95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Cardiovasc. Med. , 04 March 2022

Sec. Thrombosis and Haemostasis

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.841341

This article is part of the Research Topic Anticoagulation in Cardiovascular Diseases: Evolving role, unmet needs and grey areas View all 26 articles

Background: Several studies have investigated the effect of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in Latin American patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), but the results remain controversial. Therefore, we aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of DOACs vs. warfarin in Latin American patients with AF.

Methods: We systematically searched the PubMed and Embase databases until November 2021 for studies that compared the effect of DOACs vs. warfarin in Latin patients with AF. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs were pooled by a random-effects model using an inverse variance method.

Results: Four post-hoc analyses of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) involving 42,411 DOACs and 29,270 warfarin users were included. In Latin American patients with AF, for the effectiveness outcomes, the use of DOACs compared with warfarin was significantly associated with decreased risks of stroke or systemic embolism (SSE) (HR = 0.78; 95%CI.64–0.96), stroke (HR = 0.75; 95%CI.57–0.99), hemorrhagic stroke (HR = 0.14; 95%CI.05–0.36), all-cause death (HR = 0.89; 95% CI.80–1.00), but not ischemic stroke and cardiovascular death. For the safety outcomes, compared with warfarin, the use of DOACs was associated with reduced risks of major or non-major clinically relevant (NMCR) bleeding (HR = 0.70; 95% CI.57–0.86), major bleeding (HR = 0.70; 95%CI.53–0.92), intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) (HR = 0.42; 95%CI.24–0.74), or any bleeding (HR = 0.70;95% CI.62–0.78), but not gastrointestinal bleeding. In non-Latin American patients with AF, for the effectiveness outcomes, the use of DOACs compared with warfarin was significantly associated with decreased risks of SSE (HR = 0.87; 95%CI.75–1.00), hemorrhagic stroke (HR = 0.41; 95%CI.28–0.60), cardiovascular death (HR = 0.87; 95% CI.81–0.94), all-cause death (HR = 0.90; 95% CI.85–0.94). Conversely, the risk of myocardial infarction increased (HR = 1.34; 95% CI 1.13–1.60), but not ischemic stroke. For the safety outcomes, compared with warfarin, the use of DOACs was associated with reduced risks of major or NMCR bleeding (HR = 0.75; 95%CI.61–0.92), major bleeding (HR = 0.76; 95%CI.63–0.92), ICH (HR = 0.42; 95%CI.36–0.52), and any bleeding (HR = 0.81; 95% CI.71–0.92), but not gastrointestinal bleeding.

Conclusion: Current pooled data from the four post-hoc analyses of RCTs suggested that compared with warfarin, DOACs appeared to have significant reductions in SSE, stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, all-cause death, major or NMCR bleeding, major bleeding, ICH, and any bleeding, but comparable risks of ischemic stroke, cardiovascular death, and gastrointestinal bleeding in Latin American patients with AF. DOACs appeared to have significant reductions in SSE, hemorrhagic stroke, all-cause death, cardiovascular death, major or NMCR bleeding, major bleeding, ICH, and any bleeding, and increased the risk of myocardial infarction, but comparable risks of stroke, ischemic stroke, and gastrointestinal bleeding in non-Latin American patients with AF.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia in adults. The currently estimated prevalence of AF in adults ranges from 2 to 4%, and a 2.3-fold rise is expected due to the longevity in the general population and the increased screening of patients with previously undiagnosed AF (1). Advanced age is widely regarded as a foremost risk factor, but increasing burden of other comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, obesity, and obstructive sleep apnea also contributes to the higher prevalence of AF. Not only that, many modifiable risk factors are potent contributors to AF development and progression (2). Many cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications, such as 5-fold rise in stroke and 2 times the risk of mortality, are prevalently screened in patients with AF (3). AF-associated thromboembolic events are lead contributors for the poor prognosis in patients with AF, which involves higher morbidity and mortality (4, 5). Antithrombotic therapy effectively reduces the incidence of embolism in patients with AF. Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have superior effectiveness and safety outcome for the prevention of stroke and thromboembolic events in patients with AF (6). DOACs are recommended as preferred alternatives to warfarin in the American College of Cardiology and/or American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society (7) and European Society of Cardiology guidelines (8) due to its superior characteristics in effectiveness, safety, and convenience, especially for elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome or chronic kidney disease (9, 10). Important differences in clinical characteristics, response to treatment, and outcomes of patients with AF distribute to the diverse regions of the world. In Latin America, AF is regarded as a considerable cause of high mortality and disability (11). Although prevalence data is limited, the incidence of AF-related stroke and associated morbidity is increasing in this region (12), and anticoagulation is underused (13). Therefore, patients with AF in Latin America undergo higher risk of death and thromboembolic events due to the aging population and poorly managed risk factors of AF, such as hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, etc. The anticoagulant treatment of patients with AF is particularly significant in Latin America.

Several previously published studies demonstrated that patients with AF in Latin America treated with warfarin had higher adjusted mortality rates and incidence of stroke and/or systemic embolism, intracranial hemorrhage, and life-threatening or fatal bleeding compared with patients with AF in the rest of the world (ROW) (14). Data regarding the effectiveness and safety outcome of anticoagulation regimens in this region is insufficient. Although several new post-hoc analyses of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) well-examined the association between regions (Latin America vs. non-Latin America) and effectiveness and safety outcomes, even explored the use of individual DOACs compared with warfarin in Latin American patients, the superiority of DOACs therapy is still controversial. Although, a previous meta-analysis included the post-hoc analyses and sub-analyses of DOACs, RCTs identified a non-inferiority of DOACs compared with warfarin in Latin American patients with AF (15). However, the RCTs included in this meta-analysis are outdated. New RCTs have been published in recent years and report more endpoint events and even find different results. Therefore, we aimed to reassess the effectiveness and safety outcomes of DOACs vs. warfarin in Latin American and non-Latin American patients with AF.

The two common databases of PubMed and Embase were systematically searched until November 2021 for the available studies using the following search terms: (1) atrial fibrillation (2) non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants OR direct oral anticoagulants OR dabigatran OR rivaroxaban OR apixaban OR edoxaban, and (3) vitamin K antagonists OR warfarin. The detailed search strategies are shown in Supplementary Table 1. In this meta-analysis, we included publications in English.

We included the post-hoc analyses of RCTs focusing on the effectiveness and/or safety of DOACs (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, or edoxaban) compared with warfarin in Latin American patients with non-valvular AF. The effectiveness outcomes included stroke or systemic embolism (SSE), stroke, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, ischemic stroke, all-cause death, cardiovascular death, and myocardial infarction; whereas the safety outcomes included major bleeding, major or non-major clinically relevant (NMCR) bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), gastrointestinal bleeding, and any bleeding. The follow-up time was not restricted. We excluded certain publication types such as reviews, case reports, case series, editorials, letters, and meeting abstracts because they had no sufficient data. Studies with overlapping data were also excluded.

Two authors (FW-L and YH-W) independently did the data extraction. We first screened the titles and abstracts of the searched records to select potential studies, and the full text of which was screened in the subsequent phase. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with the third researcher (WG-Z). Two authors independently collected the following characteristics: the first author and publication year, location, data source, study design, inclusion period, patient age and sex, type or dose of DOACs, follow-up time, effectiveness and safety outcomes, the sample size, and the number of events in the vitamin K antagonist (VKA) or DOAC groups, and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs.

We used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) to perform the quality assessment for the included studies. The NOS tool had three domains, scored a total of 9 points including the selection of cohorts (4 points), the comparability of cohorts (2 points), and the assessment of the outcome (3 points). In this study, we defined studies with the NOS of < 6 points as low quality (16).

We assessed the consistency across the included studies using the Cochrane Q test and the I2 statistic. A P < 0.1 for the Q statistic or I2 ≥50% indicated substantial heterogeneity. We first collected the sample size and the number of events in the warfarin or DOAC groups and calculated their corresponding crude rates of effectiveness and safety outcomes. The comparison results between the warfarin or DOAC groups were expressed as HRs and 95%CIs. Second, we assessed the effectiveness and safety of DOACs vs. warfarin in patients with AF using the adjusted HRs. The adjusted HRs and 95%CIs were converted to the natural logarithms (Ln[HR]) and standard errors, which were pooled by a random-effects model using an inverse variance method.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the Review Manager Version 5.4 (the Nordic Cochrane Center, Rigshospitalet, Denmark). The statistical significance threshold was set at a P < 0.05.

The process of the literature retrieval is presented in Supplementary Figure 1. A total of 170 studies were identified through the electronic searches in the PubMed and Embase databases. According to the predefined criteria, we finally included 4 studies in this meta-analysis (14, 17–19). Table 1 shows the baseline patient characteristics of the included studies. All include studies are hoc RCT and the data sources are from effective anticoagulation with factor Xa next generation atrial fibrillation–thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 48 (ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48) (14), apixaban for reduction in stroke and other thromboembolic events in atrial fibrillation trial (ARISTOTLE TRIAL) (17), rivaroxaban once daily oral direct factor Xa inhibition compared with vitamin K antagonism for prevention of stroke and embolism trial in atrial fibrillation (ROCKET AF trial) (18), and randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy (RE-LY) (19). Latin American includes Argentina Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela, and all the remaining countries included in the entire trial were considered to be non-LA countries. In total, 8,965 Latin American patients (5,096 taking DOACs and 3,869 taking warfarin) and 62,716 non-Latin American patients (37,315 taking DOACs and 25,401 taking warfarin) were included in this meta-analysis. All of these included studies had a moderate-to-high quality with the NOS score of ≥6 points.

In Latin American patients with AF, for the effectiveness outcomes shown in Supplementary Figure 2, the use of DOACs compared with warfarin was significantly associated with decreased risks of SSE [odds ratio (OR) = 0.79; 95% CI.64–0.99] and hemorrhagic stroke (OR = 0.13; 95% CI.05–0.33), but not stroke (OR = 0.76; 95% CI.54–1.07), ischemic stroke (OR = 1.19; 95% CI.80–1.78), all-cause death (OR = 0.91; 95%CI.78–1.07), and cardiovascular death (OR = 1.00; 95%CI.61–1.67). For the safety outcomes in Supplementary Figure 3, compared with warfarin, the use of DOACs was associated with reduced risks of major or NMCR bleeding (OR = 0.72; 95%CI.56–0.94), major bleeding (OR = 0.72; 95% CI.53–0.98), ICH (OR = 0.43; 95% CI.21–0.88), and any bleeding (OR = 0.66; 95% CI.57–0.78), but not gastrointestinal bleeding (OR = 0.65; 95% CI.10–3.99).

For patients treated with anticoagulants in non-Latin American patients with AF, for the effectiveness outcomes in Supplementary Figure 4, the use of DOACs compared with warfarin use was significantly associated with decreased risks of SSE (OR = 0.87; 95% CI.76–1.00), hemorrhagic stroke (OR = 0.41; 95% CI.25–0.67), all-cause death (OR = 0.89; 95% CI.84–0.95), cardiovascular death (OR = 0.87; 95% CI.79–0.95), but not stroke (OR = 0.92; 95%CI.69–1.22), ischemic stroke (OR = 1.08; 95% CI.82–1.42). For the safety outcomes in Supplementary Figure 5, compared with warfarin use, the use of DOACs was associated with reduced risks of major bleeding (OR = 0.77; 95% CI.62–0.95), ICH (OR = 0.43; 95%CI.35–0.53), and any bleeding (OR = 0.62; 95% CI.43–0.88), but not major or NMCR bleeding (OR = 0.80; 95%CI.61–1.04) and gastrointestinal bleeding (OR = 0.90; 95%CI.78–1.04).

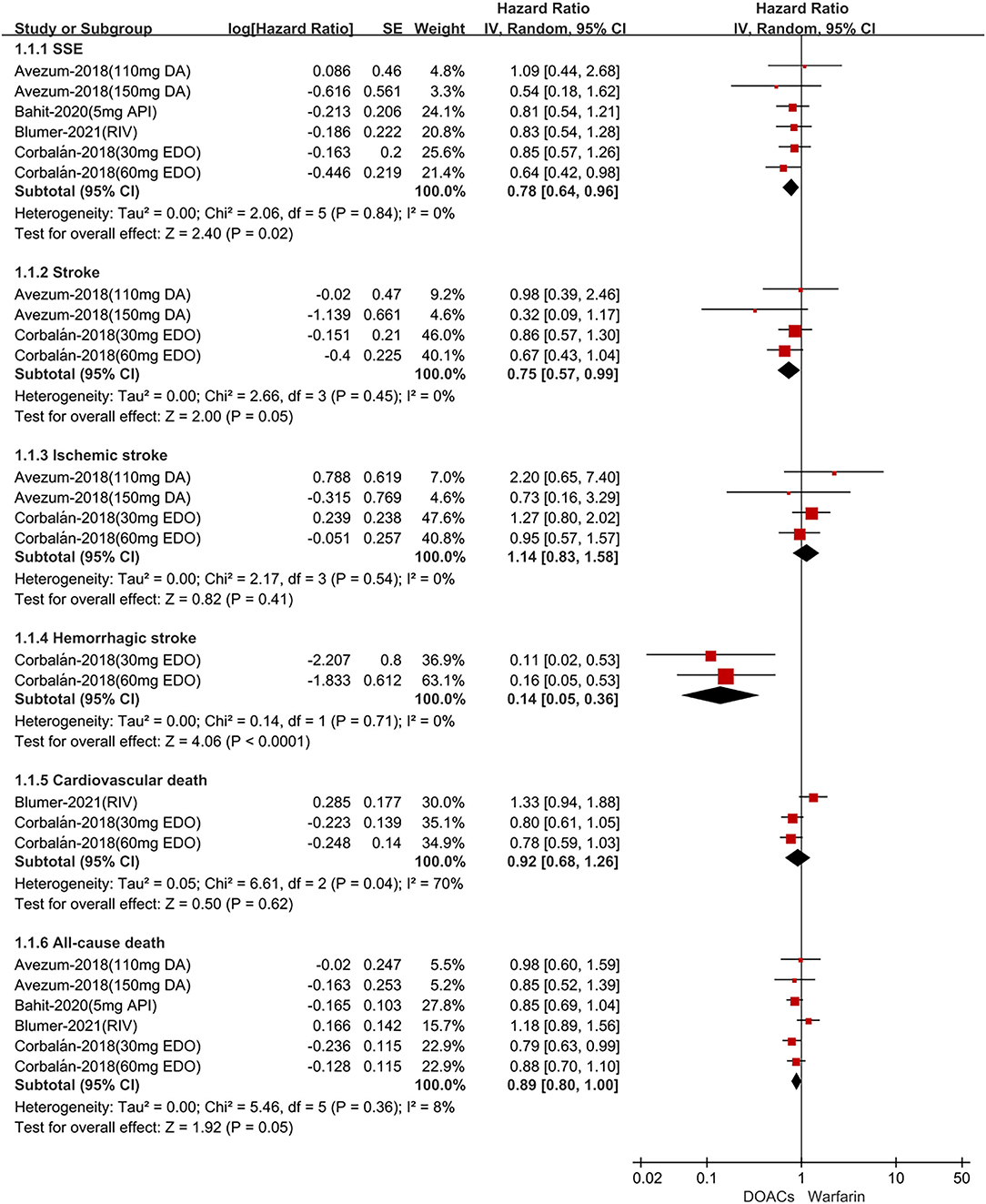

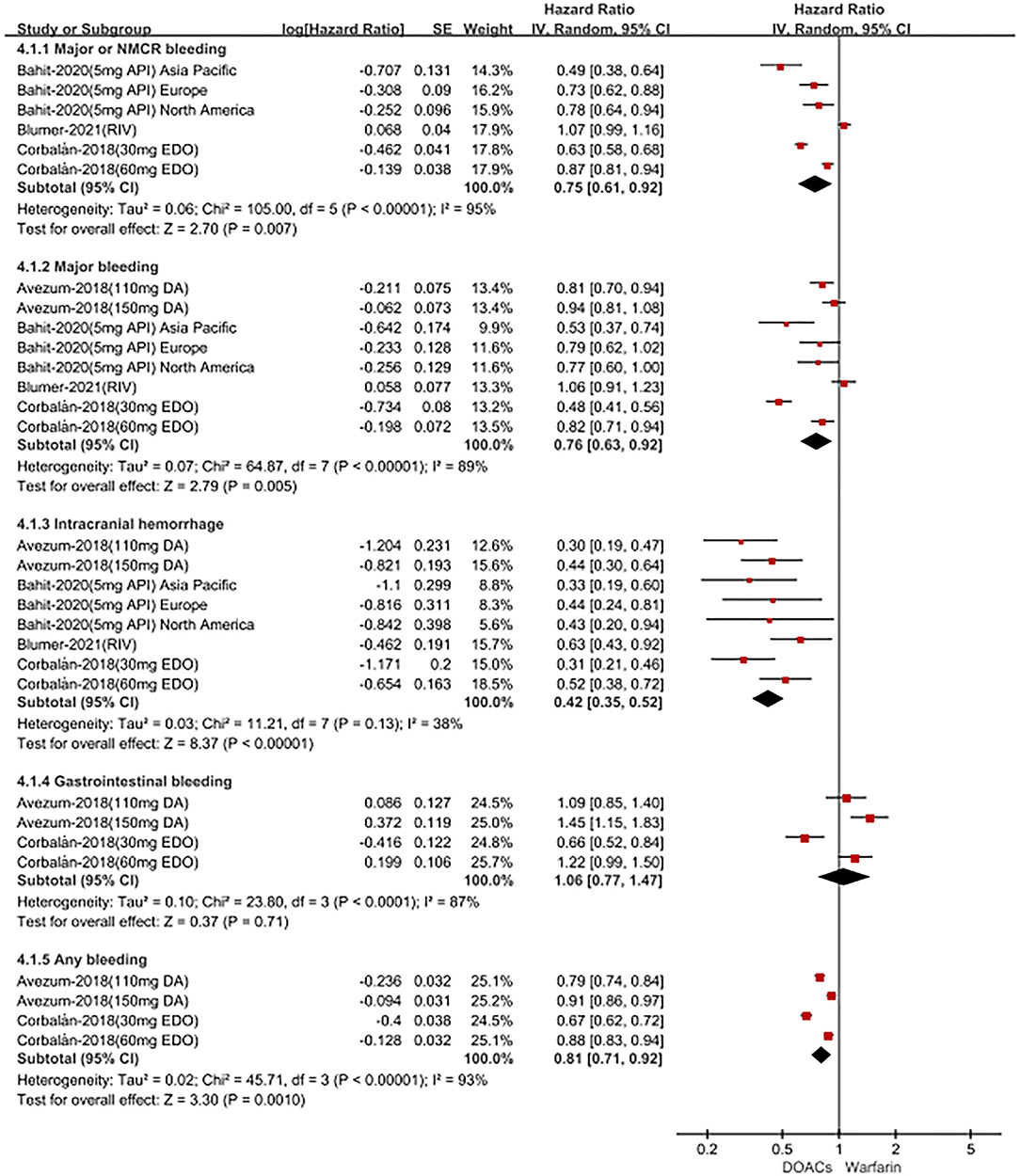

In Latin American patients with AF, for the effectiveness outcomes shown in Figure 1, the use of DOACs compared with warfarin was significantly associated with decreased risks of SSE (HR = 0.78; 95% CI.64–0.96), stroke (HR = 0.75; 95%CI.57–0.99), hemorrhagic stroke (HR = 0.14;95%CI.05–0.36), all-cause death (HR = 0.89; 95%CI.80–1.00), but not ischemic stroke (HR = 1.14; 95%CI.83–1.58) and cardiovascular death (HR = 0.92; 95%CI.68–1.26). For the safety outcomes in Figure 2, compared with warfarin, the use of DOACs was associated with reduced risks of major or NMCR bleeding (HR = 0.70; 95%CI.57–0.86), major bleeding (HR = 0.70; 95%CI.53–0.92), ICH (HR = 0.42; 95% CI.24–0.74), and any bleeding (HR = 0.70; 95%CI.62–0.78), but not gastrointestinal bleeding (HR = 1.08; 95% CI.65–1.78).

Figure 1. Adjusted effectiveness date of direct oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin in Latin patients with atrial fibrillation. DOACs, direct oral anticoagulants; DA, dabigatran; API, apixaban; EDO, edoxaban; RIV, rivaroxaban; SSE, stroke or systemic embolism; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2. Adjusted safety date of direct oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin in Latin patients with atrial fibrillation. DOACs, direct oral anticoagulants; DA, dabigatran; API, apixaban; EDO, edoxaban; RIV, rivaroxaban; CI, confidence interval.

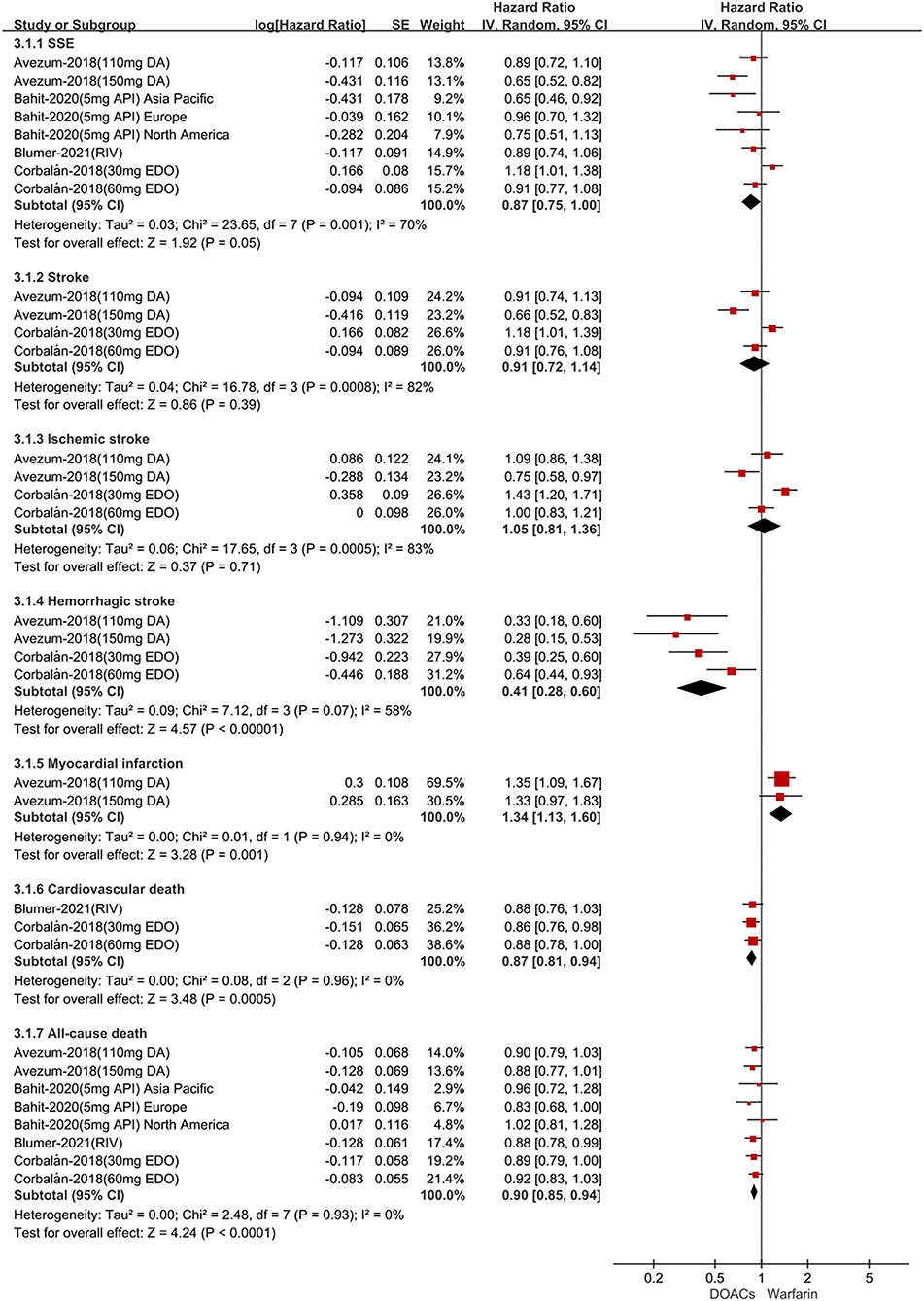

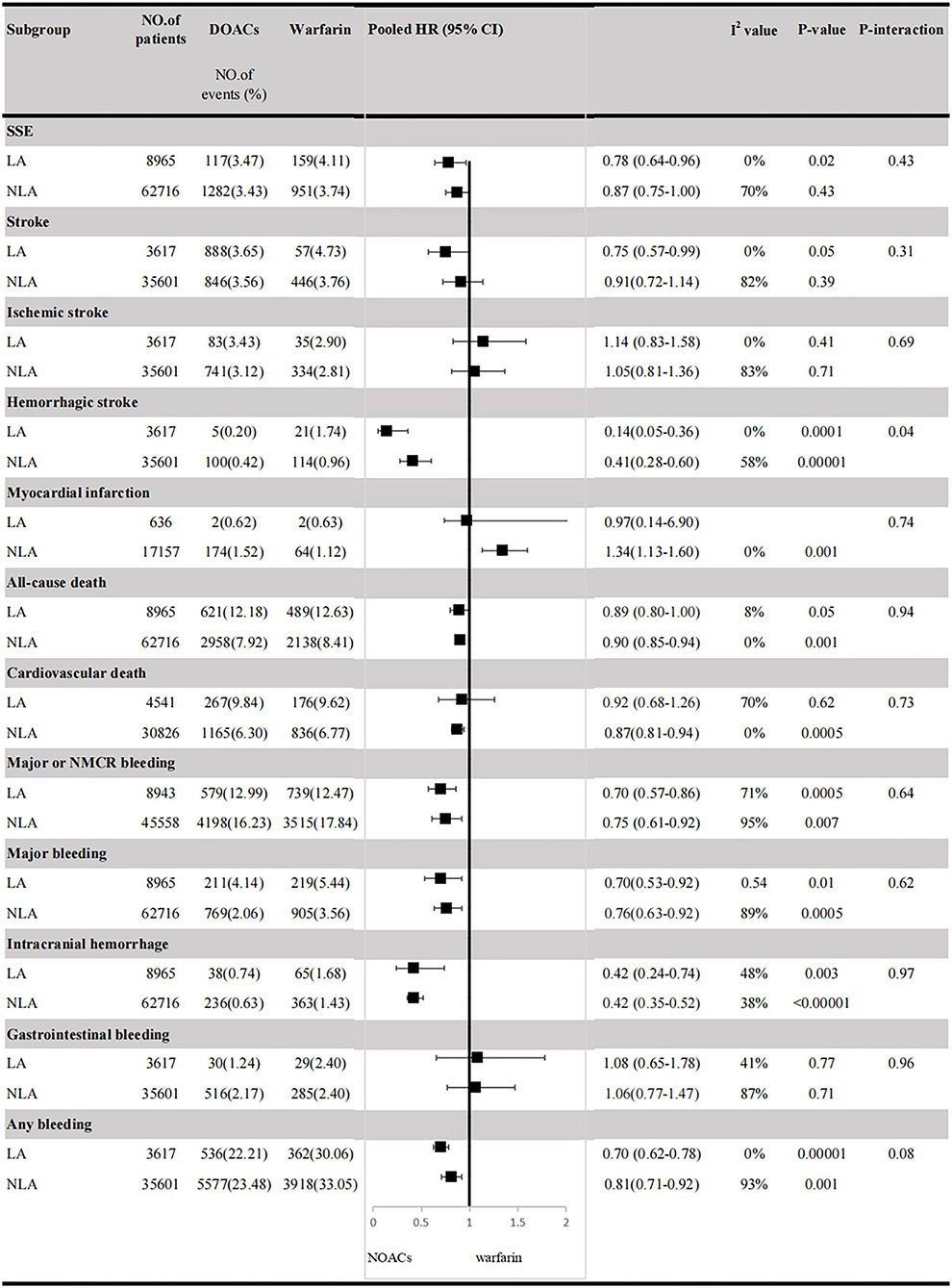

For patients treated with anticoagulants in non-Latin American patients with AF, for the effectiveness outcomes in Figure 3, the use of DOACs compared with warfarin was significantly associated with decreased risks of SSE (HR = 0.87; 95%CI.75–1.00), hemorrhagic stroke (HR = 0.41; 95%CI.28–0.60), cardiovascular death (HR = 0.87; 95% CI.81–0.94), all-cause death (HR = 0.90; 95%CI.85–0.94), conversely, increasing the risk of myocardial infarction (HR = 1.34; 95%CI 1.13–1.60), but not stroke (HR = 0.91; 95%CI.72–1.14) and ischemic stroke (HR = 1.05; 95% CI.81–1.36). For the safety outcomes in Figure 4, compared with warfarin use, the use of DOACs was associated with reduced risks of major or NMCR bleeding (HR = 0.75; 95% CI.61–0.92), major bleeding (HR = 0.76; 95%CI.63–0.92), ICH (HR = 0.42; 95% CI.36–0.52) and any bleeding (HR = 0.81; 95%CI.71–0.92), but not gastrointestinal bleeding (HR = 1.06; 95%CI.77–1.47). Not only that, we also conducted a summary analysis of the adjusted data of outcomes between Latin American patients and non-Latin American patients in Figure 5. The P-interaction between Latin American patients and non-Latin American patients with AF was no significant difference.

Figure 3. Adjusted effectiveness date of direct oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin in non-Latin patients with atrial fibrillation. DOACs, direct oral anticoagulants; DA, dabigatran; API, apixaban; EDO, edoxaban; RIV, rivaroxaban; SSE, stroke or systemic embolism; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 4. Adjusted safety date of direct oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin in non-Latin patients with atrial fibrillation. DOACs, direct oral anticoagulants; DA, dabigatran; API, apixaban; EDO, edoxaban; RIV, rivaroxaban; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 5. Efficacy and safety outcomes in AF patients from Latin American and non-Latin American. SSE, stroke or systemic embolism; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LA, Latin American; NLA, non-Latin American; CI, confidence interval; major or NMCR bleeding, major or non-major clinically relevant bleeding.

We have not performed an analysis of publication bias due to only 4 studies were included in our meta-analysis. It was noted that the publication bias should not be evaluated for some reported outcomes when fewer than 10 studies were included.

The main findings of our study were as follows: (1) DOAC use resulted in lower rates of SSE, stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, all-cause death, and associated with safer profiles (lower major or NMCR bleeding, major bleeding, ICH, and any bleeding) than warfarin in Latin American patients with AF; (2) DOAC use resulted in lower rates of SSE, hemorrhagic stroke, all-cause death, cardiovascular death, and associated with safer profiles (lower major or NMCR bleeding, major bleeding, ICH, and any bleeding) than warfarin in non-Latin American patients with AF; (3) DOAC use increased the risk of myocardial infarction than warfarin in non-Latin American patients with AF, but not in Latin American patients with AF; (4) in comparison to VKAs, DOACs were non-inferior regarding the outcomes of ischemic stroke, cardiovascular death, and gastrointestinal bleeding in Latin American patients with AF and the outcomes of stroke, ischemic stroke, and gastrointestinal bleeding in non- Latin American patients.

Important differences in clinical characteristics, response to treatment, and outcomes of patients with AF exist in the diverse regions of the world. Previous studies have shown that Latin American patients with AF are suffering from higher risks of death and embolism than non-Latin American patients with AF (20, 21). Actually, there are many reasons for the increased risk of death and embolism in Latin American patients with AF. Life expectancy differed substantially across cities within the same country. Cause-specific mortality also varied across cities, with some causes of death (unintentional and violent injuries and deaths) showing large variation within countries, whereas other causes of death (communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and other non-communicable diseases) varied substantially between countries. These results highlight considerable heterogeneity in life expectancy and causes of death across cities of Latin America (22). Moreover, heterogeneity of risk factors (23–25) and socioeconomic conditions, public awareness, and availability of healthcare services that influence outcomes of diseases differ substantially between countries (26, 27) in Latin America and still need to be taken into account. Furthermore, inadequate prescription for medications associated with death reduction might also affect the prognosis of Latin American patients with AF (14). Therefore, antithrombotic therapy is particularly important to reduce the risk of embolism in Latin American patients with AF. Previous meta-analyses including the post-hoc analyses and sub-analyses of DOAC RCTs showed that there is a non-inferiority of DOACs compared with warfarin in Latin American patients with AF (15). Compared to the previous study, the RCTs included in this meta-analysis are outdated. More importantly, the number of available clinical studies are small and the results are controversial. In recent years, several new post-hoc analyses of RCTs not only examined the association between region and efficacy and safety outcomes but also explored the use of individual DOACs compared with warfarin in Latin American patients. The RCTs provide more endpoint events and arrive at different conclusions. Therefore, we aimed to reassess the effectiveness and safety outcomes of DOACs vs. warfarin in Latin American and non-Latin American patients with AF. Our meta-analysis shows that DOACs appeared to have significant reductions in SSE, stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, all-cause death, major or NMCR bleeding, major bleeding, ICH, and any bleeding, but showed comparable rates of ischemic stroke, cardiovascular death, and gastrointestinal bleeding in Latin American patients with AF. DOACs appeared to have significant reductions in SSE, hemorrhagic stroke, all-cause death, cardiovascular death, major or NMCR bleeding, major bleeding, ICH, and any bleeding and increased the risk of myocardial infarction, but comparable risks of stroke, ischemic stroke, and gastrointestinal bleeding in non-Latin American patients with AF. In addition, we assessed crude event rates of outcomes between DOACs vs. warfarin in Latin/non-Latin American patients with AF. Overall, in comparison to warfarin, DOACs had lower or similar rates of thromboembolic and bleeding risk, which was consistent with a previous study (15). Interestingly, we found that DOACs increased the risk of myocardial infarction compared with warfarin in non-Latin American patients with AF. The result was derived from the RE-LY study, which included patients using dabigatran. Previous studies have warned this risk (28, 29). Prospective data on dabigatran in this population undergoing PCI are still needed.

It is worth pointing out that DOACs have advantages over warfarin such as short onset time, short half-life, low inter- and intra-individual variability, and drug-drug interactions. The current international guidelines recommend the use of DOACs as replacement therapy for VKAs in patients with non-valvular AF because it has more effective, safer, and more convenient features. Different from DOACs, the anticoagulant activity of VKAs depends on TTR (time in therapeutic range). Among the included studies, the mean TTR of VKAs users in Latin America ranged from 58 to 66%, which was not higher than that of non-Latin Americans overall and lower than what is recommended in the guidelines (1, 30). Therefore, DOACs may be regarded as a safer alternative to VKAs in Latin American patients with AF. Although no observational studies have been carried out to directly compare the use of DOACs and warfarin in Latin American patients with AF, several studies have validated the benefits of the use of DOACs in this population. Data from the GLORIA-AF (Global Registry on Long-Term Antithrombotic Treatment in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation, Phase II) study indicated the consistent safety and effectiveness of dabigatran in Latin American patients with AF during a 2-years follow-up (31). Moreover, the XANTUS-EL (Xarelto for Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation in Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Africa [EEMEA], and Latin America) study confirmed the benefits of rivaroxaban for stroke prevention in patients with non-valvular AF from Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America (32). However, the results concerning whether DOACs are more cost-effective than warfarin in Latin America remain a controversy (33). The evidence provided by our meta-analysis may offer some confidence to clinicians when selecting DOACs for Latin American patients who need anticoagulation therapy, especially for those at a high risk of bleeding. The present results support that the use of DOACs is at least non-inferior to warfarin in Latin American patients with AF and provides an effective anticoagulant choice without monitoring. Further studies should be performed to clarify this problem.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, because of the small number of included studies, we did not perform subgroup analysis based on dosage or type of DOACs. Second, individual patient-level data from trials were not available, and some of the patients in Latin American countries enrolled might not be ethnically Latin American. Third, the results of the present analysis do not represent all countries in Latin America, as a limited number of countries in this region were included. Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that there is potential confounding or interaction between enrollment in Latin America and anticoagulants.

The current pooled data from the four post-hoc analyses of RCTs suggested that compared with warfarin, DOACs appeared to have significant reductions in SSE, stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, all-cause death, major or NMCR bleeding, major bleeding, ICH, and any bleeding, but comparable risks of ischemic stroke, cardiovascular death, and gastrointestinal bleeding in Latin American patients with AF. DOACs appeared to have significant reductions in SSE, hemorrhagic stroke, all-cause death, cardiovascular death, major or NMCR bleeding, major bleeding, ICH, and any bleeding, and increased the risk of myocardial infarction, but comparable risks of stroke, ischemic stroke, and gastrointestinal bleeding in non-Latin American patients with AF.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2022.841341/full#supplementary-material

1. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the european association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis management of atrial fibrillation of the european society of cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the european heart rhythm association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. (2021) 42:373–498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612

2. Lippi G, Sanchis-Gomar F, Cervellin G. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: an increasing epidemic and public health challenge. Int J Stroke. (2021) 16:217–21. doi: 10.1177/1747493019897870

3. Chu G, Versteeg HH, Verschoor AJ, Trines SA, Hemels M, Ay C, et al. Atrial fibrillation and cancer - an unexplored field in cardiovascular oncology. Blood Rev. (2019) 35:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2019.03.005

4. Shah S, Norby FL, Datta YH, Lutsey PL, MacLehose RF, Chen LY, et al. Comparative effectiveness of direct oral anticoagulants and warfarin in patients with cancer and atrial fibrillation. Blood Adv. (2018) 2:200–9. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017010694

5. Kim K, Lee Y, Kim T, Uhm J, Pak H, Lee M, et al. Effect of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation patients with newly diagnosed cancer. Korean Circ J. (2018) 48:406. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2017.0328

6. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. (2011) 365:981–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107039

7. January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JJ, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society. Heart Rhythm. (2019) 16:e66–93. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.01.024

8. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. (2016) 37:2893–962. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210

9. Coons JC, Albert L, Bejjani A, Iasella CJ. Effectiveness and safety of direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in obese patients with acute venous thromboembolism. Pharmacotherapy. (2020) 40:204–10. doi: 10.1002/phar.2369

10. Cheung C, Parikh J, Farrell A, Lefebvre M, Summa-Sorgini C, Battistella M. Direct oral anticoagulant use in chronic kidney disease and dialysis patients with venous thromboembolism: a systematic review of thrombosis and bleeding outcomes. Ann Pharmacother. (2021) 55:711–22. doi: 10.1177/1060028020967635

11. Jerjes-Sanchez C, Corbalan R, Barretto A, Luciardi HL, Allu J, Illingworth L, et al. Stroke prevention in patients from Latin American countries with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: Insights from the GARFIELD-AF registry. Clin Cardiol. (2019) 42:553–60. doi: 10.1002/clc.23176

12. Koziel M, Teutsch C, Bayer V, Lu S, Gurusamy VK, Halperin JL, et al. Changes in anticoagulant prescription patterns over time for patients with atrial fibrillation around the world. J Arrhythm. (2021) 37:990–1006. doi: 10.1002/joa3.12588

13. Cantu-Brito C, Silva GS, Ameriso SF. Use of guidelines for reducing stroke risk in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a review from a latin american perspective. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. (2018) 24:22–32. doi: 10.1177/1076029617734309

14. Corbalan R, Nicolau JC, Lopez-Sendon J, Garcia-Castillo A, Botero R, Sotomora G, et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in latin american patients with atrial fibrillation: the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2018) 72:1466–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.037

15. Su Z, Zhang H, He W, Ma J, Zeng J, Jiang X. Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants with warfarin in Latin American patients with atrial fibrillation. Medicine. (2020) 99:e19542. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019542

16. Xue Z, Zhang H. Non-Vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in Asians with atrial fibrillation: meta-analysis of randomized trials and real-world studies. Stroke. (2019) 50:2819–28. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.026054

17. Bahit MC, Granger CB, Alexander JH, Mulder H, Wojdyla DM, Hanna M, et al. Regional variation in clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: findings from the ARISTOTLE trial. Int J Cardiol. (2020) 302:53–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.12.060

18. Blumer V, Rivera M, Corbalan R, Becker RC, Berkowitz SD, Breithardt G, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation enrolled in Latin America: Insights from ROCKET AF. Am Heart J. (2021) 236:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2021.02.004

19. Avezum A, Oliveira G, Diaz R, Hermosillo J, Oldgren J, Ripoll EF, et al. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran versus warfarin from the RE-LY trial. Open Heart. (2018) 5:e800. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2018-000800

20. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. (2011) 365:883–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638

21. Massaro AR, Lip G. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: focus on Latin America. Arq Bras Cardiol. (2016) 107:576–89. doi: 10.5935/abc.20160116

22. Bilal U, Hessel P, Perez-Ferrer C, Michael YL, Alfaro T, Tenorio-Mucha J, et al. Life expectancy and mortality in 363 cities of Latin America. Nat Med. (2021) 27:463–70. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01214-4

23. Rivera-Andrade A, Luna MA. Trends and heterogeneity of cardiovascular disease and risk factors across Latin American and Caribbean countries. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. (2014) 57:276–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2014.09.004

24. Miranda JJ, Herrera VM, Chirinos JA, Gomez LF, Perel P, Pichardo R, et al. Major cardiovascular risk factors in Latin America: a comparison with the United States. The Latin American consortium of studies in obesity (LASO). PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e54056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054056

25. Champagne BM, Sebrie EM, Schargrodsky H, Pramparo P, Boissonnet C, Wilson E. Tobacco smoking in seven Latin American cities: the CARMELA study. Tob Control. (2010) 19:457–62. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031666

26. Ouriques MS, Sacks C, Hacke W, Brainin M, de Assis FF, Marques PO, et al. Priorities to reduce the burden of stroke in Latin American countries. Lancet Neurol. (2019) 18:674–83. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30068-7

27. Avezum A, Costa-Filho FF, Pieri A, Martins SO, Marin-Neto JA. Stroke in Latin America: burden of disease and opportunities for prevention. Glob Heart. (2015) 10:323–31. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.01.006

28. Uchino K, Hernandez AV. Dabigatran association with higher risk of acute coronary events: meta-analysis of noninferiority randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. (2012) 172:397–402. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1666

29. Gaubert M, Resseguier N, Laine M, Bonello L, Camoin-Jau L, Paganelli F. Dabigatran versus vitamin k antagonist: an observational across-cohort comparison in acute coronary syndrome patients with atrial fibrillation. J Thromb Haemost. (2018) 16:465–73. doi: 10.1111/jth.13931

30. Lip GYH, Banerjee A, Boriani G, Chiang CE, Fargo R, Freedman B, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. (2018) 154:1121–201. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.07.040

31. Dubner S, Saraiva JFK, Fragoso JCN, Barón-Esquivias G, Teutsch C, Gurusamy VK, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dabigatran in Latin American patients with atrial fibrillation: two years follow up results from GLORIA-AF registry. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. (2020) 31:100666. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100666

32. Martínez CAA, Lanas F, Radaideh G, Kharabsheh SM, Lambelet M, Viaud MAL, et al. XANTUS-EL: a real-world, prospective, observational study of patients treated with rivaroxaban for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation in Eastern Europe, Middle East, Africa and Latin America. Egypt Heart J. (2018) 70:307–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2018.09.002

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, direct oral anticoagulants, warfarin, Latin American, meta-analysis

Citation: Liu F, Wang Y, Luo J, Huang L, Zhu W, Yin K and Xue Z (2022) Direct Oral Anticoagulants vs. Warfarin in Latin American Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Evidence From Four post-hoc Analyses of Randomized Clinical Trials. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9:841341. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.841341

Received: 22 December 2021; Accepted: 08 February 2022;

Published: 04 March 2022.

Edited by:

Antonino Tuttolomondo, University of Palermo, ItalyReviewed by:

Paolo Calabrò, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Liu, Wang, Luo, Huang, Zhu, Yin and Xue. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fuwei Liu, Z3psaXVmdXdlaUAxNjMuY29t; Zhengbiao Xue, NTc0Mzg0NDBAcXEuY29t; Kang Yin, NDc0NjE0OTA5QHFxLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

‡These authors share senior authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.