94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

OPINION article

Front. Endocrinol. , 04 May 2017

Sec. Thyroid Endocrinology

Volume 8 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00091

This article is part of the Research Topic The Association of Other Autoimmune Diseases in Patients with Thyroid Autoimmunity View all 19 articles

Because of the rapid emotional and endocrine changes in the postpartum period (1), postpartum mood disorders represent the most frequent form of maternal psychiatric morbidity (2–4). Postpartum mood disorders vary from a mild form of transient depression (maternity blues) to full-blown postpartum depression and severe psychosis (5, 6). Postpartum depression affects 10–30% of women within 1 year after delivery (7), and its risk is measurable already at 3 (8) or 7 days (2) postpartum. This risk predicts depression development in the following months (9, 10).

Thyroid function abnormalities exhibit comorbidity with various psychiatric disorders, including maternal depression. There are one-tenth of a million studies on mood disorders, but fewer than 5,000 (3.9% of almost 125,000) concern mood disorders in the postpartum period. Similarly, studies on autoimmune thyroid disease are almost 20,000, but only 72 (3.7% of 19,360) concern postpartum mood disorders and thyroid disorders, and merely 5 focus on postpartum mood disorders and thyroid autoimmunity. Thus, we hope that our opinion will stimulate interest.

Affective disorders and autoimmune thyroiditis are well known to affect women during puerperium. Up to 23% of all new mothers experiences thyroid dysfunction postpartum (11), compared with a prevalence of 3–4% in the general population (12). Maternal thyroid autoimmunity refers to the detection of thyroid autoantibodies against thyroperoxidase (TPOAb) and/or thyroglobulin (TgAb) in combination with normal thyroid function, and it has been reported to affect between 8 and 14% women in reproductive age (13). Concerning positivity for TPOAb, approximately 10% of pregnant women are TPOAb positive, and around one-third to half of them will develop postpartum thyroiditis (PPT) within 12 months after delivery (11, 14).

At least 2–3% of women have some form of thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy, and 10–17% of women have thyroid autoimmune disease despite euthyroidism (15, 16). Thyroid dysfunction in pregnancy is classified as (i) primary overt hypothyroidism (elevated TSH and a decreased FT4 during gestation with both concentrations outside the trimester-specific reference ranges) or subclinical hypothyroidism (with a TSH elevated beyond the upper limit of the pregnancy-specific reference range); (ii) hyperthyroidism (autoimmune Graves’ disease or gestational transient thyrotoxicosis) (17); and (iii) positivity of thyroid autoantibodies, which increases the risk of thyroid dysfunction following delivery and during the postpartum period. PPT is an inflammatory autoimmune condition, which occurs within the first year after delivery or miscarriage (a period when the immunosuppressive effect of pregnancy disappears), in women who were euthyroid prior to pregnancy (16, 18).

The association between subclinical hypothyroidism, with and without raised TPOAb, and well-being or depression is still controversial, in spite of many studies on this topic. Before moving to the abnormal setting, it is appropriate to mention the prevalence of thyroid autoantibodies in the general population and their association with mood disorders outside of the postpartum context.

An interaction between thyroid autoantibodies and mood disorders was first valuated in the early 1980s (19). Prevalence rates of thyroid autoantibodies in the general population vary widely, depending on several reasons, including sex and age distribution, geographic origin, variations in the cutoff level for antibody positivity (20–22). In an Italian survey, the overall prevalence of thyroid autoantibodies, using a cutoff of 1:100 for both microsomal antibodies and/or thyroid autoantibodies was 12.6% (females, 17.3%; males, 7.0%) (23). The reported prevalence in the United States healthy population was 13% for TPOAb (threshold at ≥0.5 IU/ml) and 11.5% for TgAb (threshold at ≥1.0 IU/ml) (21). Overall, the association of circulating thyroid autoantibodies with not otherwise specified mood disorders cannot be considered clearly established.

On the contrary, increased prevalence of circulating thyroid autoantibodies is shown in the following forms of mood disorders: treatment-refractory cases (24, 25), severe (26–28), atypical depression (29), anxiety disorders or mood disorders (30), and depression during early gestation, postpartum, and perimenopause (31–36).

In a population-based study, depression and anxiety were not associated with thyroid autoantibodies (37). In 2,049 subjects, autoimmune markers (TPOAb, anti-nuclear autoantibodies, and several other autoantibodies) were not associated with depression symptoms (38). Elevated TPOAb levels cannot be used as a general marker of poor well-being or depression, as shown in a large population-based Danish study of 8,214 individuals (39).

With regard to bipolar disorder, sample size was small in several studies (40–43). Offspring of bipolar subjects were found more susceptible to develop thyroid autoantibodies independently from the susceptibility to develop psychiatric disorders (44). Autoimmune thyroiditis was suggested as a possible genetic biomarker for bipolar disorder in a twin study (45). Hashimoto’s encephalopathy can also occur with a bipolar disorder (46, 47), being vasculitis-related abnormalities in cortical perfusion one of the possible mechanisms (48). High levels of TPOAb were detected by Blanchin et al. (49) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with Hashimoto’s encephalopathy. Both sera from their patients and monoclonal TPOAb were able to link monkey cerebellar cells. Moreover, normal human astrocytes from primary cultures binded monoclonal TPOAb. The presence of antigenic targets for anti-TSH-receptor IgG on human cortical neurons and TgAb IgG in cerebral vasculature was described by Moodley et al. (50).

Risk for postpartum depression and alexithymia showed a direct borderline statistically significant correlation with serum TPOAb, suggesting that these mood disorders could be neurobehavioral consequences of an autoimmune attack (because of the TPOAb circulation in the CSF and of their possible cross-reaction with cerebral autoantigens) (3).

The PPT is more likely to occur in pregnant thyroid autoantibodies positive women compared to negative women (11). Most PPT women develop thyroid dysfunction during the first 6 months postpartum with initial mild symptoms of hyperthyroidism (heat intolerance, palpitations, weight loss, and fatigue) and a subsequent hypothyroid phase, frequently associated with depression (51). Approximately 50% of PPT women return euthyroid by 12 months PP (52).

Much uncertainty remains regarding the relationship between PPT and non-psychotic depression in thyroid autoantibodies positive euthyroid women. Harris et al. (53) found no difference in the rate of postpartum depression between thyroid autoantibodies positive women and thyroid autoantibodies negative women. However, the same author in 1992 reported an association between thyroid autoantibodies positivity and PPT (35). Subsequent studies on TPOAb positivity and postpartum depression in euthyroid women are controversial, founding no association (31, 54) or an association (34, 55). For instance, Kuijpens et al. studied prospectively 310 unselected women during gestation and up to 36 weeks postpartum (34). The presence of TPOAb was independently associated with depression at 12-week gestation and at 4 and 12 weeks postpartum (odds ratios between 2.4 and 3.8) in a prospective study on 310 unselected women (34).

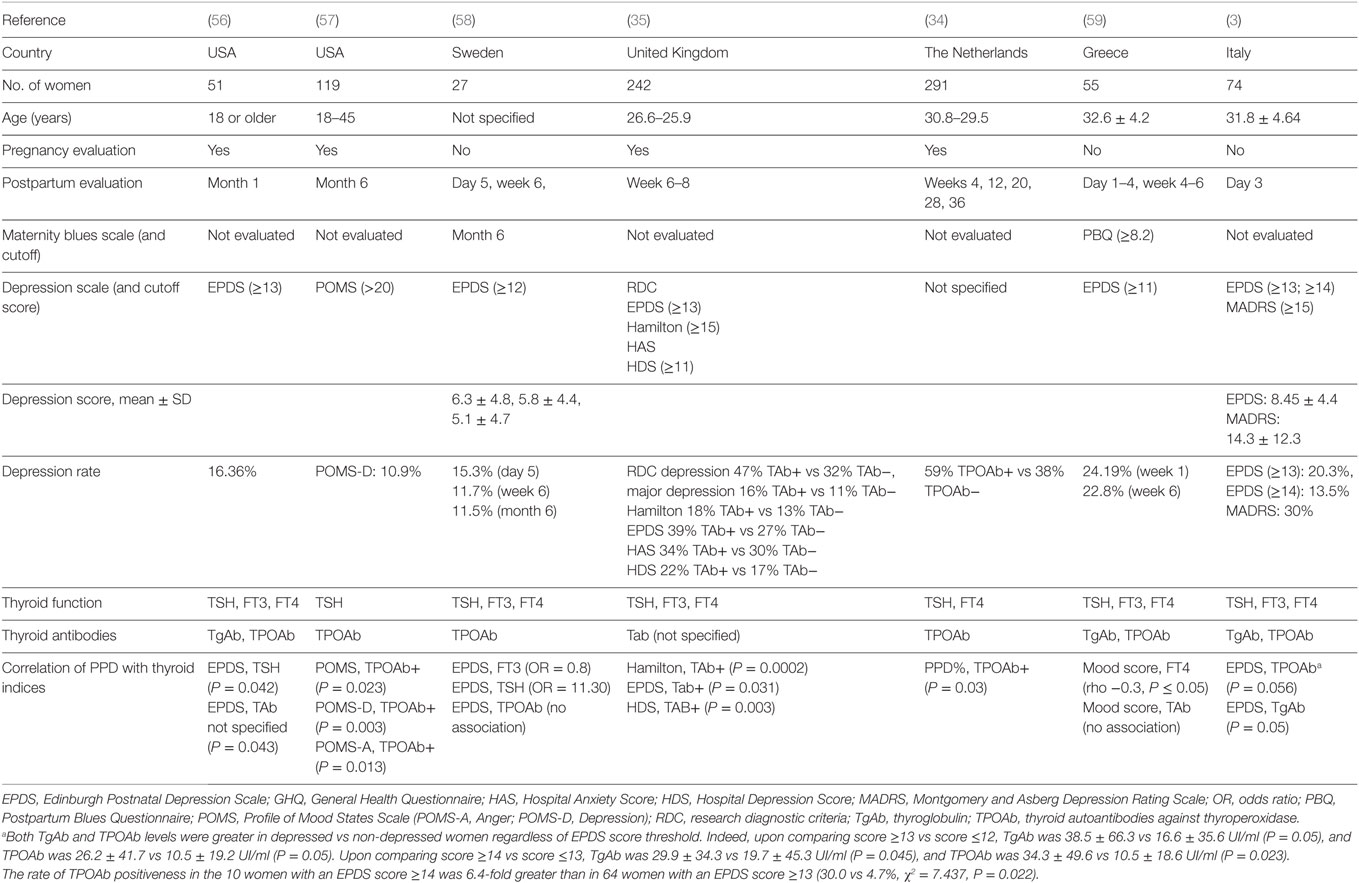

A summary of the English-language literature in the last 25 years, which addressed the relationship between postpartum mood disorders and thyroid autoantibodies, is summarized in (Table 1).

Table 1. Schematic comparison of the last 25 years studies on the relationship between postpartum mood disorders and thyroid autoantibodies.

In a follow-up study, Harris et al. (35) showed a significantly greater depression incidence in 110 thyroid autoantibodies positive women (47%) compared with 132 negative women (32%) regardless of thyroid dysfunction (Table 1). The same author in 2002 reported no difference in postpartum depression in TPOAb positive women treated with levothyroxine compared with TPOAb positive women given placebo and overall rates of major depression of 18.5% and depression in general of 38%, providing further evidence linking PPT and TPOAb positivity (60). No association was found between thyroid autoantibodies and postpartum mood disorders by Lambrinoudaki et al. (59). In another study, lower levels of serum FT3 were associated with increased incidence of mood disorders in the first postpartum week; only TPOAb and TgAb were significantly higher in women at risk for postpartum depression compared to women not at risk, using EPDS cutoff values of ≥13 or ≥14 (3). The presence of thyroid autoantibodies or higher TSH levels during the postpartum period may be related to depressive symptoms or dysphoric mood (56). Pregnant TPOAb positive women were shown to have higher depressive symptoms during pregnancy, and higher depression, anger, and total mood disturbance postpartum, regardless of the development of PPT (57).

Sylvén et al. (58) found an association between the TSH level over the clinical cutoff of 4.0 mU/l and the increased risk for depressive symptoms at 6 months postpartum in a Swedish population-based cohort (OR 11.30, 95% CI 1.93—66.11) (Table 1).

Tryptophan catabolites, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, serotonin, and autoimmunity, as possible mediators of the immuno-inflammation consequences and the oxidative and nitrosative stress, may induce postpartum depression (61).

In summary, there is scanty literature on the relationship between postpartum mood disorders and thyroid autoantibodies, with data available for the United States and a few European countries. Furthermore, these available data stem from differing methodologies (e.g., psychometric scales, thyroid autoantibodies assays, time and frequency of measurements). Nevertheless, a direct, positive, unfavorable relationship does appear. Also studies evaluating the relationship between thyroid autoantibodies’ positivity and postpartum in euthyroid women have been mixed, with most of the studies demonstrating a significant association, confirmed also by a recent review of Dama et al. (62), who reported four of five studies finding a significant associations between TPOAb during gestation and postpartum depression (34–36, 57) and two of four studies finding links between postpartum TPOAb and depression (3, 34).

The cost-effectiveness of integrated perinatal mental health care has not been fully evaluated (63, 64) and is still controversial. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (at a cut point of 16) had an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of £41,103 (€45,398, $67,130) per quality-adjusted life years (QALY) compared with routine care only. The ICER for all other strategies ranged from £49,928 to £272,463 per QALY vs routine care only, while the probability that no formal identification strategy was cost effective was 88% (59%) at a cost-effectiveness threshold of £20,000 (£30,000) per QALY. The major determinant of cost-effectiveness seems to be the potential additional costs of managing women incorrectly diagnosed as depressed (65). Leung et al. (66) showed that the use of EPDS as the screening tool and the provision of follow-up care had resulted in an improvement in maternal mental health at 6 months.

Negative emotions during pregnancy should be recognized using self-report questionnaires as Profile of Mood States Scale, to select women at risk for deflected postpartum mood and requiring psychological support. However, more research is required to clarify the predictive value and pathophysiological implications of the associations between TgAb and/or TPOAb positivity and postpartum depression and to support solid evidence of benefit and cost-effectiveness of a careful neuropsychological evaluation in more 10% of all pregnant women (positive for TPO or Tg antibodies).

Future research on postpartum mood disorders should target genetic variations of the deiodinases, thyroid hormone transporters, and identification of central nervous system-expressed targets of TPOAb (or other coexisting Ab which are specifically directed against these targets), particularly in CNS areas engaged in depression and/or alexithymia.

All the authors have participated in drafting and revising the manuscript submitted whose contents they approve.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Bloch M, Daly RC, Rubinow DR. Endocrine factors in the etiology of postpartum depression. Compr Psychiatry (2003) 44:234–46. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00034-8

2. Dennis CL. Can we identify mothers at risk for postpartum depression in the immediate postpartum period using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale? J Affect Disord (2004) 78:163–9. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00299-9

3. Le Donne M, Settineri S, Benvenga S. Early Postpartum alexithymia and risk for depression: relationship with serum thyrotropin free thyroid hormones and thyroid autoantibodies. Psychoneuroendocrinology (2012) 37:519–33. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.08.001

4. Mento C, Le Donne M, Crisafulli S, Rizzo A, Settineri S. BMI at early puerperium: body image, eating attitudes and mood states. J Obstet Gynaecology (2017) 21:2017. doi:10.1080/01443615.2016.1250727

6. Henshaw C, Foreman D, Cox J. Postnatal blues: a risk factor for postnatal depression. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol (2004) 25:267–729. doi:10.1080/01674820400024414

7. Fergerson SS, Jamieson DJ, Lindsay M. Diagnosing postpartum depression: can we do better? Am J Obstet Gynecol (2002) 186:899–902. doi:10.1067/mob.2002.123404

8. Teissedre F, Chabrol H. A study of the Edimburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) on 859 mothers: detection of mothers at risk for postpartum depression. Encephale (2004) 30:376–81. doi:10.1016/S0013-7006(04)95451-6

9. Beck CT, Reynolds MA, Rutowski P. Maternity blues and postpartum depression. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs (1992) 21:287–93. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.1992.tb01739.x

10. Reck C, Stehle E, Reinig K, Mundt C. Maternity blues as a predictor of DSM-IV depression and anxiety disorders in the first three months postpartum. J Affect Disord (2009) 113:77–87. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.003

11. Stagnaro-Green A. Approach to the patient with postpartum thyroiditis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2012) 97:334–42. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-2576

12. Basraon S, Costantine MM. Mood disorders in pregnant women with thyroid dysfunction. Clin Obstet Gynecol (2011) 54:506–14. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182273089

13. Vissenberg R, Goddijn M, Mol BW, van der Post JA, Fliers E, Bisschop PH. Thyroid dysfunction in pregnant women: clinical dilemmas. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd (2012) 156:A5163.

14. Abalovich M, Mitelberg L, Allami C, Gutierrez S, Alcaraz G, Otero P, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and thyroid autoimmunity in women with infertility. Gynecol Endocrinol (2007) 23:279–83. doi:10.1080/09513590701259542

15. Milanesi A, Gregory AB. Management of hypothyroidism in pregnancy. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes (2011) 18:304–9. doi:10.1097/MED.0b013e32834a91d1

16. Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, Brown RS, Chen H, Dosiou C, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and the postpartum. Thyroid (2017) 27:315–89. doi:10.1089/thy.2016.0457

17. Cooper DS, Laurberg P. Hyperthyroidism in pregnancy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol (2013) 1:238–49. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70086-X

18. Medenica S, Nedeljkovic O, Radojevic N, Stojkovic M, Trbojevic B, Pajovic B. Thyroid dysfunction and thyroid autoimmunity in euthyroid women in achieving fertility. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci (2015) 19:977–87.

19. Gold MS, Pottash AL, Extein I. “Symptomless” autoimmune thyroiditis in depression. Psychiatry Res (1982) 6:261–9. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(82)90015-4

20. Vanderpump MP, Tunbridge WM, French JM, Appleton D, Bates D, Clark F, et al. The incidence of thyroid disorders in the community: a twenty-year follow-up of the Whickham survey. Clin Endocrinol (1995) 43:55–68. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb01894.x

21. Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, Hannon WH, Gunter EW, Spencer CA, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988–1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2002) 87:489–99. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.2.8182

22. McGrogan A, Seaman HE, Wright JW, de Vries CS. The incidence of autoimmune thyroid disease: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Endocrinol (2008) 69:687–96. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03338.x

23. Aghini-Lombardi F, Antonangeli L, Martino E, Vitti P, Maccherini D, Leoli F, et al. The spectrum of thyroid disorders in an iodine-deficient community: the Pescopagano survey. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (1999) 84:561–6. doi:10.1210/jcem.84.2.5508

24. Browne JL, Rice JL, Evans DL, Prange AJ. Triiodothyronine augmentation of the antidepressant effect of the nontricyclic antidepressant trazodone. J Nerv Ment Dis (1990) 178:598–9. doi:10.1097/00005053-199009000-00010

25. Eller T, Metsküla K, Talja I, Maron E, Uibo R, Vasar V. Thyroid autoimmunity and treatment response to escitalopram in major depression. Nord J Psychiatry (2010) 64:253–7. doi:10.3109/08039480903487533

26. Custro N, Scafidi V, Lo Baido R, Nastri L, Abbate G, Cuffaro MP, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism resulting from autoimmune thyroiditis in female patients with endogenous depression. J Endocrinol Invest (1994) 17:641–6. doi:10.1007/BF03349679

27. König F, von Hippel C, Petersdorff T, Kaschka W. Thyroid autoantibodies in depressive disorders. Acta Med Austriaca (1999) 26:126–8.

28. Leyhe T, Hügle M, Gallwitz B, Saur R, Eschweiler GW. Increased occurrence of severe episodes in elderly depressed patients with elevated anti-thyroid antibody levels. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2009) 24:779–81. doi:10.1002/gps.2260

29. Fountoulakis KN, Iacovides A, Grammaticos P, Kaprinis G, Bech P. Thyroid function in clinical subtypes of major depression: an exploratory study. BMC Psychiatry (2004) 4:6. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-4-6

30. Carta MG, Loviselli A, Hardoy MC, Massa S, Cadeddu M, Sardu C, et al. The link between thyroid autoimmunity (antithyroid peroxidase autoantibodies) with anxiety and mood disorders in the community: a field of interest for public health in the future. BMC Psychiatry (2004) 4:25. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-4-25

31. Pop VJ, de Rooy HA, Vader HL, van der Heide D, van Son MM, Komproe IH. Microsomal antibodies during gestation in relation to postpartum thyroid dysfunction and depression. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) (1993) 129:26–30.

32. Pop VJ, Maartens LH, Leusink G, van Son MJ, Knottnerus AA, Ward AM, et al. Are autoimmune thyroid dysfunction and depression related? J Clin Endocrinol Metab (1998) 1998(83):3194–7. doi:10.1210/jcem.83.9.5131

33. Pop VJ, Wijnen HA, Lapkienne L, Bunivicius R, Vader HL, Essed GG. The relation between gestational thyroid parameters and depression: a reflection of the downregulation of the immune system during pregnancy? Thyroid (2006) 16:485–92. doi:10.1089/thy.2006.16.485

34. Kuijpens JL, Vader HL, Drexhage HA, Wiersinga WM, van Son MJ, Pop VJ. Thyroid peroxidase antibodies during gestation are a marker for subsequent depression postpartum. Eur J Endocrinol (2001) 145:579–84. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1450579

35. Harris B, Othman S, Davies JA, Weppner GJ, Richards CJ, Newcombe RG, et al. Association between postpartum thyroid dysfunction and thyroid antibodies and depression. BMJ (1992) 305:152–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.305.6846.152

36. Lazarus JH, Hall R, Othman S, Parkes AB, Richards CJ, McCulloch B, et al. The clinical spectrum of postpartum thyroid disease. QJM (1996) 1996(89):429–35. doi:10.1093/qjmed/89.6.429

37. Engum A, Bjøro T, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Thyroid autoimmunity, depression and anxiety; are there any connections? An epidemiological study of a large population. J Psychosom Res (2005) 59:263–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.04.002

38. Iseme RA, McEyoy M, Agnew L, Kelly B, Attia J, Walker FR, et al. Autoantibodies are not predictive markers for the development of depressive symptoms in a population-based cohort of older adults. Eur Psychiatry (2015) 30:694–700. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.06.006

39. Fiaallegaard K, Kventhy J, Allerup PN, Bech P, Ellervik C. Well-being and depression in individuals with subclinical hypothyroidism and thyroid autoimmunity – a general population study. Nord J Psych (2015) 68:73–8. doi:10.3109/08039488.2014.929741

40. Nemeroff CB, Simon JS, Haggerty JJ Jr, Evans DL. Antithyroid antibodies in depressed patients. Am J Psychiatry (1985) 142:840–3. doi:10.1176/ajp.142.7.840

41. Haggerty JJ Jr, Evans DL, Golden RN, Pedersen CA, Simon JS, Nemeroff CB. The presence of antithyroid antibodies in patients with affective and nonaffective psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry (1990) 27:51–60. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(90)90019-X

42. Bartalena L, Bogazzi F, Donadel G, Martino E, Gabrielli F, Pinchera A. The differentiation-inducing agent sodium butyrate produces divergent effects on albumin and thyroxine-binding globulin synthesis by human hepatoblastoma-derived (Hep G2) cells. J Endocrinol Invest (1990) 13:917–22. doi:10.1007/BF03349656

43. Degner D, Haust M, Meller J, Rüther E, Reulbach U. Association between autoimmune thyroiditis and depressive disorder in psychiatric outpatients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2015) 265:67–72. doi:10.1007/s00406-014-0529-1

44. Hillegers MH, Reichart CG, Wals M, Verhulst FC, Ormel J, Nolen WA, et al. Signs of a higher prevalence of autoimmune thyroiditis in female offspring of bipolar parents. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol (2007) 17:394–9. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.10.005

45. Vonk R, van der Schot AC, Kahn RS, Nolen WA, Drexhage HA. Is autoimmune thyroiditis part of the genetic vulnerability (or an endophenotype) for bipolar disorder? Biol Psychiatry (2007) 62:135–40. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.041

46. Müssig K, Bartels M, Gallwitz B, Leube D, Häring HU, Kircher T. Hashimoto’s encephalopathy presenting with bipolar affective disorder. Bipolar Disord (2005) 7(3):292–7. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00196.x

47. Bocchetta A, Tamburini G, Cavolina P, Serra A, Loviselli A, Piga M. Affective psychosis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, and brain perfusion abnormalities: case report. Clin Pract Epidemol Ment Health (2007) 3:31. doi:10.1186/1745-0179-3-31

48. Bocchetta A, Traccis A, Mosca A, Serra A, Tamburini G, Loviselli A. Bipolar disorder and antithyroid antibodies: review and case series. Int J Bipolar Disord (2016) 4:5. doi:10.1186/s40345-016-0046-4

49. Blanchin S, Coffin C, Viader F, Ruf J, Carayon P, Potier F, et al. Anti-thyroperoxidase antibodies from patients with Hashimoto’s encephalopathy bind to cerebellar astrocytes. J Neuroimmunol (2007) 192:13–20. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.08.012

50. Moodley K, Botha J, Raidoo DM, Naidoo S. Immuno-localisation of anti-thyroid antibodies in adult human cerebral cortex. J Neurol Sci (2011) 302:114–7. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2010.11.027

51. Muller AF, Drexhage HA, Berghout A. Postpartum thyroiditis and autoimmune thyroiditis in women of childbearing age: recent insights and consequences for antenatal and postnatal care. Endocr Rev (2001) 22(5):605–30. doi:10.1210/edrv.22.5.0441

52. Stagnaro-Green A, Glinoer D. Thyroid autoimmunity and risk of miscarriage. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab (2004) 18:167–81. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2004.03.007

53. Harris B, Fung H, Johns S, Kologlu M, Bhatti R, McGregor AM, et al. Transient post-partum thyroid dysfunction and postnatal depression. J Affect Disord (1989) 17:243–9. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(89)90006-2

54. Kent GN, Stuckey BG, Allen JR, Lambert T, Gee V. Postpartum thyroid dysfunction: clinical assessment and relationship to psychiatric affective morbidity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) (1999) 51:429–38. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00807.x

55. Lazarus JH. Clinical manifestations of postpartum thyroid disease. Thyroid (1999) 9:685–9. doi:10.1089/thy.1999.9.685

56. McCoy SJ, Beal M, Payton E, Stewart AL, DeMers AM, Watson GH. Postpartum thyroid measures and depressive symptomology: a pilot study. J Am Ostheopath Assoc (2008) 1088:503–7.

57. Groer MW, El-Badri N, Djeu J, Williams SN, Kane B, Szekeres K. Suppression of natural killer cell cytotoxicity in postpartum women: time course and potential mechanisms. Biol Res Nurs (2013) 16:320–6. doi:10.1177/1099800413498927

58. Sylvén SM, Elenis E, Michelakos T, Larsson A, Olovsson M, Poromaa IS, et al. Thyroid function tests at delivery and risk for postpartum depressive symptoms. Psychoneuroendocrinology (2013) 38:1007–13. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.10.004

59. Lambrinoudaki I, Rizos D, Armeni E, Pliatsika P, Leonardou A, Sygelou A, et al. Thyroid function and postpartum mood disturbances in Greek women. J Affect Disord (2010) 121:278–82. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.07.001

60. Harris B, Oretti R, Lazarus J, Parkes A, John R, Richards C, et al. Randomised trial of thyroxine to prevent postnatal depression in thyroid-antibody-positive women. Br J Psychiatry (2002) 180:327–30. doi:10.1192/bjp.180.4.327

61. Anderson G, Maes M. Postpartum depression: psychoneuroimmunological underpinnings and treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat (2013) 9:277–87. doi:10.2147/NDT.S25320

62. Dama M, Steiner M, Lieshout RV. Thyroid peroxidase autoantibodies and perinatal depression risk: a systematic review. J Affect Disord (2016) 198:108–21. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.021

63. Stevenson MD, Scope A, Sutcliffe PA, Booth A, Slade P, Parry G, et al. Group cognitive behavioural therapy for postnatal depression: a systematic review of clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and value of information analyses. Health Technol Assess (2010) 14:1–iv. doi:10.3310/hta14440

64. Hewitt CE, Gilbody SM. Is it clinically and cost effective to screen for postnatal depression: a systematic review of controlled clinical trials and economic evidence. BJOG (2009) 116:1019–27. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02148.x

65. Paulden M, Palmer S, Hewitt C, Gilbody S. Screening for postnatal depression in primary care: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ (2009) 339:b5203. doi:10.1136/bmj.b5203

Keywords: postpartum, mood disorders, autoimmunity, thyroid hormones, depression

Citation: Le Donne M, Mento C, Settineri S, Antonelli A and Benvenga S (2017) Postpartum Mood Disorders and Thyroid Autoimmunity. Front. Endocrinol. 8:91. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00091

Received: 20 February 2017; Accepted: 06 April 2017;

Published: 04 May 2017

Edited by:

Alex Stewart Stagnaro-Green, University of Illinois Rockford College of Medicine, USAReviewed by:

Bijay Vaidya, University of Exeter, UKCopyright: © 2017 Le Donne, Mento, Settineri, Antonelli and Benvenga. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria Le Donne, bWxlZG9ubmVAdW5pbWUuaXQ=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.