- 1Analytics and Evaluation, CareQuest Institute for Oral Health, Boston, MA, United States

- 2Department of Oral Health Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

Objectives: We hypothesized that individuals with dental care-related anxiety and fear would interpret ambiguous dental situations more negatively than non-anxious individuals. The objectives of these studies were to develop and test a Measure of Dental Anxiety Interpretational Bias (MoDAIB).

Methods: In the development phase, participants completing an online survey provided qualitative and quantitative assessments of dental scenarios that could be interpreted in either positive or negative ways. Scenarios producing the greatest difference in visual analog (VAS) scores between individuals with high vs. low dental anxiety as measured by the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) were included in the MoDAIB. In the testing phase, participants completed an online survey including the newly developed MoDAIB and dental anxiety measures.

Results: In the development phase, participants (N = 355; 65.6% female) high in dental anxiety (MDAS ≥ 19) gave significantly higher (i.e., more negative) VAS scores to all the dental scenarios than did those low in dental anxiety (p's < 0.05). In the testing phase, the MoDAIB was significantly and positively correlated with the MDAS (r = 0.68, p < 0.001), meaning that those who were high in dental anxiety selected negative interpretations of ambiguous dental scenarios significantly more often than did individuals low in dental anxiety (p's < 0.05). The MoDAIB showed good content validity and test-retest reliability.

Conclusions: Individuals high in dental anxiety interpret ambiguous dental situations more negatively than do less anxious individuals. Understanding individuals' interpretational styles may help dental providers avoid miscommunications. Interventions that train dentally anxious patients to consider more positive interpretations may reduce dental anxiety and should be investigated.

Introduction

Dental care-related anxiety and fear is well-established as a significant barrier to receiving dental treatment, leading 5–10% of adults in the United States to avoid necessary dental care (1). As described by McNeil and Randall (2), dental care-related fear occurs in response to treatment-related stimuli, often in the form of physiological reactivity, apprehension, and avoidance of the feared stimuli. Dental care-related anxiety, meanwhile, is described as “a more cognitively-involved emotional response to stimuli or experiences associated with dental treatment.” Much of the discussion of this paper will focus on “cognitively-involved emotional response(s)” (2), particularly related to negative thoughts and worries. Thus, the term “dental anxiety” will be used as shorthand for the concept of dental care-related anxiety and fear throughout this article, while acknowledging the complexity of the latter as a more precise and inclusive construct across individuals.

A commonly-cited model of the development and maintenance of dental anxiety is the “cycle of avoidance,” in which the development of dental anxiety is predicated on a negative dental experience (3, 4). Fear of re-experiencing this experience leads to avoiding dental treatment, setting up the need for more invasive dental treatment, further reinforcing the perception of dental treatment as traumatic and painful (3, 4). Yet, the existence of a traumatic event is not required for the establishment or maintenance of dental anxiety. De Jongh et al. found no difference in the severity of dental anxiety between individuals with or without a history of a traumatic dental experience (5). A similar study found no difference in the number of self-reported “horrific” dental experiences recalled between individuals seeking treatment in a specialized dental anxiety clinic vs. a general dental clinic (6).

Anxious individuals are more likely than non-anxious control subjects “to interpret…ambiguous sentences in a threatening fashion” (7). This interpretational bias has been shown to exist in individuals with: (1) social anxiety disorder (8), (2) generalized trait anxiety (9), and (3) chronic pain (10). Steinman and Teachman, for example, developed a four-factor measure to assess “height fear-relevant interpretation bias” in individuals with acrophobia (fear of heights) (11). The Heights Interpretation Questionnaire (HIQ) presents various height-relevant scenarios and asks individuals to imagine themselves in such scenarios then indicate the likelihood of interpretations of each scenario (e.g., “you will fall”). The authors found that the HIQ strongly predicted fear and avoidance related to heights above that provided by a previous measure of acrophobia symptoms (11).

Could interpretational bias help explain why dentally anxious individuals maintain their dental anxiety, even without traumatic dental experiences? In a qualitative study of 20 adults seeking treatment in a dental sedation clinic in the United Kingdom, one participant described racing thoughts in anticipation of dental treatment: “…my brain goes at a thousand miles an hour, everything from…what's he gonna say, is, I cannot even begin to describe the number of thoughts that go through my head.” (12). On the self-help website “Dental Fear Central” (www.dentalfearcentral.org), one commenter notes, “If you suffer with dental phobia, it is possible that you'll interpret remarks which others might simply regard as helpful advice or fair commentary as negative – and pretty devastating.” (13).

Research has suggested training anxious individuals to endorse neutral or positive interpretation of an ambiguous stimulus can counteract the individual's bias toward making negative, anxiety-inducing interpretations and result in reductions in self-reported anxiety (14, 15). The first step in developing this treatment is to identify how individuals high and low in dental anxiety interpret ambiguous dental situations. To do this, we asked people high and low in dental anxiety to assess ambiguous dental scenarios both qualitatively and quantitatively. Our goal was to develop a measure of interpretational bias [Measure of Dental Anxiety Interpretational Bias (MoDAIB)] and determine if it can reliably assess whether a dentally anxious individual has a negative interpretational bias toward dental situations.

Materials and Methods

Development Phase

Based on five factors of dental anxiety (16–18), we developed six scenarios for each of the five factors resulting in 30 ambiguous dental scenarios (Table 1 for examples). The five factors of dental anxiety reflect those determined in previous research (16–18) as well as unpublished data from the authors that mirror this prior work. For each of the five factors (named Interpersonal, Fear of Pain, Anticipation, Worry, and Medical Catastrophe), the Principal Investigator (PI; LJH) developed several ambiguous dental scenarios based on her clinical experience treating dentally anxious individuals. The research team (LJH, BGL, and DSR) then discussed, revised, and ultimately selected 6 scenarios for each of the 5 factors to create a 30-item subset of questions for the survey.

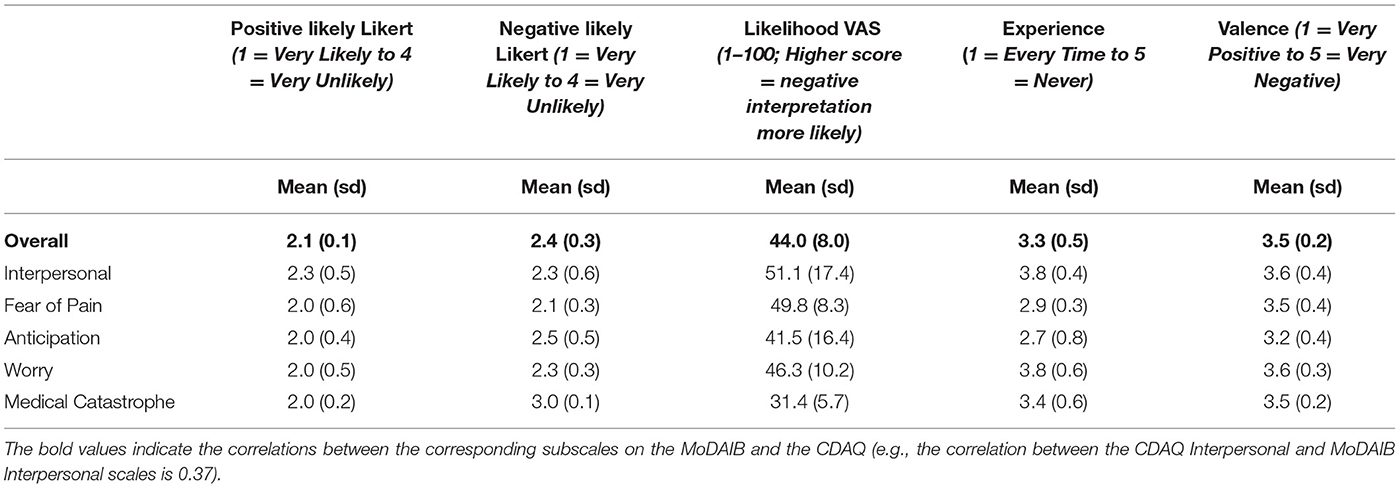

Table 1. Development phase categories, selected ambiguous dental scenarios, interpretations, and qualitative comments.

Between March 7, 2019, and July 5, 2019, we recruited participants (adults aged ≥ 18) through Craigslist advertisements across 55 major cities across the United States to provide quantitative and qualitative evaluations of 5 scenarios each. Two similar advertisements were developed to target both individuals high in dental anxiety (“Are you afraid of the dentist?”) and individuals with less dental anxiety (“Tell us how you feel about going to the dentist!”) to recruit individuals with various levels of dental anxiety and oversample for high dental anxiety. These two advertisements did not run in the same city simultaneously and were rotated across randomly selected local Craigslist sites every 3 days during the study period.

Participants completed a randomly selected subset of five scenarios (one from each factor) online through SurveyMonkey. Participants could enter their email addresses for a random drawing to win one of several Amazon.com electronic gift cards.

Measures

In addition to questions related to the scenarios (see below) and demographic variables, participants completed the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) (19). The MDAS is a 5-item scale assessing anticipatory anxiety related to different aspects of dental care. Scores range from 5 to 25, with higher scores indicating higher levels of dental anxiety. The MDAS has high internal consistency and good construct validity (20). Demographic variables included questions regarding age in years; gender (male, female, prefer not to say, prefer to self-identify with an open-ended text box); state of primary residence in the United States (selected from a pull-down menu); highest level of education achieved (less than high school; high school/General Education Development (GED) diploma; Associate's (2-year) degree; some college/university; Bachelor's (4-year) degree; some graduate work; Master's Degree; Doctoral Degree (e.g., PhD, MD, JD or other professional degree); other with an open-ended text box); time since last visit to a dentist (<6 months ago; 6–12 months ago; 1–2 years ago; 2–5 years ago; 5–10 years ago; more than 10 years ago); and reason for most recent dental visit (routine/scheduled treatment (cleaning, examination, filling); emergency (treatment due to pain or injury); other with an open-ended text box).

Participants rated 5 ambiguous scenarios (one for each factor) using several qualitative and quantitative methods, as described below and in the following order.

Qualitative Interpretation

Participants were given a description of a neutral dental scenario and then asked, “In the following [text] box, and in a sentence or two, please describe what you would think if you were the patient in this situation.” Participants were asked to provide their own interpretation prior to reading any other interpretations to get their unbiased description of the scenario. The qualitative results were used primarily to provide guidance in selecting scenarios for the Testing Phase and are not presented in this article.

Likelihood Likert-Type Rating

Participants were then shown, one at a time, two potential interpretations of the situation, namely one positive and one negative (half of the participants saw the positive interpretation first, the other half had the negative interpretation first). They were asked to indicate how likely they thought each of the two interpretations was on a 4-point Likert-type scale, from 1 = Very Likely to 4 = Very Unlikely.

Likelihood Visual Analog Scale (VAS) Rating

Participants were shown a 100-milimeter horizontal VAS scale with the positive and negative interpretations anchoring either end (see Table 1 for interpretations), along which they moved a slider to indicate how positive or negative they rated each scenario. The presentation of the positive and negative interpretations on the left side of the VAS (i.e., seen first when reading left-to-right) was counterbalanced across participants.

Prior Experience

For each of the 5 scenarios they read, each participant was asked, “How often has this situation happened to you in any dental office?” Responses ranged from 1 (Every Time) to 5 (Never).

Emotional Valence

For each of the 5 scenarios they read, each participant was asked, “How positive or negative do you feel this situation is?” Responses ranged from 1 (Very Positive) to 5 (Very Negative).

Testing Phase

Based on the results of the first study, the MoDAIB was reduced from 30 to 20 scenarios; the scenarios that showed the greatest difference in VAS scores between individuals high in dental anxiety (MDAS ≥ 19) and the rest of the sample (MDAS ≤ 19) were used in the MoDAIB in the Testing Phase. Between November 15, 2019, and April 25, 2020, we recruited participants (adults aged ≥ 18) through local Craigslist advertisements using the same recruitment and incentive strategy as in the Development Phase.

The test-retest reliability of the MoDAIB was assessed by giving participants the opportunity to enter their email addresses to be invited to take the survey a second time 2 weeks after completing the survey the first time. Individuals participating twice were given a second opportunity to win one of the gift cards.

Measures

Participants completed 20 items reflecting 20 scenarios (6 Medical Catastrophe, 5 Fear of Pain, 4 Anticipation, 3 Interpersonal, 2 Worry), the MDAS, and a 25-item, 5-factor Comprehensive Dental Anxiety Questionnaire (CDAQ) (16, 18–20). The CDAQ, developed by the authors, contains 25 items taken from other dental anxiety and general anxiety measures across the same five factors (subscales) as the MoDAIB (19, 21–26). Based on unpublished data by the authors, the CDAQ has a strong correlation with the MDAS (r = 0.81). The MDAS and CDAQ were included to assess the content validity of the MoDAIB. Participants were randomized to complete either the MoDAIB first or the MDAS and CDAQ first.

For each MoDAIB item, participants were asked to select which of two interpretations (1 = positive or 2 = negative) they thought was the most likely explanation of the scenario. Scores ranged from 20 to 40, with a higher score indicating more negative interpretations. The presentation order of positive and negative interpretations was counterbalanced across participants.

Statistical Analyses

Development Phase

Demographic data were assessed using descriptive statistics (means, frequencies), correlation coefficients, and chi-square analyses. Independent sample t-tests were used to test differences in means between participants high in dental anxiety (MDAS ≥ 19) and those with less dental anxiety (MDAS ≤ 18) on their likelihood Likert-type ratings and likelihood VAS ratings. Independent t-tests were also used to test differences in likelihood Likert-type ratings and likelihood VAS ratings for positive and negative scenarios.

Testing Phase

Demographic data were assessed using descriptive statistics (means, frequencies), correlation coefficients, and chi-squared analyses. Independent sample t-tests were used to test differences in means between participants high in dental anxiety and the rest of the sample on the overall MoDAIB. Correlations were computed between the MoDAIB, MDAS, and CDAQ.

Test-Retest Phase

Demographic data were assessed using descriptive statistics (means, frequencies). Correlations were calculated for the MoDAIB, the MDAS, and the CDAQ, comparing scores at Time 1 and Time 2, which were ~2 weeks apart.

This study and all its phases were reviewed in February 2019 and determined to be exempt from Human Subjects review by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Results

Development Phase

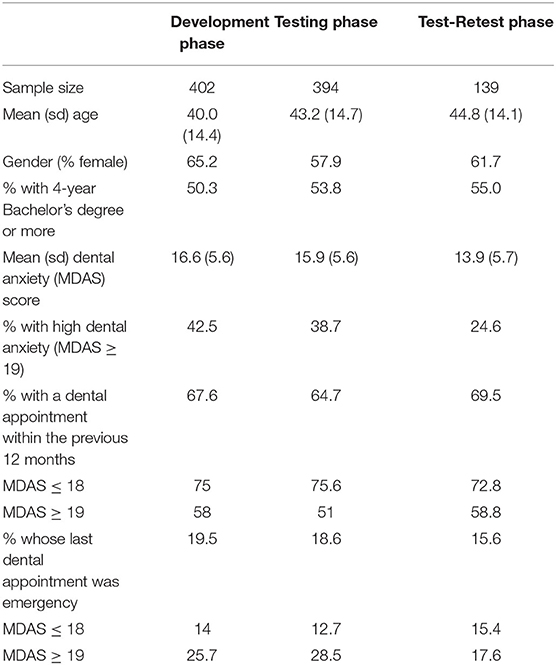

Four hundred and two participants (mean age = 40.0, sd = 14.4, range = 18–85, 65.2% female) completed the survey for the first phase (see Table 2). The average MDAS score was 16.6 (sd = 5.6, range 5–25); 171 participants (42.5%) reported high dental anxiety (MDAS ≥ 19). Dental anxiety was not significantly associated with age (r = −0.005, p = 0.93), gender (t = 1.77, p = 0.08), or education (F = 1.9, p = 0.06). Participants high in dental anxiety were less likely to have seen a dentist within the previous 12 months and more likely to have last seen a dentist for emergency treatment than less anxious participants (p's < 0.05, see Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of participants in development phase, testing phase, and test-retest testing sub-sample.

Except for one question, there were no significant differences between counterbalanced forms. That is, participants answered all but one question the same whether they were presented with a positive or negative explanation first. Participants only differed in their rating of emotional valence on one scenario based on order effects. Participants were asked how positive or negative they felt the following scenario was: “The dentist comes into the room, sits down, and looks at your x-rays. While looking at your x-rays, the dentist sighs heavily.” Participants who saw the positive explanation first (“You think the dentist has had a long day and is tired”) rated this scenario more negatively, that is, higher on the 5-point Likert scale (1 = Very Positive, 5 = Very Negative), than those who saw the negative explanation first (“You think the dentist has seen something concerning on your x-ray”; 4.42 (sd = 0.65) vs. 2.43 (sd = 1.12); t = 7.44, p < 0.001).

Qualitative

Table 1 provides examples of interpretations participants gave before they were given positive or negative interpretations to rate for each scenario. As noted above, the qualitative results were used primarily to provide guidance in selecting scenarios for the Testing Phase, and analyses related to these data are not presented in this article.

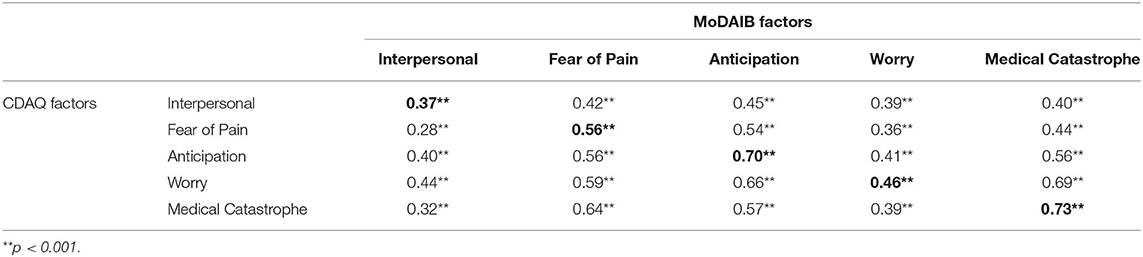

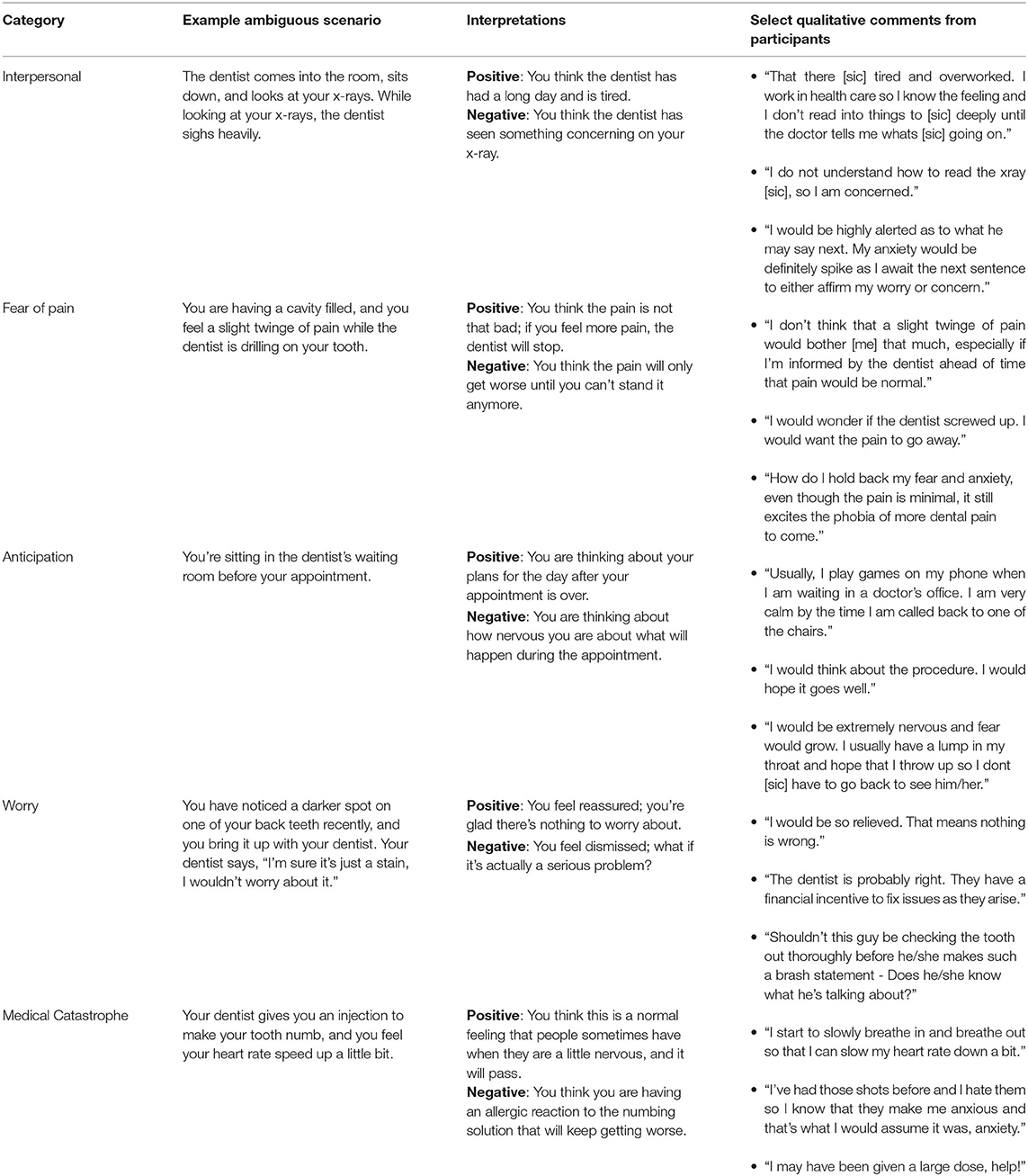

Likelihood Likert-Type Rating

The mean likelihood rating for positive interpretations overall was 2.1 (sd = 0.1), while the mean likelihood rating for negative interpretations overall was 2.4 (sd = 0.3; see Table 3), suggesting that participants thought the positive interpretations were slightly more likely than the negative interpretations. Table 3 provides mean ratings by factor.

Except for the Interpersonal scenarios (t = 0.121, p = 0.243), individuals with high dental anxiety rated positive explanations for the ambiguous scenarios as being significantly less likely (p's < 0.05) and negative explanations for the ambiguous scenarios as being significantly more likely than participants lower in dental anxiety (p's < 0.05).

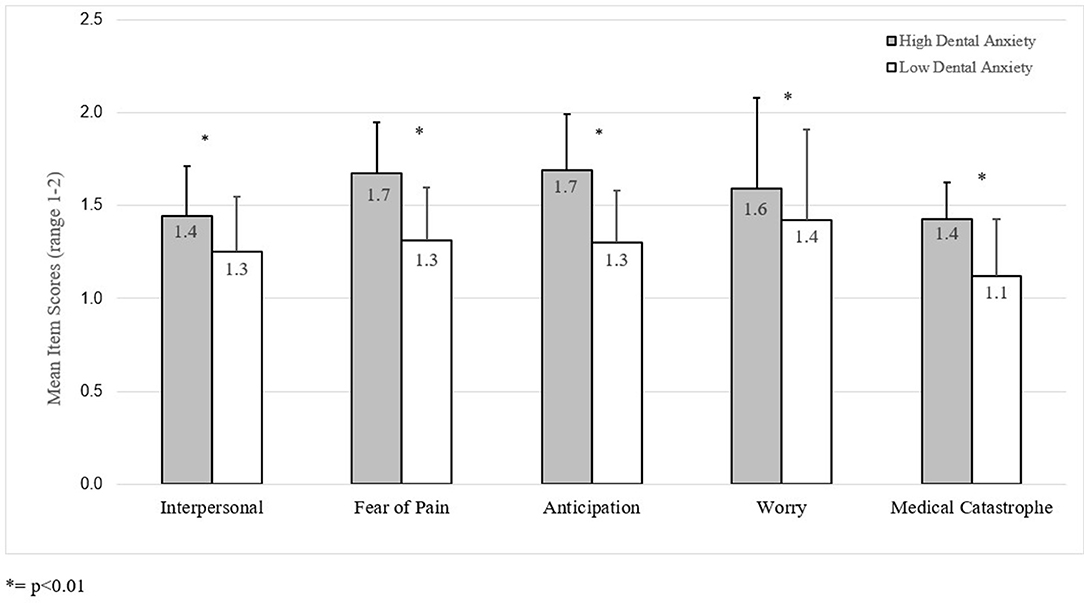

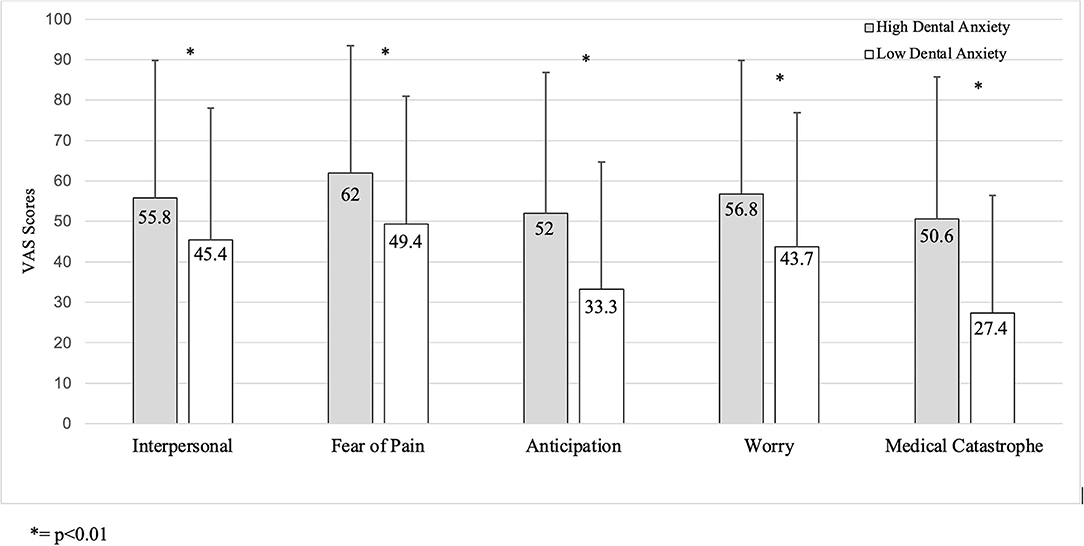

VAS Ratings

The mean VAS rating across all factors was 44.0 (sd = 8.0). Individuals high in dental anxiety rated negative scenarios as more likely across all types of scenarios significantly more often than individuals lower in dental anxiety as evidenced by significantly higher VAS ratings between those high in dental anxiety and lower in dental anxiety (p's <0.01; see Figure 1 for VAS ratings).

Figure 1. VAS ratings by MDAS dental anxiety scores from Development Phase (higher scores indicate more negative interpretation).

Prior Experience

Across all scenarios, individuals high in dental anxiety were less likely to report the scenario had happened to them in any dental office compared to participants lower in dental anxiety (p's <0.01).

Emotional Valence

Except for the Worry scenarios (t = 1.7, p = 0.09), participants high in dental anxiety rated all other scenarios as significantly more negative compared to those lower in dental anxiety (p's <0.05).

Testing Phase

In the Testing Phase (data from the test-retest subsample are presented separately below), 394 adults (mean age = 43.2 years, sd = 14.7, range = 18–78; 57.9% female) completed the survey (see Tables 2, 4). Results of the Testing Phase do not include those for the Test-Retest Phase (N = 139), presented below. The average MDAS score was 15.9 (sd = 5.6, range 5–25). One hundred and forty-four participants (38.7%) reported high dental anxiety (MDAS ≥ 19). Participants identifying as female reported higher MDAS scores (mean = 16.6, sd = 5.4) than those identifying as male (mean = 14.8, sd = 6.1; t = 2.8, p < 0.01). There was no correlation between dental anxiety and age (r = 0.024, p = 0.647). Participants high in dental anxiety were less likely to have seen a dentist within the previous 12 months and more likely to have last seen a dentist for emergency treatment than less anxious participants (p's <0.001, see Table 2).

The mean MoDAIB score was 27.1 (sd = 5.1, range 20–40). Participants high in dental anxiety scored significantly higher on the MoDAIB (mean = 31.1, sd = 4.5) than the rest of the sample (mean = 24.8, sd = 3.8; t = 14.0, p < 0.001) (Figure 2). The MoDAIB was significantly and positively correlated with the MDAS (r = 0.68, p < 0.001) and the CDAQ (r = 0.80, p < 0.001). The MoDAIB factors and corresponding CDAQ factors were significantly and positively correlated with one another (p's <0.001; see Table 5).

Test-Retest Phase

One hundred and thirty-nine participants (mean age = 44.8, sd = 14.1, range = 21–78; see Table 2) completed two administrations of the survey, an average of 14.1 days apart (sd = 6.6, range = 14–35 days). Those who completed the survey twice were 54.5% of those invited to retake the survey (139 of 255), and 35.3% of the 394 who participated in the first administration of the survey.

At Time 2, the mean MoDAIB score was 25.9 (sd = 5.0, range 20–40). As in Time 1, participants high in dental anxiety scored significantly higher (mean = 31.3, sd = 4.1) on the MoDAIB than those low in dental anxiety (mean = 24.0, sd = 3.8; t = 9.5, p < 0.001). The test-retest reliability of the MoDAIB (e.g., the correlation between the Time 1 and Time 2 administrations) was 0.89 (p < 0.0001). This was similar to the test-retest reliability indices of the MDAS (0.88, p < 0.0001) and the CDAQ (0.95, p < 0.0001). The MoDAIB was significantly correlated with both other measures both at Time 1 (r's between 0.68 and 0.88, p's <0.0001) and Time 2 (r's between 0.75 and 0.81, p's <0.0001), suggesting a high level of content validity for the MoDAIB.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first set of studies to investigate interpretational bias in dental anxiety and to develop a measure of this bias. We found that individuals high in dental anxiety interpreted ambiguous dental scenarios more negatively than individuals low in dental anxiety. We also found that this dental interpretational bias can be reliably assessed using a 20-item measure, and that this measure correlates highly with previously validated measures of dental anxiety.

While some evidence exists that dental anxiety can be caused by aversive dental experiences (3, 4), there is also evidence that a person's cognitions play a key role in maintaining dental anxiety (27, 28). The dental setting presents ambiguous and uncertain situations for many patients, and patients can easily differ from one another in how they interpret the same situation. In the Development phase, we determined which scenarios produced the greatest difference in positive/negative VAS ratings between those with high dental anxiety and the rest of the sample for inclusion in the MoDAIB. We began with six scenarios in each of the five factors. Interestingly, while most or all the Medical Catastrophe (6 of 6), Fear of Pain (5), and Anticipation (4) scenarios were retained, only 3 Interpersonal and 2 Worry scenarios were kept for the MoDAIB. Scenarios related to Medical Catastrophe and Fear of Pain address physical sensations, both painful and non-painful, experienced during dental treatment. Similarly, Anticipation scenarios reflect looking ahead to such physical and possibly painful sensations, such as sitting in the waiting room or in the dental chair before dental treatment begins. Meanwhile, Interpersonal and Worry scenarios may reflect less imminent or less threatening issues, such as the front office staff member being annoyed at a patient arriving late.

Individuals with high levels of dental anxiety anticipate dental treatment to be more painful than those low in dental anxiety (29, 30), and there is evidence that individuals are more anxious about dental procedures they have not yet experienced (31, 32). In our sample, individuals with high dental anxiety were less likely to report that they had experienced the scenarios than were other participants. MoDAIB scenarios representing painful and non-painful physical sensations may be at the same time less familiar but also more relevant to dentally anxious individuals.

Cognitive-behavioral interventions can be designed to modify a person's negative interpretations in the context of dentistry (the “cognitive” in “cognitive-behavioral”) (33). The therapeutic strategy known as Cognitive Bias Modification (CBM), is a way of “modifying bias in information processing” (34), and aims to change a person's bias toward threatening situations, thereby reducing their anxiety. In a meta-analysis of CBM for social anxiety disorder, Liu and colleagues found a greater effect for interpretational bias than for attentional bias (35).

Findings from our study do not allow us to make generalized statements regarding the interpretation style of all individuals with high levels of dental anxiety, and interventions for dental anxiety should be tailored in each case to account for individual differences in the experience of dental anxiety. As a part of a screening, the MoDAIB can give the dental team important knowledge of how their particular patient interprets the dental setting. If a patient scores highly on the MoDAIB, it can tell the dentist that this patient is more likely than not to interpret ambiguous situations negatively, which may further exacerbate their dental anxiety and impede treatment progress. Patients with a more negative interpretational bias (as measured by a high MoDAIB score) may benefit from more explicit communication from the dental team about the proposed treatments and what the patients can expect during procedures as far as physical sensations.

Limitations

Although individuals were recruited from across the United States using Craigslist and oversampled for individuals high in dental anxiety to have geographic diversity and a large range of participants with dental anxiety, this study relied on a self-selected sample of individuals whose responses may not represent a random national sample. Compared to the larger Testing sample, individuals who returned to complete the survey as part of the Test-Retest sample had lower mean MDAS scores, were less likely to be categorized to have high dental anxiety, were more likely to have had a dental appointment in the previous 12 months, and were less likely to have sought emergency care at their most recent dental appointment. These differences between the Testing and Test-Retest groups limit the generalizability of the results and call for more extensive validation of the MoDAIB. The Craigslist advertisements appeared in the sites based in large U.S. cities, which may not have reached as many individuals in more rural areas. Due to an unfortunate and unintentional omission during data collection, we did not collect data on race or ethnicity from our participants, so we are not able to determine how representative our sample is from that perspective. As there were fewer interpretational differences between dentally anxious and less anxious participants for Interpersonal and Worry scenarios than for other factors, it may be beneficial to develop different scenarios for these two factors that better discriminate between dentally anxious and less anxious individuals.

Future Directions

Our results clearly show that individuals in our study with high dental anxiety reported more negative interpretations of ambiguous dental situations than those with low or no dental anxiety. Additional validation work should be done with the MoDAIB with more diverse general and clinical samples. Going forward, the MoDAIB may be used as part of a larger intervention designed to modify the interpretations of individuals with high dental anxiety. CBM has been shown to reduce anxiety, at least in part by modifying individuals' negative interpretations of situations (34–36). If highly anxious individuals are able to change their negative interpretations of ambiguous dental situations, their overall dental anxiety may be reduced, and communication with the dental team may be improved.

Conclusions

Individuals who have high levels of dental anxiety are more likely to interpret ambiguous dental scenarios in a negative way compared to individuals with lower levels of dental anxiety. Prior therapeutic interventions for dental anxiety do not typically emphasize how individuals interpret commonly experienced dental situations, and evidence for this dental interpretational bias suggests potentially fruitful and exciting new avenues for therapeutic interventions for dental anxiety.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. Written proof of informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

LJH contributed to the conception and design of the study, performed data collection and interpretation, drafted, and revised the manuscript. BGL and DSR contributed to the conception and design of the study, data interpretation, critical review, and revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Dr. Douglass L. Morell Dentistry Research Fund at the University of Washington School of Dentistry.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere appreciation to all the individuals who participated in the surveys described in this article. Without their most valuable time and thoughtful responses, this paper would not have been possible. We would also like to thank the members of the Research Advisory Committee at the University of Washington School of Dentistry, who reviewed and approved the funding of these projects.

References

1. Milgrom P, Fiset L, Melnick S, Weinstein P. The prevalence and practice management consequences of dental fear in a major US city. J Am Dent Assoc. (1988) 116:641–7. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1988.0030

2. McNeil DW, Randall C.L. Dental fear and anxiety associated with oral health care: conceptual and clinical issues. In: Mostofsky DI, Fortune F, editors. Behavioral Dentistry. 2nd ed. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (2014). p. 165–92.

3. Armfield JM, Stewart JF, Spencer AJ. The vicious cycle of dental fear: exploring the interplay between oral health, service utilization and dental fear. BMC Oral Health. (2007) 7:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-7-1

4. Armfield JM. What goes around comes around: revisiting the hypothesized vicious cycle of dental fear and avoidance. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. (2013) 41:279–87. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12005

5. De Jongh A, van Eeden A, van Houtem C, van Wijk AJ. Do traumatic events have more impact on the development of dental anxiety than negative, non-traumatic events? Eur J Oral Sci. (2017) 125:202–7. doi: 10.1111/eos.12348

6. de Jongh A, Aartman IH, Brand N. Trauma-related phenomena in anxious dental patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. (2003) 31:52–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2003.00025.x

7. Eysenck MW, Mogg K, May J, Richards A, Mathews A. Bias in interpretation of ambiguous sentences related to threat in anxiety. J Abnorm Psychol. (1991) 100:144–50. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.2.144

8. Constans JI, Penn DL, Ihen GH, Hope DA. Interpretive biases for ambiguous stimuli in social anxiety. Behav Res Ther. (1999) 37:643–51. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00180-6

9. MacLeod C, Cohen IL. Anxiety and the interpretation of ambiguity: a text comprehension study. J Abnorm Psychol. (1993) 102:238–47. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.102.2.238

10. Vancleef LM, Hanssen MM, Peters ML. Are individual levels of pain anxiety related to negative interpretation bias? An examination using an ambiguous word priming task. Eur J Pain. (2016) 20:833–44. doi: 10.1002/ejp.809

11. Steinman SA, Teachman BA. Cognitive processing and acrophobia: validating the Heights Interpretation Questionnaire. J Anxiety Disord. (2011) 25:896–902. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.05.001

12. Cohen SM, Fiske J, Newton JT. The impact of dental anxiety on daily living. Br Dent J. (2000) 189:385–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800777a

13. Dental Fear Central,. Embarrassed? What Dentists Really Think: @dfcentral. (2021). Available online at: https://www.dentalfearcentral.org/fears/embarrassment/ (accessed July 5, 2021).

14. Mathews A, Ridgeway V, Cook E, Yiend J. Inducing a benign interpretational bias reduces trait anxiety. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. (2007) 38:225–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2006.10.011

15. Salemink E, van den Hout M, Kindt M. Trained interpretive bias: validity and effects on anxiety. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. (2007) 38:212–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2006.10.010

16. Milgrom P, Weinstein P, Heaton LJ. Treating Fearful Dental Patients: A Patient Management Handbook. Seattle, WA: Dental Behavioral Resources (2009).

17. Moore R, Brødsgaard I, Birn H. Manifestations, acquisition and diagnostic categories of dental fear in a self-referred population. Behav Res Ther. (1991) 29:51–60. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(09)80007-7

18. Locker D, Liddell A, Shapiro D. Diagnostic categories of dental anxiety: a population-based study. Behav Res Ther. (1999) 37:25–37. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00105-3

19. Humphris GM, Morrison T, Lindsay SJ. The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: validation and United Kingdom norms. Community Dent Health. (1995) 12:143–50.

20. Humphris GM, Freeman R, Campbell J, Tuutti H, D'Souza V. Further evidence for the reliability and validity of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale. Int Dent J. (2000) 50:367–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2000.tb00570.x

21. de Jongh A, Muris P, Schoenmakers N, ter Horst G. Negative cognitions of dental phobics: reliability and validity of the dental cognitions questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. (1995) 33:507–15. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00081-T

22. Gatchel RJ, Ingersoll BD, Bowman L, Robertson MC, Walker C. The prevalence of dental fear and avoidance: a recent survey study. J Am Dent Assoc. (1983) 107:609–10. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1983.0285

23. Oosterink FM, de Jongh A, Hoogstraten J, Aartman IH. The Level of Exposure-Dental Experiences Questionnaire (LOE-DEQ): a measure of severity of exposure to distressing dental events. Eur J Oral Sci. (2008) 116:353–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2008.00542.x

24. Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, Cella D. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. (2011) 18:263–83. doi: 10.1177/1073191111411667

25. Skaret E, Berg E, Raadal M, Kvale G. Reliability and validity of the dental satisfaction questionnaire in a population of 23-year-olds in Norway. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. (2004) 32:25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00118.x

26. van Wijk AJ, McNeil DW, Ho CJ, Buchanan H, Hoogstraten J. A short English version of the Fear of Dental Pain questionnaire. Eur J Oral Sci. (2006) 114:204–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00350.x

27. Armfield JM. Towards a better understanding of dental anxiety and fear: cognitions vs. experiences. Eur J Oral Sci. (2010) 118:259–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00740.x

28. Armfield JM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Index of Dental Anxiety and Fear (IDAF-4C+). Psychol Assess. (2010) 22:279–87. doi: 10.1037/a0018678

29. Nermo H, Willumsen T, Johnsen JK. Prevalence of dental anxiety and associations with oral health, psychological distress, avoidance and anticipated pain in adolescence: a cross-sectional study based on the Tromsø study, Fit Futures. Acta Odontol Scand. (2019) 77:126–34. doi: 10.1080/00016357.2018.1513558

30. van Wijk AJ, Hoogstraten J. Experience with dental pain and fear of dental pain. J Dent Res. (2005) 84:947–50. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401014

31. Lin CS, Lee CY, Chen LL, Wu LT, Yang SF, Wang TF. Magnification of fear and intention of avoidance in non-experienced versus experienced dental treatment in adults. BMC Oral Health. (2021) 21:328. doi: 10.1186/s12903-021-01682-1

32. Lima DSM, Barreto KA, Rank R, Vilela JER, Corrêa M, Colares V. Does previous dental care experience make the child less anxious? An evaluation of anxiety and fear of pain. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. (2021) 22:139–43. doi: 10.1007/s40368-020-00527-9

33. Getka EJ, Glass CR. Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches to the reduction of dental anxiety. Behav Ther. (1992) 23:433–48. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80168-6

34. Mathews A, Mackintosh B. Induced emotional interpretation bias and anxiety. J Abnorm Psychol. (2000) 109:602–15. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.4.602

35. Liu H, Li X, Han B, Liu X. Effects of cognitive bias modification on social anxiety: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0175107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175107

Keywords: dental anxiety, dental fear, interpretational bias, cognitive behavioral therapy, reliability – reproducibility of results, validity

Citation: Heaton LJ, Leroux BG and Ramsay DS (2022) Development and Testing of an Interpretational Bias Measure of Dental Anxiety. Front. Dent. Med. 3:871039. doi: 10.3389/fdmed.2022.871039

Received: 07 February 2022; Accepted: 20 April 2022;

Published: 17 June 2022.

Edited by:

Melissa Pielech, Brown University, United StatesReviewed by:

Tim Newton, King's College London, United KingdomArlette Setiawan, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia

Daniel Wilson McNeil, West Virginia University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Heaton, Leroux and Ramsay. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lisa J. Heaton, bGlzYWluc2VhdHRsZTQyQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; TEhlYXRvbkBjYXJlcXVlc3Qub3Jn

Lisa J. Heaton

Lisa J. Heaton Brian G. Leroux2

Brian G. Leroux2