94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Earth Sci., 25 January 2023

Sec. Economic Geology

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.1098035

This article is part of the Research TopicExploration, Exploitation, and Utilization of Coal-Measure Gas into the Future: Volume IIView all 17 articles

Injecting CO2 into shale reservoirs has dual benefits for enhancing gas recovery and CO2 geological sequestration, which is of great significance to ensuring energy security and achieving the “Carbon Neutrality” for China. The CO2 adsorption behavior in shales largely determined the geological sequestration potential but remained uncharted. In this study, the combination of isothermal adsorption measurement and basic petro-physical characterization methods were performed to investigate CO2 adsorption mechanism in shales. Results show that the CO2 sorption capacity increase gradually with injection pressure before reaching an asymptotic maximum magnitude, which can be described equally well by the Langmuir model. TOC content is the most significant control factor on CO2 sorption capacity, and the other secondary factors include vitrinite reflectance, clay content, and brittle mineral content. The pore structure parameter of BET-specific surface area is a more direct factor affecting CO2 adsorption of shale than BJH pore volume. Langmuir CO2 adsorption capacity positive correlated with the surface fractal dimension (D1), but a significant correlation is not found with pore structure fractal dimension (D2). By introducing the Carbon Sequestration Leaders Forum and Department of Energy methods, the research results presented in this study can be extended to the future application for CO2 geological storage potential evaluation in shales.

Shale gas plays a crucial role in natural gas production in China because its great potential (recoverable reserves of ∼3.12 × 1013 m3) (Liu et al., 2019a; Li et al., 2019; Yao et al., 2019). The exploration and development of shale gas is the choice of fossil energy resource and national needs, which is of great significance to China’s energy security (Xie et al., 2022). The methane content of shales is generally greater than 85%, even up to 99% (Howarth et al., 2011). The methane exists in shales in three strikingly different phases (Hazra et al., 2015; Zou et al., 2018; Yao et al., 2021): 1) Dissolving in the shale pore water as dissolved phase, which can be almost negligible. 2) Presenting in the form of movable fluid in shale pore-fracture system, defined as free phase methane. 3) Existing on the inner shale pore surface or in the shale matrix as an adsorbed state, defined as adsorbed phase methane.

The extremely low porosity and permeability of shale or coal reservoirs have significantly increased the difficulty of gas development (Zheng et al., 2018, 2019), and the initial fracturing engineering must be done to commercialize shale gas production (Liu et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2018; Dai et al., 2019). Currently, the hydraulic fracturing technology is a standard option for shale gas production (Gregory et al., 2011; Estrada and Bhamidimarri, 2016), but the high clay minerals content leads to poor stimulation–due to the expansion characteristics of shale clay minerals in contact with water (Ge et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2022). In addition, additives in fracturing fluid can also pose a risk of environmental pollution (Vidic et al., 2013). CCUS (carbon capture, utilization, and storage) refers to the process of separating CO2 from industrial processes or the atmosphere and then directly utilizing or injecting it into the stratum to achieve permanent CO2 emission reduction (Liu et al., 2019b; Zheng et al., 2022). Injecting CO2 into shales for enhancing shale gas recovery (abbreviated as CO2-ESGR) has another unexpected benefits for CO2 geological storage (Liu et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2020). First, the CO2 fracturing technology can reduce shale reservoir damage by comparing it with the fracturing fluid of water. In addition, the essence of CO2-ESGR is the transformation of adsorbed methane to free phased–due to the CO2-CH4 competitive adsorption characterizations in shales. The characteristic of CO2 adsorption in shales are essential for the CO2-ESGR field application results and CO2 geological storage safety.

Isothermal adsorption measurement is the most commonly used method for providing CO2 adsorption characteristics in shales (Wang et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2021; Liu D et al., 2022). The analysis models to study CO2 adsorption properties include the classical statistical mechanics-based Freundlich model, monolayer adsorption-based Langmuir model, multilayer adsorption BET model, and micro-pore filling adsorption D-R model (Du et al., 2021; Liu J et al., 2021; Shi et al., 2022). Weniger et al. (2010) estimated the CO2 sorption capacity in shale samples from the Paraná Basin under an experimental temperature of ∼35°C and ∼45°C. They found CO2 adsorption amount reached the maximum in the pressure range of 8.0–10.0 MPa. Kang et al. (2011) investigated the CO2 storage potential in organic-rich-shales by performing CO2 isothermal adsorption experiments. Experimental results in their study (Kang et al., 2011) indicated that pore-volume evaluation plays an essential role in shale reservoir CO2 geological storage. By introducing the Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulation methods, CO2 adsorption properties at modeled quartz were well described by the Langmuir model (Sun et al., 2016). In summary, the contribution of shale internal compositions together with pore structures on its CO2 adsorption characteristics still remains unclassified due to the complex multi-factor coupling factor.

In this paper, we first performed the sulfur-carbon test, organic matter measurement, and XRD measurement to investigate the shale’s organic geochemical and mineralogical characteristics. Based on the combination of pore structure characterization method and single fractal theory, the heterogeneous features of shales are systematically estimated. The CO2 adsorption characteristics in shale gas reservoirs are evaluated through isothermal adsorption experiments, and the control mechanisms and patterns are established to reveal CO2 adsorption characteristics in shale gas reservoirs directly. The research results presented in this paper have great significance in estimating CO2 sequestration storage potential in shales.

In this study, six shales were obtained from the Longmaxi formation, Sichuan Basin. The shales of S1, S3, S5, and S6 were collected from the bottom to upper-middle Longmaxi formation at the Chongqing Blackwater Section (Figure 1). In comparison, the S2 and S4 were gathered from the bottom Longmaxi formation located at Qiliao and Pengshui Sections, respectively (Figure 1). The detailed petro-physical, organic geochemical, and mineralogical information parameters are presented in Table 1. The TOC of the selected shales in the range of 1.44%–4.97%, estimated by the CS-800 Carbon sulfur analyzer. The Ro (vitrinite reflectance equivalent) of the selected shales averaged at ∼2.41%, classifying to the over-mature stage. The XRD experimental results are listed in Table 1 and shown in Figure 2. Results indicated that the quartz content contributes the most significant mineral proportion of shales, ranging from 48.77% to 54.04%. The SEM results are displayed in Figure 3, the shale pore types include dissolved pore (Figure 3B), intergranular pore (Figures 3C,D), organic pore (Figure 3F), and microfracture (Figures 3A,E).

In this study, the low-temperature N2 gas adsorption (LT-N2GA) measurements were performed to investigate the pore structure properties of shales, following the Chinese standard of SY/T6154-1995. For the sample preparation, the large-sized shales were crushed to 60–80 mesh, then dried in an oven to remove impurity gas and internal bound-water. The LT-N2GA procedures can be summarized as: 1) Subject a certain amount of powder shales to vacuum degassing. 2) Obtaining the N2 adsorption/desorption properties under constant experimental conditions. 3) Estimating the pore structure parameters (e.g., specific surface area, pore volume). based on the BJH and BET models (Yao et al., 2008).

CO2 adsorption isotherm measurements were performed by the volumetric-based method (Figure 4). The principle of this method depends on the pressure changes in the sample and reference cells during CO2 adsorption process. CO2 adsorption isotherm experimental procedures were summarized as: 1) Grind the bulk shale into 60–80 mesh (0.02–0.03 cm) using a ball-mill instrument and then represent dry treatment for 72-h at a given temperature of 110°C to remove the moisture inside the sample. 2) Transfer the powder sample in to sample cell and then present vacuum treatment by a vacuum pump. 3) Calculate the free space volume based on the mass balance parameters before/after helium injection. 3) Inject the designed pressure of CO2 into the sample cell for CO2 adsorption. e) Estimate the CO2 adsorption capacity on the basis of the ideal-gas equation.

Table 2 shows the pore structure parameters of the selected shales identified by the LT-N2GA measurement. Results indicated that the BJH pore volume of shales range from 0.0117 to 0.0163 cm3/g, the volume of micropores (pore radius <2 nm), mesopores (pore radius 2–50 nm), and macropores (pore radius >50 nm) contribute the total proportion as ∼41.75%, ∼41.05%, and ∼17.2%, respectively. While the BET specific surface area in the range of 7.94–66.02 m2/g, the specific surface area of micropores, mesopores and macropores contribute the total proportion as ∼75.75%, ∼23.75%, and ∼0.5%. The low percentage of macropores in BET specific surface area is mainly because the LT-N2GA testing principle–limiting characterizes the pore size larger than 200 nm. As shown in Figure 5, the pore size distributions (PSD) of some shales (S6 and S5) emerge two significantly different peaks; from left to right, the peak locates at 2–3 and 10–20 nm, respectively. For the remaining shale samples, the PSD is characterized by a unimodal size distribution with a peak at approximately 8–20 nm.

Based on the LT-N2GA experimental data and Frenkel-Halsey-Hil (FHH) model, the complexity and heterogeneity of shale were quantitatively characterized (He et al., 2021; Liu K et al., 2021). The greater fractal dimension is indicative of more heterogeneity pore structure. FHH fractal dimension calculation method was expressed as follows:

where V means the nitrogen adsorption volume under pressure P, mmol/g; P means the experimental equilibrium pressure, MPa; V0 means the monolayer coverage volume, mmol/g; K and C are constant, dimensionless; P0 is the nitrogen saturation pressure, MPa. According to Eq. 1, the slope of lnV vs. ln (ln (P0/P)) plots equals the constant C. While the fractal dimension D equals “C+3” value. Theoretically, fractal dimension D in the range of 2–3, the closest value to two indicates the more regular the pore space structures, and the closest value to three means the more complex and heterogeneity pore structures.

The scatterplot of lnV vs. ln (ln (P0/P)) for six shales are displayed in Figure 6. It can be found that there are two distinct linear segments, one at the P/P0 intervals of 0–0.5 and the other one at the 0.5–1 region. In addition, these two linear segments show great linear relationships (R2>0.95), indicating the different fractal characteristics. Here, the fractal dimension at P/P0 intervals 0–0.5 and 0.5–1 as D1 and D2, respectively. Moreover, D1 and D2 represent the pore surface fractal and the pore structure fractal, dominated by Van der Waals forces and capillary condensation actions, respectively (Yao et al., 2008). As shown in Table 3, The fractal dimension D1 of shales value as ∼2.29–2.75, average at 2.51. While the fractal dimension D2 ranges from 2.56 to 2.89, average at 2.70 (Table 3).

Figure 7 represents the CO2 isothermal adsorption data with respect to different pressures for the selected shales. The excess CO2 adsorption capacity rapidly increases with pressure at low-pressure intervals, and slowly increases at high-pressure intervals. Additionally, the CO2 adsorption capacities vary from region to region. The experimental determined maximum excess CO2 adsorption capacity of shale S1 is ∼2.02 cm3/g, the smallest value among all the samples (Figure 7). In comparison, the experimental determined maximum excess CO2 adsorption capacity of S6 is valued as ∼5.41 cm3/g (Figure 7). These differences probably arise because of the complex solid and heterogeneity in shales–resulting in the variation in internal composition and pore structure–leading to the different CO2 adsorption capacities in different shales.

Langmuir model is the commonly used adsorption characterization model in coals, which can be extended to investigate the CO2 adsorption capacity for shales. The Langmuir model was based on the following assumptions (Perera et al., 2011; Dutka, 2019; Liu Y et al., 2022): 1) The adsorbent surface was characterized as uniform; 2) A dynamic adsorption equilibrium state between adsorbent and adsorbate; 3) The adsorption behavior was monolayer molecular adsorption; 4) No interaction force among the adsorbent gas molecules. The Langmuir model can be deduced as follows:

where V means the experimental measured adsorption capacity, cm3/g; P means the experimental pressure, MPa. VL means the Langmuir adsorption capacity, cm3/g; PL means Langmuir adsorption pressure, MPa.

The CO2 isothermal adsorption data fitting results are listed as Table 3, and the fitting curves are displayed in Figure 7. Results indicate that the Langmuir model fitting curves are consistent with experimental excess CO2 adsorption capacity changes. The CO2 adsorption capacity rapidly increases with increasing pressure before reaches to a critical pressure; after that, the fitting curves rise smoothly and tend to saturate. As shown in Table 3, the Langmuir volumes of the CO2 isothermal adsorption in the shale in the range of 3.26–6.95 cm3/g (averaging ∼5.03 cm3/g). While, the Langmuir pressure of the CO2 isothermal adsorption in the shale ranges from 0.99 MPa to 3.05 MPa (averaging ∼1.76 MPa). It can be concluded that the Langmuir model is used equally well to investigate the CO2 sorption behavior for shales, as evident by the high correlation coefficients >0.9875.

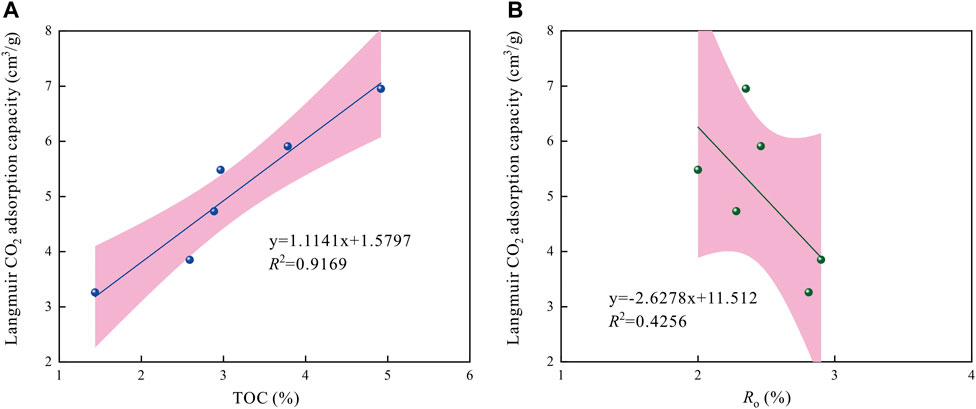

Figure 8 shows the relationships between TOC content, Ro value and Langmuir CO2 adsorption capacity. Results indicate a perfect positive linear correlation between TOC content and Langmuir CO2 adsorption capacity, with a high correlation coefficient as ∼0.9169 (Figure 8A). The higher TOC content is indicative of greater CO2 adsorption capacity. The above phenomenon can be attributed to the massive nanopore kerogen development in organic matter, which is the leading adsorption site of CO2 in shales. In addition, the Ro presents a very weak negative correlation with the Langmuir CO2 adsorption capacity (Figure 8B). Tang et al. (2016) investigated the adsorption behavior of the shales under the same conditions for organic matter and kerogen shale types, and found the adsorption capacities of over-mature shales were lower than these in high-maturity stages. The results presented in this section are consistent with the previous study (e.g., Chalmers and Bustin, 2008; Tang et al., 2016).

FIGURE 8. Relationships between TOC content, Ro value and Langmuir CO2 adsorption capacity in shales.

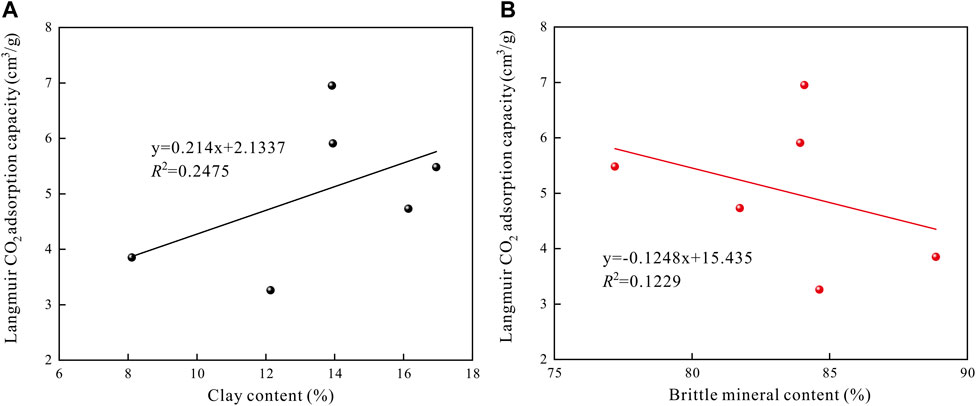

The effect of shale mineral composition on its CO2 adsorption capacity is mainly reflected in the clay and brittle minerals. In this study, the relationships between clay content, brittle mineral content and Langmuir CO2 adsorption capacity in shales are displayed in Figure 9. It can be found that there exists a positive correlation between the clay content and Langmuir CO2 adsorption capacity (Figure 9A). While, the brittle mineral content was negative related with the Langmuir CO2 adsorption capacity (Figure 9B), properly because the increase in brittle mineral content in the shale leads to relative decreases both in the clay and TOC content. The correlation coefficient of clay content and Langmuir CO2 adsorption capacity was more significant than that with brittle mineral content, indicating clay content is the significant control factor on CO2 adsorption.

FIGURE 9. The relationships between clay content, brittle mineral content and Langmuir CO2 adsorption capacity in shales.

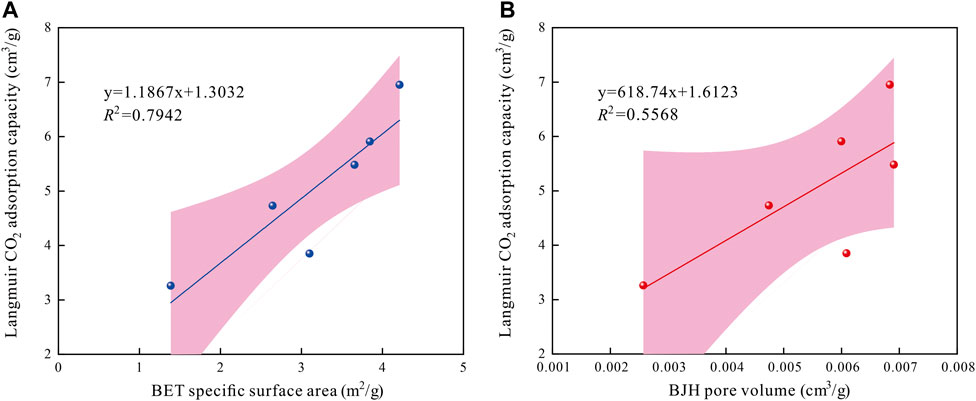

Figure 10 presents the correlations between pore structure parameters (obtained from the LT-N2GA measurements) and CO2 adsorption capacity of shales. Results illustrate that both the specific surface area and pore volume positively affect the CO2 adsorption capacity. The correlation coefficient of CO2 adsorption capacity and specific surface area was greater than that with pore volume, indicating that the specific surface area is the most direct factor affecting the CO2 adsorption of shale. The behavior of CO2 adsorbing in shale pore surface is attributed to the physical adsorption of Vander Waals force. The larger specific surface area is indicative of more adsorption sites–more conducive to the CO2 adsorption in shales.

FIGURE 10. Relationships between pore structure parameters vs. Langmuir CO2 adsorption capacity in shales.

The shale pore structures were characterized by heterogeneity (as discussed in Section 3.1), and the influence of these fractal characteristics on CO2 adsorption behavior cannot be ignored. Generally, there are two conventional definitions for describing fractal characteristics of porous materials: the surface fractal dimension (D1) and the pore structure fractal dimension (D2). Thus, it is necessary to quantitatively investigate the effect of pore fractal characteristics on the adsorption and storage capacity. As shown in Figure 11, the two fractal dimensions have different influences on the CO2 adsorption capacity of shales. Results show that the fractal dimension D1 positively correlated with the Langmuir CO2 adsorption capacity (Figure 11A). Because the higher fractal dimension D1 values represent more rough surfaces of shales that offer more adsorption sites for CO2 and lead to the higher adsorption capacity of shales. Additionally, there were no significant relationships between the fractal dimension D2 and Langmuir CO2 adsorption capacity (Figure 11B).

Shale reservoirs have considerable potential for large-scale CO2 sequestration, and the sequestration mechanisms are mainly controlled by adsorption and mineralization reactions. CO2-ESGR technology opens up a new way for the green and efficient development of domestic unconventional oil and gas and geothermal resources. It is conducive to realizing the strategic goal of “Carbon Peak” in 2030 and “Carbon Neutrality” in 2060 in China. In 2020, the shale gas proved geological reserves reached ∼2 × 1012 m3, providing a good application prospect in CO2 geological storage. There are two classic methods to estimate the CO2 geological storage potential in shales; one is the CSLF (Carbon Sequestration Leaders Forum) method (as described in Eq. 3), and the other one is the DOE (United States Department of Energy) method (as described in Eq. 4).

where MCO2 is the CO2 geological storage volume in shales, m3; ρg is the density of CO2, kg/m3; PPGI is the available shale gas production, kg; Re is replacement volume ration between CO2 and CH4, dimensionless.

where MCO2 is the CO2 geological storage volume in shales, m3; Ashale is the target shale gas reservoir area, m2; ρg is the density of CO2, kg/m3; h is the thickness of target shale gas reservoir, m; Va is the CO2 adsorption capacity, m3/kg; Vf is the free phase CO2 content, m3/kg; E is the effective factor of shale CO2 geological storage, which is influenced by the CO2 adsorption capacity, buoyancy characteristics, and transport capacity. Based on the combination of CO2 adsorption capacity and above parameters in Eq. 3 or Eq. 4, it is straightforward to calculate the CO2 geological storage potential in shales.

In this study, the combination of isotherm adsorption measurement and basic petro-physical characterization methods were performed on six Longmaxi shales to investigate CO2 adsorption behavior and mechanism. The main conclusions are as follows.

(1) The fractal characteristics of shale pore structure were systematically analyzed by the FHH fractal model based on the LT-N2GA experimental data. Two distinct linear segments at the P/P0 intervals of 0–0.5 and 0.5–1 region correspond to the pore surface fractal (D1) and the pore structure fractal (D2) properties, respectively. The fractal dimensions D1 and D2 of shales are in the range of 2.29–2.75 and 2.56–2.89, indicating the complexity and heterogeneity of shale pore structures.

(2) The CO2 excess adsorption capacities increase gradually with increasing injection pressure before reaching an asymptotic maximum magnitude, which can be described equally well by the Langmuir model as evidenced by the high correlation coefficients.

(3) TOC content is the most significant control factor on shale CO2 sorption capacity, and a positive correlation exists between the surface fractal dimension D1 and Langmuir CO2 adsorption capacity. By calculating the selective adsorption coefficient of CO2/CH4, the research results presented in this study can be extended to the prospective application of shale CO2 geological storage potential evaluation.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

SS and MW provided the funding acquisition; SZ performed the experiments and wrote the paper; KH analyzed the data; GF and YS provided technical support.

We acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42141012; 42030810; 41972168), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation funded project (2022M723385), the Major research project of Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Coal-based Greenhouse Gas Control and Utilization (2020ZDZZ01B), the Peng Cheng Shang Xue Education Fund of CUMT Education Development Foundation (PCSX202204), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2022QN1046).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Chalmers, G. R., and Bustin, R. M. (2008). Lower cretaceous gas shales in northeastern British columbia, Part I: Geological controls on methane sorption capacity. Bull. Can. Petroleum Geol. 56, 1–21. doi:10.2113/gscpgbull.56.1.1

Chen, L., Jiang, Z. X., Shu, J., Guo, S., and Tan, J. Q. (2021). Effect of pre-adsorbed water on methane adsorption capacity in shale-gas systems. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 757705. doi:10.3389/feart.2021.757705

Dai, C., Liu, H., Wang, Y. Y., Li, X., and Wang, W. H. (2019). A simulation approach for shale gas development in China with embedded discrete fracture modeling. Mar. Pet. Geol. 100, 519–529. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.09.028

Du, X. D., Cheng, Y. G., Liu, Z. J., Yin, H., We, T. F., Huo, L., et al. (2021). CO2 and CH4 adsorption on different rank coals: A thermodynamics study of surface potential, gibbs free energy change and entropy loss. Fuel 283, 118886. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118886

Dutka, B. (2019). CO2 and CH4 sorption properties of granular coal briquettes under in situ states. Fuel 247, 228–236. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2019.03.037

Estrada, J. M., and Bhamidimarri, R. (2016). A review of the issues and treatment options for wastewater from shale gas extraction by hydraulic fracturing. Fuel 182, 292–303. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2016.05.051

Ge, H. K., Yang, L., Shen, Y. H., Ren, K., Meng, F. B., Li, W. M., et al. (2015). Experimental investigation of shale imbibition capacity and the factors influencing loss of hydraulic fracturing fluids. Pet. Sci. 12, 636–650. doi:10.1007/s12182-015-0049-2

Gregory, K. B., Vidic, R. D., and Dzombak, D. A. (2011). Water management challenges associated with the production of shale gas by hydraulic fracturing. Elements 7, 181–186. doi:10.2113/gselements.7.3.181

Hazra, B., Varma, A. K., Bandopadhyay, A. K., Mendhe, V. A., Singh, B. D., Saxena, V. K., et al. (2015). Petrographic insights of organic matter conversion of Raniganj basin shales, India. Int. J. Coal Geol. 150–151, 193–209. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2015.09.001

He, H. F., Liu, P. C., Xu, L., Hao, S. Y., Qiu, X. Y., Shan, C., et al. (2021). Pore structure representations based on nitrogen adsorption experiments and an FHH fractal model: Case study of the block Z shales in the Ordos Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 203, 108661. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2021.108661

Howarth, R. W., Santoro, R., and Ingraffea, A. (2011). Methane and the greenhouse-gas footprint of natural gas from shale formations. Clim. Change 106, 679–690. doi:10.1007/s10584-011-0061-5

Kang, S. M., Fathi, E., Ambrose, R. J., Akkutlu, I. Y., and Sigal, R. F. (2011). Carbon dioxide storage capacity of organic-rich shales. SPE J. 16 (04), 842–855. doi:10.2118/134583-pa

Li, J. Q., Wang, S. Y., Lu, S. F., Zhang, P. F., Cai, J. C., Zhao, J. H., et al. (2019). Microdistribution and mobility of water in gas shale: A theoretical and experimental study. Mar. Pet. Geol. 102, 496–507. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.01.012

Liu, D. M., Yao, Y. B., and Chang, Y. H. (2022). Measurement of adsorption phase densities with respect to different pressure: Potential application for determination of free and adsorbed methane in coalbed methane reservoir. Chem. Eng. J. 446, 137103. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2022.137103

Liu, J., Xie, L. Z., Elsworth, D., and Gan, Q. (2019b). CO2/CH4 competitive adsorption in shale: Implications for enhancement in gas production and reduction in carbon emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53 (15), 9328–9336. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b02432

Liu, J., Xie, L. Z., He, B., Gan, Q., and Zhao, P. (2021). Influence of anisotropic and heterogeneous permeability coupled with in-situ stress on CO2 sequestration with simultaneous enhanced gas recovery in shale: Quantitative modeling and case study. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 104, 103208. doi:10.1016/j.ijggc.2020.103208

Liu, J., Xie, L. Z., Yao, Y. B., Gan, Q., Zhao, P., and Du, L. H. (2019a). Preliminary study of influence factors and estimation model of the enhanced gas recovery stimulated by carbon dioxide utilization in shale. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 20114–20125. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b06005

Liu, J., Yao, Y. B., Liu, D. M., and Elsworth, D. (2017). Experimental evaluation of CO2 enhanced recovery of adsorbed-gas from shale. Int. J. Coal Geol. 179, 211–218. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2017.06.006

Liu, K. Q., Ostadhassan, M., Jiang, H. W., Zakharova, N. V., and Shokouhimehr, M. (2021). Comparison of fractal dimensions from nitrogen adsorption data in shale via different models. RSC Adv. 11, 2298–2306. doi:10.1039/d0ra09052b

Liu, P. L., Feng, Y. S., Zhao, L. Q., Li, N. Y., and Luo, Z. F. (2015). Technical status and challenges of shale gas development in Sichuan Basin, China. Petroleum 1, 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.petlm.2015.03.001

Liu, Y., Cao, Q., Ye, X., and Dong, L. (2022). Adsorption characteristics and pore structure of organic-rich shale with different moisture contents. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 863691. doi:10.3389/feart.2022.863691

Ma, Y. S., Cai, X. Y., and Zhao, P. R. (2018). China’s shale gas exploration and development: Understanding and practice. Petroleum Explor. Dev. 45, 589–603. doi:10.1016/s1876-3804(18)30065-x

Perera, M. S. A., Ranjith, P. G., Choi, S. K., and Airey, D. (2011). The effects of sub-critical and super-critical carbon dioxide adsorption-induced coal matrix swelling on the permeability of naturally fractured black coal. Energy 36, 6442–6450. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2011.09.023

Shi, Q. M., Cui, S. D., Wang, S. M., Mi, Y. C., Sun, Q., Wang, S. Q., et al. (2022). Experiment study on CO2 adsorption performance of thermal treated coal: Inspiration for CO2 storage after underground coal thermal treatment. Energy 254, 124392. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.124392

Sun, H. Y., Sun, W. C., Zhao, H., Sun, Y. G., Zhang, D. R., Qi, X. Q., et al. (2016). Adsorption properties of CH4 and CO2 in quartz nanopores studied by molecular simulation. RSC Adv. 6, 32770–32778. doi:10.1039/c6ra05083b

Tang, X. L., Jiang, Z. X., Jiang, S., Wang, P. F., and Xiang, C. F. (2016). Effect of organic matter and maturity on pore size distribution and gas storage capacity in high-mature to post-mature shales. Energy fuels. 30, 8985–8996. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.6b01499

Vidic, R. D., Brantley, S. L., Vandenbossche, J. M., Yoxtheimer, D., and Abad, J. D. (2013). Impact of shale gas development on regional water quality. Science 340, 1235009. doi:10.1126/science.1235009

Wang, Y., Zhu, Y. M., Liu, S. M., and Zhang, R. (2016). Pore characterization and its impact on methane adsorption capacity for organic-rich marine shales. Fuel 181, 227–237. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2016.04.082

Weniger, P., Kalkreuth, W., Busch, A., and Krooss, B. M. (2010). High-pressure methane and carbon dioxide sorption on coal and shale samples from the Paraná Basin, Brazil. Int. J. Coal Geol. 84, 190–205. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2010.08.003

Xie, W. D., Wang, M., Vandeginste, V., Chen, S., Yu, Z. H., Wang, J. Y., et al. (2022). Adsorption behavior and mechanism of CO2 in the Longmaxi shale gas reservoir. RSC Adv. 12, 25947–25954. doi:10.1039/d2ra03632k

Yang, S., Li, Y. L., Zhu, Y., and Liu, D. Q. (2018). Effect of fracture on gas migration, leakage and CO2 enhanced shale gas recovery in Ordos Basin. Energy Procedia 154, 139–144. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2018.11.023

Yao, Y. B., Liu, D. M., Tang, D. Z., Tang, S. H., and Huang, W. H. (2008). Fractal characterization of adsorption-pores of coals from North China: An investigation on CH4 adsorption capacity of coals. Int. J. Coal Geol. 7, 27–42. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2007.07.003

Yao, Y. B., Liu, J., Liu, D. M., Chen, J. Y., and Pan, Z. J. (2019). A new application of NMR in characterization of multiphase methane and adsorption capacity of shale. Int. J. Coal Geol. 201, 76–85. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2018.11.018

Yao, Y. B., Sun, X. X., Zheng, S. J., Wu, H., Zhang, C., Liu, Y., et al. (2021). Methods for petrological and petrophysical characterization of gas shales. Energy fuels. 35, 11061–11088. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c01475

Zheng, S. J., Yao, Y. B., Elsworth, D., Liu, D. M., and Cai, Y. D. (2020). Dynamic fluid interactions during CO2-ECBM and CO2 sequestration in coal seams. Part 2: CO2-H2O wettability. Fuel 279, 118560. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118560

Zheng, S. J., Yao, Y. B., Liu, D. M., Cai, Y. D., and Liu, Y. (2018). Characterizations of full-scale pore size distribution, porosity and permeability of coals: A novel methodology by nuclear magnetic resonance and fractal analysis theory. Int. J. Coal Geol. 196, 148–158. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2018.07.008

Zheng, S. J., Yao, Y. B., Liu, D. M., Cai, Y. D., Liu, Y., and Li, X. W. (2019). Nuclear magnetic resonance T2 cutoffs of coals: A novel method by multifractal analysis theory. Fuel 241, 715–724. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2018.12.044

Zheng, S. J., Yao, Y. B., Sang, S. X., Liu, D. M., Wang, M., and Liu, S. Q. (2022). Dynamic characterization of multiphase methane during CO2-ECBM: An NMR relaxation method. Fuel 324, 124526. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2022.124526

Zhou, Y., You, L. J., Kang, Y. L., Jia, C. G., and Xiao, B. (2022). Influencing factors and application of spontaneous imbibition of fracturing fluids in lacustrine and marine shale gas reservoir. Energy fuels. 36, 3606–3618. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.2c00153

Keywords: shale gas, adsorption capacity, pore structure, mineral composition, CO2 geological storage

Citation: Zheng S, Sang S, Wang M, Liu S, Huang K, Feng G and Song Y (2023) Experimental investigations of CO2 adsorption behavior in shales: Implication for CO2 geological storage. Front. Earth Sci. 10:1098035. doi: 10.3389/feart.2022.1098035

Received: 14 November 2022; Accepted: 05 December 2022;

Published: 25 January 2023.

Edited by:

Junjian Zhang, Shandong University of Science and Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Kun Zhang, Henan Polytechnic University, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Zheng, Sang, Wang, Liu, Huang, Feng and Song. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuxun Sang, c2h4c2FuZ0BjdW10LmVkdS5jbg==; Meng Wang, d2FuZ21AY3VtdC5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.