95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Cardiovasc. Med. , 23 March 2023

Sec. Coronary Artery Disease

Volume 10 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1106594

Ju Hyeon Kim1

Ju Hyeon Kim1 Luca Franchin2

Luca Franchin2 Soon Jun Hong1*

Soon Jun Hong1* Jung-Joon Cha1

Jung-Joon Cha1 Subin Lim1

Subin Lim1 Hyung Joon Joo1

Hyung Joon Joo1 Jae Hyoung Park1

Jae Hyoung Park1 Cheol Woong Yu1

Cheol Woong Yu1 Do-Sun Lim1

Do-Sun Lim1 Ovidio De Filippo2

Ovidio De Filippo2 Hyeon-Cheol Gwon3

Hyeon-Cheol Gwon3 Francesco Piroli2

Francesco Piroli2 Hyo-Soo Kim4

Hyo-Soo Kim4 Wojciech Wanha5

Wojciech Wanha5 Ki Hong Choi3

Ki Hong Choi3 Young Bin Song3

Young Bin Song3 Giuseppe Patti6

Giuseppe Patti6 Chang-Wook Nam7

Chang-Wook Nam7 Francesco Bruno2

Francesco Bruno2 Jeehoon Kang4

Jeehoon Kang4 Pier Paolo Bocchino2

Pier Paolo Bocchino2 Gaetano Maria De Ferrari2

Gaetano Maria De Ferrari2 Bon-Kwon Koo4

Bon-Kwon Koo4 Fabrizio D’Ascenzo2

Fabrizio D’Ascenzo2

Background: Older patients who treated by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are at a higher risk of adverse cardiac outcomes. We sought to investigate the clinical impact of bifurcation PCI in older patients from Korea and Italy.

Methods: We selected 5,537 patients who underwent bifurcation PCI from the BIFURCAT (comBined Insights from the Unified RAIN and COBIS bifurcAtion regisTries) database. The primary outcome was a composite of target vessel myocardial infarction, clinically driven target lesion revascularization, and stent thrombosis at two years.

Results: In patients aged ≥75 years, the mean age was 80.1 ± 4.0 years, 65.2% were men, and 33.7% had diabetes. Older patients more frequently presented with chronic kidney disease (CKD), severe coronary calcification, and left main coronary artery disease (LMCA). During a median follow-up of 2.1 years, older patients showed similar adverse clinical outcomes compared to younger patients (the primary outcome, 5.7% vs. 4.5%; p = 0.21). Advanced age was not an independent predictor of the primary outcome (p = 0.93) in overall patients. Both CKD and LMCA were independent predictors regardless of age group.

Conclusions: Older patients (≥75 years) showed similar clinical outcomes to those of younger patients after bifurcation PCI. Advanced age alone should not deter physicians from performing complex PCIs for bifurcation disease.

As the number of older patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) increases, clinicians face more complex and severe disease, such as true coronary bifurcation lesions, with worse clinical outcomes (1). Comorbidities are more prevalent in older patients with CAD (2, 3), and they show a higher risk of adverse clinical events as well as periprocedural complications compared to younger patients (4). Moreover, frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional disability, as well as advanced age, have been linked to increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (5–7). Consequently, older patients have been undertreated with coronary revascularization compared to their younger counterparts (8–10) and thus underrepresented in clinical trials using percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (8, 11). In real-world clinical practice, physicians opt for conservative treatment in older patients, although the guidelines do not suggest any age limitations in the use of PCI (12).

Numerous studies have evaluated the clinical outcomes of complex bifurcation stenting (13–15), and PCI for bifurcation CAD remains challenging and requires complex procedures. Furthermore, there is a limited data about the prognosis of older patients with bifurcation CAD. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the impact of advanced age on clinical outcomes in a large multinational cohort that underwent bifurcation PCI.

The comBined Insights From the Unified RAIN and COBIS bifurcAtion regisTries (BIFURCAT) database was created by merging two large datasets (16). The COBIS III (COronary BIfurcation Stenting [COBIS] III, NCT03068494) registry is a multicenter, nationwide cohort in South Korea that includes consecutive patients who underwent PCI for bifurcation CAD with second-generation drug-eluting stents (DESs) from January 2010 to December 2014 (17). The retrospective RAIN (veRy Thin Stents for Patients With Left mAIn or bifurcatioN in Real Life [RAIN], NCT03544294) registry included consecutive patients whose coronary bifurcations and/or unprotected left main coronary artery disease (LMCA) were treated with very thin DESs (<100 mm) in 15 European centers from June 2015 to December 2017 (18). The detailed information for both registries has been previously reported.

PCI was performed as per the current practice guidelines by the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology and the European Society of Cardiology (12). Periprocedural anticoagulation was performed using either low-molecular-weight or unfractionated heparin to maintain an activated clotting time of 250–300 s during PCI. All patients received aspirin (300 mg) and P2Y12 inhibitor loading doses (300 or 600 mg for clopidogrel, 180 mg for ticagrelor, and 60 mg for prasugrel) before PCI, unless they had previously received these antiplatelet medications. The stenting strategy (provisional or upfront two-stent technique), access sites, type of implanted DES, and use of intracoronary imaging were left to the discretion of the operator. All patients were prescribed standard maintenance doses of dual antiplatelet drugs after bifurcation PCI. The duration of dual antiplatelet drugs was left to the decisions of the caring physicians.

A total of 5,537 patients from Korea and Italy were included in the BIFURCAT registry (Supplementary Figure S1). A detailed description of the study population, including the demographic, angiographic, and procedural data, was obtained using a web-based system. Additional data, such as the duration of prescribed antiplatelet therapy, was obtained from a review of electronic health records or telephone contact if necessary. All clinical outcomes from the participating centers were reviewed and validated by an independent clinical event-adjudicating committee.

The clinical characteristics of older patients (aged ≥75 years) were compared to those of younger patients (aged <75 years). The primary outcome was a composite of target vessel myocardial infarction (MI), clinically driven target lesion revascularization (TLR), and stent thrombosis (ST) at two years post-PCI. All-cause death and any MI were secondary outcomes, as were the single components of the primary outcome. MI was defined as an elevation of the cardiac enzyme level greater than the upper limit of normal with ischemic symptoms or signs indicative of ischemia, not related to the index PCI (19). TLR was considered as a repeat PCI of the lesion within 5 mm of the inserted stent. ST was classified as definite, probable, or possible using the definitions of the Academic Research Consortium (20). Both definite and probable cases were included as STs in this analysis. Outcomes of interest were appraised according to age at the time of the index PCI (aged ≥75 vs. <75 years).

Continuous variables were reported as means ± standard deviations, whereas categorical variables were reported as counts (percentages). Group comparisons were performed using parametric (unpaired t-test) and nonparametric (Mann–Whitney U test) tests for continuous variables, whereas the chi-square test was used for categorical variables. The cumulative incidence of clinical outcome events was calculated based on Kaplan–Meier censoring estimates, and intergroup comparisons were assessed using the log-rank test. The relationships between age and clinical outcomes were explored using restricted cubic splines (21). A multivariable Cox model was used to calculate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Variables with significance in the univariable analysis (p < 0.2) or clinically relevant variables were included in the final model to determine independent predictors of the primary outcome. The final model included age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease (CKD), prior history of PCI and/or coronary artery bypass graft surgery, left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction <40%, presentation of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), LMCA, true bifurcation lesion, severe calcification, and stenting technique. True bifurcation lesions were defined as Medina (1,1,1; 1,0,1; and 0,1,1) lesions (22). To account for the effect of age, the sub-distribution HR was calculated using the Fine-Gray competing risk model (23). In addition, a propensity score (PS) matching analysis was also performed, and each patient in the older group was matched with those in the younger group at a 1:1 ratio using the nearest neighbor method, with a caliper width equal to 0.2 of the standard deviation of the logit PS. Statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (version 4.1.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Except for the subgroup interaction analysis (p < 0.1), p values of 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

A total of 5,537 patients were included in the current analysis, and 1,415 patients (26%) were aged ≥75 years (the older group). The median age of all study patients was 67 (IQR, 58–75) years (Supplementary Figure S2). Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics, including baseline demographics. The mean age was 80.1 ± 4.0 years and 65.2% were men in older patients. Comorbidities, including hypertension (77.4% vs. 62.2%), CKD (23.7% vs. 9.3%), and history of MI (22.5% vs. 15.2%), were more frequent in older patients. Older patients presented more frequently with LMCA (33.1% vs. 28.6%, p = 0.001) and more complex coronary lesions, including a higher proportion of true bifurcation lesions (51.8% vs. 46.4%) and severe calcification (24.5% vs. 15.0%). Overall, PCI was performed with the two-stent strategy in 17.6% of patients, and older patients showed a shorter stent length of the main branch with a smaller diameter than younger patients.

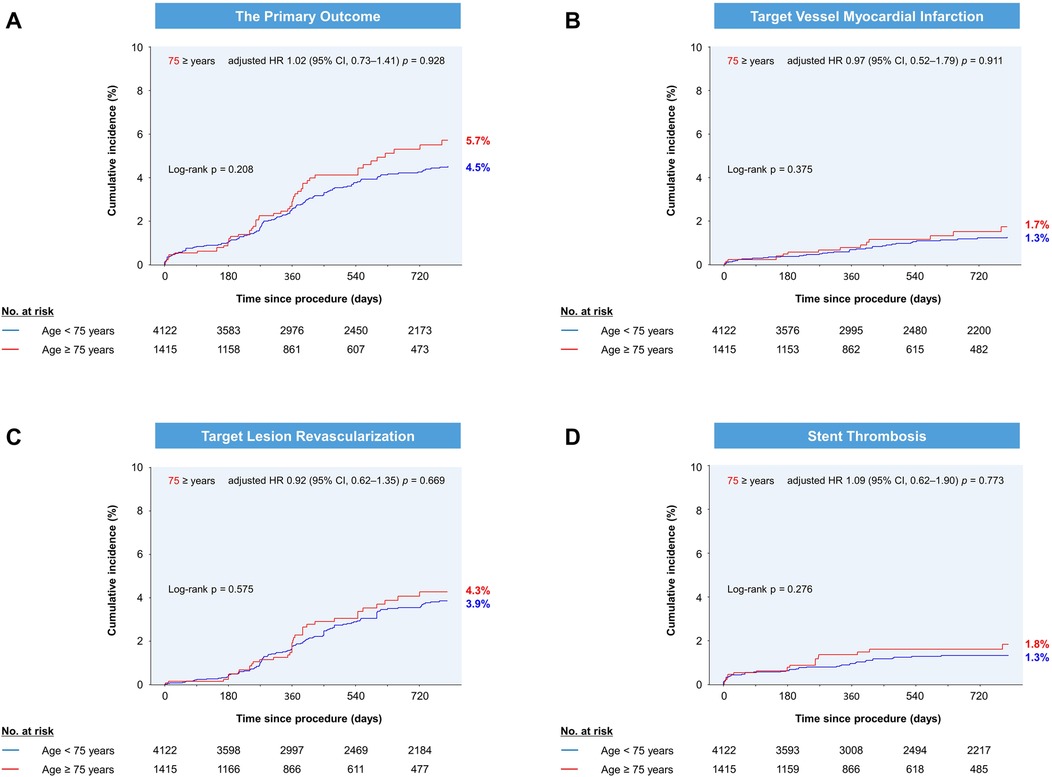

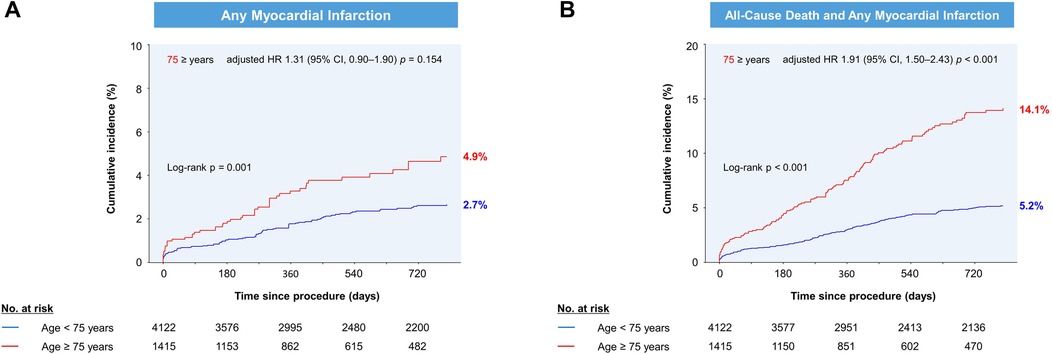

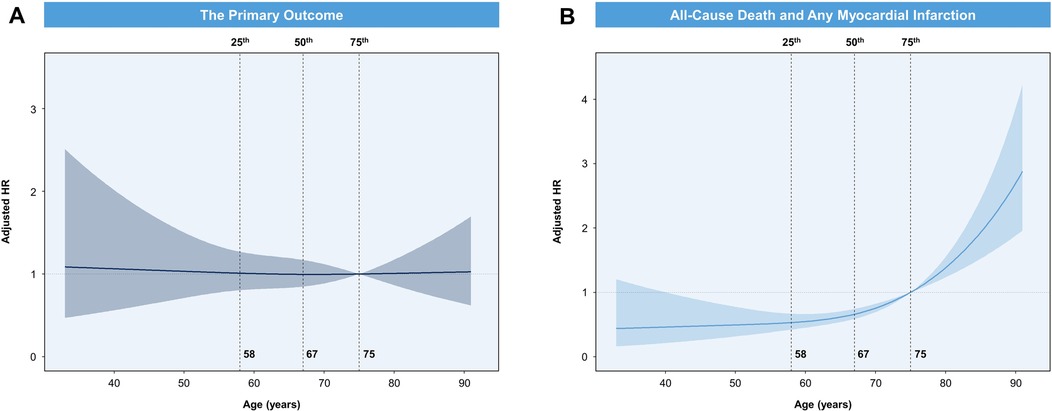

During a median follow-up of 2.1 (IQR, 0.9–2.2) years, the cumulative incidence of the primary outcome was similar between older and younger patients (p = 0.208; Figure 1). Older patients had similar rates of target vessel MI, clinically driven TLR, and ST compared to younger patients (Table 2). After adjustment, advanced age was not associated with the primary outcome (adjusted HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.73–1.41). In contrast, higher rates of any MI (4.9% vs. 2.7%) or combined all-cause death and any MI (14.1% vs. 5.2%) were observed in older patients (Figure 2). As a continuous variable, age had no effect on the adjusted risk of the primary outcome, and it had a curvilinear effect on the adjusted risk of combined all-cause death and any MI (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence of (A) the primary outcome, (B) target vessel myocardial infarction, (C) target lesion revascularization, and (D) stent thrombosis by age group. The Kaplan-Meier estimates at 720 days are shown. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2. Cumulative incidence of (A) any myocardial infarction and (B) combined all-cause death and any myocardial infarction by age group. The Kaplan-Meier estimates at 720 days are shown. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 3. (A) spline curve for the association of age with the hazard of the primary outcome. (B) Spline curve for the association of age with the hazard of combined all-cause death and any myocardial infarction.

The independent predictors of the primary outcome were CKD, LMCA, and the two-stent strategy (Table 3). LMCA was the strongest predictor of the primary outcome (adjusted HR 2.07; 95% CI, 1.53–2.79). After adjustment with the Cox regression model, age ≥75 years was not an independent factor associated with the primary outcome. When all-cause death was modelled as a single competing outcome, the adjusted sub-distribution HR of the primary outcome was 0.98 (95% CI, 0.69–1.38; p = 0.91) for the older age group (Table 4). The multivariable-adjusted independent predictors of the primary outcome according to age subgroup are shown in Supplementary Table S1. In the older group, the presence of LMCA was a significant predictor (adjusted HR, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.31–4.21; p = 0.004), and CKD (adjusted HR, 1.85; 95% CI, 0.94–3.63; p = 0.073) showed a borderline significance. In the younger group, hypertension, diabetes, CKD, LV ejection fraction <40%, LMCA, and the two-stent strategy were important in predicting the risk of the primary outcome. In the subgroup analysis according to diabetes, advanced age (≥75 years) showed a significant interaction for the primary outcome (p for interaction = 0.036; Supplementary Figure S3).

After 1: 1 PS matching, 2,634 patients were selected (the older group, n = 1,317). Demographic and clinical parameters at baseline were well balanced, and the standardized mean differences between the groups were <10.0% for all variables (Supplementary Table S2). The incidences of the primary outcome at 2 years were comparable between groups, and the rates of combined all-cause death and any MI were higher in older patients (Supplementary Table S3).

The current study included 5,537 patients with bifurcation CAD and involved a real-world multinational registry created to evaluate the incidence and predictors of adverse cardiac events. The main findings of the present analysis are as follows: (1) the risk of the primary outcome was similar in older patients who underwent coronary bifurcation stenting compared to younger patients; (2) after adjustment, advanced age showed a significant association with an increased risk for combined all-cause death and any MI; and (3) both CKD and LMCA were significant predictors of the primary outcome regardless of age after bifurcation PCI.

Bifurcation CAD accounts for approximately 20% of all contemporary PCI and represents a challenging subgroup with poor clinical outcomes (1). Previous studies on bifurcation disease have reported worse outcomes with advanced age (24, 25). Older patients often present with atypical symptoms and non-diagnostic ECG findings, which delay proper diagnosis (2). They also have a higher prevalence of comorbidities (3), and treatment is often complicated by bleeding, renal failure, and neurological impairment (26). Our large dataset reflects the real-world experience of complex PCI using second-generation DESs for bifurcation CAD. In our study, patients with advanced age (≥75 years) presented with more complex CAD (diffuse, calcified, and LMCA) as well as a higher prevalence of hypertension, CKD, prior MI, and previous coronary revascularization. They also had a higher proportion of ACS as a clinical indication for PCI (p = 0.094). Nevertheless, the incidence of the primary outcome was comparable between older and younger patients in our study.

Our primary analysis precluded all-cause death and MI to mitigate the effect of age on adverse clinical outcomes. Advanced age was a strong predictor of spontaneous MI in medically managed patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS (7). Advanced age was also linked to higher all-cause death after PCI (4). Similarly, age as a continuous variable was correlated with the adjusted risk of combined all-cause death and any MI in the current analysis (Figure 3). Thus, all-cause death was a competing event for the primary outcome in our analysis. The Fine-Gray competing risk regression model showed that age ≥75 years was not an independent predictor of the primary outcome (Table 4). Thus, performing complex PCI for bifurcation CAD now seems feasible in older patients. Age-related factors such as postprocedural complications or more frequent underlying comorbidities in older patients can explain the increased risk of all-cause death and any MI after complex bifurcation stenting.

In our multivariable Cox analysis, CKD and LMCA were independent predictors of adverse outcomes regardless of age (Supplementary Table S1), consistent with the results of previous studies (13–15). Clinical outcomes, including cardiac death, were also worse with the two-stent strategy in patients with bifurcation CAD (13, 27). Similarly, the two-stent strategy was associated with a significant risk for the primary outcome in this study (Table 3). Notably, traditional risk factors, such as diabetes and reduced LV systolic function, did not reach statistical significance in the older group, probably due to the limited number of patients. Subgroup analysis showed that the impact of advanced age on clinical outcomes was more obvious in the non-diabetic subgroup (Supplementary Figure S3).

Although PS matching is a technique that attempts to estimate the effect of a treatment or intervention by accounting for the covariates that predict receiving the treatment or intervention, the results of the PS-matched analysis demonstrated the robustness of the multivariable-adjusted analysis. However, this should be interpreted with caution, since the likelihood of being old (≥75 years) is neither treatment nor intervention (Supplementary Table S2).

Although our study included a large number of Korean (47.8%) and European (52.2%) patients, it has a few limitations. Using real-world registry data, this retrospective observational study design was associated with an inherent selection bias. It should also be acknowledged that PCI techniques have improved since the initiation of each registry. Moreover, information on the use of intracoronary imaging was not available, making it difficult to reflect the contemporary performance of PCI. The COBIS III registry previously reported 39.8% (1054/2648) of intravascular ultrasound guidance during PCI (13). In addition, the present dataset included only the results of PCI with second-generation DES implantation, not allowing any direct comparison with older patients who were treated with medical therapy alone for bifurcation CAD. Some important patient-centered variables, such as frailty and functional disability in older patients, were not available, providing limited information to clarify high-risk patients who could derive the greatest benefit from complex invasive procedures. Lastly, the BIFURCAT database lacks information on bleeding events, which could be an additional relevant outcome in older patients undergoing complex PCI.

Among patients with coronary bifurcation stenting, older patients (aged ≥75 years) had an acceptable occurrence of target vessel MI, clinically driven TLR, and ST compared to younger patients (aged <75 years). Increasing age was independently associated with the adjusted risk of combined all-cause death and any MI. CKD and LMCA were independent predictors of adverse cardiac events regardless of age group. Therefore, advanced age alone should not deter physicians from performing complex PCIs for bifurcation CAD.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available upon request; further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Korea University Anam Hospital. The ethics committee waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved the submitted version for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1106594/full#supplementary-material.

1. Sawaya FJ, Lefèvre T, Chevalier B, Garot P, Hovasse T, Morice MC, et al. Contemporary approach to coronary bifurcation lesion treatment. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2016) 9:1861–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.06.056

2. Soiza RL, Leslie SJ, Harrild K, Peden NR, Hargreaves AD. Age-dependent differences in presentation, risk factor profile, and outcome of suspected acute coronary syndrome. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2005) 53:1961–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53573.x

3. Malkin CJ, Prakash R, Chew DP. The impact of increased age on outcome from a strategy of early invasive management and revascularisation in patients with acute coronary syndromes: retrospective analysis study from the ACACIA registry. BMJ Open. (2012) 2:e000540. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000540

4. de Boer MJ, Ottervanger JP, Suryapranata H, Hoorntje JC, Dambrink JH, Gosselink AT, et al. Old age and outcome after primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2010) 58:867–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02821.x

5. Newby LK. Acute coronary syndromes in the elderly. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown. (2011) 12:220–2. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e328343e9ce

6. Sanchis J, Bonanad C, Ruiz V, Fernández J, García-Blas S, Mainar L, et al. Frailty and other geriatric conditions for risk stratification of older patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. (2014) 168:784–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.022

7. Lopes RD, Leonardi S, Neely B, Neely ML, Ohman EM, Ardissino D, et al. Spontaneous MI after non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome managed without revascularization: the TRILOGY ACS trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2016) 67:1289–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.034

8. Zaman MJ, Stirling S, Shepstone L, Ryding A, Flather M, Bachmann M, et al. The association between older age and receipt of care and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a cohort study of the myocardial ischaemia national audit project (MINAP). Eur Heart J. (2014) 35:1551–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu039

9. Vandecasteele EH, De Buyzere M, Gevaert S, de Meester A, Convens C, Dubois P, et al. Reperfusion therapy and mortality in octogenarian STEMI patients: results from the Belgian STEMI registry. Clin Res Cardiol. (2013) 102:837–45. doi: 10.1007/s00392-013-0600-3

10. Somma KA, Bhatt DL, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, Cox M, Laskey W, et al. Guideline adherence after ST-segment elevation versus non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2012) 5:654–61. doi: 10.1161/circoutcomes.111.963959

11. Tahhan AS, Vaduganathan M, Greene SJ, Alrohaibani A, Raad M, Gafeer M, et al. Enrollment of older patients, women, and racial/ethnic minority groups in contemporary acute coronary syndrome clinical trials: a systematic review. JAMA Cardiol. (2020) 5:714–22. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0359

12. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, Alfonso F, Banning AP, Benedetto U, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. (2019) 40:87–165. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394

13. Cha JJ, Hong SJ, Joo HJ, Park JH, Yu CW, Ahn TH, et al. Differential factors for predicting outcomes in left main versus non-left main coronary bifurcation stenting. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:3024. doi: 10.3390/jcm10143024

14. Lee JM, Hahn JY, Kang J, Park KW, Chun WJ, Rha SW, et al. Differential prognostic effect between first- and second-generation drug-eluting stents in coronary bifurcation lesions: patient-level analysis of the Korean bifurcation pooled cohorts. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2015) 8:1318–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.05.014

15. Song PS, Song YB, Lee JM, Hahn JY, Choi SH, Choi JH, et al. Major predictors of long-term clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention for coronary bifurcation lesions with 2-stent strategy: patient-level analysis of the Korean bifurcation pooled cohorts. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2016) 9:1879–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.06.049

16. De Filippo O, Kang J, Bruno F, Han JK, Saglietto A, Yang HM, et al. Benefit of extended dual antiplatelet therapy duration in acute coronary syndrome patients treated with drug eluting stents for coronary bifurcation lesions (from the BIFURCAT registry). Am J Cardiol. (2021) 156:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.07.005

17. Choi KH, Song YB, Lee JM, Park TK, Yang JH, Hahn JY, et al. Prognostic effects of treatment strategies for left main versus non-left main bifurcation percutaneous coronary intervention with current-generation drug-eluting stent. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2020) 13:e008543. doi: 10.1161/circinterventions.119.008543

18. Gaido L, D’Ascenzo F, Imori Y, Wojakowski W, Saglietto A, Figini F, et al. Impact of kissing balloon in patients treated with ultrathin stents for left main lesions and bifurcations: an analysis from the RAIN-CARDIOGROUP VII study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. (2020) 13:e008325. doi: 10.1161/circinterventions.119.008325

19. Moussa ID, Klein LW, Shah B, Mehran R, Mack MJ, Brilakis ES, et al. Consideration of a new definition of clinically relevant myocardial infarction after coronary revascularization: an expert consensus document from the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions (SCAI). J Am Coll Cardiol. (2013) 62:1563–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.720

20. Garcia-Garcia HM, McFadden EP, Farb A, Mehran R, Stone GW, Spertus J, et al. Standardized End point definitions for coronary intervention trials: the academic research consortium-2 consensus document. Circulation. (2018) 137:2635–50. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.117.029289

21. Heinzl H, Kaider A. Gaining more flexibility in cox proportional hazards regression models with cubic spline functions. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. (1997) 54:201–8. doi: 10.1016/s0169-2607(97)00043-6

22. Medina A, Suárez de Lezo J, Pan M. A new classification of coronary bifurcation lesions. Rev Esp Cardiol. (2006) 59:183. doi: 10.1157/13084649

23. Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. (2016) 133:601–9. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.115.017719

24. Ge L, Airoldi F, Iakovou I, Cosgrave J, Michev I, Sangiorgi GM, et al. Clinical and angiographic outcome after implantation of drug-eluting stents in bifurcation lesions with the crush stent technique: importance of final kissing balloon post-dilation. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2005) 46:613–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.032

25. Routledge HC, Morice MC, Lefèvre T, Garot P, De Marco F, Vaquerizo B, et al. 2-year Outcome of patients treated for bifurcation coronary disease with provisional side branch T-stenting using drug-eluting stents. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2008) 1:358–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.05.005

26. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, Capodanno D, Barbato E, Funck-Brentano C, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. (2020) 41:407–77. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425

Keywords: bifurcation, coronary intervention, left main coronary artery (LMCA) disease, old age, elderly

Citation: Kim JH, Franchin L, Hong SJ, Cha J-J, Lim S, Joo HJ, Park JH, Yu CW, Lim D-S, De Filippo O, Gwon H-C, Piroli F, Kim H-S, Wanha W, Choi KH, Song YB, Patti G, Nam C-W, Bruno F, Kang J, Bocchino PP, De Ferrari GM, Koo B-K and D’Ascenzo F (2023) Two-Year clinical outcomes after coronary bifurcation stenting in older patients from Korea and Italy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10:1106594. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1106594

Received: 23 November 2022; Accepted: 7 March 2023;

Published: 23 March 2023.

Edited by:

Panagiotis Xaplanteris, CHU Saint-Pierre, Université Libre de Bruxelles, BelgiumReviewed by:

Marco Zuin, University Hospital of Ferrara, Italy© 2023 Kim, Franchin, Hong, Cha, Lim, Joo, Park, Yu, Lim, De Filippo, Gwon, Piroli, Kim, Wanha, Choi, Song, Patti, Nam, Bruno, Kang, Bocchino, De Ferrari, Koo and D’Ascenzo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Soon Jun Hong cHN5Y2hlOTRAaGFubWFpbC5uZXQ=

Specialty Section: This article was submitted to Coronary Artery Disease, a section of the journal Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.