94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

COMMUNITY CASE STUDY article

Front. Conserv. Sci., 15 November 2022

Sec. Human-Wildlife Interactions

Volume 3 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2022.989833

This article is part of the Research TopicHuman-Elephant Conflict and Coexistence in AsiaView all 5 articles

Oil palm managers are one of the key stakeholders who could help strengthen efforts to protect elephants in the landscape. We used a Theory of Change (ToC) approach to hypothesize potential barriers and benefits to managers adopting best practise. We conducted two workshopss with more than 60 participants to better understand managers’ perceptions of Human Elephant Conflict (HEC) and their willingness to adopt better wildlife management practices. The workshops confirmed that some of the outcomes we perceived in the original ToC, including security issues, false accusations, negative perceptions by the international community and crop damage, were affecting their willingness to promote coexistence in their plantation. However, we also uncovered other potential barriers and opportunities to promote coexistence, including international and national standards that do not provide enough technical and practical guidance for all levels, expensive monitoring costs, and inconsistent collaboration among industry players and between government and non-government agencies. Our initial findings suggest that new attitudes and perceptions have not been explored before and may be critical for manager engagement and adoption of best practices for HEC, as well as the identification of new audiences that would need to be engaged to be successful in achieving elephant conservation goals.

Many developing countries in Southeast Asia still depend heavily on logging and agriculture industries for their economic growth (Laurance et al., 2014; Murphy et al., 2021). For instance, tropical lowland forests on Borneo Island in Sabah were initially exploited for logging before being converted to monoculture plantations, mainly oil palm (Reynolds et al., 2011; Bryan et al., 2013). It was estimated that 7.9 Mha of the Borneo Island landmass is currently planted with oil palm (Gaveau et al., 2014). The continuous land-use changes for these socio-economic purposes have significantly disrupted the migration and feeding grounds for threatened and large mammal species, such as orangutan (Pongo pgymaeus), elephant (Elephas maximus) and sun bear (Helarctos malayanus) (Ancrenaz et al., 2014; Guharajan et al., 2019; Evans et al., 2020; de la Torre et al., 2021). Consequently, human-wildlife conflict (HWC) issues have risen due to crops depredation, property damage, concerns about safety and inevitably loss of life for humans and wildlife (Clements et al., 2010; Othman et al., 2013; Rubino et al., 2020).

Nevertheless, HWC in the oil palm landscapes particularly with orangutan and elephants could be minimized by improving landscape connectivity and retaining forest patches, even when those patches are small, fragmented and degraded (Estes et al., 2012; Ancrenaz et al., 2014; Othman et al., 2019; Oram et al., 2022). Recently, the Sabah Elephant Action Plan 2020-2029 was formulated with all relevant stakeholders and approved by the Sabah government in 2020. This document serves as a guidance for all stakeholders on the strategies, priorities, and actions for elephant conservation. Among the recommendations include the development of a standard operating procedure (SOP) on the best practices to mitigate human-elephant conflicts (HEC). Although the development of the SOP is not compulsory and has no legislation implication for any stakeholders, the SOP could support the implementation of a protocol suitable for management and mitigation, particularly in oil palm plantations. In order ensure the adoption of the SOP, we identified the need to deeply connect with, and understand the experiences of palm oil managers; a group that is often seen asthe enemy in international conservation discourse (Oram et al., 2022).

In this paper, we aim to document the challenges and concern faced by oil palm managers to support Bornean elephant (Elephas maximus borneensis) conservation program in the oil palm landscape within Lower Kinabatangan landscape. We apply a theory of change (ToC) approach based on conservation psychology and behaviour change, and apply participatory methods (Maynard et al., 2022) to better understand what would it take for palm oil management to implement coexistence practices on their properties and support coexistence We believe that, through this participatory approach, SOP practices will be adopted, thus improving elephant movement in human-transformed landscape, and reducing HEC.

Kinabatangan landscape is highly fragmented due to the commercial logging which started circa 1950s until the 1970s before the land were converted to oil palm plantations in the 1980s (Hai et al., 2001). Despite of 400 km2 of land under wildlife sanctuary, Bornean elephants can only utilize about 184 km2 of the area due natural barriers (for example limestone outcropping and swamp) and non-natural barriers (electric fences and elephant proof trenches) within their home range. Since private land owners converted their lands to agriculture activities due to the government policies, thus creating longer and narrower bottlenecks to movement, especially surrounding the Sukau village (Estes et al., 2012; Abram et al., 2014). From our observation, elephant’s movement are no longer predictable and they are found in smaller group sizes.

Our focal stakeholder groups were the assistant managers and sustainability officers from eleven large size (>10,000 ha) and medium size (between 5,000-10,000 ha) oil palm companies situated within the Lower Kinabatangan landscape (Figure 1). Assistant managers are usually the head of an oil palm division. They are responsible for managing HEC issues on the ground and ensuring the implementation of best mitigation practices in line with the company’s target for sustainability. In addition, their role includes arranging training for upper management and general workers regarding HEC mitigation if needed. Meanwhile, the sustainability officers are responsible for ensuring that the operation department complies with the certification needs and developing new sustainability strategies according to the needs of certification bodies.

We conducted two virtual workshops in November 2021 and February 2022 on Zoom (Table 1). Both workshops were conducted in Bahasa Malaysia and recorded with the participants’ permission. The objectives of the first workshops were to understand the challenges and barriers faced by the oil palm players to adopt co-existence. We started the discussion by asking participantsdo you have any challenges in the human-elephant conflict in your landscape? For this question, each participant wrote down keywords of their concerns on the Mural app. From these individual responses, we asked the participants from the same plantations to collectively select what they believed as the top three issues and concerns for their company. In the next session, we identified the common issues and concerns which are faced by all oil palm plantations at Lower Kinabatangan to create co-existence. The second virtual workshop was to co-plan the best practices included in the SOP document and further explore the challenges for the oil palm companies to adopt the SOP as part of their sustainability policy. The participants also shared their current practices and identified the improvement needed in the SOP with guidance from the facilitator.

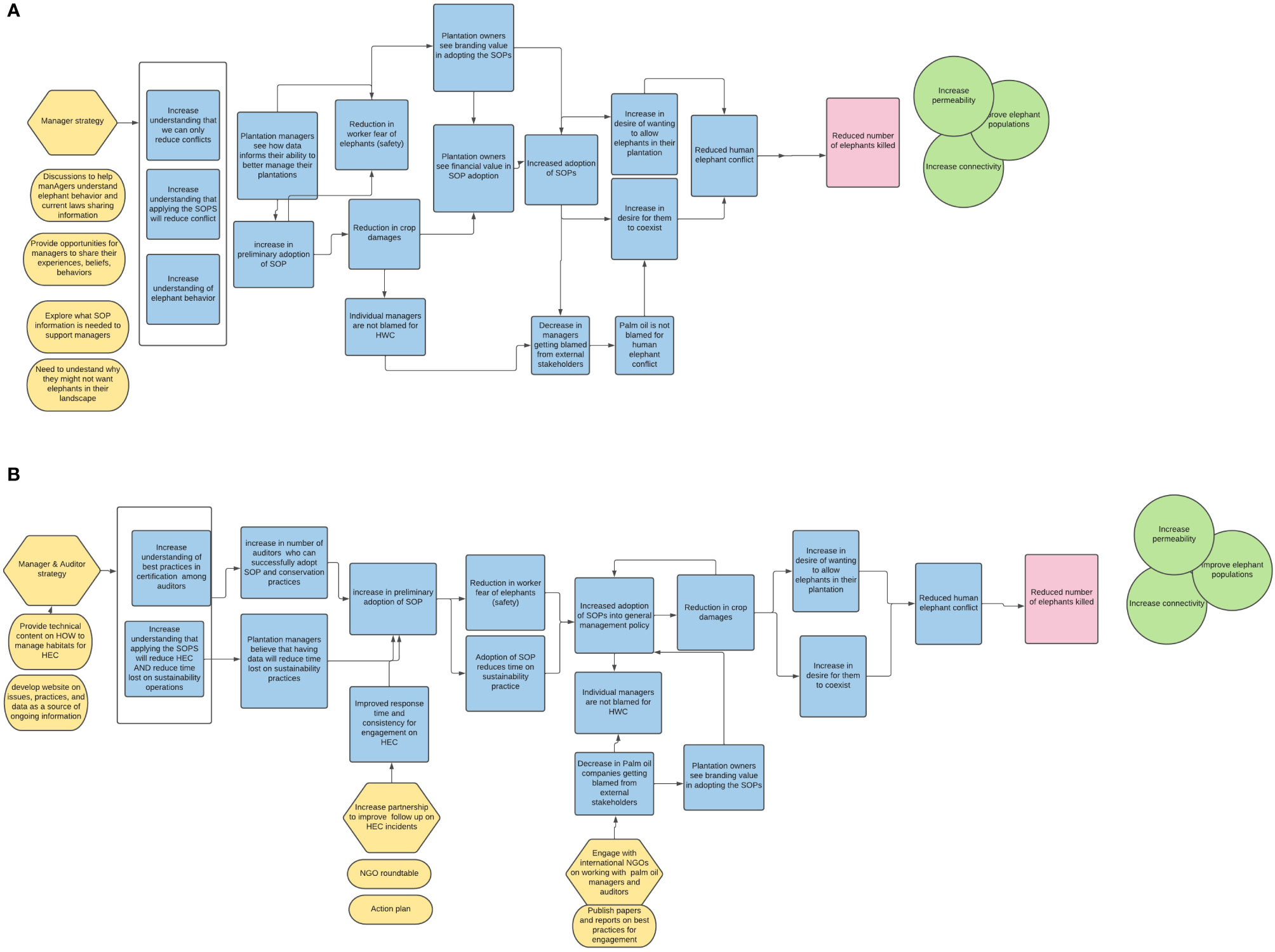

We developed a ToC to hypothesize the potential outcomes needed to shift manager and palm oil plantation leadership perspectives in addressing human-elephant conflict (Figure 2) (Funnell and Rogers, 2011; Maynard et al., 2022). This hypothesis of impact was based on deep expertise in the region from the authors, as well as grounded in elements of behavioral psychology and behavior change campaigns (Prochaska et al., 1992; Green et al., 2019). This ToC model served as an initial starting point for developmental evaluation (Patton, 2010); an approach that allows for innovation and testing without certainty to continue to refine and define our ToC, as working with palm oil plantation managers is an approach that is not traditionally implemented in other areas of HEC. Our aim was to document the challenges and concerns facing oil palm managers to adopt SOP and support elephant conservation programs in the oil palm landscape, and build from the experiences from Maynard et al. (2022) to begin testing the benefits of collaborative planning and engagement with potential adversaries.

Figure 2 (A) Our original theory of change for strategy implementation and adoption of the SOP based on the expertise of the authors (B) Our updated theory of change based on our preliminary workshopss with managers.

We used the ToC as a starting point for structured workshopss and workshops with plantation managers. Key workshops questions that emerged from our ToC included:

1. What do managers understand about elephant ecology, behavior, and population status? What role does that play in their desire to engage in HEC solutions?

2. What do managers feel are the greatest barriers to adopting HEC solutions? What might they need to overcome those barriers?

3. What role would an SOP play in improving manager responses to HEC? Is there an interest or willingness in adopting and implementing the SOP?

4. What do managers need in an SOP to make it successful and create a shared vision of success?

5. What roles does the conservation community play in disincentivizing plantation responses to HEC?

We used an edited transcript approach (cleaned and edited by organizers for clarity and context) and basic qualitative coding to find key themes and patterns in relation to our theory of change. Coding was done by colour coding in Word. We started with themes associated with the preliminary Theory of Change (Figure 2A), and then used emergent coding to identify new concepts or ideas that surfaced that were different from the author’s expectations outlined in the ToC.

Minimizing HEC in the oil palm landscape is a critical priority for successful conservation of elephants as well as sustainable operations of oil palm industries. Current strategies to manage elephant presence in the oil palm landscape primarily focus on short term mitigation which either physical separation or temporarily removing the problem by translocating problematic elephants without considering these activities are sustainable or impactful (Othman et al., 2019; Shaffer et al., 2019; Oram et al., 2022). Shifting the paradigm from conflict to coexistence require us to go beyond education and awareness to aligning strategies based on better understanding audience barriers and needs (Zimmermann et al., 2020). Our workshopss have identified several new barriers that had not surfaced in initial ToC development, which we describe, along with potential solution below.

Both voluntary (RSPO) and mandatory (MSPO) certifications require oil palm producers to preserve biodiversity in their plantations, including developing responsible measures to resolve human-wildlife conflicts (see Principle 7 and Principle 5, respectively). However, participants noted that neither standard provide clear measures to be taken by producers, especially when dealing with a highly intelligent and social animal like the elephant. One consistent example shared was that when elephants are found dead in an oil palm plantation, either due to intentional (retaliatory killing) or unintentional (accumulation of heavy metals), the producers will receive multiple queries that lead to the issuance of non-conformances, jeopardizing their sustainability certification status. Hence, it is ataboo to have wildlife in the plantations and oil palm growers are reluctant to manage or report elephants, and prefer to prevent the entry of elephants into oil palm plantations and/or request the wildlife department to translocate them (similar to Othman et al., 2019). Without prior information about the conflict situation in the landscapes, most compliance assessments are based on the certification requirement’s checklist and subjected to auditor’s knowledge and background on the subject matter.

Participants shared that elephant presence in the oil palm can heighten the risk of crop depredation, particularly in the newly planted area. Oil palm trees below 5 years old are vulnerable to depredation by elephants, which could potentially causing significant financial losses (Othman et al., 2019; Ghani, 2019). Based on our discussion, the impacts of crop depredation are more severe for smallholder growers as oil palm is their main income to support their livelihood. In addition, there will be an increase in other costs such as hiring competent workers to guard these sensitive areas, installing warning and awareness signboards and providing training to the workers on elephant behaviour. Hence, most managers would opt to secure their plantations with electric fencing or elephant proof trenches to prevent elephants from entering their plantations to avoid ongoing HEC costs, and loss of production.

Another new barrier that the participants identified during the workshop was inconsistent engagement and communication within the management of oil palm companies. Participants agreed that regular changes to the management, either at the plantation level or at the headquarters, will usually influence the idea and decisions of the managers on how to manage biodiversity in that particular plantation. These changes can be positive or negative depending on the understanding and awareness of the new manager about biodiversity conservation and sustainability. The participants added that engagement and communication with other stakeholders, particularly with the non-governmental organization, could also change depending on the organization’s current goal and strategic plan.

Palm oil is here to stay. Thus, finding common ground for conservation friendly practices and strategies to minimize human elephant conflict the oil palm landscape is critical. To alleviate the barriers, we recommend that there should be a specific working group consisting of all relevant stakeholder in that region, including small to large oil palm growers, government departments and conservation NGOs. The aim of this working group is for the members to work together to plan and implement the mitigation and conservation strategies in order for the coexistence to be achieved at the landscape level. The members of the group could come together to develop a standard operation procedure (SOP) which could guide all oil palm plantations at the landscape level on the best practices to manage HEC. Currently, there are several working groups formed by NGOs in the district of Tawau/Kalabakan, Beluran and Tabin and chaired by the Wildlife District Officer or the District Officer. It is important for every standard auditor to have a stakeholder consultation with the members of the working group to better understand the HEC issues, efforts, and challenges faced by the members as a coalition. In addition, we concur with the recommendations given in the Malaysian National Interpretation for the Management and Monitoring of High Conservation Values (MYNI) that we should focus on improving elephants’ movement ability in the oil palm landscapes. For example, we could install physical barriers such as electric fences with consultative planning and focusing only surrounding sensitive areas. At the same time, workers should have been exposed with basic knowledge and skills from time to time on elephant behaviour to know the do’s and don’ts while dealing with elephants, which will avoid unfortunate incidents.

We also recommend that there should be acoexistence fund created among the members of the working group, to cover all the cost related to managing HEC at the landscape level. Some of the costs that the fund could cover include: purchasing elephant collars to identify hotspots and movement patterns in the area, setting up a competent elephant control team to peacefully divert the elephant to less-sensitive zones, and maintaining the integrated electric fencing. To ensure a good partnership and the sustainability of this fund, each of the oil palm companies must be committed to include this requirement as the company’s policy as part of their commitment to adhere to the sustainable oil palm certification. In addition, we also recommend that other parties such as corporations, banks, international organizations, and other individuals who have vested interest in either oil palm sustainability or HEC be able to contribute financially to this fund.

The results from our work highlight the potential benefits of working with palm oil plantation staff as partners in reducing HEC. We believe that co-management and partnerships can be an effective way to reduce the impacts on wildlife but international palm oil campaign pressure makes developing these partnerships more challenging. Therefore, we must strive to developing a shared vision to engage diverse stakeholders and also potential partners, previously seen as adversaries, in creating co-existence in the oil palm landscapes. We believe that through this type of engagement we can reimagine the sustainability of the Malaysia palm oil industry.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

NO conceived and developed the project. AD analyzed the data. NO wrote the original draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by the USFWS Asian Elephant Conservation Fund, Full Circle Foundation and Houston Zoo.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abram N. K., Xofis P., Tzanopoulos J., Macmillan D. C., Ancrenaz M., Chung R., et al. (2014). Synergies for improving oil palm production and forest conservation in floodplain landscapes. PloS One 9 (6), 1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095388

Ancrenaz M., Oram F., Ambu L., Lackman I., Ahmad E., Elahan M., et al. (2014). Of Pongo, palms and perceptions: A multidisciplinary assessment of bornean orang-utans pongo pygmaeus in an oil palm context. Oryx 49, 1–8. doi: 10.1017/S0030605313001270

Bryan J. E., Shearman P. L., Asner G. P., Knapp D. E., Aoro G., Lokes B. (2013). Extreme differences in forest degradation in Borneo: Comparing practices in Sarawak, sabah, and Brunei. PloS One 8 (7), e69679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069679

Clements R., Rayan D. M., Zafir A. W. A., Venkataraman A., Alfred R., Payne J., et al. (2010). Trio under threat: Can we secure the future of rhinos, elephants and tigers in Malaysia? Biodiversity Conserv. 19 (4), 1115–1365. doi: 10.1007/s10531-009-9775-3

de la Torre J. A., Wong E. P., Lechner A. M., Zulaikha N., Zawawi A., Abdul-Patah P., et al. (2021). There will be conflict – agricultural landscapes are prime, rather than marginal, habitats for Asian elephants. Anim. Conserv. 24 (5), 720–732. doi: 10.1111/acv.12668

Estes J. G., Othman N., Ismail S., Ancrenaz M., Goossens B., Ambu L. N., et al. (2012). Quantity and configuration of available elephant habitat and related conservation concerns in the lower kinabatangan floodplain of sabah, Malaysia. PloS One 7 (10), e44601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044601

Evans L. J., Goossens B., Davies A. B., Reynolds G., Asner G. P. (2020). Natural and anthropogenic drivers of bornean elephant movement strategies. Global Ecol. Conserv. 22, e00906. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e00906

Funnell S. C., Rogers P. J. (2011). Purposeful program theory: Effective use of theories of change and logic models (San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons).

Gaveau D. L.A., Sloan S., Molidena E., Yaen H., Sheil D., Abram N. K., et al. (2014). Four decades of forest persistence, clearance and logging on Borneo. PloS One 9 (7), 1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101654

Ghani N. A. Ab. (2019). Developing an evidence basec policy and protocol for human elephant conflict in oil palm plantations: A case study of sime Darby plantation berhad (Selangor: Nottingham University), Selangor.

Green K. M., Crawford B. A., Williamson K. A., DeWan A. A. (2019). A meta-analysis of social marketing campaigns to improve global conservation outcomes. Soc. Marketing Q. 25 (1), 69–875. doi: 10.1177/152450041882

Guharajan R., Abram N. K., Magguna M. A., Goossens B., Wong S. Te, Nathan S. K. S. S., et al. (2019). Does the vulnerable sun bear helarctos malayanus damage crops and threaten people in oil palm plantations? Oryx 53 (4), 611–195. doi: 10.1017/S0030605317001089

Hai T. C., Ng A., Prudente C., Pang C., Yess J. T. C. (2001). “Balancing the need for sustainable oil palm development and conservation: The lower kinabatangan floodplains experience,” in Strategic directions for the sustainability of the oil palm industry(Kota Kinabalu: WWF Malaysia), 1–53. Available at: http://assets.panda.org/downloads/balancingtheneed.pdf.

Laurance W. F., Sayer J., Cassman K. G. (2014). Agricultural expansion and its impacts on tropical nature. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 29, 107–116.

Maynard L., Howorth P., Daniels J., Bunney K.-L., Snyder R., Jenike D., et al. (2022). Conservation psychology strategies for collaborative planning and impact evaluation. Zoo Biol. 41, 425–438 doi: 10.1002/zoo.21692

Murphy D. J., Goggin K., Paterson R.R. M. (2021). Oil palm in the 2020s and beyond: Challenges and solutions. CABI Agric. Bioscience 2 (1), 1–225. doi: 10.1186/s43170-021-00058-3

Oram F., Kapar M. D., Saharon A. R., Elahan H., Segaran P., Poloi S., et al. (2022). "Engaging the enemy: Orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus morio) conservation in human modified environments in the kinabatangan floodplain of sabah, Malaysian Borneo. Int. J. Primatology. doi: 10.1007/s10764-022-00288-w

Othman N., Fernando P., Yoganand K., Ancrenaz M., Alfred R., Nathan S., et al. (2013). Elephant conservation and mitigation of human-elephant conflict in government of Malaysia-UNDP multiple-use forest landscapes project area in sabah. Gajah 39, 19–23.

Othman N., Goossens B., Cheah C., Nathan S., Bumpus R., Ancrenaz M. (2019). Shift of paradigm needed towards improving human–elephant coexistence in monoculture landscapes in sabah. Int. Zoo Yearbook 53, 1–13. doi: 10.1111/izy.12226

Patton M. Q. (2010). Developmental evaluation: Applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use (New York: Guilford Press).

Prochaska J. O., Diclemente C. C., Norcross J. C. (1992). In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. Am. Psychol. 47 (9), 1102–1145. doi: 10.3109/10884609309149692

Reynolds G., Payne J., Sinun W., Mosigil G., Walsh R. P.D., Reynolds G., et al. (2011). Changes in forest land use and management in sabah , Malaysian Borneo , 1990 – 2010 , with a focus on the danum valley region changes in forest land use and management in sabah , Malaysian Borneo , 1990 – 2010 , with a focus on the danum valley region. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 366, 3168–3176. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0154

Rubino E. C., Serenari C., Othman N., Ancrenaz M., Sarjono F., Eddie A. (2020). Viewing bornean human – elephant conflicts through an environmental justice lens. Human-Wildlife Interact. 14 (3), 487–5045. K.

Shaffer L.J., Khadka K. K., Hoek J. V. D., Naithani K. J. (2019). Human-elephant conflict: A review of current management strategies and future directions. Front. Ecol. Evol. 6. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2018.00235

Keywords: Theory of Change, human-elephant conflict, oil palm, Bornean elephant, Borneo

Citation: Othman N, Mustapah MA-S, Quilter AG and DeWan A (2022) Understanding barriers and benefits to adopting elephant coexistence practices in oil palm plantation landscapes in Lower Kinabatangan, Sabah. Front. Conserv. Sci. 3:989833. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2022.989833

Received: 08 July 2022; Accepted: 05 October 2022;

Published: 15 November 2022.

Edited by:

Alexandra Zimmermann, University of Oxford, United KingdomReviewed by:

Jennifer Bond, Charles Sturt University, AustraliaCopyright © 2022 Othman, Mustapah, Quilter and DeWan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nurzhafarina Othman, bnVyemhhZmFyaW5hQHVtcy5lZHUubXk=; Amielle DeWan, YW1pZWxsZUBpbXBhY3RieWRlc2lnbmluYy5vcmc=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.