- Department of Energy Plant Research Laboratory, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

There has long been a focus on building inclusion and diversity in the sciences through a range of efforts intended to increase representation and access. Despite expansive efforts supported by higher education institutions, funding agencies and others, a need persists to support broad participation and success. Digital platforms, including blogs, and social media such as Twitter™, offer emergent paths for scientists to proactively build supportive communities, even where structural diversity or numerical representation of diverse groups remains low. Use of these platforms can range from community building, to proactive mentoring, and advocacy, as well as more customary uses for supporting scholarly success of diverse individuals, including dissemination and accessible discussions of research findings. I discuss specific uses of social-media digital platforms for building and cultivating communities of underrepresented scholars and facilitating engagement around issues of broad concern to groups underrepresented in science and higher education. These uses include mentoring and support to promote equity, inclusion and diversity, promoting self-definition and personal agency, community building, and advocacy. I draw on published literature about using social media and digital platforms in higher education to build and cultivate “social networks” for connecting widely distributed individuals from underrepresented backgrounds to cultivate communities of interest, support and practice, including a focus on mentoring, sponsorship, and advocacy. I highlight the power of Twitter™ and social media platforms to build and cultivate connections of individuals underrepresented in science and the academy and to offer meaningful means for mitigating local deficits related to low structural diversity and inequity.

Introduction

Digital social media platforms are currently widely integrated in multiple aspects of life from personal communications and connections to business branding and outreach. Despite the wide acceptance of digital platforms broadly, “higher education has been comparatively slow to adopt digital social networking into organizational practice” (Williams and Woodacre, 2016, p. 282). Where used, these platforms are frequently focused on direct scholarly or institutional benefits, including initiating or following research-related discussions related to one's field (Holmberg and Thelwall, 2014; Van Noorden, 2014; Collins et al., 2016; Côté and Darling, 2018), rather than on other potential uses such as for social justice-oriented outcomes, including community-related issues such as broadening participation and success of individuals from underrepresented groups in the academy. The power of “social networks” supported by digital platforms for connecting widely distributed individuals and providing connection, community, and establishing platforms for mentoring, sponsorship and advocacy has been increasingly recognized (Guerrero-Medina et al., 2013; Matthew, 2016b). Such emerging uses suggest significant potential for the utilization of these platforms for addressing some long-standing challenges in higher education, in particular, those related to community building and support for individuals underrepresented or who are often not fully integrated in these spaces. The ability of social media and digital platforms to facilitate connecting individuals in the academic sciences in functioning networks and to serve to counteract inequities and limits to access to critical capital and support are the focus for which I advocate.

Specific racial/ethnic and other minoritized groups continue to be vastly underrepresented in the academy relative to their proportions in the U.S. population. Even as the demographics of students at colleges and universities are changing, increasing underrepresentation occurs in the faculty ranks and even more so in the professional and administrative ranks (Whittaker et al., 2015; Montgomery, 2018). Individuals from groups underrepresented in the academy have reported experiencing hostility, disrespect, and marginalization in these spaces (Gonzales, 2018). There is evidence that some inequities, discrimination and hostility occur in digital platforms and social media spaces, just as in the academy and larger society (Museus and Truong, 2013; Tynes et al., 2013; Baldwin, 2017; Gin et al., 2017). However, I argue that engagement in social media offers some benefits that may outweigh potential costs. Social media and digital platforms offer low-cost, low-barrier engagement to increase connections and participation of individuals from underrepresented groups who are often in low numbers locally. Given the recognition that some underrepresented individuals report experiencing hostile or discriminatory treatment in local spaces (Gonzales, 2018), the connection in larger networks for support and advocacy in social media spaces may counteract some of the challenges and “costs” that are viewed as high for others who may not experience persistent local marginalization. Indeed, social networks have been posited as critical for navigating unwelcoming environments, as well as the unwritten and invisible norms and practices needed to persist and succeed in these spaces (Matthew, 2016c; Gonzales, 2018; Johnson et al., 2018). Given that the percentage of Black and Hispanic Internet Users who use social media sites is higher than White Internet users engaged in social media (Pew Research Center, 2018), there is substantial potential for social media to provide platforms for engagement of African-American and Latinx individuals in social networks and for promoting access and success of individuals from diverse backgrounds in the academy, including specific areas of interest such as the sciences.

Social Media and Building Diverse Communities

Many disciplines and units in academia have low structural diversity, or low numbers of individuals from diverse groups, especially in the sciences (Moreno et al., 2006; Whittaker et al., 2015; Li and Koedel, 2017). This lack of diversity contributes to recognized gaps that exist in the academy for the construction and cultivation of critical diverse communities. Social media have significant power to support the building and cultivation of networks for individuals underrepresented in particular spaces. “It connects academics of color to one another and offers an opportunity for scholars, activists and writers” to engage in meaningful ways and around meaningful topics (Matthew, 2016a, p. 107–108). These platforms can, thus, help fill gaps of low representation, as well as promote the potential to connect to critical political guidance and heuristic knowledge needed to navigate barriers and obstacles in these environments (Lemon, 2014; Matthew, 2016b; Johnson et al., 2018). Additionally, social media spaces have been recently posited as “a powerful tool in a larger strategy to dismantle” barriers such as “any systemic structures perpetuating the marginalization of women in science” (Yammine et al., 2018, p. 162), and I would argue this extends to multiple groups underrepresented in the academy.

In addition to cultivating connections in specific disciplines or the academy at large, the utilization of social media is “a way we can engage with and connect our science and research to a massive, real-time global network” (Darling and Rummer, 2015, p. 256). The potential to connect nationally and internationally via social media expands boundaries exponentially. “The increasing use of mobile technology and access to social media with smart phones can allow scientific information to overcome culture or infrastructure limitations” that scientists may encounter globally (Darling and Rummer, 2015, p. 259). This ability is particularly powerful for individuals underrepresented in particular environments, e.g., diverse individuals in science. In addition to connecting these scholars for mutual engagement and support, these platforms serve “as a public, uncurated archives of the experiences” of scholars of color (Matthew, 2016b, p. 241), which can also serve as a resource beyond the individual and communities of scholars of color themselves.

Connections Between Networked Communities and Critical Scholarly Practices

In a treatise on “weak ties,” which may in many ways be typical of many social media-based interactions, Granovetter (1973) argued that “small-scale interaction becomes translated into large-scale patterns, and that these, in turn, feed back into small groups” (p. 1360). This understanding of the potential of bilateral and network-based weak ties, may be one aspect of engagement in social media that can serve to provide connection and support for underrepresented and marginalized scholars in the academy. In this regard, Matthew (2016a) speaks of how although she initially engaged on the Twitter™ platform for what may be considered more traditional scholarly motivations, i.e., to find an audience for her work and to connect to information about related work, she found a community of Black “readers and thinkers,” as well as “role models and mentors” (p. 102). Such experiences speak to the power of using digital spaces to intentionally cultivate communities to support the success of individuals underrepresented in particular spaces and in the academy as a whole. In this regard, Matthew (2016a) argues that “careful, considered engagement with social media can help women of color as they navigate the tricky terrain of the academy…as they build academic portfolios and develop relationships that will sustain them through their pre-tenure years and during the midcareer years when the demands of service are more pressing” (Matthew, 2016a, p. 105).

It is this power of Twitter™ and other social media platforms to connect individuals who are underrepresented in particular academic spaces and to serve as a real counterbalance to the limitations presented by local deficits in structural diversity and numerical representation that I extol. There are numerous potential outcomes of such engagement. Such outcomes include that individuals can build needed networks, which “are critical to nurture oneself and cultivate an academic identity that aligns core values and beliefs” (Lemon, 2014, p. 52). Relatedly, participants also can cultivate “their own kind of peer review, one that carries with it the weight of social justice” (Matthew, 2016a, p. 111). Additionally, social media may provide a rich “playground” in which to live “life on the margins,” as described by Matthew (2016a). The “work” of impacting the academy is not singular work—it takes a community to impact a community. This is where the “gathering spaces” and “communal work” facilitated by connections made in social media spaces such as Twitter™ emerge. These are the spaces where the work needed to promote, sustain, and increase the value of diversity in science and the academy can take true root. These are the spaces where such work can be amplified, draw support, and facilitate identification of additional individuals to engage.

Scholarly Approaches for Social Media Engagement

There are frequent, and sometimes readily accepted, arguments in academia that engagement in social media and digital platforms such as blogs and other social network-based platforms is a distraction to the “real” or “legitimate” work of scholars (Singh, 2013; Veletsianos, 2013; Williams and Woodacre, 2016). Much of this angst about whether such engagement is a valuable use of time or not is related to our traditional practices in the academy of valuing what we can readily quantify. However, other scholars are avid users and defenders of digital platforms as “scholarship” or at the very least complementary to their scholarly endeavors (Lemon, 2014; Carrigan, 2017). This specific point may be particularly critical in regards to the benefits of engagement of underrepresented individuals who may lack the benefits of critical mass and, thus, a decreased likelihood of finding local support for scholarly success.

Social media also serve for scholars as “spaces in which they enact and pursue their scholarship in a visible manner” (Veletsianos, 2013, p. 645). Specific examples include finding and sharing publications—particularly in a timely fashion and ones to which one might not otherwise be exposed, ongoing discussions of ideas and events, rapid, and ongoing feedback on developing ideas, as well as invitations to present one's work or to collaborate (Priem and Costello, 2010; Veletsianos, 2013; Matthew, 2016a; Carrigan, 2017; Johnson et al., 2018; Shiffman, 2018). Matthew (2016b) describes her use of social media as “a proving ground for working out ideas that can lead to innovative research” (p. 244). Furthermore, she explains that “if you're doing it right (focusing on ideas and questions instead of just navel gazing), blogging and tweeting pulls you into a more careful consideration of ideas…with incredibly low stakes” (Matthew, 2016a, p. 110). Whereas Matthew focuses on the low stakes of engagement, there is also real potential for significant payoff from cultivating social networks related to professional success that may be of particular advantage to scholars of color who can actively nurture networks of critical mass in these spaces.

Apart from these uses, there are direct personal benefits to scholars for engaging in such platforms, which promote connected communities and scholarly practices that arguably are beneficial for all academics. These benefits include promotion of new materials, individual and collaborative curating of materials for future use in scholarly activities, and finding research collaborators. Promoting one's recent journal articles, books, and book chapters is a go-to reason that many engage in digital platforms (Matthew, 2016a; Williams and Woodacre, 2016; Carrigan, 2017). In an analysis of Twitter™ citations based on the sharing of links to a peer-reviewed article, Priem and Costello (2010) found that scholars use digital platforms to contribute to rapid conversations around particular scholarship. In fact, 40% of Twitter™ citations occurred within the first week of an article being available and shared (Priem and Costello, 2010). Tweets and blogs have particular utility for promoting materials such as book chapters, which sometimes are more difficult to find or access than peer-reviewed journal articles (Dunleavy, 2017). Considering targeted curation of materials, Carrigan (2017) describes it as follows: “Having my notes online also makes them extremely easy to search, providing a fantastic resource when I am writing papers and chapters.” As an extension, collaborative curation can support team scholarly work, while simultaneously serving as a public resource. Individuals can also use social media engagement to identify collaborators. Research collaborations have been shown to be positively correlated with performance and productivity (Abramo et al., 2017); yet, underrepresented scholars report having reduced opportunities to collaborate with local colleagues (Zambrana et al., 2015). Thus, collaborative engagement and curation facilitated by social media platforms can serve as a particularly effective resource for connections and access to information highly relevant to isolated scholars for groups underrepresented in science and the academy.

Social media engagement has significant potential for serving as a tool for some scholars to actively promote timely progression of scholarly goals. For example, scholars frequently discuss using tweets or threads as a “tweeting as writing” tool (Fleming, 2017; Montgomery, 2017a,b). In fact, Daniels (2013) traced her process of tweeting about a topic at a conference, which led to the development of a series of blog posts that she ultimately developed into a peer-reviewed journal article. She described this as an “example of the changing nature of scholarship” (Daniels, 2013). The use of social media platforms to promote writing, conference participation, and other traditional forms of scholarship is an extension of the use of other scholarly forums such as attendance or presentations at conferences for preparation for and advancing of one's scholarship (Gross and Fleming, 2011; Ekins and Perlstein, 2014; Collins et al., 2016). Social media-facilitated practices include receiving “real-time feedback” and the opportunity to consider and integrate others input (Jochum, 2018). While these benefits and tools of engaging in social media have potential to work effectively for all scholars, those individuals from groups underrepresented in the academy may find added value in readily connecting to scholars with shared experiences, identities, or diversity-related research agendas. The use of such networks for supporting the development of scholarship can have significant implications for underrepresented scholars who have limited local networks, lack local support and/or face hostility (Matthew, 2016c; Gonzales, 2018).

The specific uses of particular platforms can depend on intended outcomes. For example, Twitter™ is largely a public platform, unless one chooses to have a private account, whereas Facebook™ can be used for facilitating closed groups. Depending on whether the purpose is to facilitate wide-ranging engagement for seeking broad input, or to facilitate more exclusive conservations around issues that may be sensitive or political, a particular platform may better serve intended goals or outcomes. According to Crystal Fleming, her engagement on Twitter™ during work on a recent project was beneficial in that “comments and interaction…received from tens of thousands of people definitely shaped my thinking about the book while it was being written” (Jochum, 2018). Such active engagement of individuals, in and out of the academy, through social media and other such digital platforms allows scholars, who choose to participate, to get formative feedback that can shape their work in meaningful ways as it is being produced and edited. Others have embraced social media as “a natural outlet for thinking that didn't necessarily fit in traditional academic spaces” (Matthew, 2016a, p. 102), or for which local communities of support are lacking. None of these arguments are to suggest that social media engagement is a requirement for all scholars; yet it can serve as a viable and meaningful avenue for connection and the building of networks for those scholars who choose to engage, and particularly for scholars of color for whom critical mass continues to be a serious deficit in higher education.

Case Studies: Hashtagging to Action

Social media and digital platforms have become valuable resources for individuals underrepresented in particular environments to congregate for support, to build community, and increasingly as places of collaboration and advocacy. These platforms provide crucial means to identify a critical mass, albeit a “virtual” one (Zax, 2014; Whittaker et al., 2015). Nonetheless, the cultivation of this critical mass can be vital for supporting success and hastening the agency needed to build and sustain diversity in key areas, such as science (Whittaker and Montgomery, 2012; Allen-Ramdial and Campbell, 2014). Isolation and “only-ness” can be a stumbling block for many individuals from underrepresented groups in academic spaces (Cohen and Garcia, 2008; Campbell, 2014; Johnson et al., 2018). The ability of “virtual” spaces to fully substitute for a local critical mass and connection to local supporters and mentors, which are critical for obtaining local heuristic knowledge important for navigating particular spaces, has been challenged (Whittaker and Montgomery, 2014; Whittaker et al., 2015; Zambrana et al., 2015). Yet, these virtual connections and communities can be very important as one tool in a larger set for successfully navigating paths, especially in ways that honor one's identities and culture(s) of origin.

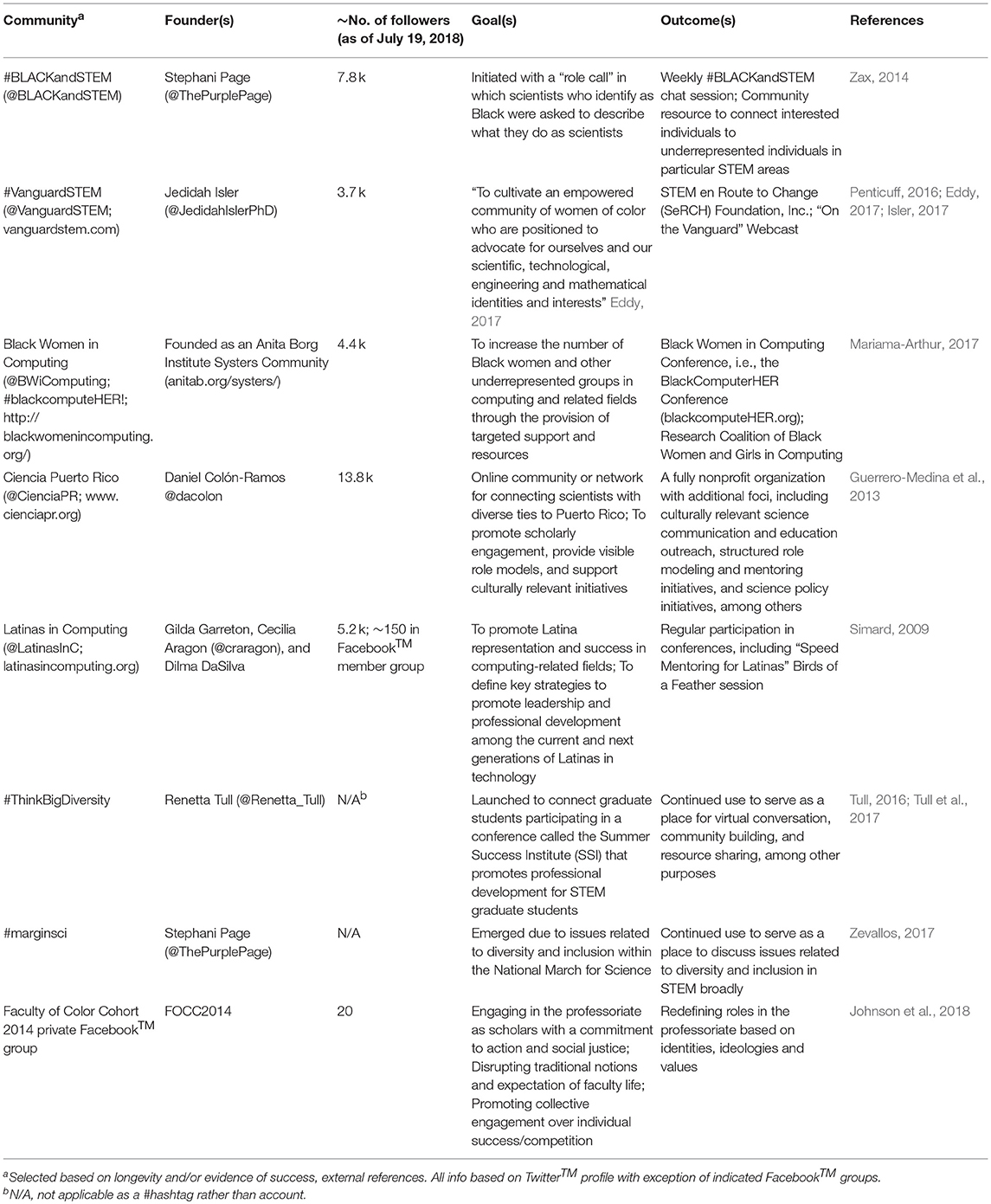

A number of robust communities have emerged whose missions are centered on promoting success of minoritized individuals and communities in the sciences and larger academy (Table 1). Central themes of potential and burgeoning success include the building of communities of critical mass and active connection, cultivating success through mentoring and support, promoting active self-definition and agency, and advocacy.

Table 1. Select examples of social media and digital platform-supported communities to promote success and sustain diversity in the sciences.

Building Communities

Several communities have been initiated and cultivated on Twitter™ to increase structural diversity, or numerical representation of different groups (Hurtado et al., 1998), and to promote connections between individuals from backgrounds underrepresented in the sciences. A long-standing community in this regard is #BLACKandSTEM (@BLACKandSTEM), which was started by biochemist and biophysicist Stephani Page (@ThePurplePage). Other examples related specifically to computing include Black Women in Computing (@BWiComputing), which is a community created in 2011 to increase the number of Black women and other underrepresented groups in computing and related fields through the provision of targeted support and resources (Mariama-Arthur, 2017), and Latinas in Computing (@LatinasInC), which serves to promote Latina representation, professional development, and success in computing-related fields (Simard, 2009). Ciencia Puerto Rico (CienciaPR; www.cienciapr.org) was created in 2006 as an online community or network for connecting scientists with diverse ties to Puerto Rico (Guerrero-Medina et al., 2013). So many of these communities fit the description for #BLACKandSTEM in which the community is more than a hashtag or Twitter™ handle–it is indeed a robust community, a scholarly family of sorts (Zax, 2014). The emergence of similar communities of late, e.g., #LatinxinSTEM (@LatinxinSTEM), #DiversityinSTEM, #BlackWomenInSTEM (@BlackWomenSTEM), and others, suggests the utility that others see in having such established and public platforms for engagement, support and advocacy.

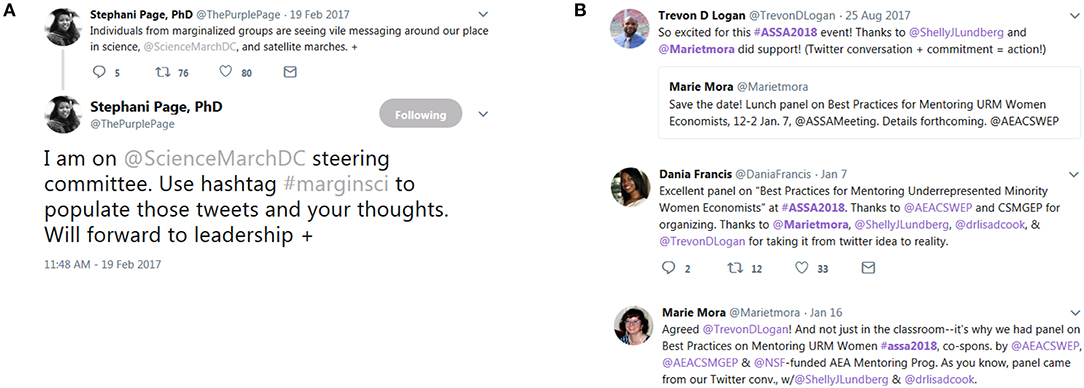

In addition to these specific communities associated with a particular hashtag, minoritized scholars also use the combination or intersection of distinct hashtags, including those associated with larger communities of scholars or individuals, to find other scholars or amplify the voices of people of color within particular communities of interest or practice. Common examples of intersections of hashtags include the following: #BLACKandSTEM × #WomenInSTEM, #nationalmentoringmonth × #BLACKandSTEM, #BLACKandSTEM × #InternationalWomensDay, #WCW × #VanguardSTEM, #BLACKandSTEM × #ScholarSunday, #WOCinSTEM × #WomenInSTEM × #BlackANDSTEM. Sometimes, these engagements at the intersection result in new communities or digital landing places altogether. For example #BLACKandSTEM founder Page initiated a new hashtag, i.e., #marginsci, based on controversies related to diversity and inclusion within the National March for Science (#ScienceMarch) in 2017 and related robust conversations that developed at the intersection of #MarchforScience and #BLACKandSTEM (Figure 1A). Notably, blogs and hashtags have been noted as potentially beneficial tools for using digital platforms for broader impacts (Bik and Goldstein, 2013).

Figure 1. Select Twitter™ Conversations as Evidence for Origin of Social Media Outcomes for Promoting Diversity and Community Engagement of Minoritized Individuals in the sciences. (A) New conversations or communities can be supported by the intersection of distinct hashtags. The #marginsci hashtag was created by Stephani Page, PhD (@ThePurplePage) in response to conversations occurring at the #BLACKandSTEM and #ScienceMarch (@ScienceMarchDC) intersection. Such initiations of hashtags can rapidly support conversation, advocacy and community building. (B) Social media interactions can serve as a stimulus for development of in-person events. Conversations on social media can lead to opportunities to engage in-person and/or to the development of in-person events such as a panel on “Best Practices on Mentoring Underrepresented Minority Women” that was initiated by conversation between Trevon Logan (@TrevonDLogan), Marie Mora (@Marietmora), Shelly Lundberg (@ShellyJLundberg) and Lisa D. Cook (@drlisadcook), among others.

Cultivating Success: Mentoring and Support

Social media engagement also is immensely useful for promoting “self-reflection, solution-gathering, and peer-mentoring” (Tull et al., 2017). Regarding the latter, engagement in such platforms can develop into recognized mentoring. Daniels (2013) describes that regularly blogging became “a mentoring platform, where early career scholars often get started with blogging and then go create their own.” Regular sharing of information on platforms such as Twitter™ also can result in coaching or mentoring such that other scholars actively change their own professional practices (Anyogu, 2018; Johnson et al., 2018). The #BLACKandSTEM community holds a regular chat session to actively promote meaningful exchange and reciprocal mentoring in which topics of interest to gaining access to and succeeding in a broad range of STEM disciplines are discussed (Zax, 2014). Additionally, #BLACKandSTEM has served as an increasingly engaged resource to connect interested individuals to underrepresented individuals in particular STEM areas. This resource function has drawn broad interest, including from journalists and science educators seeking specific scientific interests or to connect with African American role models or practitioners from STEM disciplines (Zax, 2014). The online site for CienciaPR also uses a number of means for engaging participants, including messaging, blogs, and member matching for mentoring and other interactions (Guerrero-Medina et al., 2013). One of the noted outcomes of the efforts of Latinas In Computing is a reduction in feelings of isolation and increased access to relevant mentoring for participants (Simard, 2009).

Promoting Self-Definition and Agency

The building and cultivation of diverse communities via social media and digital platforms provide ongoing engagement that leads to beneficial outcomes such as community validation and promotion of self-definition. Indeed, astrophysicist Jedidah Isler (@JedidahIslerPhD) founder of #VanguardSTEM describes that indeed she “wanted to create a space where women of color at different levels of their STEM journey were able to tell their story, give advice and give encouragement” (Penticuff, 2016, p. 46; Table 1). The power of self-definition through the telling of one's own story is one outcome of engaging publicly in social media spaces. Participants in BWiComputing activities also reported positive outcomes related to self-definition, including “affirming the intersectionality of race and gender, and owning the identity and role of black women in computing” as well as “collectively creating an action plan of solutions to promote black women in computing” (http://blackwomenincomputing.org/events/black-women-in-computing-conference-2017/). Additionally, participants in the private Faculty of Color Cohort 2014 (FOCC2014) Facebook™ group describe the influence of both self-definition and engaging collective agency on redefining personal existence in academic spaces based on social identities and in values-based ways (Table 1; Johnson et al., 2018). Notably, this group and Latinas in Computing were initiated largely as networks primarily focused on mentoring and peer support, whereas some of the other groups started in public social media spaces to invite mass participation with an eye to seeking overall structural change (Table 1).

The engagement in these public and private spaces in such ways that are based on identifiable collaborative action or agency can lead to additional outcomes. For example, the #marginsci hashtag was a direct action that resulted from hostility experienced by minoritized individuals seeking a focus on or discussion about race and the “place in science” for marginalized groups during planning for the Science March in 2017 (Figure 1A). Such actions are a direct example that “Twitter™ conversation + commitment = action!” (Logan, 2017; Figure 1B).

Community Advocacy

Using social media engagement to build and cultivate communities focused on communal advocacy and support is a recurring theme in cases where the goal is to promote access and success of individuals from underrepresented groups. Isler has argued that the “vision of #VanguardSTEM is to cultivate an empowered community of women of color who are positioned to advocate for ourselves and our scientific, technological, engineering and mathematical identities and interests” (Eddy, 2017). She also describes #VanguardSTEM as powerful for cultivating “an empowered community prepared to advocate” for self-defined interests and identities in STEM (Isler, public comment at 2018 Emerging Researchers Nationals Conference in STEM). The FOCC2014 group used their digital platform-based engagement for individual and reciprocal advocacy to support success of faculty of color in the academy (Johnson et al., 2018).

Occasionally, social media interactions lead to advocacy for critical engagement of diverse groups beyond a local group or for stimulating key in-person events, which would be difficult for isolated individuals from underrepresented backgrounds. The use of the #blackcomputeHER! hashtag by the BWiC community is one example of how online engagement extended the impact of the conference beyond those in attendance locally. The BlackComputerHER community is actively committed to activities beyond building networks, including advocacy and leadership development. A similar use of the use of #ThinkBigDiversity hashtag for “Hacking Diversity in STEM” to brainstorm solutions to challenges associated with graduate studies for underrepresented STEM scholars and the promotion of diversity using the “Think Big” hackthon concept was initiated by founder Dr. Renetta Tull (@Renetta_Tull) as a part of the Summer Success Institute (SSI) that promotes professional development for diverse STEM graduate students (Tull, 2016; Tull et al., 2017; Table 1). The social media involvement and advocacy of SSI scholars, and others participating and connecting virtually, including through the use of the #ThinkBigDiversity hashtag has become a “tool for engagement and retention” (Tull, 2016). Additionally, the associated activities leverage key social science theories related to promoting positive outcomes through communities of critical mass, including through active advocacy to promote an increased sense of belonging and increasing cultural wealth of individuals (Tull et al., 2017).

In regards to stimulating advocacy for key in-person events that draw on the critical mass of dispersed individuals from underrepresented backgrounds, a panel, “Best Practices for Mentoring Underrepresented Minority Women Economists,” at the 2018 American Economic Association/Allied Social Science Associations (ASSA) annual meeting traces its roots to a conversation started on Twitter™ (Logan, 2017; Francis, 2018; Mora, 2018; Figure 1B). An online conversation between several society members resulted in the idea for a panel topic and additionally involved inviting individuals whose work was known to organizers of the session largely via engagement and conversation on Twitter™. Thus, the connection and engagement via social media resulted in action that produced recognized scholarly currency, i.e., a group of individuals collaboratively organizing and chairing a panel at a national disciplinary society meeting. Other instances of social media engagement resulting in the production of recognized scholarly currency includes reciprocal invitations for seminar or conference presentations (Johnson et al., 2018).

Benefits and Outcomes of Social Media Engagement of Individuals From Diverse Backgrounds

Apart from concerns about time spent engaging in social media and other digital platforms and in addition to the largely group benefits described for diverse populations above, there are emerging individual benefits that are gaining reception. Social media engagement truly can be a form of cultivated peer review. This cultivated input can be critical as it is feedback that provides key insights into the efficacy of key aspects of the work important to the scholar, including social justice advancement and engagement of public audiences (Veletsianos, 2013; Matthew, 2016a; Johnson et al., 2018; Shiffman, 2018).

Engagement in social media platforms that promotes connections to and interactions with others from communities underrepresented in science contributes to the acquisition of navigational capital (Tull et al., 2017) and promotes transformational resistance or engagement that recognizes and critiques oppression while pursuing social justice (Solorzano and Delgado Bernal, 2001). Notably, the culture wealth model of Yosso (2005) positions navigational capital as important for success in challenging academic spaces such as science communities. This valued cultivation of and access to such spaces provides an opportunity, and perhaps even a responsibility, to “not simply replicate current practices but to make critical interventions that can materially impact how the academy values and fosters diversity” (Matthew, 2016a, p. 109). In this regard, “social media is best when it leads to work that can make an impact on the margins while causing ripple effects that might reach the center” (Matthew, 2016a, p. 113).

Social media has also been described as a place to “bear witness” (Matthew, 2016a, p. 113), particularly about existing in the academy as a member of an underrepresented group. Indeed social media and digital platforms may provide a counterspace for “silenced” individuals to connect and provide mutual validation. In some sense, these may indeed be highly valued platforms for cultivating agency and without restrictions imposed by physical boundaries or impediments of low representation. Related to the role of social media as a place of witnessing, Figueroa (2015) describes Lugones concept of the “act of “faithful witnessing” as a method of collaborating with those who are silenced” (p. 642). Figueroa argues that Lugones positions faithful witnessing as “a strategy through which oppressed peoples form coalitions in order to combat multiple and systematic oppressions” (2015, p. 642). Furthermore, Figueroa (2015) argues that “it is in the faithful witnessing of the moments of resistance, failures, deceptions, triumphs, violence, love, and small histories that one one actively participates in the affirmation of other voices and the substantiation of other truths” (p. 644). Such faithful witnessing can be developed, cultivated and self-archived through social media or other digital platforms. Indeed, the case studies introduced herein provide evidence that such faithful witnessing is serving a powerful role to connect, support and promote a broad range of individuals from diverse groups in science.

Mitigating Potential Challenges Associated With Social Media Engagement for Diverse scholars

To promote the best outcomes of engaging in social media or digital platforms, it is important to cultivate engagements such that they are diverse functioning networks rather than echo chambers (Singh, 2013, p. 2) or communities founded on homophily (Veletsianos and Kimmons, 2012; Williams and Woodacre, 2016). One means of mitigating potential negatives of social media engagement is to utilize it as an “engaged scholar” with structured and intentional reflection and activity (Rockquemore, 2015). Additionally, given the reality of life as a scholar from an underrepresented background it can be of critical importance to recognize a “need to be conscious and intentional about when, where and how you engage” (Rockquemore, 2015).

Crystal Fleming (@alwaystheself), who blogged regularly and additionally is very active on Twitter™, states that “faculty of color, in particular, have to be mindful of the challenges posed by targeted attacks and trolling—and academic institutions have to do a lot more to protect faculty from harassment. We have to be vigilant in protecting academic freedom, particularly in the present political climate” (Jochum, 2018). In addition to ensuring that faculty are protected, institutions also need to tend to recognition: it is “more than simply governing how faculty work in social media, universities need to figure out how to support and reward this work at its best” (Matthew, 2016a, pp. 246–247). The means by which institutions will or should reward this work which is seen by some as scholarship, but others as just social engagement for personal benefit, is an area that is still highly debated.

Often when discussing a need for “credit” for engagement in social media, the discussion turns to altmetrics. However, given that traditional engagement of altmetrics draws on metrics related to some form of social media engagement of traditional scholarly communication forms, some resistance exists to using these metrics broadly for measures of impact (e.g., Haustein et al., 2016; Robinson-Garcia et al., 2018). In this regard, arguments have been advanced to consider social media metrics as an alternative to altmetrics (Wouters et al., 2018). Meaningful discussions include a need to distinguish between access, appraisal, and application in assessing impact of social media engagement (Haustein et al., 2016).

Of greater applicability to the use of social media for network building and support related to diverse populations that is advanced here, some discussion of using network-based analysis of researcher or stakeholder engagement in social media or digital platforms to assess community building, active involvement, or larger societal impact may be advisable (Robinson-Garcia et al., 2018). Indeed the use of such approaches may advance understanding of “the social interactions of researchers,” which in turn may facilitate understanding “the diverse contexts in which researchers potentially participate” (Robinson-Garcia et al., 2018, p. 3). This knowledge could be very helpful for intentional structuring and cultivation of communities designed to promote participation and success-based outcomes. Certainly, such network-based analyses could “inform about researchers' networks and engagement, providing helpful information for the assessment of their potential societal impact” (Robinson-Garcia et al., 2018, p. 7). These insights would be beneficial for assessment of the efficacy of current networks, many of which have emerged organically or based on grassroots efforts, and identification of meaningful community properties and dynamics to inform design of future networks. Indeed, universities or disciplinary societies may explore whether this type of network building and cultivation should be included in intentional academic and disciplinary strategies. To do so may be a good use of the “weak ties” that are typical in some social media spaces and digital platforms, and which are correlated with “individual opportunities and to their integration into communities” (Granovetter, 1973, p. 1378).

Conclusions

The diverse examples of the uses of social media for providing a range of meaningful outcomes of digital engagement are numerous. The various ways in which digital media platforms such as social media have been engaged to promote diversity and communities of support and advocacy align with the idea that many of these practices “could be characterized as small acts of defiance against institutional norms, tenure and promotion practices, and the status quo” (Veletsianos, 2013, p. 648). The latter is particularly true as these spaces serve as a means to build the critical mass that has continued to by stymied by practices and histories of exclusion and bias in the academy, such that demographics in science and the larger academy still are not at parity with that of the nation. While the use of social media have continued to expand in the academy as a whole to provide amplification of and alternative means to more commonly accepted scholarly practices and sharing of scholarly work, the use of these platforms as counterspaces to connect, collaborate, mentor, support and advocate for individuals from groups underrepresented in the academy is rapidly increasing. It is this power of social media and digital platforms for promoting connectivity of individuals in diverse functioning networks in order to bridge gaps related to underrepresentation that holds significant promise.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Funding

Research in the Montgomery laboratory, including efforts to promote diversity, inclusion and evidence-based mentoring is conducted as a part of broader impact work funded by the National Science Foundation (grants no. MCB-1515002, MCB-1243983, and IOS-1557324 to BM) and by support from the Michigan State University Foundation.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I am thankful to the #VanguardSTEM team for engagement in conversation regarding their work and mission. I thank Tricia Matthew for providing access to her work in press. Additionally, I thank the individuals whose tweets are included in Figure 1 for providing permission for their use. I owe a gratitude of thanks to a community of AAAS Science & Technology Policy Fellows who were the first to actively and persistently encourage me to use a digital platform to share and to cultivate conversations as a complement to in-person engagement opportunities.

References

Abramo, G., D'Angelo, A. C., and Murgia, G. (2017). The relationship among research productivity, research collaboration, and their determinants. J. Informetr. 11, 1016–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2017.09.007

Allen-Ramdial, S. A., and Campbell, A. G. (2014). Reimagining the pipeline: advancing STEM diversity, persistence, and success. Bioscience 64, 612–618. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biu076

Anyogu, A. (2018). “@BerondaM A mentor's Mentor. My Decision to Embed Mentoring into My Teaching is Inspired by not just her Words but her Practice. Thank you.” Available online at: https://twitter.com/intentionalacad/status/971672263761235969

Baldwin, J. (2017). “Culture, prejudice, racism, and discrimination” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication, ed J. Nussbaum (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 25.

Bik, H. M., and Goldstein, M. C. (2013). An introduction to social media for scientists. PLoS Biol. 11L:e1001535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001535

Côté, I. M., and Darling, E. S. (2018). Scientists on twitter: preaching to the choir or singing from the rooftops? Facets 3, 682–694. doi: 10.1139/facets-2018-0002

Campbell, A. G. (2014). “STEM Diversity and Critical Mass” in IMSD View 4: 1. Available online at: https://www.brown.edu/initiatives/maximize-student-development/sites/maxstuddev/files/IMSD_View_V4_I3.pdf

Carrigan, M. (2017). “Social Media Is Scholarship” in Chronicle of Higher Education. Available online at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/Social-Media-Is-Scholarship/241467?cid=rclink (Accessed October 17, 2017).

Cohen, G. L., and Garcia, J. (2008). Identity, belonging, and achievement: a model, interventions, implications. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 17, 365–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00607.x

Collins, K., Shiffman, D., and Rock, J. (2016). How are scientists using social media in the workplace? PLoS ONE 11:e0162680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162680.t001

Daniels, J. (2013). “From tweet to blog post to peer-reviewed article: how to be a scholar now,” in LSE Impact Blog. Available Online at: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2013/09/25/how-to-be-a-scholar-daniels/ (Accessed March 2, 2018).

Darling, E. S., and Rummer, J. L. (2015). “Strategically using social media” in Success Strategies from Women in STEM: A Portable Mentor, eds P. A. Pritchard, C. G. Grant (Waltham, MA: Elsevier, Inc.), 255–298.

Dunleavy, P. (2017) “Using social media and open access can radically improve the academic visibility of chapters in edited books,” in Writing for Research. Available online at: https://medium.com/@write4research/using-social-media-and-open-access-can-radically-improve-the-academic-visibility-of-chapters-in-74030d17bc4d (Accessed March 8, 2018).

Eddy, C. (2017). “VanguardSTEM empowers women of color,” in Tech Diversity Magazine. Available Online at: https://techdiversitymagazine.org/2017/06/28/vanguardstem-empowers-women-of-color/ (Accessed April 19, 2018).

Ekins, S., and Perlstein, E. O. (2014). Ten Ten simple rules of live tweeting at scientific conferences. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10:e1003789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003789

Figueroa, Y. C. (2015). Faithful witnessing as practice: decolonial readings of shadows of your black memory and the brief wondrous life of Oscar wao. Hypatia 30, 641–656. doi: 10.1111/hypa.12183

Fleming, C. M. (2017). “There are these Successive, at Times, Maddening, Stages of Outlining, Drafting, “Going Fishing” for my own Tweets, Integrating Scholarly and Pop Culture References, Re-Ordering the Structure, Turning Tweets into Prose, Editing for Clarity, Deleting Sections.” Available online at: https://twitter.com/alwaystheself/status/935985437281316868

Francis, D. (2018). “Excellent Panel on “Best Practices for Mentoring Underrepresented Minority Women Economists” at #ASSA2018. Thanks to @AEACSWEP and CSMGEP for Organizing. Thanks to @Marietmora, @ShellyJLundberg, @drlisadcook, & @TrevonDLogan for taking it from Twitter Idea to Reality.” Available online at: https://twitter.com/DaniaFrancis/status/950121006278070272

Gin, K. J., Martínez-Alemán, A. M., Rowan-Kenyon, H. T., and Hottell, D. (2017). Racialized aggressions and social media on campus. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 58, 159–174. doi: 10.1353/csd.2017.0013

Gonzales, L. D. (2018). Subverting and minding boundaries: the intellectual work of women. J. High. Educ. 89, 677–701. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2018.1434278

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 78, 1360–1380. doi: 10.1086/225469

Gross, N., and Fleming, C. (2011). “Academic conferences and the making of philosophical knowledge,” in Social Knowledge in the Making, eds C. Camic, N. Gross, and M. Lamont (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 151–180.

Guerrero-Medina, G., Feliú-Mójer, M., González-Espada, W., Díaz-Muñoz, G., López, M., Díaz-Muñoz, S. L., et al. (2013). Supporting diversity in science through social networking. PLoS Biol. 11:e1001740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001740

Haustein, S., Bowman, T. D., and Costas, R. (2016). “Interpreting “altmetrics”: Viewing acts on social media through the lens of citation and social theories” in Theories of Informetrics and Scholarly Communication: A Festschrift in Honor of Blaise Cronin, ed C. R. Sugimoto (Berlin: De Gruyter), 372–406.

Holmberg, K., and Thelwall, M. (2014). Disciplinary differences in twitter scholarly communication. Scientometrics 101, 1027–1042. doi: 10.1007/s11192-014-1229-3

Hurtado, S., Milem, J. F., Clayton-Pedersen, A. R., and Allen, W. R. (1998). Enhancing campus climates for racial/ethnic diversity: educational policy and practice. Rev. High. Educ. 21, 279–302. doi: 10.1353/rhe.1998.0003

Isler, J. (2017). “So what is VanguardSTEM anyway?” in VanguardSTEM Conversations. Available online at: https://conversations.vanguardstem.com/so-what-is-vanguardstem-anyway-7877a0c75e03

Jochum, G. (2018). “Demystifying Race, Online and in the Classroom,” in SBU Happenings. Available online at: http://www.stonybrook.edu/happenings/facultystaff/demystifying-race-online-and-in-the-classroom/?spotlight=hero&utm_content=buffer770e6&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer (Accessed March 9, 2018).

Johnson, J. M., Boss, G., Mwangi, C. G., and Garcia, G. A. (2018). Resisting, rejecting, and redefining normative pathways to the professoriate: Faculty of color in higher education. Urban Rev., doi: 10.1007/s11256-018-0459-8. [Epub ahead of print].

Lemon, N. (2014). “Sending out a tweet: Finding new ways to network in academia” in Being “In and Out”: Providing Voice to Early Career Women in Academia, eds. N. Lemon and S. Garvis (Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers), 43–54.

Li, D., and Koedel, C. (2017). Representation and salary gaps by race-ethnicity and gender at selective public universities. Educ. Res. 46, 343–354. doi: 10.3102/0013189X17726535

Logan, T. D. (2017). “So excited for this ASSA2018 event! Thanks to @ShellyJLundberg and @Marietmora did support! (Twitter conversation + commitment = action!).” Available Online at: https://twitter.com/TrevonDLogan/status/901198681113845760

Mariama-Arthur, K. (2017). “See how this Coalition is Helping Black Female Techies” in Black Enterprise. Available online at: http://www.blackenterprise.com/coalition-helping-black-female-techies/ (Accessed July 19, 2018).

Matthew, P. A. (2016a). ‘Between star shine and clay’: On the promise and perils of social media. CLA J. 60, 101–117.

Matthew, P. A. (2016b). “Tweeting diversity: race and tenure in the age of social media” in Written/Unwritten: Diversity and the Hidden Truths of Tenure, ed P.A. Matthew (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press), 241–260.

Matthew, P. A. (2016c). “Written/Unwritten: Diversity and the Hidden Truths of Tenure, ed. P.A. Matthew (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press).

Montgomery, B. L. (2017a). “I, Too, Just Spent a Couple of Afternoons “Going Fishing' for My Own Tweets” for a Piece I'm Drafting. “Tweeting as Writing” is Real!”. Available online at. https://twitter.com/BerondaM/status/935990420869406720

Montgomery, B. L. (2017b). “Tweeting as Writing: TFW you're Working on a ‘Revise & Resubmit’ & Realize a Few Revisions You Need Can Be Copy & Pasted From Recent Tweets”. Available online at: https://twitter.com/BerondaM/status/845776041004208129

Montgomery, B. L. (2018). Pathways to transformation: institutional innovation for promoting progressive mentoring and advancement in higher education. Susan Bulkeley Butler Center for Leadership Excellence and ADVANCE Working Paper Series 1, 10–18.

Mora, M. (2018). “Excited to Share Panel on Best Practices in Mentoring URM Women, Spons. by @AEACSWEP, @AEACSMGEP & @NSF AEA Mentoring Progr. Panel (w/ C. Conrad, @BerondaM, I. Johnson) came from Twitter disc w/ @TrevonDLogan, @ShellyJLundberg, @Marietmora & @drlisadcook! https://www.aeaweb.org/about-aea/committees/cswep/programs/annual-meeting/roundtables”. Available online at: https://twitter.com/Marietmora/status/964624102710501378

Moreno, J. F., Smith, D. G., Clayton-Pedersen, A. R., Parker, S., and Teraguchi, D. R. (2006). The Revolving Door for Underrepresented Minority Faculty in Higher Education: An Analysis From the Campus Diversity Initiative. San Francisco, CA: The James Irvine Foundation.

Museus, S. D., and Truong, K. A. (2013). Racism and sexism in cyberspace: engaging stereotypes of Asian American women and men to facilitate student learning and development. About Campus 18, 14–21. doi: 10.1002/abc.21126

Penticuff, L. (2016). ‘Get out there and take the risk’: creating spaces of inclusion and equal opportunities in STEM. Divers. Act. 2, 44–46.

Pew Research Center (2018). Social Media Fact Sheet. Available online at: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/

Priem, J., and Costello, K. L. (2010). How and why scholars cite on Twitter. Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 47, 1–4. doi: 10.1002/meet.14504701201

Robinson-Garcia, N., van Leeuwen, T. N., and Ràfols, I. (2018). Using altmetrics for contextualised mapping of societal impact: from hits to networks. Sci. Public Policy, scy024. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scy024.

Rockquemore, K. A. (2015). “Let's Talk About Twitter,” in Inside Higher Ed. Available online at: https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2015/05/20/essay-issues-facing-young-academics-social-media (Accessed March 2, 2018).

Shiffman, D. S. (2018). Social media for fisheries science and management professionals: how to use it and why you should. Fisheries 43, 123–129. doi: 10.1002/fsh.10031

Simard, C. (2009). “Creating Change for Underrepresented Minorities in Technology: Latinas in Computing” in Fast Company. Available online at: https://www.fastcompany.com/1307697/creating-change-underrepresented-minorities-technology-latinas-computing

Singh, S. S. (2013). Tweeting To The Choir: Online Performance and Academic Identity. Paper presented at Internet Research 13: resistance + appropriation, Denver, CO.

Solorzano, D. G., and Delgado Bernal, D. (2001). Examining transformational resistance through a critical race and latcrit theory framework: chicana and Chicano students in an urban context. Urban Educ. 36, 308–342. doi: 10.1177/0042085901363002

Tull, R. G. (2016). Expanding the pipeline: PROMISE brings a new phase of ThinkBigDiversity to Maryland grad students. Comput. Res. News 28, 14–19.

Tull, R. G., Reed, A. M., Felder, P. P., Hester, S., Williams, D. N., Medina, Y., et al. (2017). “Hashtag #thinkbigdiversity: social media hacking activities as hybridized mentoring mechanisms for underrepresented minorities in STEM. in Paper Presented at the 124thASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Columbus, OH.

Tynes, B. M., Rose, C. A., and Markoe, S. L. (2013). Extending campus life to the internet: Social media, discrimination, and perceptions of racial climate. J. Divers. High. Educ. 6, 102–114. doi: 10.1037/a0033267

Van Noorden, R. (2014). Online collaboration: scientists and the social network. Nature 512, 126–129. doi: 10.1038/512126a

Veletsianos, G. (2013). Open practices and identity: evidence from researchers and educators' social media participation. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 44, 639–651. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12052

Veletsianos, G., and Kimmons, R. (2012). Networked participatory scholarship: emergent techno-cultural pressures toward open and digital scholarship in online networks. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 13, 144–166. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.10.001

Whittaker, J. A., and Montgomery, B. L. (2012). Cultivating diversity and competency in STEM: challenges and remedies for removing virtual barriers to constructing diverse higher education communities of success. J. Undergrad. Neurosci. Educ. 11, A44–A51.

Whittaker, J. A., and Montgomery, B. L. (2014). Cultivating institutional transformation and sustainable STEM diversity in higher education through integrative faculty development. Innov. High. Educ. 39, 263–275. doi: 10.1007/s10755-013-9277-9

Whittaker, J. A., Montgomery, B. L., and Martinez Acosta, V. G. (2015). Retention of underrepresented minority faculty: Strategic initiatives for institutional value proposition based on perspectives from a range of academic institutions. J. Undergrad. Neurosci. Educ. 13, A136–A145.

Williams, A. D., and Woodacre, M. A. (2016). The possibilities and perils of academic social networking sites. Online Info. Rev. 40, 282–294. doi: 10.1108/OIR-10-2015-0327

Wouters, P., Zahedi, Z., and Costas, R. (2018). “Social media metrics for new research evaluation” in Springer Handbook of Science and Technology Indicators, eds W. Glänzel, H. F. Moed, U. Schmoch, and M. Thelwall (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), arXiv:1806.10541v1[Preprint].

Yammine, S. Z., Liu, C., Jarreau, P. B., and Coe, I. R. (2018). Social media for social change in science. Science 360, 162–163. doi: 10.1126/science.aat7303

Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethn. Educ. 8, 69–91. doi: 10.1080/1361332052000341006

Zambrana, R. E., Ray, R., Espino, M. M., Castro, C., Douthirt Cohen, B., and Eliason, J. (2015). “Don't leave us behind”: The importance of mentoring for underrepresented minority faculty. Am. Educ. Res. J. 52, 40–72.

Zax, D. (2014). “BLACKandSTEM: The Hashtag As Community” in Fast Company. Available online at: https://www.fastcompany.com/3027122/blackandstem-the-hashtag-as-community.

Zevallos, Z. (2017). A Brief overview of #marginsci. Available online at https://othersociologist.com/a-brief-overview-of-marginsci/ (Accessed July 19, 2018).

Keywords: digital platforms, diversity, higher education, social media, social networks, sciences

Citation: Montgomery BL (2018) Building and Sustaining Diverse Functioning Networks Using Social Media and Digital Platforms to Improve Diversity and Inclusivity. Front. Digit. Humanit. 5:22. doi: 10.3389/fdigh.2018.00022

Received: 20 April 2018; Accepted: 21 August 2018;

Published: 11 September 2018.

Edited by:

Richard Holliman, The Open University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Enrique Orduna-Malea, Universitat Politècnica de València, SpainNicolás Robinson-Garcia, Universitat Politècnica de València, Spain

Copyright © 2018 Montgomery. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Beronda L. Montgomery, bW9udGcxMzNAbXN1LmVkdQ==

Beronda L. Montgomery

Beronda L. Montgomery