95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Earth Sci. , 10 November 2021

Sec. Hydrosphere

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2021.757094

This article is part of the Research Topic Tracing Earth Surface Processes Using Novel Isotopic Approaches View all 10 articles

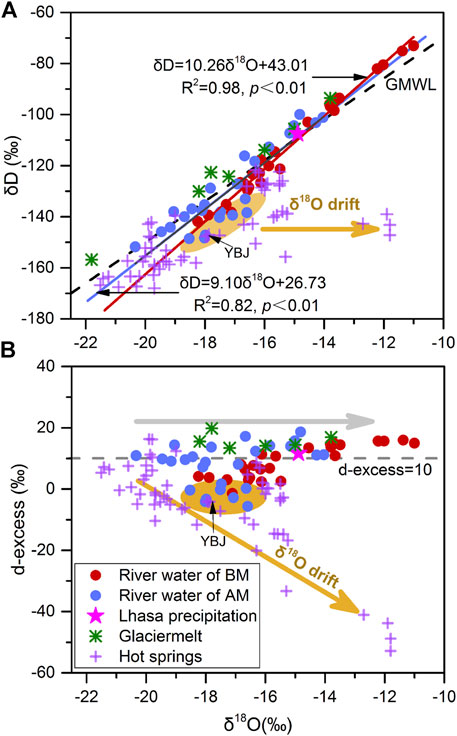

Characterization of spatiotemporal variation of the stable isotopes δ18O and δD in surface water is essential to trace the water cycle, indicate moisture sources, and reconstruct paleoaltimetry. In this study, river water, rainwater, and groundwater samples were collected in the Yarlung Tsangpo River (YTR) Basin before (BM) and after the monsoon precipitation (AM) to investigate the δ18O and δD spatiotemporal variation of natural water. Most of the river waters are distributed along GMWL and the line of d-excess = 10‰, indicating that they are mainly originated from precipitation. Temporally, the δ18O and δD of river water are higher in BM series (SWL: δD = 10.26δ18O+43.01, R2 = 0.98) than AM series (SWL: δD = 9.10δ18O + 26.73, R2 = 0.82). Spatially, the isotopic compositions of tributaries increase gradually from west to east (BM: δ18O = 0.65Lon (°)-73.89, R2 = 0.79; AM: δ18O = 0.45Lon (°)-57.81, R2 = 0.70) and from high altitude to low (BM: δ18O = −0.0025Alt(m)-73.89, R2 = 0.66; AM: δ18O = −0.0018Alt(m)-10.57, R2 = 0.58), which conforms to the “continent effect” and “altitude effect” of precipitation. In the lower reaches of the mainstream, rainwater is the main source, so the variations of δ18O and δD are normally elevated with the flow direction. Anomalously, in the middle reaches, the δ18Omainstream and δDmainstream values firstly increase and then decrease. From the Saga to Lhaze section, the higher positive values of δ18Omainstream are mainly caused by groundwater afflux, which has high δ18O and low d-excess values. The δ18Omainstream decrease from the Lhaze to Qushui section is attributed to the combined action of the import of depleted 18O and D groundwater and tributaries. Therefore, because of the recharge of groundwater with markedly different δ18O and δD values, the mainstream no longer simply inherits the isotopic composition from precipitation. These results suggest that in the YTR Basin, if the δ18O value of surface water is used to trace moisture sources or reconstruct the paleoaltimetry, it is necessary to rule out the influence from groundwater.

The stable isotopes, δ18O and δD, in precipitation are widely used as a fingerprint for the hydrological processes and atmospheric circulation (Fette et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2019). The Tibetan Plateau (TP) is the highest and widest high-altitude region on Earth, and the uplift history and terrain atmosphere of the region are of scientific interest (Garzione et al., 2000; Rowley et al., 2001; Spicer et al., 2003; Quade et al., 2011). Because of the so-called “continent effect” and “altitude effect” of isotope composition in precipitation (i.e., the negative relationship between Δδ18O or ΔδD in precipitation and transport distance and elevation) producing heavier monsoonal rainfall first with transported distance, and then with orographic lifting, stable isotopes have also been used to trace moisture sources and to reconstruct paleoelevation of the TP (Garzione et al., 2000; Poage and Chamberlain, 2001; Rowley et al., 2001; Hren et al., 2009; Li and Garzione, 2017). A global network for isotopes in precipitation (GNIP) has been established by the International Atomic Energy Agency to monitor the long-term changes in δ18O and δD in global precipitation. However, because of the few isotope-monitoring stations in the TP, the study of precipitation isotopic variability and hydrological processes in this region is usually hampered.

Based on the consideration that stream water can provide a time-integrated record of the isotopic composition of precipitation (Gat, 1996; Kendall and Coplen, 2001), a number of studies have used the isotopes in river water as a substitute for modern precipitation to further reconstruct paleoelevation or to trace moisture sources (Garzione et al., 2000; Hren et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2012a; Bershaw et al., 2012; Kong and Pang, 2016; Li and Garzione, 2017). At present, significant negative isotope–altitude relationships have been reported: for example, the lapse rate of δ18O in river water is about −0.21‰ per 100 m in the northeastern TP (Bershaw et al., 2012), −0.24‰ per 100 m in the southern TP (Ding et al., 2009), −0.28‰ per 100 m in the high Himalayas of Nepal and −0.31‰ per 100 m in the Niyang River watershed (Florea et al., 2017), while it is as low as −0.36‰ per 100 m in the southern Himalaya (Wen et al., 2012) and about −0.19‰ per 100 m in the Hengduan Mountains (Hoke et al., 2014).

The Yarlung Tsangpo River (YTR) Basin was thought to be influenced by two climatic systems: a monsoonal system in the east and a westerly system in the west (Tian et al., 2001a; Tian et al., 2007; Hren et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2016; Ren et al., 2016, 2018). Monsoon-derived precipitation was found to have low δ18O and d-excess (d-excess = δD-8δ18O) values (Dansgaard, 1964), and westerlies-derived precipitation had high values of both δ18O and d-excess values (Tian et al., 2001a; Tian et al., 2005; Tian et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2012b; Yu et al., 2016). Hren et al. (2009) reported that the westernmost monsoon influence reached almost to 86°E, recording a minimum δ18O value of approximately minus 20‰ for the YTR.

In addition to precipitation, groundwater recharge and ice/glacier melt water entering the YTR cannot be ignored as well (Liu, 1999; Liu et al., 2007; Tan et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). The contributions of these sources differ between different seasons and different locations: the groundwater contribution is 40% in Nugesha, 36% in Yangcun, 32% in Nuxia (Liu, 1999), and 27–40% in the middle reach (Tan et al., 2021). Furthermore, the distinctions of hydrochemical and isotopic composition between groundwater and precipitation are obvious in the YTR Basin (Tan et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2019). In the case of the YTR Basin, which is the largest river basin on the Tibetan Plateau, it is unclear as to the extent to which groundwater recharge and precipitation affect the spatiotemporal distribution of stable isotopes in the river water. Accordingly, this study documents the oxygen and hydrogen isotopic compositions in river water, rainfall, and groundwater in the YTR Basin. Spatially, major influences on the variability of the isotopic composition of river water along the channel are described and identified. Temporally, comparisons of the isotopic composition were conducted before and after monsoon precipitation. The anomalous spatial distribution of isotopic compositions of mainstream in the middle reach and its cause is revealed.

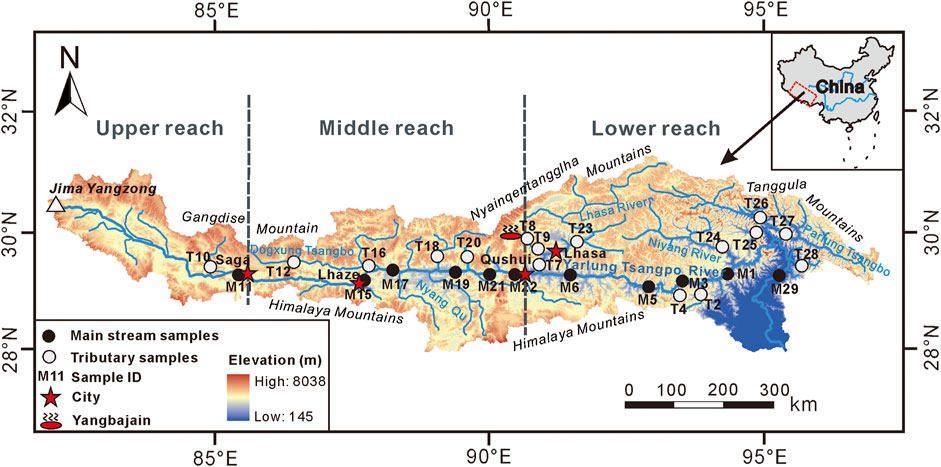

The YTR extends from the Jima Yangzong glacier above 5,200 m elevation to the Bay of Bengal and is the highest large river in the world located south of the TP (Huang et al., 2008). The YTR Basin is a long and narrow valley covering a total area of about 240,480 km2 in a west-east direction among the Gangdise, Nyainqentanglha, and Himalaya Mountains (Figure 1) (Liu et al., 2007). The elevation of the basin gradually decreases from west to east. The upper reach is from the source to Saga, with the major tributaries Mayou Tsangpo, Chai Qu, and Jiada Tsangpo; the middle reach is from Saga to Qushui, with major tributaries being Dogxung Tsangpo and Nyang Qu; and the lower reach is below Qushui with major tributaries being Lhasa River, Niyang River, and Parlung Tsangpo. In general, mean annual precipitation decreases from about 1,000 mm in the east of the basin to about 200 mm at the headwaters (Ren et al., 2018). Some 65–80% of the annual precipitation occurs between June and September, with the exception of southeastern Tibet (Liu, 1999). The mean annual air temperature in this area is about 5.9°C with an average seasonal variation of 2.46 and 13.49°C (You et al., 2007). The mean annual evaporation in this area is 1,052 mm, which is higher in the west than that in the east (Huang et al., 2011). The mean annual discharge of the YTR Basin is ∼1,395.4 × 108 m3 (Liu, 1999). In the upper and middle reach, groundwater is the main source; in the lower reach, the recharge pattern is a mix of rainwater and meltwater; while into the heavy rain area below the grand canyon, the river is mainly from precipitation (Liu, 1999; Yang et al., 2011).

FIGURE 1. Sampling sites in the YTR Basin (Modified from Zhang et al., 2021).

Geologically, TP is generally regarded as a product of the Eurasian and Indian Plates collision (Gansser, 1980). The tectonic units of the TP comprise a series of east–west-trending continental blocks, including Songpan–Ganzi, Qiangtang, Lhasa, the Tethyan Himalayas, the high Himalaya, and the lesser Himalayas (Tapponnier et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2015). Due to the east-west extension of the TP, rifts trending approximately north–south cut across the YTR Basin (Armijo et al., 1986), From west to east, these rifts are Dingri-Nima (DN), Dingjie-Xietongmen-Shenzha (DXS), Yadong-Dangxiong-Gulu (YDG), and Gudui-Sangri (GS) rifts. Thus, the YTR Basin has widely distributed springs along the rifts (Wang et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2021). The terrane in the southern TP is dominated by Paleozoic–Mesozoic carbonate and clastic sedimentary rocks (Galy and France-Lanord, 1999). The bedrock in the basin mainly consists of igneous granite/granitic gneiss, or schist/other felsic volcanic and mafic volcanic rock. However, there are few if any carbonate rocks are in the upper and middle reaches of the catchments (Hren et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2011). Along the entire river course, ophiolites and ophiolitic mélanges are commonly found (GMRT Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources of Xizang Tibet Autonomous Region, 1993).

Two systematic sampling series were carried out in the YTR Basin (Figure 1), one in June, 2017, prior to large-scale monsoon rainfall (“BM” series) and one in September, 2017, after large-scale monsoon rainfall (“AM” series). A total of 53 river water samples were collected, comprising 22 samples from the main stream and 31 samples from the large tributaries (e.g., Jiada Tsangpo, Dogxung Tsangpo, Lhasa River, Niyang River, Parlung Tsangpo, etc.). Some of the mainstream sampling sites were located at least 1 km downstream of the confluence of major tributaries to ensure that the water from all sources was fully mixed. The other mainstream samples were evenly distributed along the whole basin. The samples of the tributaries were collected before they merged with the main stream. In addition, a hot spring sample was collected from the Yangbajain (YBJ) geothermal field, central YTR Basin. The rainwater sample was from Lhasa.

River water samples were collected at a depth of 10–15 cm on the river bank. All samples were filtered through 0.45 μM cellulose membrane and then put the filtered samples into dry, clean 15 ml HDPE bottles. To prevent sample evaporation, the bottles were completely filled and immediately sealed with parafilm. Samples were frozen in a refrigerator in the laboratory and then thawed to room temperature when required for analysis. Stable δ18O and δD values of all samples were determined by Liquid Water Isotope Analyzer (IWA-35EP) in the State Key Laboratory of Environmental Geochemistry, Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The precision of δ18O and δD measurements was better than ±0.1‰ and ±1.0‰, respectively. Results were reported as relative to the standard V-SMOW (Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water).

The δ18O and δD values for river water, groundwater, and rainwater in the YTR Basin are listed in Table 1. The δ18O and δD values of river water range from −20.3 to −11.0‰ (arithmetic mean −16.1‰) and from −152 to −73‰ (arithmetic mean −121‰), similar to those of Hren et al. (2009) (δ18O: −20.8−9.8‰, δD: −165−59‰) and Ren et al. (2018) (δ18O: −18.7−11.9‰, δD: −146−86‰).

In the BM series, the mean δ18O and δD values for river water were −16.1 and −111‰, respectively. In the AM series, the mean δ18O and δD values were −17.2 and −130‰, respectively. For each sampling point, the δ18O and δD of BM series were higher than those for the AM series, except for the Duilong Qu tributary (T8) sample, which was omitted in September. The results show that the river water is richer in heavy H and O isotopes before monsoon precipitation than after. The variation amplitude of stable isotopic composition in the upper and middle reach is less than that in lower reach. The sample with maximum amplitude variation of δ18O and δD values between two series is from Motuo (M29) (−4.4 and −37‰, respectively); the sample with the minimum variation is from Saga (M11) (−0.7 and −13‰, respectively).

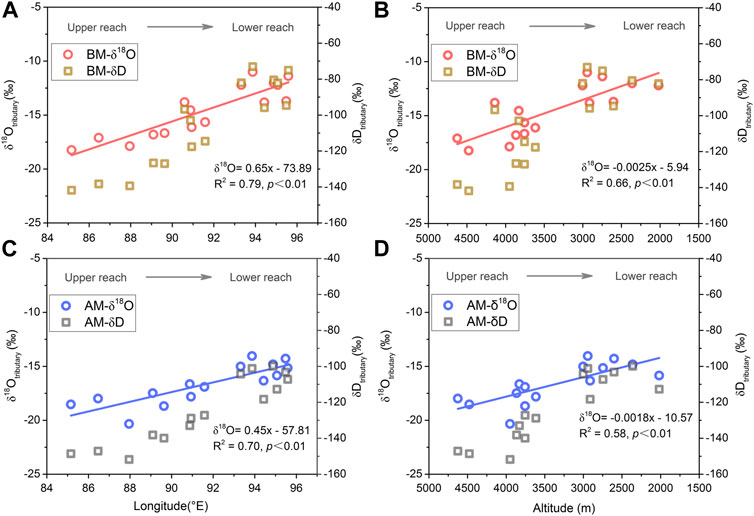

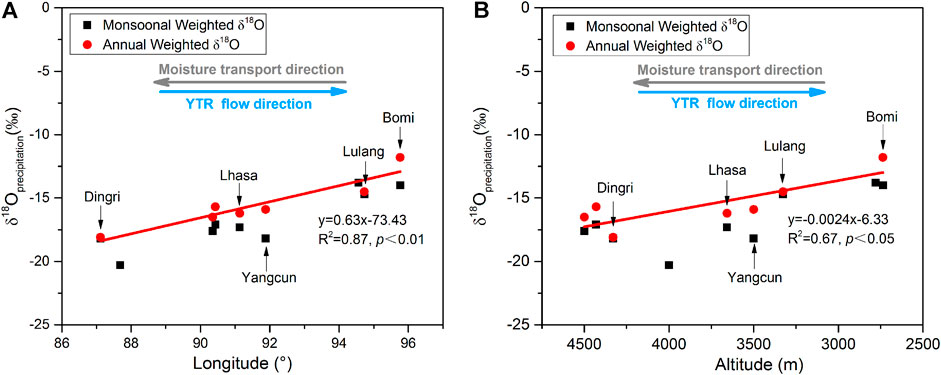

Overall, δ18O and δD values of tributary water (δ18Otributary and δDtributary) increased gradually from upper to lower reach in the YTR Basin no matter in BM series or AM series (Figure 2). Since the YTR flows approximately from west to east, longitude was adopted as a convenient proxy for downstream distance of the main channel. The relationships between the δ18Otributary and the longitude are δ18O (‰) = 0.65 Lon(°E)-73.89 (R2 = 0.79, p < 0.01) before monsoon precipitation and δ18O (‰) = 0.45 Lon(°E)-57.81 (R2 = 0.70, p < 0.01) after monsoon precipitation, respectively. In addition, the relationships between the δ18Otributary and altitude are δ18O (‰) = −0.0025 Alt(m)-5.94 (R2 = 0.66, p < 0.01) before monsoon precipitation and δ18O (‰) = −0.0018 Alt(m)-10.57 (R2 = 0.58, p < 0.01) after monsoon precipitation.

FIGURE 2. Tributary water spatial variation of δ18O and δD with longitude (A,C) and altitude (B,D). Red circles and brown squares represent δ18O and δD values before monsoon precipitation (BM) in (A,B), respectively. Blue circles and gray squares represent δ18O and δD values after monsoon precipitation (AM) in (C,D). Red lines and blue lines show the linear fitting relationships between δ18O in tributary water with longitude and altitude BM and AM, respectively.

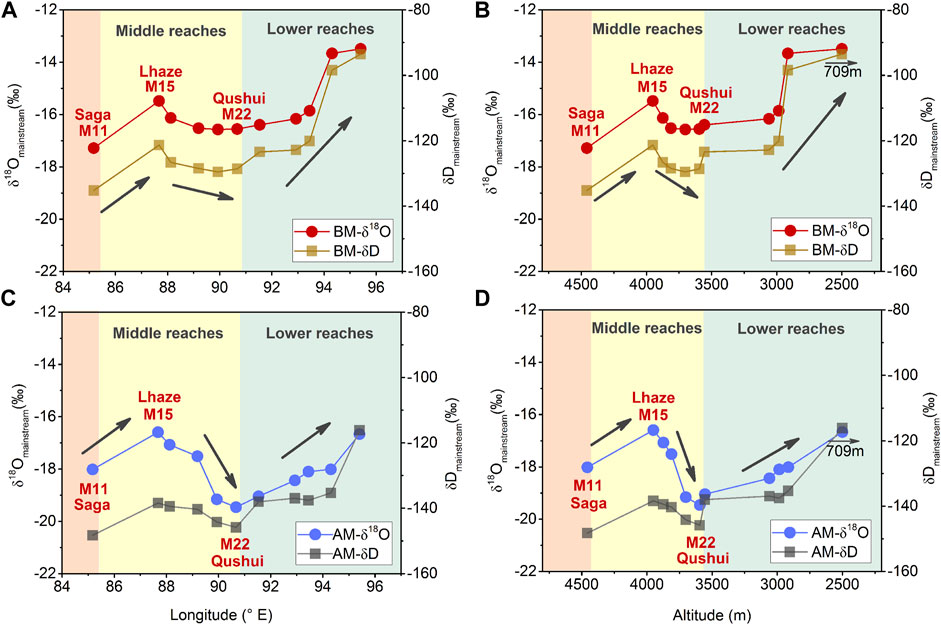

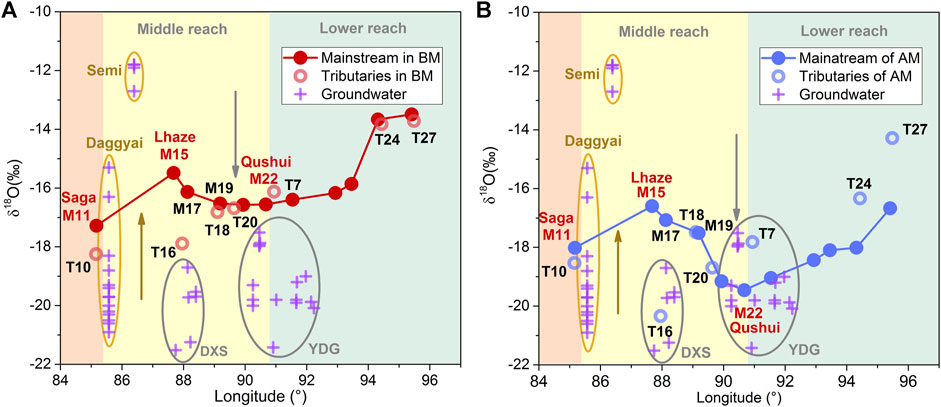

In the flow direction, δ18O and δD isotopic values of mainstream waters (δ18Omainstream and δDmainstream) increased from the upper reaches to the Lhaze (M15) section, then declined gradually from the Lhaze to Qushui (M22) section in the middle reaches, and then rose sharply again in the lower reaches (Figure 3). In both the BM and AM series, δ18Omainstream and δDmainstream showed the same spatial variation tendency. It is notable that the trends of δ18Omainstream and δDmainstream were significantly different from those in the tributaries, especially in the middle reach (Figure 2).

FIGURE 3. Mainstream water spatial variation of δ18O and δD values of characteristics with longitude (A,C) and altitude (B,D). Red circles and brown squares represent δ18O and δD values before monsoon precipitation (BM) in (A,B), respectively. Blue circles and gray squares represent δ18O and δD values of mainstream water after monsoon precipitation (BM) in (C,D). In the upper part of the middle reach, δ18O shows abnormally high values.

The correlation between natural water H and O isotopic compositions is usually used to identify the recharge source, circulation paths, and mixing or exchange processes (Tan et al., 2014; Ren et al., 2018). In general, δ18O and δD in meteoric water on a global scale have been found to fall close to the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL) of δD = 8δ18O+10 (Craig, 1961). In the YTR Basin, the Local Meteoric Water Lines (LMWLs) for several sites have been reported as δD = 7.9δ18O + 4.3 (R2 = 0.98) for Bomi (Gao et al., 2011), δD = 7.9δ18O + 6.3 for Lhasa (Tian et al., 2001b), and δD = 7.2δ18O−15.8 for Xigaze (Ren et al., 2017a), but the exact LMWL for the entire basin is yet to be determined. The indicator, deuterium excess (d-excess = δD–8δ18O), was defined as a measure of non-equilibrium isotopes effects (Dansgaard, 1964) to record the difference between the actual δD and the expected equilibrium values based on measured δ18O. The d-excess of global meteoric water is +10‰. In the low-humidity conditions, strong kinetic fractionation in evaporation causes high d-excess value (>10‰) in precipitation. Conversely, high-humidity results in a decrease in kinetic isotope fractionation, and subsequent precipitation will have a low d-excess value (<10‰) (Gat and Matsui, 1991; Gat, 1996). For the geothermal water systems, δ18O values of rocks and minerals are greater than those for water in general, and the O isotope exchange during the water-rock interaction increases δ18O in water. However, since few rock minerals contain H and the δD value is low, the isotope exchange reaction has little effect on the δD of water. As a result, the isotopic composition of the groundwater is shifted horizontally to the right on the δD vs δ18O diagram (Figure 4A) when the water residence time is long enough and the water-rock interaction is significant, a phenomenon known as “δ18O drift” (Wang, 1991). As a result, the isotopic exchange reaction also reduces the d-excess value of geothermal water (Wang, 1991; Yin et al., 2001).

FIGURE 4. δD vs δ18O values and d-excess vs δ18O values for natural water in the YTR Basin. The red dots and blue dots represent the δD vs δ18O values of river water sampled before the monsoon precipitation (BM series) and after the monsoon precipitation (AM series), respectively. The red line and blue line show the linear fitting relationships between δD and δ18O values of BM series and AM series river water, respectively. The black dashed line in (A) is the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL, δD = 8δ18O+10) (Craig, 1961). The gray dashed line in (B) is d-excess = 10‰. The brown arrow shows the downward trend of δ18O drift in the groundwater; the gray arrow shows the distribution trend of global meteoric water. The δD and δ18O values of glacier melt and groundwater are from Ren et al. (2017b), Tan et al. (2014), Tan et al. (2021), and Liu et al. (2019), respectively.

In this study, most of the δ18O and δD values of river waters in the YTR Basin are distributed along GMWL and the line of d-excess = 10‰, which indicates that river waters should be mainly originated from precipitation. The linear regression relationships between δ18O and δD values and surface water lines (SWLs) are δD = 10.26δ18O + 43.01 (R2 = 0.98, n = 27, p < 0.01) before the monsoon precipitation and δD = 9.10δ18O + 26.73 (R2 = 0.82, n = 26, p < 0.01) after the monsoon precipitation. Both the slopes and intercepts are larger than GMWL and LMWLs. The SWLs are approximate to previous studies of Hren et al. (2009) (slope≈10 and intercept≈38) and Ren et al. (2018) (slope 9.25 and intercept 24.1) in the basin. Evaporation is not the cause of steep slopes because that it would result in more isotopical enrichment and a lower δD-δ18O slope in residual waters than GMWL (Gonfiantini 1986; Ren et al., 2018). Glacier melt is also a vital source of river water, and the points of glacier melt distributed along the GMWL inherit the isotopic composition of precipitation (Figure 4A). Therefore, the steep slopes of SWLs cannot be attributed to the supply of glacier melt. As shown in Figure 4A, there are a few samples (mainly from the upper and middle stream) fall on the lower left-hand side of the GMWL with low d-excess (Figure 4B), which could produce a steep δD-δ18O slope. Meanwhile, the samples show greater deviation more from the GMWL, indicating that they may be supplied by another source with higher δ18O and d-excess than precipitation.

In addition to precipitation and glacier melt water, groundwater may also be non-negligible sources of YTR water (Liu, 1999; Liu et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2021). A few studies have reported the stable isotope composition of groundwater in the YTR Basin (Figure 4) (Tan et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2021). Based on their δ18O and δD values, groundwater can be roughly divided into two categories. Some dots with lower lighter-isotope composition are located in the lower left-hand corner of the δD-δ18O diagram (Figure 4A). The research of Tan et al. (2021) suggested that the groundwater with lower values of δ18O and δD in the Xietongmen to Lhasa section of the YTR Basin originated from paleo-precipitation during a cooler time. A supply of such groundwater would lower the δ18O and δD values in the river water, but the slope of the SWL would not be affected; however, other groundwater samples (including YBJ) have shown a significant positive deviation of δ18O from GMWL and a negative deviation of d-excess from 10‰ (Figure 4B). According to the study of Liu et al. (2019), some hot springs in the Semi and Daggyai geothermal fields have significant “δ18O drift” due to the mixing of magmatic fluids with higher δ18O values. A similar property of groundwater has been observed in other tectonic fracture zones or thermal field distribution areas (e.g., at the edge of the Guanzhong Basin, China (Ma et al., 2017), in the southeastern edge of the Eurasia (Chen et al., 2016), in Kyushu, Japan (Mizutani, 1972), and in northern Iceland (Stefánsson et al., 2019)). Consequently, from the perspective of isotopic composition characteristics, these river samples deviating from GMWL to the right and the downward trend of the d-excess = 10‰ line to the downward may be due to the recharge from a particular type of groundwater with significant δ18O drift.

As shown in Figure 4A, the YTR waters have high δD and δ18O values before the monsoon precipitation and low values after the monsoon precipitation. As discussed in δD–δ18O Relationship, YTR waters mainly originate from precipitation and inherit its isotopic composition of precipitation. The temporal pattern of isotopic composition in the YTR Basin river waters is dominated by precipitation.

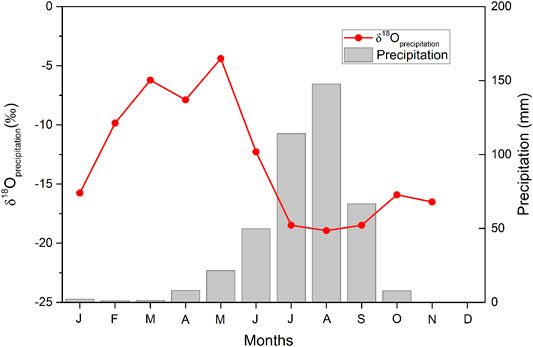

The precipitation in the YTR Basin has a remarkable seasonal pattern. Summer precipitation contributes up to 65–80% of the annual total in this region, and it is dominated by the monsoon from the Bay of Bengal (Liu, 1999). Previous work revealed that the temporal variation of δ18O in precipitation (δ18Oprecipitation) was characterized by a higher value in the dry season (October to May of the following year) and lower in the monsoon season (from mid-June to September). This is known as the “amount effect” of δ18Oprecipitation, as in the observational data from Lhasa station shown in Figure 5 (Wei and Lin., 1994; Tian et al., 1997; Tian et al., 2001a; Tian et al., 2001b; Liu et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2016; Hren et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2012b; Yao et al., 2013; Ren et al., 2018). As a whole, under the influence of rainfall, the δD and δ18O of the YTR Basin river waters are high before the monsoon precipitation and low afterward.

FIGURE 5. Monthly precipitation amounts and weighted-average δ18O of precipitation at Lhasa station (data are from Liu et al., 2007; Gao et al., 2011).

The δ18O amplitude variation of sample between two series (4.4‰, the maximum) is much small than annual variation of precipitation (∼14.5‰) in Lhasa. For one thing, the valley collects precipitation from an entire catchment over a period of time. For another, in addition to precipitation, the river may have other sources with stable isotopic composition, such as groundwater. So, the isotopic composition of river water is more stable than that of precipitation in different seasons. The variation amplitude of δ18O in the upper reach and middle reach is less than that in the lower reach. It could be attributed that precipitation contributes more to river in the lower reach than the upper or middle reach.

The δD and δ18O values in tributary waters (δDtributary and δ18Otributary) increase gradually from west to east with high to low topographical relief for both BM and AM series (Figure 2). The spatial distribution pattern is very similar to precipitation, which indicates that the δDtributary and δ18Otributary values are mainly affected by precipitation.

Spatially, the δ18Oprecipitation in the YTR Basin is influenced by the “continent effect” and “altitude effect” (Liu et al., 2007; Hren et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2000). During the summer period, moisture penetrates into the southeastern TP and is transported westward along the YTR valley, so longitude may be regarded as a convenient proxy for the transported distance of the moisture. Moreover, the terrain of the YTR valley gradually rises from east to west. As a warm and humid airmass moves westward, the moisture adiabatically cools and produces heavier monsoonal rainfall with increasing transport distance and altitude, resulting in a gradually lighter isotopic composition of precipitation (Liu et al., 2007; Hren et al., 2009). Therefore, the δ18O in the precipitation decreases gradually in an upstream direction along the YTR valley. As shown in Figure 6, the annual weighted δ18Oprecipitation value is significantly correlated with longitude and altitude. The δ18Oprecipitation vertical lapse rate −2.4‰/km (R2 = 0.67, p < 0.05) approximates to the global average of −2.8‰/km (Poage and Chamberlain, 2001).

FIGURE 6. Relationship of δ18O of precipitation to (A) longitude and (B) altitude. Red dots = annual weighted δ18O; black squares = monsoonal weighted δ18O of precipitation; red lines = linear fit of annual weighted δ18O in precipitation with longitude and altitude. As moisture moves westward, altitude gradually increases and isotopic compositions of precipitation progressively decrease (data from Wang et al. (2000) and Yao et al. (2013)).

The δDtributary and δ18Otributary show a similar spatial variation trend with precipitation (Figures 2, 6). It should be noted that the change rates of δ18Otributary value with regard to longitude and altitude (0.65‰ per longitude degree and −2.5‰/km) before the monsoon precipitation approximate more closely to annual weighted δ18O in precipitation (0.63‰ per longitude degree and −2.4‰ per 1 km) than after monsoon precipitation (0.44‰ per longitude degree and −1.8‰ per 1 km). The lower δ18O vertical lapse rate after the monsoon precipitation may be related to water sources mixed from different altitudes. During the monsoon precipitation in summer, the accumulated snows from different altitudes melt and mix to recharge the river. Although the isotopic composition of melted ice and snow inherits the precipitation influenced by the altitude effect, the mixed melted waters from different elevation change δ18Otributary vertical lapse rate and weaken the correlation, but do not modify the spatial patterns of δ18Otributary.

The spatial trends of mainstream δD and δ18O values are different from those of tributaries and precipitation. As shown in Figure 3, δ18Omainstream and δD mainstream increase from the upper reach to Lhaze (M15) and then decline gradually from Lhaze to Qushui (M22) in the middle reach. Below Qushui (M22), these values rise sharply along the flow direction.

In the lower reach, the trends of δ18Omainstream are similar to δ18Oprecipitation and δ18Otributaries (Figures 2, 5). Analogous patterns of evaporation and “altitude effect” on precipitation have been observed in the main flows of other large rivers globally: For example, the Ganges River in Asia (Ramesh and Sarin, 1992), the Missouri River in the United States (Winston and Criss, 2003), the Nile River in Africa (Cockerton et al., 2013), and the Yangtze River and Yellow River in China (Li et al., 2015; Fan et al., 2017). The lower reach of the YTR valley is the major transport pathway of the monsoonal moisture with more precipitation whose δ18O values are relatively high, attributable to the lower altitudes and shorter transportation distance (Tributaries). Furthermore, rainwater is the main source of surface water downstream. Therefore, δ18Otributaries, δ18Oprecipitation, and δ18Omainstream have similar trends in the lower reach.

Anomalously, in the section from Saga (M11) to Qushui (M22), δ18Omainstream and δDmainstream firstly increase and then decrease. In particular, the decreasing tendency between Lhaze (M15) and Qushui (M22) contradicts to the expected “continent effect” and “altitude effect” on the isotopic evolution of surface water. If the local precipitation controls the isotope composition of the mainstream, the values of δ18Omainstream and δDmainstream would be expected to increase downstream in theory. Moreover, it is the mainstream samples from the middle reach that deviate from the GMWL line, having lower d-excess values as, shown in Figure 4, and weakening the correlation between stable isotopes composition with longitude and altitude (Figure 3). The anomalous trend in the middle reach cannot be attributed to recharge by precipitation and melt water (δD–δ18O Relationship).

The phenomenon that main flows are isotopically enriched west of about 86°E longitude has been observed in other studies (Hren et al., 2009; Ren et al., 2016). They considered that the increasing influence of the westerlies would result in higher δ18O and d-excess of surface waters, because of the upper reach being located in the transition between monsoon-dominant area and westerlies dominant area (Hren et al., 2009; Ren et al., 2016). However, this view is not supported by our results. Firstly, the δ18O of the westernmost mainstream sample (M11) is lower than that of the adjacent main stream point downstream sample values (M15, M17, and M19). It is true for both two seasons, especially for BM series, where the δ18O of M11 is the lowest (Figure 3). Secondly, the annual weighted δ18O of precipitation in this section decreases from Lhasa to Dingri (Figure 6A). Additionally, the d-excess values of mainstream waters in this section (∼3‰ for BM and ∼1‰ for AM) are much lower than 10‰ (Figure 4B), which does not accord with the larger d-excess characteristics of westerly precipitation. Therefore, these results do not support that westerly precipitation is the main cause of the abnormal isotopic composition in the middle reach. The enhanced evaporation intensity from east to west will also lead to more positive δD and δ18O values of the upstream. However, the isotopic composition of westernmost mainstream sample (M11) is not the maximum in both two seasons. Therefore, the evaporation is not the main reason for the anomaly.

The abnormal δ18Omainstream trend in the middle reach is most likely related to groundwater recharge. Firstly, three roughly north-south rifts (Dingri-Nima (DN), Dingjie-Xietongmen- Shenzha (DXS), and Yadong-Dangxiong-Gulu (YDG) rifts) intersect the YTR valley in the middle reach (Wang et al., 2020). The tectonic fracture zones provide the conditions for a large amount of groundwater to recharge the mainstream (Zhang et al., 2021). Additionally, the hydraulic head of over 1,000 m could drive groundwater flow over long distances (Hoke et al., 2000; Tan et al., 2014). From the hydrochemical point of view, geothermal water has been suspected as the main source of the elevated (As)dissolved levels in the YTR (Zhang et al., 2021). Other major ion and 222Rn data have also strongly suggested a large addition of groundwater to the YTR in the middle reach (Tan et al., 2021). In addition, the δ18O characteristics of groundwater show significant differences from west to east in the YTR Basin (Tan et al., 2014; Liu, 2018; Liu et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2021). The nearby groundwater in the Semi (∼86.4°E) and Daggyai (∼85.6°E) geothermal field near has obvious characteristics of 18O drifts in the mixed recharge of meteoric waters and magmatic fluids (Liu et al., 2019). In Semi and Daggyai geothermal field, the δ18O maximum values of groundwater are −11.8 and −15.3‰, respectively (Liu et al., 2019). Their locations exactly coincide with the area where δ18Omainstream values are abnormally high, from Saga to Lhaze (Figure 7). However, the groundwater sampled in the range of approximately 88–92°E has been observed to be depleted in D and 18O and may have originated from paleo-precipitation during a cooler time and contributes 27–40% of the river flow (Tan et al., 2021). Near the DXS and YDG rifts, the δ18O minimum values of groundwater are −21.5‰ and −21.4‰, respectively (Tan et al., 2021). Just in this section (from Lhaze to Qushui), the δ18O value of mainstream is decreasing. In addition, for the tributaries, the δ18O values of Jiada Tsangbo (T10), Dogxung Tsangbo (T16), and Xiang Qu (T18) before the confluence are lower than that of the main stream in the middle reach (Figure 7), so the inflow of the tributaries will lead to the isotopic composition declining as well. Therefore, the following conclusions can be drawn: from the Saga (M11) to Lhaze (M15) section, the recharge of D and 18O enriched groundwater will result in the increase of the isotopic composition of the mainstream water; from Lhaze (M15) to Qushui (M22), the isotopic composition of the mainstream decreases due to the combined action of depleted D and 18O groundwater recharge and tributaries import.

FIGURE 7. The mainstream δ18O is represented by (A) red dots for BM series and (B) blue dots for AM series, respectively. The red circles in (A) and blue circles in (B) represent the δ18O of larger tributary confluences (e.g., Dogxung Tsangpo, Lhasa River, and Parlung Tsangpo) in BM and AM series. The isotopical composition values of groundwater in Semi and Daggyai geothermal field are from Liu (2018) and Liu et al. (2019). The other groundwater values for the Dingjie-Xietongmen-Shenzha (DXS) and Yadong-Dangxiong-Gulu (YDG) faults are from Tan et al. (2014) and Tan et al. (2021).

The stable isotopic characteristics of modern precipitation provide vital information to indicate moisture sources and to reconstruct paleoaltimetry. In some regions where GNIP observations are sparse, δ18O values of river water have to be used to alleviate this problem (Rowley, 2007; Timsic and Patterson, 2014; Xu et al., 2014; Li and Garzione, 2017). However, the water in a large river is generally collected from two main sources: 1) recent precipitation through surface runoff or channel precipitation or by rapid flow through the shallow subsurface and 2) groundwater recharge. The relative contribution of these sources differs in each watershed (Ogrinc et al., 2008). Therefore, the stable isotopic characteristics of river water are affected by meteorological and hydrological factors. In this study, the spatial distribution of δ18Omainstream in the YTR middle reach is significantly different from that of tributaries and local precipitation. Due to the groundwater recharge, δ18Omainstream in the section from Lhaze to Qushui is characterized by inverse isotope–elevation and isotope–moisture transport distance relationships that could produce significant misestimates of paleoaltimetry and moisture sources. Thus, when reconstructing the paleoaltimetry and tracing moisture sources using river water as a substitute for modern precipitation, it is necessary to consider that groundwater may also influence the distribution of stable isotopes in river water, especially near tectonic fracture zones where geothermal water may be characterized by remarkable high or low δ18O values.

In the YTR Basin, most of the river waters originate in precipitation and inherit the δD and δ18O characteristics of precipitation. Temporally, under the predominance of precipitation, the isotopic composition of river water is high before the monsoon precipitation (mid-June) and low after the monsoon precipitation (mid-September). Spatially, the δD and δ18O values in tributary water increase gradually from west to east and conform to the “continent effect” and “altitude effect” of precipitation. For the mainstream, rainwater is the prime source of surface water in the lower reach, with the result that the δD and δ18O variations are normally elevated. Anomalously, in the middle reach of the mainstream, the δ18O and δD firstly increase and then decrease. From Saga to Lhaze, the groundwater is characterized by high δ18O and low d-excess afflux causes the δ18Omainstream to be more positive. Then, from Lhaze to Qushui, the decrease in isotopic compositions of the mainstream is attributed to the combined action of the D and 18O depleted groundwater and tributaries import. As a result, due to the recharge of groundwater with remarkable differences in isotopic composition, the mainstream no longer simply inherits the characteristics of tributaries or precipitation: therefore, when reconstructing paleoaltimetry and tracing moisture sources by using δ18O of river water as a substitute for modern precipitation, it is necessary to rule out the influence of groundwater, especially near the tectonic fracture zones whose condition is conducive to groundwater drainage, and the δ18O of the groundwater varies significantly.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Z-QZ and J-WZ contributed to the conception of the study. Samples were collected by Z-QZ, J-WZ, G-SZ, DZ, and J-YG. JW, WZ, and Y-NY performed the isotopic analysis. Y-NY and J-WZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to article revision and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported jointly by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41661144042, 41930863, 42003007, and 42073009), the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (2019QZKK0707), and Special Fund for Basic Scientific Research of Central Colleges, Chang'an University (No. 300102278302).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors thank Cui Lifeng, Liu Taoze, Gao Shuang, Liu Xu, Ye Runcheng, Meng Junlun, Jia Guodong, Yang Ye, and Zhang Xiaolong for helping in the field work.

Armijo, R., Tapponnier, P., Mercier, J. L., and Han, T.-L. (1986). Quaternary Extension in Southern Tibet: Field Observations and Tectonic Implications. J. Geophys. Res. 91, 13803–13872. doi:10.1029/jb091ib14p13803

Bershaw, J., Penny, S. M., and Garzione, C. N. (2012). Stable Isotopes of Modern Water across the Himalaya and Eastern Tibetan Plateau: Implications for Estimates of Paleoelevation and Paleoclimate. J. Geophys. Res. 117 (D2). doi:10.1029/2011jd016132

Chen, L., Ma, T., Du, Y., Xiao, C., Chen, X., Liu, C., et al. (2016). Hydrochemical and Isotopic (2H, 18O and 37Cl) Constraints on Evolution of Geothermal Water in Coastal plain of Southwestern Guangdong Province, China. J. Volcanology Geothermal Res. 318, 45–54. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2016.03.003

Cockerton, H. E., Street-Perrott, F. A., Leng, M. J., Barker, P. A., Horstwood, M. S. A., and Pashley, V. (2013). Stable-isotope (H, O, and Si) Evidence for Seasonal Variations in Hydrology and Si Cycling from Modern Waters in the Nile Basin: Implications for Interpreting the Quaternary Record. Quat. Sci. Rev. 66, 4–21. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.12.005

Craig, H. (1961). Isotopic Variations in Meteoric Waters. Science 133 (3465), 1702–1703. doi:10.1126/science.133.3465.1702

Dansgaard, W. (1964). Stable Isotopes in Precipitation. Tellus 16 (4), 437–463. doi:10.3402/tellusa.v16i4.8993

Ding, L., Xu, Q., Zhang, L. Y., Yang, D., Lai, Q. Z., Huang, F. X., et al. (2009). Regional Variation of River Water Oxygen Isotope and Empirical Elevation Prediction Models in Tibetan Plateau. Quat. Sci. 29, 1–12. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-7410.2009.01.01

Fan, B., Zhang, D., Tao, Z., and Zhao, Z. (2017). Compositions of Hydrogen and Oxygen Isotope Values of Yellow River Water and the Response to Climate Change. China Environ. Sci. 37 (5), 1906–1914. (in Chinese, with English abstract).

Fette, M., Kipfer, R., Schubert, C. J., Hoehn, E., and Wehrli, B. (2005). Assessing River-Groundwater Exchange in the Regulated Rhone River (Switzerland) Using Stable Isotopes and Geochemical Tracers. Appl. Geochem. 20 (4), 701–712. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2004.11.006

Florea, L., Bird, B., Lau, J. K., Wang, L., Lei, Y., Yao, T., et al. (2017). Stable Isotopes of River Water and Groundwater along Altitudinal Gradients in the High Himalayas and the Eastern Nyainqentanghla Mountains. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 14, 37–48. doi:10.1016/j.ejrh.2017.10.003

Galy, A., and France-Lanord, C. (1999). Weathering Processes in the Ganges–Brahmaputra basin and the Riverine Alkalinity Budget. Chem. Geology. 159 (1–4), 31–60. doi:10.1016/s0009-2541(99)00033-9

Gao, J., Masson-Delmotte, V., Risi, C., He, Y., and Yao, T. (2013). What Controls Precipitation δ18O in the Southern Tibetan Plateau at Seasonal and Intra-seasonal Scales? A Case Study at Lhasa and Nyalam. Tellus 65 (1), 1–14. doi:10.3402/tellusb.v65i0.21043

Gao, J., Masson-Delmotte, V., Yao, T., Tian, L., Risi, C., and Hoffmann, G. (2011). Precipitation Water Stable Isotopes in the South Tibetan Plateau: Observations and Modeling*. J. Clim. 24 (13), 3161–3178. doi:10.1175/2010jcli3736.1

Garzione, C. N., Quade, J., DeCelles, P. G., and English, N. B. (2000). Predicting Paleoelevation of Tibet and the Himalaya from δ18O vs. Altitude Gradients in Meteoric Water across the Nepal Himalaya. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. (183), 219–229.

Gat, J. R., and Matsui, E. (1991). Atmospheric Water Balance in the Amazon basin: An Isotopic Evapotranspiration Model. J. Geophys. Res. 96, 13179–13188. doi:10.1029/91jd00054

Gat, J. R. (1996). Oxygen and Hydrogen Isotopes in the Hydrologic Cycle. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 24, 225–262. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.24.1.225

GMRT Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources of Xizang Tibet Autonomous Region (1993). “Regional Geology of Xizang (Tibet) Autonomous Region,”. Number 31 in People’s Republic of China Ministry of Geology and Mineral Resources-Geological Memoirs, Series 1 (Beijing: Anonymous Geological Publishing House). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Gonfiantini, R. (1986). Environmental Isotopes in Lake Studies. B. Elsevier, 113–168. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-42225-5.50008-5

Guo, X., Tian, L., Wang, L., Yu, W., and Qu, D. (2017). River Recharge Sources and the Partitioning of Catchment Evapotranspiration Fluxes as Revealed by Stable Isotope Signals in a Typical High-Elevation Arid Catchment. J. Hydrol. 549, 616–630. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2017.04.037

Hoke, G. D., Liu-Zeng, J., Hren, M. T., Wissink, G. K., and Garzione, C. N. (2014). Stable Isotopes Reveal High Southeast Tibetan Plateau Margin since the Paleogene. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 394, 270–278. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2014.03.007

Hoke, L., Lamb, S., Hilton, D. R., and Poreda, J. P. (2000). Southern Limit of Mantle Derived Geothermalhelium Emissions in Tibet: Implications for Lithospheric Structure. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 180 (3–4), 297–308. doi:10.1016/s0012-821x(00)00174-6

Hren, M. T., Bookhagen, B., Blisniuk, P. M., Booth, A. L., and Chamberlain, C. P. (2009). δ18O and δD of Streamwaters across the Himalaya and Tibetan Plateau: Implications for Moisture Sources and Paleoelevation Reconstructions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 288 (1-2), 20–32. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.08.041

Hren, M. T., Chamberlain, C. P., Hilley, G. E., Blisniuk, P. M., and Bookhagen, B. (2007). Major Ion Chemistry of the Yarlung Tsangpo-Brahmaputra River: Chemical Weathering, Erosion, and CO2 Consumption in the Southern Tibetan Plateau and Eastern Syntaxis of the Himalaya. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 71 (12), 2907–2935. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2007.03.021

Huang, X., Sillanpää, M., Duo, B., and Gjessing, E. T. (2008). Water Quality in the Tibetan Plateau: Metal Contents of Four Selected Rivers. Environ. Pollut. 156 (2), 270–277. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2008.02.014

Huang, X., Sillanpää, M., Gjessing, E. T., Peräniemi, S., and Vogt, R. D. (2011). Water Quality in the Southern Tibetan Plateau: Chemical Evaluation of the Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra). River Res. Applic. 27 (1), 113–121. doi:10.1002/rra.1332

Kendall, C., and Coplen, T. B. (2001). Distribution of Oxygen-18 and Deuterium in River Waters across the United States. Hydrol. Process. 15, 1363–1393. doi:10.1002/hyp.217

Kong, Y., and Pang, Z. (2016). A Positive Altitude Gradient of Isotopes in the Precipitation over the Tianshan Mountains: Effects of Moisture Recycling and Sub-cloud Evaporation. J. Hydrol. 542, 222–230. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.09.007

Li, L., and Garzione, C. N. (2017). Spatial Distribution and Controlling Factors of Stable Isotopes in Meteoric Waters on the Tibetan Plateau: Implications for Paleoelevation Reconstruction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 460, 302–314. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2016.11.046

Li, S.-L., Yue, F.-J., Liu, C.-Q., Ding, H., Zhao, Z.-Q., and Li, X. (2015). The O and H Isotope Characteristics of Water from Major Rivers in China. Chin. J. Geochem. 34 (1), 28–37. doi:10.1007/s11631-014-0015-5

Liu, J., Yao, Z., and Chen, C. (2007). Evolution Trend and Causation Analysis of the Runoff Evolution in the Yarlung Zangbo River basin. J. Nat. Resour. 22 (3), 471–477. doi:10.11849/zrzyxb.2007.03.017 (in Chinese with English abstract)

Liu, M. (2018). Boron Geochemistry of the Geothermal Waters from Typical Hydrothermal Systems in Tibet Doctoral Dissertation, Ph. D. Thesis. Wuhan: China University of Geoscience. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Liu, M., Guo, Q., Wu, G., Guo, W., She, W., and Yan, W. (2019). Boron Geochemistry of the Geothermal Waters from Two Typical Hydrothermal Systems in Southern Tibet (China): Daggyai and Quzhuomu. Geothermics 82, 190–202. doi:10.1016/j.geothermics.2019.06.009

Liu, T. (1999). Hydrological Characteristics of Yalungzangbo River. Acta Geographica Sinica 54 (Suppl. l), 157–164. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Liu, Z., Tian, L., Yao, T., Gong, T., Yin, C., and Yu, W. (2007). Temporal and Spatial Variations of δ18O in Precipitation of the Yarlung Zangbo River Basin. J. Geogr. Sci. 17 (3), 317–326. doi:10.1007/s11442-007-0317-1

Ma, Z., Li, X., Zheng, H., Li, J., Pei, B., Guo, S., et al. (2017). Origin and Classification of Geothermal Water from Guanzhong Basin, NW China: Geochemical and Isotopic Approach. J. Earth Sci. 28 (4), 719–728. doi:10.1007/s12583-016-0637-0

Mizutani, Y. (1972). Isotopic Composition and Underground Temperature of the Otake Geothermal Water, Kyushu, Japan. Geochem. J. 6 (2), 67–73. doi:10.2343/geochemj.6.67

Ogrinc, N., Kanduč, T., Stichler, W., and Vreča, P. (2008). Spatial and Seasonal Variations in δ18O and δD Values in the River Sava in Slovenia. J. Hydrol. 359 (3-4), 303–312. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2008.07.010

Poage, M. A., and Chamberlain, C. P. (2001). Empirical Relationships between Elevation and the Stable Isotope Composition of Precipitation and Surface Waters: Considerations for Studies of Paleoelevation Change. Am. J. Sci. 301 (1), 1–15. doi:10.2475/ajs.301.1.1

Quade, J., Breecker, D. O., Daëron, M., and Eiler, J. (2011). The Paleoaltimetry of Tibet: an Isotopic Perspective. Am. J. Sci. 311 (2), 77–115. doi:10.2475/02.2011.01

Ramesh, R., and Sarin, M. M. (1992). Stable Isotope Study of the Ganga (Ganges) River System. J. Hydrol. 139 (1–4), 49–62. doi:10.1016/0022-1694(92)90194-z

Ren, W., Yao, T., Xie, S., and He, Y. (2017b). Controls on the Stable Isotopes in Precipitation and Surface Waters across the southeastern Tibetan Plateau. J. Hydrol. 545, 276–287. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.12.034

Ren, W., Yao, T., and Xie, S. (2017a). Key Drivers Controlling the Stable Isotopes in Precipitation on the Leeward Side of the central Himalayas. Atmos. Res. 189, 134–140. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2017.01.020

Ren, W., Yao, T., and Xie, S. (2018). Stable Isotopic Composition Reveals the Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Discharge in the Large River of Yarlungzangbo in the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 625, 373–381. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.310

Ren, W., Yao, T., and Xie, S. (2016). Water Stable Isotopes in the Yarlungzangbo Headwater Region and its Vicinity of the Southwestern Tibetan Plateau. Tellus B: Chem. Phys. Meteorology 68 (1), 30397. doi:10.3402/tellusb.v68.30397

Rowley, D. B., Pierrehumbert, R. T., and Currie, B. S. (2001). A New Approach to Stable Isotope-Based Paleoaltimetry: Implications for Paleoaltimetry and Paleohypsometry of the High Himalaya since the Late Miocene. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 188, 253–268. doi:10.1016/s0012-821x(01)00324-7

Rowley, D. B. (2007). Stable Isotope-Based Paleoaltimetry: Theory and Validation. Rev. Mineralogy Geochem. 66 (1), 23–52. doi:10.2138/rmg.2007.66.2

Singh, M., Kumar, S., Kumar, B., Singh, S., and Singh, I. B. (2013). Investigation on the Hydrodynamics of Ganga Alluvial Plain Using Environmental Isotopes: a Case Study of the Gomati River Basin, Northern India. Hydrogeol J. 21 (3), 687–700. doi:10.1007/s10040-013-0958-3

Spicer, R. A., Harris, N. B. W., Widdowson, M., Herman, A. B., Guo, S., Valdes, P. J., et al. (2003). Constant Elevation of Southern Tibet over the Past 15 Million Years. Nature 421 (6923), 622–624. doi:10.1038/nature01356

Stefánsson, A., Arnórsson, S., Sveinbjörnsdóttir, Á. E., Heinemaier, J., and Kristmannsdóttir, H. (2019). Isotope (δD, δ18O, 3H, δ13C, 14C) and Chemical (B, Cl) Constrains on Water Origin, Mixing, Water-Rock Interaction and Age of Low-Temperature Geothermal Water. Appl. Geochem. 108, 104380. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2019.104380

Tan, H., Chen, X., Shi, D., Rao, W., Liu, J., Liu, J., et al. (2021). Base Flow in the Yarlungzangbo River, Tibet, Maintained by the Isotopically-Depleted Precipitation and Groundwater Discharge. Sci. Total Environ. 759, 143510. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143510

Tan, H., Zhang, Y., Zhang, W., Kong, N., Zhang, Q., and Huang, J. (2014). Understanding the Circulation of Geothermal Waters in the Tibetan Plateau Using Oxygen and Hydrogen Stable Isotopes. Appl. Geochem. 51, 23–32. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2014.09.006

Tapponnier, P., Xu, Z. Q., Roger, F., Meyer, B., Arnaud, N., Wittlinger, G., et al. (2001). Oblique Stepwise Rise and Growth of the Tibet Plateau. Science 294, 1671–1677. doi:10.1126/science.105978

Tian, L., Masson-Delmotte, V., Stievenard, M., Yao, T., and Jouzel, J. (2001b). Tibetan Plateau Summer Monsoon Northward Extent Revealed by Measurements of Water Stable Isotopes. J. Geophys. Res. 106 (D22), 28081–28088. doi:10.1029/2001jd900186

Tian, L., Yao, T., MacClune, K., White, J. W. C., Schilla, A., Vaughn, B., et al. (2007). Stable Isotopic Variations in West China: A Consideration of Moisture Sources. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 112 (D10). doi:10.1029/2006jd007718

Tian, L., Yao, T., Numaguti, A., and Sun, W. (2001a). Stable Isotope Variations in Monsoon Precipitation on the Tibetan Plateau. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 79 (5), 959–966. doi:10.2151/jmsj.79.959

Tian, L., Yao, T., Pu, J., and Yang, Z. (1997). Characteristics of δ18O in Summer Precipitation at Lhasa. J. Glaciology Geocryology 19 (4), 33–40. (in Chinese).

Tian, L., Yao, T., White, J. W. C., Yu, W., and Wang, N. (2005). Westerly Moisture Transport to the Middle of Himalayas Revealed from the High Deuterium Excess. Chin. Sci Bull 50 (10), 1026–1030. doi:10.1360/04wd0030

Timsic, S., and Patterson, W. P. (2014). Spatial Variability in Stable Isotope Values of Surface Waters of Eastern Canada and New England. J. Hydrol. 511, 594–604. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.02.017

Wang, C., Zheng, M., Zhang, X., Xing, E., Zhang, J., Ren, J., et al. (2020). O, H, and Sr Isotope Evidence for Origin and Mixing Processes of the Gudui Geothermal System, Himalayas, China. Geosci. Front. 11 (4), 1175–1187. doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2019.09.013

Wang, J., Liu, T. Q., and Yin, G. (2000). Isotopic Distribution Characteristics of Atmospheric Precipitation in the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yarlungzangbo River, Tibet. Geogeochemistry 28 (1), 63–67. (in Chinese with English abstract).

Wei, K., and Lin, R. (1994). Discuss on the Impact of Monsoon Climate on Isotope of Precipitation in China. Geochemistry 23 (1), 33–41. (in Chinese).

Wen, R., Tian, L., Weng, Y., Liu, Z., and Zhao, Z. (2012). The Altitude Effect of δ 18O in Precipitation and River Water in the Southern Himalayas. Chin. Sci. Bull. 57 (14), 1693–1698. doi:10.1007/s11434-012-4992-7

Winston, W., and Criss, R. (2003). Oxygen Isotope and Geochemical Variations in the Missouri River. Env Geol. 43 (5), 546–556. doi:10.1007/s00254-002-0679-8

Wu, H., Wu, J., Sakiev, K., Liu, J., Li, J., He, B., et al. (2019). Spatial and Temporal Variability of Stable Isotopes (δ 18 O and δ 2 H) in Surface Waters of Arid, Mountainous Central Asia. Hydrological Process. 33 (12), 1658–1669. doi:10.1002/hyp.13429

Xu, Q., Hoke, G. D., Liu-Zeng, J., Ding, L., Wang, W., and Yang, Y. (2014). Stable Isotopes of Surface Water across the Longmenshan Margin of the Eastern Tibetan Plateau. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 15 (8), 3416–3429. doi:10.1002/2014gc005252

Xu, Y., Kang, S., Zhang, Y., and Zhang, Y. (2011). A Method for Estimating the Contribution of Evaporative Vapor from Nam Co to Local Atmospheric Vapor Based on Stable Isotopes of Water Bodies. Chin. Sci. Bull. 56 (14), 1511–1517. doi:10.1007/s11434-011-4467-2

Yang, D. D., Oyang, H., Zhou, C. P., and Chen, C. Y. (2011). Runoff Characteristics of the Nyang Qu River on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Resour. Sci. 33 (7), 1272–1277. doi:10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2012.01.012 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Yang, X., Xu, B., Yang, W., and Qu, D. (2012a). The Indian Monsoonal Influence on Altitude Effect of δ 18O in Surface Water on Southeast Tibetan Plateau. Sci. China Earth Sci. 55 (3), 438–445. doi:10.1007/s11430-011-4342-7

Yang, X., Yao, T., Yang, W., Xu, B., He, Y., and Qu, D. (2012b). Isotopic Signal of Earlier Summer Monsoon Onset in the Bay of Bengal. J. Clim. 25 (7), 2509–2516. doi:10.1175/jcli-d-11-00180.1

Yao, T., Masson-Delmotte, V., Gao, J., Yu, W., Yang, X., Risi, C., et al. (2013). A Review of Climatic Controls on δ18O in Precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau: Observations and Simulations. Rev. Geophys. 51 (4), 525–548. doi:10.1002/rog.20023

Yin, G., Ni, S., and Zhang, Q. (2001). Deuterium Excess Parameter and Geohydrology Significance: Taking the Geohydrology Researches in Jiuzaigou and Yele, Sichuan for Example. J. Chen GDU Univ. Technol. 28 (3), 251–254. doi:10.1016/s1164-6756(01)00107-4

You, Q., Kang, S., Wu, Y., and Yan, Y. (2007). Climate Change over the Yarlung Zangbo River Basin during 1961-2005. J. Geogr. Sci. 17 (4), 409–420. doi:10.1007/s11442-007-0409-y

Yu, W., Yao, T., Tian, L., Ma, Y., Ichiyanagi, K., Wang, Y., et al. (2008). Relationships between δ18O in Precipitation and Air Temperature and Moisture Origin on a South-north Transect of the Tibetan Plateau. Atmos. Res. 87 (2), 158–169. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2007.08.004

Yu, W., Yao, T., Tian, L., Ma, Y., Wen, R., Devkota, L. P., et al. (2016). Short-term Variability in the Dates of the Indian Monsoon Onset and Retreat on the Southern and Northern Slopes of the central Himalayas as Determined by Precipitation Stable Isotopes. Clim. Dyn. 47 (1), 159–172. doi:10.1007/s00382-015-2829-1

Zhang, J.-W., Yan, Y.-N., Zhao, Z.-Q., Li, X.-D., Guo, J.-Y., Ding, H., et al. (2021). Spatial and Seasonal Variations of Dissolved Arsenic in the Yarlung Tsangpo River, Southern Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 760, 143416. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143416

Zhang, P.-Z., Shen, Z., Wang, M., Gan, W., Bürgmann, R., Molnar, P., et al. (2004). Continuous Deformation of the Tibetan Plateau from Global Positioning System Data. Geol 32, 809. doi:10.1130/g20554.1

Zhang, W., Tan, H., Zhang, Y., Wei, H., and Dong, T. (2015). Boron Geochemistry from Some Typical Tibetan Hydrothermal Systems: Origin and Isotopic Fractionation. Appl. Geochem. 63, 436–445. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2015.10.006

Keywords: stable isotopes, Yarlung Tsangpo River, mainstream, tributaries, groundwater recharge

Citation: Yan Y-N, Zhang J-W, Zhang W, Zhang G-S, Guo J-Y, Zhang D, Wu J and Zhao Z-Q (2021) Spatiotemporal Variation of Hydrogen and Oxygen Stable Isotopes in the Yarlung Tsangpo River Basin, Southern Tibetan Plateau. Front. Earth Sci. 9:757094. doi: 10.3389/feart.2021.757094

Received: 11 August 2021; Accepted: 08 October 2021;

Published: 10 November 2021.

Edited by:

Mao-Yong He, Institute of Earth Environment (CAS), ChinaCopyright © 2021 Yan, Zhang, Zhang, Zhang, Guo, Zhang, Wu and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jun-Wen Zhang, emhhbmdqdW53ZW5AdGp1LmVkdS5jbg==; Zhi-Qi Zhao, emhhb3poaXFpQGNoZC5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.