95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Digit. Health , 14 October 2021

Sec. Connected Health

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2021.688982

This article is part of the Research Topic Highlights in Connected Health 2021/22 View all 7 articles

Background: Volunteer programs that support older persons can assist them in accessing healthcare in an efficient and effective manner. Community-based initiatives that train volunteers to support patients with advancing illness is an important advance for public health. As part of implementing an effective community-based volunteer-based program, volunteers need to be sufficiently trained. Online training could be an effective and safe way to provide education for volunteers in both initial training and/or continuing education throughout their involvement as a volunteer.

Method: We conducted an integrative review that synthesized literature on online training programs for volunteers who support older adults. The review included both a search of existing research literature in six databases, and an online search of online training programs currently being delivered in Canada. The purpose of this review was to examine the feasibility and acceptability of community-based organizations adopting an online training format for their volunteers.

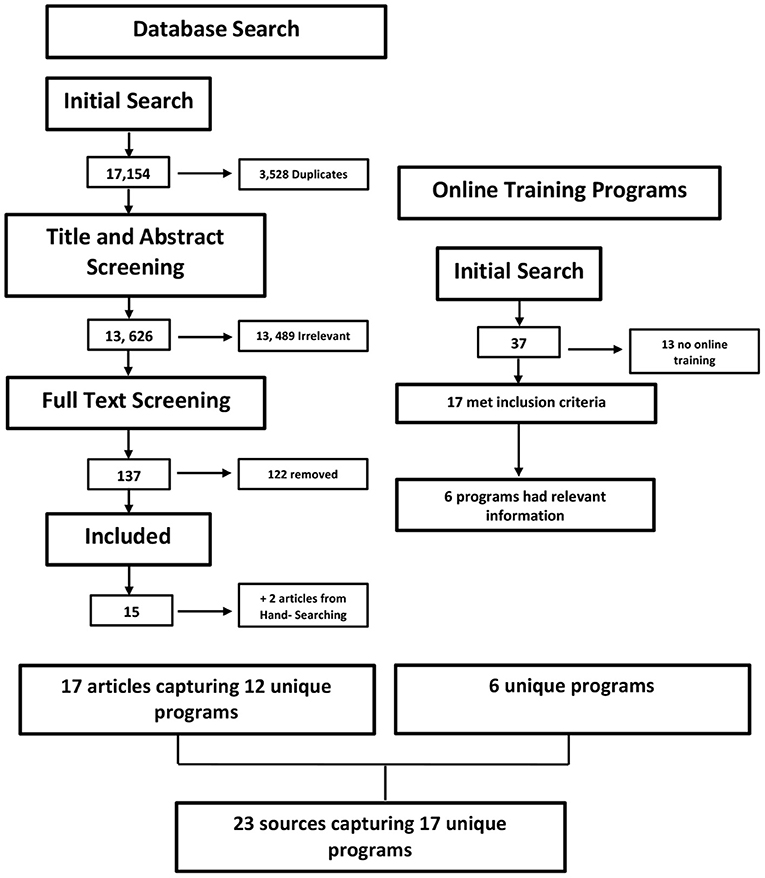

Results: The database search identified 13,626 records, these went through abstract and full text screen resulting in a final 15 records. This was supplemented by 2 records identified from hand searching the references, for a total of 17 articles. In addition to identifying Volunteers Roles and Responsibilities; Elements of Training; and Evaluation of Feasibility and Acceptability; a thematic analysis of the 17 records identified the categories: (1) Feasibility Promoting Factors; (2) Barriers to Feasibility; (3) Acceptability Promoting Factors; and (4) Barriers to Acceptability. Six programs were also identified in the online search of online training programs. These programs informed our understanding of delivery of existing online volunteer training programs.

Discussion: Findings suggested that feasibility and acceptability of online training were promoted by (a) topic relevant training for volunteers; (b) high engagement of volunteers to prevent attrition; (c) mentorship or leadership component. Challenges to online training included a high workload; time elapsed between training and its application; and client attitude toward volunteers. Future research on online volunteer training should consider how online delivery can be most effectively paced to support volunteers in completing training and the technical skills needed to complete the training and whether teaching these skills can be integrated into programs.

Our review synthesized evidence on web-based training programs for volunteers who deliver services to older adults. This practical research topic is a public health issue, with sparse literature linking knowledge at the volunteer, training program, and older adult levels. While there is abundant knowledge of the broader topics of volunteerism, our review of online training provides timely knowledge relevant to the current pandemic circumstances (and the post-pandemic reality). In addition to the unique structure of the research topic, this evidence synthesis provides a practical foundation for transitioning volunteer training online, or for strengthening existing online training programs. Knowledge garnered from this synthesis could help community-based organizations in program delivery and design consider how online delivery can be most effectively placed to increase volunteer access to training.

Population projections suggest that globally the number of individuals 65 years and over will more than double by 2050 (1). Accompanying global population aging is a rise in chronic and degenerative diseases. These demographic changes are met with increased demand for healthcare supports and services (1). Volunteer programs that offer services to older persons can assist them in accessing healthcare in an efficient and effective manner. Multiple studies have shown positive patient outcomes of volunteers providing in-home services for dementia care [e.g., (2)], support with mobilization in nursing homes (3) and educational health-promoting sessions in the community (4–7).

Older persons are often appropriate recipients of the public health approach to palliative care, that takes an upstream community-based approach to palliative care, by identifying and supporting individuals early in their trajectory toward end of life with the goal of enhancing their quality of life, symptom management, and mental health (8–10). The public health approach to palliative care entails the integration of a broad group of stakeholders who can be mobilized to support community-living individuals as they deal with serious illnesses (11, 12). Community-based initiatives that train volunteers to support patients with advancing illness is an important component to implementing the public health approach to palliative care (3, 13). As part of implementing an effective community-based volunteer-based program volunteers need to be sufficiently trained.

Although relatively new, online volunteer training has emerged as an effective and feasible way to educate a large group of volunteers in a timely manner (14, 15). As opposed to in-person training, online training addresses the barriers of time, accessibility, and cost. Online training could provide a more accessible learning environment without compromising the integrity of the training. Frendo (15) analyzed three different modes of delivery for volunteer training (online vs. face-to- face vs. blended) and found that although face-to-face training was highly regarded in creating connections with other volunteers, online training met volunteers' motivational needs when opportunities were provided for learners to interact in real-time with people from a distance. The benefits to online volunteer training may outweigh the barriers. Although technical difficulties and limited interaction amongst participants can create barriers during training, this is offset by tangible benefits such as the ability to draw participants from a larger geographic region, provide flexible training times, and engage participants in cross cultural learning (14, 15). Given these benefits understanding how to provide acceptable and feasible online training is an important initial step.

Acceptability and feasibility are key considerations when implementing innovative programs, such as educational programs (16). While there is a notable absence of concrete definitions for acceptability in the context of online volunteer training (16), an innovation is often considered acceptable when its benefits are identifiable and/or it addresses previous systemic, social, or educational challenges (17). The intended users' reaction to the innovation is perhaps the ultimate test of acceptability. This is often assessed by indicators of satisfaction, intent to continue use, perceived appropriateness, and fit with the culture (18). Ensuring acceptability to recipients of a program and to those who deliver it is essential. It can impact whether the program is delivered as intended, and by extension whether there are positive outcomes for recipients (19, 20). Furthermore, gauging feasibility before launching a new program is essential for identifying and planning to address logistical challenges (17). Perhaps most importantly, assessing feasibility can help ensure the program is compatible with the available resources of those who intend to implement the training (21–25). Feasibility is an important aspect to measure given the limited resources most community- based organizations have available.

Sustainability is also a potential advantage of online training programs. Beyond online training providing a format that increases training capacity, it could also facilitate continuation of a community-based program in which education is an important component. If the training is acceptable and feasible to implement, organizations that transition in person training to online could realize benefits in terms of cost effectiveness and training quality. Online training could be an effective and safe way to provide education for volunteers in both initial training and/or continuing education throughout their involvement as a volunteer.

The aim of this review was to examine the feasibility and acceptability of community-based organizations adopting an online training format for their volunteers by synthesizing evidence from the research and gray literature on online training/coaching/mentoring programs for volunteers delivering services to older persons. This review intends to examine factors that facilitate, or hinder, an organization successfully implementing online training. These factors will provide a basis for recommendations for adopting online training and a foundation for future research. For instance, identifying barriers to feasible and acceptable online training programs for volunteers can help organizations identify potential issues when designing programs so they can address them early in the development phase. Likewise, understanding factors that facilitate feasibility and acceptability can help them maximize factors that can lead to successful adoption. Ultimately, we hope this review will inform future online volunteer training efforts to support older adults in the community.

The research question directing this integrative review is:

How feasible and acceptable is it for community-based organizations supporting older adults to adopt an online training format for their volunteers?

Two sub-questions are:

What are the barriers to feasible and acceptable online training for volunteers who support older adults in the community?

What are the facilitators of feasible and acceptable online training for volunteers who support older adults in the community?

To answer the research question, an integrated review was conducted to synthesize evidence from the research and gray literature on online training/coaching/mentoring programs for volunteers who deliver services to older persons. An integrative review is an umbrella term used to describe a synthesis method for integrating qualitative and quantitative data, such as mixed studies reviews and critical interpretive synthesis (26). These types of reviews provide a comprehensive overview of a subject area to inform a specific problem.

This review will aid in understanding how the online training programs were conducted and the perspectives of training participants and organizational administrators on acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness. Two methods were used for the review: (A) a database search of the existing research literature, and (B) an online search of existing online volunteer training programs currently being delivered in Canada. The methods are described for the database searches and online search strategy separately. The database search of existing research literature was broadly set to training for volunteers supporting adults. The intent of the online search of existing volunteer training programs was to identify programs that offer training for volunteers supporting older adults.

In collaboration with a librarian a search strategy was developed using the key concepts of volunteer training, navigation, mentoring, coaching, online, virtual. The database search was conducted on MEDLINE (ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), EMBASE (Elsevier), PsycInfo (EBSCO), Embase (Elsevier), Social work abstracts (EBSCO), ERIC (ProQuest). The search was completed in June 2020. Search results are in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA Review flow diagram for all search strategies broken down to the two separate search strategies, (1) Database Search and (2) Online Training Programs.

To be included, studies: (a) written in English, (b) focused on adults being trained to provide support to adults in an unpaid setting, (c) part of an intervention that utilized online training modules or coaching/mentoring programs, (d) either theoretical (e.g., best practices for designing and delivering training), empirical (e.g., protocol, evaluation), gray literature (e.g., online organizations providing training), or reviews, and (e) described outcomes such as perspectives of training participants, feasibility, acceptability, or effectiveness of training. Studies were excluded if they had student, university, school, pedagogy, classroom, or undergraduate in the title.

Once the search was completed records were downloaded into a reference management (Mendeley) software to identify duplicate records, then transferred into Covidence, an online tool used for organizing and expediting systematic reviews (27). Three reviewers scanned the same 50 articles to validate the inclusion process then met to review their results. The fourth reviewer was added later and trained independently by one of the original reviewers. There were two stages to the review process. The title and abstract phase focused on identifying articles that reflected key study concepts and the full text stage explored whether key concepts are operationalized in a way that could address the research question.

The team of four research members independently scanned the title, abstract, or both sections of every record retrieved, with at least two reviewers per article. Potentially relevant papers were retrieved in full and their citation details imported into the Covidence software. Next, two independent reviewers assessed the full text of selected articles in detail against the inclusion criteria. When there were disagreements on inclusion/ exclusion, the two reviewers discussed the articles to determine whether the article should be included. In addition, reference lists in the included articles were reviewed to identify additional relevant literature.

A 2020 PRISMA flow chart was created as a visual summary of the number of records identified through database searching and other sources, as well as the number of records included and excluded (http://www.prisma-statement.org). Data was extracted using Covidence and pre-coded data extraction categories, see Appendix for detailed template.

Canadian websites were scanned to identify and extract data on online volunteer training programs specific to older adults. Two separate search methods were used for the initial online program search. For the primary search a Google search was conducted to identify organizations focused on end-of-life care in Canada using the quality of end-of-life coalition as a beginning point. This search was able to identify provincial and territorial hospice societies. The following steps were completed:

1. Starting with the End-of-life coalition (https://www.chpca.ca/projects/the-quality-end-of-life-care-coalition-of-canada/) all organizations listed on the website were explored.

2. Each provincial and territorial hospice associations' websites were explored to identify specific lists of hospices within each area.

3. The website: http://www.canadian-universities.net/Volunteer/Seniors.html was investigated to volunteer opportunities by “Seniors.” All suggested organizations were investigated, those without a website and were excluded.

4. All the links in each province listed on the following website: https://volunteer.ca/index.php?MenuItemID=422 were identified and each website was filtered by the option indicating virtual or by distance.

In the second Google search a search of organizations focused on older adults was added, the search strategy utilized a combination of key words, this was followed by removing one word/phrase at a time. The key words were: “older persons” OR seniors OR elderly; Hospice OR palliative OR “end of life”; Volunteer; Training OR online OR resources OR education; Community OR care OR support; and Canada. The first 10 Google pages were searched for each possible word combination to identify and scan potential websites to make sure it was specific to older persons. Then, the website was explored to identify whether there was volunteer training and if it was online. This search resulted in 10 possible programs, two of these programs had already been identified in the primary search, eight possible programs were added to the database.

Furthermore, volunteer.ca, a Pan-Canadian Volunteer Matching Platform was searched using the criteria of any location in Canada, volunteering as an individual on an ongoing basis, and serving seniors. Separate searches were conducted for each age group of volunteers (i.e., 19–25, 26–35, 36–55, 56–70, 71+); no new programs were identified.

When appropriate websites were located the following data were extracted: name of organization; mission/aim/focus of organization (i.e., provide meals on wheels); scope of organization; volunteer characteristics and responsibilities; and description of the volunteer training program (e.g., name, length/frequency; materials, content, additions to training); evaluations. The extracted data was organized using Excel.

Evidence from the research and gray literature on online training/coaching/mentoring programs for volunteers who deliver services to older persons was synthesized. Data analysis was completed in five phases: data reduction, data display, data comparison, conclusion drawing, and verification (26). For data reduction, a classification system was developed to cluster similar categories of data, this data was entered into a table (Appendix) to display the results of data reduction and facilitate data comparison. An approach similar to thematic analysis was used to identify commonalities, contrasts, and other relationships within the data table through an iterative process (28). The results of the data comparison and verification phases is both a narrative of the findings and a display of the data using tables to expand interpretations. Information on online programs for training volunteers was assessed for the presence of the barriers and facilitators found in the literature.

In order to effectively assess the level of evidence we chose an appraisal classification system that had separate classifications for both qualitative and quantitative studies and did not privilege quantitative over qualitative studies, Tomlin and Borgetto's (29) research pyramid. This pyramid breaks down articles into 4 separate categories (descriptive, experimental, outcomes, and qualitative research) to evaluate the level of evidence of studies included from different study designs. Each category describes four levels of evidence that go from the most to least rigorous. Descriptive research is divided into (1) Systematic reviews of related descriptive studies, (2) Association, correlational studies, (3) Multiple- case studies (series), normative studies, descriptive surveys, (4) Individual case studies. Experimental research is divided into (1) Meta- analyses of related experimental studies, (2) Individual (blinded) randomized controlled trials, (3) Controlled clinical trials, (4) Single- subject studies, Outcomes research is divided into (1) Meta- analyses of related outcomes studies, (2) Pre-existing groups comparisons with covariate analysis, (3) Case- control studies; pre-existing groups comparisons, (4) One-group pre- post studies. Finally qualitative research is divided into (1) Meta- synthesis of related qualitative studies, (2) Group qualitative studies with more rigor (a, b, c), (3) Group qualitative studies with less rigor- (a) Prolonged engagement with participants, (b) Triangulation of data (multiple sources), (c) Confirmation of data analysis and interpretation (peer and member checking), (4) Qualitative studies with a single informant.

The database search of the existing research literature, and online search of existing online training programs identified 23 sources that provided data on 16 unique programs; two programs are reported in 4 separate sources (Health TAPESTRY & Project HEAL).

A database search of the existing literature identified 17 articles. The programs involved working with anyone from seniors, to cancer survivors and individuals struggling with fertility. Although using different pedagogical theories, and e-learning strategies, self-paced learning modules were used nine times whereas a mixture of self-paced and live was used twice. Programs were open to any volunteers with three having restrictions to be at least 18 years of age, and six having restrictions to demographic characteristics; namely, race (4), sex (2), sexuality (1). There were also programs that limited volunteers to those with prior experience (1) or previous personal experience with disease (4). Training topics ranged across all programs, seven covered communication tips, nine covered science behind disease, five discussed ethics and four discussed the role of the volunteer and four programs discussed the use of technology in their training. Article information reflected in Table 1 was used to assess the level or quality of evidence (29).

Tables 1, 2 present information from articles found in the database search; Table 1 presents information on the basics of each identified program, which includes populations targeted by the program, aims of project/study, role of volunteer etc. Table 2 presents information on the online training for these programs, including details of training, materials used, and topics covered as well as acceptability promoting factors and barriers to feasibility.

The following components of the training programs have been summarized below. For the purposes of this review, the literature search process was broken down into two separate search strategies that have been outlined in the methods section above: (A) Database search strategy and (B) Online training Program search strategy.

A summary of the extracted data from the included articles identified in the database search strategy is provided below, more detailed information is in Table 2. This summary is followed by an evaluation of the feasibility and acceptability of the programs described by the articles, this is organized by the themes: (1) feasibility-promoting factors; (2) barriers to feasibility; (3) acceptability-promoting factors; and (4) barriers to acceptability.

A summary of the online training programs search results is provided next. In addition, there is detailed information in the data extraction table (Table 3). The summary is followed by an assessment of feasibility and acceptability in the online training programs identified (for detailed information see Table 4).

Volunteer trainees filled many specific roles such as Peer Supporter (33, 37, 42), Peer Educator (47), Lay/Peer Leader (31, 40, 44), Volunteer Health Connector (31), Community Health Advisor (33, 35, 36), Consumer Health Information Center Volunteer (41), and Disaster Emergency Medical Personnel System Volunteer (46). Responsibilities included motivational interviewing over the telephone (37), visiting clients at home (30–32), or providing support to clients virtually (39, 43), all with the objective of contributing to the delivery of a health-promoting program [i.e., supportive environments that allow people and communities to adopt healthy behaviors; (48)] to adults in the community.

Due to our inclusion criteria, there was no exclusively live training for these roles. However, the online training was sometimes combined with simultaneous in-person (33, 36, 42) or hybrid (46) training to assess differences in implementation from delivery method. Training delivery was delivered equally between a multi-medium platform (e.g., live components and self-paced components) that enabled flexibility for training (34, 35, 38, 42, 46), and solely self-paced (31, 33, 36, 44, 45). When training was self-paced, materials included educational videos, quizzes, narrated PowerPoint slides, training manual; practice sessions with role playing; interactive discussions; and recorded webinars.

Nine peer-reviewed articles evaluated the implementation of their training program. The findings indicated that online training was largely feasible (N = 7/9). Only two studies reported that online training for their program was not feasible (38, 44), primarily due to recruitment and attrition of volunteers. Conte (44) reported feasibility was affected by a lack of volunteer sustainability resulting in poor uptake. Bachmann (38) concluded that the current structure and format of the training program was not feasible, due to problems with volunteer recruitment, a low completion rate (8%), and issues with volunteers' completion of every component of the intervention. Eight studies did not evaluate or explicitly report on feasibility. Acceptability was evaluated less frequently (N = 6) than feasibility, although all studies that evaluated acceptability reported positive results (30–32, 34, 43, 44). A majority of these studies were for the same training program (31, 33–36, 49).

Feasibility was assessed with process measures (31, 34), volunteer reflections (31), volunteers' understanding of their roles and responsibilities (31), client perspectives on the volunteer program (31), and cost effectiveness (30, 41, 43). Acceptability was measured through volunteer perceptions of ease of use (34, 44), ease of understanding (34, 44), acceptability of the workload or commitment (31, 34), and perceptions of effectiveness in volunteer role (30).

Information on accessibility and feasibility was organized into four themes (1) Feasibility Promoting Factors; (2) Barriers to Feasibility; (3) Acceptability Promoting Factors; and (4) Barriers to Acceptability.

Feasibility promoting factors were defined as factors that enable success of a program through compatibility with available resources (21–25) and included topic relevancy, preventing attrition/promoting engagement of volunteers, and a leadership/mentorship component.

Topic Relevancy. Topics were considered more relevant when program leads were consulted to aid in identifying online strategies and tools that fit their program (40). When content was designed based on trainee interest or gap in knowledge it helped maintain interest (30). Volunteers undergoing training were appreciative of relatable content that reflected situations they expected to find themselves in when applying their training (38). Volunteers liked the opportunity to contribute to future training designs by giving feedback (32, 41), which helped with successful training (39).

Preventing Attrition/Promoting Engagement. Instructor engagement, such as enthusiasm and endorsement of the overall program or program content helped volunteers stay motivated and commit to the workload (38). Diversity in training methods (e.g., online, role play, in-person, written manual) was appreciated by volunteer trainees for maintaining interest (31). In one intervention, TAPESTRY (31, 49), previous experience with online training (such as being in the second year of program implementation) increased odds of successful training completion (44). Having an interactive, participatory component [e.g., interaction or role play with others or having discussion board; (30, 32, 39, 43)] helped volunteers remain engaged.

Leadership/Mentorship Component. A mentorship or leadership component [e.g., a champion of the program or an experienced volunteer mentoring an incoming volunteer; (31, 44)] promoted volunteers' participation in training.

A common barrier to feasibility was perceived lack of consideration for varying levels of technical literacy or computer skills (41, 44, 45). For instance, technical difficulties with the online platform meant that videos or other content loaded slowly and that the structure of the online program was overly complex (38, 43–45). The in-person design may not have been adapted sufficiently for online delivery (38).

Acceptability promoting factors enable benefits that are identifiable and/or address systemic, social, or educational challenges. Acceptability promoting factors included ease of use/simplicity, quality of interaction and volunteers perception of effectiveness (see Table 2).

Ease of Use/Simplicity. The online platform was simple and easy to navigate (41), and was accessible on different platforms [e.g., iOs, Android, computer; (35)]. A comfortable pace of teaching helped facilitate learning (38, 39). Using multiple mediums to convey information during training and using short, digestible videos were helpful to volunteers (38).

Quality of Interaction. Volunteers liked the use of social media for interaction between volunteers, such as role play (39) with client simulation scenarios (32). Involvement in online discussion with clients was a welcome interaction (43). Volunteer trainees were paired with an experienced volunteer (32), such as a “clinician champion” (30).

Volunteers Perception of Effectiveness. Volunteers in the TAPESTRY program (31) understood themselves as healthcare system connectors, feeling fulfilled with their contributions and learning new skills. They recognized their own utility and felt their involvement was positive and reported that volunteering improved their own health (31). The TAPESTRY volunteers also gained knowledge, self-efficacy and skills from their training, which received largely positive evaluation (31).

Some volunteers thought the demand of the volunteer role was too high for an unpaid role given their health education background (44) and that too much time elapsed between training and application of training (32). Some volunteers felt clients had complex needs that they could not address sufficiently and that not all clients or recipients were amenable to volunteer support (31), indicating that some perception of insufficient training exists among volunteers trained online. Conte et al. (44) also determined that those without a health education background typically sought out more resources than what was given to them.

The integrative review was complemented by a search of existing online training programs in Canada. The details on inclusion/ exclusion of programs are shown in Figure 1. Programs were excluded when they were a hub for other satellite programs that offered the training, training was actually offered in-person, or the program was not for volunteers. Tables 3, 4 present information from articles found in the existing online training programs search. Table 3 specifically highlights the aim of the programs and Table 4 presents details of online training delivery for each program.

Given the six online training programs, all but one used video(s) as a means to convey educational content to the volunteers. The training video(s) were typically one single video (50–52), some within a one-module training sessions (50, 51) or as part of a modular training design (52), while two programs offered a series of short videos (53, 54). On-going training and support were offered in two programs (52, 54) beyond the initial training session. All program training was designed for self-paced learning except for one (54), which, depending on the specialization (e.g., therapist volunteer vs. general volunteer), could include up to 35 h of training with some live group sessions. Due to the self-paced nature, most programs offered resources to enhance learning, such as a volunteer handbook (52, 55) or the module information in printable format (51, 52). One program (53) quizzed trainees following the educational videos and offered online discussion boards for volunteer interaction.

Based on the literature (see Table 4), we know that feasibility-promoting factors are topic relevancy (30, 32, 39–41), volunteer engagement/low attrition (31, 38, 49), and inclusion of a leadership/mentorship component (31, 44). The primary barrier to feasibility was with technology, specifically, having varying levels of computer skills across volunteers or having issues with delivering training components such as uploading videos (38, 41, 43–45). Acceptability-promoting factors are ease of use (35, 38, 39, 41), interaction quality (30, 32, 39, 43), and feeling effective (31). Barriers to acceptability were feelings of: (a) the volunteer workload being too high for an unpaid role (44), (b) too much time elapsing between training and application of the training (32), and (c) that clients had complex needs that volunteer support could not sufficiently address (31).

Based on our review of the six pre-existing online programs, none showed all three feasibility promoting factors identified from the literature (i.e., topic relevancy, volunteer low attrition/high engagement, leadership/mentorship component) and five showed some barriers to feasibility identified from the literature (i.e., technology challenges/complex training schedule, computer skills). Two programs (Circle of Care; Yeehong Center for Geriatric Care) lacked the information necessary to assess the presence of feasibility promoting factors and seven programs lacked the information necessary to assess the presence of acceptability promoting factors. Two programs (Senior Connect; Health TAPESTRY) showed two factors that promote feasibility; both programs included relevant, varied content, one included a commitment requirement (preventing attrition), and one included a volunteer-peer (i.e., a fellow volunteer who progressed through training as a peer learner). Four programs reported technology challenges that impeded acceptability (38, 43–45).

The aim of this review was to examine the feasibility and acceptability of community-based organizations adopting an online training format for their volunteers by synthesizing evidence from the research and gray literature on online training/coaching/mentoring programs for volunteers delivering services to adults. In particular, we wanted to identify facilitators and barriers to feasible and acceptable online training for volunteers who support older adults in the community.

From the literature, we learned that online volunteer training programs factors promoting feasibility and acceptability were (a) topic relevancy of training (31, 38, 49); (b) an interactive, participatory component to training [e.g., interaction or role play with others, having discussion board; (30, 32, 39, 43)]; and (c)mentorship or leadership [e.g., having a champion of the program, or having an experienced volunteer mentor incoming volunteers; (31, 44)]. Major challenges to successful transition to online training included: (a) poor technology and software performance (38, 41, 43–45) or that was difficult to learn and use (35, 38, 39, 41); (b) poor or no interaction (30, 32, 39, 43); and (c) perceptions of ineffectiveness or overwhelming workload (31).

The online programs reviewed showed little adherence to the evidence from our database search of training methods for online delivery. For example, feasibility is promoted when the online training structure requires high engagement from the volunteers (31, 38, 49), but programs' educational materials were typically a single video (50–52) within a one-module training session (50, 51) or as part of a multi-module training design (52). Further, on-going training and support were offered in only two programs (52, 54) beyond the initial training session, all program training was designed for self-paced learning except for one program (54), and only one program (53) assessed volunteers' knowledge of the material or offered online discussion boards for volunteer interaction.

Acceptability may be enhanced by improving interaction quality (30, 32, 39, 43) and volunteers feeling effective in their support role (31). Few online programs implemented sustained teaching methods (e.g., follow-up training or support, online discussion boards). In fact, a barrier to acceptability was volunteers feeling clients had complex needs which volunteer support could not sufficiently address (31). Systematic support and follow-up training would be beneficial for promoting volunteers' self-efficacy, as feasibility is promoted when volunteers feel effective in their supportive role.

Although topic relevancy of the training was identified as a major contributor to feasibility in our database search (30, 32, 39–41), only two programs offered thematic or topic-specific videos (53, 54). Additional identified technological barriers to feasibility were addressing the varying levels of computer skills across volunteers or having issues with delivering training components such as uploading videos (38, 41, 43–45). Most programs attempted to address this by offering resources that enhanced the online training, such as providing a volunteer handbook (52, 55) and educational materials in printable format (51, 52). For example, supplemental materials such as a volunteer handbook or educational materials can provide additional support to volunteers who have low computer skills.

None of the online programs reviewed exhibited all three feasibility promoting factors identified from the literature (i.e., topic relevancy, low attrition and high engagement, leadership component), although two programs (51, 52) lacked the information necessary to assess them.

There is evidence that feasibility is promoted when topic relevancy (30, 32, 39–41) increases volunteer engagement and participation (31, 38, 49) and includes a leadership/mentorship component (31, 44). Additionally, there is evidence that online training acceptability is promoted when the technology and software (38, 41, 43–45) are easy to use (35, 38, 39, 41), enables quality interactions (30, 32, 39, 43), and perceptions of effectiveness (31) are obtained through testing volunteers' knowledge gained following training (e.g., module quizzes).

This review was limited by the search strategy. Our search strategy was developed to identify existing online training programs that were applicable to older persons and peer-reviewed evidence on online training programs applicable to all adults, thus our conclusion is based on evidence garnered from a two slightly different demographic profiles. As our inclusion criteria selected only English-written articles, the evidence synthesized in this review is limited to English speaking regions. None of the online programs reviewed showed evidence of any evaluation of acceptability and feasibility, suggesting that there has been no formal evaluation done on these programs. Thus, our ability to identify feasibility and acceptability promoting or impeding factors in these programs was limited to our interpretations of the available materials. All of the articles reviewed in the database search were based on the researchers' perspectives, resulting in a lack of perspectives from volunteer trainees themselves. This limited our assessment of acceptability, as acceptability is optimally defined and measured by end-users' experience with the training program. A majority of the articles from the peer-reviewed literature were for the same training program. This may skew our findings toward those programs, in that counting programs more than once could bias the identified themes toward those programs and minimize the impact of the remaining programs. For example, a program that is counted more than once may exhibit specific feasibility and acceptability factors that are not present in another program, but are counted as being “frequently reported” due to the program being counted more than once. This bias is due to the lack of published evaluations of online training programs. To reduce this bias there needs to be more evaluation research on volunteer training programs. Programs need to assess and report their evaluations of feasibility and acceptability to enable appropriate design and implementation of online training programs. It would also be beneficial for researchers to publish the program protocol and evaluation. This would facilitate a more thorough assessment of feasibility and acceptability that begins with program design and planning. Finally a synthesis of online training for volunteers providing supports to other populations would improve generalizability.

Our synthesis supports the conclusion that online volunteer training is feasible and acceptable for community-based organizations that support adults, particularly if facilitators of feasibility are present. There is evidence that feasibility is facilitated when topic relevancy promotes engagement/low attrition and includes a leadership/mentorship component. Additionally, there is evidence that acceptability is facilitated when there is sound technology and software that is easy to use and enables interaction quality and perceptions of effectiveness. Based on our review of the pre-existing online programs, none of the programs showed all three feasibility promoting factors identified from the literature. Although it may be feasible and acceptable for community-based organizations to adopt an online training format for their volunteers, the online programs reviewed showed little adherence to the evidence from our database search of training methods for online delivery.

BP, WD, and GW conceived the study and secured its funding. TH, JL, EK, and GW screened articles and analyzed data. TH, JL, EK, BP, WD, and GW contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research [#148655] and the Canadian Cancer Research Institute [#704887].

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects 2019 Highlights (2019).

2. Dröes RM, van Rijn A, Rus E, Dacier S, Meiland F. Utilization, effect, and benefit of the individualized meeting centers support program for people with dementia and caregivers. Clin Intervent Aging. (2019) 14:1527–53. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S212852

3. Baczynska AM, Lim SE, Sayer AA, Roberts HC. The use of volunteers to help older medical patients mobilise in hospital: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. (2016) 25:3102–12. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13317

4. Barlow JH, Wright CC, Turner AP, Bancroft GV. A 12-month follow-up study of self-management training for people with chronic disease: are changes maintained over time? Br J Health Psychol. (2005) 10:589–99. doi: 10.1348/135910705X26317

5. Battersby M, Harris M, Smith D, Reed R, Woodman R. A pragmatic randomized controlled trial of the Flinders Program of chronic condition management in community health care services. Patient Educ Counsel. (2015) 98:1367–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.003

6. Foster G, Taylor SJC, Eldridge SE, Ramsay J, Griffiths CJ. Self-management education programmes by lay leaders for people with chronic conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2007) 4:CD005108. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005108.pub2

7. Kennedy A, Reeves D, Bower P, Lee V, Middleton E, Richardson G, et al. The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a national lay-led self-care support programme for patients with long-term conditions: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2007) 61:254–61. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053538

8. Bacon J. The Palliative Approach: Improving care for Canadians With life-Limiting Illnesses - Google Search (Discussion Paper) (2012). Available online at: http://hpcintegration.ca/media/38753/TWF-palliative-approach-report-English-final2.pdf (accessed December 03, 2020).

9. Baker A, Leak P, Ritchie LD, Lee AJ, Fielding S. Anticipatory care planning and integration: a primary care pilot study aimed at reducing unplanned hospitalisation. Br J General Pract. (2012) 62:e113–20. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X625175

10. Stajduhar KI, Tayler C. Taking an “upstream” approach in the care of dying cancer patients: the case for a palliative approach. Canad Oncol Nurs J. (2014) 24:144–53. doi: 10.5737/1181912x241144148

11. Kellehear A, O'Connor D. Health-promoting palliative care: a practice example. Critic Public Health. (2008) 18:111–5. doi: 10.1080/09581590701848960

12. Sallnow L, Richardson H, Murray S, Kellehear A. Understanding the impact of a new public health approach to end-of-life care: a qualitative study of a community led intervention. Lancet. (2017) 389:S88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30484-1

13. Sales VL, Ashraf MS, Lella LK, Huang J, Bhumireddy G, Lefkowitz L, et al. Utilization of trained volunteers decreases 30-day readmissions for heart failure. J Cardiac Failure. (2013) 19:842–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.10.008

14. Ballew P, Castro S, Claus J, Kittur N, Brennan L, Brownson RC. Developing online training for public health practitioners: what can we learn from a review of five disciplines? Health Educ Res. (2013) 28:276–87. doi: 10.1093/her/cys098

15. Frendo M. Exploring the Impact of Online Training Design on Volunteer Motivation and Intention to Act [Michigan State University]. (2017). Available online at: https://d.lib.msu.edu/etd/4829 (accessed March 11, 2021).

16. Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res. (2017) 17:88. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

17. Mendenhall E, De Silva MJ, Hanlon C, Petersen I, Shidhaye R, Jordans M, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of using non-specialist health workers to deliver mental health care: stakeholder perceptions from the PRIME district sites in Ethiopia, India, Nepal, South Africa, and Uganda. Soc Sci Med. (2014) 118:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.057

18. Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, Cofta-Woerpel L, Linnan L, Weiner D, et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prevent Med. (2009) 36:452–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002

19. Borrelli B, Sepinwall D, Bellg AJ, Breger R, DeFrancesco C, Sharp DL, et al. A new tool to assess treatment fidelity and evaluation of treatment fidelity across 10 years of health behavior research. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2005) 73:852–60. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.852

20. Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Baumann AA, Mittman BS, Aarons GA, Brownson RC, et al. The implementation research institute: training mental health implementation researchers in the United States. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:105. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-105

21. Bueno M, Stevens B, Rao M, Riahi S, Lanese A, Li S. Usability, acceptability, and feasibility of the implementation of Infant Pain Practice Change (ImPaC) resource. Pediatric Neonatal Pain. (2020) 2:82–92. doi: 10.1002/pne2.12027

22. Gaffikin L, Blumenthal PD, Emerso M, Limpaphayom K, Lumbiganon P, Ringers P, et al. Safety, acceptability, and feasibility of a single-visit approach to cervical-cancer prevention in rural Thailand: a demonstration project. Lancet. (2003) 361:814–20. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12707-9

23. Nam J, Dempsey N. Understanding stakeholder perceptions of acceptability and feasibility of formal and informal planting in Sheffield's district parks. Sustainability. (2019) 11:360. doi: 10.3390/su11020360

24. Northridge ME, Metcalf SS, Yi S, Zhang Q, Gu X, Trinh-Shevrin C, et al. A protocol for a feasibility and acceptability study of a participatory, multi-level, dynamic intervention in urban outreach centers to improve the oral health of low-income Chinese Americans. Front Public Health. (2018) 6:29. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00029

25. Palmer RT, Biagioli FE, Mujcic J, Schneider BN, Spires L, Dodson LG. The feasibility and acceptability of administering a telemedicine objective structured clinical exam as a solution for providing equivalent education to remote and rural learners. Rural Remote Health. (2015) 15:3399. doi: 10.22605/RRH3399

26. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. (2005) 52:546–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

27. Covidence (2021). Available online at: https://www.covidence.org/reviews/active (accessed March 11, 2020).

29. Tomlin G, Borgetto B. Research pyramid: a new evidence-based practice model for occupational therapy. Am J Occupat Therapy. (2011) 65:189–96. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2011.000828

30. Oliver D, Dolovich L, Lamarche L, Gaber J, Avilla E, Bhamani M, et al. A volunteer program to connect primary care and the home to support the health of older adults: a community case study. Front Med. (2018) 5:48. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00048

31. Dolovich L, Gaber J, Valaitis R, Ploeg J, Oliver D, Richardson J, et al. Exploration of volunteers as health connectors within a multicomponent primary care-based program supporting self-management of diabetes and hypertension. Health Soc Care Commun. (2020) 28:734–46. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12904

32. Gaber J, Oliver D, Valaitis R, Cleghorn L, Lamarche L, Avilla E, et al. Experiences of integrating community volunteers as extensions of the primary care team to help support older adults at home: a qualitative study. BMC Family Practice. (2020) 21:92. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-01165-2

33. Holt CL, Tagai EK, Scheirer MA, Santos SLZ, Bowie J, Haider M, et al. Translating evidence-based interventions for implementation: experiences from Project HEAL in African American churches. Implement Sci. (2014) 9:66. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-66

34. Santos SLZ, Tagai EK, Qi Wang M, Ann Scheirer M, Slade JL, Holt CL. Feasibility of a web-based training system for peer community health advisors in cancer early detection among African Americans. Am J Public Health. (2014) 104:2282–89. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302237

35. Santos SLZ, Tagai EK, Scheirer MA, Bowie J, Haider M, Slade J, et al. Adoption, reach, and implementation of a cancer education intervention in African American churches. Implement Sci. (2017) 12:36. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0566-z

36. Holt CL, Tagai EK, Santos SLZ, Scheirer MA, Bowie J, Haider M, et al. Web-based versus in-person methods for training lay community health advisors to implement health promotion workshops: participant outcomes from a cluster-randomized trial. Transl Behav Med. (2019) 9:573–82. doi: 10.1093/tbm/iby065

37. Abeypala U, Chalmers L, Trute M. Connect2: a motivational peer support model for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. (2014) 106:S24–5.

38. Bachmann MA. Implementation and Evaluation of an online Peer Education Training Program for Improved Self-Management of Diabetes Among African American Community Members: Implications of a Feasibility Study. thesis submitted to Columbia University, New York City, NY, United States (2010).

39. Jaganath D, Gill HK, Cohen AC, Young SD. Harnessing online peer education (HOPE): Integrating C-POL and social media to train peer leaders in HIV prevention. AIDS Care. (2012) 24:593–600. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.630355

40. Renfro T, Johnson E, Lambert DN, Wingood G, Diclemente RJ. The MEDIA model: an innovative method for digitizing and training community members to facilitate an HIV prevention intervention. Transl Behav Med. (2018) 8:815–23. doi: 10.1093/tbm/iby012

41. McGraw KA, Jenks-Brown AR. Creating an online tutorial for consumer health information center volunteers. J Hosp Librarianship. (2008) 5:55–63. doi: 10.1300/J186v05n03_05

42. Etherington N, Baker L, Ham M, Glasbeek D. Evaluating the effectiveness of online training for a comprehensive violence against women program: a pilot study. J Interpersonal Violence. (2017). doi: 10.1177/0886260517725734

43. Grunberg PH, Dennis CL, Da Costa D, Gagné K, Idelson R, Zelkowitz P. Development and evaluation of an online infertility peer supporter training program. Patient Educ Counsel. (2020) 103:1005–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.11.019

44. Conte KP, Held F, Pipitone O, Bowman S. The feasibility of recruiting and training lay leaders during real-world program delivery and scale-up: the case of walk with ease. Health Promot Practice. (2019) 22:91–101. doi: 10.1177/1524839919840004

45. Hattink B, Meiland F, Van Der Roest H, Kevern P, Abiuso F, Bengtsson J, et al. Online STAR E-learning course increases empathy and understanding in dementia caregivers: results from a randomized controlled trial in the netherlands and the United Kingdom. J Med Internet Res. (2015). 17:e241. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4025

46. Schmitz S, Radcliff TA, Chu K, Smith RE, Dobalian A. Veterans Health Administration's Disaster Emergency Medical Personnel System (DEMPS) Training evaluation: potential implications for disaster health care volunteers. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2018) 12:744–51. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2018.6

47. Bachmann MR. Implementation and Evaluation of a Web-Based Peer Education Training Program for Improved self-Management of Diabetes Among African American Community Members: Implications of a Feasibility Study. Vol. 71. ProQuest Information and Learning. (2011). p. 4298.

48. Potvin L, Jones CM. Twenty-five years after the Ottawa Charter: The critical role of health promotion for public health. Canad J Public Health. (2011) 102:244–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03404041

49. Dolovich L, Oliver D, Lamarche L, Agarwal G, Carr T, Chan D, et al. A protocol for a pragmatic randomized controlled trial using the Health Teams Advancing Patient Experience: Strengthening Quality (Health TAPESTRY) platform approach to promote person-focused primary healthcare for older adults. Implement Sci. (2016) 11:49. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0407-5

50. Calgary Seniors' Resource Society. Senior Connect Calgary. (2021). Retrieved from: https://www.seniorconnectcalgary.org/ (accessed March 13, 2021).

51. Sinai Health. Friendly Visiting - Circle of Care. (2021). Retrieved from: https://www.circleofcare.com/friendly-visiting/ (accessed March 13, 2021).

52. Yee Hong Centre for Geriatric Care. Friendly Visiting - Yee Hong. (2021). Retrieved from: https://www.yeehong.com/centre/community-services/friendly-visiting/ (accessed March 13, 2021).

53. Health TAPESTRY. Volunteers – Heath Tapestry. (2021). Retrieved from: https://healthtapestry.ca/index.php/volunteers/ (accessed March 13, 2021).

54. Hospice Toronto. Volunteers - Hospice Toronto. (2021). Retrieved from: https://hospicetoronto.ca/volunteers/ (accessed March 13, 2021).

55. Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. Hospice Palliative Care Volunteers: A Training Program - Online Version. (2021). Retrieved from: https://www.chpca.ca/product/hospice-palliative-care-volunteers-a-training-program-online-version/ (accessed March 13, 2021).

Keywords: volunteers, online training, older adults, community support, program implementation

Citation: Hill TG, Langley JE, Kervin EK, Pesut B, Duggleby W and Warner G (2021) An Integrative Review on the Feasibility and Acceptability of Delivering an Online Training and Mentoring Module to Volunteers Working in Community Organizations. Front. Digit. Health 3:688982. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2021.688982

Received: 18 May 2021; Accepted: 09 September 2021;

Published: 14 October 2021.

Edited by:

Pradeep Nair, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, IndiaReviewed by:

Patrick Lander, Eastern Institute of Technology, New ZealandCopyright © 2021 Hill, Langley, Kervin, Pesut, Duggleby and Warner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Taylor G. Hill, dGF5bG9yLmhpbGxAZGFsLmNh

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.