- 1Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt

- 2Medical Research Center, Kateb University, Kabul, Afghanistan

Purpose: To evaluate the effect of polypills on the primary prevention of cardiovascular (CV) events using data from clinical trials.

Methods: We searched PubMed, Web of Science, EBSCO, and SCOPUS throughout May 2021. Two authors independently screened articles for the fulfillment of inclusion criteria. The RevMan software (version 5.4) was used to calculate the pooled risk ratios (RRs) and mean differences (MDs), along with their associated confidence intervals (95% CI).

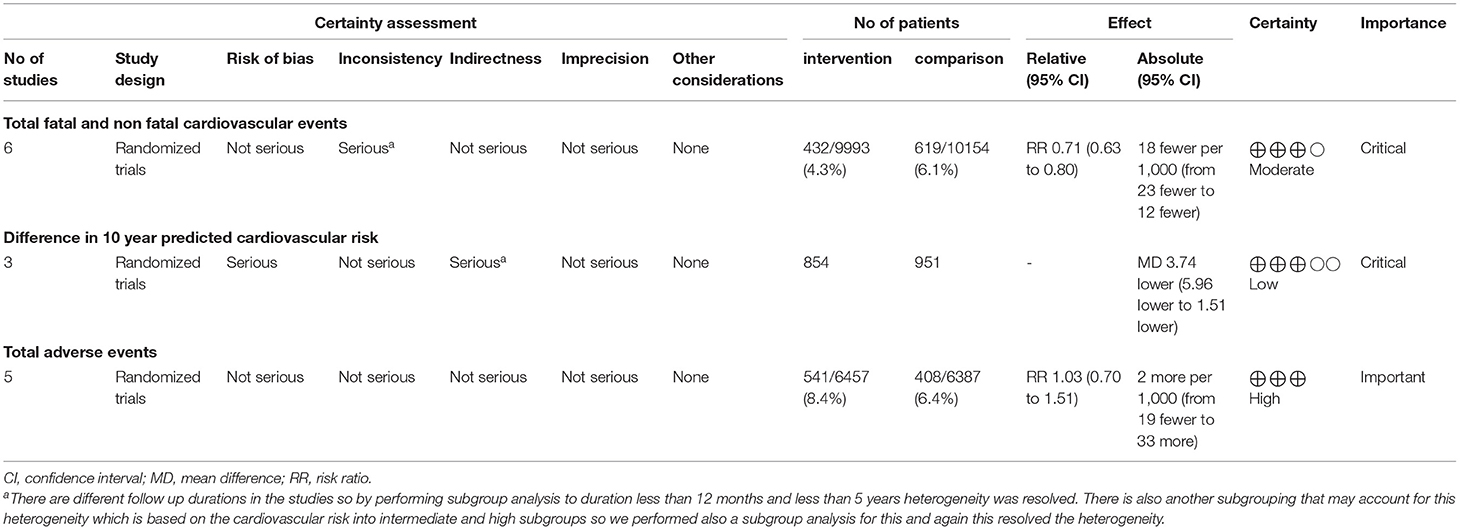

Results: Eight trials with a total of 20653 patients were included. There was a significant reduction in the total number of fatal and non-fatal CV events among the polypill group [RR (95% CI) = 0.71 (0.63, 0.80); P-value < 0.001]. This reduction was observed in both the intermediate-risk [RR (95% CI) = 0.76 (0.65, 0.89); P-value < 0.001] and high-risk [RR (95% CI) = 0.63 (0.52, 0.76); P-value < 0.001] groups of patients. Subgroup analysis was performed based on the follow-up duration of each study, and benefits were only evident in the five-year follow-up duration group [RR (95% CI) = 0.70 (0.62, 0.79); P-value < 0.001]. Benefits were absent in the one-year-or-less interval group [RR (95% CI) = 0.77 (0.47, 1.29); P-value = 0.330]. Additionally, there was a significant reduction in the 10-year predicted cardiovascular risk in the polypill group [MD (95% CI) = −3.74 (−5.96, −1.51); P-value< 0.001], as compared to controls.

Conclusion: A polypill regimen decreases the incidence of fatal and non-fatal CV events in patients with intermediate- and high- cardiovascular risk, and therefore may be an effective treatment for these patients.

Introduction

Globally, the prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) has almost doubled in the last 30 years, with CVD mortality increasing from 12.1 million cases in 1990 to 18.6 million cases in 2019. The leading cause of these numbers include suboptimal preventive methods and uncontrolled atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk factors (1, 2). To combat these issues, the World Heart Federation launched a global campaign to reduce premature mortality due to CVD by 25 percent by 2025 (3). In fact, Atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases are due to a chronic lifetime exposure of individuals to CVD risk factors such as high blood pressure levels (4). In 2003, Wald and Law coined the term polypill to describe a combination of active pharmaceutical components that had the potential to reduce the burden of cardiovascular diseases by more than 80% (5). The polypill has proven to increase adherence rates for secondary prevention, which is significant because roughly one third of people face adherence issues to blood pressure or lipid lowering medications, and that a large proportion of all CVD events (about 9% in Europe) is due to poor adherence to vascular medications alone (6, 7). However, the use of such a pill in primary prevention – especially for those with an intermediate to high risk of cardiovascular disease – is not well-understood, given that no studies have been performed to assess the long-term effectiveness of such an intervention (8). Intermediate risk is defined is defined by a Framingham score of 10–20% or an INTERHEART score of 10–15, while high risk is defined by a Framingham score of >20% or an INTERHEART score of >16. Despite its cost-effectiveness and ease of use, multiple drawbacks have hampered the wide scale prescription of polypills, most notably physician hesitancy and the inability to tailor doses according to patient needs (9). Trials were designed to investigate the benefits of polypill use, yet they generally assessed the improvement in CVD in terms of risk factors such as blood pressure and lipid profiles rather than clinical outcomes such as fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events (8). Moreover, these studies were usually performed in developing countries and could not be generalized to developed countries (10). New trials have since been published that account for such problems. Considering the newly published studies, the aim of this meta-analysis is to focus on assessing the effectiveness of polypills in preventing clinical outcomes as strokes and Myocardial infarctions and mortality rather than assessing their effect on lipid or blood pressure changes,such parameters have already been discussed in several previous studies so centered our attention on tangible clinical outcomes instead. We also discussed possible solutions to any drawbacks that this treatment might possess.

Methods

Search and Identification of Studies

A comprehensive literature search was carried out in May 2021 on the following databases: PUBMED, WOS, EBSCO, and SCOPUS. Search terms used were (polypill OR “fixed dose” OR “drug combination” OR “drug combinations”) AND (“heart outcomes prevention” OR “primary prevention” OR “Framingham score” OR “estimated 10-year cardiovascular risk”). Reviews and book chapters were excluded. Additional manual searches were performed through the “related articles” feature in PubMed. Lastly, all references from the reviewed articles were checked for any articles that might have been missed in the original literature search.

Selection Process and Inclusion Criteria

Once the searches were completed, the software programme Covidence was used to perform the de-duplication of citations and for the screening process. From the searches, two review authors (M.A, O.K) reviewed the title and abstract of each paper and retrieved potentially relevant references. Following this initial screening, we obtained the full text of potentially relevant studies, and the two authors (M.A, O.K) independently screened them using predetermined inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria are as follows: (1) trials that include the use of a fixed-dose combination of at least 2 drugs, one of them being a lipid lowering- and the other being a blood pressure lowering-drug; (2) trials that include (even if not limited to) primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with at least one cardiovascular risk factor or calculated cardiovascular risk score but no previous cardiovascular events; and (3) trials that either report the effect of the FDC on the incidence of cardiovascular events such as stroke or MI or that report the 10-year predicted cardiovascular risk (Framingham Score) after FDC use. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and a decision was reached after agreement between the reviewers. We only included trials in our meta-analysis and excluded any observational studies, case reports, and non-English articles.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the effect of Polypill on total fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events as Myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure or angina. Secondary outcomes were effect of polypill on the predicted 10-year cardiovascular risk for the studies which lacked data regarding our primary outcome, so the mean difference of the cardiovascular risk score was used as a predictor of these fatal and non-fatal CV events. The number of participants who discontinued treatment due to adverse effects and the total adverse events along with myalgia were also analyzed.

Data Extraction

Two review authors (O.K, M.A) independently extracted data and consulted the principal investigator when needed. They extracted details of the study design, participant characteristics, study setting, intervention, and comparator. They also extracted outcome data, which included the composite of death from cardiovascular causes and adverse events such as myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, resuscitated cardiac arrest, arterial revascularization, and angina. The study quality was assessed as part of the data extraction strategy with RoB 2 revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials. The tool is structured into a fixed set of domains of bias, focussing on trial's design, conduct, and reporting. In each domain, signaling questions elicit information about features of the trial that are relevant to risk of bias. A judgement about the risk of bias in each domain is generated based on answers to the signaling questions. Judgement can express ‘some concerns', be 'Low' or 'High' risk of bias (11). Quality of evidence was assessed using GRADE approach through tools on their website gradepro.

Statistical Analysis

A meta-analysis was carried out to evaluate the impact of a fixed-dose combination of lipid lowering and blood pressure lowering drugs, as compared to placebo or non-pharmacological intervention among participants without cardiovascular disease that were at an intermediate or high risk of developing CVD. RevMan 5.4 was used for statistical analysis. If we detected heterogeneity among studies (p-value <0.05), we used leave one out test or subgroup analysis to resolve the heterogeneity. We used fixed effects model if we observed no heterogeneity among studies, otherwise a random effects model was used if a significant heterogeneity was observed (p-value < 0.05). Our analysis followed the PRISMA Statement Checklist to ensure a high-quality review (12).

Results

Study Inclusion

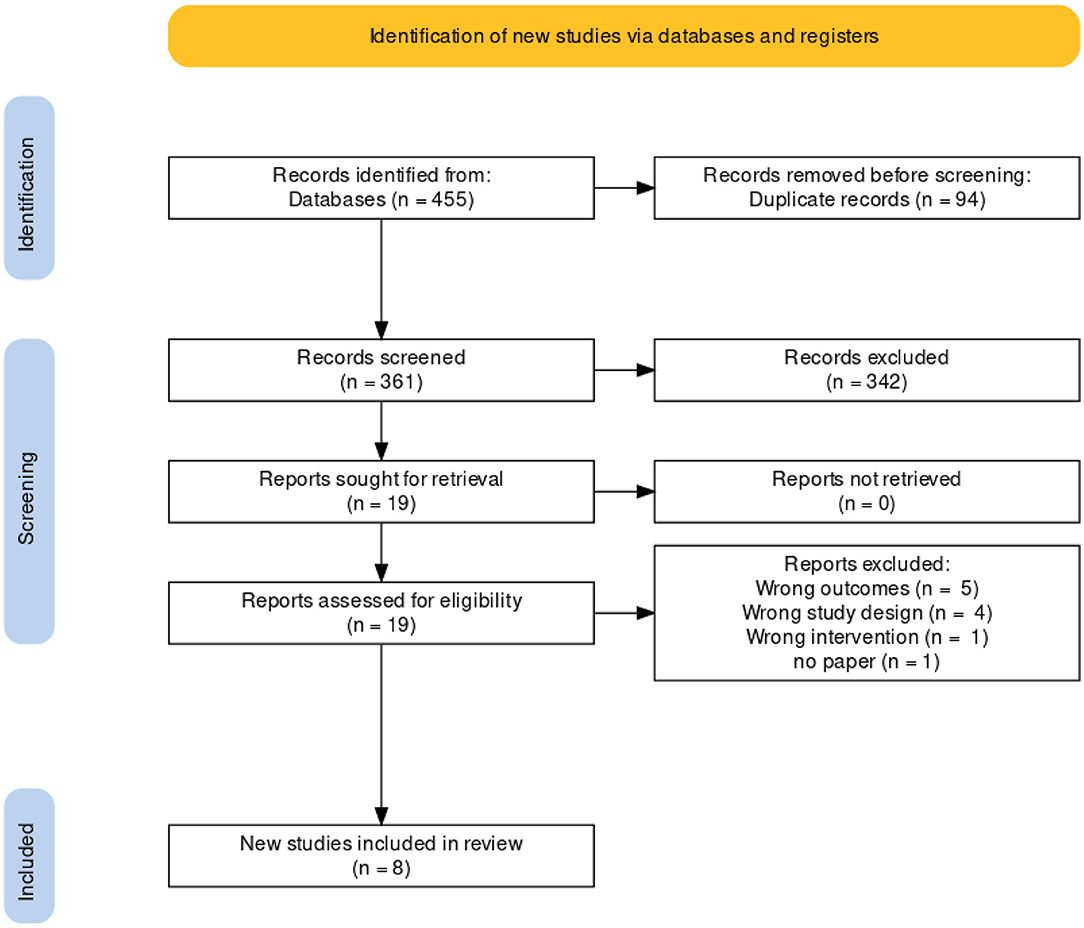

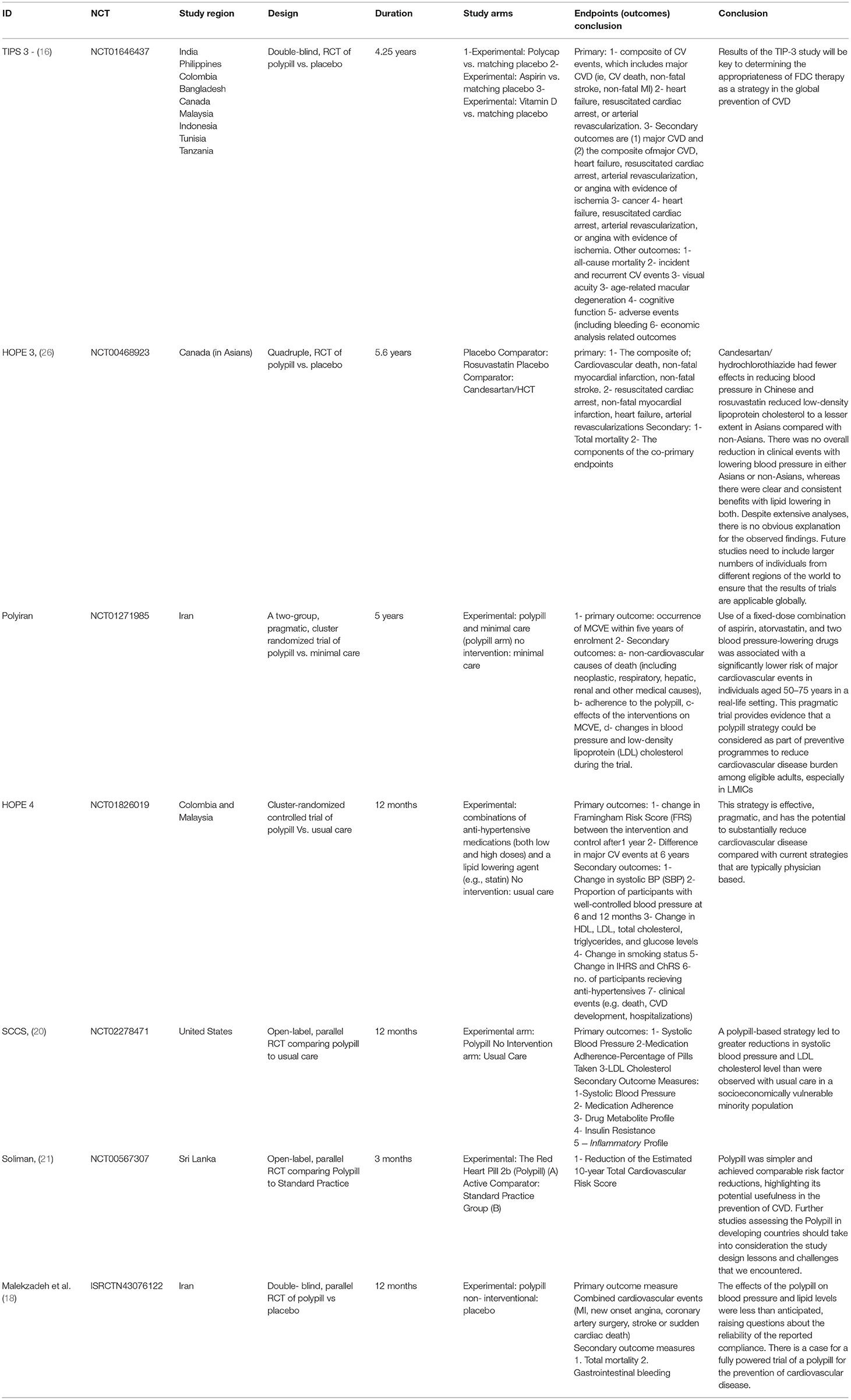

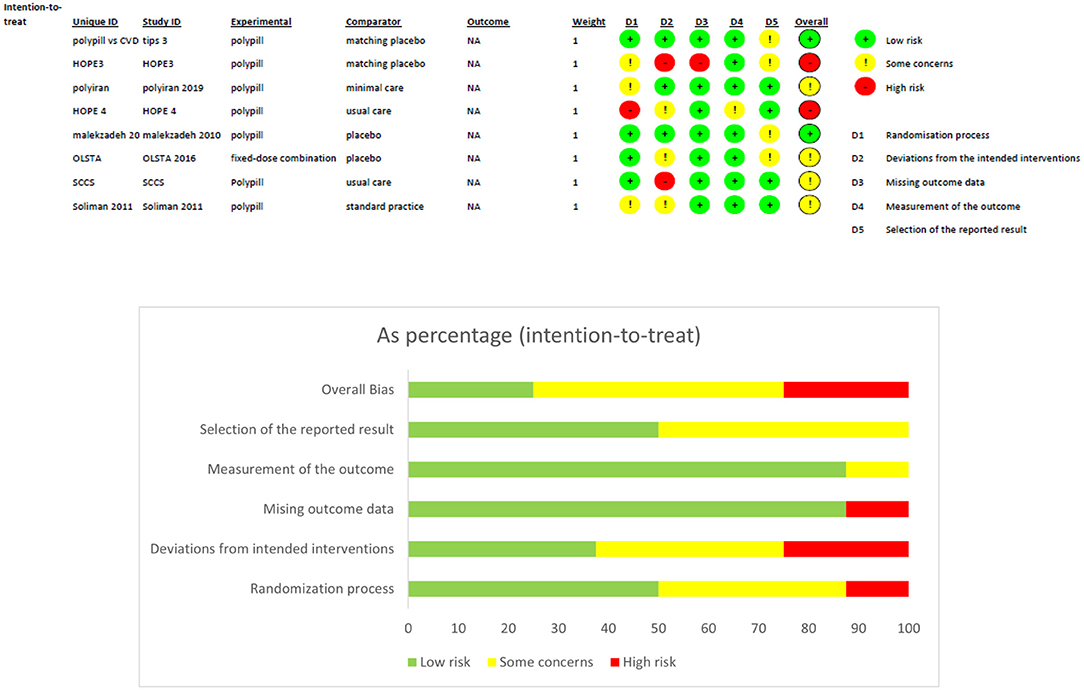

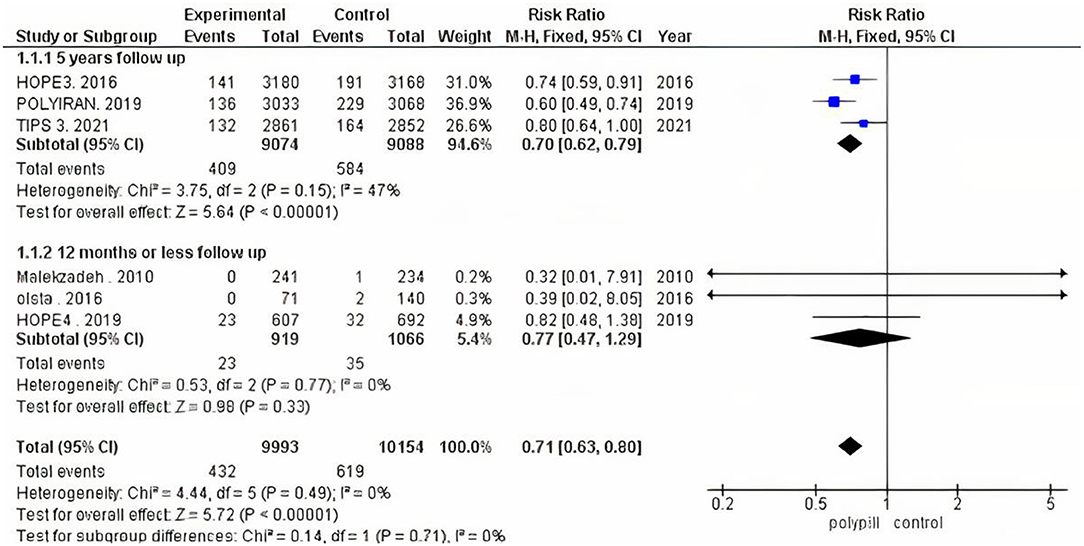

Four hundred and fifty five publications were extracted from literature search and, after the removal of duplicates, 361 moved on to the next stage of review. After title and abstract screening, 18 studies were eligible for a full-text review. Of these, eight studies were eligible for inclusion in our meta-analysis. A detailed description is illustrated in the PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1). Of the eight trials included, six contained data that compared the incidence of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events – such as stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, cardiovascular death, and revascularisation – between patients who received a polypill treatment and those who received placebos/minimal pharmacological care. Two studies did not contain information about CV events, so we instead compared the mean difference in the 10-year predicted cardiovascular risk between patients who received the polypill and patients who received placebos/minimal care. We were able to extract this outcome from a third study as well, so its results were included along with the other two in the Meta-Analysis. The summary and the risk of bias of the included studies are shown in Table 1 and Figure 2, respectively. The quality of evidence table is presented in Table 2.

Analyses

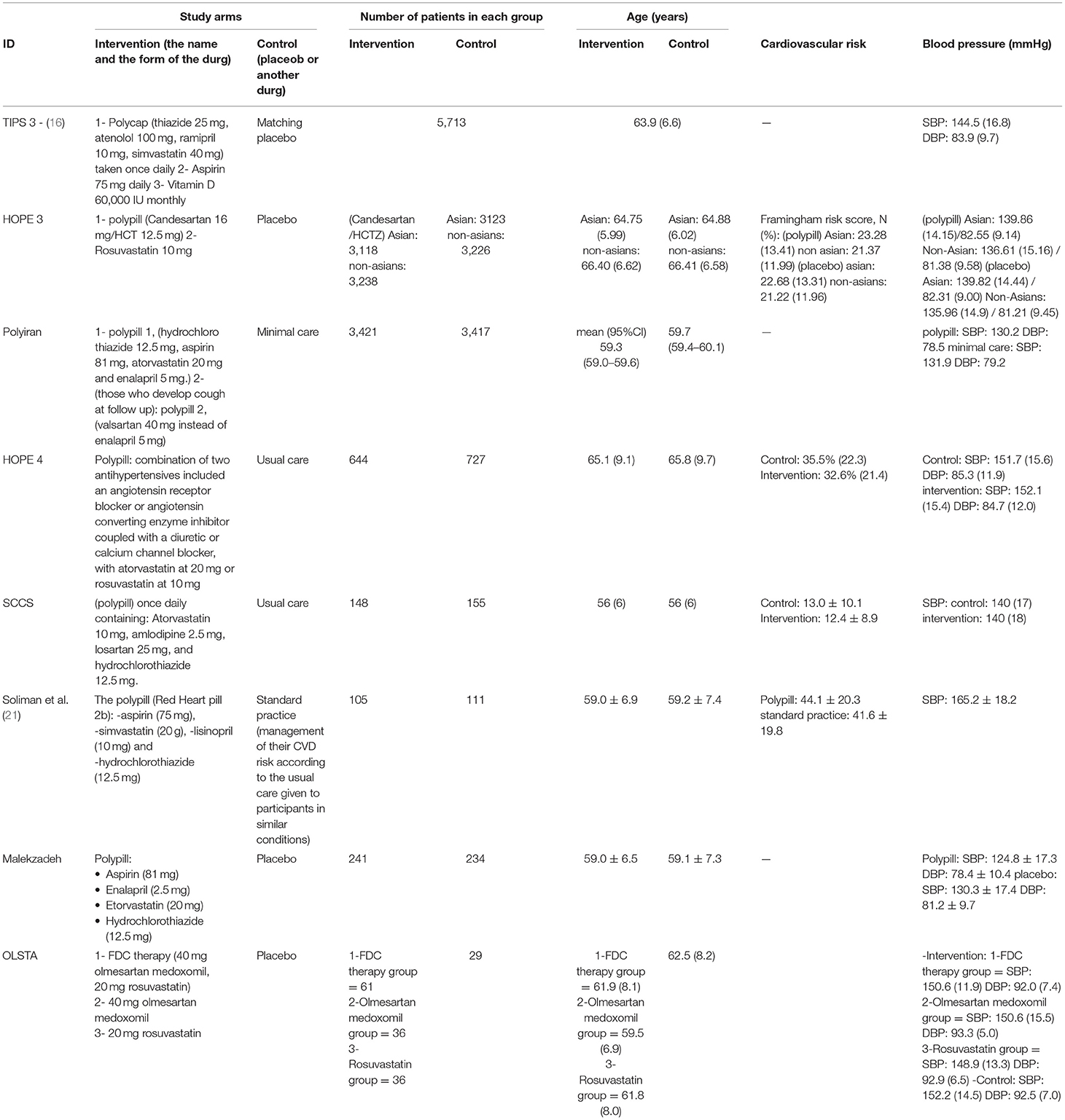

The total number of patients included in the polypill treatment group of our meta-analysis is 10,240, with a mean age of 61.1. The placebo/minimal care group included 10,413 patients, with a mean age of 61.38. Females represented 43.7% of the total study population, and males represented 56.4%. Detailed baseline characteristics are shown in Table 3.

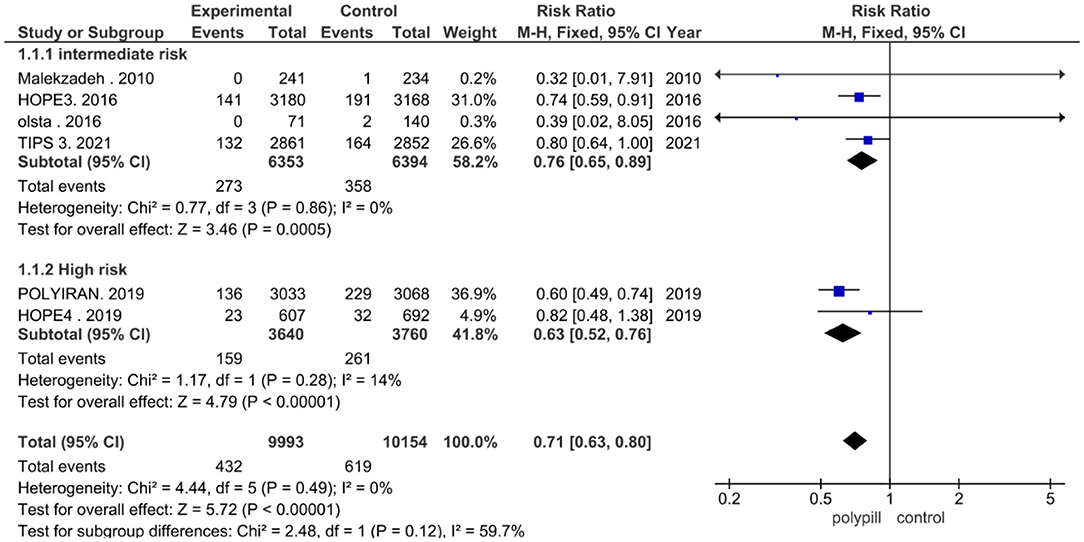

The total number of patients in the six included clinical trials with the outcome of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events is 20,147. Of the 9,993 who received a polypill, 432 experienced a fatal or non-fatal cardiovascular event, as compared to 619 out of 10,154 in the placebo/minimal care group. The pooled risk ratio for patients in the polypill treatment group was 0.71 (95% CI 0.63 to 0.80, p value > 0.00001), as compared to patients in the placebos/minimal care group. No publication bias was observed. We also found no statistically significant heterogeneity among the included studies (p = 0.49), as shown in Figure 3.

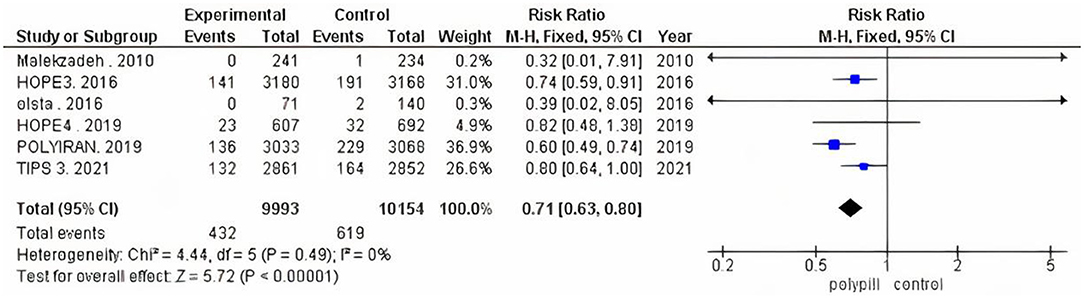

We performed subgroup analysis because trials varied according to their follow-up duration. We ran one analysis for the three trials that had a follow-up period of 12 months or less, and another analysis for the three that reported a 5-year follow-up period. The pooled risk ratio of the 12-months-or-less follow-up subgroup between patients who received the polypill treatment and patients who received minimal care was 0.77 (95% CI 0.47 to 1.29, p-value = 0.33). We found no statistically significant heterogeneity among the three studies (p = 0.77), as shown in Figure 4. The pooled risk ratio of the 5-year follow-up subgroup between patients who received the polypill treatment and patients who received placebos was 0.70 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.79, p-value < 0.00001). No statistically significant heterogeneity was found among the studies (p = 0.15), as shown in Figure 4.

We performed a third subgroup analysis, as four clinical trials studied patients with an intermediate risk of cardiovascular disease, while two trials studied patients with a high risk of cardiovascular disease. The pooled risk ratio between patients who received the polypill treatment and patients who received placebos/minimal care in the intermediate-risk subgroup was 0.76 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.89, p value = 0.0005). We found no statistically significant heterogeneity among the four studies (p = 0.86), as shown in Figure 5. The pooled risk ratio between patients who received the polypill treatment and patients who received placebos/minimal care in the high-risk subgroup was 0.63 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.76, p-value > 0.00001). No statistically significant heterogeneity was found between the studies (p = 0.28), as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Forest plot according to risk stratification: intermediate and high-risk patients subgroup analysis.

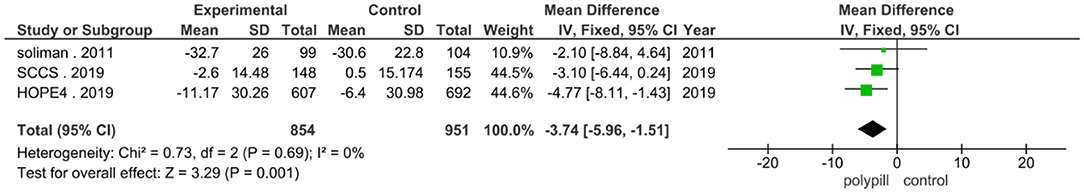

The total number of patients in the three trials that were analyzed for the difference in 10-year predicted cardiovascular disease risk is 1,805 (854 received the polypill treatment and 951 received placebos/minimal care). The pooled mean difference for patients in the polypill group was −3.74 (95% CI −5.96 to −1.51, p-value = 0.001), as compared to those in the minimal-care group. No statistically significant heterogeneity was found among the three included studies (p = 0.69), as shown in Figure 6.

Safety

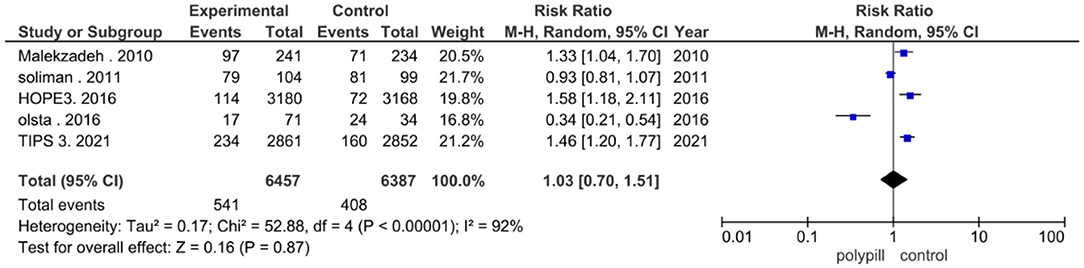

Five studies reported the total number of adverse events experienced by patients. Five hundred and forty one out of a total of 6,457 patients in the polypill group experienced adverse events, compared to 408 out of 6,387 patients in the minimal care/placebo group. The pooled risk ratio of total adverse events between patients who received the polypill treatment and patients who received minimal care/placebo was 1.03 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.51, p-value = 0.87). Statistically significant heterogeneity was found among the five studies, which was not resolved by using leave-one-out test (p < 0.00001), as shown in Figure 7.

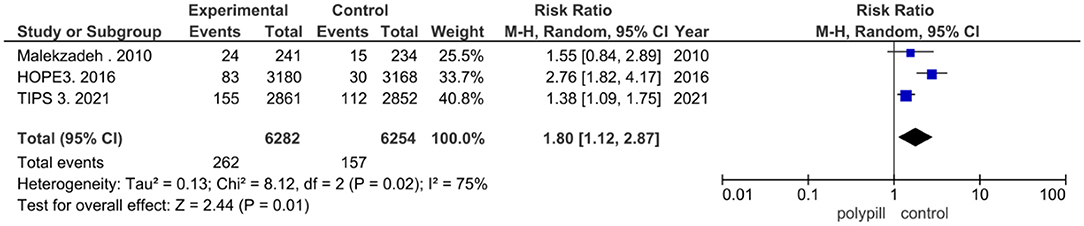

Discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events was reported in three of the eight clinical trials that were included in our meta-analysis. Two hundred and sixty two out of the 6,282 patients in the polypill group of these trials discontinued the polypill due to adverse events, while 157 in the placebo/minimal care group discontinued treatment due to adverse events. The pooled risk ratio of discontinuation due to adverse events between patients who received the polypill treatment and patients who received minimal care/placebo was 1.80 (95% CI 1.12 to 2.87, p-value = 0.01). We found statistically significant heterogeneity among the three studies), as shown in Figure 8, so we performed leave-one-out test by removing (26) study, and the heterogeneity was solved (p = 0.73) and the results were (RR = 1.40, [95% CI = 1.12 to 1.75], P = 0.003).

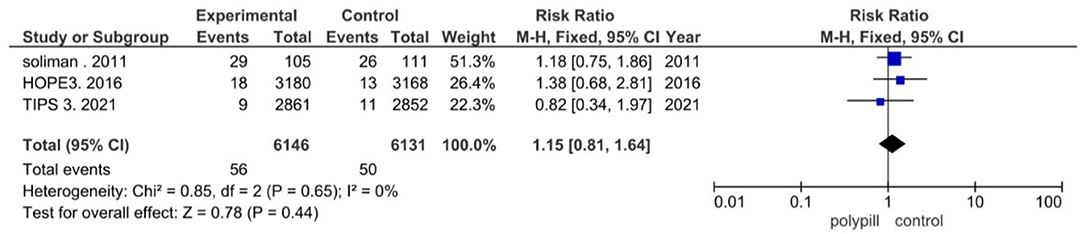

In the included clinical trials, myalgia was found to be the most reported adverse event. Three of the eight trials in our meta-analysis reported myalgia. Of the 6,146 patients in the polypill group of these three trials, myalgia was reported in 56 patients; of the 6,131 patients in the minimal care/placebo group, myalgia was reported in 50 patients. The pooled risk ratio of myalgia between patients who received the polypill treatment and patients who received minimal care/placebo was 1.15 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.64, p-value = 0.44). We found no statistically significant heterogeneity among the three trials (p = 0.65), as shown in Figure 9.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis suggests that a polypill regimen for primary prevention in patients with intermediate- to high- cardiovascular risk reduces the incidence of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular outcomes, including death from cardiovascular causes, myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, resuscitated cardiac arrest, arterial revascularization, and angina. Eight studies met inclusion criteria, wherein the pooled outcomes of 10,240 patients receiving a polypill were compared with 10,413 patients who did not receive a polypill. Previous studies revealed that the effect of the polypill on fatal and non-fatal ASCVD events was uncertain (8). This may have been due to low-quality evidence, since previous trials had a short duration and were not designed to assess the clinical outcome of the polypill (rather, the data used in analysis were mainly reported as adverse events). The previous trials had several disadvantages that were overcome in the trials included in our meta-analysis, and results could not be generalized because they were restricted to low income and non-developed countries. In our analysis, the HOPE 3 study included 21 countries throughout the world, such as the United States, Australia, and multiple countries in Europe. The TIPS 3 study also included patients from North America. Another major pitfall of previous trials was that they often reported the effect of the polypill on the CV risks themselves, such as blood pressure and blood lipid levels, rather than clinical outcomes. Again, this issue was resolved in our meta-analysis by several trials that were specifically designed to assess the effect of the polypill on a composite of CV deaths, MI, stroke, and revascularisation. In these studies, such as TIPS 3, HOPE 3, and PolyIran, we witnessed a pooled risk ratio between the polypill and comparator groups of 0.70 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.79, p-value > 0.00001). In studies that did not report these outcomes, we instead analyzed the 10-year predicted cardiovascular risk – for example, the SCCS and Soliman trials showed a significant −3.74 (95% CI −5.96 to −1.51, p-value = 0.001) mean difference between treatment and minimal care/placebo groups.

Interestingly, the efficacy of the polypill was witnessed in a phase 4 study performed on 1,193 patients in Mexico – the treatment showed even better-than-expected improvement of all-cause mortality and vascular-related mortality, as compared to a phase 3 trial, after the use of the CNIC-Ferrer polypill (22). Lastly, the problem of short trial duration – rendering the evidence of previous studies uncertain – was corrected by multiple trials in our analysis having a mean follow up of 5 years. Apart from the trial design of previous studies, the polypill treatment itself was flawed in multiple ways, with the inability to tailor dosage and individualize therapy as the most pressing issue. However, a range of different formulations and doses – as opposed to only one – might surmount this problem. Patients could potentially be stratified based on their risk scores, with a different formulation and different dose used in each stratum. Additionally, as was done in the TIPS 3 study, any patient who might still have uncontrolled blood pressure or dyslipidaemia could be prescribed additional medication. Another barrier of previous research was the agreement of patients to use a polypill while being asymptomatic, as well as their fear of adverse events while using pharmaceutically active components. However, an interview surveying Australian patients showed that they favored using a prophylactic approach (23). Our meta-analysis showed no significant difference in the total adverse events between the polypill and the comparator group (p = 87), which suggests that the polypill is safe to use as a preventive measure over long periods of time. The willingness of physicians to prescribe polypills to their patients was also considered, as many seemed reluctant about the risk-benefit ratio of such a treatment. This meta-analysis may therefore serve as evidence to convince hesitant physicians about the benefits of these fixed-dose combination drugs. The advantages of a polypill regimen, as proven by our meta-analysis, include a decrease in the incidence of fatal and non-fatal CV events. In addition, polypill treatment is cost effective (24, 25); however, cost reductions may still be required in some developing countries (26).

There are many areas of interest that require further study regarding polypill use in primary prevention for intermediate- and high- cardiovascular risk patients. Firstly, additional research is needed in order to determine the most convenient drug combination possible for the reduction of the incidence of ASCVD events. Secondly, polypill trials that stratify patients according to their cardiovascular risk score should be designed and conducted.

Implication for Future Practice

Evidence has shown that a risk-based strategy is better than a blood pressure-based approach or a combination (blood pressure and risk) strategy in terms of cardiovascular disease prevention (9). For that reason, we suggest that the prescription and use of a polypill be based upon risk scores, as shown in studies such as the TIPS 3, HOPE 4, and SCCS trials. Efficient CVD prevention should include the judicious use of evidence-based protocols, founded in the practices of risk-based management and a team approach. Strategies to reduce CVD should integrate socioenvironmental approaches and community resources into physician care, as well. This multidimensional treatment plan was successfully illustrated in the HOPE 4 study, which proved that a comprehensive model of care involving physicians and family substantially improved blood pressure control and reduced cardiovascular disease risk (13, 27).

Limitations of This Meta-Analysis

Due to the lack of clinical outcomes in some studies (such as the SCCS and Soliman trials), we had to utilize the difference in 10-year predicted cardiovascular risk as another assessment tool in our analysis.

Conclusion

A polypill that combines a lipid-lowering and blood pressure-lowering drug reduces the incidence of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events in patients with an intermediate and high risk of cardiovascular disease and could be used as a primary preventive approach in these patients. Limitations of previous studies regarding the polypill were all corrected by the results of the new trials that were included in this meta-analysis. The fear that the polypill may be a scattergun approach in primary prevention, leaving a rather asymptomatic population sentenced to lifelong treatment, was disproven by our study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

OK: design and concept and writing and review. KM: data analysis and interpretation. MA: data extraction. JS: review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. (2019) 140:e596–646. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

2. Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato G, Ammirati E, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: update from the GBD 2019 Study. J Am College Cardiol. (2020) 76:2982–3021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010

3. Dugani S, Gaziano TA. 25 by 25: Achieving global reduction in cardiovascular mortality. Current Cardiolo Reports. (2016). 18:10. doi: 10.1007/s11886-015-0679-4

4. Vasan RS, Massaro JM, Wilson PW, Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Levy D, et al. Antecedent blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham heart study. Circulation. (2002). 105:48–53. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101774

5. Wald NJ, Law MR. A strategy to reduce cardiovascular disease by more than 80%. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). (2003) 326:1419. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1419

6. Chowdhury R, Khan H, Heydon E, Shroufi A, Fahimi S, Moore C, et al. Adherence to cardiovascular therapy: a meta-analysis of prevalence and clinical consequences. Europ Heart J. (2013) 34:2940–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht295

7. Wald DS, Bestwick JP, Raiman L, Brendell R, Wald NJ. Randomised trial of text messaging on adherence to cardiovascular preventive treatment (INTERACT trial). PloS ONE. (2014) 9:e114268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114268

8. de Cates AN, Farr MR, Wright N, Jarvis MC, Rees K, Ebrahim S, et al. Fixed-dose combination therapy for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Sys. (2014) 4:CD009868. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009868.pub2

9. Roy A, Naik N, Srinath Reddy K. Strengths and limitations of using the polypill in cardiovascular prevention. Current Cardiol Reports. (2017) 19:45. doi: 10.1007/s11886-017-0853-y

10. Sukonthasarn A, Chia YC, Wang JG, Nailes J, Buranakitjaroen P, Van Minh H, et al. The feasibility of polypill for cardiovascular disease prevention in Asian Population. J Clin Hyperten (Greenwich, Conn.). (2021) 23:545–55. doi: 10.1111/jch.14075

11. Sterne J, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clin Res ed). (2019) 366:4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898

12. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Res ed.). (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

13. Kernan WN, Launer LJ, Goldstein LB. What is the future of stroke prevention?: debate: polypill vs. personalized risk factor modification. Stroke. (2010) 41(10 Suppl):S35–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.592022

14. Lonn EM, Bosch J, López-Jaramillo P, Zhu J, Liu L, Pais P, et al. Blood-pressure lowering in intermediate-risk persons without cardiovascular disease. N Eng J Med. (2016) 374:2009–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600175

15. Roshandel G, Khoshnia M, Poustchi H, Hemming K, Kamangar F, Gharavi A, et al. (2019). Effectiveness of polypill for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases (PolyIran): a pragmatic, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 394:672–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31791-X

16. Yusuf S, Joseph P, Dans A, Gao P, Teo K, Xavier D, et al. International polycap study 3 investigators. polypill with or without aspirin in persons without cardiovascular disease. N Eng J Med. (2021) 384:216–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028220

17. Park JS, Shin JH, Hong TJ, Seo HS, Shim WJ, Baek SH, et al. Efficacy and safety of fixed-dose combination therapy with olmesartan medoxomil and rosuvastatin in Korean patients with mild to moderate hypertension and dyslipidemia: an 8-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, factorial-design study (OLSTA-D RCT: OLmesartan rosuvaSTAtin from Daewoong). Drug Design, Develop Therap. (2016) 10:2599–609. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S112873

18. Malekzadeh F, Marshall T, Pourshams A, Gharravi M, Aslani A, Nateghi A, et al. A pilot double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial of the effects of fixed-dose combination therapy ('polypill') on cardiovascular risk factors. Int J Clin Prac. (2010) 64:1220–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02412.x

19. Schwalm JD, McCready T, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Yusoff K, Attaran A, Lamelas P, et al. A community-based comprehensive intervention to reduce cardiovascular risk in hypertension (HOPE 4): a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. (2019) 394:1231–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31949-X

20. Muñoz D, Uzoije P, Reynolds C, Miller R, Walkley D, Pappalardo S, et al. Polypill for cardiovascular disease prevention in an underserved population. N Eng J Med. (2019) 381:1114–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815359

21. Soliman EZ, Mendis S, Dissanayake WP, Somasundaram NP, Gunaratne PS, et al. A polypill for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a feasibility study of the world health organization. Trials. (2011) 12:3. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-3

22. Castellano JM, Verdejo J, Ocampo S, Rios MM, Gómez-Álvarez E, Borrayo G, et al. Clinical effectiveness of the cardiovascular polypill in a real-life setting in patients with cardiovascular risk: the SORS study. Archives Med Res. (2019) 50:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2019.04.001

23. Liu H, Massi L, Laba TL, Peiris D, Usherwood T, Patel A, et al. Patients' and providers' perspectives of a polypill strategy to improve cardiovascular prevention in Australian primary health care: a qualitative study set within a pragmatic randomized, controlled trial. Circ. Cardiovasc Quality Outcomes. (2015) 8:301–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.001483

24. Wald NJ, Luteijn JM, Morris JK, Taylor D, Oppenheimer P. Cost-benefit analysis of the polypill in the primary prevention of myocardial infarction and stroke. Europ J Epidemiol. (2016) 31:415–26. doi: 10.1007/s10654-016-0122-1

25. Newman J, Grobman WA, Greenland P. Combination polypharmacy for cardiovascular disease prevention in men: a decision analysis and cost-effectiveness model. Preventive Cardiol. (2008) 11:36–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1520-037x.2007.06423.x

26. Lamy A, Lonn E, Tong W, Swaminathan B, Jung H, Gafni A, et al. The cost implication of primary prevention in the HOPE 3 trial. Europ Heart J. Quality Care Clin Outcomes. (2019) 5:266–71. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcz001

Keywords: primary prevention, cardiovascular events, antihypertensives, polypill, lipid-lowering

Citation: Kandil OA, Motawea KR, Aboelenein MM and Shah J (2022) Polypills for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9:880054. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.880054

Received: 20 February 2022; Accepted: 08 March 2022;

Published: 14 April 2022.

Edited by:

Rajeev Gupta, Medicilinic, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Amrish Agrawal, Fujairah Hospital, United Arab EmiratesFady Gerges, Mediclinic Al Jowhara Hospital, United Arab Emirates

Copyright © 2022 Kandil, Motawea, Aboelenein and Shah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jaffer Shah, amFmZmVyLnNoYWhAa2F0ZWIuZWR1LmFm

Omneya A. Kandil

Omneya A. Kandil Karam R. Motawea

Karam R. Motawea Merna M. Aboelenein

Merna M. Aboelenein Jaffer Shah

Jaffer Shah