95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Cardiovasc. Med. , 26 May 2023

Sec. Cardiovascular Genetics and Systems Medicine

Volume 10 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1166324

This article is part of the Research Topic Role of Epigenetic Modulations and Transcription Factor in Cardiovascular Disease and Coronary Artery Spasm: Mechanisms and Interventions View all 6 articles

Background: Myocardial infarction (MI) ranks among the most prevalent cardiovascular diseases. Insufficient blood flow to the coronary arteries always leads to ischemic necrosis of the cardiac muscle. However, the mechanism of myocardial injury after MI remains unclear. This article aims to explore the potential common genes between mitophagy and MI and to construct a suitable prediction model.

Methods: Two Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets (GSE62646 and GSE59867) were used to screen the differential expression genes in peripheral blood. SVM, RF, and LASSO algorithm were employed to find MI and mitophagy-related genes. Moreover, DT, KNN, RF, SVM and LR were conducted to build the binary models, and screened the best model to further external validation (GSE61144) and internal validation (10-fold cross validation and Bootstrap), respectively. The performance of various machine learning models was compared. In addition, immune cell infiltration correlation analysis was conducted with MCP-Counter and CIBERSORT.

Results: We finally identified ATG5, TOMM20, MFN2 transcriptionally differed between MI and stable coronary artery diseases. Both internal and external validation supported that these three genes could accurately predict MI withAUC = 0.914 and 0.930 by logistic regression, respectively. Additionally, functional analysis suggested that monocytes and neutrophils might be involved in mitochondrial autophagy after myocardial infarction.

Conclusion: The data showed that the transcritional levels of ATG5, TOMM20 and MFN2 in patients with MI were significantly different from the control group, which might be helpful to further accurately diagnose diseases and have potential application value in clinical practice.

In recent years, the global average life expectancy has been on the rise due to improved quality of life. However, this has led to a surge in the number of individuals suffering from cardiovascular diseases, which claim the lives of 3.8 million men and 3.4 million women worldwide each year, according to the World Health Organization (1). Among these diseases, myocardial infarction (MI) is the most severe type of cardiovascular disease and the primary reason for the yearly increase in coronary artery disease mortality (2). Acute myocardial infarction (AMI), which encompasses various pathological changes such as ischemia and necrosis, represents the early stage of MI (3). Currently, the diagnosis of MI is typically reliant on electrocardiogram, physical examination, and certain biomarkers (4). MI is frequently encountered during clinical and forensic autopsies, and their diagnosis can present a challenge, particularly when there is no evidence of acute coronary occlusion (5). Hence, there is a need to investigate novel biomarkers to achieve a more precise diagnosis of the disease and gain a fresh understanding of it.

Presently, thrombolysis or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are effective treatment methods for coronary blood revascularization after myocardial infarction. However, these treatments may induce cardiac ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury and other pathologies, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, Ca2+ overload, and mitophagy dysregulation (6–8). Mitochondria are the primary energy factories in heart muscle cells and play a vital role in maintaining cardiac structure and function. When a myocardial infarction occurs, damaged mitochondria may be produced, which promotes oxidative stress and apoptosis. Mitophagy, therefore, is essential in maintaining cardiac structure and function (9–11). Studies indicate that irisin-activated optic atrophy 1 (OPA1) could increase PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy, prevent myocardial cell damage after myocardial infarction, and reverse cardiac dysfunction caused by ischemia, playing a pivotal role in maintaining myocardial cell vitality and mitochondrial function following myocardial infarction (12). Mitophagy is a type of selective autophagy that removes mitochondria with abnormal functions in cells. In related studies, Beclin1+/− and FUN14 domain-containing 1 (FUNDC1) knockout and transgenic mouse models, in conjunction with starvation and myocardial infarction models, suggest that mitophagy, rather than general autophagy, plays a cardioprotective role by regulating mitochondrial function (13). Another research team discovered that the level of mitophagy decreased significantly after myocardial infarction in a mouse myocardial infarction model. Moreover, the expression of nuclear dot protein 52 (NDP52) that promotes mitophagy could reduce myocardial damage caused by myocardial infarction. This suggests that myocardial damage caused by myocardial infarction may be closely related to decreased autophagy. Therefore, activation of autophagy may have a protective effect on myocardial cells (6).

The mechanism of myocardial injury in patients with myocardial infarction remains to be fully elucidated and identifying intervention targets may have significant clinical value. As such, exploring the relationship between myocardial infarction and mitophagy is imperative to develop additional therapeutic approaches and improve myocardial infarction prognosis. In this article, we used a diverse range of bioinformatics and ML methods to identify signature genes for myocardial infarction and mitophagy.

All data are free from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). The GSE59867, GSE62646, GSE61144 datasets were available in NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). And these datasets were based on GPL6106 platform of Sentrix Human-6 v2 Expression BeadChip and GPL6244 platform of [HuGene-1_0-st] Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST Array [transcript (gene) version] (14–16). GSE59867 and GSE62646 were combined as a training set and GSE61144 as a test set for external validation. All blood samples taken were within 24 h of the occurrence of myocardial infarction. Finally, the training set had 139 MI (Myocardial Infarction) and 60 CT (Stable coronary artery disease), and the testing set had 14 MI and 10 CT. The genes of mitophagy were downloaded from REACTOME (https://reactome.org). PCA (Principal Component Analysis) plots were also produced to show the differences before and after data merging (Supplementary Figure S1A, B).

Using the limma package of R software (17), all genes (n = 18,837) between myocardial infarction group and stable coronary disease group were explored, then it intersects with the mitophagy genes. This differential gene expression was visualized using a volcano plot (only those with p < 0.05 were labeled), while the comparison between MI group and control group was shown utilizing a heatmap.

The key genes were obtained by intersection of all genes and mitophagy gene set. ML algorithm is more suitable than traditional statistical methods when dealing with large, complex and high latitude data (18). Thus, we explored genes using three machine learning (ML) algorithms, namely Support Vector Machine-Recursive Feature Elimination (SVM-RFE), least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) as well as random forest.

The SVM-RFE algorithm of package “caret” is one of the most popular gene selection methods at present, which is designed for binary classification problems (19). The penalty parameter tuning was performed using the LASSO algorithm of the package “glmnet”, after tuning the penalty parameters in a 10-fold cross-validation procedure. This method is more effective than regression analysis in assessing high-dimensional data (20). The genes were further classified using the R package “randomforest”. An average error rate of key genes determines how many variables to include in a random forest model (21). We then calculated error rates for 1–1,000 trees. The top 10 genes were selected by SVM model and random forest model respectively. The genes with the highest accuracy were selected in lasso model. Signature genes of myocardial infarction were identified by the intersection of the three ML algorithms. The AUC was used to evaluate the models' diagnostic ability. The AUC greater than 0.7 illustrate good diagnostic effect.

Finally, it is decided to construct different supervised machine learning models with three genes as variables, which are decision tree (DT), K-nearest neighbor (KNN), random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM) and logistic regression (LR). Their accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and AUC were compared, and the final value for each parameter was obtained by taking the average of the values calculated through 5-fold cross-validation.

After the model performance comparison, a logistic regression model was constructed, and draw 1,000 bootstrap samples, and the model was rebuilt each time to draw the ROC. Then the performance of the model was evaluated by 10-fold cross-validation of 199 samples. About external validation, the GSE61144 dataset was downloaded (16), and 24 samples were predicted to verify the generalization ability of the model.

The package “IOBR” was used to analysis (22). CIBERSORT is a method that deconvolutes human immune cell subtype expression matrices using linear support vector regression to investigate the correlation between these genes and immune cells (23). Additionally, the microenvironment cell population (MCP)-counter algorithm was utilized. This method can reliably quantify the abundance of various immune based on transcriptomic data for each sample (24). The correlation between some genes and some immune cells was analyzed by spearman method.

R (version 4.2.2) was used for all statistical analyses in this study. In all cases, a default p or adjust. p of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All p values were two-sided tests. According to Figure 1, the flow chart about this research was as follows.

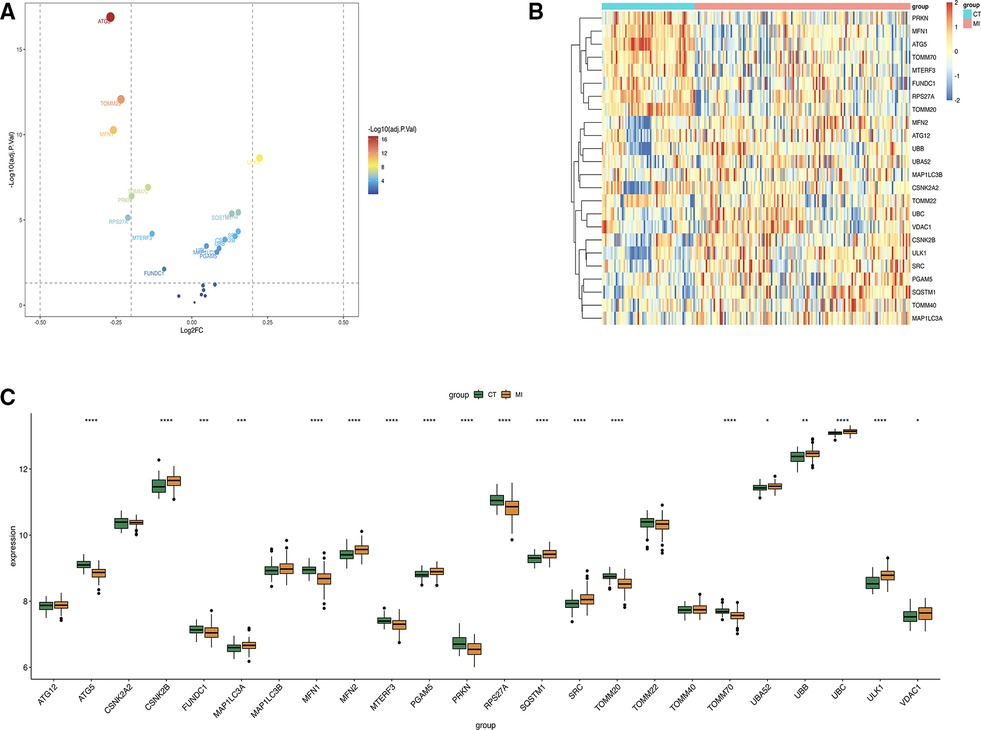

The intersection of all genes derived from “limma” package and mitophagy genes was taken, and 24 related genes were obtained. Only 17 of them were statistically different. The volcano plot was made to display 24 genes of mitophagy (Figure 2A), the heatmap showed the genes between MI group and control group (Figure 2B) and made the boxplot (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. (A) Volcano plot about mitophagy genes. (B) Heat map of the 24 differentially expressed mitophagy genes in MI samples and healthy samples. (C) Boxplot of 24 gene expression levels.

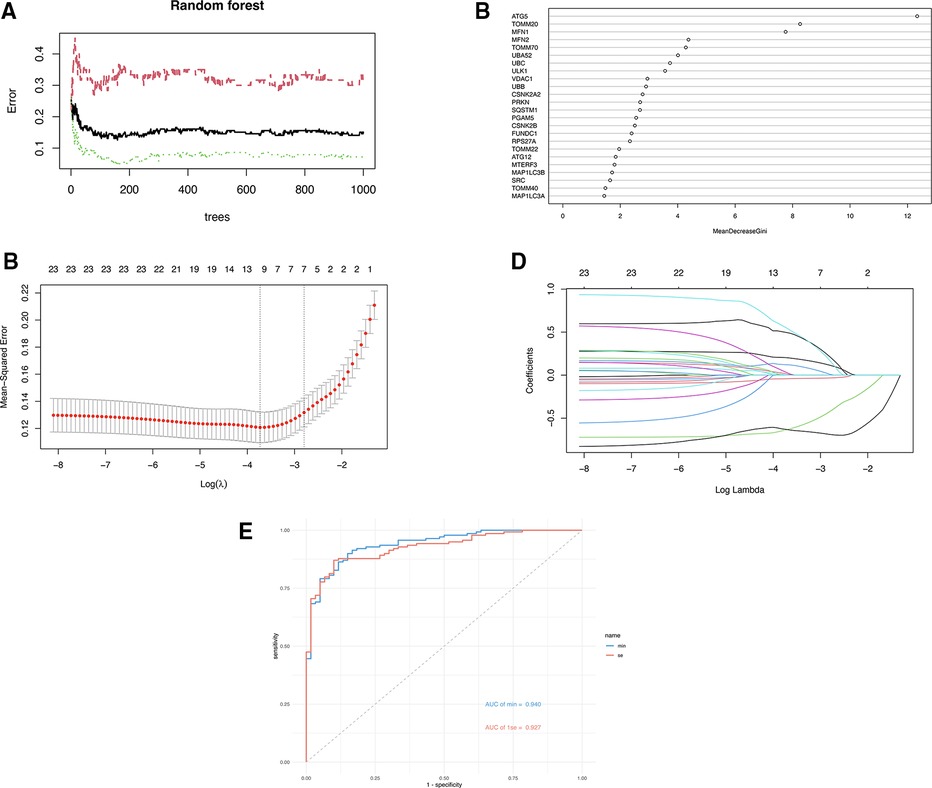

Three ML algorithms were utilized to pick up the signature genes from 24 genes. For the SVM-RFE and random forest algorithms select top 10 of genes respectively (Figures 3A, B). The smallest error is on 159 trees. And LASSO analysis selected the genes with the highest accuracy (based on ROC) (Figures 3C–E). Table 1 presents the genes under consideration. Finally, the three genes were determined by taking the intersection of the three algorithms, including ATG5, TOMM20, MFN2 (Figure 4). Detailed information about the genes is shown in Table 2.

Figure 3. (A) The error rate confidence intervals for random forest model. (B) The relative importance of genes in random forest model. (C) Penalty plot of the LASSO model with error bars denoting standard errors. (D) The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) coefficient profiles. (E) ROC curves of two gene sets based on LASSO algorithm.

Two of the signature genes were highly expressed in the MI group and one was underexpressed, suggesting that three genes could have a latent ability to diagnosis MI (Figures 5A–C). Moreover, the AUC of the ROC of these key genes was 0.88 of ATG5, 0.83 of TOMM20, 0.71 of MFN2 respectively (Figures 5D–F).

The metrics of each model are shown in Table 3. DT, KNN and SVM have the highest accuracy of 0.814. LR has the highest AUC (0.915) and precision (0.739). DT has the highest F1-score (0.702). All algorithms have recall rates of more than 50%. The roc curve of each model is shown in the attachment (Supplementary Figure S3), along with the AUC shown in boxplot (Supplementary Figure S4).

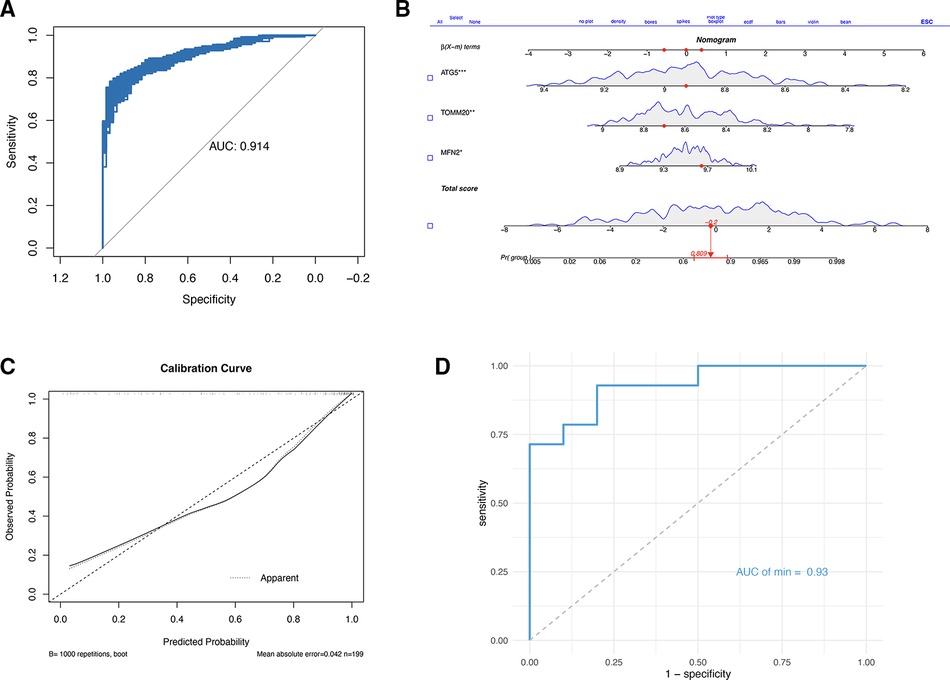

Subsequently, a multi-factor logistic regression model was constructed with these three genes, the AUC of the model was obtained by using 10-fold cross-validation, and then the average value was obtained (Supplementary Table S1) (0.915), then the fitting effect of the model was verified with the training set, and 1,000 bootstrap samples were drawn (Figure 6A). A nomogram was generated using the logistic regression model (Figure 6B). A calibration curve was drawn to evaluate the classifier's predictive ability, which revealed minimal differences between the predicted and actual MI risks. This result indicates the model's high effectiveness, as depicted in Figure 6C. Finally, the data set GSE61144 was used for external verification to obtain the ROC (Figure 6D), the AUC was 0.93. These data indicate that three signature genes have a good ability to predict MI. The results of bootstrap method were displayed in Supplementary Figure S2.

Figure 6. (A) Logical regression and bootstrap validation based on three gene constructs. (B) Nomogram to predict the occurrence of MI. (C) Calibration curve to assess the predictive power of the logistic model. (D) ROC based on GSE61144.

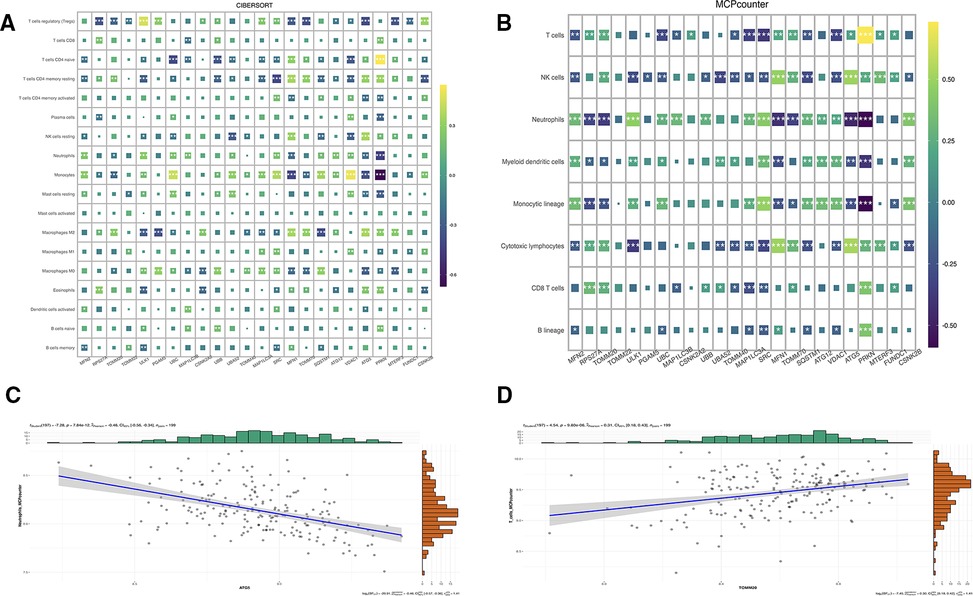

Immune characteristics were evaluated by CIBERSORT method, 24 genes and T cells CD4 naive, neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages M2, macrophages M0 has a strong relevance among which MFN2 was positively correlated with monocytes and neutrophils, and negatively correlated with T cell CD4 naive and T cell CD4 memory resting, and ATG5 was positively correlated with T cell CD4 memory resting and NK cells resting, and negatively correlated with Tregs and monocytes (Figure 7A). According to MCP-counter method, 24 genes were strongly correlated with T cells, NK cells, neutrophils, monocytic lineage and cytotoxic lymphocytes (Figure 7B), there was a negative correlation between ATG5 and neutrophils (Figure 7C). And a positive correlation between TOMM20 and T cells (Figure 7D). Subsequently, correlation diagrams of 3 diagnostic genes and inflammatory factors were also made, indicating that the 3 genes screened in this study were strongly correlated with TNF, IL11, TGFB1, CD4 and IL10 (Figure 8).

Figure 7. (A) Correlation map of genes and immune cells based on CIBERSORT algorithm. (B) Correlation map of genes and immune cells based on MCPcounter algorithm. (C) Correlation between ATG5 and neutrophils based on MCPcounter calculations. (D) Correlation between TOMM20 and T cells based on MCPcounter calculations.

Globally, CVDs continue to be the primary cause of mortality on a global scale, and they also play a significant role in the global burden of illness (25). MI is also the leading cause of death and morbidity (2). Employing bioinformatics techniques, this study identified differences in genes in patients with myocardial infarction and patients in stable condition. Thereafter, the SVM-RFE algorithm, random forest algorithm, and LASSO algorithm were utilized to identify mitophagy genes associated with myocardial infarction, including ATG5, TOMM20, and MFN2. Next, various supervised machine learning algorithm models were constructed, with logistic regression exhibiting the highest AUC value (0.915). Subsequently, a logistic regression model was constructed to validate the genes internally and externally. Finally, the CIBERSORT algorithm and MCP-counter algorithm were employed to explore the correlation between immune cell infiltration and the signature genes.

Cardiac mitochondria are responsible for oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) to produce ATP energy, which is crucial for cardiac function (26). Therefore, mitochondrial dysfunction may represent a latent mechanism in the pathogenesis or prognosis of myocardial infarction. Mitophagy is known to increase during cardiac stress and injury, helping to clear damaged mitochondria and prevent oxidative damage as well as cell death (27, 28). Therefore, additional research is necessary to ascertain whether the induction of mitophagy following myocardial infarction is indicative of a distinct prognosis.

ATG5 is a pivotal component of the ATG12-ATG5-ATG16 complex that plays a crucial role in promoting phagophoric membrane elongation in autophagic vesicles (29, 30). Wang et al. have demonstrated that Atg5-dependent autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved autodigestive process that is essential for induced cardiomyocyte reprogramming (iCM) (31). Meanwhile, Schriner et al. suggest that increased autophagy activity may lead to thinner and longer survival time of Atg5 transgenic mice (29). Further studies have revealed that ATG5 defects can lead to increased ubiquitination levels in heart tissue, sarcomere disorders, mitochondrial aggregation, and other related abnormalities. Knockout of the ATG5 gene leads to myocardial cell necrosis and increased cross-sectional area of myocardial cells, indicating that ATG5 is involved in myocardial hypertrophy and obesity, and the regulation of lipid metabolism (32–34). Although few studies have explored the relationship between ATG5 and AMI, we speculate that ATG5 is related to MI.

Translocase of Outer Mitochondrial Membrane 20 (TOMM20). When intracellular mitochondrial autophagy occurs, mitochondrial degradation occurs, resulting in the reduction of marker proteins in the inner and outer membrane of mitochondria. It has been reported to be involved in many cancers (35, 36). Studies have demonstrated a correlation between increased TOMM20 expression and elevated mitochondrial mass in certain tumors (37). TOMM20 expression directly impacts mitochondrial processes, such as ATP production and membrane potential maintenance (37). Nonetheless, the precise manner in which TOMM20 expression contributes to tumor development and progression remains unclear. In addition, TOMM20 has also been used to evaluate the degree of mitophagy (38). The decreased expression of TOMM20 can greatly reduce the damage of myocardial mitochondria and reduce the apoptosis of myocardial cells (39). The reason for this phenomenon in this study may be that the blood samples were collected within 24 h after the occurrence of myocardial infarction, and this phenomenon occurs in order to reduce the damage of the heart.

Mitochondrial fusion associated protein 2 (Mfn2), mostly found in mitochondria, is involved in inhibiting Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK/MAPK and Ras-PI3K-Akt signaling pathways, thereby suppressing proliferation and promoting apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells (40). Overexpression of Mfn1 or Mfn2 has been found to inhibit the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) and reduce cell death after myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (41). However, Mfn2 deficiency has been shown to impair cardiac function, cause heightened myocardial fibrosis, increase mitochondrial damage, and worsen oxidative stress (42). Furthermore, the increased expression of Mfn2 has been reported to contribute to mitochondrial hyperfusion (43).

In Figures 7A, B, it is evident that a significant proportion of genes are strongly correlated with monocytes and neutrophils. Monocytes, which rapidly accumulate in the injured area after myocardial injury, exhibit a pro-inflammatory and phagocytic role on necrotic substances, as indicated by previous studies, with the expression of cytokines and growth factors in the infarct area, the environment in the infarct area changes, and the infiltrated monocytes transform into mature macrophages (44). Furthermore, neutrophils are known to exert an anti-inflammatory effect through apoptosis-related mechanisms. Specifically, they secrete factors such as annexin A1 and lactoferrin, which inhibit further recruitment of neutrophils and promote macrophage aggregation to accelerate the apoptosis process. Neutrophils also stimulate macrophages to release anti-inflammatory substances such as IL-10 and TGF-β by activating the anti-inflammatory program in macrophages (45). This may explain why these factors have a significant meaning in Figure 8. Recent studies suggest that MFN2, in addition to regulating mitochondrial fusion, has the capacity to regulate immune responses (46). However, the mechanisms underlying the effect of mitophagy on myocardial infarction through immune cells warrant further exploration.

Most drugs that target mitophagy are non-specific and may affect other cells. Thus, identifying new therapeutic approaches to regulate mitophagy is crucial (47). The three genes discussed in this paper, namely ATG5, TOMM20, and MFN2, may provide potential targets for improving the prognosis of myocardial infarction. Myocardial infarction is a multifaceted condition that results from the heart's inability to adequately fulfill the metabolic needs of body tissues, ultimately leading to impaired function. Multiple research studies have demonstrated the indispensability of mitophagy as a critical protective mechanism for repairing damage associated with this syndrome.

The strength of this study lies in the use of bioinformatics methods and multiple machine learning algorithms to identify critical genes associated with myocardial infarction and mitophagy. Nonetheless, certain limitations and deficiencies must be acknowledged. Firstly, the study relied mainly on public databases, which may introduce bias due to the small amount of data. Nevertheless, our results were validated using K-fold cross-validation and bootstrap resampling, which demonstrate their reliability and generalizability to some extent. Secondly, the blood samples were collected within one day after myocardial infarction, and therefore the findings pertain to short-term effects. Furthermore, further studies involving larger clinical samples are required to confirm our results. Finally, the mechanism underlying the immunological infiltration of the selected genes remains to be elucidated.

With bioinformatics analysis on a GEO dataset and utilizing three distinct machine learning algorithms, we successfully identified three mitophagy-related genes closely associated with MI. Furthermore, a prediction model with desired accuracy has been established. Our research provides critical insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying MI and mitophagy, thereby offering potential valuable avenues for further investigation.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material. Further queries can be sent to the corresponding author(s).

Ethical review and approval was not required for this study in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

ZY was responsible for statistical analysis and mapping. HW and LS were responsible for reviewing manuscripts and revising them. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions from publicly available databases.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1166324/full#supplementary-material.

1. Mendis S, Davis S, Norrving B. Organizational update. Stroke. (2015) 46:e121–122. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008097

2. Jneid H, Alam M, Virani SS, Bozkurt B. Redefining myocardial infarction: what is new in the ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF third universal definition of myocardial infarction? Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. (2013) 9:169. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-9-3-169

3. Almaghrbi H, Giordo R, Pintus G, Zayed H. Non-coding RNAs as biomarkers of myocardial infarction. Clin Chim Acta. (2023) 540:117222. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2023.117222

4. Wu Y, Pan N, An Y, Xu M, Tan L, Zhang L. Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for myocardial infarction. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2020) 7:617277. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.617277

5. Michaud K, Basso C, d’Amati G, Giordano C, Kholová I, Preston SD, et al. Diagnosis of myocardial infarction at autopsy: AECVP reappraisal in the light of the current clinical classification. Virchows Arch. (2020) 476:179–94. doi: 10.1007/s00428-019-02662-1

6. Sun M, Zhang W, Bi Y, Xu H, Abudureyimu M, Peng H, et al. NDP52 protects against myocardial infarction-provoked cardiac anomalies through promoting autophagosome–lysosome fusion via recruiting TBK1 and RAB7. Antioxid Redox Signaling. (2022) 36:1119–35. doi: 10.1089/ars.2020.8253

7. Bugger H, Pfeil K. Mitochondrial ROS in myocardial ischemia reperfusion and remodeling. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. (2020) 1866:165768. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165768

8. Zhang Y, Jiao L, Sun L, Li Y, Gao Y, Xu C, et al. LncRNA ZFAS1 as a SERCA2a inhibitor to cause intracellular Ca2+ overload and contractile dysfunction in a mouse model of myocardial infarction. Circ Res. (2018) 122:1354–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.312117

9. Nakai A, Yamaguchi O, Takeda T, Higuchi Y, Hikoso S, Taniike M, et al. The role of autophagy in cardiomyocytes in the basal state and in response to hemodynamic stress. Nat Med. (2007) 13:619–24. doi: 10.1038/nm1574

10. Gan B, Peng X, Nagy T, Alcaraz A, Gu H, Guan J-L. Role of FIP200 in cardiac and liver development and its regulation of TNFα and TSC–mTOR signaling pathways. J Cell Biol. (2006) 175:121–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604129

11. Kaizuka T, Mizushima N. Atg13 is essential for autophagy and cardiac development in mice. Mol Cell Biol. (2016) 36:585–95. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01005-15

12. Wang B, Nie J, Wu L, Hu Y, Wen Z, Dong L, et al. AMPKα2 protects against the development of heart failure by enhancing mitophagy via PINK1 phosphorylation. Circ Res. (2018) 122:712–29. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.312317

13. Xu C, Cao Y, Liu R, Liu L, Zhang W, Fang X, et al. Mitophagy-regulated mitochondrial health strongly protects the heart against cardiac dysfunction after acute myocardial infarction. J Cellular Molecular Medi. (2022) 26:1315–26. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.17190

14. Maciejak A, Kiliszek M, Michalak M, Tulacz D, Opolski G, Matlak K, et al. Gene expression profiling reveals potential prognostic biomarkers associated with the progression of heart failure. Genome Med. (2015) 7(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0149-z

15. Kiliszek M, Burzynska B, Michalak M, Gora M, Winkler A, Maciejak A, et al. Altered gene expression pattern in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction. PLoS One. (2012) 7:e50054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050054

16. Park H-J, Noh JH, Eun JW, Koh Y-S, Seo SM, Park WS, et al. Assessment and diagnostic relevance of novel serum biomarkers for early decision of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Oncotarget. (2015) 6:12970–83. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4001

17. Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. (2015) 43:e47–e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007

18. Deo RC. Machine learning in medicine. Circulation. (2015) 132:1920–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.001593

19. Huang M-L, Hung Y-H, Lee WM, Li RK, Jiang B-R. SVM-RFE based feature selection and taguchi parameters optimization for multiclass SVM classifier. Sci World J. (2014) 2014:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2014/795624

20. Tibshirani R. The lasso method for Variable selection in the cox model. Statist Med. (1997) 16:385–95. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970228)16:4-385::aid-sim380%3E3.0.co;2-3

21. Izmirlian G. Application of the random forest classification algorithm to a SELDI-TOF proteomics study in the setting of a cancer prevention trial. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2004) 1020:154–74. doi: 10.1196/annals.1310.015

22. IOBR. Multi-Omics Immuno-Oncology Biological Research to Decode Tumor Microenvironment and Signatures—PubMed. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34276676/ (Accessed February 4, 2023).

23. Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. (2015) 12:453–7. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337

24. Becht E, Giraldo NA, Lacroix L, Buttard B, Elarouci N, Petitprez F, et al. Estimating the population abundance of tissue-infiltrating immune and stromal cell populations using gene expression. Genome Biol. (2016) 17:218. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1070-5

25. Füller D, Jaehn P, Andresen-Bundus H, Pagonas N, Holmberg C, Christ M, et al. Impact of the educational level on non-fatal health outcomes following myocardial infarction. Curr Probl Cardiol. (2022) 47:101340. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2022.101340

26. Shires SE, Gustafsson ÅB. Mitophagy and heart failure. J Mol Med. (2015) 93:253–62. doi: 10.1007/s00109-015-1254-6

27. Hoshino A, Mita Y, Okawa Y, Ariyoshi M, Iwai-Kanai E, Ueyama T, et al. Cytosolic p53 inhibits parkin-mediated mitophagy and promotes mitochondrial dysfunction in the mouse heart. Nat Commun. (2013) 4:2308. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3308

28. Kubli DA, Zhang X, Lee Y, Hanna RA, Quinsay MN, Nguyen CK, et al. Parkin protein deficiency exacerbates cardiac injury and reduces survival following myocardial infarction. J Biol Chem. (2013) 288:915–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.411363

29. Pyo J-O, Yoo S-M, Ahn H-H, Nah J, Hong S-H, Kam T-I, et al. Overexpression of Atg5 in mice activates autophagy and extends lifespan. Nat Commun. (2013) 4:2300. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3300

30. Hescheler J, Halbach M, Egert U, Lu ZJ, Bohlen H, Fleischmann BK, et al. Determination of electrical properties of ES cell-derived cardiomyocytes using MEAs. J Electrocardiol. (2004) 37:110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2004.08.034

31. Wang L, Ma H, Huang P, Xie Y, Near D, Wang H, et al. Down-regulation of Beclin1 promotes direct cardiac reprogramming. Sci Transl Med. (2020) 12:eaay7856. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aay7856

32. Wang L, Ye N, Lian X, Peng F, Zhang H, Gong H. MiR-208a-3p aggravates autophagy through the PDCD4-ATG5 pathway in ang II-induced H9c2 cardiomyoblasts. Biomed Pharmacother. (2018) 98:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.12.019

33. Xiao Y, Deng Y, Yuan F, Xia T, Liu H, Li Z, et al. An ATF4-ATG5 signaling in hypothalamic POMC neurons regulates obesity. Autophagy. (2017) 13:1088–9. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2017.1307488

34. Zhang Y, Li Y, Liu Z, Zhao Q, Zhang H, Wang X, et al. PEDF Regulates lipid metabolism and reduces apoptosis in hypoxic H9c2 cells by inducing autophagy related 5-mediated autophagy via PEDF-R. Mol Med Report. (2018) 17:7170–6. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8733

35. Zhao Z, Han F, He Y, Yang S, Hua L, Wu J, et al. Stromal-epithelial metabolic coupling in gastric cancer: stromal MCT4 and mitochondrial TOMM20 as poor prognostic factors. Eur J Surg Oncol. (2014) 40:1361–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.04.005

36. Curry JM, Tassone P, Cotzia P, Sprandio J, Luginbuhl A, Cognetti DM, et al. Multicompartment metabolism in papillary thyroid cancer. Laryngoscope. (2016) 126:2410–8. doi: 10.1002/lary.25799

37. Park S-H, Lee A-R, Choi K, Joung S, Yoon J-B, Kim S. TOMM20 as a potential therapeutic target of colorectal cancer. BMB Rep. (2019) 52:712–7. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2019.52.12.249

38. Zheng T, Wang H, Chen Y, Chen X, Wu Z, Hu Q, et al. Src activation aggravates podocyte injury in diabetic nephropathy via suppression of FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy. Front Pharmacol. (2022) 13:897046. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.897046

39. Xu G, Ma Y, Jin J, Wang X. Activation of AMPK/p38/Nrf2 is involved in resveratrol alleviating myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in diabetic rats as an endogenous antioxidant stress feedback. Ann Transl Med. (2022) 10:890–890. doi: 10.21037/atm-22-3789

40. Guo X, Chen K-H, Guo Y, Liao H, Tang J, Xiao R-P. Mitofusin 2 triggers vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis via mitochondrial death pathway. Circ Res. (2007) 101:1113–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.157644

41. Ong S-B, Hall AR, Hausenloy DJ. Mitochondrial dynamics in cardiovascular health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signaling. (2013) 19:400–14. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4777

42. Pei H, Du J, Song X, He L, Zhang Y, Li X, et al. Melatonin prevents adverse myocardial infarction remodeling via Notch1/Mfn2 pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. (2016) 97:408–17. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.06.015

43. Chen QM. Nrf2 for protection against oxidant generation and mitochondrial damage in cardiac injury. Free Radic Biol Med. (2022) 179:133–43. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.12.001

44. Williams MR, Azcutia V, Newton G, Alcaide P, Luscinskas FW. Emerging mechanisms of neutrophil recruitment across endothelium. Trends Immunol. (2011) 32:461–9. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.009

45. Bournazou I, Pound JD, Duffin R, Bournazos S, Melville LA, Brown SB, et al. Apoptotic human cells inhibit migration of granulocytes via release of lactoferrin. J Clin Invest. (2009) 119:20–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI36226

46. Guo W, Mu K, Li W-S, Gao S-X, Wang L-F, Li X-M, et al. Identification of mitochondria-related key gene and association with immune cells infiltration in intervertebral disc degeneration. Front Genet. (2023) 14:1135767. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2023.1135767

Keywords: machine learning—ML, mycardial infarction, mitophagy, signature gene, immune cells infiltration

Citation: Yang Z, Sun L and Wang H (2023) Identification of mitophagy-related genes with potential clinical utility in myocardial infarction at transcriptional level. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10:1166324. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1166324

Received: 16 February 2023; Accepted: 9 May 2023;

Published: 26 May 2023.

Edited by:

Ming-Yow Hung, Taipei Medical University, TaiwanReviewed by:

Ming-Jui Hung, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Taiwan© 2023 Yang, Sun and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hua Wang d2g3NDIyMEBhbGl5dW4uY29t Liang Sun c3VuYm11QGZveG1haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.