- Department of Psychology, Centre for Cognitive Neuroscience, Paris-Lodron-University of Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria

Sexual prejudice negatively impacts our society and commonly manifests itself in hostile attitudes and aggressive behavior toward people who identify with the LGBTQIA+ community. Adolescents in particular are vulnerable to such negative world views. The present study investigated the impact of the parent-adolescent relationship quality, the potentially associated manifestation of psychopathic personality traits—so-called callous-unemotional (CU) traits—and their relation to sexual prejudice in adolescence. We observed that poor maternal relationship quality in terms of poor communication, lack of trust, and alienation is associated with selfish, cold-hearted personality traits. Moreover, we observed an indirect effect of CU-traits mediating the link between maternal relationship quality and antigay hostile attitudes and behavior. Our findings emphasize the crucial role of attachment in the development of a child's affective personality.

1 Introduction

Sexual prejudice describes negative attitudes toward people based on their sexual orientation (Herek, 2004). It is not only expressed by negative attitudes (Orue and Calvete, 2018), but also directly in behavior such as antigay bullying (D'Urso et al., 2018, 2020) and aggressive behavior (verbal or physical) against people of different sexual orientation (Rivers, 2011). The most common form is verbal abuse (Swearer et al., 2010) which is widely found among adolescents (Klocke, 2012).

Sexual prejudice has a serious impact on our society and particularly on adolescents, for whom even physical attacks such as punching, or kicking are reported in schools (Rivers and Cowie, 2006). Victims of this form of violence suffer from increased anxiety levels, and higher probabilities for depressive states, substance abuse and even suicidal behavior (Espelage et al., 2008). The present study investigated potential mechanisms underlying the development of such hostile attitudes and behavior. We hypothesized that parental relationship quality and, as a probable consequence, lack of empathy and disregard for others—as assessed by the so-called callous-unemotional (CU) traits—contribute to this phenomenon.

Bowlby's attachment theory (Bowlby, 1982) revolutionized many explanations of human behavior by showing that there is an invisible bond between primary caregivers and the infant that is critical for the later psychological development of the child (for a review see Schore, 2001). For example, secure attachment is associated with higher self-esteem, higher life satisfaction, a healthier lifestyle, and more stable friendships as well as romantic relationships (Bowlby, 1982; Simpson, 1990; Ciocca et al., 2015). In contrast, insecurely attached individuals more often perceive their environment as hostile and have more difficulties in forming positive social relationships with others. As a result, insecure attachment has often been associated with externalizing behaviors, substance abuse disorders, delinquency, and antisocial personality traits (Bowlby, 1944; Fagot and Kavanagh, 1990; Fearon et al., 2010; Schindler and Bröning, 2015).

Research on attachment is dominated by the focus on the mother–child relationship. However, for many years now there is also a growing interest in how the father–child relationship may differ or resemble from this bond (for a meta-analysis see Pinquart, 2022). Since the role of fathers has changed in recent cohorts (Bretherton, 2010; Lamb, 2013; Dagan and Sagi-Schwartz, 2018), it is reasonable to assume that maternal and paternal relationship quality is substantially associated. To illustrate, there is evidence for a transmission of security from parents to their children (Verhage et al., 2016) and security of both parents tends to be positively correlated (Van IJzendoorn et al., 1992). Furthermore, the child's temperament may yield similarities in attachment to different caregivers (see Pinquart, 2022).

Despite ample evidence indicating a decisive role of attachment on later (anti-)social behavior, comparatively little research has been conducted to explore potential links between parent-adolescent relationship quality and sexual prejudice. Moreover, the limited evidence on this subject proved to be inconclusive. One of the first studies to examine the relationship of attachment and sexual prejudice showed that attachment style had no impact on sexual prejudice after controlling for the effects of gender and religious fundamentalism (Schwartz and Lindley, 2005; see also Metin-Orta and Metin-Camgöz, 2020). In contrast, Maftei and Holman (2021) demonstrated that attachment anxiety is directly related to sexual prejudice (see also Ciocca et al., 2015). The mixed evidence regarding the effect of attachment on sexual prejudice could be explained by the fact that parents' relationship to their children does not have a direct effect, but rather can be explained indirectly by the influence of a third variable.

Such a possible indirect relationship was investigated by D'Urso et al. (2020) in a sample of Italian adolescents. The authors argued that negative relationship experiences “[...] can lead to the psychotic structuring of personality” (p. e104). The resulting higher scores in psychoticism should in turn be related to increased antigay bullying. Indeed, D'Urso et al. were able to show that psychoticism mediated the relationship of parental attachment and antigay bullying. This result was particularly surprising given that adolescents generally scored very low on the psychoticism scale. This floor effect seems plausible when one considers that this construct also includes delusional symptoms (such as hallucinations and ideation) that may have been too pathological for a healthy sample. Moreover, one could argue that psychoticism, apart from a sense of alienation from one's social context, cannot fully explain the specific hostility toward people with a different sexual orientation. The present study therefore aimed to investigate whether the association between parent-adolescent relationship and antigay bullying is mediated by another construct, namely by the so-called CU-traits which represent some commonly observed personality traits in psychopaths. Critically, CU-traits show more variation in healthy individuals, and are often associated with affective deficits and a lack of guilt and empathy, and ultimately with antisocial behavior like humiliating or bullying others.

The construct of psychopathy can be traced back to the Canadian psychologist Robert Hare who identified some common personality traits among prisoners. He described psychopaths as selfish, cold-hearted, ruthless individuals with no empathy and an inability to form warm-hearted relationships with others (Hare, 2003, 2012). However, only individuals who show these psychopathic traits and additionally exhibit antisocial behavior are considered to suffer from psychopathy (Blair, 2001; Farrington, 2005). The prevalence of showing at least one psychopathic trait is 29.2% in the general population, whereas only 0.2% can be considered as being affected by psychopathy (Coid et al., 2009). CU-traits are considered to be precursors of psychopathy (Frick, 2004). The risks of developing such traits are manifold. Besides genetic predispositions (Tuvblad et al., 2014; Mann et al., 2015) and neurological alterations (Craig et al., 2009; Boccardi et al., 2011; Beaver et al., 2012; for a review see Herpers et al., 2014), environmental factors such as poor parental relationship quality are associated with their manifestation (for an overview see van der Zouwen et al., 2018).

CU-traits develop early in childhood with a peak between ages of 15 and 16, remain relatively stable into adulthood (Frick and White, 2008), and have a higher prevalence for males than females (Essau et al., 2006). Although CU-traits have been associated with many externalizing and delinquent behaviors such as bullying (Frick et al., 2005; Hawes and Dadds, 2005; Viding et al., 2009; Hawes et al., 2014; Ansel et al., 2015), the relationship with sexual prejudice has been largely neglected. To our knowledge, the relationship between psychopathy, bullying, sexual prejudice (in the form of name-calling) and sexual harassment has been examined only in a single master's thesis by Free (2017) who could demonstrate that psychopathy has a crucial influence on all of the aforementioned variables.

The present work was motivated by the promising findings from D'Urso et al. (2020) and Free (2017) demonstrating that poor attachment is associated with adverse personality traits and, consequently, with antigay bullying. In contrast to D'Urso et al. (2020), however, we operationalized these adverse personality traits by means of CU-traits. CU-traits show more variation in a non-pathological sample of adolescents as compared to psychoticism which revealed substantial floor effects in previous studies (Ciocca et al., 2015; D'Urso et al., 2020). We hypothesized that poor parent-adolescent relationship quality, manifested by poor communication, a lack of trust and a sense of alienation is associated with higher levels of CU-traits and, as a consequence, will lead to more antigay attitudes and bullying toward gay men and lesbian women.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and procedure

Six hundred twenty-five students aged between 15 and 21 years from secondary schools in the city of Salzburg participated in the present cross-sectional study. The survey was conducted online via LimeSurvey (Version 3.26.1). Three hundred thirty-one participants had to be excluded because they did not complete the online survey. Further 91 participants were excluded because they identified themselves as part of the LGBTQIA+ community, another 5 participants were excluded because they did not fall within the age range of 15 to 21 years. The remaining sample consisted of 197 students (144 female −57.9%) with a mean age of M = 17;3 (years; months), SD = 1;3. As the survey was conducted in schools, the Salzburg Education Directorate was the responsible Institutional Review Board (IRB) to protect the rights of the participating students. This IRB reviewed the research methods used and compliance with data protection regulations (IRB approval number 510003/0029-PA-ZV-IKT/2021). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation students provided written informed consent. All adolescents were at least 15 years of age and according to Austrian Law legally competent to give informed consent to participate in the study. The study was conducted over two survey periods in June 2020 and May 2022.

2.2 Materials

2.2.1 Parent-adolescent relationship

Parent-adolescent relationship was measured using the revised version of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA) (Armsden and Greenberg, 1987). This questionnaire was translated and back-translated by two independent translators. The back-translation was then compared with the original version and any inconsistencies were discussed and resolved by both translators. The IPPA assesses the relationship to the mother, father and peers on three subscales trust (e.g., “My mother/father respects my feelings”), communication (e.g., “I like to know my father's/mother's point of view about things that concern me”) and alienation (e.g., “I get angry much more often than my father/mother knows”). Each attachment scale (i.e., mother and father) consists of 25 items that are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from “never or almost never true” to “always or almost always true.” In the present study, total attachment scores for the mother and the father were calculated by combining the subscales trust, communication and alienation (Armsden and Greenberg, 1987). The IPPA was originally designed as a measure of attachment (as its name suggests) but is now more commonly used and interpreted as a measure of parent-child or parent-adolescent relationships. Both total scales had excellent internal consistencies, α = 0.95 for the father and α = 0.96 for the mother.

2.2.2 Callous-unemotional traits

Callous-unemotional traits (CU-traits) were measured using the German Version (Essau et al., 2006) of the Inventory of callous-unemotional traits (Frick, 2004), a commonly used instrument to assess psychopathic personality traits. This self-report questionnaire consists of 24 items answered on a 4-point Likert scale from “not at all true” to “definitely true.” The questionnaire assessed individuals variations in three factors, i.e., callousness (i.e., lack of empathy, guilt, and remorse of misdeeds: “I don't care who I hurt to get what I want”), uncaring (i.e., lack of caring about one's performance in tasks and for the feelings of other people: “I don't care if I'm on time”) and unemotional (absence of emotional expression: “I don't show my feelings to others”). As recommended by the authors, a total score was calculated for the three factors. The internal consistency was in the acceptable range (α = 0.75).

2.2.3 Antigay attitudes

The scales on antigay attitudes were taken from a survey of the German Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency (Küpper et al., 2017). For the present study, we selected the scales (i) classical sexual prejudice, (ii) modern sexual prejudice, and (iii) acceptance of violence. The scale on classical sexual prejudice consists of 10 items asking for agreement or disagreement to various statements on a 4-point Likert scale from “I totally agree” to “I do not agree.” These statements concerned equal rights for lesbian and gay people (e.g., “It is good that homosexual people are protected from discrimination by law”) as well as un-naturality or immorality of homosexuality (e.g., “Homosexuality is a disease”). The scale on modern sexual prejudice consists of 6 items and assesses the acceptance of homosexuality being a topic in the media or lesbian and gay people making their sexuality public (e.g., “Homosexuals should stop making such a fuss about their sexuality”; see also Morrison and Morrison, 2003). By contrast, the scale acceptance of violence consists of two items (“Lesbians and gays have themselves to blame if people react aggressively to them.” and “It is understandable if people use violence against gays and lesbians”). Participants could answer all items on a 4-point Likert scale from “I do not agree at all” to “I fully agree.” The overall scale antigay attitudes was formed on the basis of all three scales with an internal consistency in the excellent range (α = 0.95).

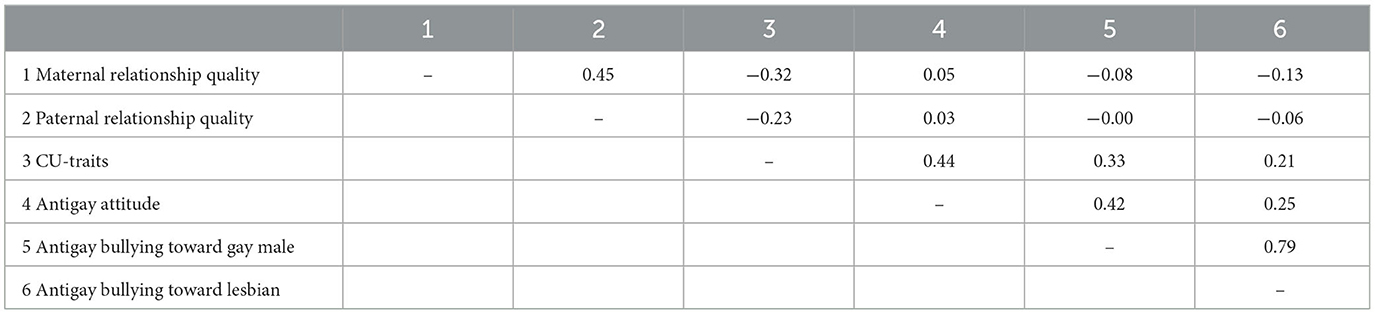

The Homophobic Bullying Scale (Prati, 2012) was used to assess antigay behavior. As this instrument is not yet available in the German language, the questionnaire was also translated and back-translated by two independent translators. The scale consists of 8 items and measures homophobic behavior toward gay and lesbian classmates separately according to three different perspectives (perpetrator, bystander, victim). In the present study, only the scale from the perpetrator's perspective was used (“Think of a student who is perceived as gay/lesbian. How often in the last 30 days have you ...”). The students could then indicate on a 4-point Likert scale from “never” to “more than 1 time per week” they had expressed antigay behavior (e.g., “excluded him/her,” “hit him/her,” “touched his/her private parts”). The internal consistency of both scales was in the good range (gay: α = 0.90; lesbian: α = 0.80). The correlations between all the variables of the present study are reported in Table 1.

2.3 Statistical analyses

First, we aimed to examine well-established gender differences in CU-traits and sexual prejudice (Essau et al., 2006; Fanti, 2013; Küpper et al., 2017; Orue and Calvete, 2018) using separate one-way ANOVAs with gender as between-subject factor. Second, we performed separate mediation analyses to assess the relationship between sexual prejudice, parental relationship quality and CU-traits on (i) antigay attitudes and (ii) antigay bullying. This analysis protocol goes in line with the analyses of D'Urso et al.'s (2020) using CU-traits instead of psychoticism as mediating variable.

Mediation analyses were calculated using the psych-package (Revelle, 2022) running in the R environment for statistical computing (R version 3.6.0). Calculation of the confidence intervals of indirect effects was based on bootstrapping with 10,000 replications. We focus on reporting our findings regarding antigay bullying toward men, as this is more common in our society than bullying against lesbian women (Moyano and del Mar Sánchez-Fuentes, 2020). Findings on bullying toward lesbian women can be found in our Supplementary Figure S1.

3 Results

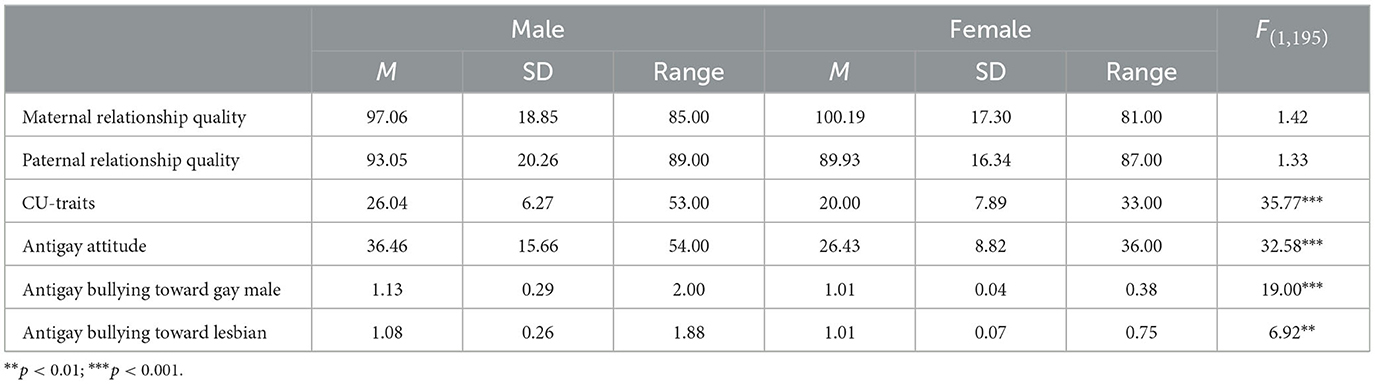

3.1 Gender differences

As shown in Table 2, our significant main effects revealed that males showed higher CU-traits, stronger antigay attitudes, and bullying compared to females (all Fs > 19). As discussed below, these results are consistent with the literature. As expected, no gender differences were found in maternal or paternal relationship quality.

3.2 Mediation analyses

3.2.1 Antigay attitudes

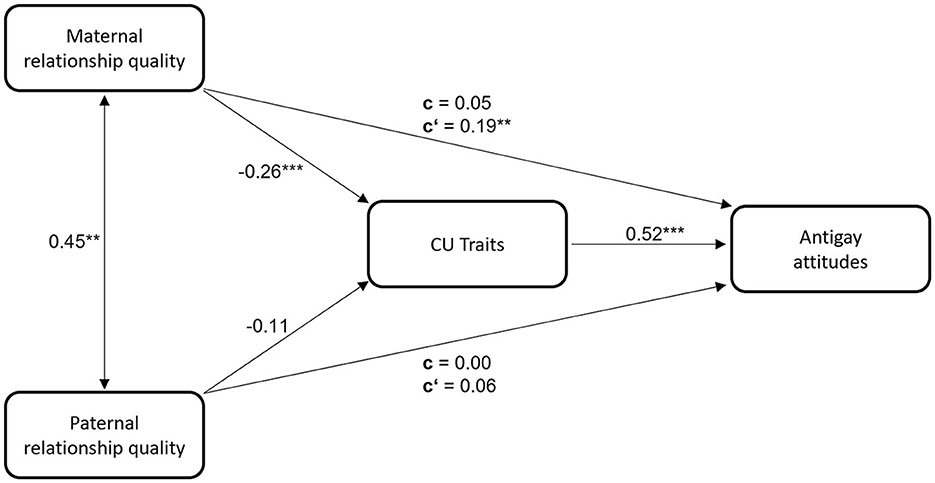

We tested the effect of maternal and paternal relationship quality on antigay attitudes, considering CU-traits as a mediator. As shown in Figure 1, the total effects of the model (c) were not significant, indicating that neither maternal nor paternal relationship quality by itself could predict antigay attitudes; β = 0.05, t(194) = 0.64, p = 0.52 and ß = 0.00, t(194) = 0.06, p = 0.95, respectively. However, lower maternal relationship quality was associated with higher CU-traits, β = −0.26, t(194) = −3.50, p < 0.001, and higher CU-traits in turn predicted stronger antigay attitudes, β = 0.52, t(193) = 7.78, p < 0.001. Of theoretical relevance is that we observed a significant indirect effect of maternal relationship quality on antigay attitudes via CU-traits, ß = −0.14, CI (−0.22, −0.06), with a residual direct effect (c') of maternal relationship quality on antigay attitudes ß = 0.19, t(193) = 2.60, p < 0.05. The indirect effect of paternal relationship quality on antigay attitudes via CU-traits was not significant ß = −0.06, CI (−0.15, 0.03), as was the association of paternal relationship quality with CU-traits, ß = −0.11, t(194) = −1.51, p = 0.13. The residual direct effect (c′) of paternal relationship quality on antigay attitudes was also not significant, ß = 0.06, t(194) = 0.91, p = 0.37.

Figure 1. Mediation model displaying effect estimates among paths affecting antigay hostile attitudes with total (c) and direct effects (c'). **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

3.2.2 Antigay bullying

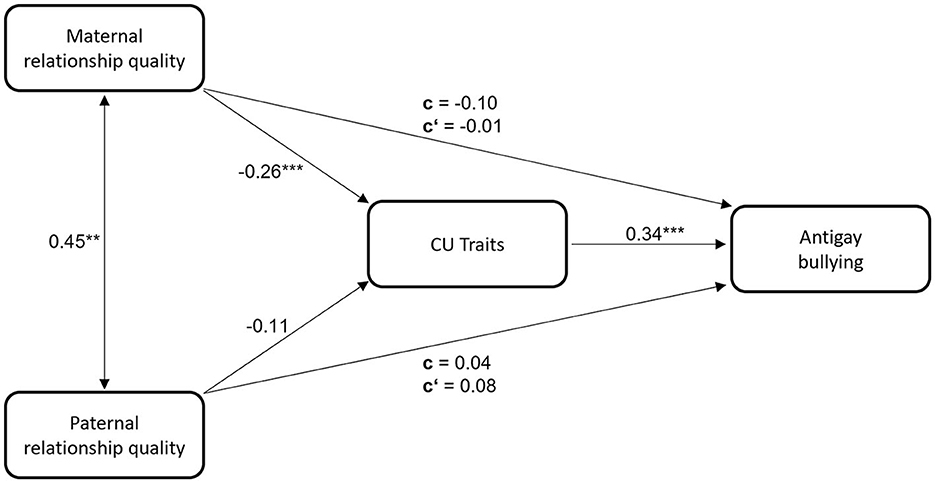

In this analysis, we examined the effect of maternal and paternal relationship quality on antigay bullying, again considering CU-traits as a mediator. As evident in Figure 2, again total effects of the model (c) were not significant, indicating that neither maternal nor paternal relationship quality by itself predicted antigay bullying, β = −0.10, t(194) = −1.28, p = 0.20; and β = 0.04, t(194) = 0.53, p = 0.60, respectively. However, lower maternal relationship quality was again associated with higher CU-traits β = −0.26, t(194) = −3.50, p < 0.001, and higher CU-traits in turn predicted stronger bullying, β = 0.34, t(193) = 4.76, p < 0.001. Critically, the indirect effect via CU-traits was significant in our model for maternal relationship quality, ß = −0.09, CI (−0.16, −0.04). In contrast, we observed no significant indirect effect for paternal relationship quality β = −0.04, CI (−0.10, 0.02). The residual direct effect (c′) was neither significant for maternal, β = −0.01, t(193) = −0.15, p = 0.88, nor for paternal relationship quality, β = 0.08, t(193) = 1.07, p = 0.29. An additional model for bulling toward lesbian women yielded similar results (see Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 2. Mediation model displaying effect estimates among paths affecting antigay bullying against men with total (c) and direct effects (c'). **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

4 Discussion

The present study investigated potential mechanisms for the emergence of sexual prejudice in adolescence. We focused on the role of parent-adolescent relationship quality in the development of psychopathic personality traits—so-called callous-unemotional (CU) traits—and their potential association with sexual prejudice as expressed by antigay hostile attitudes and bullying. Specifically, we were interested in whether the relationship between parent-adolescent relationship quality and sexual prejudice could be explained indirectly by variations in CU-traits. Our cross-sectional analyses revealed that poor maternal relationship quality in terms of poor quality of communication, a lack of mutual trust and a sense of alienation were associated with higher levels of CU-traits. Higher CU-traits, in consequence, were associated with more negative attitudes toward homosexual persons and higher incidences of antigay bullying. Critically, our analyses revealed an indirect effect of maternal attachment on sexual prejudice, with CU-traits mediating the effect.

The presently observed association between maternal and paternal relationship quality goes well in line recent with a meta-analysis on similarities (and differences) of child-mother and child-father attachment security (Pinquart, 2022). Specifically, although it has been observed that attachment security to mothers is greater than to fathers, the mean-level differences are very small and that there is a good correlation (r = 0.32) between the measured security of both caregivers (Pinquart, 2022). However, despite the presently observed association, paternal (as opposed to the maternal) relationship quality neither reliably predicted sexual prejudice, nor CU-traits. We speculate that this may be caused by the putative different functioning of mothers and fathers in child care; i.e., mothers are more likely to fulfill the “safe-haven” function of attachment e.g., by soothing distress (e.g., Umemura et al., 2013; Verschueren, 2020), while fathers are more likely to provide the secure base for exploration and regulation of intense, joyful emotions (e.g., StGeorge et al., 2018; Grossmann and Grossmann, 2020). The manifestation of CU-traits is supposed to be more related to the (in-)ability in comforting distress (Wright et al., 2018)—a finding which can be substantiated by the present study.

Our finding that adolescents who have a poor relationship with their mother also show higher levels of CU-traits is consistent with the literature pointing toward influential environmental risk factors for psychopathy such as, for example, early maltreatment, low parental warmth or parental indifference (for a review see van der Zouwen et al., 2018). Moreover, our finding that maternal relationship quality in particular is critically related to the development of psychopathic traits complements previous research (Kimonis et al., 2013; Bisby et al., 2017). The exact relationship between parent-adolescent relationship and CU-traits, namely whether pre-existing CU-traits in children might negatively affect the relationship with caregivers and thus may result in insecure attachment—or, whether CU-traits are the result of poor relationship quality or insecure attachment (van der Zouwen et al., 2018) is still subject to considerable debate with some advocating for a potential bi-directional relationship between parenting and CU-traits (Hawes et al., 2011). Of note, Dadds and Salmon (2003) proposed a certain punishment-insensitivity for a subset of children, i.e., those exhibiting conduct problems. Despite questions about the nature of the relationship, an association between insecure (or poor) attachment (relationship) quality and psychopathic traits has been well-documented (for a recent meta-analysis see van der Zouwen et al., 2018) and is further substantiated by our findings.

Consistent with previous findings, we observed substantial gender differences, with male participants exhibiting higher scores in CU-traits, holding significantly more antigay attitudes, and reporting to engage in antigay bullying more frequently than their female peers (Steffens and Wagner, 2004; Baier and Kamenowski, 2020). An explanation for this effect can be derived from the concept of hegemonic masculinity: those who do not conform to the predominant masculinity construct are devalued, excluded from the group, insulted or attacked (Scheibelhofer, 2018). This could also be observed in the present study, as the greatest aggression toward gay classmates came from male students.

However, we found no direct relationship between sexual prejudice, with either maternal or paternal relationship quality without CU-traits as a mediating variable. Our mediation analyses were theoretically motivated based on recent findings by D'Urso et al. (2020). In this study the authors observed a significant relation between homophobic bullying and parental relationship quality. Unexpectedly, we did not observe such a relationship in our sample of Austrian adolescents. As has been suggested, we do not want to overemphasize this seemingly missing link for the sake of theory testing and theory development (e.g., see Rucker et al., 2011).

Furthermore and as mentioned in the introduction, evidence regarding the relationship between sexual prejudice and parental relationship quality is scarce and mixed. Some studies report such a relationship between relationship quality and sexual prejudice (Ciocca et al., 2015; Maftei and Holman, 2021), while others did not find such an effect (Schwartz and Lindley, 2005; Metin-Orta and Metin-Camgöz, 2020). In contrast, for non-antigay-related delinquency and antisocial behavior such as bullying, there is evidence that poorly attached individuals are at higher risk of developing such tendencies (Eliot and Cornell, 2009; Walden and Beran, 2010; Nikiforou et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2017). Antigay bullying may represent a particular form of antisocial behavior for its multifaceted socio-ecological origin. For instance, deep faith and religious fundamentalism are strongly related to prejudice based on perceived sexual orientation (Siraj, 2012; Küpper et al., 2017; Baier and Kamenowski, 2020). Thus, one could argue that religion has the potential to function as a surrogate parental figure because it shares many characteristics of “conventional” parental functions, such as providing a secure base (Kirkpatrick and Shaver, 1990; Granqvist and Kirkpatrick, 2008; Granqvist et al., 2010), which complicates the direct relationship between relationship quality and sexual prejudice. One finding that merits further research is that the mediation model for antigay attitudes, weakly (though statistically significantly) suggests that (after accounting for the mediating effect of CU-traits) better relationship quality is associated with more negative attitudes.

That being said, we could show that high expression of CU-traits reliably predicted sexual prejudice in terms of hostile attitudes and behavior. This finding adds to previous research demonstrating strong connections of CU-traits with delinquency, bullying and externalizing behavior (van der Zouwen et al., 2018). The relative level of antigay behavior compared to hostile attitudes, however, was considerably lower. In this context, it is important to distinguish psychopathic traits (as measured by CU-traits) from actual psychopathy. That is, only individuals with psychopathic traits who also show antisocial behavior are considered psychopathic (Blair, 2001; Farrington, 2005). Thus, it is not surprising that the estimates in our mediation model for antigay bullying were considerably lower than those in the model for antigay attitudes. Further, one may argue that sexual prejudice in the present sample is—at that time of testing—mainly expressed by hostile attitudes toward people who identify themselves with the LGBTQIA+ community. Crucially, as Orue and Calvete (2018) reported in their longitudinal study that antigay attitudes predicted future antigay bullying. Thus, hostile attitudes already signal the urgency for appropriate timely interventions (Kimonis et al., 2019).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate a relationship between parent-adolescent relationship quality and sexual prejudice mediated by CU-traits. The mediation via CU-traits highlights the crucial role of (maternal) relationship quality on a child's affective personality traits and, as a consequence, on its tolerance toward people who have a sexual orientation that does not correspond to the heteronormative model. Providing children and adolescents a warm and sensitive environment may counteract the consolidation of psychopathic personality traits. Previous studies indicate that children with psychopathic tendencies are generally not responsive to punishment (Frick and White, 2008; Byrd et al., 2014). Thus, interventions promoting a good affective relationship with the child are generally more successful compared to traditional approaches (Dadds et al., 2014; Kimonis et al., 2019). Moreover, appropriate interventions not only foster the individual psychological wellbeing, but also positively impacts our society in terms of counteracting other concomitant negative effects on the side of the victims (e.g., anxiety disorders, substance abuse). Future studies may further investigate the factors that promote the development of sexual prejudice, hostile attitudes and violent behavior, taking into account psychopathic personality traits to further refine targeted intervention methods in adolescents.

5 Conclusions

Sexual prejudice has a negative impact on our society and is prevalent in school environments (Rivers and Cowie, 2006). The present study shows that psychopathic personality traits (CU-traits) mediate the relationship between maternal relationship quality and sexual prejudice, expressed through antigay attitudes and antigay bullying, in a sample of Austrian adolescents. Hostile attitudes have been reported to be predictive of future antigay bullying, thus already indicating the need for appropriate interventions (Kimonis et al., 2019). Fostering a good affective relationship in childhood may counteract deep manifestations of CU-traits and thus positively influence future social behavior.

6 Limitations

The cross-sectional design of the study impedes clear causal inferences regarding the directionality of parent-child relationship quality and CU-traits on sexual prejudice. As we already discussed, there is evidence that point toward a bidirectional influence of parenting and CU-traits, while some children seeming insensitive to punishment (Dadds and Salmon, 2003). Future studies may substantiate the findings of the present study by investigating mechanisms of parent-child relationship quality and CU-traits on sexual prejudice in a longitudinal design.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available upon request by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The research on human participants was approved by the Salzburg Education Directorate (IRB approval number 510003/0029-PA-ZV-IKT/2021). Written informed consent for participation from the participants' legal guardians/next of kin was not required in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

RB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing–original draft. SS: Formal analysis, Supervision, Visualization, Writing–original draft. FH: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stefan Reiß for his helpful comments during statistical analyses.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdpys.2023.1284404/full#supplementary-material

References

Ansel, L. L., Barry, C. T., Gillen, C. T. A., and Herrington, L. L. (2015). An analysis of four self-report measures of adolescent callous-unemotional traits: exploring unique prediction of delinquency, aggression, and conduct problems. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 37, 207–216. doi: 10.1007/s10862-014-9460-z

Armsden, G. C., and Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 16, 427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939

Baier, D., and Kamenowski, M. (2020). Verbreitung und einflussfaktoren von homophobie unter jugendlichen und erwachsenen. Befragungsbefunde aus der schweiz und deutschland. Rechtspsychologie 6, 5–35. doi: 10.5771/2365-1083-2020-1-5

Beaver, K. M., Vaughn, M. G., DeLisi, M., Barnes, J. C., and Boutwell, B. B. (2012). The neuropsychological underpinnings to psychopathic personality traits in a nationally representative and longitudinal sample. Psychiatr. Q. 83, 145–159. doi: 10.1007/s11126-011-9190-2

Bisby, M. A., Kimonis, E. R., and Goulter, N. (2017). Low maternal warmth mediates the relationship between emotional neglect and callous-unemotional traits among male juvenile offenders. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26, 1790–1798. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0719-3

Blair, R. J. R. (2001). Neurocognitive models of aggression, the antisocial personality disorders, and psychopathy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 71, 727–731. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.6.727

Boccardi, M., Frisoni, G. B., Hare, R. D., Cavedo, E., Najt, P., Pievani, M., et al. (2011). Cortex and amygdala morphology in psychopathy. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 193, 85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.12.013

Bowlby, J. (1944). Forty-four juvenile thieves: their characters and home-life. Int. J. Psychoanal. 25, 19.

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: retrospect and prospect. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 52, 664–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x

Bretherton, I. (2010). Fathers in attachment theory and research: a review. Early Child Dev. Care 180, 9–23. doi: 10.1080/03004430903414661

Byrd, A. L., Loeber, R., and Pardini, D. A. (2014). Antisocial behavior, psychopathic features and abnormalities in reward and punishment processing in youth. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 17, 125–156. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0159-6

Ciocca, G., Tuziak, B., Limoncin, E., Mollaioli, D., Capuano, N., Martini, A., et al. (2015). Psychoticism, immature defense mechanisms and a fearful attachment style are associated with a higher homophobic attitude. J. Sex. Med. 12, 1953–1960. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12975

Coid, J., Yang, M., Ullrich, S., and Roberts, A. (2009). Prevalence and correlates of psychopathic traits in the household population of Great Britain. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 32, 65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2009.01.002

Craig, M. C., Catani, M., Deeley, Q., Latham, R., Daly, E., Kanaan, R., et al. (2009). Altered connections on the road to psychopathy. Mol. Psychiatry 14, 946–953. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.40

Dadds, M. R., Allen, J. L., McGregor, K., Woolgar, M., Viding, E., Scott, S., et al. (2014). Callous-unemotional traits in children and mechanisms of impaired eye contact during expressions of love: a treatment target? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 55, 771–780. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12155

Dadds, M. R., and Salmon, K. (2003). Punishment insensitivity and parenting: temperament and learning as interacting risks for antisocial behavior. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 6, 69–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1023762009877

Dagan, O., and Sagi-Schwartz, A. (2018). Early attachment network with mother and father: an unsettled issue. Child Dev. Perspect. 12, 115–121. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12272

D'Urso, G., Petruccelli, I., and Pace, U. (2018). The interplay between trust among peers and interpersonal characteristics in homophobic bullying among italian adolescents. Sex. Cult. 22, 1310–1320. doi: 10.1007/s12119-018-9527-1

D'Urso, G., Symonds, J., and Pace, U. (2020). The role of psychoticism in the relationship between attachment to parents and homophobic bullying: a study in adolescence. Sexologies 29, e103–e110. doi: 10.1016/j.sexol.2020.08.005

Eliot, M., and Cornell, D. G. (2009). Bullying in middle school as a function of insecure attachment and aggressive attitudes. Sch. Psychol. Int. 30, 201–214. doi: 10.1177/0143034309104148

Espelage, D. L., Aragon, S. R., Birkett, M., and Koenig, B. W. (2008). Homophobic teasing, psychological outcomes, and sexual orientation among high school students: what influence do parents and schools have? School Psych. Rev. 37, 202–216. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2008.12087894

Essau, C. A., Sasagawa, S., and Frick, P. J. (2006). Callous-unemotional traits in a community sample of adolescents. Assessment 13, 454–469. doi: 10.1177/1073191106287354

Fagot, B. I., and Kavanagh, K. (1990). The prediction of antisocial behavior from avoidant attachment classifications. Child Dev. 61, 864–873. doi: 10.2307/1130970

Fanti, K. A. (2013). Individual, social, and behavioral factors associated with co-occurring conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 41, 811–824. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9726-z

Farrington, D. P. (2005). The importance of child and adolescent psychopathy. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 33, 489–497. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-5729-8

Fearon, R. P., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Lapsley, A.-M., and Roisman, G. I. (2010). The significance of insecure attachment and disorganization in the development of children's externalizing behavior: a meta-analytic study. Child Dev. 81, 435–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01405.x

Free, A. (2017). Longitudinal Associations Between Psychopathy, Bullying, Homophobic Taunting, and Sexual Harassment in Adolescence: Longitudinal Associations Between Psychopathy, Bullying, Homophobic Taunting, and Sexual Harassment in Adolescence [Université d'Ottawa / University of Ottawa]. DataCite. Available online at: https://ruor.uottawa.ca/handle/10393/35989 (accesed December 19, 2023).

Frick, P. J. (2004). The Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits. Unpublished Rating Scale. New Orleans, LA: UNO.

Frick, P. J., Stickle, T. R., Dandreaux, D. M., Farrell, J. M., and Kimonis, E. R. (2005). Callous-unemotional traits in predicting the severity and stability of conduct problems and delinquency. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 33, 471–487. doi: 10.1007/s10648-005-5728-9

Frick, P. J., and White, S. F. (2008). Research review: The importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 49, 359–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01862.x

Granqvist, P., and Kirkpatrick, L. A. (2008). “Attachment and religious representations and behavior,” in Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications, eds J. Cassidy, and P. R. Shaver (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 906–933.

Granqvist, P., Mikulincer, M., and Shaver, P. R. (2010). Religion as attachment: normative processes and individual differences. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 14, 49–59. doi: 10.1177/1088868309348618

Grossmann, K., and Grossmann, K. E. (2020). Essentials when studying child–father attachment: a fundamental view on safe haven and secure base phenomena. Attach. Hum. Dev. 22, 9–14. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2019.1589056

Hare, R. D. (2003). Manual for the Revised Psychopathy Checklist. Toronto, ON, Canada: Multi-Health Systems.

Hare, R. D. (2012). Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths Among Us. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Hawes, D. J., and Dadds, M. R. (2005). The treatment of conduct problems in children with callous-unemotional traits. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 73, 737–741. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.737

Hawes, D. J., Dadds, M. R., Frost, A. D., and Hasking, P. A. (2011). Do childhood callous-unemotional traits drive change in parenting practices? J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 40, 507–518. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.581624

Hawes, D. J., Price, M. J., and Dadds, M. R. (2014). Callous-unemotional traits and the treatment of conduct problems in childhood and adolescence: a comprehensive review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 17, 248–267. doi: 10.1007/s10567-014-0167-1

Herek, G. M. (2004). Beyond “homophobia”: thinking about sexual prejudice and stigma in the twenty-first century. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 1, 6–24. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2004.1.2.6

Herpers, P., Scheepers, F. E., Bons, D., Buitelaar, J. K., and Rommelse, N. N. (2014). The cognitive and neural correlates of psychopathy and especially callous–unemotional traits in youths: a systematic review of the evidence. Dev. Psychopathol. 26, 245–273. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000527

Kimonis, E. R., Cross, B., Howard, A., and Donoghue, K. (2013). Maternal care, maltreatment and callous-unemotional traits among urban male juvenile offenders. J. Youth Adolesc. 42, 165–177. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9820-5

Kimonis, E. R., Fleming, G., Briggs, N., Brouwer-French, L., Frick, P. J., Hawes, D. J., et al. (2019). Parent-child interaction therapy adapted for preschoolers with callous-unemotional traits: an open trial pilot study. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 48, 347–361. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1479966

Kirkpatrick, L. A., and Shaver, P. R. (1990). Attachment theory and religion: childhood attachments, religious beliefs, and conversion. J. Sci. Study Relig. 29, 315–334. doi: 10.2307/1386461

Klocke, U. (2012). Akzeptanz sexueller Vielfalt an Berliner Schulen: Eine Befragung zu Verhalten, Ein-stellungen und Wissen zu LSBT und deren Einflussvariablen. Berlin: Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Jugend und Wissenschaft.

Küpper, B., Klocke, U., and Hoffmann, L.-C. (2017). Einstellungen Gegenüber Lesbischen, Schwulen und Bisexuellen Menschen in Deutschland. Deutschland: Im Auftrag der Antidsikrimminierungsstelle des Bundes.

Lamb, M. A. (2013). “The changing faces of fatherhood and father–child relationships: From fatherhood as status to fatherhood as dad,” in Handbook of Family Theories: A Content-Based Approach, eds M. A. Fine, and F. D. Fincham (London: Routledge), 87–102.

Maftei, A., and Holman, A.-C. (2021). Predictors of homophobia in a sample of Romanian young adults: age, gender, spirituality, attachment styles, and moral disengagement. Psychol. Sex. 12, 305–316. doi: 10.1080/19419899.2020.1726435

Mann, F. D., Briley, D. A., Tucker-Drob, E. M., and Harden, K. P. (2015). A behavioral genetic analysis of callous-unemotional traits and Big Five personality in adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 124, 982–993. doi: 10.1037/abn0000099

Metin-Orta, I., and Metin-Camgöz, S. (2020). Attachment style, openness to experience, and social contact as predictors of attitudes toward homosexuality. J. Homosex. 67, 528–553. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2018.1547562

Morrison, M. A., and Morrison, T. G. (2003). Development and validation of a scale measuring modern prejudice toward gay men and lesbian women. J. Homosex. 43, 15–37. doi: 10.1300/J082v43n02_02

Moyano, N., and del Mar Sánchez-Fuentes, M. (2020). Homophobic bullying at schools: a systematic review of research, prevalence, school-related predictors and consequences. Aggress. Violent Behav. 53, 101441. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2020.101441

Murphy, T. P., Laible, D., and Augustine, M. (2017). The influences of parent and peer attachment on bullying. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26, 1388–1397. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0663-2

Nikiforou, M., Georgiou, S. N., and Stavrinides, P. (2013). Attachment to parents and peers as a parameter of bullying and victimization. J. Criminol. 1, 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2013/484871

Orue, I., and Calvete, E. (2018). Homophobic bullying in schools: the role of homophobic attitudes and exposure to homophobic aggression. School Psych. Rev. 47, 95–105. doi: 10.17105/SPR-2017-0063.V47-1

Pinquart, M. (2022). Attachment security to mothers and fathers: a meta-analysis on mean-level differences and correlations of behavioural measures. Infant Child Dev. 31, e2364. doi: 10.1002/icd.2364

Prati, G. (2012). Development and psychometric properties of the homophobic bullying scale. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 72, 649–664. doi: 10.1177/0013164412440169

Revelle, W. (2022). psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. R package version 2.2.9. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych (accesed December 19, 2023).

Rivers, I. (2011). Homophobic Bullying: Research and Theoretical Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195160536.001.0001

Rivers, I., and Cowie, H. (2006). Bullying and homophobia in UK schools: a perspective on factors affecting resilience and recovery. J. Gay Lesbian Issues Educ. 3, 11–43. doi: 10.1300/J367v03n04_03

Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., and Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: current practices and new recommendations. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass, 5, 359–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x

Scheibelhofer, P. (2018). ““Du bist so schwul!” homophobie und männlichkeit in schulkontexten,” in Sexualität, Macht und Gewalt, eds S. Arzt, C. Brunnauer, and B. Schartner (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 35–50. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-19602-8_3

Schindler, A., and Bröning, S. (2015). A review on attachment and adolescent substance abuse: empirical evidence and implications for prevention and treatment. Substance Abuse 36, 304–313. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.983586

Schore, A. N. (2001). Effects of a secure attachment relationship on right brain development, affect regulation and infant mental health. Infant Ment. Health J. 22, 7–66. doi: 10.1002/1097-0355(200101/04)22:1<7::AID-IMHJ2>3.0.CO;2-N

Schwartz, J. P., and Lindley, L. D. (2005). Religious fundamentalism and attachment: prediction of homophobia. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 15, 145–157. doi: 10.1207/s15327582ijpr1502_3

Simpson, J. A. (1990). Influence of attachment styles on romantic relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 59, 971–980. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.971

Siraj, A. (2012). “I don't want to taint the name of Islam”: the influence of religion on the lives of Muslim lesbians. J. Lesbian Stud. 16, 449–467. doi: 10.1080/10894160.2012.681268

Steffens, M., and Wagner, C. (2004). Attitudes toward lesbians, gay men, bisexual women, and bisexual men in Germany. J. Sex Res. 41, 137–149. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552222

StGeorge, J. M., Wroe, J. K., and Cashin, M. E. (2018). The concept and measurement of fathers' stimulating play: a review. Attach. Hum. Dev. 20, 634–658. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2018.1465106

Swearer, S. M., Espelage, D. L., Vaillancourt, T., and Hymel, S. (2010). What can be done about school bullying? Educ. Res. 39, 38–47. doi: 10.3102/0013189X09357622

Tuvblad, C., Bezdjian, S., Raine, A., and Baker, L. A. (2014). The heritability of psychopathic personality in 14-to 15-year-old twins: a multirater, multimeasure approach. Psychol. Assess. 26, 704. doi: 10.1037/a0036711

Umemura, T., Jacobvitz, D., Messina, S. T., and Hazen, N. (2013). Do toddlers prefer the primary caregiver or the parent with whom they feel more secure? The role of toddler emotion. Infant Behav. Dev. 36, 102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.10.003

van der Zouwen, M., Hoeve, M., Hendriks, A. M., Asscher, J. J., and Stams, G. J. J. M. (2018). The association between attachment and psychopathic traits. Aggress. Violent Behav. 43, 45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.09.002

Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Sagi, A., and Lambermon, M. W. E. (1992). The multiple caretaker paradox: data from Holland and Israel. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 57, 5–24. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219925703

Verhage, M. L., Schuengel, C., Madigan, S., Fearon, R. M. P., Oosterman, M., Cassibba, R., et al. (2016). Narrowing the transmission gap: a synthesis of three decades of research on intergenerational transmission of attachment. Psychol. Bull. 142, 337–366. doi: 10.1037/bul0000038

Verschueren, K. (2020). Attachment, self-esteem, and socio-emotional adjustment: there is more than just the mother. Attach. Human Dev. 22, 105–109. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2019.1589066

Viding, E., Simmonds, E., Petrides, K. V., and Frederickson, N. (2009). The contribution of callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems to bullying in early adolescence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 50, 471–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02012.x

Walden, L. M., and Beran, T. N. (2010). Attachment quality and bullying behavior in school-aged youth. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 25, 5–18. doi: 10.1177/0829573509357046

Keywords: parent-adolescent relationship quality, sexual prejudice, adolescence, callous-unemotional traits, psychopathy

Citation: Bruckner R, Schuster S and Hutzler F (2024) The role of parent-adolescent relationship quality and callous-unemotional traits on sexual prejudice in adolescence. Front. Dev. Psychol. 1:1284404. doi: 10.3389/fdpys.2023.1284404

Received: 28 August 2023; Accepted: 11 December 2023;

Published: 05 January 2024.

Edited by:

Mengya Xia, Arizona State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Silje Sommer Hukkelberg, The Norwegian Center for Child Behavioral Development (NCCBD), NorwayXiaobo Xu, Shanghai Normal University, China

Copyright © 2024 Bruckner, Schuster and Hutzler. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Florian Hutzler, Rmxvcmlhbi5IdXR6bGVyQHBsdXMuYWMuYXQ=; Sarah Schuster, U2FyYWguU2NodXN0ZXJAcGx1cy5hYy5hdA==

Raffael Bruckner

Raffael Bruckner Sarah Schuster

Sarah Schuster Florian Hutzler*

Florian Hutzler*