERK1/2 activation was considerably less in these cell lines compared to COS-7 cells. In contrast, CRF1Rs expressed in SK-N-MC neuroblastoma cells (4) failed to signal via the ERK1/2 cascade while fibroblast growth factor induced strong ERK1/2 phosphorylation in this cell line (Supplementary Figure S2). Therefore, all subsequent experiments studying ERK1/2 signaling were performed in COS-7 cells transfected with HA-CRF1R cDNA. CRF-induced ERK1/2 activation was concentration-dependent, with a significant increase at 10 nM CRF (~2.4-fold increase over control) and maximal effect over the 0.1–1 μM range (~5.2-fold increase over control, Figure 1B). The EC50 was 25 nM and the maximum occurred at 100 nM for the CRF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Figure 1. CRF induces ERK1/2 phosphorylation in COS-7 expressing CRF1Rs. (A) COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1Rs were treated with 100 nM CRF for the indicated times. (B) COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1Rs were exposed to the indicated concentration of CRF for 5 min. Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-p-ERK1/2 Thr202/Tyr204, as described in Materials and Methods. ERK1/2 phosphorylation was quantitated by densitometry, and mean values were plotted from three to five independent experiments. Vertical lines represent the S.E.M. Representative immunoblots are presented. Western blots were also probed for total ERK, showing equal loading. (A) bp < 0.01, cp < 0.001, dp < 0.0001 vs. 0 min. (B) ap < 0.05, bp < 0.01 vs. 0 M.

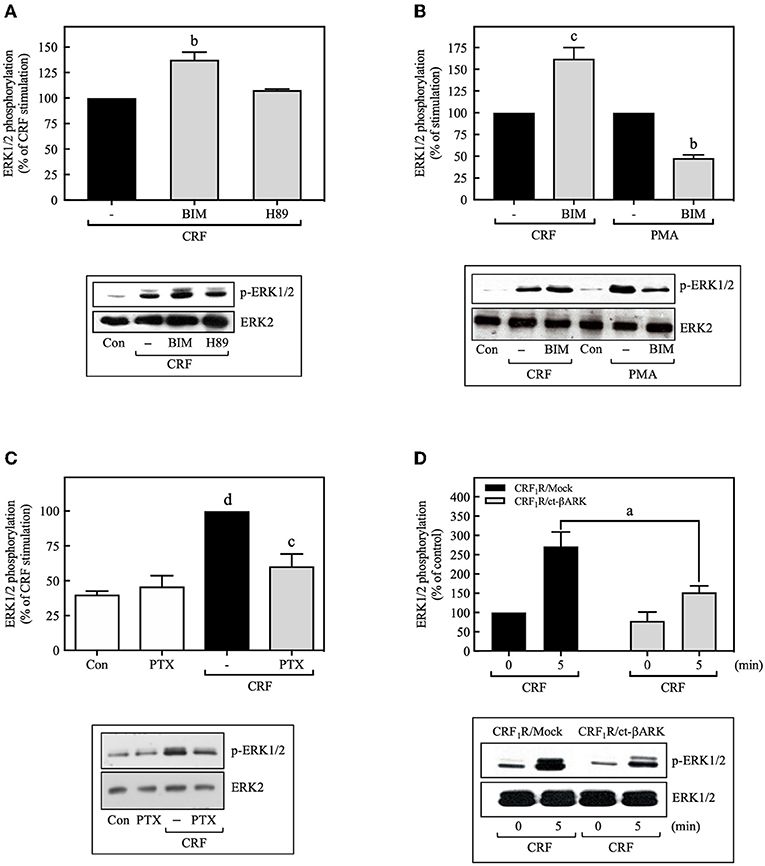

Most of the known actions of CRF1Rs are mediated through the Gs/PKA signaling cascade, but some of the physiological actions of CRF are also known to occur through activation of Gq or Gi proteins (30). To determine the contributions of Gs/PKA-dependent mechanisms to MAP kinase activation, COS-7 cells were pretreated with the PKA inhibitor H89 (500 nM) for 30 min prior to stimulation with CRF (100 nM). As shown in Figure 2A, the PKA inhibitor failed to inhibit CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Furthermore, the magnitude of CRF1R-mediated activation of ERK1/2 was similar in COS-7 cells pretreated for 30 min with the highly selective PKA inhibitor Rp-cAMP (0–100 μM) or vehicle (Supplementary Figure S3). We next explored the involvement of Gq/PKC in CRF1R ERK signaling. A 30-min pretreatment of COS-7 cells with the PKC inhibitor BIM (1 μM), increased (~1.6-fold increase over CRF stimulation) rather than decreased CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 activation (Figure 2B). In contrast, BIM pretreatment inhibited ERK1/2 phosphorylation resulting from PMA-induced PKC activation (Figure 2B). Thus, our data suggest that neither Gs/PKA nor Gq/PKC are required for the CRF1R-mediated ERK1/2 signaling in COS-7 cells.

Figure 2. CRF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation is dependent on Gi protein. COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1Rs were pretreated with 0.5 μM H89 (A) or 1 μM BIM (bisindolylmaleimide I) (A,B) for 30 min, before stimulation with 100 nM CRF (A,B) for 5 min or 100 nM PMA (B) for 15 min. (C) COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1Rs were pretreated with 100 ng/ml PTX for 15 h, before stimulation with 100 nM CRF for 5 min. (D) COS-7 cells co-transfected with a plasmid pRK5 encoding the carboxyl terminus of βARK that contains its βγ-binding domain (ct-βARK) or an empty control vector (Mock) and the pcDNA3-HA-CRF1R expression vector were stimulated with 100 nM CRF for 5 min. Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-p-ERK1/2 Thr202/Tyr204, as described in Materials and Methods. ERK1/2 phosphorylation was quantitated by densitometry, and mean values were plotted from five independent experiments. Vertical lines represent the S.E.M. Western blots were also probed for total ERK showing equal loading. (A) bp < 0.01 vs. CRF (–). (B) cp < 0.001 vs. CRF (–); bp < 0.01 vs. PMA (–). (C) dp < 0.0001 vs. Con or PTX; cp < 0.001 vs. CRF (–). (D) ap < 0.05 vs. CRF1R/Mock (5 min).

On the other hand, the release of Gβγ subunits during GPCR coupling to G protein, particularly through Gi, has an important role in downstream signaling in the ERK1/2 cascade (31, 32). Thus, we examined the role of Gi and Gβγ in CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 activation by two different experimental approaches: treatment with the Gi protein inhibitor pertussis toxin (PTX) and by co-transfecting COS-7 cells with plasmids encoding the carboxyl terminus of βARK containing its βγ-binding domain (ct-βARK) (Supplementary Figure S4), which sequesters βγ, and the CRF1R. COS-7 cells expressing CRF1Rs pretreated with 100 ng/ml PTX showed a marked reduction in CRF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Figure 2C), suggesting the coupling of CRF1R to Gi to mediate ERK activation. Moreover, overexpressing ct-βARK in COS-7 cells co-expressing CRF1Rs significantly reduced CRF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation by ~40% (Figure 2D). Thus, our data implicate Gβγ subunits from PTX-sensitive heterotrimeric G proteins in CRF1R-mediated activation of ERK1/2.

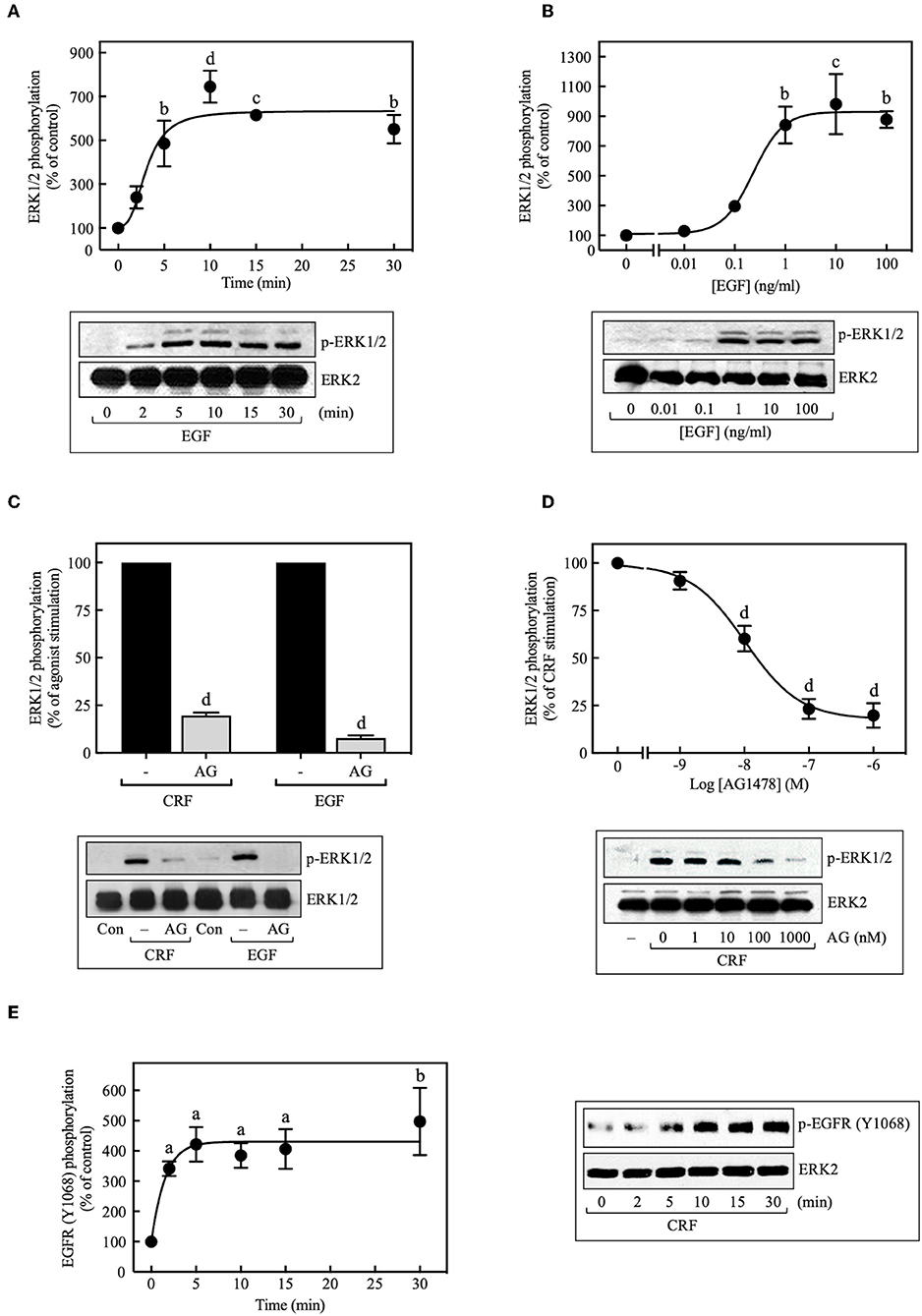

Because transactivation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), especially the EGFR, is often an important mechanism used by GPCRs to activate ERK1/2 (33, 34), we investigated the role of EGFR transactivation in CRF1R-mediated ERK signaling. In COS-7 cells transiently transfected with HA-CRF1R, EGF stimulation of the endogenous EGFRs caused ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a time-dependent manner, reaching a maximum effect after 5 min of stimulation, which persisted for at least 30 min (~6.0-fold increase over time 0, Figure 3A). ERK1/2 phosphorylation was also increased by EGF (0–100 ng/ml) in a concentration-dependent manner (EC50 = 0.23 ng/ml, Figure 3B). Thus, these results are consistent with the well-established role of EGFR in ERK1/2 signaling (35).

Figure 3. Involvement of EGFR transactivation in CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation. COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1Rs were treated with 10 ng/ml EGF for the indicated times (A) or exposed to the indicated concentration (B) of EGF for 10 min. COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1Rs were pretreated with 100 nM (C) or the indicated concentrations of AG1478 (AG) (D) for 30 min, before stimulation with 100 nM CRF for 5 min (C,D) or 10 ng/ml EGF for 10 min (C). (E) Effect of 100 nM CRF on EGFR phosphorylation at Tyr1068. Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-p-ERK1/2 Thr202/Tyr204 (A–D) or anti-p-EGFR Tyr1068 (E), as described in Materials and Methods. ERK1/2 and EGFR phosphorylation were quantitated by densitometry, and mean values were plotted from three to five independent experiments. Vertical lines represent the S.E.M. Western blots were also probed for total ERK, showing equal loading. (A) bp < 0.01, cp < 0.001, dp < 0.0001 vs. 0 min. (B) bp < 0.01, cp < 0.001 vs. 0 ng/ml. (C) dp < 0.0001 vs. CRF (–); dp < 0.0001 vs. EGF (–). (D) dp < 0.0001 vs. 0 M. (E) ap < 0.05, bp < 0.01 vs. 0 min.

When COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1R were pretreated with the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478 (100 nM, 30 min), a significant inhibition (~80%) of CRF-induced maximal ERK1/2 phosphorylation was observed (Figure 3C). A concentration-dependent inhibition was observed with AG1478 concentrations of 0–1,000 nM with an IC50 of 10 nM (Figure 3D). Importantly, phosphorylation of the EGFR at Tyr1068 was detected with Western blots in COS-7 cells beginning at 2 min and becoming maximal at 5–10 min of CRF exposure (100 nM) (Figure 3E). Tyr1173 of the EGFR was phosphorylated in parallel with Tyr1068 in COS-7 cells stimulated with CRF (Supplementary Figure S5). Together, these results indicate that CRF-activated CRF1R triggers phosphorylation of two critical amino acids located within the autophosphorylation loop that are required for EGFR activation (36, 37). Thus, CRF1R signaling rapidly transactivates the EGFR, in agreement with a study reporting that Ucn1 stimulated EGFR transactivation in CRF1R-expressing HEK293 cells (5).

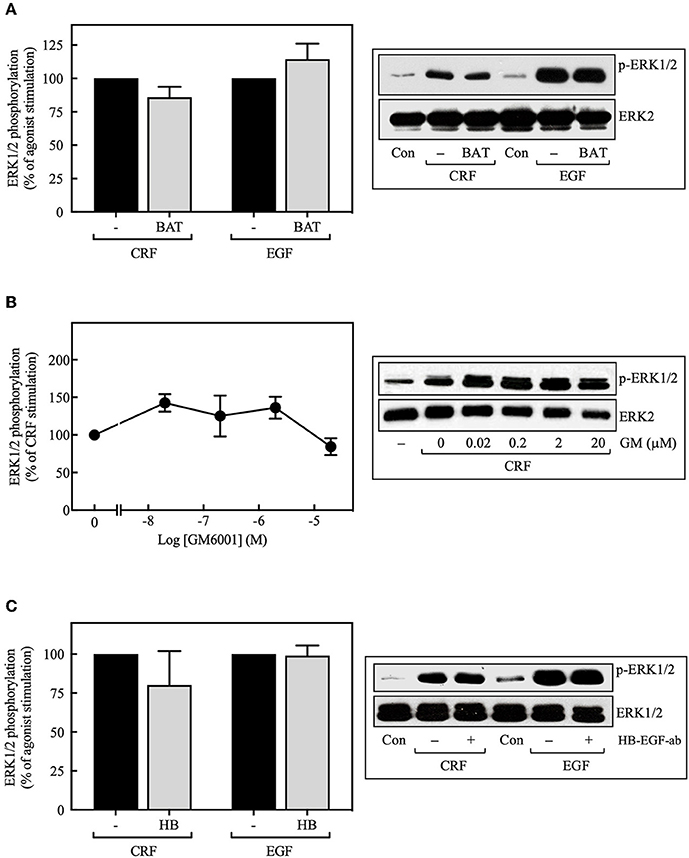

MMPs catalyze the release of extracellular heparin-binding EGF (HB-EGF) ligand, which, in turn, binds to and activates the EGFR, thereby stimulating ERK1/2 phosphorylation (38–40). Although this process represents a significant mechanism for GPCR-mediated EGFR transactivation, we found that basal and CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in transfected COS-7 cells was not altered by inhibiting the formation of the ligand HB-EGF with broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors batimastat BB-94 (5 μM) (Figure 4A) or GM6001 (0–20 μM) (Figure 4B). Similarly, blocking HB-EGF binding to the EGFR with an HB-EGF antibody (5 μg/ml) also failed to inhibit CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Figure 4C). In agreement with previous reports (39, 41), GM6001 pretreatment significantly attenuated ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by PMA but not EGF (Supplementary Figure S6). Altogether, these results exclude a role of MMP in CRF-induced transactivation of the EGFR and subsequent phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in COS-7 cells.

Figure 4. Effect of the MMP inhibitors and the HB-EGF antibody on CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation. COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1Rs were pretreated with 5 μM batimastat (BAT) (A), the indicated concentrations of GM6001 (GM) (B) or 5 μg/ml HB-EGF antibody (HB) (C) for 30 min, before stimulation with 100 nM CRF for 5 min (A–C) or 10 ng/ml EGF for 10 min (A,C). Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-p-ERK1/2 Thr202/Tyr204, as described in Materials and Methods. ERK1/2 phosphorylation was quantitated by densitometry, and mean values were plotted from three to five independent experiments. Vertical lines represent the S.E.M. Western blots were also probed for total ERK showing equal loading.

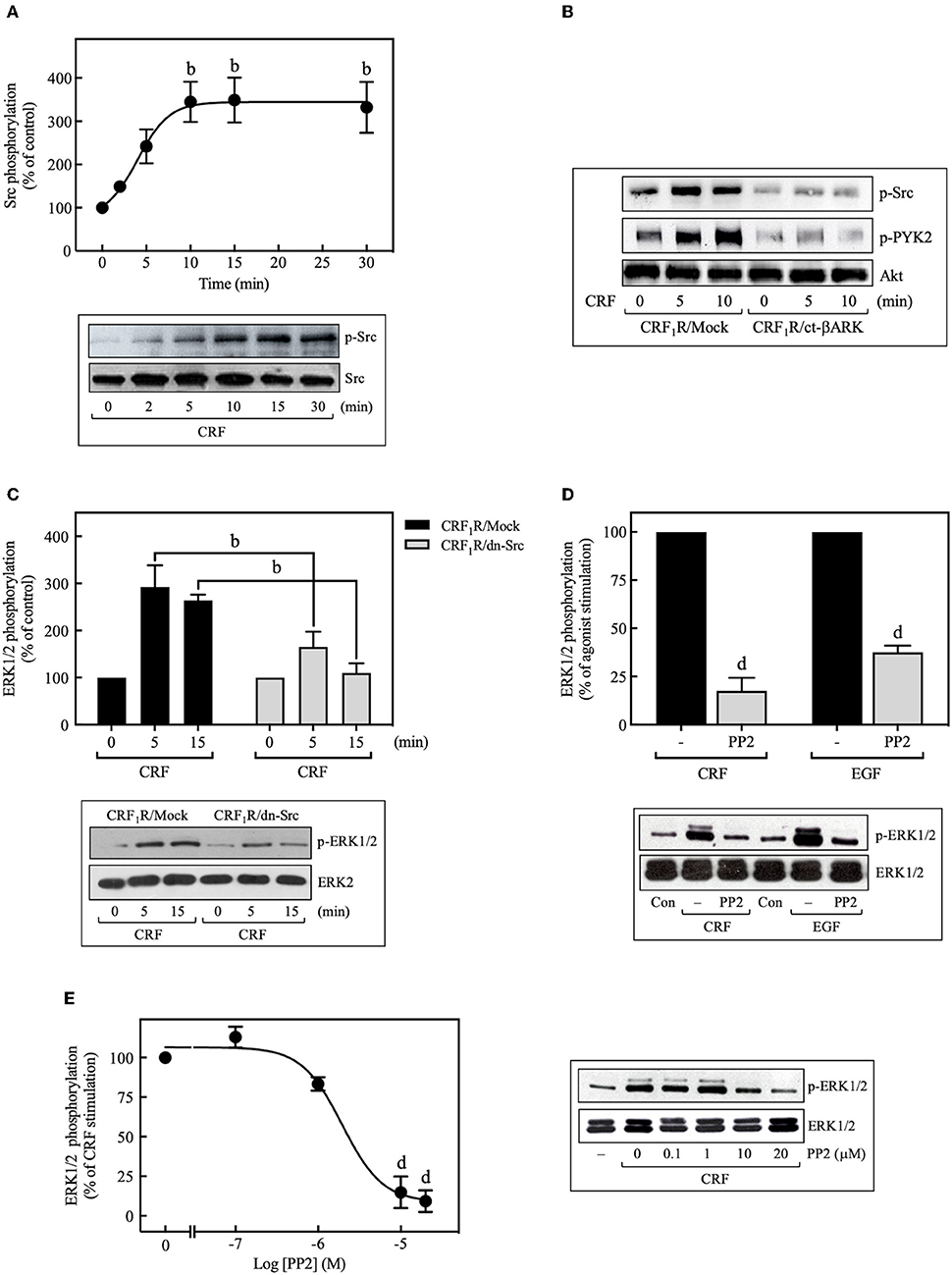

We then investigated the role of Src kinase, which can serve as an important upstream regulator of GPCR signaling via the ERK1/2 cascade (42, 43). Importantly, 100 nM CRF caused marked phosphorylation of Src at Tyr416, which is a requirement for Src activation (44), reaching a maximum at 10 min (~3.5-fold increase over time 0), and persisting for more than 30 min (Figure 5A). This activation was dependent on Gβγ release since ct-βARK expression reduced the CRF-induced Src phosphorylation (Figure 5B), and as expected, CRF-induced Src phosphorylation was prevented by pretreatment with the selective Src family kinase inhibitor PP2 (Figure 9B). To further evaluate the role of Src in CRF1R ERK1/2 signaling, COS-7 cells were co-transfected with the CRF1R and a dn-Src. Overexpression of inactive Src prevented ERK1/2 activation by CRF (Figure 5C). Other experiments demonstrated that PP2 pretreatment abolished CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Figure 5D), in a concentration-dependent manner (0–20 μM, IC50 = 2 μM) (Figure 5E). These findings support our hypothesis that Src plays a central role in CRF1R ERK1/2 signaling.

Figure 5. Role of Src tyrosine kinase in CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation. (A) COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1Rs were stimulated with 100 nM CRF for the indicated times. (B) COS-7 cells co-transfected with a plasmid pRK5 encoding the carboxyl terminus of βARK that contains its βγ-binding domain (ct-βARK) or an empty control vector (Mock) and the pcDNA3-HA-CRF1R expression vector were stimulated with 100 nM CRF for 5 or 10 min. (C) COS-7 cells co-transfected with a dominant-negative SrcYF-KM (dn-Src) expression vector or an empty control vector (Mock) and the pcDNA3-HA-CRF1R expression vector were stimulated with 100 nM CRF for 5 or 15 min. Cells were pretreated with 10 μM or the indicated concentrations of PP2 for 30 min before stimulation with 100 nM CRF (5 min) (D,E) or 10 ng/ml EGF (10 min) (D). Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-p-Src Tyr416 (A,B) or anti-p-ERK1/2 Thr202/Tyr204 (C–E), as described in Materials and Methods. Src, PYK2, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation were quantitated by densitometry, and mean values were plotted from three to five independent experiments. Vertical lines represent the S.E.M. Western blots were also probed for total Src, total Akt, and total ERK showing equal loading. (A) bp < 0.01 vs. 0 min. (C) bp < 0.01 vs. CRF1R/Mock (5 or 15 min). (D) dp < 0.0001 vs. CRF (–), dp < 0.0001 vs. EGF (–). (E) dp < 0.0001 vs. 0 M.

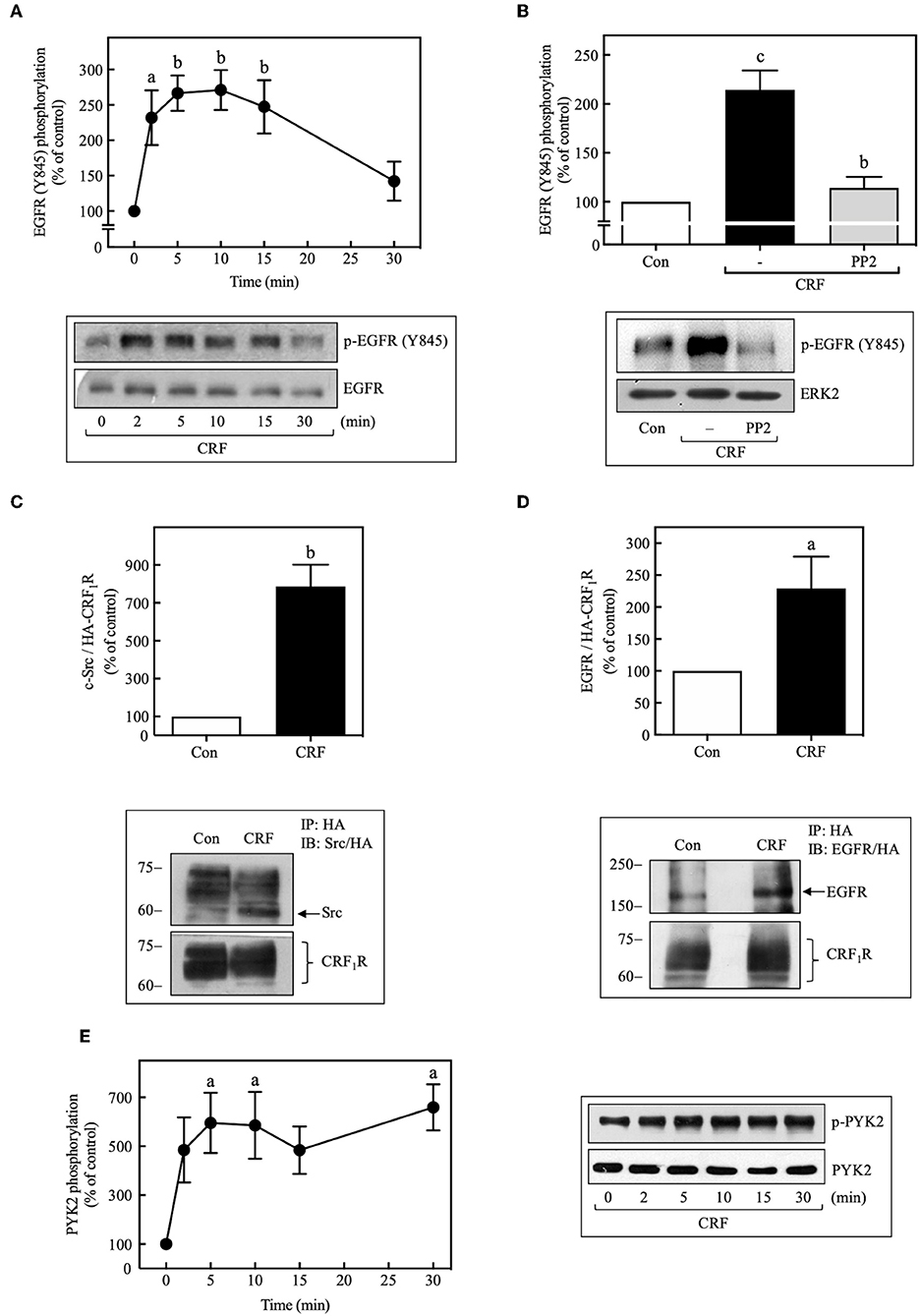

We next determined if CRF-stimulated Src activation is required for CRF1R-induced transactivation of EGFRs. In this context, previous research has established that Src can activate EGFR signaling by phosphorylating Tyr845 of the EGFR protein (45, 46). As shown in Figure 6A, we found that 100 nM CRF stimulated in a time-dependent manner marked phosphorylation of EGFR at Tyr845 beginning at 2 min and becoming maximal at 10 min. This effect was blocked by pretreatment of the cells with PP2 (Figure 6B). In a recent study by Perkovska et al. (47), it was shown that V1b vasopressin receptor interacts with Src at basal state, suggesting the formation of a GPCR/Src complex that facilitates MAP kinase activation. To evaluate if a CRF1R/Src complex exists under basal conditions, we analyzed CRF1R immunoprecipitates for the presence of co-precipitated Src under basal and CRF-stimulated conditions. As shown in Figure 6C, 100 nM CRF induced a robust interaction between the CRF1R and Src after 10 min stimulation (~8.0-fold increase over control). Interestingly, it was also observed that under the same immunoprecipitation conditions, the EGFR is also present in the CRF1R/co-precipitated complex, even in the absence of CRF stimulation (Figure 6D). After stimulation with 100 nM CRF for 10 min, we observed a significant increase in the CRF1R/EGFR interaction (~2.5-fold increase over control). These observations suggest that CRF promotes the formation of a multiprotein complex that would allow rapid EGFR phosphorylation at Tyr845 by Src, present in this complex.

Figure 6. CRF mediates EGFR phosphorylation at Tyr845 and activation of PYK2. COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1Rs were stimulated with 100 nM CRF for the indicated times (A,E) or pretreated with 10 μM PP2 for 30 min before stimulation with 100 nM CRF for 5 min (B). Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-p-EGFR Tyr845 (A,B) or anti-p-PYK2 Tyr402 (E), as described in Materials and Methods. EGFR and ERK1/2 phosphorylation were quantitated by densitometry, and mean values were plotted from three to five independent experiments. Vertical lines represent the S.E.M. Western blots were also probed for total EGFR, ERK, or PYK2 showing equal loading. (A) ap < 0.05, bp < 0.01 vs. 0 min. (B) cp < 0.001 vs. Con, bp < 0.01 vs. CRF (–). (E) ap < 0.05 vs. 0 min. (D) COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1Rs were stimulated with 100 nM CRF for 10 min. Total cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody and immunoblotted with anti-EGFR antibody or anti-HA antibody. (C) Blots were also stripped and reprobed with anti-Src polyclonal antibody. Src and EGFR were quantitated by densitometry, and mean values were plotted from three independent experiments. Vertical lines represent the S.E.M. (C) bp < 0.01 vs. Con. (D) ap < 0.05 vs. Con.

It has been shown that, in parallel to Src activation by many GPCRs, the proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2, PYK2, is also phosphorylated and activated, and in association with Src is required for the subsequent transactivation of EGFR (44, 48). Therefore, we decided to assess whether activation of CRF1R leads to PYK2 phosphorylation in COS-7 cells. As shown in Figure 6E, 100 nM CRF caused rapid phosphorylation of PYK2 in a time-dependent manner (0–30 min), reaching a maximum effect at 5 min and persisting for at least 30 min of stimulation. Interestingly, and as expected, CRF-mediated PYK2 phosphorylation was also dependent on Gβγ release (Figure 5B).

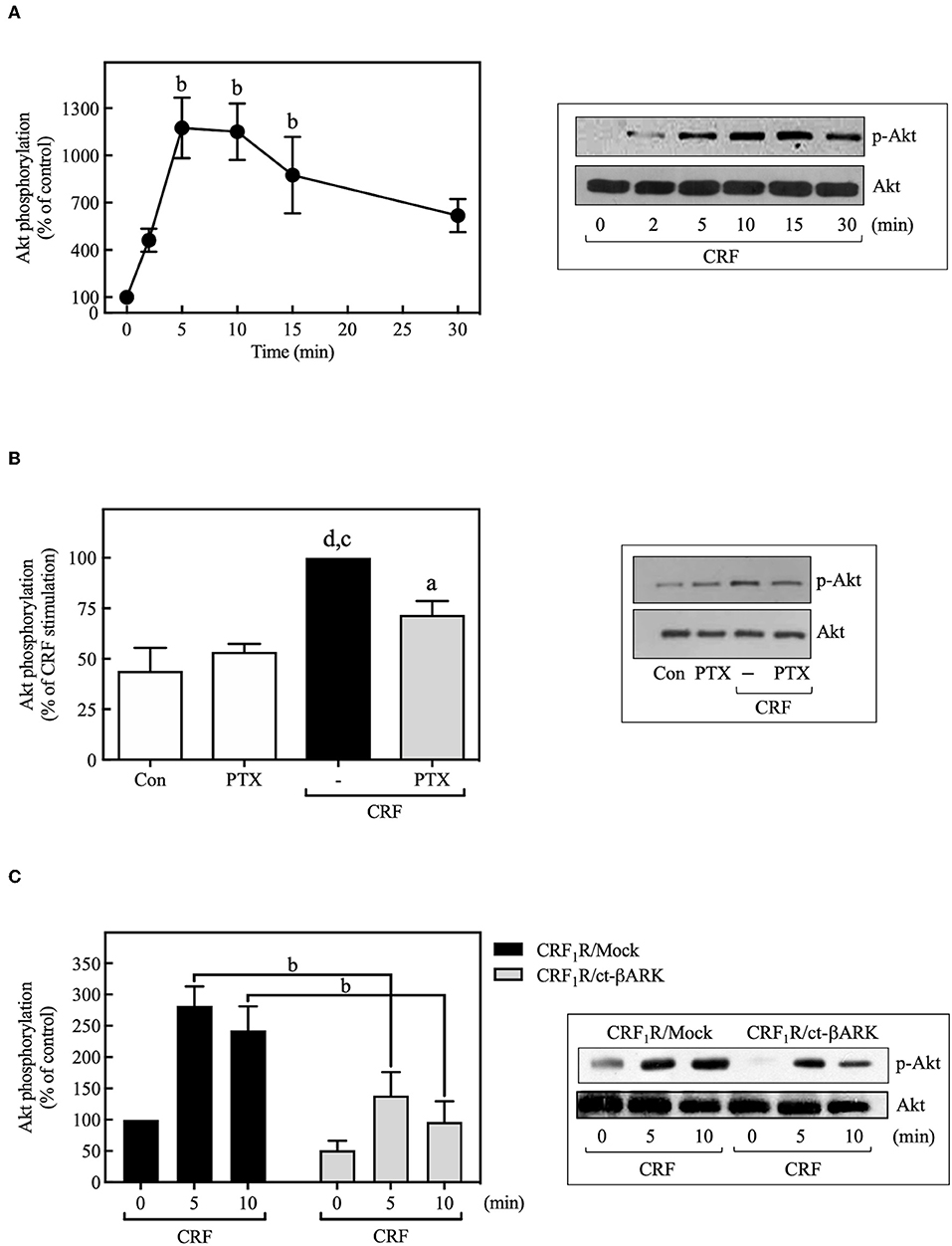

PI3Ks can mediate important biological actions of GPCRs, including cell proliferation or survival, by serving as an upstream regulator of Akt and ERK cascades (49, 50). As shown in Figure 7A, 100 nM CRF caused rapid phosphorylation of Akt, an effect that was decreased by PTX pretreatment (Figure 7B) or ct-βARK overexpression (Figure 7C), similar to the previously observed effect on the CRF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation, suggesting the participation of Gi protein and Gβγ subunits in this process. It is important to note that none of the observed effects of PTX and ct-βARK on CRF actions were present on EGF-stimulated ERK1/2 and Akt phosphorylation (Supplementary Figure S7).

Figure 7. CRF mediates Akt activation. (A) COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1Rs were stimulated with 100 nM CRF for the indicated times. (B) COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1Rs were pretreated with 100 ng/ml PTX for 15 h before stimulation with 100 nM CRF for 5 min. (C) COS-7 cells co-transfected with a plasmid pRK5 encoding the carboxyl terminus of βARK that contains its βγ-binding domain (ct-βARK) or an empty control vector (Mock) and the pcDNA3-HA-CRF1R expression vector were stimulated with 100 nM CRF for the indicated times. Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-p-Akt Ser473, as described in Materials and Methods. Akt phosphorylation was quantitated by densitometry, and mean values were plotted from three to five independent experiments. Vertical lines represent the S.E.M. Western blots were also probed for total Akt showing equal loading. (A) bp < 0.01 vs. 0 min. (B) dp < 0.0001 vs. Con, cp < 0.001 vs. PTX; ap < 0.05 vs. CRF (–). (C) bp < 0.01 vs. CRF1R/Mock (5 and 10 min).

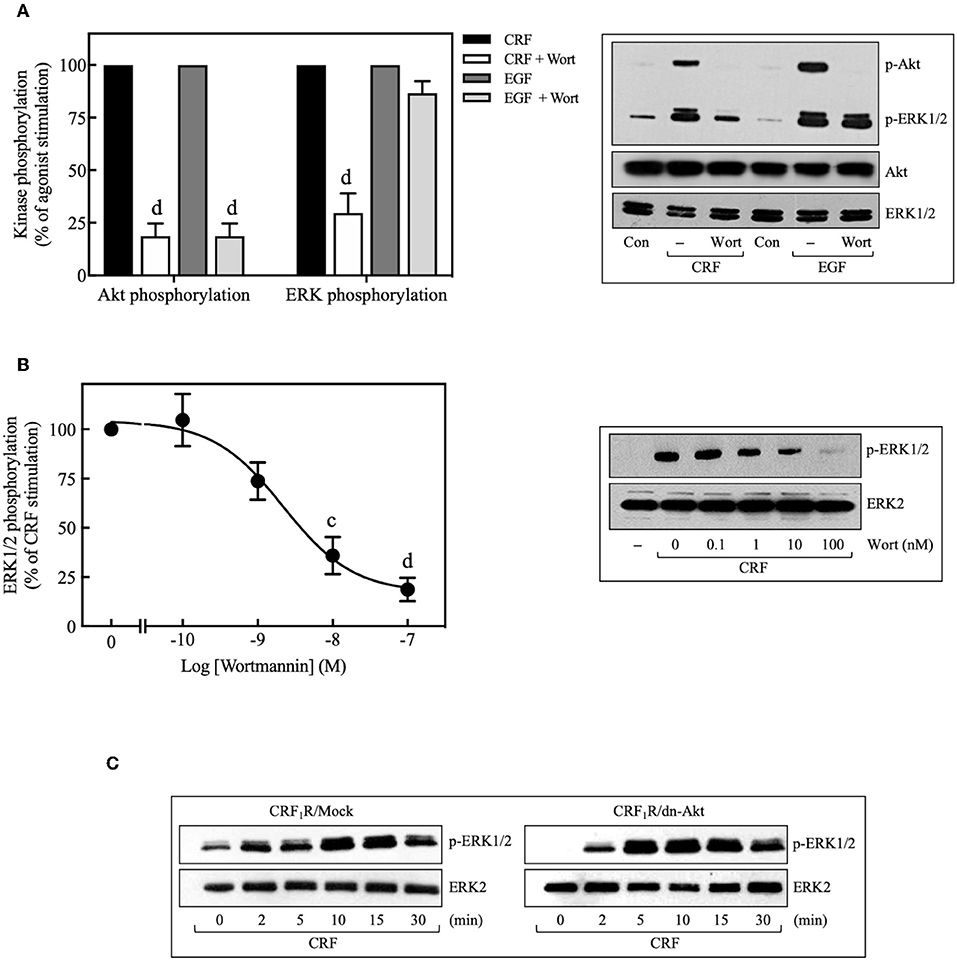

Pretreatment with selective PI3K inhibitors, wortmannin (100 nM) (Figure 8A), or LY294002 (10 μM) (Figure 9C) abolished CRF1R-mediated Akt signaling activation. Similarly, inhibition of PI3K by 100 nM wortmannin abolished the stimulatory action of EGF on Akt (Figure 8A), thereby demonstrating that the PI3K pathway is required for both CRF- and EGF-induced Akt phosphorylation. Considering that an upstream PI3K mechanism can also regulate CRF1R and CRF2R signaling via the ERK1/2 cascade in A7r5, CATH.a, and transfected CHO cells (9, 12), we investigated the potential role of PI3K in the activation of ERK1/2 by HA-CRF1Rs expressed in COS-7 cells. In this context, activation of RTKs, such as the EGFRs, has been shown to recruit PI3K and activate ERK1/2 (50–53). However, contradictory data on PI3K involvement in EGFR-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation have been reported (54–56). In this regard, to find out if EGF-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation observed in COS-7 cells is depending on PI3K activation, we analyze the effect of 100 nM wortmannin on the EGF ERK1/2 activation. As shown in Figure 8A, pretreatment with wortmannin was unable to inhibit the effect of EGF, suggesting that PI3K does not participate in this mechanism. In contrast, pretreatment with wortmannin abolished CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Figure 8A) in a concentration-dependent manner (0–100 nM), confirming an intermediary role for PI3K in CRF1R ERK signaling (Figure 8B). To examine the contribution of CRF-mediated activation of Akt to the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, we evaluated the effect of the dn-Akt mutant. As shown in Figure 8C, overexpression of dn-Akt had no significant effect on ERK1/2 activation after stimulation with CRF (Figure 8C), suggesting that Akt does not participate in the activation of ERK1/2 by CRF. Because in the present work we do not show evidence about impairment of kinase activity of the dn-Akt, it will be necessary the use of other approaches, such as genetic tools or inhibitors, to provide more evidence regarding the possible no effect of Akt on the ERK 1/2 pathway. Because in the present work we do not show evidence about impairment of kinase activity of the dn-Akt, it will be necessary the use of other approaches, such as genetic tools or inhibitors, to provide more evidence regarding the possible Akt lack of effect on ERK 1/2 pathway. Consequently, our results suggest that PI3K can regulate the transduction of CRF1R signals through the ERK cascade, possibly independently of Akt.

Figure 8. Involvement of the PI3K pathway in CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation. (A,B) COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1Rs were pretreated with 100 nM or the indicated concentrations of wortmannin (Wort) for 30 min before stimulation with 100 nM CRF for 5 min (A,B) or 10 ng/ml EGF for 10 min (A). (C) COS-7 cells co-transfected with a dominant-negative Akt (K179M) expression vector (dn-Akt) or an empty control vector (Mock) and the pcDNA3-HA-CRF1R expression vector were stimulated with 100 nM CRF for the indicated times. Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-p-Akt Ser473 (A) or anti-p-ERK1/2 Thr202/Tyr204 (A–C), as described in Materials and Methods. Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation were quantitated by densitometry, and mean values were plotted from three to five independent experiments. Vertical lines represent the S.E.M. Western blots were also probed for total Akt or ERK showing equal loading. (A) dp < 0.0001 vs. CRF (p-Akt), dp < 0.0001 vs. EGF (p-Akt); dp < 0.0001 vs. CRF (p-ERK), (B) cp < 0.001, dp < 0.0001 vs. 0 M.

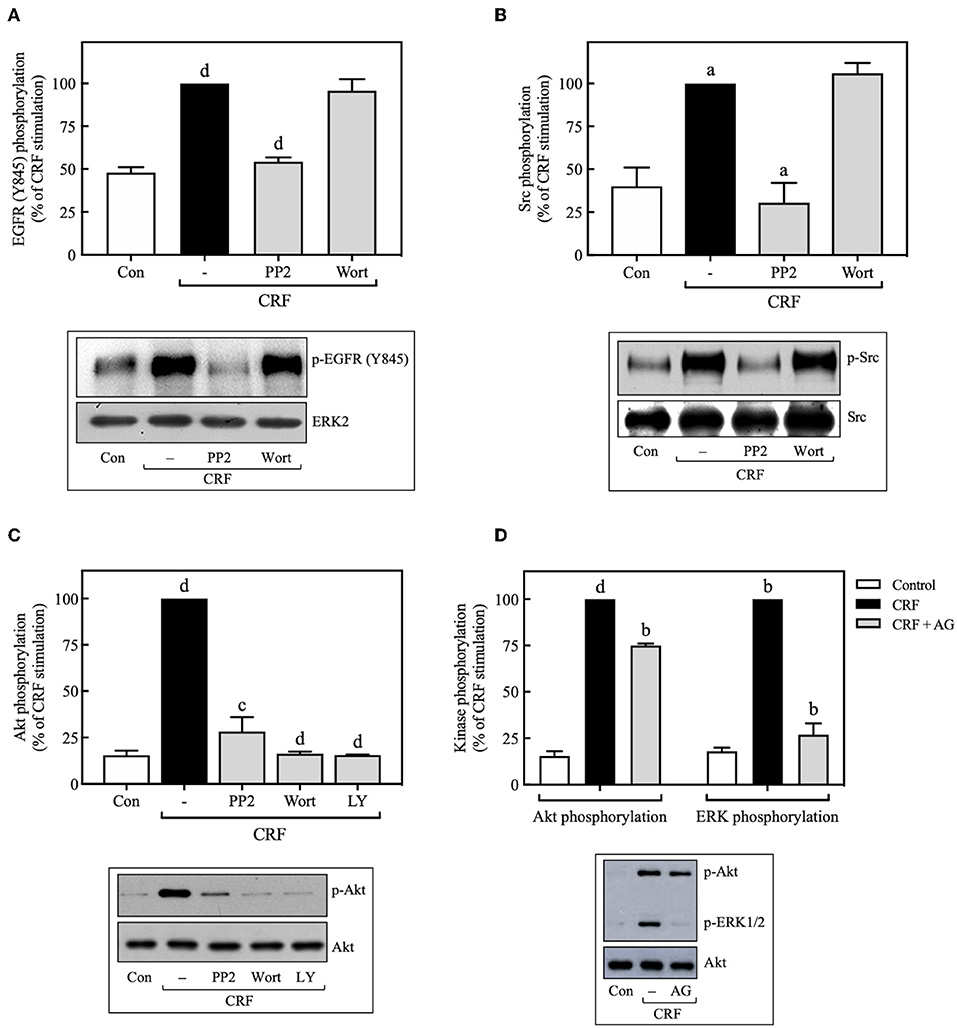

Figure 9. Src is an upstream regulator of EGFR and PI3K. COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1Rs were pretreated with 10 μM PP2, 100 nM wortmannin (Wort) (A–C) or 10 μM LY294002 (LY) (C) for 30 min, before stimulation with 100 nM CRF for 5 min. (D) Effect of 100 nM AG1478 (AG) on CRF- (100 nM, 5 min) induced ERK1/2 and Akt phosphorylation. Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-p-EGFR Tyr845 (A), anti-p-Src Tyr416 (B), anti-p-Akt Ser473 (C,D) or anti-p-ERK1/2 Thr202/Tyr204 (D), as described in Materials and Methods. EGFR, Src, Akt, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation were quantitated by densitometry, and mean values were plotted from three to five independent experiments. Vertical lines represent the S.E.M. Western blots were also probed for total ERK, Src or Akt showing equal loading. (A) dp < 0.0001 vs. Con; dp < 0.0001 vs. CRF (–). (B) ap < 0.05 vs. Con; ap < 0.05 CRF(–). (C) dp < 0.0001 vs. Con; cp < 0.001, dp < 0.0001 vs. CRF (–). (D) dp < 0.0001 vs. Con (p-Akt), bp < 0.01 vs. CRF (p-Akt); bp < 0.01 vs. Con (p-ERK), bp < 0.01 vs. CRF (p-ERK).

Since we found that CRF-induced EGFR transactivation mediates ERK1/2 phosphorylation through Src- and PI3K-dependent mechanisms, we next determined if CRF-induced PI3K activation occurs upstream or downstream of Src and EGFR. Wortmannin inhibition of PI3K had no effect on CRF-induced phosphorylation of EGFR at Tyr845 (Figure 9A), suggesting that PI3K acts downstream of Src and EGFR. Consistent with these results, we also observed that wortmannin pretreatment did not alter CRF-induced phosphorylation of Src at Tyr416 (Figure 9B). Therefore, CRF1R-stimulated transactivation of EGFR and phosphorylation of ERK1/2 mediated by Src was independent of PI3K. It has been reported that the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway can be activated at least by two independent mechanisms: (i) EGFR transactivation (57), and (ii) upstream Src activation (58, 59). We observed that CRF-induced Akt activation was completely inhibited by the Src inhibitor, PP2 (Figure 9C), suggesting that Src is an upstream regulator of PI3K and Akt. We next measured the effect of the specific EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, tyrphostin AG1478, on CRF-stimulated Akt phosphorylation. As observed in Figure 9D, while CRF-induced ERK1/2 activation was totally dependent on EGFR transactivation (Figure 9D), Akt phosphorylation was only partially dependent. Thus, we hypothesize that PI3K/Akt pathway signaling by CRF1R may involve two mechanisms: (i) a strong dependence on upstream Src activating PI3K and then Akt (Figure 9C); (ii) a weak dependence on EGFR transactivation (Figure 9D).

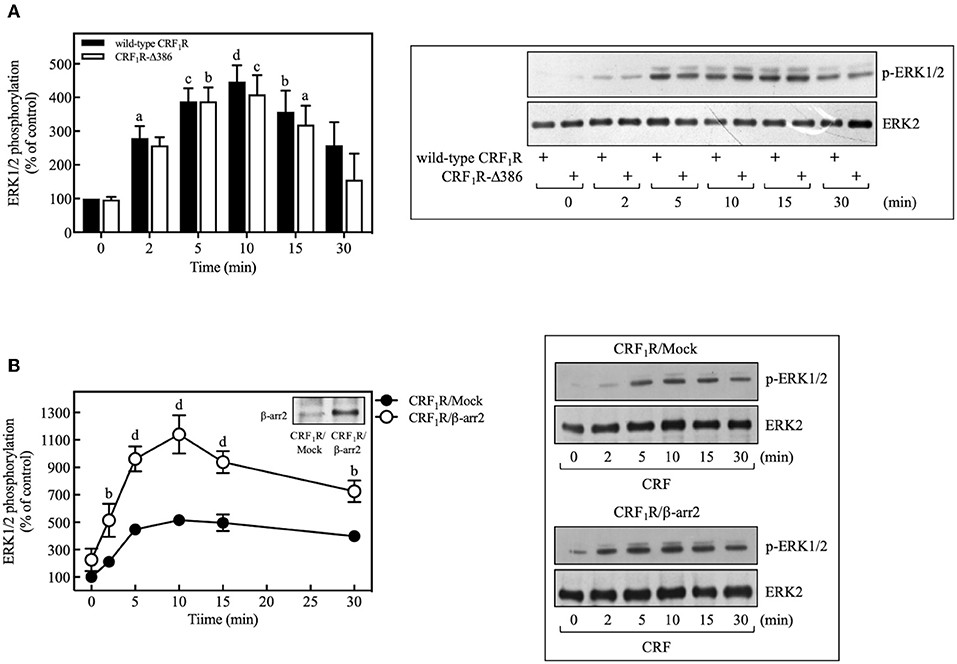

In recent years, it has been identified that β-arrestin proteins play an important role in mediating the actions of GPCRs, particularly those related to activation and regulation of Src and mitogenic pathways, in particular, the ERK1/2 signaling cascade (60). To determine the role of β-arrestins in the CRF-mediated ERK1/2 activation observed above, we used a phosphorylation-deficient mutant CRF1R, which also shows a diminished agonist-dependent β-arrestin-2 recruitment (24). As shown in Figure 10A, COS-7 cells transiently transfected with HA-CRF1R-Δ386 mutant showed a similar response in ERK1/2 phosphorylation compared to that observed with CRF1R. The apparent independence of CRF-mediated activation of ERK1/2 from β-arrestin-2 could be explained by the low β-arrestin expression level previously detected in COS-7 cells (61, 62). To assess this possibility, we evaluated the effect of β-arrestin-2 overexpression in COS-7 cells, since CRF1R activation has been shown to lead to selective recruitment of β-arrestin-2 in both HEK293 cells and neurons (24, 63). As observed in Figure 10B, cells co-expressing HA-CRF1R and β-arrestin-2 showed a significant increase in the CRF-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation, suggesting that β-arrestin involvement in CRF1R ERK1/2 signaling depends on its cellular expression levels.

Figure 10. β-arrestin does not participate in the CRF-stimulated ERK 1/2 phosphorylation in COS-7 cells. (A) COS-7 cells expressing HA-CRF1R (wild-type CRF1R) or HA-CRF1R-Δ386 mutant were stimulated with 100 nM CRF for the indicated times. (B) COS-7 cells co-transfected with a β-arrestin-2 (β-arr2) expression vector or an empty control vector (Mock) and the pcDNA3-HA-CRF1R expression vector were stimulated with 100 nM CRF for the indicated times. Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-p-ERK1/2 Thr202/Tyr204, as described in Materials and Methods. ERK1/2 phosphorylation was quantitated by densitometry, and mean values were plotted from three to five independent experiments. Vertical lines represent the S.E.M. Western blots were also probed for total ERK showing equal loading. (A) ap < 0.05, cp < 0.001, dp < 0.0001, bp < 0.01 vs. 0 min (CRF1R); bp < 0.01, cp < 0.001, ap < 0.05 vs. 0 min (CRF1R-Δ386). (B) bp < 0.01 vs. CRF1R (2 or 30 min); dp < 0.0001 vs. CRF1R (5, 10, or 15 min).

In the present study, we investigated the molecular mechanisms associated with the activation of ERK1/2 and Akt signaling cascades by the human CRF1R in COS-7 cells. Our data suggest that agonist-stimulated CRF1R promotes Gi activation and Gβγ release which, in turn, stimulate phosphorylation and activation of Src kinase. Once Src is active, it mediates ERK1/2 phosphorylation by at least two independent signaling mechanisms: (i) phosphorylation and transactivation of the EGFR, (ii) activation of PI3K. Interestingly, CRF1R-induced Akt phosphorylation also requires Src-mediated activation of PI3K as the main mechanism, but it is mostly independent of EGFR transactivation.

Defining the molecular mechanisms for ERK1/2 signaling by a GPCR has become a significant focus of signal transduction research due to the multifaceted pathways mediating signaling via the ERK1/2-MAP kinase cascade. A significant role of the ERK1/2-MAP kinase pathway has been recognized in the biological action of both CRF1R and CRF2R. ERK1/2 is widely distributed in the brain and is considered an essential regulator of the molecular processes involved in response to stress (6, 64). It is well-established that most GPCRs signal via ERK1/2-MAP kinase cascades through distinct Gi-, Gs-, and Gq-dependent signaling pathways. In the case of the CRF1R, it has been identified that the Gs/PKA pathway is importantly involved in the activation of MAP kinase cascades (12, 15, 18). In contrast, we found that pretreating CRF1R-expressing COS-7 cells with PKA inhibitors H89 or Rp-cAMP did not alter the ability of CRF to stimulate ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Although earlier research proposed that high cellular expression of the serine-threonine kinase B-Raf molecularly switches “upstream” ERK1/2 activation by Gs-coupled GPCRs to a PKA mechanism (14), pretreating fetal hippocampal cells with the PKA inhibitor H89 only produced a small reduction in CRF1R-mediated ERK phosphorylation despite very high hippocampal levels of B-Raf (18). Furthermore, H89 failed to inhibit CRF1R-mediated ERK signaling in brain-derived CATH.a, rat fetal microglial, locus coeruleus, and transfected CHO cells (8, 9, 12, 17). In fact, ERK activation by CRF1R in HEK293 cells was markedly decreased after the third intracellular loop's Ser301 was phosphorylated by PKA (65). Thus, a cAMP-dependent PKA → Rap1 → B-Raf mechanism does not always mediate ERK1/2 signaling by Gs-coupled receptors. EPAC, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor that is activated by intracellular cAMP, has been shown to regulate activation of Rap1 and ERK1/2 without the involvement of PKA (66). Gs-coupled CRF1R signaling can stimulate ERK1/2 phosphorylation by activating upstream EPAC2 independent of PKA in certain cell lines (17, 67). Interestingly, neither Epac nor PKA was found to mediate Akt cascade signaling by CRF2(b)R in HEK293 (21).

The versatility of the CRF1R to activate different signaling pathways has allowed its coupling to Gq proteins to be identified (4). Gq conveys a signal to activate PKC which then triggers MAP kinase cascades. Thus, it has been shown that Gq/PLC/PKC cascade signaling by CRF1R activated by Ucn1 contributes to phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in CRF1R-expressing myometrial, CHO, HEK293, and rat hippocampal cells (12, 13, 18). However, in pituitary AtT20 cells and CATH.a cells, PKC is not involved in Ucn1-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation (12). In our study, pretreatment with the PKC inhibitor, BIM, increased rather than reduced CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation, suggesting that PKC may negatively regulate CRF1R ERK1/2 signaling in COS-7 cells, although the specific mechanism for this effect remains to be determined.

The use of PTX in our study suggests the participation of Gi protein in the CRF-dependent activation of ERK and Akt pathways. Interestingly, it is now well-established that during GPCR/Gi signaling, Gβγ release can activate a myriad of effectors to modulate diverse signaling pathways downstream of GPCRs, including Src, which in turn activate EGFR to promote ERK1/2 activation (43, 68, 69). Gβγ-activated Src can also associate PYK2. When we blocked that action of Gβγ subunits in COS-7 cells by overexpressing the ct-βARK peptide, which is a Gβγ subunit scavenger (70, 71), CRF-stimulated ERK phosphorylation was decreased by ~40%. Moreover, ct-βARK overexpression markedly reduced phosphorylation of Src and Akt. In agreement, another group has also found that CRF1R ERK1/2 signaling is only partially dependent on Gβγ, although their study did not assess the role of Gβγ subunits in the activation of upstream ERK1/2 pathways. Differences in CRF1R-mediated activation of the ERK1/2-MAP kinase cascade are probably attributable to variations in the signaling properties of transfected CRF1Rs expressed in different cell lines utilized in these studies. We are presently investigating other upstream factors including β-arrestins that regulate Src and EGFR mediation of CRF1R ERK1/2 signaling.

Our experiments did demonstrate that CRF-stimulated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and EGFR occurred in parallel, while pretreatment with the EGFR kinase inhibitor, AG1478, caused a concentration-dependent inhibition of CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation. In agreement, it has been shown that EGFR transactivation is required for Ucn1-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in transfected HEK293 cells (5). In contrast to our data indicating that a MMP/HB-EGF ligand mechanism was not involved, however, this group reported that MMP generation of an HB-EGF ligand transactivated the EGFR during CRF1R ERK1/2 signaling (5). Therefore, EGFR transactivation can play a critical role in CRF1R signaling via the ERK1/2-MAP kinase cascade.

Earlier studies have implicated a PI3K-dependent mechanism in CRF1R ERK1/2 signaling based on the observation that pretreatment with PI3K inhibitors attenuated sauvagine- and Ucn1-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in CRF1R-expressing CHO and HEK293 cells (5, 9, 12). PI3K is also involved in CRF2(b)R-stimulated ERK1/2 activation in CHO, A7r5, and mouse neonatal cardiomyocyte cells (12, 19). However, the activation sequence of PI3K, EGFR, and ERK1/2 during CRF1R signaling has not been fully elucidated. Here we observed that pretreating CRF1R-expressing COS-7 cells with the PI3K inhibitors wortmannin and LY294002 inhibited CRF-stimulated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Akt. Previous studies suggest that PI3K activity is required for Gβγ-mediated MAP kinase signaling pathway at a point upstream of Sos and Ras activation (50, 72).

Because we also found that AG1478 abolished phosphorylation of ERK1/2 while only decreasing Akt phosphorylation 25% in transfected COS-7 cells stimulated with CRF, upstream activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway by CRF1R is not strongly dependent on EGFR transactivation. In this context, our study suggests that Src acts as a critical mediator of PI3K activation, independent of EGFR transactivation, which, in turn, stimulates Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Previous studies have shown that activated Src directly associates with PI3K through interaction between the SH3 domain of Src and the proline-rich motif in the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K, thereby increasing the specific activity of PI3K (59). Furthermore, intermediary proteins have also been identified to mediate Src-induced PI3K activation, such as p66Shc, Rap1, and FAK. Thus, our study raises the possibility that Src activates PI3K, although the specific mechanism for this effect remains to be determined.

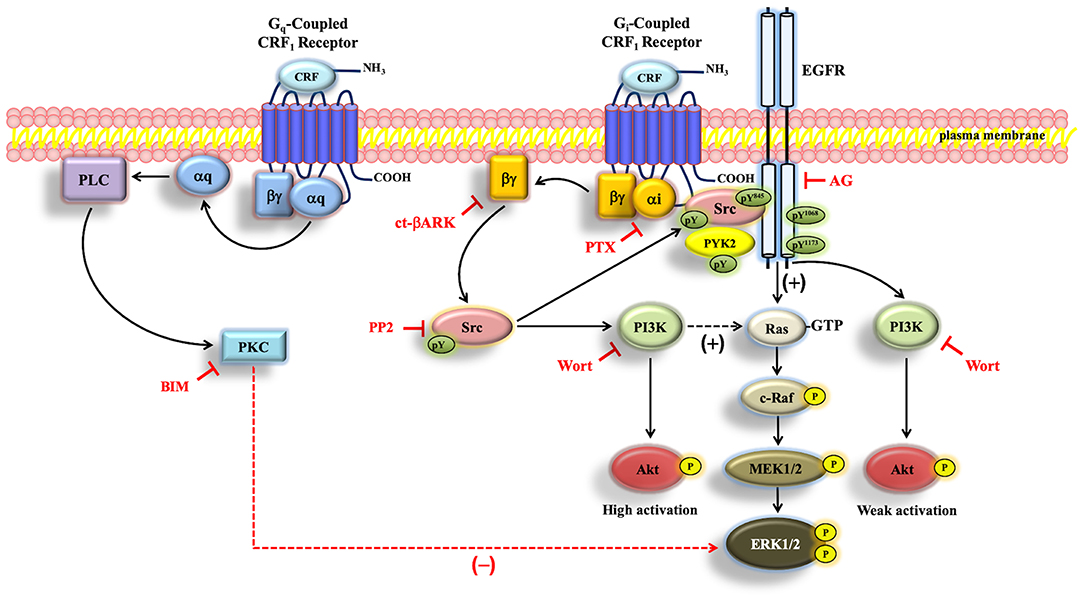

For certain GPCRs, Src has been shown to induce EGFR transactivation, stimulate the PI3K-Akt pathway, and activate the ERK1/2 cascade (43, 48, 70). A novel finding in our study is the rapid and parallel phosphorylation of Src, PYK2, the EGFR, Akt, and ERK1/2 in CRF1R-expressing COS-7 cells stimulated with CRF. Importantly, we demonstrated that inhibiting Src function with PP2 markedly reduced or abolished the CRF-stimulated activation of Src, PYK2, the EGFR, and ERK1/2, suggesting that Src has a central role in regulating CRF1R ERK1/2 signaling. Thus, our results clearly show that Src triggers signal transduction by two important pathways culminating in ERK activation by CRF1R: (i) EGFR activation of the classical Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway, and (ii) PI3K regulation and subsequent activation of ERK1/2 (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Schematic representation of the proposed CRF-mediated ERK1/2/Akt signaling mechanism in CRF1R transfected COS-7 cells. When COS-7 cells are stimulated with CRF, the overexpressed CRF1R leads to activation of Gi protein and the subsequent dissociation of αi-GTP and βγ. Gβγ subunit is able to activate Src, which plays a central role in the activation of EGFR, through the formation of a protein complex that contains CRF1R, EGFR, and Src. PI3K, independently of Akt, is involved in ERK1/2 activation, presumably through Ras/C-Raf/MEK1/2. On the other hand, Src/PYK2 transactivates EGFR. Such EGFR transactivation leads to activation of the MAP kinase/ERK1/2 cascade and parallelly to weak activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway. Solid arrows indicate signaling mechanisms that have been identified. Dashed arrows indicate that the precise mechanism associated with the CRF-mediated regulation of Ras by PI3K and ERK1/2 by PKC remains to be determined. Plus sign (+) means positive regulation, and minus sign (–) means negative regulation of the ERK pathway.

To the best of our knowledge, our study demonstrates for the first time that Src regulates ERK and Akt signaling by the CRF1R. Yuan et al. (20) reported that Src was an upstream regulator of ERK signaling by both the CRF1R and CRF2R in the mouse atrial HL-1 cardiomyocytes cell line based on the effects of antalarmin (a CRF1R antagonist) and anti-sauvagine (a CRF2R antagonist). Although CRF1R was reported to be expressed in the human heart (73, 74), Ikeda et al. (75) reported that CRF2(b)R is the major CRF receptor expressed in the HL-1 mouse atrial cardiomyocyte cell line with no measurable level of CRF1R mRNA. Their data detecting only CRF2R expression in HL-1 cells is consistent with previous and more recent studies demonstrating only CRF2R expression in rat and mouse cardiomyocytes (19, 76, 77). Therefore, ERK1/2 signaling stimulated by Ucns in cardiomyocytes is mediated through CRF2R, which appears to be the main mediator of the cardiac stress response (78, 79), rather than through CRF1R. Additionally, recent observations also indicate that CRF2R controls the cellular organization and colon cancer progression, specifically through the Src/ERK pathway (80, 81). Thus, while all previous findings are relevant to CRF2Rs, our findings show for the first time that Src plays an important role in the regulation of ERK1/2 and Akt signaling by the CRF1R.

An important finding of our study was the detection of a signaling protein scaffold, which contains CRF1R, Src, and EGFR (Figures 6C,D). While the association between CRF1R and Src was totally dependent on CRF agonist activation, a constitutive interaction between CRF1R and EGFR was also detected, which was increased after CRF stimulation. In this context, it has previously reported that some GPCRs physically interact with EGFR in the absence of receptor ligands, a condition that may increase the efficiency of EGFR transactivation (29, 82–84). Thus, it is possible that the detected constitutive association between CRF1R and EGFR facilitates a more rapid CRF agonist-induced recruitment of Src to the EGFR and subsequent phosphorylation and activation of EGFR. With regard to this possibility, the presence of a putative proline-rich domain-binding SH3 motif (ProXXPro; X, any amino acid), located in the carboxyl terminus of the CRF1R (Pro398Thr399Ser400Pro401) may provide a site for the direct interaction between Src and CRF1R after agonist stimulation. However, the CRF1R-Δ386 mutant, which lacks the ProXXPro motif, induces a similar degree of ERK1/2 activation that is induced by the wild-type CRF1R, which suggests this putative region may not participate in the binding to Src (Figure 10A).

Moreover, there is evidence that Tyr phosphorylation of GPCRs plays a role in mediating GPCR-Src interactions (43). For instance, in studies conducted in A431 epidermoid carcinoma cells, stimulation of the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR) with isoproterenol, results in phosphorylation of the receptor on Tyr305 (43, 85). The mutation of this residue to Phe abolishes Src/β2-AR association and impairs Src activation. This residue lies within a canonical Src SH2 binding domain, and it is proposed that Src directly binds the Tyr-phosphorylated β2-AR. Interestingly, the CRF1R has also a single putative SH2 binding domain (TyrXX-hyd; hyd, hydrophobic amino acid) located at the end of the third intracellular loop (Tyr309Arg310Lys311Ala312), which may be a site where Src can directly interact with CRF1R. Further work is needed to establish the importance of this putative site in the agonist-induced CRF1R/Src interaction and Src activation.

β-arrestins are a small family of cytosolic proteins initially identified for their central role in GPCRs desensitization. Furthermore, β-arrestins act as adaptors in clathrin-mediated receptor endocytosis (86). In this sense, their role in CRF1R homologous desensitization and endocytosis is well-recognized, particularly for β-arrestin-2 (24, 63, 87). It is now well-established, however, that β-arrestins can also act as GPCR-signaling transducers that recruit and activate many other signaling molecules, including Src, MAP kinase, NF-κB and PI3K that modulate diverse cellular responses (64, 86). β-arrestin regulation of CRF/CRF1R signaling is still not fully understood.

Regarding β-arrestin regulation of CRF/CRF1R-mediated ERK1/2 activation, β-arrestin-2-mediation of CRF1R internalization participates in the late phase of sustained ERK1/2 activation after G protein activation and B-Raf mediate the early phase of ERK1/2 activation (88). However, overexpression of PDS-95 in HEK293 cells, a CRF1R-interacting protein, inhibited CRF-induced-CRF1R internalization in a PDZ-binding motif-dependent manner by suppressing β-arrestin-2 recruitment. Intriguingly, neither the overexpression of PSD-95 nor the knockdown of endogenous PSD-95 affected CRF-mediated activation of ERK1/2 (89).

Under this experimental evidence and due to the importance of β-arrestins in the scaffolding and activation of Src and regulation of MAP kinase cascades, it was decided to evaluate their role in the CRF/CRF1R-mediated ERK1/2 activation observed in COS-7 cells. Using a phosphorylation-deficient mutant CRF1R, which has a decreased interaction with β-arrestin-2 (24), no significant changes in the activation of ERK1/2 were detected after agonist stimulation (Figure 10A), suggesting that β-arrestin-2 is not involved in the CRF/CRF1R-mediated ERK1/2 activation observed in COS-7. This finding, however, can be explained in part by the low expression level of β-arrestins in COS-7 cells (61, 62). This hypothesis is supported by our data showing that overexpressing β-arrestin-2 in COS-7 notably increased the CRF/CRF1R-mediated ERK1/2 activation (Figure 10B). Likewise, β-arrestin overexpression in COS-7 cells has been found to augment CRF1R internalization (24). Thus, our data provide evidence about the involvement of β-arrestin-2 in the CRF/CRF1R MAP kinase activation in cells with sufficient β-arrestin expression.

Our findings on signaling pathways activated by CRF1R help to elucidate the molecular mechanisms involved in response to stress mediated by this receptor. For instance, kinases in the ERK1/2-MAP kinase cascade, including Src and PYK2, are highly expressed in extended amygdala and forebrain neurons regulating anxiety defensive behavior and stress responsiveness (90–92). Acute stress or central CRF administration induces rapid phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in the basolateral amygdala and hippocampal neurons and prominent anxiety-like behavior in rats and mice (93–95). Furthermore, CRF1Rs can also signal through other cellular pathways that may be involved in post-traumatic stress disorder pathophysiology. As we showed here, CRF1R activated by CRF stimulated rapid phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 that is mediated by upstream Src and PI3K. Preclinical research has shown that activated Akt in the ventral tegmentum promotes resilience to anxiety- and depressive-like responses to stress (3, 96), while high levels of phosphorylated Akt in the dorsal hippocampus and basolateral amygdala prolongs contextual and sensitized fear induced by inescapable stress (3, 97). Therefore, the consequences of CRF1R Akt signaling during trauma and severe stress may differ depending on the brain region. Hence, ERK1/2-MAP kinase and Akt cascade signaling by CRF1R regulated by Src, PYK2, and EGFR may have critical roles in stress-induced anxiety and depression.

In summary, the data presented herein establish that the tyrosine kinase Src serves as a central upstream regulator of ERK1/2-MAP kinase and Akt cascade signaling by the human CRF1R in COS-7 cells. Although CRF1R coupling to G proteins strongly activates PKA and PKC pathways, neither second messenger kinases were involved in CRF1R-mediated ERK1/2 signaling. However, Gβγ released during activation of CRF1R by CRF, particularly from Gi, stimulates phosphorylation of Src and PYK2, which in turn promotes transactivation of the EGFR through the formation of a heterotrimeric complex formed by the association of CRF1R, Src, and EGFR. EGFR transactivation, which occurred independent of MMP generation of the HB-EGF ligand, was essential for CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation while having only a small role in CRF1R-mediated Akt activation. Although PI3K activation contributes to CRF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation, CRF1R-mediated EGFR transactivation is independent of the PI3K/Akt pathway. In contrast, CRF1R Akt signaling while also being mediated by generation of Gβγ and phosphorylation of Src is weakly dependent on EGFR transactivation.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

JO-R, RH, and KC conceived the project. JO-R, FD, and RH designed the experiments. GP-M, AF-G, JH-A, and MD-C carried out the experiments. JO-R, GP-M, and AF-G analyzed and discussed the data. JO-R and RH wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript and took a due care to ensure the integrity of the work.

JO-R was supported by the CINVESTAV-IPN, a University of California MEXUS-CONACYT grant for collaborative projects, CONACYT grants (48777 and 167673) and a Grant for Research on Health from Fundacion Miguel Aleman-2018. RH was funded by the VA Center of Excellence for Stress and Mental Health (CESMH); a VA Merit Review grant, NIH RO1 grants AG050595 and AG022381 from the National Institute of Aging; and a University of California MEXUS-CONACYT grant for collaborative projects. GP-M held a CONACYT graduated scholarship (296029).

This work is dedicated to Dr. Kevin J. Catt, who was an extraordinary scientist, mentor, and friend who passed away on October 1, 2017.

FD was employed by Novaliq GmbH.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be constructed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Dr. Walter Koch for the plasmid pRK5 expressing the carboxyl terminus (βγ-binding domain) of βARK and Silvio Gutkind for the pCEFL-SrcYF-KM which contains the inactive form of SrcYF (dominant-negative). The authors would also like to thank Dr. Jose Antonio Arias-Montaño and M.Sc. Huguet Landa-Galvan, Cinvestav-IPN, Mexico, for their critical comments on the manuscript.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2019.00869/full#supplementary-material

CRF, Corticotropin-releasing factor; CRF1R, corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 1; ct-βARK, β-adrenergic receptor kinase carboxyl terminus peptide; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ERK1/2, extracellularly regulated kinases 1 and 2; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; MAP kinase, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PYK2, proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; c-Src, human homolog of the v-Src Rous sarcoma proto-oncogene; Ucn, urocortin.

1. Deussing JM, Chen A. The corticotropin-releasing factor family: physiology of the stress response. Physiol Rev. (2018) 98:2225–86. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00042.2017

2. Hillhouse EW, Grammatopoulos DK. The molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of the biological activity of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptors: implications for physiology and pathophysiology. Endocr Rev. (2006) 27:260–86. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0034

3. Hauger RL, Risbrough V, Oakley RH, Olivares-Reyes JA, Dautzenberg FM. Role of CRF receptor signaling in stress vulnerability, anxiety, and depression. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2009) 1179:120–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05011.x

4. Dautzenberg FM, Gutknecht E, Van der Linden I, Olivares-Reyes JA, Durrenberger F, Hauger RL. Cell-type specific calcium signaling by corticotropin-releasing factor type 1 (CRF1) and 2a (CRF2(a)) receptors: phospholipase C-mediated responses in human embryonic kidney 293 but not SK-N-MC neuroblastoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. (2004) 68:1833–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.013

5. Punn A, Levine MA, Grammatopoulos DK. Identification of signaling molecules mediating corticotropin-releasing hormone-R1alpha-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) interactions: the critical role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in regulating ERK1/2 but not p38 MAPK activation. Mol Endocrinol. (2006) 20:3179–95. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0255

6. Arzt E, Holsboer F. CRF signaling: molecular specificity for drug targeting in the CNS. Trends Pharmacol Sci. (2006) 27:531–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.08.007

7. Dermitzaki E, Tsatsanis C, Gravanis A, Margioris AN. Corticotropin-releasing hormone induces Fas ligand production and apoptosis in PC12 cells via activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. (2002) 277:12280–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111236200

8. Wang W, Ji P, Dow KE. Corticotropin-releasing hormone induces proliferation and TNF-alpha release in cultured rat microglia via MAP kinase signalling pathways. J Neurochem. (2003) 84:189–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01544.x

9. Rossant CJ, Pinnock RD, Hughes J, Hall MD, McNulty S. Corticotropin-releasing factor type 1 and type 2alpha receptors regulate phosphorylation of calcium/cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate response element-binding protein and activation of p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Endocrinology. (1999) 140:1525–36. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.4.6656

10. Cao J, Cetrulo CL, Theoharides TC. Corticotropin-releasing hormone induces vascular endothelial growth factor release from human mast cells via the cAMP/protein kinase A/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Mol Pharmacol. (2006) 69:998–1006. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.019539

11. Park HJ, Kim HJ, Lee JH, Lee JY, Cho BK, Kang JS, et al. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) downregulates interleukin-18 expression in human HaCaT keratinocytes by activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. J Invest Dermatol. (2005) 124:751–5. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23656.x

12. Brar BK, Chen A, Perrin MH, Vale W. Specificity and regulation of extracellularly regulated kinase1/2 phosphorylation through corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) receptors 1 and 2beta by the CRF/urocortin family of peptides. Endocrinology. (2004) 145:1718–29. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1023

13. Grammatopoulos DK, Randeva HS, Levine MA, Katsanou ES, Hillhouse EW. Urocortin, but not corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway in human pregnant myometrium: an effect mediated via R1alpha and R2beta CRH receptor subtypes and stimulation of Gq-proteins. Mol Endocrinol. (2000) 14:2076–91. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.12.0574

14. Stork PJS. Does Rap1 deserve a bad Rap? Trends Biochem Sci. (2003) 28:267–75. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00087-2

15. Kovalovsky D, Refojo D, Liberman AC, Hochbaum D, Pereda MP, Coso OA, et al. Activation and induction of NUR77/NURR1 in corticotrophs by CRH/cAMP: involvement of calcium, protein kinase A, and MAPK pathways. Mol Endocrinol. (2002) 16:1638–51. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.7.0863

16. Kageyama K, Hanada K, Moriyama T, Imaizumi T, Satoh K, Suda T. Differential regulation of CREB and ERK phosphorylation through corticotropin-releasing factor receptors type 1 and 2 in AtT-20 and A7r5 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2007) 263:90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.08.011

17. Traver S, Marien M, Martin E, Hirsch EC, Michel PP. The phenotypic differentiation of locus ceruleus noradrenergic neurons mediated by brain-derived neurotrophic factor is enhanced by corticotropin releasing factor through the activation of a cAMP-dependent signaling pathway. Mol Pharmacol. (2006) 70:30–40. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.022715

18. Pedersen WA, Wan R, Zhang P, Mattson MP. Urocortin, but not urocortin II, protects cultured hippocampal neurons from oxidative and excitotoxic cell death via corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor type I. J Neurosci. (2002) 22:404–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-02-00404.2002

19. Brar BK, Jonassen AK, Egorina EM, Chen A, Negro A, Perrin MH, et al. Urocortin-II and urocortin-III are cardioprotective against ischemia reperfusion injury: an essential endogenous cardioprotective role for corticotropin releasing factor receptor type 2 in the murine heart. Endocrinology. (2004) 145:24–35; discussion 21-3. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0689

20. Yuan Z, McCauley R, Chen-Scarabelli C, Abounit K, Stephanou A, Barry SP, et al. Activation of Src protein tyrosine kinase plays an essential role in urocortin-mediated cardioprotection. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2010) 325:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.04.013

21. Markovic D, Punn A, Lehnert H, Grammatopoulos DK. Molecular determinants and feedback circuits regulating type 2 CRH receptor signal integration. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Cell Res. (2011) 1813:896–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.02.005

22. Dautzenberg FM, Kilpatrick GJ, Wille S, Hauger RL. The ligand-selective domains of corticotropin-releasing factor type 1 and type 2 receptor reside in different extracellular domains: generation of chimeric receptors with a novel ligand-selective profile. J Neurochem. (1999) 73:821–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730821.x

23. Oakley RH, Laporte SA, Holt JA, Caron MG, Barak LS. Differential affinities of visual arrestin, beta arrestin1, and beta arrestin2 for G protein-coupled receptors delineate two major classes of receptors. J Biol Chem. (2000) 275:17201–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910348199

24. Oakley RH, Olivares-Reyes JA, Hudson CC, Flores-Vega F, Dautzenberg FM, Hauger RL. Carboxyl-terminal and intracellular loop sites for CRF1 receptor phosphorylation and β-arrestin-2 recruitment: a mechanism regulating stress and anxiety responses. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2007) 293:R209–22. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00099.2006

25. Koch WJ, Hawes BE, Inglese J, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Cellular expression of the carboxyl terminus of a G protein-coupled receptor kinase attenuates G beta gamma-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. (1994) 269:6193–7.

26. Servitja JM, Marinissen MJ, Sodhi A, Bustelo XR, Gutkind JS. Rac1 function is required for Src-induced transformation. Evidence of a role for Tiam1 and Vav2 in Rac activation by Src. J Biol Chem. (2003) 278:34339–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302960200

27. Hauger RL, Olivares-Reyes JA, Braun S, Catt KJ, Dautzenberg FM. Mediation of corticotropin releasing factor type 1 receptor phosphorylation and desensitization by protein kinase C: a possible role in stress adaptation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2003) 306:794–803. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.050088

28. Shah BH, Olivares-Reyes JA, Catt KJ. The protein kinase C inhibitor Go6976 [12-(2-Cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo(2,3-a)pyrrolo(3,4-c)-carbazole] potentiates agonist-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation through tyrosine phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol Pharmacol. (2005) 67:184. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.003533

29. Olivares-Reyes J, Shah B, Hernandez-Aranda J, Garcia-Caballero A, Farshori M, Garcia-Sainz J, et al. Agonist-induced interactions between angiotensin AT(1) and epidermal growth factor receptors. Mol Pharmacol. (2005) 68:356–64. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.010637

30. Milan-Lobo L, Gsandtner I, Gaubitzer E, Runzler D, Buchmayer F, Kohler G, et al. Subtype-specific differences in corticotropin-releasing factor receptor complexes detected by fluorescence spectroscopy. Mol Pharmacol. (2009) 76:1196–210. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.059139

31. Hawes BE, van Biesen T, Koch WJ, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Distinct pathways of Gi- and Gq-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. J Biol Chem. (1995) 270:17148–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17148

32. Luttrell LM, Hawes BE, van Biesen T, Luttrell DK, Lansing TJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Role of c-Src tyrosine kinase in G protein-coupled receptor- and Gbetagamma subunit-mediated activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. (1996) 271:19443–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19443

33. Rozengurt E. Mitogenic signaling pathways induced by G protein-coupled receptors. J Cell Physiol. (2007) 213:589–602. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21246

34. Luttrell LM. Composition and function of G protein-coupled receptor signalsomes controlling mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. J Mol Neurosci. (2005) 26:253–64. doi: 10.1385/JMN:26:2-3:253

35. Wee P, Wang Z. Epidermal growth factor receptor cell proliferation signaling pathways. Cancers. (2017) 9:E52. doi: 10.3390/cancers9050052

36. Wright JD, Reuter CWM, Weber MJ. Identification of sites on epidermal growth factor receptors which are phosphorylated by pp60src in vitro. Biochim Biophys Acta. (1996) 1312:85–93. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(96)00027-4

37. Jorissen RN, Walker F, Pouliot N, Garrett TP, Ward CW, Burgess AW. Epidermal growth factor receptor: mechanisms of activation and signalling. Exp Cell Res. (2003) 284:31–53. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4827(02)00098-8

38. Eguchi S, Dempsey PJ, Frank GD, Motley ED, Inagami T. Activation of MAPKs by angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. Metalloprotease-dependent EGF receptor activation is required for activation of ERK and p38 MAPK but not for JNK. J Biol Chem. (2001) 276:7957–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008570200

39. Prenzel N, Zwick E, Daub H, Leserer M, Abraham R, Wallasch C, et al. EGF receptor transactivation by G-protein-coupled receptors requires metalloproteinase cleavage of proHB-EGF. Nature. (1999) 402:884–8. doi: 10.1038/47260

40. Shah BH, Baukal AJ, Shah FB, Catt KJ. Mechanisms of extracellularly regulated kinases 1/2 activation in adrenal glomerulosa cells by lysophosphatidic acid and epidermal growth factor. Mol Endocrinol. (2005) 19:2535–48. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0082

41. Shah B, Yesilkaya A, Olivares-Reyes J, Chen H, Hunyady L, Catt K. Differential pathways of angiotensin II-induced extracellularly regulated kinase 1/2 phosphorylation in specific cell types: role of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor. Mol Endocrinol. (2004) 18:2035–48. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0476

42. Sun Y, McGarrigle D, Huang XY. When a G protein-coupled receptor does not couple to a G protein. Mol Biosyst. (2007) 3:849–54. doi: 10.1039/b706343a

43. Luttrell DK, Luttrell LM. Not so strange bedfellows: G-protein-coupled receptors and Src family kinases. Oncogene. (2004) 23:7969–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208162

44. Dikic I, Tokiwa G, Lev S, Courtneidge SA, Schlessinger J. A role for Pyk2 and Src in linking G-protein-coupled receptors with MAP kinase activation. Nature. (1996) 383:547–50. doi: 10.1038/383547a0

45. Sato K, Sato A, Aoto M, Fukami Y. c-Src phosphorylates epidermal growth factor receptor on tyrosine 845. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (1995) 215:1078–87. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2574

46. Sato K. Cellular functions regulated by phosphorylation of EGFR on Tyr845. Int J Mol Sci. (2013) 14:10761–90. doi: 10.3390/ijms140610761

47. Perkovska S, Mejean C, Ayoub MA, Li J, Hemery F, Corbani M, et al. V1b vasopressin receptor trafficking and signaling: role of arrestins, G proteins and Src kinase. Traffic. (2018) 19:58–82. doi: 10.1111/tra.12535

48. Shah BH, Catt KJ. Calcium-independent activation of extracellularly regulated kinases 1 and 2 by angiotensin II in hepatic C9 cells: roles of protein kinase Cdelta, Src/proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2, and epidermal growth receptor trans-activation. Mol Pharmacol. (2002) 61:343–51. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.2.343

49. Vanhaesebroeck B, Guillermet-Guibert J, Graupera M, Bilanges B. The emerging mechanisms of isoform-specific PI3K signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2010) 11:329–41. doi: 10.1038/nrm2882

50. Hawes BE, Luttrell LM, van Biesen T, Lefkowitz RJ. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is an early intermediate in the G beta gamma-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. (1996) 271:12133–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12133

51. Bisotto S, Fixman ED. Src-family tyrosine kinases, phosphoinositide 3-kinase and Gab1 regulate extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 activation induced by the type A endothelin-1 G-protein-coupled receptor. Biochem J. (2001) 360:77–85. doi: 10.1042/bj3600077

52. Laffargue M, Raynal P, Yart A, Peres C, Wetzker R, Roche S, et al. An epidermal growth factor receptor/Gab1 signaling pathway is required for activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase by lysophosphatidic acid. J Biol Chem. (1999) 274:32835–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32835

53. Yart A, Roche S, Wetzker R, Laffargue M, Tonks N, Mayeux P, et al. A function for phosphoinositide 3-kinase beta lipid products in coupling beta gamma to Ras activation in response to lysophosphatidic acid. J Biol Chem. (2002) 277:21167–78. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110411200

54. Liu L, Xie Y, Lou L. PI3K is required for insulin-stimulated but not EGF-stimulated ERK1/2 activation. Eur J Cell Biol. (2006) 85:367–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.11.005

55. Sampaio C, Dance M, Montagner A, Edouard T, Malet N, Perret B, et al. Signal strength dictates phosphoinositide 3-kinase contribution to Ras/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 activation via differential Gab1/Shp2 recruitment: consequences for resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition. Mol Cell Biol. (2008) 28:587–600. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01318-07

56. Duckworth BC, Cantley LC. Conditional inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade by wortmannin. Dependence on signal strength. J Biol Chem. (1997) 272:27665–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27665

57. New DC, Wu K, Kwok AW, Wong YH. G protein-coupled receptor-induced Akt activity in cellular proliferation and apoptosis. FEBS J. (2007) 274:6025–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06116.x

58. Arcaro A, Aubert M, Espinosa del Hierro ME, Khanzada UK, Angelidou S, Tetley TD, et al. Critical role for lipid raft-associated Src kinases in activation of PI3K-Akt signalling. Cell Signal. (2007) 19:1081–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.12.003

59. Pleiman CM, Hertz WM, Cambier JC. Activation of phosphatidylinositol-3′ kinase by Src-family kinase SH3 binding to the p85 subunit. Science. (1994) 263:1609–12. doi: 10.1126/science.8128248

60. Strungs EG, Luttrell LM. Arrestin-dependent activation of ERK and Src family kinases. Handb Exp Pharmacol. (2014) 219:225–57. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-41199-1_12

61. Menard L, Ferguson SS, Zhang J, Lin FT, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG, et al. Synergistic regulation of beta2-adrenergic receptor sequestration: intracellular complement of beta-adrenergic receptor kinase and beta-arrestin determine kinetics of internalization. Mol Pharmacol. (1997) 51:800–8. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.5.800

62. Luttrell LM, Ferguson SS, Daaka Y, Miller WE, Maudsley S, Della Rocca GJ, et al. Beta-arrestin-dependent formation of beta2 adrenergic receptor-Src protein kinase complexes. Science. (1999) 283:655–61. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.655

63. Holmes KD, Babwah AV, Dale LB, Poulter MO, Ferguson SS. Differential regulation of corticotropin releasing factor 1alpha receptor endocytosis and trafficking by beta-arrestins and Rab GTPases. J Neurochem. (2006) 96:934–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03603.x

64. Inda C, Armando NG, Dos Santos Claro PA, Silberstein S. Endocrinology and the brain: corticotropin-releasing hormone signaling. Endocr Connect. (2017) 6:R99–120. doi: 10.1530/EC-17-0111

65. Papadopoulou N, Chen J, Randeva HS, Levine MA, Hillhouse EW, Grammatopoulos DK. Protein kinase A-induced negative regulation of the corticotropin-releasing hormone R1alpha receptor-extracellularly regulated kinase signal transduction pathway: the critical role of Ser301 for signaling switch and selectivity. Mol Endocrinol. (2004) 18:624–39. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0365

66. Robichaux WG, Cheng X. Intracellular cAMP sensor EPAC: physiology, pathophysiology, and therapeutics development. Physiol Rev. (2018) 98:919–1053. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2017

67. Van Kolen K, Dautzenberg FM, Verstraeten K, Royaux I, De Hoogt R, Gutknecht E, et al. Corticotropin releasing factor-induced ERK phosphorylation in AtT20 cells occurs via a cAMP-dependent mechanism requiring EPAC2. Neuropharmacology. (2010) 58:135–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.06.022

68. Ma YC, Huang J, Ali S, Lowry W, Huang XY. Src tyrosine kinase is a novel direct effector of G proteins. Cell. (2000) 102:635–46. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00086-6