94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

POLICY AND PRACTICE REVIEWS article

Front. Dent. Med., 21 September 2021

Sec. Systems Integration

Volume 2 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fdmed.2021.723021

This article is part of the Research TopicIntegrating Oral and Systemic Health: Innovations in Transdisciplinary Science, Health Care and PolicyView all 19 articles

Science and technology advances have led to remarkable progress in understanding, managing, and preventing disease and promoting human health. This phenomenon has created new challenges for health literacy and the integration of oral and general health. We adapted the 2004 Institute of Medicine health literacy framework to highlight the intimate connection between oral health literacy and the successful integration of oral and general health. In doing so we acknowledge the roles of culture and society, educational systems and health systems as overlapping intervention points for effecting change. We believe personal and organizational health literacy not only have the power to meet the challenges of an ever- evolving society and environment, but are essential to achieving oral and general health integration. The new “Oral Health Literacy and Health Integration Framework” recognizes the complexity of efforts needed to achieve an equitable health system that includes oral health, while acknowledging that the partnership of health literacy with integration is critical. The Framework was designed to stimulate systems-thinking and systems-oriented approaches. Its interconnected structure is intended to inspire discussion, drive policy and practice actions and guide research and intervention development.

As a field of study, health literacy, including oral health literacy, grew out of the recognition that the very advances in science and technology that have led to remarkable progress in understanding human health and disease are often lost on the public. Consumers who read health information and patients who leave doctor visits often fail to understand what has been said and what they should do in response. Some of this failure is a result of poor communication by the provider. As the National Academies' Institute of Medicine report noted in 2004, “Nearly half of all American adults—90 million people—have difficulty understanding and acting upon health information” (1). This report highlighted one of the first definitions of health literacy: The degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (2). Oral health literacy underscores the need to understand basic oral health information in order to make appropriate health decisions, many of which may have overall health implications (3).

In parallel with health literacy has grown a movement to integrate oral and general health in research, education, and clinical care. Their separation, the product of history and tradition, has led many to believe that oral health is less important and outside the realm of general health. But science has long proven otherwise (4–7). Reams of data demonstrate that what happens in the mouth affects, and is affected by, what happens elsewhere in the body. The association between periodontal disease and diabetes was recognized decades ago and the evidence linking oral disease with increased risk for certain cancers, and heart and lung disease is strong (8, 9). Former U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop summed it well saying, “You are not healthy without good oral health” (10).

In this paper we explore the relationship between oral health literacy and oral/general health integration showing that the two are inextricably linked. Achieving oral health literacy enhances the prospects of successful integration and in combination contributes to improved health outcomes, improved quality of care, and cost reductions (3). Together, they work toward reducing health disparities, especially glaring in the health of poor and minority groups, and thus achieving greater health equity. As stated in the Healthy People 2030 overarching goal; Achieving health and well-being requires eliminating health disparities, achieving health equity, and attaining health literacy (11).

Our analysis examines factors common to health literacy and integration that, for better or worse, influence them and suggests ways to overcome barriers and move forward. Specifically, we propose that investments in health literacy can open new avenues for advancing progress in developing a stronger health delivery system, improved public health, and enhanced health equity.

The first decades of the century marked substantive health literacy research and a succession of meetings and publications on health literacy, and oral health literacy in particular. These efforts revealed health literacy associated health outcomes due to personal, provider and health systems factors (1, 12). National action plans and toolkits offered guidance on the interface between health literacy and health outcomes (13, 14). Meanwhile, advocates decried the negative impact on the health of the public and ever-rising costs, due to the lack of understanding of the causes and ways to prevent disease, conflicting and complex health information messages, and poor communication between providers and patients. Then came the year 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare the extent of health care inequities in America the limitations in public health infrastructure, and the poor design of our health care delivery systems. An avalanche of information from multiple media platforms created massive confusion from conflicting messages from senior leaders and agencies, conspiracy theories, misinformation, and the lack of a unified national approach (15, 16). In addition, we experienced blatant structural racism, social injustice, and civic unrest. These events continue to cause stress, anxiety, and confusion among the population as a whole and within the health care environment. Specific to oral health, this experience has revealed major oral health inequities, challenged dental care services and the dental care workforce, and revealed the fragmentation in our health care and education systems (17–19). The provision of clear communication to individuals, families, providers, organizations, and jurisdictions was challenged, underscoring the urgency to take action to address the issues. It is clear that improving the health of the U.S. population, which is critical to economic stability and advancement, requires a combination of health practices and policies that emphasize the importance of good health, including oral health, for the entire population.

The groundwork for how next to proceed as society weathers the pandemic storm has been laid out in the earlier events of the decades, mostly under the auspices of the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine's Roundtable on Health Literacy and the Department of Health and Human Services (14, 20). These references include the federal government publications of health priorities and recommendations for each decade, currently Healthy People 2030 (21, 22).

A significant outcome of health literacy research and these national assessments led to changes in the definition of health literacy. The revisions broaden the scope and responsibilities from a focus solely on individuals to a systems approach. Healthy People 2030 includes new definitions (Box 1) for personal (individual) and organizational health literacy, providing more specificity than the earlier definitions (23).

Box 1. New Health Literacy Definitions: Healthy People 2030.

Personal health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the ability, to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.

Organizational health literacy is the degree to which organizations equitably enable individuals to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.

The combination of personal (individual) and organizational health literacy definitions reinforces the need for integration of all health promotion, health care information, and services (both oral and general health). Both definitions highlight the importance of acting on the information to inform health-related decisions and actions, not only for themselves, but also for others. Relevant to integration, the reference to individuals encompasses more than the lay public (individuals, families, communities) and includes health care providers, policy makers, administrators of health and health care programs, and those responsible for developing and disseminating health information. The organizational definition further recognizes the role entities that create health information and those that provide health services play in contributing to health literacy and the importance of their doing so “equitably.” This definition also acknowledges that health literacy is dependent on the context (where, when, how, and by and to whom) and serves as the basis for the discussion in this paper. The new health literacy definitions broaden the imperative for action.

Oral health-related highlights of the pre-pandemic years include activities of the NASEM Roundtable on Health Literacy (Roundtable), which reviewed oral health literacy (25). The 2013 workshop investigated the importance of community support for health literacy, particularly in relation to:

• the health problems of vulnerable populations,

• the role of dental providers in communicating with a diverse patient population, and

• the role of health delivery systems in advancing an understanding of the patient's needs in order to obtain necessary care.

The Roundtable commissioned an environmental scan to assess ways in which health literacy promotes integration of oral health in primary care (26). During a 2018 workshop (27), discussion addressed changes needed in the health system, pointing to:

• the lack of interprofessional collaboration,

• payment systems that minimize prevention, and

• the need for consumer involvement.

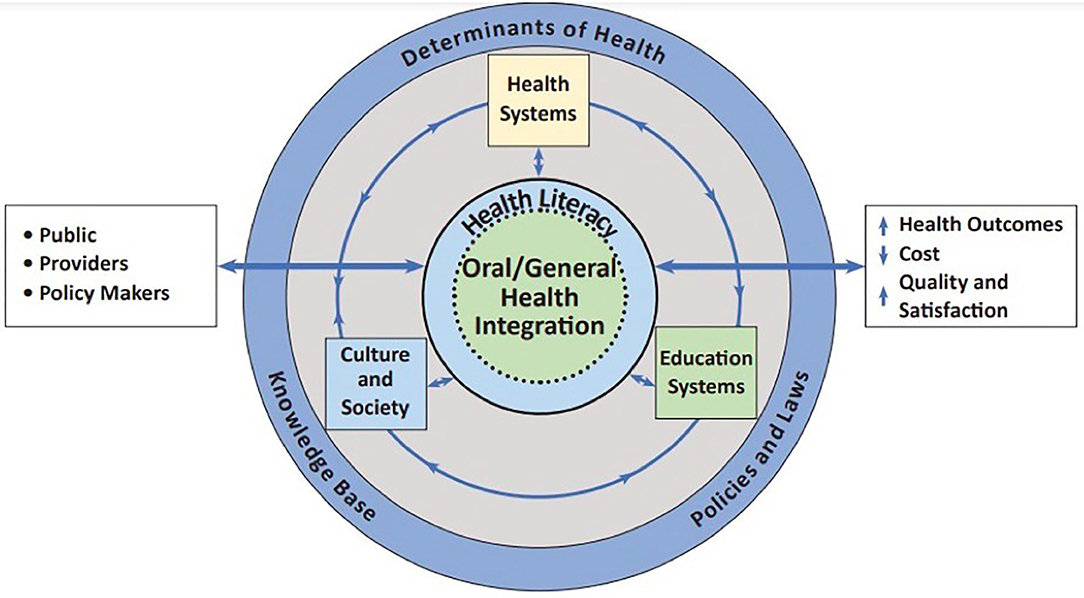

To discuss the catalytic role of health literacy and health integration, we have selected the health literacy framework presented in the 2004 IOM Report (1) as the foundation. The IOM developed the framework as the organizational principle of the report. It provides a useful visual of “the potential influence on health literacy as individuals interact with educational systems, health systems and cultural, and social factors” at home, work and in the community. It also illustrates that these factors may ultimately contribute to health outcomes and costs. Health literacy sits within a network of systems, culture, and society, each with its own attributes and related legal, social, and ethical issues, which the IOM report refers to as “intervention points.” Importantly the IOM report recognized that health systems play a significant role, but that improvements in health literacy must be shared by all sectors.

Our Oral Health Literacy and Health Integration Framework, is designed to recognize the complex factors that contribute to both integration and health literacy and ultimately to health equity (Figure 1). The Framework is based on the premise that effective integration of oral and general health is critical, and is enhanced by health literacy. This situation requires a clear understanding of health conditions and needs, care services, community needs and the roles played by individuals, health care providers, and health policy makers.

Figure 1. Oral health literacy and health integration framework. Adapted and reproduced with permission from the National Academy of Sciences, Courtesy of the National Academies Press, Washington, DC (24).

Health literacy and oral/medical integration are partnered and centrally placed with a permeable membrane between them, emphasizing the interplay. Health literacy is a determinant of health. Limited health literacy by individuals and systems is associated with poor health outcomes, health disparities, reductions in health care quality and increased costs (1, 28, 29). Equally important, limited health literacy and lack of integration are impediments to achieving health equity. As a determinant of health, health literacy plays a critical role in facilitating:

• the ability of individuals to care for themselves and their families,

• shared decision-making between individuals and their health care providers,

• the ability of providers to communicate in a manner that all patients understand,

• actions that contribute to overall health and well-being,

• health care quality at the community and health care system level, and

• the development and implementation of effective health policies.

Through these roles, health literacy provides an essential foundation for the integration of comprehensive health and health care services, including the integration of oral and medical health care. In contrast, the limited or lack of integration of oral and medical care may contribute to continued poor health literacy within individuals and groups, ultimately resulting in poor population health.

The Framework is nested in a broader environment, including a rapidly evolving knowledge base, emerging health policies and multiple determinants of health. The knowledge base, nurtured by the research community, informs our understanding of health, well-being, and the diseases and conditions that affect the ability of individuals and populations to thrive. Integration is essential in our design and funding of research, from basic through implementation research (30). The knowledge base also informs the development of evidence-based interventions and programs and policies by health systems that support patient health and well-being and prevent harm to the public.

The determinants of health are conditions that affect an individual's or community's ability to thrive. As a determinant of health, health literacy contributes to how individuals manage the conditions of living: their housing, work and social environments, and their engagement in their communities and society at large. These are “non-health care system” determinants and play a major role in lowering or increasing the risk of disease, self-care, and access to health information and care services. Oral health literacy, including the promotion of oral health and access to oral health care contributes positively to the social determinants of health, enabling individuals to meet their basic food and hygiene needs, to be employed, and participate as social beings.

The Framework highlights the role of the public, health care providers, and policy-makers in improving population health and addressing health care inequities. These, and other critical players, such as researchers, educators, and administrators, contribute as individuals in their personal and professional roles and as members of organizations in each of the systems. Intermediate outcomes include improving overall health and well-being, reducing costs, enhancing quality of care, and consumer and provider satisfaction. These outcomes provide feedback into the various systems through the lens of health literacy and oral/general health integration.

Inherent to this Framework are basic questions as to whether the respective health systems, culture, community and society, or the education systems enable or limit integration, and how can health literacy skills and principles contribute to and support integration.

Integration and care coordination of oral and general health are dependent upon a complex system of factors (26, 31). For health care, it requires having sufficient knowledge, enabling technologies, and supportive reimbursement mechanisms. The capacity and willingness to integrate and ensure quality of care reflect the level of commitment and agreement among individuals, clinical teams, organizations, and systems. While physical proximity has its benefits, the separation of dental and medical offices, geographically or within the same office building, need not be a deterrent if providers have established a communication system and means for making patient referrals. Even the co-location of providers, such as in a Federally Qualified Health Center housing both dental and medical offices, which allows for personal interactions, would better meet the needs of integrated care with technological enhancements such as interoperable electronic health records. Yet, the foundation for building and sustaining successful integration and care coordination requires a more extensive reach, one that can be enhanced with health literacy.

The interaction of health literacy and integration occurs within and among the larger contexts of culture and society, educational institutions, and health care systems—each of which may, or may not— support integration or promote health literacy.

Cultural and societal factors, including communities and neighborhoods, play a large role in determining how individuals identify themselves, the language they speak, the customs or behaviors they follow and their core moral beliefs on what constitutes proper attitudes and behaviors. But they are not static. They are subject to the changes wrought by historical events, developments in art, science and technology, environmental disasters and influences of the media and powerful leaders. The 2004 IOM report recognized the impact of culture and societal factors on individuals, highlighting the importance of ensuring health providers' language and cultural competency in communicating with patients (1). But even in 2004 the report recognized there were multiple challenges to health care information coming from competing sources. These have only grown in the intervening years and with the pandemic have worsened with the addition of misinformation and disinformation, further alarming the public, care providers and policy makers alike.

Achieving health literacy in society today will depend on gaining the trust of a disaffected public and establishing sources of information aligned with the best scientific evidence available. Venues for such resources include libraries, Extension programs, faith and social service groups, and city and county councils.

The perception of dentistry as an outsider contributes to how the public views health providers and services. This perception also affects health care professionals in their development and chosen role. Each specialty has its own traditional culture, norms, language, and how it sees itself (and as other health professionals see it) in relation to the health care system as a whole. This is reflected in where and how professionals practice, how they are reimbursed, and how they interact with other health professionals as well as with the public. For oral health/dental services, these characteristics place oral health care physically and in the minds of the public and policy makers, “outside” the medical care system. This is in addition to legal restrictions imposed by state practice acts that set formal limits on the scope of practice and in this way discourage integration of services among different health care providers. These cultural, societal, and legal factors and perceptions challenge the concept of integration of oral health into overall health and health literacy. On the positive side in support of oral/medical integration, are changes in practice acts and reimbursement for care that are paving the way for new workforce categories (advance practice dental hygienists, dental therapists, community dental health coordinators, and community health workers), and expanded access to oral and medical services. Examples include dental hygienists who practice in medical settings, physician and nurse practitioners who provide fluoride varnish, and dentists who provide vaccines for COVID-19 and triage other conditions. To benefit from these changes and accelerate their implementation, clear communication is needed to describe these changes, why they are important and their impact on health to the public. In turn this can inform the actions of policy makers and health care providers.

Educational systems include primary, secondary, and higher education, including health professions education, and non-formal education that is incorporated into programs like Head Start, adult literacy programs and continuing education programs. The link between a student's health and academic outcomes, such as letter grades or test scores is well-established (32). Results from the 2015 national Youth Risk Behavior Survey showed that high school students who earned mostly A's, B's, or C's reported greater use of protective health-related behaviors and significantly lower use of risky behaviors than classmates with D's/F's. National Health Education Standards, currently provide eight comprehensive standards for PreK-12 grades (33). Yet despite national standards, the quality, quantity, and content of health education taught in schools is ultimately decided by state and local entities. The result is that the amount students learn about health in school varies dramatically, and frequently is given short shrift. Further, oral health is often omitted entirely because other health issues such as obesity or sexuality are deemed critical, ignoring the fact that oral health issues play a role in each of those areas (dental caries and sugary diet in obesity and HPV infection in sexuality).

In many ways providing appropriate oral health education for children through their school years is an optimal pathway for achieving oral health literacy. Teaching children about dental caries or teenagers about HPV infections may also increase their parent's oral health literacy. Adult literacy classes may also serve as sources for increasing oral health literacy, focusing on critical topics such as diet, drug use, and association with chronic diseases. Because many adult learners are either foreign born or from disadvantaged homes, they may have a great need for dental treatment and may lack understanding of the U.S. oral health care system, both of which could be covered in the class.

There are similar missed opportunities in health professions education, although progress is being made. In the past decade, more attention has been focused on oral/medical integration and related teaching, spurred by the general movement toward patient-centered care and interprofessional education and practice (34–36). These efforts have resulted in the creation of curricular modules, testing of new education strategies (37–39) and technical assistance toolkits (40, 41). Interprofessional communication is one of the four Interprofessional Education Collaborative (42) competencies, providing a place where health literacy principles and skills can easily be aligned and contribute to enhanced collaboration among health professionals. Health literacy includes communication, but also encompasses the health care delivery environment. This extends beyond the critical patient-provider interaction, and includes factors that guide access to care, care interactions and compliance with treatment, such as clinical information systems and decision support technologies (43). Health professions schools, as institutions, would be ideal sites to incorporate organizational health literacy. Adoption of the attributes of health literate health care organizations could create supportive environments and model how health literacy attributes enhance institutions that provide health care services (20). This exposure during health providers' formative training has the potential for lasting effects upon their graduation.

Health systems include both public and private health care organizations and programs, third-party payers, health care administrators, employed, or independent private practitioners, plus all the licensing, certification, and accreditation entities as well as medical/dental trade associations. Health systems reflect the “culture of care” and are strongly and inextricably tied to our education systems. The health professions workforce continues to evolve, diversify, and extend into traditional health settings and the emerging knowledge base requires ongoing training and development.

Moving from formal educational settings into health care practice adds new challenges for graduates who may or may not be prepared and oriented to oral/medical integration. While medical and dental schools share similar course work in the first year or two of professional school, few medical schools cover oral tissues and diseases in their curricula or medical residencies. The IPEC competences added skills to non-dental providers to enable interprofessional practice, but there has been little adoption and follow up by physicians, outside of fluoride varnish (44). This means physicians are less likely to refer pregnant patients or diabetic patients for dental care and less likely to urge consumption of tap water to access publicly funded community fluoride programs. Similarly, dentists are less likely to refer their patients for medical care for high blood pressure, diabetes, and HPV vaccines. While all states now reimburse physicians and their staff for oral health counseling and the application of fluoride varnish, there is much more to learn about how the two professions can achieve seamless management of children under the age of 5 (45).

All health care providers contribute to both personal and organizational health literacy, and wherever they practice, their positions place them as front-line communicators and educators to the patients and publics they serve. Provider personal health literacy requires them to be fully capable of finding, understanding, and using information and services to inform health-related decisions, and to communicate the information to their patients, families, and collaborating health providers. Challenges include exponential growth of science findings, evolving changes in evidence-based protocols, the introduction of shared services among providers, and the emerging expansion of the scope of practice. These factors, together with policy changes that reinforce specific new knowledge and practices, such as re-licensure requirements and central monitoring systems, reinforce the importance of personal heath literacy for health providers.

Whether providers are in private practice or employed by health care organizations, they also play a critical role in addressing “organizational health literacy.” For providers in hospital systems and health care settings, the relevant oversight accrediting and regulatory agencies provide incentives, such as alignment with The Joint Commission on Accreditation Standards for provider communication and health literacy (46). Dental school accreditation criteria include health literacy as one of the behavioral sciences curriculum elements. It states that “Graduates must be competent in managing a diverse patient population and have the interpersonal and communications skills to function successfully in a multicultural work environment” (47). Dental providers who work in academic institutions need to fulfill both the CODA requirements, and, if interfacing with the medical center, also that of the Joint Commission.

Professional organizations play an important role in providing clinical practice guidelines, techniques to simplify in-office communications, continuing education courses, ethical expectations, and new workforce models for their respective providers and the community. These organizations can also contribute by providing resources on Accreditation, and tools to support health care organizations in addressing provider-patient communication standards in health care settings (46, 48).

The many challenges to oral/medical integration include separate location of practice sites; lack of interoperable patient record systems, separate practice quality review systems, and a lack of common insurance coverage (49). These factors limit coordination and integration of care among health care providers and result in fragmented care for patients. As well, they pose health literacy challenges for patient self-management. In 1999, two-thirds of dentists worked in solo practice; the number in 2019 was 50.3% (50) compared with 15% of physicians (51). The separation of dental practice from the more corporate organization of medical care confuses patients who are accustomed to medical providers who collaborate with their colleagues to manage patients' care, often via referrals within the same health care system and even at the same site. Referrals between dentists and physicians are less common, placing a burden on the patient to manage the communication flow and exchange of patient records between providers (52). A common electronic patient record would facilitate bi-directional communication between practitioners, reducing the patient's burden. It would also facilitate the management of chronic conditions, such as obesity, diabetes, and others associated with common risk factors such as diet, smoking, alcohol use, the environment, and access to health care (53). Currently, several initiatives and health systems such as Marshfield Clinic Health System, HealthPartners, Kaiser Permanente, Apple Tree Dental and others, are addressing these challenges (26, 54–56).

Connecting a private dental practice to a larger health system such as an accountable care organization could introduce provider communication quality measures, such as measuring the extent to which the doctor listens carefully to patients, and explains things in a way patients can understand (57). Training physicians on The Joint Council of Accreditation's “What did the doctor say? Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety” (58) offers a roadmap for how dental education curricula could incorporate health literacy principles to improve safety and quality in next generation dental practitioners. These organizational standards help hospitals, ambulatory care facilities, and behavioral health facilities achieve a higher quality of care and patient safety. The provision of educational materials to medical practices on the Universal Precautions Health Literacy Toolkit, and the importance of adopting the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) can facilitate patient understanding of care instructions (59).

The lack of a common insurance system to handle medical and dental coverage is a point of serious confusion for even the most health literate consumers. Preventive messages from physicians rarely include the association with dental diseases, such as caries, which continues to be the condition representing the highest global burden of disease (60). This missed opportunity increases the challenge for people with lower health literacy to learn about the connection between the mouth and body, and to recognize the need for daily prevention and regular dental visits. Recent studies have demonstrated that medical organizations can reduce overall health care costs (predominantly hospital costs) for people with chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes by covering the cost of periodontal cleanings (61, 62). This approach provides an opportunity for enhanced education.

The report of the Primary Care Collaborative for 2021 provides a timely snapshot of the current state of innovations in oral health and primary care integration. A call to action recommends expanding oral health coverage and access, aligning oral health and primary care with new payment models, and enhancing the health workforce (31). Each of the integration challenges and their solutions have clear health literacy implications. Implementing the proposed “health literate care model” as described by Koh et al. could provide additional support and reinforce oral/medical integration practices (43). This approach could foster the anticipated health care transformation toward a greater prevention orientation, population health focus, and primary and social care-based systems (63).

The long-recognized need for oral and general health care integration has grown. Achieving such integration is complex and difficult, requiring a long-term commitment and coordinated efforts. Work to achieve integration has resulted in progress in some areas but remains challenging in others, necessitating a call for new and different approaches. A coordinated, sustained, multilevel approach that includes health literacy is needed. Along with investments in science assessments of policies and laws and their impact on the determinants of health are needed as well as implementation of quality improvement methods for clinical and public health services and systems.

The Oral Health Literacy and Health Integration Framework provides an interconnected structure to inspire discussion, drive policy and practice actions, and guide future research and intervention. We adapted the 2004 IOM health literacy framework (1), adding oral and general health integration, with an accompanying rationale for partnering health literacy and integration. The power of both personal and organizational health literacy efforts provides a strong foundation for an ever-changing and evolving society and environment. We propose that using the lens of the public we serve, health care providers we support, and policy-makers we inform adds an important dimension to foster systems thinking.

The Framework was developed to acknowledge the complexity of efforts needed to achieve an equitable health system that includes oral health, highlights the critical partnering role of health literacy, and stimulates systems thinking and systems-oriented approaches. Stroh's description of when the value of systems thinking is most effective suits the current stage and problems of integrating oral and general health. As Stroh [(64) p. 23–24] wrote, incorporating systems thinking into a broader systems approach is especially effective when:

• “A problem is chronic and has defied people's best intentions to solve it.

• Diverse stakeholders find it difficult to align their efforts despite shared intentions.

• They (diverse stakeholders) try to optimize their part of the system without understanding their impact on the whole.

• Stakeholders' short-term efforts might actually undermine the intent to solve the problem.

• People are working on a large number of disparate initiatives at the same time.

• Promoting particular solutions (such as best practices) comes at the expense of engaging in continuous learning.”

An essential part of the systems thinking process involves taking the time to explore the direct and indirect contributing factors and to identify intended and unintended consequences. It also requires a continuous quality improvement and engagement approach.

Next steps involve testing the use of the Oral Health Literacy and Health Integration Framework as a tool to help with our collective work and impact. An initial phase may include mapping existing oral and general health integration efforts and noting the degree to which they include health literacy. The activity clusters could be used to identify advances, reveal knowledge gaps and inform collaborative efforts. Ultimately, we should strive for a common agenda with mutually reinforcing activities, shared measurement, and continuous communication.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

This work was supported by Santa Fe Group C/O Aegis Communications 140 Terry Dr. Suite 103, Newton, PA 18940.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We acknowledge the substantial editing contribution of Joan Wilentz.

1. IOM, Kindig DA, Panzer AM, Nielsen LB. (editors) (2004). Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

2. Ratzan SC, Parker RM. Introduction. In: Selden CR, Zorn M, Ratzan SC, Parker RM, editors. National Library of Medicine Current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2000).

3. Horowitz AM, Kleinman DV, Atchison KA, Weintraub JA, Rozier RG. The evolving role of health literacy in improving oral health. Stud Health Technol. Inform. (2020) 25:95–114. doi: 10.3233/SHTI200025

4. USDHHS. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon. General Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health (2000). Available online at: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2017-10/hck1ocv.%40 (accessed May 19, 2021).

5. USDHHS. National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. NIH Publication No. 03-5303 (2003).

7. Institute of Medicine and NRC National Research Council. Improving Access to Oral Health Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press (2011).

8. Beck JD, Papapanou PN, Philips KH, Offenbacher S. Periodontal medicine: 100 years of progress. J Dent Res. (2019) 98:1053–62. doi: 10.1177/0022034519846113

9. Baeza M, Morales A, Cisterna C, Cavalla F, Jara G, Isamitt Y, et al. Effect of periodontal treatment in patients with periodontitis and diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Appl Oral Sci. (2020) 28:e20190248. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757-2019-0248

11. USDHHS. USDHHS Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP). Healthy People 2030 Framework. (2021). Available online at: https://health.gov/healthypeople/about/healthy-people-2030-framework (accessed May 8, 2021).

12. Koh HK, Berwick DM, Clancy CM, Baur. C., Brach C, Harris LM, et al. New federal policy initiatives to boost health literacy can help the nation move beyond the cycle of costly ‘crisis care.’ Health Aff. (2012) 31:434–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1169

13. USDHHS. AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit, Second Edition. AHRQ Publication No. 15-0023-ERockville F, MD. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2015). Available online at: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/healthlittoolkit2_3.pdf (accessed May 8, 2021).

14. USDHHS ODPHP. National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. Washington, DC (2010). Available online at: https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Health_Literacy_Action_Plan.pdf (accessed May 8, 2021).

15. World Health Organization (WHO) (2020). Risk Communication and Community Engagement Readiness and Response to Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). (2020). Available online at file:///C:/WHO-2019-nCoV-RCCE-2020.2-eng.pdf (accessed on May 13, 2021).

16. Airhihenbuwa CO, Iwelunmor J, Manodowafa D, Ford CL, Oni T, Agyemang C, et al. Culture matters in communicating the global response to COVID-19. Prev Chronic Dis. (2020) 17:200–45. doi: 10.5888/pcd17.200245

17. Zachary B, Weintraub JA. Oral health and COVID-19: increasing the need for prevention and access. Prev Chronic Dis. (2020) 17:E82. doi: 10.5888/pcd17.200266

18. The Gerontological Society of America Webinar (2021). The Gerontological Society of America (GSA) Webinar Pandemic Driven Disruptions in Oral Health. (2021). Available online at: geron_org/images/gsa/documents/Pandemic_Driven_Disruptions_in_Oral_Health.pdf (accessed May 12, 2021).

19. Weintraub JA, Quinonez RB, Smith AJ, Kraszeski MM, Rankin MS, Matthews NS. Responding to a pandemic. JADA. (2020) 151:P825–34. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2000.08

20. Brach C, Keller D, Hernandez LM, Bauer C, Parker R, Dreyer B, et al. Ten Attributes of Health Literate Health Care Organizations. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; Discussion Paper (2012). Available online at: https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/BPH_Ten_HLit_Attributes.pdf (accessed May 8, 2021).

21. USDHHS ODPHP. Health Literacy in Healthy People. Health.gov. (2030). Available online at: https://health.gov/our-work/healthy-people/healthy-people-2030/health-literacy-healthy-people-2030 (accessed May 8, 2021).

22. USDHHS Oral Health Strategic Framework (2014–2017) Oral Health Coordinating Committee (2014). HHS Oral Health Strategic Framework 2014–2017. Available online at: https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/oralhealth/oralhealthframework.pdf (accessed May 8, 2021).

23. Santana S, Brach C, Harris L, Ochiai E, Blakey C, Bevington F, et al. Updating health literacy for healthy people 2030: defining its importance for a new decade in public health. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2021). doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001324. [Epub ahead of print].

24. Institute of Medicine. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: Courtesy of the National Academies Press (2004).

25. IOM. Oral Health Literacy: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press (2013).

26. Atchison KA, Rozier RG, Weintraub JA. Integrating Oral Health, Primary Care, and Health Literacy: Considerations for Health Professional Practice, Education, and Policy. Commissioned by the Roundtable on Health Literacy, Health and Medicine Division, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, the Paper is found by clicking the button at this website (2017). Available online at: https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/integrating-dental-and-general-health-through-health-literacy-practices-a-workshop

27. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Integrating Oral and General Health Through Health Literacy Practices: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press (2019).

28. Institute of Medicine, Adams K, Corrigan JM. (editors). Priority Areas for National Action: Transforming Health Care Quality. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press (2003).

29. Vernon JA, Trujillo A, Rosenbaum S, DeBuono B. Low Health Literacy: Implications for National Health Policy. Washington, DC: Department of Health Policy, School of Public Health and Health Services, The George Washington University (2007). Available online at: https://publichealth.gwu.edu/departments/healthpolicy/CHPR/downloads/LowHealthLiteracyReport10_4_07.pdf (accessed May 10, 2021).

30. Somerman M, Mouradian WE. Integrating oral and systemic health: innovations in transdisciplinary science, health care and policy. Front Dent Med. (2020) 1:599214. doi: 10.3389/fdmed.2020.599214

31. Primary Care Collaborative. Innovations in Oral Health and Primary Care Integration: Alignment with the Shared Principles of Primary Care. (2021). Available online at: https://www.pcpcc.org/resource/OHPCintegrationreport (accessed May 8, 2021).

32. Rasberry CN, Tiu GF, Kann L, McManus T, Michael SL, Merlo CL, et al. Health-related behaviors and academic achievement among high school students-United States, 2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. (2017) 66:921–7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6635a1

33. Birch DA, Goekler S, Auld EM, Lohrmann DK, Lyde A. Quality assurance in teaching K−12 health education: paving a new path forward. Health Promot. Pract. (2019) 20:845–57. doi: 10.1177/1524839919868167

34. CIPCOH. Center for the Integration of Primary Care and Oral Health. Harvard School of Dental Medicine (2021). Available online at: https://cipcoh.hsdm.harvard.edu/ (accessed May 8, 2021).

35. NIIOH. National Interprofessional Initiative on Oral Health (NIIOH). (2021). Available online at: https://www.niioh.org/content/about-us (accessed on May 8, 2021).

36. Oral Health Nursing Education and Practice. Available online at: http://ohnep.org/ (accessed May 8, 2021).

37. Haber J, Hartnett E, Cipolina J, Allen K, Crowe R, Roitman J, et al. Attaining interprofessional competencies by connecting oral health to overall health. J Dent Educ. (2020) 85:504–12. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12490

38. Ferullo A, Silk H, Savageau JA. Teaching oral health in U.S. medical schools: results of a national survey. Acad Med. (2011) 86:226–30. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182045a51

39. STFM. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Group on Oral Health. (2005). Smiles for Life Oral Health. Available online at: http://www.smilesforlifeoralhealth.org/ (accessed May 8, 2021).

40. USDHHS, Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) HIV/AIDS Bureau 2019. Integration of Oral Health and Primary Care Technical Assistance Toolkit. (2019). Available online at: https://targethiv.org/sites/default/files/file-upload/resources/hab-oral-health-integration-toolkit_july%202019.pdf (accessed at May 8, 2021).

41. Qualis Health. Safety Net Medical Home Initiative. Implementation Guide Supplement. Organized, Evidence-based care: Oral health integration (2016). Available online at: https://www.qualishealth.org/sites/default/files/Guide-Oral-Health-Integration.pdf (accessed on: May 8, 2021).

42. Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: 2016 Update. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative (2016). Available online at: https://ipec.memberclicks.net/assets/2016-Update.pdf (accessed May 8, 2021).

43. Koh HK, Brach C, Harris LM, Parchman ML. A proposed “Health Literate Care Model” would constitute a systems approach to improving patients' engagement in care. Health Aff. (2013) 32:357–67. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1205

44. Sams LD, Rozier RG, Wilder RS, Quinonez RB. Adoption and implementation of policies to support preventive dentistry initiatives for physicians: a national survey of medicaid programs. AJPH. (2013) 103:e83–90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301138

45. Kranz AM, Rozier RG, Stein BD, Dick AW. Do oral health services in medical offices replace pediatric dental visits? J Dent Res. (2020) 99:891–7. doi: 10.1177/0022034520916161

46. Cordero T. The Joint Commission. Helping Organizations Address Health Literacy. (2018). Avaialble online at: https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/blogs/dateline-tjc/2018/11/helping-organizations-address-health-literacy/ (accessed 2, 2021).

47. Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation Standards for Dental Education Programs. (2019). Available at: https://www.ada.org/\sim/media/CODA/Files/predoc_standards.pdf?la=en (accessed May 8, 2021).

48. American Dental Association, Public Programs. Health Literacy. (2021). Available online at: https://www.ada.org/en/public-programs/health-literacy-in-dentistry (accessed May 24, 2021).

49. Norwood CW, Maxey HL, Randolph C, Gano L, Kochbar K. Administrative challenges to the integration of oral health with primary care. J Ambulatory Care Manage. (2017) 40:204–13. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000151

50. ADA News. Dentists' Practice Ownership Decreasing. Chicago, IL (2018). Available online at: https://ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2018-archive/april/dentists-practice-ownership-decreasing (accessed May 24, 2021).

51. Kane CK. Updated data on physician practice arrangements: for the first time, fewer physicians are owners than employees. American Medical Association (2018). Available online at: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-07/prp-fewer-owners-benchmark-survey-2018.pdf (accessed May 19, 2021).

52. Atchison KA, Rozier RG, Weintraub JA. Integration of Oral Health and Primary Care: Communication, Coordination, and Referral. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC (2018).

53. Sheiham A, Watt RG. The common risk factor approach: a rational basis for promoting oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. (2000) 28:399–406. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028006399.x

54. Atchison K, Weintraub J, Rozier R. Bridging the dental-medical divide: case studies integrating oral health care and primary health care. J Am Dental Assoc. (2018) 149:850–8. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2018.05.030

55. Helgeson M. Economic models for prevention: making a system work for patients. BMC Oral Health. (2015) 15(Suppl 1):S11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-15-S1-S11

56. MacNeil, RL, Hilario, H, Ryan, MM, Glurich I, Nycz GR, Acharya A, et al. The case for integrated oral and primary medical health care delivery: marshfield clinic health system. J Dent Educ. (2020) 84:924–31. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12289

57. Press Ganey Associates (2018). Available online at: https://helpandtraining.pressganey.com/documents/hcahps_communication_guidelines.pdf (accessed March 7, 2021).

58. The Joint Commission. “What Did the Doctor Say?” Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission (2007).

59. USDHHS Office of Minority Health. National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health and Health Care (n.d.). Available online at: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=1&lvlid=6 (accessed August 22, 2021).

60. Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Flaxman A, Naghavi M, Lopez A, et al. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. J Dent Res. (2013) 92:592–7. doi: 10.1177/0022034513490168

61. Nasseh K, Vujicic M, Glick M. The Relationship between periodontal interventions and healthcare costs and utilization. Evidence from an integrated dental, medical, and pharmacy commercial claims database. Health Econ. (2017) 26:519–27. doi: 10.1002/hec.3316

62. Jeffcoat MK, Jeffcoat RL, Gladowski PA, Bramson JB, Blum JJ, et al. Impact of periodontal therapy on general health: evidence from insurance data for five systemic conditions. Am J Prev Med. (2014) 47:166–74. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.001

63. Zimlichman E, Nicklin W, Aggarwal R, Bates DW. Health care 2030: The coming transformation. NEJM Catalyst Innovation in Care Delivery. Available online at: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0569 (accessed May 11, 2021).

Keywords: health literacy, organizational health literacy, oral health, oral health literacy, health systems integration, health care services

Citation: Kleinman DV, Horowitz AM and Atchison KA (2021) A Framework to Foster Oral Health Literacy and Oral/General Health Integration. Front. Dent. Med. 2:723021. doi: 10.3389/fdmed.2021.723021

Received: 09 June 2021; Accepted: 04 August 2021;

Published: 21 September 2021.

Edited by:

Francisco Nociti, State University of Campinas, BrazilReviewed by:

Prabhat Kumar Chaudhari, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, IndiaCopyright © 2021 Kleinman, Horowitz and Atchison. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dushanka V. Kleinman, ZHVzaGFua2FAdW1kLmVkdQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.