- 1Center for the Study of Chinese Archaeology, Peking University, Beijing, China

- 2School of Archaeology and Museology, Peking University, Beijing, China

- 3Guangzhou Municipal Institute of Cultural Heritage and Archaeology, Guangzhou, China

The transformation from hunter-gathering to farming in the south China coast has always been a conspicuous topic, as its great significance for the understanding of crop dispersal and human migration into southern China and Southeast Asia. It has been primarily assumed that rice was the only crop cultivated by early farmers in this region since 5,000 cal. BP., but the reliability of this speculation remains ambiguous, owing to the lack of systematic evidence. Based on analysis of macroscopic plant remains and phytoliths, as well as AMS radiocarbon dating at the Gancaoling site in Guangdong province, this study demonstrates the emergence of agriculture in the south China coast could be dated back to as early as 4,800–4,600 cal. BP., with the cultivation of rice and foxtail millet. This subsistence strategy change was an integral part of a more comprehensive social transformation, which started a new era of local history. Moreover, this discovery also provides further evidence supporting the universality of mixed farming in southern China and shed new light on the study of agriculture southward dispersal. The crop package of rice and millets possibly spread into the south China coast from Jiangxi via the mountain areas and then into Mainland Southeast Asia by a maritime route along the coastal regions.

Introduction

The transformation from Paleolithic to Neolithic has long been regarded as the most fundamental revolution in the history of human beings (Childe, 1936; Bar-Yosef, 1998; Olsson and Paik, 2016). With the progress of archaeological research in the past decades, it is becoming more evident that this process was not as simple as imagined before. The related innovations, such as agriculture, pottery, ground stone, and sedentism, did not appear simultaneously, and the order of their appearance varied greatly among different regions (e.g., Kuijt and Goring-Morris, 2002; Fuller et al., 2015; Jordan et al., 2016). Ancient people in many areas with the capability of making pottery and ground stone tools still relied on hunter-gathering for their daily food supplies for thousands of years, while others had gone farther and farther along the pathway of food production. Nevertheless, most of these hunter-gathering communities have ultimately been transformed into or replaced by farming societies, leading to the formation of a farming-dominated world (Bellwood, 2005; Ellis et al., 2013; Stephens et al., 2019). Therefore, how these secondary transformations happened is no less important than the origin of the Neolithic lifeway for our understanding of the grand history of human beings.

The south China coast, along with its adjacent Nanling mountain areas, is one of the typical regions for the investigation of this issue. Current evidence of pottery in this region could be dated back to 17,000 cal. BP. from the Qingtang site (Guangdong Provincial Institute of Archaeology and Museology et al., 2019), while other discoveries before 10,000 cal. BP. have also been reported from Zengpiyan, Niulandong and many other cave sites (Zhang, 2002). Ground stones were also widely found here around 15,000–10,000 cal. BP. (Xiang, 2014). By contrast, no domesticated plants were utilized at the same time, and local people had led a hunter-gathering lifestyle for quite a long time (Zhang and Hung, 2012; Yang et al., 2017; Deng et al., 2019). Regarding the later transformation from hunter-gathering to farming, it has been speculated to be after 5,000 cal. BP. (Zhang and Hung, 2010), while recent evidence from Shixia, Laoyuan, and Chaling of this region reveals a later date of 4,500 cal. BP (Yang et al., 2018; Xia et al., 2019). In this case, more systematic work is still needed to clarify the precise time of agriculture emergence and details of farming practice in this region.

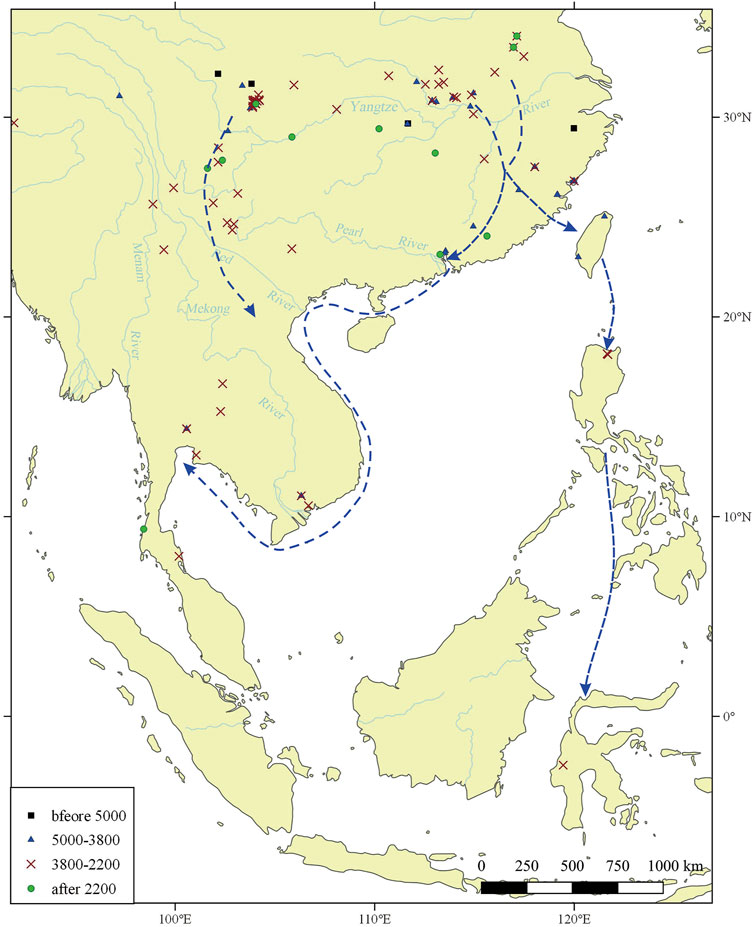

On the other hand, this transformation process in the south China coast is significant for investigating agricultural dispersal into Mainland Southeast Asia. Previous studies have proposed that agriculturalization of Mainland Southeast Asia was based on the introduction of domesticated crops along the terrestrial route from Yunnan province of China, the source region of which could be traced back to Sichuan and then Gansu province in northwest China (Higham, 1996; Higham, 2002; Guedes, 2011; Guedes and Butler, 2014; Deng et al., 2018). However, current earliest evidence of domesticated crops in Mainland Southeast Asia is from the south part of Thailand around 4,500–4,200 cal. BP. (Weber et al., 2010), and it seems possible that rice and millets arrived at the same time in this region. This discovery is almost as old as the earliest evidence from Yunnan (Dal Martello et al., 2018) and thus makes the proposed terrestrial route less convincing. In this case, another maritime route has been raised to reconcile contradictions embedded in current evidence (Higham, 2019; Gao et al., 2020). Nevertheless, because of the absence of mixed farming in the south China coast, the start point of this route is placed further to the southeast coast in Fujian province, the feasibility of which is also not that strong as the distance is too long. Hence, the precise time of agriculture appearance and whether the crop pattern of earliest farming in the south China coast is pure rice or both rice and millet is of great significance to clarify the dispersal of agriculture into Mainland Southeast Asia.

The study presented here is aimed to investigate the general condition of earliest farming in the south China coast, especially the precise time of agriculture emergence, crop pattern and their possible influences on other regions. Systematic samples have been collected from the Gancaoling site of Guangdong province and analyzed by integrating phytoliths, macroscopic plant remains, and direct radiocarbon dating. The new results indicate farming had dispersed into the south China coast around 4,800–4,600 cal. BP. Unlike the previous proposed pure rice agriculture, both rice and foxtail millet were cultivated and consumed by the first farmers in this region. Moreover, this study also emphasizes the significance of the south China coast for the southward dispersal of agriculture into Mainland Southeast Asia.

Materials and Methods

Site Description

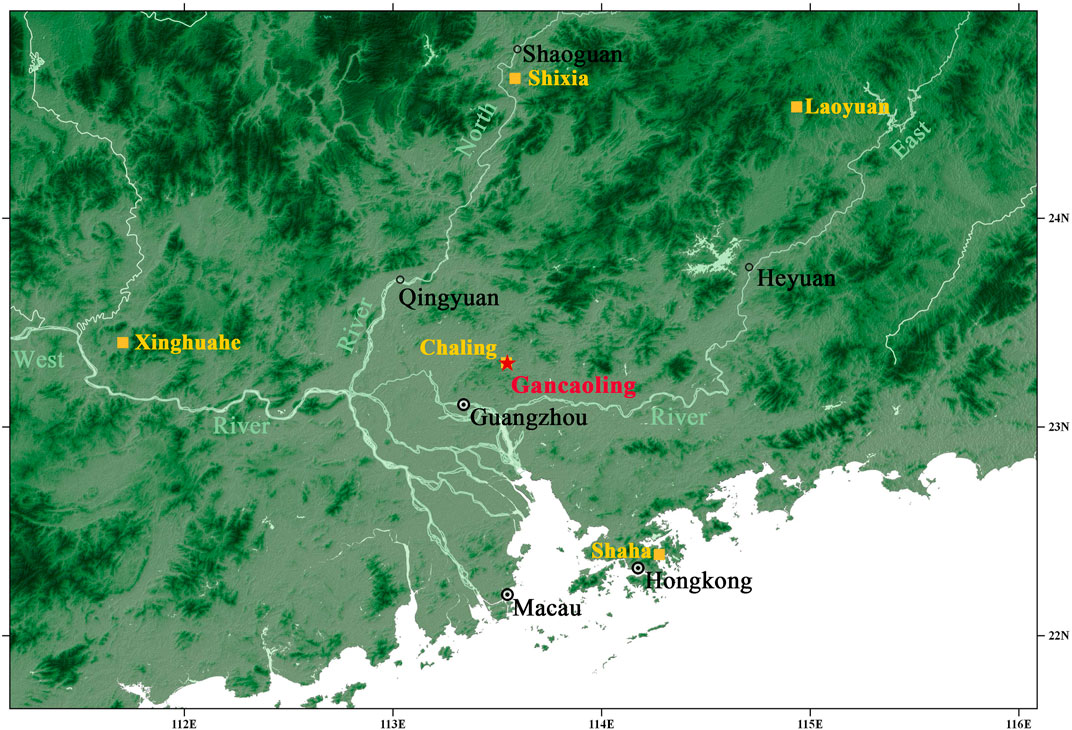

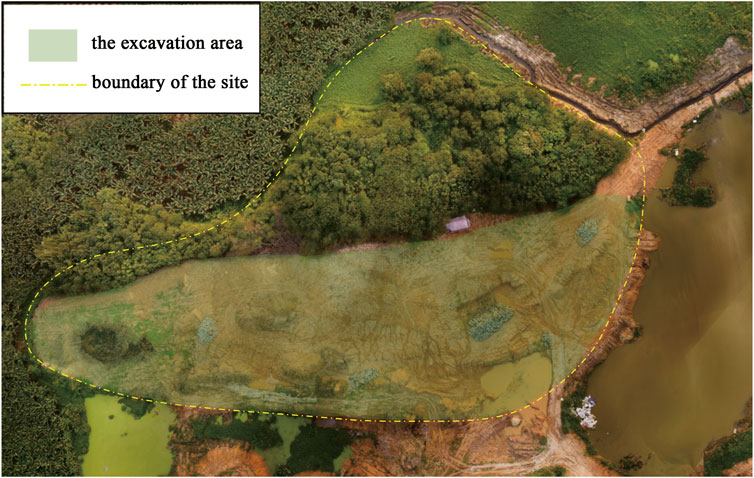

Gancaoling (23°18′15″N, 113°32′53″E) is situated in the northwest edge of the Pearl River delta, with the Nanling Mountains stretching in the north (Figure 1). It was first discovered in 2017 during the prophase archaeological survey for the construction of a new expressway across this region. The whole site covers the top of a small hill, and the total area is nearly 5,000 m2 (Figure 2). After that, a systematic excavation was conducted from 2017 to 2018, covering an area of 3,200 m2. The excavation reveals that cultural deposits of Gancaoling are mainly late Neolithic remains, including 81 pits, 160 graves and 40 post holes, which are possibly ruins of ancient houses or other constructions. From these contexts, large numbers of ceramics, stone tools and a few jade artefacts have been unearthed. Besides, ten graves of the late Warring States period have also been found.

Sample Collection and Processing

For the analysis of plant remains, 213.5 L of bulk samples were collected from 12 contexts during the excavation, 11 of which were pits with refilled daily refuse and one was earth fill of a tomb. Before being processed, a small sub-sample of roughly 50 ml soils was taken out from each sample and saved for phytolith analysis (except for contexts H55 and M50). The rest sediments were floated at the site using flotation buckets (Pearsall, 2000), and the afloat macroscopic plant remains were collected by mesh bags with 300 × 300 μm2 apertures. All floats were then dried in shade and sent to the Archaeobotany Lab of Peking University for further analysis. Seeds, fruits and other parts of plant remains were sorted and identified under a stereomicroscope at 10–20× magnification, according to modern collections and published criteria (Wang, 1990; Guo, 2009; Nesbitt, 2016; Cappers and Bekker, 2022).

Phytolith samples were processed referring to established procedures with slight modifications (Pearsall, 2000; Lu et al., 2002). For each sample, 2 g small sample was weighed and treated with 30% H2O2 to remove organic matter. After three distilled water rinses, 15% HCl was used to remove carbonates. With another three distilled water rinses, phytoliths were separated from the sediments using heavy liquid (ZnBr2, 2.35 g/cm3) floatation. The suspension with separated phytoliths was removed into a new tube and washed three times with distilled water. It was then mounted on a slide with Canada Balsam. After air drying, phytoliths of each slide were identified and counted under an optical microscope at 400× magnification according to published references and criteria (Wang and Lu, 1992; Lu et al., 2002; Ball et al., 2016). For each sample, at least 500 phytoliths were recorded.

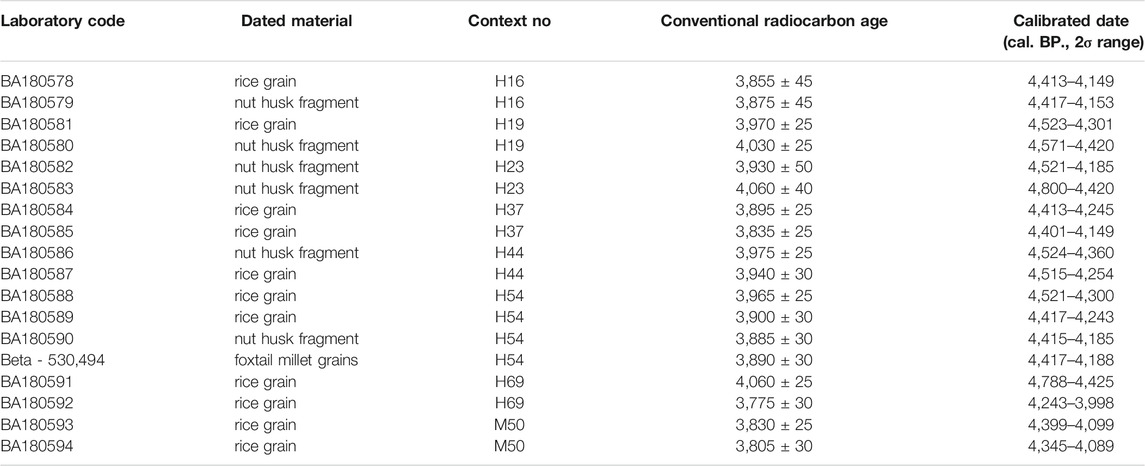

To detect the precise date of each context and chronology of the Gancaoling site, at least two dating samples were selected from each context and sent to the Laboratory of Radiocarbon Dating in Peking University and Beta Analytic Testing Laboratory for direct accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dating (Table 1). In total, 18 samples were tested, and most of the specimens were single rice grain or nut husk fragment. Only in the case of one sample, four foxtail millet grains from context H54 were combined to ensure enough carbon after pre-treatment.

TABLE 1. AMS radiocarbon dating results from the Gancaoling site (All dates are calibrated by OxCal v4.4.4, using the IntCal 20 Atmospheric curve).

Results

AMS Radiocarbon Dating Results

All samples processed in this study yielded radiocarbon dates successfully. These dates were calibrated by OxCal 4.4 (Bronk Ramsey, 2009), using the IntCal20 atmospheric curve (Reimer et al., 2020), and presented in Table 1. Comparison of results from each context suggests that most of them are highly consistent with each other. According to the dating results, the sampled contexts of Gancaoling generally could be divided into two groups. The dates of the first group are concentrated in the range of 4,600–4,400 cal. BP. Whereas only contexts H19 and H44 could be incorporated into this group. The remaining contexts are all possibly formed a little bit later, around 4,400–4,200 cal. BP., while a few contexts like M50 and H60 could be as late as 4,000 cal. BP. with relatively low probability. Overall, it could be concluded that late Neolithic human activities at this site lasted for hundreds of years, in the range of 4,600 to 4,100 cal. BP., with a very low probability reaching 4,800 cal. BP.

Phytoliths

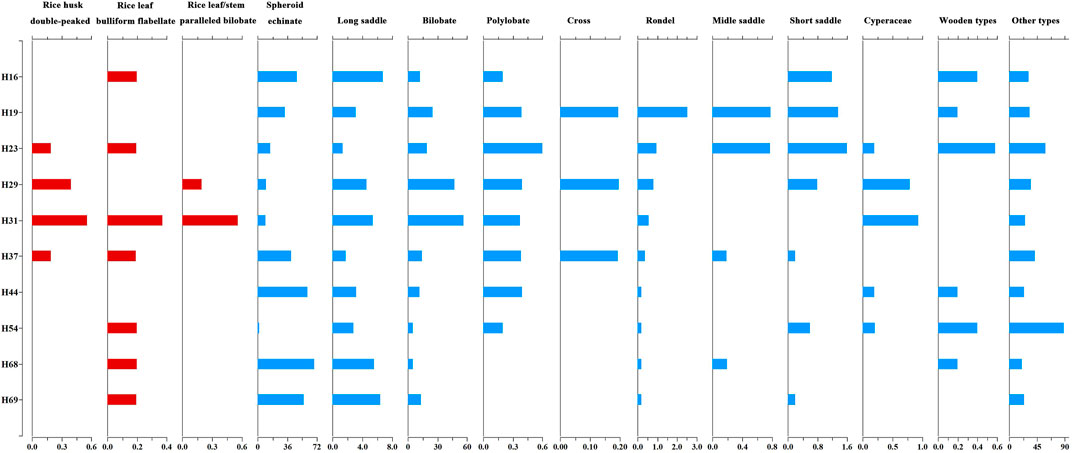

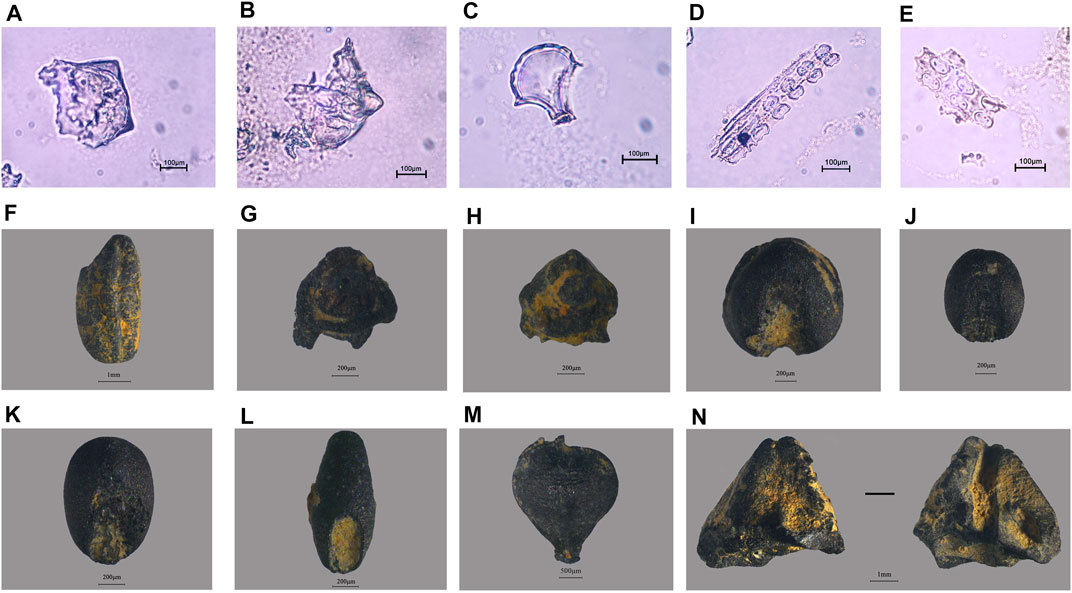

The preservation condition of Phytoliths in all samples of Gancaoling was relatively poor, many of which were eroded and not easy to be precisely identified. The only crop found in phytolith records of Gancaoling was rice, including double-peaked type from rice grain husk, bulliform flabellate from rice leaf, and paralleled bilobate from rice leaf or stem (Figures 3A–E). However, quantities of these identifiable rice morphotypes were deficient, and they were sparsely found in 8 samples, comprising 0.2–0.6% of all phytolith remains in each sample (Figure 4, Supplementary Table S1).

FIGURE 3. Phytoliths and macroscopic plants remains from Gancaoling [(A,B). double-peaked type; (C). rice bulliform flabellate; (D,E). paralleled bilobate; (F). rice grain; (G). rice spikelet base, non-shattering type; (H). rice spikelet base, immature type; (I). foxtail millet mature grain; (J). foxtail millet immature grain; (K). Setaria sp.; (L). Digitaria sp; (M). Scirpus sp; (N). Canarium sp., endocarp fragment].

Besides of these rice remains, 16 morphotypes have been recorded. The most abundant type was spheroid echinate phytolith yielded from palms. It has been found in all contexts, and the highest proportion is 68.8%. Besides, the proportion of bilobate type was also quite high, most of which was more than 10%, and the highest one was 56.1%. Other morphotypes like polylobate and cross from Panicoideae, rondel from pooideae, long saddle from bamboo, middle saddle from Arundinoideae, short saddle from Chloridoideae, and Cyperaceae type, have also been recorded in most samples with quite low proportion. Besides, other common types, such as blocky, tracheary annulate, elongate dentate, elongate entire and acute bulbosus, have been widely found in all samples, but none of them could be identified explicitly to genera level.

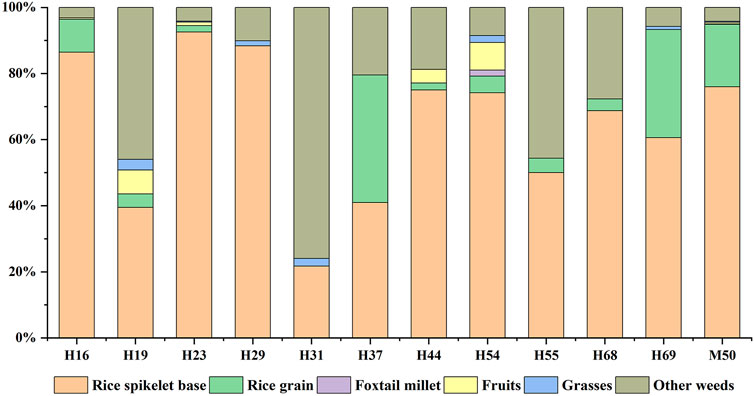

Macroscopic Plant Remains

Macroscopic plant remains were generally not rich in the 12 sampled contexts of Gancaoling (Supplementary Table S2). In total, 3,373 seeds, fruits and other parts of plants have been recovered, and the average density was only 15.7 specimens per litre. Moreover, there was a significant disparity in density among different contexts, with the highest one reaching 52.3 per litre, and the lowest one was only 3.3 per litre. Overall, 15 taxa of plants have been recognized into genera, species, or family level, while a portion of specimens have not been identified. All these remains could be generally grouped into four categories: crops, fruits, grasses, and weeds (Figure 5).

Rice (Oryza sativa) was the most common crop in Gancaoling, and has been found in all contexts sampled in this study. These remains comprised rice grains (Figure 3F) and fragments, rice spikelet bases (Figures 3G,H) and isolated rice grain embryos. Specifically, rice grain fragments were classified into large fragments (larger than half grains), small fragments (smaller than half grains but larger than 1 mm) and tiny fragments (smaller than 1 mm), according to their preservation conditions. According to established criteria, the rice spikelet bases of Gancaoling could also be divided into non-shattering and immature types (Fuller et al., 2009), and 99.29% of them are non-shattering, suggesting they were domesticated. These rice remains in total took up 83.55% of macroscopic plant remains from Gancaoling, with 50 grains, 498 grain fragments, one isolated rice embryo and 2,255 spikelet bases. Foxtail millet (Setaria italica) was another crop found in Gancaoling (Figure 3). It was obviously not widely utilized in the late Neolithic period and has only been found in context H54 and M50, including seven mature grains (Figure 3l) and eight immature ones (Figure 3J).

Fruits were not common at Gancaling, and Canarium sp. (Figure 3N) and Sambucus sp. were the only two identifiable fruits. 77 nutshell fragments of Canarium sp. have been found in 5 contexts (Supplementary Table S2), while only one seed of Sambucus sp. appeared in context H19. Besides, ten kinds of grasses and other weeds have been recorded, including Setaria sp. (Figure 3K), Digitaria sp. (Figure 3L), Eleusine indica, Scirpus sp. (Figure 3M), Polygonum sp., and Brassicaceae. However, their quantities were generally quite limited.

Discussion

Subsistence Transformation and Social Shift in the Late Neolithic of South China Coast

Located far from the two agriculture origin centres of China, the Neolithic subsistence strategy in the south China coast has been a conspicuous topic and stimulated different hypotheses. Because of its special environment settings and natural resources, this region has been proposed as the third agriculture origin centre in China, mainly based on roots and tubers, such as taro (Zhao, 2011). While more scholars tend to believe ancient people here were engaged primarily in hunting, fishing and gathering (Chang, 1969; Higham, 2006; Zhang and Hung, 2012). A recent case study at the Xincun site reveals that wild plants like sago-palm, bananas, freshwater roots and tubers were processed by local people as recently as 5,000 cal. BP or even later (Yang et al., 2013). Another research also suggests that tree fruit, especially Canarium, was widely utilized in the Lingnan region (Nanling Mountains and areas to the south, especially the Pearl River valley), Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands (Deng et al., 2019). No matter these plant resources were totally wild or partly cultivated, it is generally agreed that cereal agriculture was introduced into this region during the late Neolithic period and triggered a groundbreaking social change in local history.

Direct evidence of prehistoric agriculture has long been inadequate in the Lingnan region. The first discovery of such evidence was from the Shixia site in the mountain area, where rice grains and impressions were recovered in two phases, and the earliest one was believed to be no later than 5,000 cal. BP (Yang, 1978; Zhang et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2017). Other occasional discoveries have also been reported from Xinghuahe, Guye in Guangdong and Shaha in Hongkong (Lu et al., 2005; Xiang and Yao, 2006; Relics from the South, 2007). Overall, it is generally recognized that rice farming in this region began around 5,000 cal. BP. and facilitated the later development of local societies (Zhang and Hung, 2010), while a few scholars argue for an earlier emergence of rice agriculture during the Xiantouling culture period (ca. 7,000–6,000 cal. BP.) (Bellwood, 2005). However, all these remains have not been directly dated, and a later re-examination of rice remains from the Guye site reveals none of them was older than 300 years, which were obviously later intrusions (Yang et al., 2017). Therefore, without scientifically rigorous collection of plant remains and direct dating, the emergence of farming and the associated crop pattern in the south China coast is still vague and imprecise.

This condition has been slightly improved with new efforts in the past few years. 20 macroscopic plant remains have been recovered from 6 contexts of the Chaling site, in which 6 were rice grains and one was rice spikelet base. Two rice grains were directly dated to 4,526–4,417 cal. BP. and 4,429–4,248 cal. BP. respectively. Phytolith analysis also disclosed different morphotypes of rice phytoliths from the same site (Xia et al., 2019). Another study also provided phytolith evidence of rice consumption at Laoyuan and Chaling and one direct date of rice grain, which is 4,419–4,246 cal. BP. (Yang et al., 2018). Even so, these pieces of evidence are still too limited to answer this question.

The present study at Gancaoling, for the first time, provided solid evidence and renovated our knowledge on the earliest farming practice in the south China coast. A significant difference from previous understanding is that the earliest agriculture here was not pure rice farming but mixed rice and foxtail millet. The assemblages of macroscopic plant remains clearly demonstrated foxtail millet was cultivated along with rice by first farmers in this region, although rice was no doubt the major crop at that time (Figure 5). Furthermore, the presence of large quantities of rice spikelet bases suggested the existence of rice processing activities at the site. Further evidence of local cultivation and processing has also been provided by phytolith morphotypes from different parts of rice, like leaves, stems and grain husks (Figure 4). Combined with the systematic AMS radiocarbon dates, it could be confirmed that around 4,800–4,600 cal. BP. rice and foxtail millet had already been cultivated in the south China coast.

Another remarkable discovery from Gancaoling is the appearance of Canarium endocarp fragments. Previous research has revealed that Canarium was a vital food resource in Southern China and the contemporary Asia-Pacific region before the introduction of cereal crops. People used to crack the fruit stones and consume the kernels in these hunter-gathering sites (Deng et al., 2019). The new discovery from Gancaoling reminds us that the agriculturalization of Southern China was possibly not an abrupt substitution of exotic technologies for old traditions. On the contrary, traditional foodways quite possibly continued for some time after the introduction of agriculture. Thus, complicated interactions and competitions could be expected behind this process, especially when considering that fishing and hunting had long been the primary way of obtaining animal resources even until the Bronze age (Yu, 2018).

Along with the adoption of agriculture, systematic changes have also happened in other aspects of local society (Li and Zhang, 2021). As pointed out by many scholars, the introduction of farming practice in the south China coast was possibly accompanied by human migrations from the Yangtze valley. A noticeable change is that previous flexed-position burial traditions, which was prevalent in hunter-gathering communities of Southern China and other adjacent regions, had been replaced by extended burials (Hung, 2019). Analysis of skeletal remains, especially craniometrics, also suggests distinct physical characters from previous hunter-gathering populations, which should be caused by contributions of large scale immigrants (Matsumura et al., 2019). These speculations could further be supported by recent progress of ancient DNA studies in southern China, which also argued for a mixture of native hunter-gatherers and migrants from the Yangtze valley (Yang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021). The mixture model instead of the totally replacement model of population also agrees well with the continuity of traditional foodways like Canarium utilization.

With the development of farming, the size of local population also increased drastically after 6,000 cal. BP., as indicated by the number of archaeological sites. For instance, 265 sites of this period have been discovered in the regional survey of the Liuxi River valley, a tributary of the Pearl River, which is several times of the total number of archaeological sites dated to 7,000–5,000 cal. BP. in the whole Pearl River delta (Han and Xu, 2017). These sites were usually around 5,000 m2 or smaller, while some regional centres like Shixia and Yanshanzhai emerged in this period, covering 30,000–50,000 m2 (Guangdong Provincial Institute of Archaeology and Museology et al., 2014). Social differentiations were not only embodied in the divergence among different settlements but also within these communities. Large tombs with rich funerary objects have been found in these regional centres and normal settlements like Gancaoling (Guangdong Provincial Institute of Archaeology and Museology et al., 2014; Li and Zhang, 2021). Meanwhile, jade artefacts such as Cong and Yue of the Liangzhu style had been incorporated into local belief and ritual systems and used as an expression of social status by elites (Tang et al., 2019; Li and Zhang, 2021).

Overall, the adoption of farming is part of a more comprehensive social change in the south China coast around 5,000 cal. BP., which opened a new era for the development of local societies. It was also in this period, the technology of pottery making developed rapidly and led to the invention of stamped hard pottery (Li, 2013). Thereafter, this region, together with Fujian and Jiangxi, became the innovation centre of ceramic technologies and played a new role in the interregional interactions of ancient China.

The Role of South China Coast in the Southward Dispersal of Agriculture

With advances in archaeobotanical research in the past decades, it is becoming more and more apparent that interactions between the two agriculture origin centres in China happened around 7,500 cal. BP., much earlier than expected before (Zhang et al., 2012; Bestel et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2019). At least around 6,000 cal. BP., foxtail millet had spread into the Yangtze River valley, as indicated by discoveries from the Chengtoushan site (Nasu et al., 2007; Nasu et al., 2012). Plant remains from other parts of Southern China like Jiangxi, Fujian and Taiwan also demonstrated millets were cultivated in small scale along with rice in the late Neolithic period, and the universality of millet cultivation in Southern China has been grossly underestimated before (Tsang et al., 2017; Deng et al., 2018; Ge et al., 2019; Deng et al., 2020; Dai et al., 2021). Therefore, it has been further speculated that millets were accepted by all agricultural regions of southern China in the late Neolithic period, except for the plain areas of the lower Yangtze valley (Deng et al., 2018). Whereas, direct evidence is still absent in many related regions, one of which is the south China coast. Thus, the discovery from Gancaoling again adds new evidence to this hypothesis and shed new light on the reconstruction of the southward dispersal of agriculture.

According to comparisons of pottery styles and other material remains from the south China coast and surrounding regions, external communications of this region show clear periodic features. Around 7,000–6,000 cal. BP., the most representative archaeological culture in this region is the Xiantouling culture, sites with associated remains of which are concentrated in the Pearl River delta (Yang et al., 2015). Material remains from this culture group are famous for their finely made potteries, most of which are with painted or punctated decorations (Shenzhen Municipal Institute of Archaeology and Museology, 2013). These remains resembled in features of potteries prevalent in contemporary archaeological cultures of Hunan province, like Gaomiao, Tangjiagang and Daxi (He, 1994). As a result, it is generally agreed that the main channel of external communication between the south China coast and the northerly regions was through the northwest route with Hunan. Another noticeable point is that although rice agriculture had well developed in Hunan province no later than 8,500 cal. BP., farming had not been introduced southward in this period (Zhang and Pei, 1997). Similar conditions could also be observed in the textile materials. Unlike the spinning technologies in Hunan province and other parts of Yangtze valley as indicated by the common use of spindle whorls, ancient residents in the south China coast still used barkcloth instead (Tang, 2003).

After 6,000 cal. BP., the influence from Hunan declined dramatically, while interregional connection through the southeast channel got its start. Comparison of pottery assemblages and morphological features reveals a strong impact of the Fanchengdui culture in Jiangxi province on the Shixia culture and contemporary communities in the coastal region (Li et al., 1989; He, 2010; Li, 2019). Under this background, the introduction of farming was accomplished as an integral part of interregional communications. Therefore, it could be determined that the southward dispersal of rice and foxtail millet was through the mountain areas between Jiangxi and Guandong, just as proposed before (Deng et al., 2018; Deng et al., 2020). However, different from the previous interactions during the Xiantouling period, this transformation seemed more radical and affected all sides of local society. No wonder it is speculated that there were large amounts of immigrants as stated above (Matsumura et al., 2019).

The south China coast is not only a receiver of farming technologies, but also an exporter in a vaster regional configuration. As an integral part of the coastal regions facing Southeast Asia and the Pacific islands, this region has been proposed as one of the possible homeland areas of Austronesian people and agriculture in Island Southeast Asia (Bellwood, 2005; Tsang, 2005). Unfortunately, little evidence has been obtained to support this speculation, while an alternative route from the southeast China coast via Taiwan into northern Luzon is preferred (Bellwood and Dizon, 2008; Hung, 2008). Nevertheless, the possible contribution of the south China coast to the agriculturalization of Mainland Southeast Asia need more attentions. In a regular reconstruction of farming dispersal into Mainland Southeast Asia, a terrestrial route from Yunnan and Guangxi has been mentioned frequently (Higham, 1996; Higham, 2002; Deng et al., 2018). However, the existence of farming practice prior to 4,000 cal. BP. in the south part of Yunnan and Guangxi remains questionable, and so is this proposed route. By contrast, in the coastal region of Vietnam and Thailand, some discoveries of rice and/or millets dated back to 4,500–4,000 cal. BP. have been reported, such as An Son, Loc Giang and Non Pa Wai, indicating a possible maritime route for the southward dispersal of agriculture into this region (Weber et al., 2010; Barron et al., 2017). Given the fact that agriculture emergence in Guangxi happened in the Bronze Age and the co-occurrence of rice and foxtail millet in the Pearl River delta (Deng et al., 2019), the nearest start point of this route should be in the south part of Guangdong province, and thus supporting the significance of this region in the southward dispersal of agriculture (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6. The main southward dispersal routes of agriculture from Yangtze valley into southern China and Southeast Asia.

Conclusion

With systematic archaeobotanical evidence and direct AMS radiocarbon dating, this study demonstrated that agriculture in the south China coast emerged around 4,800–4,600 cal. BP. Different from the previous assumption of pure rice farming, first farmers in this region cultivated rice together with a small portion of foxtail millet as suggested by plant assemblages from Gancaoling. In addition, with the introduction of agriculture, the former hunter-gathering tradition, such as the utilization of Canarium nut, had been maintained for a while, and this transformation possibly happened in a relatively gradual and moderate way, especially when considering the long-lasting utilization of wild mammals, fish and shellfish. Even though, it still needs to be noticed that thorough social change had happened around 5,000 cal. BP. in this region, as reflected in many aspects of local society, like settlement pattern and differentiation, burial practice, ritual and belief system, and quite possibly large amounts of immigrants input.

The new results also provide new evidence supporting the universality of mixed farming in the late Neolithic period of southern China. An interregional comparison reveals this region was not only a receiver of farming technologies but also possibly a junction point on the southward dispersal of agriculture. A package of rice and millets was introduced into this region from Jiangxi Province via the mountain areas and further dispersed into Mainland Southeast Asia along a maritime route. Whereas, to confirm this hypothesis, more targeted work is still needed in the coastal regions of Mainland Southeast, especially Vietnam.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

ZD and QZ designed the study. QZ and BH conducted archaeological excavation and sample collection. ZD and MZ completed sample processing and identification. ZD analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. T2192953, 41872027), the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDB26000000), the National Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. 2020YFC1521603, 2020YFC1521606).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feart.2022.858492/full#supplementary-material

References

Ball, T., Chandler-Ezell, K., Dickau, R., Duncan, N., Hart, T. C., Iriarte, J., et al. (2016). Phytoliths as a Tool for Investigations of Agricultural Origins and Dispersals Around the World. J. Archaeol. Sci. 68, 32–45. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2015.08.010

Bar-Yosef, O. (1998). On the Nature of Transitions: the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution. Camb. Archaeol. J. 8 (2), 141–163. doi:10.1017/s0959774300001815

Barron, A., Turner, M., Beeching, L., Bellwood, P., Piper, P., Grono, E., et al. (2017). MicroCT Reveals Domesticated rice (Oryza Sativa) within Pottery Sherds from Early Neolithic Sites (4150–3265 Cal BP.) in Southeast Asia. Sci. Rep. 7:7410. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-04338-9

Bellwood, P., and Dizon, E. Z. (2008). “Austronesian Cultural Origins: Out of Taiwan, via the Batanes Islands, and Onwards to Western Polynesia, in Past Human Migrations in East Asia,” in Past human migrations in East Asia: matching archaeology, linguistics and genetics. Editor A. Sanchez-Mazas, R. Blench, M. D. Ross, I. Peiros, and M. Lin (New York: Routledge), 1-17.

Bestel, S., Bao, Y., Zhong, H., Chen, X., and Liu, L. (2018). Wild Plant Use and Multi-Cropping at the Early Neolithic Zhuzhai Site in the Middle Yellow River Region, China. The Holocene 28 (2), 195–207. doi:10.1177/0959683617721328

Bronk Ramsey, C. (2009). Bayesian Analysis of Radiocarbon Dates. Radiocarbon 51 (1), 337–360. doi:10.1017/s0033822200033865

Cappers, R. T., and Bekker, R. M. (2022). A Manual for the Identification of Plant Seeds and Fruits. Groningen: Barkhuis.

Dai, J., Cai, X., Jin, J., Ge, W., Huang, Y., Wu, W., et al. (2021). Earliest Arrival of Millet in the South China Coast Dating Back to 5,500 Years Ago. J. Archaeological Sci. 129, 105356. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2021.105356

Dal Martello, R., Min, R., Stevens, C., Higham, C., Higham, T., Qin, L., et al. (2018). Early Agriculture at the Crossroads of China and Southeast Asia: Archaeobotanical Evidence and Radiocarbon Dates from Baiyangcun, Yunnan. J. Archaeological Sci. Rep. 20, 711–721. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.06.005

Deng, Z., Hung, H.-c., Fan, X., Huang, Y., and Lu, H. (2018). The Ancient Dispersal of Millets in Southern China: New Archaeological Evidence. The Holocene 28 (1), 34–43. doi:10.1177/0959683617714603

Deng, Z., Hung, H.-c., Li, Z., Carson, M. T., Huang, Q., Huang, Y., et al. (2019). Food and Ritual Resources in hunter-gatherer Societies: Canarium Nuts in Southern China and beyond. Antiquity 93 (372), 1460–1478. doi:10.15184/aqy.2019.173

Deng, Z., Yan, Z., and Yu, Z. (2020). Bridging the gap on the Southward Dispersal Route of Agriculture in China: New Evidences from the Guodishan Site, Jiangxi Province. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 12:151. doi:10.1007/s12520-020-01117-y

Ellis, E. C., Kaplan, J. O., Fuller, D. Q., Vavrus, S., Klein Goldewijk, K., and Verburg, P. H. (2013). Used Planet: A Global History. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110 (20), 7978–7985. doi:10.1073/pnas.1217241110

Fuller, D. Q., Kingwell-Banham, E., Lucas, L., Murphy, C., and Stevens, C. J. (2015). Comparing Pathways to Agriculture. Archaeol. Int. 18, 61. doi:10.5334/ai.1808

Fuller, D. Q., Qin, L., Zheng, Y., Zhao, Z., Chen, X., Hosoya, L. A., et al. (2009). The Domestication Process and Domestication Rate in Rice: Spikelet Bases from the Lower Yangtze. Science 323 (5921), 1607–1610. doi:10.1126/science.1166605

Gao, Y., Dong, G., Yang, X., and Chen, F. (2020). A Review on the Spread of Prehistoric Agriculture from Southern China to Mainland Southeast Asia. Sci. China Earth Sci. 63 (5), 615–625. doi:10.1007/s11430-019-9552-5

Ge, W., Yang, S., Chen, Y., Dong, S., Jiao, T., Wang, M., et al. (2019). Investigating the Late Neolithic Millet Agriculture in Southeast China: New Multidisciplinary Evidences. Quat. Int. 529, 18–24. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2019.01.007

Guangdong Provincial Institute of Archaeology and Museology, School of archaeology and museology of Peking University and Museum of Yingde City (2019). The Qingtang Site in Yingde City, 7, 3-15. Archaeo. (Kaogu), (in Chinese).

Guangdong Provincial Institute of Archaeology and Museology, Guangdong Museum, and Qujiang Museum (2014). The Shixia Site: Report of the Archaeological Excavation in 1973-1978. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press.

Guedes, J. D. A. (2011). Millets, Rice, Social Complexity, and the Spread of Agriculture to the Chengdu Plain and Southwest China. Rice 4 (3), 104–113. doi:10.1007/s12284-011-9071-1

Guedes, J. D. A., and Butler, E. E. (2014). Modeling Constraints on the Spread of Agriculture to Southwest China with thermal Niche Models. Quat. Int. 349 (2014), 29–41. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.08.003

Guo, Q. (2009). The Illustrated Seeds of Chinese Medicinal Plants. Beijing: Agricultural Publishing House.

Han, W., and Xu, Y. (2017). Report of the Archaeologcial Surevey in the Liuxi River Vally of Conghua, Guangzhou City. Guangzhou: Guangzhou Press.

He, G. (2010). Transformation of the Spatial Pattern of Neolithic Cultures in the Lingnan Region. Southeast Cul. (Dong Nan Wen Hua) 6, 75–81.

He, J. (1994). Prehistoric Painted Pottery of the Pearl River Mouth and Daxi Culture," in Ancient Cultures of south China and Neighbouring Regions. Editor C. Tang (Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong), 321–330.

Higham, C. F. W. (2006). Crossing National Boundaries: Southern China and Southeast Asia in Prehistory," in Uncovering Southeast Asia’s Past: Selected Papers from the 10th International Conference of the European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists, Editor E.A.Bacus, I.Glover & V.C.Pigott. (Singpore: NUS Press.), 13–21.

Higham, C. F. W. (2019). “A Maritime Route Brought First Farmers to Mainland Southeast Asia,” in Prehistoric Maritime Cultures and Seafaring in East Asia. Editor C. Wu & B.V. Rolett. (Singapore: Springer), 41–52. doi:10.1007/978-981-32-9256-7_2

Hung, H. C. (2019). Prosperity and Complexity without Farming: the South China Coast, C. 5000-3000 BC. Antiquity 93 (368), 325–341. doi:10.15184/aqy.2018.188

Hung, H. C. (2008). Migration an Cultural Interaction in Southern Coastal China, Taiwan and the Northern Philippines, 3000 BC to AD 100: The Early History of the Austronesian-Speaking Populations [dissertation]. Canberra: Australian National University.

Jordan, P., Gibbs, K., Hommel, P., Piezonka, H., Silva, F., and Steele, J. (2016). Modelling the Diffusion of Pottery Technologies across Afro-Eurasia: Emerging Insights and Future Research. Antiquity 90 (351), 590–603. doi:10.15184/aqy.2016.68

Kuijt, I., and Goring-Morris, N. (2002). Foraging, Farming, and Social Complexity in the Pre-pottery Neolithic of the Southern Levant: a Review and Synthesis. J. World Prehist 16 (4), 361–440. doi:10.1023/a:1022973114090

Li, Y. (2013). A Preliminary Research of the Hutoupu Culture. Coll. Stu. Archaeo (Kao Gu Xue Yan Jiu) 10, 603–610. (in Chinese).

Li, Y. (2019). Preliminary Research on the Southward Boundary of Haochuan Culture and Interactions Among Jiangxi, Guandong and Fujian in Late Neolithic Period. J. Hunan Archaeo. (Hunan Kaogu Jikan) 13, 248–264. (in Chinese).

Li, Y., and Zhang, Q. (2021). The Civilization Process of Lingnan from the Perspective of Archaeology for a Century. J. Archaeo. Museo (Wenbo Xuekan) 2, 4–16. (in Chinese).

Lu, H., Liu, Z., Wu, N., Berné, S., Saito, Y., Liu, B., et al. (2002). Rice Domestication and Climatic Change: Phytolith Evidence from East China. Boreas 31 (4), 378–385. doi:10.1080/030094802320942581

Lu, T. L. D., Zhao, Z., and Zheng, Z. (2005). “The Prehistoric and Historic Environments: Vegetations and Subsistence Strategies at Sha Ha, Sai Kung,” in The Ancient Culture of Hong Kong-archaeological Discoveries in Sha Ha, Sai Kung. Editor Antiquities and Monuments Office of the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (Hongkong: Antiquities and Monuments Office of the Leisure and Cultural Services Department), 57-64.

Luo, W., Gu, C., Yang, Y., Zhang, D., Liang, Z., Li, J., et al. (2019). Phytoliths Reveal the Earliest Interplay of rice and Broomcorn Millet at the Site of Shuangdun (ca. 7.3-6.8 Ka BP) in the Middle Huai River valley, China. J. Archaeological Sci. 102, 26–34. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2018.12.004

Matsumura, H., Hung, H. C., Higham, C., Zhang, C., Yamagata, M., Nguyen, L. C., et al. (2019). Craniometrics Reveal “Two Layers” of Prehistoric Human Dispersal in Eastern Eurasia. Sci. Rep. 9: 1451. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-35426-z

Nasu, H., Gu, H., Momohara, A., and Yasuda, Y. (2012). Land-use Change for rice and Foxtail Millet Cultivation in the Chengtoushan Site, central China, Reconstructed from weed Seed Assemblages. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 4 (1), 1–14. doi:10.1007/s12520-011-0077-9

Nasu, H., Momohara, A., Yasuda, Y., and He, J. (2007). The Occurrence and Identification of Setaria Italica (L.) P. Beauv. (Foxtail Millet) Grains from the Chengtoushan Site (ca. 5800 Cal B.P.) in central China, with Reference to the Domestication centre in Asia. Veget Hist. Archaeobot 16 (6), 481–494. doi:10.1007/s00334-006-0068-4

Olsson, O., and Paik, C. (2016). Long-run Cultural Divergence: Evidence from the Neolithic Revolution. J. Dev. Econ. 122, 197–213. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.05.003

Reimer, P. J., Austin, W. E. N., Bard, E., Bayliss, A., Blackwell, P. G., Bronk Ramsey, C., et al. (2020). The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere Radiocarbon Age Calibration Curve (0-55 Cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62 (4), 725–757. doi:10.1017/rdc.2020.41

Relics from the South (2007). New Archaeoloical Discoveries from the South in 2006. Cul. Relics Southern Chin. (Nan Fang Wen Wu) 4, 19-87. (in Chinese).

Shenzhen Municipal Institute of Archaeology and Museology (2013). Excavation Report of the Xiantouling Site in Shenzhen. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press.

Stephens, L., Fuller, D., Boivin, N., Rick, T., Gauthier, N., Kay, A., et al. (2019). Archaeological Assessment Reveals Earth's Early Transformation through Land Use. Science 365 (6456), 897–902. doi:10.1126/science.aax1192

Tang, C. (2003). Archaeological Study on Tapa Beaters Unearthed from East Asia. Editor C.H. Tsang. in Prehistory and Classical Civilization. (Taipei: Academia Sinica), 77–123.

Tang, C., Zhang, Q., and Deng, X. (2019). Preliminary Study on the Southward Boundary of Jade Artefacts of Liangzhu Style. Cul. Relics Southern Chin. (Nan Fang Wen Wu) 2, 26–37. (in Chinese).

Tsang, C.-H., Li, K.-T., Hsu, T.-F., Tsai, Y.-C., Fang, P.-H., and Hsing, Y.-I. C. (2017). Broomcorn and Foxtail Millet Were Cultivated in Taiwan about 5000 Years Ago. Bot. Stud. 58 (1), 3. doi:10.1186/s40529-016-0158-2

Tsang, C.-H. (2005). “Recent discoveries at the Tapenkeng culture sites in Taiwan: implications for the problem of Austronesian origins”, in The peopling of East Asia: putting together archaeology, linguistics and genetics. Editor R. Blench, L. Sagart, and A. Sanchez-Mazas, (New York: Routledge), 63-74.

Wang, C. C., Yeh, H. Y., Popov, A. N., Zhang, H. Q., Matsumura, H., Sirak, K., et al. (2021). Genomic Insights into the Formation of Human Populations in East Asia. Nature 591, 413–419. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03336-2

Wang, C., Lu, H., Gu, W., Zuo, X., Zhang, J., Liu, Y., et al. (2018). Temporal Changes of Mixed Millet and rice Agriculture in Neolithic-Bronze Age Central Plain, China: Archaeobotanical Evidence from the Zhuzhai Site. The Holocene 28 (5), 738–754. doi:10.1177/0959683617744269

Wang, Y., and Lu, H. (1992). The Study of Phytolith and its Application. Beijing: China Ocean Press.

Wang, Z. (1990). Farmland Weeds in China: A Collection of Coloured Illustrative Plates. Beijing: Agricultural Publishing House.

Weber, S., Lehman, H., Barela, T., Hawks, S., and Harriman, D. (2010). Rice or Millets: Early Farming Strategies in Prehistoric central Thailand. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2 (2), 79–88. doi:10.1007/s12520-010-0030-3

Xia, X., Zhang, P., and Wu, Y. (2019). The Analysis of rice Remains from the Chaling Site in the Pearl River Delta, Guangdong Province. Quat. Sci. 39 (1), 24–36. (in Chinese).

Xiang, A., and Yao, J. (2006). Cultivated rice in Xinghuahe. Agri. Archaeo. (Nongye Kaogu) 1, 33–45. (in Chinese).

Xiang, J. (2014). Differences between the North and the South of the Origin of Grinding Stone in China. Cul. Relics Southern Chin. (Nan Fang Wen Wu) 2, 101–109. (in Chinese).

Yang, M. A., Fan, X., Sun, B., Chen, C., Lang, J., Ko, Y.-C., et al. (2020). Ancient DNA Indicates Human Population Shifts and Admixture in Northern and Southern China. Science 369 (6501), 282–288. doi:10.1126/science.aba0909

Yang, S., Qiu, L., Feng, M., and Xiang, A. (2015). Pre-Qin Archaeology of Guangdong. Guangzhou: Guangdong People's Publishing House.

Yang, X., Barton, H. J., Wan, Z., Li, Q., Ma, Z., Li, M., et al. (2013). Sago-type Palms Were an Important Plant Food Prior to rice in Southern Subtropical China. PloS one 8 (5), e63148. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063148

Yang, X., Chen, Q., Ma, Y., Li, Z., Hung, H.-C., Zhang, Q., et al. (2018). New Radiocarbon and Archaeobotanical Evidence Reveal the Timing and Route of Southward Dispersal of rice Farming in south China. Sci. Bull. 63 (22), 1495–1501. doi:10.1016/j.scib.2018.10.011

Yang, X., Wang, W., Zhuang, Y., Li, Z., Ma, Z., Ma, Y., et al. (2017). New Radiocarbon Evidence on Early rice Consumption and Farming in South China. Holocene. 27 (7), 1045-1051. doi.10.1177/0959683616678465

Yu, C. (2018). Preliminary Research of Subsistence Patterns from Neolithic to Bronze Age in Lingnan and Surrounding Area, China. Cul. Relics Southern Chin. (Nan Fang Wen Wu) 2, 180–187. (in Chinese).

Zhang, C., and Hung, H.C. (2012). Later hunter-gatherers in Southern China, 18 000-3000 BC. Antiquity 86 (331), 11–29. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00062438

Zhang, C., and Hung, H.C. (2010). The Emergence of Agriculture in Southern China. Antiquity 84 (323), 11–25. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00099737

Zhang, C. (2002). The Discovery of Early Pottery in China. Doc. Praehist 29, 29–35. doi:10.4312/dp.29.3

Zhang, J., Lu, H., Gu, W., Wu, N., Zhou, K., Hu, Y., et al. (2012). Early Mixed Farming of Millet and rice 7800 Years Ago in the Middle Yellow River Region, China. PLoS One 7 (12), e52146. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052146

Zhang, W., and Pei, A. (1997). Research on Rice Remains from the Bashidang Site of Li County. Cult. Relics (Wenwu) 1, 36–41. (in Chinese).

Zhang, W., Xiang, A., Qiu, L., and Xiao, D. (2007). Research on the Husks of Ancient rice in the Shixia Ruins. J. South. China Agric. 28, 20–23. (in Chinese).

Keywords: rice, foxtail millet, agriculture dispersal, southern China, mainland southeast Asia

Citation: Deng Z, Huang B, Zhang Q and Zhang M (2022) First Farmers in the South China Coast: New Evidence From the Gancaoling Site of Guangdong Province. Front. Earth Sci. 10:858492. doi: 10.3389/feart.2022.858492

Received: 20 January 2022; Accepted: 17 February 2022;

Published: 07 March 2022.

Edited by:

Ying Guan, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Jianping Zhang, Institute of Geology and Geophysics (CAS), ChinaChuan-Chao Wang, Xiamen University, China

Copyright © 2022 Deng, Huang, Zhang and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhenhua Deng, emhlbmh1YWRlbmdAcGt1LmVkdS5jbg==

Zhenhua Deng

Zhenhua Deng Bixiong Huang

Bixiong Huang Qianglu Zhang

Qianglu Zhang Min Zhang

Min Zhang