- 1Department of Statistics and Actuarial Science, College of Mathematics and Statistics, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China

- 2Chongqing Key Laboratory of Analytic Mathematics and Applications, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China

For the normal model with a known mean, the Bayes estimation of the variance parameter under the conjugate prior is studied in Lehmann and Casella (1998) and Mao and Tang (2012). However, they only calculate the Bayes estimator with respect to a conjugate prior under the squared error loss function. Zhang (2017) calculates the Bayes estimator of the variance parameter of the normal model with a known mean with respect to the conjugate prior under Stein’s loss function which penalizes gross overestimation and gross underestimation equally, and the corresponding Posterior Expected Stein’s Loss (PESL). Motivated by their works, we have calculated the Bayes estimators of the variance parameter with respect to the noninformative (Jeffreys’s, reference, and matching) priors under Stein’s loss function, and the corresponding PESLs. Moreover, we have calculated the Bayes estimators of the scale parameter with respect to the conjugate and noninformative priors under Stein’s loss function, and the corresponding PESLs. The quantities (prior, posterior, three posterior expectations, two Bayes estimators, and two PESLs) and expressions of the variance and scale parameters of the model for the conjugate and noninformative priors are summarized in two tables. After that, the numerical simulations are carried out to exemplify the theoretical findings. Finally, we calculate the Bayes estimators and the PESLs of the variance and scale parameters of the S&P 500 monthly simple returns for the conjugate and noninformative priors.

1 Introduction

There are four basic elements in Bayesian decision theory and specifically in Bayesian point estimation: The data, the model, the prior, and the loss function. In this paper, we are interested in the data from the normal model with a known mean, with respect to the conjugate and noninformative (Jeffreys’s, reference, and matching) priors, under Stein’s and the squared error loss functions. We will analytically calculate the Bayes estimators of the variance and scale parameters of the normal model with a known mean, with respect to the conjugate and noninformative priors under Stein’s and the squared error loss functions.

The squared error loss function has been used by many authors for the problem of estimating the variance, σ2, based on a random sample from a normal distribution (see for instance (Maatta and Casella, 1990)). As pointed out by (Casella and Berger, 2002), the squared error loss function penalizes overestimation and underestimation equally, which is fine for the location parameter with parameter space

The motivation and contributions of our paper are summarized as follows. For the normal model with a known mean μ, the Bayes estimation of the variance parameter θ = σ2 under the conjugate prior which is an Inverse Gamma distribution is studied in Example 4.2.5 (p.236) of (Lehmann and Casella, 1998) and Example 1.3.5 (p.15) of (Mao and Tang, 2012). However, they only calculate the Bayes estimator with respect to a conjugate prior under the squared error loss. (Zhang, 2017) calculates the Bayes estimator of the variance parameter θ = σ2 of the normal model with a known mean with respect to the conjugate prior under Stein’s loss function which penalizes gross overestimation and gross underestimation equally, and the corresponding Posterior Expected Stein’s Loss (PESL). Motivated by the works of (Lehmann and Casella, 1998; Mao and Tang, 2012; Zhang, 2017), we want to calculate the Bayes estimators of the variance and scale parameters of the normal model with a known mean for the conjugate and noninformative priors under Stein’s loss function. The contributions of our paper are summarized as follows. In this paper, we have calculated the Bayes estimators of the variance parameter θ = σ2 with respect to the noninformative (Jeffreys’s, reference, and matching) priors under Stein’s loss function, and the corresponding Posterior Expected Stein’s Losses (PESLs). Moreover, we have calculated the Bayes estimators of the scale parameter θ = σ with respect to the conjugate and noninformative priors under Stein’s loss function, and the corresponding PESLs. For more literature on Bayesian estimation and inference, we refer readers to (Sindhu and Aslam, 2013a; Sindhu and Aslam, 2013b; Sindhu et al., 2013; Sindhu et al., 2016a; Sindhu et al., 2016b; Sindhu et al., 2016c; Sindhu et al., 2017; Sindhu et al., 2018; Sindhu and Hussain, 2018)

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In the next Section 2, we analytically calculate the Bayes estimators of the variance and scale parameters of the normal model with a known mean, with respect to the conjugate and noninformative priors under Stein’s loss function, and the corresponding PESLs. We also analytically calculate the Bayes estimators under the squared error loss function, and the corresponding PESLs. The quantities (prior, posterior, three posterior expectations, two Bayes estimators, and two PESLs) and expressions of the variance and scale parameters for the conjugate and noninformative priors are summarized in two tables. Section 3 reports vast amount of numerical simulation results of the combination of the noninformative prior and the scale parameter to support the theoretical studies of two inequalities of the Bayes estimators and the PESLs, and that the PESLs depend only on the number of observations, but do not depend on the mean and the sample. In Section 4, we calculate the Bayes estimators and the PESLs of the variance and scale parameters of the S&P 500 monthly simple returns for the conjugate and noninformative priors. Some conclusions and discussions are provided in Section 5.

2 Bayes Estimator, PESL, IRSL, and BRSL

In this section, we will analytically calculate the Bayes estimator

Suppose that we observe X1, X2, …, Xn from the hierarchical normal model with a mixing variance parameter θ = σ2:

where − ∞ < μ < ∞ is a known constant,

Alternatively, we may be interested in the scale parameter θ = σ. Motivated by the works of (Lehmann and Casella, 1998; Mao and Tang, 2012; Zhang, 2017), we also want to calculate the Bayes estimators of the scale parameter θ = σ with respect to the conjugate and noninformative priors under Stein’s loss function, and the corresponding PESLs. Suppose that we observe X1, X2, …, Xn from the hierarchical normal model with a mixing scale parameter θ = σ:

where − ∞ < μ < ∞ is a known constant,

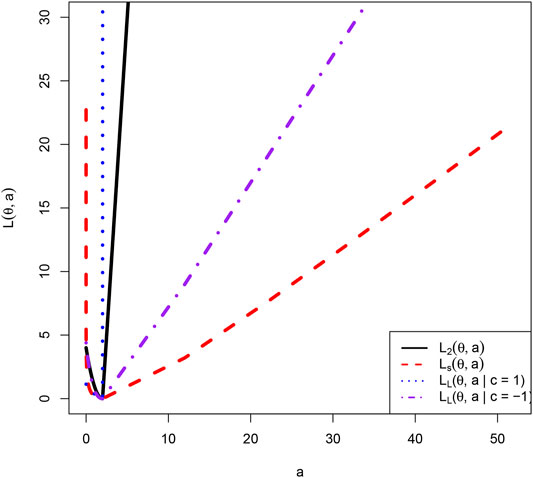

Now let us explain why we choose Stein’s loss function on

where θ > 0 is the unknown parameter of interest and a is an action or estimator. The squared error loss function is given by

The asymmetric Linear Exponential (LINEX) loss function ((Varian et al., 1975; Zellner, 1986; Robert, 2007)) is given by

where c ≠ 0 serving to determine its shape. In particular, when c > 0, the LINEX loss function tends to ∞ exponentially, while when c < 0, the LINEX loss function tends to ∞ linearly. Note that on the positive restricted parameter space

As pointed out by (Zhang, 2017), the Bayes estimator

minimizes the PESL, that is,

where

The usual Bayes estimator of θ is

whose proof exploits Jensen’s inequality and the proof can be found in (Zhang, 2017). Note that the inequality (Eq. 6) is a special inequality in (Zhang et al., 2018). As calculated in (Zhang, 2017), the PESL at

and the PESL at

As observed in (Zhang, 2017),

which is a direct consequence of the general methodology for finding a Bayes estimator or due to

2.1 Conjugate Prior

The problem of finding the Bayes estimator under a conjugate prior is a standard problem that is treated in almost every text on Mathematical Statistics.

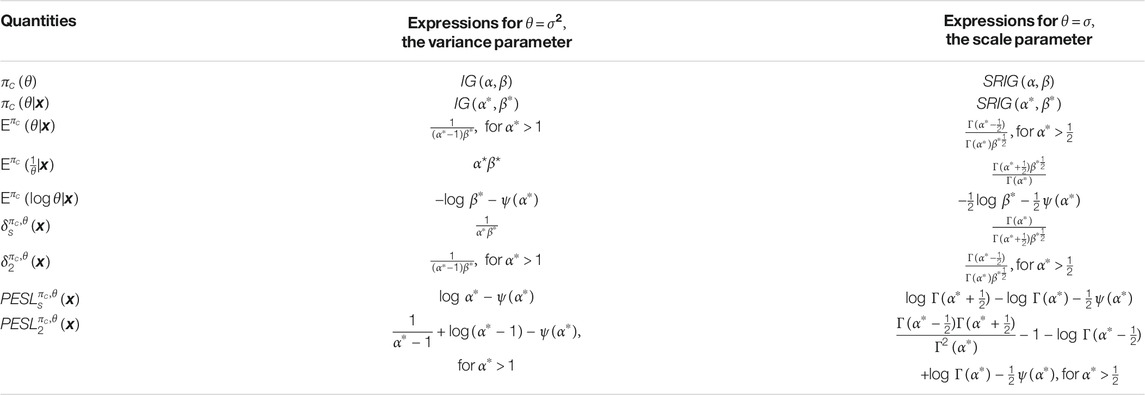

The quantities and expressions of the variance and scale parameters of the normal models (Eqs 1, 2) with a known mean μ for the conjugate prior are summarized in Table 1. In the table, α > 0 and β > 0 are known constants,

is the digamma function, and

2.2 Noninformative Priors

Famous noninformative priors include the Jeffreys’s ( (Jeffreys, 1961)), reference ( (Bernardo, 1979; Berger and Bernardo, 1992)), and matching ( (Tibshirani, 1989; Datta and Mukerjee, 2004)) priors. See also (Berger, 2006; Berger et al., 2015) and the references therein.

The Jeffreys’s noninformative prior for θ = σ2 is

See Part I (p.66) of (Chen, 2014), where μ is assumed known in the normal model

See Example 3.5.6 (p.131) of (Robert, 2007), where μ is assumed known in the normal model

Since μ is assumed known in the normal models, there is only one unknown parameter. Therefore, the reference prior is equal to the Jeffreys’s prior, and the matching prior is also equal to the Jeffreys’s prior (see pp.130–131 of (Ghosh et al., 2006)). In summary, when μ is assumed known in the normal models, the three noninformative priors equal, that is,

and

where

Note that as in many statistics textbooks, the probability density function (pdf) of

The conjugate prior of the scale parameter θ = σ is a Square Root of the Inverse Gamma (SRIG) distribution that we define below.

DEFINITION 1 Let

Definition 1 gives the definition of the SRIG distribution, which is the conjugate prior of the scale parameter θ = σ of the normal distribution. Because the SRIG distribution can not be found in standard textbooks, so we give its definition here. Moreover, Definition 1 is reasonable, since

We have the following proposition which gives the three expectations of the

PROPOSITION 1 Let

The relationship between the two distributions

PROPOSITION 2

THEOREM 1 Let

where

We have the following two remarks for Theorem 1.

Remark 1 Let θ = σ2. In the derivation of

where

then by Proposition 2,

Remark 2 The two posterior distributions in Theorem 1,

and

Note that

which is the reason why

2.2.1 The Quantities and Expressions of the Variance Parameter

In this subsubsection, we will calculate the expressions of the quantities (three posterior expectations, two Bayes estimators, and two PESLs) of the variance parameter θ = σ2.

Now we calculate the three expectations

From (Zhang, 2017), we know that

It is easy to see that, for

which exemplifies (Eq. 6). From (Zhang, 2017), we find that

and

It can be directly proved that

The IRSL at

since

is the marginal density of x with prior

2.2.2 The Quantities and Expressions of the Scale Parameter

In this subsubsection, we will calculate the expressions of the quantities (three posterior expectations, two Bayes estimators, and two PESLs) of the scale parameter θ = σ.

Now let us calculate

It can be proved that, for

which exemplifies (Eq. 6), and the proof which exploits the positivity of

Now we calculate

and the PESL at

Substituting (Eqs 10, 11, 12), into the above expressions, we obtain

for

for

The IRSL at

since

is the marginal density of x with prior

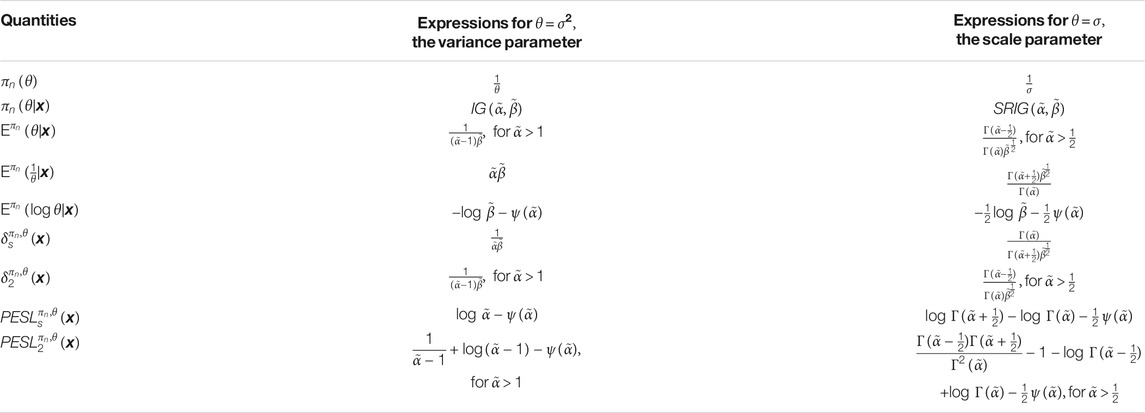

The quantities and expressions of the variance and scale parameters for the noninformative priors are summarized in Table 2. In the table,

From Tables 1, 2, we find that there are four combinations of the expressions of the quantities: conjugate prior and variance parameter, conjugate prior and scale parameter, noninformative prior and variance parameter, and noninformative prior and scale parameter. The forms of the expressions of the quantities are the same for the variance parameter under the conjugate and noninformative priors, since they have the same Inverse Gamma posterior distributions. Similarly, the forms of the expressions of the quantities are the same for the scale parameter under the conjugate and noninformative priors, since they have the same Square Root of the Inverse Gamma posterior distributions.

The inequalities (Eqs 6, 7) exist in Tables 1, 2. In fact, there are 8 inequalities in Tables 1, 2 and 4 inequalities in each table. Since the forms of the expressions of the quantities are the same in Tables 1, 2, with the only difference of the parameters, there are actually 4 different inequalities which are in Table 2. One inequality of the four inequalities about the Bayes estimators is obvious, and the proofs of the other three inequalities can be found in the Supplementary Material.

3 Numerical Simulations

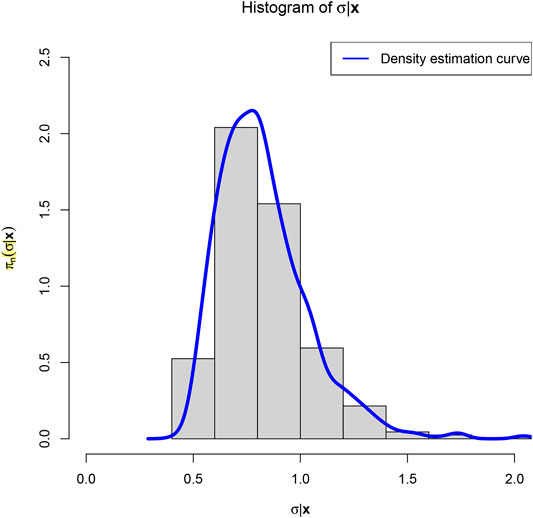

In this section, we will numerically exemplify the theoretical studies of (Eqs 6, 7), and that the PESLs depend only on n, but do not depend on μ and x. The numerical simulation results are similar for the four combinations of the expressions of the quantities, and thus we only present the results for the combination of the noninformative prior and the scale parameter.

First, we fix μ = 0 and n = 10, and assume that σ = 1 is drawn from the improper prior distribution. After that, we draw a random sample

from N(μ, σ2).

To generate a random sample

we will adopt the following algorithm. First, compute

Third, compute

Fourth, compute

Hence, σ is a random sample from the

The Bayes estimators (

Third, compute

Numerical results show that

and

which exemplify the theoretical studies of (6) and (7).

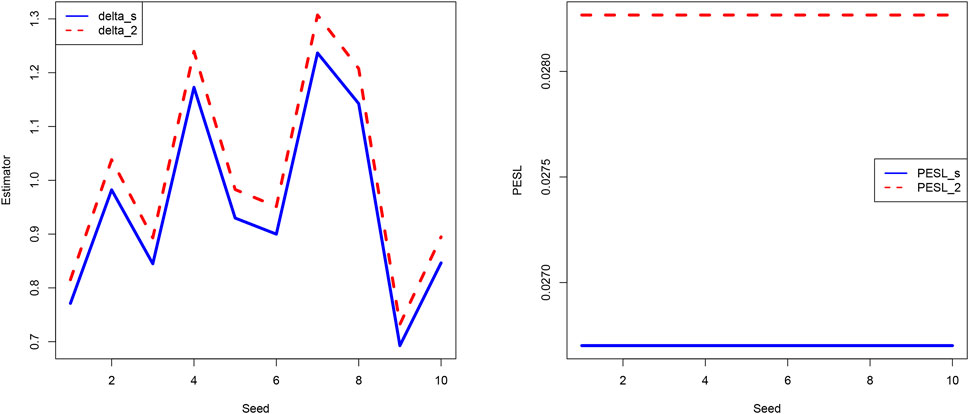

In Figure 3, we fix μ = 0 and n = 10, but allow the seed number to change from 1 to 10 (i.e., we change x). From the figure we see that the estimators and PESLs are functions of x. We see from the left plot of the figure that the estimators depend on x in an unpredictable manner, and

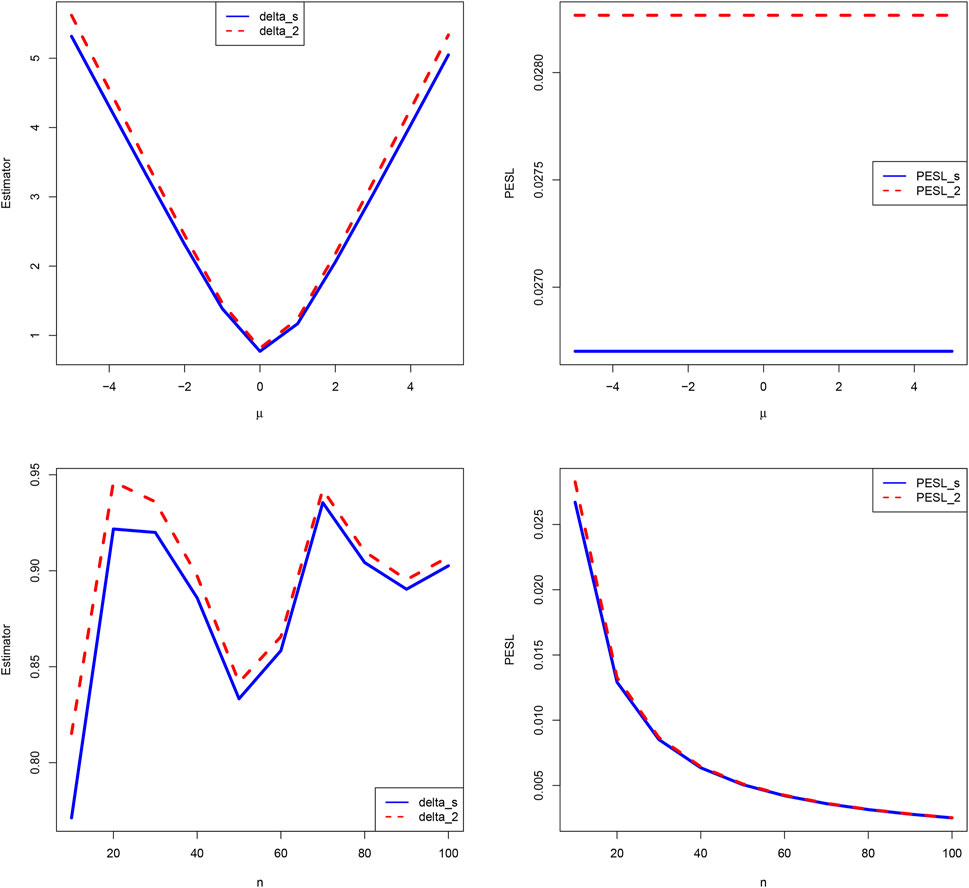

Now we allow one of the two parameters μ and n to change, holding other parameters fixed. Moreover, we also assume that the sample x is fixed, as it is the case for the real data. Figure 4 shows the estimators and PESLs as functions of μ and n. We see from the left plots of the figure that the estimators depend on μ and n, and (Eq. 6) is exemplified. More specifically, the estimators are first decreasing and then increasing functions of μ, and the estimators attain the minimum when μ = 0. However, the estimators fluctuate around some value when n increases. The right plots of the figure exhibit that the PESLs depend only on n, but do not depend on μ , and (Eq. 7) is exemplified. More specifically, the PESLs are decreasing functions of n. Furthermore, the two PESLs as functions of n are indistinguishable, as the two PESLs are very close. In summary, the results of the figure exemplify the theoretical studies of (Eqs 6, 7).

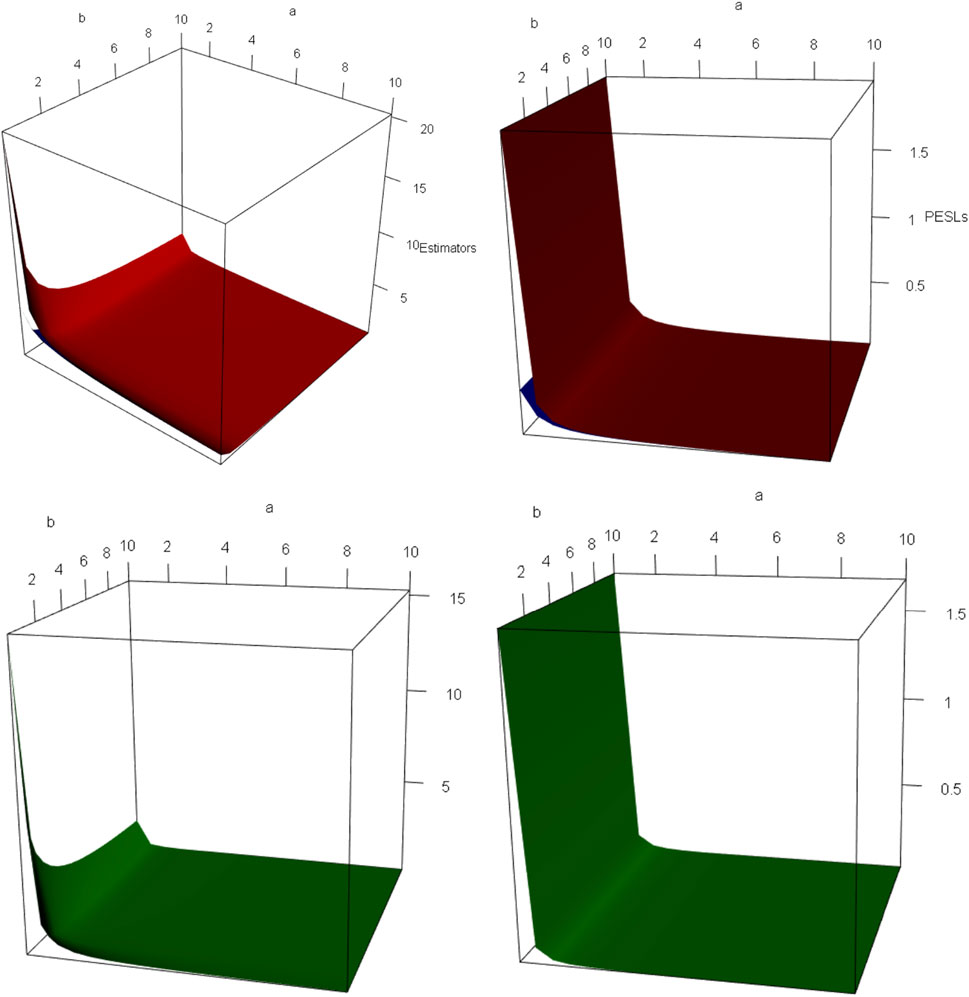

Since the estimators

FIGURE 5. The domain for

4 A Real Data Example

In this section, we exploit the data from finance. The R package quantmod ( (Ryan and Ulrich, 2017)) is exploited to download the data ˆGSPC (the S&P 500) during 2020-04-24 and 2021-07-02 from “finance.yahoo.com.” It is commonly believed that the monthly simple returns of the index data or the stock data are normally distributed. It is simple to check that the S&P 500 monthly simple returns follow the normal model. Usually, the data from real examples can be regarded as iid from the normal model with an unknown mean μ. However, the mean μ could be estimated by prior information or historical information. Alternatively, the mean μ could be estimated by the sample mean. Therefore, for simplicity, we assume that the mean μ is known. Assume that

for the S&P 500 monthly simple returns.

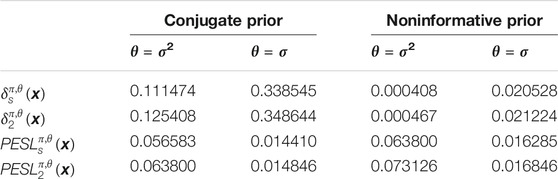

The Bayes estimators and the PESLs of the variance and scale parameters of the S&P 500 monthly simple returns for the conjugate and noninformative priors are summarized in Table 3. From the table, we observe the following facts.

• The two inequalities (Eqs 6, 7) are exemplified.

• Given the prior (conjugate or noninformative), the Bayes estimators are similar across different loss functions (Stein’s or squared error).

• Given the loss function, the Bayes estimators are quite different across different priors. Therefore, the prior has a larger influence than the loss function in calculating the Bayes estimators.

More results (the data of the S&P 500 monthly simple returns, the plot of the S&P 500 monthly close prices, the plot of the S&P 500 monthly simple returns, the histogram of the S&P 500 monthly simple returns) for the real data example can be found in the Supplementary Material due to space limitations.

5 Conclusions and Discussions

For the variance (θ = σ2) and scale (θ = σ) parameters of the normal model with a known mean μ, we recommend and analytically calculate the Bayes estimators,

Proposition 1 gives the three expectations of the

For the conjugate and noninformative priors, the posterior distribution of θ = σ2,

We find that the IRSL at

In addition, the IRSL at

The numerical simulations of the combination of the noninformative prior and the scale parameter exemplify the theoretical studies of (Eqs 6, 7), and that the PESLs depend only on n, but do not depend on μ and x. Moreover, in the real data example, we have calculated the Bayes estimators and the PESLs of the variance and scale parameters of the S&P 500 monthly simple returns for the conjugate and noninformative priors.

Unlike in frequentist paradigm, if

It is easy to see that

Similarly,

When there is no prior information about the unknown parameter of interest, we prefer the noninformative prior, as the hyperparameters α and β are somewhat arbitrary for the conjugate prior.

We remark that the Bayes estimator under Stein’s loss function is more appropriate than that under the squared error loss function, not because the former is smaller, but because Stein’s loss function which penalizes gross overestimation and gross underestimation equally is more appropriate for the positive restricted parameter.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Author YYZ wrote the first draft of the article. Author TZR did literature searches and revised the article. Author MML revised the article. All authors read and approved the final article.

Funding

The research was supported by the Ministry of Education (MOE) project of Humanities and Social Sciences on the west and the border area (20XJC910001), the National Social Science Fund of China (21XTJ001), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12001068; 72071019), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2020CDJQY-Z001; 2021CDJQY-047).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors are extremely grateful to the editor, the guest associate editor, and the reviewers for their insightful comments that led to significant improvement of the article.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdata.2021.763925/full#supplementary-material

References

Adler, D., and Murdoch, D. (2017). Rgl: 3D Visualization Using OpenGL. OthersR package version 0.98.1.

Berger, J. O., and Bernardo, J. M. (1992). On the Development of the Reference Prior Method. Bayesian Statistics 4. London: Oxford University Press.

Berger, J. O., Bernardo, J. M., and Sun, D. C. (2015). Overall Objective Priors. Bayesian Anal. 10, 189–221. doi:10.1214/14-ba915

Berger, J. O. (2006). The Case for Objective Bayesian Analysis. Bayesian Anal. 1, 385–402. doi:10.1214/06-ba115

Bernardo, J. M. (1979). Reference Posterior Distributions for Bayesian Inference. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodological) 41, 113–128. doi:10.1111/j.2517-6161.1979.tb01066.x

Bobotas, P., and Kourouklis, S. (2010). On the Estimation of a Normal Precision and a Normal Variance Ratio. Stat. Methodol. 7, 445–463. doi:10.1016/j.stamet.2010.01.001

Chen, M. H. (2014). Bayesian Statistics Lecture. Changchun, China: Statistics Graduate Summer SchoolSchool of Mathematics and Statistics, Northeast Normal University.

Datta, G. S., and Mukerjee, R. (2004). Probability Matching Priors: Higher Order Asymptotics. New York: Springer.

Ghosh, J. K., Delampady, M., and Samanta, T. (2006). An Introduction to Bayesian Analysis. New York: Springer.

James, W., and Stein, C. (1961). Estimation with Quadratic Loss. Proc. Fourth Berkeley Symp. Math. Stat. Probab. 1, 361–380.

Lehmann, E. L., and Casella, G. (1998). Theory of Point Estimation. 2nd edition. New York: Springer.

Maatta, J. M., and Casella, G. (1990). Developments in Decision-Theoretic Variance Estimation. Stat. Sci. 5, 90–120. doi:10.1214/ss/1177012263

Mao, S. S., and Tang, Y. C. (2012). Bayesian Statistics. 2nd edition. Beijing, China: Statistics Press.

Oono, Y., and Shinozaki, N. (2006). On a Class of Improved Estimators of Variance and Estimation under Order Restriction. J. Stat. Plann. Inference 136, 2584–2605. doi:10.1016/j.jspi.2004.10.023

Petropoulos, C., and Kourouklis, S. (2005). Estimation of a Scale Parameter in Mixture Models with Unknown Location. J. Stat. Plann. Inference 128, 191–218. doi:10.1016/j.jspi.2003.09.028

R Core Team. R (2021). A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Robert, C. P. (2007). The Bayesian Choice: From Decision-Theoretic Motivations to Computational Implementation. 2nd paperback edition. New York: Springer.

Ryan, J. A., and Ulrich, J. M. (2017). R Package Version 0, 4–10.Quantmod: Quantitative Financial Modelling Framework.

Sindhu, T. N., and Aslam, M. (2013). Bayesian Estimation on the Proportional Inverse Weibull Distribution under Different Loss Functions. Adv. Agric. Sci. Eng. Res. 3, 641–655.

Sindhu, T. N., Aslam, M., and Hussain, Z. (2016). Bayesian Estimation on the Generalized Logistic Distribution under Left Type-II Censoring. Thailand Statistician 14, 181–195.

Sindhu, T. N., and Aslam, M. (2013). Objective Bayesian Analysis for the Gompertz Distribution under Doudly Type II Cesored Data. Scientific J. Rev. 2, 194–208.

Sindhu, T. N., and Hussain, Z. (2018). Mixture of Two Generalized Inverted Exponential Distributions with Censored Sample: Properties and Estimation. Stat. Applicata-Italian J. Appl. Stat. 30, 373–391.

Sindhu, T. N., Saleem, M., and Aslam, M. (2013). Bayesian Estimation for Topp Leone Distribution under Trimmed Samples. J. Basic Appl. Scientific Res. 3, 347–360.

Sindhu, T. N., Aslam, M., and Hussain, Z. (2016). A Simulation Study of Parameters for the Censored Shifted Gompertz Mixture Distribution: A Bayesian Approach. J. Stat. Manage. Syst. 19, 423–450. doi:10.1080/09720510.2015.1103462

Sindhu, T. N., Feroze, N., and Aslam, M. (2017). A Class of Improved Informative Priors for Bayesian Analysis of Two-Component Mixture of Failure Time Distributions from Doubly Censored Data. J. Stat. Manage. Syst. 20, 871–900. doi:10.1080/09720510.2015.1121597

Sindhu, T. N., Khan, H. M., Hussain, Z., and Al-Zahrani, B. (2018). Bayesian Inference from the Mixture of Half-Normal Distributions under Censoring. J. Natn. Sci. Found. Sri Lanka 46, 587–600. doi:10.4038/jnsfsr.v46i4.8633

Sindhu, T. N., Riaz, M., Aslam, M., and Ahmed, Z. (2016). Bayes Estimation of Gumbel Mixture Models with Industrial Applications. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control. 38, 201–214. doi:10.1177/0142331215578690

Sun, J., Zhang, Y.-Y., and Sun, Y. (2021). The Empirical Bayes Estimators of the Rate Parameter of the Inverse Gamma Distribution with a Conjugate Inverse Gamma Prior under Stein's Loss Function. J. Stat. Comput. Simulation 91, 1504–1523. doi:10.1080/00949655.2020.1858299

Tibshirani, R. (1989). Noninformative Priors for One Parameter of Many. Biometrika 76, 604–608. doi:10.1093/biomet/76.3.604

Varian, H. R. (1975). “A Bayesian Approach to Real Estate Assessment,” in Studies in Bayesian Econometrics and Statistics. Editors S. E. Fienberg, and A. Zellner (Amsterdam: North Holland), 195–208.

Xie, Y.-H., Song, W.-H., Zhou, M.-Q., and Zhang, Y.-Y. (2018). The Bayes Posterior Estimator of the Variance Parameter of the Normal Distribution with a Normal-Inverse-Gamma Prior Under Stein’s Loss. Chin. J. Appl. Probab. Stat. 34, 551–564.

Zellner, A. (1986). Bayesian Estimation and Prediction Using Asymmetric Loss Functions. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 81, 446–451. doi:10.1080/01621459.1986.10478289

Zhang, Y.-Y. (2017). The Bayes Rule of the Variance Parameter of the Hierarchical Normal and Inverse Gamma Model under Stein's Loss. Commun. Stat. - Theor. Methods 46, 7125–7133. doi:10.1080/03610926.2016.1148733

Zhang, Y.-Y., Wang, Z.-Y., Duan, Z.-M., and Mi, W. (2019). The Empirical Bayes Estimators of the Parameter of the Poisson Distribution with a Conjugate Gamma Prior under Stein's Loss Function. J. Stat. Comput. Simulation 89, 3061–3074. doi:10.1080/00949655.2019.1652606

Zhang, Y.-Y., Xie, Y.-H., Song, W.-H., and Zhou, M.-Q. (2018). Three Strings of Inequalities Among Six Bayes Estimators. Commun. Stat. - Theor. Methods 47, 1953–1961. doi:10.1080/03610926.2017.1335411

Keywords: Bayes estimator, variance and scale parameters, normal model, conjugate and noninformative priors, Stein’s loss

Citation: Zhang Y-Y, Rong T-Z and Li M-M (2022) The Bayes Estimators of the Variance and Scale Parameters of the Normal Model With a Known Mean for the Conjugate and Noninformative Priors Under Stein’s Loss. Front. Big Data 4:763925. doi: 10.3389/fdata.2021.763925

Received: 24 August 2021; Accepted: 01 November 2021;

Published: 03 January 2022.

Edited by:

Niansheng Tang, Yunnan University, ChinaReviewed by:

Guikai Hu, East China University of Technology, ChinaAkio Namba, Kobe University, Japan

Tabassum Sindhu, Quaid-i-Azam University, Pakistan

Copyright © 2022 Zhang, Rong and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ying-Ying Zhang, cm9iZXJ0emhhbmd5eWluZ0BxcS5jb20=

Ying-Ying Zhang

Ying-Ying Zhang Teng-Zhong Rong1,2

Teng-Zhong Rong1,2