95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Endocrinol. , 16 December 2013

Sec. Cellular Endocrinology

Volume 4 - 2013 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2013.00191

This article is part of the Research Topic Astrocytic-neuronal-astrocytic Pathway Selection for Formation and Degradation of Glutamate/GABA View all 18 articles

In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that glutamate can be oxidized for energy by brain astrocytes. The ability to harvest the energy from glutamate provides astrocytes with a mechanism to offset the high ATP cost of the uptake of glutamate from the synaptic cleft. This brief review focuses on oxidative metabolism of glutamate by astrocytes, the specific pathways involved in the complete oxidation of glutamate and the energy provided by each reaction.

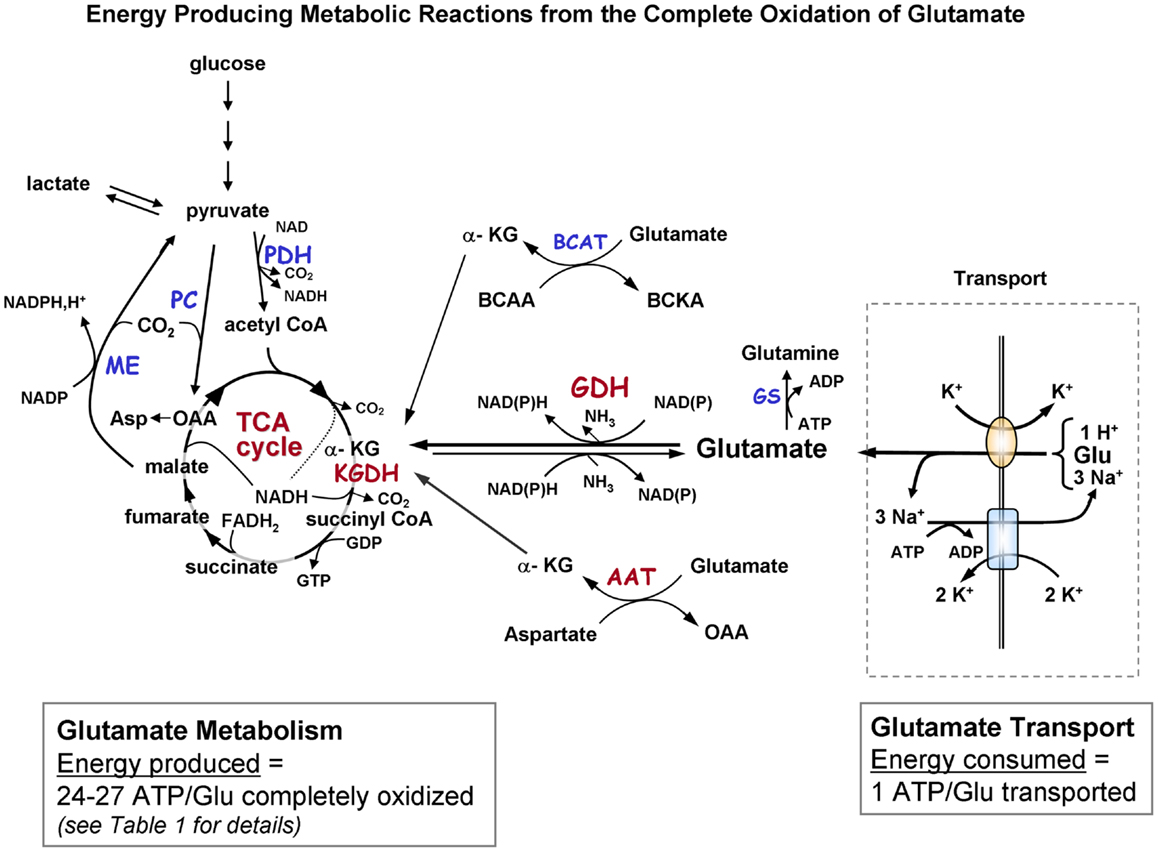

One of the most essential roles of astrocytes in brain is removal of the neurotransmitter glutamate from the synaptic cleft as it is crucial that a low resting glutamate concentration of ∼1–10 μM be maintained for continued glutamatergic neurotransmission and brain function (1–3). Astrocytes perform this key function by rapidly and efficiently removing glutamate which increases orders of magnitude in concentration to ∼100 μM–1 mM after depolarization of neurons (4, 5). Uptake of glutamate is a very expensive proposition since the astrocyte transporters that mediate glutamate transport 3 Na+ molecules which must be exported by the enzyme Na+, K+-ATPase. Thus the uptake of one molecule of glutamate by an astrocyte requires the expenditure of one molecule of ATP (1). To pay the high cost of removing large amounts of glutamate from glutamatergic synapses, astrocytes must form large amounts of ATP from the metabolism of glucose or other substrates (see Figure 1A; Table 1). About 30% of the oxidative metabolism in brain in vivo takes place in astrocytes (6–9); however, it is not likely that these cells oxidize sufficient glucose to generate the ATP required for the transport of such massive amounts of glutamate (10–16). A number of groups have shown that astrocytes have a sufficiently high rate of glutamate oxidative metabolism to pay the high cost of glutamate uptake (11, 17, 18). This short review summarizes the information on the use of glutamate in astrocytes and recent evidence on the role of protein complexes in facilitating glutamate metabolism (19, 20). The goal of this paper is to provide a short, very concise, and focused review, and to point readers to many excellent more in depth manuscripts recently published (2, 3, 6, 16, 21).

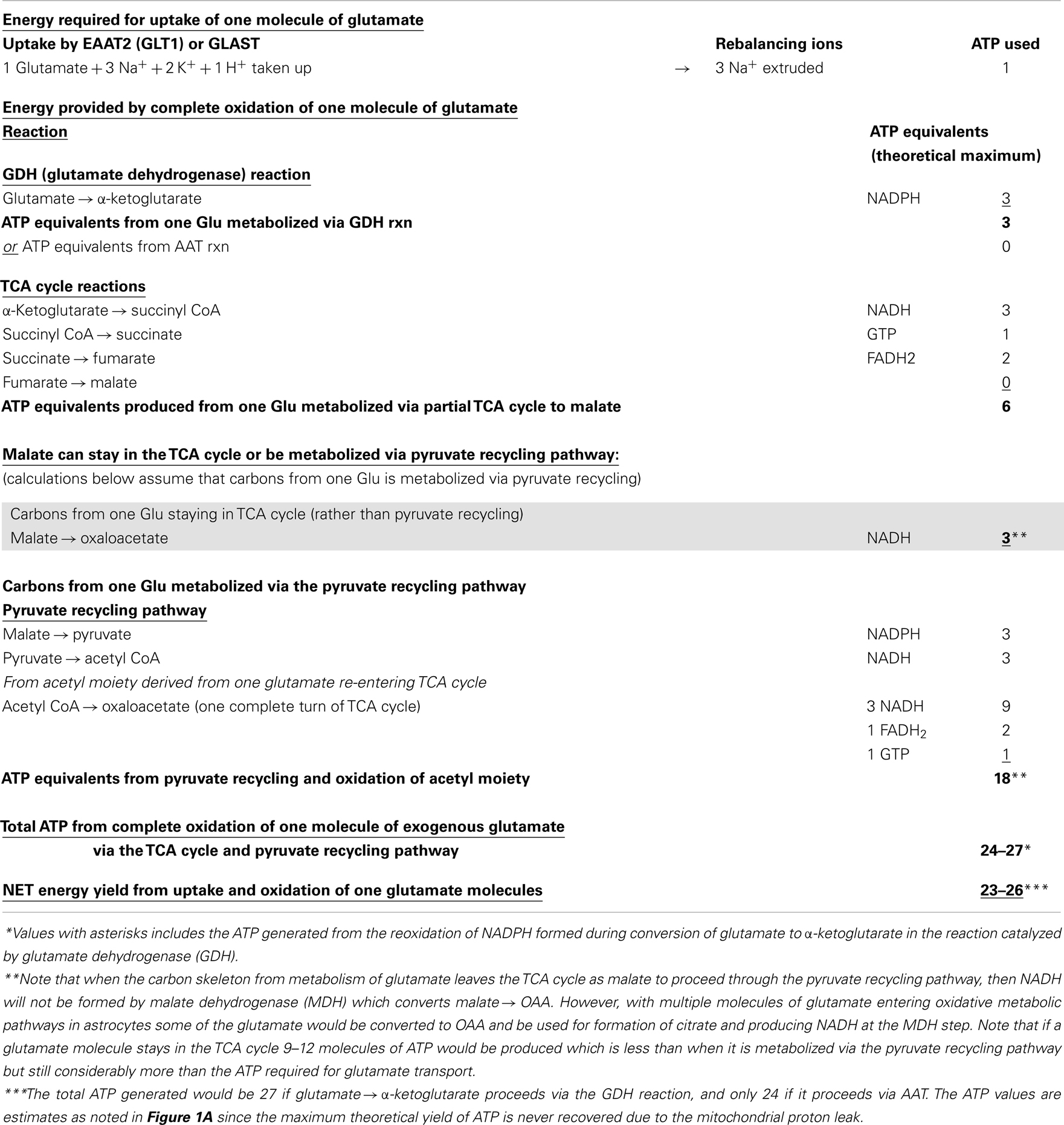

Figure 1A. Schematic diagram indicating the pathways of metabolism of exogenous glutamate taken up by astrocytes. The portion of the figure outlined with a dashed line shows transport of glutamate from the extracellular milieu. The oval depicts the astrocytic glutamate transporter GLT1/EAAT2 or GLAST; rectangle depicts Na+, K+-ATPase. Astrocytic glutamate can be converted to α-ketoglutarate by the energy producing enzyme glutamate dehydrogenase or via one of the transaminase enzymes (primarily via aspartate aminotransferase but also by BCAT and ALAT). α-Ketoglutarate formed from glutamate is metabolized via a partial TCA cycle to either malate or oxaloacetate. For the complete oxidation of glutamate to occur malate (or OAA) must leave the TCA cycle, be converted to pyruvate by malic enzyme, and then converted to acetyl CoA by pyruvate dehydrogenase. The acetyl CoA formed by these pyruvate recycling reactions re-enters the TCA cycle and is subsequently oxidized for energy. The dotted in the TCA cycle indicates that the NADH generated from the isocitrate dehydrogenase reaction would only be formed when the acetyl CoA formed from the pyruvate recycling pathway is metabolized via the TCA cycle because the initial entry of carbons α-KG at is subsequent to this step. The complete oxidation of one glutamate molecule can yield 24–27 ATP depending on whether the initial step in metabolism is via GDH or AAT. The ATP is estimated at ∼20 since the maximum theoretical yield of ATP is never recovered due to mitochondrial proton leak. [See Table 1 for reaction details and (B) for labeling pattern of metabolites labeled from the initial metabolism of [U-13C]glutamate and the labeling pattern from subsequent metabolism via the pyruvate recycling pathway and re-entry into the TCA cycle]. Abbreviations: Glu, glutamate; α-KG, α-ketoglutarate OAA, oxaloacetate; Asp, aspartate; GDH, glutamate dehydrogenase; AAT aspartate aminotransferase; BCAT, branched-chain aminotransferase; ALAT, alanine aminotransferase; KGDH, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase; ME, malic enzyme; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; GS, glutamine synthetase. BCAA, branched chain amino acid; BCKA, branched chain ketoacid.

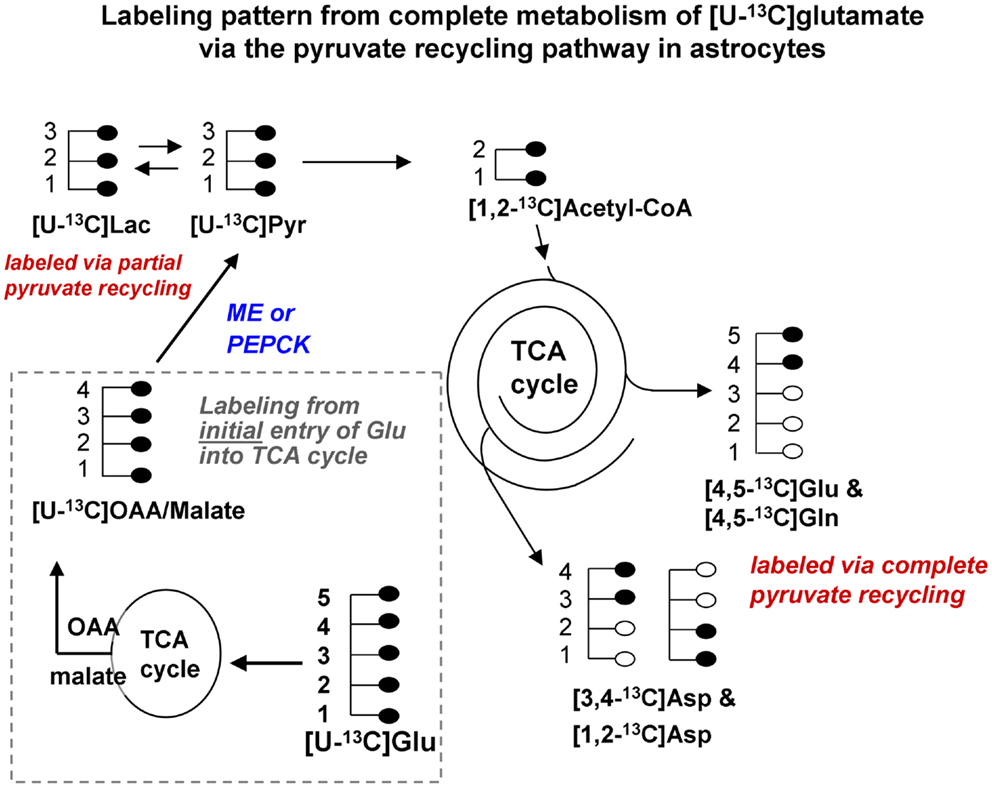

Figure 1B. Labeling pattern from the initial metabolism of [U-13C]glutamate and the labeling pattern from the complete oxidation of these glutamate carbons via the pyruvate recycling pathway and re-entry into the TCA cycle. Labeling from the initial entry of [U-13C]glutamate into the TCA cycle is shown inside the dotted line. Note that metabolites generated are also uniformly labeled in all carbons. [Note that any glutamine formed in the cytosol directly from [U-13C]glutamate would also be uniformly labeled [U-13C]glutamine; reaction not shown in this figure]. [U-13C]malate or OAA leaving the TCA cycle would be converted to [U-13C]pyruvate by malic enzyme or the combined action of PEPCK and pyruvate kinase, and would also give rise to [U-13C]lactate. The [U-13C]pyruvate can be converted to [1,2-13C]acetyl CoA which enters the TCA cycle for further oxidation. Any citrate formed from the condensation of the [1,2-13C]acetyl CoA with unlabeled oxaloacetate in the cycle would give rise to [4,5-13C]glutamate and glutamine, and also to both [1,2-13C]aspartate and [3,4-13C]aspartate. These partially labeled glutamate, glutamine, and aspartate molecules can be readily distinguished from the [U-13C]glutamate, glutamine, and aspartate by 13C-NMR spectroscopy. It is very likely that studies of pyruvate recycling from [U-13C]glutamate underestimate the amount of recycling taking place since any citrate formed from the condensation of [1,2-13C]acetyl CoA with [U-13C]OAA formed from the initial entry and metabolism of the glutamate into the TCA cycle give rise to [U-13C]glutamate which can not be distinguished from the precursor. Abbreviations: Glu, glutamate; Gln, glutamine; OAA, oxaloacetate; Asp, aspartate; Lac, lactate; Pyr, pyruvate; ME, malic enzyme; PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase.

Table 1. Energy produced in astrocytes from oxidation of one glutamate molecule in the TCA cycle and oxidation via the pyruvate recycling pathway.

It is well established that astrocytes can oxidize glucose and other substrates for energy including lactate, glutamate, glutamine, fatty acids, and the ketone bodies 3-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate (12, 17, 22–30). These substrate are actively oxidized for energy; however, glutamate is oxidized by astrocytes at a rate much higher than the other substrates. The oxidation of glutamate by astrocytes was initially determined with studies using radiolabeled 14C-glutamate (12, 30–32). However, the more recent use of 13C-glutamate and 13C-NMR spectroscopy has provided more complete information about the metabolic fate of glutamate in astrocytes. Sonnewald et al. (18) first reported that more of the label from glutamate metabolism was incorporated into lactate by astrocytes than was converted to glutamine. This key finding was initially considered controversial as it underscored that the glutamate-glutamine cycle is not stoichiometric since only a portion of the glutamate taken up by astrocytes was converted to glutamine. A key study by the McKenna and Sonnewald (29) groups demonstrated that when the exogenous glutamate concentration was increased from 0.1 to 0.5 mM the proportion of glutamate oxidized by the TCA cycle in astrocytes greatly increased and the percent converted to glutamine decreased. Reports from many groups clearly demonstrate (17, 29, 30, 33) that astrocytes have the capability to oxidize the concentrations of glutamate present in the synaptic cleft after depolarization of neurons (100 μM–1 mM) (4). Hertz and Hertz (17) noted that glutamate oxidation by astrocytes is as high as the anaplerotic rate of glutamate production suggesting that synthesis must be balanced by catabolism as glutamate does not readily exit the brain. A recent report by our group (11) showed that glutamate was oxidized by astrocytes at a rate higher than glucose, 3-hydroxybutyrate, glutamine, lactate, or malate, and that none of the other substrates could effectively decrease the oxidative metabolism of glutamate.

Data from several different types of studies provide evidence that suggests or demonstrates that glutamate oxidation occurs in astrocytes in vivo. These include in vivo microdialysis studies demonstrating oxidation of glutamate in the hippocampus of freely moving rats (34, 35), evidence from several groups documenting that the fine processes of astrocytes enveloping synaptic terminals contain abundant mitochondria (6) (and Tibor Kristian, unpublished), and transcriptome studies on astrocytes isolated from brain of adult rodents that document very high levels of transcripts for glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) and for enzymes of the TCA cycle (6).

Glutamate taken up by astrocytes can be converted to α-ketoglutarate by two reactions, either by transamination reactions or by the energy producing reaction of the enzyme GDH which is enriched in astrocytes (3, 6, 36, 37). Transamination occurs primarily by aspartate aminotransferase (AAT), but also readily takes place via either branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase (BCAT) or alanine aminotransferase (ALAT) (3, 38–40). Studies from our group and others demonstrate that the oxidative metabolism of exogenous glutamate taken up from the extracellular milieu proceeds primarily via GDH in astrocytes from rat brain [since it is relatively unaffected by the transaminase inhibitor aminooxyacetic acid, AOAA] (30, 41). The α-ketoglutarate formed from glutamate is metabolized for energy in the sequential reactions of the TCA cycle to the four carbon compound oxaloacetate (Figures 1A,B) and yielding the equivalent of nine ATP molecules in this process.

Studies using 13C-NMR spectroscopy have provided key insights into the metabolic fate of glutamate in astrocytes and information about the compartmentation of glutamate metabolism (28, 29, 42–44). Several groups have shown that the carbon skeleton of glutamate can enter the TCA cycle leading to labeling in aspartate and lactate (28, 29, 42–44). The incorporation of label from [U-13C]glutamate into [U-13C]lactate (see Figure 1B) and also into [1,2-13C]glutamate and glutamine and specifically labeled molecules of aspartate confirms that the carbon skeleton of glutamate can be metabolized via the pyruvate recycling pathway in astrocytes and reenter the TCA cycle. Thus, all carbons of the glutamate molecule can be completely oxidized for energy via the TCA cycle and pyruvate recycling pathway (45) (see Figure 1B).

The high rate of glutamate oxidation reported by several groups is consistent with the earlier findings of Hertz and Hertz (17) demonstrating that 100 μM glutamate supported O2 uptake by astrocytes as effectively as 7.5 mM glucose. Hertz also demonstrated that O2 uptake and respiration was significantly higher with the combination of glutamate + glucose than with either substrate alone (17). Data from several studies suggests that glucose may facilitate the uptake and oxidation of glutamate by astrocytes. McKenna et al. (30) showed that the presence of 1 mM pyruvate increased the rate glutamate oxidation by astrocytes, possibly by increasing transamination to α-ketoglutarate and metabolism via the TCA cycle in the presence of pyruvate. However, we did not find any effect of glucose or lactate on rate of 14CO2 production from [U-14C]glutamate in a recent study (11). In contrast, studies by some groups showed that glutamate uptake stimulated glycolysis in astrocytes; however, this has not been found by all groups (46, 47).

Substrate competition studies recently reported by our group demonstrated the robustness of glutamate use by astrocytes as none of the other substrates added, including glucose, had the ability to decrease the oxidation of glutamate (11). Hertz and Hertz (17) found higher respiration and O2 consumption when astrocytes were incubated in the presence of glutamate plus glucose and that the addition of glutamate spared glucose consumption. Earlier studies by Peng et al. (48) showed that added glutamate decreased the rate of glucose oxidation in astrocytes by 75%.

Recent reports from the Robinson lab (19, 20) demonstrate that glutamate uptake by astrocytes is tightly associated with a multi protein complex which includes the glial glutamate transporters, hexokinase and mitochondrial proteins suggesting that there is a mechanism in astrocytes that insures that a portion of the glutamate taken up is selectively delivered to mitochondria for oxidative energy metabolism. They demonstrated that the astrocyte glutamate transporter GLT1 can co-compartmentalize with hexokinase, other glycolytic enzymes, GDH, and mitochondria (20, 49). A report from the Robinson group in this special issue (49) suggesting that the enzyme GDH associates with the astrocyte glutamate transporters strengthens the evidence for the formation of a protein complex to facilitate the mitochondrial oxidation of glutamate.

Overall, there is compelling data from both in vitro and in vivo studies that oxidative metabolism of glutamate occurs in astrocytes and provides sufficient energy to pay for the cost of glutamate uptake from the synaptic cleft.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This work was supported in part by NIH grant HD016596. I thank Dr. Leif Hertz and Dr. Tiago Rodrigues for encouraging me to submit this manuscript and Dr. Susanna Scafidi for her advice regarding Table 1.

2. Kreft M, Bak LK, Waagepetersen HS, Schousboe A. Aspects of astrocyte energy metabolism, amino acid neurotransmitter homeostasis and metabolic compartmentation. ASN Neuro (2012) 4(3):e00086. doi:10.1042/AN20120007

3. McKenna MC. The glutamate-glutamine cycle is not stoichiometric: fates of glutamate in brain. J Neurosci Res (2007) 85:3347–58. doi:10.1002/jnr.21444

4. Bergles DE, Diamond JS, Jahr CE. Clearance of glutamate inside the synapse and beyond. Curr Opin Neurobiol (1999) 9:293–8. doi:10.1016/S0959-4388(99)80043-9

5. Matsui K, Jahr CE, Rubio ME. High-concentration rapid transients of glutamate mediate neural-glial communication via ectopic release. J Neurosci (2005) 25:7538–47. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1927-05.2005

6. Lovatt D, Sonnewald U, Waagepetersen HS, Schousboe A, He W, Lin JH, et al. The transcriptome and metabolic gene signature of protoplasmic astrocytes in the adult murine cortex. J Neurosci (2007) 27:12255–66. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3404-07.2007

7. Hertz L. Glutamate, a neurotransmitter – and so much more. A synopsis of Wierzba III. Neurochem Int (2006) 48:416–25. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2005.12.021

8. Gruetter R, Adriany G, Choi IY, Henry PG, Lei H, Oz G. Localized in vivo 13C NMR spectroscopy of the brain. NMR Biomed (2003) 16:313–38. doi:10.1002/nbm.841

9. Bluml S, Moreno-Torres A, Shic F, Nguy CH, Ross BD. Tricarboxylic acid cycle of glia in the in vivo human brain. NMR Biomed (2002) 15:1–5. doi:10.1002/nbm.725

10. Hertz L. Isotope-based quantitation of uptake, release, and metabolism of glutamate and glucose in cultured astrocytes. Methods Mol Biol (2012) 814:305–23. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-452-0_20

11. McKenna MC. Substrate competition studies demonstrate oxidative metabolism of glucose, glutamate, glutamine, lactate and 3-hydroxybutyrate in cortical astrocytes from rat brain. Neurochem Res (2012) 37:2613–26. doi:10.1007/s11064-012-0901-3

12. McKenna MC, Tildon JT, Stevenson JH, Boatright R, Huang S. Regulation of energy metabolism in synaptic terminals and cultured rat brain astrocytes: differences revealed using aminooxyacetate. Dev Neurosci (1993) 15:320–9. doi:10.1159/000111351

13. Swanson RA, Benington JH. Astrocyte glucose metabolism under normal and pathological conditions in vitro. Dev Neurosci (1996) 18:515–21. doi:10.1159/000111448

14. Waagepetersen HS, Bakken IJ, Larsson OM, Sonnewald U, Schousboe A. Comparison of lactate and glucose metabolism in cultured neocortical neurons and astrocytes using 13C-NMR spectroscopy. Dev Neurosci (1998) 20:310–20. doi:10.1159/000017326

15. Zwingmann C, Leibfritz D. Regulation of glial metabolism studied by 13C-NMR. NMR Biomed (2003) 16:370–99. doi:10.1002/nbm.850

16. Dienel GA. Astrocytic energetics during excitatory neurotransmission: what are contributions of glutamate oxidation and glycolysis? Neurochem Int (2013) 63:244–58. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2013.06.015

17. Hertz L, Hertz E. Cataplerotic TCA cycle flux determined as glutamate-sustained oxygen consumption in primary cultures of astrocytes. Neurochem Int (2003) 43:355–61. doi:10.1016/S0197-0186(03)00022-6

18. Sonnewald U, Westergaard N, Petersen SB, Unsgard G, Schousboe A. Metabolism of [U-13C]glutamate in astrocytes studied by 13C NMR spectroscopy: incorporation of more label into lactate than into glutamine demonstrates the importance of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. J Neurochem (1993) 61:1179–82. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03641.x

19. Bauer DE, Jackson JG, Genda EN, Montoya MM, Yudkoff M, Robinson MB. The glutamate transporter, GLAST, participates in a macromolecular complex that supports glutamate metabolism. Neurochem Int (2012) 61(4):566–74. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2012.01.013

20. Genda EN, Jackson JG, Sheldon AL, Locke SF, Greco TM, O’Donnell JC, et al. Co-compartmentalization of the astroglial glutamate transporter, GLT-1, with glycolytic enzymes and mitochondria. J Neurosci (2011) 31:18275–88. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3305-11.2011

21. Hertz L, Peng L, Dienel GA. Energy metabolism in astrocytes: high rate of oxidative metabolism and spatiotemporal dependence on glycolysis/glycogenolysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab (2007) 27:219–49. doi:10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600343

22. Lee WN, Edmond J, Bassilian S, Morrow JW. Mass isotopomer study of glutamine oxidation and synthesis in primary culture of astrocytes. Dev Neurosci (1996) 18:469–77. doi:10.1159/000111442

23. Edmond J, Robbins RA, Bergstrom JD, Cole RA, de Vellis J. Capacity for substrate utilization in oxidative metabolism by neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes from developing brain in primary culture. J Neurosci Res (1987) 18:551–61. doi:10.1002/jnr.490180407

24. Sonnewald U, Westergaard N, Hassel B, Muller TB, Unsgard G, Fonnum F, et al. NMR spectroscopic studies of 13C acetate and 13C glucose metabolism in neocortical astrocytes: evidence for mitochondrial heterogeneity. Dev Neurosci (1993) 15:351–8. doi:10.1159/000111355

25. Fitzpatrick SM, Cooper AJ, Hertz L. Effects of ammonia and beta-methylene-DL-aspartate on the oxidation of glucose and pyruvate by neurons and astrocytes in primary culture. J Neurochem (1988) 51:1197–203. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb03087.x

26. Yu AC, Fisher TE, Hertz E, Tildon JT, Schousboe A, Hertz L. Metabolic fate of [14C]-glutamine in mouse cerebral neurons in primary cultures. J Neurosci Res (1984) 11:351–7. doi:10.1002/jnr.490110403

27. Yudkoff M, Nissim I, Hummeler K, Medow M, Pleasure D. Utilization of [15N]glutamate by cultured astrocytes. Biochem J (1986) 234:185–92.

28. McKenna MC. Glutamate metabolism in primary cultures of rat brain astrocytes: rationale and initial efforts toward developing a compartmental model. In: Novotny JA, Green MH, Boston RC, editors. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology (Vol. 537) Mathematical Modeling in Nutrition and the Health Sciences. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers (2003). p. 317–41

29. McKenna MC, Sonnewald U, Huang X, Stevenson J, Zielke HR. Exogenous glutamate concentration regulates the metabolic fate of glutamate in astrocytes. J Neurochem (1996) 66:386–93. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66010386.x

30. McKenna MC, Tildon JT, Stevenson JH, Huang X. New insights into the compartmentation of glutamate and glutamine in cultured rat brain astrocytes. Dev Neurosci (1996) 18:380–90. doi:10.1159/000111431

31. Farinelli SE, Nicklas WJ. Glutamate metabolism in rat cortical astrocyte cultures. J Neurochem (1992) 58:1905–15. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10068.x

32. Zielke HR, Tildon JT, Landry ME, Max SR. Effect of 8-bromo-cAMP and dexamethasone on glutamate metabolism in rat astrocytes. Neurochem Res (1990) 15:1115–22. doi:10.1007/BF01101713

33. Hertz L, Drejer J, Schousboe A. Energy metabolism in glutamatergic neurons, GABAergic neurons and astrocytes in primary cultures. Neurochem Res (1988) 13:605–10. doi:10.1007/BF00973275

34. Zielke HR, Zielke CL, Baab PJ, Tildon JT. Effect of fluorocitrate on cerebral oxidation of lactate and glucose in freely moving rats. J Neurochem (2007) 101:9–16. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04335.x

35. Huang Y, Zielke CL, Tildon JT, Zielke HR. Monitoring in vivo oxidation of 14C-labelled substrates to 14CO2 by brain microdialysis. Dev Neurosci (1993) 15:233–9. doi:10.1159/000111339

36. Zaganas I, Waagepetersen HS, Georgopoulos P, Sonnewald U, Plaitakis A, Schousboe A. Differential expression of glutamate dehydrogenase in cultured neurons and astrocytes from mouse cerebellum and cerebral cortex. J Neurosci Res (2001) 66:909–13. doi:10.1002/jnr.10058

37. Zaganas I, Spanaki C, Plaitakis A. Expression of human GLUD2 glutamate dehydrogenase in human tissues: functional implications. Neurochem Int (2012) 61:455–62. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2012.06.007

38. Cole JT, Sweatt AJ, Hutson SM. Expression of mitochondrial branched-chain aminotransferase and alpha-keto-acid dehydrogenase in rat brain: implications for neurotransmitter metabolism. Front Neuroanat (2012) 6:18. doi:10.3389/fnana.2012.00018

39. Garcia-Espinosa MA, Wallin R, Hutson SM, Sweatt AJ. Widespread neuronal expression of branched-chain aminotransferase in the CNS: implications for leucine/glutamate metabolism and for signaling by amino acids. J Neurochem (2007) 100:1458–68. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04332.x

40. Bixel M, Shimomura Y, Hutson S, Hamprecht B. Distribution of key enzymes of branched-chain amino acid metabolism in glial and neuronal cells in culture. J Histochem Cytochem (2001) 49:407–18. doi:10.1177/002215540104900314

41. Westergaard N, Drejer J, Schousboe A, Sonnewald U. Evaluation of the importance of transamination versus deamination in astrocytic metabolism of [U-13C]glutamate. Glia (1996) 17:160–8. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199606)17:2<160::AID-GLIA7>3.3.CO;2-S

42. Waagepetersen HS, Qu H, Hertz L, Sonnewald U, Schousboe A. Demonstration of pyruvate recycling in primary cultures of neocortical astrocytes but not in neurons. Neurochem Res (2002) 27:1431–7. doi:10.1023/A:1021636102735

43. Olstad E, Olsen GM, Qu H, Sonnewald U. Pyruvate recycling in cultured neurons from cerebellum. J Neurosci Res (2007) 85:3318–25. doi:10.1002/jnr.21208

44. Sonnewald U, Westergaard N, Jones P, Taylor A, Bachelard HS, Schousboe A. Metabolism of [U-13C5] glutamine in cultured astrocytes studied by NMR spectroscopy: first evidence of astrocytic pyruvate recycling. J Neurochem (1996) 67:2566–72. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67062566.x

45. McKenna MC, Dienel GA, Waagepetersen HS, Schousboe A, Sonnewald U. Energy metabolism of the brain. In: Brady S, Price D, Siegal G. editors. Basic Neurochemistry (Vol. 8). Waltham: Academic Press (2012). p. 200–31.

46. Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ. Excitatory amino acids stimulate aerobic glycolysis in astrocytes via an activation of the Na+/K+ ATPase. Dev Neurosci (1996) 18:336–42. doi:10.1159/000111426

47. Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ. Glutamate uptake into astrocytes stimulates aerobic glycolysis: a mechanism coupling neuronal activity to glucose utilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1994) 91:10625–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.22.10625

48. Abe T, Takahashi S, Suzuki N. Oxidative metabolism in cultured rat astroglia: effects of reducing the glucose concentration in the culture medium and of D-aspartate or potassium stimulation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab (2006) 26:153–60. doi:10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600175

Keywords: glutamate, astrocytes, oxidative metabolism, glutamate dehydrogenase, pyruvate recycling pathway

Citation: McKenna MC (2013) Glutamate pays its own way in astrocytes. Front. Endocrinol. 4:191. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00191

Received: 16 October 2013; Accepted: 27 November 2013;

Published online: 16 December 2013.

Edited by:

Leif Hertz, China Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Leif Hertz, China Medical University, ChinaCopyright: © 2013 McKenna. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mary C. McKenna, Department of Pediatrics and Program in Neuroscience, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 655 West Baltimore Street, Room 13-019 BRB, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA e-mail:bW1ja2VubmFAdW1hcnlsYW5kLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.