- 1Physical Activity Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Unit, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 2Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation Program, Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada

- 3Department of Pedagogy of the Human Body Movement, School of Physical Education and Sport, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

- 4Applied Physiology and Nutrition Research Group, School of Physical Education and Sport, Rheumatology Division, Faculdade de Medicina FMUSP, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

- 5Institute of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Faculty of Medicine FMUSP, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

- 6Sport Department, School of Physical Education and Sport, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

- 7School of Exercise Science, Physical and Health Education, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada

- 8Association for Assistance of Disabled Children, São Paulo, Brazil

- 9Department of French, Hispanic and Italian Studies, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 10Aurora Physio & Care, Physiotherapy Center, Campinas, Brazil

Background: The Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone (PAR-Q+) is the international standard for pre-participation risk stratification and screening. In order to provide a practical and valid screening tool to facilitate safe engagement in physical activity and fitness assessments for the Brazilian population, this study aimed to translate, culturally adapt, and verify the reproducibility of the evidence-based PAR-Q+ to the Brazilian Portuguese language.

Method: Initially, the document was translated by two independent translators, before Brazilian experts in health and physical activity evaluated the translations and produced a common initial version. Next, two English native speakers, fluent in Brazilian Portuguese and accustomed to the local culture, back-translated the questionnaire. These back translations were assessed by the organization in charge of the PAR-Q+, then a final Brazilian version was approved. A total of 493 Brazilians between 5 and 93 yr (39.9 ± 25.4 yr), 59% female, with varying levels of health and physical activity, completed the questionnaire twice, in person or online, 1–2 weeks apart. Cronbach's alpha was used to calculate the internal consistency of all items of the questionnaire, and the Kappa statistic was used to assess the individual reproducibility of each item of the document. Additionally, the intraclass correlation coefficient and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to verify the general reproducibility (reliability) of the translated version.

Results: The Brazilian version had an excellent internal consistency (0.993), with an almost perfect agreement in 93.8% of the questions, and a substantial agreement in the other 6.2%. The translated version also had a good to excellent total reproducibility (0.901, 95% CI: 0.887–0.914).

Conclusion: The results show this translation is a valid and reliable screening tool, which may facilitate a larger number of Brazilians to start or increase physical activity participation in a safe manner.

Introduction

Physical inactivity is related to several health problems and is estimated to lead to the premature death of ~9% of the global population (1). Routine physical activity participation protects against more than 25 chronic medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, some types of cancer, depression, and osteoporosis, and significantly reduces the risk of early mortality (2, 3). Owing to these benefits, governments and health organizations around the world are investing in initiatives for the promotion of regular physical activity, including changes in the physical environment and public policies (4). However, there are other factors associated with physical inactivity, such as biological and psychological aspects (3, 5). In this respect, the fear of injury, getting sick, and even dying are reported, among others, as some of the most common barriers to physical activity (6–8). These concerns are shared by health professionals who prescribe supervised as well as unsupervised physical activity and exercise to prevent and manage chronic diseases (8–10).

To address this issue the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) was created in Canada in the 1970s, as a pre-participation screening tool, based on experts' opinion (11, 12). With seven health-related questions to be answered as Yes or No, the document was used extensively globally (13). However, various limitations to the survey were acknowledged (14–16). For instance, a major limitation of the PAR-Q was that its use was restricted to people between 15 and 69 years of age (17). Age restrictions on a front-line pre-participation screening tool is a contemporary issue for physical activity participation given population aging worldwide (18). Another significant limitation was the conservative nature of the PAR-Q, which led to many false positives (19). When an individual answered Yes to one or more questions, they were advised to consult a physician for clearance to participate in physical activity (20, 21). However, obtaining physical activity clearance from a physician may not be feasible in several jurisdictions (22). On a global scale, access to medical professionals can involve very long waiting lists for public services, and access to private options is limited and unaffordable for many (23, 24).

Given such limitations, a series of systematic reviews together with an evidence-based consensus process were performed to establish best practices in risk stratification for physical activity participation (25–34). From this process, a new, evidence-based pre-participation screening tool was created: The Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone (PAR-Q+) (20). In the current PAR-Q+, when the respondent answers No to all seven evidence-informed initial questions, they are self-cleared for unrestricted physical activity participation (35). If the individual answers Yes to one or more of these general health questions, they are required to complete follow-up questions on specific chronic medical conditions. If the individual responds No to all follow-up items, they are cleared to become more physically active. If a respondent answers Yes to one or more of these supplementary questions, they are referred to the electronic Physical Activity Readiness Medical Examination (ePARmed-X+; www.eparmedx.com), or to consult with a health professional qualified to prescribe exercise (19). Through this screening process, the vast majority of participants are able to self-clear for physical activity or exercise (36). Also, while the document has a total of 48 items, completing the tool is straightforward and takes ~5 min (19). Additionally, this new questionnaire was recently published in a digital format, thus providing the advantage of online completion (37).

Although chronic medical conditions are the primary cause of mortality in high-income countries, such as in Canada, these diseases affect low- and middle-income countries in a much higher proportion, with more than 75% of worldwide deaths from such diseases occurring in these nations (38, 39). This is the case of Brazil, a middle-income country, where chronic diseases are also a leading health problem (40). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the main causes of deaths in the country were cancer and cardiovascular disease, which are directly linked to obesity (41, 42). The prevalence of obesity has been dramatically increasing in the country, with 12% of the youth population, as well as 20% of adults and 21% of older adults being considered obese in Brazil (43, 44). In large part, this scenario is due to sedentary lifestyles (45). Physical inactivity, a preeminent behavioral risk factor for chronic diseases and early mortality, is one of the most prevalent unhealthy behaviors in Brazilians (46, 47). According to studies about perceived barriers to physical activity in Brazil, having a disease and being afraid of getting injured are also among the main reasons preventing minors, adults, and the elderly from becoming more physically active (48–50). The country has one of the world's fastest aging populations, and over 70% of Brazilian seniors are considered insufficiently active (51, 52). This prevalence is 61% for adults (44) and over 80% for children and adolescents in the country (53).

Since the fear of worsening their health condition is among the main barriers to physical activity in Brazilians, an instrument like the PAR-Q+, validated to Brazilian Portuguese, could be crucial to allow numerous individuals to safely start or increase physical activity participation. Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to translate, culturally adapt, and verify the reproducibility of the questionnaire to the Brazilian context.

Methods

This study was designed in two phases. Initially, the questionnaire was translated and culturally adapted to the targeted language. Subsequently, a test re-test procedure was adopted with different age groups to verify reproducibility.

Translation and Adaptation

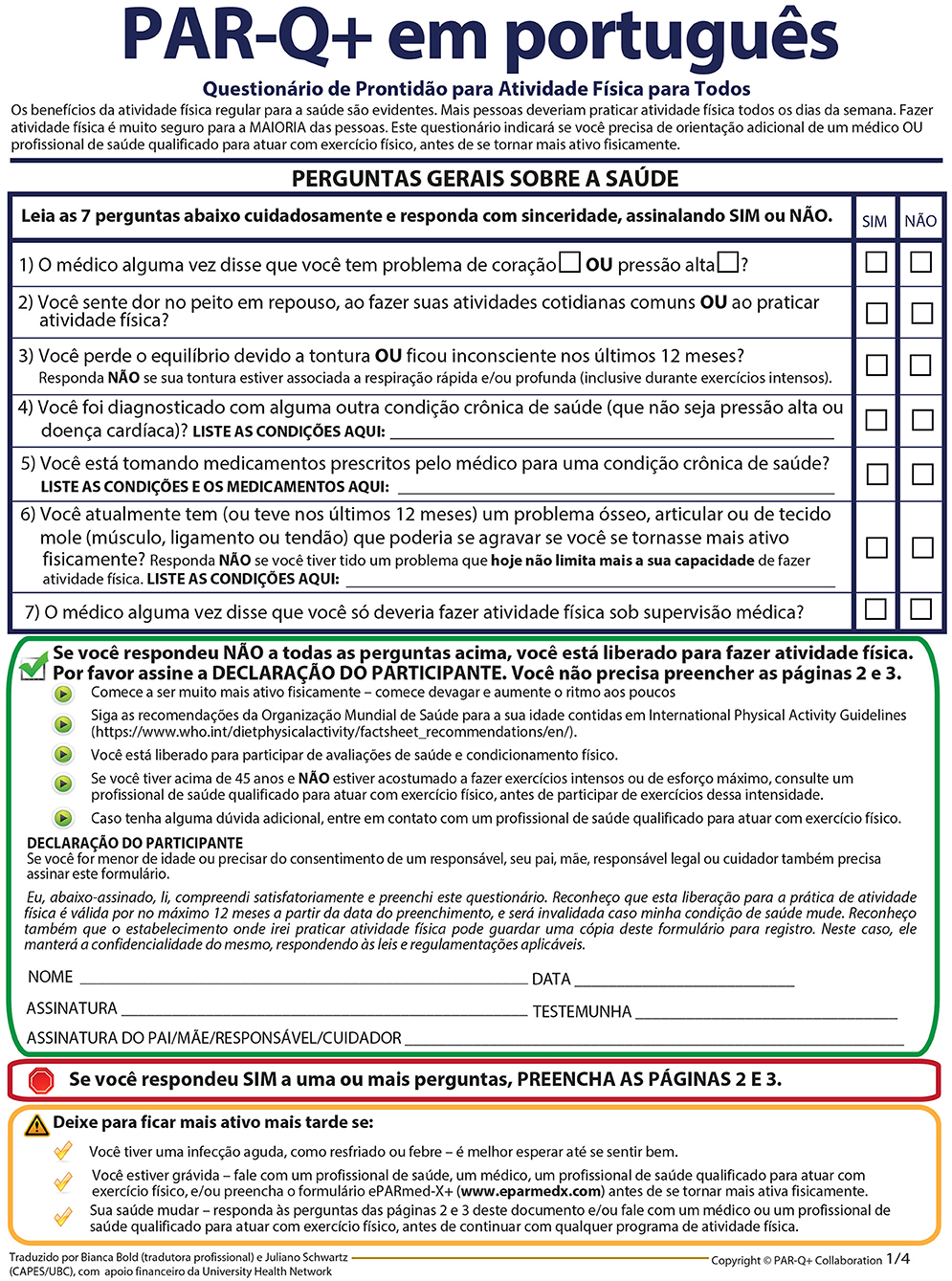

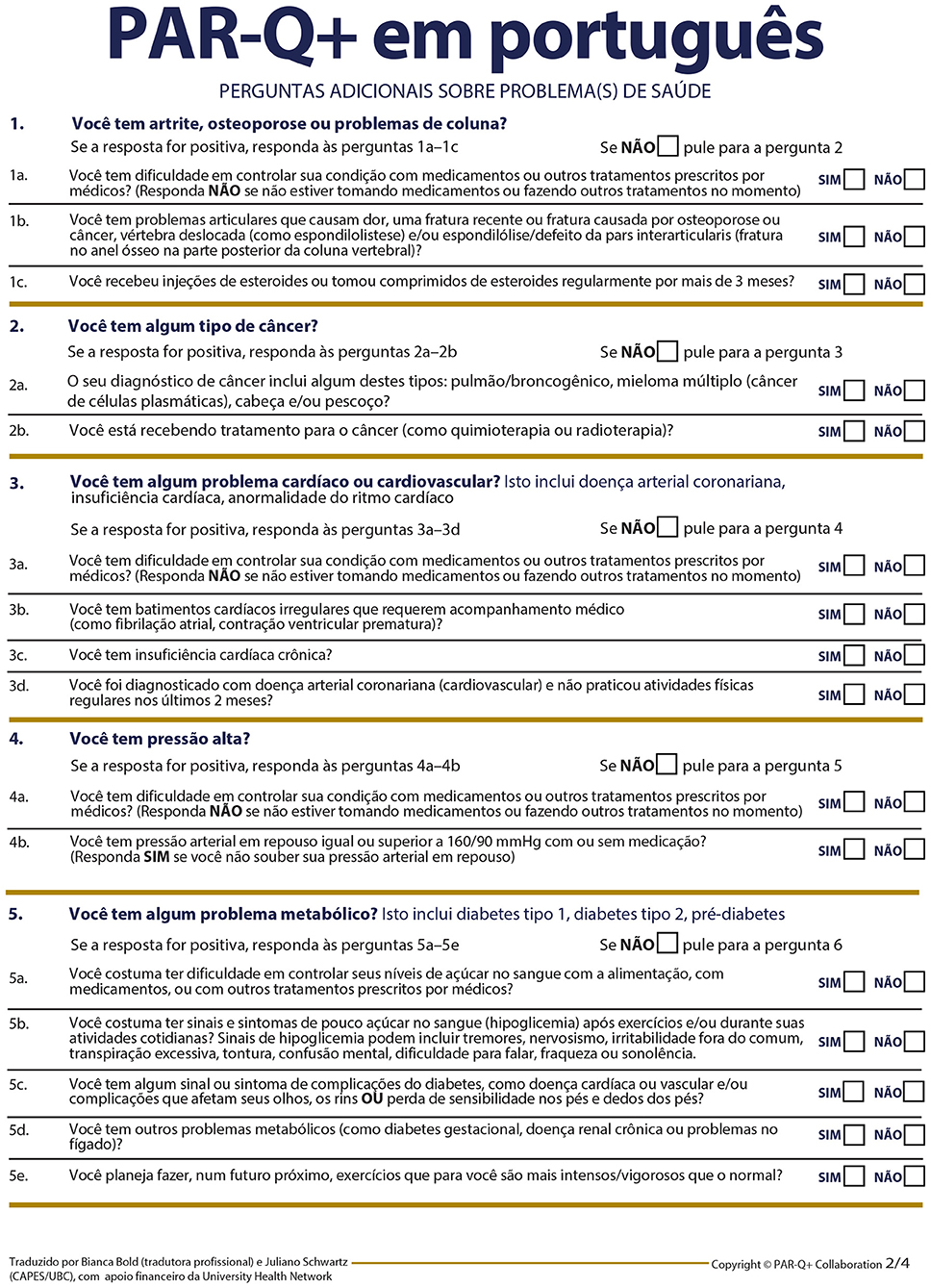

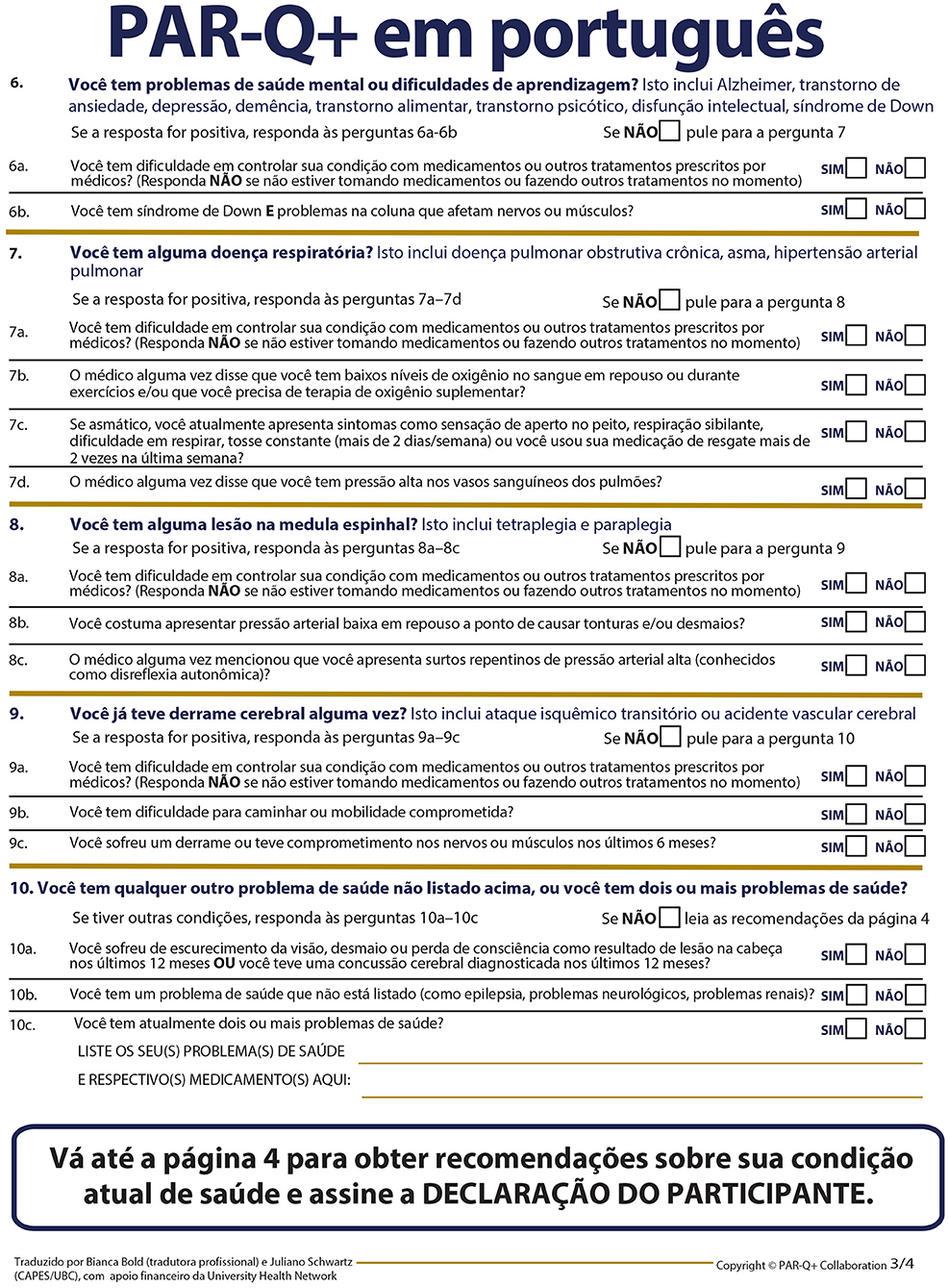

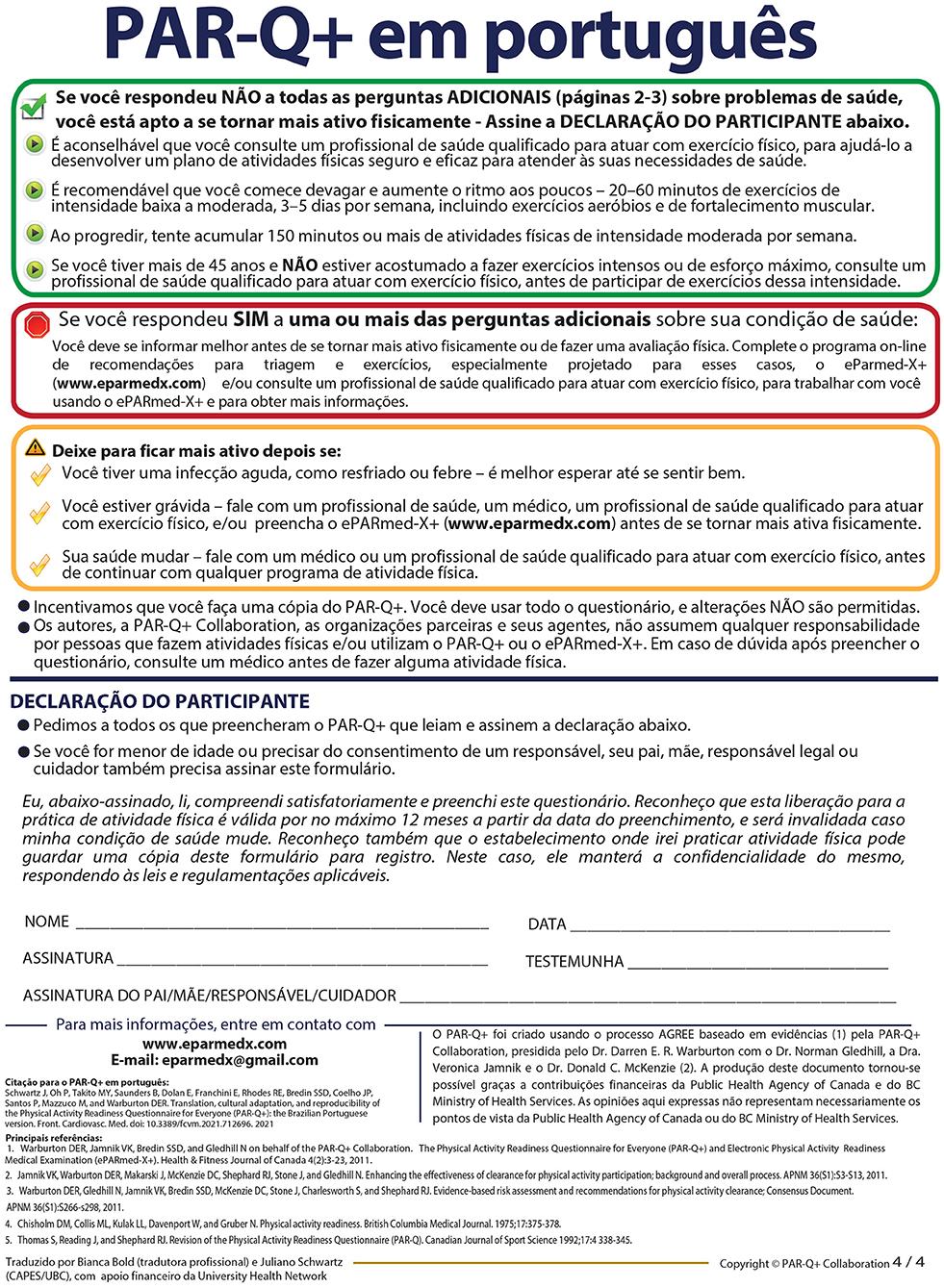

Permission to develop the Brazilian Portuguese version of the document was granted from the organization in charge of the questionnaire (i.e., the PAR-Q+ Collaboration). The screening tool was first translated into Brazilian Portuguese by two independent translators who speak Brazilian Portuguese as their native language. A group of Brazilian experts in health and physical activity then came together to produce a combined initial version. Overall, the experts involved in validating the PAR-Q+ in Brazilian Portuguese agreed with the translators' versions. Only a couple of minor phrasing adjustments were necessary to culturally adapt the PAR-Q+ to the Brazilian context. The next step was for two native English speakers, fluent in Brazilian Portuguese and accustomed to the Brazilian culture, with no previous exposure to the original PAR-Q+, to back-translate the questionnaire into English. When assessing these back-translations, the PAR-Q+ Collaboration noted a few terms slightly different from the original document. These were considered to have occurred due to the choice of terms in Brazilian Portuguese to allow a better understanding of the questionnaire by the Brazilian population, and these adaptations did not modify the original meaning. After having its accuracy ensured, a final version was approved (see Appendix 1).

Field Testing

To assess the reproducibility of the translated version, Brazilians living in Brazil and abroad responded to the questionnaire on two separate occasions, 1–2 weeks apart. A total of 567 individuals attending health and fitness facilities as well as members from the general public, male and female from all age groups, were invited to take part in this project. There were no exclusion criteria. However, 74 individuals did not complete the questionnaire for the second time, mainly due to schedule incompatibility. Therefore, the sample was composed of 493 participants (59% female), between 5 and 93 years old (39.9 ± 25.4 yr). A total of 114 were children and adolescents, 252 were adults, and 127 were older adults. The questionnaire was administered in person to 84 individuals in a lifestyle management program focusing on chronic disease prevention, 11 clients at a physiotherapy clinic, 24 participants of a fitness project, 14 members of a CrossFit gym, and 43 patients from a rehabilitation center. The remaining 317 questionnaires were completed online. Respondents represented a variety of health status cohorts such as clinical populations, healthy individuals, athletes, and non-competitive exercisers. As per the guidelines of the PAR-Q+, those under the legal age had the questionnaire completed by their parents/guardians. In all settings and forms of application the participants were welcomed to provide comments, if any, about their understanding of the document. Participants also reported the time taken to answer the questionnaire for the first time.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS for Windows (version 27.0). Using a 95% confidence interval, Kappa was calculated to evaluate the reproducibility of each question between the two applications (54). Additionally, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to verify the total reproducibility (reliability) (55). The sum of all positive questions was compared between the first and the second times the questionnaire was administered. The criteria for agreement was as follows: 0.0–0.20 (poor), 0.21–0.40 (fair), 0.41–0.6 (moderate), 0.61–0.8 (substantial), and 0.81–1.0 (almost perfect) (56). Internal consistency was calculated with Cronbach's alpha, using all initial and follow-up questions of the translated version. Significance level was set at 5% for all tests.

Results

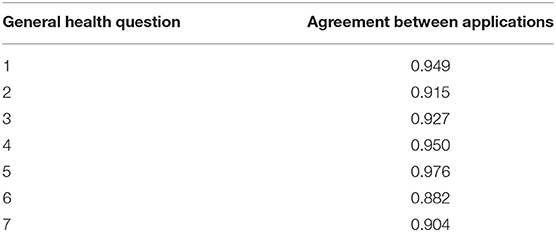

The Brazilian Portuguese version of the PAR-Q+ had excellent internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.993. In terms of reproducibility, out of the 48 items of the questionnaire, 45 (93.8%) had an almost perfect agreement between the first and second applications, and three (6.2%) had a substantial agreement (follow-up questions 2a, 5e, and 8b). The translated version of the questionnaire had a good to excellent general reproducibility (ICC = 0.901, 95% CI: 0.887–0.914). Specifically, as shown in Table 1, every one of the seven general health questions of the questionnaire had an almost perfect agreement.

Table 1. Kappa value for each general health question between two applications of the Brazilian version of the PAR-Q+.

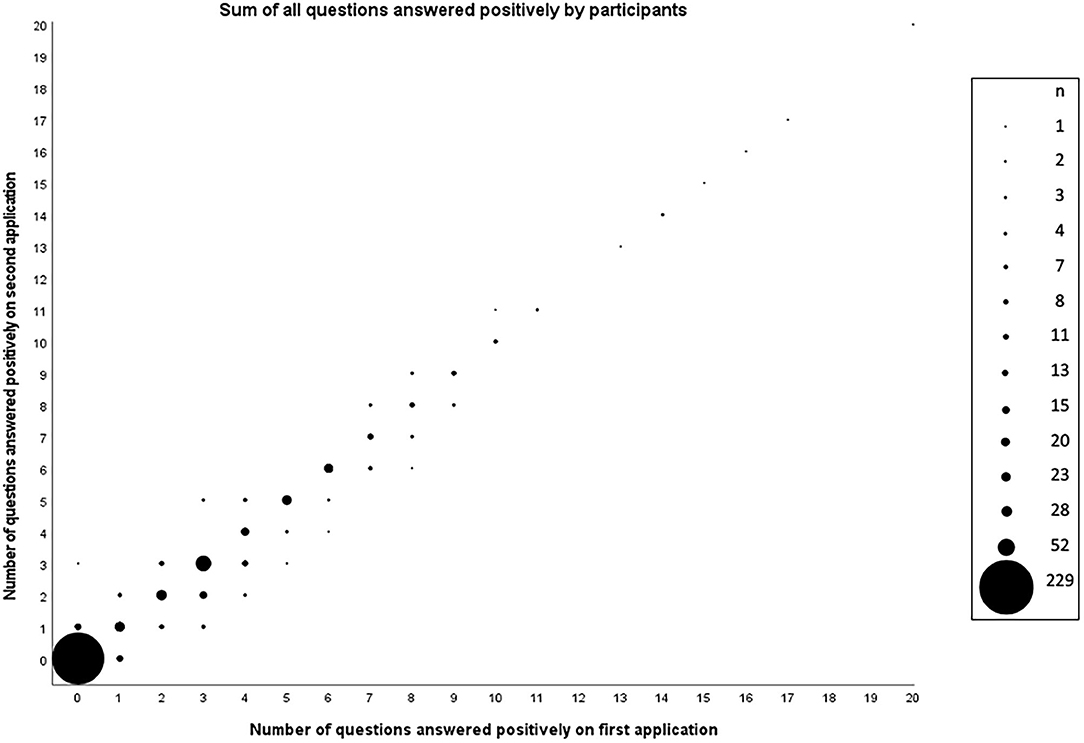

The maximum of questions answered positively was 20. A total of 405 (82.2%) participants provided the same answer to every question they answered both times they completed the questionnaire. Out of those, 229 answered negatively to all questions. For those individuals who did not have the same answer for all questions in both applications, 62 had one different answer, 16 responded two questions with different answers, and 10 had three answers that did not match. Figure 1 shows the comparison of the sum of questions answered positively between the first and the second administrations of the questionnaire.

Figure 1. Number of questions answered positively by participants (n = 493) in the first and second applications of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the PAR-Q+.

The time reported to answer the PAR-Q+ in Brazilian Portuguese was 4.4 ± 2.3 min. After answering the questionnaire, a few participants provided their opinion about their comprehension of the questionnaire. Two individuals taking medication reported uncertainty about how to answer the following question: Do you have difficulty controlling your condition with medications or other physician-prescribed therapies? (Answer NO if you are not currently taking medications or other treatments). Since their health conditions were under control, these individuals received clarification from the researcher, explaining they should answer negatively. No other concern was raised by any participant.

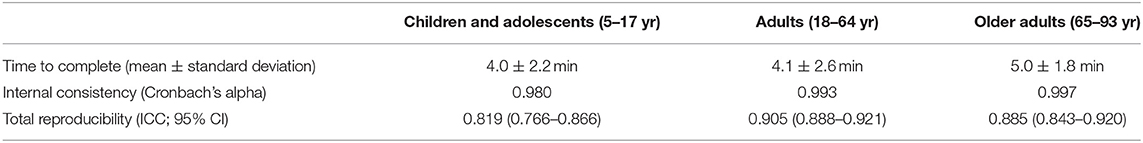

Specifically, the subsample of children and adolescents had 46 questions (95.8%) presenting an almost perfect agreement and two questions (4.2%) presenting a substantial agreement: follow-up items 1 and 5e. The group of adults also had 46 items (95.8%) with an almost perfect agreement, and two items (4.2%) with a substantial agreement, namely follow-up questions 7c and 8b. In the subsample of older adults, 45 questions (93.8%) had an almost perfect agreement and three questions (6.2%) had a substantial agreement: follow-up items 4a, 5a, and 6. All age groups had excellent internal consistency. The group of children and adolescents had a good general reproducibility, and the other two subsamples, adults and older adults, had a good to excellent total reproducibility. The time reported to answer the questionnaire, the internal consistency, as well as the general reproducibility for each one of the age groups are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Time to complete the questionnaire, internal consistency, and total reproducibility according to each age group of individuals to validate the Brazilian Portuguese version of the PAR-Q+.

Discussion

The Brazilian version of the PAR-Q+ showed strong reproducibility, with all items demonstrating an agreement between substantial and almost perfect in the whole sample, as well as in each age group. This strong reproducibility is similar to the one presented by the sample of Spanish speakers, which also had all questions in these categories of agreement (57).

The PAR-Q+ was initially developed in two languages, English and French, since it was created in Canada, which is a bilingual country (58, 59). To date, the questionnaire has been officially translated into Spanish, and multiple other translation processes are in progress (57). The study about the Spanish version analyzed the participants as a single group, which had 47 items presenting an almost perfect agreement and only one presenting a substantial agreement. In the whole sample of the Brazilian study this proportion was slightly different, with 45 items presenting an almost perfect agreement and three presenting substantial agreement. There are a number of potential explanations for this variation. The Brazilian Portuguese document was validated with almost triple the sample size than the Spanish version (177 participants), and with some individuals much younger and others much older than the participants in that study (13–85 years old). Also, most individuals in the Brazilian version answered the questionnaire online. Both of these factors could be considered strengths of the current validation, given that the larger age range increases the representativeness of the population, while the online application allows for a more widespread application. It is also possible, however, that these aspects led to a couple of answers being less consistent, which could explain the slightly higher number of questions below an almost perfect agreement. However, when providing feedback about their understanding of the questionnaire, other than two individuals requiring further clarification about one question, no additional concerns were raised.

For the whole sample and for each age group, all of the seven initial questions of the Brazilian version had an almost perfect agreement. However, it is possible that some participants did not pay full attention to all follow-up questions when answering the questionnaire for the second time. This may be a factor for those who answered the PAR-Q+ online by themselves, without the presence of a health/fitness professional. According to Kung et al. (60), a low rate of inattentive answers is expected in any research based on survey responses, and this rate can be higher if there is little or no incentive for respondents to complete a survey. Although our participants voluntarily accepted to participate in the study and received a sound and thorough explanation about the research's importance and how to proceed, they were not financially compensated. Additionally, according to Schneider et al. (61), who examined self-administered and internet-based questions on quality of life, some individuals may provide careless responses when there is a lack of personal, face-to-face interaction. This is supported by Meade and Craig (62), who pointed out that the distance from the respondent to the professional in charge of the questionnaire can lead to less accountability when completing the survey. An additional possible cause of some level of inattention is the need to repeatedly answer the same questionnaire in a short period of time (63, 64). This could have been a factor in the present study, since the validation process required participants to answer the same questionnaire twice, seven to 14 days apart. However, in real-life situations, this repetitive process will not be necessary to start or increase participation in physical activity, as per the questionnaire guidelines individuals will only have to respond once within any 12-month period, unless there is a change in their health conditions. Furthermore, in their validation study of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire in 12 countries, Craig et al. (65) noted that longer questionnaires can be seen as boring and repetitive. Although the PAR-Q+ has many more questions than the previous PAR-Q, this innovative format, with the initial and the follow-up evidenced-based questions, is what makes this new screening tool unique, in providing physical activity clearance to 99% of its respondents without needing to be referred to a physician (66). Nevertheless, we showed that the Brazilian Portuguese version of the PAR-Q+, like the original document, takes approximately only 5 min to complete (19).

This questionnaire does not require that every individual who answers positively to one or more of the health general questions obtains clearance from a physician, making it a convenient screening tool in high- as well as in low- and middle-income nations. In industrialized countries, where the offer of medical services is usually sufficient for most the population, providing clearance for physical activity is often considered a time consuming and cumbersome process by physicians (67). Removing unnecessary consultations with this health professional before participating in physical activity or in a fitness appraisal is especially important in lower-income countries like Brazil, since due to social inequities in health, a large number of individuals have limited access to medical professionals (68). In fact, there is a need for low-cost and accurate self-assessment tools related to physical activity that can be utilized around the world in different cultures and ethnic groups (69). Specifically, effective screening provides a significant contribution to maximize physical activity engagement at the population level (16). Accordingly, having the PAR-Q+ properly translated and culturally validated to the Brazilian Portuguese language can contribute to greater numbers of individuals to safely start or increase physical activity participation.

Limitations

While the present study has a considerable sample size, with individuals living in different locations, this cohort is not necessarily representative of the entire Brazilian population. To address this issue, participants were recruited in the most populous city in the country (São Paulo), which contains individuals from all Brazilian states. Participants were also recruited in two other major cities: Campinas and Vancouver (Canada). Another limitation was the fact that the cognitive debrief happened during the data collection instead of at a specific pre-test moment. The intention was to allow every participant to provide feedback about their understanding of the questionnaire.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this study it can be concluded that, overall, Brazilians of different ages, male and female, healthy or living with chronic medical conditions, had no difficulty in understanding the translated and adapted version of the questionnaire. The results also indicate that participants were able to similarly complete the Brazilian Portuguese version of the PAR-Q+ on two independent occasions, showing the strong reproducibility of the questionnaire. Altogether, these outcomes demonstrate that the PAR-Q+ in Brazilian Portuguese is a valid and reliable screening tool. It is expected that nationwide implementation of the questionnaire could allow a substantial number of Brazilians to safely engage in more physical activity participation, as well as in fitness assessments, providing ways to enhance wellness and to contribute toward the prevention and management of chronic diseases in this population.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research and Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

JS and PO designed the study. JS, MT, BS, ED, JC, and MM were responsible for data collection. JS and MT were responsible for statistical analyses. JS drafted the manuscript. PO, MT, BS, ED, EF, RR, SB, JC, PdS, MM, and DW critically revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES 2185-15-6 to JS); Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP 2016/50438-0 to BS, 2019/05616-6 and 2019/26899-6 to ED); Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (FMUSP 2020.1.362.5.2 to BS); and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq 301003/2019-0 to EF).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation Program, Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, University Health Network for the financial support, Vinicius de Oliveira Damasceno and Tony Meireles dos Santos for their contributions, and all the participants for volunteering their time.

References

1. Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. (2012) 380:219–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9

2. Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine–evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports. (2015) 25:1–72. doi: 10.1111/sms.12581

3. Rhodes RE, Janssen I, Bredin SSD, Warburton DER, Bauman A. Physical activity: health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychol Health. (2017) 32:1–34. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2017.1325486

4. Schwartz J, Rhodes R, Bredin SS, Oh P, Warburton DE. Effectiveness of approaches to increase physical activity behavior to prevent chronic disease in adults: a brief commentary. J Clin Med. (2019) 8:295. doi: 10.3390/jcm8030295

5. Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJF, Martin BW, et al. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet. (2012) 380:258–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1

6. Schutzer KA, Graves BS. Barriers and motivations to exercise in older adults. Prev Med. (2004) 39:1056–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.003

7. Burton E, Farrier K, Lewin G, Pettigrew S, Hill A-M, Airey P, et al. Motivators and barriers for older people participating in resistance training: a systematic review. J Aging Phys Act. (2017) 25:311–24. doi: 10.1123/japa.2015-0289

8. Herazo-Beltrán Y, Pinillos Y, Vidarte J, Crissien E, Suarez D, García R. Predictors of perceived barriers to physical activity in the general adult population: a cross-sectional study. Braz J Phys Ther. (2017) 21:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2016.04.003

9. Granger CL, Connolly B, Denehy L, Hart N, Antippa P, Lin K-Y, et al. Understanding factors influencing physical activity and exercise in lung cancer: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. (2017) 25:983–99. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3484-8

10. Mazzuca P, Montesi L, Mazzoni G, Grazzi G, Micheli MM, Piergiovanni S, et al. Supervised vs. self-selected physical activity for individuals with diabetes and obesity: the Lifestyle Gym program. Intern Emerg Med. (2017) 12:45–52. doi: 10.1007/s11739-016-1506-7

11. Chisholm DM, Collis ML, Kulak LL, Davenport W, Gruber N. Physical activity readiness. B C Med J. (1975) 17:375–8.

12. Warburton DE, Gledhill N, Jamnik VK, Bredin SS, McKenzie DC, Stone J, et al. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: Consensus Document 2011. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2011) 36:S266–98. doi: 10.1139/h11-062

13. Warburton DE, Jamnik VK, Bredin SS, McKenzie DC, Stone J, Shephard RJ, et al. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: an introduction. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2011) 36(Suppl. 1):S1–2. doi: 10.1139/h11-060

14. Thomas S, Reading J, Shephard RJ. Revision of the physical activity readiness questionnaire (PAR-Q). Can J Sport Sci. (1992) 17:338–45.

15. Jamnik VK, Gledhill N, Shephard RJ. Revised clearance for participation in physical activity: greater screening responsibility for qualified university-educated fitness professionals. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2007) 32:1191–7. doi: 10.1139/H07-128

16. Shephard RJ. Qualified fitness and exercise as professionals and exercise prescription: evolution of the PAR-Q and Canadian aerobic fitness test. J Phys Act Health. (2015) 12:454–61. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2013-0473

17. Shephard RJ. Does insistence on medical clearance inhibit adoption of physical activity in the elderly? J Aging Phys Act. (2000) 8:301–11. doi: 10.1123/japa.8.4.301

18. WHO. Global Health Aging. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2011).

19. Bredin SS, Gledhill N, Jamnik VK, Warburton DE. PAR-Q+ and ePARmed-X+: new risk stratification and physical activity clearance strategy for physicians and patients alike. Can Fam Phys. (2013) 59:273–7.

20. Warburton DER, Jamnik VK, Bredin SSD, Gledhill N. Enhancing the effectiveness of the PAR-Q and PARmed-X screening for physical activity participation. J Phys Act Health. (2010) 7(Suppl. 3):S338−40.

21. Cardinal BJ, Cardinal MK. Screening efficiency of the revised physical activity readiness questionnaire in older adults. J Aging Phys Act. (1995) 3:299–308. doi: 10.1123/japa.3.3.299

22. Armstrong M, Paternostro-Bayles M, Conroy MB, Franklin BA, Richardson C, Kriska A. Preparticipation screening prior to physical activity in community lifestyle interventions. Transl J Am Coll Sports Med. (2018) 3:176. doi: 10.1249/TJX.0000000000000073

23. Asch SM, Kerr EA, Keesey J, Adams JL, Setodji CM, Malik S, et al. Who is at greatest risk for receiving poor-quality health care? N Engl J Med. (2006) 354:1147–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa044464

24. Tulimiero M, Garcia M, Rodriguez M, Cheney AM. Overcoming barriers to health care access in rural latino communities: an innovative model in the eastern coachella valley. J Rural Health. (2021) 37:635–44. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12483

25. Charlesworth S, Foulds HJA, Burr JF, Bredin SSD. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: pregnancy. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2011) 36:S33–48. doi: 10.1139/h11-061

26. Chilibeck PD, Vatanparast H, Cornish SM, Abeysekara S, Charlesworth S. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity: arthritis, osteoporosis, and low back pain. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2011) 36:S49–79. doi: 10.1139/h11-037

27. Eves ND, Davidson WJ. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: respiratory disease. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2011) 36:S80–100. doi: 10.1139/h11-057

28. Goodman JM, Thomas SG, Burr J. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for exercise testing and physical activity clearance in apparently healthy individuals. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2011) 36:S14–32. doi: 10.1139/h11-048

29. Jones LW. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: cancer. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2011) 36:S101–12. doi: 10.1139/h11-043

30. Rhodes RE, Temple VA, Tuokko HA. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: cognitive and psychological conditions. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2011) 36:S113–53. doi: 10.1139/h11-041

31. Riddell MC, Burr J. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: diabetes mellitus and related comorbidities. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2011) 36:S154–89. doi: 10.1139/h11-063

32. Thomas SG, Goodman JM, Burr JF. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: established cardiovascular disease. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2011) 36:S190–213. doi: 10.1139/h11-050

33. Zehr EP. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: stroke and spinal cord injury. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2011) 36:S214–31. doi: 10.1139/h11-055

34. Warburton DER, Bredin SSD, Charlesworth SA, Foulds HJA, McKenzie DC, Shephard RJ. Evidence-based risk recommendations for best practices in the training of qualified exercise professionals working with clinical populations. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. (2011) 36:S232–65. doi: 10.1139/h11-054

35. Warburton DER, Bredin SSD, Jamnik VK, Gledhill N. Validation of the PAR-Q+ and ePARmed-X+. Health Fitness J Can. (2011) 4:38–46. doi: 10.14288/hfjc.v4i2.151

36. Warburton DER, Gledhill N, Jamnik VK, Bredin SSD, McKenzie DC, Stone J, et al. International launch of the PAR-Q+ and ePARmed-X. The physical activity readiness questionnaire (PAR-Q+) and electronic physical activity readiness medical examination (ePARmed-X+): summary of consensus panel recommendations. Health Fitness J Can. (2011) 4:26–37. doi: 10.14288/hfjc.v4i2.103

37. Warburton DE, Jamnik V, Bredin SS, Shephard RJ, Gledhill N. The 2019 physical activity readiness questionnaire for everyone (PAR-Q+) and electronic physical activity readiness medical examination (ePARmed-X+). Health Fitness J Can. (2018) 11:80–3. doi: 10.14288/hfjc.v11i4.270

38. Varin M, Baker M, Palladino E, Lary T. Canadian chronic disease indicators, 2019 - updating the data and taking into account mental health. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. (2019) 39:281. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.39.10.02

39. Ranasinghe PD, Pokhrel S, Anokye NK. Economics of physical activity in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ open. (2021) 11:e037784. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037784

40. Enes CC, Nucci LB. A telephone surveillance system for noncommunicable diseases in Brazil. Public Health Rep. (2019) 134:324–7. doi: 10.1177/0033354919848741

41. Triaca LM, Jacinto PdA, França MTA, Tejada CAO. Does greater unemployment make people thinner in Brazil? Health Econ. (2020) 29:1279–88. doi: 10.1002/hec.4139

42. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de Informática do SUS – DATASUS. Informações de Saúde, Epidemiológicas e Morbidade: banco de dados. (2019). Available from: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?sim/cnv/obt10uf.def (accessed October 19, 2020).

43. Ferreira CM, Reis NDD, Castro AO, Höfelmann DA, Kodaira K, Silva MT, et al. Prevalence of childhood obesity in Brazil: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr. (2021). doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2020.12.003. [Epub ahead of print].

44. Brasil. Vigitel Brasil 2019: vigilância de fatores de risco e proteção para doenças crônicas por inquérito telefônico: estimativas sobre frequência e distribuição sociodemográfica de fatores de risco e proteção para doenças crônicas nas capitais dos 26 estados brasileiros e no Distrito Federal em 2019. Brasilia: Ministerio da saude (2020).

45. Dunker KLL, Alvarenga MDS, Teixeira PC, Grigolon RB. Effects of participation level and physical activity on eating behavior and disordered eating symptoms in the Brazilian version of the New Moves intervention: data from a cluster randomized controlled trial. São Paulo Med J. (2021) 139:269–78. doi: 10.1590/1516-3180.2020.0420.r2.04022021

46. Ekelund U, Steene-Johannessen J, Brown WJ, Fagerland MW, Owen N, Powell KE, et al. Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet. (2016) 388:1302–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30370-1

47. Silva DA, Rinaldi AEM, Azeredo CM. Clusters of risk behaviors for noncommunicable diseases in the Brazilian adult population. Int J Public Health. (2019) 64:821–30. doi: 10.1007/s00038-019-01242-z

48. Cruz MS, Garcia LMT, Andrade DR, Florindo AA. Barriers to leisure-time physical activity in adults living in a low socioeconomic area of the Brazilian Southeast. Rev Bras Ativ Fis e Saúde. (2018) 23:1–9. doi: 10.12820/rbafs.23e0041

49. Rech CR, Camargo EMd, Araujo PABd, Loch MR, Reis RS. Perceived barriers to leisure-time physical activity in the brazilian population. Rev Bras Med Esporte. (2018) 24:303–9. doi: 10.1590/1517-869220182404175052

50. Sousa AW, Cabral ALB, Martins MA, Carvalho CR. Barriers to daily life physical activities for Brazilian children with asthma: a cross-sectional study. J Asthma. (2020) 57:575–83. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2019.1594249

51. Lima-Costa MF. Aging and public health: the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSI-Brazil). Rev Saude Publica. (2018) 52:2s. doi: 10.11606/S1518-8787.2018052000supl1ap

52. Souza AMR, Fillenbaum GG, Blay SL. Prevalence and correlates of physical inactivity among older adults in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0117060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117060

53. Mendes AA, Lopes WA, Locateli JC, Oliveira GHd, Bim RH, Simões CF, et al. The prevalence of Active Play in Brazilian children and adolescents: a systematic review. Rev Bras Cineantr Desempenho Hum. (2018) 20:395–405. doi: 10.5007/1980-0037.2018v20n4p395

54. Mackinnon A. A spreadsheet for the calculation of comprehensive statistics for the assessment of diagnostic tests and inter-rater agreement. Comp Biol Med. (2000) 30:127–34. doi: 10.1016/S0010-4825(00)00006-8

55. Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. (2016) 15:155–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

56. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. (1977) 33:159–74. doi: 10.2307/2529310

57. Schwartz J, Mas-Alòs S, Takito MY, Martinez J, Cueto MEÁ, Mibelli MSR, et al. Cross-cultural translation, adaptation, and reliability of the Spanish version of the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone (PAR-Q+). Health Fitness J Can. (2019) 12:3–14. doi: 10.14288/hfjc.v12i4.291

58. Warburton DER, Jamnik V, Bredin SSD, Gledhill N. The 2011 physical activity readiness questionnaire for everyone (PAR-Q+): French North America Version (Questionnaire sur l'aptitude à l'activité physique pour tous (2011 Q-AAP+)). Health Fitness J Can. (2011) 4:21–3. doi: 10.14288/hfjc.v4i2.107

59. Warburton DER, Jamnik VK, Bredin SSD, Gledhill N. The physical activity readiness questionnaire for everyone (PAR-Q+): English North America Version. Health Fitness J Can. (2011) 4:18–20. doi: 10.14288/hfjc.v4i2.106

60. Kung FYH, Kwok N, Brown DJ. Are attention check questions a threat to scale validity? Appl Psychol. (2018) 67:264–83. doi: 10.1111/apps.12108

61. Schneider S, May M, Stone AA. Careless responding in internet-based quality of life assessments. Qual Life Res. (2018) 27:1077–88. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1767-2

62. Meade AW, Craig SB. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychol Methods. (2012) 17:437. doi: 10.1037/a0028085

63. Conijn JM, Franz G, Emons WHM, De Beurs E, Carlier IVE. The assessment and impact of careless responding in routine outcome monitoring within mental health care. Multivariate Behav Res. (2019) 54:593–611. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2018.1563520

64. Wardell JD, Rogers ML, Simms LJ, Jackson KM, Read JP. Point and click, carefully: investigating inconsistent response styles in middle school and college students involved in web-based longitudinal substance use research. Assessment. (2014) 21:427–42. doi: 10.1177/1073191113505681

65. Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2003) 35:1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB

66. Joy EA, Pescatello LS. Pre-exercise screening: role of the primary care physician. Isr J Health Policy Res. (2016) 5:29. doi: 10.1186/s13584-016-0089-0

67. Warburton DER, Jamnik VK, Bredin SSD, Burr J, Charlesworth S, Chilibeck P, et al. Executive summary: the 2011 physical activity readiness questionnaire for everyone (PAR-Q+) and the electronic physical activity readiness medical examination (ePARmed-X+). Health Fitness J Can. (2011) 4:24–5. doi: 10.14288/hfjc.v4i2.104

68. Boccolini CS, de Souza Junior PRB. Inequities in healthcare utilization: results of the Brazilian National Health Survey, 2013. Int J Equity Health. (2016) 15:150. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0444-3

69. Sebastiao E, Gobbi S, Chodzko-Zajko W, Schwingel A, Papini CB, Nakamura PM, et al. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire-long form overestimates self-reported physical activity of Brazilian adults. Public Health. (2012) 126:967–75. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.07.004

Appendix 1

Keywords: health, exercise, cardiovascular disease, physical activity, risk stratification, translation

Citation: Schwartz J, Oh P, Takito MY, Saunders B, Dolan E, Franchini E, Rhodes RE, Bredin SSD, Coelho JP, dos Santos P, Mazzuco M and Warburton DER (2021) Translation, Cultural Adaptation, and Reproducibility of the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone (PAR-Q+): The Brazilian Portuguese Version. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8:712696. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.712696

Received: 21 May 2021; Accepted: 05 July 2021;

Published: 26 July 2021.

Edited by:

Sebastian Kelle, Deutsches Herzzentrum Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Lígia Mendes, Hospital da Luz Setúbal, PortugalLuís Cavalheiro, Escola Superior de Tecnologia da Saúde de Coimbra, Portugal

Copyright © 2021 Schwartz, Oh, Takito, Saunders, Dolan, Franchini, Rhodes, Bredin, Coelho, dos Santos, Mazzuco and Warburton. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Juliano Schwartz, anVsaWFub2Zpc2lvQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Juliano Schwartz

Juliano Schwartz Paul Oh

Paul Oh Monica Y. Takito

Monica Y. Takito Bryan Saunders

Bryan Saunders Eimear Dolan

Eimear Dolan Emerson Franchini

Emerson Franchini Ryan E. Rhodes

Ryan E. Rhodes Shannon S. D. Bredin1

Shannon S. D. Bredin1 Josye P. Coelho

Josye P. Coelho Pedro dos Santos

Pedro dos Santos Melina Mazzuco

Melina Mazzuco Darren E. R. Warburton

Darren E. R. Warburton