94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Earth Sci., 21 November 2017

Sec. Quaternary Science, Geomorphology and Paleoenvironment

Volume 5 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2017.00093

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Role of the Paleo-Critical Zone in Shaping Quaternary Hominin EvolutionView all 6 articles

Emily J. Beverly1,2*

Emily J. Beverly1,2* Daniel J. Peppe1

Daniel J. Peppe1 Steven G. Driese1

Steven G. Driese1 Nick Blegen3,4

Nick Blegen3,4 J. Tyler Faith5

J. Tyler Faith5 Christian A. Tryon4

Christian A. Tryon4 Gary E. Stinchcomb6

Gary E. Stinchcomb6The impact of changing environments on the evolution and dispersal of Homo sapiens is highly debated, but few data are available from equatorial Africa. Lake Victoria is the largest freshwater lake in the tropics and is currently a biogeographic barrier between the eastern and western branches of the East African Rift. The lake has previously desiccated at ~17 ka and again at ~15 ka, but little is known from this region prior to the Last Glacial Maximum. The Pleistocene terrestrial deposits on the northeast coast of Lake Victoria (94–36 ka) are ideal for paleoenvironmental reconstructions where volcaniclastic deposits (tuffs), fluvial deposits, tufa, and paleosols are exposed, which can be used to reconstruct Critical Zones (CZ) of the past (paleo-CZs). The paleo-CZ is a holistic concept that reconstructs the entire landscape using geologic records of the atmosphere, hydrosphere, lithosphere, biosphere, and pedosphere (the focus of this study). New paleosol-based mean annual precipitation (MAP) proxies from Karungu, Rusinga Island, and Mfangano Island indicate an average MAP of 750 ± 108 mm year−1 (CALMAG), 800 ± 182 mm year−1 (CIA-K), and 1,010 ± 228 mm year−1 (PPM1.0) with no statistical difference throughout the 11 m thick sequence. This corresponds to between 54 and 72% of modern precipitation. Tephras bracketing these paleosols have been correlated across seven sites, and sample a regional paleo-CZ across a ~55 km transect along the eastern shoreline of the modern lake. Given the sensitivity of Lake Victoria to precipitation, it is likely that the lake was significantly smaller than modern between 94 and 36 ka. This would have removed a major barrier for the movement of fauna (including early modern humans) and provided a dispersal corridor across the equator and between the rifts. It is also consistent with the associated fossil faunal assemblage indicative of semi-arid grasslands. During the Late Pleistocene, the combined geologic and paleontological evidence suggests a seasonally dry, open grassland environment for the Lake Victoria region that is significantly drier than today, which may have facilitated human and faunal dispersals across equatorial East Africa.

The interdisciplinary Critical Zone (CZ) research initiative opened up a new way of thinking about near surface environments where complex interactions between rock, soil, water, air, and living organisms shape the Earth's surface (National Research Council, 2001). Soils are central to the understanding of the CZ and the CZ Observatories have made great leaps forward in understanding of soil's role in the CZ (e.g., White et al., 2015). The purpose of the CZ Observatories is to better understand the current biogeochemical products of interactions between the atmosphere, hydrosphere, and lithosphere that form the pedosphere and biosphere. A better understanding of current CZ will allow for better predictions of future impacts resulting from climate, tectonics, or human activities (Brantley et al., 2007). Proxies for the atmosphere (e.g., mean annual precipitation, mean annual temperature), biosphere (photosynthetic pathway), hydrosphere (flood frequency and magnitude), and pedosphere (redox, pH, soil fertility) have all been developed to reconstruct past land surfaces (Nordt and Driese, 2013). The combination of these interdisciplinary methods allow for the reconstruction of biogeochemical interactions within a past landscape comparable to modern CZ studies (Amundson et al., 2007; Brantley et al., 2007; Dere et al., 2015) and termed the paleo-Critical Zone (paleo-CZ) by Nordt and Driese (2013). These paleo-CZs preserve a snapshot in time of the conditions that existed on a previous land surface and can be correlated regionally or locally. Any preserved land surface could be reconstructed using the paleo-CZ concept, but it is most often applied with paleosols (fossil soils), which are important records of the paleo-CZs. The paleo-CZ concept has continued to gain traction in the sedimentary geology community and especially those interested in paleosols.

Paleosols provide valuable records of both paleoenvironmental and paleoclimate information (Sheldon and Tabor, 2009; Levin, 2015; Tabor and Myers, 2015), and using paleosols to reconstruct the landscape as a paleo-CZ is particularly useful for understanding hominin evolution because these paleosols represent the past surfaces upon which hominins lived. The earliest fossil remains attributed to Homo sapiens are identified in northwestern Africa at ~315 ka (Richter et al., 2017) and in East Africa at ~195 ka (McDougall et al., 2005). The mechanism for the emergence and dispersal of early modern humans is still poorly understood due to limited number of sites with coexisting fossils, artifacts, and paleoenvironmental records (McDougall et al., 2005; Brown et al., 2012; Soares et al., 2012; Rito et al., 2013). Environmental change driven by climate is a commonly suggested mechanism (Ambrose and Lorenz, 1990; Potts, 1998; Scholz et al., 2007; Blome et al., 2012; Soares et al., 2012; Rito et al., 2013; Potts and Faith, 2015; Tierney et al., 2017), but few data on African climate or environment are associated with archaeological sites prior the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) in East Africa. This makes additional data from the Lake Victoria Basin of equatorial East Africa important especially because it directly ties pre-LGM climatic reconstructions to fossil fauna and Middle Stone Age (MSA) tools.

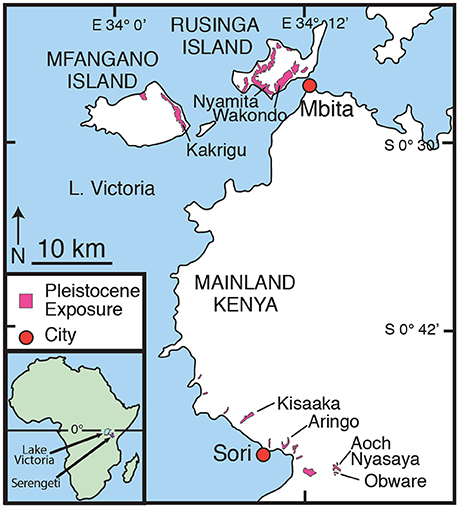

Here we present data from stratigraphy, micromorphology (petrography), and bulk geochemistry from six Late Pleistocene sites from northeastern Lake Victoria in Kenya that were deposited between 94 and 36 ka (Tryon et al., 2014, 2016; Beverly et al., 2015b; Blegen et al., 2015). These sites sample an approximately 55 km-long north to south transect along the eastern margin of the modern lake: Rusinga Island (n = 2), Mfangano Island (n = 1), and Karungu (n = 4) (Figure 1; Tryon et al., 2014, 2016; Beverly et al., 2015a,b; Blegen et al., 2015; Faith et al., 2015; Garrett et al., 2015). These deposits are all part a sequence of late Pleistocene deposits around the northeastern margin of Lake Victoria and the stratigraphy is dominated by paleosols, freshwater tufa, fluvial deposits, and volcaniclastic deposits (tuffs) that can be geochemically correlated between outcrops (Tryon et al., 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016; Van Plantinga, 2011; Beverly et al., 2015a,b; Blegen et al., 2015, 2016; Faith et al., 2015). The objectives of this study are to: (1) use field and micromorphological observations of paleosols and bulk geochemical proxies for paleoenvironment and paleoclimate to reconstruct a series of paleo-CZs across the northeastern margin of Lake Victoria, (2) provide additional context for fossil fauna and MSA sites, and (3) integrate observations and MAP estimates into other Late Pleistocene reconstructions of regional paleoclimate and paleoenvironment to better understand their impact on human evolution and dispersal.

Figure 1. Location of Karungu and Mfangano and Rusinga Islands in western Kenya along the eastern shore of Lake Victoria. Areal extent of Late Pleistocene outcrops in this study is shown in pink. Inset map shows the locations of Lake Victoria and the Serengeti Ecosystem in East Africa.

Today there is very little annual variability in temperature at Lake Victoria (Nicholson, 1996). Precipitation, however, varies considerably and is controlled by the location of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), which crosses Lake Victoria twice a year, creating rainy seasons in March and in October (Nicholson, 1996). Precipitation is also controlled by the movement of the Congo Air Boundary (CAB), the strength of the Indian and Atlantic monsoons, and topography (Berke et al., 2012). MAP across the catchment varies from 1,400 to 1,800 mm year−1 (Yin and Nicholson, 1998; Sutcliffe and Parks, 1999). Because MAP is almost equal to average evaporation (1,460 mm year−1), with local precipitation derived primarily from the lake itself, lake level responds directly to changes in rainfall (Broecker et al., 1998; Yin and Nicholson, 1998; Milly, 1999; Bootsma and Hecky, 2003). The historic vegetation from the Lake Victoria region is evergreen bushland, thicket, and forest habitats (Andrews, 1973; White, 1983). In the Lambwe Valley, between Rusinga Island and Karungu, the large mammalian herbivores historically included bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus), African buffalo (Syncerus caffer), Bohor reedbuck (Redunca redunca), waterbuck (Kobus ellipsiprymnus), duiker (Sylvicapra grimmia), topi (Damaliscus lunatus), impala (Aepyceros melampus), hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus), roan antelope (Hippotragus equinus), oribi (Ourebia ourebi), giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis), black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis), bushpig (Potamochoerus larvatus), and elephant (Loxodonta africana) (Allsopp and Baldry, 1972; Kimanzi, 2011).

The Late Pleistocene geology, fossils, and MSA artifacts from Rusinga and Mfangano Islands have been the focus of research since 2009 (Tryon et al., 2010, 2012, 2014; Faith et al., 2011, 2012, 2014; Van Plantinga, 2011; Jenkins et al., 2017; Blegen et al., in press). More recently, this research has expanded to include the deposits around the region known as Karungu ~40 km to the south near the town of Sori (Figure 1; Beverly et al., 2015a,b; Blegen et al., 2015; Faith et al., 2015). Abundant fossils and MSA artifacts have long been reported from Karungu and Rusinga and Mfangano Islands (Pickford, 1984; Owen, unpublished manuscript), but until recently only limited geological mapping and reconstructions of the paleoclimate or paleoenvironment have been conducted. Karungu and Rusinga and Mfangano Islands were originally mapped by Oswald (1914), Kent (1942), Van Couvering (1972), Whitworth (1961), and Pickford (1984) and have been more intensively mapped by Beverly et al. (2015a,b), Blegen et al. (2015, 2016), and Tryon et al. (2010, 2012, 2014).

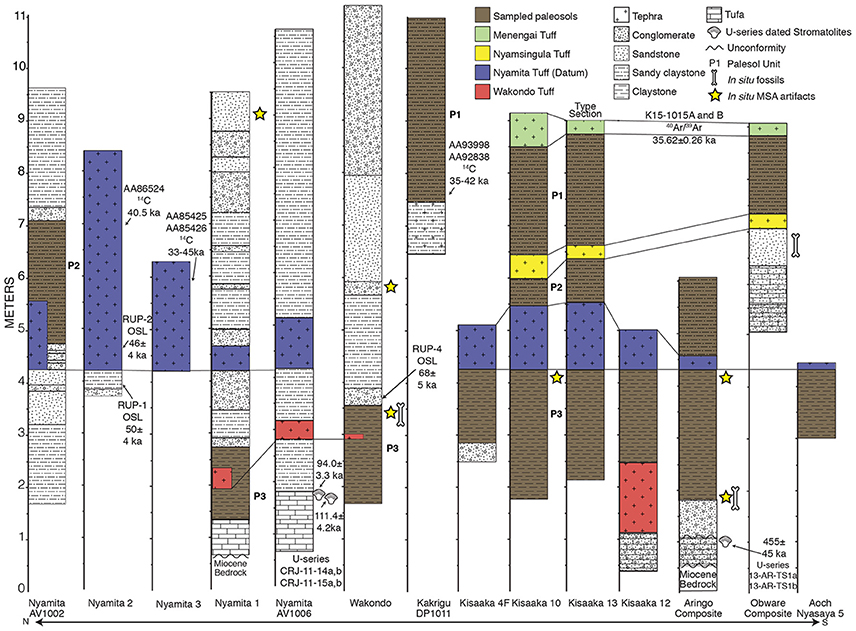

Artifacts and fossils were surface collected from all units and excavations have been conducted at Wakondo, Nyamita, and Aringo (Figures 1, 2). Locations of in situ fossils and MSA artifacts are indicated in the stratigraphy (Figure 2). Artifacts from excavations at Nyamita and Wakondo on Rusinga Island in particular appear associated with formerly stable land surfaces, including weakly developed paleosols (Jenkins et al., 2017; Blegen et al., in press). Artifact density and the presence of non-local raw material types from excavated areas and surface collections are generally consistent with production by highly mobile populations of foragers (Tryon et al., 2010; Faith et al., 2015; Garrett et al., 2015; Blegen et al., in press).

Figure 2. Stratigraphy of paleosols used in this study. The dates (and associated lab samples numbers) identified on this figure are discussed further in Blegen et al. (2015, 2016), Beverly et al. (2015b), and Tryon et al. (2010, 2012). The Nyamita and Wakondo Tuffs at the Nyamita AV1002, Nyamita 1, and Wakondo localities are discontinuous due to their proximity to fluvial channels and are shown in their correlated positions within the paleosols. The localities were sampled to access the most complete paleosol record. Refer to Table 2 for detailed descriptions of each paleosol unit (e.g., P1 to P3).

Tephra deposits can be correlated between sites on the basis of geochemical compositional similarity and have been dated by multiple radiometric methods (Tryon et al., 2010; Beverly et al., 2015b; Blegen et al., 2015, 2016, in press). Four named tuffs are used to correlate the sections between Rusinga Island and Karungu: Wakondo, Nyamita, Nyamsingula, and Menengai. The Wakondo Tuff is >68 ± 5 ka based on overlying optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dates and <94.0 ± 3.3 based on the U-series age of the underlying tufa deposits (Beverly et al., 2015b; Blegen et al., 2015). Additional data on the tufas are presented in Beverly et al. (2015b). The Nyamita Tuff is constrained by OSL dates above and below the tuff that indicate deposition at ~49 ka (Blegen et al., 2015). The Nyamita Tuff is thick, distinct, and found at almost all Pleistocene sites in this region, making it an ideal stratigraphic datum (Figure 2). The Menengai Tuff has been 40Ar/39Ar dated to 35.62 ± 0.26 ka at its eruptive source, Menengai Caldera in the Central Kenya Rift (Blegen et al., 2016), and the Nyamsingula Tuff is dated to between 36 and 49 ka based on the stratigraphic relationships with the underlying Nyamita Tuff and overlying Menengai Tuff (see Blegen et al., 2015, 2016, in press for an extensive discussion of tephra correlations and dates).

All outcrops were recorded and mapped using a hand-held global positioning system (GPS) (Table 1), trenches were dug to expose bedding unaltered by modern surface processes, and the stratigraphy measured and described at the cm scale. All lithologic and pedogenic features were recorded and photographed, and oriented samples were also collected for micromorphological analysis from each soil horizon at Kisaaka and Aringo, and in the B horizon at Wakondo (n = 19). These thin sections were stabilized in the field and lab using epoxy, and then vacuum impregnated and commercially prepared by Spectrum Petrographics, Inc. The micromorphological analysis was conducted at Baylor University following Fitzpatrick (1993) and Stoops (2003) using an Olympus BX-51 polarized-light microscope equipped with a 6.5 MPx Leica digital camera.

Samples were collected at 10 cm vertical intervals through the paleosols for bulk geochemistry, and where applicable, samples were collected from the micro-lows of gilgai topography in the paleo-Vertisols because erosion is less likely and pedogenesis is highest (Driese et al., 2000). Bulk geochemical samples were pulverized at Baylor University prior to being sent for commercial analysis to ALS Geochemistry (Reno, NV) for major, rare, and trace element analyses using a combination of inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). The complete geochemical analyses of all samples are available in Supplementary Table 1. Bulk geochemical data were used to estimate MAP using the chemical index of alteration minus potassium (CIA-K) (Sheldon et al., 2002) and the paleosol-paleoclimate model (PPM1.0) (Stinchcomb et al., 2016) both of which are applicable for most paleosol types. The CALMAG proxy is only applicable for paleo-Vertisols (Nordt and Driese, 2010).

All oxides were normalized to their molar ratios and were calculated by averaging the oxides over the critical depth, defined as 20–100 cm (Nordt and Driese, 2010). If the BC or C horizon fell within the critical depth, only B horizons were used. CIA-K is defined as:

and was designed to be more widely applicable paleosol types in which there has been sufficient time of soil formation to equilibrate with climate conditions and is a weathering index that measures base loss and clay formation associated with feldspar weathering (Sheldon et al., 2002). It is not useful for paleosols with evaporative minerals at the surface (i.e., Aridisols), waterlogged soils, highly weathered soils (i.e., Oxisols), or soils forming on significant topographic relief (Sheldon et al., 2002).

CALMAG is a weathering index specifically for paleo-Vertisols (Nordt and Driese, 2010) that is defined as:

Vertisols are formed from pre-weathered parent material, and therefore limited hydrolysis occurs in this soil type, and for this reason, CIA-K often over-predicts precipitation in Vertisols. The CALMAG proxy improves the paleoprecipitation estimates of paleo-Vertisols by focusing on tracking the flux of Ca and Mg, which better describe the weathering occurring in Vertisols (Nordt and Driese, 2010). Both the CIA-K and CALMAG weathering indices in modern soils have a strong correlations to MAP and these indices can be used to estimate paleo-rainfall with a standard error (SE) of ±182 mm year−1 and ±108 mm year−1, respectively (Sheldon et al., 2002; Nordt and Driese, 2010).

PPM1.0 was developed using data from 648 soil B horizons, and it uses 11 oxides: Al2O3, ZrO2, TiO2, Fe2O3, P2O5, MnO, CaO, MgO, Na2O, K2O, and SiO2 which are reduced to four regressors (like oxide ratios) using partial least squares regression. The regressors are modeled using a semi-parametric spline that yields MAP. This new model greatly expanded the range of precipitations to between 130 and 6,900 mm year−1 with a RMSPE of ±512 mm year−1. Similar to CIA-K and CALMAG, all of the modern soils used to model MAP are from the United States and its territories.

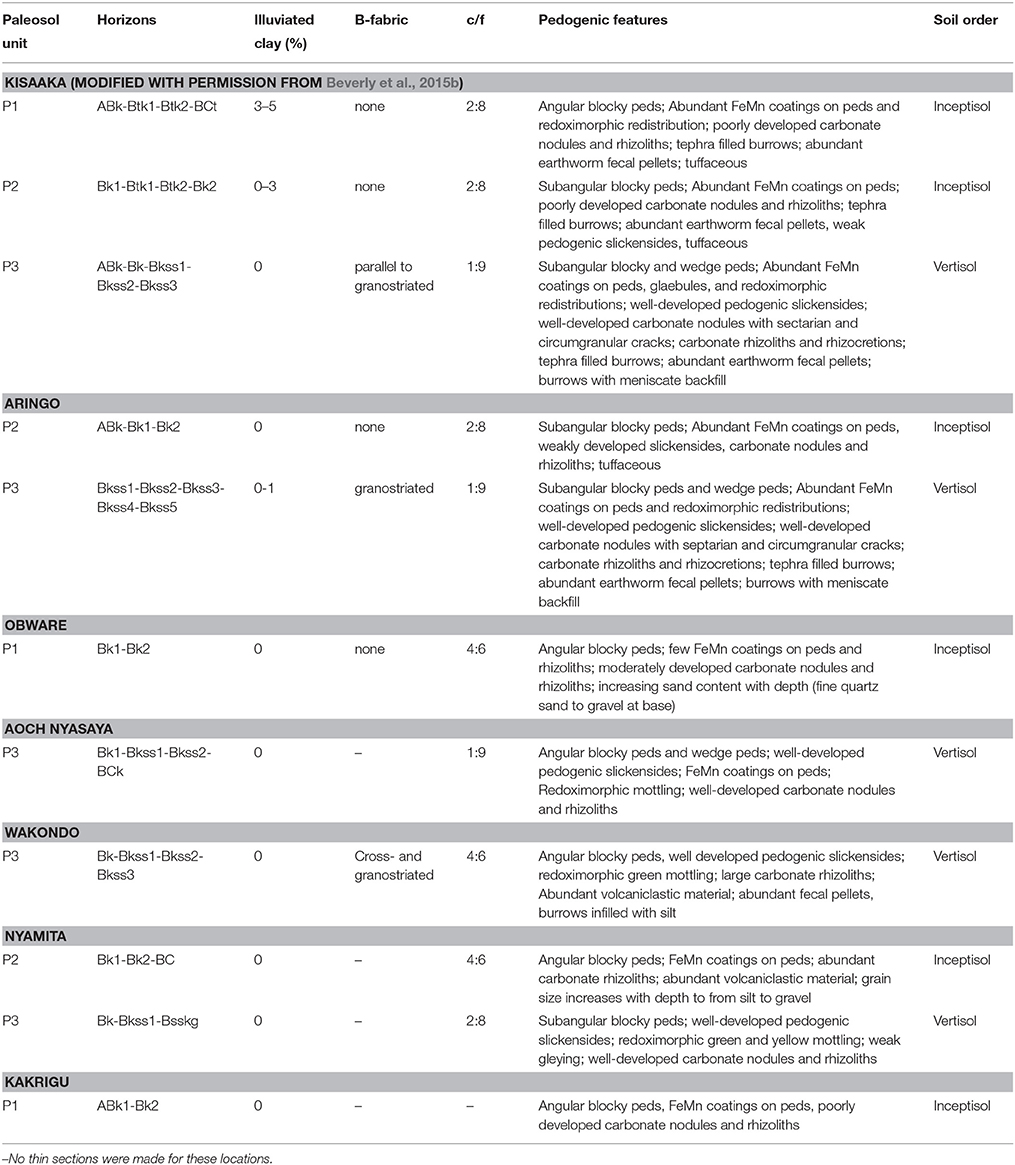

Riverine tufa deposits were a recurring feature in the Pleistocene on the eastern margin of Lake Victoria, until ~94 ka when the system became dominated by fluvial deposition and tufa precipitation ceased (Beverly et al., 2015b). The thickest section of the late Pleistocene deposits exposed in the Karungu region is at Kisaaka (Figures 1, 2). Kisaaka has been previously described in greater detail in Beverly et al. (2015a), but the soil features are summarized here for consistency along with all other paleosols sampled for bulk geochemical analysis. Additional details for each paleosol are provided in Table 2 and in Supplementary Table 1, including soil horizons identified, soil b-fabric, percent illuviated clay, ratio of coarse to fine fraction, pedogenic features, depths of each sample collected, and USDA soil order.

Table 2. Summary of field and micromorphological descriptions of type section paleosols from each site.

The paleosols are designated as Paleosol 3 (oldest; P3) to 1 (youngest; P1) and can be correlated across the landscape using tephrostratigraphy (Figure 2). A well-developed paleo-Vertisol (P3) with pedogenic slickensides, wedge peds, parallel to granostriated b-fabric, and smectitic mineralogy overlies the tufa deposits that formed the base of the stratigraphic sequence (Tryon et al., 2014; Beverly et al., 2015a,b). This paleo-Vertisol, identified as Paleosol 3, was long-lived and formed between ~94 and 49 ka, with the upper age constraint corresponding to deposition of the Nyamita Tuff (Blegen et al., 2015). Overlying the Nyamita Tuff, Paleosol 2 is identified as a paleo-Inceptisol due to the lack of vertic features, angular blocky ped structure, FeMn coatings, and 0–3% illuviated clay coatings (Table 2). Paleosol 1, which is stratigraphically between the Nyamsingula and Menengai Tuffs, has identical pedogenic features to Paleosol 2, but a higher percentage of illuviated clay coatings (3–5%). Both Paleosols 1 and 2 have smectitic mineralogy, but higher amounts of tephra than Paleosol 3, likely limiting their shrink-swell capacity.

The Aringo Site (Figure 1) contains two paleosols: one below (P3) and one above the Nyamita Tuff (P2; Figure 2). Paleosol 3 is identified by the abundant vertic features in both outcrop (pedogenic slickensides) and in thin section (granostriated b-fabric), and smectitic mineralogy. Paleosol 2 at Aringo is a tuffaceous paleo-Inceptisol with angular blocky peds, FeMn coatings on peds, carbonate nodules, but is slightly less developed than at Kisaaka because no illuviated clay coatings were identified.

One paleosol was identified at Aoch Nyasaya below the Nyamita Tuff. This paleo-Vertisol is dominated by a smectitic clay mineralogy, pedogenic slickensides, and well developed pedogenic carbonates, and is identified as Paleosol 3 (Figure 2, Table 2). One paleosol was also identified at the nearby Obware site, which overlies the Nyamsingula Tuff and is capped by the Menengai Tuff and can therefore be correlated to Paleosol 1 at the Kisaaka type section (Figure 2). The mineralogy of this paleosol is dominated by quartz with a fining-upward succession of gravel to fine sand. This paleosol is also classified as a paleo-Inceptisol due to the angular blocky peds, FeMn coatings, and moderately developed pedogenic carbonates.

The stratigraphy was measured and paleosols were previously identified at Rusinga and Mfangano Islands (Tryon et al., 2010, 2012; Van Plantinga, 2011; Garrett et al., 2015), but this is the first detailed description of the paleosols from three sites: Nyamita, Wakondo, and Kakrigu. In general, these paleosols are weakly developed in comparison to Karungu and have a much larger grain size and increased volcaniclastic input (Table 2). Paleosols from two sites on Rusinga Island are examined here: Nyamita and Wakondo (Figure 1).

Two paleosols were described at Nyamita from two different localities: Nyamita 1 and Nyamita AV1006 (Figure 2). Nyamita 1 can be correlated to Paleosol 3 because it underlies the Nyamita Tuff. This paleo-Vertisol has well developed pedogenic slickensides and pedogenic carbonates as well as redoximorphic green and yellow mottling of the matrix. A paleosol overlying the Nyamita Tuff at the Nyamita AV1002 locality can be correlated to Paleosol 2 and is a weakly developed paleo-Inceptisol with high volcaniclastic input, angular blocky peds, FeMn coatings, and carbonate rhizoliths. One paleosol was identified at Wakondo that can be correlated to Paleosol 3 based on the position of the Wakondo Tuff. It is very similar to the paleo-Vertisol identified at Kisaaka, Aringo, Aoch Nyasaya, and Nyamita with well-developed vertic features (pedogenic slickensides and cross- and granostriated b-fabrics) and pedogenic carbonates.

The Kakrigu Site on Mfangano Island contains one weakly-developed paleo-Inceptisol with angular blocky peds, FeMn coatings, and poorly developed carbonate nodules and, based on the radiocarbon dating of gastropod shells, most likely correlates to the uppermost Paleosol 1.

Bulk geochemistry from 7 paleosols previously published in Beverly et al. (2015a) and new data from 6 additional paleosols were used to estimate MAP using the following proxies: CALMAG (Nordt and Driese, 2010) for Vertisols only, and CIA-K (Sheldon et al., 2002) and PPM1.0 (Stinchcomb et al., 2016) for all other paleosol types. CALMAG was only applied to those paleosols identified as paleo-Vertisols based on these vertic features: pedogenic slickensides, wedge peds, rhizocretions, and micromorphological features indicative of shrink-swell processes (i.e., b-fabrics and septarian and circumgranular cracks). The CALMAG estimates for MAP range from 557 to 911 mm year−1 with an average of 750 mm year−1 (Table 3). The CIA-K estimates for MAP range from 552 to 1,000 mm year−1 with an average of 800 mm year−1. The PPM1.0 estimates for MAP range from 747 to 1,283 mm year−1 with an average of 1,010 mm year−1. The CIA-K and PPM1.0 proxies were applicable for all identified paleosols because none are identified as paleo-Aridisols or Oxisols, they have no significant topographic relief, and they have no evidence indicative of a highly waterlogged soil. The Nyamita Tuff is used as a division between the upper and lower paleosols because it is dated to ~49 ka (OSL), and because it is lithologically distinct and a visible stratigraphic marker on the landscape that is present at most sites.

The stratigraphy at Karungu and Rusinga and Mfangano Islands (Figure 2) is dominated by paleosols that, based on various dating methods (Blegen et al., 2015, 2016) and paleosol features, likely represents most of the ~58 kyr interval between 94 and 36 ka. Paleosol 3 is dated to between 94 and 49 ka and is identified across the region at Kisaaka, Aringo, Aoch Nyasaya, Wakondo, and Nyamita. The very well-developed pedogenic slickensides and pedogenic carbonates indicate that this paleo-Vertisol was subjected to prolonged pedogenesis and was a stable land surface regionally for a long period of time. The paleo-Inceptisols above the Nyamita Tuff are dated to between 49 and 36 ka and pedogenic features identified in these paleosols support the interpretation that they were deposited over a shorter duration of time. The paleo-Inceptisols from Kisaaka and Aringo contain up to 3–5% illuviated clay. Using the age-estimate model for clay coating accumulation by Ufnar (2007), 3–5% illuviated clay indicates that pedogenesis occurred for ~3–7 kyr per paleosol (Beverly et al., 2015a). This may be an overestimation for an East African monsoonal climate, which may weather more quickly than subtropical soils from southeastern Mississippi used to develop this chronofunction (Ufnar, 2007), but it does indicate a period of weathering long enough for the soil to come into equilibrium with climate. The three paleosols preserved in the late Pleistocene deposits along the northeastern margin of Lake Victoria are spread across an area of ~1,000 km2 along the northeastern margins of Lake Victoria and thus can be inferred to represent regional climate. Based on their distribution and our age estimates for pedogenesis, these three paleosols likely represent a time-averaged, but relatively complete, record of ~58 kyr of climate in the Lake Victoria region between 94 and 36 ka.

MAP estimates range from 557 to 1,283 with an average of 750 ± 108, 800 ± 182, and 1,010 ± 228 mm year−1 for the CALMAG, CIA-K, and PPM1.0 proxies, respectively (Table 3). Although there is variability between each proxy, they are within standard error margins, and all estimates are significantly less than modern MAP in the Lake Victoria basin. Calculating precipitation over the Lake Victoria Basin is difficult due to the lack of consistent station coverage and interruptions in recording periods (Yin and Nicholson, 1998), and thus reported precipitation varies wildly. The most commonly reported MAP ranges from 1,400 to 1,800 mm year−1 (Yin and Nicholson, 1998; Sutcliffe and Parks, 1999). Assuming a MAP of 1,400 mm year−1, this suggests that average precipitation during the Late Pleistocene was 54, 57, or 72% of modern precipitation (CALMAG, CIA-K, and PPM1.0 proxies, respectively). Thus, we suggest that the Lake Victoria region was likely significantly drier for this entire interval, but acknowledge that sub-millennial scale trends may not be resolvable. This agrees with isotopic data from fossil fauna, which document a >20% reduction in MAP relative to modern conditions (Garrett et al., 2015).

Given our evidence for drier conditions and previous water budget modeling for the lake, we hypothesize that Lake Victoria had a much smaller surface area than modern from 94 to 36 ka. Previous water budget models (Broecker et al., 1998; Milly, 1999) indicate that Lake Victoria would be reduced to <20% of current surface area with a MAP between 557 and 1,283 mm year−1. A Late Pleistocene dessication surface of unknown duration is also identified in Lake Victoria at ~80 ka using sedimentation rates and seismic stratigraphy (Stager and Johnson, 2008), which supports our interpretation. Additionally, this dry interval between 94 and 36 ka in the Lake Victoria region also partially overlaps with the megadrought identified in Lakes Malawi, Tanganyika, and Bosumtwi between 135 and 70 ka (Scholz et al., 2007) with a revised age-model indicating Lake Malawi was significantly lower between 146 and 115 ka and again between 107 and 74 ka and has remained deep since ~70 ka (Lyons et al., 2015; Ivory et al., 2016).

Zonal shifts in the ITCZ are often used to explain precipitation changes in tropical Africa; however, it is unlikely that the ITCZ could be shifted so far south to prevent its bi-annual crossing of Lake Victoria. Widespread climatic variability likely peaked between 145 and 60 ka (Laskar et al., 2004; Scholz et al., 2007) due to eccentricity-enhanced precession, and climate modeling (Clement et al., 2004) indicates that when eccentricity is high, precessional forcing is greater at low latitudes compared to high latitudes. This orbital mechanism explains the aridity for Lakes Malawi, Tanganyika, Botsumtwi, and Victoria during the megadrought, but after 70 ka, all these lakes began to refill, with the exception of Lake Victoria (based on MAP estimates and previous water budget modeling). The refilling of these lakes is attributed to stable precipitation conditions as eccentricity decreased (Scholz et al., 2007). The paleosol-based paleoprecipitation reconstruction indicates that Lake Victoria region remained dry until 36 ka, which is similar to the cooler and drier conditions in the Horn of Africa between 50 and 75 ka (Tierney et al., 2017) and to the record of Lake Naivasha (Trauth et al., 2003), ~250 km to the east. Because eccentricity decreased from 70 to 36 ka, the cause for extended aridity from ~70 to 36 ka in the Lake Victoria region must be due to factors other than eccentricity-enhanced precession. Lake Naivasha level was low-to-intermediate between 105 and 60 ka and dry between 60 and ~35 ka (Trauth et al., 2003). Low levels in Lake Naivasha have been attributed to low sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Indian Ocean that weakened the monsoon (Bard et al., 1997; Trauth et al., 2003), and the desiccation of Lake Victoria between 15 and 18 ka has similarly been attributed to low SSTs (Stager et al., 2011). This suggests that Lake Victoria may have been antiphased with the southern tropics between 70 and 36 ka as has been demonstrated in other records (Partridge et al., 1997; Gasse, 2000; Trauth et al., 2003; Castañeda et al., 2007).

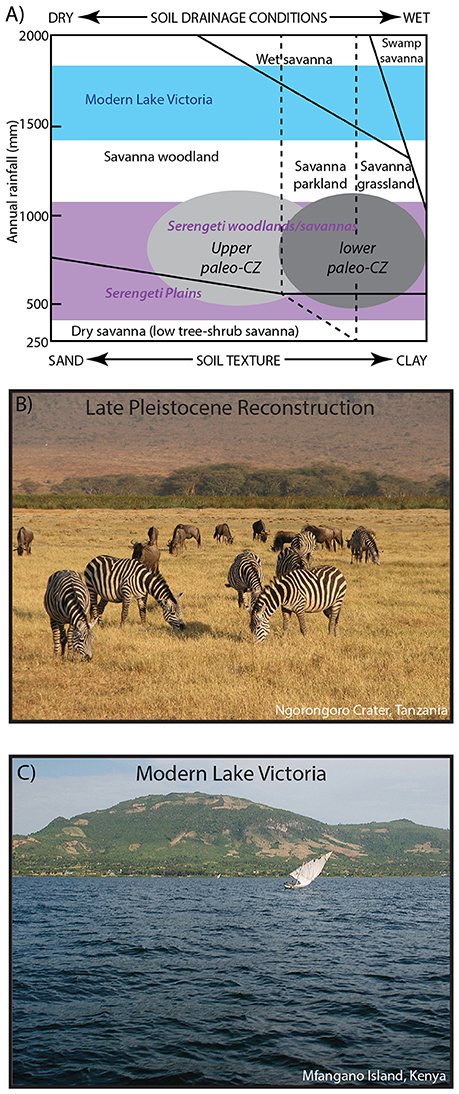

The tephrostratigraphy and our detailed analyses of the paleosols between tephra allows for the reconstruction of the landscape in the northeastern Lake Victoria Basin as a series of paleo-CZs. Below the Nyamita Tuff, the oldest paleo-CZ (P3) is dominated by well-developed paleo-Vertisols. The parallel, cross, and granostriated b-fabrics in the micromorphology and well-developed slickensides all indicate rainfall seasonality. Bulk geochemical pedotransfer functions for reconstructing Vertisol properties such as salinity, sodicity, pH, and cation exchange capacity were applied on the Kisaaka Vertisols and all indicate fertile soil with saline-sodic conditions that would have affected plant size or been limited to salt tolerant species (Beverly et al., 2015a). In modern African savanna ecosystems, vegetation is greatly affected by both vegetation and soil texture (sand vs. clay), and a simple abiotic model created by Johnson and Tothill (1985) can be used to predict the type of vegetation in paleosols (Wynn, 2000; Beverly et al., 2015a). Based on MAP estimates and a dominantly clay grain size, this lower paleo-CZ was a seasonally dry but fertile soil affected by high salinity and sodicity. Vegetation would have ranged from savanna grassland to savanna parkland (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. (A) The Johnson/Tothill model of tropical savannas, which shows that both MAP and soil texture have a predictable effect on vegetation. The reconstructed paleo-CZs from the northeastern shoreline of Lake Victoria indicate an environment similar to a modern savanna woodland, parkland, or grassland based on MAP and grain size of the paleosols. The range of Serengeti woodlands/savannas and the Serengeti Plains are indicated in purple as well as the range of modern Lake Victoria precipitation in blue. Reproduced with permission from Beverly et al. (2015a) and Johnson and Tothill (1985). (B) Modern analog for the paleo-CZs. A C4 dominated savanna grassland with arid-adapted fauna such as zebras and wildebeest. Photograph by J.T. Faith. (C) View of modern Mfangano Island from Lake Victoria. Photograph by C.A. Tryon. Historical vegetation in the Lake Victoria region was evergreen bushland, thicket, and forest habitats.

In the paleo-CZ overlying the Nyamita Tuff (P1 and P2), the pedotransfer functions for reconstructing soil properties were not applied because these paleosols were identified as paleo-Inceptisols, and this proxy is only applicable to paleo-Vertisols. However, the abundance of illuviated clay (3–5%) indicates seasonal precipitation where moderate rainfall falls on a dry soil. Similar ranges of MAP, but higher amounts of volcaniclastic or tuffaceous material in the upper paleo-CZ suggest a seasonally dry, savanna parkland to savanna woodland similar to that currently found in the broader Serengeti Ecosystem (Figure 3A).

These reconstructions of the upper and lower paleo-CZ using paleosol features, grain size, and bulk geochemical proxies for MAP also agree with vegetation reconstructions using pedogenic carbonates, soil organic matter, and tooth enamel from Rusinga and Mfangano Islands, which indicate the local occurrence of a woodland to grassy woodland surrounded by an expansive C4 grassland (Faith et al., 2015; Garrett et al., 2015; Tryon et al., 2016). The fossils from this region are dominated by a diverse population of grazing herbivores and arid-adapted ungulates such as oryx (Oryx beisa) and Grevy's zebra (Equus grevyi), which are found far outside their modern range of arid eastern and northeastern Africa (Faith et al., 2015).

All of these data indicate that an expansion of arid-adapted fauna and Serengeti-like grasslands likely occurred during the Late Pleistocene with the Serengeti as a reasonable modern analog (Figure 3B). This contrasts with the historic evergreen bushland, thicket, and forest habitats in the Lake Victoria region (Figure 3C; White, 1983). Vegetation models (Cowling et al., 2008) and phylogeographic observations derived from savannah ungulates (Lorenzen et al., 2012) predict that more open vegetation would have facilitated dispersals of mammal species, including humans, across equatorial east Africa, and the reduction in size of Lake Victoria, which would have removed a significant geographic barrier, is likely to have further enhanced dispersal potential. Importantly, many of the mammalian taxa that co-occur in fossil assemblages from Rusinga, Mfangano, and Karungu are allopatric today and historically, forming what Faith et al. (2015, 2016) refer to as “non-analog supercommunities,” comprised of taxa for which Lake Victoria currently serves as a major barrier. This includes, for example, the co-occurrence of white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum; historically northwest of the lake), Grevy's zebra (northeast of the lake), and southern reedbuck (Redunca arundinum: south of the lake). From this perspective, the absence of the lake and expansion of more open vegetation likely facilitated range expansions for these taxa. The fossil fauna co-occur with Middle Stone Age artifacts. The implication is that MSA-equipped humans also dispersed into the center of the basin with lake-level retreat. Reducing the effects of Lake Victoria as a biogeographic barrier for the movement of fauna would have encouraged, although not dictated, the dispersal of humans along the Nilotic corridor as an avenue for the movement of modern humans out of and within Africa between 94 and 36 ka (Tryon et al., 2016).

The results presented in this study indicate that the paleosols of the late Pleistocene deposits in the northeastern Lake Victoria Basin record a much drier climate (54–72% of modern MAP) along the northeastern coast of Lake Victoria during the Late Pleistocene (94–36 ka). The degree of development of paleosol features indicate that these soils likely represent a time-averaged, but relatively complete record of this interval. Paleosol features and bulk geochemistry indicate that the paleo-CZs were seasonally dry but fertile soils; however, high salinity and sodicity would likely have limited the vegetation to those tolerate of higher levels. Based on grain size and reconstructed MAP, these paleosols likely could support vegetation ranging from savanna woodland to grassland, which is very similar to modern Serengeti woodlands and savanna (Figure 3A) and starkly different from the historical evergreen bushland, thicket, and forest habitats (Figures 3B,C). This interpretation is consistent with evidence from stable isotopes from fossil teeth, pedogenic carbonates, and organic matter, all of which indicate a much drier environment dominated by C4 grasses. In addition, arid-adapted fossil fauna such as Grevy's zebra collected from the late Pleistocene deposits in the northeastern Lake Victoria Basin are far outside their known historical range. The formation of the paleosols also overlaps with desiccation surface identified from seismic surveys in Lake Victoria at ~80 ka (Stager and Johnson, 2008) and partially overlaps with the megadrought (135–70 ka) identified by Scholz et al. (2007) in Lakes Malawi, Tanganyika, and Bosumtwi. However, the extended aridity between 70 and 36 ka suggests that Lake Victoria responded differently to the shift to high-latitude forcing that caused the refilling of Lakes Malawi, Tanganyika, and Bosumtwi at ~70 ka. Low SSTs that weakened the monsoon may be responsible for low levels in Lake Victoria and similar to the record identified at Lake Naivasha (Bard et al., 1997; Trauth et al., 2003). Previous models of Lake Victoria indicate that this decrease in rainfall would have greatly reduced the surface area of Lake Victoria to <20% of modern and would have lessened the effects of Lake Victoria as a biogeographic barrier to humans and other fauna. The simultaneous reduction in size of Lake Victoria and expansion of grasslands would have enhanced the Nilotic corridor as an avenue for human dispersal within and out of Africa between 94 and 36 ka.

DP, JF, and CT developed the Lake Victoria Prehistory Project. EB described the paleosols from Karungu and Rusinga, conducted all paleosol analyses, and wrote the manuscript. DP described and collected paleosols from Mfangano. SD contributed to micromorphological and paleopedological interpretations of paleo-Vertisols, as well as to paleo-Critical Zone concepts. GS applied the PPM1.0 model to the bulk geochemical data. DP, JF, CT, EB, and NB conducted geological, paleontological, and archeological analyses at all sites. All authors edited and approved the manuscript.

This research was funded by the National Geographic Society Committee for Research and Exploration (9284-13 and 8762-10), the National Science Foundation (BCS-1013199 and BCS-1013108), the Leakey Foundation, the Geological Society of America, the Society for Sedimentary Geology (SEPM), the University of Queensland, Baylor University, the Baylor University Department of Geology Dixon Fund, New York University, Harvard University, and the American School for Prehistoric Research.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This research was originally published as a chapter in a dissertation by EB (Beverly, 2015). Fieldwork at Rusinga Island and Karungu was conducted under research permits NCST/5/002/R/605 issued to EB, NCST/RCD/12B/012/31 issued to JF, NCST/5/002/R605 issued to SD, NCST/5/002/R/576 issued to CT, and NCST/RCD/12B/01/07 issued to DP. We also greatly appreciate the support of the National Museum of Kenya (NMK), especially Drs. E. Mbua and F. Manthi. We also greatly appreciate the assistance of S. Longoria of the NMK and Z. Ogutu in the field, and Baylor undergraduates L. N. Arellano and W. Horner.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feart.2017.00093/full#supplementary-material

Allsopp, R., and Baldry, D. A. T. (1972). A general description of the Lambwe Valley area of South Nyanza District, Kenya. Bull. World Health Organ. 47, 691–697.

Ambrose, S. H., and Lorenz, K. G. (1990). “Social and ecological models for the Middle Stone Age in Southern Africa,” in The Emergence of Modern Humans: and Archaeological Perspective, ed P. Mellars (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 3–33.

Amundson, R., Richter, D. D., Humphreys, G. S., Jobbagy, E. G., and Gaillardet, J. (2007). Coupling between biota and earth materials in the Critical Zone. Elements 3, 327–332. doi: 10.2113/gselements.3.5.327

Andrews, P. (1973). Vegetation of Rusinga Island. J. East Afr. Nat. Hist. Soc. Natl. Museums 142, 1–8.

Bard, E., Rostek, F., and Sonzogni, C. (1997). Interhemispheric synchrony of the last deglaciation inferred from alkenone palaeothermometry. Nature 385, 707–710. doi: 10.1038/385707a0

Berke, M. A., Johnson, T. C., Werne, J. P., Grice, K., Schouten, S., and Sinninghe Damsté, J. S. (2012). Molecular records of climate variability and vegetation response since the Late Pleistocene in the Lake Victoria Basin, East Africa. Quat. Sci. Rev. 55, 59–74. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.08.014

Beverly, E. J. (2015). Reconstruction of Late Pleistocene Paleoenvironments of the Lake Victoria Region Using Paleosols and Freshwater Tufa. Waco, TX: Baylor University, 212.

Beverly, E. J., Driese, S. G., Peppe, D. J., Arellano, L. N., Blegen, N., Tyler Faith, J., et al. (2015a). Reconstruction of a semi-arid late pleistocene paleocatena from the Lake Victoria region, Kenya. Quat.Res. 84, 368–381. doi: 10.1016/j.yqres.2015.08.002

Beverly, E. J., Driese, S. G., Peppe, D. J., Johnson, C. R., Michel, L. A., Faith, J. T., et al. (2015b). Recurrent spring-fed rivers in a Middle to Late Pleistocene semi-arid grassland: implications for environments of early humans in the Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya. Sedimentology 62, 1611–1635. doi: 10.1111/sed.12199

Blegen, N., Brown, F. H., Jicha, B. R., Binetti, K. M., Faith, J. T., Ferraro, J. V., et al. (2016). The Menengai Tuff: A 36 ka widespread tephra and its chronological relevance to Late Pleistocene human evolution in East Africa. Quat. Sci. Rev. 152, 152–168. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.09.020

Blegen, N., Faith, J. T., Mant-Melville, A., Peppe, D. J., and Tryon, C. A. (in press). The Middle Stone Age after 50,000 years ago: new evidence from the late pleistocene sediments of the eastern Lake Victoria Basin, western Kenya. Paleo Anthropol.

Blegen, N., Tryon, C. A., Faith, J. T., Peppe, D. J., Beverly, E. J., Li, B., and Jacobs, Z. (2015). Distal tephras of the eastern Lake Victoria basin, equatorial East Africa: correlations, chronology, and a context for early modern humans. Quart. Sci. Rev. 122, 89–111. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.04.024

Blome, M. W., Cohen, A. S., Tryon, C. A., Brooks, A. S., and Russell, J. (2012). The environmental context for the origins of modern human diversity: a synthesis of regional variability in African climate 150,000-30,000 years ago. J. Hum. Evol. 62, 563–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.01.011

Bootsma, H. A., and Hecky, R. E. (2003). A comparative introduction to the biology and limnology of the African Great Lakes. J. Great Lakes Res. 29, 3–18. doi: 10.1016/S0380-1330(03)70535-8

Brantley, S. L., Goldhaber, M. B., and Ragnarsdottir, K. V. (2007). Crossing disciplines and scales to understand the Critical Zone. Elements 3, 307–314. doi: 10.2113/gselements.3.5.307

Broecker, W. S., Peteet, D., Hajdas, I., Lin, J., and Clark, E. (1998). Antiphasing between rainfall in Africa's rift valley and North America's Great Basin. Quat. Res. 50, 12–20. doi: 10.1006/qres.1998.1973

Brown, F. H., McDougall, I., and Fleagle, J. G. (2012). Correlation of the KHS tuff of the Kibish Formation to volcanic ash layers at other sites, and the age of early homo sapiens (Omo, I., and Omo II). J. Hum. Evol. 63, 577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.05.014

Castañeda, I. S., Werne, J. P., and Johnson, T. C. (2007). Wet and arid phases in the southeat African tropics since the Last Glacial Maximum. Geology 35, 823–826. doi: 10.1130/G23916A.1

Clement, A. C., Hall, A., and Broccoli, A. J. (2004). The importance of precessional signals in the tropical climate. Clim. Dyn. 22, 327–341. doi: 10.1007/s00382-003-0375-8

Cowling, S. A., Cox, P. M., Jones, C. D., Maslin, M. A., Peros, M., and Spall, S. A. (2008). Simulated glacial and interglacial vegetation across Africa: implications for species phylogenies and trans-African migration of plants and animals. Global Change Biol. 14, 827–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01524.x

Dere, A. L., White, T. S., April, R. H., and Brantley, S. L. (2015). Mineralogical transformations and soil development in shale across a latitudinal climosequence. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 80, 623–636. doi: 10.2136/sssaj2015.05.0202

Driese, S. G., Mora, C. I., Stiles, C. A., Joeckel, R. M., and Nordt, L. C. (2000). Mass-balance reconstruction of a modern Vertisol: implications for interpreting the geochemistry and burial alteration of paleo-Vertisols. Geoderma 95, 179–204. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7061(99)00074-9

Faith, J. T., Choiniere, J. N., Tryon, C. A., Peppe, D. J., and Fox, D. L. (2011). Taxonomic status and paleoecology of Rusingoryx atopocranion (Mammalia, Artiodactyla), an extinct Pleistocene bovid from Rusinga Island, Kenya. Quat. Res. 75, 697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.yqres.2010.11.006

Faith, J. T., Potts, R., Plummer, T. W., Bishop, L. C., Marean, C. W., and Tryon, C. A. (2012). New perspectives on middle Pleistocene change in the large mammal faunas of East Africa: Damaliscus hypsodon sp. nov. (Mammalia, Artiodactyla) from Lainyamok, Kenya. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 361–362, 84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.08.005

Faith, J. T., Tryon, C. A., and Peppe, D. J. (2016). “Environmental change, ungulate biogeography, and their implications for early human dispersals in equatorial East Africa,” in Africa from MIS 6-2: Population Dynamics and Paleoenvironments, eds S. C. Jones and B. A. Stewart (Dordrecht: Springer), 233–245.

Faith, J. T., Tryon, C. A., Peppe, D. J., Beverly, E. J., and Blegen, N. (2014). Biogeographic and Evolutionary Implications of an Extinct Late Pleistocene Impala from the Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya. J. Mammal. Evol. 21, 213–222. doi: 10.1007/s10914-013-9238-1

Faith, J. T., Tryon, C. A., Peppe, D. J., Beverly, E. J., Blegen, N., Blumenthal, S., et al. (2015). Paleoenvironmental context of the Middle Stone Age record from Karungu, Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya, and its implications for human and faunal dispersal in East Africa. J. Hum. Evol. 83, 28–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.03.004

Garrett, N. D., Fox, D. L., Mcnulty, K. P., Tryon, C. A., Faith, J. T., Peppe, D. J., et al. (2015). Stable isotope paleoecology of Late Pleistocene Middle Stone Age humans from the equatorial East Africa, Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 82, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.10.005

Gasse, F. (2000). Hydrological changes in the African tropics since the Last Glacial Maximum. Quat. Sci. Rev. 19, 189–211. doi: 10.1016/S0277-3791(99)00061-X

Ivory, S. J., Blome, M. W., King, J. W., McGlue, M. M., Cole, J. E., and Cohen, A. S. (2016). Environmental change explains cichlid adaptive radiation at Lake Malawi over the past 1.2 million years. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 11895–11900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611028113

Jenkins, K. E., Nightingale, S., Faith, J. T., and Peppe, D. J. (2017). Evaluating the potential for tactical hunting in the Middle Stone Age: insights from a MSA bonebed of the extinct bovid, Rusingoryx atopocranion. J. Hum. Evol. 108, 72–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.11.004

Johnson, R. W., and Tothill, J. C. (1985). “Definition and broad geographic outline of savanna lands,” in Ecology and Management of the World's Savannas, eds J. C. Tothill and J. J. Mott (Canberra, CA: Australian Academy of Science), 1–13.

Kent, P. E. (1942). The country round the Kavirondo Gulf of Victoria Nyanza. Geogr. J. 100, 22–31. doi: 10.2307/1789231

Kimanzi, J. K. (2011). Mapping and Modeling the Population and habitat of Roan Antelope (Hippotragus Equinus Langheldi) in Ruma National Park. Newcastle upon Tyne: Newcastle University.

Laskar, J., Robutel, P., Joutel, F., Gastineau, M., Correia, A. C. M., and Levrard, B. (2004). A long-term numerical solution for the insolation quantities of the earth. Astron. Astrophys. 428, 261–285. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361:20041335

Levin, N. E. (2015). Environment and climate of early human evolution. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 43, 405–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev-earth-060614-105310

Lorenzen, E. D., Heller, R., and Siegismund, H. R. (2012). Comparative phylogeography of African savannah ungulates. Mol. Ecol. 21, 3656–3670. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05650.x

Lyons, R. P., Scholz, C. A., Cohen, A. S., King, J. W., Brown, E. T., Ivory, S. J., et al. (2015). Continuous 1.3-million-year record of East African hydroclimate, and implications for patterns of evolution and biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 2–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512864112

McDougall, I., Brown, F. H., and Fleagle, J. G. (2005). Stratigraphic placement and age of modern humans from Kibish, Ethiopia. Nature 433, 733–736. doi: 10.1038/nature03258

Milly, P. C. D. (1999). Comment on “antiphasing between rainfall in Africa's Rift Valley and North America's Great Basin”. Quat. Res. 51, 104–107. doi: 10.1006/qres.1998.2011

Nicholson, S. E. (1996). “A review of climate dynamics and climate variability in Eastern Africa,” in The Limnology, Climatology and Paleoclimatology of the East African Lakes, eds T. C. Johnson and E. O. Odada (Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach Publishers), 25–56.

Nordt, L. C., and Driese, S. G. (2010). New weathering index improves paleorainfall estimates from Vertisols. Geology 38, 407–410. doi: 10.1130/G30689.1

Nordt, L. C., and Driese, S. G. (2013). Application of the Critical Zone concept to the deep-time sedimentary record. Sediment. Record 11, 4–9. doi: 10.2110/sedred.2013.3.4

Oswald, F. (1914). The Miocene Beds of the Victoria Nyanza and the geology of the country between the lake and the Kisii Highlands. Quat. J. Geol. Soc. 70, 128–159. doi: 10.1144/GSL.JGS.1914.070.01-04.10

Partridge, T. C., Demenocal, P. B., Lorentz, S. A., Paiker, M. J., and Vogel, J. C. (1997). Orbital forcing of climate over South Africa: a 200,000-year rainfall record from the Pretoria Saltpan. Quat. Sci. Rev. 16, 1125–1133.

Pickford, M. H. (1984). An aberrant new bovid (Mammalia) in subrecent deposits from Rusinga Island, Kenya. Procceeding Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie Van Wetenschappen Series B Palaeontol. Geol. Phys. Chem. Anthropol. 87, 441–452.

Potts, R. (1998). Environmental hypotheses of hominin evolution. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 107, 93–136. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(1998)107:27+<93::AID-AJPA5>3.0.CO;2-X

Potts, R., and Faith, J. T. (2015). Alternating high and low climate variability: the context of natural selection and speciation in Plio-Pleistocene hominin evolution. J. Hum. Evol. 87, 5–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.06.014

National Research Council (2001). Basic Research Opportunities in Earth Science. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Richter, D., Grün, R., Joannes-Boyau, R., Steele, T. E., Amani, F., Rué, M., et al. (2017). The age of the hominin fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, and the origins of the Middle Stone Age. Nature 546, 293–296. doi: 10.1038/nature22335

Rito, T., Richards, M. B., Fernandes, V., Alshamali, F., Cerny, V., Pereira, L., and Soares, P. (2013). The first modern human dispersals across Africa. PLoS ONE 8:e80031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080031

Scholz, C. A., Johnson, T. C., Cohen, A. S., King, J. W., Peck, J. A., Overpeck, J. T., et al. (2007). East African megadroughts between 135 and 75 thousand years ago and bearing on early-modern human origins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 16416–16421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703874104

Sheldon, N. D., Retallack, G. J., and Tanaka, S. (2002). Geochemical climofunctions from North America soils and applications to paleosols across the Eocene-Oligocene Boundary in Oregon. J. Geol. 110, 687–696. doi: 10.1086/342865

Sheldon, N. D., and Tabor, N. J. (2009). Quantitative paleoenvironmental and paleoclimatic reconstruction using paleosols. Earth Sci. Rev. 95, 1–52. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2009.03.004

Soares, P., Alshamali, F., Pereira, J. B., Fernandes, V., Silva, N. M., Afonso, C., et al. (2012). The expansion of mtDNA haplogroup L3 within and out of Africa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 915–927. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr245

Stager, J. C., and Johnson, T. C. (2008). The Late Pleistocene desiccation of Lake Victoria and the origin of its endemic biota. Hydrobiologia 596, 5–16. doi: 10.1007/s10750-007-9158-2

Stager, J. C., Ryves, D. B., Chase, B. M., and Pausata, F. S. R. (2011). Catastrophic drought in the Afro-Asian monsoon region during Heinrich Event 1. Science 331, 1299–1302. doi: 10.1126/science.1198322

Stinchcomb, G. E., Nordt, L. C., Driese, S. G., Lukens, W. E., Williamson, F. C., and Tubbs, J. D. (2016). A data-driven spline model designed to predict paleoclimate using paleosol geochemistry. Am. J. Sci. 316, 746–777. doi: 10.2475/08.2016.02

Stoops, G. (2003). Guidelines for Analysis and Description of Soil and Regolith Thin Sections. ed M. J. Vepraskas (Madison, WI: Soil Science Society of America, Inc.).

Sutcliffe, J. V., and Parks, Y. P. (1999). The Hydrology of the Nile. Vol. 5. Reading: IAHS Special Publication.

Tabor, N. J., and Myers, T. S. (2015). Paleosols as indicators of paleoenvironment and paleoclimate. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 43, 11.1–11.29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-earth-060614-105355

Tierney, J. E., deMenocal, P. B., and Zander, P. D. (2017). A climatic context for the out-of-Africa migration. Geology 45, 1023–1026. doi: 10.1130/G39457.1

Trauth, M. H., Deino, A. L., Bergner, A. G. N., and Strecker, M. R. (2003). East African climate change and orbital forcing during the last 175 kyr BP. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 206, 297–313. doi: 10.1016/S0012-821X(02)01105-6

Tryon, C. A., Faith, J. T., Peppe, D. J., Beverly, E. J., Blegen, N., Blumenthal, S. A., et al. (2016). The Pleistocene prehistory of the Lake Victoria Basin. Quat. Int. 404, 100–114. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.073

Tryon, C. A., Peppe, D. J., Faith, J. T., Van Plantinga, A., Nightingale, S., Ogondo, J., et al. (2012). Late Pleistocene artefacts and fauna from Rusinga and Mfangano Islands, Lake Victoria, Kenya. Azania: Arch. Res. Afr. 47, 14–38. doi: 10.1080/0067270X.2011.647946

Tryon, C. A., Faith, J. T., Peppe, D. J., Fox, D. L., McNulty, K. P., Jenkins, K., et al. (2010). The Pleistocene archaeology and environments of the Wasiriya Beds, Rusinga Island, Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 59, 657–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.07.020

Tryon, C. A., Faith, J. T., Peppe, D. J., Keegan, W. F., Keegan, K. N., Jenkins, K. H., et al. (2014). Sites on the landscape: paleoenvironmental context of Late Pleistocene archaeological sites from the Lake Victoria Basin, equatorial East Africa. Quat. Int. 331, 20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2013.05.038

Ufnar, D. (2007). Clay coatings from a modern soil chronosequence: a tool for estimating the relative age of well-drained paleosols. Geoderma 141, 181–200. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2007.05.017

Van Couvering, J. A. (1972). Geology of Rusinga Island And Correlation of The Kenya Mid-Tertiary Fauna, Vol. 208. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Van Plantinga, A. A. (2011). Geology of the Late Pleistocene Artifact-Bearing Wasiriya Beds At The Nyamita Locality, Rusinga Island, Kenya, Vol. 97. Waco, TX: Baylor Unviersity.

White, F. (1983). Vegetation of Africa: A descriptive memoir to accompany the Unesco/AETFAT/UNSO vegetation of Africa. Paris: UNESCO.

White, T., Brantley, S., Banwart, S., Chorover, J., Dietrich, W., Derry, L., et al. (2015). The Role of Critical Zone Observatories in Critical Zone Science. Amsterdam: Elsevier, BV.

Whitworth, T. (1961). The geology of Mfwanganu Island, western Kenya. Overseas Geol. Mineral Res. 8, 150–192.

Wynn, J. G. (2000). Paleosols, stable carbon isotopes, and paleoenvironmental interpretation of Kanapoi, Northern Kenya. J. Hum. Evol. 39, 411–432. doi: 10.1006/jhev.2000.0431

Keywords: human evolution, East Africa, paleoclimate, semi-arid, grassland, paleo-Critical Zone

Citation: Beverly EJ, Peppe DJ, Driese SG, Blegen N, Faith JT, Tryon CA and Stinchcomb GE (2017) Reconstruction of Late Pleistocene Paleoenvironments Using Bulk Geochemistry of Paleosols from the Lake Victoria Region. Front. Earth Sci. 5:93. doi: 10.3389/feart.2017.00093

Received: 31 July 2017; Accepted: 31 October 2017;

Published: 21 November 2017.

Edited by:

David K. Wright, Seoul National University, South KoreaReviewed by:

Yingkui Li, University of Tennessee, United StatesCopyright © 2017 Beverly, Peppe, Driese, Blegen, Faith, Tryon and Stinchcomb. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Emily J. Beverly, ZWJldmVybHlAdW1pY2guZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.