- 1Institute of Cultural Heritage, Shandong University, Qingdao, China

- 2Université de Bordeaux, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique UMR5199 – PACEA, Pessac, France

The origin and development of bone technologies in China are reviewed in the light of recent discoveries and compared to trends emerging from the European and African archaeological records. Three categories of osseous tools are targeted: 1) unmodified bone fragments bearing traces of use in technological activities; 2) bone fragments modified to a variable extent with techniques generally used in stone technologies; 3) osseous fragments entirely shaped with techniques fit for the manufacture of formal bone tools. Early evidence of bone technologies in China are sporadically found in contexts dated between 1.8 and 1.0 Ma. By the late MIS6–early MIS5, bone tools are well-integrated in the technological systems of Pleistocene populations and the rules guiding their use appear increasingly standardized. In addition, the first evidence for the use of osseous material in symbolic activities emerges in the archaeological record during this period. Finally, between 40 and 35 ka, new manufacturing techniques and products are introduced in Late Palaeolithic technological systems. It is first apparent in the manufacture of personal ornaments, and followed by the production and diversification of formal bone tools. By that time, population dynamics seem to become materialized in these items of material culture. Despite regional specificities, the cultural trajectories identified for the evolution of bone technologies in China seem entirely comparable to those observed in other regions of the world.

1 Introduction

The evolution of bone technologies represents a key issue in paleoanthropological research. First, from a subsistence perspective, the origin of bone tools signals a major shift in the way past populations perceived the animal species at their disposal, specifically when faunal resources’ utility expanded from their primary uses, i.e., meat consumption, hide processing, fat use, and fuel, to include the manufacture and use of cultural items made of hard animal tissues. Second, from a social perspective, bone tools represent an ideal proxy to investigate social dynamics. Indeed, owing to their mechanical properties, prehistoric populations could impose a form to the object by applying a sequence of adapted techniques, e.g., scraping, incision, grinding, gouging, etc. When studying implements produced with these techniques, archaeologists can document variation in how knowledge was implemented for the manufacture of various tool types, differentiate between the form and function of an object, and explore topics such as technological organization, pattern of cultural transmission, population dynamics, etc.

Expanding on Klein (2009) definitions, it is possible to distinguish three main categories of bone tools. The first category includes unmodified osseous fragments bearing clear evidence of their use. The second comprises fragments intentionally modified albeit with techniques usually devoted to the manufacture of stone tools. The third refers to osseous fragments entirely shaped with techniques fit to transform hard animal tissues. The first two categories are usually referred to as “expedient tools” while the third is known as “formal tools” (Klein, 2009). Here, the aim is to provide a synthesis on the tipping points that punctuated the origin and development of these broad artefactual categories and compare recent evidence from China to the African and European archaeological record. This review highlights that, despite some regional specificities, the cultural trajectories identified for the evolution of bone technologies in China are largely comparable to those observed in other regions of the world.

2 Pleistocene Osseous Technology in Africa and Europe

Four tipping points can be identified in the origin and development of bone technologies in Africa and Europe. The first tipping point occurs between 2.0 and 1.5 Ma, a period at which the first occurrences of the use of bone appear simultaneously in the South and East African archaeological records. In South Africa, a number of sites attests to the use of mostly unmodified bone fragments as digging implements by Australopithecus robustus (Brain and Shipman, 1993; Backwell and d’Errico, 2001; Backwell and d’Errico, 2008; d’Errico and Backwell, 2003; Val and Stratford, 2015; Stammers et al., 2018; Hanon et al., 2021). Meanwhile, in East Africa, occupation layers at Olduvai Bed I and II yielded numerous bone fragments bearing evidence of intentional shaping. Technological and use-wear studies suggest that early members of our genus, Homo, used these implements for hide-working, butchery, digging, stone knapping and, possibly, hunting activities (Backwell and d’Errico, 2004; Pante et al., 2020). It remains unclear why organic technologies were integrated in the technological systems of our ancestors. However, it appears reasonable to believe that activities attested since at least 2.6 Ma, such as stone knapping (Harmand et al., 2015; Lewis and Harmand, 2016), marrow extraction (Domínguez-Rodrigo et al., 2005), and wood working (Lemorini et al., 2014, 2019), may have allowed early hominins to recognize the technological potential of osseous materials and equipped them with the skills required to modify and utilize bone flakes.

Between 1.5 Ma and the second half of the Middle Pleistocene, the archaeological record yielded only a handful of evidence for the use or modification of osseous remains for technological purpose. Most often, these items correspond to bone retourchers, i.e., bone fragments used in stone knapping activities (Goren-Inbar, 2011; Smith, 2013; Moigne et al., 2016), or bifaces made on Elephantidae long bone fragments (Kretzoi and Dobosi, 1990; Mania and Mania, 2003; Rabinovich et al., 2012; Sano et al., 2020). In rare occasion, hard animal remains bearing incised patterns (Mania and Mania, 1988; Sirakov et al., 2010; Joordens et al., 2015) are interpreted as early experimentations with this raw material either to permanently record information or to express some form of symbolic behaviors. Collectively, these occurrences, albeit scattered in both time and space, suggest that the use osseous materials for technological purposes was never completely abandoned by prehistoric populations during this period.

The second tipping point occurs mainly in Europe at the onset of the Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 9. Between ∼350 and 300 ka, bone bifaces and retouchers become commonplace (Naldini et al., 2009; Anzidei et al., 2012; Moncel et al., 2012; Blasco et al., 2013; Daujeard et al., 2014; Boschian and Saccà, 2015; Santucci et al., 2016; Villa et al., 2021). Furthermore, the archaeological record attests to a noticeable increase in the diversity of expedient bone tool morphology and of the use-wear development on them, possibly reflecting an expansion in the behavioral spectrum for which they were used (Rosell et al., 2011; Julien et al., 2015; Di Buduo et al., 2020; Bonhof and van Kolfschoten, 2021). From the MIS9 onward, the use of expedient tools becomes a lasting aspect of Pleistocene technological systems alongside the multiple innovations that define the third and fourth tipping points (e.g., Daujeard, 2007; Burke and d’Errico, 2008; Verna and d’Errico, 2011; Mallye et al., 2012; Tartar, 2012; Abrams et al., 2014; Daujeard et al., 2018; Yeshurun et al., 2018; Baumann et al., 2020; Hallett et al., 2021).

The third tipping point is restricted to the African continent. Between 90 and 65 ka, a number of formal bone tools appear in the archaeological record. The distribution of each type presents a marked pattern of regionalization with bone knives and smoothers found in Northeast Africa (Bouzouggar et al., 2018; Hallett et al., 2021), barbed points in Central Africa (Yellen, 1998), and awls, wedges and hunting implements in South Africa (Henshilwood et al., 2001; d’Errico and Henshilwood, 2007; d’Errico et al., 2012a; Bradfield et al., 2020). In Africa, the emergence of formal bone tools is broadly contemporaneous with the appearance of personal ornaments (d’Errico et al., 2005; d’Errico et al., 2008; d’Errico et al., 2009; Vanhaeren et al., 2006, 2019; Bouzouggar et al., 2007; Bar-Yosef Mayer et al., 2009; Val et al., 2020), although recent discoveries from Bizmoune Cave, Morocco, indicates personal ornaments may have been manufactured up to 50 millennia prior to the first bone tools in this particular region (Sehasseh et al., 2021). Interestingly, both personal ornaments and formal bone tools disappear from the African archaeological record c. 60 ka. This apparent hiatus in material culture lasts for roughly 15 millennia.

Contrary to the aforementioned, the fourth tipping point is not restricted to a particular region and/or continent; it is indeed a global phenomenon. From 45 ka, formal bone tools and personal ornaments make a lasting reappearance in the archaeological record, this time in multiple regions of the Old World. Evidence from Europe (d’Errico et al., 2003; Zilhão et al., 2010; Caron et al., 2011; d’Errico et al., 2012c; Soressi et al., 2013; Julien et al., 2019; Sano et al., 2019; Arrighi et al., 2020; Velliky et al., 2021), the Levant (Kuhn et al., 2001; Tejero et al., 2016; Tejero et al., 2018; Bar-Yosef Mayer, 2020; Tejero et al., 2020), East and South Africa (d’Errico et al., 2012b; d’Errico et al., 2020), South and Central Asia (Golovanova et al., 2010; Perera et al., 2016; Krivoshapkin et al., 2018; Shalagina et al., 2018; Belousova et al., 2020; Langley et al., 2020; Shunkov et al., 2020) as well as the Asian Pacific Island and Australia (O’Connor et al., 2014; Langley et al., 2016b; Langley et al., 2016a; Langley et al., 2019; Langley et al., 2021) attests to the penecontemporaneous development of a variety of formal bone tool types, the diversification of the manufacturing processes and techniques, the convergent innovation in the production of hunting armatures and the noticeable expansion in the variety of symbolic material culture items.

3 Pleistocene Bone Technology in China

In light of the trends identified above, one may wonder to what extent the Chinese archaeological record is comparable to the rest of the Old World when it comes to the origin and development of osseous technologies. This question is even more pertinent when we consider the central place occupied by this region in paleoanthropological studies, especially with regard to Pleistocene hominin dispersal events and complex population dynamics (Wu, 2004; Shang et al., 2007; Hou and Zhao, 2010; Keates, 2010; Liu et al., 2010; Kaifu and Fujita, 2012; Fu et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2013; Bae et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2015; Bae et al., 2017; Cai et al., 2017; Kaifu, 2017; Li et al., 2017; Martinón-Torres et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017; Bae et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019; Dennell et al., 2020; Massilani et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020; Curnoe et al., 2021; Higham and Douka, 2021; Martinón-Torres et al., 2021; Mao et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2021). In what follows, three tipping points are identified.

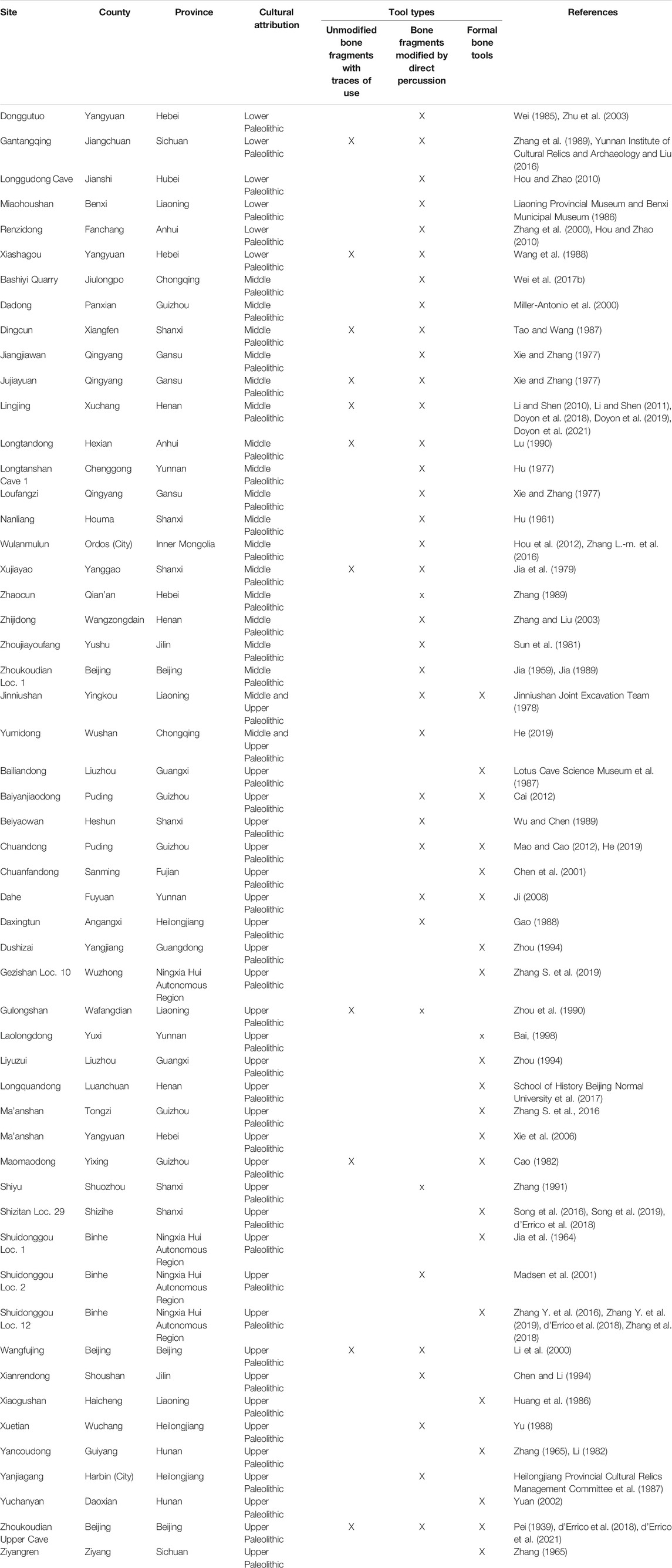

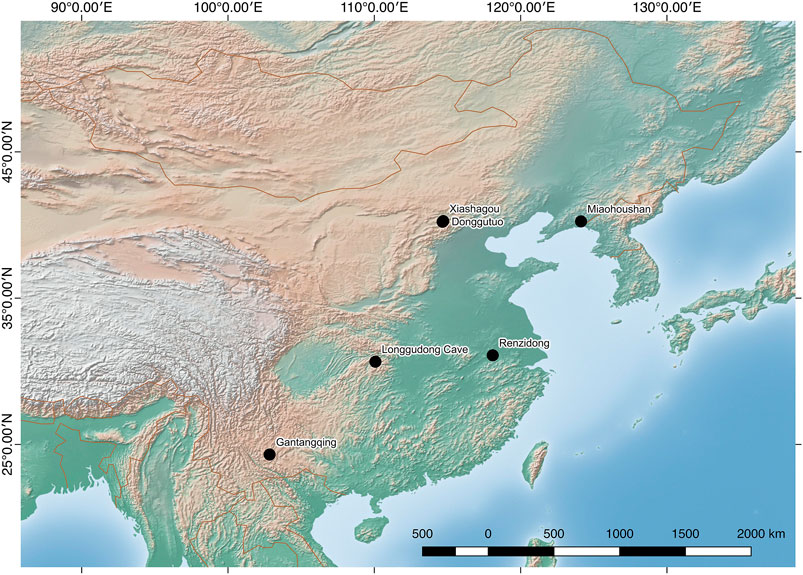

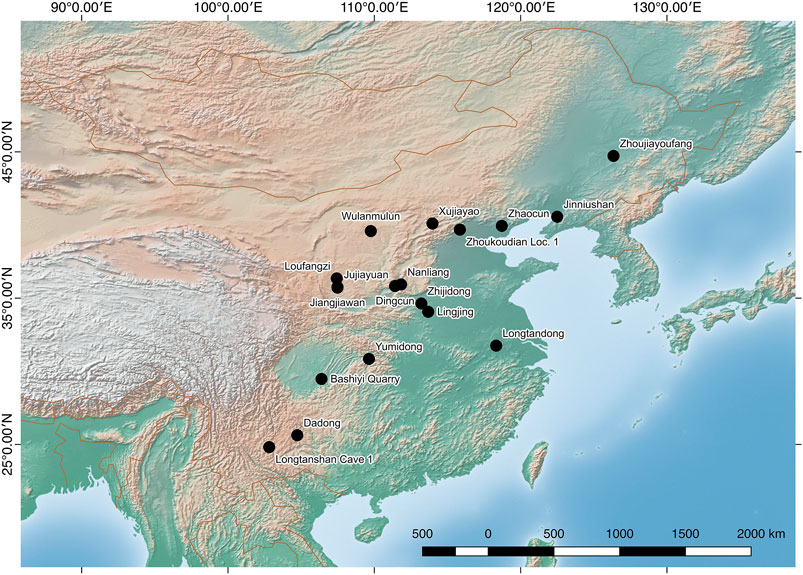

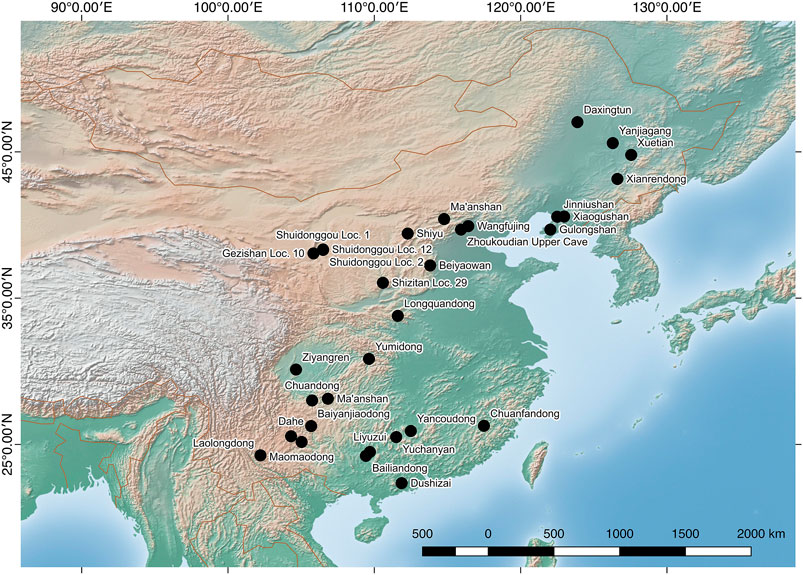

Much like the rest of the Old World, the first tipping point relates to the first occurrences of osseous technology in the archaeological record. A number of sites suggests a very ancient origin for the intentional modification of bones for technological purposes (Figure 1; Table 1). Between 1.8 and 1.0 Ma, key sites include Longgudong Cave, Renzidong, and Donggutuo (Wei, 1985; Zhang et al., 2000; Zhu et al., 2003; Li, 2004; Hou and Zhao, 2010). In all these cases, the reported tools consist of osseous fragments modified by direct percussion, i.e., in a fashion similar to stone knapping. From 1.0 Ma and throughout the Late Paleolithic, reports of similar technology are often reported in the literature (Figures 2, 3; Table 1), although some evidence would perhaps benefit from a reassessment using modern analytical methods to ensure the anthropogenic nature of the modification. Thus far, however, previous reviews have highlighted a subtle change over time when it comes to the modification of osseous remains through direct percussion (An, 2001; Feng, 2004; Wei G. et al., 2017). For most of the Early Paleolithic, the tools are generally crude and simple, and the flakes are mainly removed from the distal end of bone fragments to produce pointed implements. From the Middle and throughout the Late Paleolithic, direct percussion is used to shape the long edges of osseous fragments by a series of successive blows. In some cases, overlapping flake removal scars appear to indicate these long cutting edges were at times reshaped, perhaps to increase the longevity of the tools for whatever tasks they were considered fit (Feng, 2004).

FIGURE 1. Distribution of Chinese Lower Paleolithic sites where osseous technology was reported in the literature (see Table 1 for details). Map made by LD using QGIS v. 2.14.3-Essen (Free Software Foundation, Inc., Boston) and free vector and raster from Natural Earth (naturalearthdata.com).

FIGURE 2. Distribution of Chinese Middle Paleolithic sites where osseous technology was reported in the literature (see Table 1 for details). Map made by LD using QGIS v. 2.14.3-Essen (Free Software Foundation, Inc., Boston) and free vector and raster from Natural Earth (naturalearthdata.com).

FIGURE 3. Distribution of Chinese Upper Paleolithic sites where osseous technology was reported in the literature (see Table 1 for details). Map made by LD using QGIS v. 2.14.3-Essen (Free Software Foundation, Inc., Boston) and free vector and raster from Natural Earth (naturalearthdata.com).

In contrast to what is observed in Europe during the MIS9, one may wonder whether any hint exists in favor of a functional diversification of the expedient bone tools in China during the Middle Pleistocene. The case of Lingjing, layer 11, an early Late Pleistocene kill/butchery site dated between 125 and 105 ka, provides a peculiar outlook on this issue. This occupation layer has yielded a rich and well-preserved faunal assemblage as well as important hominin remains (Li et al., 2017). Recent research conducted by zooarchaeologists, taphonomists and technologists allowed the identification of dozens of bone tools and revealed an unsuspected behavioral complexity. The microscopic observation of bone surface modifications permitted the recognition of antler soft hammers, i.e., tools used to remove flakes from a block during stone knapping (Doyon et al., 2018); bone retouchers as well as passive and active pressure flakers made of bone and antler, i.e., three tool types used to shape and retouch the cutting edges of stone implements but used in distinct motions (Doyon et al., 2019); and, equid and bovid metapodials used in long bone fracturing activities to access the marrow (van Kolfschoten et al., 2020; Bonhof and van Kolfschoten, 2021). Furthermore, two large mammal rib bone fragments bearing a pattern consisting of sequential linear incisions–one of them preserves remnants of ochre residues between and within the lines on its surface–suggest the visitors at the site may have intended to permanently record information on these remains or express some form of symbolic behaviors while producing the patterns (Li et al., 2019). During the 2005–2018 excavations of layer 11, some osseous fragments were isolated owing to the multiple flake removal scars they bear and, in some cases, the presence of an unusual polish (Li and Shen, 2010, 2011; Doyon et al., 2021). Experimentation in fracturing horse long bones for marrow extraction evidenced this activity could not account for the number and relative position of the flake removal scars observed on many archaeological specimens. It was therefore suggested that a sub-sample of 56 items were deliberately modified and could be interpreted as expedient bone tools (Doyon et al., 2021). Finally, morphometric comparison of these tools yielded surprising results. Among bone retouchers, the Lingjing visitors appear to have selected cervid metapodials to use them over long periods of time. These specimens present a high degree of standardization compared to the other large mammal long bone fragments used as retouchers and found at the site. This morphometric standardization was achieved by the marginal shaping through direct percussion, which likely increase the tool’s prehensility and ergonomic (Doyon et al., 2018). Likewise, when comparing the dimension of the stone tools and the bone fragments with flake removal scars interpreted as expedient tools, a morphometric continuum is demonstrated, which appears to indicate a functional complementarity between the two aspects of material culture. Given the site function, it was hypothesized these bone tools may have been used in butchery and carcass processing activities (Doyon et al., 2021). Collectively, the results from Lingjing suggest we are in presence of a long-lasting tradition. The breath of activities in which bone implements are used, the evident selection in raw material for tools devoted to specific activities or receiving particular care, and the morphometric complementarity between lithic and bone tools are all indicators suggesting that a functional diversification in osseous technologies was well-established by the end of MIS6 and the onset of MIS5. In this sense, Lingjing represents, in and of itself, a second tipping point in the evolution of Chinese Pleistocene bone technology. Future research on the origin of this cultural adaptive system may very likely push back the timing of this functional diversification, and perhaps make it comparable to what is observed in Europe.

The third tipping point occurs between 40 and 35 ka. As it was the case in the rest of the Old World, this period testifies to the emergence of formal bone tools both in North and South China (Figure 3; Table 1). These two regions attest to a convergent evolution in hunting implements. Indeed, the barbed and projectile armatures from Xiaogushan in the North (Huang et al., 1986; Zhang et al., 2010) are broadly contemporaneous with the barbed implements from Ma’anshan in the South (Zhang L.-m. et al., 2016). Throughout the Late Paleolithic, a diversification in formal bone tool types is apparent in the Chinese archaeological record (e.g., Qu et al., 2013; Zhang S. et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018; d’Errico et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020). Furthermore, manufacturing techniques befitted for the transformation of osseous materials are being developed. Some techniques, such as scraping, incising, gouging, or grooving, are identical to those developed in the rest of the Old World. Others, however, appear to be more regionally circumscribed. This is the case for grinding, an ubiquitous technique used in formal bone tool manufacture in Asia during the Late Paleolithic (Rabett and Piper, 2012; O’Connor et al., 2014; Aplin et al., 2016; Zhang Y. et al., 2016; Perera et al., 2016; Li et al., 2020), yet, seldom observed in European Upper Paleolithic (Camps-Faber, 1976; d’Errico et al., 2012c; Goutas, 2013; Langley, 2016) or in African Middle Stone Age contexts (d’Errico and Henshilwood, 2007; Backwell and d’Errico, 2016; Vanhaeren et al., 2019). Outside Asia, grinding only becomes a common shaping technique in Africa during the Later Stone Age (Yellen, 1998; Bradfield, 2016). Likewise, at the end of the Late Paleolithic, past populations in North China appear to have specifically selected burnt bones, if not deliberately heated bone fragments in an anaerobic environment to change the color of the whole cortical bone rather than only its surface, to manufacture portable artwork (Li et al., 2020). Although bone discoloration can be achieved through multiple ways (e.g., Bradfield, 2018), a similar process has only been reported for the manufacture of blacken shell beads from Blombos Cave (d’Errico et al., 2015). Finally, a number of North Chinese sites suggests that the emergence of personal ornaments preceded the first occurrences of formal bone tools in the region by a few millennia. This is the case for instance at Shizitan, Shuidonggou and Zhoukoudian Upper Cave (Wei et al., 2016; Wei Y. et al., 2017; Song et al., 2017; d’Errico et al., 2018; d’Errico et al., 2021).

4 Discussion

The present review on the origin and development of osseous technologies in the Old World, and the particular focus given to the Chinese archaeological record, sets the stage for a comparison of the cultural trajectories at a regional and global scales. When the timing and nature of the tipping points are considered, it becomes apparent that these trajectories are broadly similar. Despite an early appearance of bone tools in East and South Africa, evidence from China suggests that the first hominins whom dispersed in this region were carrier of a set of knowledge which allowed them to modify butchery and carcass processing by-products for technological purposes. The numerous reports from Early, Middle and Late Pleistocene contexts indicate this aspect of material culture remained in the toolkit of the populations that lived in China throughout this epoch.

From MIS9 onward, two lines of evidence indicates that the functional diversification of expedient bone tools observed in Europe is perhaps not restricted to this region, but could, in fact, constitute a trend that extends across the Eurasian continent. First, a clear difference emerges in the shaping of expedient tools during this period in China. Although direct percussion remains the predominant shaping technique, its application aims to produce long cutting edges rather then pointed objects. Second, the behavioural standardization illustrated at Lingjing is comparable to a similar trend documented in Europe for the manufacture and use of bone retouchers (Daujeard et al., 2014; Costamagno et al., 2018; Martellotta et al., 2020). The same is true for the tool types found at Lingjing, which bears numerous resemblances with those found at Schöningen for instance (Julien et al., 2015; Bonhof and van Kolfschoten, 2021). Collectively, these observations suggest that Lingjing, rather than representing an outlier in the Chinese archaeological record, likely provides a snapshot on a regional cultural trajectory that may become more and more comparable with the European one with future discoveries.

The last similitude refers to the emergence of formal bone tools. We now have ample clues in favor of a convergent cultural innovation throughout the Old World around 45 ka. The Chinese archaeological record shows this development is contemporaneously occurring in East Asia as well. Across the world, this cultural change appears closely linked with the development of hunting armatures and a paraphernalia of other tool types, and signals an increase complexification in prehistoric technological organization. It must be stressed here, however, that the emergence of formal tools didn’t entail the abandonment of expedient bone tools by Upper and Late Paleolithic populations. Quite the contrary, formal bone tools augmented the pre-existing toolkit they inherited. This accretion process likely signals an increase reliance on complex technologies by these human groups (Kuhn, 2020). The easy access to workable skeletal remains from hunting and carcass processing activities, the lighter weight of bone technologies compared to lithic implements, their durability and maintenance properties (sensu Bleed, 1986; Bamforth, 1986) were likely key factors favouring the adoption of this lasting innovation by highly mobile hunter-gatherer populations.

Two differences stand out when comparing the cultural trajectories from China to those from the rest of the Old World. First, to this day, evidence for an “early” emergence of formal bone tools is restricted to the African continent between 90 and 65 ka. This phenomenon is even more peculiar when we consider the pattern of regionalization in tool type distribution and the fact that this category of osseous technology abruptly disappears from the archaeological record after 60 ka (see below). Second, when formal bone tools reemerge around 45 ka, the technical know-hows implemented for their manufacture show subtle, yet lasting, variation in their distribution. A potent example of this variation lies in the ubiquity of grinding used as a shaping technique in Asia and Africa, and its relative absence in other part of the world.

Based on the above review and regional comparison, future studies on osseous technology should address a number of research priorities. These research prospects are grouped below by main categories of bone tools. They primarily aim to fill the gaps in our understanding of this aspect of material culture to provide a complementary perspective to lithic tools in cultural evolution studies.

Thus far, research on “expedient tools” have mainly focused on bone retouchers, a tool type that lies at the interface between lithic and bone technologies. We now have ample evidence that early hominin technological adaptive systems also included the exploitation of skeletal elements for other activities. Therefore, future studies should be articulated along two main axes. First, more experimental programs must be implemented to test the criteria suggested to recognize intentionally modified osseous fragments (e.g., Backwell and d’Errico, 2004; Doyon et al., 2021). Such criteria would allow zooarchaeologists and taphonomists to quickly identify faunal remains that should be subjected to a thorough technological analysis. Second, and in parallel with the first axis, more use-wear studies, both experimental and archaeological, should be undertaken to establish the activities in which these tools served a purpose (e.g., Shipman and Rose, 1983; Baumann et al., 2020; Mateo-Lomba et al., 2020). The development of use-wear method in China, in particular, would allow archaeologists to move away from typological approaches when dealing with expedient tools (e.g., An, 2001). Indeed, a major setback of such classification systems, too often inspired by lithic typology, lies in the fact that these tool types carry a functional meaning that may not correspond to the activities for which they were used. Instead of reducing the development of osseous technologies to a succession of tool types, studies in cultural evolution should focus more on the choices made by past population regarding the selection of skeletal elements, the methods used to modify them and the role these objects fulfilled in the technological system. From a chronological standpoint, these two research axes should not be restricted to period preceding the emergence of formal bone tools; they must also be extended to more recent Paleolithic periods, i.e., Upper and Late Paleolithic, to depict a clearer picture on how different osseous technological adaptations co-evolved in time.

Two main research axes are also identified for the study of “formal bone tools.” First, although these tools have historically received most of the attention in archaeology, owing in part to the ease to identify them and for their crucial role in establishing chrono-cultural timelines, the nature of the data available to address questions related to cultural evolution is fairly uneven at a global scale. While data stemming from the application of the chaîne opératoires concept is commonplace in Europe, its application to the Chinese archaeological record remains exceptional (for a review, see Yin et al., 2021). However, this tool allows to detail the decision process implemented by prehistoric groups for the manufacture and use of bone technologies. Variation in these decisions are extremely instructive; they can help define boundaries between groups carrying different sets of knowledge as well as establish whether or not interactions existed between these groups. These variations can also be correlated with environmental and/or social variables to better apprehend the mechanisms and processes at the origin of change in the different cultural adaptive systems. Second, regional- and global-scale syntheses using multivariate analyses are essential in the near future. In spite of being usually restricted to a single tool type (Stordeur-Yedid, 1979; d’Errico et al., 2018; Doyon, 2019; Doyon, 2020), these syntheses illustrate their aptitude to retrace cultural phylogenies, explore topic such as technological organization and population dynamics during the Pleistocene. Bone technologists may find inspiration in analogous projects undertaken to investigate the variation in personal ornaments (Vanhaeren and d’Errico, 2006; McAdam, 2008; d’Errico and Vanhaeren, 2015; Rigaud et al., 2015; Rigaud et al., 2018; Balme and O’Connor, 2019; d’Errico et al., 2021), and confront their results to other aspects of material culture to provide a nuanced outlook on topics such as cultural innovations and transmission during the Pleistocene. From a chronological standpoint, a key question that needs to be tackled relates to the circumstances surrounding the circa 15-ka hiatus in “formal bone tools” between their first emergence and disappearance in the African record, and their convergent reappearance across the Old World around 45 ka. Addressing such issue requires to confront multiple regional cultural trajectories and engage in a sustained dialogue with specialists from other disciplines, e.g., paleoanthropology, paleogenetic, paleoenvironmental sciences, etc., in an attempt to comprehend whether, and to what extent, changes in osseous–and other–technology throughout the Pleistocene match the complex dynamics reflected in the evolution of our genus.

Author Contributions

LD designed the study. MS and LD conducted the study. LD wrote the initial version of the manuscript. MS and LD reviewed and edited the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation through the China/Shandong University International Postdoctoral Exchange Program, the PHC Xu Guangqi program (grant # 41230RB), the “Talent” program by Initiative d’Excellence, Université de Bordeaux (grant # 191022_001), and the French government in the framework of the University of Bordeaux’s IdEx “Investments for the Future” program/GPR Human Past. PACEA (CNRS UMR5199) is a Partner team of the Labex LaScArBx-ANR (ANR-10-LABX-52). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the Editor, Zhang Dongju, and two reviewers for their comments and suggestions which greatly helped improving the manuscript.

References

Abrams, G., Bello, S. M., Di Modica, K., Pirson, S., and Bonjean, D. (2014). When Neanderthals Used Cave Bear (Ursus Spelaeus) Remains: Bone Retouchers from Unit 5 of Scladina Cave (Belgium). Quat. Int. 326-327, 274–287. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.10.022

An, J. Y. (2001). On Bone-Antler-Horn Tools from the Central North China. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 20, 319–330. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Anzidei, A. P., Bulgarelli, G. M., Catalano, P., Cerilli, E., Gallotti, R., Lemorini, C., et al. (2012). Ongoing research at the late Middle Pleistocene site of La Polledrara di Cecanibbio (central Italy), with emphasis on human-elephant relationships. Quat. Int. 255, 171–187. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.06.005

Aplin, K., O’Connor, S., Bulbeck, D., Piper, P. J., Marwick, B., Pierre, E. S., et al. (2016). “The Walandawe Tradition from Southeast Sulawesi and Osseous Artifact Traditions in Island Southeast Asia,” in Osseous Projectile Weaponry. Editor M. C. Langley (Derdrecht: Springer), 189–208. doi:10.1007/978-94-024-0899-7_13

Arrighi, S., Moroni, A., Tassoni, L., Boschin, F., Badino, F., Bortolini, E., et al. (2020). Bone Tools, Ornaments and Other Unusual Objects during the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic Transition in Italy. Quat. Int. 551, 169–187. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2019.11.016

A., S., M., B., K., K., and A., K. (2018). Bone Needles from Upper Paleolithic Сomplexes of the Strashnaya Cave (North-Western Altai). tpai 21, 89–98. doi:10.14258/tpai(2018)1(21).-07

Backwell, L., and d'Errico, F. (2008). Early Hominid Bone Tools from Drimolen, South Africa. J. Archaeological Sci. 35, 2880–2894. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.05.017

Backwell, L., and d’Errico, F. (2016). “Osseous Projectile Weaponry from Early to Late Middle Stone Age Africa,” in Osseous Projectile Weaponry. Editor M. C. Langley (Dordrecht: Springer), 15–29. doi:10.1007/978-94-024-0899-7_2

Backwell, L. R., and d'Errico, F. (2001). Evidence of Termite Foraging by Swartkrans Early Hominids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98, 1358–1363. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.4.1358

Backwell, L. R., and d’Errico, F. (2004). The First Use of Bone Tools: a Reappraisal of the Evidence from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. Palaeontol. Africana 40, 95–158.

Bae, C. J., Douka, K., and Petraglia, M. D. (2017). On the Origin of Modern Humans: Asian Perspectives. Science 358, eaai9067. doi:10.1126/science.aai9067

Bae, C. J., Li, F., Cheng, L., Wang, W., and Hong, H. (2018). Hominin Distribution and Density Patterns in Pleistocene China: Climatic Influences. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 512, 118–131. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.03.015

Bae, C. J., Wang, W., Zhao, J., Huang, S., Tian, F., and Shen, G. (2014). Modern Human Teeth from Late Pleistocene Luna Cave (Guangxi, China). Quat. Int. 354, 169–183. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.06.051

Bai, Z. (1998). A Preliminary Study on the Prehistoric Site of Laolongdong. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 17, 212–229. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Balme, J., and O’Connor, S. (2019). Bead Making in Aboriginal Australia from the Deep Past to European Arrival: Materials, Methods, and Meanings. PaleoAnthropology, 177–195. doi:10.4207/PA.2019.ART130

Bar-Yosef Mayer, D. E. (2020). “Shell Beads of the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic: a Review of the Earliest Record,” in Beauty and the Eye of the Beholder: Personal Adornments across the Millennia. Editors M. Mărgărit, and A. Boroneanț (Târgovişte: Cetatea de scaun), 11–25.

Bar-Yosef Mayer, D. E., Vandermeersch, B., and Bar-Yosef, O. (2009). Shells and Ochre in Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh Cave, Israel: Indications for Modern Behavior. J. Hum. Evol. 56, 307–314. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.10.005

Baumann, M., Plisson, H., Rendu, W., Maury, S., Kolobova, K., and Krivoshapkin, A. (2020). The Neandertal Bone Industry at Chagyrskaya Cave, Altai Region, Russia. Quat. Int. 559, 68–88. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.06.019

Bamforth, D. B. (1986). Technological Efficiency and Tool Curation. American Antiquity 51, 38–50. doi:10.2307/280392

Belousova, N. E., Fedorchenko, A. Y., Rybin, E. P., Seletskiy, M. V., Brown, S., Douka, K., et al. (2020). The Early Upper Palaeolithic Bone Industry of the Central Altai, Russia: New Evidence from the Kara-Bom Site. Antiquity 94, e26. doi:10.15184/aqy.2020.137

Blasco, R., Rosell, J., Cuartero, F., Fernández Peris, J., Gopher, A., and Barkai, R. (2013). Using Bones to Shape Stones: MIS 9 Bone Retouchers at Both Edges of the Mediterranean Sea. PLoS ONE 8, e76780. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076780

Bleed, P. (1986). The Optimal Design of Hunting Weapons: Maintainability or Reliability. American Antiquity 51, 737–747. doi:10.2307/280862

Bonhof, W. J., and van Kolfschoten, T. (2021). The Metapodial Hammers from the Lower Palaeolithic Site of Schöningen 13 II-4 (Germany): The Results of Experimental Research. J. Archaeological Sci. Rep. 35, 102685. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102685

Boschian, G., and Saccà, D. (2015). In the elephant, everything is good: Carcass use and re-use at Castel di Guido (Italy). Quat. Int. 361, 288–296. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.04.030

Bouzouggar, A., Barton, N., Vanhaeren, M., d'Errico, F., Collcutt, S., Higham, T., et al. (2007). 82,000-Year-Old Shell Beads from North Africa and Implications for the Origins of Modern Human Behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104, 9964–9969. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703877104

Bouzouggar, A., Humphrey, L. T., Barton, N., Parfitt, S. A., Clark Balzan, L., Schwenninger, J.-L., et al. (2018). 90,000 Year-Old Specialised Bone Technology in the Aterian Middle Stone Age of North Africa. PLoS One 13, e0202021. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0202021

Bradfield, J. (2016). “Bone Point Functional Diversity: A Cautionary Tale from Southern Africa,” in Osseous Projectile Weaponry. Editor M. C. Langley (Dordrecht: Springer), 31–40. doi:10.1007/978-94-024-0899-7_3

Bradfield, J., Lombard, M., Reynard, J., and Wurz, S. (2020). Further Evidence for Bow Hunting and its Implications More Than 60 000 Years Ago: Results of a Use-Trace Analysis of the Bone Point from Klasies River Main Site, South Africa. Quat. Sci. Rev. 236, 106295. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106295

Bradfield, J. (2018). Some Thoughts on Bone Artefact Discolouration at Archaeological Sites. J. Archaeological Sci. Rep. 17, 500–509. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.12.022

Brain, C. K., and Shipman, P. (1993). “The Swartkrans Bone Tools,” in Swartkrans, a Cave’s Chronicle of Early Man. Editor C. K. Brain (Cape Town: C.T.P. Book Printers), 195–215.

Burke, A., and d'Errico, F. (2008). A Middle Palaeolithic Bone Tool from Crimea (Ukraine). Antiquity 82, 843–852. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00097611

Cai, H. (2012). “白岩脚洞的人化石和骨制品 (Human Fossils and Bone Artifacts from the Baiyanjiao Cave Site of Puding, Guizhou Province),” in Proceedings of the Thirteenth Annual Meeting of the Chinese Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. Editor W. Dong (Beijing: China Ocean Press), 203–210. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Cai, Y., Qiang, X., Wang, X., Jin, C., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., et al. (2017). The Age of Human Remains and Associated Fauna from Zhiren Cave in Guangxi, Southern China. Quat. Int. 434, 84–91. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.12.088

Camps-Faber, H. (1976). “Le travail de l’os,” in La Préhistoire Française I. Editor H. de Lumley(Paris: CNRS), 717–722.

Cao, Z. (1982). The Preliminary Study of Bone Tools and Antler Spades from the Rock Shelter Site of Maomaodong. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 1, 36–41. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Caron, F., d'Errico, F., Del Moral, P., Santos, F., and Zilhão, J. (2011). The Reality of Neandertal Symbolic Behavior at the Grotte du Renne, Arcy-sur-Cure, France. PLoS ONE 6, e21545. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021545

Chen, F., Welker, F., Shen, C.-C., Bailey, S. E., Bergmann, I., Davis, S., et al. (2019). A Late Middle Pleistocene Denisovan Mandible from the Tibetan Plateau. Nature 569, 409–412. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1139-x

Chen, Q., and Li, Q. (1994). A Brief Report on Xianrendong Cave Site, Jilin Province. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 13, 12–19. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Chen, Z., Li, J., and Yu, S. (2001). A Paleolithic Site at Chuanfandong in Sanming City, Fujian Province. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 20, 256–270. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Costamagno, S., Bourguignon, L., Soulier, M.-C., Meignen, L., Beauval, C., Rendu, W., et al. (2018). “Bone Retouchers and Site Function in the Quina Mousterian: the Case of Les Pradelles (Marillac-Le-Franc, France),” in The Origins of Bone Tool Technologies. Editors J. M. Hutson, A. García-Moreno, E. S. Noack, E. Turner, A. Villaluenga, and S. Gaudzinski-Windheuser (Mainz: Römisch Germanisches ZentralMuseum), 165–195.

Curnoe, D., Li, H.-c., Zhou, B.-y., Sun, C., Du, P.-x., Wen, S.-q., et al. (2021). Reply to Martinón-Torres et al. and Higham and Douka: Refusal to acknowledge dating complexities of Fuyan Cave strengthens our case. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2104818118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2104818118

d'Errico, F., Backwell, L. R., and Wadley, L. (2012a). Identifying Regional Variability in Middle Stone Age Bone Technology: the Case of Sibudu Cave. J. Archaeological Sci. 39, 2479–2495. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.01.040

d'Errico, F., Backwell, L., Villa, P., Degano, I., Lucejko, J. J., Bamford, M. K., et al. (2012b). Early Evidence of San Material Culture Represented by Organic Artifacts from Border Cave, South Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 13214–13219. doi:10.1073/pnas.1204213109

d’Errico, F., and Backwell, L. R. (2003). Possible Evidence of Bone Tool Shaping by Swartkrans Early Hominids. J. Archaeol. Sci. 30, 1559–1576. doi:10.1016/S0305-4403(03)00052-9

d’Errico, F., Borgia, V., and Ronchitelli, A. (2012c). Uluzzian Bone Technology and its Implications for the Origin of Behavioural Modernity. Quat. Int. 259, 59–71. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.03.039

d’Errico, F., Doyon, L., Zhang, S., Baumann, M., Lázničková-Galetová, M., Gao, X., et al. (2018). The Origin and Evolution of Sewing Technologies in Eurasia and North America. J. Hum. Evol. 125, 71–86. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.10.004

d'Errico, F., and Henshilwood, C. S. (2007). Additional Evidence for Bone Technology in the Southern African Middle Stone Age. J. Hum. Evol. 52, 142–163. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.08.003

d'Errico, F., Henshilwood, C., Vanhaeren, M., and van Niekerk, K. (2005). Nassarius Kraussianus Shell Beads from Blombos Cave: Evidence for Symbolic Behaviour in the Middle Stone Age. J. Hum. Evol. 48, 3–24. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.09.002

d’Errico, F., Julien, M., Liolios, D., Vanhaeren, M., and Baffier, D. (2003). “Many Awls in our Argument. Bone Tool Manufacture and Use in the Châtelperronian and Aurignacian Levels of the Grotte du Renne at Arcy-sur-Cure,” in The Chronology of the Aurignacian and of the Transitional Technocomplexes: Dating, Stratigraphies, Cultural Implications. Editors J. Zilhao, and F. d’Errico (Lisboa: Insttito Português de Arqueologia), 247–270.

d’Errico, F., Pitarch Martí, A., Shipton, C., Le Vraux, E., Ndiema, E., Goldstein, S., et al. (2020). Trajectories of Cultural Innovation from the Middle to Later Stone Age in Eastern Africa: Personal Ornaments, Bone Artifacts, and Ocher from Panga Ya Saidi, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 141, 102737. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.102737

d’Errico, F., Pitarch Martí, A., Wei, Y., Gao, X., Vanhaeren, M., and Doyon, L. (2021). Zhoukoudian Upper Cave Personal Ornaments and Ochre: Rediscovery and Reevaluation. J. Hum. Evol. 161, 103088. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2021.103088

d’Errico, F., and Vanhaeren, M. (2015). “Upper Palaeolithic Mortuary Practices: Reflection of Ethnic Affiliation, Social Complexity and Cultural Turn over,” in ” in Death Shall Have No Dominion. Editors C. Renfrew, M. J. Boyd, and I. Morley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 45–61.

d'Errico, F., Vanhaeren, M., Barton, N., Bouzouggar, A., Mienis, H., Richter, D., et al. (2009). Additional Evidence on the Use of Personal Ornaments in the Middle Paleolithic of North Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 16051–16056. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903532106

d'Errico, F., Vanhaeren, M., Van Niekerk, K., Henshilwood, C. S., and Erasmus, R. M. (2015). Assessing the Accidental versus Deliberate Colour Modification of Shell Beads: a Case Study on PerforatedNassarius Kraussianusfrom Blombos Cave Middle Stone Age Levels. Archaeometry 57, 51–76. doi:10.1111/arcm.12072

d'Errico, F., Vanhaeren, M., and Wadley, L. (2008). Possible Shell Beads from the Middle Stone Age Layers of Sibudu Cave, South Africa. J. Archaeological Sci. 35, 2675–2685. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.04.023

Daujeard, C. (2007). “Exploitation intensive des carcasses de Cerf dans le gisement paléolithique moyen de la grotte de Saint-Marcel (Ardèche),” in Un siècle de construction du discours scientifique en Préhistoire (Paris: Société Préhistorique de France), Vol. III, 481–497.Actes du congrès du centenaire de la Société Préhistorique Française, Avignon-Bonnieux, 20-25 septembre 2004

Daujeard, C., Moncel, M.-H., Fiore, I., Tagliacozzo, A., Bindon, P., Raynal, J.-P., et al. (2014). Middle Paleolithic Bone Retouchers in Southeastern France: Variability and Functionality. Quat. Int. 326-327, 492–518. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.12.022

Daujeard, C., Valensi, P., Fiore, I., Moigne, A.-M., Tagliacozzo, A., Moncel, M.-H., et al. (2018). “A Reappraisal of Lower to Middle Palaeolithic Bone Retouchers from Southeastern France (MIS 11 to 3),”. The Origins of Bone Tool Technologies. Editors J. M. Hutson, E. S. Noack, E. Turner, A. Villaluenga, and S. Gaudzinski-Windheuser (Mainz: Römisch Germanisches ZentralMuseum), 93–132.

Dennell, R., Martinón-Torres, M., Bermúdez de Castro, J.-M., and Xing, G. (2020). A Demographic History of Late Pleistocene China. Quat. Int. 559, 4–13. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.03.014

Di Buduo, G. M., Costantini, L., Fiore, I., Marra, F., Palladino, D. M., Petronio, C., et al. (2020). The Bucobello 322 Ka-Fossil-Bearing Volcaniclastic-Flow Deposit in the Eastern Vulsini Volcanic District (Central Italy): Mechanism of Emplacement and Insights on Human Activity during MIS 9. Quat. Int. 554, 75–89. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.04.046

Dominguezrodrigo, M., Raynepickering, T., Semaw, S., and Rogers, M. (2005). Cutmarked Bones from Pliocene Archaeological Sites at Gona, Afar, Ethiopia: Implications for the Function of the World's Oldest Stone Tools. J. Hum. Evol. 48, 109–121. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.09.004

Doyon, L., Li, H., Li, Z., Wang, H., and Zhao, Q. (2019). Further Evidence of Organic Soft Hammer Percussion and Pressure Retouch from Lingjing (Xuchang, Henan, China). Lithic Techn. 44, 100–117. doi:10.1080/01977261.2019.1589926

Doyon, L., Li, Z., Li, H., and d’Errico, F. (2018). Discovery of Circa 115,000-Year-Old Bone Retouchers at Lingjing, Henan, China. PLoS ONE 13, e0194318. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0194318

Doyon, L., Li, Z., Wang, H., Geis, L., and d’Errico, F. (2021). A 115,000-Year-Old Expedient Bone Technology at Lingjing, Henan, China. PLoS ONE 16, e0250156. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0250156

Doyon, L. (2019). On the Shape of Things: a Geometric Morphometrics Approach to Investigate Aurignacian Group Membership. J. Archaeological Sci. 101, 99–114. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2018.11.009

Doyon, L. (2020). The Cultural Trajectories of Aurignacian Osseous Projectile Points in Southern Europe: Insights from Geometric Morphometrics. Quat. Int. 551, 63–84. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2018.12.010

Feng, X. (2004). “History and Status Quo of the Research on Paleolithic Bone Artifacts and Hornwork in China,” in Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Meeting of the Chinese Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. Editor W. Dong (Beijing: China Ocean Press), 183–191.

Fu, Q., Meyer, M., Gao, X., Stenzel, U., Burbano, H. A., Kelso, J., et al. (2013). DNA Analysis of an Early Modern Human from Tianyuan Cave, China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 2223–2227. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221359110

Gao, X. (1988). New Discoveries of Paleoliths from Angangxi, Heilongjiang Province. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 7, 84–88. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Golovanova, L. V., Doronichev, V. B., and Cleghorn, N. E. (2010). The Emergence of Bone-Working and Ornamental Art in the Caucasian Upper Palaeolithic. Antiquity 84, 299–320. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0006659X

Goren-Inbar, N. (2011). “Behavioral and Cultural Origins of Neanderthals: A Levantine Perspective,” in “Behavioral and Cultural Origins of Neanderthals: A Levantine Perspective,” in Continuity and Discontinuity in the Peopling of Europe. Editors S. Condemi, and G.-C. Weniger (Dordrecht: Springer), 89–100. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-0492-3_8

Goutas, N. (2013). “De Brassempouy à Kostienki : l’exploitation technique des ressources animales dans l’Europe gravettienne,” in Les Gravettiens. Editor M. Otte (Paris: Éditions Errance), 105–162.

Hallett, E. Y., Marean, C. W., Steele, T. E., Álvarez-Fernández, E., Jacobs, Z., Cerasoni, J. N., et al. (2021). A Worked Bone Assemblage from 120,000-90,000 Year Old Deposits at Contrebandiers Cave, Atlantic Coast, Morocco. iScience 24, 102988. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.102988

Hanon, R., d'Errico, F., Backwell, L., Prat, S., Péan, S., and Patou-Mathis, M. (2021). New Evidence of Bone Tool Use by Early Pleistocene Hominins from Cooper's D, Bloubank Valley, South Africa. J. Archaeological Sci. Rep. 39, 103129. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.103129

Harmand, S., Lewis, J. E., Feibel, C. S., Lepre, C. J., Prat, S., Lenoble, A., et al. (2015). 3.3-Million-Year-Old Stone Tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya. Nature 521, 310–315. doi:10.1038/nature14464

He, C. (2019). 重庆玉米洞遗址石器工业的剥片技术与策略选择 (Lithic Industry at the Yumidong Site in Chongqing: Flaking Technology and Strategic Decision-Making). 江汉考古 (Jianghan Archaeology) 165, 72–80. (in Chinese).

Heilongjiang Provincial Cultural Relics Management Committee (1987). 闫家岗旧石器时代晚期古营地遗址 (Yanjiagang, an Ancient Camp Site from the Late Paleolithic). Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House. (in Chinese).Harbin Cultural Bureau, and Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology

Henshilwood, C. S., D'errico, F., Marean, C. W., Milo, R. G., and Yates, R. (2001). An Early Bone Tool Industry from the Middle Stone Age at Blombos Cave, South Africa: Implications for the Origins of Modern Human Behaviour, Symbolism and Language. J. Hum. Evol. 41, 631–678. doi:10.1006/jhev.2001.0515

Higham, T. F. G., and Douka, K. (2021). The Reliability of Late Radiocarbon Dates from the Paleolithic of Southern China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2103798118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2103798118

Hou, Y. M., and Zhao, L. X. (2010). An Archeological View for the Presence of Early Humans in China. Quat. Int. 223-224, 10–19. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2009.09.025

Hou, Y., Wang, Z., Yang, Z., Zhen, Z., Zhang, J., Dong, W., et al. (2012). The First Trial Excavation and Significance of Wulanmulun Site in 2010 at Ordos, Inner Mongolia in North China. Quat. Sci. 32, 178–187.

Hu, J. (1961). 山西侯马市南梁旧石器遣址中的骨器 (Bone Artifacts in Nanliang Paleolithic Site in Houyan City, Shanxi). 考古 (Archaeology) 1, 20–22. (in Chinese).

Hu, Shaojin. (1977). 云南省呈贡县发现旧石器 (Paleolithic Finds in Chenggong County, Yunnan Province). Vertebrata PalAsiatica 15, 223–228. (in Chinese).

Huang, W. W., Zhang, Z. H., Fu, R. Y., Chen, B. F., Liu, J. Y., Zhu, M. Y., et al. (1986). Bone Artifacts and Ornaments from Xiaogushan Site of Haicheng, Liaoning Province. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 5, 259–266. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Ji, X. (2008). 大河洞穴之魅 富源大河旧石器遗址揭秘 (The Charm of Dahe Caves. The Discovery of Fuyuan Dahe Paleolithic Site). 中国文化遗产 (Chinese Cultural Heritage) 6, 78–83.

Jia, L., Gai, P., and Li, Y. (1964). 水洞沟旧石器时代遗址的新材料 (New Materials from the Paleolithic Site of Shuidonggou). Vert. Palasiat. 8, 75–86. (in Chinese).

Jia, L. (1959). Notes on the Bone Implements of Sinanthropus. Acta Archaeol. Sinica 3, 1–6. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Jia, L. (1989). On Problems of the Beijing-Man Site: A Critique of New Interpretations. Curr. Anthropol. 30, 200–205. doi:10.1086/203727

Jia, L., Wei, Q., and Li, C. (1979). Report on the Excavation of Xujiayao Man Site in 1976. Vert. Palasiat. 17, 277–293. (in Chinese).

Jinniushan Joint Excavation Team (1978). 辽宁营口金牛山旧石器文化的研究 (A Study on the Paleolithic Culture of Jinniu Mountain in Yingkou, Liaoning). Vert. Palasiat. 16, 129–136. (in Chinese).

Joordens, J. C. A., d’Errico, F., Wesselingh, F. P., Munro, S., de Vos, J., Wallinga, J., et al. (2015). Homo Erectus at Trinil on Java Used Shells for Tool Production and Engraving. Nature 518, 228–231. doi:10.1038/nature13962

Julien, M.-A., Hardy, B., Stahlschmidt, M. C., Urban, B., Serangeli, J., and Conard, N. J. (2015). Characterizing the Lower Paleolithic Bone Industry from Schöningen 12 II: A Multi-Proxy Study. J. Hum. Evol. 89, 264–286. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.10.006

Julien, M., Vanhaeren, M., and d’Errico, F. (2019). “L’industrie Osseuse,” in Le Châtelperronien de la grotte du Renne (Arcy-sur-Cure, Yonne, France) : les fouilles d’André Leroi-Gourhan (1949-1963). Les Eyzies-de-Tayac: Société des Amis du Musée national de Préhistoire et de la Recherche archéologique). Editors M. Julien, F. David, M. Girard, and A. Roblin-Jouve, 1–52.

Kaifu, Y. (2017). Archaic Hominin Populations in Asia before the Arrival of Modern Humans. Curr. Anthropol. 58, S418–S433. doi:10.1086/694318

Kaifu, Y., and Fujita, M. (2012). Fossil Record of Early Modern Humans in East Asia. Quat. Int. 248, 2–11. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.02.017

Keates, S. G. (2010). The Chronology of Pleistocene Modern Humans in China, Korea, and Japan. Radiocarbon 52, 428–465. doi:10.1017/S0033822200045483

Kretzoi, M., and Dobosi, V. T. (1990). Vértesszőlős: Site, Man and Culture. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Krivoshapkin, A., Shalagina, A., Baumann, M., Shnaider, S., and Kolobova, K. (2018). Between Denisovans and Neanderthals: Strashnaya Cave in the Altai Mountains. Antiquity 92, e1. doi:10.15184/aqy.2018.221

Kuhn, S. L., Stiner, M. C., Reese, D. S., and Güleç, E. (2001). Ornaments of the Earliest Upper Paleolithic: New Insights from the Levant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98, 7641–7646. doi:10.1073/pnas.121590798

Langley, M. C., Amano, N., Wedage, O., Deraniyagala, S., Pathmalal, M. M., Perera, , et al. (2020). Bows and Arrows and Complex Symbolic Displays 48,000 Years Ago in the South Asian Tropics. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba3831. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aba3831

Langley, M. C., Balme, J., and O'Connor, S. (2021). Bone Artifacts from Riwi Cave, South‐central Kimberley: Reappraisal of the Timing and Role of Osseous Artifacts in Northern Australia. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol 31, 673–682. doi:10.1002/oa.2981

Langley, M. C., Clarkson, C., and Ulm, S. (2019). Symbolic Expression in Pleistocene Sahul, Sunda, and Wallacea. Quat. Sci. Rev. 221, 105883. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.105883

Langley, M. C., O'Connor, S., and Aplin, K. (2016a). A >46,000-Year-Old Kangaroo Bone Implement from Carpenter's Gap 1 (Kimberley, Northwest Australia). Quat. Sci. Rev. 154, 199–213. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.11.006

Langley, M. C., O'Connor, S., and Piotto, E. (2016b). 42,000-Year-Old Worked and Pigment-Stained Nautilus Shell from Jerimalai (Timor-Leste): Evidence for an Early Coastal Adaptation in ISEA. J. Hum. Evol. 97, 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.04.005

Lemorini, C., Bishop, L. C., Plummer, T. W., Braun, D. R., Ditchfield, P. W., and Oliver, J. S. (2019). Old Stones' Song-Second Verse: Use-Wear Analysis of Rhyolite and Fenetized Andesite Artifacts from the Oldowan Lithic Industry of Kanjera South, Kenya. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 11, 4729–4754. doi:10.1007/s12520-019-00800-z

Lemorini, C., Plummer, T. W., Braun, D. R., Crittenden, A. N., Ditchfield, P. W., Bishop, L. C., et al. (2014). Old Stones' Song: Use-Wear Experiments and Analysis of the Oldowan Quartz and Quartzite Assemblage from Kanjera South (Kenya). J. Hum. Evol. 72, 10–25. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.03.002

Lewis, J. E., and Harmand, S. (2016). An Earlier Origin for Stone Tool Making: Implications for Cognitive Evolution and the Transition to Homo. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20150233. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0233

Li, C., Yu, J., and Feng, X. (2000). 北京市王府井东方广场旧石器时代遗址发掘简报 (A Brief Report on the Excavation of the Paleolithic Sites at Dongfang Square in Wangfujing, Beijing). 考古 (Archaeology), 781–788. (in Chinese).

Li, C. (2004). ““The Artifacts from the Longgudong Cave in 1999--2000,” in Jianshi Hominid Site (In Chinese with English Summary). Editor S. Zheng (Beijing: Science Press), 37–60.

Li, Y. (1982). On the Relative Age of the Paleolithic in South China. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 1, 160–168. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Li, Z.-Y., Wu, X.-J., Zhou, L.-P., Liu, W., Gao, X., Nian, X.-M., et al. (2017). Late Pleistocene Archaic Human Crania from Xuchang, China. Science 355, 969–972. doi:10.1126/science.aal2482

Li, Z., Doyon, L., Fang, H., Ledevin, R., Queffelec, A., Raguin, E., et al. (2020). A Paleolithic Bird Figurine from the Lingjing Site, Henan, China. PLoS ONE 15, e0233370. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233370

Li, Z., Doyon, L., Li, H., Wang, Q., Zhang, Z., Zhao, Q., et al. (2019). Engraved Bones from the Archaic Hominin Site of Lingjing, Henan Province. Antiquity 93, 886–900. doi:10.15184/aqy.2019.81

Li, Z., and Shen, C. (2011). Excavation Report of the Lingjing Paleolithic Site in 2006. Chin. Archaeol 11, 65–73. (in Chinese).

Li, Z., and Shen, C. (2010). Use-Wear Analysis Confirms the Use of Palaeolithic Bone Tools by the Lingjing Xuchang Early Human. Chin. Sci. Bull. 55, 2282–2289. doi:10.1007/s11434-010-3089-4

Liaoning Provincial Museum, and Benxi Municipal Museum (1986). 庙后山——辽宁省本溪市旧石器文化遗址 (Miaohoushan - A Paleolithic Site in Benxi City, Liaoning Province). Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House. (in Chinese).

Yunnan Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology Liu, J. (2016). 云南江川甘棠箐旧石器遗址发掘获重大发现 (Significant Discoveries from the Excavation of the Gantangqing Paleolithic Site in Jiangchuan, Yunnan). 中国文物报 (China Cultural Relics News) 005, 1–3. (in Chinese).

Liu, W., Jin, C.-Z., Zhang, Y.-Q., Cai, Y.-J., Xing, S., Wu, X.-J., et al. (2010). Human Remains from Zhirendong, South China, and Modern Human Emergence in East Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 19201–19206. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014386107

Liu, W., Martinón-Torres, M., Cai, Y.-j., Xing, S., Tong, H.-w., Pei, S.-w., et al. (2015). The Earliest Unequivocally Modern Humans in Southern China. Nature 526, 696–699. doi:10.1038/nature15696

Lotus Cave Science MuseumBeijing Museum of Natural HistoryGuangxi Wenwu Gongzuodui (1987). Archaeological Finds in the Bailian Cave Site of Stone Age. South. Ethnol. Archaeol., 143–160. (in Chinese).

Lu, Qinyi. (1990). 和县猿人的发现和研究 (Discovery and Research of Hexian Ape Man). J. Anhui Univ. 2, 83–96. (in Chinese).

Madsen, D. B., Jingzen, L., Brantingham, P. J., Xing, G., Elston, R. G., and Bettinger, R. L. (2001). Dating Shuidonggou and the Upper Palaeolithic Blade Industry in North China. Antiquity 75, 706–716. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00089213

Mallye, J.-B., Thiébaut, C., Mourre, V., Costamagno, S., Claud, É., and Weisbecker, P. (2012). The Mousterian Bone Retouchers of Noisetier Cave: Experimentation and Identification of Marks. J. Archaeological Sci. 39, 1131–1142. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.12.018

Mania, D., and Mania, U. (2003). “Bilzingsleben - Homo Erectus, His Culture and His Environment. The Most Important Results of Research,” in Lower Palaeolithic Small Tools in Europe and the Levant. Editors J. M. Burdukiewicz, and A. Ronen (Oxford, England: British Archaeological Reports), 29–48.

Mania, D., and Mania, U. (1988). Deliberate Engravings on Bone Artefacts of Homo Erectus. Rock Art Res. 5, 91–95.

Mao, X., Zhang, H., Qiao, S., Liu, Y., Chang, F., Xie, P., et al. (2021). The Deep Population History of Northern East Asia from the Late Pleistocene to the Holocene. Cell 184, 3256–3266.e13. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.040

Mao, Y., and Cao, Z. (2012). A Preliminary Study of the Polished Bone Tools Unearthed in 1979 from the Chuandong Site in Puding County, Guizhou. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 31, 335–343. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Martellotta, E. F., Delpiano, D., Govoni, M., Nannini, N., Duches, R., and Peresani, M. (2020). The Use of Bone Retouchers in a Mousterian Context of Discoid Lithic Technology. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 12, 228. doi:10.1007/s12520-020-01155-6

Martinón-Torres, M., Cai, Y., Tong, H., Pei, S., Xing, S., Bermúdez de Castro, J. M., et al. (2021). On the Misidentification and Unreliable Context of the New “Human Teeth” from Fuyan Cave (China). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2102961118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2102961118

Martinón-Torres, M., Wu, X., Bermúdez de Castro, J. M., Xing, S., and Liu, W. (2017). Homo sapiens in the Eastern Asian Late Pleistocene. Curr. Anthropol. 58, S434–S448. doi:10.1086/694449

Massilani, D., Skov, L., Hajdinjak, M., Gunchinsuren, B., Tseveendorj, D., Yi, S., et al. (2020). Denisovan Ancestry and Population History of Early East Asians. Science 370, 579–583. doi:10.1126/science.abc1166

Mateo-Lomba, P., Fernández-Marchena, J. L., Ollé, A., and Cáceres, I. (2020). Knapped Bones Used as Tools: Experimental Approach on Different Activities. Quat. Int. 569-570, 51–65. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.04.033

McAdam, L. E. (2008). Beads across Australia: An Ethnographic and Archaeological View of the Patterning of Aboriginal Ornaments. [Ph.D. thesis]. Armidale: University of New England.

Miller-Antonio, S., Schepartz, L. A., and Bakken, D. (2000). Raw Material Selection and Evidence for Rhinoceros Tooth Tools at Dadong Cave, Southern China. Antiquity 74, 372–379. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00059457

Moigne, A.-M., Valensi, P., Auguste, P., García-Solano, J., Tuffreau, A., Lamotte, A., et al. (2016). Bone retouchers from Lower Palaeolithic sites: Terra Amata, Orgnac 3, Cagny-l'Epinette and Cueva del Angel. Quat. Int. 409, 195–212. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.06.059

Moncel, M.-H., Moigne, A.-M., and Combier, J. (2012). Towards the Middle Palaeolithic in Western Europe: the Case of Orgnac 3 (Southeastern France). J. Hum. Evol. 63, 653–666. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.08.001

Naldini, E. S., Muttoni, G., Parenti, F., Scardia, G., and Segre, A. G. (2009). Nouvelles recherches dans le bassin Plio-Pléistocène d'Anagni (Latium méridional, Italie). L'Anthropologie 113, 66–77. doi:10.1016/j.anthro.2009.01.013

O'Connor, S., Robertson, G., and Aplin, K. P. (2014). Are Osseous Artefacts a Window to Perishable Material Culture? Implications of an Unusually Complex Bone Tool from the Late Pleistocene of East Timor. J. Hum. Evol. 67, 108–119. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.12.002

Pante, M., Torre, I. d. l., d’Errico, F., Njau, J., and Blumenschine, R. (2020). Bone Tools from Beds II-IV, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, and Implications for the Origins and Evolution of Bone Technology. J. Hum. Evol. 148, 102885. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2020.102885

Perera, N., Roberts, P., Petraglia, M., and Langley, M. C. (2016). “Bone Technology from Late Pleistocene Caves and Rockshelters of Sri Lanka,” in Osseous Projectile Weaponry. Editor M. C. Langley (Dordrecht: Springer), 173–188. doi:10.1007/978-94-024-0899-7_12

Qu, T., Bar-Yosef, O., Wang, Y., and Wu, X. (2013). The Chinese Upper Paleolithic: Geography, Chronology, and Techno-Typology. J. Archaeol. Res. 21, 1–73. doi:10.1007/s10814-012-9059-4

Rabett, R. J., and Piper, P. J. (2012). The Emergence of Bone Technologies at the End of the Pleistocene in Southeast Asia: Regional and Evolutionary Implications. Caj 22, 37–56. doi:10.1017/S0959774312000030

Rabinovich, R., Ackermann, O., Aladjem, E., Barkai, R., Biton, R., Milevski, I., et al. (2012). Elephants at the Middle Pleistocene Acheulian Open-Air Site of Revadim Quarry, Israel. Quat. Int. 276-277, 183–197. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2012.05.009

Rigaud, S., d'Errico, F., and Vanhaeren, M. (2015). Ornaments Reveal Resistance of North European Cultures to the Spread of Farming. PLoS ONE 10, e0121166. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121166

Rigaud, S., Manen, C., and García-Martínez de Lagrán, I. (2018). Symbols in Motion: Flexible Cultural Boundaries and the Fast Spread of the Neolithic in the Western Mediterranean. PLoS ONE 13, e0196488. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0196488

Rosell, J., Blasco, R., Campeny, G., Díez, J. C., Alcalde, R. A., Menéndez, L., et al. (2011). Bone as a Technological Raw Material at the Gran Dolina Site (Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain). J. Hum. Evol. 61, 125–131. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.02.001

Sano, K., Arrighi, S., Stani, C., Aureli, D., Boschin, F., Fiore, I., et al. (2019). The Earliest Evidence for Mechanically Delivered Projectile Weapons in Europe. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1409–1414. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0990-3

Sano, K., Beyene, Y., Katoh, S., Koyabu, D., Endo, H., Sasaki, T., et al. (2020). A 1.4-Million-Year-Old Bone Handaxe from Konso, Ethiopia, Shows Advanced Tool Technology in the Early Acheulean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 18393–18400. doi:10.1073/pnas.2006370117

Santucci, E., Marano, F., Cerilli, E., Fiore, I., Lemorini, C., Palombo, M. R., et al. (2016). Palaeoloxodon Exploitation at the Middle Pleistocene Site of La Polledrara di Cecanibbio (Rome, Italy). Quat. Int. 406, 169–182. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.08.042

School of History Beijing Normal University (2017). Luoyang Municipal Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, and Commission for Preservation of Ancient Monuments, Luanchuan CountyThe Excavation of the Longquan Cave Site in Luanchuan, Henan in 2011). Acta Archaeol. Sinica, 227–248. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Sehasseh, E. M., Fernandez, P., Kuhn, S., Stiner, M., Mentzer, S., Colarossi, D., et al. (2021). Early Middle Stone Age Personal Ornaments from Bizmoune Cave, Essaouira, Morocco. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi8620. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abi8620

Shang, H., Tong, H., Zhang, S., Chen, F., and Trinkaus, E. (2007). An Early Modern Human from Tianyuan Cave, Zhoukoudian, China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104, 6573–6578. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702169104

Shen, G., Wu, X., Wang, Q., Tu, H., Feng, Y.-x., and Zhao, J.-x. (2013). Mass Spectrometric U-Series Dating of Huanglong Cave in Hubei Province, Central China: Evidence for Early Presence of Modern Humans in Eastern Asia. J. Hum. Evol. 65, 162–167. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.05.002

Shipman, P., and Rose, J. (1983). Early Hominid Hunting, Butchering, and Carcass-Processing Behaviors: Approaches to the Fossil Record. J. Anthropological Archaeology 2, 57–98. doi:10.1016/0278-4165(83)90008-9

Shunkov, M. V., Fedorchenko, A. Y., Kozlikin, M. B., and Derevianko, A. P. (2020). Initial Upper Palaeolithic Ornaments and Formal Bone Tools from the East Chamber of Denisova Cave in the Russian Altai. Quat. Int. 559, 47–67. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.07.027

Sirakov, N., Guadelli, J.-L., Ivanova, S., Sirakova, S., Boudadi-Maligne, M., Dimitrova, I., et al. (2010). An Ancient Continuous Human Presence in the Balkans and the Beginnings of Human Settlement in Western Eurasia: A Lower Pleistocene Example of the Lower Palaeolithic Levels in Kozarnika Cave (North-Western Bulgaria). Quat. Int. 223-224, 94–106. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2010.02.023

Smith, G. M. (2013). Taphonomic Resolution and Hominin Subsistence Behaviour in the Lower Palaeolithic: Differing Data Scales and Interpretive Frameworks at Boxgrove and Swanscombe (UK). J. Archaeological Sci. 40, 3754–3767. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.05.002

Song, Y., Cohen, D. J., Shi, J., Wu, X., Kvavadze, E., Goldberg, P., et al. (2017). Environmental Reconstruction and Dating of Shizitan 29, Shanxi Province: An Early Microblade Site in North China. J. Archaeological Sci. 79, 19–35. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2017.01.007

Song, Y., Grimaldi, S., Santaniello, F., Cohen, D. J., Shi, J., and Bar-Yosef, O. (2019). Re-Thinking the Evolution of Microblade Technology in East Asia: Techno-Functional Understanding of the Lithic Assemblage from Shizitan 29 (Shanxi, China). PLOS ONE 14, e0212643. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0212643

Song, Y., Li, X., Wu, X., Kvavadze, E., Goldberg, P., and Bar-Yosef, O. (2016). Bone Needle Fragment in LGM from the Shizitan Site (China): Archaeological Evidence and Experimental Study. Quat. Int. 400, 140–148. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.06.051

Soressi, M., McPherron, S. P., Lenoir, M., Dogandzic, T., Goldberg, P., Jacobs, Z., et al. (2013). Neandertals Made the First Specialized Bone Tools in Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 14186–14190. doi:10.1073/pnas.1302730110

Stammers, R. C., Caruana, M. V., and Herries, A. I. R. (2018). The First Bone Tools from Kromdraai and Stone Tools from Drimolen, and the Place of Bone Tools in the South African Earlier Stone Age. Quat. Int. 495, 87–101. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2018.04.026

Sun, J., Wang, Y., and Jiang, P. (1981). A Paleolithic Site at Zhoujiayoufang in Yushu County, Jilin Province. Vert. PalAsiat 19, 281–291. (in Chinese).

Sun, X.-f., Wen, S.-q., Lu, C.-q., Zhou, B.-y., Curnoe, D., Lu, H.-y., et al. (2021). Ancient DNA and Multimethod Dating Confirm the Late Arrival of Anatomically Modern Humans in Southern China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2019158118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2019158118

Tao, F., and Wang, X. (1987). 丁村遗址打制骨片的观察 (Observation on Bone Implements Found at the Dingcun Site). 史前研究 (Prehistoric Studies) 1, 10–12. (in Chinese).

Tartar, E. (2012). The Recognition of a New Type of Bone Tools in Early Aurignacian Assemblages: Implications for Understanding the Appearance of Osseous Technology in Europe. J. Archaeological Sci. 39, 2348–2360. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.02.003

Tejero, J.-M., Belfer-Cohen, A., Bar-Yosef, O., Gutkin, V., and Rabinovich, R. (2018). Symbolic Emblems of the Levantine Aurignacians as a Regional Entity Identifier (Hayonim Cave, Lower Galilee, Israel). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 5145–5150. doi:10.1073/pnas.1717145115

Tejero, J.-M., Rabinovich, R., Yeshurun, R., Abulafia, T., Bar-Yosef, O., Barzilai, O., et al. (2020). Personal Ornaments from Hayonim and Manot Caves (Israel) Hint at Symbolic Ties between the Levantine and the European Aurignacian. J. Hum. Evol., 102870. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2020.102870

Tejero, J.-M., Yeshurun, R., Barzilai, O., Goder-Goldberger, M., Hershkovitz, I., Lavi, R., et al. (2016). The Osseous Industry from Manot Cave (Western Galilee, Israel): Technical and Conceptual Behaviours of Bone and Antler Exploitation in the Levantine Aurignacian. Quat. Int. 403, 90–106. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.028

Val, A., Porraz, G., Texier, P.-J., Fisher, J. W., and Parkington, J. (2020). Human Exploitation of Nocturnal Felines at Diepkloof Rock Shelter Provides Further Evidence for Symbolic Behaviours during the Middle Stone Age. Sci. Rep. 10, 6424. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-63250-x

Val, A., and Stratford, D. J. (2015). The Macrovertebrate Fossil Assemblage from the Name Chamber, Sterkfontein: Taxonomy, Taphonomy and Implications for Site Formation Processes. Palaeontol. Africana 50, 1–17.

van Kolfschoten, T., Li, Z., Wang, H., and Doyon, L. (2020). ““The Middle Palaeolithic Site of Lingjing (Xuchang, Henan, China): Preliminary New Results,” in A Human Environment,” in Studies in Honour of 20 Years Analecta Editorship by Prof. Dr. Corrie Bakels. Editors V. Klinkenberg, R. van Oosten, and C. van Driel-Murray (Leiden: Sidestone Press), 21–28.

Vanhaeren, M., and d'Errico, F. (2006). Aurignacian Ethno-Linguistic Geography of Europe Revealed by Personal Ornaments. J. Archaeological Sci. 33, 1105–1128. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2005.11.017

Vanhaeren, M., d'Errico, F., Stringer, C., James, S. L., Todd, J. A., and Mienis, H. K. (2006). Middle Paleolithic Shell Beads in Israel and Algeria. Science 312, 1785–1788. doi:10.1126/science.1128139

Vanhaeren, M., Wadley, L., and d'Errico, F. (2019). Variability in Middle Stone Age Symbolic Traditions: The Marine Shell Beads from Sibudu Cave, South Africa. J. Archaeological Sci. Rep. 27, 101893. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.101893

Velliky, E. C., Schmidt, P., Bellot-Gurlet, L., Wolf, S., and Conard, N. J. (2021). Early Anthropogenic Use of Hematite on Aurignacian Ivory Personal Ornaments from Hohle Fels and Vogelherd Caves, Germany. J. Hum. Evol. 150, 102900. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2020.102900

Verna, C., and d’Errico, F. (2011). The Earliest Evidence for the Use of Human Bone as a Tool. J. Hum. Evol. 60, 145–157. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.07.027

Villa, P., Boschian, G., Pollarolo, L., Saccà, D., Marra, F., Nomade, S., et al. (2021). Elephant Bones for the Middle Pleistocene Toolmaker. PLoS ONE 16, e0256090. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0256090

Wang, S., Guo, Z., and Zhang, L. (1988). Bone Artifacts from the Early Pleistocene of Nihewan, Hebei Province. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 7, 302–305. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Wang, W., Bae, C., and Xu, X. (2020). Chinese Prehistoric Eyed Bone Needles: a Review and Assessment. J. World Prehist. 33, 385–423. doi:10.1007/s10963-020-09144-2

Wei, G., He, C., Hu, Y., Yu, K., Chen, S., Pang, L., et al. (2017a). First Discovery of a Bone Handaxe in China. Quat. Int. 434, 121–128. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.12.022

Wei, Q. (1985). Paleoliths from the Lower Pleistocene of the Nihewan Beds in the Donggutuo Site. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 4, 289–300. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Wei, Y., d’Errico, F., Vanhaeren, M., Li, F., and Gao, X. (2016). An Early Instance of Upper Palaeolithic Personal Ornamentation from China: The Freshwater Shell Bead from Shuidonggou 2. PLOS ONE 11, e0155847. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155847

Wei, Y., d’Errico, F., Vanhaeren, M., Peng, F., Chen, F., and Gao, X. (2017b). A Technological and Morphological Study of Late Paleolithic Ostrich Eggshell Beads from Shuidonggou, North China. J. Archaeological Sci. 85, 83–104. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2017.07.003

Wu, X. (2004). On the Origin of Modern Humans in China. Quat. Int. 117, 131–140. doi:10.1016/S1040-6182(03)00123-X

Wu, Z., and Chen, Z. (1989). 山西和顺背窑湾洞穴中的旧石器时代文化遗存 (The Paleolithic Cultural Relics in Beiyaowan Caves in Heshun, Shanxi). 史前研究 (Prehistoric Studies), 57–68. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Xie, F., Li, J., and Liu, L. (2006). The Paleolithic Archaeology in the Nihewan Basin. Shijiazhuang: Huashan Literature & Arts Press. (in Chinese).

Xie, J., and Zhang, L. (1977). 甘肃庆阳地区的旧石器 (Paleolithic Tools in Qingyang, Gansu). Vert. Palasiat. 15, 211–222. (in Chinese).

Yang, M. A., Gao, X., Theunert, C., Tong, H., Aximu-Petri, A., Nickel, B., et al. (2017). 40,000-Year-Old Individual from Asia Provides Insight into Early Population Structure in Eurasia. Curr. Biol. 27, 3202–3208. e9. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.030

Yellen, J. E. (1998). Barbed Bone Points: Tradition and Continuity in Saharan and Sub-saharan Africa. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 15, 173–198. doi:10.1023/A:1021659928822

Yeshurun, R., Tejero, J.-M., Barzilai, O., Hershkovitz, I., and Ofer, M. (2018). “Upper Palaeolithic Bone Retouchers from Manot Cave (Israel): A Preliminary Analysis of a (Yet) Rare Phenomenon in the Levant,” in The Origins of Bone Tool Technologies. Editors J. M. Hutson, A. García-Moreno, E. S. Noack, E. Turner, A. Villaluenga, and S. Gaudzinski-Windheuser (Mainz: Römisch Germanisches ZentralMuseum), 287–295.

Yin, R., Luan, F., and Doyon, L. (2021). 西方骨器研究的理论与实践 (Theory and Practice for the Study of Bone Technology in the West). 东南文化 (Southeastern Culture) 282, 6–15. (in Chinese).

Yu, H. (1988). A Brief Study of Late Palaeolithic Localities at Xuetian Village of Wuchang County, Heilongjiang Province. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 7, 255–262. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Yuan, J. (2002). “Rice and Pottery 10,000 Yrs. BP at Yuchanyan, Dao County, Hunan Province,” in The Origins of Pottery and Agriculture. Editor Y. Yoshinori (New Delhi: Roli Books), 157–166.

Zhang, D., Xia, H., Chen, F., Li, B., Slon, V., Cheng, T., et al. (2020). Denisovan DNA in Late Pleistocene Sediments from Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan Plateau. Science 370, 584–587. doi:10.1126/science.abb6320

Zhang, J.-F., Huang, W.-W., Yuan, B.-Y., Fu, R.-Y., and Zhou, L.-P. (2010). Optically Stimulated Luminescence Dating of Cave Deposits at the Xiaogushan Prehistoric Site, Northeastern China. J. Hum. Evol. 59, 514–524. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.05.008

Zhang, J. (1991). A Study of the Bone Fragments of Shiyu Site. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 10, 333–345. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Zhang, L.-m., Griggo, C., Dong, W., Hou, Y.-m., Zhang, S.-q., Yang, Z.-m., et al. (2016). Preliminary Taphonomic Analyses on the Mammalian Remains from Wulanmulun Paleolithic Site, Nei Mongol, China. Quat. Int. 400, 158–165. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.10.024

Zhang, S., d'Errico, F., Backwell, L. R., Zhang, Y., Chen, F., and Gao, X. (2016). Ma'anshan Cave and the Origin of Bone Tool Technology in China. J. Archaeological Sci. 65, 57–69. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2015.11.004

Zhang, S., Doyon, L., Zhang, Y., Gao, X., Chen, F., Guan, Y., et al. (2018). Innovation in Bone Technology and Artefact Types in the Late Upper Palaeolithic of China: Insights from Shuidonggou Locality 12. J. Archaeological Sci. 93, 82–93. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2018.03.003

Zhang, S., Jin, C., Wei, G., Xu, Q., Han, L., and Zheng, L. (2000). On the Artifacts Unearthed from the Renzidong Paleolithic Site in 1998. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 19, 169–183. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Zhang, S., and Liu, Y. (2003). Report on the Excavation of Zhijidong Cave Site. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 22, 1–17. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Zhang, S. (1989). Paleolithic Materials Found in Zhaocun Site, Qian'an, Hebei. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 8, 107–113. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Zhang, S., Peng, F., Zhang, Y., Guo, J., Wang, H., Huang, C., et al. (2019). Taphonomic Observation of the Faunal Remains from Locality 10 of the Gezishan Site, Ningxia, China. Acta Anthropol. Sinica 38, 232–244. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Zhang, S. (1965). 湖南桂阳发垠有刻纹的骨锥 (Carved Bone from Fayin, Guiyang, Hunan). Vert. Palasiat. 9, 236. (in Chinese).

Zhang, X., Gao, F., Ma, B., and Hou, L. (1989). 云南江川百万年前旧石器遗存的初步研究(A Preliminary Study on the 1-Million Years-Old Paleolithic Remains in Jiangchuan, Yunnan). 忍想战线. (Thinking), 51–55. (in Chinese).

Zhang, Y., Gao, X., Pei, S., Chen, F., Niu, D., Xu, X., et al. (2016). The Bone Needles from Shuidonggou Locality 12 and Implications for Human Subsistence Behaviors in North China. Quat. Int. 400, 149–157. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.06.041

Zhang, Y., Zhang, S., Gao, X., and Chen, F. (2019). The First Ground Tooth Artifact in Upper Palaeolithic China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 62, 403–411. doi:10.1007/s11430-018-9293-8

Zhou, G. (1994). “Re-Evaluation on Bailiandong Culture,” in The International Symposium on the Prehistoric Relationship between China and Japan. Editor G. Zhou (Beijing: China International Radio Press), 203–230. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Zhou, X., Sun, Y., Wang, Z., and Wang, H. (1990). 大连古龙山遗址研究 (Research at the Gulongshan Site in Dalian). Beijing: Beijing Science and Technology Press. (in Chinese).

Zhu, R., An, Z., Potts, R., and Hoffman, K. A. (2003). Magnetostratigraphic Dating of Early Humans in China. Earth-Science Rev. 61, 341–359. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00132-0

Zhu, Z.-Y., Dennell, R., Huang, W.-W., Wu, Y., Rao, Z.-G., Qiu, S.-F., et al. (2015). New Dating of the Homo Erectus Cranium from Lantian (Gongwangling), China. J. Hum. Evol. 78, 144–157. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.10.001

Keywords: Pleistocene, bone tools, cultural evolution, symbolism, archaic humans, Homo sapiens