- 1Research Department, Schulich School of Music, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 2Sir Zelman Cowen School of Music and Performance, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

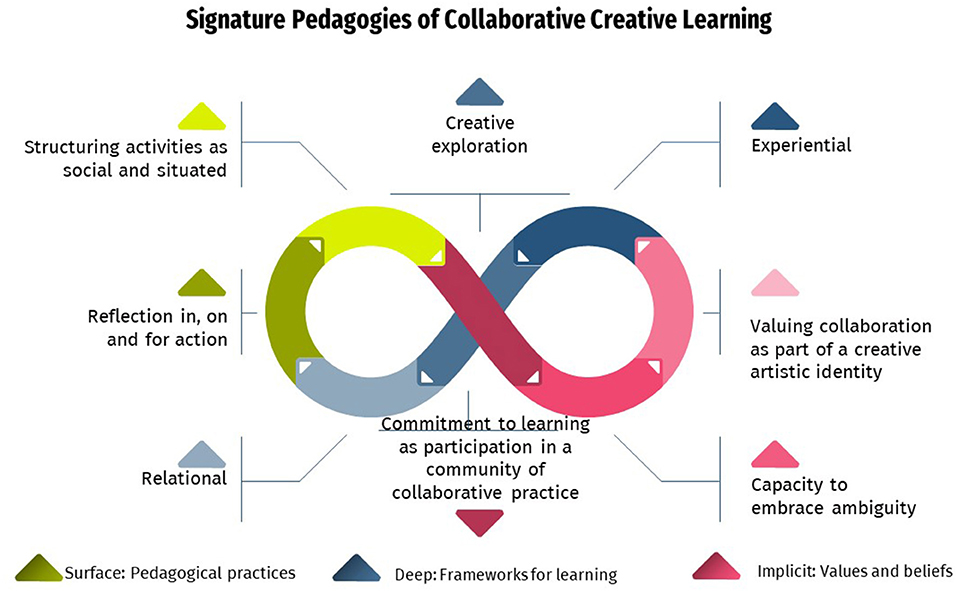

Recent debates concerned with Western music performance training have grappled with the question of what kind of education and training will best equip music students to navigate an increasingly dynamic and complex professional environment. Increasingly, attention has turned to the role of collaborative creativity and how collaborative, creative skills can be nurtured. Therefore, this paper interrogates the signature pedagogies of collaborative creative learning in advanced music training, education and professional development. Two research questions were addressed: 1) how can creative collaboration in advanced music training, education and professional development be understood through the lens of signature pedagogies; and 2) what are the core values that underpin signature pedagogies of collaborative creativity in advanced music training, education and professional development. A meta-synthesis of relevant qualitative research published since 2000 was carried out. Ten studies were retained. At the implicit level of signature pedagogies of collaborative creativity, three third-order constructs included a commitment to learning as participation in a community of collaborative practice, valuing collaboration in a creative artistic identity, and the capacity to embrace ambiguity. A further three third-order constructs – relational, experiential and creative exploration - comprised the deep level of pedagogical principles. At the surface level, signature pedagogical practices were structured as social and situated, while reflection in, on and for action was at the core of collaborative, creative pedagogical practices.

Introduction

Recent debates concerned with Western music performance training have grappled with the question of what kind of education and training will best equip music students to navigate an increasingly dynamic and complex professional environment (Gaunt et al., 2021). While the predominant master-apprentice model has been widely discussed and critiqued (e.g., Creech and Gaunt, 2012; Daniel and Parkes, 2017), more recently attention has turned to creative collaboration as being essential for professional training (Barrett et al., 2021), with a particular focus on the fundamental role of collaborative ensemble experiences within advanced music education (Gaunt and Treacy, 2020). For example, music students develop expertise in collaborative small and large ensemble performance (bands, chamber groups, orchestras, choirs), as well as in the context of collaborative creative work in community contexts, between composers and performers, between performers and recording engineers, and within interdisciplinary contexts involving (for example) dance, opera, visual arts or cinematography. Questions have therefore emerged concerning the pedagogies (e.g., the facilitation of learning and the approaches or strategies that support learning) that can frame and facilitate collaborative creative learning in these contexts.

Theoretical conceptualisations of collaborative creative learning are informed by a view of creativity as social, communicative and/or distributed (Barrett, 2014; Glǎveanu, 2014). From this perspective, creativity is seen as a social construct – whereby creative acts are joint endeavors comprised of ‘persons, processes, practices, places and ecologies that support collaborative creative thought and practice’ (Barrett, 2014, p. 3). John-Steiner (2000) paired this view of creativity with collaboration, proposing that creative collaboration may be distributed (occurring in shared thought communities), complementary (where knowledge, expertise, roles or individual characteristics partner in complementary ways in the service of shared goals), family (where collaboration is shaped by companionship, a sense of belonging and mutuality, and where roles and responsibilities are shared across tasks and may shift over time), or integrative (where joint endeavors effect transformative change) (John-Steiner, 2000). Crucially, “collaborative creativity exceeds collaborative knowledge construction, as something novel to the surrounding community has to be created” (Hämäläinen and Vähäsantanen, 2011, p. 174).

Over the past decade creative and collaborative learning pedagogies have become a focus for higher music education (see Gaunt and Westerlund, 2013; Gies and Sætre, 2019). This has been propelled in part by a changing professional landscape where musicians increasingly find themselves in potentially collaborative roles and interdisciplinary contexts requiring creative approaches (Gaunt and Treacy, 2020). For example, attention has turned to the value of improvisation as mindset, with Kleinmintz et al. (2014, p. 1) reporting that the “deliberate practice of improvisation may have a releasing effect on creativity,” with implications for decisions concerning the emphasis attaching to improvisatory pedagogical practices in advanced musical training. Notwithstanding many arguments in favor of collaborative learning as a form of professional preparation, others have cautioned that students may encounter a disjuncture between collaborative pedagogies and professional disciplinary practices that remain resistant to collaborative approaches (Christophersen, 2013).

Several researchers have explored and piloted innovative pedagogies that challenge the traditional apprenticeship model associated with instrumental teaching and learning (e.g., Rakena, 2016; Treacy and Gaunt, 2021; Zhukov and Sætre, 2022). For example, Treacy and Gaunt (2021) explored the role of reflection in making explicit artistic values, traditions, practices and aspirations. Their exploratory interview study with music ensemble instructors and other higher education arts professors suggested that reflective dialogue was “potentially driving creativity and generating new knowledge and ensemble practices … Interconnections between reflective practice and collective creativity [were] particularly important for supporting teachers and students in expanding their professionalism” (p. 498).

Beyond these previous studies, there has been little analysis and synthesis of the pedagogies that underpin and characterize the specific phenomenon of creative collaboration in advanced music education and training. This paper addresses that gap with a meta-synthesis of qualitative empirical studies specifically concerned with collaborative creative learning in higher music education and professional music training, framed by the theoretical idea of signature pedagogies (Shulman, 2005).

Background

Signature Pedagogies

The term “signature pedagogy” was coined by Shulman (2005), referring to the characteristic ways of learning and teaching that connect professional education or training with professional practice within specific disciplinary contexts. Signature pedagogies reveal the heart of a discipline, encompassing its culture, ethos, and particular “ways” of approaching knowledge creation. Shulman conceptualized signature pedagogies as the conduit between professions and professional training or education, functioning as the operationalization of discipline-specific epistemological (what counts as knowledge) and ontological (how knowledge becomes known) positionality. From this perspective, a discipline's signature pedagogies may be understood as a “microcosm of the wider discipline—including its assumptions and biases” (McLain, 2021, np).

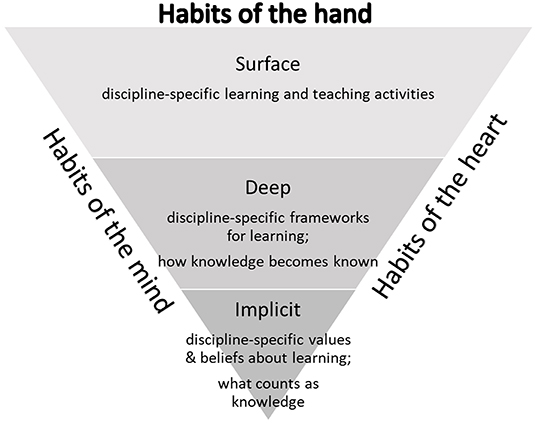

Signature pedagogies, according to Shulman, have a temporal dimension, in that specific phases of professional education may be associated with distinctive (and different) signature pedagogies. Signature pedagogies are also thought to be multidimensional, concerned with training habits of the mind (how to think), habits of the hand (how to perform) and habits of the heart (how to behave with professional integrity). Finally, signature pedagogies are multi-layered. At the most profound implicit level may be found the values, beliefs or moral codes that reside at the foundation of disciplinary ways of thinking, performing and behaving. At a mid-level (labeled the deep level by Shulman) characteristic frameworks and principles for learning and teaching are found, while at the surface level are specific pedagogical practices The relationship between these three levels provides an overarching coherence whereby professional values and beliefs are made transparent through orientations to learning and teaching and via specific activities that occupy learners and teachers in particular disciplines (Figure 1).

Shulman emphasized the value of well-established and enduring signature pedagogies – whereby predictable and well-understood frameworks for learning could free the learners and their teachers to focus on learning complex skills and knowledge, without having to think about how the learning could be framed. Notwithstanding this, Shulman also acknowledged the danger of rigid and repetitive ways of learning and teaching that risk perpetuating practices that have ceased to be relevant within a changing professional landscape. This apparent tension – between consistency and coherence on the one hand and responsiveness and flexibility on the other – is reflected in Shulman's model, whereby signature pedagogies involve embracing uncertainty and ambiguity. In this vein, he highlighted that the professions involved student performance of their professional roles, thus introducing dimensions of unpredictability and context-dependence (i.e., when students “perform” their roles), accountability (i.e., students are accountable to their peers, or “co-performers”) and visibility (i.e., in the enactment of their professional roles, students become both visible and vulnerable). As Haynie et al. (2012, p. 7) have stated, “developing signature pedagogies in the professions might change as the nature of the professions shift and morph and as practitioners in the fields debate values.”

Applications of the Signature Pedagogy Framework in Creative and Collaborative Arts Disciplines

Since the publication of Shulman's seminal work on signature pedagogies (2005), the concept has been applied in several disciplinary contexts (see Gurung et al., 2009; Chick et al., 2012) including the arts. For example, the idea of signature pedagogies has framed research and theoretical discussions concerned with architecture and design (Crowther, 2013; Caldwell et al., 2016; McLain, 2021), languages (Galina, 2017), literary studies (Heinert, 2017; Heinert and Chick, 2017; Clapp et al., 2021), dance (Kearns, 2017), theater (Kornetsky, 2017), visual arts (Sims and Shreeve, 2012; Motley, 2017) and music (Hastings, 2017; Love and Barrett, 2019).

Much of the previous work concerned with signature pedagogies in the arts has theorized the pedagogical role and purpose of “critique,” defined in the context of theater studies as “the process of giving feedback (first oral and sometimes written) to a performer immediately after the performance ends” (Kornetsky, 2017, p. 243). Critique — practiced as “questioning, listening, and providing clear reasons for active choices” — provides the structure whereby theater students learn to justify their own performance approaches, learn to think critically about others' performances, and in so doing learn to “use the language of the discipline,” applying this to artistic and aesthetic processes and choices (Kornetsky, 2017, p. 243). Likewise, in the context of literary studies Heinert (2017) and Heinert and Chick (2017) proposed that implicit values and beliefs about literary significance — including complexity, ambiguity and the multiplicity of meaning — were cultivated through modeling the habits of critique, articulated through pedagogies such as conversation, debate and questioning.

This concept of “critique” as a signature pedagogy that reveals implicit values has emerged as one prominent facet of signature pedagogies in other arts disciplines. For example, critique coupled with consultation was identified as a signature pedagogy in the visual arts (Gordon Cohen, 2013). While critique (a deep structure) is described as a formal framework for giving and receiving feedback (a surface structure), Gordon Cohen describes consultation as a constructive process (a deep structure) whereby teachers and students engage in iterative dialogue (a surface structure) about the student's artistic development. Both critique and consultation in turn may reveal the implicit beliefs and values that shape the professional ethics of interaction, approaches to subject matter, conceptual development and even technical skills.

Critique is similarly theorized as being the core signature pedagogy in dance education (Kearns, 2017). However, Kearns highlights the “major pedagogical shift in dance” that has had implications for the nature of critique. In other words, while critique has remained as a deep structure, the implicit values that it reveals have shifted (now privileging “dancers as participants”), and so too have the surface-level pedagogical practices shifted from hierarchical master-apprentice approaches to those which now encompass “complex and meaningful discussions about dance” (Kearns, 2017, p. 267–268).

In graphic design education, critique has been characterized both as a process and as a tool that links the implicit, deep and surface levels of a signature pedagogy. Accordingly, Motley (2017, p. 231) defined critique as a “structured, student-focused learning activity that serves as an assessment and a generator of critical feedback, clarifying the discipline's objectives and values and facilitating students' understanding of how professionals achieve their goals.” In this vein, an empirical investigation of the experience of critique as a signature pedagogy in design education was reported by Schrand and Eliason (2012). The researchers were interested in how the pedagogical practice of critique in design disciplines, defined as “the formal and public delivery of feedback to students about their work” (p. 51), was experienced in comparison with other feedback practices in the liberal arts which typically were text-based, private and solitary. Notwithstanding the potential for public critique to function as a ritualistic activity that “dramatiz[es] the symbolic [and implicit] power that the instructors and professionals wield over the students hoping to enter the field” (p. 56), the study suggested that the design studio fostered a collaborative community where critique took place within trusting relationships.

Peer critique, somewhat akin to the formative “preliminary critique” discussed by Schrand and Eliason (2012) has furthermore been identified as a signature pedagogical practice within the context of creative writing workshops (Stukenberg, 2017). This practice of giving and receiving peer feedback takes place within workshop settings, which provide both “occasion (including deadlines) and audience” (p. 278). Just as in the dance context, through the process of creation and critique within a collaborative environment (in this case, writing, having their work read, and engaging in deep discussion about their own and others' emergent creative work) students “develop artistic appreciation through workshop, honing their tastes and preferences through contrast with their peers, and begin to learn the professional skills of receiving and deciding how to use feedback” (p. 278).

In accordance with the idea of “workshop” as the “vessel” within which critique could take place in creative writing (Stukenberg, 2017), Crowther (2013) conceptualized the design “studio” as a signature pedagogical structure. Within those spaces (i.e., workshop, or studio) implicit values concerned with the nature of expertise and related experiential and problem-based learning may be articulated through “surface-level” pedagogical patterns. These surface pedagogical patterns pair various forms of media with learning activities (e.g., interactive forms of media paired with exploring and investigating; communicative forms paired with debating). The “studio” as a framework for signature pedagogies in art and design was investigated empirically by Shreeve et al. (2010); also discussed in Sims and Shreeve (2012), whose study comprised an analysis of 35 semi-structured interviews with art and design instructors. The “studio” was seen as fundamental – “a space of shared, prolonged, communal activity in which the process of making is visible and a focus for comment and debate by all who wander through” (p. 134). The results again revealed critique as a central pedagogical phenomenon within the “studio,” but this was characterized as student-centered, encouraging exploration, experimentation and uncertainty expressed as space for unforeseen or unimagined outcomes. Overall, signature pedagogies in these disciplines were fundamentally social and visible, being open to public scrutiny and audience engagement.

In the context of music, the idea of signature pedagogies has been applied to theorize the relationship between practice and performance (Hastings, 2017). Hastings argued that it is through methodical, systematic practice that fundamental musical understandings are both revealed and developed, thus linking the “practice mindset” to the “performance mindset.” In Hastings' theoretical model, self-critique and critique by teachers, coaches, peers and audience reside at the surface level of a signature pedagogy where the deep structure is the practice/performance mindset, which in turn is founded upon implicit values and beliefs about the nature of musical expertise and the pathways to expertise development.

One empirical case study in music (Love and Barrett, 2019) has employed Shulman's theoretical framework of signature pedagogies, in an interrogation of the training and development of composers participating in a professional orchestra workshop leading to public performance of their work. In this study, expert composers worked together with advanced composer-students in a five-day workshop that included individual lessons, orchestral rehearsals, orchestration lecture-demonstrations and master classes. While this study did not explicitly investigate collaborative learning, “community and collaborative aspects of the practice” (p. 564) were illuminated. Like Stukenberg's exploration of pedagogical spaces for creative writing, Love and Barrett identified the “workshop” as the “case” - a signature space for composition training. Here, cycles of performance and critique were framed by risk-taking, as student composers made themselves vulnerable, exposing their creative work to critique. Critique was embedded in practical apprenticeship (the surface level of finding “appropriate” ways of making creative ideas work, through guided modeling and dialogue), cognitive apprenticeship (the deep level of learning to think like a composer) and moral apprenticeship (the implicit level of behaving with integrity according to professional code among the musicians).

In summary, the idea of signature pedagogies, applied in creative arts disciplines, has highlighted process (critique), hinting at its collaborative potential within structures or spaces (e.g., workshop or studio) for creative work. Critique requires the artist to make themself vulnerable, often within a hierarchical power relationship. Critique, as well as the spaces within which it occurs, reveals the values that shape aesthetic choices and professional ethics, yet also provides a scaffold for creative work when practiced as collaborative dialogue, questioning and exploration.

While several authors have theorized the signature pedagogies that characterize collaborative and creative education and training in specific arts disciplines, there has been very little discussion or empirical research concerned explicitly with the signature pedagogies of creative collaboration in advanced music training, education and professional development. Therefore, in this paper, our objective is to carry out a meta-synthesis of empirical studies concerned with collaborative creative learning in music, in order to contribute to understandings of the signature pedagogies that shape and support development in musical creative collaboration. Our research questions are:

How can collaborative creativity in advanced music training, education and professional development be conceptualized through the lens of the surface, deep and implicit structures of signature pedagogies?

What are the core values that underpin signature pedagogies of collaborative creativity in advanced music training, education and professional development?

Methodology

This meta-synthesis follows as the second phase of a systematic review of empirical research concerned with collaborative creativity in music (reported in Barrett et al., 2021). Our goal was to synthesize the themes and interpretations emerging from previous research concerned with pedagogies of collaborative creative learning in advanced music training and education and to identify higher order constructs that encompassed the interpretations of research participants words and actions across a sub-set of studies identified in our systematic review (Barrett et al., 2021), concerned specifically with “collaborative creative learning … and the related phenomenon of qualitative transformations in understanding [that] emerge from systematic and sustained cooperation between students and teacher” (Barrett et al., 2021, p. 10).

Positioned within an interpretive paradigm, meta-synthesis is an holistic approach to developing high-level conceptualisations of a phenomenon via synthesis of multiple non-contradictory and complementary perspectives or interpretations (Jensen and Allen, 1996). The process of meta-synthesis begins with data retrieval and progresses through an interpretive process of describing, comparing and reciprocally translating findings across studies. Our approach was framed by guidelines proposed by Jensen and Allen (1996), whereby the interpretive process begins with reading individual texts and identifying themes as well as specific detail concerned with the phenomenon of interest. This is followed by establishing relationships among the texts through identification of shared language, metaphors or themes. Finally, consensus with regard to overarching synthesis of understandings is achieved through repeated reciprocal translation of themes across studies, leading to the identification of higher order concepts.

Our methodological approach was further refined in accordance with guidelines for meta-ethnography, a well-established approach to meta-synthesis of qualitative research (Cahill et al., 2018). In this vein, we adopted a dialectic approach in comparing, contrasting and reciprocally translating the interpretations found among the retained papers (the second order constructs) to generate synthesized third order constructs that could be said to represent the essence of signature pedagogies in collaborative creative learning, in the specific context of advanced music training and education.

Data Retrieval

The studies included in this meta-synthesis were initially identified through a systematic review of literature concerned with collaborative creativity in advanced music training and professional education, reported in Barrett et al. (2021). Briefly, the systematic review search protocol (reported in Barrett et al., 2021): (1) had focused on the key concepts of collaboration, creativity, music, and learning; (2) was carried out using Web of Science, ERIC and JSTOR databases; (3) was limited to peer-reviewed journal articles concerned with creative collaboration or collaborative creativity in professional training and practice in music performance, improvisation and/or composition; and 4) was published in English between 1990 and 2021. Twenty-four final retained papers in the original systematic review (reported in Barrett et al., 2021) were coded using the SPIDER tool developed by Cooke et al. (2012). This included a sub-set of eight studies where “collaborative creative learning” was the focus, including: Barrett (2006), Barrett and Gromko (2007), Blom (2012), Brinck (2017), de Bruin (2016), de Bruin et al. (2020), Dobson and Littleton (2016), and Virkkula (2016).

A further search was undertaken after publication of the systematic review, using the same search criteria as reported in Barrett et al. (2021), and limiting the year of publication to 2021. Two further studies were identified (Biasutti and Concina, 2021; de Bruin, 2021), making a total of ten papers to be included in our phase two meta-synthesis, reported in this paper.

The phenomena of interest, contexts and designs of the ten studies that formed the dataset for our meta-synthesis are set out in Table 1. Among the ten qualitative studies, eight carried out semi-structured interviews, five employed observational methods, three collected data in the form of reflective journals, one administered a questionnaire, and one collected audio recordings of activities. Approaches to analysis included thematic analysis (6), discourse analysis (1), content analysis (2) and interpretive phenomenological analysis (1). Theoretical frameworks included eminence theory of creative practice (Barrett, 2006); social constructivist perspectives (Barrett and Gromko, 2007; Dobson and Littleton, 2016); sociocultural theories of learning and creativity (de Bruin et al., 2020; Biasutti and Concina, 2021; de Bruin, 2021); community of practice (de Bruin, 2016; Virkkula, 2016; Brinck, 2017); and distributed collaboration (Blom, 2012).

Interpretive Synthesis

Our approach to interpretive synthesis comprised four steps. First, individual researchers extracted the principal themes and metaphors found in each individual research study and mapped those against the three criteria of Shulman's (2005) signature pedagogies – surface, deep and implicit structures. These thematic analyses of individual papers were then collated and through a dialogic process consensus was reached regarding the labeling and definitions of themes for each paper at each of the three levels. Secondly, we undertook a “horizontal analysis,” whereby relationships among the papers were identified through iterative research team discussions focused on the reciprocal translation of themes and metaphors across the research papers. Third, we undertook a “vertical analysis,” whereby thematic coding was traced through the three levels of the signature pedagogy framework, identifying the ways in which implicit level themes could be traced through the deep and surface levels, across the studies. Finally, the fourth step comprised repeated dialogue and revision until consensus was reached with regard to the third-order constructs and how these could be traced through the implicit, deep and surface levels of the signature pedagogies framework.

Findings

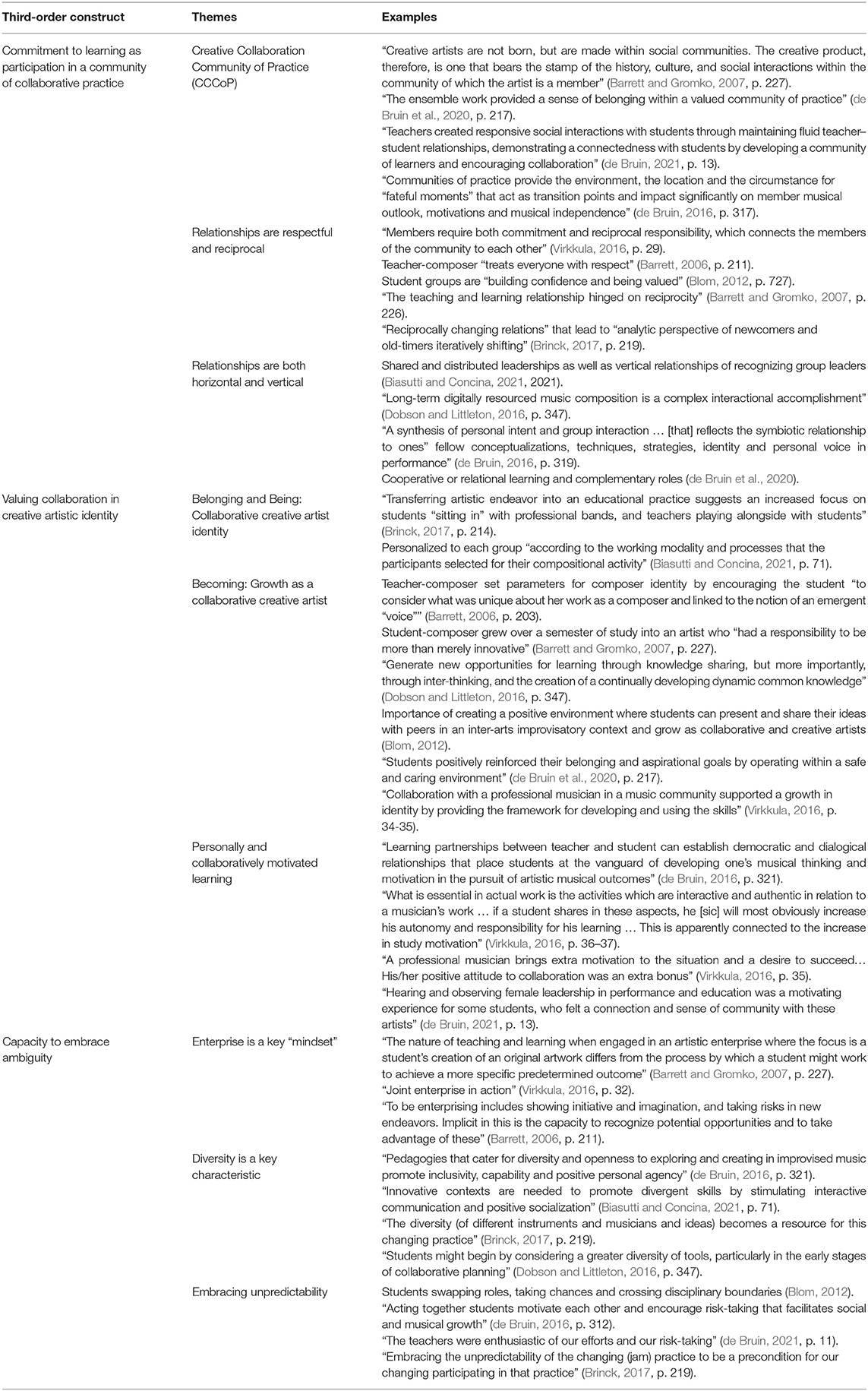

The process of interpretive synthesis revealed three ‘third-order constructs’ at each of the implicit and deep levels of the signature pedagogies, shared across all ten papers. The surface level of signature pedagogies (i.e., the specific activities that learners engage in with their instructors) was found to encompass two overarching third-order constructs uniting the ten papers. Findings from the ten studies of collaborative creative learning were tabulated under implicit, deep and surface structures, with the third-order constructs and their underlying themes accompanied by illustrative quotes (see Tables 2–4).

Implicit Structure

At the foundational, implicit level three third-order constructs were revealed, with each one encompassing three related themes (Table 2). A first foundational third-order construct was a commitment to learning as participation in a community of collaborative practice (CoCP). As discussed by Virkkula (2016) and further explored by de Bruin (2016) and de Bruin et al. (2020) in the context of situated learning among jazz students and professionals, creative and collaborative performance practice was thought to evolve within a community of musical practice, where it was shaped by relationships, shared purpose, and a commitment to exploration partnered with hegemonic practices that underpinned a professional standard. Within the CoCP, the values of respect and reciprocity were consistently evident. For example, Barrett and Gromko (2007, p. 214) highlight the idea of “thought communities” characterized by “mutual zones of proximal development” among composer students and teachers, while Blom (2012) described the values of mutual recognition and boundary crossing within a multi-disciplinary arts project. Similarly, Brinck (2017) noted that

“…reciprocally changing relations within the changing practice leads to such analytic perspectives of newcomers and old-timers iteratively shifting: At a moment when the guitar player burst into an energetic but very ambient solo I remember myself taken by surprise, calling for a radical adjustment of my playing. At that very moment I was the “newcomer” and the guitarist the “old-timer””. (p. 219)

The values of reciprocity and mutual respect did not preclude the idea that the CoCP could encompass horizontal as well as vertical leadership relationships. For example, Biasutti and Concina (2021) demonstrate how collaborative online composition activities were achieved by groups with different orientations to leadership, influenced by the “age, professional expertise and cultural background” (p. 70) of group members. While some groups adopted a top-down vertical approach with clear leaders and followers, others achieved the task through a horizontal, distributed model of leadership. However, as highlighted by de Bruin et al. (2020, p. 210), “a diversity of relationships can exist that foster growth via help for tasks and challenges, emotional support in daily activities, and companionship in shared activities.” Accordingly, whether the leadership style was predominantly horizontal or vertical, the creative task emerged from interaction patterns that were empathetic and sensitive to contrasting ideas. Overall, the signature pedagogies discussed across all of the ten papers were founded upon a commitment to “the apprenticeships of everyday music practices” (Brinck, 2017, p. 217) and a belief that learning is located within the “deep collective nature of human social practice” (Brinck, 2017, p. 221).

The second implicit-level third-order construct was concerned with the value accorded to collaboration as part of a creative artistic identity. For example, the practice of collaboration was privileged through situated creative activities where students experienced a sense of belonging and being collaborative creative artists, participating as equals alongside professionals (Brinck, 2017). In a similar vein, Virkkula (2016) demonstrated how popular and jazz music workshop-based opportunities for students to play alongside professional musicians supported growth in musical identity. Likewise, parameters for growth in relation to a creative, collaborative identity were established through a collaborative pedagogical relationship (Barrett, 2006). Personal and collaborative sources of motivation were furthermore found to drive the development of a creative artistic identity. For example Virkkula (2016) proposed a direct relationship between motivation and interactive approaches, autonomy and growth as a collaborative musician, while de Bruin et al. (2020) suggested that motivation emerged from the collaborative regulatory processes that formed a foundation for “cultivating a musical/creative identity” (p. 214) among students, their peers and teachers.

Finally, one further implicit-level third-order construct was the capacity to embrace ambiguity. Here, researchers described collaborative creative pedagogies that valued an enterprising mindset, whereby students were imaginative risk-takers (Barrett, 2006). In this vein, diversity and divergence from established norms were valued implicitly. For example, Dobson and Littleton (2016) discuss pedagogies of creative collaboration in composition, premised upon “possibility thinking” (p. 347) manifest as joint exploration and openness to diverse tools. In a similar vein, Brinck (2017) described signature pedagogies of creative and collaborative “jamming” and recording practice that necessitated a willingness to embrace the unpredictable, while likewise Blom (2012) described a multi-disciplinary performance arts collaborative project where a valued practice was exploratory boundary-crossing outside of students' own disciplinary norms.

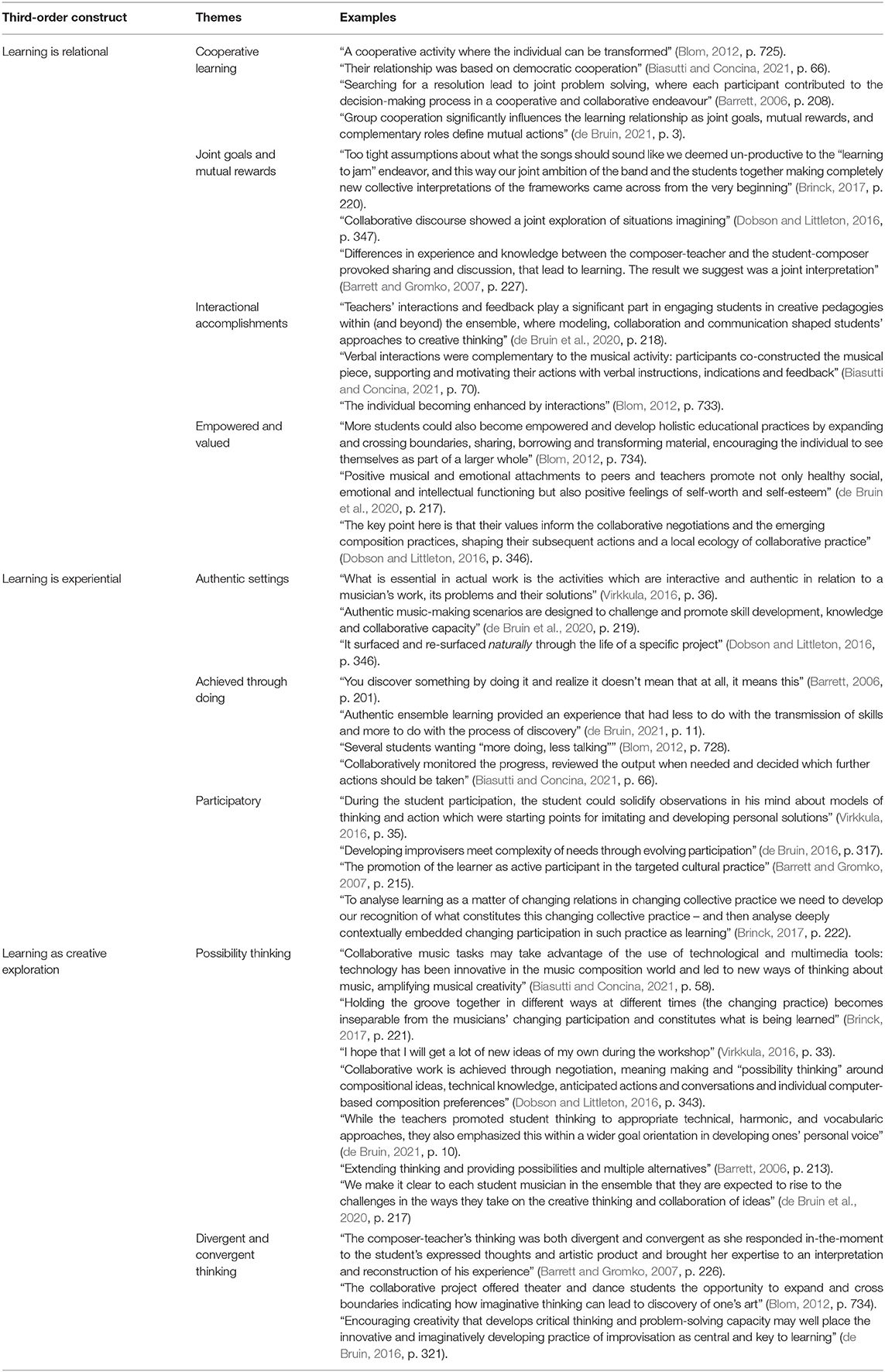

Deep Structure

The deep structure of signature pedagogies of collaborative creative learning was found to encompass three third-order constructs, each one encompassing a number of related themes (Table 3). First, the idea that learning is relational framed the ways in which learning and teaching was structured. Four underlying themes representing pedagogical principles underpinned this first third-order construct. The first of these concerned cooperative learning, referring to democratic structures that allowed scope for shared responsibility for problem-solving (Barrett, 2006). For example, de Bruin et al. (2020) reported that cooperative learning (interpreted here as proxy for “relational”) was manifest as a significant aspect of an ensemble experience where students, teachers and guest artists pursued a “professional standard” of “values and skills” in ways that involved “creative thinking and collaboration of ideas” (p. 217). As previously discussed, Biasutti and Concina (2021) described composition activities framed by “democratic cooperation” (p. 66) where roles were non-hierarchical, tasks were distributed equally and decisions were based on communicative exchanges and collaborative evaluation of ideas. Similarly, and with a focus on orientations to facilitation, de Bruin (2021) highlights the idea of “teachers as facilitators that democratize knowledge making and meaning rather than functioning as door-keepers of knowledge” (p. 2).

Cooperative learning was closely interrelated with the second theme concerned with relational learning, which focused on “joint goals and mutual rewards”. As de Bruin et al. (2020) explained in the context of jazz workshops that brought together students, teachers and guest artists, “joint cooperation between student cohorts, as well as those crafted between students and professionals in the ensemble, asserted the presence of joint goals, mutual rewards …” (p. 215). In a similar performance workshop context, Virkkula (2016) alludes to “joint effort” (p. 27), “joint enterprise” (p. 29), “joint-evaluation discussion” (p. 32) and “a clear goal [that] linked the students together and motivated them to work for a shared aim” (p. 32). Joint goals in turn were associated with mutual rewards “such as sharing of resources and belonging through social capital” (de Bruin, 2021, p. 3).

A third theme embedded in the third-order construct of “learning is relational” was concerned with learning as an interactional accomplishment. From this perspective, creative collaborative learning in the context of composition was a “long-term process of developing common knowledge … achieved through negotiation, meaning making … and conversations” (Dobson and Littleton, 2016, p. 340–343). Similarly, in the context of a multi-disciplinary arts collaboration, learning was framed by interactional skills, including “how to listen and respond appropriately, how to collaborate, how to communicate” – both socially and musically (Blom, 2012, p. 724). Finally, the fourth related theme was concerned with a framework for empowering and valuing learners. For example, Blom's (2012) multi-disciplinary arts setting was designed to empower students through expansive and holistic practices, while de Bruin et al. (2020) describe pedagogical “collaborative unions” characterized by a sense of belonging and enhanced self-worth, “sustained shared meanings, values and goals and higher-level aspirations” (p. 217).

Learning is experiential was identified as a second third-order construct at the deep level of signature pedagogies of collaborative creative learning. This comprised three themes identified as authentic settings, learning through doing, and participatory learning. Thus, collaborative creative learning was achieved within authentic scenarios or contexts that resembled the “real-life” professional settings inhabited by professional musicians (Virkkula, 2016), where new knowledge or skills emerged organically and naturally, as they would through professional practice (Dobson and Littleton, 2016). Learning within these authentic settings was therefore participatory and active (learning through doing). In this vein, Barrett (2006) noted in the context of composition training, transformative learning — involving changes in perception and deep insights — was framed by discovery through experimentation. The participatory facet of experiential learning was also tempered by the idea of an “evolution” in participatory patterns. From this perspective, Barrett and Gromko (2007) describe a process over time whereby a student-composer became progressively collaborative, for example as evidence by being more engaged in dialogue, initiative-taking and problem-solving. de Bruin (2016) similarly highlighted the evolving nature of participatory learning, whereby personal voice, identity, growth and development all emerged over time within an experiential and situated framework.

The final third-order construct at the deep level of signature pedagogies for collaborative creative learning was defined as “learning as creative exploration”. Here, a first underlying theme was “possibility thinking,” representing the capacity for “thinking outside of the box” and innovation in tools, spaces, activities or participation. For example, Biasutti and Concina (2021, p. 58) highlight innovative composition tools that have “led to new ways of thinking about music, amplifying musical creativity.” Thinking outside the box, though, existed in a complementary relationship with the communication of masterful standards, as demonstrated in Brinck's (2017) ethnographic study of jamming and recording popular music; here, “learning constitutes changing participation in changing practice …this telos depends on communication of masterful standards” (p. 221). Others have highlighted the interplay between ambiguity, flexibility and tradition; for example, de Bruin et al. (2020, p. 15) describes a pedagogical framework for collaborative improvisation as “ambiguous and open to multiple interpretations by both students and teachers … [this] challenges the importance of a prescribed canon of skills as a prerequisite for successful improvisation.” The juxtaposition of possibility thinking with the communication of masterful standards was also found to contribute to a process of developing a personal artistic voice, including “a personal melodic landscape, architecture and creative concepts” (de Bruin, 2021, p. 13).

A second and closely-related underlying theme was “divergent and convergent thinking.” While divergent thinking was similar to possibility thinking, involving exploring multiple solutions or innovative avenues of practice (Biasutti and Concina, 2021), convergent thinking was more focused on single, effective strategies. Both ways of creative thinking were found to be part of a collaborative pedagogy, as highlighted by Barrett and Gromko (2007, p. 226) who stated that “the composer-teacher's thinking was both divergent and convergent as she responded in-the-moment [to the student] … and brought her expertise to an interpretation and reconstruction of his experience”.

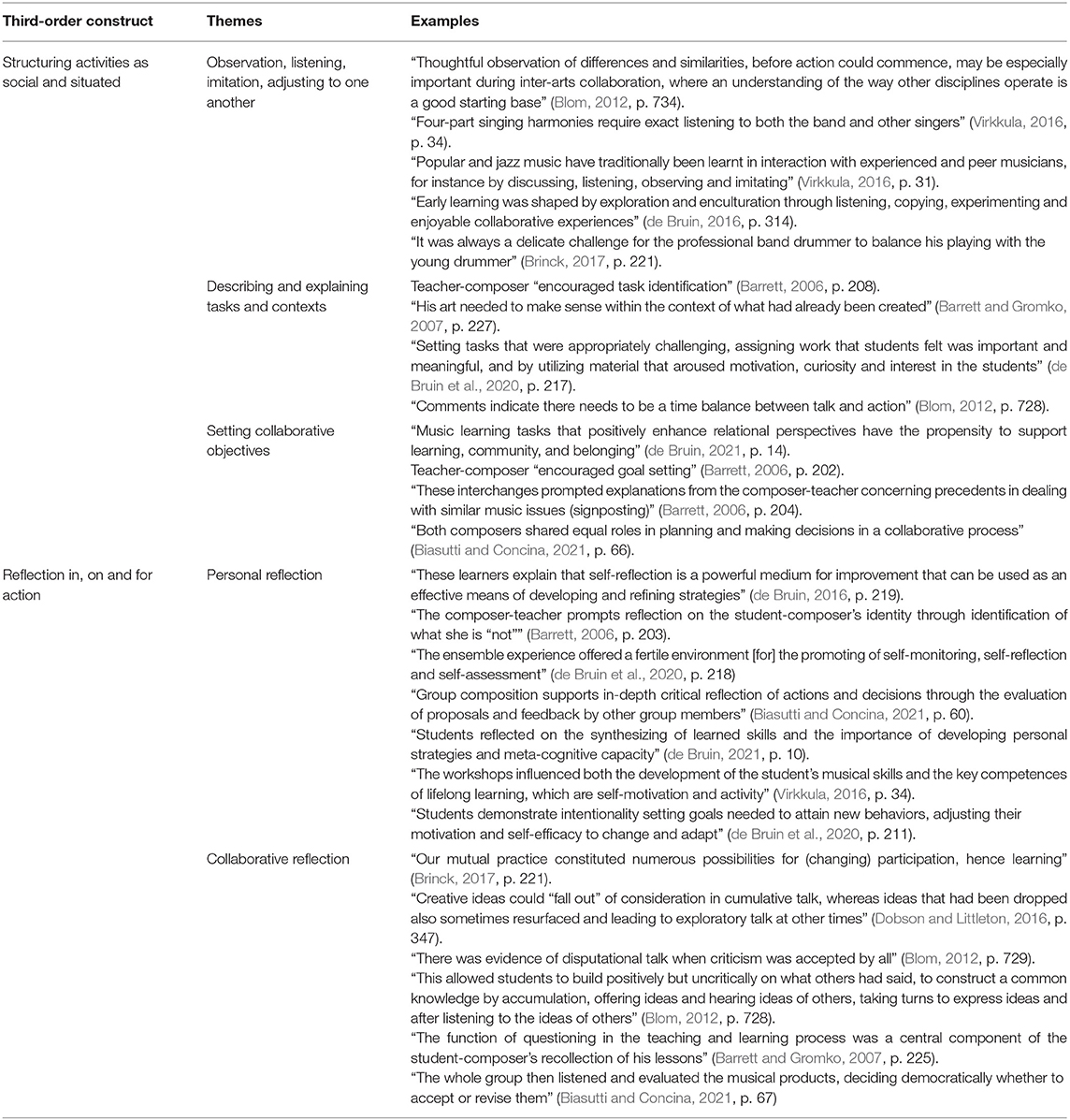

Surface Structure

The surface structure of signature pedagogies for collaborative creative learning was found to comprise two third-order constructs. The first of these was “structuring activities as social and situated”. Social and situated activities included a strong emphasis on reciprocal observations among students, teachers and professional colleagues, involving close listening, imitation and interpretation. For example, in workshop settings, students could “solidify observations in his [sic] mind about models of thinking and action which were starting points for imitating and developing personal solutions” (Virkkula, 2016, p. 35). Mutual observation was furthermore the basis for understanding and adjusting to one another's creative contribution and level (Brinck, 2017). Accordingly, Blom (2012, p. 734) noted that “thoughtful observation of differences and similarities, before action could commence, may be especially important during inter-arts collaboration.”

In addition, social and situated activities involved describing and explaining tasks and contexts. For example, a pedagogical strategy was to encourage students to identify, describe and explain tasks (Barrett, 2006), while Biasutti and Concina (2021, p. 66) highlight that peers made regular plans of work where they described anticipated activities, sharing “equal roles in planning and making decisions.” Surface-level pedagogies of collaborative creativity also involved activities organized with the intention of supporting the development of collaborative objectives. For example, Barrett (2006) highlighted strategies such as signposting specific musical examples as well as collaboration in setting specific goals.

One further third-order construct at the surface level of signature pedagogies of collaborative creative learning was “reflection in, on and for action,” comprising a dynamic interplay between personal reflection (the first underlying theme) and collective reflection (the second underlying theme). Personal reflection involved spontaneous improvisation emerging from tacit knowledge as well as self-monitoring (reflection in action), self-assessment (reflection on action) and personal goals (reflection for action). In some instances, student reflection and self-analysis was prompted by instructors as a strategy for “making intuitive knowledge explicit” (Barrett, 2006, p. 212). Blom (2012, p. 729) added that self-reflection was an essential precursor to “justifying and declaring your own ideas to a collaborator,” which in turn was an “essential part of professional life.” Therefore, learning was also organized in such a way as to promote collective, collaborative reflection. For example, a persistent strategy for creative work in collaborative, technology-mediated composition among undergraduate students was discussion and reflection, whereby “the composers' interthinking in dialogue engages them further in the process of building a local knowledge for creative action” (Dobson and Littleton, 2016, p. 342).

Discussion

Our aim in this paper was to interrogate the signature pedagogies of collaborative creative learning. To achieve this, we undertook a meta-synthesis of relevant qualitative research published since 2000, when John-Steiner's seminal work on creative collaboration was published. In addressing our first question concerned with how creative collaboration in music can be understood through the lens of surface, deep and implicit structures of signature pedagogies (Shulman, 2005), we began by analyzing each one of ten papers retained for the meta-synthesis, identifying themes that aligned with the surface (visible pedagogical practices), deep (pedagogical principles that frame learning) and implicit (the professional values that underpin learning) levels. We then undertook a reciprocal, horizontal process of analysis, considering the applicability of each theme (at each of the three levels) across the set of ten papers. In this way, we identified the higher order concepts (referred to as “third-order constructs”) that could be said to be representative of underlying shared themes.

As set out in the Findings section, three third-order constructs were found at the implicit level of signature pedagogies of collaborative creativity. These included a “commitment to learning as participation in a community of collaborative practice,” “valuing collaboration in a creative artistic identity,” and “the capacity to embrace ambiguity. A further three third-order constructs comprised the deep level of signature pedagogies, corresponding with the principles that guide and frame collaborative creative learning. At this deep level, our meta-synthesis suggested that learning was framed as relational, experiential and creative exploration. Finally, at the surface level, “habits of the hand”(Shulman, 2005, p. 59) – learning activities concerned with how to perform - were structured as social and situated, while, as Treacy and Gaunt (2021) suggested “habits of the mind” (learning how to think in disciplinary ways) were achieved through reflection in, on and for action.

Overall, at each of the implicit, deep and surface levels, signature pedagogies of collaborative creative learning were found to be closely aligned with authentic professional settings. In accordance with other disciplines such as literary studies (Heinert, 2017), theater studies (Kornetsky, 2017), visual arts (Gordon Cohen, 2013) and dance (Schrand and Eliason, 2012), authentic, experiential workshop settings that approximated or embedded students in professional practice functioned as the space where the implicit-level values were articulated through social and situated practices such as modeling, observation, discussion and improvisation. Likewise, the implicit values concerned with collaboration as part of growth in artistic identity, as well as a capacity to embrace ambiguity were reflected in the reflective practices of exploratory critique and consultation.

Our second research question corresponded to the implicit level of signature pedagogies, being concerned with identifying the core values that underpin signature pedagogies of creative collaboration in music. In accordance with the theory of situated learning in communities of practice (Lave and Wenger, 1991), signature pedagogies of creative collaboration reflected implicit beliefs concerned with learning as a relational and deeply contextual achievement, being shaped by characteristics of the artistic community (including its shared goals and focus) and social participation within that community.

Wenger (1998) discusses social learning through participation in terms of opening the possibilities for refinement of established practices, where collaborative exchange may be conceptualized as a process that involves “old-timers” as culture-bearers (collaborating within a context of privileging the disciplinary culture and its standards) in a participatory apprenticeship relationship with “newcomers.” Expanding on this idea, the findings of this interpretive synthesis suggested that creative collaborative learning was premised upon an iterative pedagogical process that navigated between horizontal and vertical power relationships, accompanied by potential tensions “between on the one hand desire for democratic exchange, and on the other hand belief in leadership emanating from heightened artistic credibility and charisma” (Gaunt and Treacy, 2020, p. 433) Therefore, the commitment to learning as participation within a community of collaborative practice also encompassed the potential for newcomers and old-timers to collaborate as “culture-builders” (building on established disciplinary practices and through improvisatory or exploratory approaches that tolerated disruption of known practices) or indeed as “culture-brokers” – in a collaborative relationship open to expanding disciplinary practices through crossing disciplinary or cultural boundaries (Willingham and Carruthers, 2018, pp. 609–610). In this vein, non-linear and reciprocal signature pedagogies provided a bridge between professional training and the exploratory, diverse and unpredictable nature of professional practice of collaborative creativity in music (Barrett et al., 2021).

Our meta-synthesis therefore suggested that signature pedagogies of collaborative creative learning provided a framework for newcomers and old-timers together to explore a space between improvisatory creative exploration on the one hand and the development of expertise framed by known professional standards on the other. When functioning well, pedagogies of collaborative creativity therefore offered the potential for a dynamic and fluid partnering of the communication of masterful standards (Brinck, 2017, p. 221) with possibility thinking (Barrett, 2006). Nevertheless, as Gaunt and Treacy (2020) highlight, collaborative settings also present potential tensions, for example concerned with one-way transmission of ideas vs. mutual listening, familiar vs risky practices, or conflict avoidance vs conflict as an opportunity for creative development. This point has been explored by other authors. For example, Christophersen (2013, p. 78) acknowledges that collaborative learning has great potential as an “open, inclusive and democratic” pedagogical space (as our model of signature pedagogies of collaborative creative learning would suggest), yet also cautions the limitations in conceptualizing this pedagogical orientation as a “bridge” to disciplinary practices. In this vein, Christophersen raises the question of “whether collaborative learning experiences in higher music education will help the students cope with the demands of specific work contexts and, for example, the direction and authority wielded by conductors, bandmasters, directors, producers, supervisors, principals and deans” (p.78). Similarly, Love and Barrett (2019) highlight the ways that creative learning in composition could be constrained in “real-life” professional contexts, for example through encounters with orchestral etiquette, protocols and performance conventions. In brief, the underlying premise of a pedagogy of collaborative creative learning is that learners and more knowledgeable others interact as “willing and accepting collaborators” (Christophersen, 2013, p. 83) – a pre-condition that we found to be largely absent in the literature we reviewed.

Our meta-synthesis reinforced the key importance of reflection in resolving these potential tensions. Strategies that supported this complementary intersection of improvisational practices with disciplinary standards included acknowledging interdependence, developing shared goals, engaging with co-regulation and accepting guidance toward collaborative solutions to creative problems.

Whether interacting in horizontal or vertical power relationships, a commitment to learning as participation in a community of collaborative practice was furthermore consistently underpinned by value attached to reciprocal and mutually respectful relationships, suggesting a dimension of moral apprenticeship, or “habits of the heart” (Shulman, 2005) associated with behaving with integrity and according to a professional code. Core values at the implicit level also included the value accorded to collaboration in the growth of creative artistic identities, which in turn was linked to the capacity to embrace ambiguity. These core values were reminiscent of the “habits of the mind” in the context of professional composer education (Love and Barrett, 2019), which centered around learning to think like a composer through a willingness to make oneself vulnerable, to take risks and to engage in critique.

Figure 2 represents this reciprocal and inter-connected nature of the three levels of signature pedagogies of collaborative creative learning. Our model adopts the idea of an infinity loop to represent the deeply embedded and non-hierarchical nature of signature pedagogies of collaborative creative learning.

As theorized by Shulman (2005), the implicit values of a signature pedagogy are revealed through the deep and surface levels. To explore this idea in relation to the signature pedagogies of collaborative creative learning, we interrogated the pathways by which the three implicit-level third-order constructs were manifest at the deep and surface levels. For example, a commitment to learning as participation in a community of collaborative creative practice was manifest in the deep-level framework for learning as being relational, and then further articulated in structured activities that were social and situated. Looked at conversely, social and situated activities (such as observation or mutual listening in a workshop setting) were framed within a relational, intersubjective space which in turn revealed a commitment to learning as participation in a community of collaborative creative practice. Similar reciprocal pathways were evident in relation to reflection in, on and for practice (surface-level pedagogical practice) which in turn revealed underlying pedagogical principles and artistic values and traditions (Treacy and Gaunt, 2021). Accordingly, pedagogical practices of reflection were framed by experiential, creative exploration (deep-level frameworks for learning) which in turn revealed the implicit-level values attached to the capacity to embrace ambiguity and collaboration as being integral to a creative artistic identity.

Conclusions

Based on a meta-synthesis of ten qualitative studies concerned with collaborative creative learning in higher music education, we have proposed a model of signature pedagogies that demonstrates deeply inter-connected pathways between implicit values, pedagogical principles and pedagogical practices. Previous research concerned with signature pedagogies in arts disciplines has tended to identify particular practices or frameworks at the surface or deep levels. Our new model, derived from a meta-synthesis of research concerned with signature pedagogies of collaborative creative learning in higher music education, identifies higher order concepts at each of the three levels, as well as demonstrating interrelationships across the multilayered signature pedagogies framework.

At the most foundational level, learning was found to be premised upon a commitment to learning as participation in a collaborative community of practice, where collaboration and the capacity to embrace ambiguity were valued highly as part of artistic identity. The principles and practices of pedagogy flowed from these underlying values, with collaborative creative learning thought to be necessarily relational, experiential and to be achieved through creative exploration. The practices that reflected these values and principles were social and situated, with reflection playing a vital role in resolving potential tensions concerned with interpersonal dynamics, purpose, structure or content. This model is derived from research carried out in western settings that included jazz improvisation, popular music jamming, recording studio practice and composition. In this sense, the findings of our meta-synthesis may be limited in applicability to the many other cultural and collaborative contexts that musicians inhabit. Nonetheless, within a higher education and professional music context where interdisciplinarity is increasingly valued, the lessons learnt from collaborative creative practices in specific disciplines and contexts may have valuable implications for pedagogical experience more broadly across higher music education and professional development.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by the Australian Research Council through the Discovery Grant Scheme Project DP200101943 (Barrett and Creech): Signature pedagogies of creative collaboration: Lessons for and from music.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Barrett, M. S. (2006). ‘Creative collaboration’, an ‘eminence’ study of teaching and learning in music composition. Psychol. Music 34, 195–218. doi: 10.1177/0305735606061852

Barrett, M. S. (2014). Collaborative Creative Thought and Practice in Music, 1st Edn. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315572635

Barrett, M. S., Creech, A., and Zhukov, K. (2021). Creative collaboration and collaborative creativity: a systematic literature review. Front. Psychol. 12, 713445. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713445

Barrett, M. S., and Gromko, J. E. (2007). Provoking the muse: a case study of teaching and learning in music composition. Psychol. Music 35, 213–230. doi: 10.1177/0305735607070305

Biasutti, M., and Concina, E. (2021). Online composition: Strategies and processes during collaborative electroacoustic composition. Br. J. Music Educ. 38, 58–73. doi: 10.1017/S0265051720000157

Blom, D. (2012). Inside the collaborative inter-arts improvisatory process: tertiary music students' perspectives. Psychol. Music 40, 720–737. doi: 10.1177/0305735611401127

Brinck, L. (2017). Jamming and learning: analysing changing collective practice of changing participation. Music Educ. Res. 19, 214–225. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2016.1257592

Cahill, M., Robinson, K., Pettigrew, J., Galvin, R., and Stanley, M. (2018). Qualitative synthesis: a guide to conducting a meta-ethnography. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 81, 129–137. doi: 10.1177/0308022617745016

Caldwell, G. A., Osborne, L., Mewburn, I., and Nottingham, A. (2016). Connecting the space between design and research: Explorations in participatory research supervision. Educ. Philos. Theory 48, 1352–1367. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2015.1111129

Chick, N. L., Haynie, A., and Gurung, R. A. R. (2012). Exploring More Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind (1st ed). Stylus Pub. Available online at: http://site.ebrary.com/id/10545758

Christophersen, C. (2013). “Perspectives on the dynamics of power within collaborative learning in higher music education,” in Collaborative Learning in Higher Music Education, eds Gaunt, H. and Westerlund, H. (Farnham, Surrey, UK: Ashgate), 77–85.

Clapp, J., De Coursey, M., Lee, S. W. S., and Li, K. (2021). ‘Something fruitful for all of us’: Social annotation as a signature pedagogy for literature education. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 20, 295–319. doi: 10.1177/1474022220915128

Cooke, A., Smith, D., and Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 22, 1435–1443. doi: 10.1177/1049732312452938

Creech, A., and Gaunt, H. (2012). “The changing face of individual instrumental tuition: value, purpose and potential,” in Oxford Handbook of Music Education, eds McPherson, G. and Welch, G. (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Crowther, P. (2013). Understanding the signature pedagogy of the design studio and the opportunities for its technological enhancement. J. Learn. Des. 6, 18–28. doi: 10.5204/jld.v6i3.155

Daniel, R., and Parkes, K. A. (2017). Music instrument teachers in higher education: an investigation of the key influences on how they teach in the studio. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 29, 33–46.

de Bruin, L. R. (2016). Journeys in jazz education: learning, collaboration and dialogue in communities of musical practice. Int. J. Community Music 9, 307–325. doi: 10.1386/ijcm.9.3.307_1

de Bruin, L. R. (2021). Collaborative learning experiences in the university jazz/creative music ensemble: Student perspectives on instructional communication. Psychology of Music. July 2021. doi: 10.1177/03057356211027651

de Bruin, L. R., Williamson, P., and Wilson, E. (2020). Apprenticing the jazz performer through ensemble collaboration: a qualitative enquiry. Int. J. Music Educ. 38, 208–225. doi: 10.1177/0255761419887209

Dobson, E., and Littleton, K. (2016). Digital technologies and the mediation of undergraduate students' collaborative music compositional practices. Learn. Media Technol. 41, 330–350. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2015.1047850

Galina, B. J. (2017). Whither critique in the world language department? Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 16, 305–319. doi: 10.1177/1474022216652769

Gaunt, H., Lopez-Iniguez, G., and Creech, A. (2021). “Musical engagement in one-to-one contexts,” In Routledge International Handbook of Music Psychology in Education and the Community, eds Creech, A., Hughes, D., and Hallam, S. (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge), 335–351.

Gaunt, H., and Treacy, D. S. (2020). Ensemble practices in the arts: a reflective matrix to enhance team work and collaborative learning in higher education. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 19, 419–444. doi: 10.1177/1474022219885791

Gaunt, H., and Westerlund, H. (2013). Collaborative Learning in Higher Music Education, 1st Edn. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315572642

Gies, S., and Sætre, J. H. (2019). Becoming Musicians: Student Involvement and Teacher Collaboration in Higher Music Education. Norges musikkhøgskole. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/11250/2642235 (accessed June 12, 2022).

Glǎveanu, V. P. (2014). Distributed Creativity: Thinking Outside the Box of the Creative Individual. Cham: Springer (SpringerBriefs in psychology).

Gordon Cohen, L. (2013). “Learning, assessment and signature pedagogies in the visual arts,” in Contextualized Practices in Arts Education: An International Dialogue on Singapore, eds Lum, C. H., (Singapore: Springer Science-Business Media).

Gurung, R. A. R., Chick, N. L., and Haynie, A. (2009). Exploring Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind (1st ed.). Stylus Pub. Available online at: http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip0824/2008031384.html (accessed June 12, 2022).

Hämäläinen, R., and Vähäsantanen, K. (2011). Theoretical and pedagogical perspectives on orchestrating creativity and collaborative learning. Educ. Res. Rev. 6, 169–184. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2011.08.001

Hastings, D. M. (2017). ‘With grace under pressure’: how critique as signature pedagogy fosters effective music performance. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 16, 252–265. doi: 10.1177/1474022216652772

Haynie, A., Chick, N. L., and Gurung, R. A. R. (2012). “Signature pedagogies in the liberal arts and beyond,” in Exploring More Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind, 1st Edn, eds N. L. Chick, A. Haynie, and R. A. R. Gurung (Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing), 1–12.

Heinert, J. (2017). Peer critique as a signature pedagogy in writing studies. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 16, 293–304. doi: 10.1177/1474022216652767

Heinert, J., and Chick, N. L. (2017). Reacting in literary studies: crossing the threshold from quality to meaning. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 16, 320–330. doi: 10.1177/1474022216652766

Jensen, L. A., and Allen, M. N. (1996). Meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Qual. Health Res. 6, 553–560. doi: 10.1177/104973239600600407

Kearns, L. (2017). Dance critique as signature pedagogy. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 16, 266–276. doi: 10.1177/1474022216652768

Kleinmintz, O. M., Goldstein, P., Mayseless, N., Abecasis, D., and Shamay-Tsoory, S. G. (2014). Expertise in musical improvisation and creativity: the mediation of idea evaluation. PloS One 9, e101568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101568

Kornetsky, L. (2017). Signature pedagogy in theatre arts. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 16, 241–251. doi: 10.1177/1474022216652771

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning - Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Love, K. G., and Barrett, M. S. (2019). Signature pedagogies for musical practice: a case study of creativity development in an orchestral composers' workshop. Psychol. Music 47, 551–567. doi: 10.1177/0305735618765317

McLain, M. (2021). Towards a signature pedagogy for design and technology education: a literature review. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. doi: 10.1007/s10798-021-09667-5. [Epub ahead of print].

Motley, P. (2017). Critique and process: signature pedagogies in the graphic design classroom. Arts Human. High. Educ. 16, 229–240. doi: 10.1177/1474022216652765

Rakena, T. O. (2016). “Sustaining Indigenous performing arts: The potential decolonizing role of arts-based service learning,” in Engaging First Peoples in Arts-Based Service Learning: Towards Respectful and Mutually Beneficial Educational Practices, eds Bartleet, B. L., Bennett, D., Power, A., and Sunderland, N., (Cham: Springer International Publishing).

Schrand, T., and Eliason, J. (2012). Feedback practices and signature pedagogies: what can the liberal arts learn from the design critique? Teach. High. Educ. 17, 51–62. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2011.590977

Shreeve, A., Sims, E., and Trowler, P. (2010). ‘A kind of exchange’: learning from art and design teaching. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 29, 125–138. doi: 10.1080/07294360903384269

Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus 134, 52–59. doi: 10.1162/0011526054622015

Sims, E., and Shreeve, A. (2012). “Signature pedagogies in art and design,” in Exploring More Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind, eds Chick, N. L., Haynie, A., and Gurung, R. A. R. (Vermont, USA: Stylus Publishing LLC), 55–67.

Stukenberg, J. (2017). Deep habits: Workshop as critique in creative writing. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 16, 277–292. doi: 10.1177/1474022216652770

Treacy, D., and Gaunt, H. (2021). Promoting interconnections between reflective practice and collective creativity in higher arts education: the potential of engaging with a reflective matrix. Reflective Pract. 22, 488–500. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2021.1923471

Virkkula, E. (2016). Communities of practice in the conservatory: learning with a professional musician. Br. J. Music Educ. 33, 27–42. doi: 10.1017/S026505171500011X

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Willingham, L., and Carruthers, G. (2018). “Community music in higher education,” in The Oxford Handbook of Community Music, Bartleet, B. L., and Higgins, L. (New York: Oxford University Press), 595–616.

Keywords: signature pedagogies, collaborative creativity, music, higher education, professional development (PD)

Citation: Creech A, Zhukov K and Barrett MS (2022) Signature Pedagogies in Collaborative Creative Learning in Advanced Music Training, Education and Professional Development: A Meta-Synthesis. Front. Educ. 7:929421. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.929421

Received: 26 April 2022; Accepted: 01 June 2022;

Published: 29 June 2022.

Edited by:

Natassa Economidou-Stavrou, University of Nicosia, CyprusReviewed by:

Full Professor Michele Biasutti, University of Padua, ItalyBo-Wah Leung, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Copyright © 2022 Creech, Zhukov and Barrett. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrea Creech, QW5kcmVhLkNyZWVjaCYjeDAwMDQwO21jZ2lsbC5jYQ==

Andrea Creech

Andrea Creech Katie Zhukov

Katie Zhukov Margaret S. Barrett

Margaret S. Barrett