- 1School of Art and Design, Shandong Jiaotong University, Jinan, Shandong, China

- 2Faculty of Humanities and Arts, Macau University of Science and Technology, Taipa, Macau, China

- 3Heritage Conservation Laboratory, Macau University of Science and Technology, Taipa, Macau, China

- 4Faculty of Innovation and Design, City University of Macau, Taipa, Macau, China

China’s rapid economic development has brought challenges to traditional villages, which carry the characteristics of Chinese civilization and traditional culture. Protecting traditional villages is of enormous significance. As a representative of Qilu Cultural District, Shandong has many national-level traditional villages, but some areas lack research on traditional villages and related local cultural landscapes due to various reasons. This study was divided into two parts. First, CiteSpace 6.1.R6 and VOSviewer1.6 software were used to perform a visual bibliometric analysis of the vernacular cultural landscape. Then, China’s Qilu Cultural District (Shandong Province) was taken as a typical case; the literature was read carefully, and an in-depth qualitative analysis was carried out in the research context of the vernacular cultural landscape. This study found that the United States, the United Kingdom, and China have outstanding research results in this field, and the directions of the research have gradually diversified from the early focus on rural and agricultural environments to the later focus on cultural landscape protection, management, and sustainable development. By taking Shandong as an example, the study of traditional villages takes the year 2000 as the starting point and involves architecture, archaeology, culture, and other fields. The architectural field primarily concentrates on the spatial layout, where cultural protection emphasizes the integration of sustainable development using scientific and technological methods, and cultural tourism grapples with the issue of homogenization. Future research needs to improve the literature database, consider local Chinese characteristics, and establish an independent literature database for multidimensional, multifaceted, and cross-cultural research. The direction and focus of this research provide methods and references for subsequent research.

1 Introduction

1.1 The protection of traditional villages needs urgent attention

In the past two or 3 decades, China’s economy has developed rapidly, and the country has moved towards urbanization and industrialization at an unprecedented speed. This is the only way for our country to become a modern nation. However, the migration of a significant number of people and resources to cities and towns forced the dismantling and reorganization of rural, social, and land structures, profoundly influencing rural economics, history, culture, and other aspects. Farming laid the foundation for the Chinese nation (Jiang, Y. et al., 2020). As the carrier of Chinese civilization, the countryside has witnessed five thousand years of uninterrupted history, and traditional villages are the living historical and cultural heritage of the present. Mr. Feng Jicai, the first advocate for protecting traditional villages in China, released a set of data to the media in 2012: Before 2005, there were 3.6 million natural villages in China. However, by 2012, there were only 2.7 million left (Zhao, Q. 2014). In other words, in the first 10 years of 2012, China lost 900,000 natural villages, an average of 80 natural villages every day (Liu, S. et al., 2022). This is a very eye-catching figure. We are confronted with the disappearance of traditional village material space and the livelihood of rural people, and change is a great challenge. By conducting comprehensive and detailed research on traditional villages, we can contribute to the renewal of their protection mechanisms and the continuation of their excellent traditional culture. With their dynamic nature, traditional villages demonstrate the cultural characteristics and national character of Chinese farming civilization and carry traditional cultural features (Duara, 1991). Co-ordinating traditional villages with contemporary culture and the modern economy represents not only a practical aspect of implementing the rural revitalization strategy but also serves as an inherent requirement for the balanced development of both urban and rural economies (Deng, X. et al., 2022; DeVilbiss, J. M. et al., 1993), and it is time to meet the spiritual and cultural needs of villagers. In the final analysis, regarding the historical process of social development and changes in people’s lives, protecting traditional villages that carry the excellent genes of the Chinese nation has important practical significance and contemporary value in terms of carrying forward Chinese civilization and realizing national rejuvenation.

From a macro perspective, vernacular culture refers to the material and spiritual achievements that a region or a nation has formed over its long history (Heath, K. 2009; Fu, J. et al., 2021). For an individual, vernacular culture is the material or intangible folk culture native to the place where a person was born and raised (Khafizova, 2018; Karakul, 2013). Vernacular culture, with important humanistic and social values, is an important foundation for rural landscape creation. However, while there has been significant progress in the excavation, research, protection, and utilization of local culture in villages, there has also been significant progress in the renewal and development of traditional villages and towns. This objectively piques people’s interest in local culture. However, modern urban factors are eroding the traditional countryside, and the trend of homogenization is becoming more and more obvious. Our research team has spent many years visiting and investigating traditional villages, and we have identified several practical problems that exist today. (1) The first issue is the lack of a distinct local regional culture. The cultural differences in each region reflect the differences in social structure, and it is this difference that makes regional culture highly identifiable. The local cultural landscape represents this identifiable nature. The local cultural landscape is not a superposition of single elements but rather an organism that integrates multiple elements. When we protect local cultural landscapes, we often overlook the extraction of local cultural elements. Blind construction destroys the integrity of the material form of local cultural landscapes, wasting local cultural resources and also leading to serious homogenization. The core of the establishment of a local cultural landscape protection mechanism is the preservation of local regional culture, including its spatial and temporal characteristics. Only by doing this will we prevent it from being completely destroyed by societal changes. (2) The second issue is the absence of mechanisms to safeguard local cultural landscapes. The majority of these issues stem from a failure to prioritize the preservation of the local cultural context, for example, the protection and development of only a single village or a single local element and insufficient protection of mountain villages with rich local resources. Plain villages close to cities are seriously affected by urban planning and lack scientific and rigorous method guidance. (3) Rural landscapes should align with the development of modern society, embracing the concept of returning to nature, advocating for nature, and promoting environmental protection. Excessive commercial tourism development has caused villages to lose their locality. Local culture plays a crucial role in landscape design and significantly influences its style. In the long run, the study of the vernacular cultural landscape is a dynamic process that requires in-depth discussion based on specific local case studies.

1.2 Typicality of the villages in the qilu cultural district (Shandong Province)

As shown in Figure 1, there are 16 cultural regions in China, and Shandong Province (Qilu Cultural District) is one of them. As of October 2022, the Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development and other relevant departments have announced a total of 8,155 national-level traditional villages in six batches, protected more than 530,000 traditional buildings and residential buildings, and inherited 4,789 intangible cultural heritage items at or above the provincial level, forming a world-wide scale and content (Bian, J. et al., 2022; Wu, C. et al., 2020; Su, H. et al., 2022). The largest and richest agricultural civilization heritage protection group represents the most valuable, best-protected, and dynamic agricultural civilization heritage. Since 2012, there have been six batches of 168 national-level traditional villages in Shandong Province. The number of national-level traditional villages in each batch is 10, 6, 21, 38, 50, and 43, respectively. The fourth batch experienced a significant increase, with the addition of 17 new villages. Since 2014, the Shandong Provincial Department of Housing and Urban–Rural Development and other relevant departments have announced five batches of provincial-level traditional villages in Shandong Province, totaling 511. The number of provincial-level traditional villages in each batch is 103, 105, 103, 100, and 100, respectively. Previous spatial research on the first five batches of national-level traditional villages in Shandong primarily revealed the distribution of these villages in central and eastern Shandong. At the municipal level, statistics reveal their primary concentration in four prefecture-level cities: Zibo City, Yantai City, Jinan City, and Weihai City. The total number of traditional villages in these four cities accounts for about three-fifths of the entirety of Shandong. There are a large number of national-level traditional villages distributed in Zibo City and Yantai City, as well as the counties within their jurisdiction. In the two cities, there are 57 national-level traditional villages, accounting for about one-third of the total. Zichuan District and Boshan District primarily host Zibo traditional villages, while Zhaoyuan City, Longkou City, and Muping District host Yantai traditional villages. Tai’an City, Qingdao City, Liaocheng City, Rizhao City, Liaocheng City, and Heze City all have five or fewer national-level traditional villages. Among them, Liaocheng City has only three. Only the most recent batch selected traditional villages, not the first five batches. The sixth batch of national traditional villages has been revealed. Heze City has the fewest selections, as only two traditional villages were selected in the fourth batch. Among the 16 prefecture-level cities in Shandong, three cities and the counties under their jurisdiction do not have national-level traditional villages, namely, Dongying City, Binzhou City, and Dezhou City. The northern Shandong region, which includes these three prefecture-level cities, is a blank space for the distribution of national-level traditional villages.

Documentary records and field surveys reveal that most traditional villages in northern Shandong, including Longju Town, Wudi County, Zhanhua District, and others, continue to practice simple lifestyles and traditional rural customs. Topographically, these areas are located in the North China Plain, with its flat terrain and numerous rivers and lakes, which were conducive to the birth and development of China’s ancient farming civilization, and they carry historical and cultural information about the Chinese nation (Liu, C., & Xu, M. 2021). Due to their location on the province’s edge, these areas often go unnoticed, leading to the gradual disappearance of traditional villages as Shandong’s urbanization accelerates. The blank distribution of traditional villages in some counties and cities in Shandong has resulted in a lack of research on the vernacular cultural landscape in related areas. Our investigation has identified two key reasons for this lack of research. First of all, different cities in the province have different conditions due to the terrain, transportation, economy, and other conditions. Overall, northwest Shandong and southwest Shandong are situated in the province’s inland and border areas. They are characterized by vast plains, a weak economic foundation, and convenient transportation. This is not conducive to the preservation of traditional villages and buildings, and the natural elimination rate is very high. Although the Shandong and Jiaodong regions have high economic strength, most of them are mountainous and hilly (Yanbo, Q. et al., 2018). The transportation cost to reach traditional villages is relatively high, but they have preserved the somewhat complete local cultural landscapes of traditional villages. Secondly, local governments and relevant departments exhibit varying levels of awareness and attitudes towards the rating of traditional villages and their applications. Historical and cultural value, overall style preservation, and regional characteristics are all important criteria for rating traditional villages. Some grassroots governments and competent authorities have not made sufficient professional estimates on these factors and will not rate them if they are not reported. However, nonrating cannot negate the existence of traditional villages. Rating traditional villages later and increasing their value will lead to their natural or forced elimination, which will also hasten the extinction of the associated local cultural landscapes. Therefore, the traditional villages in the Qilu Cultural District are actually a microcosm of the numerous traditional Chinese villages and have typical representative significance.

1.3 Problem statement and objectives

The implementation of the “rural revitalization” strategy and the practice of “beautiful countryside” construction also require innovative updates in the theories and methods of rural cultural landscape research. First of all, while taking the local cultural landscape as the research object, we should also consider the traditional villages as a unified whole for joint research. Traditional villages play a crucial role in shaping the local cultural landscape and fostering close connections (Ren, K., & Wu, T. 2023). A good traditional village style can only emerge through the construction and design of the local cultural landscape. Secondly, in the future, the local cultural landscape will be a continuous research hotspot. Current statistics estimate the number of traditional villages with historical, economic, and cultural research value in China to exceed 10,000, in addition to the six batches of national-level traditional villages already announced. A significant proportion of these traditional villages are well preserved, boasting rich landscapes. As villages undergo further excavation and protection, their numbers will continue to increase. Next, it is important to study the various types of traditional villages that have been rated as a system, as this plays a crucial role in presenting the rich local cultural landscape of China. Thirdly, the inclusion of more traditional villages in the protection list leads to an increase in the quantity of research samples pertaining to local cultural landscapes.

Although typical qualitative research can solve the universal problems of related topics from a macro perspective, in order to conduct detailed research on the local cultural landscape of traditional villages, specific cases require different analyses and explanations. First, different geographical environments in Shandong will also present different local cultural landscapes; second, even relatively similar geographical environments will produce different local cultural landscapes. Third, on the basis of typical case studies, the local cultural landscapes of different regions not only need to be interpreted macroscopically and systematically in terms of the whole geographical scope and the whole cultural scope but also need to be considered in terms of the geographical comparison of adjacent regions and the culture of adjacent regions. Exchanges significantly influence how local cultural landscapes are presented. As a region with many schools of Qilu culture, Shandong must conduct research based on the typical culture in the region to better interpret the characteristics and distribution of the local cultural landscape of traditional villages in the entire region, study its protection mechanism, and finally protect the excellent local cultural heritage of Qilu, providing a reliable basis for utilization.

This study aimed to explore the global trends, theoretical significance, and practical applications of vernacular cultural landscape research by using quantitative analysis and case studies of Qilu Cultural District. By using CiteSpace 6.1.R6 and VOSviewer 1.6 software and combining qualitative and quantitative analysis methods, the research dynamics, theme evolution, and interdisciplinary characteristics of this field were revealed, while the regional challenges and protection opportunities of the Qilu Cultural District were analyzed. The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows: Section 2 explains China’s cultural divisions, laying a localized background for the interpretation of the theory of the vernacular cultural landscape and analyzing the regional scope, research methods, and data sources of this study.Section 3 analyzes global trends in vernacular cultural landscape research using bibliometric methods. Section 4 examines the trends within various research networks. Section 5 uses the Qilu Cultural District as a typical case, conducts a qualitative analysis of the development of the vernacular cultural landscape, and summarizes the characteristics and laws of this case. Section 6 presents our conclusions.

2 Previous theories, study areas and methods

2.1 Previous theories and definitions

2.1.1 Traditional villages

Traditional villages in China, formerly known as ancient villages, refer to villages built before the Republic of China (1912–1949 A.D.). The expert committee meeting for the protection and development of traditional villages decided in September 2012 to change the customary name of “ancient village” to “traditional village”, and officially proposed the concept of “traditional village”. This type of village usually has a large time span. Under certain historical conditions, the development of village appearance, architectural patterns, and folk customs is relatively stable, but, at the same time, it has certain cultural connotations. This type of village can reflect the local historical heritage and local culture, life, and production methods. It is a comprehensive carrier of material and intangible culture, with high academic value and historical and cultural heritage. Replacing the word “ancient” with “traditional” realizes the transformation from the dimension of time to the dimension of thought, culture, customs, institutions, and art, further highlighting the cultural value of traditional villages and the importance of their inheritance, protection, and development. In 2012, the Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development, the former Ministry of Culture (now the Ministry of Culture and Tourism), the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, and the Ministry of Finance jointly launched a survey of traditional Chinese villages. Regarding cultural construction and rural protection work, the Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development, the Ministry of Culture, and other relevant government departments jointly established an expert committee in September 2012, comprising experts in architecture, folklore, planning, and other fields, to review the “List of Traditional Chinese Villages”. By 2023, China has announced six batches of lists of traditional Chinese villages, with a total of 6,819 villages with important protection and value included in the list of traditional Chinese villages. Different regions have different local cultures (Kai, Y., & Huijun, Z. 2024). By using local cultural elements and regional landscapes, we can show the beauty of the times, emphasize the beauty of human nature and the beauty of ecology, and lay an institutional and cultural foundation for the establishment of a traditional rural landscape protection mechanism.

2.1.2 Vernacular cultural landscape and previous theories

The township is the most basic administrative unit in China’s administrative hierarchy (Chung, J. H. 2009; Chan, R. C., & Zhao, X. B. 2002). It is an administrative concept that refers to units with agricultural production as its pillar industry; in other words, it is a farming civilization concept. Scholar Yu Kongjian stated that “Vernacular cultural is the definition of a cultural type, which refers to dialectal, regional, ordinary, and spontaneous landscapes” (Biboum, M. J., & Rubio, R. G. 2020). In his book From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society, Fei Xiaotong scientifically pointed out that rural character is the most significant feature of China’s social structure (Fei, X. et al., 1992). According to environmental behavior scholar Amos Rapoport, the concept of “native” in the rural landscape is associated with the elite (high style) culture (Rapoport, A. 1992). Rural areas generally refer to settlements dominated by agricultural people engaged in agricultural activities. For instance, the American scholar R.D. Roderfield observed that “rural areas are sparsely populated, relatively isolated, with agricultural production as the main economic basis, and people’s lives are essentially similar, but they are similar to other parts of society, especially urban areas. That’s what makes the city different. We can divide villages into two categories: natural villages and administrative villages, based on their administrative significance”. A natural village can include several administrative villages, and a large administrative village can also contain several natural villages (Xu, Z. et al., 2018). Generally speaking, rurality is more of a cultural concept. The local culture and rural landscape, derived from the countryside, are important manifestations of agricultural culture.

Therefore, the emergence of vernacular culture is based on agricultural civilization. It is an earthy, regional, and native agricultural culture, and it also represents a form of interpersonal relationships within agricultural civilization. The longevity of vernacular culture is supported by this form of interpersonal relationships, where blood serves as the core, kinship provides support, and geography serves as the basis. China is a major agricultural country, and agricultural production is also a Chinese pillar industry (Yu, J., & Wu, J. 2018). The concept of vernacular culture also forms the collective memory of most Chinese people. In the conventional definition, vernacular culture refers to various elements related to the place of birth, including the historical background, folk customs, folklore, local architecture, the biographies of famous figures, village rules and regulations, family genealogy, traditional skills, etc. Vernacular culture expresses these elements either materially or immaterially. Vernacular culture, on the other hand, is the material or nonmaterial folk culture native to the place where a person was born and raised. Villagers adopt a vernacular landscape to adapt to the space and pattern of the natural environment for their survival needs. It is a reflection of the villagers’ production and living requirements in the natural environment. Therefore, the vernacular landscape is a comprehensive regional system that encompasses the natural environment, settlements, folk customs, beliefs, and other elements, all of which reflect the relationship between people and environmental elements. On the one hand, the vernacular landscape serves as a carrier of vernacular culture, while on the other hand, vernacular culture infuses spiritual connotations into the vernacular landscape (Umbach, M., & Hüppauf, B. R. 2005). Both are based on agricultural civilization and have both material and nonmaterial cultural attributes. Compared to rural landscapes, vernacular culture encompasses a wider range of forms and beneficiaries. Vernacular culture extends beyond rural areas, finding applications in towns, cities, and urban villages. The form of the vernacular landscape is also richer than that of the rural landscape based on agricultural production, and it is a localized landscape expression. The emergence of the vernacular landscape is a comprehensive expression of vernacular culture, as well as a concentrated expression of local and native cultures. This expression reflects the locality of Chinese society and the collective memory of farming culture.

The vernacular cultural landscape is an important part of the cultural landscape. It integrates the concept of “native” into the cultural landscape, creating a culture that instills “nostalgia” (Smeekes, A. N., & Jetten, J. 2019). The study of vernacular cultural landscapes began in European and American countries. The reason was the rapid arrival of urbanization, which triggered changes in the human settlement environment as well as the huge expansion of the number and scale of cities. What follows is a landscape form in which people ignore the organic connection between human activities and the natural environment in their standardized and efficient lives (Cosgrove, D. 2017). Various types of landscape objects that were “unprofessionally designed” and built in “original ways” began to attract widespread attention, and the term “vernacular landscape” was born (Balmori, D. 1994; Blier et al., 2006). Professor Wu Liangyong, academician of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, defines the vernacular landscape as the following: In the process of survival and living, local people blend with the local natural environment and land, and mutual transformation shows regional characteristics. It encompasses a complex landscape that is influenced by multiple factors. It represents the natural geographical characteristics of a region, as well as the cultural characteristics of the social system (Liangyong, W. 2000). China’s vernacular landscape, while rooted in rural areas, transcends these boundaries. It is a people-oriented cultural landscape. Therefore, the vernacular cultural landscape strives for originality in design, which it partially reflects. It reflects the material and spiritual sustenance of local residents, as well as the long-term impact and adaptation of humans, the geographical environment, and living space. Vernacular cultural landscapes encompass not only rural areas but also regional and informal landscapes. The main components of the vernacular cultural landscape are the rural ecological landscape, the agricultural production landscape, and the rural life landscape. Ancient trees, ancient monuments, ancient wells, stages, temples, and ancestral halls, as well as immovable production and living tools, embody rural ecological landscapes, along with other products that carry a specific history and local cultural characteristics. They appear individually or in groups.

2.2 Case studies in geographical and cultural regions: Qilu cultural district

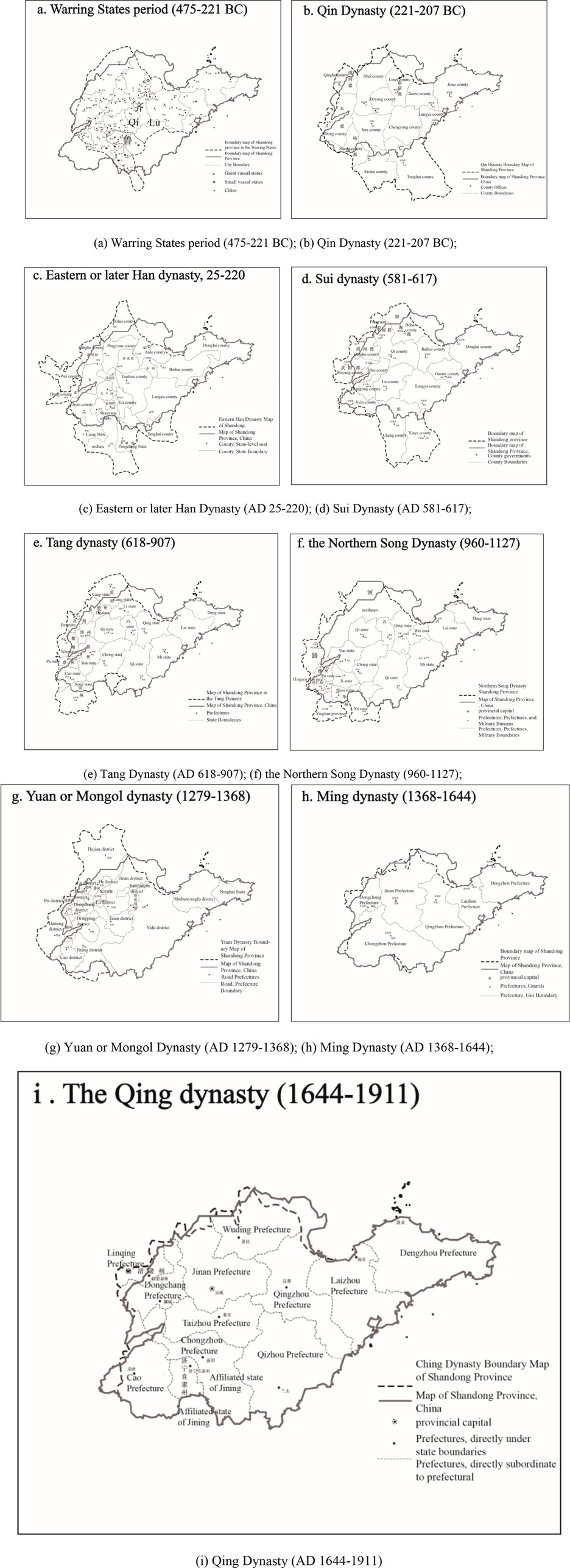

The name “Qilu” originated from the pre-Qin Qi and Lu countries (approximately the Paleolithic period ∼221 B.C.). During the pre-Qin period, the Qi State, bordering the coast to the east, produced Taoist thought represented by Jiang Ziya (Ge, J., & Hu, Y. 2021). It integrated and absorbed the local Dongyi culture, taking Guan Yan’s theory and Jixia Academy as its cultural foundation (Yong, M. et al., 2016). The process of integration and development led to the formation of the Qi culture. During the Spring and Autumn Periods (770–221 B.C.), the State of Lu produced Confucian thought, represented by Confucius and Mencius, which gradually gave birth to Lu culture (Tu, W. M. 1998). Qi took Zibo City, Shandong Province, as its capital, including most areas such as northern Shandong and eastern Shandong. Jining City, Shandong Province, is the capital of the State of Lu, which also includes small parts of western Shandong and southern Shandong (Croddy, E. 2022). At the end of the Warring States Period (476–221 B.C.), the cultures of Qi and Lu gradually merged into one, hence the name. The State of Chu destroyed the State of Lu in 256 B.C. In 221 B.C., the State of Qin annexed the State of Qi. The blending of cultures led to the formation of a unified regional cultural circle known as “Qilu”, which later formed the regional concept of “Qilu” and roughly mirrored the administrative scope of Shandong Province. In the late Qing Dynasty (1616 or 1644–1911), “Lu” began to be used as the name of Shandong Province. As a result of the province’s abbreviation, “Qilu” became synonymous with Shandong Province (Chen, Y. 2019). The “Qilu culture” we are talking about today is derived from ancient Qi and Lu cultures. It is also the result of a high degree of openness and exchange between Qi culture and Lu culture. They gradually merged into a cultural whole that values etiquette and abides by ethics, serving as an important source of Chinese culture and making significant contributions to its formation and development. As a result, Qilu culture refers to a regional culture that originated and developed in Shandong Province, China. Geographically, the Taiyi Mountains center the Qilu Cultural District, encompassing the area east of the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal in today’s Shandong Province, northern Jiangsu Province, and the Liaodong Peninsula. It is basically the same as the Jiaoliao Mandarin District and Shandong Province. The Grand Canal and the Central Plains Culture border the Hebei-Shandong Mandarin District to the west, the Jianghuai Culture District of the Jianghuai Mandarin District to the south, the Bohai Strait to the north, and the Northeastern Culture District of the Northeast Mandarin District on the Liaodong Peninsula to the northeast. We can subdivide Qilu culture into “Western Lu culture” and “Jiaodong culture”. From Qi and Lu in the Western Zhou Dynasty to today’s Shandong, the scope of jurisdiction has also changed many times with the development of history. Following the establishment of New China in 1949, a series of significant regional changes shaped the current provincial jurisdiction of Shandong Province. Shandong, the name of a definite administrative division, appeared not long ago, but it was formed based on the geographical scope of Qi and Lu during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States Periods, as well as Qilu culture. Simultaneously, when Shandong emerged as the most significant local administrative division, political, economic, and other factors eroded the regional attributes of Qilu culture (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Shandong Province’s historical administrative scope for nine periods, from the Warring States Period to the Qing Dynasty. Different small pictures represent respectively: (A) Warring States period (475–221 BC); (B) Qin Dynasty (221–207 BC); (C) Eastern or later Han Dynasty (AD 25–220); (D) Sui Dynasty (AD 581–617); (E) Tang Dynasty (AD 618–907); (F) the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127); (G) Yuan or Mongol Dynasty (AD 1279–1368); (H) Ming Dynasty (AD 1368–1644); and (I) Qing Dynasty (AD 1644–1911). (Image source: drawn by the author).

2.3 Research methods

Therefore, this study divides the discussion into two main parts: macro (overall trends in bibliometrics) and micro (analysis of typical cases). First, CiteSpace 6.1.R6 and VOSviewer1.6 software were used to make a visual bibliometric analysis of vernacular cultural landscape. Then, the Qilu Cultural District (Shandong Province) was taken as a typical case, the literature was read carefully, and an in-depth qualitative analysis was carried out regarding the research context of the vernacular cultural landscape. The direction and focus of the research provide methods and references for subsequent research. This study believes that the vernacular cultural landscape is multi-faceted and involves case characteristics of different cultural regions. It often covers historical and regional research. Bibliometrics is conventionally just a statistical review of literature. Therefore, the regional research case of the Qilu region, as a qualitative, in-depth explanation, helps broaden the perspective of the vernacular cultural landscape from macro to micro. These two parts are complementary to each other.

At the same time, this study used CiteSpace 6.1.R6 (https://citespace.podia.com/) and VOSviewer1.6 (https://www.vosviewer.com/) software to visualize the literature results. CiteSpace is Java-based visualization analysis software that is mainly used for trend and pattern analysis regarding scientific literature. It can identify research frontiers, co-citation networks, and the temporal evolution of keywords. Its powerful clustering and temporal dynamic analysis functions have been widely used in metrology research. VOSviewer is another widely used piece of metrology analysis software that focuses on building and visualizing network data, such as author collaboration, co-citations, and keyword co-occurrence. Its intuitive graphical interface can help researchers clearly display data structures and their internal relationships. CiteSpace 6.1.R6 software was used to analyze the publication volume, institutional co-operation relationships, author publication status, keyword co-occurrence, and keyword temporal prominence changes in the literature; VOSviewer1.6 software was used to analyze the countries/regions with active research in this field, document co-citations, journal co-quotes, author co-quotes, hot word frequency clustering, and hot word temporal evolution changes, comprehensively considering the characteristics, evolution, and prospects of local cultural landscape research. Lastly, we qualitatively analyzed and discussed the relevant research, using the traditional villages in the Qilu Cultural District as an example (Figure 3).

Figure 3. In 2022, the research team (pictured) investigated Zhujiayu, a national traditional village in Jinan, Zhangqiu District, Shandong Province. (Image source: photographed by the author).

2.4 Data sources

The main source of data for this study is the Web of Science (WOS) core database (https://clarivate.com.cn/solutions/web-of-science/), which has the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Arts & Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI), Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI), and Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED). This is so that the academic research results on the shape and layout of rural settlements can be systematically analyzed and evaluated. We selected the Web of Science database for bibliometric analysis due to its wide range of subject coverage, rich historical data, high-quality data, powerful built-in analysis tools, good user experience and technical support, globally recognized authority, and comprehensive citation data. These advantages ensure the comprehensiveness, reliability, and depth of the research, as well as providing a solid foundation for high-quality academic research.

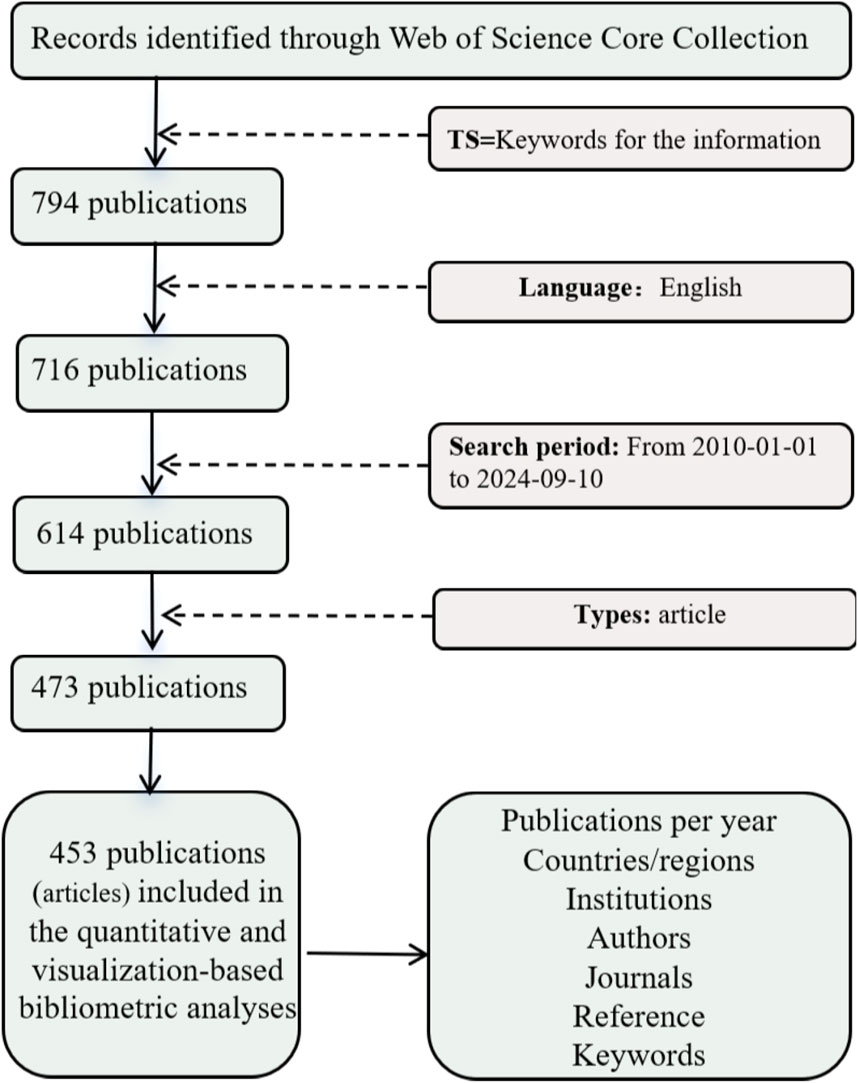

During the search process, we used two sets of keywords and combined them with the Boolean logic operator “AND” to ensure the comprehensiveness and relevance of the search results. The specific search formula is TS = (“Vernacular Cultural Landscape” or “Vernacular Landscape” or “Vernacular Cultural Architecture” and “China”). To ensure the timeliness of the literature, we limited the search time to between 1 January 2010 and 10 September 2024. Academic articles relevant to the search topic met the inclusion criteria, while non-academic materials, such as letters, notes, and book reviews, were not considered. Figure 4 illustrates the specific search process. The above search strategy retrieved a total of 453 articles related to the spatial morphology of rural settlements, which served as the data source for this study.

3 Results: global trends in vernacular cultural landscape research

3.1 Analysis of the current status of the publication

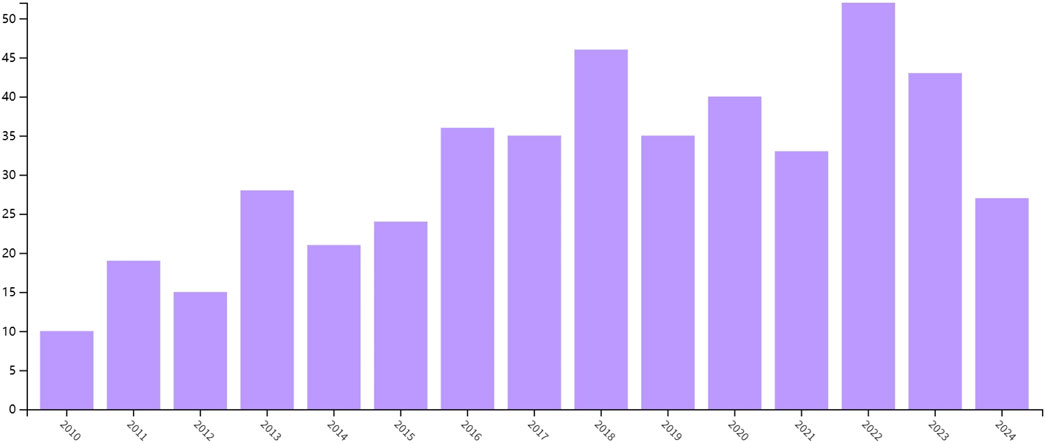

We conducted a trend analysis on the number of publications in the field of vernacular cultural landscape from 2010 to 2024; Figure 5 displays the results. Research output in this field has increased significantly over the past decade and has shown three main phases. By 2024, the annual publication volume of vernacular cultural landscape research had increased significantly, experiencing the transition from the initial exploration stage (2010–2014) to the peak stage (2020–2024). The number of publications reached a peak of 52 articles in 2022, reflecting the growing academic attention in this field. A regression analysis of the data from 2010 to 2024 yielded a function model of y = 0.983

Figure 5. Annual publication trend analysis (image source: the author took it from the WOS platform).

3.2 Active countries/regions analysis

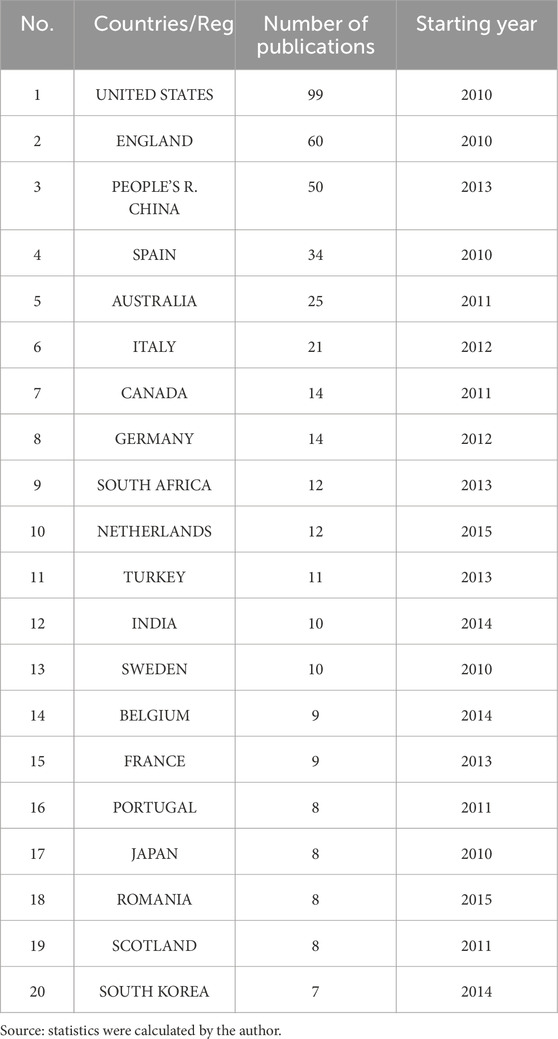

This study obtained the data results by applying software such as CiteSpace 6.1.R6 to quantitatively analyze the publication database and VOSviewer1.6 to study the countries/regions with active research in this field. Table 1 reveals that the United States of America (USA), the United Kingdom (England), and China (People’s Republic of China) are the top three countries in terms of article publication, with 99, 60, and 50 articles, respectively. These countries hold a dominant position in this field of research, demonstrating their significant contributions to the study of the vernacular cultural landscape. Spain, Australia, and Italy were also active, publishing 34, 25, and 21 articles, respectively. Certain subfields of this field, particularly the protection and sustainable development of vernacular cultural landscapes, are the focus of research activities in these countries. In terms of time dimensions, the United States and the United Kingdom have been active in this field since 2010, while China’s research boom has grown significantly since 2013. This reflects the advantages of early scientific research in the United States, the United Kingdom, and China, which have had a rapid rise in this field in recent years. Research interest in other countries, such as South Africa, the Netherlands, and Turkey, has gradually increased since 2013 or 2015, showing that more and more countries are paying attention to this field.

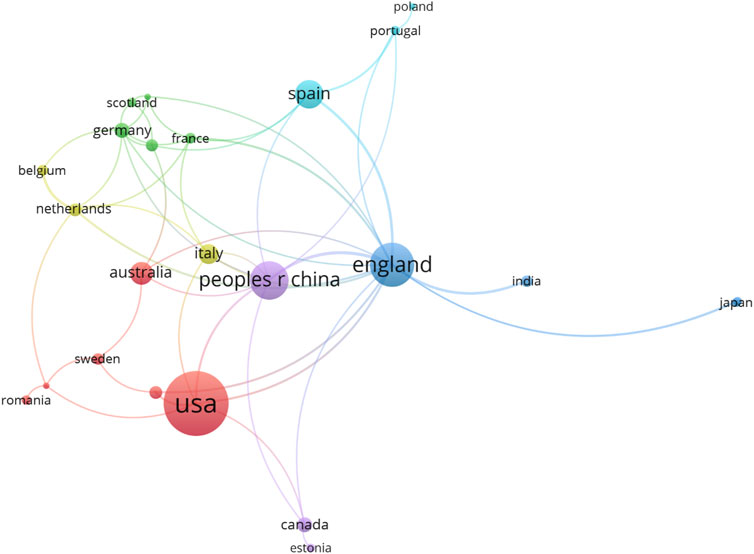

The co-operation network diagram from VOSviewer (Figure 6) reveals that the United Kingdom dominates the most complex co-operation network, particularly frequent co-operation with China, Italy, Spain, and other countries. There is also relatively more co-operation between the United States and the United Kingdom, indicating that the two countries have a strong co-operative relationship in scientific research. Furthermore, the co-operation between China, the United Kingdom, and Australia is an important link in the network, demonstrating the importance of transnational academic co-operation. The United Kingdom has formed a regional co-operation network with many European countries (such as France, Germany, and the Netherlands). This may be due to the proximity of geographical location and cultural research background, which gives these countries more co-operation opportunities in the field of cultural landscape.

Figure 6. Analysis of the co-operation relationships between countries/regions (image source: drawn by the author).

In terms of regional differences, the United States in North America and the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, and other countries in Europe show strong scientific research strength and regional advantages. The scientific research activities of Asian countries such as China, Japan, and South Korea have gradually increased in recent years, but there is still a certain gap compared with the academic activities of European and American countries. From the network connections and the number of publications in the figure, it can be seen that future research is likely to rely further on international co-operation, especially cross-continental co-operation that will promote the development of this field. Emerging scientific research countries such as China, India, and South Africa are expected to continue to exert their efforts in the next few years, especially in the protection of digital cultural heritage and the sustainable development of cultural landscapes. Overall, the United States, the United Kingdom, and China are the most active countries in this field, with extensive co-operation networks and leading scientific research output. As research in this field develops in-depth, cross-border co-operation and the rise of emerging scientific research countries will become future trends.

3.3 Analysis of institutional distribution

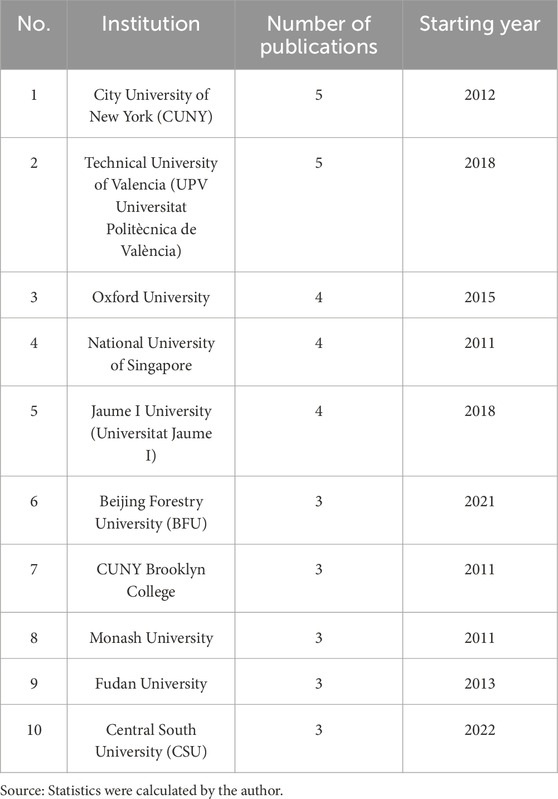

The analysis in Table 2 reveals that the City University of New York (CUNY) and Technical University of Valencia (UPV Universitat Politècnica de València) have the highest number of publications, with five papers each, indicating their significant influence on vernacular cultural landscape research. They published four articles, followed by those from Oxford University, the National University of Singapore, and Jaume I University (Universitat Jaume I). This demonstrates that these institutions are also relatively active in related research activities, particularly in cultural landscape protection and rural settlement morphology research.

The scientific research activities of various institutions started at different times. The City University of New York (CUNY) has been active in this field since 2012, while the Technical University of Valencia (UPV Universitat Politècnica de València) and Jaume I University (Universitat Jaume I) joined this research field in 2018, indicating that these institutions have become interested in this field at different times and have demonstrated their scientific research strength in this field through their gradual increase in the number of publications. In addition, Chinese universities such as Beijing Forestry University and Fudan University have gradually emerged in recent years, especially Beijing Forestry University, which entered this field in 2021 and published three papers, reflecting the rapid development of Chinese universities in this research field.

The analysis of institutional partnerships (Figure 7) further demonstrates the collaborative relationships between scientific research institutions around the world. The Technical University of Valencia and CUNY Brooklyn College show core collaboration positions and maintain close collaboration with multiple international institutions, such as Oxford University and the National University of Singapore. This extensive international collaboration encourages further research and discussion of the vernacular cultural landscape in the global academic community.

Overall, the picture reflects the activity of various institutions in this research field and the extensiveness of international co-operation. In particular, the trend of co-operation between European, American, and Asian universities is becoming increasingly obvious, and international research collaboration has promoted the continuous development of this field. In the future, with the participation of more universities and the further expansion of the co-operation network, research on the vernacular cultural landscape will continue to achieve more important results.

3.4 Analysis of research authors

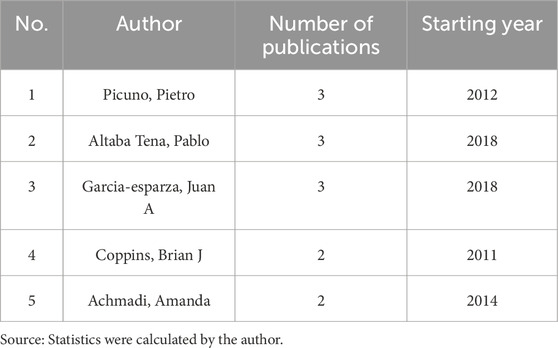

As shown in Table 3, Pietro Picuno and Pablo Altaba Tena are the authors with the most publications, with three papers published each. Picuno has been conducting research in this field since 2012, while Altaba Tena entered it in 2018. Despite starting late, they have published a significant number of papers. Other active authors, such as Juan A. Garcia-Esparza and Brian J. Coppins have also published two or more papers each, showing their continued contribution to the field of vernacular cultural landscape.

The CiteSpace-generated author collaboration network diagram reveals that Picuno holds a central position within the network (Figure 8), with a prominent node symbolizing his close collaboration with numerous researchers. In addition, Dina Statuto and Pablo Altaba Tena have a significant influence on the collaboration network, demonstrating their extensive academic exchanges and co-operation in this field. The network closely connects Garcia-Esparza and Altaba Tena, suggesting frequent co-operation or academic exchanges in similar research directions. Brian J. Coppins and Amanda Achmadi are also located at important nodes of the collaboration network, showing that they have close co-operation with other researchers, especially with academic institutions in South Asia and Southeast Asia.

The collaboration network between different authors formed several small clusters, reflecting their different research directions in this field. For example, the research direction concentrated on by Picuno may be more related to the technical protection or policy-level research of cultural landscapes, while the research of Altaba Tena and Garcia-Esparza may involve more specific cultural heritage protection measures or local research. In the collaboration network, many authors maintain co-operation with researchers in other countries, which shows that research on the vernacular cultural landscape has strong transnational and interdisciplinary characteristics.

3.5 Literature Co-citation analysis

The co-citation analysis of the literature reveals the core literature and important research context in the field of vernacular cultural landscape research. By studying the citation and co-citation relationship of these key literature, scholars can better understand the evolution of the knowledge system in this field (Hjørland, B. 2013).

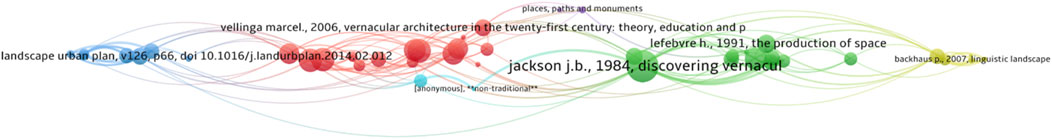

As can be seen from the co-citations (Figure 9), Discovering the vernacular landscape by Jackson, J. B. (1985) is the most cited document in this field, with 23 citations, having a very high academic influence (Jackson, J. B. 1985). Through extensive research on vernacular architecture, this article laid a theoretical foundation for the relevant field and became an important reference for understanding and exploring traditional architectural culture. Other documents related to the research of Jackson, J. B., such as The Production of Space by Lefebvre (1991), have an inevitable impact on the analysis of spatial production and the relationship between social structure and architecture. The Production of Space by Lefebvre (1991) has received nine citations, demonstrating its significant role in the study of cultural landscapes and vernacular architecture. Architecture without Architects by Rudofsky (1964) is another highly cited document (Rudofsky 1964), with a total of 10 citations, indicating that in the study of nonlinear architecture and traditional villages, this document provides a unique perspective for understanding vernacular architecture. The literature explores the inevitable impact of traditional buildings designed by nonprofessional architects on social culture, emphasizes the close connection between architecture and daily life, and provides an important reference for the cultural protection research of traditional villages.

The different colors of documents, when co-cited, represent different research focuses (Figure 9). Each dot’s major research highlights the specific topic within the field. Green revolves around “vernacular architecture” and “spatial production”, showing that the research in this field mainly focuses on the spatial expression of rural architecture and cultural landscapes and their socio-cultural functions. Red, on the other hand, concentrates more on the preservation and repurposing of cultural landscapes. This is exemplified by the research conducted by Agnoletti (2014), which holds the second-highest citation frequency. This research delves into the management and protection strategies of cultural landscapes, particularly the promotion of sustainable development through planning and protection management. The document’s high co-citation intensity (for example, its total connection intensity of 20) indicates that it has a greater influence on the academic community and promotes research discussions related to cultural landscape protection. Blue includes documents such as Palang (2005), which mainly involves the role of landscape and spatial planning interaction and explores how traditional landscapes can be protected and regenerated through spatial planning and policies in the context of rapid urbanization.

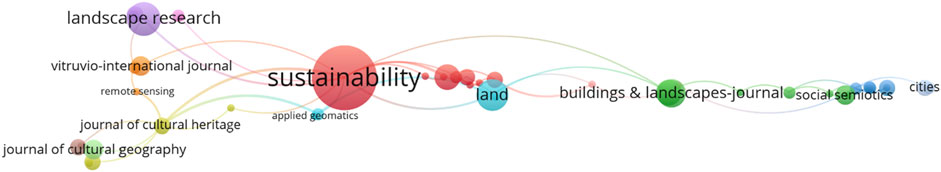

3.6 Journal Co-citation analysis

We can use journal co-citation analysis to determine the professionalism of journals, identify core journals, and describe the scientific structure through the disciplines represented by these journals. When at least one research article from two journals appears in the same cited literature, the two journals will have a common citation relationship. We used VOSviewer software to perform a visual analysis on related journals and generate a visual analysis chart of the journals’ co-citations, as shown in Figure 10. The connecting lines represent their co-citation intensity. The denser the connecting lines, the closer the relationship. Figure 10 reveals that the Sustainability journal has the strongest co-citation relationship, demonstrating its significant research influence in this field. As can be seen from the figure, Sustainability has a strong co-citation relationship with multiple journals, showing its core position in rural settlement cultural landscape and sustainability research. The journal’s high number of publications and citations demonstrate its broad influence and expertise in the field.

Furthermore, the Land and Buildings & Landscapes Journal journals exhibit strong co-citation relationships, indicating their importance in cultural landscape, architecture, and land use research. In particular, Land has a close co-citation relationship with other journals, indicating that its research direction is cross-disciplinary. The network diagram also features journals such as the Journal of Cultural Heritage and Landscape Research, underscoring the importance of their roles in cultural heritage protection and landscape research.

3.7 Author Co-citation analysis

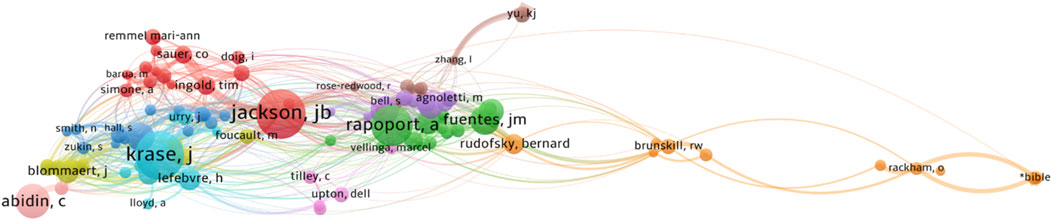

Author co-citation analysis is a method to reveal the academic influence and knowledge structure in a field by studying authors co-cited by different documents. VOSviewer generates an author co-citation network diagram in the vernacular cultural landscape research field, highlighting the academic relevance and importance of core authors in the field.

Figure 11 clearly shows that Jackson, J. B. is the most cited author, with the largest node located at the center of the network. This shows that Jackson has had a profound impact on the study of vernacular architecture and cultural landscape. His research emphasizes the cultural significance of rural landscape and architectural form, laying a theoretical foundation for research in this field. Jackson’s associated authors include Amos Rapoport and Bernard Rudofsky, who also play a pivotal role in exploring the relationship between architectural form, culture, and space. Discussions of traditional architectural form and cultural heritage protection often cite these authors, who constitute the generation of important literature in this field. Amos Rapoport is well known for his research on the interaction between architectural form and cultural context, which has made significant contributions to theoretical discussions on traditional architecture and cultural heritage protection. Bernard Rudofsky focuses on nonprofessional architecture, revealing how vernacular architecture reflects the unique social and cultural needs of its community. Together, these authors form the knowledge pillars of vernacular architecture and cultural landscape research, establishing a basic knowledge base for the field.

4 Research trend analysis

4.1 Keyword Co-occurrence analysis

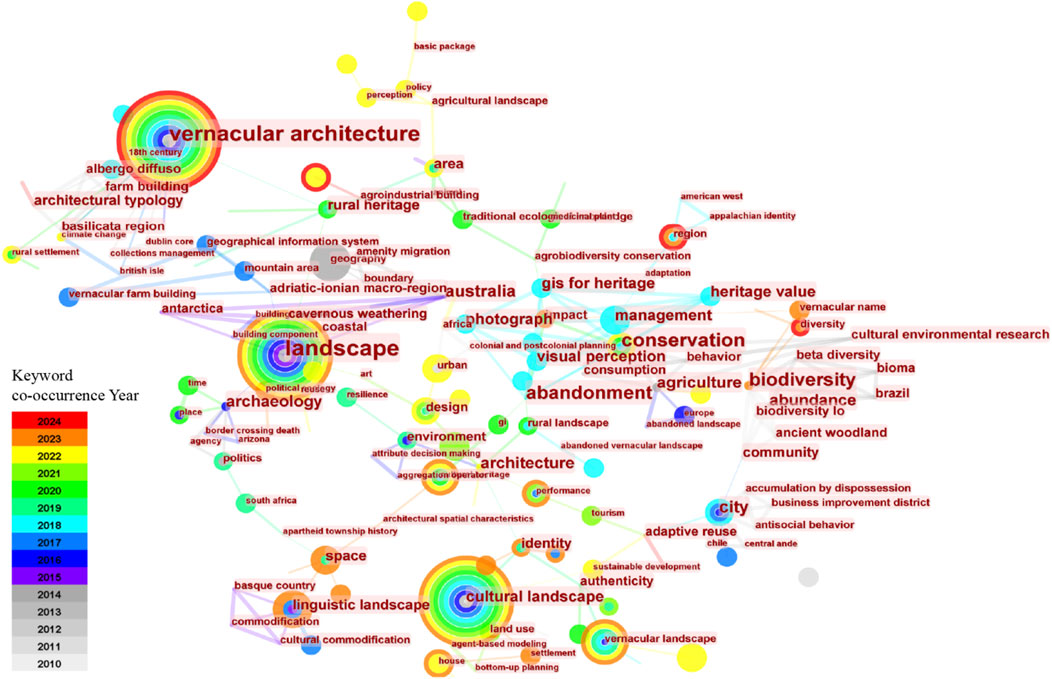

Keyword co-occurrence analysis uses statistical methods to reveal the correlation between different research topics and hot topics in academic research. In this study, we conducted keyword co-occurrence analysis on the vernacular cultural landscape literature using CiteSpace, generating a co-occurrence network, as depicted in Figure 12. The nodes of different colors in the figure represent different research clusters; the size of each node reflects the frequency of keyword occurrence, and the connecting lines represent the co-occurrence intensity of these keywords in the literature.

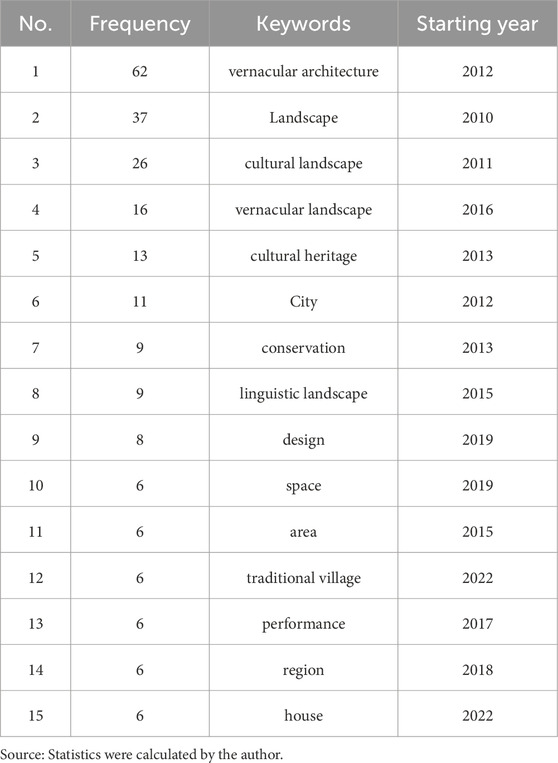

The high-frequency keywords listed in Table 4 show that vernacular architecture is the core research topic in this field, with a frequency of 62, and has become the focus of research since 2012. As the central node in the co-occurrence graph, “vernacular architecture” is closely connected to keywords such as “rural heritage” and “architectural typology”. This shows that researchers pay a great deal of attention to the different types and structures of vernacular buildings, as well as how to protect and reuse them. Around this theme, researchers not only focus on the physical properties of buildings but also focus on their cultural and historical significance, especially the balance between protection and development.

Landscape is another high-frequency keyword, appearing 37 times and dominating research in this field since 2010. The related keywords that appear numerous times include “cultural landscape” (26 times) and “vernacular landscape” (16 times). This shows that researchers are very interested in studying the historical and social value of cultural landscapes as well as how to keep their integrity as they become more modern. The co-occurrence of these keywords indicates the importance of cultural landscape protection as a research direction in this field, particularly in preserving and inheriting rural landscapes amidst rapid urbanization, a topic that has become a focal point of academic discourse.

As research methods become more varied, keywords such as “GIS for heritage”, “management”, “spatial density”, “biodriversity”, and “linguistic landspace” show up in the co-occurrence network. This shows that researchers are paying more and more attention to how to use technology and management strategies to protect cultural heritage. These technologies provide a scientific basis for monitoring, evaluating, and protecting cultural landscapes, as well as promoting the modernization of heritage protection. In particular, the combination of GIS technology and heritage management has made cultural landscape protection no longer limited to physical space maintenance but also includes systematic solutions for data analysis and planning management.

The co-occurrence map also reveals a close relationship between biodiversity, conservation, agriculture, abundance, region, and other keywords, suggesting a gradual expansion of research into ecological and environmental protection issues. In particular, researchers have focused on the interaction between biodiversity and agricultural activities in rural cultural landscapes. How to balance the relationship between human activities and the natural environment through sustainable ecological protection measures is an important trend in current research on cultural landscape protection.

Keywords such as adaptive reuse, identity, and performance indicate that future research will focus more on how to protect cultural heritage and give it new functions through adaptive reuse strategies in the context of modernization. At the same time, the identity and expression of cultural landscapes are also important topics for future research. Researchers will continue to explore how to achieve the goals of cultural heritage protection and sustainable development through an organic combination of architectural design and landscape protection.

In addition, the keyword “linguistic landscape” has gradually increased in frequency since 2015, indicating that researchers have begun to explore the interactive relationship between language, landscape, and cultural identity. This indicates that more scholars are incorporating the linguistic landscape, a crucial component of the cultural landscape, into their research framework, highlighting its unique cultural communication value in the context of globalization.

We can see through keyword co-occurrence analysis that the intersection of vernacular architecture, cultural landscape protection, modern technology, and ecological protection concentrates the research hotspots of the vernacular cultural landscape. By integrating multidisciplinary methods such as architecture, ecology, and sociology, researchers have promoted the in-depth development of research in this field and provided a more systematic and scientific theoretical and practical basis for cultural heritage protection.

4.2 Keyword clustering analysis

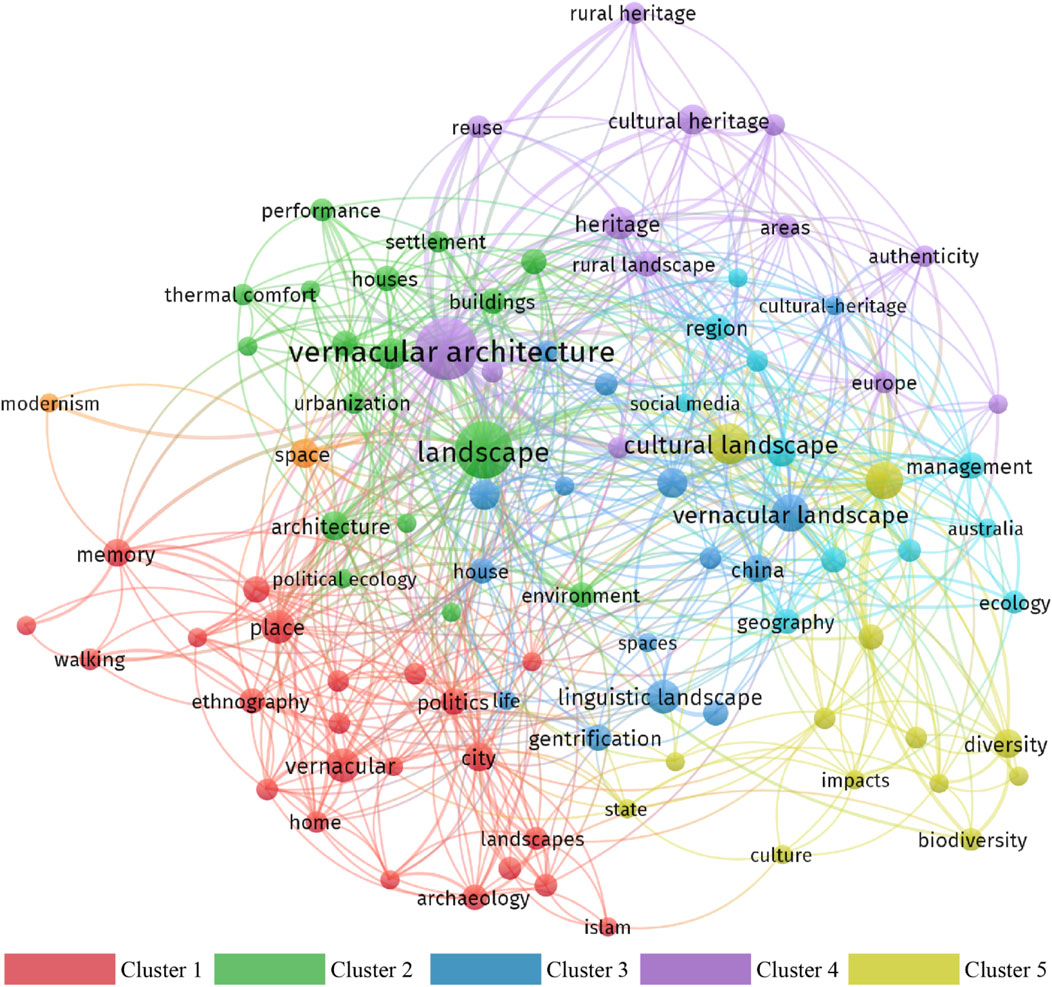

This study used VOSviewer software to perform keyword co-occurrence cluster analysis and displayed the keyword co-occurrence network in the field of vernacular cultural landscape. Each node in the figure represents a keyword, and nodes with different colors represent different research topics or fields. The lines between nodes represent keyword co-occurrence relationships. The more lines there are, the higher the co-occurrence frequency. This study divides keywords into five clustering levels, as shown in Figure 13.

Red: Cluster one mainly focuses on the intersection of social culture and sense of place. Keywords such as “place”, “vernacular”, and “political ecology” show that the research focuses on the interaction between local culture, historical memory, and social life in rural settlements, especially how to maintain their cultural identity in the context of globalization and urbanization. Researchers use qualitative research methods such as ethnography to explore the social and cultural context of these places.

Green: Cluster two focuses on the study of architecture, urbanization, and the living environment. Keywords such as “vernacular architecture” and “urbanization” indicate vernacular architecture’s adaptability in the context of modernization, particularly in the study of thermal comfort and building performance improvement in living environments. These studies investigate how traditional buildings can improve living quality by using modern technology to adapt to urbanization’s needs.

Blue: Cluster three emphasizes the study of the cultural landscape and regional characteristics, especially the protection of the cultural landscape of traditional Chinese villages. Keywords such as “cultural landscape” and “China” suggest that researchers not only prioritize the historical significance of the cultural landscape but also actively explore innovative methods to disseminate and enhance cultural heritage through digital technologies such as “social media”.

Purple: Cluster four focuses on the authenticity and reuse of cultural heritage. Keywords such as “cultural heritage” and “authenticity” indicate how to maintain the cultural value of heritage by using reasonable reuse during the heritage protection process and ensuring the continuity of cultural heritage in the process of modernization.

Yellow: Cluster five is the interaction between cultural landscape and ecological protection. Keywords such as “diversity” and “biodiversity” show that researchers are concerned about how to maintain the healthy development of this ecosystem while protecting the cultural landscape, especially how to achieve the harmonious coexistence of culture and nature within the framework of sustainable development.

The way keywords are related to each other shows that ideas such as vernacular architecture, cultural landscape, heritage protection, and ecological diversity are connected. This shows how broad and cross-disciplinary vernacular cultural landscape research is. These research directions not only explore the material characteristics of traditional architecture and cultural landscapes but also include in-depth studies on social culture, ecological environment, and policy management, providing a multi-angle perspective for the sustainable protection and development of rural settlements.

4.3 Analysis of the time-varying frequency of hot keywords

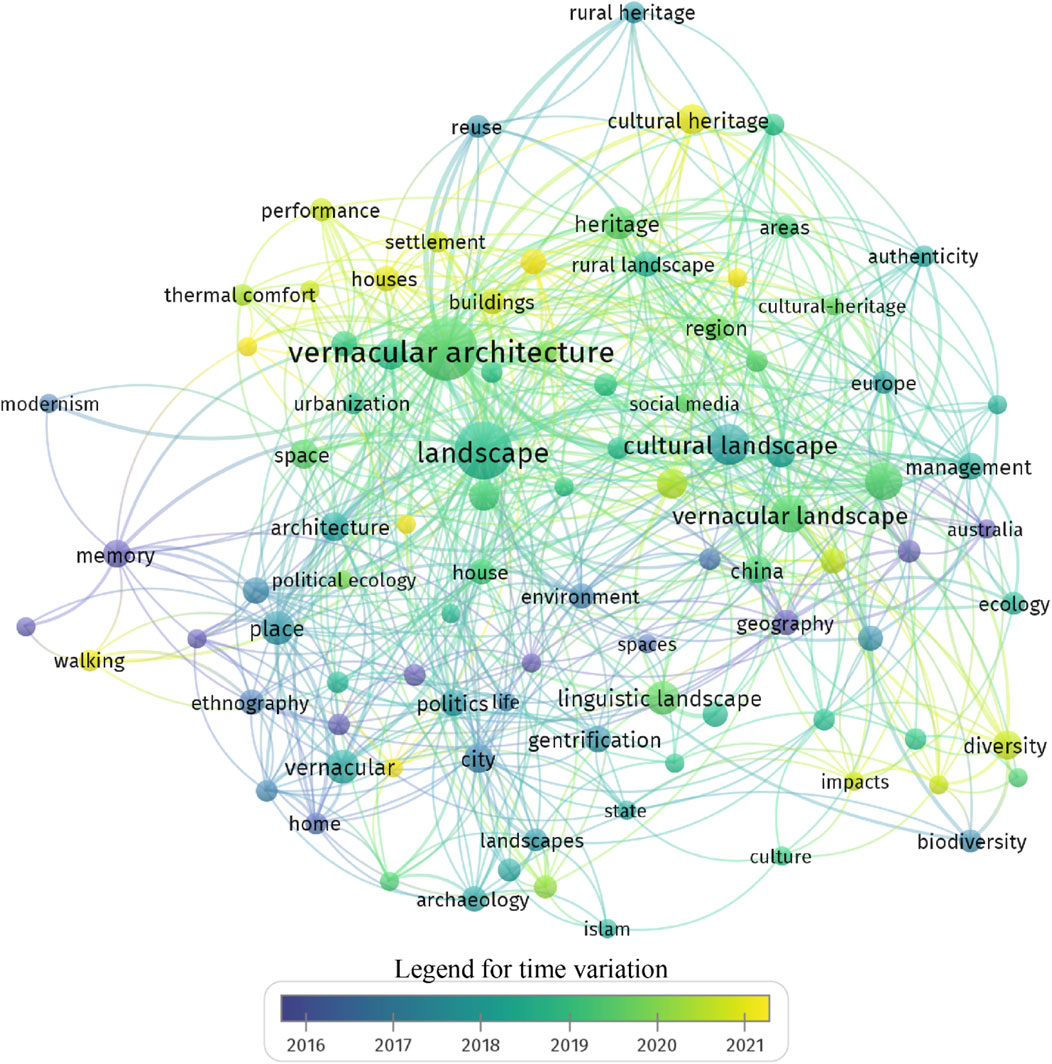

This study divides the time-varying hot keywords into three stages, as shown in Figure 14. The temporal change analysis of keywords shows the evolution of vernacular cultural landscape research, which has gradually shifted from early social and cultural research to a focus on architecture, landscape protection, and ecological sustainability, reflecting the field’s research focus at different historical stages and possible future trends.

Early stage (2010–2016): In the area near 2016 at the bottom of Figure 14, keywords such as ethnography, place, space, vernacular, memory, geography, and home gradually emerged, showing that early research focused more on rural cultural landscape research from the perspective of sociology and anthropology. During this period, researchers mainly focused on how to explore the social and cultural structure of rural settlements and their relationship with sense of place through field surveys, qualitative research, and other methods. This type of research played a foundational role in the social and cultural dimensions of cultural landscapes.

Phase II (2017–2019): As time went on, keywords such as landscape, vernacular architecture, cultural landscape, heritage, and area became the core of this research between 2017 and 2019. During this period, the focus of research shifted to the protection and sustainable development of vernacular architecture and cultural landscape, especially how to preserve and utilize the cultural value of traditional architecture and landscape in the context of modernization. Here, researchers are more concerned with promoting the development of heritage protection practices through management, planning, and other means, emphasizing the combination of technical means and management strategies. The linguistic landscape is another important group of keywords. Research in this field at this time was beginning to explore the relationship between language symbols and cultural landscape, particularly how the language landscape can reflect the local identity and cultural memory in the context of multiculturalism and globalization. The figure also shows the association with keywords such as politics, life, city, and gentrification, indicating that researchers are concerned about social changes and power structures in cultural landscapes.

Phase 3 (2020–2024): The yellow nodes in Figure 14 show the keywords after 2020, reflecting the latest research trends. In hotspots, keywords such as thermal comfort, reuse, diversity, and biodiversity began to appear, indicating that recent research has focused more on environmental factors in cultural landscapes and the physical performance of residential buildings. This is consistent with contemporary society’s focus on sustainability and ecological diversity. In particular, the study of thermal comfort demonstrates how to improve traditional buildings’ living comfort through architectural design and technical means while maintaining their cultural value. After 2020, research on cultural heritage and rural heritage continued to intensify, signaling a growing global awareness of heritage protection and a shift in research focus towards the protection and inheritance of rural cultural heritage through innovative technologies and methods. Furthermore, keywords associated with space utilization and regional research, such as “region” and “space”, also exhibit significant changes, suggesting that researchers are delving deeper into the distribution and evolution of rural landscapes in spatial dimensions.

In summary, the temporal change analysis of keywords shows the evolution of vernacular cultural landscape research, which has gradually shifted from early social and cultural research to a focus on architecture, landscape protection, and ecological sustainability, reflecting the field’s research focus during different historical stages and possible future trends.

4.4 Keyword surge analysis

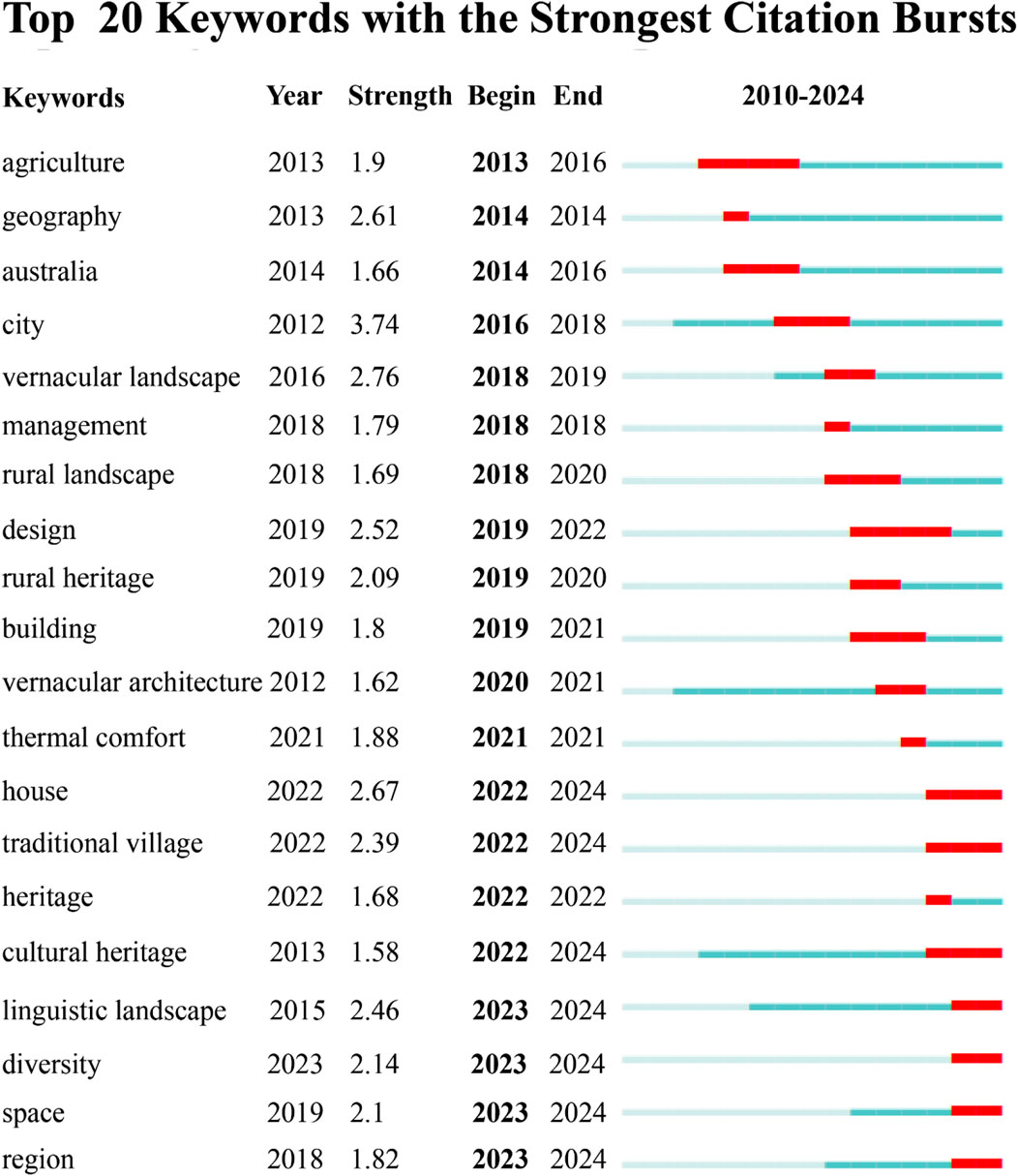

The purpose of keyword temporal mutation analysis is to reveal the dramatic changes in the frequency of citations of specific keywords in a research field within a certain period of time, thereby reflecting the research hotspots and cutting-edge trends in the field. Figure 15 shows the intensity and duration of keyword mutations in research on the vernacular cultural landscape from 2010 to 2024. By analyzing keyword mutations, we can clearly see the evolution of the research focus in this field.

Figure 15. The analysis focuses on the start and end times of the top 20 keyword mutations (image source: drawn by the author).

Early mutation keywords (2013–2016): Agriculture is an early mutation keyword, which began to mutate in 2013 and lasted until 2016, with a mutation intensity of 1.9. This shows that during this period, the relationship between the study of rural settlements and agricultural activities became a hot topic, and researchers may have paid more attention to the impact of agricultural economic activities on cultural landscapes. Geography showed a strong mutation in 2014 (2.61), which also lasted until 2016, showing the importance of geographical perspectives in cultural landscape research. By using spatial analysis methods, researchers were able to reveal the interaction between rural settlements and the geographical environment, promoting the discussion of regional protection and development strategies for traditional villages.

The mid-term mutation keyword (2018–2020) “vernacular landscape” caused a mutation with an intensity of 2.76 in 2018. This meant that researchers started to pay more attention to the cultural and historical value of the vernacular landscape and how to protect it. The co-occurrence of this keyword with “cultural landscape” at that time shows that maintaining the local characteristics and cultural heritage of the landscape has become a major research challenge due to globalization and urbanization. In 2018, management and the rural landscape underwent significant changes, indicating that researchers were increasingly focusing on the sustainable development of cultural heritage through scientific management methods in cultural landscape protection. This trend may be due to the increase in heritage protection projects and the emphasis on the role of management and planning in heritage protection with policy support.

Keywords for recent mutations (2021–2024): Keywords such as thermal comfort and house showed strong mutations in 2021 and 2022, indicating that, in recent years, researchers have gradually shifted their focus to the living quality and comfort of rural buildings, especially how to improve the physical performance of the living environment while retaining the characteristics of traditional buildings. This also reflects that, in the context of rural revitalization, livable villages have become a focus of common concern for policy and academic circles. Traditional village, heritage, and cultural heritage have shown a strong mutation intensity since 2022, indicating that research interest in protecting and inheriting traditional villages and their cultural heritage continues to heat up. With the increasing awareness of global heritage protection, how to protect these traditional cultural carriers by using innovative methods and modern technologies has become a hot topic of discussion in the academic community.

In addition, the keywords highlighted in 2023, such as space and diversity, have a high mutation intensity, indicating that researchers are paying more and more attention to the use of space in rural landscapes and the protection of cultural and ecological diversity. The global sustainable development goals closely align with this trend, reflecting the academic community’s emphasis on diversity protection and spatial planning.

In general, early research hotspots focused on the relationship between rural settlements, agriculture, and the geographical environment. As time went on, research gradually expanded to more diverse topics such as cultural landscape protection, the application of management methods, and the improvement of building physical properties. In particular, in recent years, with the increasing awareness of cultural heritage protection, the protection of traditional villages and cultural landscapes has gradually become a research frontier. In the future, with the advancement of ecological protection, spatial planning, and management technology, research may pay more attention to the sustainability and multifunctional utilization of rural cultural landscapes. Keyword mutation analysis reveals that the research direction in this field has evolved with changing times, expanding from agricultural and geographical perspectives to multidimensional research on cultural heritage, landscape protection, and the living environment. This trend reflects the need of the times for vernacular cultural landscape research to gradually move from a single discipline to an interdisciplinary, comprehensive protection and development strategy.

5 Discussion: the vernacular cultural landscape of traditional villages in qilu cultural district in China

Current academic research on the local cultural landscape of Qilu traditional villages focuses on typical regional culture, typical traditional villages, and typical local landscapes. The traditional villages in the Qilu cultural area are typical case representatives. Existing research has been conducted from three perspectives: architectural discipline perspective, cultural protection perspective, and cultural tourism development perspective. If further divided according to cultural zoning, the research results can be divided into two regions: the Jiaodong Coastal Area and the Peninsula Inland Area.

5.1 Traditional villages in qilu cultural district in China

By using field surveys and historical materials (Figure 3), researchers found that research on “traditional villages” in Shandong began after 2000 and mainly involved architecture, archaeology, culture, tourism, agricultural economy, and other fields. This also shows that the vernacular cultural landscape in the Qilu Cultural District is relatively early in the global process (see Section 3.1), and the exploration in the field of localization is more detailed. The top 20 keywords with the strongest citation bursts in Figure 15 also relate to the majority of these focused fields. Based on different geographical factors and cultural backgrounds, the research scope of traditional villages divides Shandong Province into coastal areas (eastern Shandong area), plain areas (southwestern Shandong, northwestern Shandong), and mountainous areas (central Shandong area). The main fields involved include architectural science, archaeology, tourism, agricultural economy, etc.

5.1.1 Architectural discipline perspective

In the field of architecture, the research on “Qilu Traditional Villages” started with the single architectural form and internal space of residential buildings and gradually progressed to the study of the village’s overall spatial layout, geographical relationships, and folk landscape. During this period, scholar Huang Yongjian put forward the view that the construction principles of traditional village residential space should be “suitable for use” and revealed the historical origins and inheritance significance of traditional residential space forms in ancient villages in Shandong (Huang, 2013). In his research, Li Xiaotong looked at 411″traditional villages” in Shandong Province and used geographic information technology to find out where they were located. He then looked at the overall pattern of where the villages were located and the factors that affected them from a big-picture point of view (Xiaotong et al., 2018). Xiao Mengru conducted in-depth research on how the “grid-type” of the spatial sequence of traditional villages in plain areas evolved and formed (Xiao and Guo, 2020). In his research, Fan Yong clarified the dynamic mechanism of village spatial evolution and its coupling relationship with space, revealing the spatial characteristics, value characteristics, and evolutionary logic of traditional villages (Fan et al., 2023). Furthermore, scholar Nie Yantao pointed out that the distribution of villages shows significant spatial positive correlation agglomeration characteristics, showing obvious high agglomeration and hot and cold zoning in local space; factors that affect the spatial distribution of traditional villages include natural factors such as terrain, altitude, and slope. According to Nie and Shi (2023), social and economic factors play a significant role. Generally speaking, research on traditional villages in the field of architecture mainly focuses on the spatial layout, form, and distribution of traditional villages. Through the layout and distribution characteristics of different traditional villages in Shandong, scholars used different technical means to conduct investigations and analyses and summarized the natural factors and evolutionary logic that affect the spatial development of traditional villages.

5.1.2 Cultural protection perspective

According to the scholars Pan Lusheng and Li Wenhua, we should improve laws related to the protection and development of traditional Chinese villages and establish a large database of these villages to achieve effective results (Pan and Wenhua, 2017). At the same time, Chen Shufei proposed taking the rural revitalization strategy as an opportunity to implement a new path for the protection and development of traditional villages with Shandong characteristics, thereby accelerating the comprehensive revitalization of traditional villages (Chen and Yan, 2019). Scholar Zhang Jian studies effective ways to inherit and update Chinese traditional village landscapes from the perspective of sustainable design (Zhang, 2017). Song Wenpeng used the nearest neighbor index method, kernel density estimation method, and other spatial analysis methods of GIS to show how different factors have changed the layout of traditional villages in Shandong. He did this to help other researchers learn more about how to preserve and pass on the cultural heritage of traditional villages in Shandong (Song et al., 2018). Han Weixuan conducted an analysis of tourism development and village protection, providing detailed strategies, with the aim of achieving the optimal development model that aligns with the concepts of rural revitalization, ecological sustainability, mutual benefit, and win-win outcomes (Han and Liu, 2022). Generally speaking, the protection of traditional villages has been a hot topic in the development of traditional villages in recent years. Scholars use the concept of sustainable development, along with scientific and technological means, to summarize the development characteristics and spatial forms of traditional villages in Shandong. They then establish a targeted development and protection mechanism for the local cultural landscape of these villages, taking into account the unique characteristics of each village.

5.1.3 Cultural tourism development perspective

The scholar Lu Haiyong proposed a path to improve the tourism competitiveness of traditional villages in terms of expanding the total domestic tourism supply in the entire region, improving the quality of tourism product supply, and innovating tourism product supply paths (Lu et al., 2017). Zhang Xingfa proposed corresponding development principles to address issues such as an incorrect understanding of authenticity, repetitive experience forms, and a lack of awareness about village cultural protection during the development process of traditional villages (Zhang et al., 2018). Hao Xiaoshuang elaborated on the many problems that have arisen in the protection and development process of traditional villages. The development of tourism in traditional villages should be based on the inheritance of local historical folk customs and culture (Hao and Liu, 2020). Li Shaoqi used GIS spatial analysis methods to analyze the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of traditional villages and discussed their cultural and tourism-integrated development strategies. Based on the cultural and tourism integration and macro joint perspectives, they proposed a development strategy for traditional villages in Shandong Province from three aspects: the resource level, the development level, and management (Shaoqi et al., 2021). Cheng Jinnan conducted a systematic analysis of traditional villages’ spatial patterns and geographical differentiation characteristics, providing a scientific basis for the excavation and revitalization of traditional villages in Shandong Province (Cheng et al., 2022). In general, the development of cultural tourism has gradually homogenized traditional villages, leading to their uniformity. While scholars and experts have focused on these issues, they have also proposed a solution that revolves around the enhancement of local cultural symbols and regional characteristics. The development of tourism in traditional villages often confronts the same challenges as the preservation of these villages. How to create the village’s regional characteristics and break the trend of homogeneity is the focus of traditional village tourism development and related work.

5.2 Vernacular cultural landscape in qilu cultural district

The research fields of “Qilu vernacular cultural landscape” and “Shandong vernacular cultural landscape” mainly involve architectural science, and there are also a small number of published documents in other fields of physical geography and forestry. By using field investigation and real-case analysis, we divided the research scope (in the field of architecture) based on the geographical factors and cultural background of the Shandong region. We began by analyzing the components of the vernacular cultural landscape, planning and design, ancient and modern evolution, and so on. Much work has gone into planning, protecting, and developing this area.

5.2.1 Vernacular cultural landscape in Jiaodong coastal area