95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Cardiovasc. Med. , 24 November 2023

Sec. Lipids in Cardiovascular Disease

Volume 10 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1269172

Fatemeh Omidi1

Fatemeh Omidi1 Maryam Rahmannia2

Maryam Rahmannia2 Amir Hashem Shahidi Bonjar3

Amir Hashem Shahidi Bonjar3 Parsa Mohammadsharifi3,4

Parsa Mohammadsharifi3,4 Mohammad Javad Nasiri2*

Mohammad Javad Nasiri2* Tala Sarmastzadeh2*

Tala Sarmastzadeh2*

Introduction: Individuals diagnosed with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ACD) are exposed to an increased risk of cardiovascular events. Reducing low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels has been established as an effective approach to mitigate these risks. However, a comprehensive and up-to-date meta-analysis investigating the LDL-C-lowering effectiveness and the impact on coronary atherosclerotic plaque compositions of Ezetimibe has been lacking.

Methods: We conducted a systematic review by meticulously analyzing databases such as MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane CENTRAL for randomized controlled trials that evaluated the efficacy of ezetimibe in lowering LDL-C levels and its influence on coronary atherosclerotic plaques among individuals with ACD. This review encompassed studies available until August 1, 2023. In our analysis, we employed the weighted mean difference (WMD) as the aggregated statistical measure, accompanied by the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results: We encompassed a total of 20 eligible studies. Our findings unveiled that the combined therapy involving ezetimibe alongside statins led to a more substantial absolute decrease in LDL-C in comparison to using statins alone. This difference in means amounted to (−14.06 mg/dl; 95% CI −18.0 to −10.0; p = 0.0001). Furthermore, upon conducting subgroup analyses, it became evident that the intervention strategies proved effective in diminishing the volume of dense calcification (DC) in contrast to the control group.

Conclusions: Our study findings indicate that the inclusion of ezetimibe in conjunction with statin therapy leads to a modest yet meaningful additional reduction in LDL-C levels when compared to using statins in isolation. Importantly, the introduction of ezetimibe resulted in a significant decrease in the volume of DC. However, it is worth noting that further investigation is warranted to delve deeper into this phenomenon.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ACD) stands as the foremost contributor to global mortality. Elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) predominantly underlie the development of ACD (1, 2). To prevent future cardiovascular events, it is highly recommended to focus on the development of novel drugs that target and effectively lower lipoprotein levels. The use of tolerated statins is recommended for reducing LDL-C in patients with ACD. However, it is important to note that even with statin therapy, additional lipid-lowering therapies may be necessary for many patients with clinical ACD. Ezetimibe, a new cholesterol absorption inhibitor drug, has demonstrated the ability to further lower LDL-C levels (3–5). In a randomized controlled trial, it was demonstrated that the combination of ezetimibe with statins significantly reduces levels of LDL-C (6). Additionally, the combination of ezetimibe and statins leads to a substantial decrease in coronary plaque volume compared to statin treatment alone (7). Although the effectiveness of ezetimibe in treating ACD has been acknowledged, there is an absence of a comprehensive and up-to-date meta-analysis regarding the efficacy of ezetimibe in LDL-C lowering in ACD patients. Therefore, this study aimed to systematically assess the efficacy of ezetimibe in reducing LDL-C levels among individuals diagnosed with ACD.

We performed an extensive exploration of PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane CENTRAL databases to identify studies available until August 1, 2023, that reported on the efficacy and effectiveness of ezetimibe in patients with ACD. The search terms used were ezetimibe, coronary artery, atherosclerosis, and randomized controlled trial. Only studies published in English were included. This study adhered to the PRISMA statement for its design and reporting (Prospero pending ID: 449721) (8).

The collected records from the database searches were merged, and duplicates were removed through the utilization of EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters, Toronto, ON, Canada). Two reviewers, MR and MJN, conducted a thorough assessment of the records individually, utilizing the title/abstract and full-text screening process to exclude any studies that did not align with the study's objectives.

The studies included in the analysis met the following criteria:

Participants: The studies encompassed individuals diagnosed with ACD.

Intervention: The intervention being investigated was the use of ezetimibe therapy, either as a standalone treatment or in combination with other lipid-lowering therapies.

Comparison: patients who received standard treatment or in combination with other lipid-lowering therapies.

Outcome: The primary outcome was the average change observed in LDL-C levels when compared to the baseline measurements.

Two reviewers, namely MR and MJN, collaboratively devised a structured data extraction form and proceeded to extract information from all qualifying studies. Discrepancies were addressed through mutual agreement. The extracted data encompassed several aspects, including the primary author's name, publication year, study duration, study type, geographical location(s) of the study, ACD patient count, patient age, treatment regimens, demographic details (comprising age, gender, and nationality), and treatment outcomes.

The quality assessment of the included studies was conducted by two reviewers (MR and PM) using the Cochrane tool (9). In case of any discrepancies, a third reviewer (MJN) was involved. This assessment tool encompasses several domains, encompassing random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, completeness of outcome data, as well as additional factors like selective reporting and potential biases. Each study underwent categorization based on bias risk: low risk of bias when no bias concerns were detected, high risk of bias when bias concerns were present, or unclear risk of bias when there was an insufficient amount of information available for evaluation.

The statistical analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, version 3.0 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA). The weighted mean difference (WMD) was used as the pooled statistic, with a corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The degree of heterogeneity among the studies was assessed using the I2 value and p-value. In cases where the statistical heterogeneity between the studies was low (I2 ≤ 50% or p ≥ 0.1), the fixed-effect model was utilized. Conversely, if a significant level of inter-study heterogeneity was observed (I2 > 50% or p < 0.1), the random-effects model was employed. Cochran's Q test and the I2 statistic were used to assess between-study heterogeneity. Funnel plots, Egger's and Begg's tests were performed to access the publication bias of studies.

Figure 1 illustrates the flow diagram of the systematic review process. This thorough review yielded a total of 20 records that met the specified eligibility criteria. These records reported the primary outcome, which included variations in LDL-C levels from baseline or the LDL-C level after the study, or both. Importantly, these records contained sufficient independent information that enabled the subsequent meta-analysis.

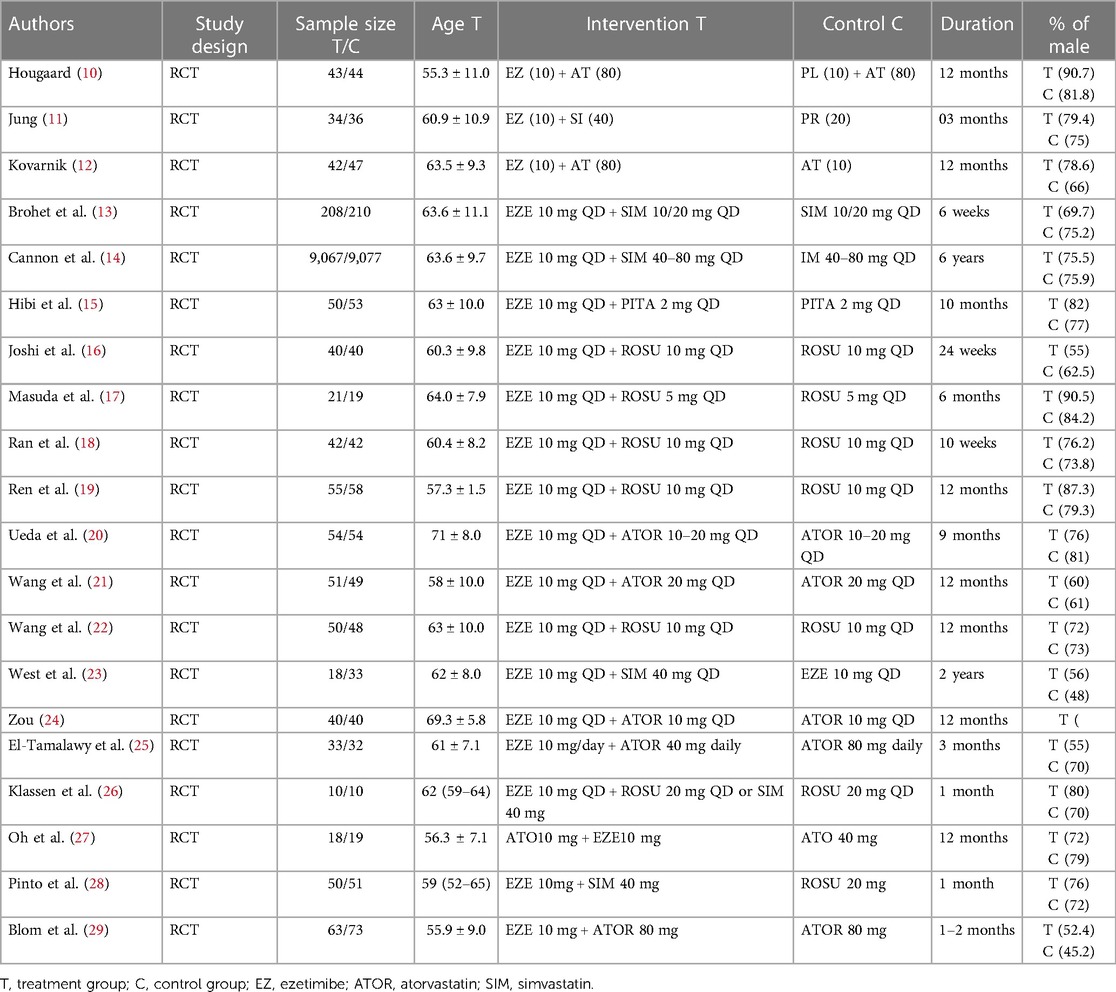

The rationale for including or excluding records is succinctly summarized, and the details of the 20 studies incorporated into the meta-analysis are presented in Table 1. This table provides comprehensive insights into various aspects, such as study design, duration, and baseline demographic characteristics.

Table 1. Demographics and baseline characteristics of patients included in the meta-analysis according to study and treatment group.

It is worth noting that while the intended focus was to assess the impact of ezetimibe therapy on LDL-C reduction, either alone or in combination with other lipid-lowering therapies, all the studies included in the analysis contrasted the combined treatment of ezetimibe and statin with statin monotherapy. Participant age across these studies ranged from 57 to 71 years on average, with variations depending on the specific treatment group (Table 1).

Regarding the risk of bias across the 20 trials, insufficient detail was provided about the randomization methodology, resulting in an unclear risk of selection bias for random sequence generation and allocation concealment. Other biases were assessed as low in the trials (Table 2).

As indicated in Figure 2, patients receiving a combination of statin and ezetimibe were found to have a significant additional reduction in LDL-C (WMD = −14.06 mg/dl; 95% CI −18.0 to −10.0, p < 0.0001) than those receiving statin alone. As shown in Supplementary Figure S1, some evidence for publication bias was observed (P = 0.02 for Begg rank correlation analysis; P = 0.03 for Egger weighted regression analysis).

The efficacy of FFP was evaluated in four studies. No significant heterogeneity was observed among the studies (I2 = 58.4%, p = 0.065). Using a random-effects model for analysis, our findings revealed that the treatment interventions within the study group did not result in a significant reduction in FFP volume when compared to the control group [WMD = −1.01, 95% CI −3.6–1.6, p = 0.45], as illustrated in Figure 3. As shown in Supplementary Figure S2, no evidence for publication bias was observed (P = 0.2 for Begg rank correlation analysis; P = 0.4 for Egger weighted regression analysis).

The effectiveness of NC was documented in three studies. Notably, there was no significant heterogeneity observed among these studies (I2 = 70.4%, p = 0.03). Employing a random-effects model analysis, the outcomes revealed no substantial disparity in the reduction of NC between the treatment group and the control group. The WMD equated to −5.41, with a 95% CI spanning from −13.3 to 2.5, yielding a p-value of 0.18, as depicted in Figure 4. As shown in Supplementary Figure S3, no evidence for publication bias was observed (P = 0.1 for Begg rank correlation analysis; P = 0.5 for Egger weighted regression analysis).

The efficacy of change DC was assessed in four studies. There was no notable heterogeneity observed among these studies (I2 = 0%, p = 0.42). Employing a fixed-effects model analysis, the findings demonstrated a significant distinction in the reduction of change DC between the treatment group and the control group. The WMD amounted to −1.14, accompanied by a 95% CI ranging from −1.4 to −0.8, resulting in a p-value of 0.00, as presented in Figure 5. As shown in Supplementary Figure S4, no evidence for publication bias was observed (P = 0.3 for Begg rank correlation analysis; P = 0.4 for Egger weighted regression analysis).

This meta-analysis has showcased that the inclusion of ezetimibe alongside statin therapy yields an extra reduction in LDL-C levels when dealing with patients diagnosed with ACD, in contrast to using statin therapy alone.

Our findings align with existing evidence concerning lipid-lowering treatments. For instance, a previous meta-analysis conducted by Shaya et al. also indicated a more significant relative reduction in LDL-C levels with the incorporation of ezetimibe alongside statin therapy, as opposed to using statins alone (30). Another meta-analysis demonstrated that ezetimibe significantly decreased coronary atherosclerotic plaque compared to the control group (placebo or statin monotherapy) (31). Similarly, the research conducted by Toyota et al. corroborates the notion that all three approaches aimed at enhancing LDL-C reduction, namely intensifying statin therapy, incorporating ezetimibe, and introducing PCSK9 inhibitors, have the potential to enhance clinical outcomes among individuals with high atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (32). Strilchuk et al. also highlights the effectiveness of combining rosuvastatin and ezetimibe for treating hypercholesterolemia and mixed dyslipidemia (33).

The outcome of our study is in line with the 2020 meta-analysis by Shaya et al., which demonstrated a reduced risk of ACD in patients who underwent ezetimibe treatment (30). Nonetheless, our study boasts certain strengths and distinctive aspects. We delved into studies specifically addressing FFP volume, NC volume, and DC volume. To mitigate the potential influence of confounding factors, we excluded studies involving populations with particular comorbidities. Moreover, articles lacking full text were omitted. On the contrary, we incorporated eight additional studies that were not part of the previous analysis. Our calculated WMD of (−14.06, 95% CI 18.0–10.0) was slightly higher than that of Shaya et al. (−21.8, 95% CI −26.5 to −17.1), while maintaining alignment in terms of direction and statistical significance.

The primary limitation of our study lies in its lack of originality, as the data regarding the efficacy of ezetimibe on LDL-C has been well-established and recognized for a considerable period, even documented in international guidelines. Nevertheless, revisiting and updating the scientific evidence can still hold significance. Several other limitations pertain to the studies we incorporated and are detailed as follows:

Firstly, the absence of recent clinical trial studies is notable, with the most recent one dating back to 2021. This underscores the necessity for further investigations with substantial participant populations to provide deeper insights into the subject.

Secondly, the included studies exhibited confounding factors, and due to limited and inconsistent data, we were unable to perform subgroup analyses to address these confounders adequately.

Thirdly, investigating the mortality benefits of ezetimibe, despite its robust LDL-C lowering effects, presents a notable challenge. Unraveling potential survival advantages hinges on various factors, encompassing drug efficacy, competing risks, off-target effects, baseline cardiovascular risk, and the duration of follow-up in the studies. The fourth limitation of our study is the significant variability in the duration of the included studies, potentially leading to uncertainty in the conclusions we have drawn.

This comprehensive systematic review delivers essential insights to decision-makers regarding the advantageous impact of ezetimibe on significant cardiovascular outcomes. Notably, the prominent observations highlight the prevalence of moderate to high certainty evidence that supports the effectiveness of ezetimibe in reducing LDL-C levels. Additionally, these agents contribute to the reduction in the volume of DC.

Our study indicates that the addition of ezetimibe to statin therapy results in a modest yet significant further reduction in LDL-C compared to statin monotherapy. Ezetimibe led to a significant reduction in DC volume; however, there were no statistically significant differences observed for NC, or change FFP volumes.

FO: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. MR: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. AS: Methodology, Validation, Resources, Writing review & editing. PM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. TS: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. MN: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1269172/full#supplementary-material

1. Kronenberg F, Mora S, Stroes ESG, Ference BA, Arsenault BJ, Berglund L, et al. Lipoprotein (a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: a European atherosclerosis society consensus statement. Eur Heart J. (2022) 43(39):3925–46. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac361

2. Mortensen MB, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated LDL cholesterol and increased risk of myocardial infarction and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in individuals aged 70–100 years: a contemporary primary prevention cohort. Lancet. (2020) 396(10263):1644–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32233-9

3. Ouchi Y, Sasaki J, Arai H, Yokote K, Harada K, Katayama Y, et al. Ezetimibe lipid-lowering trial on prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in 75 or older (ewtopia 75) a randomized, controlled trial. Circulation. (2019) 140(12):992–1003. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.039415

4. Phan BAP, Dayspring TD, Toth PP. Ezetimibe therapy: mechanism of action and clinical update. Vasc Health Risk Manag. (2012) 8:415–27. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S33664

5. Vavlukis M, Vavlukis A. Adding ezetimibe to statin therapy: latest evidence and clinical implications. Drugs Context. (2018) 7:1–9. doi: 10.7573/dic.212534

6. Murphy SA, Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, White JA, Lokhnygina Y, et al. Reduction in total cardiovascular events with ezetimibe/simvastatin post-acute coronary syndrome: the IMPROVE-IT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2016) 67(4):353–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.077

7. Lewek J, Niedziela J, Desperak P, Dyrbuś K, Osadnik T, Jankowski P, et al. Intensive statin therapy versus upfront combination therapy of statin and ezetimibe in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a propensity score matching analysis based on the PLACS data. J Am Heart Assoc. (2023) 12(18):e030414. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.123.030414

8. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. (2009) 151(4):264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

9. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J. (2011) 343:1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928

10. Hougaard M, Hansen HS, Thayssen P, Antonsen L, Junker A, Veien K, et al. Influence of ezetimibe in addition to high-dose atorvastatin therapy on plaque composition in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction assessed by serial: intravascular ultrasound with iMap: the OCTIVUS trial. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. (2017) 18(2):110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2016.11.010

11. Lee JH, Shin DH, Kim BK, Ko YG, Choi D, Jang Y, et al. Early effects of intensive lipid-lowering treatment on plaque characteristics assessed by virtual histology intravascular ultrasound. Yonsei Med J. (2016) 57(5):1087–94. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.5.1087

12. Kovarnik T, Mintz GS, Skalicka H, Kral A, Horak J, Skulec R, et al. Virtual histology evaluation of atherosclerosis regression during atorvastatin and ezetimibe administration: hEAVEN study. Circ J. (2012) 76(1):176–83. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-0730

13. Brohet C, Banai S, Alings AM, Massaad R, Davies MJ, Allen C. LDL-C goal attainment with the addition of ezetimibe to ongoing simvastatin treatment in coronary heart disease patients with hypercholesterolemia. Curr Med Res Opin. (2005) 21(4):571–8. doi: 10.1185/030079905X382004

14. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. (2015) 372(25):2387–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489

15. Hibi K, Sonoda S, Kawasaki M, Otsuji Y, Murohara T, Ishii H, et al. Effects of ezetimibe-statin combination therapy on coronary atherosclerosis in acute coronary syndrome. Circ J. (2018) 82(3):757–66. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0598

16. Joshi S, Sharma R, Rao HK, Narang U, Gupta N. Efficacy of combination therapy of rosuvastatin and ezetimibe vs. rosuvastatin monotherapy on lipid profile of patients with coronary artery disease. Journal of Clinical & Diagnostic Research. (2017) 11(12):1–12. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/30458.11004

17. Masuda J, Tanigawa T, Yamada T, Nishimura Y, Sasou T, Nakata T, et al. Effect of combination therapy of ezetimibe and rosuvastatin on regression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with coronary artery disease. Int Heart J. (2015) 56(3):278–85. doi: 10.1536/ihj.14-311

18. Ran D, Nie HJ, Gao YL, Deng SB, Du JL, Liu YJ, et al. A randomized, controlled comparison of different intensive lipid-lowering therapies in Chinese patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS): ezetimibe and rosuvastatin versus high-dose rosuvastatin. Int J Cardiol. (2017) 235:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.02.099

19. Ren Y, Zhu H, Fan Z, Gao Y, Tian N. Comparison of the effect of rosuvastatin versus rosuvastatin/ezetimibe on markers of inflammation in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Exp Ther Med. (2017) 14(5):4942–50. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.5175

20. Ueda Y, Hiro T, Hirayama A, Komatsu S, Matsuoka H, Takayama T, et al. Effect of ezetimibe on stabilization and regression of intracoronary plaque- the ZIPANGU study. Circ J. (2017) 81(11):1611–9. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0193

21. Wang J, Ai XB, Wang F, Zou YW, Li L, Yi XL. Efficacy of ezetimibe combined with atorvastatin in the treatment of carotid artery plaque in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus complicated with coronary heart disease. Int Angiol. (2017) 36(5):467–73. doi: 10.23736/S0392-9590.17.03818-4

22. Wang X, Zhao X, Li L, Yao H, Jiang Y, Zhang J. Effects of combination of ezetimibe and rosuvastatin on coronary artery plaque in patients with coronary heart disease. Heart Lung Circ. (2016) 25(5):459–65. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2015.10.012

23. West AM, Anderson JD, Meyer CH, Epstein FH, Wang H, Hagspiel KD, et al. The effect of ezetimibe on peripheral arterial atherosclerosis depends upon statin use at baseline. Atherosclerosis. (2011) 218(1):156–62. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.04.005

24. Zou Y. Effect of ezetimibe combined with low-dose atorvastain calcium on carotid atherosclerosis in elderly patients with coronary heart disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2016) 64:S328–S328.

25. El-Tamalawy MM, Ibrahim OM, Hassan TM, El-Barbari AA. Effect of combination therapy of ezetimibe and atorvastatin on remnant lipoprotein versus double atorvastatin dose in Egyptian diabetic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. (2018) 58(1):34–41. doi: 10.1002/jcph.976

26. Klassen A, Faccio AT, Picossi CR, Derogis PB, dos Santos, Ferreira CE, Lopes AS, et al. Evaluation of two highly effective lipid-lowering therapies in subjects with acute myocardial infarction. Sci Rep. (2021) 11(1):15973. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95455-z

27. Oh PC, Jang AY, Ha K, Kim M, Moon J, Suh SY, et al. Effect of atorvastatin (10 mg) and ezetimibe (10 mg) combination compared to atorvastatin (40 mg) alone on coronary atherosclerosis. Am J Cardiol. (2021) 154:22–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.05.039

28. Pinto LC, Mello AP, Izar MC, Damasceno NR, Neto AM, França CN, et al. Main differences between two highly effective lipid-lowering therapies in subclasses of lipoproteins in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Lipids Health Dis. (2021) 20(1):124. doi: 10.1186/s12944-021-01559-w

29. Blom DJ, Hala T, Bolognese M, Lillestol MJ, Toth PD, Burgess L, et al. A 52-week placebo-controlled trial of evolocumab in hyperlipidemia. N Engl J Med. (2014) 370(19):1809–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1316222

30. Shaya FT, Sing K, Milam R, Husain F, Del Aguila MA, Patel MY. Lipid-lowering efficacy of ezetimibe in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. (2020) 20:239–48. doi: 10.1007/s40256-019-00379-9

31. Chai B, Shen Y, Li Y, Wang X. Meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of ezetimibe for coronary atherosclerotic plaque compositions. Front Pharmacol. (2023) 14:1166762. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1166762

32. Toyota T, Morimoto T, Yamashita Y, Shiomi H, Kato T, Makiyama T, et al. More- versus less-intensive lipid-lowering therapy. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2019) 12(8):e005460. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005460

Keywords: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, ezetimibe, systematic review, cardiovascular disease, meta-analysis

Citation: Omidi F, Rahmannia M, Shahidi Bonjar AH, Mohammadsharifi P, Nasiri MJ and Sarmastzadeh T (2023) Ezetimibe and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10:1269172. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1269172

Received: 29 July 2023; Accepted: 9 November 2023;

Published: 24 November 2023.

Edited by:

Calvin Yeang, University of California, San Diego, United StatesReviewed by:

Federica Fogacci, University of Bologna, Italy© 2023 Omidi, Rahmannia, Shahidi Bonjar, Mohammadsharifi, Nasiri and Sarmastzadeh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammad Javad Nasiri bWoubmFzaXJpQGhvdG1haWwuY29t Tala Sarmastzadeh dC5zYXJtYXN0emFkZWhAc2JtdS5hYy5pcg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.