95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Conserv. Sci. , 05 April 2023

Sec. Human-Wildlife Interactions

Volume 4 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2023.1126168

This article is part of the Research Topic Decolonizing Human and Non-human Coexistence View all 7 articles

The Government of India’s twin objectives of protecting the tiger population in the Nallamala forest and providing “development” to the indigenous Chenchu people have resulted in an ongoing process of displacement of the Chenchu people from the forest to the town fringes. While the conservation-displacement nexus has bridged new anthropocentric pathways for development, it has also created deeper crevices in the innate relationships of the Chenchu with the forests and tigers. The research uses a bottom-up approach to present on-the-ground realities of conservation and development policies of the Indian Government and the Chenchu people, particularly, the Chenchu’s development expectations, relationship with the forest and tigers, and displacement views as well as the government’s tiger conservation objectives, development promises, and perspectives on Chenchu development and forest conservation. The paper is a comparative study of the definitions of “development” held by the internally displaced Chenchu people and the Indian government representatives of the Integrated Tribal Development Agency and the Nagarjunasagar Srisailam Tiger Reserve, and the local non-government organizations that collaborate with the Government.

Land, animals, ecologies, natural resources – why are they protected? While the answer may be complicated, one response is that they represent microcosms of varied identities that enable and enrich a macrocosm of a diverse culture, society, or nation. When biodiversity conservation becomes the State’s agenda, it regulates the common use of natural resources thus creating a complex situation of conservation-displacement tradeoffs. Species and ecosystems conservation is spatial (Agrawal and Redford, 2009), and human interference, in the form of land fragmentation, human-wildlife conflict, or hunting in spaces designated for biodiversity conservation, is seen as a hindrance to conservation goals (Karanth and Krithi, 2007). To achieve these goals, displacement of people from protected areas becomes a viable option for the State. Poverty alleviation of displaced communities, in terms of jobs, medical facilities, houses, and education, is seen as one of the possible tradeoffs of conservation-induced displacement; however, there is no solid evidence that conservation indeed leads to socio-economic development (Agrawal and Redford, 2006). Challenges such as adapting to new locations, cultures, living conditions, and competition for basic necessities with the natives of the new territories are commonly encountered by displaced communities (Koenig, 2001). In addition, (Cernea, 1997, p. 1569) argues that development-induced displacement causes enormous psychological and cultural stress to displaced communities as there is more focus on development projects in the native locations of the displaced people rather than effective compensation for a better livelihood.

Focusing on India, the environmental and conservation consciousness can always be traced back to ancient Indian religious, political, and social spaces that provided significant platforms for animal and forest protection. The Arthaśāstra, a magnum opus by Kautilya, the 4th century BCE Indian political strategist and philosopher, codified reckless hunting as an unpardonable crime and designated forests as abhaya aranyas or “forests without fear,” making them safer sanctums of animal protection (Bagchi and Jha, 2011). The conservation campaign by Emperor Ashoka (273-232 BCE) set ground rules for the protection of a variety of animals. Ashokan inscriptions on stone pillars erected India-wide (the Pillar Edict V) detailed a list of animals that must not be killed under any circumstances in order to regulate the senseless killing of animals (Bagchi and Jha, 2011). However, the conservation ideologies of ancient India must not be taken in their entirety as royalty, and later the British and elites, indeed engaged in sport hunting of endangered and wild animals, including the Royal Bengal Tiger (Panthera tigris tigris), hereafter tiger. The tiger holds a prominent position in the Indian cultural, social, and religious arenas. While many Hindu cultures revere the big cat as an avatar of divinity, it is an epitome of a near-distant relative, sometimes as a barho mia (elder brother) or a mama (maternal uncle), in the mindscapes of many forest-dwelling tribal groups in India (Aiyadurai, 2016; Mondal and Das, 2023). However, during colonial rule in India, the British viewed tiger hunting as a way of attaining imperial domination over not only India’s politics but also its natural resources (Sramek, 2006). Even after Indian independence, uncontrolled hunting, increased deforestation, a decline in prey species, and the poisoning of tigers in retaliation for livestock killing continued to threaten the tiger population (Khandelwal, 2005). The tiger population in 1972 was estimated to be less than 1,800, which gradually declined from about 40,000 in the early 1900s (Smith et al., 1998; Sharma et al., 2014). After Indian independence, in 1973, modern India’s conservation drive officially recognized the tiger as the National Animal of India, to not only protect the dwindling tiger population but also symbolize young India with the representational qualities of a tiger – power, pride, and majesty (Aiyadurai, 2016).

In 1969, the 10th General Assembly of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) held in India focused on addressing the precarious condition of tigers across Asia. In response, the Indian Board for Wildlife took a step ahead and imposed a national ban on tiger hunting that put Indian tigers on the “endangered list” (Subramanyam and Sreemadhavan, 1969; Rangarajan, 2005). This initiative triggered the Indian government to launch Project Tiger, in 1973, one of the world’s largest wildlife conservation projects to protect and conserve the depleting population of the Royal Bengal Tiger (Rangarajan, 2005; Damodaran, 2007). Within the scope of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 of India, Project Tiger’s main activities included tiger habitat amelioration, day-to-day monitoring of tiger numbers, eco-development for local people in buffer areas, voluntary relocation of people from the core or critical tiger habitats, and addressing human-wildlife conflicts (GOI, 2005, 93). During the formative stages of the project, nine tiger reserves (Bandipur, Corbett, Kanha, Manas, Melghat, Palamau, Ranthambore, Similipal, and Sunderbans) were created, and by 2018 their number increased to 50, covering an area of 2.21% of the country (Khandelwal, 2005; National Tiger Conservation Authority/Project Tiger, 2018a). According to the National Tiger Conservation Authority/Project Tiger (2018a), India has the world’s largest tiger population of 2,967, which is more than 80% of the global population (3,159) of adult free-ranging tigers.

Tiger conservation has always been contested with tribal cultural and livelihood conservation. Conservation initiatives usually conflict with forest-dependent tribal livelihood (Mahapatra et al., 2015). Although both tigers and tribal peoples have weaved their lives around the forest for millennia, tribal groups have frequently faced eviction rather than policies that fostered strategic co-existence. Tiger conservation comes at the cost of eviction of tribal communities who not only face loss of land, threats to cultural practices, and insecurity due to uncertain future but also experience the physical and psychological trauma of adjusting to new locations (Torri, 2011). These factors contribute to a broader loss of identity and indigenous habits, similar to Liisa Malkki’s (1995) observation of identity loss that results from global refugee crises. Indeed, despite becoming “conservation refugees,” these tribal groups are often deemed “enemies of conservation” (Dowie, 2011). Thus, this case study begins with tiger conservation and moves toward tribal development to probe how the Chenchu people of the Nalamalla forest understand and situate themselves in relation to the process of displacement.

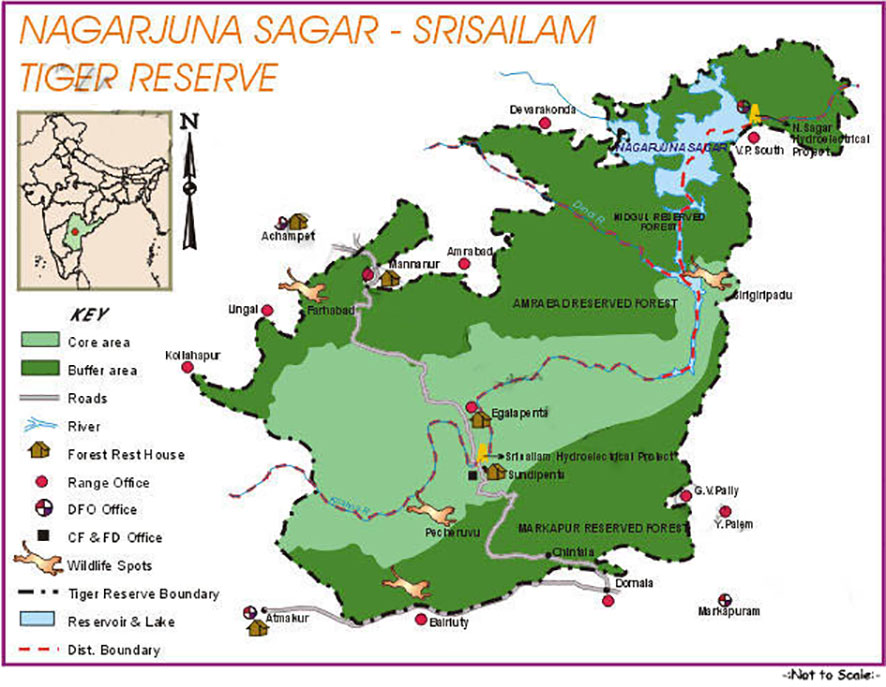

In 1978, an area of 4,347 km2 (2,701 mi2) of the Nallamala forest in Andhra Pradesh in southern India was declared a protected area. It was named the Nagarjunasagar-Srisailam Tiger Reserve (NSTR) (Figure 1), which later became a Project Tiger site in 1983 (Sudeesh and Reddy, 2013). The Nallamala forest was not only a biodiversity hub, but also “home” to the Chenchu people, traditionally a forager community (Ivanov, 2014). The establishment of the NSTR imposed a total ban on logging, collection of forest products, hunting, or any human habitation within the tiger reserve. An immediate repercussion of the Reserve’s establishment was the gradual removal of the Chenchu people from the forest to the town fringes (Narayan, 2014). The Chenchu displacement served dual objectives of the Indian government – protect the tigers of Nallamala and provide “better” living conditions to the Chenchu communities in the displaced locations.

Figure 1 Map of Nagarjunasagar-Srisailam Tiger Reserve Source: Ministry of Environment and Forests, India (http://projecttiger.nic.in/printableguide_Nagarjunsagar.htm).

The Indian government has invested immensely in developing the socio-economic conditions of the Chenchu as well as conserving their culture, values, traditional ecological knowledge, and folklore in the Nallamala region (Ministry of Tribal Affairs, 2015). For instance, for 2018-19, the proposed budget for tribal development in Andhra Pradesh, including the Chenchu, was approximately 207 billion Indian Rupees (~2.5 billion USD in 2022 conversion rate) (AP Tribal Welfare Department, 2018–19a). Despite these efforts, development projects have been critiqued for their tepid outcome, leading to unrest among the Chenchu people (Sen and Lalhrietpui, 2006; Narayan, 2014; Ratnam et al., 2014). This tension prompts a question – what is going wrong? An analysis of whether the government’s objectives for implementing its development projects match the Chenchu people’s expectations becomes imperative, and this research aims to unpack those narratives.

This paper presents the similarities and discrepancies between the definitions of development of the Chenchu and Government representatives. However, only eliciting these comparisons may leave many questions unresolved, such as: why do Government representatives define development the way they do? Are there any challenges to the implementation as well as access to development? What are the success stories in this development scenario? To answer these questions, it was essential to learn the Chenchu and Government representative’s ideas of development, the Chenchu’s challenges to access “development” and their rationale for appreciating some of the development projects, and the Government representatives’ thoughts on the limitations to Chenchu development. The paper also presents views on forest conservation and displacement of both the Chenchu and Government representatives. Our results present the tribe’s dependence on and affiliation with the forest, views on tiger protection, and debates of displacement from both sides, thus conveying development, conservation, and displacement priorities. Broadly, by presenting these findings, the paper attempts to spur new ways of encountering conservation, displacement, and development issues in academics and policymakers.

According to the 2010 tiger population assessment by the Government of India, the NSTR is one of the biggest tiger reserves in India, covering about 4,347 km2 (2,701 mi2) of the Nallamala forest, with an estimated tiger population of 53-67 in 2018 (National Tiger Conservation Authority/Project Tiger, 2018b). The Nallamala has been a source of livelihood for the Chenchu, who have built their lives, cultural practices, spiritual beliefs, and affiliation with nature through the forest. The innate bonding between the Chenchu and the forest is evident in some of the earliest and recent Indian literature. The Manu Smriti (600-200 BCE, Chapter 24), one of the earliest texts of Indian literature, mentions the Chenchu as the first dwellers of the Andhra Pradesh region, and the word “Chenchu” is derived from chettu, a tree in the Telugu language, to mean “a person who lives under a tree” (Ratha, 1997; Lee et al., 1999; Freitas, 2006; Jois, 2015). von Fürer-Haimendorf (1982), one of the earliest ethnographers on the Chenchu tribe, describes the Chenchu as a nomadic group living in the Nallamala jungles with foraging as their main occupation. He narrates how the Chenchu did not feel bound to a particular locality and sported a strong sense of personal freedom and spirit. They were also excellent hunters and could predict an animal’s next moves just by observing its movement and behavior. He recognized gender equality and an egalitarian livelihood as predominant attributes of the Chenchu at that time.

Studies indicate that the Chenchu have a good knowledge of the forest and the protection of its forest resources; for example, they do not kill pregnant animals, they leave portions of the roots and tubers that they consume for their regeneration, and they collect only the fully grown bamboo sticks and ensure that the ripened seeds fall on the ground for germination (Rao and Ramana, 2007; Rao et al., 2007; Reddy, 2014). With foraging as a major livelihood source for the Chenchu tribe, they have not only developed a symbiotic relationship with the forest but also a complex co-existence with the tigers. Although they face livestock losses due to attacks by tigers and leopards, they exhibit a deeper ecological and traditional knowledge of the big cats and their movement, which reinforces a sense of belonging to the tigers and the forest (Lozano et al., 2019). This intense regard for the forest and tigers has shaped the Chenchu identities as an integral part of the forest.

During colonial rule in India, the land rights of tribal groups were restricted, and the forest resources were controlled by the British, who essentially diverted forest revenue to fund colonial military, industrial, and commercial sectors (Kapoor, 2009). Such restrictions on tribal rights led to uprisings or revolts by forest-dependent tribal people (Mahapatra, 2002). Later, the Indian Forest Act of 1927 provided some privileges to the tribal people to collect firewood, timbers for household construction, and forest products for handicrafts, quarry stone, hunting, and fishing, and also petty jobs at the Forest Department (Mahapatra, 2002). In 1975, the Indian government recognized the Chenchu tribe as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG) due to its low economic and literacy levels and isolated living in the forest (Thamminaina, 2018).

In recent times, some of the Chenchu tribes have been slowly migrating to the nearby towns due to deforestation, depleting forest resources, exogamy, and Naxal insurgencies (the conflicts between the Maoist groups and the Indian government) (Thamminaina, 2015). In the late 1990s, the state of Andhra Pradesh experienced a surge in Naxal activities where the radical communist groups fought for tribal land rights against the State’s control over the forest lands (Goswami, 2013). The Nallamala forest was a hideout for these groups during those times (Reddy and Kumar, 2010; Singhal and Nilakantan, 2012). Because there were violent encounters between the Naxalites and the police department in the Nallamala region, the Chenchu were encouraged by the Indian government to relocate to safer places away from the forest (National Tiger Conservation Authority/Project Tiger, 2006; Kannabiran et al., 2010). However, the threat of Naxal resistance is not the sole reason for the Chenchu removal. The dual goals of development and conservation – Indian government’s goal to improve the social and economic conditions of PVTGs and the creation of the NSTR that occupied a large portion of the Nallamala forest as well as regarded any anthropogenic activities in the core tiger habitat as a potential threat to biodiversity conservation – were pertinent for the Chenchu relocation.

The displacement of the Chenchu groups, which was initially a gradual process, had now gained momentum with the establishment of the NSTR. The National Advisory Council, an advisory body to the Prime Minister of India that acts as a bridge between the Indian civil society and the Government, recommended that the Indian Government pay attention to the displaced Chenchu tribes in terms of socio-economic development provisions, as compensation for displacement (“National Advisory Council”, n.d., 6). In 2008, the Indian government designed the Conservation-cum-Development Plan (CCDP) to provide comprehensive socio-economic development to the PVTGs. Ministry of Tribal Affairs, 2015 issued operational guidelines to implement the CCDP to various Tribal Welfare Departments within the individual state governments of India. The main agenda of the CCDP was to conserve the PVTG’s cultures, document their lifestyles, traditional medicines and medical practices, folklore, sports, music, dance, crops, and foods (Ministry of Tribal Affairs (2015)). The scheme also emphasized the provision of livelihood, employment, and educational opportunities, land distribution and development facilities, and culture and urban development to the PVTGs. The Chenchu people also became the direct beneficiaries of the CCDP’s provisions.

One of the main goals of the fifth Five Year Plan (1974-79) of India was “Hill and Tribal Areas, Backward Classes Social Welfare and Rehabilitation” (Planning Commission, 1976, p. 84), which led to the creation of Integrated Tribal Development Agencies (ITDAs) by the Indian government to administer developmental activities toward the PVTGs in each state. The state of Andhra Pradesh, in 1975, was the first to adopt ITDAs for tribal development (Jammu and Chalam, 2019). The ITDAs implemented developmental projects designed by both the State Government and Central Government toward the PVTGs and administered their progress. Sometimes, local NGOs also collaborated with the ITDA in funding and implementing projects. The ITDA’s development projects are designed to provide economic support, health and education benefits, agricultural guidance and subsidies, and employment opportunities to the tribal people including the Chenchu (Donthi, 2014).

Although the Indian Government has been investing large amounts of money in tribal welfare and development for Andhra Pradesh (AP Tribal Welfare Department, 2018-19) to alleviate poverty rates and bring socio-economic development to the Chenchu communities, several studies have indicated an “imbalance” or mismatch between the Chenchu people’s expectation from development projects and the Indian government’s development provisions toward the Chenchu development (Sen and Lalhrietpui, 2006; Narayan, 2014; Ratnam et al., 2014; Thamminaina, 2015). Sen and Lalhrietpui (2006) discuss the Chenchu dissatisfaction toward NSTR conservation goals citing, “one Chenchu hunter-gatherer who was displaced by a tiger reserve reacted to displacement by stating, ‘If you love tigers so much, why don’t you shift all of them to Hyderabad and declare the city a tiger reserve?’” (p. 4206). Ratnam et al. (2014) highlight that the Chenchu faced unemployment due to the lack of the required vocational skills, a slow adaptation to the relocated places and the people and cultures, and a hindering resistance to new changes in livelihood conditions. Further, Apparao Thamminaina (2015) argues that the relocation from the natural environs within the reserve has resulted in negative consequences for the community: the Chenchu people who were once the masters of their work have become “servants” to others due to their dependency for work. Meenakshi Narayan (2014) argues that although the Chenchu people feel more secure by moving from foraging in the forest to a settled agricultural life in the villages, they still describe their life in the relocated places as one of poverty and unhappiness.

This research uses a bottom-up approach to learn the Chenchu’s perceptions on development, protection of nature and tigers, and their tensions and compromises with displacement. When the historical, Western connotation of nature as savage, barren, and wasteful was gradually replaced by the idea of nature as a “pristine” space, biodiversity conservation took precedence over unrestricted use of resources (Cronon, 1996). For conservation to thrive, regulating and controlling the “commons” became an “ethical necessity” for the governing bodies to maintain a sustainable species and natural resource preservation, evoking global theories and critiques on biodiversity conservation (Igoe, 2004; Agrawal and Redford, 2009). The creation of the NSTR echoes these Western ideologies where the Bengal tigers were protected because they were endangered. The biodiversity of Nallamala was conserved because of the threat of the “tragedy of the commons” (Cronon, 1996). For the Chenchu, the predicament of displacement has created various ways of connecting or reconnecting with the forest. Some of them are employed as anti-poaching squads, ecotourism guides, forest guards, and tiger trackers by the NSTR conservation authorities (Sen and Lalhrietpui, 2006). This research employs the theoretical frameworks of “environmentality” and “environmental subjects” to examine how the Chenchu-forest connection can be further understood through those anthropological concepts (Agrawal, 2005).

Biodiversity conservation discussions would be incomplete if conservation viewpoints of the non-West, or the global South, are not included. While Western conservation paradigms create protected areas that separate human beings from nature, ethnographers working with indigenous groups argue that non-Western, indigenous, ways of protecting nature emphasize human-nature relationships where conservation is a natural, not so overt, and a routine activity that includes environmental knowledge and the management of natural resources and their sustainable use (Posey, 1985; Tuck-Po, 2004; West, 2005; Dove, 2006). Igoe (2004) argues that many indigenous communities in the global South believe in simply maintaining the traditional ways of managing resources and ensuring their availability to the next generation. These global perspectives help in informing the Chenchu views on the NSTR and tigers.

The idea of “governmentality” by Michel Foucault (1991) where the population that is governed by State processes, such as institutions and agencies, discourses, norms, and self-regulation, is also relevant to understanding the modes and methods of governing by the State (Gupta, 2001). The Chenchu, who are displaced owing to both conservation and development initiatives of the Indian Government, are also the beneficiaries of development (Sahani and Nandy, 2013). In the development context of postcolonial India, Akhil Gupta opines that underdevelopment is a form of postcolonial identity (Gupta, 1998 in Pandian, 2008) and links the development of agriculture as a critical aspect for the development of modern India (Gupta, 1997). Anand Pandian (2008) considers the rural citizens of India as “subjects of development” – “individuals who must submit themselves to an order of power that identifies their own nature as a problem and demands that they work to develop themselves in order to overcome the limits of this nature.” The research intends to find how the Chenchu people’s definition of development aligns with this alternative conceptualization, and further how this aligns (or not) with the Government representatives’ understandings of development.

Before delving into the specifics of data collection and analysis methods, it is important to describe the first author’s positionality and recognition of any stereotyping during the research. The first author’s identity as an Indian national with fluency in the language of her participants, Telugu, was an advantage to better connect with her participants and relate to their issues. For her positionality as an insider, it was easier to recognize the social structure, culture, gender dynamics, norms, and customs of the people. From an etic or outsider perspective (Morris et al., 1999), the researcher could link some of the cultural and ecological practices of the Chenchu people to the global narratives of ecology and conservation.

The fieldwork for this study was conducted for 30 days from June to July 2019 in the Srisailam-Nallamala forest region of Andhra Pradesh state in India. The ethnographic methods included participant observation and semi-structured interviews. A total of 28 participants, with 7 female and 21 male respondents with an average age of all the participants being 46.7 years, were contacted. Upon obtaining oral consent, the interviews were audio-recorded. Interviewees were purposively sampled to build a comparison between two perspectives: (i) Chenchu participants (n=15) and (ii) State Government representatives (n=13), including the ITDA authorities, the NSTR conservation officers, and the local NGO workers, for their collaboration with the Government in development projects.

As displacement was an ongoing process and perspectives on development could be influenced by the interlocutor’s location in this process, the Chenchu interlocutors were further divided into three subgroups based on their locations and different stages of displacement. Those living in the interior parts of the Nallamala forest we refer to as the “Deep Forest Chenchu” (n=4); those residing in areas between the forest and the nearby towns as the “Intermediate Forest Chenchu” (n=5); and those in resettled locations and completely displaced as the “Displaced Chenchu” (n=6). Purposively selecting Chenchu participants based on their location, or distance from the forest or the nearby towns, intended to bring more diversity in terms of their attachment to the forest or development perspectives based on their access to basic amenities. In a similar fashion, the Government and NGO workers were purposively sampled to provide a good cross-section of perspectives regarding development and conservation responsibilities. Interviews conducted with Government representatives and NGO workers (n=13) were further grouped into three samples: (i) NSTR conservation authorities (n=3), (ii) ITDA representatives (n=5), and (iii) NGO workers (n=5).

The following map (Figure 2) shows the locations of the field sites of the Chenchu habitations and the offices of the Government representatives in the Nallamala-Srisailam region. On the map, the interior habitations of the Deep Forest Chenchu are marked in green, the locations of the Intermediate Forest Chenchu are shown in blue, the settlements of the Displaced Chenchu are in orange, and the locations of the Government offices are tagged in brown.

Figure 2 Location of research field sites. (a) Green: Deep Forest Chenchu settlements; (b) Blue: Intermediate Forest Chenchu locations; (c) Orange: Displaced Chenchu habitations; (d) Brown: Government and NGO office locations. Source: https://www.google.com/earth/.

Three methods were used to identify and contact the research participants: (i) snowball sampling method (Bernard, 2017), (ii) introduction as an independent researcher to Chenchu communities via local NGO worker networks, and (iii) through the main author’s personal connections from her time as an intern for the ITDA during June-July 2018. Once potential participants were identified, the main author engaged in rapport-building activities such as attending informal meetings, participating in personal discussions, and using traditional ethnographic methods of participant observation to lessen the “insider-outsider” complex (Chavez, 2008). Everyday life topics were discussed in the local language in a public setting. This allowed the elders in the community to reminisce about their way of life in the forest as children, their affiliation to the forest, what they ate, and how they viewed the world outside the forest. The youngsters, above 18 years, were eager to discuss their life in the communities, their education, and job opportunities.

For qualitative data collection, two different question guides, which included open-ended and closed-ended structured and semi-structured interview questions, were used – one for the Chenchu tribal groups and another for the Government & NGO representatives. The questions were set in both English and Telugu languages. The research instrument was designed to answer the primary question, which was Does the displaced Chenchu people’s definition of ‘development’ match the Government’s idea of ‘development?’ This question was split into two secondary questions – one for the Chenchu people and another for the Government representatives. The questions for the Chenchu people were aimed at eliciting data to answer the secondary question, S1: What terminology do the Chenchu people use to indicate their socio-economic “development?” The probable themes for the questions in the guide were broadly based on the Chenchu people’s:

● Knowledge of socioeconomic development indicators

● Views on biodiversity conservation and displacement

● Perspectives on the development projects of the State Government and the effectiveness of these projects

Similarly, the question guide for the Government representatives was designed to elicit data for the secondary question, S2: What is the State Government’s logic behind implementing its development projects? The potential themes for the questions in the guide were broadly based on the Government representatives’:

● Knowledge of socioeconomic development indicators

● Views on biodiversity conservation and displacement

● Knowledge of the development projects and their rationale for investing, implementing, prioritizing these projects, and facilitating Chenchu people’s displacement and development

These question guides for both Government representatives and Chenchu people were designed on the same pattern consisting of common and specific questions.1 Common questions found in both interview guides helped in eliciting data that could be comparatively analyzed to answer the primary research question. Questions exclusive to the group interviewed were designed to elicit that group’s particular understandings, interests, and desires.

All 28 interview audio recordings, mostly in the Telugu language, were transcribed into English. QDA Miner (QDA Miner, Provalis Research, Montreal, Canada), a qualitative data analysis software package, was used to code and qualitatively analyze the transcribed interviews. A grounded theory approach, based on inductive or “open” coding, was used to allow predominant themes and patterns to emerge from the collected data (Bernard, 2017). Both in vivo coding, themes named after the actual phrases used by the participants (Strauss and Corbin, 1990), and values coding, themes named after the observed values, beliefs, and attitudes of the participants (Saldanãa, 2015), were used to name the emerging themes. During coding, an emerging thought was given a code name while reading through the transcription. Thoughts that were relevant to the research questions were also identified and coded to group under a common category. For example, a participant’s response “Giving loans for livelihood so that our problems are solved” was given a code name “Loans, business, agriculture” and categorized under the “Development definition” category since the response was to a question on how the participant conceptualized development. In this way, codes were generated and grouped under a suitable category and many categories were produced containing one or more codes. The codebook analysis was retrieved from the QDA Miner software and the number of the “Counts,” indicating the number of times a particular thought or idea was expressed, and the number of the “Cases,” indicating the number of people expressing that thought or idea, was used to analyze how various groups and subgroups felt about their issues. A similar analysis was conducted for all the groups.

First, the development definitions of the Chenchu people were gathered and analyzed to answer the research’s secondary question S1 – What terminology do the Chenchu people use to indicate their socio-economic “development”? and then, the development objectives and perceptions of the Government & NGO representatives were collated and analyzed to answer S2 – What is the State Government’s logic behind implementing its development projects? Finally, these definitions were compared for similarities and differences to answer the research’s primary question “Does development mean the same to both the internally displaced Chenchu people and the Government?

This section presents a detailed comparison of the development perspectives of the Chenchu and the Government representatives, particularly, the different levels of agreement between the two groups based primarily on the frequencies of concepts found within the qualitative analysis described above. The results presented in this section unpack the underlying factors for the following: the government’s development priorities, the Chenchu people’s challenges to access development, the development projects appreciated by the Chenchu, and the Government’s views on some of the barriers to Chenchu development. Also, as the Nalamalla forest is a vital aspect of Chenchu lives, the results of the Chenchu and the Government’s views on conservation and displacement give a comprehensive picture of their attachment to the forest, regard for the tigers, and standpoints on displacement.

One of the outcomes of the data analysis indicated that both the Chenchu and the Government & NGO groups shared some common perspectives on development. The following analysis discusses the results of qualitative analysis of the frequency of coded concepts within participants’ responses across various subgroups. These frequencies enable comparison based on the percentage of participants who shared a particular idea both across the entire sample and within various subgroupings. The ensuing analysis is also interspersed with direct quotations from interviews to further illustrate and help in representing the meaning of the concepts held by a participant as well as a group.

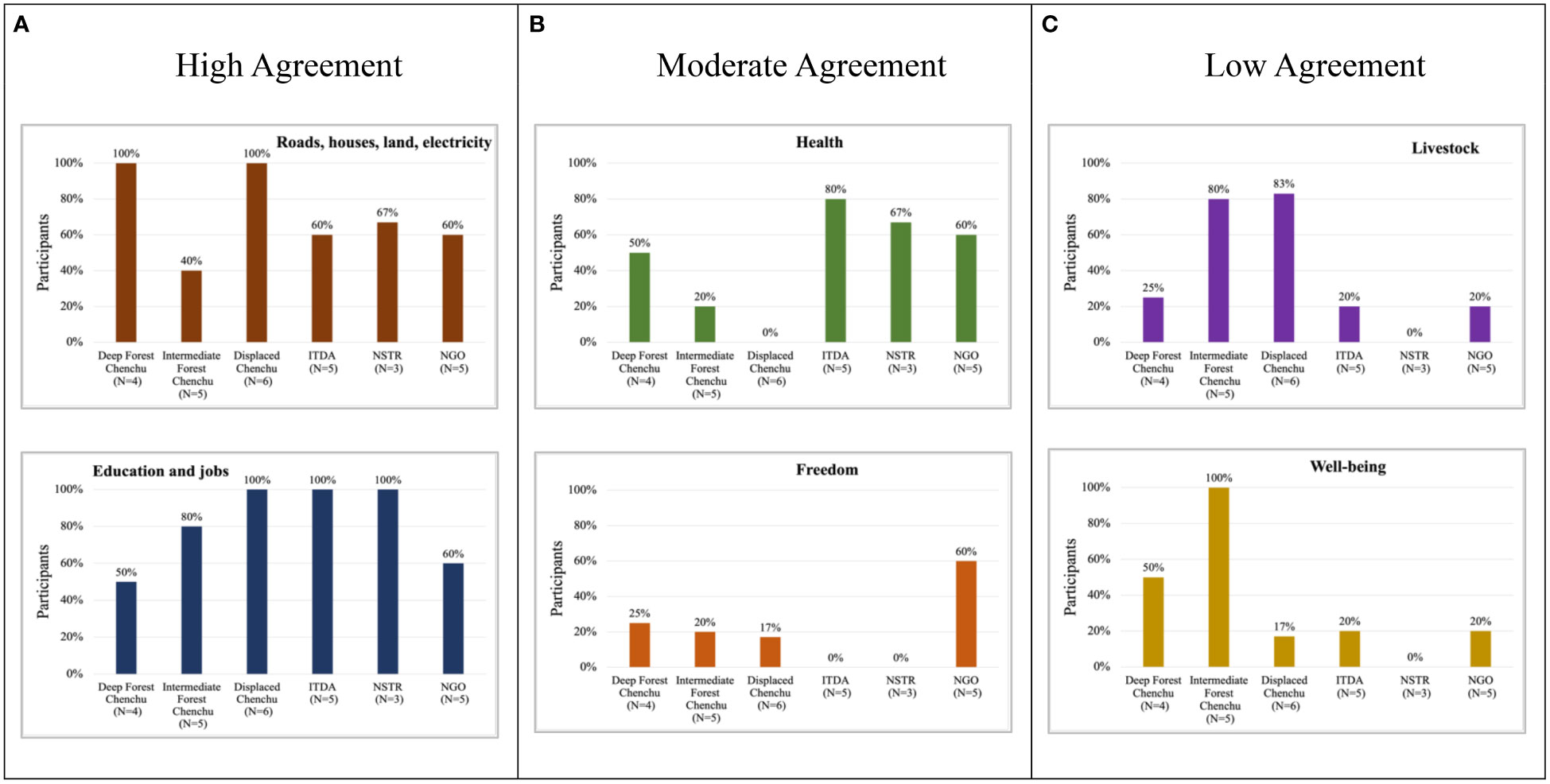

The definitions of development that were common to both the Chenchu and the Government & NGO representatives included: “Roads, houses, land, electricity,” “Livestock,” “Education and jobs,” “Health,” “Freedom,” and “Well-being.” The responses of the participants belonging to each aforementioned subgroup can be found in Figure 3.

Although there is some agreement across the entire sample (Chenchu and Government & NGO groups), subgroup analysis (Deep Forest Chenchu, Intermediate Forest Chenchu, Displaced Chenchu, ITDA, NSTR, and NGO) shows that there is variation within these larger groupings. There are visible variations where one subgroup does not express an idea as “development” at all. For example, “Health” is not a development definition for the Displaced Chenchu, and “Freedom” is not a development indicator for the ITDA and NSTR groups. In other cases, there is a moderate agreement between the subgroups. For example, “Health” was emphasized by the Government group and less by the Chenchu group. Similarly, “Freedom,” is espoused both by the Chenchu and NGO groups. Meanwhile “Livestock” and “Well-being” demonstrate important disagreement across the subgroups. These categories were highlighted by the Chenchu subgroups but rarely brought up by the Government & NGO subgroups. The variations in agreement found across groups are visually represented in Figure 4. Thresholds for determining levels were developed by the authors while analyzing the resultant graphs. For example, the development definitions that received more than 40 percent of the responses from all six subgroups were considered as “high agreement”; those that received at least 25-30 percent of the responses from at least four groups were categorized as “moderate agreement”; and those definitions that received no or less than 25-30 percent of the responses from the groups were labeled as “low agreement.”

Figure 4 Common definitions of “development” in varying agreements between the Chenchu people and the Government & NGO representatives. (A) High agreement – “Roads, houses, land, and electricity” and “Education and jobs”; (B) Moderate agreement – “Health” and “Freedom”; (C) Low agreement – “Livestock” and “Well-being.”

A “high agreement” indicates that most of the participants from both groups agreed that some development provisions were indicators of development. These results not only highlight the participants’ recognition of development but also convey their priorities. Figure 4A shows that more participants from five subgroups, except Intermediate Forest Chenchu, believe that roads, houses, land, and electricity are indeed significant markers of development. Similarly, education and jobs were considered essential tools of development by more than half of the participants in all groups. Subgroup-wise, all the participants in the Displaced Chenchu, ITDA, and NSTR groups agree that education and jobs characterize development, while there is a declining curve of the importance of education and jobs from the Intermediate Forest Chenchu to the Deep Forest Chenchu people. We can also get an idea of how the location of a person can be an indicator of his or her needs. Since the Displaced Chenchu and the Intermediate Forest Chenchu people are closer to the towns, they experience education and jobs as a necessity, while only half of the Deep Forest Chenchu participants expressed such a need. To substantiate, an Intermediate Forest Chenchu participant expressed the importance of education and jobs as:

A job is very important. For example, if a man has completed his degree-level studies, he gets the job. He is respected because he has a job. Isn’t it all because of education? – Male, 35-40 years, Intermediate Forest Chenchu

When asked “On what basis do you prioritize the solving of the problems of the Chenchu people?” an ITDA representative said that “education takes the first priority and then comes everything else.”

Health was given the highest priority by the ITDA representatives, NGO workers, and the Deep Forest Chenchu participants (Figure 4B). Per fieldnotes, the Chenchu participants defined good health by using the terms “health,” “medical facilities,” “being energetic,” and “free of diseases.” However, the Government & NGO groups mostly used the terms “medical facilities,” “access to health,” “medical camps,” “Anganwadi [Government’s public health center],” and “community health centers” to define health. Again, since the Displaced Chenchu and the Intermediate Forest Chenchu were closer to the towns and were able to access hospitals and medical facilities, it can be implied that healthcare was not really prioritized in comparison with the Deep Forest Chenchu who had almost no access to healthcare facilities owing to their location. This view was substantiated by a Deep Forest respondent as:

Imagine a man is taught driving and a car is given to him. The car can be used to lead his livelihood and also to take our patients to the hospitals. The family will develop. Isn’t that development? – Male, 30-35 years, Deep Forest Chenchu

Studies (von Fürer-Haimendorf, 1982) have identified the Chenchu as free spirit, nomadic tribes, who do not feel bound to a specific place. This research elicits those observations where the Chenchu participants moderately agreed that freedom was a way of defining development. Freedom was addressed as a definition of development in all the Chenchu groups by using the terms “independence,” “self-dependence,” and “freedom.” In the Government & NGO group, most of the NGO workers agreed that freedom, in terms of “self-reliance,” brings development.

Although the concepts discussed above demonstrate some agreement over conceptualizations of development, our results show that the overall agreement of the participants about many other definitions was quite low. What was a priority for one group was not really the same for the other. The data presented in this section indicate development definitions that have low agreements between the groups and any imbalance in perceptions and priorities between the two groups. Livestock (cows, goats, oxen, chicken, and buffaloes) was an important requirement for many of the Chenchu people to sustain themselves and their livelihoods, but this varied considerably depending on their location and/or identity. Participants in both the Intermediate Forest Chenchu and the Displaced Chenchu subgroups considered owning livestock as an important development definition compared to the views of those in the Deep Forest Chenchu, ITDA, and NGO groups. Participant observation and interviews revealed that the Intermediate Forest Chenchu and Displaced Chenchu people needed cattle for income-generating activities and subsistence living; whereas, for the Deep Forest Chenchu, although cattle were a necessity for dairy products, there was also the threat of attack from wild animals on cattle and human beings, leading to loss of lives, in the deep forest.

Another area of low agreement was in “well-being.” The Government & NGO groups’ conceptualization of “well-being” included ideas such as hygiene and sanitation, being hygienic, good life, wearing clean clothes, brushing hair, and brushing teeth. In contrast, the Chenchu conceptualizations included ideas such as living together and happily, everybody must talk to each other, houses must be clean, children must listen to us, husband and wife should be happy, there should be a goat in front of the house, the men should have a job to do, and respect. While all the participants in the Intermediate Forest Chenchu group regarded “well-being” as an indicator of development, only one participant in the Displaced Chenchu, ITDA, and NGO groups concurred. The following quotes indicate the participant’s narrative of well-being. They help in understanding how well-being can be situated in the development context.

Living together and happily is improvement of living conditions. – Male, 35-40 years, Deep Forest Chenchu

Well-being is development. Husband and wife should be happy, there should be a goat in front of the house, the men should have a job to do. – Female, 30-35 years, Forest produce collector, Deep Forest Chenchu

But, we have to develop everything beginning with culture. We include hygiene and sanitation. – Male, 55-60 years, ITDA official

While the Intermediate Forest Chenchu group believes well-being is an indicator of development, the rest of the groups moderately emphasize it (Figure 4C).

This section presents the common development definitions of both groups and their levels of agreement, the analysis also presents a spectrum of development concepts – from the most common narratives such as houses, roads, land, electricity, education, jobs, and health to some of the niche ideas such as well-being, freedom, and livestock. By presenting the results on how much each group agrees with a concept as development with other groups, a further study on the reasons for such an agreement, particularly from the perspective of their location or job responsibility, can be pursued.

To learn some of the underlying causes for any mismatches or disagreements in the conceptualization of “development” between the Chenchu and the Government & NGO groups, it was essential to learn the trajectory of the Chenchu development plans and the development priorities of the Government representatives, who are the main “providers” of Chenchu development. These views were elicited from the overall responses to the interview question: “On what basis do you prioritize the solving of the problems of the Chenchu people?” The occurrence of a particular code in the transcription is tagged as a response. Figure 5 shows the percentage of responses for each of the development priority categories developed by coding the interviews.

As seen in the figure, the Government & NGO informants placed more emphasis on improving the conditions of medical facilities and education for the Chenchu people. They responded least to providing basic amenities or Chenchu participation in development and sustainable agriculture.

As mentioned earlier, despite many development initiatives by the Government, the Chenchu communities faced challenges to access development. One of the goals of this study was to better understand the sources of Chenchu’s discontent with development agents. The frequency in which various problems were discussed by the Chenchu interlocutors in relationship to the Government’s projects, their implementation, and the people’s opinion on the Government & NGO are presented in Figure 6.

As seen in the table, the greatest grievances of the Chenchu people were “Government doesn’t care” about them and “no access to development.” Poor government facilities and paperwork were also recorded as some of the problems faced by the Chenchu. Although corruption in Government departments and lack of trust in the Government’s development works were recorded a smaller number of times, it must not be considered that they do not exist or are insignificant as they can play a larger role in limiting the Chenchu people’s access to development.

One of the Displaced Chenchu participants discusses the existing scenario of lack of support from the Government:

We were somewhere 60-30 kilometers deep in the forest, they brought us here, changed our way of living, and when we were ready to accept and look forward to living this way, suddenly if they [Government] don’t support us, what to do? – Male, 25-30 years, Displaced Chenchu

Apart from comparing development definitions, one of the pressing questions of this study was “What is going wrong?” about the development scenario. Acknowledging that the Indian government has been spending enormous amounts of money on Chenchu development, the above analysis provides some insights into the actual barriers for the Chenchu to access development. These results not only help in learning the roadblocks to development but also act as a reference point for any policy formulations.

The study also examined what factors the Chenchu people appreciate in the Government projects. They rated some of the projects as being beneficial to improving their livelihood. Just over half of the Deep Forest Chenchu respondents mentioned that the Government and NGOs had provided them with livestock, solar lamps, and borewells for water. More than half of the Intermediate Forest Chenchu participants opined that the Government and NGOs had helped them in addressing their grievances, spreading awareness on making positive changes to existing living conditions for better progress, and developing skills that can be used for finding jobs or higher education. Most of the Displaced Chenchu interlocutors reported that they were aware of the Government and NGO’s provisions for education, agricultural lands, electricity, health, and free meals for school children in Government-run schools. The following direct quotes indicate the various ways the Chenchu appreciated Government projects:

Earlier, it was difficult. We had no access to hospitals. We had to take pregnant women in a jola [makeshift carrier]. Now, we are doing okay by the government. – Male, 43-47 years, Displaced Chenchu

Because of Indira Gandhi [former Prime Minister of India], compared to our past, we were given rights, loans, schools, houses, and land. We realized that we too have rights. It is somewhat good between the government and the people. – Female, 53-57 years, Intermediate Forest Chenchu

From these, it can be concluded that while there are some problems with the Government projects, the Chenchu have also recognized and appreciated the Government’s work in developing them.

During the interviews, many Government and NGO workers discussed the challenges faced by the Chenchu in accessing development. The biggest limitation cited by them was that the Chenchu do not mingle with the “mainstream” society (Figure 7). Despite being development authorities, they acknowledged that the inadequacy of development projects, poor government facilities, and repetition in development works as one of the drawbacks to Chenchu development.

Eliciting the dynamics of the Chenchu-Government relationship, a Displaced Chenchu participant said, “The government is doing good. It is providing mid-day meals in schools for our children” but later in the interview, he also said, “But we don’t get any jobs for our gudem [settlement/habitation] people. Nobody cares.” When asked whether displacement from the forest has helped the Chenchu, the participant appreciated the Government projects for providing houses and helping them. Yet, when it comes to providing jobs, he opined that the Government has been negligent, leading the Chenchu participant to think that the Government does not care for them. Here, the fulfillment of the Chenchu’s needs is one of the bases for evaluating the Government’s development work. Therefore, it can be implied that the Chenchu’s perspective of the Government is based on their experience and informed decisions.

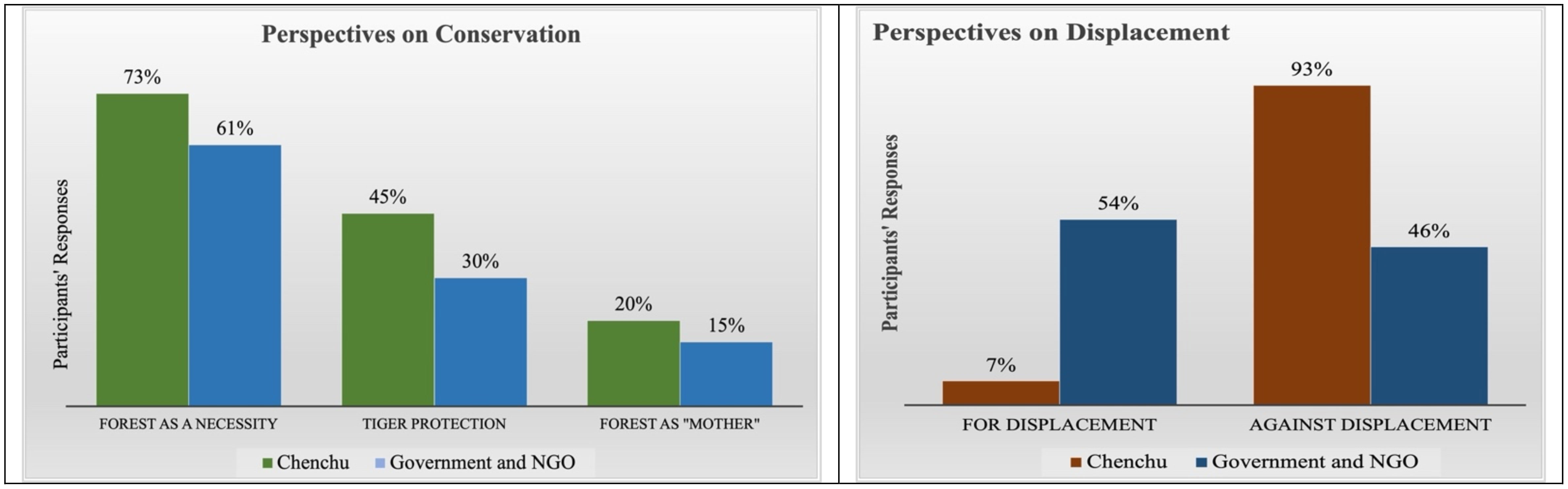

Since the Nallamala forest is an important part of both the Chenchu lives and the Government that protects the forest, learning whether the people and the Government shared the same attitudes or how much did they agree with each other on forest conservation and the displacement initiatives was necessary. These views are summarized in Figure 8.

Figure 8 Perspectives of both Chenchu people and Government & NGO representatives on conservation and displacement.

In the context of development, the sources of livelihood play an important role in conveying the sustainability of living. For the Chenchu, the forest is an integral part of their lives, both for livelihood and their affiliation with the forest. From the analysis, most of the Chenchu people believed that the forest was a necessity not only for their livelihoods and sustenance but also for the “kind of feeling” it gives them, which reinstates their autochthony to the forest despite displacement from the forest. The following quotes illustrate the Chenchu people’s attachment and dependency on the Nallamala forest:

Of course, we are dependent on the forest. We are there by the forest. Because the government isn’t doing anything, we are dependent on the forest. For example, there are jaanakai [a type of berries], we need them because it’s our food. We need all the fruits of the forest. – Male, 30-35 years, Deep Forest Chenchu

The tigers roam around! Tigers, bears, and other animals co-exist with us. We are together. Isn’t it because of our ancestors that the forest is alive? – Female, 55-60 years, Intermediate Forest Chenchu

More than half of the Government & NGO group opined that the forest is a necessity for the Chenchu and also for the biodiversity conservation practices of the Government. For example, one interlocutor said:

Not only forest products, both flora and fauna, both living and non-living. Their [the Chenchu] main occupation is hunting. They eat meat, prepare intoxicating drinks out of mahua trees. They eat tubers and honey too. They depend on those things for consumption and livelihood. – Male, 40-45 years, NSTR

As mentioned earlier, the Nallamala forest is home to both the Chenchu and the tigers. Although tigers are considered wild, the Chenchu people have a special regard for the tigers. One of the reasons for this regard could be the Chenchu people’s prolonged co-existence with the tigers and the wildlife of the Nallamala forest. The following narratives illustrate some of the attitudes of Chenchu people and Government & NGO group toward tiger protection as conservation:

But we have a relationship with the tigers. Because we roam around in the forest, we can tell where the tiger is. If we move to the town, how will you know where the tigers are? If around, it signals us that it’s there. It says, “Ahhhmmmm,” and we’ll know. That’s an indication that we must go away. We are scared too. The bears are more dangerous, they attack us, but the tiger isn’t like that. – Female, 55-60 years, Intermediate Forest Chenchu

People in the forest don’t harm the tigers and tigers don’t harm the people. So, co-existence is good. – Male, 33-37 years, Intermediate Forest Chenchu

They [the Chenchu] don’t harm the tigers. In fact, the tigers are protected because of the Chenchu. The poaching and smuggling are controlled by the Chenchu presence. – Male, 55-60 years, ITDA

While “Project Tiger” is the Government’s initiative for the conservation of tigers, the Chenchu, in their own way, expressed sentiments of love and protection toward the tigers.

“Mother” holds a place of high respect among Indian sentiments and therefore referred to anything that is regarded as respectful (Rao, 1999). Many participants in both the Chenchu and Government & NGO groups, used the word “mother” to refer to the forest. “Forest as mother” was a symbolic representation of the Chenchu’s idea of the Nallamala forest. Compared to the Government & NGO participants, a greater number of the Chenchu participants attributed the Nallamala forest as their “mother.” The following direct quotes illustrate perspectives on this:

Yes. The forest is like my mother. I won’t say anything more than this. – Male, 35-40 years, Deep Forest Chenchu

They want to live in a pollution-free environment, and we want to respect it. There is a saying in Telugu “kanna oodru kanna thallilantidi” [homeland is like own mother]. I have seen many people who are living outside but still go to the forest every day to feel the environment. – Male, 43-47 years, NGO.

As the Chenchu are impacted by the various stages of displacement, learning displacement narratives was one of the major aspects of this research. While some Chenchu felt that displacement from the forest was a positive move toward a better life owing to changing times and development, some did not share the same views. In this study, the perspectives of both the Government and NGO workers and the Chenchu people on Chenchu displacement from the forest were analyzed. The participants’ views supporting displacement or opposing displacement were elicited from the interviews and tagged under the codes “Against displacement” and “For displacement.” The percentages of participant responses to these views are shown in Figure 8.

In total, less than half of the Chenchu interlocutors and of the Government & NGO workers were supportive of displacing people from the forest. An NGO respondent said, “When the displaced Chenchu sees the others, then their life also changes” and broadly referred his opinion to the idea of “Sanskritization” (Narasimhachar, 1956) where the migrant communities begin to gain the identity of the host community and therefore gradually merge into the mainstream society. This observation by the NGO respondent was reinforced by a Chenchu respondent as:

We are living in good conditions here. We are educating our children. We can go to hospitals for treatment. We don’t have anything in the forest. We have come here about 10 years back – Male, 73-77 years, Displaced Chenchu.

Comparably, a majority of the Chenchu participants and less than half of the Government & NGO respondents had their views against displacement from the forest. This idea is substantiated by the following narratives:

Going to the towns and living in the towns may be good but there may not be the things we need. The peace and serenity that we have here may not be available in the towns. If in case we fall sick, just by breathing the air here we are cured. We don’t like the smell there and the air there. That’s why we live in the forest. – Male, 30-35 years, Deep Forest Chenchu.

Their [the Chenchu] health has depleted due to changes in their environment. They should live in the forest and be provided with basic facilities. – Male, 35-40 years, ITDA (Coordinator between Chenchu and ITDA).

Development anthropologists have grappled with varied ways of defining development. David Lewis (2012) opines that development is a complex and ambiguous term that has many layers of meaning. (Escobar, 2011, p. 6) critiques Western intervention in the affairs of Third World countries where poverty was problematized to the extent that the idea of “development” emerged as a new domain of thought and experience, which resulted in devising new strategies for dealing with the problem. He goes on to say that “poverty,” “hunger,” and “illiteracy” have gone too far in becoming the major signifiers of “underdevelopment,” which is now almost impossible to sunder. Escobar’s ideas resonate with Said (1979) idea of Orientalism as a “Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient” (p. 3). This research unpacks the Chenchu’s expectations from development projects – land, houses, education, jobs, health, and food – and the fulfillment of these basic needs is also the fundamental marker of the postcolonial development agenda (Gupta, 2001), thus positioning the Chenchu as the postcolonial “beneficiaries of development.” And when the State becomes the forerunner of the population’s well-being, it creates a “governmentality” where not only the Chenchu displacement but also the Chenchu conduct toward the Government gets regulated (Foucault, 1991). In this research, the development agencies cite many factors that limit Chenchu development. Contrastingly, the Chenchu discourses on the criticism and appreciation of government development projects not only evaluate the effectiveness of those projects but also promote the Chenchu as active participants in the making of development rather than mere seekers of development. These views open new channels to fathom development – while not really stating the meaning of development, they provide tools to encounter development from a non-Western lens.

This study adds another thin layer to the existing meanings of development by exploring that development can also mean access to facilities that would make life comfortable. By unpacking this idea from the discourses of the “recipients of development,” or the Chenchu people, the study does not essentialize modernity for development, it only provides an insight into the narratives of development “seekers” and “providers.” Because, many ideas of development, such as freedom, well-being, livestock, self-reliance, and so forth, were also elicited from the discourses that do not really fit into the Western or modern stereotypes of development. This analysis finds a theoretical grounding in the works of many anthropologists as well as economists. For example, Amartya Sen (2001) argues that development must also include freedom and the choice for people to do what they value, and Sarah White (2009) says that well-being can be used as a “new name” for development, which not only includes economic growth but also emphasizes environmental sustainability and human fulfillment. Although only a few Chenchu participants believed in freedom and well-being as development, in terms of safeguarding human rights, freedom of thought, decision-making liberties, and providing safe and hygienic environments, it is important to include those priorities for development policies to achieve positive outcomes of conservation-displacement scenarios.

Access to healthcare facilities, education, jobs, livestock, basic amenities, and well-being was the primary definition of development across groups. While these priorities are voiced by both the “recipients” and “facilitators” of development, they also echo the underlying rationale of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals, which promotes an urgency for achieving economic development, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability (Sachs, 2015). These needs become extremely important to internally displaced communities adjusting to new environments (Pandya, 2013).

Many studies highlight that trust is a prerequisite for strengthening the relationship between the people and the Government (Parasuraman, 1996; Engle, 2010; Padel and Das, 2012). The Government’s awareness of people’s attitudes toward its functions helps the Government better connect with people. During the research, a majority of the Chenchu participants expressed that the Government does not care for Chenchu’s needs and problems and many of them said that they had no access to development. When asked about their opinion on the Government projects, a Displaced Chenchu participant said, “It’s not at all good—very poor. Please write it that way.” It is interesting to learn the different ways participants are expressing their plight through stressing the words, which adds an extra layer of emphasis to their beliefs. These findings help in learning the existing relationship between the Chenchu and the Government and would further help the Government in fostering better bonds with the Chenchu people through any policy modifications.

The research also indicates that less than half of the Chenchu participants supported displacement from the forest and expressed a need for a change in the existing living conditions. This finding adds to the existing literature that discusses the gradual transition of the Chenchu people, owing to either NSTR conservation or tribal development initiatives (Narayan, 2014; Thamminaina, 2015). A sense of self-development or desire to improve the existing living conditions can be seen in the Chenchu people when they defined development as future expectations of their children being in a better position in life than themselves or when they said that securing loans for investing in income-generating activities was development. The Government and NGO sectors also indicated that Chenchu’s awareness of Government projects or progressive thinking toward development was also a form of development. In both arguments, we can see an urge of the Chenchu people to improve and the Government’s plans to improve the living conditions of the Chenchu, indicating an overall interest of both groups in improving the existing conditions. However, some of the Chenchu participants expressed that the Government does not care for their problems and therefore have poor access to development. Whereas some Government & NGO participants argued that the Chenchu habits and perceptions, such as non-mingling with the “mainstream” society, remote dwelling, attitudes of hygiene, and alcoholism, were major hindrances for Chenchu people’s access to development. Therefore, although there is an urge for development from both the Chenchu and the Government, there are some barriers to development as narrated by both groups. This can be related to Li (2007) discussion on the outcomes of development and gaps between the intentions of development and the accomplishments of development.

Although previous studies demonstrate the Chenchu’s love for the Nallamala forest, the creation of the tiger reserve has produced Chenchu subjectivities as “environmental subjects” where their innate love has been reshaped as more formal care and concern for the Nallamala while being employed as anti-poaching squads, ecotourism guides, forest guards, and tiger trackers (Agrawal, 2005; Sen and Lalhrietpui, 2006). However, there arises a question of what makes someone an environmental subject versus environmentally conscious. Perhaps the Chenchu must be viewed as “conservation subjects” rather than environmental subjects because they not only espouse forest protection but also participate in its conservation while facing the repercussions of conservation and displacement. Many studies indicate the conservation practices of the Chenchu people, similar to the findings of this study (Rao and Ramana, 2007; Rao et al., 2007; Reddy, 2014). While both the Chenchu people and the Government & NGO representatives believe that the forest is a necessity for Chenchu development, one of the common phrases that the Chenchu people used to define their regard for the forest was “forest is our mother.” This sentiment is echoed in the studies of the Chipko movement or the Indian tribal “Embrace-the-Tree” movement to protect trees marked for felling (Shiva and Bandyopadhyay, 1986; Bhatt, 1990) where “Forest is our mother” resonated to convey the tribal relationship with the forest. The protection of tigers in the Nallamala forest is a conservation factor for both groups, which resonates with the studies by Karanth and Krithi (2007) that discuss the human-animal relationships in the tiger reserves of India. Also, our research’s findings can be linked to the studies on human-animal conflicts in protected areas (Becker and Vanclay, 2003; Gadgil et al., 1993; Igoe, 2004; Dowie, 2011).

In this study, not only the Chenchu but also some of the Government representatives resist Chenchu’s displacement from the forest. However, any Chenchu voice for displacement would ask for development in return, in terms of better livelihood facilities and a secure future. These expectations navigate through the political ecology discourses on biodiversity conservation through displacement and also in learning the State’s role in the displacement of the people to attain conservation goals (Malkki, 1995; Peet and Watts, 2002; West et al., 2006; Adams and Hutton, 2007).

The development definitions elicited from this study may not be unique but definitely reiterate not only the priorities of impoverished communities but also how they match or not with those of the development agencies. By bringing together the conversations on development, displacement, and biodiversity conservation, the case study not only directs at examining the development narratives from a bottom-up approach but also makes a small effort at adding to the global literature on anthropological interventions in conservation-induced development.

As an anthropological intervention, this study finds a gap between Chenchu’s expectations from development initiatives and the Government’s provisions toward development. As some development projects were beneficial and others were not fetching productive results, it appears that the implementation of development projects is nonuniform. The findings present that the displacement of the Chenchu people was not systematic, leading to a discrepancy in the access to basic livelihood facilities. However, a major limitation of this study is the small sample size. The findings of this study cannot be applied to the entirety of the people or be representative of all the Chenchu people living in the Nallamala forest region and all the Government representatives and NGO workers in that region. As the research was conducted for only 30 days, the time taken to conduct this research was less and therefore cannot be called an in-depth study. Since there were a greater number of male respondents than female respondents, a good balance of perspectives based on gender could not be achieved.

The study suggests some policy changes that would result in effective trade-offs between the Chenchu people and the Government. First, to make development more accessible, Chenchu’s participation in policy decision-making and the formulation of development agendas is vital. Second, there were only two female respondents among 13 Government representatives. To make informed decisions that would serve both men and women, a good balance of gender representation in Government agencies is important. Third, holding regular meetings between the Chenchu and the Government representatives is vital to iron out any discrepancies or gaps in communication.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by IRB Mississippi State University. Written informed consent was not provided because verbal consent was received from the participants before conducting the interviews.

MJ conducted the research and wrote this paper. DH helped in designing the research and reviewing the paper. Both the authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The contribution of many people has been integral to this research. We would like to thank the Department of Anthropology and Middle Eastern Cultures and the Graduate School at Mississippi State University for their support throughout this MA research process. Many thanks to the Chenchu people for sharing their experiences and the ITDA officials, NSTR authorities, and NGO representatives for their time and interest in this research.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2023.1126168/full#supplementary-material

GOI (2005). The report of the tiger task force: Joining the dots. project tiger (New Delhi, India: Union Ministry of Environment and Forests).

Adams W. M., Hutton J. (2007). People, parks and poverty: political ecology and biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Soc. 5 (2), 147–183.

Agrawal A. (2005). Environmentality: Community, intimate government, and the making of environmental subjects in kumaon, India. Curr. Anthropology 46 (2), 161–190. doi: 10.1086/427122

Agrawal A., Redford K. H. (2006). Poverty, development, and biodiversity conservation: Shooting in the dark? (New York: Wildlife Conservation Society), 1530–4426.

Agrawal A., Redford K. (2009). Conservation and displacement: An overview. Conserv. Soc. 7 (1), 1–10. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.54790

Aiyadurai A. (2016). ‘Tigers are our brothers’ understanding human-nature relations in the mishmi hills, northeast India. Conserv. Soc. 14 (4), 305–316. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.197614

AP Tribal Welfare Department (2018–19a). Outcome budget 2018–19 (India: AP Tribal Welfare Department, Government of Andhra Pradesh). Available at: http://www.aptribes.gov.in/Budjet/Out%20Come%20Budget%202018-19%20-%20English%20Version.pdf.

Bagchi A., Jha P. (2011). Fish and fisheries in Indian heritage and development of pisciculture in India. Rev. Fisheries Sci. 19 (2), 85–118. doi: 10.1080/10641262.2010.535046

Becker H. A., Vanclay F. (Eds.) (2003). The international handbook of social impact assessment: Conceptual and methodological advances (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing).

Bernard H. R. (2017). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield).

Bhatt C. P. (1990). The chipko andolan: Forest conservation based on people’s power. Environ. Urbanization 2 (1), 7–18. doi: 10.1177/095624789000200103

Cernea M. (1997). The risks and reconstruction model for resettling displaced populations. World Dev. 25 (10), 1569–1587. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00054-5

Chavez C. (2008). Conceptualizing from the inside: Advantages, complications, and demands on insider positionality. Qual. Rep. 1 (3), 474–494.

Cronon W. (1996). The trouble with wilderness: or, getting back to the wrong nature. Environ. History 1 (1), 7–28. doi: 10.2307/3985059

Damodaran A. (2007). The project tiger crisis in India: Moving away from the policy and economics of selectivity. Environ. Values 16, 61–77. doi: 10.3197/096327107780160328

Dev K. J. A. (2020). Socio-economic conditions of the chenchus – a study in nagarkurool district of the telangana state. Indian J. Appl. Res. 9 (12).

Donthi R. (2014). Tribal development programmes in andhra pradesh: An overview. Dawn J. 3 (1), 817–837.

Dove M. R. (2006). Indigenous people and environmental politics. Annu. Rev. Anthropology 35, 191–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123235

Dowie M. (2011). Conservation refugees: the hundred-year conflict between global conservation and native peoples (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Engle K. (2010). The elusive promise of indigenous development: Rights, culture, strategy (Durham, NC: Duke University Press).

Escobar A. (2011). Encountering development: The making and unmaking of the third world Vol. 1 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Foucault M. (1991). The Foucault effect: Studies in governmentality (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press).

Freitas K. (2006). The Indian caste system as a means of contract enforcement (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University).

Gadgil M., Berkes F., Folke C. (1993). Indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation. Ambio 22, 151–156.

Goswami N. (2013). India's internal security situation: Present realities and future pathways. IDSA monograph series. (India: Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses)

Gupta A. (1997). Agrarian populism in the development Vol. 320 International Development and the Social Sciences: Essays on the History and Politics of Knowledge (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press).

Gupta A. (1998). Postcolonial developments: Agriculture in the making of modern India (Durham, NC: Duke University Press).

Gupta A. (2001). “Governing population: The integrated child development services program in India,” in States of imagination: Ethnographic explorations of the postcolonial state (Oakland, CA: University of California Press), 65–96.

Igoe J. (2004). “Fortress conservation: A social history of national parks,” in Conservation and globalisation: a study of national parks and indigenous communities from East Africa to south Dakota (Belmont: Wadworth/Thomson Learning), 69–102.

Ivanov A. (2014). Chenchus of koornul district: Tradition and reality. Eastern Anthropologist 67, 3–4.

Jammu C., Chalam G. V. (2019). Challenges and remedies of tribal students at primary level (With reference with ITDA KR puram West godavari district). Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. (IRJET) 6 (1), 1243–1254.

Jois M. R. (2015). Ancient Indian law: Eternal values in manu smriti (New Delhi, India: Universal Law Publishing).

Kannabiran K., Sagari R. R., Madhusudhan N., Ashalatha S., Pavan Kumar M. (2010). On the telangana trail. Economic Political Weekly 45, 69–82.

Kapoor D. (2009). Adivasis (original dwellers) “in the way of” state-corporate development: Development dispossession and learning in social action for land and forests in India. McGill J. Education/Revue Des. Sci. l'Education McGill 44 (1), 55–78.

Karanth K. U., Krithi K. K. (2007). Free to move: Conservation and voluntary resettlements in the Western ghats of karnataka, India. In Protected Areas and Human Displacement: A Conservation Perspective (eds Redford K. H., Fearn E.), pp. 48–59. (New York, USA: Wildlife Conservation Society).

Khandelwal V. (2005). Tiger conservation in India – project tiger. Research paper, (New Delhi: Center for Civil Society) India, pp. 1–60. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.773505

Koenig D. (2001). Toward local development and mitigating impoverishment in development-induced displacement and resettlement. final report prepared for ESCOR R7644 and the research programme on development induced displacement and resettlement (Refugee Studies Centre: University of Oxford).

Lee R. B., Daly R. H., Daly R. (Eds.) (1999). The Cambridge encyclopedia of hunters and gatherers (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press).

Lewis D. (2012). “Anthropology and development: The uneasy relationship,” in A handbook of economic anthropology, 2nd ed. (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing).

Li T. M. (2007). The will to improve: Governmentality, development, and the practice of politics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press).

Lozano J., Olszańska A., Morales-Reyes Z., Castro A. A., Malo A. F., Moleón M., et al. (2019). Human-carnivore relations: a systematic review. Biol. Conserv. 237, 480–492. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.07.002

Mahapatra L. K. (2002). “Customary rights in land and forest and the state,” in Tribal and indigenous people of India: Problem and prospect. Eds. Pati R. N., Dash J. (Delhi: APH Publishing Co), 379–397.

Mahapatra A. K., Tewari D. D., Baboo B. (2015). Displacement, deprivation and development: the impact of relocation on income and livelihood of tribes in Similipal tiger and biosphere reserve, India. Environmental Management 56, 420–432.

Malkki L. H. (1995). Refugees and exile: From “refugee studies” to the national order of things. Annu. Rev. Anthropology 24 (1), 495–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.002431

Ministry of Tribal Affairs (2015) Development of particularly vulnerable tribal groups. Available at: https://tribal.nic.in/writereaddata/Schemes/4-5NGORevisedScheme.pdf.

Mondal B. K., Das R. (2023). “Appliance of indigenous knowledge in mangrove conservation and sustaining livelihood in Indian sundarban delta: A geospatial analysis,” in Traditional ecological knowledge of resource management in Asia (Manhattan, NY: Springer International Publishing), 77–101.

Morris M. W., Leung K., Ames D., Lickel B. (1999). Views from inside and outside: Integrating emic and etic insights about culture and justice judgment. Acad. Manage. Rev. 24 (4), 781–796. doi: 10.2307/259354

Narasimhachar S. M. (1956). A note on sanskritization and westernization. J. Asian Stud. 15 (4), 481–496.

Narayan M. (2014). Of foolish ancestors, and land over weapons. J. Internal Displacement 4 (2), 66–78.

National Tiger Conservation Authority/Project Tiger (2006). Evaluation reports of tiger reserves in India (New Delhi: National Tiger Conservation Authority). Available at: https://projecttiger.nic.in/WriteReadData/PublicationFile/Evaluation%20Reports%20of%20Tiger%20Reserves%20in%20India%202006.pdf.

National Tiger Conservation Authority/Project Tiger (2018a) Status of tigers in India-2018. Available at: https://ntca.gov.in/assets/uploads/Reports/AITM/Status_Tigers_India_summary_2018.pdf.

National Tiger Conservation Authority/Project Tiger (2018b). Available at: https://projecttiger.nic.in/Ntcamap/108_1_48_mapdetails.aspx.