94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CASE REPORT article

Front. Cardiovasc. Med., 31 October 2022

Sec. Heart Failure and Transplantation

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.1045353

This article is part of the Research TopicCase Reports in Heart Failure and Transplantation: 2022View all 18 articles

Parts of this article's content have been modified or rectified in:

Erratum: Disseminated Scedosporium apiospermum infection with invasive right atrial mass in a heart transplant patient

Baudouin Bourlond1*

Baudouin Bourlond1* Ana Cipriano2

Ana Cipriano2 Julien Regamey1

Julien Regamey1 Matthaios Papadimitriou-Olivgeris2

Matthaios Papadimitriou-Olivgeris2 Christel Kamani1,3

Christel Kamani1,3 Danila Seidel4,5,6,7

Danila Seidel4,5,6,7 Frederic Lamoth2,8

Frederic Lamoth2,8 Olivier Muller1

Olivier Muller1 Patrick Yerly1

Patrick Yerly1Scedosporium apiospermum associated endocarditis is extremely rare. We report a case of a disseminated S. apiospermum infection with an invasive right atrial mass in a 52-year-old male, 11 months after heart transplantation, referred to our institution for an endogenous endophthalmitis with a one-month history of diffuse myalgias and fatigue. The patient had been supported two times with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) during the first three postoperative months. The echocardiography on admission revealed a mass in the right atrium attached to a thickened lateral wall. The whole-body [18F]FDG PET/CT revealed systemic dissemination in the lungs, muscles, and subcutaneous tissue. Blood cultures were positive on day three for filamentous fungi later identified as S. apiospermum. The disease was refractory to a 3-week dual antifungal therapy with voriconazole and anidulafungin in addition to reduced immunosuppression, and palliative care was implemented.

Fungal infective endocarditis (FE) remains the most serious form of infective endocarditis, associated to a high mortality rate (∼50%) (1). In about half of the cases, Candida species account for FE, Aspergillus spp., account for one fourth of the cases (2). Non-Aspergillus molds infective endocarditis account for the remaining of cases, with Scedosporium spp. being seldom identified.

Scedosporium spp. are filamentous fungi, ubiquitous in the environment and commonly found in temperate climates. Scedosporium apiospermum and Lomentospora prolificans (formerly S. prolificans) (S/L) are the major pathogens in humans (3). Infection occurs after inhalation of spores into the lungs or paranasal sinuses or through direct skin inoculation after traumatic injuries or during surgery. Medical care advances increased the number of immunocompromised patients with non-Aspergillus mold infections (NAIMI). In solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients, approximately 25% of NAIMI are caused by S/L, representing 1% of all fungal infections in these patients (4, 5). In this population, pretransplant colonization of the respiratory tract (lung transplant recipients), prior amphotericin B treatment, and enhanced immunosuppression, as a treatment for organ rejection, represent the major associated risk factors for NAIMI (6).

Scedosporiosis and lomentosporiosis are of particular concern due to intrinsic resistance to most available antifungal drugs. Outcomes seem to be better with S. apiospermum infection, which presents a better response to antifungal agents. Voriconazole appears to have the best in vitro activity and is considered the drug of choice by most international guidelines (7). Combined antifungal therapy with echinocandins may be used against S. apiospermum, as a synergistic effect has been described (6, 8, 9). Where possible, surgical debridement and immunosuppression reduction should be part of the treatment management (6, 9).

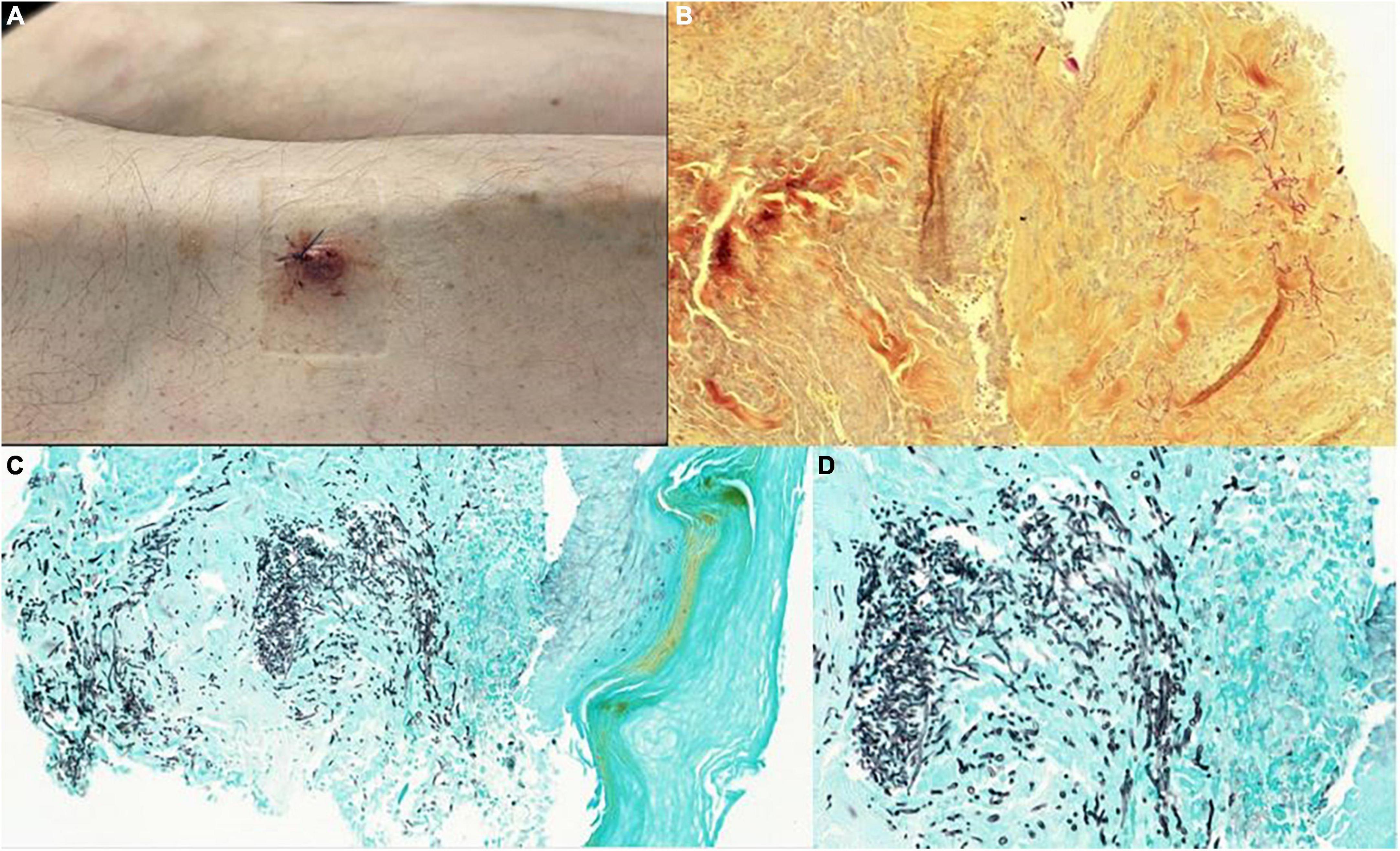

A 52-year-old male patient was referred to our hospital by the ophthalmologist for additional work-up in the context of endogenous endophthalmitis. He reported a one-month history of migratory myalgia without fever, one-week history of abdominal pain with vomiting, atraumatic eyes pain for two days, and an isolated cutaneous nodule on the right inferior limb (Figure 1, Panel A). He had received a heart transplantation for dilated cardiomyopathy 11 months prior to admission and had been on a left ventricular assist device (Heartmate 3TM) for three years before transplantation. His transplant operation had been complicated with primary graft failure necessitating eight days of mechanical support with veno-arterial ECMO. Moreover, he had suffered from a nosocomial SARS-CoV2 infection on the third post-operative month, with acute respiratory distress syndrome treated with tocilizumab, and refractory hypoxemia necessitating 18 days of venovenous ECMO. In both cases, peripheral cannulation of the right atrium was used.

Figure 1. Painful purplish cutaneous nodules (A), pathology examination with Periodic Acid Schiff coloration 10x (B), and colorations with GROCOTT stain of cutaneous nodules showing regular septate filaments connected with 45-degree divisions 10x (C) and 40x (D).

At presentation (day 1), he was on immunosuppressive therapy with prednisolone 12.5 mg od, tacrolimus 3 mg bid, and mycophenolate mofetil 720 mg bid. On admission, blood pressure was 140/76 mmHg with a resting heart rate of 70 beats per minute and a temperature of 36.3°C. Physical examination was noteworthy for diffuse right eyelid edema, a painless purplish cutaneous nodule of the outer edge of the tibia (Figure 1, Panel A), and asymmetric erythema of the right ankle. Cardio-pulmonary, neurological and abdominal examinations were regular.

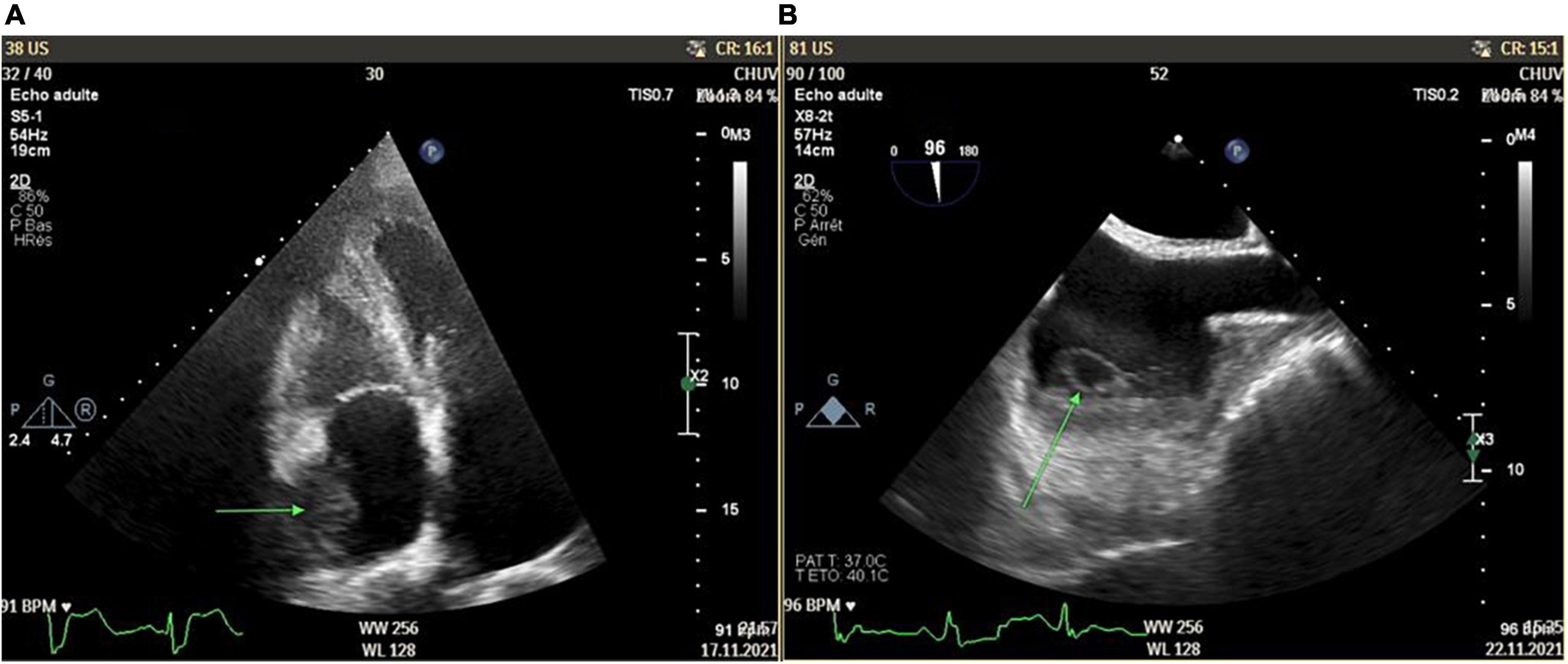

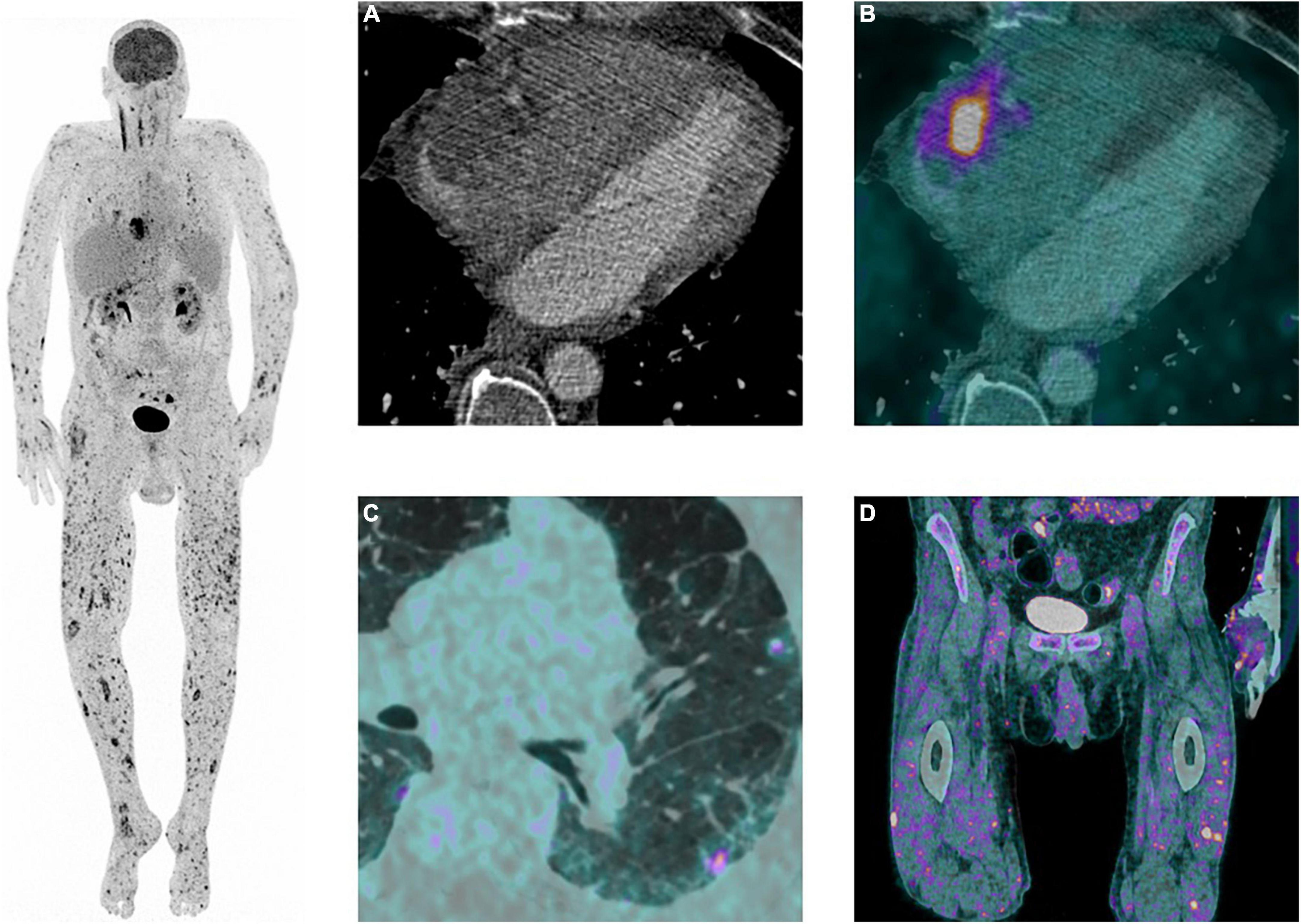

The cardiac workup included a transthoracic echocardiography revealing an atrial mass measuring 15 × 18 mm, with a thickened lateral wall without associated tricuspid valve anomalies (Figure 2A). These findings were confirmed with transoesophageal echocardiography, which showed an abscessed pattern in this mass and moving filaments (Figure 2B). The fundoscopy revealed bilateral endogenous endophthalmitis and Roth spots. Laboratory tests showed increased inflammatory parameters (CRP: 163 mg/L, procalcitonin: 0.66 mcg/L), with relatively low leucocyte count (4.8 G/L) and a KDIGO 1 acute kidney injury. Blood cultures were collected. In order to characterize the nature of the right atrial mass, a whole-body [18F]FDG PET/CT after 24 h of dietary preparation and heparin pre-administration to suppress the physiological myocardial FDG uptake was performed (10). It showed an intense FDG accumulation of the right atrial mass with extension to the epicardium, which was suggestive of an active infectious process. Septic emboli in the lungs, muscles, and subcutaneous tissue were also evident (Figure 3). Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also highlighted multiple brain lesions.

Figure 2. Right atrium mass (15 × 18 mm) with thickened lateral wall without associated tricuspid valve anomalies as shown in transthoracic echocardiography [green arrow, Panel (A)] and transesophageal echocardiography [green arrow, Panel (B)].

Figure 3. 18F-fluodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) Positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography angiography (CTA) findings. Left: Maximum intensity projection image of the whole body showing pathological focal diffuse [18F]FDG uptake of the trunk as well as the upper and lower extremities. Right: (A) Cardiac CTA showing an heterogeneous mass with irregular margins, in contact with the lateral wall of the right atrium with extension in the pericardial space. (B) Transaxial view of [18F]FDG PET/CTA showing pathological [18F]FDG accumulation of the right atrial mass, suggestive of an active infectious process. (C) Transaxial view of [18F]FDG PET/CTA showing focal subpleural nodules with increase [18F]FDG accumulation in the left lung, suggestive of septic emboli. (D) Coronal view of [18F]FDG PET/CT showing focal increased cutaneous and subcutaneous [18F]FDG accumulation in the proximal part of the lower limbs, suggestive of septic emboli.

The first suspected diagnosis was bacterial endocarditis with secondary endogenous endophthalmitis (Staphylococcus aureus, streptococci, or enterococci as the most likely pathogens). Therefore, intravenous empirical antibiotic therapy with vancomycin and co-amoxicillin was started while awaiting blood cultures and the culture of a vitreous sample. Twenty-four hours later, due to increased serum beta-D-glucan antigen (>500 pg/ml) and negative blood cultures a fungal infection was suspected and liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) was initiated. The immunosuppression was reduced to the minimum with prednisone 5 mg and tacrolimus for trough levels at 5–7 ug/L. Blood cultures were positive for filamentous fungi on day 3. S. apiospermum was identified as the causative pathogen three days later (day 6) and liposomal amphotericin B (minimum inhibitory concentration, – MIC 2.0 mg/l) switched to combination therapy with voriconazole (6 mg/kg bid the first day and then 4 mg/kg bid; MIC 0.25 mg/l) and anidulafungin (200 mg the first day and then 100 mg/day; MIC 1 mg/l). The endophthalmitis was treated with an intravitreal injection of ceftazidime and vancomycin. After S. apiospermum was identified, two intravitreal injections of voriconazole 0.5 mg were performed. Surgical resection of the right atrial mass was early discussed but refrained considering the invasion of the atrial wall, the disseminated disease, and the patient’s poor general condition with worsening asthenia and daily loss of weight despite enteral and then parenteral nutrition.

Despite dual antifungal therapy and reduced immunosuppression, the patient presented with ongoing fever, declining general condition, and a confusional state favored by brain abscesses and severely impaired vision. During this time, cardiac function remained stable, and no local complications of the atrial mass such as atrial obstruction, wall rupture with pericardial effusion, or invasion of the tricuspid valve were observed during serial echocardiographic assessments. Nevertheless, he developed multiple painful purplish cutaneous nodules, two of whom were biopsied and revealed regular septate filaments connected with 45-degree divisions on the Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) and GROCOTT coloration (Figure 1). These lesions were extremely painful, and pain management was a true challenge in the context of severe renal impairment and worsening liver function related to the toxicity of antifungal therapies. A high dose of intravenous fentanyl was necessary in addition to anxiolytic treatment.

After three weeks of optimal medical treatment, cerebral MRI and [18F]FDG PET/CT were performed and showed no regression of the multiple lesions. The clinical course continued to be unfavorable, with the patient’s general condition declining rapidly. At his request, palliative care was started. He was transferred to a palliative institution, where he deceased a few days later.

Scedosporiosis/lomentosporiosis, even though rare, is of particular concern due to intrinsic resistance to available antifungal drugs. Current clinical guidelines recommend voriconazole alone or in combination and surgical source control (7, 8).

By microscopy, the morphological characteristics of these fungi are well characterized and distinct with the presence of ovoid or pyriform conidia arising as a single terminal spore from a long tiny conidiophore (S. apiospermum complex) or in clusters from a short flask shaped conidiophore (L. prolificans).

Invasive scedosporiosis represents 13–33% of infections due to non-Aspergillus molds (11). Fifty-seven cases of scedosporiosis were described in the United States, while only 5 cases have been reported with heart involvement worldwide (12), as shown in Table 1. In these cases, despite antifungal treatments (itraconazole, voriconazole, amphotericin B), there was no survivor (6, 13).

Table 1. Literature review of infective endocarditis caused by Scedosporium spp. in solid transplant patients.

Our patient was on tacrolimus, which was previously shown to have synergistic effect with azoles in vitro and in a Galleria mellonella larvae model (14). However, this synergistic effect is obtained at high concentrations of tacrolimus (i.e., beyond the therapeutic range) and is counterbalanced by the strong immunosuppressive effect of this calcineurin inhibitor which may favor invasive fungal infections. As previously shown, despite this synergistic effect, the outcome was unfavorable for our patient.

It is noteworthy that novel antifungal agents, such as fosmanogepix (inhibitor of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis) and olorofim (inhibitor of the dihydroorotate dehydrogenase), which are currently in phase II-III clinical trials, demonstrated potent in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy in murine models against S. apiospermum and L. prolificans, and therefore represent promising therapies for scedosporiosis/lomentosporosis in the future (9, 15, 16). Our case illustrates a unique presentation of this rare infection with an intra-cardiac mass in the right atrium infiltrating its lateral wall and the tricuspid annulus, with disseminated disease (bilateral endophthalmitis, lungs, brain, muscles, and subcutaneous tissue). The patient was supported with ECMO twice following heart transplantation, which suggests that the infection may have spread from the venous cannula of the ECMO in the right atrium. Moreover, in addition to his post-transplant immunosuppression, he received tocilizumab to treat his severe SARS-COV-2 infection. This IL-2 receptor inhibitor has been associated with an increased risk for fungal infections (17). This kind of infection can happen in transplant patients, especially if they previously had primary graft dysfunction (PGD) or veno-arterial ECMO.

Our case highlights the importance of early detection of the pathogen by fungal culture or indirect marker such as the beta-glucan test in serum (13). In addition to surgery and reduction of immunosuppression when possible, early identification and treatment may improve the chance of recovery and survival.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

All authors approved the manuscript, vouch for the accuracy, and completeness of the data.

Open access funding was provided by the University of Lausanne.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Pierrotti LC, Baddour LM. Fungal endocarditis, 1995-2000. Chest. (2002) 122:302–10. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.1.302

2. Pasha AK, Lee JZ, Low SW, Desai H, Lee KS, Al Mohajer M. Fungal endocarditis: update on diagnosis and management. Am J Med. (2016) 129:1037–43. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.05.012

3. Cortez KJ, Roilides E, Quiroz-Telles F, Meletiadis J, Antachopoulos C, Knudsen T, et al. Infections caused by Scedosporium spp. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2008) 21:157–97. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00039-07

4. Park BJ, Pappas PG, Wannemuehler KA, Alexander BD, Anaissie EJ, Andes DR, et al. Invasive non-Aspergillus mold infections in transplant recipients, United States, 2001–2006. Emerg Infect Dis. (2011) 17:1855–64. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110087

5. Neofytos D, Fishman JA, Horn D, Anaissie E, Chang CH, Olyaei A, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. (2010) 12:220–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2010.00492.x

6. Husain S, Muñoz P, Forrest G, Alexander BD, Somani J, Brennan K, et al. Infections due to Scedosporium apiospermum and Scedosporium prolificans in transplant recipients: clinical characteristics and impact of antifungal agent therapy on outcome. Clin Infect Dis. (2005) 40:89–99. doi: 10.1086/426445

7. Cornely OA, Cuenca-Estrella M, Meis JF, Ullmann AJ. European society of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases (ESCMID) fungal infection study group (EFISG) and European confederation of medical mycology (ECMM) 2013 joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of rare and emerging fungal diseases. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2014) 20 Suppl 3:1–4. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12569

8. Shoham S, Dominguez EA AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Emerging fungal infections in solid organ transplant recipients: guidelines of the American society of transplantation infectious diseases community of practice. Clin Transplant. (2019) 33:e13525. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13525

9. McCarthy MW, Katragkou A, Iosifidis E, Roilides E, Walsh TJ. Recent advances in the treatment of scedosporiosis and fusariosis. J Fungi (Basel). (2018) 4:1–16. doi: 10.3390/jof4020073

10. Osborne MT, Hulten EA, Murthy VL, Skali H, Taqueti VR, Dorbala S, et al. Patient preparation for cardiac fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging of inflammation. J Nucl Cardiol. (2017) 24:86–99. doi: 10.1007/s12350-016-0502-7

11. Slavin M, van Hal S, Sorrell TC, Lee A, Marriott DJ, Daveson K, et al. Invasive infections due to filamentous fungi other than Aspergillus: epidemiology and determinants of mortality. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2015) 21:490.e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.12.021

12. Seidel D, Meißner A, Lackner M, Piepenbrock E, Salmanton-García J, Stecher M, et al. Prognostic factors in 264 adults with invasive Scedosporium spp. and Lomentospora prolificans infection reported in the literature and FungiScope®. Crit Rev Microbiol. (2019) 45:1–21. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2018.1514366

13. Bronnimann D, Garcia-Hermoso D, Dromer F, Lanternier F French Mycoses Study Group, Characterization of the isolates at the NRCMA. Scedosporiosis/lomentosporiosis observational study (SOS): clinical significance of Scedosporium species identification. Med Mycol. (2021) 59:486–97. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myaa086

14. Wang Z, Liu M, Liu L, Li L, Tan L, Sun Y. The synergistic effect of tacrolimus (FK506) or everolimus and azoles against. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2022) 12:864912. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.864912

15. Seyedmousavi S, Chang YC, Youn JH, Law D, Birch M, Rex JH, et al. In vivo efficacy of olorofim against systemic scedosporiosis and lomentosporiosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (2021) 65:e0043421. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00434-21

16. Lamoth F, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP. Investigational antifungal agents for invasive mycoses: a clinical perspective. Clin Infect Dis. (2022) 75:534–44. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab1070

17. Peng J, Fu M, Mei H, Zheng H, Liang G, She X, et al. Efficacy and secondary infection risk of tocilizumab, sarilumab and anakinra in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. (2022) 32:e2295. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2295

18. Morio F, Horeau-Langlard D, Gay-Andrieu F, Talarmin JP, Haloun A, Treilhaud M, et al. Disseminated Scedosporium/Pseudallescheria infection after double-lung transplantation in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. (2010) 48:1978–82. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01840-09

19. Hirschi S, Letscher-Bru V, Pottecher J, Lannes B, Jeung MY, Degot T, et al. Disseminated Trichosporon mycotoxinivorans, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Scedosporium apiospermum coinfection after lung and liver transplantation in a cystic fibrosis patient. J Clin Microbiol. (2012) 50:4168–70. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01928-12

20. Kim SH, Ha YE, Youn JC, Park JS, Sung H, Kim MN, et al. Fatal scedosporiosis in multiple solid organ allografts transmitted from a nearly-drowned donor. Am J Transplant. (2015) 15:833–40. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13008

21. Clement ME, Maziarz EK, Schroder JN, Patel CB, Perfect JR. Scedosporium apiosermum infection of the “Native” valve: fungal endocarditis in an orthotopic heart transplant recipient. Med Mycol Case Rep. (2015) 9:34–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2015.07.005

Keywords: Scedosporium apiospermum, Lomentospora prolificans, PET/CT, infective endocarditis, mycoses, heart tranplantation, heart failure

Citation: Bourlond B, Cipriano A, Regamey J, Papadimitriou-Olivgeris M, Kamani C, Seidel D, Lamoth F, Muller O and Yerly P (2022) Case report: Disseminated Scedosporium apiospermum infection with invasive right atrial mass in a heart transplant patient. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9:1045353. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.1045353

Received: 15 September 2022; Accepted: 05 October 2022;

Published: 31 October 2022.

Edited by:

Matteo Cameli, University of Siena, ItalyReviewed by:

Suguru Ohira, Westchester Medical Center, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Bourlond, Cipriano, Regamey, Papadimitriou-Olivgeris, Kamani, Seidel, Lamoth, Muller and Yerly. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Baudouin Bourlond, YmF1ZG91aW4tcGhpbGlwcGUuYm91cmxvbmRAY2h1di5jaA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.