- 1Department of Zoology and Biodiversity Research Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 2Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 3Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada

- 4Laboratoire de Biologie Eau et Environnement (LBEE), Faculté des Sciences de la Nature et de la Vie et des Sciences de la Terre et de l'Univers, Université 8 Mai 1945, Guelma, Algeria

- 5Ecosystem Management, Department of Environmental Systems Science, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Anthropogenic wildlife exploitation threatens biodiversity worldwide. With the emergence of online trading which facilitates the physical movement of wildlife across countries and continents, wildlife conservation is more challenging than ever. One form of wildlife exploitation involves no physical movement of organisms, presenting new challenges. It consists of hunting and fishing “experiments” for monetized online entertainment. Here we analyze >200 online videos of these so-called experiments in the world's largest video platform (YouTube). These videos generated about half a billion views between 2019 and 2020. The number of target species (including threatened animals), videos, and views increased rapidly during this period. The material used in these experiments raises serious ethical questions about animal welfare and the normalization of violence to animals on the Internet. The emergence of this phenomenon highlights the need for online restriction of this type of content to limit the spread of animal cruelty and the damage to global biodiversity. It also sheds light on some conservation gaps in the virtual sphere of the Internet which offers biodiversity-related business models that has the potential to spread globally.

Introduction

Biodiversity is threatened by anthropogenic factors worldwide (Johnson et al., 2017; Arneth et al., 2020; Tickner et al., 2020). Excessive wildlife hunting has important consequences on population dynamics and may lead to extinction (Khelifa et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2021) and disruption of ecosystem functioning (Peres et al., 2016; Bogoni et al., 2020). Wildlife has been hunted and traded for centuries locally and internationally for consumption, ornamentation, clothing, and medicine. Despite substantial investment in wildlife conservation, illegal trading maintains substantial pressure on natural populations (Zhang and Yin, 2014; Van Roon et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2020). More recently, the Internet has created a new landscape of online illegal trading which amplifies the outreach, facilitates the trading process, and increases transactions nationally and internationally (Sung and Fong, 2018; Wong et al., 2020). Due to the rapid evolution of the Internet, wildlife conservation needs to be in a constant arms race to combat new emerging online-based threats.

Online platforms and social media have unprecedented potential in sharing information and connecting people. They have shown outstanding efficiency in public mobilization and fundraising for humanitarian initiatives and environmental engagement (Pantti, 2015; Vu et al., 2021). However, the same platforms also present a serious threat in disseminating problematic material (El Bizri et al., 2015; Lenzi et al., 2020; Mclean et al., 2021) that might expand across countries and continents and inflict major environmental damage. Here we document a new trend of “hunting–fishing–experiments” (HFE) for online entertainment. HFE videos are documentary-like content that captures on film various unique ways of catching animals, often with unethical and accessible methods. These “experiments” have become popular on the Internet, particularly on YouTube, affecting both a diverse array of taxa and their habitats. These practices both raise serious ethical questions about normalizing violence to animals and spreading content harmful to animal welfare and present a new complex challenge for wildlife conservation.

Due to their global outreach, online platforms may contribute indirectly to the disturbance of biodiversity in the wild on a global scale (Sajeva et al., 2013; Pagel et al., 2020; Van Hamme et al., 2021). YouTube, in particular, is the second most visited website and the largest video platform in the world (Alexa Internet, 2020), receiving 2.1 billion users in 2020 and >500 h of video uploaded every minute (August 2020) (Statista, 2021). Because wildlife, fishing, and hunting attract large viewership, practices captured on video might likely be replicated by the public regardless of their ethical aspect (Siddiqui, 2021). Furthermore, YouTube is also a rewarding platform where video creators can earn money, followers, and public acclaim (Burgess and Green, 2018), which might accentuate the motivation to reproduce unethical hunting and fishing content and increase its environmental impacts. To date, there has been little surveillance of Internet activities likely to harm wildlife within contemporary wildlife conservation.

Here, we document the HFE phenomenon by assessing its spatiotemporal evolution, identify the target species, determine the techniques used in the experiments, and investigate the occurrence of a financial niche. Here, we analyze 206 videos (total duration: 25.74 h) recorded between 01 Jan. 2019–10 Jan. 2020 on YouTube, and we specifically determine (1) the temporal trend of the number of published videos and viewership, (2) the identity of the target organisms, (3) the geographic distribution of this activity, (4) the motivation and benefits from making and publishing these videos, and (5) the material and techniques used. In addition, we determine whether the current YouTube surveillance mechanisms (including algorithm) are effective in removing HFE content by checking the status of the video 7 months after our initial investigation. To our knowledge, this phenomenon is relatively new, and thus the current contribution sheds light on some conservation gaps that necessitate the establishment of effective policies for regulating threats to biodiversity currently marketed as online entertainment.

Materials and Methods

Background About HFE

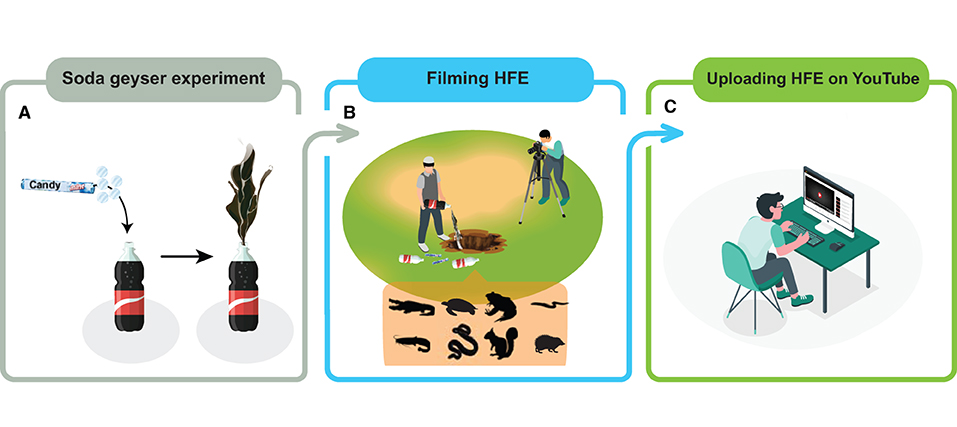

The origin of HFE is most likely a derivative of the soda-candy geyser experiment (a chemical reaction that induces a rapid release of dissolved CO2 from the beverage) (Van Looy, 2016) (Figure 1), which gained a lot of attention on the internet in recent years. The first HFE videos on YouTube used the soda-candy geyser experiment to catch fish. This consisted of pouring the soda-candy mix into a fish burrow (a hole in the ground), resulting in the escape of the fish from the water due to suffocation. These videos became “viral” probably after being shared through social media networks and recommended by YouTube (Zhou et al., 2016). More HFE videos were uploaded on the internet, targeting different burrowing species and using different tools to catch them.

Figure 1. Emergence of the so-called hunting–fishing–experiments (HFE). (A) Soda geyser experiment: before HFE, a popular content on YouTube was the Soda geyser experiment which consists of mixing soda with mint candy to provoke a chemical reaction that rapidly releases dissolved CO2 from the soda. (B) Filming HFE: recently, people started using the soda geyser (with other products) to fish and hunt animals that use burrows while recording on film. (C) HFE content is typically edited in a documentary style then uploaded on YouTube.

Data Collection and Analysis

To determine the number of videos containing unethical hunting-fishing-experiment (HFE) on YouTube, we searched for videos by looking for these keywords: “fishing experiments,” “fishing with soda,” “Coca Cola and Mentos Fishing,” “Coke and Mentos fishing” and “hunting with soda” between January 5th and 10th, 2020. We used soda in the keywords because it was consistently used in HFE (the main ingredient). After clicking search, YouTube generates a list of videos related to the keywords, and whenever a video is selected, YouTube suggests other videos with similar content (so-called recommendations) on the right-hand side of the watch page. Considering both the generated and recommended list of videos provides a good representation of the searched content on the platform. We viewed all videos in the generated list as well as in the suggested list, and we collected data only on videos that included animals. For such videos, we recorded the channel name, date of publication, number of views, likes, dislikes, and comments, as well as the duration. We determined the country of the video by combining information from vidIQ (Google Chrome extension for YouTube analytics), asking the owner of the video, and looking at the language they use in the comment section of YouTube and social media. The “tools” used for HFE were recorded and categorized into edibles (non-animal material such as soda, candy, milk, spices etc.), chemicals (e.g., detergent, toothpaste), and animal baits (e.g., ducklings, turtle, chicken). We also categorized these tools into three categories of environmental invasiveness: less likely, likely, and highly likely to affect the habitat quality, the target species, and/or non-target species. Target species were identified when possible and their IUCN conservation status was obtained from the IUCN Red List (https://www.iucnredlist.org/). We calculated the cumulative sum of the number of videos and views across the date of publication. The target animal species were grouped into classes (fish, reptile, mammal, amphibian, bird, crustacean, and arachnid) and the frequency of each class was calculated. Assessing the diversity of target species and the potential environmental impacts of the material used is important to evaluate the threat of HFE to biodiversity. In fact, the diversification of the video content to entertain and satisfy an audience with HFE could be a function of the number of target species and materials used in fishing and hunting. To understand this aspect, we assessed the temporal pattern of the number of species and materials used.

Understanding whether there is a financial niche in HFE is key to developing policies to limit this trend (Bennett et al., 2017). To determine whether the video creator intended to monetize the HFE content, we looked for the occurrence of ads in the videos because the latter turn on when the user activates the monetization. To obtain an estimation of the potential amount of money that could be generated by the HFE videos (in order to understand the motivation of making these videos), we used the website Social Blade (https://socialblade.com/) which is a website that presents data and analytics for major video, streaming and social media platforms. We calculated the average revenue from the minimum and maximum ([max + min]/2) and estimated the rate of revenue earning by the number of views.

According to YouTube, animal abuse content is “(1) Content where animals are encouraged or coerced to fight by humans; (2) Content that includes a human maliciously causing an animal to experience suffering when not for traditional or standard purposes such as hunting or food preparation; (3) Content featuring animal rescue that has been staged and places the animal in harmful scenarios” (YouTube, 2021). We think that HFEs are against the guideline of YouTube and should be removed by the platform as they depict violence or abuse toward animals. To determine whether the YouTube algorithm is effective in detecting and removing HFE content, we revisited all videos on 08th July 2020 (7 months after our initial assessment) and recorded whether the video was still available or not (unavailability of the video might reflect a content being taken down). For the videos that were still available, we calculated the number of days from their date of publication to 08th July 2020 to assess the potential of HFE content to stay available on YouTube without being removed.

Results and Discussion

Social Following and Financial Gain

There are financial benefits that come from advertisement revenue generated by HFE videos. The channels that posted videos are followed by an average of 183,696 subscribers (2,210–1,510,000). The HFE videos have an average of 362.4 interactions (comments) and 4.5 like:dislike ratio, which indicates that the audience tends to like more than dislike the content. We found that 90% were monetized. We found that videos generated a revenue of 2$ per 1,000 views. On average, the videos made 5,642$ ranging from 1,282 to 10,003$.

Spread of HFE Content

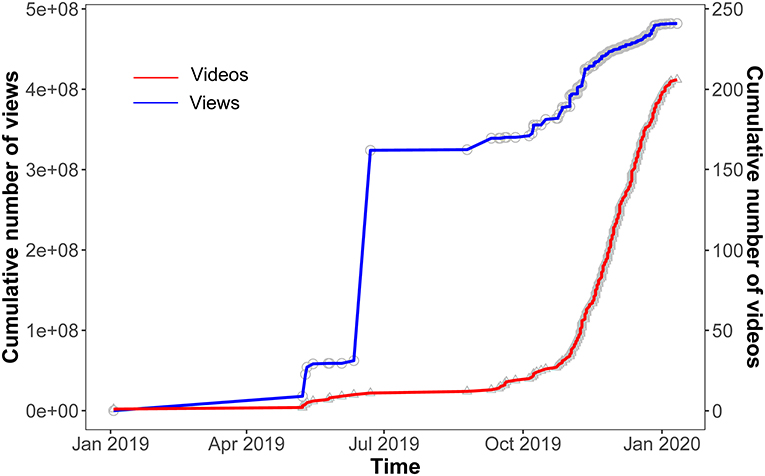

We have gathered data on the HFE content on YouTube and we found a remarkable increase in the number of videos during January 2019 and January 2020 (total = 206 videos) where 91.3% of them were uploaded between October and January 2020 (Figure 2). These videos accumulated ~0.5 billion views from 43 channels, equivalent to an average of ~25,000 views per day. Along with the rapid increase in the number of videos, an increase in the number of channels uploading HFE content was recorded (Supplementary Figure S1). Interestingly, the videos originated from Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Thailand, India, Singapore, Bangladesh, Vietnam, and China); an area that hosts important biodiversity hotspots such as Sundaland and Nicobar islands of India, Wallacea, Philippines, and Indo-Burma, India and Myanmar, which harbor a total of 1,500–15,000 endemic plants and 518–701 endemic vertebrate species, representing 0.5–5 and 1.9–2.6% of global biodiversity of these groups, respectively (Myers et al., 2000). Understanding the spatiotemporal evolution of a new environmental threat is crucial to estimate the speed of its geographic spread, pinpoint where immediate efforts should be spent, predict its potential consequences on biodiversity, and establish effective management plans.

Figure 2. Temporal pattern of the hunting and fishing experiment videos published on YouTube during the period Jan 2019–Jan 2020. Cumulative number of videos (red line, triangle) and views (blue line, circle). We note that the data presented here were only based on 1 year and does not take into account the potential effect of seasonal variability in the vulnerability of species to exploitation in their natural environment (wet vs. dry season).

However, it is difficult to determine the geographic spread of HFE as such a practice could be carried out without posting videos on the Internet. It might be that the geographic distribution observed on YouTube is just the tip of the iceberg. With the role of social media networks (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Reddit), the HFE phenomenon could have reached other countries where poverty is high, biodiversity is easily accessible, and environmental regulation is not effective. In addition, our search was carried out only in English, and thus might underestimate the extent of the phenomenon.

Target Species and Techniques

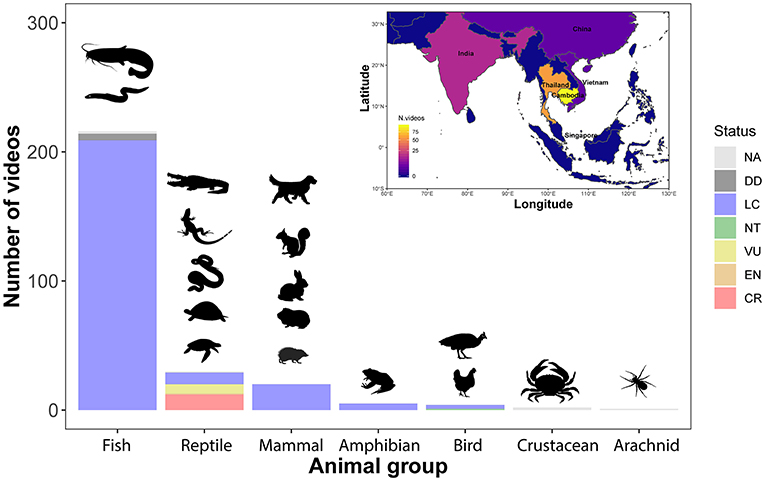

In the 206 examined videos, the number of target species increased with time (Supplementary Figure S2), totaling 31 (Supplementary Table S1). These animal species included mostly fish (71.4%), but also reptiles (13.1%), mammals (9.7%), amphibians (frogs; 2.4%), birds (1.5%), crustaceans (1.0%), and arachnids (0.5%). Worryingly, some of the target species, particularly reptiles, were of conservation concern (Figure 3; Supplementary Figure S3). For instance, the Chinese softshell turtle (Pelodiscus sinensis) is listed as Vulnerable, the elongated tortoise (Indotestudo elongate) and the endemic Siamese crocodile (Crocodylus siamensis) listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Redlist. Reptiles have one of the lowest levels of protection in the region (only ~14% of their ranges are within protected areas) (Hughes, 2017). From a conservation point of view, there is a concern that the video creators do not have the taxonomic knowledge to determine which species is of conservation concern nor necessarily the will to adjust their activities, were they to know this information. Together with the increase in the number of target species for HFE, Southeast Asian fauna is facing a new threat that disturbs natural populations in the wild. Although the impact of HFE on the population dynamics and ecosystem functioning is unknown, the potential of the geographic spread of this trend to other countries expands the ecological risks to the global level.

Figure 3. Animal groups targeted in the hunting–fishing–experiments with their IUCN red list status. NA, not available; DD, data deficient; LC, least concern; NT, near threatened; VU, vulnerable; EN, endangered; CR, critically endangered. Top-right map shows the number of videos for each country.

Material and Techniques of HFE

The material used in HFE is ethically questionable and environmentally harmful. It involved using (1) edible products such as soda, eggs, and mint candies; (2) chemical products such as detergents, toothpaste and chemical rocks; and (3) animals as live baits such as duckling, turtles and lizards (Supplementary Figure S4). Most of these products have toxic effects on the aquatic and soil organisms (Supplementary Table S2), and could affect both target and non-target species (Mousavi and Khodadoost, 2019). In our analyzed videos, the number of materials used in HFE increased with time (Supplementary Figure S1), suggesting an intent to innovate in HFE through the diversification of material. For instance, the catfish lay hundreds of eggs which are very sensitive to chemical pollution (Esenowo and Ugwumba, 2010; Ogundiran et al., 2010). In addition, extensive use of chemical HFE might affect non-target species and alter the functioning of the ecosystem (Bardach et al., 1965). Products such as detergents have the potential to increase the phosphorus level in the water and cause eutrophication (Kundu et al., 2015). There could also be some indirect impacts on non-target animals that exploit the polluted habitats. For example, many terrestrial animals use aquatic habitats as a source of drinking water. Also, since the burrowing animals are often the target of HFE, the polluted holes could be a potential nest (e.g., turtles) or a shelter for various non-borrowing animals (e.g., fox, mink, snake) (Lips, 1991; Galán and Light, 2017; Old et al., 2018). Furthermore, using live vertebrates such as turtles and lizards as baits to catch other animals is also problematic and unethical. Therefore, the potential environmental impacts of the products used in HFE is substantial.

HFE Removal on YouTube

All 206 videos seem to be against the guidelines of YouTube for animal abuse. Of the 206 videos, only 64 (31%) videos were no longer available after 7 months of our initial assessment, which shows that the videos remained accessible to viewers for an average ± SD duration of 236.9 ± 52.8 days (179–427 days, N = 142) since the uploading time. This suggests that the YouTube algorithm was unable to detect, flag, and remove the videos, highlighting some practical limitations in the attempt to control this phenomenon (Gorwa et al., 2020).

Real or Fake?

While it is not clear whether the HFE videos are real or staged, we still do not know how many trials have been made to create the video, and thus it unclear how intense is the collateral damage on species (potentially individuals sacrificed) and the environment (the number of habitats destroyed before finding the target animals). Even in the best-case scenario where the specimens used in the fishing and hunting experiment were returned to their original sites and no survival cost was inflicted on the individual, the message that the videos convey is still highly detrimental given the high outreach potential of YouTube. The same experiment could be repeated by people who watch the video because no disclaimer is displayed in the original videos.

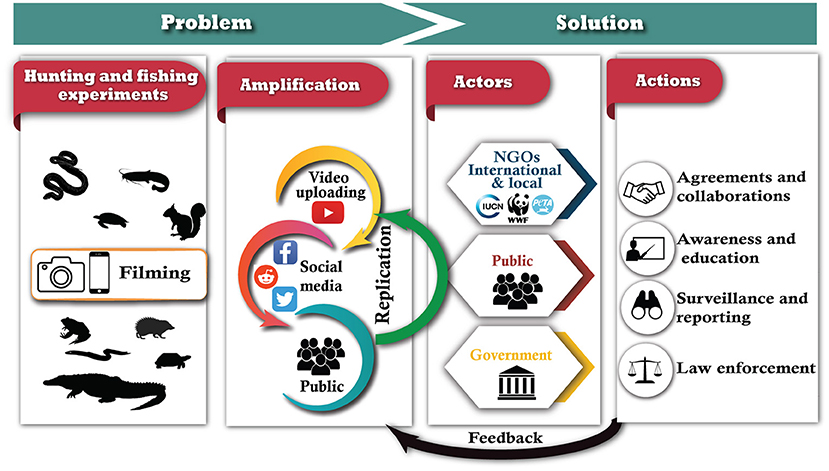

Recommendations for the Management of HFE

Effective management of invasive and unethical hunting and fishing methods requires the participation and collaboration of different actors, including non-governmental organizations, governments, private sector, and the public. Such a combined effort is crucial in an era of a rapidly evolving Internet sphere with unprecedented public outreach potential, particularly because those new animal exploitations for virtual entertainment might not be on the radar of conservation organizations. Here, we present some recommendations that might serve as a basis for policy makers to develop effective conservation plans that offset the potential impact of this new emerging trend as well as other virtual threats that might arise in the future (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Diagram presenting potential measures that should be taken by different actors to solve the problem of hunting and fishing experiments (HFE) on the internet. Combined efforts from international and national non-governmental organizations (NGOs), governments, business companies, and the public are needed to establish and apply measures that target the online platforms that spread HFE and demotivate the public from engaging in this kind of environmentally-damaging activity.

Wildlife conservation organizations (e.g., The Nature Conservancy, The World Wildlife Fund, International Union for Conservation of Nature), animal rights organizations (e.g., People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) and governments should (1) create environmental education campaigns and programs to raise the awareness of the public about the risks and consequences of species over-exploitation (Ploeg et al., 2011), (2) mobilize the public and supporters of wildlife and animal rights organizations using social media to coordinate massive reporting of online wildlife exploitation to the hosting platform, (3) enter in discussions with the chief executive officer and key executives of YouTube to establish a long-term strategic plan that limits the spread of animal ill-treatment, and (4) raise the awareness of companies who use YouTube for advertisement about the questionable wildlife videos to which their brand is sometimes attached to.

Another important actor that has a long experience with wildlife trade is CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora). While CITES targets the physical movement of species through trades, the Internet offers nowadays means to profit from wildlife exploitation without the associated difficulties of trading across borders. CITES should broaden their oversight and include species exploitation for online entertainment as a new emergent threat (Phelps et al., 2010; Jensen et al., 2019; Wong et al., 2020). CITES should include this new online threat in its framework, and the different parties (signatory countries) should implement and enforce it in their national legislation.

YouTube should stop the monetization of these videos because it will likely demotivate people from producing and promoting HFE on the Internet, and thus stop the supply of the videos for a worldwide audience. YouTube should also improve its ability to detect and remove the videos in a timely manner by upgrading the existing algorithms which identify and block wildlife exploitation content when it is uploaded. While targeting the host of the videos is crucial, it is also imperative to limit the role of social media in spreading HFE content on the Internet. Major social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) should also improve their means of flagging the videos when they are shared and restricting their spread. For example, Instagram has introduced a warning system to protect users from viewing certain content. eBay (one of the world's largest online marketplaces) has also strengthened its policy on deleting adverts of illegal wildlife trade.

Although establishing a system of law enforcement is key to combat this trend in the wild and on the Internet (i.e., actions on the supply side), it is also crucial to tackle the demand side by raising awareness of the YouTube audience about the potential impacts of HFE on biodiversity and animal welfare (Thomas-Walters et al., 2020). These conservation initiatives often require adequate human resources and funding, which is sometimes challenging for poor countries such as those in Southeast Asia (Lee et al., 2005; Lasco et al., 2010; Von Rintelen et al., 2017). This is why mobilizing public support through online crowdfunding is a critical step. Such an endeavor might be carried out through a collaboration between wildlife organizations and online influencers who regularly use YouTube and social media. Some of the influencers with large public following and outreach have shown active environmental engagement. For example, in late 2019 a single influencer raised $20 million for climate change mitigation through a crowdfunding tree plantation campaign (1$/tree; teamtree.org). More recently, a similar initiative called #teamseas aims at removing 30 million pounds of trash by January 1st, 2022 (1$/pound of trash out of the ocean; https://teamseas.org/). Such an union between conservationists and online influencers might be an efficient long-term solution for countering the propagation of environmentally-damaging content, promotion of environmental education, and advocacy for biodiversity conservation and sustainability to the general public.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting this study are available on GitHub https://github.com/rassimkhelifa/rassimkhelifa-Data_Khelifa_FrontiersInConsSci.

Author Contributions

RK: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, project administration, visualization, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. MM and NH: data curation and investigation. HM: data curation, investigation, and visualization. CK: conceptualization and writing—review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

RK is funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (P400PB_191139).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the persons for helping in identifying the species. Thanks to Alejandra Echeverri for helpful discussions and comments.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2021.788269/full#supplementary-material

References

Alexa Internet (2020). Alexa: Keyword Research, Competitor Analysis, and Website Ranking. Available online at: https://www.alexa.com (accessed Jan 07, 2020).

Arneth, A., Shin, Y.-J., Leadley, P., Rondinini, C., Bukvareva, E., Kolb, M., et al. (2020). Post-2020 biodiversity targets need to embrace climate change. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 30882–30891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009584117

Bardach, J. E., Fujiya, M., and Holl, A. (1965). Detergents: effects on the chemical senses of the fish Ictalurus natalis (le Sueur). Science 148, 1605–1607. doi: 10.1126/science.148.3677.1605

Bennett, N. J., Roth, R., Klain, S. C., Chan, K., Christie, P., Clark, D. A., et al. (2017). Conservation social science: understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. Biol. Conserv. 205, 93–108. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.10.006

Bogoni, J. A., Peres, C. A., and Ferraz, K. M. P. M.B. (2020). Effects of mammal defaunation on natural ecosystem services and human well being throughout the entire Neotropical realm. Ecosyst. Serv. 45:101173. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2020.101173

Burgess, J., and Green, J. (2018). YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

El Bizri, H. R., Morcatty, T. Q., Lima, J. J., and Valsecchi, J. (2015). The thrill of the chase: uncovering illegal sport hunting in Brazil through YouTube™ posts. Ecol. Soc. 20, 1–30. doi: 10.5751/ES-07882-200330

Esenowo, I., and Ugwumba, O. (2010). Growth response of catfish (Clarias gariepinus) exposed to water soluble fraction of detergent and diesel oil. Environ. Res. J. 4, 298–301. doi: 10.3923/erj.2010.298.301

Galán, A. P., and Light, J. E. (2017). Reptiles and amphibians associated with texas pocket gopher (Geomys personatus) burrow systems across the texas sand sheet. Herpetol. Rev. 48, 517–521.

Gorwa, R., Binns, R., and Katzenbach, C. (2020). Algorithmic content moderation: technical and political challenges in the automation of platform governance. Big Data Soc. 7:2053951719897945. doi: 10.1177/2053951719897945

Hughes, A. (2017). Mapping priorities for conservation in Southeast Asia. Biol. Conserv. 209, 395–405. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2017.03.007

Jensen, T. J., Auliya, M., Burgess, N. D., Aust, P. W., Pertoldi, C., and Strand, J. (2019). Exploring the international trade in African snakes not listed on CITES: highlighting the role of the internet and social media. Biodivers. Conserv. 28, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10531-018-1632-9

Johnson, C. N., Balmford, A., Brook, B. W., Buettel, J. C., Galetti, M., Guangchun, L., et al. (2017). Biodiversity losses and conservation responses in the Anthropocene. Science 356, 270–275. doi: 10.1126/science.aam9317

Khelifa, R., Zebsa, R., Amari, H., Mellal, M. K., Bensouilah, S., Laouar, A., et al. (2017). Unravelling the drastic range retraction of an emblematic songbird of North Africa: potential threats to Afro-Palearctic migratory birds. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01103-w

Kundu, S., Coumar, M. V., Rajendiran, S., Rao, A., and Rao, A. S. (2015). Phosphates from detergents and eutrophication of surface water ecosystem in India. Curr. Sci. 108, 1320–1325. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24905495

Lasco, R. D., Uebelhör, K., and Follisco Jr, F. (2010). Facing the challenge of biodiversity conservation and climate change in Southeast Asia. Clim. Dev. 2, 291–294. doi: 10.3763/cdev.2010.0043

Lee, R. J., Gorog, A. J., Dwiyahreni, A., Siwu, S., Riley, J., Alexander, H., et al. (2005). Wildlife trade and implications for law enforcement in Indonesia: a case study from North Sulawesi. Biol. Conserv. 123, 477–488. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2005.01.009

Lenzi, C., Speiran, S., and Grasso, C. (2020). “Let Me Take a Selfie”: implications of social media for public perceptions of wild animals. Soc. Anim. 1, 1–20. doi: 10.1163/15685306-BJA10023

Lips, K. R. (1991). Vertebrates associated with tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) burrows in four habitats in south-central Florida. J. Herpetol. 25, 477–481. doi: 10.2307/1564772

Mclean, H. E., Jaebker, L. M., Anderson, A. M., Teel, T. L., Bright, A. D., Shwiff, S. A., et al. (2021). Social media as a window into human-wildlife interactions and zoonotic disease risk: an examination of wild pig hunting videos on YouTube. Hum. Dimen. Wildlife 2021, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/10871209.2021.1950240

Mousavi, S. A., and Khodadoost, F. (2019). Effects of detergents on natural ecosystems and wastewater treatment processes: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 26439–26448. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05802-x

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., Da Fonseca, G. A., and Kent, J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858. doi: 10.1038/35002501

Ogundiran, M., Fawole, O., Adewoye, S., and Ayandiran, T. (2010). Toxicological impact of detergent effluent on juvenile of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) (Buchell 1822). Agric. Biol. J. North Am. 1, 330–342. doi: 10.5251/abjna.2010.1.3.330.342

Old, J. M., Hunter, N. E., and Wolfenden, J. (2018). Who utilises bare-nosed wombat burrows? Aust. Zool. 39, 409–413. doi: 10.7882/AZ.2018.006

Pagel, C. D., Orams, M., and Lück, M. (2020). # BiteMe: considering the potential influence of social media on in-water encounters with marine wildlife. Tour. Mar. Environ. 15, 249–258. doi: 10.3727/154427320X15754936027058

Pantti, M. (2015). Grassroots humanitarianism on YouTube: ordinary fundraisers, unlikely donors, and global solidarity. Int. Commun. Gazette 77, 622–636. doi: 10.1177/1748048515601556

Peres, C. A., Emilio, T., Schietti, J., Desmoulière, S. J., and Levi, T. (2016). Dispersal limitation induces long-term biomass collapse in overhunted Amazonian forests. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 113, 892–897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516525113

Phelps, J., Webb, E. L., Bickford, D., Nijman, V., and Sodhi, N. S. (2010). Boosting cites. Science 330, 1752–1753. doi: 10.1126/science.1195558

Ploeg, J., Cauilan-Cureg, M., Weerd, M. V., and De Groot, W. (2011). Assessing the effectiveness of environmental education: mobilizing public support for Philippine crocodile conservation. Conserv. Lett. 4, 313–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2011.00181.x

Sajeva, M., Augugliaro, C., Smith, M. J., and Oddo, E. (2013). Regulating internet trade in CITES species. Conserv. Biol. 27, 429–430. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12019

Siddiqui, A. (2021). Viral videos and their impact on society. J. Socio-Econ. Relig. Stud. 1, 01–10. doi: 10.52337/jsers.v1i2.25

Statista (2021). YouTube—Statistics and Facts. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/topics/2019/youtube/#dossierKeyfigures Published by L. Ceci, July 12, 2021 (accessed November 11, 2021).

Sung, Y.-H., and Fong, J. J. (2018). Assessing consumer trends and illegal activity by monitoring the online wildlife trade. Biol. Conserv. 227, 219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2018.09.025

Thomas-Walters, L., Veríssimo, D., Gadsby, E., Roberts, D., and Smith, R. J. (2020). Taking a more nuanced look at behavior change for demand reduction in the illegal wildlife trade. Conserv. Sci. Practice 2:e248. doi: 10.1111/csp2.248

Tickner, D., Opperman, J. J., Abell, R., Acreman, M., Arthington, A. H., Bunn, S. E., et al. (2020). Bending the curve of global freshwater biodiversity loss: an emergency recovery plan. Bioscience 70, 330–342. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biaa002

Van Hamme, G., Svensson, M. S., Morcatty, T. Q., Nekaris, K. I., and Nijman, V. (2021). Keep your distance: using Instagram posts to evaluate the risk of anthroponotic disease transmission in gorilla ecotourism. People Nat. 3, 325–334. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10187

Van Looy, A. (2016). “Online advertising and viral campaigns,” in Social Media Management (Berlin: Springer), 63–85. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-21990-5_4

Van Roon, A., Maas, M., Toale, D., Tafro, N., and Van Der Giessen, J. (2019). Live exotic animals legally and illegally imported via the main Dutch airport and considerations for public health. PLoS ONE 14:e0220122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220122

Von Rintelen, K., Arida, E., and Häuser, C. (2017). A review of biodiversity-related issues and challenges in megadiverse Indonesia and other Southeast Asian countries. Res. Ideas Outcomes 3:e20860. doi: 10.3897/rio.3.e20860

Vu, H. T., Blomberg, M., Seo, H., Liu, Y., Shayesteh, F., and Do, H. V. (2021). Social media and environmental activism: framing climate change on Facebook by global NGOs. Sci. Commun. 43, 91–115. doi: 10.1177/1075547020971644

Wong, R. W., Lee, C. Y., Cheung, H., Lam, J. Y., and Tang, C. (2020). A case study of the online trade of CITES-listed Chelonians in Hong Kong. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 19, 95–100. doi: 10.2744/CCB-1344.1

Xiao, L., Lu, Z., Li, X., Zhao, X., and Li, B. V. (2021). Why do we need a wildlife consumption ban in China? Curr. Biol. 31, R168–R172. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.12.036

Xu, Q., Cai, M., and Mackey, T. K. (2020). The illegal wildlife digital market: an analysis of Chinese wildlife marketing and sale on Facebook. Environ. Conserv. 47, 206–212. doi: 10.1017/S0376892920000235

YouTube (2021). YouTube policies: Violent or graphic content policies. YouTube Help. Available online at: https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2802008?hl=en (accessed November 09, 2021).

Zhang, L., and Yin, F. (2014). Wildlife consumption and conservation awareness in China: a long way to go. Biodivers. Conserv. 23, 2371–2381. doi: 10.1007/s10531-014-0708-4

Keywords: animal cruelty, animal ethics, animal welfare, hunting, internet, wildlife, YouTube

Citation: Khelifa R, Mellal MK, Mahdjoub H, Hasanah N and Kremen C (2022) Biodiversity Exploitation for Online Entertainment. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2:788269. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2021.788269

Received: 01 October 2021; Accepted: 21 December 2021;

Published: 24 January 2022.

Edited by:

Anthony J. Giordano, Society for the Preservation of Endangered Carnivores and their International Ecological Study (SPECIES), United StatesReviewed by:

K. Anne-Isola Nekaris, Oxford Brookes University, United KingdomBogdan Cristescu, Cheetah Conservation Fund, Namibia

Copyright © 2022 Khelifa, Mellal, Mahdjoub, Hasanah and Kremen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rassim Khelifa, cmFzc2lta2hlbGlmYUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Rassim Khelifa

Rassim Khelifa Mohammed Khalil Mellal

Mohammed Khalil Mellal Hayat Mahdjoub

Hayat Mahdjoub Nur Hasanah5

Nur Hasanah5 Claire Kremen

Claire Kremen