- 1Department of Biology, Canadian Centre for Evidence-Based Conservation, Institute of Environmental and Interdisciplinary Science, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 2School of Sociological and Anthropological Studies, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 3Institute of Environmental and Interdisciplinary Science, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 4School of Public Policy and Administration, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 5Canadian Wildlife Federation, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 6Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, Canmore, AB, Canada

- 7Parks Canada, Gatineau, QC, Canada

- 8Wildlife Research Division, Environment and Climate Change Canada, National Wildlife Research Centre, Ottawa, ON, Canada

- 9Great Lakes Laboratory for Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, and Oceans Canada, Sault Ste. Marie, ON, Canada

- 10Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Government of Canada, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Successful incorporation of scientific knowledge into environmental policy and decisions is a significant challenge. Although studies on how to bridge the knowledge-action gap have proliferated over the last decade, few have investigated the roles, responsibilities, and opportunities for funding bodies to meet this challenge. In this study we present a set of criteria gleaned from interviews with experts across Canada that can be used by funding bodies to evaluate the potential for proposed research to produce actionable knowledge for environmental policy and practice. We also provide recommendations for how funding bodies can design funding calls and foster the skills required to bridge the knowledge-action gap. We interviewed 84 individuals with extensive experience as knowledge users at the science-policy interface who work for environmentally-focused federal and provincial/territorial government bodies and non-governmental organizations. Respondents were asked to describe elements of research proposals that indicate that the resulting research is likely to be useful in a policy context, and what advice they would give to funding bodies to increase the potential impact of sponsored research. Twenty-five individuals also completed a closed-ended survey that followed up on these questions. Research proposals that demonstrated (1) a team with diverse expertise and experience in co-production, (2) a flexible research plan that aligns timelines and spatial scale with policy needs, (3) a clear and demonstrable link to a policy issue, and (4) a detailed and diverse knowledge exchange plan for reaching relevant stakeholders were seen as more promising for producing actionable knowledge. Suggested changes to funding models to enhance utility of funded research included (1) using diverse expertise to adjudicate awards, (2) supporting co-production and interdisciplinary research through longer grant durations and integrated reward structures, and (3) following-up on and rewarding knowledge exchange by conducting impact evaluation. The set of recommendations presented here can guide both funding agencies and research teams who wish to change how applied environmental science is conducted and improve its connection to policy and practice.

Introduction

The last decade has seen a steady stream of scholarship dedicated to understanding and narrowing the knowledge-action gap by, among other strategies, improving knowledge mobilization and exchange among scientists and decision makers (Box 1; Cvitanovic et al., 2016; Nguyen et al., 2017). In environmental fields, much of the literature has focused on the responsibilities of scientists to modify their research approach, improve their communication skills, and amplify their awareness of policy issues (Bednarek et al., 2016; Safford and Brown, 2019); or else on decision makers to engage more effectively with the scientific community and rely less on informal knowledge sources (Pullin et al., 2004; Cvitanovic et al., 2014). Far less attention has been directed toward the roles, responsibilities, and opportunities for funding agencies to solicit, encourage, and support research that is likely to promote evidence-informed decision-making (Matso and Becker, 2014; Arnott et al., 2020a). Here, we present a set of criteria gleaned from interviews with knowledge users working at the science-policy interface across Canada that can be used by funding agencies (Canadian or otherwise) to evaluate research proposals for their potential to produce actionable knowledge for environmental policy (Box 1).

Box 1. Definition of key terms as used in this manuscript.

Actionable knowledge: Scientific products (data, tools, findings, manuscripts) that are useful for informing environmental policy and action outside of a strictly scientific research context [adapted from Arnott (2019)].

Environmental policy: The ways in which legislation (the Act) and regulations (complementary law) related to the environment and use of natural resources are actioned (enforced) by the federal, provincial, or territorial governments.

Evidence-informed decision-making: When high quality research evidence is transparently, consistently, and accurately used to inform decisions for environmental policy and practice.

Knowledge-action gap: The barriers experienced by both scientists and knowledge users in mobilizing conservation action, practice, or policy based on scientific evidence [adapted from Nguyen et al. (2017)].

Knowledge co-production: Research conducted using an “iterative and collaborative process whereby diverse expertise, knowledge and actors are engaged in producing context-specific knowledge and pathways toward a sustainable future” [adapted from Norström et al. (2020)].

Knowledge exchange: The social dimensions of knowledge creation, diffusion, and application, and the process and mechanisms of knowledge movement across networks of knowledge producers and users [adapted from Nguyen et al. (2017)].

Policy practitioners/advisors: Individuals with expertise in advising environmental policy, and/or those with first-hand knowledge of the type of scientific information needed to aid in decision making. Generally, policy practitioners/advisors would be “knowledge users” (i.e., stakeholders, government officials, practitioners) as opposed to “knowledge generators” (i.e., scientists).

Policy windows: windows of opportunity for policy change that periodically create situations for the sudden uptake of knowledge [adapted from Kingdon (1984)].

Practice: how knowledge is applied on the ground, in the field, or in other practical situations

Funding agencies play a unique role within the scientific community. They have substantial influence on the direction of and intention behind funding calls, and on the evaluation of proposals and decisions on funding allocation (Lyall et al., 2013; Coutinho and Young, 2016). In turn, funding decisions shape research programs (Smits and Denis, 2014), particularly in relatively young and/or interdisciplinary fields that lack dedicated funding bodies (Lyall et al., 2013). Research funders thus have capacity to encourage and influence practices that can bridge the gap between science and environmental policy and practice (Bozeman and Youtie, 2017; Mach et al., 2020). A small (but growing) body of evidence has documented how innovative funding models can stimulate approaches to research that are known to amplify its impact (Bednarek et al., 2016; Boaz et al., 2018; Trueblood et al., 2019). Research in the medical field has identified funding agencies as key players in the process of integrating science into policy and practice (Holmes et al., 2012) with several funders deliberately promoting interdisciplinary engagement and incorporating follow-up programs to improve knowledge exchange (Sibbald et al., 2014).

In an applied conservation setting, research often has the stated goal of understanding and solving environmental problems. However, the extent to which this research is mobilized to inform policy and practice is much lower than would be ideal (Sutherland and Wordley, 2017). Although much work has been done to identify barriers to effective knowledge exchange (Rose et al., 2018), suggested solutions are often difficult to implement (Rose et al., 2019), and support is needed from all players in the research arena. Funding bodies have a responsibility to ensure that the work they support has a high probability of being integrated into policy and practice if that is the stated goal of the research or the funding call (Fisher et al., 2001). However, predicting which proposals have the highest likelihood of producing actionable knowledge can be a daunting task for grant selection committees. Being able to foresee which research projects are likely to produce useable knowledge before the research is underway can prevent waste of important research resources (Buxton et al., 2021). However, most of the nascent research in this sphere has focused on evaluating study utility after the research has been conducted by monitoring the policy and practice impact in the months or years following publication (Bozeman and Youtie, 2017). We are unaware of studies that have investigated steps that can be taken during the grant selection stage based on insights obtained from knowledge users.

The goals of this study are therefore to (1) provide a set of general criteria that can be used by funding agencies to determine whether a given proposal is likely to produce actionable knowledge and (2) provide recommendations on operational aspects of funding agencies that promote production of actionable knowledge. We used semi-structured interviews to elicit the perspectives of individuals with extensive experience as knowledge users at the science-policy interface on how funding agencies can solicit and select research proposals that are likely to be useful for policy and practice. We draw lessons and recommendations from these findings to assist funding agencies in identifying and supporting actionable research.

Methods

Selection of Participants

Participants for this study were recruited via directed sampling due to the specialized nature of the knowledge we sought to access. We selected participants who were currently employed or recently retired from senior-level positions (e.g., senior science advisors, program directors) in environmental departments in Canadian federal, territorial, or provincial governments, and those working for environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGO) with an interest in environmental policy. We selected these organizations (through consultations with representatives from each sector) because they are actively involved in advising and/or writing policy. We targeted senior-level participants because of their experience using applied research to advise or inform environmental policy. Some of our participants also have experience on grant selection committees and as recipients of grants and are thus familiar with the process of applying for, adjudicating, and taking up grants. Although we were primarily interested in participants' perspectives as knowledge users, this diversity of experience situates them well to provide advice on judging or predicting research utility at the proposal stage. It is because of this wide range of experience that we focused on individuals who hold senior positions within their organization. However, our selection of participants also represents limitations to this study. First, simply having experience in senior roles at the science-policy interface does not guarantee success at producing actionable knowledge. Given the lack of reporting or tracking of knowledge or evidence uptake we have no indication of the success rates of the participants in this study. Second, we assumed that most on-the-ground environmental managers or practitioners are focused on a given region or issue and are not typically involved with development of strategic funding programs. We thus did not interview individuals holding managerial or practitioner-level positions. However, by not including the voices of this group we are likely to be overlooking valuable perspectives and encourage future studies to focus on that demographic.

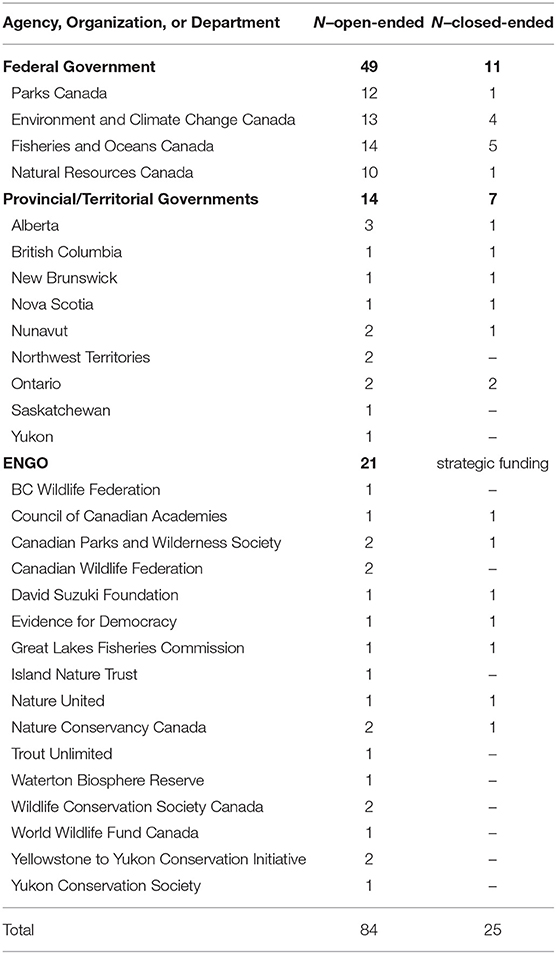

Participants were selected through prior knowledge and past partnerships (n = 53), and by performing web searches of selected organizations to identify individuals in leadership or advisory roles (n = 23). Additional participants were identified through recommendations from people on this initial list (n = 8). Invitations were distributed to potential participants by email. A total of 135 people were contacted. Of these, 84 were interviewed over 82 sessions, with two interviews having two participants. The participants all had post-secondary education with the majority (75%) holding an Master's or a PhD in a scientific field. Participants had experience either primarily in policy (n = 8), primarily in scientific research (n = 9), or in both (n = 67), with the majority (80%) gaining policy experience on-the-job rather than through formal training. Of participants working for a federal department, 30 were based out of headquarters in Canada's capital city of Ottawa, and 19 were attached to regional offices in various provinces. Participants included 36 female and 48 male respondents and included both early, mid, and later-career individuals encompassing a range from 8 to 30+ years experience. We had representation from federal government bodies [including Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), Parks Canada, and Natural Resources Canada (NRCan)], territorial/provincial governments, and ENGOs. Sample sizes of participants and their organizations are presented in Table 1. This study was conducted with Canadian professionals; however, these findings might also apply to other regions that have highly developed research and funding systems (e.g., Europe, Australia, South Africa, the United States).

Table 1. Numbers of participants from the federal government (Parks Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and Natural Resources Canada), provincial/territorial governments, and environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) that responded to the open-ended and closed-ended questions.

Designing and Conducting Interviews

Interviews were semi-structured, following a set of scripted questions but allowing for digressions. They were a mix of closed-ended and open-ended questions, thus generating quantitative and qualitative responses. The interview guide was written collaboratively by several members of the research team (EAN, JJT, TR, JFL, NY, JB, SJC), and was circulated to all 17 co-authors for comment. The interview questionnaire was extensively revised over a 3-month period. Prior to finalization, the interview was tested on six individuals: three non-participants and three participants in the study. Based on their feedback, several questions were removed or revised.

The full interview questionnaire comprised 14 questions that, in addition to funders' roles, covered definitions of evidence and actionable knowledge, barrier, and solutions to using evidence in policy and practice, and experiences with co-production. In this article, we report findings from two key questions that asked participants about elements of research proposals that indicate a high likelihood that the proposed research will be useful in a policy context. First, we asked an open-ended question that requested participants to describe characteristics of grant proposals that indicate that the research is likely to be actionable based on definitions of usable knowledge discussed earlier in the questionnaire (see Box 1). The respondents were then prompted for further advice on how funding agencies can support the production of actionable knowledge. Questions were phrased such that we did not guide participants' answers; however, the question about experiences with co-production was asked before the question on advice to funders, so there is the possibility of bias towards answers relating to co-production. Second, we asked a closed-ended question whereby participants were presented with a list of 33 study characteristics that our team had determined might be important based on our collective experience as researchers and knowledge users and on literature review from both medical and environmental fields (e.g., Holmes et al., 2012; Matso and Becker, 2014; Arnott et al., 2020a,b). Respondents were asked to check boxes next to this list, first selecting all items they deemed to enhance utility (“all that apply”), and second narrowing down their selection to the top three choices. This list included options for “other” where participants could add an option, and “unsure” if they could not answer the question. Participants received one of three different versions of this list with characteristics presented in different orders to prevent selection bias. The different versions were offered to participants at random. Due to time constraints during some of the interviews, only ~30% of all respondents (n = 25) were able to complete the closed-ended portion of the interview; however, all sectors were still represented (Table 1). We chose to focus only on these two questions for this study because these two questions led to a cohesive and impactful story. The questions used in this study are presented in Appendix A.

Interviews were conducted in person or via telephone by JFL. For the in-person interviews, the closed-ended question was printed and filled out by hand by the participant. For the telephone interviews, it was emailed in a spreadsheet and participants were instructed to open the tab only when it was time to respond. Interviews were ~1 h in length (average: 1 h 5 min; range: 44 min−1 h 35 min). All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed in full using Trint Automated Transcription software, and error checked by one of three transcribers to ensure accuracy. Consent to participate in the study was obtained from all interviewees prior to the interview, and all personal information was kept strictly confidential per Carleton University Research Ethics Board file #12486.

Data Analysis

Qualitative analyses were conducted on responses to the open-ended question using NVivo software (version 12). An initial codebook was developed through a combination of inductive and deductive processes by EAN and NH. Coders conducted two inter-rater reliability tests on the first round of raw coding to ensure consistency. The first test resulted in an average Cohen's K-value of 0.37 indicating low agreement. Coders thus conducted four meetings over two months to manually compare and discuss coding choices, and a second test resulted in an average K-value of 0.52 indicating fair agreement. The final two rounds of coding were completed by EAN after the final detailed codes were determined through further discussion among the author team. The final codebook is available in Appendix B. Interviews were coded under two central themes including: (1) characteristics of proposals leading to actionable research, and (2) advice on operational changes for funding agencies (Appendix B).

Quantitative analyses were conducted on responses to the closed-ended question. We tested whether the list order of characteristics in the three different versions of the closed-ended question affected participants' selections by comparing binary responses among the three groups using Kruskal-Wallis tests and Holm's sequential Bonferroni procedure to adjust alpha levels for multiple testing. We conducted a frequency analysis to assess trends in participants' responses to the “check all that apply” and “top three” survey questions, and compared responses among sectors (federal, provincial/territorial, and ENGO). To conduct the frequency analysis, we aggregated the 33 characteristics into 18 categories of closely related characteristics, based on our judgement (Appendix A). These groupings were formed to make the number of characteristics more manageable for analysis and graphical presentation.

Results and Discussion

Elements of Proposals That Indicate Potential for Actionable Research (Theme 1)

Open-Ended Questions: Characteristics of Successful Proposals

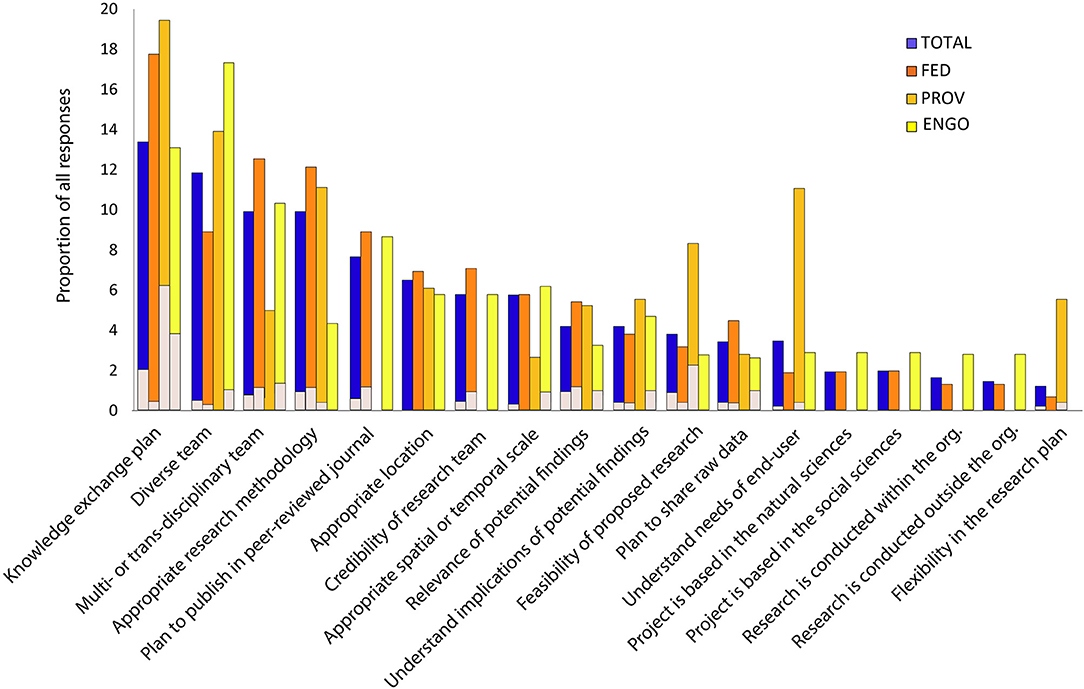

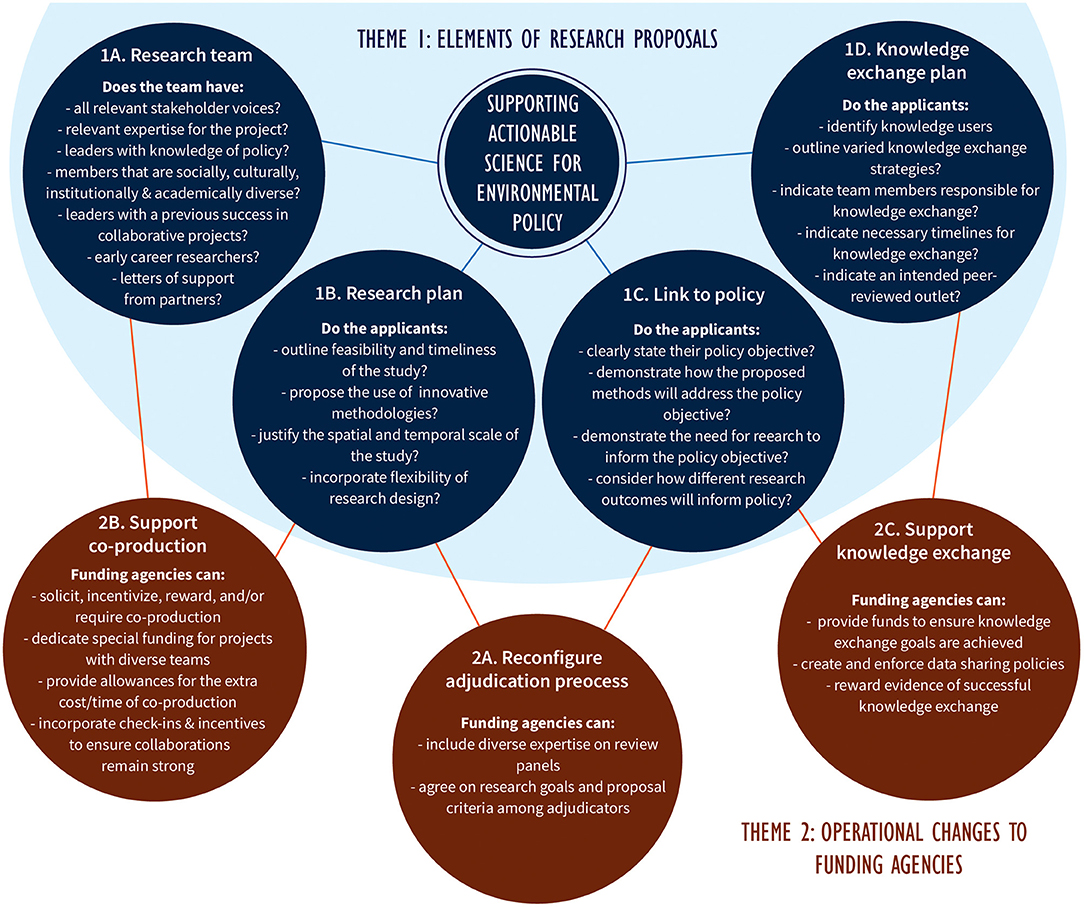

Participants' responses about proposal characteristics that are indicators of actionable research were grouped into four topics. These included having: (1A) a research team with diverse perspectives and appropriate expertise, (1B) a research plan that is comprehensive, feasible, and flexible, (1C) a clear and demonstrable link to policy, and (1D) a plan for knowledge exchange with diverse audiences. In the following text, suggestions emerging directly from participants' responses are underlined. Mechanisms to achieve the various recommendations, support from the literature, and potential challenges are considered alongside each suggestion. Connections among themes and responses are illustrated in Figure 2 and summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Key recommendations gleaned from open-ended questions for ensuring that funded research is effective for informing policy in environmental fields.

1A. Research Team Comprises Diverse Perspectives and Expertise Appropriate to the Problem at Hand

According to participants in this study, the most important element of a proposal that is predictive of useful research outputs is the composition of the research team. Specifically, it was emphasized that proposals should indicate that a policy practitioner and/or advisor will be at the table to guide the program at all stages of the research process (Box 1). There was likewise strong support for assembling a team with a high level of diversity and expertise in relevant areas. Participants suggested that diverse research teams (i.e., teams that include voices from various cultures, experiences, and areas of expertise) increase the likelihood that multiple perspectives and knowledge sources will be considered at all stages of the research process (Figure 2). These points are summarized by a retired federal employee with extensive transdisciplinary and policy experience: “[Review panels] must look for a team made of people who are individually expert in the diverse range of things. Especially for a policy question with broad scope. You will want a team where you have an expert in each of the major perspectives” [male, federal (ON)]. To that end, teams should include government and academic scientists, and relevant representatives from Indigenous groups, resource users, and practitioners with individual areas of expertise and potential contributions stated clearly in the proposal.

Having a research team with diverse perspectives and expertise is crucial because the team provides the foundation for success in all aspects of the research (Figure 2). For example, having varied sectoral and cultural representation has been shown to facilitate knowledge exchange with end users (Howarth and Monasterolo, 2016), and having team members with in-depth knowledge of pertinent policy issues helps to keep policy-related information needs in focus (Cooke et al., 2020). Network maps can be used to identify groups (e.g., local resource users, practitioners, Indigenous groups) that are important to include on a research team, and to identify representatives from each group that are able and willing to participate in the research activities (Cooke et al., 2020). Networks maps could be integrated into proposals to demonstrate that the team has the right composition to effectively carry out the proposed research. Inter-sectoral and trans-disciplinary partnerships should ideally be formed by following rigorous models of co-production (Box 1; Beier et al., 2017, Norström et al., 2020) as a great deal of scholarship has indicated that co-production is effective for producing actionable knowledge (Karl et al., 2007; Nel et al., 2016; Posner et al., 2016) and driving research use (Fujitani et al., 2017; Nguyen et al., 2019; Mach et al., 2020).

Participants further recommended that members (especially leaders) of policy-oriented research teams should be able to demonstrate within the proposal that they have a track record of success in co-production and a commitment to continue to do so. Mechanisms suggested for predicting that co-production will occur included requiring letters of support or in-kind contributions from research partners at the proposal stage. Such letters can provide evidence that the knowledge end-users are invested in the findings of the proposed work (Figure 2). Requiring evidence of support from partners has been implemented by some funding agencies (e.g., Genome Canada) and other collaborative grants (e.g., NSERC Alliance). However, the frequency at which support letters at the application stage lead to lasting relationships among partners has not been formally quantified. Even though support letters can be useful to indicate the possibility of partnerships, it might be the case that requests for letters of support happen at the last minute (Cooke et al., 2020), and that when the time comes for the research to begin, the demanding schedules of partners or the lack of inclusion by the researchers prevents long-term engagement. Thus, participants in this study recommended that letters of support should be required for proposal evaluation only if there is a plan by the funding agency to follow-up on and support relationships among research partners (Figure 2, expanded in section Reconfigure the award adjudication processes).

Building diverse, interdisciplinary teams and garnering support from external partners can be challenging, particularly for researchers who are new to the science-policy sphere [e.g., early- or mid-career researchers (ECRs, MCRs)]. Such individuals often lack diverse networks of collaborators outside of academia and have not yet established track records of successful collaboration with Indigenous groups, policy advisors/practitioners, or other end-users (Chapman et al., 2015; Kelly et al., 2019). In addition, there are several barriers to working in complex teams that have been discussed at length in other studies [see Lemos et al. (2018), Oliver et al. (2019), Rose et al. (2019), Young et al. (2020)]. Internal changes to funding agencies that support and encourage co-production can lower such barriers (Figure 2, expanded in section Reconfigure the award adjudication processes), but mentoring of ECRs and MCRs by more experienced researchers and practitioners can facilitate relationship building and expand/maintain productive partnerships [see Haider et al. (2018) and Kelly et al. (2019) for further discussion]. Participants in this study suggested that it is essential to ensure that ECRs and MCRs are included on teams so that the next generation of researchers are prepared to move into collaborative spaces (Figure 2). Several studies have suggested that the capacity of leaders of diverse, interdisciplinary teams is of ultimate importance when considering the potential success of a project and should be given more weight than in conventional grant applications (Lyall and Meagher, 2012; Lyall et al., 2013; Smits and Denis, 2014).

1B. Research Plan That Is Comprehensive, Feasible, and Flexible

Participants in this study identified several elements of research plans that are uniquely important for proposals that intend to produce actionable knowledge. One of the most broadly supported characteristics was careful consideration of the feasibility and timeliness of the proposed project (Figure 2, Table 2). Participants suggested that applicants should be able to convince the reviewers that their team can produce the promised results in the necessary period. As one federal government employee suggested: “A big consideration is: Is the project doable? Do they actually have the skills to deliver? Do they have the gear to deliver? Do they have the relationships in place to deliver?” [female, federal (ON)], and another from the ENGO sector: “The time frame is important. Often people put so much in their proposals and it's like, this is not realistic in the time frame that is being proposed and in the time frame necessary for this decision” [female, ENGO (AB)]. Participants thus suggested that funding bodies look for evidence of whether teams have mapped achievable timelines and matched various team members to specific tasks based on their expertise (see section Research team comprises diverse perspectives and expertise appropriate to the problem at hand). Some studies have shown that such approaches can be effective in ensuring projects are finished successfully (Gevers et al., 2001; Henderson et al., 2016).

Some participants suggested the idea of having built-in contingency plans or flexibility in research design in case the project must be adjusted to accommodate sudden changes in the policy landscape. As articulated by a provincial/territorial government employee:

The more flexibility that you can build into proposals the better they can be. Often proposals from external sources are very focused, and in some cases that could be exactly what is needed. But in other cases, if suddenly that research or that product is not exactly what is expected or isn't fulfilling the research goal, there has to be flexibility to make adjustments [male, provincial (ON)].

Planning for flexibility is necessary to successful products (Meng et al., 2020). Time for mid-project evaluations (i.e., formative evaluation; McGowan et al., 2008) and contingency plans or alternative approaches should be in place from the outset. Formative evaluation recognizes that, while project trajectories can be well-planned, surprising challenges and opportunities may present themselves and require teams to adjust goals (McGowan et al., 2008). Conceptual maps with outlines for reaching a desired outcome and possible alternative routes could be required in applications for funds intended for policy-relevant projects (De Silva et al., 2014). Incorporating flexibility into a research program has been shown to promote successful collaboration and encourage cross-institutional and interdisciplinary learning (Beier et al., 2017) and can thus increase the likelihood that a given project will meet a policy information need.

1C. Clear and Demonstrable Link to Policy

Having a clear link to a relevant policy issue was suggested to be high priority for determining whether proposed research is likely to produce actionable knowledge. First, there should be a clearly stated policy objective and a demonstrated need for environmental research (based in the natural and/or social sciences) to inform that objective. Second, there should be evidence that the information produced by the study is likely to be appropriate for filling a given knowledge gap through endorsement by a policy expert (Figure 2). Each of these points was supported across sectors, but the following statement by a provincial/territorial government scientist summarized these points succinctly:

I think at the onset you would have to know, from the perspective of the policy makers, what are the knowledge gaps or information needs that people have identified? And then the experimental design and hypotheses would have to clearly show how the outcomes of that work are feeding into those knowledge gaps. I think that link needs to be made explicitly at the onset, and the proponents of the work need to demonstrate how they expect the outcomes of their work be exactly related to that process [male, provincial (AB)].

In addition, participants suggested that proposals should demonstrate careful consideration of how different outcomes will inform policy in one direction or the other. As stated by a federal employee: “The proponent of the project should first identify what decisions need to be made, and then think about how the decision would be influenced by the outcome of the project. Preferably, they would have identified: If the outcome is this, the decision should go this way and if the outcome is that, the decision should go a different way” [male, federal (ON)]. This requires a clear articulation of the policy need, but also a definitive statement on how the proposed methods will produce appropriate and conclusive data.

To fulfill the above recommendations, researchers require a clear vision of the policy landscape (Cook et al., 2014; Reed et al., 2014; Rose et al., 2017), hence the participants' suggestion to have a policy practitioner on the team (Figure 2, section Research team comprises diverse perspectives and expertise appropriate to the problem at hand). However, having a clear policy goal should not override the capacity to be adaptive and flexible on research goals, especially if novel or unexpected findings emerge (Figure 2, Research plan that is comprehensive, feasible, and flexible). Although scientific knowledge can shape policy if appropriate research findings are available during critical policy windows (Box 1; Rose et al., 2017) this is rarely the case, and there are several other routes by which scientific research with appropriate and flexible research plans can inform policy (Figure 2). There can be incremental improvement to existing policies by filling knowledge gaps, questioning or falsification of current policy approaches, or identification of new areas of environmental conservation that require policy action (Fiorino, 1995; Holmes and Clark, 2008). Leaving room for flexibility will allow findings to fit naturally within this range of options. Regardless of the situation, the research team must identify the knowledge gaps that would inform a particular policy. Furthermore, if policy relevance is a goal of the research, it is important that people with policy experience are included during the review process; funding agencies that include a diversity of experts on the adjudication panel can support these goals (Figure 2, expanded in section Reconfigure the award adjudication processes).

1D. Plan for Knowledge Exchange With Diverse Audiences

Participants suggested that appropriate plans for knowledge exchange should be outlined early in the research process. As suggested by a federal government employee: “I would say it has to have two pieces. On the front end there needs to be evidence that [research objectives] are responsive to the current policy landscape. And then on the back end there must be a mechanism to feed the information back to that policy community” [female, federal (ON)]. To achieve this, participants suggested that proposals must include a clear pathway for knowledge exchange with appropriate audiences. This includes knowing who the audience is (e.g., stakeholder groups), who the specific people are that require the information (e.g., an individual public servant), time limitations, and the best format and forum for knowledge dissemination. In general, planning to share diverse outputs such as presentations, policy briefs, videos, concept maps, data, and manuscripts was recommended by participants to facilitate this process (Figure 2).

Lack of knowledge exchange is often a critical barrier to bridging the science-policy divide (Cook et al., 2013; Cvitanovic et al., 2015). Knowledge exchange should start in the early stages of the research process (i.e., through co-production, Beier et al., 2017), and should include a detailed plan for information sharing both within and external to a team (Figure 2, section Clear and demonstrable link to policy). This can be evaluated in proposals by requesting detailed strategies for knowledge exchange from researchers including timelines and identification of individuals or external communication bodies (e.g., boundary organizations) that will be involved with knowledge exchange activities (Michaels, 2009; Shanley and López, 2009). Although this might necessitate grant evaluators who are able to determine if a knowledge exchange strategy is appropriate to the policy sphere (Baylis et al., 2016; section Reconfigure the award adjudication processes), such efforts are important when evaluating the potential utility of research proposals. In addition, proof of knowledge exchange outputs (i.e., policy briefs, etc.) from previous research projects can indicate the level of commitment a research team has to the knowledge exchange process (section Following-up on and rewarding knowledge exchange; Arnott, 2019). Several funding bodies have begun to require outreach and knowledge exchange plans to be included in the grant proposals (Cvitanovic et al., 2015). Funding agencies that allow researchers to budget funds explicitly for knowledge exchange have higher success in ensuring it occurs (Shanley and López, 2009; Matso and Becker, 2014; Cvitanovic et al., 2015).

Closed-Ended Questions: Characteristics of Successful Proposals

Responses to the closed-ended survey question supported findings from the open-ended questions described above. The results of the quantitative analysis thus serve as a robustness check to the open-ended question. In addition, the variation in responses among sectors highlights the importance of considering context when interpreting the findings presented here. Connections among themes and responses are illustrated in Figure 2 and summarized in Table 2.

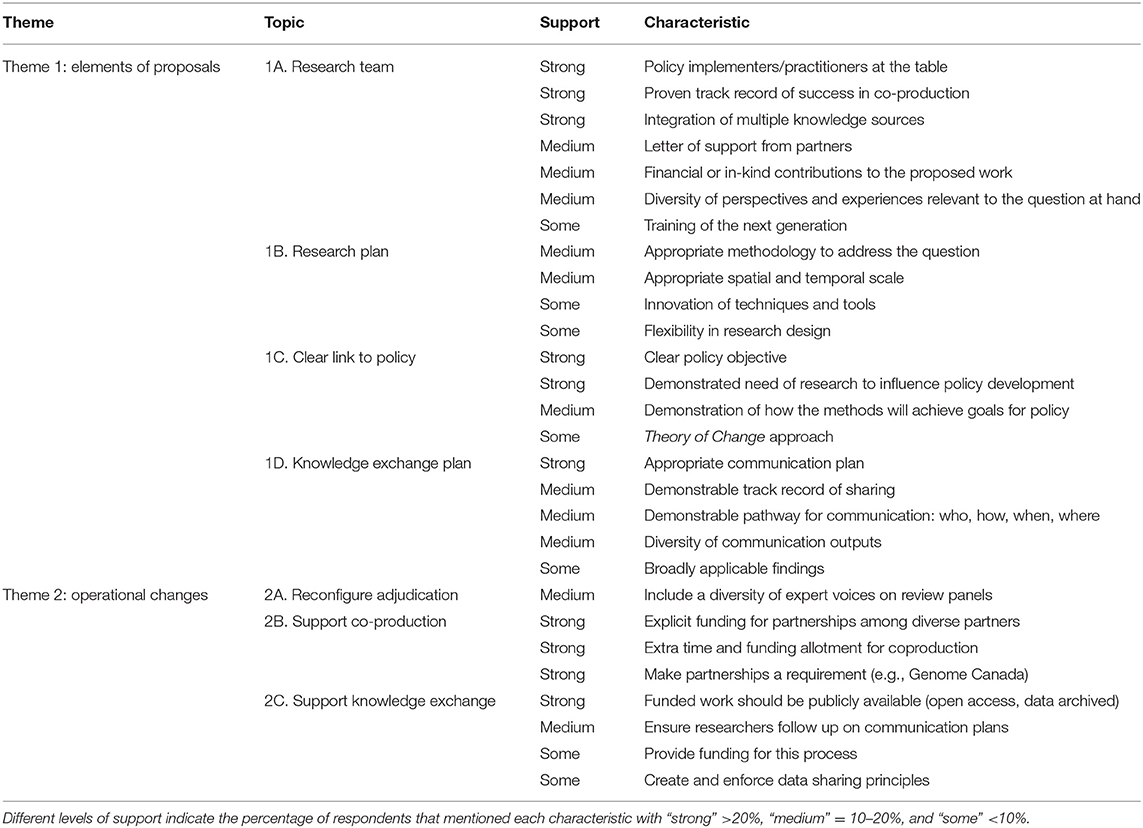

The list order in the three versions of the closed ended question had no effect on the frequency of participants' selections for any of the characteristics (Appendix C). The quantitative analysis revealed that the top five most common characteristics respondents sought in proposals were: (i) a plan for knowledge exchange to facilitate the transfer of relevant information to the correct people; (ii) a team that is socially and culturally diverse, including representation from Indigenous groups and stakeholders (where appropriate); (iii) a team with representatives from different academic disciplines and professional backgrounds, including practitioners and decision makers; (iv) an appropriate study design and methodology to address the policy issue at hand; and (v) a plan to publish the findings of the study in a peer-reviewed journal (Figure 1). There was some variation among sectors in what stood out as most important for evaluating proposals that are likely to produce actionable knowledge (Figure 1). Respondents from the federal government pushed for strong knowledge exchange plans (emphasizing peer review) and thorough consideration of research methods used (Figure 1). Provincial and territorial government responses supported the need for knowledge exchange plans, feasibility and flexibility of methodological approach, and social-cultural diversity within teams (Figure 1). They also emphasized the importance of understanding the needs of the end-user more than the other sectors did (Figure 1). Respondents from the ENGO sector chose socio-cultural diversity and emphasized the need for multi-disciplinary teams (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proportion of responses for each characteristic from the aggregated list (see Appendix A) provided for the closed-ended question: “select elements of proposals that increase the likelihood that the research will be actionable.” Responses are presented as a proportion of all responses including selections for “all that apply” and for “top 3.” Beige bars at the bottom represent the proportion of responses that came from the “top 3” selection and the remainder represents the proportion of responses that came from the “all that apply” selection.

Differences in priorities among sectors likely reflect the scale and scope of work conducted by each group. Federal government departments in Canada face national-level environmental challenges affecting a vast country with diverse social, economic, and ecological needs (Cooke et al., 2016). Knowledge to support such decisions must be precise yet generalizable, so it is logical that the priorities of the federal government align with classic academic priorities such as peer review and consistent methodology and reporting. Much of this support is also likely driven by the fact that most (82%) federal employees interviewed had academic backgrounds. Such training is likely to influence their values towards academic approaches to evaluation.

Although federal government departments make national environmental decisions, most constitutional powers for natural resources and environmental management reside with the provinces and territories (Becklumb, 2013). Participants from provincial and territorial governments indicated that they had considerable hands-on experience with policy and practice. This group's insights are thus in tune with the types of knowledge that are useful on the ground. Their choices also reflect the relatively smaller geographic scale and context of policy decisions faced by provincial and territorial governments. The reclamation and recognition of the roles and jurisdiction of Indigenous Peoples in environmental and natural resource governance means that territorial and provincial settler governments frequently make decisions alongside Indigenous governments and partners (Cooke et al., 2016; Pasternak et al., 2019), which likely contributes to cultural representation being a high priority for this sector.

Participants from ENGOs had a strong focus on the social, cultural, institutional, and disciplinary diversity of the research teams. Many of the ENGOs represented in this study indicated that they have histories of engaging local and Indigenous communities in their research processes and incorporating diverse philosophies into conservation and management recommendations. Witnessing the benefits of these collaborations for promoting knowledge uptake and community cooperation likely motivates the emphasis on diversity-related qualities.

The quantitative analysis highlights the importance of understanding how various contexts might influence what is considered important in research proposals. Knowledge that is deemed actionable is likely to change depending on the spatial and temporal scale, the stakeholders involved, and the policy issue at hand (Mach et al., 2020). Likewise, proposal calls, and selection criteria set by different funding agencies are likely to vary depending on their jurisdiction and goals. The criteria outlined above for elements of proposals that are likely to result in actionable knowledge are intended to be generalizable; however, funding agencies must carefully consider whether and how each recommendation applies to their specific goals, and to use these recommendations as general guidelines (not strict rules) to be used at their discretion.

Operational Changes in Prioritizing Research and Managing Fund Distribution (Theme 2)

Open-Ended Questions: Operational Advice to Funders

Although the above suggestions are important considerations for selecting promising proposals, each suggestion demands time from researchers, increased financial support, and broad inter- and trans-disciplinary networks (Lemos et al., 2018). These requirements represent potential barriers that, without institutional support, might prevent researchers from carrying out important policy-relevant work. A central finding from this work was that funding agencies' responsibilities can go beyond simply selecting the best proposals, and then hoping the work proceeds as planned (i.e., a “fund and forget” model; Holmes et al., 2012). Several participants recommended ways that funding agencies could alter their internal operations to lower barriers to producing and communicating actionable knowledge. We outline three major topics including: (2A) drawing on a diversity of expertise during award adjudication; (2B) supporting co-production and interdisciplinary research; and (2C) following-up on and rewarding knowledge exchange.

2A. Reconfigure the Award Adjudication Processes

Including experts with diverse experience, knowledge, and expertise on review panels was suggested as an important action by funding agencies that can help determine whether proposed research projects are likely to be successful in producing actionable knowledge. As stated by a provincial/territorial government employee: “…if it's forestry sector research, how is the forestry sector actually going to use this information to advance their practices? Those statements would have to come from the forestry sector, not from the researcher or the funding body” [male, provincial (AB)]. Participants suggested that including voices of knowledge end users and/or relevant cultural groups in the adjudication process can mean that project proposals are assessed not only for scientific excellence but also for the relevance of the results to policy issues. Having such diversity on adjudication committees can promote selection of proposals with appropriate and timely research plans (Figure 2, section Research team comprises diverse perspectives and expertise appropriate to the problem at hand) and provide insight into whether the proposed research has a clear link to policy (Figure 2, section Clear and demonstrable link to policy). Furthermore, including a communications expert on the adjudication panel can help to determine whether a proposed knowledge exchange strategy is appropriate for the policy context (Figure 2, section Plan for knowledge exchange with diverse audiences). Several studies investigating the US-based National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS) funding program have shown that diverse adjudication panels increased the legitimacy, credibility, and salience of the funded research (Matso, 2012; Trueblood et al., 2019). Further research into the tangible outcomes of soliciting expert opinion during the proposal review process and methods to ensure role clarity within diverse selection committees is necessary to determine how such committees should be assembled and how they should operate (Ly et al., 2018; Arnott et al., 2020a).

Figure 2. Schematic diagram outlining recommendations for funders looking to increase the impact of the research they sponsor. Recommendations in blue circles include elements of proposals that funders can look for to determine whether the research will result in actionable knowledge. Recommendations in red circles represent internal changes to funding structures that could allow for institutional change from within funding agencies. Red lines indicate connections where operational changes to funding agencies (Theme 2) can improve the likelihood that proposals will contain elements outlined in Theme 1.

2B. Supporting Co-production and Interdisciplinary Research

A common point raised by participants is that funders should rethink existing methods used to evaluate, prioritize, and allocate funding to projects. Many suggested that academic funders should solicit, incentivize, and reward co-production and interdisciplinary work in applied conservation (Figure 2, Table 2). Some suggested that additional funding could be allocated to projects with diverse teams given the extra time required for co-produced projects, either through distinct funding calls or through additional funding funneled through existing streams. As mentioned by a scientist in the ENGO sector:

I think that funders need to think carefully about the importance of partnerships with civil society because that will help inform how the research is done. For example, look at the dearth of Indigenous participation in research right now. The absence of Indigenous voices needs to be addressed through explicit funding for partnerships among researchers, departments, policymakers, and resource users [male, ENGO (ON)].

Given that there is increasing evidence that co-produced knowledge can be highly effective at influencing policy (Nel et al., 2016; Posner et al., 2016; Mach et al., 2020), it is intuitive that funding bodies could and should develop mechanisms that support this work (Lemos et al., 2018). Research has shown that funders who mandate and provide support for interactions between researchers and knowledge users are more successful in ensuring that knowledge exchange occurs and that the funded research goes on to inform policy decisions (Riley et al., 2011; Matso and Becker, 2013, 2014; DeLorme et al., 2016; Moser, 2016).

Some funders support researchers in building diverse networks at the outset of a new research initiative, often resulting in synergy among collaborators (Lyall et al., 2013), which can lead to successful integration of the research findings into policy and practice (Matso and Becker, 2013, 2014; Arnott et al., 2020b). This can be accomplished through providing seed funding for starting interdisciplinary projects, and by funding or offering workshops and/or courses to introduce, grow, and solidify partnerships (Lyall et al., 2013). In addition, funders must recognize that co-producing knowledge within diverse teams usually requires more time and funding than a typical project (Lemos et al., 2018). Providing allowances for the extra cost and time associated with co-production is therefore essential for “true” co-production to occur (Beier et al., 2017; Oliver et al., 2019; Norström et al., 2020). Finally, funding agencies have a role to play in ensuring that such relationships are maintained (Sibbald et al., 2014). Participants suggested that funding agencies should incorporate check-ins and incentives throughout the research process to ensure that collaborations are ongoing. Lack of explicit guidance can lead to regulations being misinterpreted resulting in the failure to meet the intended goals of the project (Reale and Zinilli, 2017).

The idea that funders should play a supporting role throughout the research process has been adopted by some medical funding bodies (Holmes et al., 2012; Smits and Denis, 2014) and is growing in environmental fields (Matso and Becker, 2014; DeLorme et al., 2016). In Canada, several programs require academic researchers to collaborate with external partners in business, policy, or industry [e.g., Mitacs Accelerate Fellowship, Canada's Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Partnership, NSERC Alliance, SSHRC New Frontiers, Liber Ero Fellowship]. Anecdotal evidence suggests these programs have been effective in forming long-lasting collaborations (Mitacs, 2015). However, formal research is necessary to determine whether such patterns are systematic, and many funding bodies do not measure or track policy relevance, only have trivial reporting requirements, and use traditional metrics such as citation rates as opposed to policy impact (Coutinho and Young, 2016). The incremental changes modeled by the NERRS funding system provides an example of how funding bodies can gradually implement change while checking to ensure the adjustments are having the desired outcomes (Trueblood et al., 2019).

2C. Following-Up on and Rewarding Knowledge Exchange

Several respondents discussed that research findings must be shared through appropriate channels. Having a plan for knowledge exchange is key (Figure 2, section Plan for knowledge exchange with diverse audiences); however, it is equally important to ensure that researchers follow up on knowledge exchange plans. Several respondents suggested that this can be done by incentivising knowledge sharing by providing funds for this process (e.g., to run workshops, create communication tools, etc.) or by creating and (better) enforcing data sharing policies (Figure 2). Several studies have shown that funding models with financial support for communication and knowledge exchange have a higher probability of knowledge being used in policy (Shanley and López, 2009; Riley et al., 2011; Matso and Becker, 2014). Such findings suggest that funds should be set aside to support engagement activities (Lavis et al., 2003; Lyall et al., 2013; Cvitanovic et al., 2016). In addition, even though a growing number of funding agencies are encouraging open access policies (Roche et al., 2014), better enforcement can improve their effectiveness (Sholler et al., 2019).

Rewarding researchers for information sharing through increased funding or peer recognition is likely to encourage more frequent and higher quality efforts (Provencal, 2011). Scientists could be recognized for more than just peer-reviewed publications; production of alternative forms of knowledge exchange and co-production could factor into their evaluation (section Plan for knowledge exchange with diverse audiences). Impact evaluation can determine whether attempts at knowledge exchange reached the correct audiences in a timely manner (Baylis et al., 2016), and whether principles of co-production have been followed (Norström et al., 2020). Funding agencies should develop guidelines to help evaluators recognize and value knowledge exchange. If funders recognized and valued these efforts equally with peer-reviewed papers, then academic institutions would not need to question the relevance and importance of such contributions (Lavis et al., 2003).

Emerging Challenges and Recommendations

The results of this study provide recommendations from Canadian science-policy experts on important considerations for funding bodies looking to support policy-relevant research. These recommendations are designed to be actionable and some of the suggestions are already practiced by innovative Canadian and international funding bodies. However, new challenges to implementing these recommendations have arisen from this work. We discuss these challenges and suggest approaches to overcoming them.

An important consideration is how to (re)structure the proposal evaluation process to account for the potential utility of the research to policy. Given the complex interdisciplinary, cross-sectoral, and context-specific nature of policy-oriented research, an adaptive approach to proposal evaluation is required. Needs and priorities at the science-policy interface shift depending on changing political climates (Rose et al., 2017) and evolving stakeholder priorities (Scolobig and Lilliestam, 2016). Models for adaptive evaluation of grant proposals or adaptive design of funding calls have yet to be developed; however, analogous systems have emerged from the human system dynamics literature, which suggests that evaluation criteria (and, by extension, priorities in proposal calls) should be reassessed for each new round of funding (Eoyang and Oakden, 2016). Steps to adaptive evaluation modified from this literature include: (1) designing initial criteria; (2) collecting and analyzing data on the success of projects; (3) assessing social, scientific, or political changes; (4) adapting proposal calls and evaluation criteria; and (5) reporting the outcomes (Eoyang and Oakden, 2016). These data could be used to inform initiatives or training offered by funding agencies to enhance research outcomes.

Related to restructuring the evaluation process is the suggestion to incorporate a diversity of perspectives on award adjudication committees. Such an approach requires funding bodies to use a co-production-like model when designing funding calls and deciding on selection criteria (Smits and Denis, 2014). The question thus arises as to how adjudication committees can incorporate a diversity of views without sacrificing the priorities of the stakeholders involved. Based on recommendations from literature on approaches to team management, we recommend having clearly defined roles and responsibilities of various committee members so that everyone is assigned the section of the proposal most relevant to them (Henderson et al., 2016; Ly et al., 2018). Role clarity can streamline processes of complex teams (Ly et al., 2018). Training for committee members to understand different working practices and different priorities among sectors or disciplines and engaging in reflexive and considerate discourse to mutually decide on project goals early in the award solicitation process can also help to overcome barriers encountered by diverse adjudication committees (vom Brocke and Lippe, 2015).

A third challenge emerged from the suggestion that research teams must include individuals with experience in co-production and a high level of expertise in each of the relevant spheres. This presents the conundrum of how to facilitate the entry of motivated but inexperienced academic researchers into collaborative work with practitioners (Kelly et al., 2019) and raises the question of how funding agencies can best support the process of building interdisciplinary networks. Based on participants' responses and literature review, we suggest that funders could play a more active role in developing collaborations by linking various actors and by facilitating training and mentorship opportunities for ECRs and MCRs (Sibbald et al., 2014; Haider et al., 2018). Funders and their program managers are often uniquely aware of individuals who could and should be linked (Arnott et al., 2020a) and can thus facilitate the development of new partnerships by connecting appropriate actors and fostering interactions among researchers or organizations with similar interests (Sibbald et al., 2014). Feedback from mentors and mentees could be required to evaluate whether mentorship promises are being realized (Hund et al., 2018).

In conclusion, participants in this study indicated that funding agencies' responsibilities should go beyond simply selecting the best proposals, and then hoping the work proceeds as planned. There are many diverse factors that influence whether research has a policy impact, and there are often political realities that will prevail despite the scientific evidence that is supplied. However, this work has advanced our understanding of the roles and responsibilities of funding agencies, which is a crucial area where tangible improvements can be made. Funders have the potential to have impact at all stages of research from solicitation to proposal requirements and funding selection, to follow up and evaluation. Although our recommendations do not guarantee success in identifying proposals that will yield actionable knowledge in all contexts, following these guidelines could increase the utility of funded research if that is the goal of the funding agency.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets cannot be shared due to confidentiality rules for data collected from human subjects. Even with names removed, the interview content could be sufficient to reveal the identity of the participants. Requests to access and use the data should be directed to Yi5hLm55Ym9lckBnbWFpbC5jb20=.

Ethics Statement

This study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Carleton University Research Ethics Board File #12486. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

EN: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing–original draft, writing–review & editing, visualization, and supervision. SMA, GA, DB, AJ, KP, PS, KS, SA, and SC: conceptualization, methodology, writing–review & editing, supervision, and funding acquisition. VN, NY, and JB: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and writing–review & editing. TR and JT: conceptualization, methodology, writing–review & editing, and project administration. JL: methodology, investigation, and writing–review & editing. NH: methodology, investigation, formal analysis, and writing–review & editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Funding was provided by NSERC via an NSE Grant to SC Additional support was provided by Carleton University via the Multidisciplinary Research Catalyst Fund Funding. Funding was provided to EAN by Fonds de recherche du Quebec, Nature et Technology (FRQNT) grant no. 256972.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the participants in our study for offering their valuable time and knowledge.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2021.693129/full#supplementary-material

References

Arnott, J.C. (2019). Accelerating actionable sustainability science: Science funding, co-production, and the evolving social contract for science. Ph.D. thesis, Environment and Sustainability, University of Michigan.

Arnott, J. C., Kirchhoff, C. J., Meyer, R. M., Meadow, A. M., and Bednarek, A. T. (2020a). Sponsoring actionable science: what public science funders can do to advance sustainability and the social contract for science. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sust. 42, 38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2020.01.006

Arnott, J. C., Neuenfeldt, R. J., and Lemos, M. C. (2020b). Co-producing science for sustainability: can funding change knowledge use? Glob. Environ. Change 60:101979. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101979

Baylis, K., Honey-Roses, J., Borner, J., Corbera, E., Ezzine-De-Blas, D., Ferraro, P. J., et al. (2016). Mainstreaming impact evaluation in nature conservation. Conserv. Lett. 9, 58–64. doi: 10.1111/conl.12180

Becklumb, P. (2013). “Federal and provincial jurisdiction to regulate environmental issues,” in Economics, Resources, and International Affairs Division, Parliamentary Information and Research Service. Ottawa, ON: Library of Parliament. 1–9.

Bednarek, A. T., Shouse, B., Hudsons, C. G., and Goldburg, R. (2016). Science-policy intermediaries from a practitioner's perspective: the lenfest ocean program experience. Sci. Public Policy 43, 291–300. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scv008

Beier, P., Hansen, L. J., Helbrecht, L., and Behar, D. (2017). A how-to guide for coproduction of actionable science. Conserv. Lett. 10, 288–296. doi: 10.1111/conl.12300

Boaz, A., Hanney, S., Borst, R., O'Shea, A., and Kok, M. (2018). How to engage stakeholders in research: design principles to support improvement. Health Res. Policy Syst. 16:60. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0337-6

Bozeman, B., and Youtie, J. (2017). Socio-economic impacts and public value of government funded research: lessons from four US national science foundation initiatives. Res. Policy 46, 1387–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2017.06.003

Buxton, R. T., Nyboer, E. A., Pigeon, K. E., Raby, G. D., Rytwinski, T., Gallagher, A. J., et al. (2021). Avoiding wasted research resources in conservation science. Conservat. Sci. Pract 2021:e329. doi: 10.1111/csp2.329

Chapman, J. M., Algera, D., Dick, M., Hawkins, E. E., Lawrence, M. J., Lennox, R. J., et al. (2015). Being relevant: practical guidance for early career researchers interested in solving conservation problems. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 4, 334–348. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2015.07.013

Cook, C. N., Inayatullah, S., Burgman, M. A., Sutherland, W. J., and Wintle, B. A. (2014). Strategic foresight: how planning for the unpredictable can improve environmental decision-making. Trends Ecol. Evolut. 29, 531–554. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2014.07.005

Cook, C. N., Mascia, M. B., Schwartz, M. W., Possingham, H. P., and Fuller, R. A. (2013). Achieving conservation science that bridges the knowledge-action boundary. Conserv. Biol. 27, 669–678. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12050

Cooke, S. J., Rice, J. C., Prior, K. A., Bloom, R., Jensen, O., Browne, D. R., et al. (2016). The Canadian Context for evidence-based conservation and environmental management. Environ. Evid. 5:14. doi: 10.1186/s13750-016-0065-8

Cooke, S. J., Rytwinski, T., Taylor, J., Nyboer, E., Nguyen, V., Bennett, J., et al. (2020). On “success” in applied environmental research: what is it, how can it be achieved, and how does one know when it has been achieved? Environ. Rev. 28:354–372. doi: 10.1139/er-2020-0045

Coutinho, A., and Young, N. (2016). Science transformed? A comparative analysis of “societal relevance” rhetoric and practices in 14 Canadian networks of centres of excellence. Prometheus 34, 133–152. doi: 10.1080/08109028.2017.1280936

Cvitanovic, C., Fulton, C. J., Wilson, S. K., van Kerkhoff, L., Cripps, I. L., and Muthiga, N. (2014). Utility of primary scientific literature to environmental managers: an international case study on coral-dominated marine protected areas. Ocean Coast. Manage. 102, 72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.09.003

Cvitanovic, C., Hobday, A., Wilson, S., Dobbs, K., and Marshall, N. (2015). Improving knowledge exchange among scientists and decision-makers to facilitate the adaptive governance of marine resources: a review of knowledge and research needs. Ocean Coast. Manage. 112, 25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.05.002

Cvitanovic, C., McDonald, J., and Hobday, A. J. (2016). From science to action: Principles for undertaking environmental research that enables knowledge exchange and evidence-based decision-making. J. Environ. Manage. 183, 864–874. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.09.038

De Silva, M. J., Breuer, E., Lee, L., Ahser, L., Chowdhary, N., Lund, C., et al. (2014). Theory of Change: a theory-driven approach to enhance the medical research council's framework for complex interventions. Trials 15:267. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-267

DeLorme, D. E., Kidwell, D., Hagen, S. C., and Stephens, S. H. (2016). Developing and managing transdisciplinary and transformative research on the coastal dynamics of sea level rise: experiences and lessons learned. Earths Future 4, 194–209. doi: 10.1002/2015EF000346

Eoyang, G., and Oakden, J. (2016). Adaptive evaluation: a synergy between complexity theory and evaluation practice. Emerg. Complex. Organ. doi: 10.emerg/10.17357.e5389f5715a734817dfbeaf25ab335e5

Fiorino, D. J. (1995). Making Environmental Policy. Berkeley, CA. University of California Press. doi: 10.1525/9780520915466

Fisher, D., Atkinson-Grosjean, J., and House, D. (2001). Changes in academy/industry/state relations in Canada: the creation and development of the NCE. Minerva 39, 299–325. doi: 10.1023/A:1017924027522

Fujitani, M., McFall, A., Randler, C., and Arlinghaus, R. (2017). Participatory adaptive management leads to environmental learning outcomes extending beyond the sphere of science. Sci. Adv. 3:e1602516. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602516

Gevers, J. M. P., van Eerde, W., and Rutte, C. G. (2001). Time pressure, potency, and progress in project groups. Euro. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 10, 205–221 doi: 10.1080/13594320143000636

Haider, J. L., Hentati-Sundbert, J., Giusti, M., Goodness, J., Hamann, M., Masterson, V. A., et al. (2018). The undisciplinary journey: early-career perspectives in sustainability science. Sust. Sci. 13, 191–204. doi: 10.1007/s11625-017-0445-1

Henderson, L., Stackman, R. W., and Lindekilde, R. (2016). The centrality of communication norm alignment, role clarity, and trust in global project teams. Int. J. Proj. Manage. 34, 1717–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.09.012

Holmes, B., Scarrow, G., and Schellenberg, M. (2012). Translating evidence into practice: the role of health research funders. Implement. Sci. 7:37. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-39

Holmes, J., and Clark, R. (2008). Enhancing the use of science in environmental policy-making and regulation. Environ. Sci. Policy 11, 702–711. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2008.08.004

Howarth, C., and Monasterolo, I. (2016). Understanding barriers to decision making in the energy-foodwater nexus: the added value of interdisciplinary approaches. Environ. Sci. Policy, 61, 53–60.

Hund, A. K., Churchill, A. C., Faist, A. M., Havrilla, C. A., Stowell, S. M. L., McCreery, H. F., et al. (2018). Transforming mentorship in STEM by training scientists to be better leaders. Ecol. Evolut. 8:9962–9974. doi: 10.1002/ece3.4527

Karl, H. A., Susskind, L. E., and Wallace, K. H. (2007). A dialogue not a diatribe—effective integration of science and policy through joint fact finding. Environment 49, 20–34. doi: 10.3200/ENVT.49.1.20-34

Kelly, R., Mackay, M., Nash, K. L., Cvitanovic, C., Allison, E. H., Armitage, D., et al. (2019). Ten tips for developing interdisciplinary socio-ecological researchers. Soc. Ecol. Pract. Res. 1, 149–161. doi: 10.1007/s42532-019-00018-2

Lavis, J. N., Robertson, D., Woodside, J. M., McLeod, C. B., Abelson, J., and the Knowledge Transfer Study Group. (2003). How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? Milbank Q. 81, 221–245 doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00052

Lemos, M. C., Arnott, J. C., Ardoin, N. M., Baja, K., Bednarek, A. T., Dewulf, A., et al. (2018). To co-produce or not to co-produce. Nat. Sust. 1, 722–724. doi: 10.1038/s41893-018-0191-0

Ly, O., Sibbald, S. L., Verma, J. Y., and Rocker, G. M. (2018). Exploring role clarity in interorganizational spread and scale-up initiatives: the ‘INSPIRED' COPD collaborative. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18:680. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3474-2

Lyall, C., Bruce, A., Marsden, W., and Meagher, L. (2013). The role of funding agencies in creating interdisciplinary knowledge. Sci. Public Policy 40, 62–71. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scs121

Lyall, C., and Meagher, L. (2012). ‘A masterclass in interdisciplinarity: research into practice in training the next generation of interdisciplinary researchers. Futures 44, 608–617. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2012.03.011

Mach, K. J., Lemos, M. C., Meadow, A. M., Wyborn, C., Klenk, N. L., Arnott, J. C., et al. (2020). Actionable knowledge and the art of engagement. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sust. 42, 30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2020.01.002

Matso, K. E. (2012). “Challenge of integrating natural and social sciences to better inform decisions: a novel proposal review process,” in Restoring Lands–Coordinating Science, Politics and Action: Complexities of Climate and Governance, eds H. Karl, L. Scarlett, J. Vargas-Moreno, M. Flaxman (Dordrecht: Springer), 129–160. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-2549-2_7

Matso, K. E., and Becker, M. L. (2013). Funding science that links to decisions: case studies involving coastal land use planning projects. Estuar. Coasts 38, 136–150. doi: 10.1007/s12237-013-9649-5

Matso, K. E., and Becker, M. L. (2014). What can funders do to better link science with decisions? Case studies of coastal communities and climate change. Environ. Manage. 54, 1356–1371. doi: 10.1007/s00267-014-0347-2

McGowan, J. J., Cusack, C. M., and Poon, E. G. (2008). Formative evaluation: a critical component in EHR implementation. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 15, 297–301. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2584

Meng, M., Lei, J., Jiao, J., and Tao, Q. (2020). How does strategic flexibility affect bricolage: the moderating role of environmental turbulence. PLoS ONE 15:e0238030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238030

Michaels, S. (2009). Matching knowledge brokering strategies to environmental policy problems and settings. Environ. Sci. Policy 12, 994–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2009.05.002

Mitacs (2015). Creating Opportunities for the Nextgeneration Of Innovators. Available online at: https://www.mitacs.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/page/year_in_review2015.pdf

Moser, S. C. (2016). Can science on transformation transform science? Lessons from co-design. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sust. 20, 106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2016.10.007

Nel, J. L., Roux, D. J., Driver, A., Hill, L., Maherry, A. C., Snaddon, K., et al. (2016). Knowledge coproduction and boundary work to promote implementation of conservation plans. Conserv. Biol. 30, 176–188. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12560

Nguyen, V. M., Young, N., and Cooke, S. J. (2017). A roadmap for knowledge exchange and mobilization research in conservation and natural resource management. Conserv. Biol. 31, 789–798. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12857

Nguyen, V. N., Young, N., Brownscombe, J., and Cooke, S. J. (2019). Collaboration and engagement produce more actionable science: quantitatively analyzing uptake of fish tracking studies. Ecol. Applic. 29:e01943. doi: 10.1002/eap.1943

Norström, A. V., Cvitanovic, C., Löf, M. F., West, S., Wyborn, C., Balvanera, P., et al. (2020). Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nat. Sust. 3, 182–190. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0448-2

Oliver, K., Kothari, A., and Mays, N. (2019). The dark side of coproduction: do the costs outweigh the benefits for health research? Health Res. Policy Syst. 17:33. doi: 10.1186/s12961-019-0432-3

Pasternak, S., King, H., and Yesno, R. (2019). Land Back: A Yellowhead Institute Red Paper. Available online at: https://redpaper.yellowheadinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/red-paper-report-final.pdf

Posner, S. M., McKenzie, E., and Ricketts, T. H. (2016). Policy impacts of ecosystem services knowledge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 1760–1765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502452113

Provencal, J. (2011). Extending the reach of research as a public good: moving beyond the paradox of “zero-sum language games.” Public Understand. Sci. 20, 101–116. doi: 10.1177/0963662509351638

Pullin, A. S., Knight, T. M., Stone, D. A., and Charman, K. (2004). Do conservation managers use scientific evidence to support their decision-making? Biol. Conserv. 119, 245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2003.11.007

Reale, E., and Zinilli, A. (2017). Evaluation for the allocation of university research project funding: can rules improve the peer review? Res. Evaluat. 26, 190–198. doi: 10.1093/reseval/rvx019

Reed, M. S., Stringer, L. C., Fazey, I., Evely, A. C., and Kruijsen, J. H. J. (2014). Five principals for the practice of knowledge exchange in environmental management. J. Environ. Manage. 146, 337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.07.021

Riley, C., Matso, K. E., Leonard, D., Stadler, J., Trueblood, D., and Langan, R. (2011). How research funding organizations can increase application of science to decision-making. Coast. Manage. 39, 336–350. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2011.566117

Roche, D. G., Lanfear, R., Binning, S. A., Haff, T. M., Schwanz, L. E., Cain, K. E., et al. (2014). Troubleshooting public data archiving: suggestions to increase participation. PLoS Biol. 12:e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001779

Rose, D. C., Amano, T., Gonzalez-Varo, J. P., Mukherjee, N., Robertson, R. J., Simmons, B. I., et al. (2019). Calling for a new agenda for conservation science to create evidence informed policy. Biol. Conserv. 238:108222. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108222

Rose, D. C., Mukherjee, N., Simmons, B. I., Tew, E. R., Robertson, R. J., Vadrot, A. B. M., et al. (2017). Policy windows for the environment: tips for improving the uptake of scientific knowledge. Environ. Sci. Policy 113, 47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2017.07.013

Rose, D. C., Sutherland, W. J., Amano, T., González-Varo, J., Robertson, RJ, Simmons, B. I., Wauchope, H. S., Kovaks, E., et al. (2018). The major barriers and their solutions for evidence-informed conservation policy. Conserv. Lett. 11:e12564. doi: 10.1111/conl.12564

Safford, H., and Brown, A. (2019). Communicating science to policymakers: six strategies for success. Nature 572, 681–682 doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-02372-3

Scolobig, A., and Lilliestam, J. (2016). Comparing approaches for the integration of stakeholder perspectives in environmental decision making. Resources 5:37. doi: 10.3390/resources5040037

Shanley, P., and López, C. (2009). Out of the loop: why research rarely reaches policy makers and the public and what can be done. Biotropica 41, 535–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2009.00561.x

Sholler, D., Ram, K., Boettiger, C., and Katz, D. S. (2019). Enforcing public data archiving policies in academic publishing: a study of ecology journals. Big Data Soc. 6:2053951719836258. doi: 10.1177/2053951719836258

Sibbald, S. L., Tetroe, J., and Graham, I. D. (2014). Research funder required research partnerships: a qualitative inquiry. Implement. Sci. 9:176. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0176-y

Smits, P. A., and Denis, J.-L. (2014). How research funding agencies support science integration into policy and practice. An international overview. Implement. Sci. 9:28. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-28

Sutherland, W. J., and Wordley, C. F. R. (2017). Evidence complacency hampers conservation. Nat. Ecol. Evolut. 1, 1215–1216. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0244-1

Trueblood, D., Almazán-Casali, S., Arnott, J., Brass, M., Lemos, M. C., Matso, K., et al. (2019). Advancing knowledge for use in coastal and estuarine management: Competitive research in the national estuarine research reserve system. Coast. Manage. 47, 337–346. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2019.1598221

vom Brocke, J., and Lippe, S. (2015). Managing collaborative research projects: a synthesis of project management literature and directives for future research. Int. J. Proj. Manage. 33, 1022–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.02.001

Keywords: evidence-informed decision-making, science-policy boundaries, knowledge exchange (or knowledge translation), science funding, funding model, granting agencies, knowledge mobilization

Citation: Nyboer EA, Nguyen VM, Young N, Rytwinski T, Taylor JJ, Lane JF, Bennett JR, Harron N, Aitken SM, Auld G, Browne D, Jacob AI, Prior K, Smith PA, Smokorowski KE, Alexander S and Cooke SJ (2021) Supporting Actionable Science for Environmental Policy: Advice for Funding Agencies From Decision Makers. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2:693129. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2021.693129

Received: 09 April 2021; Accepted: 31 May 2021;

Published: 22 July 2021.

Edited by:

Silvio Marchini, University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Marc J. Stern, Virginia Tech, United StatesL. Jen Shaffer, University of Maryland, United States

Copyright © 2021 Nyboer, Nguyen, Young, Rytwinski, Taylor, Lane, Bennett, Harron, Aitken, Auld, Browne, Jacob, Prior, Smith, Smokorowski, Alexander and Cooke. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elizabeth A. Nyboer, Yi5hLm55Ym9lckBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Elizabeth A. Nyboer

Elizabeth A. Nyboer Vivian M. Nguyen1

Vivian M. Nguyen1 Graeme Auld

Graeme Auld Aerin I. Jacob

Aerin I. Jacob