- 1Department of Anthropology, Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA, United States

- 2Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, Castro Valley, CA, United States

- 3Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

- 4Department of Anthropology, San Jose State University, San Jose, CA, United States

- 5Department of Anthropology, Foothill College, Los Altos Hills, CA, United States

The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe has long been involved in the archaeology and stewardship of their ancestral homelands, both through their own cultural resource management (CRM) firm and though collaborations with academic and CRM archaeologists. In this article, we build on the past 40 years of archaeological collaborations in the southern San Francisco Bay region and offer examples of how archaeologists can support tribal heritage and environmental stewardship by using the traditional purview of material culture in combination with a broader array of evidence and concerns. As presented in our brief case studies, the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe and scholars are working together to reclaim tribal heritage and promote Native stewardship in a cultural landscape that has been marred by more than 250 years of dispossession. We examine this work in the context of the renaming of ancestral sites, the public interpretation of Native heritage associated with Mission Santa Clara de Asís, archival research into the history of Indigenous resistance, as well as collaborative efforts to awaken traditional ecological knowledge in service of the Tribe's stewardship and land management goals.

1 Introduction

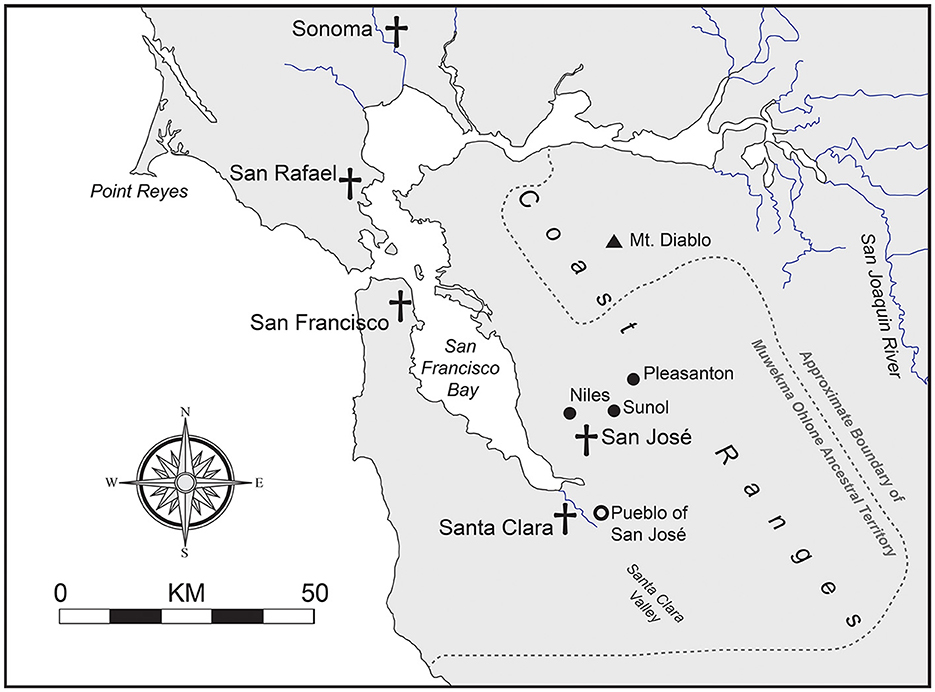

In this article, we focus on the Indigenous stewardship of cultural landscapes and heritage in one of the United States' largest metropolitan areas. The homelands of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe encompass much of the San Francisco Bay Area of central California, which today has a population of nearly eight million people (Figure 1). Though the history of Euro-American colonization in this region is relatively short—beginning in earnest in the 1770s—the compounding effects of missionary and settler colonialism have resulted in a “politics of erasure” that have left the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe landless, without recognition by the United States federal government, and increasingly gentrified out of their ancestral territories (Field et al., 2013). Despite these obstacles, the Tribe has worked diligently for several decades to protect ancestral sites, reclaim heritage, and to seek ways to steward their homelands. Archaeologists are working with and for the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe on many of these efforts, even as specific projects expand beyond the purview of traditional archaeology. This work is driven by shared commitment to collaboratively addressing critical issues that are rooted in traditional practices and historical injustices. To highlight both the challenges and opportunities of this work, we offer a sample of recent academic-tribal partnerships in the southern San Francisco Bay region.

In thinking about how archaeology can contribute to the Tribe's efforts to protect heritage sites and steward its ancestral homelands, it is critical to recognize that Muwekma Ohlone leaders and the broader Ohlone community have been involved in this work for many decades—longer, in fact, than the current trend toward collaborative and community-based approaches among many non-Native archaeologists (e.g., Cambra et al., 1996; Field et al., 2007). Still, inasmuch as the interrelated projects described below follow the interests and direction of the Tribe, we broadly position our work as contributing to ongoing shifts toward archaeologies centered on principles of community engagement, social justice, and Indigenous sovereignty (Schneider and Hayes, 2020; Nelson, 2021; Laluk et al., 2022; Little, 2023; Montgomery and Fryer, 2023). Particularly as educators, we wish to instill these ethics in the students that we train to become the next generation of archaeologists while simultaneously working toward a future where “archaeology and related heritage practices can be put to work effectively supporting things that matter beyond the small circles of our disciplines” (Fryer and Dedrick, 2023, p. 335).

2 Historical background

As in other regions of the world, the colonial history of the San Francisco Bay region has important implications for tribal sovereignty, heritage, and environmental stewardship. Ohlone people lived in the region for thousands of years before the onset of Spanish colonialism in the late 18th century, when Franciscan missionaries founded Missions San Francisco (1776), Santa Clara (1777), and San José (1797) (see Figure 1). During this time, thousands of Ohlone people were forced off their homelands and into the missions, non-native plants and animals spread throughout the region, and colonial authorities outlawed Indigenous landscape management practices such as cultural burning (Milliken, 1995; Lightfoot et al., 2013; Panich, 2020). Beginning in the 1830s and 1840s, many Ohlone ancestors were emancipated from the missions, and some even overcame structural barriers to receive land grants from the Mexican government, enabling them to return to their ancestral homelands as free citizens. Many other Native families and individuals simply walked away from the missions to return to home or to create new lives in the Pueblo of San José (today the city of San Jose) and various ranchos throughout the region (Shoup and Milliken, 1999; Panich, 2019).

In the late 1840s, however, the annexation of California by the United States marked the transition to settler colonialism and with it came a new wave of dispossession and outright genocide (Lindsay, 2012; Madley, 2016). Pushed off of the former mission lands and later settlements, members of the lineages that comprise the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe regrouped in the southeastern Bay Area where they coalesced in the closely intertwined settlements of Niles, Sunol, and Alisal (near present-day Pleasanton). This community was recognized by the United States federal government in the early 20th century, though they only had a tenuous hold on the land. The Bureau of Indian Affairs sought to alleviate the conditions of landless California Indians but ultimately ignored the ancestors of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe due to the negligence of a single Indian agent in the mid-1920s. Around this same time, the Ohlone community was similarly written off by anthropology when Kroeber (1925, p. 464) stated that they were “extinct, so far as all practical purposes are concerned” (and see Leventhal et al., 1994; Field, 1999; Panich, 2020; Barron, 2022).

These injustices continue to reverberate a century later. Though the tribe was never terminated, the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe—now numbering more than 600 members—is today not among the 574 tribes recognized by the US federal government. As a previously unambiguously recognized tribe, the Muwekma Ohlone are seeking the restoration of their federal status and resist the politics of erasure in various ways, including their active involvement in the archaeology and stewardship of their ancestral homelands.

3 Tribal involvement in archaeology

The excavation of Muwekma Ohlone ancestral sites—by both academic and amateur archaeologists—has a long history. Some of the earliest professional investigations in the region centered on the monumental shellmounds that Ohlone ancestors and other Native Californians constructed along the margins of the San Francisco Bay and neighboring bodies of water. Most of the major mounds, such as Emeryville Shellmound, were excavated in the early 1900s and have been repeatedly disturbed—and in some cases totally destroyed—over the course of the following decades (Lightfoot et al., 2017). Not even more recent sites were spared the destruction. Native burials at Mission Santa Clara, for example, were disturbed by construction activities several times in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with rampant collection of human remains and associated funerary belongings by a range of individuals and organizations (Panich, 2022). Across the region, hundreds of other ancestral sites were damaged or destroyed by agriculture, construction, or archaeological activities in the first several decades of the 20th century.

The 1960s marked a major turning point in cultural resource law with the implementation of National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, and the California Environmental Quality Act of 1970. Yet, even before the passage of these laws, the Ohlone community banded together in 1964 to preserve a cemetery originally associated with Mission San José that had long been an important burying ground for Ohlone families. This action by the Ohlone community saved the site, known today as the Ohlone Indian Cemetery, from being destroyed during the construction of Interstate 680 (Milliken et al., 2009, p. 224–225; Medina, 2015). Still, the extensive urban and suburban development of the San Francisco Bay region during the 1960s and 1970s meant that scores of ancestral sites continued to be disturbed, even if nominally protected by cultural resource laws.

However, because the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe is not currently federally recognized, the Tribe's participation in CRM archaeology is limited by legal statute (Becks, 2015). In response to the continued threats to ancestral sites in the 1980s, the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe created its own cultural resource management firm, the Ohlone Families Consulting Services, which has recently been reorganized to fit directly into the organizational structure of the Tribe. Similar legal obstacles hinder the ability of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe—like other unrecognized tribes—to request the repatriation of ancestors or associated belongings through the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) process. In contrast, the California Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (CalNAGPRA) does allow for repatriation to non-recognized tribes, though the process has yet to be fully completed at most Bay Area institutions and it will take time to identify the extent of existing collections from ancestral Ohlone sites created by previous academic and CRM projects. In recognition of these inequities, Stanford University voluntarily repatriated some 700 ancestors to the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe before the passage of NAGPRA in 1990, setting an important national precedent (Kakaliouras, 2012, p. 215).

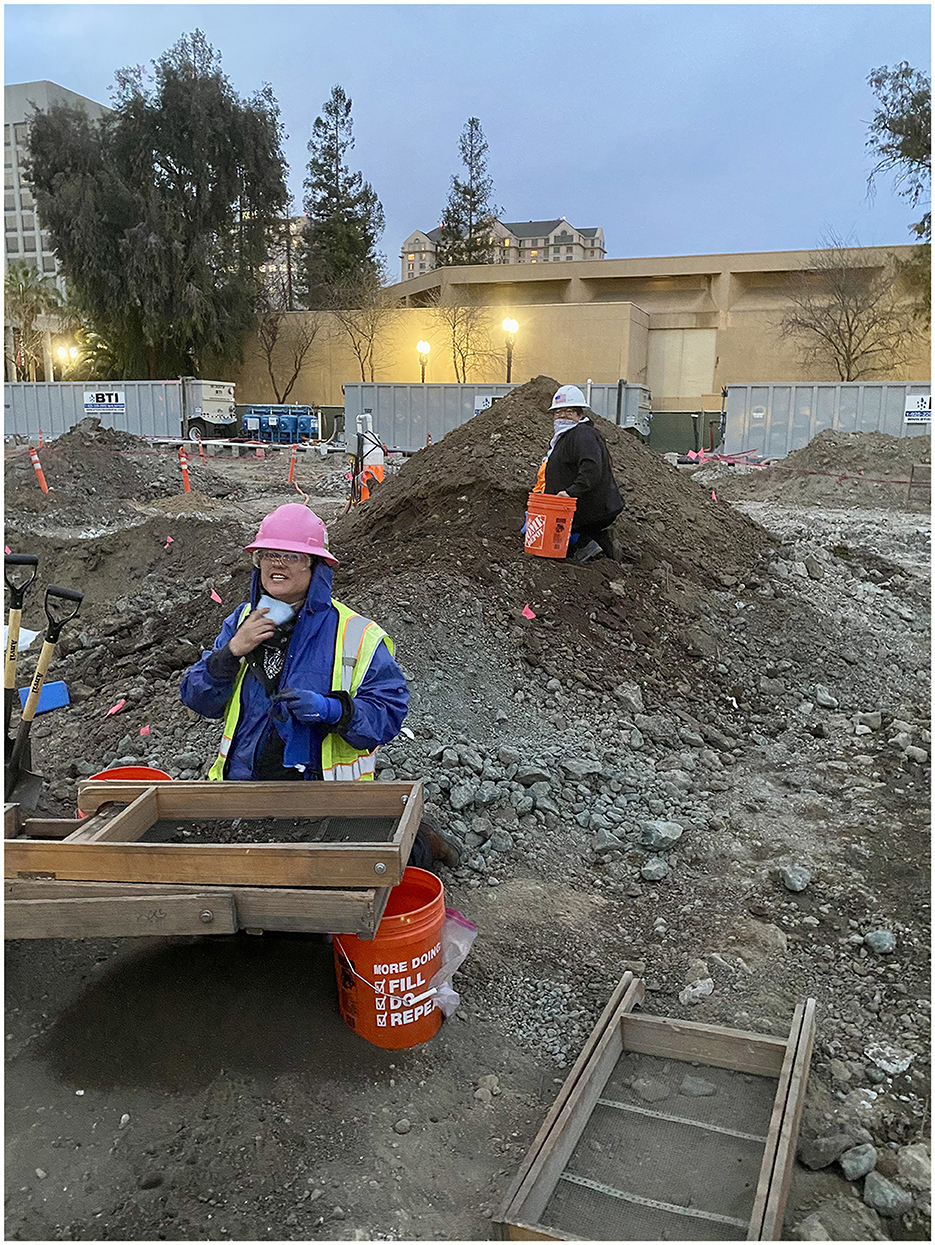

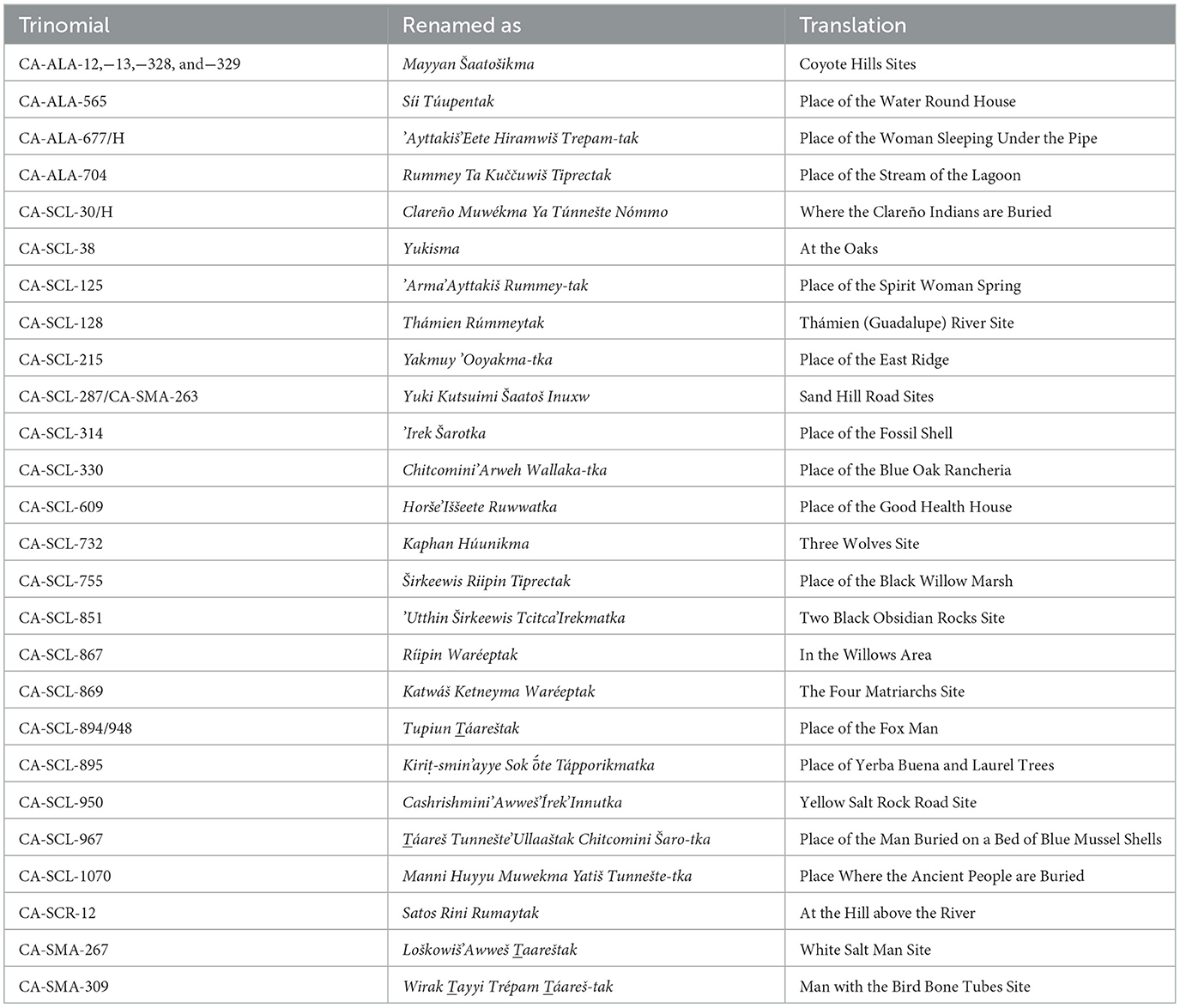

Since the mid-1980s, the Tribe's participation in archaeology has offered opportunities for tribal members to help protect ancestral sites, to participate in archaeological research, and to combat the narratives of extinction that continue to plague the Tribe (Figures 2, 3). For example, direct tribal involvement in CRM archaeology has allowed the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe's Language Committee to rename impacted sites in their ancestral Chochenyo Ohlone language. To date, the Tribe has renamed approximately two dozen sites across the region, including locales in Alameda, San Mateo, Santa Clara, and Santa Cruz counties (Table 1). This practice is a powerful rejoinder to archaeologists who would presume to see ancestral Ohlone sites as their own sources of data (named either by impersonal alphanumerical systems and/or site names that memorialize settler land owners). This practice of renaming also rhetorically signals to broader audiences that Muwekma Ohlone people still exist today in the region, just as they have for thousands of years.

Figure 2. Members of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe participating in a data recovery mitigation at an ancestral site in San Jose, California. Monica V. Arellano (foreground) sifts sediments while Laura Padron checks the spoils pile. Photo by Monica V. Arellano.

Figure 3. Tribal member Gloria Gomez (left) monitors backhoe work at an ancestral site in San Jose, California. Photo by Monica V. Arellano.

Table 1. Archaeological sites renamed in the Chochenyo Ohlone language by the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe's Language Committee.

The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe's longstanding presence has given them substantial control over how and when they collaborate with academic and CRM archaeologists, resulting in fruitful relationships with a range of institutions and CRM firms who agree to abide by the research goals and protocols determined by the Tribe (Monroe et al., 2022). For example, a recent mitigation project in the town of Sunol involved a productive relationship with Far Western Anthropological Research Group and other archaeologists. The partnership resulted in multiple co-authored journal articles, a monograph, as well as a PBS documentary, “Time Has Many Voices: The Excavation of a Muwekma Ohlone Village,” in which the history of their people is told through the lens of an excavation and its resultant analysis (Byrd et al., 2022). During this project, the Tribe made the decision to proceed with ancient DNA studies that conclusively linked living tribal members to ancestors who were laid to rest hundreds of years ago, a study that received widespread media attention (Severson et al., 2022). The Tribe also regularly supports doctoral dissertations and masters theses conducted by students at local universities (e.g., Becks, 2018; Ragland, 2018). While not all tribes or descendant communities have the same approach, being involved in archaeology allows the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe to ensure that research regarding their ancestors and heritage proceeds in a respectful and ethical manner.

In the following sections, we highlight our interrelated projects that build on this strong foundation to support the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe's efforts to counter the politics of erasure and restore tribal sovereignty over heritage and the environment.

4 Reclaiming colonial spaces

In addition to reclaiming ancient sites, the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe is drawing on archaeological findings to reframe the relationship between its ancestors and the California mission system (ca. 1769–1840s). At one level, is difficult to overstate the negative impacts of the Spanish missions on the Indigenous peoples of California. Tens of thousands were forced from their homelands to the missions, where strict social controls, crushing labor demands, and the suppression of traditional practices led to a catastrophic loss of life. Yet, Native Californians fought hard to maintain their communities and their connections to their ancestral territories, often in ways that are ignored in traditional historical narratives (Panich and Schneider, 2014; Hull and Douglass, 2018). In public interpretations of mission sites, however, this tension between struggle and persistence is often overshadowed by public memory that celebrates the European origins of the missions while largely overlooking the experiences of Native Californians (Dartt-Newton, 2011; Kryder-Reid, 2016; Panich, 2016, 2022).

At Mission Santa Clara—on the campus of Santa Clara University (SCU)—tribal members have been working with archaeologists and other scholars to reclaim Native heritage. The Tribe has been involved with the campus museum, the de Saisset, for decades and, in their capacity as the state-designated most likely descendants (MLDs), tribal members have aided in the recovery of several ancestors buried on and near the university. Many of those ancestors lived during pre-contact times—dating back at least 2,500 years—and were laid to rest in an area that is today the center of the SCU campus (e.g., Leventhal et al., 2023). Others were associated with Mission Santa Clara, including individuals buried in the third mission cemetery (ca. 1781–1818). The California Department of Transportation consulted with the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe during an early project at the cemetery (Hylkema, 1995, p. 9–10), and later the Tribe led the excavation and reburial of several individuals who were disturbed during gas line maintenance in 2009. As noted in Table 1, the Tribe's Language Committee renamed this cemetery as Clareño Muwékma Ya Túnnešte Nómmo at the completion of that particular project (Leventhal et al., 2011). Despite these connections, the Tribe's involvement in archaeological fieldwork at and near Mission Santa Clara has been largely limited to burial recoveries in a CRM context. Outside of the de Saisset Museum, very little public interpretation exists on the SCU campus that speaks to the rich and complex histories of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe or other Native peoples of central California who were present on this land before, during, and after the mission period. In other words, Native heritage has been largely erased for the tens of thousands of people who each year pass through the SCU campus as visitors, students, staff, or faculty.

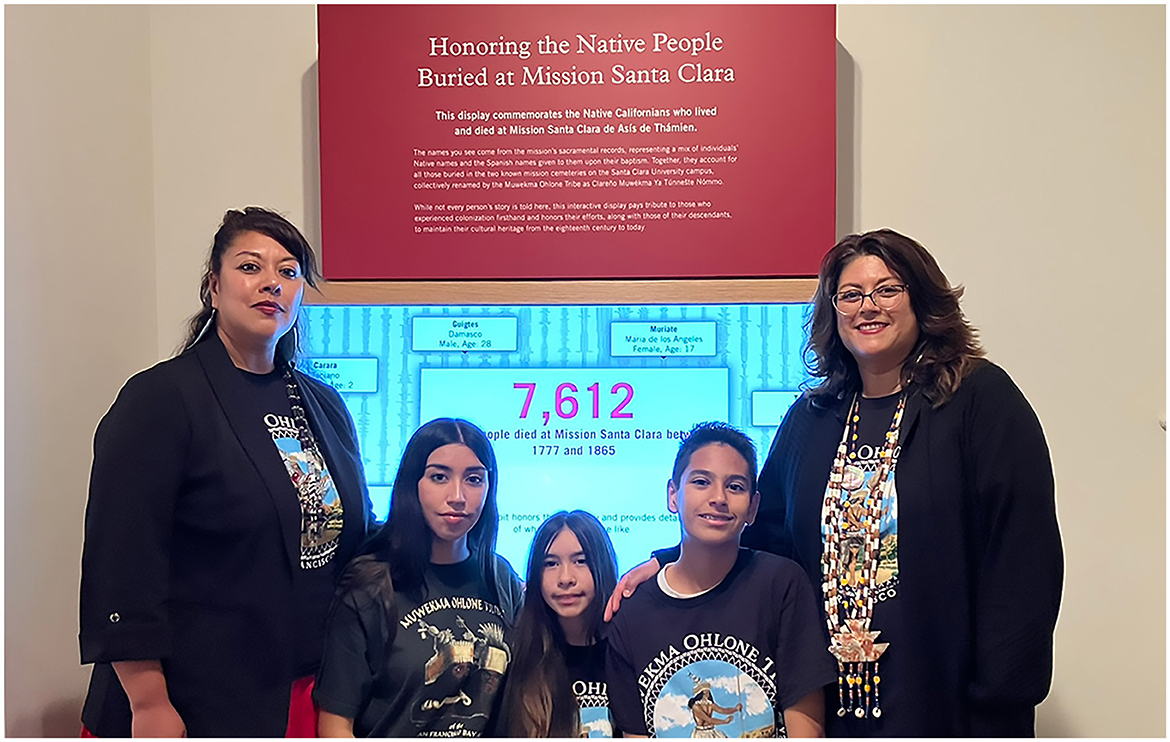

Given this situation, SCU's leadership convened the Ohlone History Working Group in 2019 to conduct a campus-wide assessment of monuments and markers and make recommendations for better integrating Ohlone heritage into the interpretive apparatus at Mission Santa Clara and across the SCU campus (Baines et al., 2020). The working group was staffed by Ohlone representatives and SCU personnel, including Muwekma Ohlone Chairwoman Charlene Nijmeh and Lee Panich, coauthor of this paper. One of the highest priorities identified by the working group was to formally recognize the thousands of Native Californians, most of whom were of Ohlone descent, who are buried in the two mission cemeteries on the SCU campus. Taking inspiration in part from the work of Ohlone relatives at Mission San Francisco de Asís (Galvan and Medina, 2018), representatives from the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe and SCU personnel created a digital memorial that opened in SCU's de Saisset Museum in the autumn of 2023. The memorial includes the names of all 7,612 Native people listed in the mission's burial records, as well as a series of biographies of Native individuals that were written by SCU students in conversation with Muwekma Ohlone tribal youth ambassadors. Crucially, the exhibit seeks to make connections between the past and the present, and to that end, includes video segments featuring Muwekma Ohlone leaders and youth speaking about how the events of the mission period continue to reverberate for their community today (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Members of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe at the Native memorial at Santa Clara University's de Saisset Museum. Left to right: Gloria Gomez, Isabella Gomez, GiGi Gomez, Lucas Arellano, and Monica V. Arellano. Photo courtesy of Lauren Baines.

At SCU, the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe is also working to reinsert Indigenous heritage across the landscape. Given the inertia of the physical interpretive environment, detailed by the Ohlone History Working Group report (Baines et al., 2020), much of this work has thus far relied on digital platforms (Lueck and Panich, 2020). For example, in the summer of 2020, representatives from the Tribe worked with other Ohlone community members, as well as Panich and SCU personnel, to create a virtual walking tour to be used in remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hosted on Google Earth, the tour focuses primarily on Ohlone interpretation of archaeological deposits on and near the SCU campus, including a precontact village site and the vast Native neighborhood, or ranchería, associated with Mission Santa Clara (Panich et al., 2014; Peelo et al., 2018). Google Earth tours, however, are not well supported on most mobile phones. Accordingly, the project team, which has expanded to include other SCU faculty and students, is now in the process of developing an augmented reality (AR) tour that users can experience on their mobile devices (Jauregui et al., 2024). The capabilities of the AR tour also allow for different forms of content, such as 3D models, audio, and video. In keeping with the tribal interests, these possibilities have expanded the tour beyond archaeology to highlight Muwekma Ohlone heritage past, present, and future.

Taken together, these interrelated projects demonstrate how archaeologists and descendant communities can work together to reclaim colonial spaces. Crucially, at SCU the process has been one of co-creation, in which Muwekma Ohlone representatives have provided direction to interdisciplinary teams who have leveraged university resources for collaborative interventions in the local heritage landscape. Within this context, the inclusion of undergraduate students has been especially important, as SCU students have a demonstrated interest in local archaeology and Ohlone heritage but have been excluded from several recent large-scale CRM projects on their own campus (Kroot and Panich, 2020). By working with the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe on the heritage projects described above, students gain a firsthand appreciation for how archaeologists and other scholars can collaborate productively with Indigenous communities. Of course, this work is not always easy, and it is important for students and practitioners alike to reflect on the challenges of engaging with difficult histories across differences in individual and institutional positionalities (Lueck et al., 2021; Gomez and Lueck, 2023). But it is worth doing, since as Montgomery and Fryer (2023) remind us, “the future of archaeology is (still) community collaboration.”

5 Native resistance and the roots of dispossession

As disruptive as the mission system was to Native life in California, the lands surrounding each mission were—in a quasi-legal sense—still held in trust for the missions' Indigenous residents. When the missions began to close down in the 1830s, in a process called secularization, this understanding was undermined by colonial elites. Seeking to control the highly productive lands of California's coasts and inland valleys, colonists petitioned for grants of former mission lands leading to the rise of huge estates all across the region. Though the American annexation in the late 1840s led to an outright genocide in the attempt to seize Native land, the origins of dispossession that began in earnest in the 1830s are of particular relevance for understanding the colonial history of the San Francisco Bay region and the realities faced by the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe today.

Few archaeological datasets or published first-hand accounts offer a Native perspective on the process of mission secularization in Muwekma Ohlone homelands of the southern Bay Area, though it is worth pointing out that in the 1870s, an Ohlone man—Lorenzo Asisara—provided a testimonial about the inequities his communities experienced at Mission Santa Cruz, on the Pacific Coast, some four decades earlier (Castillo, 1989; and see Rizzo-Martinez, 2022). To address this gap in understanding, our team has been conducting research on primary archival documents that may offer different ways of viewing the written and archaeological records for Muwekma Ohlone homelands during the 1830s and 1840s (Panich et al., in press). Here, we focus on one specific document from the year 1842 that was identified and translated by coauthor Gustavo Flores (Anonymous, 1842). This primary document is an indictment against several Native men from Mission San José and other nearby missions who plotted a revolt in response to what they saw as the theft of their lands and property. It includes their direct testimony as recorded by a court scribe in the Pueblo of San José in June of 1842 (see Figure 1). In these pages, we learn about their complaints, and why they sought to capture a Californio colonist named José de Jesús Vallejo, who was an administrator at Mission San José and the elder brother of Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, a very important colonist in Alta California. This court hearing took place 4 years before the Americans would begin their own occupation of California. However even at this time, Californios were beginning to take possession of Native land, and many of the Native men who stood before the court objected to the fact that Vallejo was doing just that. The translation of this document provides several insights, two of which we will focus on here.

The first thing that we can decipher from the court document is the identities of the people involved. Contextualizing names, age, origin, and religion for each individual provides a more detailed perspective on the identities of these Native men. This information can then be cross-referenced, using mission sacramental records related to baptisms, marriages, and burials to identify specific individuals and trace their genealogy through time and their social relationships to their contemporaries in the mission system. One name that appears in the court transcript is Zenon, whose Native name was Patcha. Zenon Patcha can be linked to several current members of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, as he was the father of Angela Colos (Santa Clara baptism #7774; see Early California Population Project, 2022), an important Ohlone ancestor who participated in extensive interviews with early anthropologists, as described below. In the testimony, Zenon Patcha was identified as a ringleader who organized and carried out this plan to fight for Native people's land and property. Even though Zenon Patcha was baptized originally at Mission San Rafael, we know through marriage records that he found his way to the southern San Francisco Bay region by the 1830s (Santa Clara marriage #2711; see Early California Population Project, 2022).

Furthermore, translating this account brings to light the agency of Native people to organize and address the rapidly disappearing mission lands that elite Californios were converting into private ranchos. Instead of passively watching as the land that had been promised to them by the Church was being expropriated, these Native Californians were organizing a revolt to remove José de Jesús Vallejo from control of the mission and keep him from taking their land and other goods. Some of the Native men, or ringleaders as the document describes them, were caught as a result of this act of resistance, and placed in custody during an investigation into the revolt.

This primary document demonstrates the continuity of the struggles for land. The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe continues this legacy of activism as they work to organize to regain their status as a federally recognized tribe. One of their goals is to gain land back, as a space that can continue to exist for future generations. Exploring the rich archival record that includes not just this court case but many other documents related to Ohlone people in the 1830s and 1840s provides new information about how the ancestors of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe fought for land, similar to the struggles that they continue to fight today. These connections were revealed through collaboration, reviewing, translating, and cross referencing the primary sources, which can be a powerful tool for gaining a more nuanced view of the region's history, often through the voices of Native individuals themselves.

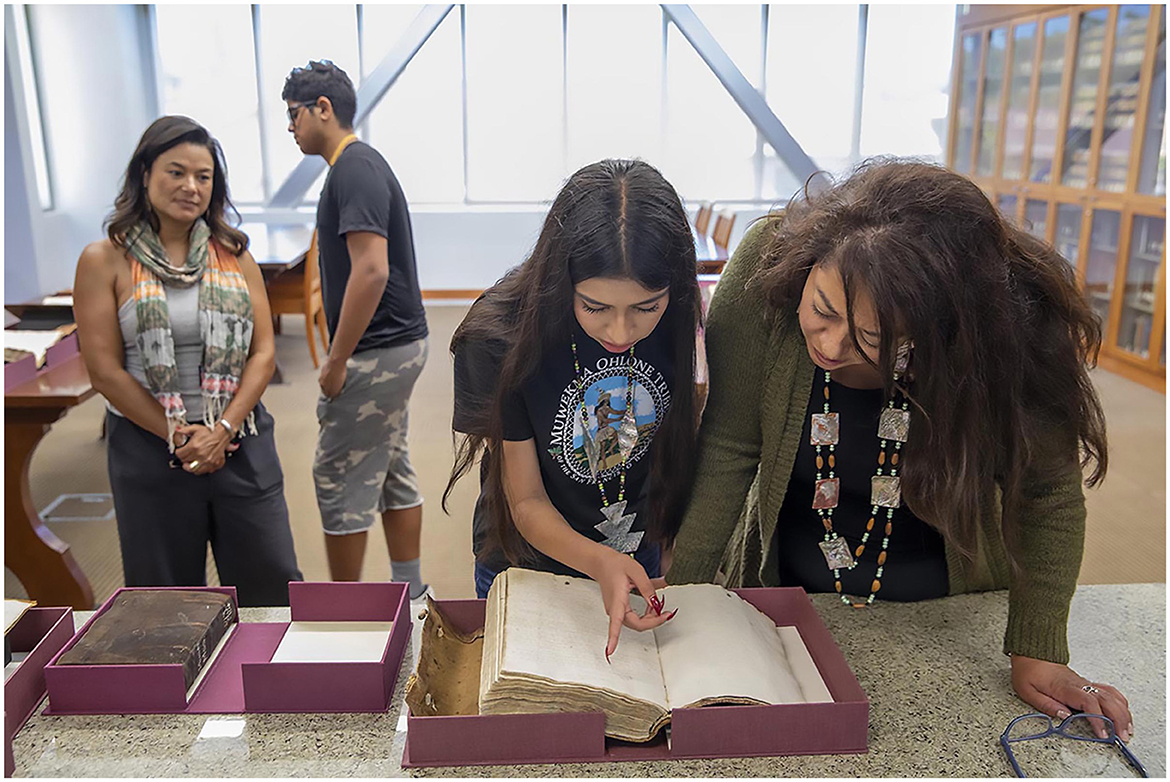

This research is part of a broader set of interrelated research projects that bring together colleagues from archaeology, adjacent disciplines, and the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe to consider a range of primary documents written when colonists from New Spain first occupied California. Overall, these documents, dating from 1769 to the late 1850s, chronicle the dramatic changes to the Tribe's ancestral homelands through source material ranging from letters, early baptismal records, ecclesiastical documents, and court records. No single repository exists for this material, making it challenging for descendant communities to access; documents can be found anywhere from university libraries, municipal archives, to small historical societies. Some of the collections that the project team have worked with are housed at History San José in the city of San Jose, the Bancroft Library at the University of California Berkeley, and the Early California Population Project database housed by the University of California Riverside and the Huntington Library. We have also been particularly grateful to the staff at the SCU Archives and Special Collections, who have opened their doors and manuscript collections to members of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe on several occasions (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Members of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe reviewing mission-period documents at the Santa Clara University Archives and Special Collections. Left to right, Chairwoman Charlene Nijmeh, Tristan Nijmeh, Isabella Gomez, Gloria Gomez. Photo courtesy of Kike Arnal.

Researching and translating colonial period documents provides a critical insight into the lives of Native people who experienced colonialism firsthand, and offers a glimpse into powerful events—such as the planned revolt against the administrators of Mission San José—that are largely invisible in the archaeological record. Translating is a valuable tool to deeply understand history, and to rectify outdated historical views of Native people in the San Francisco Bay Area. It allows us to ask the following questions: Can we see Native Californian struggles to hold onto their ancestral homelands? Can we connect identities in the documentary records to tribal lineages and specific members of descendant communities today? By addressing these critical questions, we can see better how ancestors of today's Muwekma Ohlone Tribe fought to hold onto their property and lands as the mission system collapsed around them, thus offering new insights into the Indigenous heritage of the San Francisco Bay Area.

6 Awakening traditional ecological knowledge

Given the colonial history of the San Francisco Bay Area, how might archaeologists support communities like the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe who are looking forward to a different type of future? Environmental justice research often focuses on how environmental and planning policies disproportionately impact on communities of color. Within this broader framing, tribal communities in the United States—like Indigenous peoples elsewhere—stand out due to the amplifying effects of colonialism. For example, settler colonial encroachment and theft of ancestral territories has resulted in limited access to specific homelands, the resources contained therein, and ultimately, traditional ecological and sacred knowledge (Harris and Harper, 2011; Whyte, 2016). Indeed, the expropriation of Native lands had profound effects for tribal communities across California. Rather than simply documenting such harms, however, archaeologists in the San Francisco Bay Area are contributing to collaborative, tribally-led efforts to repair historical injustices. Below, we discuss efforts to support tribal goals through the Muwekma Ohlone Preservation Foundation, which oversees projects related to cultural revitalization and land access, ownership, and stewardship.

A major initiative in this regard is to awaken traditional ecological knowledge that has gone dormant over the past 250 years of Spanish, Mexican, and American colonialism—including information on plants, animals, and gathering places—to contribute to the environmental health and sovereignty of the contemporary tribal community (Field et al., 2007). Even though settlers managed to gain control of most of the ancestral homelands of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, many ancestors found refuge in and around the Alisal rancheria where they kept critical information alive. Ohlone ancestors living in that area participated in an important cultural revival during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Accordingly, several well-known anthropologists visited the community, providing an opportunity for Ohlone elders to leave an invaluable record for future generations.

The most extensive conversations took place with linguist John Peabody Harrington of the Smithsonian Institution, who spoke with several prominent Ohlone elders, including Angela Colos, Jose Guzman, Susana Nichols, and Jose Binoco, among others (Harrington, 1984). Many of these individuals were born in the waning days of the mission period and were raised by parents, grandparents, and other relatives who taught them extensive knowledge of local landscapes and the plants and animals that sustained them. Accordingly, Harrington's copious field notes contain detailed accounts of ecological practices as well as names of plants and animals in the Chochenyo Ohlone language. This information offers solid evidence of how Ohlone people used local landscapes and particular species of plants and animals before and after the arrival of Euro-Americans to the San Francisco Bay area. Drawing inspiration from academic-tribal partnerships like those discussed elsewhere in this special issue, we are currently working with the Tribe to transcribe and annotate relevant information from Harrington's interviews with Muwekma Ohlone elders for the purposes of awakening the knowledge that they passed down (Lightfoot et al., 2021; and see Woodward and Macri, 2005).

Despite the historical challenges faced by their ancestors, the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe is today making strides toward reestablishing traditional stewardship practices across their ancestral homelands. At Stanford University, for example, coauthor Michael Wilcox has established a native plant garden that serves both as a community engaged learning space for Stanford students and as a test plot for the Tribe's revival of broader landscape stewardship practices (Figure 6). In classes taught through the Center for the Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity, Wilcox brings students out of the classroom to a corner of the Stanford campus where hawks circle above and students can imagine a Bay Area landscape managed by tribal communities. There, students can also directly confront the cumulative colonial impacts, such as widescale dispossession, that are facing the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe while simultaneously helping to redress critical issues like food justice and tribal sovereignty through their labor and class projects aimed at advancing the garden.

Figure 6. Seedling prior to planting on a collaborative work day at the Stanford native plant garden. Photo by Lee Panich.

Over the course of several years, for example, Stanford students and tribal partners have removed thistle (Cirsium vulgare) and other invasive species that have direct connections to the colonial history of the region (Allen, 2010; Fischer, 2015). Students then work to replace these invasive species with grasses, flowers, and herbs that have cultural relevance for the tribal community, as informed by archaeological research and the reclamation of ancestral knowledge from anthropological archives, such as Harrington's field notes. A current project is restoring understory vegetation in a heavily impacted portion of the Stanford native plant garden that was historically used as a staging area for a gravel pit. Students and tribal members have planted species including sages (Salvia spp.), manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.) wild rose (Rosa californica), and thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus)—all of which are well documented in the archaeological and ethnographic literature for the region (e.g., Lightfoot and Parrish, 2009). Importantly, the Stanford native plant garden is also a small corner of their homeland in the urbanized San Francisco Bay Area that tribal members can use to awaken traditional practices.

The collaborative work at Stanford is one part of a growing effort by the Tribe, under the auspices of the Muwekma Ohlone Preservation Foundation, to strengthen connections to its ancestral territory. The Preservation Foundation has several key goals, including the establishment of a physical community—a new tribal village—that would provide opportunities for community and family wellbeing while offering a permanent land base in this rapidly gentrifying region. Indeed, land access is another key goal, underscoring the need for physical spaces to host gatherings and to implement newly awakened stewardship practices. As exemplified by the renaming of ancestral sites in the Chochenyo Ohlone language, described above, the Tribe has made great strides in the area of language revitalization, and the time is ripe for parallel strides in landscape stewardship. Through existing partnerships with local institutions—universities like Stanford as well as a host of conservation organizations—and based on the model of collaborative eco-archaeological studies in service of tribal sovereignty established by the neighboring Amah Mutsun Tribal Band (Lopez, 2013; Lightfoot et al., 2021; Apodaca et al., in press), the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe is well positioned to use historical and archaeological research to create a better future for its members.

7 Teaching the next generation

As archaeology continues to move toward a greater emphasis on community engagement, exemplified by the collaborative projects with the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe described above, the nature of field schools is evolving to meet the realities of a changing discipline. It is no secret that archaeological field schools have traditionally emphasized the training of students in exotic locations, though this mindset has shifted over the course of our own careers. For example, in the mid-1990s into the 2010s field schools began to emphasize community-based interactions, with students expressly asked to interact and hopefully integrate with communities. Recent approaches to field schools incorporate deeper connections to Indigenous rights, using the community based participatory research (CBPR) framework and specifically models drawn from Indigenous archaeologies (Silliman, 2008; Cipolla and Quinn, 2016; Cowie et al., 2019; Gonzalez and Edwards, 2020).

In California, field schools have started integrating Native Californian communities into programs that emphasize training in ethical fieldwork practices, low-impact field methods, and the co-creation of knowledge about the past. For example, a University of California Berkeley field school at the Russian Colony of Ross partnered with members of the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians to implement a non-invasive “catch and release” survey methodology in which ancestral sites were characterized by the analysis of surface artifacts that were returned at the completion of the project (Gonzalez et al., 2006). This collaborative approach also exists on Santa Catalina Island, where Desireé Martinez and Wendy Teeter have built an exemplary model of this practice. The Pimu Catalina Island Archaeology Project braids Indigenous and western knowledge and practices. Tongva tribal members are part of the planning and teaching of the field programs (Martinez, 2012). More recently, Berkeley archaeologists have been working with the United Auburn Indian Community on prescribed fire burns and forestry management projects with students making direct contributions to tribal projects (Sunseri et al., in press). These programs, and others like them, can benefit tribes both by producing knowledge of the past in a sensitive way and by establishing new professional norms regarding respectful collaboration that are becoming a standard part of archaeological practice in California and elsewhere.

In the southern San Francisco Bay area, each of the coauthors of this article have endeavored to provide students with classroom materials and hands-on experiences that align with the wishes of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe and the other Indigenous communities with which we work. For example, coauthor Sam Connell regularly runs field schools through Foothill College that are, in part, designed to be service projects (Figure 7). Here, the educational lessons are of course to be “of service” but also to consider the nature of stakeholder intentions and wishes. In such cases, the outcomes of collaboration can include both practical products, such as site testing or cultural resource inventories of particular parcels of interest to descendant communities, or more abstract benefits, such as instilling students with a regard for tribal sovereignty at the very outset of their young careers in archaeology. Ultimately, these are important conversations to have with students on archaeological projects who are interested in getting it right. Students, in other words, are interested in making an impact and they want to address the colonial narratives of archaeology head on (Connell, 2012).

There is no doubt that the future of archaeological field schools—like archaeology more generally—is more community collaboration, particularly under the auspices of tribal communities. At Foothill College, field schools that are offered in California are constructed to maximize connection to tribes while simultaneously being cognizant on the potential burden that archaeology (especially field schools) can put on tribal members and administrators. Still, exit interviews with students consistently highlight the moments where scientific methods were woven with traditional ecological knowledges. Students have a strong desire to help in whatever capacity possible, and service learning projects or days spent directly contributing to Native-led projects are important experiences that no classroom lecture can offer. The current generation of students has recognized, at times before their faculty mentors, the essential importance of collaborative research. As discussed above, many CRM firms are already on board and have created strong collaborative relationships with the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe and other Native Californian communities. It is time for archaeological training to meet this demand.

8 Discussion and conclusion

We are writing this essay in the midst of fundamental shifts in the field of archaeology, and in California archaeology in particular. After decades of rampant destruction and desecration of ancestral sites—particularly during the massive expansion of California's population centers since the mid-20th century—tribal communities across the region have found themselves at the nexus of competing interests involving construction, archaeological research, and Indigenous stewardship of cultural heritage. The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe is no exception, and tribal members have for decades stood up to archaeologists in both academia and CRM who disregarded community concerns about the treatment of ancestors and the continuing importance of sacred places across the landscape. Yet, the papers in this special issue—combined with myriad others in the broader literature—give us hope for the future of archaeology conducted with, for, and by Indigenous communities (Nelson, 2021), particularly in the critical realm of sustainable stewardship of both cultural landscapes and heritage places.

As educators, we recognize our particular obligation to provide students and the next generation of archaeologists with a different, less extractive model of what archaeology can be. Of course, training in field methods remains an important cornerstone of undergraduate education, but the overarching ethos needs to be one in which impacts to ancestral sites are minimized and the interests of descendant communities are prioritized. This is not necessarily new—Mack and Blakey (2004) argued for viewing descendant communities as an “ethical client” some two decades ago—but now more than ever this posture requires a reappraisal of what it means to do archaeology (Schneider and Hayes, 2020). As summarized above, many of our colleagues in CRM archaeology have also built productive collaborative relationships with the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe and other Native Californian communities, often through large-scale data recovery projects in which they have worked side by side with tribal members to produce meaningful results (Monroe et al., 2022). We see this work as proof that training in community based collaborative archaeology is a critical element of career development for a 21st century archaeology.

So, returning to the title of our paper, what does it mean to put archaeology to work for the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe? Building on the long history of the Tribe's involvement with archaeology, each of us might answer slightly differently, but all of us look to our Muwekma Ohlone partners for guidance on how best to center the interests of the Tribe in our collaborative work. This could include representing tribal interests in meetings with developers and CRM archaeologists or renaming ancestral sites in the Chochenyo Ohlone language; working with students and tribal members to leverage the material record to commemorate those impacted by colonial missions; finding new archival evidence of how tribal ancestors fought against early land grabs; digging holes not for the recovery of artifacts but to plant seedlings that will help awaken traditional knowledge and related practices; or training the next generation to put the needs of descendant communities first. In their own way, each of these projects—and numerous others involving our colleagues at other institutions—are designed to support the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe's stewardship of their own heritage and cultural landscapes.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

LP: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MA: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing. MW: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing. GF: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SC: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The Mission Santa Clara cemetery memorial was funded by the American Council of Learned Societies through a Sustaining Public Engagement Grant as part of the National Endowment for the Humanities' Sustaining the Humanities through the American Rescue Plan (SHARP) initiative. Foothill College field schools have been funded by the Associated Students of Foothill College. Aspects of other projects described in this article were supported by the Far Western Foundation, the Santa Clara University Center for the Arts and Humanities, and the Environmental Justice and the Common Good Initiative at Santa Clara University.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe for inviting us into this important work. Alan Leventhal has supported the Tribe's efforts in these realms for many years. We also appreciate the insights of Mark Hylkema, who has encouraged several of the ideas presented here. The transcription of Harrington's field notes has benefited from the dedication of Anita Song. Lauren Baines, Isabella Gomez, Amy Lueck, and Tristan Nijmeh have all contributed substantially to the work at Santa Clara University. Lastly, we appreciate the invitation from Gabe Sanchez, Mike Grone, and the other editors of this special issue for the opportunity to share our ongoing projects.

Conflict of interest

MA was employed by Muwekma Ohlone Tribe.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allen, R. (2010). Alta California missions and the pre−1849 transformation of coastal lands. Histor. Archaeol. 44, 69–80. doi: 10.1007/BF03376804

Anonymous (1842). Interrogations of Native men related to a planned uprising at Mission San José, 17 June 1842, Document ID 1979-861-1974. Pueblo Papers Collection, History San José, San Jose, California.

Apodaca A. Sigona A. Grone M. Sanchez G. Lopez V. Lightfoot K. G. (in press). Indigenous eco-archaeology: past present, future of environmental stewardship in Central Coastal California. Front. Environ. Archaeol.

Baines, L., Galvan, A., Leventhal, A., Moore, C., Nijmeh, C., Panich, L., et al. (2020). Ohlone History Working Group report. Santa Clara University. Available online at: https://www.scu.edu/media/offices/diversity/pdfs/V10.2_OHWG_CombinedReportFINAL.pdf (accessed February 5, 2024).

Barron, N. (2022). “Alfred Kroeber's Handbook and land claims: anthros, agents, and federal (un)acknowledgment in Native California,” in BEROSE International Encyclopedia of the Histories of Anthropology (Paris: BEROSE).

Becks, F. (2015). Tribal archaeology as ownership of the ancestral past. Available online at: https://www.sfu.ca/ipinch/outputs/blog/ (accessed February 5, 2024).

Becks, F. (2018). Articulations of the ineffable: narratives, engagement, and historical anthropology with the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay area. [dissertation]. Sanford, CA: Stanford University.

Byrd, B. F., Arellano, M. V., Engbring, L., Leventhal, A., and Darcangelo, M. (2022). Community-based archaeology at Síi Túupentak in the San Francisco Bay area: integrated perspectives on collaborative research at a major protohistoric Native American settlement. J. Calif. Great Basin Anthropol. 42, 135–158.

Cambra, R., Leventhal, A., Jones, L., Hammett, J., Field, L., and Sanchez, N. (1996). Archaeological investigations at Kaphan Umux (Three Wolves) site, CA-SCL-732: a middle period cemetery on Coyote Creek in Southern San Jose, Santa Clara County, California. Report to Santa Clara County Traffic Authority and California Department of Transportation, District 4.

Castillo, E. D. (1989). An Indian account of the decline and collapse of Mexico's hegemony over the missionized Indians of California. Am. Indian Quart. 13, 391–408. doi: 10.2307/1184523

Cipolla, C. N., and Quinn, J. (2016). Field school archaeology the Mohegan way: reflections on twenty years of community-based research and teaching. J. Commun. Archaeol. Herit. 3, 118–134. doi: 10.1080/20518196.2016.1154734

Connell, S. V. (2012). Broadening the scope of archaeological field schools. SAA Archaeol. Rec. 12, 25–28.

Cowie, S. E., Teeman, D. L., and LeBlanc, C. C. (2019). Collaborative Archaeology at Stewart Indian School. Reno: University of Nevada Press.

Dartt-Newton, D. (2011). California's sites of conscience: an analysis of the state's historic mission museums. Museum Anthropol. 34, 97–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1379.2011.01111.x

Early California Population Project (2022). Edition 1.1. General Editor, S.W. Hackel. University of California, Riverside and The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Field, L. W. (1999). Complicities and collaborations: anthropologists and the ‘unacknowledged tribes' of California. Curr. Anthropol. 40, 193–209. doi: 10.1086/200004

Field, L. W., Leventhal, A., and Cambra, R. (2013). “Mapping erasure: the power of nominative cartography in the past and present of the Muwekma Ohlones of the San Francisco Bay area,” in Recognition, Sovereignty Struggles, and Indigenous Rights in the United States: A Sourcebook, eds. A.E. Den Ouden and J.M. O'Brien (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), 287–309.

Field, L. W., Leventhal, A., Sanchez, D., and Cambra, R. (2007). “Part 2: a contemporary Ohlone tribal revitalization movement: a perspective from the Muwekma Costanoan/Ohlone Indians of the San Francisco Bay,” in Santa Clara Valley Prehistory: Archaeological Investigations at CA-SCL-690 the Tamien Station Site, San Jose, California, ed. M. Hylkema (Davis, CA: Center for Archaeological Research at Davis), 61–82.

Fischer, J. R. (2015). Cattle Colonialism: An Environmental History of the Conquest of California and Hawai'i. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. doi: 10.5149/northcarolina/9781469625126.001.0001

Fryer, T. C., and Dedrick, M. (2023). Introduction: let's reckon, then. Am. Anthropol. 125, 334–345. doi: 10.1111/aman.13840

Galvan, A., and Medina, V. (2018). “Indian memorials at california missions,” in Franciscans and American Indians in Pan-Borderlands Perspective: Adaptation, Negotiation, and Resistance, eds. J. M. Burns and T. J. Johnson (Oceanside, CA: American Academy of Franciscan History), 323–331.

Gomez, I. A., and Lueck, A. J. (2023). To embrace tension or recoil away from it: navigating complex collaborations in cultural rhetorics work. Coll. Composit. Commun. 75, 75–96. doi: 10.58680/ccc202332668

Gonzalez, S. L., and Edwards, B. (2020). The intersection of Indigenous thought and archaeological practice: the field methods in indigenous archaeology field school. J. Commun. Archaeol. Herit. 7, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/20518196.2020.1724631

Gonzalez, S. L., Modzelewski, D., Panich, L. M., and Schneider, T. D. (2006). Archaeology for the seventh generation. Am. Indian Quart. 30, 388–415. doi: 10.1353/aiq.2006.0023

Harrington, J. P. (1984). Costanoan Field Notes. John P. Harrington Papers, Vol. 2: Northern and Central California. Microfilm edition. Washington, DC: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Harris, S., and Harper, B. (2011). A method for tribal environmental justice analysis. Environ. Just. 4, 231–237. doi: 10.1089/env.2010.0038

Hull, K. L., and Douglass, J. G. (2018). Forging Communities in Colonial Alta California. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv47wfrg

Hylkema, M. G. (1995). Archaeological Investigations at the Third Location of Mission Santa Clara de Asís: The Murguía Mission, 1781-1818 (CA-SCL-30/H). Report to the California Department of Transportation, District 4.

Jauregui, C., Nguyen, T. T., Sallee, S. H., Chandrasekar, M. R., A'Hearn, L., Woetzel, D. J., et al. (2024). “We are still here: the Thámien Ohlone augmented reality tour,” in CHI EA ‘24: Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 647, 1–3. doi: 10.1145/3613905.3649127

Kakaliouras, A. M. (2012). An anthropology of repatriation: contemporary physical anthropological and Native American ontologies of practice. Curr. Anthropol. 53, S210–221. doi: 10.1086/662331

Kroeber, A. L. (1925). Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, No. 78. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Kroot, M. V., and Panich, L. M. (2020). Students are stakeholders in on-campus archaeology. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 8, 134–150. doi: 10.1017/aap.2020.12

Kryder-Reid, E. (2016). California Mission Landscapes: Race, Memory, and the Politics of Heritage. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Laluk, N. C., Montgomery, L. M., Tsosie, R., McCleave, C., Miron, R., Carroll, S. R., et al. (2022). Archaeology and social justice in Native America. Am. Antiq. 87, 659–682. doi: 10.1017/aaq.2022.59

Leventhal, A., DiGiuseppe, D., Atwood, M., Grant, D., Cambra, R., Nijmeh, C., et al. (2011). Final Report on the Burial and Archaeological Data Recovery Program Conducted on a Portion of the Mission Santa Clara Indian Neophyte Cemetery (1781-1818): Clareño Muwékma Ya Túnnešte Nómmo [Where the Clareño Indians Are Buried] Site (CA-SCL-30/H), Located in the City of Santa Clara, Santa Clara County, California. Report to Pacific Gas and Electric Company.

Leventhal, A., DiGiuseppe, D., Grant, D., Arellano, M. V., Guzman-Schmidt, S., Gomez, G. E., et al. (2023). Report on the Burial Recovery Program, Stable Isotope Analysis and AMS Dating of Two Muwekma Ohlone Ancestral Remains Conducted on a Portion of Širkeewis Ríipin Tiprectak (Place of the Black Willow Marsh Site, CA-SCL-755) for the Admissions and Enrollment Services Building, Santa Clara University Campus, Santa Clara, Santa Clara County, California. Report to Santa Clara University.

Leventhal, A., Field, L., Alvarez, H., and Cambra, R. (1994). “The Ohlone: back from extinction,” in The Ohlone Past and Present: Native Americans of the San Francisco Bay Region, ed. L.J. Bean (Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press), 297–336.

Lightfoot, K. G., Cuthrell, R. Q., Hylkema, M. G., Lopez, V., Gifford-Gonzalez, D., Jewett, R. A., et al. (2021). The eco-archaeological investigation of Indigenous stewardship practices on the Santa Cruz coast. J. Califor. Great Basin Anthropol. 41, 187–205.

Lightfoot, K. G., Cuthrell, R. Q., Striplen, C. J., and Hylkema, M. G. (2013). Rethinking the study of landscape management practices among hunter-gatherers in North America. Am. Antiq. 78, 285–301. doi: 10.7183/0002-7316.78.2.285

Lightfoot, K. G., Luby, E. M., and Sanchez, G. M. (2017). Monumentality in the hunter-gatherer-fisher landscapes of the greater San Francisco Bay, California. Hunt. Gath. Res. 3, 65–85. doi: 10.3828/hgr.2017.5

Lightfoot, K. G., and Parrish, O. (2009). California Indians and Their Environment: An Introduction. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lindsay, B. C. (2012). Murder State: California's Native American Genocide, 1846-1873. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt1d9nqs3

Little, B. J. (2023). Bending Archaeology Toward Social Justice: Transformational Action for Positive Peace. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Lopez, V. (2013). The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band: reflections on collaborative archaeology. Califor. Archaeol. 5, 221–223. doi: 10.1179/1947461X13Z.00000000012

Lueck, A. J., Kroot, M. V., and Panich, L. M. (2021). Public memory as community-engaged writing: composing difficult histories on campus. Commun. Liter. J. 15, 9–30. doi: 10.25148/CLJ.15.2.009618

Lueck, A. J., and Panich, L. M. (2020). “Representing Indigenous histories using XR technologies in the classroom,” in Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, 17.

Mack, M. E., and Blakey, M. (2004). The New York African Burial Ground project: past biases, current dilemmas, and future research opportunities. Histor. Archaeol. 38, 10–17. doi: 10.1007/BF03376629

Madley, B. (2016). An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Martinez D. R. (2012) “A land of many archaeologists: archaeology with Native Californians,” in Contemporary Issues in California Archaeology, eds. T.L Jones and J.E. Perry (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press), 355–367. 10.4324/9781315431659-20.

Medina, V. (2015). Our cemetery, our elder: hope and continuity at the Ohlone Cemetery. News Nat. Califor. 29, 16–19.

Milliken, R. (1995). A Time of Little Choice: The Disintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1769–1810. Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press.

Milliken, R., Shoup, L. H., and Ortiz, B. R. (2009). Ohlone/Costanoan Indians of the San Francisco Peninsula and their Neighbors, Yesterday and Today. Report to the National Park Service, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, San Francisco.

Monroe, C., Arellano, M. V., and Leventhal, A. (2022). New perspectives and collaborations on the ancestral biology of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe. Hum. Biol. 94, 5–8. doi: 10.1353/hub.2022.a919548

Montgomery, L. M., and Fryer, T. C. (2023). The future of archaeology is (still) community collaboration. Antiquity 394, 795–809. doi: 10.15184/aqy.2023.98

Nelson, P. A. (2021). Where have all the anthros gone? The shift in California Indian studies from research “on” to research “with, for, and by” Indigenous peoples. Am. Anthropol. 123, 469–473. doi: 10.1111/aman.13633

Panich L.M. Flores G. Wilcox M. Arellano M. (in press). Reading colonial transitions: archival evidence the archaeology of Indigenous action in nineteenth-century California. American Antiquity.

Panich, L. M. (2016). After Saint Serra: unearthing Indigenous histories at the California missions. J. Soc. Archaeol. 16, 238–258. doi: 10.1177/1469605316639799

Panich, L. M. (2019). “‘Mission Indians' and Settler Colonialism: Rethinking Indigenous Persistence in Nineteenth-Century Central California,” in Indigenous Persistence in the Colonized Americas, eds. H. Law Pezzarossi and R.N. Sheptak (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press), 121–144.

Panich, L. M. (2020). Narratives of Persistence: Indigenous Negotiations of Colonialism in Alta and Baja California. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv105bb3h

Panich, L. M. (2022). Archaeology, Indigenous erasure, and the creation of white public space at the California missions. J. Soc. Archaeol. 22, 149–171. doi: 10.1177/14696053211061675

Panich, L. M., Afaghani, H., and Mathwich, N. (2014). Assessing the diversity of mission populations through the comparison of Native American residences at Mission Santa Clara de Asís. Int. J. Histor. Archaeol. 18, 467–488. doi: 10.1007/s10761-014-0266-1

Panich, L. M., and Schneider, T. D. (2014). Indigenous Landscapes and Spanish Missions: New Perspectives from Archaeology and Ethnohistory. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Peelo, S., Hylkema, L., Ellison, J., Blount, C., Hylkema, M., Maher, M., et al. (2018). Persistence in the Indian ranchería at Mission Santa Clara de Asís. J. Califor. Great Basin Anthropol. 38, 207–234.

Ragland, A. M. (2018). Resisting Erasure: The History, Heritage, and Legacy of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area. [master's thesis]. San Jose, CA: San Jose State University.

Rizzo-Martinez, M. (2022). We Are Not Animals: Indigenous Politics of Survival, Rebellion, and Reconstitution in Nineteenth-Century California. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv270kv7w

Schneider, T. D., and Hayes, K. (2020). Epistemic colonialism: is it possible to decolonize archaeology? Am. Indian Quart. 44, 127–148. doi: 10.1353/aiq.2020.a756930

Severson, A. L., Byrd, B. F., Mallott, E. K., Owings, A. C., DeGiorgio, M., de Flamingh, A., et al. (2022). Ancient and modern genomics of the Ohlone Indigenous population of California. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119:e2111533119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2111533119

Shoup, L. H., and Milliken, R. T. (1999). Inigo of Rancho Posolmi: The Life and Times of a Mission Indian. Novato, CA: Ballena Press.

Silliman, S. W. (2008). Collaborating at the Trowel's Edge: Teaching and Learning in Indigenous Archaeology. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Sunseri J. Moore M. Allen R. (in press). Seeing ‘Esak ‘Tima (Places to learn): cultural fire archaeology non-invasive geophysics as guardianship of ancestral places. Front. Environ. Archaeol.

Whyte, K. P. (2016). “Indigenous experience, environmental justice and settler colonialism,” in Nature and Experience: Phenomenology and the Environment, ed. B.E. Bannon (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield), 157–174. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2770058

Keywords: Indigenous archaeology, colonialism, traditional ecological knowledge, Ohlone, California

Citation: Panich LM, Arellano MV, Wilcox M, Flores G and Connell S (2024) Fighting erasure and dispossession in the San Francisco Bay Area: putting archaeology to work for the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe. Front. Environ. Archaeol. 3:1394106. doi: 10.3389/fearc.2024.1394106

Received: 01 March 2024; Accepted: 22 May 2024;

Published: 05 June 2024.

Edited by:

Michael Grone, California Department of Parks and Recreation, United StatesReviewed by:

Mark Hylkema, Center for American Archaeology, United StatesMarshall Weisler, The University of Queensland, Australia

Mneesha Gellman, Emerson College, United States

Copyright © 2024 Panich, Arellano, Wilcox, Flores and Connell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lee M. Panich, bHBhbmljaEBzY3UuZWR1

Lee M. Panich

Lee M. Panich Monica V. Arellano2

Monica V. Arellano2 Gustavo Flores

Gustavo Flores