- 1Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Messina, Messina, Italy

- 2SunNutraPharma, Academic Spin-Off Company of the University of Messina, Messina, Italy

- 3Department of Neuroscience, IRCCS Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri, Milan, Italy

- 4Department of Health Promotion, Mother and Child Care, Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties “G. D'Alessandro”, PROMISE, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy

- 5Department of Internal Medicine, National Relevance and High Specialization Hospital Trust ARNAS Civico, Palermo, Italy

Beta (β)-blockers (BB) are useful in reducing morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure (HF) and concomitant chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Nevertheless, the use of BBs could induce bronchoconstriction due to β2-blockade. For this reason, both the ESC and GOLD guidelines strongly suggest the use of selective β1-BB in patients with HF and COPD. However, low adherence to guidelines was observed in multiple clinical settings. The aim of the study was to investigate the BBs use in older patients affected by HF and COPD, recorded in the REPOSI register. Of 942 patients affected by HF, 47.1% were treated with BBs. The use of BBs was significantly lower in patients with HF and COPD than in patients affected by HF alone, both at admission and at discharge (admission, 36.9% vs. 51.3%; discharge, 38.0% vs. 51.7%). In addition, no further BB users were found at discharge. The probability to being treated with a BB was significantly lower in patients with HF also affected by COPD (adj. OR, 95% CI: 0.50, 0.37–0.67), while the diagnosis of COPD was not associated with the choice of selective β1-BB (adj. OR, 95% CI: 1.33, 0.76–2.34). Despite clear recommendations by clinical guidelines, a significant underuse of BBs was also observed after hospital discharge. In COPD affected patients, physicians unreasonably reject BBs use, rather than choosing a β1-BB. The expected improvement of the BB prescriptions after hospitalization was not observed. A multidisciplinary approach among hospital physicians, general practitioners, and pharmacologists should be carried out for better drug management and adherence to guideline recommendations.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide (1). COPD is a multisystem disease often associated with several concomitant conditions and, in particular, with cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Moreover, the gradual progression of COPD results from a combination of risk factors (2–5). Actually, COPD-related mortality is probably underestimated because of the difficulty to ascribe death to a single cause (6): approximately 30% of deaths of patients with COPD is attributable to CVD and, in particular, to myocardial infarction and heart failure (HF) (7). Moreover, according to the Cardiovascular Health Study, the prevalence of COPD is greater in patients affected by HF than in not affected subjects (8, 9).

Beta (β)-blockers (BBs) are widely prescribed β-adrenergic blocking agents, useful in reducing morbidity and mortality in patients with COPD and concomitant CVD (10–12). Nevertheless, β-blockade could induce bronchoconstriction and worsen lung function in patients with COPD (13). Despite a common mechanism of action, BBs have a different selectivity for receptor subtypes (14). In fact, only non-cardioselective BBs are related to a high risk of obstructive airway disease exacerbations (12, 15–17). In addition, the use of the non-selective BB carvedilol is associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for HF in patients affected by COPD and HF and also with drug discontinuation compared to cardiac selective β1-receptor antagonist use (i.e., metoprolol, bisoprolol, or nebivolol) (18). Otherwise, different studies reported that the use of cardioselective BBs does not significantly increase the risk of COPD exacerbation (19–22).

As a consequence, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines suggest the safe and effective use of selective β1 BBs in patients with concurrent HF and respiratory diseases while strongly discouraging the use of non-selective BBs with vasodilating action like carvedilol (23, 24). Despite these evidences, few prescriptions of BBs were detected in patients affected by HF and concurrent COPD in multiple clinical settings; moreover, the pharmacological treatment with β1-selective BBs in this kind of patients appears to be underused (25–28), and a low adherence to clinical guidelines was observed (18).

The proper use of BBs, mainly in fragile patients such as older adults with HF and COPD, is essential even if the evidences are inadequate. The factors affecting BB prescription and selection are not well known. Additionally, few data on BB prescriptions are available, and Geriatric and Internal Medicine Departments represent a useful field of investigation to analyze older patients with comorbidities and in polypharmacy. Moreover, hospital admissions provide an opportunity to reevaluate treatments in patients with HF and COPD. In fact, a better familiarity with BBs and their contraindications by a hospital physician, in collaboration with a pharmacologist, could help identify appropriate preventive strategies for the management of these patients at discharge.

In the light of the above reasons, the aim of the study was to investigate the use and the appropriateness of different BBs in older patients affected by HF and HF/COPD, admitted to the internal medicine and geriatric wards and recorded in the REPOSI register.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Data Collection

All data concerning patients were extracted from the REPOSI Registry database. REPOSI is a collaborative and independent registry of the Italian Society of Internal Medicine (SIMI), the IRCCS Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research, and the Foundation of the IRCCS Cà Granda Maggiore Hospital in Milan. The introduction of the register was aimed at recruiting, monitoring, and evaluating older hospitalized patients aged 65 or more, admitted to 102 Italian internal medicine and geriatric wards. The register was established in 2008; information came from each single medical record and was collected every 2 years (29, 30). The main data collected include sociodemographic factors, laboratory data, comorbidities, and drug therapies. An encrypted code is used for each patient to comply with the law on the privacy of personal data. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of IRCCS Cà Grande Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico di Milano (approval number 43-2012).

For this study, all 4,713 patients recorded in the REPOSI Register between 2010 and 2016 were considered. Patients affected by HF and COPD were identified in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision (ICD-9-CM), as well as all other comorbidities. Drugs were classified according to ATC classification. The following clinical characteristics were evaluated: sex, age, BMI, indices of comorbidity and severity according to the cumulative disease assessment scales CIRS_C and CIRS_S (31, 32), mood disorders using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (33, 34), performance in basic activities of daily living, measured by the Barthel Index (BI) (35, 36), length of hospitalization, comorbidities, and mortality.

Drugs used up to the admission and drugs prescribed during hospitalization and discharge were considered separately. BBs were grouped in β1-selective BBs and non-selective BBs, according to β1-receptor selectivity. Indication of use was considered for each molecule. Contraindications to BB use were identified according to the summary of product characteristics (SPCs), for each BB, and patients with contraindicate prescriptions were evaluated. Patients without a BB treatment at admission and discharged with a BB prescription were considered new users; discontinuers and switchers were identified as patients using a BB at admission and discharged without a BB or with a different BB, respectively. Patients using the same BB at admission and discharge were considered continuers. Patients who died during the hospital stay were excluded from the evaluation of drugs prescribed at discharge.

Statistical Analyses

A descriptive analysis was performed to compare all the characteristics of the study population. All data were reported as absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables, while medians with interquartile range (Q1–Q3) were calculated for continuous variables. The Barthel and Geriatric Depression Scale was reported as binomial variables. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to evaluate the sample distribution. Due to the non-normal distribution of some variables, a non-parametric approach was adopted. The two-tailed Pearson's chi-squared test and the Mann–Whitney U test for independent samples were used to compare categorical or continuous variables, respectively. The McNemar test was applied to compare the frequencies of categorical variables between admission and discharge.

To assess the possible influence of all the considered characteristics of the study population on BB prescriptions and β1 selective BB choice, univariate logistic regression models were carried out using patients without BB or with non-selective BB prescriptions as comparators, both in patients affected by HF as a whole and in the subgroup of patients affected by HF and COPD.

All predictors identified in the univariate models were included in a stepwise multivariate logistic regression model (backward elimination procedure, α = 5%). Moreover, all variables that did not result in significant in the univariate analysis, but were considered clinically remarkable after a careful consideration based on current knowledge and clinical expertise, and with a cut-off of alpha error of 0.2 according to the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, were also included (37, 38). Conversely, variables with the same clinically significant and with a plausible collinearity, verified by the Spearman's rank correlation coefficient, were excluded from the multivariate model. Furthermore, in the subgroup of patients affected by HF and COPD, univariate logistic regression models were carried out to evaluate if the BB use influenced the probability of rehospitalization or death within 12 months from the admission.

Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were calculated for each covariate of interest in the univariate (crude OR) and multivariate (adjusted OR) models. The goodness of fit of the regression models was assessed by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test for adequacy. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

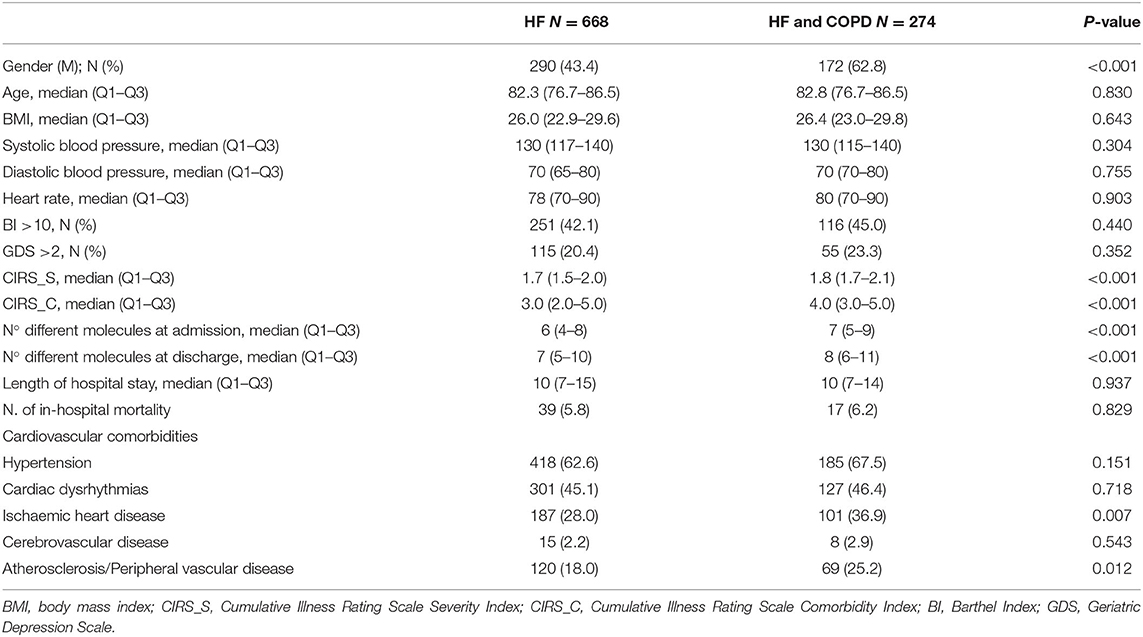

Of 4,713 patients recorded in the REPOSI register during the years 2010–2016, 942 (20.0%) were affected by HF. Of these, 274 (29.1%) also had COPD and 56 (5.9%) died during hospitalization. Patients with both HF and COPD were mostly men, with greater comorbidity indices (CIRS.S and CIRS.C) and were treated with more drugs, both at admission and at discharge, compared to patients affected by HF alone. In addition, more patients with HF and COPD were concomitantly affected by ischemic heart disease and atherosclerosis or peripheral vascular disease than patients affected by HF alone (Table 1). Heart rate (HR) resulted in <50 bpm in 6 out of 942 patients affected by HF, and exacerbation of COPD was reported as the cause of hospitalization in 25 out of 274 (9.1%) patients affected by HF and COPD.

Patients affected by HF and treated with at least one BB at admission were 444 (47.1%). Of them, 344 (77.5%) were continuers and 76 (17.1%) discontinued the therapy, while 24 (5.4%) died during hospital stay. At discharge, of 466 patients who were alive and had not previously been treated with BB, 79 (17.0%) new users were identified.

The use of BBs was significantly lower in patients with HF and COPD than in patients affected by HF alone, both at admission and at discharge (admission, 36.9% vs. 51.3%, p < 0.001; discharge, 38.1% vs. 51.7%, p < 0.001). Furthermore, no significant difference in BB users was observed between admission and discharge in both the HF and COPD affected patients (p = 0.864) and in those with HF alone (p = 0.999). BBs were used in 4 patients (2 non-selective BBs and 2 β1-selective BBs) admitted because of COPD exacerbation.

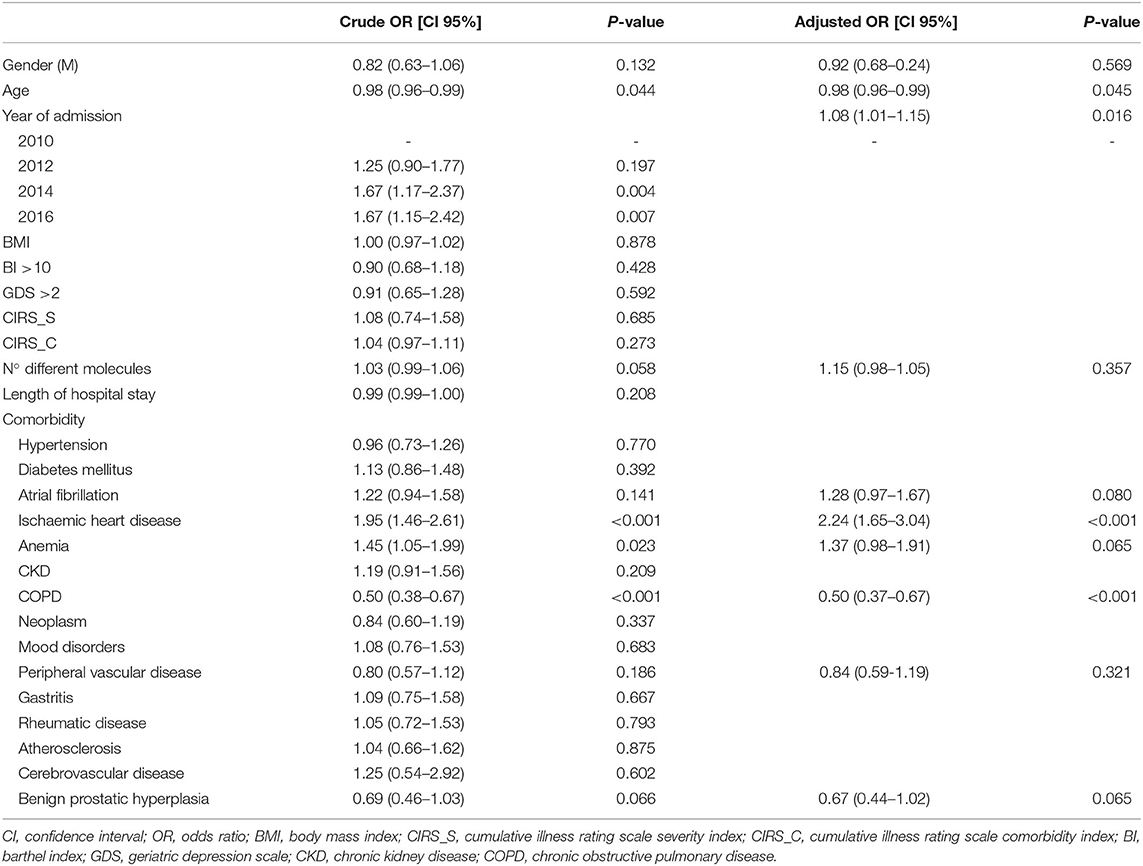

The probability of being treated with a BB significantly increased over time in patients affected by HF and ischemic heart disease. Furthermore, the probability of using a BB was significantly lower in patients with HF also affected by COPD (adjusted OR, 95% CI: 0.50, 0.37–0.67; p < 0.001) (Table 2). Moreover, in the subgroup of patients with HF and COPD, we observed an increased probability of being treated with a BB if also affected by ischemic heart disease (adjusted OR, 95% CI: 1.90, 1.12–3.23; p = 0.017), atrial fibrillation (adjusted OR, 95% CI: 1.96, 1.17–3.28; p = 0.011), and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (adjusted OR, 95% CI: 1.68, 1.01–2.80; p = 0.047). Conversely, BB use was inversely related to age (adjusted OR, 95% CI: 0.95, 0.92–0.99; p = 0.010). Rehospitalizations or deaths within 1 year occurred in 3 and 11 BB users, respectively, while 6 patients were rehospitalized, and 33 died within 1 year among patients not treated with BBs. In detail, the use of BBs reduced the probability of dying within 12 months (OR, 95% CI: 0.38, 0.18–0.78; p = 0.009) and the rehospitalizations (OR, 95% CI: 0.15, 0.03–0.91; p = 0.040) compared to non-users.

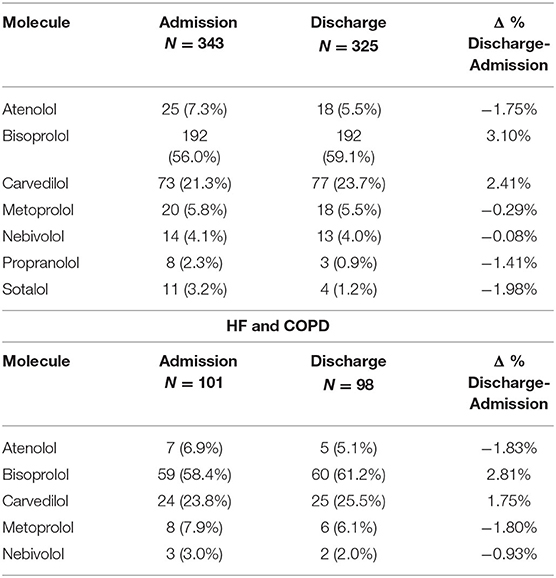

The 23.8% and 25.5% of patients with HF and COPD used a non-selective BB at admission and at discharge, respectively (p = 0.500). Furthermore, no significant differences were observed in β1-selective BB use between patients with HF and COPD or with HF alone, both at admission (73.2% vs. 76.2%, p = 0.538) and at discharge (74.2% vs. 74.5%, p = 0.947).

In addition, among patients affected by HF alone, 9 out of 92 users of non-selective BBs at admission (9.8%) switched to β1-selective BBs, while 7 out of 251 users of β1-selective BBs at admission (2.8%) switched to non-selective BBs at discharge. In patients affected by HF and COPD, no patients out of the 24 admitted with non-selective BBs switched to β1-selective BBs, whereas 2 out of 77 users of β1-selective BBs at admission (2.6%) switched to non-selective BBs at discharge.

Among the 79 new BB users at discharge, 61 were affected by HF alone and 18 by HF and COPD. A non-selective BB was chosen as starting treatment in 17 (27.9%) and 5 (27.8%) patients affected by HF alone or HF and COPD, respectively.

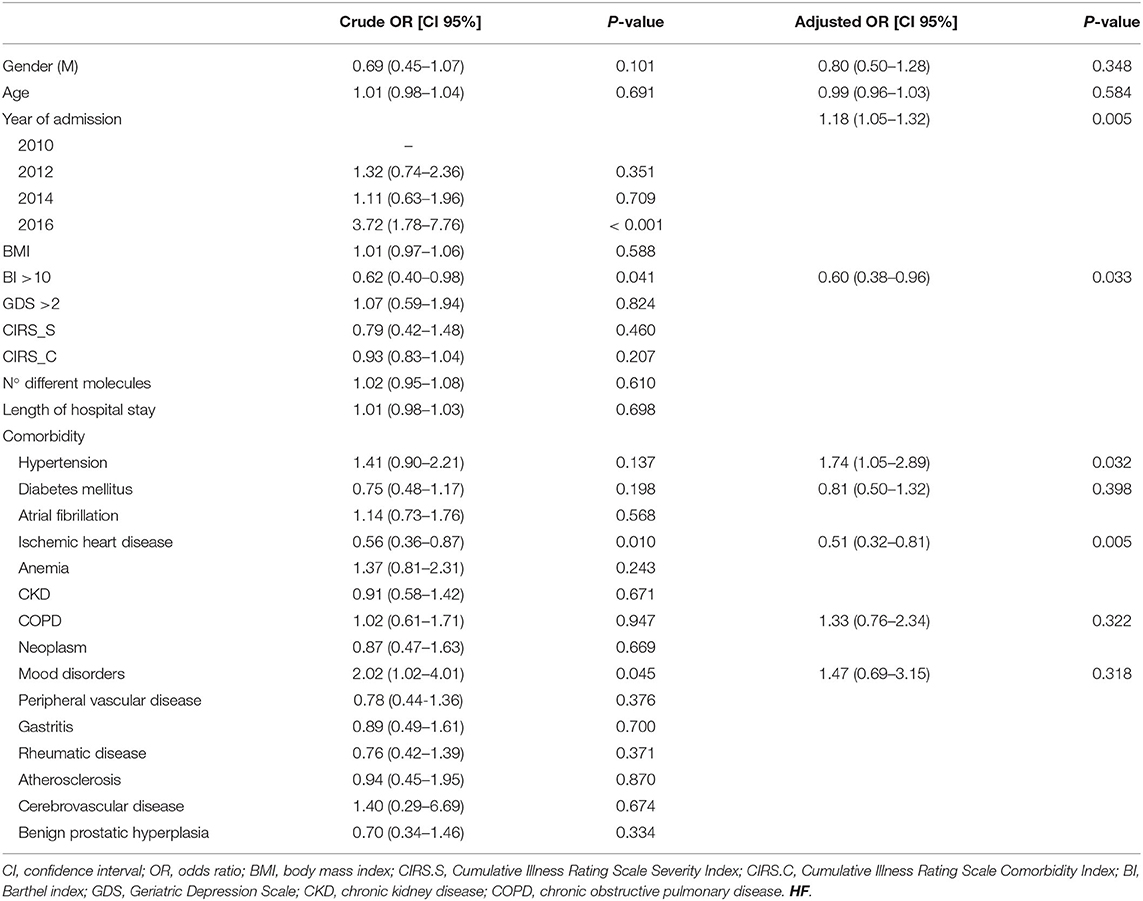

The probability of using a β1-selective BB in subjects with HF increased over time and in the presence of hypertension. Conversely, the likelihood of β1-selective BB use was significantly lower in patients with high BI and those with ischemic heart disease. The diagnosis of COPD was not significantly associated with the choice of BB type (adjusted OR, CI 95%: 1.33, 0.76–2.34; p = 0.322) (Table 3). Furthermore, no factors significantly influenced the use of β1-selective BB in the subgroup of patients affected by HF and COPD.

Table 3. Factors associated with β1-selective BB choice in patients affected by HF and treated with BBs.

Patients with HF were treated with 7 different BBs, while patients affected by HF and COPD used 5 different BBs. The most commonly used BB in both groups was bisoprolol at admission and at discharge. Carvedilol was the second most widely used BB in patients with HF and COPD. Furthermore, the use of bisoprolol increased at discharge both in the HF or HF and COPD affected patients (3.10% and 2.81, respectively) as well as the use of carvedilol (2.41% and 1.75%, respectively), while the use of other BBs decreased (Table 4).

Beta-blocker prescriptions were contraindicated in 49 (11.0%) BB users at admission and in 43 (10.9%) BB users at discharge. In particular, 23 (6.7%) and 17 (5.2%) patients with HF alone were treated with a contraindicated BB at admission and at discharge, respectively. In patients concomitantly affected by HF and COPD, contraindicated BB prescriptions resulted in 26 (25.7%) users at admission and 29 (29.6%) at discharge. Carvedilol was the main cause of inappropriate prescriptions in patients with HF and COPD. Moreover, in 11 patients at admission and 13 patients at discharge, the BB was contraindicated because of drug–drug interaction risk.

Discussion

The use of BBs was evaluated in hospitalized older patients affected by HF and COPD to implement the knowledge about the management of older patients enrolled in the REPOSI database (39, 40). First, HF prevalence was higher than in previous studies (41–43) because of the selection of a different population and diagnostic criteria (44). The prevalence of COPD ranged from 20% to 40% in patients affected by HF. These data were in accordance with our findings, which showed that approximately 30% of patients with HF also had COPD (45–49). Accordingly, the prevalence of HF and COPD increased in men and with age, likely because older patients are generally affected by additional comorbidities (50, 51), compared to patients affected by HF alone (49, 51–54). The high prevalence in men might be due to their increased aptitude to smoke (55); moreover, women have different symptoms and clinical presentation of COPD, and this could lead to an underdiagnosis in women; additionally, the diagnosis of COPD is often mainly difficult in HF with preserved ejection fraction, which most often affects women (56, 57).

Patients with both HF and COPD were treated with multiple drugs both at admission and at discharge than patients affected by HF alone. In fact, the presence of comorbidities could promote a therapeutic approach based on polytherapy, especially in older patients (58, 59); therefore, drug management gets complicated (60, 61).

Despite a clinical and pharmacological rationale suggesting the use of BBs in most of the patients with HF, in this study, fewer than half of the patients were admitted with a BB prescription and, surprisingly, no more BB users were observed after discharge. In fact, <20% of patients started a new BB treatment, while almost 20% of BB users discontinued the therapy after discharge. Moreover, in approximately 10% of BB users, prescriptions were contraindicated because of clinical conditions or drug–drug interactions, and no differences were observed between admission and discharge. Even hospital physicians in internal medicine and geriatrics wards did not properly address the treatment suggested by guidelines.

Although limited to a number of patients, the use of BBs in clinical practice has significantly been associated with a decreased risk of death and rehospitalizations. This confirms once again that beta-blockade is a crucial approach to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with HF, especially if they are concurrently affected by COPD (6). In fact, all HF guidelines and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines (23) strongly suggest BB therapy, but β1-selective. In fact, β-receptors blockade decreases the adrenergic hyperactivity occurring in an impaired heart (62) and reduces the risk of arrhythmias and progressive dysfunction of the left ventricle (63). Moreover, BBs improve heart function and, consequently, enhance the pulmonary hemodynamics by relieving symptoms of COPD; long-term use of BBs leads to a reduction in inflammation and pulmonary mucus secretion (64). However, β2-receptors blockade may lead to bronchoconstriction, thus worsening lung function (13); clinical trials highlighted the reduction in forced expiratory volume in the 1st second (FEV1), increased airway hyperresponsiveness, and reduced efficacy of bronchodilator therapy in patients treated with non-cardio-selective BB (17). Otherwise, cardio-selective β1-blockers' use is a safe approach and has a protective effect on all-cause mortality in patients with COPD (65, 66): neither evidence of adverse effects on respiratory function nor influence on efficacy of inhaled β2-agonists on bronchial smooth muscle were observed (67). Nevertheless, the often-unjustified rejection of BB use is a common attitude in clinical practice. The results obtained in this study were in agreement with others that confirmed the underuse of BBs in patients affected by HF and concomitant COPD compared to patients without COPD (10, 53, 68); these data were also relevant at hospital discharge with an increased gap of up to 15% in disfavor of COPD vs. patients with HF alone (69, 70). The limited prescription of BBs in this population is related to the onset of adverse respiratory effects mediated by β2-adrenoceptors blockade in the airways (71, 72).

Once again, the data obtained from the REPOSI register database showed that hospital physicians of internal medicine and geriatrics wards did not modify the treatment with BBs observed at admission; the number of BB users was significantly lower in patients affected by HF and COPD than in patients affected by HF alone; if affected by COPD, the probability of being treated with BBs was about half than that of patients affected by HF alone, and no differences were found at discharge. Moreover, in the subgroup of patients with HF and COPD, the concomitant diagnosis of ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and CKD was related to a higher use of BBs. A hospital physician prescribed more BBs in patients affected by several conditions for which the use of BBs is approved and is in accordance with guidelines, including ischemic heart disease and atrial fibrillation. On the other hand, the major prescription of BBs in patients affected by CKD is justified by the contraindication of other drugs indicated in HF, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-i) (73, 74).

Interestingly, the diagnosis of COPD did not influence the choice of BBs in patients with HF, with respect to other data, which suggest a greater use of β1-selective BBs in patients with concomitant COPD than those with HF alone (70). More than 25% of COPD-affected patients treated with a BB were admitted with a non-selective BB prescription, and no differences were observed at discharge. In fact, more contraindicated prescriptions were observed in patients concomitantly affected by HF and COPD than in HF alone, both at admission and at discharge; carvedilol use was the main cause of contraindicate prescriptions in this group of patients. Moreover, about 30% of new BB users were discharged with non-selective BB therapy regardless of COPD.

Current clinical guidelines suggest that metoprolol, bisoprolol, or nebivolol should be preferred in patients with HF and concurrent COPD (23). The most commonly used BB in our study was bisoprolol, followed by carvedilol, with an increase in prescriptions for both at discharge. This finding was different compared to that observed in another observational study, which described a low frequency of bisoprolol prescriptions (68). The use of cardio-selective BBs results in a favorable prognosis and decreased mortality (64, 75). In fact, carvedilol may cause a greater impairment in lung diffusion capacity than cardio-selective BBs due to the alveolar β2 blockade (76). Moreover, the β1-selective bisoprolol showed higher forced expiratory volume in 1 s than carvedilol (77), while carvedilol led to a higher risk of HF hospitalization (78) and, consequently, to COPD exacerbation than cardio-selective BBs (79). Nonetheless, a similar trend in prescriptions of carvedilol was found in several studies that reported that about one-third of patients affected by HF and COPD were treated with carvedilol (80, 81). This could be due to preference for carvedilol in patients affected by HF and milder airflow obstruction (70). However, this choice should be taking into account other comorbidities and co-medications of each patient that physician of internal medicine and geriatric wards had to be considered for the best management of patients affected by HF and concurrent COPD (82).

A discrepancy in prescribing BBs in patients with comorbidities has been observed in our study. The probability of being treated with a BB was significantly higher in patients affected by HF and concurrent ischemic heart disease, but the probability of choosing a β1-selective BB was significantly lower in this group of patients. In other studies, no substantial differences were shown for selective and non-selective BBs in the treatment of subjects with ischemic heart disease (83). Moreover, no clear scientific reasons support this choice; in fact, guidelines suggest the use of a BB without an intrinsic sympathomimetic activity, independently of its selectivity; for this reason, nebivolol should be avoided in patients affected by HF and ischemic heart disease (84, 85). The large number of studies highlighting the efficacy of carvedilol in reducing morbidity and mortality in patients affected by ischemic heart disease, and the poor amount of evidence concerning bisoprolol could have led physicians to choose carvedilol instead of other BBs in this group of patients (86).

In accordance with previous reports (28), hypertension did not increase total BB use in HF-affected patients; however, the probability of choosing a β1-selective BB significantly increased in this group of patients. Physicians preferred β1-selective BBs probably because the β2 adrenal-receptor antagonism reduces antihypertensive effectiveness due to the lack of peripheral vessels vasodilatation and the increased systolic blood pressure variability (87, 88).

In this study, the expected improvement of BB prescriptions after hospitalization was not observed. Largely, the hospital physician in the internal medicine and geriatrics wards takes care of quite complicated patients at the time of admission, especially the older patients affected by different chronic comorbidities, such as cardiovascular diseases (74, 89). In fact, these patients are often treated with several drugs and suffer from a multiorgan damage that could compromise their quality of life. Physicians probably minimize some evaluations by pharmacologists and, therefore, neglect, at least initially, concerns about the best choice of the drugs used during hospitalization. The role of clinical pharmacologist, which is very common in European Hospitals, becomes really important in the multidisciplinary management of patients affected by HF and concomitant COPD, especially for the treatments prescribed at discharge. Several studies have described the possible benefits of the pharmacologist-based intervention in terms of improved quality of life, increased medication appropriateness and adherence, reduction in hospitalization rates, and best management in primary care (90–93). The management of patients with multiple comorbidities and in polytherapy should be implemented not only in the hospital setting but also in the primary care, especially after discharge. Many therapies, including BB use, could be prescribed by general practitioners. Finally, as previously suggested (73, 94), a multidisciplinary approach among hospital physicians, general practitioners, and pharmacologists should be carried out for better drug management and better adherence to guideline recommendations.

The analysis of real-world data in older patients with a high grade of complexity, who are often not included in premarketing studies, is the major strength of this analysis. Moreover, the multicenter design based on the REPOSI register use with a large number of participating centers, which resulted in a wide sample of hospitalized older patients in internal medicine and geriatric wards, supports the novelty of our findings. Current evidence strongly promotes the hypothesis that pharmacological management of patients affected by HF and concomitant COPD should include the identification of other comorbidities and potentially co-medications. Moreover, a personalized care based on a multidisciplinary approach with the close collaboration of hospital physicians and pharmacologists has become really important in order to select the best and the most appropriate therapy. In addition, interventional educational programs may improve physicians' adherence to international guideline recommendations. Furthermore, this study provides an important overview of factors associated with the BB choice and, therefore, the BB use in a large cohort of older adults affected by HF and COPD, hospitalized in internal medicine and geriatric wards, in a long-time study period; moreover, it highlights differences in BB use between admission and discharge, underlining the hospital physicians' therapeutic approach. However, this observational study has some limitations: (i) no specific information on how the diagnosis of COPD was made (GOLD criteria or radiological criteria), and the severity of COPD was not reported in the REPOSI database and we could not analyze how much this affects the prescription, especially primary, of BB or their discontinuation. Similarly, we could not identify patients according to severity and characteristics of HF. (ii) REPOSI concerns only older hospitalized patients; therefore, these findings could not be extended to the general population. Moreover, our findings concern only Italian population, and additional evidences are required to be generalized to other nations.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated for this study will not be made publicly available. Further inquires can be directed to the author SC, c2FsdmF0b3JlLmNvcnJhb0B1bmlwYS5pdA==.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Participation was voluntary and all patients provided signed informed consent. REPOSI was approved by the ethics committees of the participating hospitals. The study was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

VA: conceptualization and writing original draft. FS and SC: writing original draft, writing—review and, editing. MR, MB, and GP: formal analysis. NI, AN, and GN: Validation. CA and GS: investigation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Investigators and coauthors of the REPOSI (REgistro POliterapie SIMI, Società Italiana di Medicina Interna) Study Group are as follows: Steering Committee: Pier Mannuccio Mannucci (Chair) (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano), Alessandro Nobili (co-chair) (Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, Milano), Antonello Pietrangelo (Presidente SIMI), Francesco Perticone (Past President SIMI), Giuseppe Licata (Socio d'onore SIMI), Francesco Violi (Policlinico Umberto I, Roma, Prima Clinica Medica), Gino Roberto Corazza (Reparto 11, IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo di Pavia, Pavia, Clinica Medica I), Salvatore Corrao (ARNAS Civico, Di Cristina, Benfratelli, PROMISE, Università di Palermo, Palermo), Alessandra Marengoni (Spedali Civili di Brescia, Brescia), Francesco Salerno (IRCCS Policlinico San Donato Milanese, Milano), Matteo Cesari (UO Geriatria, Università degli Studi di Milano), Mauro Tettamanti, Luca Pasina, and Carlotta Franchi (Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, Milano). Clinical data monitoring and revision: Carlotta Franchi, Laura Cortesi, Mauro Tettamanti, and Gabriella Miglio (Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, Milano). Database Management and Statistics: Mauro Tettamanti, Laura Cortesi, Ilaria Ardoino, and Alessio Novella (Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, Milano). Investigators: Domenico Prisco, Elena Silvestri, Giacomo Emmi, Alessandra Bettiol, and Irene Mattioli (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi Firenze, Medicina Interna Interdisciplinare); Gianni Biolo, Michela Zanetti, and Giacomo Bartelloni (Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Integrata di Trieste, Clinica Medica Generale e Terapia Medica); Massimo Vanoli, Giulia Grignani, and Edoardo Alessandro Pulixi (Azienda Ospedaliera della Provincia di Lecco, Ospedale di Merate, Lecco, Medicina Interna); Graziana Lupattelli, Vanessa Bianconi, and Riccardo Alcidi (Azienda Ospedaliera Santa Maria della Misericordia, Perugia, Medicina Interna); Domenico Girelli, Fabiana Busti, and Giacomo Marchi (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata di Verona, Verona, Medicina Generale e Malattie Aterotrombotiche e Degenerative); Mario Barbagallo, Ligia Dominguez, Vincenza Beneduce, and Federica Cacioppo (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico Giaccone Policlinico di Palermo, Palermo, Unità Operativa di Geriatria e Lungodegenza); Salvatore Corrao, Giuseppe Natoli, Salvatore Mularo, Massimo Raspanti, and Cristiano Argano (A.R.N.A.S. Civico, Di Cristina, Benfratelli, Palermo, UOC Medicina Interna ad Indirizzo Geriatrico-Riabilitativo); Marco Zoli, Maria Laura Matacena, Giuseppe Orio, Eleonora Magnolfi, Giovanni Serafini, and Angelo Simili (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico S. Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Unità Operativa di Medicina Interna); Giuseppe Palasciano, Maria Ester Modeo, and Carla Di Gennaro (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Consorziale Policlinico di Bari, Bari, Medicina Interna Ospedaliera L. D'Agostino, Medicina Interna Universitaria A. Murri); Maria Domenica Cappellini, Giovanna Fabio, Margherita Migone De Amicis, Giacomo De Luca, and Natalia Scaramellini (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Unità Operativa Medicina Interna IA); Matteo Cesari, Paolo Dionigi Rossi, Sarah Damanti, Marta Clerici, Simona Leoni, and Alessandra Danuta Di Mauro (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Geriatria); Antonio Di Sabatino, Emanuela Miceli, Marco Vincenzo Lenti, Martina Pisati, and Costanza Caccia Dominioni (IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo di Pavia, Pavia, Clinica Medica I, Reparto 11); Roberto Pontremoli, Valentina Beccati, Giulia Nobili, and Giovanna Leoncini (IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria San Martino-IST di Genova, Genova, Clinica di Medicina Interna 2); Luigi Anastasio, Lucia Sofia, and Maria Carbone (Ospedale Civile Jazzolino di Vibo Valentia, Vibo Valentia, Medicina interna); Francesco Cipollone, Maria Teresa Guagnano, and Ilaria Rossi (Ospedale Clinicizzato SS. Annunziata, Chieti, Clinica Medica); Gerardo Mancuso, Daniela Calipari, and Mosè Bartone (Ospedale Giovanni Paolo II Lamezia Terme, Catanzaro, Unità Operativa Complessa Medicina Interna); Giuseppe Delitala, Maria Berria, and Alessandro Delitala (Azienda ospedaliera-universitaria di Sassari, Clinica Medica); Maurizio Muscaritoli, Alessio Molfino, Enrico Petrillo, Antonella Giorgi, and Christian Gracin (Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza Università di Roma, Medicina Interna e Nutrizione Clinica Policlinico Umberto I); Giuseppe Zuccalà and Gabriella D'Aurizio (Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, Roma, Roma, Unità Operativa Complessa Medicina d'Urgenza e Pronto Soccorso); Giuseppe Romanelli, Alessandra Marengoni, Andrea Volpini, and Daniela Lucente (Unità Operativa Complessa di Medicina I a indirizzo geriatrico, Spedali Civili, Montichiari, Brescia); Antonio Picardi, Umberto Vespasiani Gentilucci, and Paolo Gallo (Università Campus Bio-Medico, Roma, Medicina Clinica-Epatologia); Giuseppe Bellelli, Maurizio Corsi, Cesare Antonucci, Chiara Sidoli, and Giulia Principato (Università degli studi di Milano-Bicocca Ospedale S. Gerardo, Monza, Unità Operativa di Geriatria); Franco Arturi, Elena Succurro, Bruno Tassone, and Federica Giofrè (Università degli Studi Magna Grecia, Policlinico Mater Domini, Catanzaro, Unità Operativa Complessa di Medicina Interna); Maria Grazia Serra and Maria Antonietta Bleve (Azienda Ospedaliera Cardinale Panico Tricase, Lecce, Unità Operativa Complessa Medicina); Antonio Brucato and Teresa De Falco (ASST Fatebenefratelli Sacco, Milano, Medicina Interna); Fabrizio Fabris, Irene Bertozzi, Giulia Bogoni, Maria Victoria Rabuini, and Tancredi Prandini (Azienda Ospedaliera Università di Padova, Padova, Clinica Medica I); Roberto Manfredini, Fabio Fabbian, Benedetta Boari, Alfredo De Giorgi, and Ruana Tiseo (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Sant'Anna, Ferrara, Unità Operativa Clinica Medica); Giuseppe Paolisso, Maria Rosaria Rizzo, and Claudia Catalano (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria della Seconda Università degli Studi di Napoli, Napoli, VI Divisione di Medicina Interna e Malattie Nutrizionali dell'Invecchiamento); Claudio Borghi, Enrico Strocchi, Eugenia Ianniello, Mario Soldati, Silvia Schiavone, and Alessio Bragagni (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico S. Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Unità Operativa di Medicina Interna Borghi); Carlo Sabbà, Francesco Saverio Vella, Patrizia Suppressa, Giovanni Michele De Vincenzo, Alessio Comitangelo, Emanuele Amoruso, and Carlo Custodero (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Consorziale Policlinico di Bari, Bari, Medicina Interna Universitaria C. Frugoni); Luigi Fenoglio and Andrea Falcetta (Azienda Sanitaria Ospedaliera Santa Croce e Carle di Cuneo, Cuneo, S. C. Medicina Interna); Anna L. Fracanzani, Silvia Tiraboschi, Annalisa Cespiati, Giovanna Oberti, and Giordano Sigon (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Medicina Interna 1B); Flora Peyvandi, Raffaella Rossio, Giulia Colombo, Pasquale Agosti (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, UOC Medicina generale Emostasi e trombosi); Valter Monzani, Valeria Savojardo, and Giuliana Ceriani (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Medicina Interna Alta Intensità); Francesco Salerno and Giada Pallini (IRCCS Policlinico San Donato e Università di Milano, San Donato Milanese, Medicina Interna); Fabrizio Montecucco, Luciano Ottonello, Lara Caserza, and Giulia Vischi (IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino e Università di Genova, Genova, Medicina Interna 1); Nicola Lucio Liberato and Tiziana Tognin (ASST di Pavia, UOSD Medicina Interna, Ospedale di Casorate Primo, Pavia); Francesco Purrello, Antonino Di Pino, and Salvatore Piro (Ospedale Garibaldi Nesima, Catania, Unità Operativa Complessa di Medicina Interna); Renzo Rozzini, Lina Falanga, Maria Stella Pisciotta, Francesco Baffa Bellucci, and Stefano Buffelli (Ospedale Poliambulanza, Brescia, Medicina Interna e Geriatria); Giuseppe Montrucchio, Paolo Peasso, Edoardo Favale, Cesare Poletto, Carl Margaria, and Maura Sanino (Dipartimento di Scienze Mediche, Università di Torino, Città della Scienza e della Salute, Torino, Medicina Interna 2 U. Indirizzo d'Urgenza); Francesco Violi and Ludovica Perri (Policlinico Umberto I, Roma, Prima Clinica Medica); Luigina Guasti, Luana Castiglioni, Andrea Maresca, Alessandro Squizzato, Leonardo Campiotti, Alessandra Grossi, and Roberto Davide Diprizio (Università degli Studi dell'Insubria, Ospedale di Circolo e Fondazione Macchi, Varese, Medicina Interna I); Marco Bertolotti, Chiara Mussi, Giulia Lancellotti, Maria Vittoria Libbra, Matteo Galassi, Yasmine Grassi, and Alessio Greco (Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena; Ospedale Civile di Baggiovara, Unità Operativa di Geriatria); Angela Sciacqua, Maria Perticone, Rosa Battaglia, and Raffaele Maio (Università Magna Grecia Policlinico Mater Domini, Catanzaro, Unità Operativa Malattie Cardiovascolari Geriatriche); Vincenzo Stanghellini, Eugenio Ruggeri, and Sara del Vecchio (Dipartimento di Scienze Mediche e Chirurgiche, Unità Operativa di Medicina Interna, Università degli Studi di Bologna/Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria S.Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna); Andrea Salvi, Roberto Leonardi, and Giampaolo Damiani (Spedali Civili di Brescia, U.O. 3a Medicina Generale); William Capeci, Massimo Mattioli, Giuseppe Pio Martino, Lorenzo Biondi, and Pietro Pettinari (Clinica Medica, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Ospedali Riuniti di Ancona); Riccardo Ghio and Anna Dal Col (Azienda Ospedaliera Università San Martino, Genova, Medicina III); Salvatore Minisola, Luciano Colangelo, Mirella Cilli, and Giancarlo Labbadia (Policlinico Umberto I, Roma, SMSC03 Medicina Interna A e Malattie Metaboliche dell'osso); Antonella Afeltra, Benedetta Marigliano, and Maria Elena Pipita (Policlinico Campus Biomedico Roma, Roma, Medicina Clinica); Pietro Castellino, Luca Zanoli, Alfio Gennaro, and Agostino Gaudio (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico V. Emanuele, Catania, Dipartimento di Medicina); Valter Saracco, Marisa Fogliati, and Carlo Bussolino (Ospedale Cardinal Massaia Asti, Medicina A); Francesca Mete and Miriam Gino (Ospedale degli Infermi di Rivoli, Torino, Medicina Interna); Carlo Vigorito and Antonio Cittadini, (Azienda Policlinico Universitario Federico II di Napoli, Napoli, Medicina Interna e Riabilitazione Cardiologica); Guido Moreo, Silvia Prolo, and Gloria Pina (Clinica San Carlo Casa di Cura Polispecialistica, Paderno Dugnano, Milano, Unità Operativa di Medicina Interna); Alberto Ballestrero, Fabio Ferrando, Roberta Gonella, and Domenico Cerminara (Clinica Di Medicina Interna ad Indirizzo Oncologico, Azienda Ospedaliera Università San Martino di Genova); Sergio Berra, Simonetta Dassi, and Maria Cristina Nava (Medicina Interna, Azienda Ospedaliera Guido Salvini, Garnagnate, Milano); Bruno Graziella, Stefano Baldassarre, Salvatore Fragapani, and Gabriella Gruden (Medicina Interna III, Ospedale S. Giovanni Battista Molinette, Torino); Giorgio Galanti, Gabriele Mascherini, Cristian Petri, and Laura Stefani (Agenzia di Medicina dello Sport, AOUC Careggi, Firenze); Margherita Girino and Valeria Piccinelli (Medicina Interna, Ospedale S. Spirito Casale Monferrato, Alessandria); Francesco Nasso, Vincenza Gioffrè, and Maria Pasquale (Struttura Operativa Complessa di Medicina Interna, Ospedale Santa Maria degli Ungheresi, Reggio Calabria); Leonardo Sechi, Cristiana Catena, Gianluca Colussi, Alessandro Cavarape, and Andea Da Porto (Clinica Medica, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria, Udine); Nicola Passariello and Luca Rinaldi (Presidio Medico di Marcianise, Napoli, Medicina Interna); Franco Berti, Giuseppe Famularo, and Patrizia Tarsitani (Azienda Ospedaliera San Camillo Forlanini, Roma, Medicina Interna II); Roberto Castello and Michela Pasino (Ospedale Civile Maggiore Borgo Trento, Verona, Medicina Generale e Sezione di Decisione Clinica); Gian Paolo Ceda, Marcello Giuseppe Maggio, Simonetta Morganti, Andrea Artoni, and Margherita Grossi (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria di Parma, U.O.C Clinica Geriatrica); Stefano Del Giacco, Davide Firinu, Giulia Costanzo, and Giacomo Argiolas (Policlinico Universitario Duilio Casula, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Cagliari, Cagliari, Medicina Interna, Allergologia ed Immunologia Clinica); Giuseppe Montalto, Anna Licata, and Filippo Alessandro Montalto (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico Paolo Giaccone, Palermo, UOC di Medicina Interna); Francesco Corica, Giorgio Basile, Antonino Catalano, Federica Bellone, and Concetto Principato (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico G. Martino, Messina, Unità Operativa di Geriatria); Lorenzo Malatino, Benedetta Stancanelli, Valentina Terranova, Salvatore Di Marca, Rosario Di Quattro, Lara La Malfa, and Rossella Caruso (Azienda Ospedaliera per l'Emergenza Cannizzaro, Catania, Clinica Medica Università di Catania); Patrizia Mecocci, Carmelinda Ruggiero, and Virginia Boccardi (Università degli Studi di Perugia-Azienda Ospedaliera S.M. della Misericordia, Perugia, Struttura Complessa di Geriatria); Tiziana Meschi, Andrea Ticinesi, and Antonio Nouvenne (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria di Parma, U.O Medicina Interna e Lungodegenza Critica); Pietro Minuz, Luigi Fondrieschi, and Giandomenico Nigro Imperiale (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Verona, Policlinico GB Rossi, Verona, Medicina Generale per lo Studio ed il Trattamento dell'Ipertensione Arteriosa); Mario Pirisi, Gian Paolo Fra, Daniele Sola, and Mattia Bellan (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Maggiore della Carità, Medicina Interna 1); Massimo Porta and Piero Riva (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino, Medicina Interna 1U); Roberto Quadri, Erica Larovere, and Marco Novelli (Ospedale di Ciriè, ASL TO4, Torino, S.C. Medicina Interna); Giorgio Scanzi, Caterina Mengoli, Stella Provini, and Laura Ricevuti (ASST Lodi, Presidio di Codogno, Milano, Medicina); Emilio Simeone, Rosa Scurti, and Fabio Tolloso (Ospedale Spirito Santo di Pescara, Geriatria); Roberto Tarquini, Alice Valoriani, Silvia Dolenti, and Giulia Vannini (Ospedale San Giuseppe, Empoli, USL Toscana Centro, Firenze, Medicina Interna I); Riccardo Volpi, Pietro Bocchi, and Alessandro Vignali (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria di Parma, Clinica e Terapia Medica); Sergio Harari, Chiara Lonati, Federico Napoli, and Italia Aiello (Ospedale San Giuseppe Multimedica Spa, U.O. Medicina Generale); Raffaele Landolfi, Massimo Montalto, Antonio Mirijello (Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli- Roma, Clinica Medica); Francesco Purrello and Antonino Di Pino (Ospedale Garibaldi Nesima Catania, U.O.C Medicina Interna); Silvia Ghidoni (Azienda Ospedaliera Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo, Medicina I); Teresa Salvatore, Lucio Monaco, and Carmen Ricozzi (Policlinico Università della Campania L. Vanvitelli, UOC Medicina Interna); Alberto Pilotto, Ilaria Indiano, and Federica Gandolfo (Ente Ospedaliero Ospedali Galliera Genova, SC Geriatria Dipartimento Cure Geriatriche, Ortogeriatria e Riabilitazione).

References

2. Soriano JB, Visick GT, Muellerova H, Payvandi N, Hansell AL. Patterns of comorbidities in newly diagnosed COPD and asthma in primary care. Chest. (2005) 128:2099–107. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2099

3. Fabbri LM, Luppi F, Beghé B, Rabe KF. Complex chronic comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J. (2008) 31:204–12. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00114307

4. García-Olmos L, Alberquilla Á, Ayala V, García-Sagredo P, Morales L, Carmona M, et al. Comorbidity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in family practice: A cross sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. (2013) 14:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-11

5. Feary JR, Rodrigues LC, Smith CJ, Hubbard RB, Gibson JE. Prevalence of major comorbidities in subjects with COPD and incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke: a comprehensive analysis using data from primary care. Thorax. (2010) doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.128082

6. Sin DD, Anthonisen NR, Soriano JB, Agusti AG. Mortality in COPD: role of comorbidities. Eur Respir J. (2006) 28:1245–57. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00133805

7. Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Murray RP. Smoking and lung function of lung health study participants after 11 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2002) 166:675–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2112096

8. Hawkins NM, Petrie MC, Jhund PS, Chalmers GW, Dunn FG, McMurray JJV. Heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: diagnostic pitfalls and epidemiology. Eur J Heart Fail. (2009) 11:130–9. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfn013

9. Kitzman DW, Gardin JM, Gottdiener JS, Arnold A, Boineau R, Aurigemma G, et al. Importance of heart failure with preserved systolic function in patients > or = 65 years of age. CHS research group cardiovascular health study. Am J Cardiol. (2001) 87:413–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(00)01393-X

10. Lim KP, Loughrey S, Musk M, Lavender M, Wrobel J. Beta-blocker under-use in COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. (2017) 12:3041–6. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S144333

11. Du Q, Sun Y, Ding N, Lu L, Chen Y. Beta-Blockers reduced the risk of mortality and exacerbation in patients with COPD: a meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e113048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113048

12. Short PM, Lipworth SIW, Elder DHJ, Schembri S, Lipworth BJ. Effect of β blockers in treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a retrospective cohort study. Bmj. (2011) 342:1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2549

13. Grieco MH, Pierson RN. Mechanism of bronchoconstriction due to beta adrenergic blockade. J Allergy Clin Immunology. (1971) 48:143–52. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(71)90009-1

14. do Vale GT, Ceron CS, Gonzaga NA, Simplicio JA, Padovan JC. Three generations of β-blockers: history, class differences and clinical applicability. Curr Hypertens Rev. (2019) 15:22–31. doi: 10.2174/1573402114666180918102735

15. Short PM, Anderson WJ, Williamson PA, Lipworth BJ. Effects of intravenous and oral β-blockade in persistent asthmatics controlled on inhaled corticosteroids. Heart. (2014) 100:219–23. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304769

16. Hawkins NM, MacDonald MR, Petrie MC, Chalmers GW, Carter R, Dunn FG, et al. Bisoprolol in patients with heart failure and moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Heart Fail. (2009) 11:684–90. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp066

17. van der Woude HJ, Zaagsma J, Postma DS, Winter TH, van Hulst M, Aalbers R. Detrimental effects of β-Blockers in COPD. Chest. (2005) 127:818–24. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.3.818

18. Sessa M, Mascolo A, Scavone C, Perone I, Di Giorgio A, Tari M, et al. Comparison of long-term clinical implications of beta-blockade in patients with obstructive airway diseases exposed to beta-blockers with different β1-adrenoreceptor selectivity: an Italian population-based cohort study. Front Pharmacol. (2018) 9:1212. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01212

19. Bhatt SP, Wells JM, Kinney GL, Washko GR, Budoff M, Kim Y, et al. β-Blockers are associated with a reduction in COPD exacerbations. Thorax. (2016) 71:8–14. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207251

20. Huang YL, Lai C-C, Wang Y-H, Wang C-Y, Wang J-Y, Wang H-C, et al. Impact of selective and nonselective beta-blockers on the risk of severe exacerbations in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. (2017) 12:2987–96. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S145913

21. Mersfelder TL, Shiltz DL. β-Blockers and the rate of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Ann Pharmacother. (2019) 53:1249–58. doi: 10.1177/1060028019862322

22. Baou K, Katsi V, Makris T, Tousoulis D. Beta blockers and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): sum of evidence. Curr Hypertens Rev. (2021) 17:196–206. doi: 10.2174/1573402116999201209203250

23. GOLD. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. (2021). p. 1–164.

24. Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, Carballo D, Koskinas KC, Bäck M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. (2021) 42:3227–337.

25. Egred M, Shaw S, Mohammad B, Waitt P, Rodrigues E. Under-use of beta-blockers in patients with ischaemic heart disease and concomitant chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. QJM. (2005) 98:493–7. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hci080

26. Lipworth B, Skinner D, Devereux G, Thomas V, Jie JLZ, Martin J, et al. Underuse of β-blockers in heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart. (2016) 102:1909–14. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309458

27. Pirina P, Martinetti M, Spada C, Zinellu E, Pes R, Chessa E, et al. Prevalence and management of COPD and heart failure comorbidity in the general practitioner setting. Respir Med. (2017) 131:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.07.059

28. Sessa M, Mascolo A, Mortensen RN, Andersen MP, Rosano GMC, Capuano A, et al. Relationship between heart failure, concurrent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and beta-blocker use: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail. (2018) 20:548–56. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1045

29. Argano C, Scichilone N, Natoli G, Nobili A, Corazza GR, Mannucci PM, et al. Pattern of comorbidities and 1-year mortality in elderly patients with COPD hospitalized in internal medicine wards: data from the RePoSI registry. Intern Emerg Med. (2021) 16:389–400. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10010086

30. Nobili A, Licata G, Salerno F, Pasina L, Tettamanti M, Franchi C, et al. Polypharmacy, length of hospital stay, and in-hospital mortality among elderly patients in internal medicine wards. the REPOSI study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. (2011) 67:507–19. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0977-0

31. Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. (1968) 16:622–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x

32. Corrao S, Natoli G, Nobili A, Mannucci PM, Pietrangelo A, Perticone F, et al. Comorbidity does not mean clinical complexity: evidence from the RePoSI register. Intern Emerg Med. (2020) 15:621–8. doi: 10.1007/s11739-019-02211-3

33. Hickie C, Snowdon J. Depression scales for the elderly: GDS, Gilleard, Zung. Clin Gerontol J Aging Ment Health. (1987) 6:51–3.

34. Argano C, Catalano N, Natoli G, Monaco M. Lo, Corrao S. GDS score as screening tool to assess the risk of impact of chronic conditions and depression on quality of life in hospitalized elderly patients in internal medicine wards. Medicine. (2021) 100:e26346. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000026346

35. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Md State Med J. (1965) 14:61–5. doi: 10.1037/t02366-000

36. Corrao S, Argano C, Natoli G, Nobili A, Corazza G, Mannucci P, et al. Sex-Differences in the pattern of comorbidities, functional independence, and mortality in elderly inpatients: evidence from the RePoSI register. J Clin Med. (2019) 8:81. doi: 10.3390/jcm8010081

37. Sun G-W, Shook TL, Kay GL. Inappropriate use of bivariable analysis to screen risk factors for use in multivariable analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. (1996) 49:907–16. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00025-X

38. VanderWeele TJ. Principles of confounder selection. Eur J Epidemiol. (2019) 34:211–9. doi: 10.1007/s10654-019-00494-6

39. Argano C, Scichilone N, Natoli G, Nobili A, Roberto G, Mannuccio P, et al. Pattern of comorbidities and 1 year mortality in elderly patients with COPD hospitalized in internal medicine wards : data from the RePoSI Registry. Intern Emerg Med. (2021) 16:389–400. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02412-1

40. Proietti M, Agosti P, Lonati C, Corrao S, Perticone F, Mannuccio P, et al. Hospital care of older patients with COPD : adherence to international guidelines for use of inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids. JAMDA. (2019) 20:1313–7.

41. Dharmarajan K, Rich MW. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and prognosis of heart failure in older adults. Heart Fail Clin. (2017) 13:417–26. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2017.02.001

42. Groenewegen A, Rutten FH, Mosterd A, Hoes AW. Epidemiology of heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. (2020) 22:1342–56. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1858

43. Orso F, Fabbri G, Pietro Maggioni A. “Epidemiology of heart failure,” Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. (2017) 243:15–33. doi: 10.1007/164_2016_74

44. Danielsen R, Thorgeirsson G, Einarsson H, Ólafsson Ö, Aspelund T, Harris TB, et al. Prevalence of heart failure in the elderly and future projections: the AGES-Reykjavík study. Scand Cardiovasc J. (2017) 51:183–9. doi: 10.1080/14017431.2017.1311023

45. Parissis JT, Andreoli C, Kadoglou N, Ikonomidis I, Farmakis D, Dimopoulou I, et al. Differences in clinical characteristics, management and short-term outcome between acute heart failure patients chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and those without this co-morbidity. Clin Res Cardiol. (2014) 103:733–41. doi: 10.1007/s00392-014-0708-0

46. Mentz RJ, Fiuzat M, Wojdyla DM, Chiswell K, Gheorghiade M, Fonarow GC, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized heart failure patients with systolic dysfunction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: findings from OPTIMIZE-HF. Eur J Heart Fail. (2012) 14:395–403. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs009

47. Kwon B-J, Kim D-B, Jang S-W, Yoo K-D, Moon K-W, Shim BJ, et al. Prognosis of heart failure patients with reduced and preserved ejection fraction and coexistent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur J Heart Fail. (2010) 12:1339–44. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq157

48. Pellicori P, Cleland JGF, Clark AL. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure: a breathless conspiracy. Heart Fail Clin. (2020) 16:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2019.08.003

49. Axson EL, Sundaram V, Bloom CI, Bottle A, Cowie MR, Quint JK. Temporal trends in the incidence of heart failure among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its association with mortality. Ann Am Thorac Soc. (2020) 17:939–48. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201911-820OC

50. Bosch L, Assmann P, de Grauw WJC, Schalk BWM, Biermans MCJ. Heart failure in primary care: prevalence related to age and comorbidity. Prim Health Care Res Dev. (2019) 20:e79. doi: 10.1017/S1463423618000889

51. Takabayashi K, Terasaki Y, Okuda M, Nakajima O, Koito H, Kitamura T, et al. The clinical characteristics and outcomes of heart failure patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from the Japanese community-based registry. Heart Vessels. (2021) 36:223–34. doi: 10.1007/s00380-020-01675-0

52. Lippi G, Sanchis-Gomar F. Global epidemiology and future trends of heart failure. AME Med J. (2020) 5:15–15. doi: 10.21037/amj.2020.03.03

53. Ehteshami-Afshar S, Mooney L, Dewan P, Desai AS, Lang NN, Lefkowitz MP, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from paradigm-hf. J Am Heart Assoc. (2021) 10:1–16. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.019238

54. Canepa M, Temporelli PL, Rossi A, Gonzini L, Nicolosi GL, Staszewsky L, et al. Pietro, Tavazzi L. prevalence and prognostic impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with chronic heart failure: data from the GISSI-HF trial. Cardiology. (2017) 136:128–37. doi: 10.1159/000448166

55. Aryal S, Diaz-Guzman E, Mannino DM. COPD and gender differences: an update. Transl Res. (2013) 162:208–18. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2013.04.003

56. Gutiérrez AG, Poblador-Plou B, Prados-Torres A, Laiglesia FJR, Gimeno-Miguel A. Sex differences in comorbidity, therapy, and health services' use of heart failure in Spain: evidence from real-world data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:2136. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17062136

57. Hopper I, Kotecha D, Chin KL, Mentz RJ, von Lueder TG. Comorbidities in heart failure: are there gender differences? Curr Heart Fail Rep. (2016) 13:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11897-016-0280-1

58. Nobili A, Marengoni A, Tettamanti M, Salerno F, Pasina L, Franchi C, et al. Association between clusters of diseases and polypharmacy in hospitalized elderly patients: results from the REPOSI study. Eur J Intern Med. (2011) 22:597–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.08.029

59. Schmidt IM, Hübner S, Nadal J, Titze S, Schmid M, Bärthlein B, et al. Patterns of medication use and the burden of polypharmacy in patients with chronic kidney disease: the German chronic kidney disease study. Clin Kidney J. (2019) 12:663–72. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfz046

60. Pirina P, Zinellu E, Martinetti M, Spada C, Piras B, Collu C, Fois AG. Treatment of COPD and COPD-heart failure comorbidity in primary care in different stages of the disease. Prim Health Care Res Dev. (2020) 21:e16. doi: 10.1017/S1463423620000079

61. Neder JA, Rocha A, Alencar MCN, Arbex F, Berton DC, Oliveira MF, Sperandio PA, Nery LE, O'Donnell DE. Current challenges in managing comorbid heart failure and COPD. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. (2018) 16:653–73 doi: 10.1080/14779072.2018.1510319

62. Lymperopoulos A. Physiology and pharmacology of the cardiovascular adrenergic system. Front Physiol. (2013) 4:240. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00240

63. Santulli G, Iaccarino G. Adrenergic signaling in heart failure and cardiovascular aging. Maturitas. (2016) 93:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.03.022

64. Yang YL, Xiang ZJ, Yang JH, Wang WJ, Xu ZC, Xiang RL. Association of β-blocker use with survival and pulmonary function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. (2020) 41:4415–22. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa793

65. Corrao S, Brunori G, Lupo U, Perticone F. Effectiveness and safety of concurrent beta-blockers and inhaled bronchodilators in COPD with cardiovascular comorbidities. Eur Respir Rev. (2017) 26:160123. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0123-2016

66. Etminan M, Jafari S, Carleton B, FitzGerald JM. Beta-blocker use and COPD mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. (2012) 12:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-12-48

67. Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE, Poole PJ, Cates CJ. Cardioselective beta-blockers for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis. Respir Med. (2003) 97:1094–101. doi: 10.1016/S0954-6111(03)00168-9

68. Su VYF, Chang YS, Hu YW, Hung MH, Ou SM, Lee FY, et al. Carvedilol, bisoprolol, and metoprolol use in patients with coexistent heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Medicine (United States). (2016) 95:10–5. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002427

69. Fisher KA, Stefan MS, Darling C, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Impact of COPD on the mortality and treatment of patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Chest. (2015) 147:637–45. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0607

70. Canepa M, Franssen FME, Olschewski H, Lainscak M, Böhm M, Tavazzi L, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic gaps in patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JACC: Heart Failure. (2019) 7:823–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.05.009

71. Leitao Filho FS, Choi L, Sin DD. Beta-blockers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the good, the bad and the ugly. Curr Opin Pulm Med. (2021) 27:125–31. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000748

72. Yang A, Yu G, Wu Y, Wang H. Role of β2-adrenergic receptors in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Life Sci. (2021) 265:118864. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118864

73. Barbieri MA, Rottura M, Cicala G, Mandraffino R, Marino S, Irrera N, et al. Chronic kidney disease management in general practice: a focus on inappropriate drugs prescriptions. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:1346. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051346

74. Arcoraci V, Barbieri MA, Rottura M, Nobili A, Natoli G, Argano C, et al. Kidney disease management in the hospital setting: a focus on inappropriate drug prescriptions in older patients. Front Pharmacol. (2021) 12: 749711. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.749711

75. Li XF, Mao YM. Beta blockers in COPD: a systematic review based on recent research. Life Sci. (2020) 252:117649. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117649

76. Contini M, Apostolo A, Cattadori G, Paolillo S, Iorio A, Bertella E, et al. Multiparametric comparison of CARvedilol, vs. NEbivolol, vs BIsoprolol in moderate heart failure: The CARNEBI trial. Int J Cardiol. (2013) 168:2134–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.277

77. Lainscak M, Podbregar M, Kovacic D, Rozman J, Von Haehling S. Differences between bisoprolol and carvedilol in patients with chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trial. Respir Med. (2011) 105:S44–9. doi: 10.1016/S0954-6111(11)70010-5

78. Sessa M, Rasmussen DB, Jensen MT, Kragholm K, Torp-Pedersen C, Andersen M. Metoprolol vs. carvedilol in patients with heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, and renal failure. Am J Cardiol. (2020) 125:1069–76. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.12.048

79. Paolillo S. Dell'Aversana S, Esposito I, Poccia A, Perrone Filardi P. The use of β-blockers in patients with heart failure and comorbidities: doubts, certainties and unsolved issues. Eur J Intern Med. (2021) 88:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.03.035

80. Mentz RJ, Wojdyla D, Fiuzat M, Chiswell K, Fonarow GC, O'Connor CM. Association of beta-blocker use and selectivity with outcomes in patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (from OPTIMIZE-HF). Am J Cardiol. (2013) 111:582–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.10.041

81. Canepa M, Straburzynska-Migaj E, Drozdz J, Fernandez-Vivancos C, Pinilla JMG, Nyolczas N, et al. Characteristics, treatments and 1-year prognosis of hospitalized and ambulatory heart failure patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the European society of cardiology heart failure long-term registry. Eur J Heart Fail. (2018) 20:100–10. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.964

82. Sessa M, Mascolo A, Rasmussen DB, Kragholm K, Jensen MT, Sportiello L, et al. Beta-blocker choice and exchangeability in patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an Italian register-based cohort study. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47967-y

83. Freemantle N, Cleland J, Young P, Mason J, Harrison J. β blockade after myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta regression analysis. Br Med J. (1999) 318:1730–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7200.1730

84. Pathak A, Mrabeti S. β-Blockade for patients with hypertension, ischemic heart disease or heart failure: where are we now? Vasc Health Risk Manag. (2021) 17:337–48. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S285907

85. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE, Ganiats TG, Holmes DR, et al. 2014 AHA/acc guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-Elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2014) 64:e139–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.017

86. DiNicolantonio JJ, Lavie CJ, Fares H, Menezes AR, O'Keefe JH. Meta-Analysis of carvedilol vs. beta 1 selective beta-blockers (Atenolol, Bisoprolol, Metoprolol, and Nebivolol). Am J Cardiol. (2013) 111:765–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.11.031

87. Wiysonge CS, Bradley HA, Volmink J, Mayosi BM, Opie LH. Beta-blockers for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2017) 1:CD002003 2017. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002003.pub5

88. Webb AJS, Fischer U, Rothwell PM. Effects of -blocker selectivity on blood pressure variability and stroke: a systematic review. Neurology. (2011) 77:731–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822b007a

89. Corrao S, Argano C, Nobili A, Marcucci M, Djade CD, Tettamanti M, et al. Brain and kidney, victims of atrial microembolism in elderly hospitalized patients? data from the REPOSI study. Eur J Intern Med. (2015) 26:243–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2015.02.018

90. van der Molen T, van Boven JFM, Maguire T, Goyal P, Altman P. Optimizing identification and management of COPD patients reviewing the role of the community pharmacist. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2017) 83:192–201. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13087

91. van Boven JFM, Stuurman-Bieze AGG, Hiddink EG, Postma MJ, Vegter S. Medication monitoring and optimization: a targeted pharmacist program for effective and cost-effective improvement of chronic therapy adherence. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. (2014) 20:786–92. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.8.786

92. Jarab AS, AlQudah SG, Khdour M, Shamssain M, Mukattash TL. Impact of pharmaceutical care on health outcomes in patients with COPD. Int J Clin Pharm. (2012) 34:53–62. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9585-z

93. Altowaijri A, Phillips CJ, Fitzsimmons D. A systematic review of the clinical and economic effectiveness of clinical pharmacist intervention in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. J Manag Care Pharm. (2013) 19:408–16. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.5.408

Keywords: COPD, heart failure, REPOSI register, clinical practice, beta-blockers

Citation: Arcoraci V, Squadrito F, Rottura M, Barbieri MA, Pallio G, Irrera N, Nobili A, Natoli G, Argano C, Squadrito G and Corrao S (2022) Beta-Blocker Use in Older Hospitalized Patients Affected by Heart Failure and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: An Italian Survey From the REPOSI Register. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9:876693. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.876693

Received: 15 February 2022; Accepted: 05 April 2022;

Published: 16 May 2022.

Edited by:

Maurizio Sessa, University of Copenhagen, DenmarkReviewed by:

Nina Karoli, Saratov State Medical University, RussiaAndre Rodrigues Duraes, Federal University of Bahia, Brazil

Chenxi Song, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, China

Copyright © 2022 Arcoraci, Squadrito, Rottura, Barbieri, Pallio, Irrera, Nobili, Natoli, Argano, Squadrito and Corrao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vincenzo Arcoraci, dmluY2Vuem8uYXJjb3JhY2lAdW5pbWUuaXQ=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Vincenzo Arcoraci

Vincenzo Arcoraci Francesco Squadrito

Francesco Squadrito Michelangelo Rottura

Michelangelo Rottura Maria Antonietta Barbieri

Maria Antonietta Barbieri Giovanni Pallio

Giovanni Pallio Natasha Irrera

Natasha Irrera Alessandro Nobili

Alessandro Nobili Giuseppe Natoli4

Giuseppe Natoli4